Learning how to dance in ohio

How to Dance in Ohio (2015)

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

- Trivia

IMDbPro

- 20152015

- TV-GTV-G

- 1h 29m

IMDb RATING

7.7/10

257

YOUR RATING

DocumentaryDrama

In Columbus, Ohio, a group of teenagers and young adults on the autism spectrum prepare for an iconic American rite of passage -- a Spring Formal. They spend 12 weeks practicing their social... Read allIn Columbus, Ohio, a group of teenagers and young adults on the autism spectrum prepare for an iconic American rite of passage -- a Spring Formal. They spend 12 weeks practicing their social skills in preparation for the dance at a local nightclub. Working with their psychologist... Read allIn Columbus, Ohio, a group of teenagers and young adults on the autism spectrum prepare for an iconic American rite of passage -- a Spring Formal. They spend 12 weeks practicing their social skills in preparation for the dance at a local nightclub. Working with their psychologist, they take the challenges expressed in their respective therapy groups from one level to ... Read all

IMDb RATING

7.7/10

257

YOUR RATING

- Alexandra Shiva

- Alexandra Shiva

- Awards

- 3 wins & 4 nominations

Photos8

More like this

Love & Stuff

Keep the Change

V/H/S

Storyline

Did you know

User reviews3

Review

Featured review

9/

10

new insights

As the father of an autistic, now adult child , this documentary provided some new insights into the mind of an autistic person. Listening to the parents and their struggles and the therapist as well, this will assist me in developing more tolerance for my child and their unique challenges.

Listening to the parents and their struggles and the therapist as well, this will assist me in developing more tolerance for my child and their unique challenges.

helpful•2

1

- mudbone-42885

- Apr 27, 2021

IMDb Best of 2022

IMDb Best of 2022

Discover the stars who skyrocketed on IMDb’s STARmeter chart this year, and explore more of the Best of 2022; including top trailers, posters, and photos.

See more

Details

- Release date

- October 26, 2015 (United States)

- United States

- Official site

- English

- Also known as

- Jak się tańczy w Ohio?

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Technical specs

1 hour 29 minutes

Related news

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

Top Gap

What is the English language plot outline for How to Dance in Ohio (2015)?

Answer

More to explore

Recently viewed

You have no recently viewed pages

How to Dance in Ohio Movie Review

Skip to main contentMovie review by Melissa Camacho, Common Sense Media

Common Sense says

age 12+

Inspirational, heartwarming doc about living with autism.

NR 2015 89 minutes

Rate movie

Common Sense is a nonprofit organization. Your purchase helps us remain independent and ad-free.

Rate movie

Did we miss something on diversity?

Research shows a connection between kids' healthy self-esteem and positive portrayals in media. That's why we've added a new "Diverse Representations" section to our reviews that will be rolling out on an ongoing basis. You can help us help kids by suggesting a diversity update.

What Parents Need to Know

Parents need to know that How to Dance In Ohio is a documentary that centers on a group of high-functioning people on the autism spectrum preparing for the challenges and joys that come with attending a formal dance. Therapy and living with autism are central themes. The Amigo Counseling Center and its program are highlighted. There's nothing to worry about here, but some folks may be sensitive to some of the concerns expressed about living with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Therapy and living with autism are central themes. The Amigo Counseling Center and its program are highlighted. There's nothing to worry about here, but some folks may be sensitive to some of the concerns expressed about living with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Community Reviews

There aren't any reviews yet. Be the first to review this title.

What's the Story?

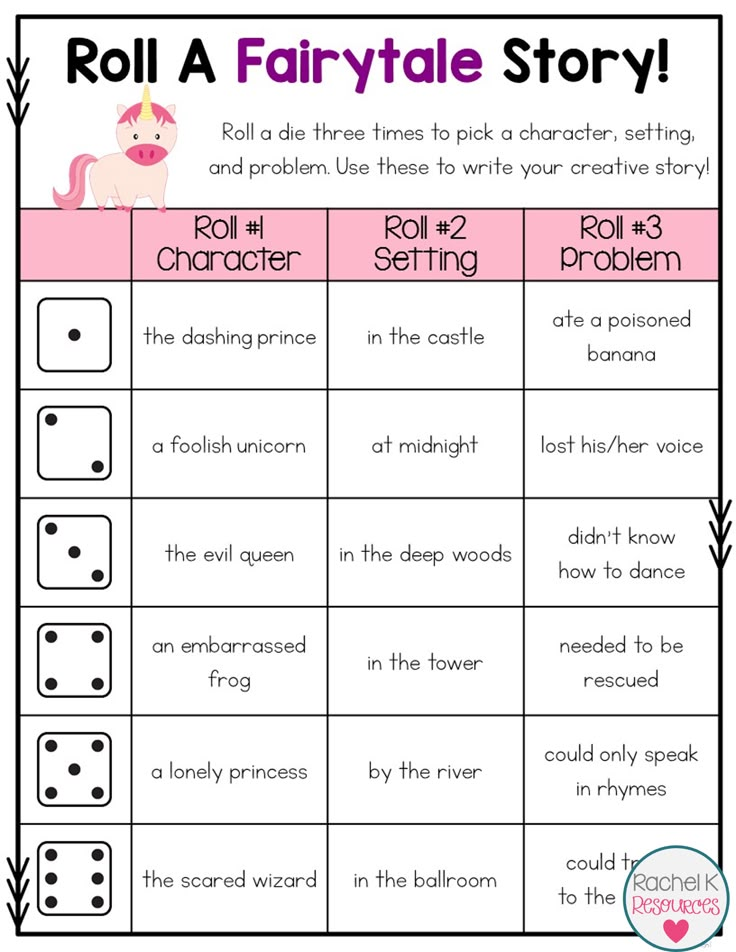

HOW TO DANCE IN OHIO is a documentary about a group of high-functioning teens and adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) preparing for, and attending, a spring formal in Columbus, Ohio. Under the therapeutic guidance of clinical psychologist Emilio Amigo and his staff, folks such as 16-year-old Marideth Bridges, 19-year-old Caroline McKenzie, and 22-year-old Jessica Sullivan work on learning how to communicate and interact with others in various social settings. With the help of their families, Dr. Amigo, and other professionals, they spend 12 weeks preparing for a formal dance at a local night club organized by the Amigo Counseling Center to help them learn how to cope with the many anxieties they have about participating in the event, and they practice how to socialize with other people. From working through their discomfort with trying to have a conversation to navigating their nervousness when choosing dresses, they all work their way toward the big event by facing their fears head-on.

From working through their discomfort with trying to have a conversation to navigating their nervousness when choosing dresses, they all work their way toward the big event by facing their fears head-on.

Is It Any Good?

The film offers a warmhearted, informative look at the routines, successes, and struggles people with Asperger's syndrome and high-functioning autism have when interacting with the mainstream world. But what stands out here is the self-awareness of the cast, who understand that they need extra help and coping mechanisms to function, and who do their best to articulate their anxieties and their desires. The insights offered by their parents and Dr. Amigo also offer a broader lens from which to see how they navigate their day-to-day lives.

Though both men and women are featured here, the fact that much of the story centers on three women leaves it feeling a bit uneven. However, this doesn't detract from the overall themes, which underscore how paralyzing basic social practices can be for people on the autism spectrum. It also shows how they, with the right support, can go to college, get jobs, and live independently. Overall, How to Dance In Ohio is a documentary that shows us how something as simple as a rite of passage can be life-changing to those who are challenged by life every day.

It also shows how they, with the right support, can go to college, get jobs, and live independently. Overall, How to Dance In Ohio is a documentary that shows us how something as simple as a rite of passage can be life-changing to those who are challenged by life every day.

Talk to Your Kids About ...

Families can talk about what it's like to live with autism spectrum disorder. What exactly is ASD? How can documentaries such as How to Dance In Ohio help people learn to understand it better?

Documentaries often inform or raise awareness about things people may not know much about. Does this documentary successfully do this about people living with ASD?

How does How to Dance In Ohio promote empathy and integrity? Why are these important character strengths?

Movie Details

- In theaters: January 25, 2015

- On DVD or streaming: September 27, 2016

- Cast: Emilio Amigo, Caroline McKenzie, Jessica Sullivan

- Director: Alexandra Shiva

- Studio: HBO

- Genre: Documentary

- Character Strengths: Empathy, Integrity

- Run time: 89 minutes

- MPAA rating: NR

- Last updated: March 2, 2022

Our Editors Recommend

-

Life, Animated

Unforgettable doc about autism, communication, Disney.

age 12+

-

Miss You Can Do It

Heartwarming docu digs into a pageant for disabled girls.

age 12+

-

The Sessions

Mature but deeply powerful look at sex and the disabled.

age 17+

-

The Theory of Everything

Hawking's brilliant mind comes to life in thoughtful drama.

age 14+

For kids who love inspiration

- Drama Movies That Tug at the Heartstrings

- Best Tween TV Shows

- See all recommended movie lists

Character Strengths

Find more movies that help kids build character.

-

Empathy

See all

-

Integrity

See all

Common Sense Media's unbiased ratings are created by expert reviewers and aren't influenced by the product's creators or by any of our funders, affiliates, or partners.

See how we rate

What kind of meme only in Ohio, Only in Ohio in tiktok under the track Swag Like Ohio

Meme videos Can’t Even X in Ohio or Only in Ohio (“Only in Ohio”), shot to the track of the hip-hoper Lil B Swag Like Ohio, have gained popularity on Tiktok. The template is suitable for frames with fictional monsters or creepy things or events that, according to tiktokers, can only happen in Ohio.

How the Can't Even X in Ohio or Only in Ohio meme appeared. nine0008 Starting in August 2022, videos under the names Can’t Even X in Ohio or Only in Ohio (“Only in Ohio”) went viral on TikTok. Initially, Memes about Ohio or Ohio Against The World ("Ohio against the world") became popular in early 2020. In the viral template, one of the astronauts points a gun at the other. The trend started with an August 2016 Tumblr post and a photo of a digital screen of a bus stop that read "Ohio will be eliminated. "

"

In archive and new templates, Ohio is an eerie and frightening place, a state about to take over the world. nine0003 A picture of a sign at a bus stop in Ohio

What an Ohio Only in Ohio meme. In 2022, TikTokers started filming videos about Ohio to the track of rapper Lil B Swag Like Ohio. Typically, the videos show fictional monsters running the streets, or strange things that can only happen in Ohio.

Ohio memes then went out of the box - comments about Ohio began to appear under random videos about ridiculous events or videos that cause disgust. For example, under the tiktok of mukbang bloggers. It seems that Ohio has become a place where madness accumulates. nine0003

nine0003

Screenshot from tiktokDinner Crazy in Ohio.

Ohio.

The most normal dish in Ohio.

Memes about Ohio have also spread in the Russian-language segment of tiktok.

In the search line of the social network, the Can’t Even X in Ohio or Only in Ohio meme is “googled” as “Ohio”, “Ohio brigade”, “Ohio brigade” and “Ohio meme”.

Screenshot from tiktokScreenshot from tiktokAt the time of writing, the #ohiomeme hashtag has over 28 million views. nine0003

Previously, Medialeaks talked about a meme with a boat floating on the river with calm music. In the template, girls show dialogues with guys who do not understand hints.

In another article by Medialeaks, you can read who OnlyFans model Molly Moon is, who shoots scary tiktok in the pixel horror genre.

Harvest: One story of contact improvisation. Nancy Stark Smith

Conversation with Nancy Stark Smith

on International contact festival in Freiburg, Germany, August 2005

When I heard that last year's conversation Nancy about the history of contact improvisation was recorded, I immediately asked, can we make a transcript. My idea was to contact improvisation took center stage in the next issue of Place magazine, to honor the global role of CI in the art of dance, society and creativity in general, to return to the history of the appearance of the magazine, and also to I could, as a teacher, have a fresh article to distribute to those students who sure that every dance containing a touch is a contact improvisation". nine0053 ( A.O. )

this moment. Perhaps from them we can form an overall picture. So, Of course, this is just my version of the story.

Perhaps from them we can form an overall picture. So, Of course, this is just my version of the story.

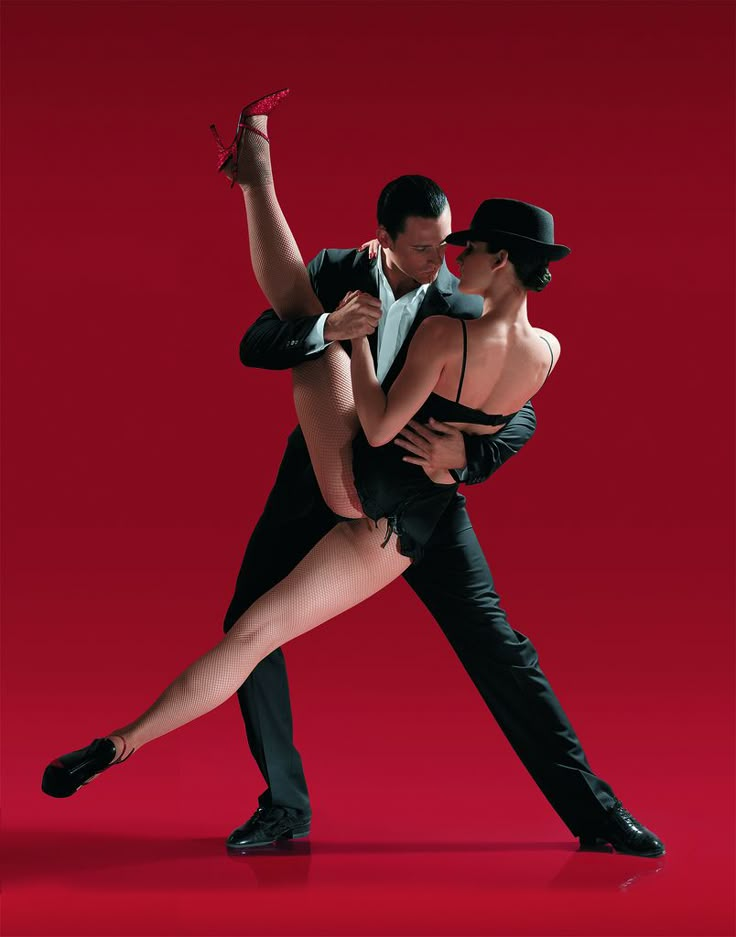

Contact improvisation was created American dancer and choreographer Steve Paxton in 1972. Steve was born and grew up in Arizona, and he brought many types of movement to his dance. He was athlete, gymnast, martial arts practitioner and modern dancer. He came to New York to study and dance with the modern dance troupe of José Limón, and also with other classical modern dance companies. nine0003 Steve Paxton solo moment, April 1976 Reunion performance, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Steve danced with a company in the early 1960s Merce Cunningham, a revolutionary choreographer who collaborated with the musician, composer and artist John Cage. Cage has made a significant contribution to the development new thinking and practice in dance and music in America and other countries. cage asked his protégé, Robert Ellis Dunn, accompanist Martha Graham, would he agree to teach a composition class in the studio Cunningham for young professional dancers. nine0003

nine0003

Bob Dunn inspired dancers to discover their ideas about dance and art. What is the movement in dance? Where can the performance take place? Where are the viewers looking from? What role does light or sound play? He encouraged them to try new things. As homework, they did many different performances. Trisha Brown performed a dance that took place simultaneously on several rooftops in Manhattan. Lucinda Childs created a performance in which audience members in a loft studio received audiotape instructions on what to look down on the street, while dancers on the sidewalk among pedestrians pointed to these objects. Now it does not seem so radical, but at that time it really was! Steve did a performance with a large group of people doing the "little dance" (which many of us do in CI), small reflex movements that happen when you stand still. It was called "State". nine0003

The dancers in Bob Dunn's class came up with a lot of interesting experiments and were very inspired by each other's suggestions. They wanted to share their work with the public and were looking for a place to perform. The priest at Judson Memorial Church in downtown New York offered them use the gym in this church. 1962 to 1965 Judson Dance Theater spent many exciting performance evenings there.

They wanted to share their work with the public and were looking for a place to perform. The priest at Judson Memorial Church in downtown New York offered them use the gym in this church. 1962 to 1965 Judson Dance Theater spent many exciting performance evenings there.

This period opened up new opportunities for what types of movement - foot, athletic, etc. - can be the material for the dance. Yvonne Reiner, an important artist in this dance revolution, made a project called Continuous Project - Altered Daily. Steve was in this group. One aspect of the project called into question leadership, which led to the fact that Yvonne ceased to be a leader and the group became team. This project turned into Grand Union - dance/theater/improvisational group, which included Steve Paxton, Yvonne, David Gordon, Trisha Brown, Barbara Dilly, Douglas Dunn, Nancy Green and others. They created spontaneous performances. They were all dancers different companies, but when they got together as Grand Union, they didn't have no plan, no set choreography. To create your impromptu dance theater they used everything that came to hand: props, lighting, music, text, costumes, movement. nine0003

To create your impromptu dance theater they used everything that came to hand: props, lighting, music, text, costumes, movement. nine0003

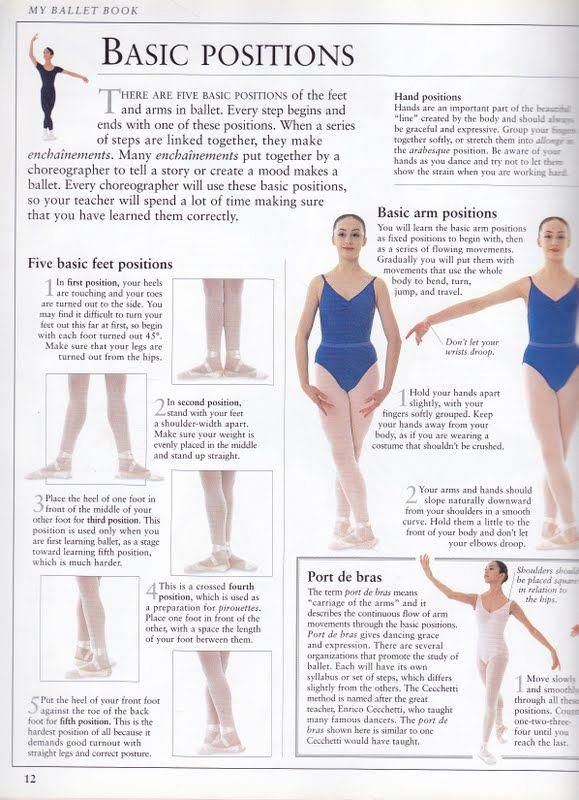

In my childhood and youth I did gymnastics and athletics. The dance was not very interesting to me - I saw dancers standing in front of a mirrored wall, looking at themselves and making small movements. I don't I knew what was so exciting about it.

David Woodberry (below) and Danny Lepkoff performing with East Coast Contact Company, Cunningham Studio, New York, 1977.While attending Oberlin College, Ohio, in early 1970s opening of this dance floor at the Judson Dance Theater was just beginning. In college, I still did gymnastics and other sports. sports, but when there was more and more attention paid to competitions, I began to lose interest. Then I thought that maybe I would become a doctor like mine. father, but even then I knew for sure that I would always be engaged in movement and writing. nine0003

During my first year of college, January, there was a dance project and someone suggested that I try it. It was a month-long residence with Twyla Tharp and her company, which included classes, rehearsals and performances. Twyla's work was avant-garde and was just beginning to acquire fame. She used a wide variety of movements and the workouts were physically and mentally tough. I was in awe of what it could be dance after working with her. Director of the modern dance troupe in Oberlin, Brenda Way, saw me and asked me to join the troupe. Over the next year I daily studied modern dance techniques, performed and began to study choreography. nine0003

It was a month-long residence with Twyla Tharp and her company, which included classes, rehearsals and performances. Twyla's work was avant-garde and was just beginning to acquire fame. She used a wide variety of movements and the workouts were physically and mentally tough. I was in awe of what it could be dance after working with her. Director of the modern dance troupe in Oberlin, Brenda Way, saw me and asked me to join the troupe. Over the next year I daily studied modern dance techniques, performed and began to study choreography. nine0003

Next January, 1972 Grand Union was invited to Oberlin College for a month's residency. Each member of the group held classes in technique, and at seven in the morning - in performance, at this time it was still dark and cold. This was called the "soft class". We went into beautiful old wooden gymnasium of the male gymnasium, and there was a chair by the door with a box of tissues and a small plate of chopped fruit. Everyone entering to the gym, took a napkin and a piece of fruit. Steve led us to stood still, did a "little dance" while we kind of fell asleep and woke up, and also did some breathing exercises similar to yoga. An hour later the sun was rising blew their nose, ate fruit - and that was the end of the lesson. My mind definitely opened up. I had no idea what we were doing, but I curious and somehow very touching. nine0003

Steve led us to stood still, did a "little dance" while we kind of fell asleep and woke up, and also did some breathing exercises similar to yoga. An hour later the sun was rising blew their nose, ate fruit - and that was the end of the lesson. My mind definitely opened up. I had no idea what we were doing, but I curious and somehow very touching. nine0003

Steve had a class in the afternoon performance, which he gave only for men. They used a very large old dusty mat in the gym. Steve also practiced aikido, tai chi, yoga and meditation. He was in Japan with Merce and there, as in New York, he studied oriental practices. It all became a part his dance and dance art.

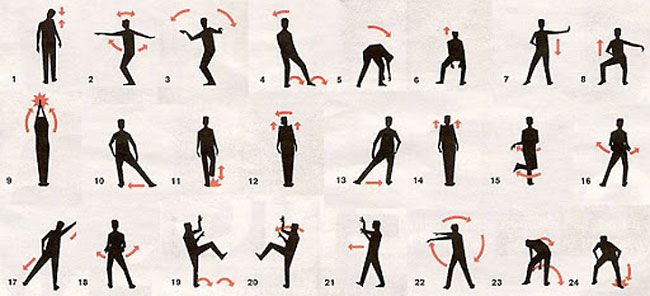

In the Fall After Newton video, Steve talks about about this work with men. He says he trained them "in extremes orientation and disorientation": they stood still and felt a small dance of balancing, and then practiced big falls and somersaults like in aikido. nine0003

At the end of the month, Steve and the men made performance called "Magnesium", which was shown in the gymnasium at the wrestling mate. Spectators watched the action from the treadmill upstairs. Men started by standing still, and then began to lose balance - falling in space, flattening on the mat, rolling, rising, gently colliding, sliding, falling, staggering through space as if they were drunk or something this kind, a beautiful gushing of men, maybe for ten minutes, which ended with another standing. nine0003

Spectators watched the action from the treadmill upstairs. Men started by standing still, and then began to lose balance - falling in space, flattening on the mat, rolling, rising, gently colliding, sliding, falling, staggering through space as if they were drunk or something this kind, a beautiful gushing of men, maybe for ten minutes, which ended with another standing. nine0003

I was in the hall at the time and was very touched. "Magnesium", "soft class", many new ideas about performance from David Gordon, Yvonne Rainer, Barbara Dilly - my mind was expanding. After Magnesium told Steve that if he ever did this to women, I would I'm glad if he tells me about it.

Steve Paxton (front) and Kurt Siddall dancing, Lisa Nelson filming (on the stairs). First performance of the Reunion series, January 1975, Natural Dance Studio, Oakland, CA In the spring of 1972, Steve began teaching at Bennington College in Vermont, where he continued to develop his ideas from Magnesium. He received a small grant and decided to form a group in New York in June 1972, to make a performance project. He invited several young dancers, whom he met in his travels as a guest artist, — from Oberlin (Kurt Siddall and myself), from the University of Rochester (Danny Lepkoff, David Woodberry and others), from Bennington (Nita Little, Laura Chapman and others), as well as several colleagues from New York. nine0003

He received a small grant and decided to form a group in New York in June 1972, to make a performance project. He invited several young dancers, whom he met in his travels as a guest artist, — from Oberlin (Kurt Siddall and myself), from the University of Rochester (Danny Lepkoff, David Woodberry and others), from Bennington (Nita Little, Laura Chapman and others), as well as several colleagues from New York. nine0003

We worked for a week in a loft studio in New York with a small blue wrestling mat. We worked all day long, long hours practicing a "little dance" during which Steve offered various looks: the skeleton, the flow of energy, the expansion of the lungs, bringing out the little sensations. We also practiced many techniques of somersaults forward, backward, aikido, invented rolls, somersaults down from a handstand, so that it is convenient to fall and roll in different directions.

Another thing we practiced: one a person stands with his back to the mat, and each in turn runs and throws himself at him, and he is trying to catch and somehow control the weight. This usually meant get on the floor and roll out of it. For hours to catch one, two, three, four... big and small people. On the sides were people to help if needed, like the spotters in the gym traditions. At that time we also danced head to head. nine0003

This usually meant get on the floor and roll out of it. For hours to catch one, two, three, four... big and small people. On the sides were people to help if needed, like the spotters in the gym traditions. At that time we also danced head to head. nine0003

We also danced on the mat as a duet: we tried different things, explored the possibilities, improvising in contact. The others watched intently. Sometimes the dances lasted ten, twenty, thirty minutes. We watched for hours, and then at some point you yourself had a chance. We just figured out what was possible and learned a lot from watching each other.

Another line of work was video. In 1972, when Magnesium happened, video was just getting portable. Bulky, but already portable. One person came to Oberlin to film Grand Union performances and accidentally filmed "Magnesium" thinking it was Grand Union. Steve saw this video and was very happy about this feedback. He invited this videographer, Steve Christensen, to join us in New York in June. So all our rehearsals and performances were recorded on video. Every night we watched them in the loft, where we lived all this time. It was complete immersion. nine0003 Steve Paxton watching Nita Little (in white pants) and Nancy Stark Smith perform at the Natural Dance Studio in Oakland, California during the first Reunion performances, 1975.

So all our rehearsals and performances were recorded on video. Every night we watched them in the loft, where we lived all this time. It was complete immersion. nine0003 Steve Paxton watching Nita Little (in white pants) and Nancy Stark Smith perform at the Natural Dance Studio in Oakland, California during the first Reunion performances, 1975.

After a week of practice, we moved to art gallery in downtown New York - John Weber Gallery, mated and performed five hours a day for a week. These were the first performances contact improvisation. Steve made an announcement in the form of postcards, where on the front The plan was a photo of a parachute jump from one walk in an amusement park on Coney Island. He also went to Chinatown and ordered biscuits with a fortune telling that said something like: "Come to John's Gallery Weber - contact improvisation", and we handed them out on the street. nine0003

When people came to the gallery, they could walk around and watch for five minutes, or sit down and watch some time, and maybe come back the next day. We practiced "little dance", rushed and picked up, there were also duets - almost all dances were initially duet. Sometimes, when we needed more space, we removed the mat. These the performances went on for five days, and then it was all over.

We practiced "little dance", rushed and picked up, there were also duets - almost all dances were initially duet. Sometimes, when we needed more space, we removed the mat. These the performances went on for five days, and then it was all over.

I often think that contact improvisation could just be a piece that Steve Paxton made at 1972, and on that would stop everything. Many artists have an idea, they collect people together, rehearse, show it, and that's it - move on to the next idea. So the fact that we are here today, 33 years later, with people from around the world practicing contact improvisation is very interesting.

Dancers from an event at the John Weber Gallery dispersed in different directions. I went to a summer retreat with a dance Oberlin team, and Nita left to teach dance at a summer school. Some of us were very inspired and wanted to continue learning dance, to to which we came with Steve. nine0003 June 1973 poster: Contact improvisation performance in Rome, Italy, at the L'Attico Gallery (video of Kurt Siddall (right) and Leon Felder performing in June 1972 at the John Weber Gallery).

The nature of this form is that She needs a partner and I think that's one of the biggest reasons why it has spread. If you could do it alone I don't know how it would go far ... To get a partner, you have to make it, you need to find a way to convey this form. Steve didn't stop people, he didn't said: "No, you must receive it only through me." Therefore, many of us tried to share, create their partners so we can continue dance. And contact improvisation began to grow. nine0003

Over the next few years, each time Steve performed in New York or elsewhere, contact improvisation was what he demonstrated as his work. He put together a small group to perform: myself, Kurt Siddall, Danny Lepkoff and David Woodberry were in the permanent staff, as well as some other people - in New York, on tour in California in January 1973 and in Rome (in the gallery L'Attico) in June 1973.

Three years later, in 1975, I graduated college and lived in Northern California. Steve called to see if I would go with him on a tour of the US Northwest. A few days earlier I was surprised found a flyer on a wall in San Francisco that said "Contact Improvisation" and a photograph of Wonder Woman. That was Nita Little's lesson! (I didn't know she was nearby.) I suggested that Steve meet Nita and Kurt for a reunion, which happened. We formed a company called Reunion, which gathered every year for several years with invited guests for the tour along the west coast, teaching classes and performances of contact improvisation.0003

A few days earlier I was surprised found a flyer on a wall in San Francisco that said "Contact Improvisation" and a photograph of Wonder Woman. That was Nita Little's lesson! (I didn't know she was nearby.) I suggested that Steve meet Nita and Kurt for a reunion, which happened. We formed a company called Reunion, which gathered every year for several years with invited guests for the tour along the west coast, teaching classes and performances of contact improvisation.0003

During the first Reunion tour in 1975, we heard about people who have seen us before and are now practicing CI. We also heard about some injuries, some of them quite serious. We have in the group had bruises, but nothing more. The safety issue was really a concern us. It has been suggested that our activities, especially such as "small dance" and delicate sensory work, provided a safer and more balanced interaction. But the people who just saw performance, trying to make big, spectacular movements without any preparation. nine0003

nine0003

So we thought that in order to to keep this work secure, we must copyright it, so that you have to learn this from us if you want to engage in contact improvisation. We prepared all the papers and almost signed them, refusing to last moment. I like to think that we were able to foresee our future and did not want to become the "contact cops" of a world where we would have to carry out police supervision and, having heard that someone is teaching somewhere, to check whether we know we them. And if not, tell them that they have no right to do this...

In addition, there was a feeling that if this interesting to people, they will do it anyway, just not naming it contact improvisation, and thus integrity and interconnectedness developing work will be lost. So instead of copyright we created newsletter, in which everyone involved in this work could write about what is happening to him: “I taught here ... But what I am learning ...” - that is, inviting people instead of pushing them away. We hoped that that if someone really works in a dangerous way, then people will not become participate in it. At worst, the job would get a bad rap. But there was also a premonition, a hope that if people looked at the source of the work, they will find a way to better information. nine0003

We hoped that that if someone really works in a dangerous way, then people will not become participate in it. At worst, the job would get a bad rap. But there was also a premonition, a hope that if people looked at the source of the work, they will find a way to better information. nine0003

So in 1975 the information the Contact Newsletter, which is currently a magazine Contact Quarterly (with CI newsletter in it) - to encourage people to stay connected and share with each other how they work. Liza Nelson joined me as co-editor in the late 1970s, and since then Since then we have been editing and producing the magazine together.

Nita Little contact class poster in the fall of 1974 in the San Francisco Bay Area After the first Reunion tour in 1975, the number contact numbers has increased significantly. Since then, many people have contributed significantly contribution to the development of the dance form as practitioners, teachers and performers. In addition, by the late 1970s and early 1980s in San Francisco, Minneapolis, Montreal, Vancouver, and New York City have produced several well-known contact companies, each of which has brought its own, special approach to heritage.

For me, our early performances were demonstration of a phenomenon. From the very beginning, people asked: “Well, is it dance?" Big question. It came from the mentality of dance as an art, its intent. It happened at a time in American and possibly world history, when established gender roles, power, etc. were called into question. this was a change in the way the dance was created, namely that it could be create in collaboration. Also, we had women lifting men; I didn’t really think about it then, but when we showed the work, people were overwhelmed by things like falling, being on the floor, or that men were sensitive to each other, that the women were strong, that the dancers were a little unmanageable - and the sheer physicality of it all. People were watching this job and were very excited and maybe a little embarrassed. nine0003

At the very beginning, Steve wanted to show this work to several of his fellow artists in New York. We had danced in the concert hall "Kitchen" in the very center of the city. We showed several videos and demonstrated the contact. There was Simone Forti, who said, "Hmm, it's something like art sports. We were delighted with this term - art sport. It's temporary solved some problems. And for some time this expression used quite often.

We showed several videos and demonstrated the contact. There was Simone Forti, who said, "Hmm, it's something like art sports. We were delighted with this term - art sport. It's temporary solved some problems. And for some time this expression used quite often.

There are no established pedagogical techniques or a certified way to teach contact. People themselves to a lot learn when they try to teach. Often they start by teaching what they they were taught, and then they change something a little in accordance with the characteristics of their students. They incorporate material from other work, they invent new things. This use of accompanying material can sometimes lead to confusion for students: how is contact different from Body-Mind Centering, or yoga, or other forms of partnership, or release techniques? nine0003

Thanks to this freedom of learning, people created a lot of learning materials — principles, exercises, languages, structures and formats. They become part of the canon, which is great; but this can create a problem if you think you need to be good at everything these techniques before you can dance contact improvisation. This not true. You are absolutely free once you have a clear understanding of basic prerequisites, develop several security skills and prepare your reflexes. You learn by doing. nine0003

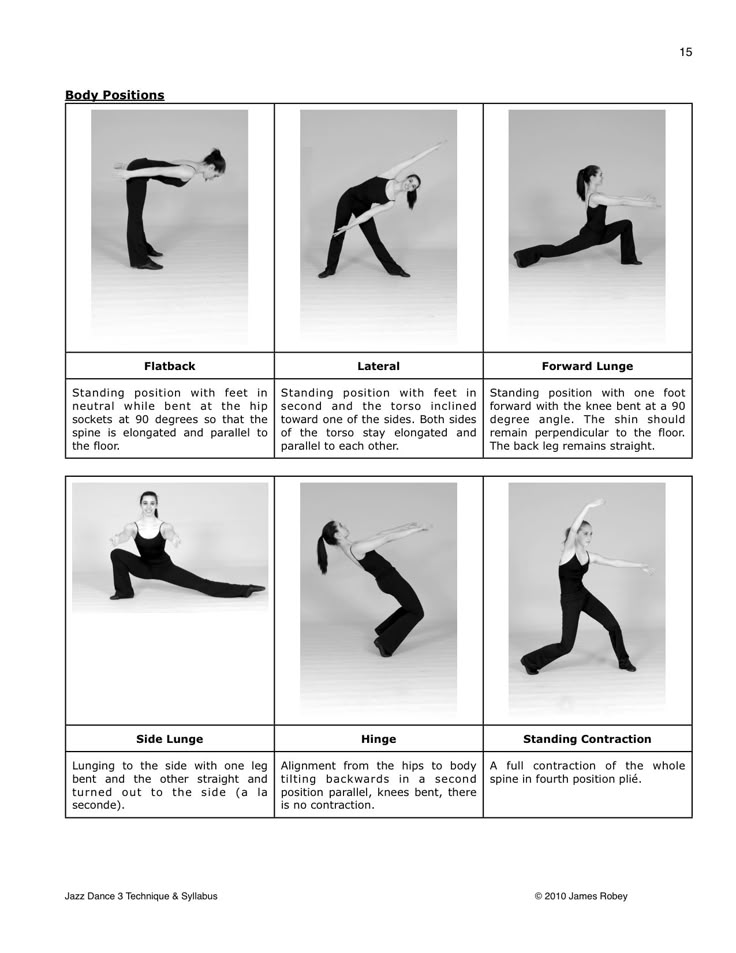

Teachers often teach what they like or what they are good at. They create an exercise to show how they do it. what they do is to give you easy access to it. Now there are many educational material - sliding, surfing, this or that support, a lot of principles and vocabulary. The question is how to digest it and improvise because improvisation is an integral part of the work - not just learn steps or movements and put them together, but meet, do, discover new things and be curious. nine0003 Contact performance flyer in Berkeley, California, early 1980s, with Andrew Harwood, Heidi Timm, Andy Warshaw, and Tom Trenda (image: Melanie Hedlund (top) and Heidi Timm meeting in Vancouver, British Columbia, 1979 d.)

Jams. This was a new phenomenon. I have in mind that there are no modern dance jams or ballet jams. Usually in The modern dance world has class, rehearsal and performance. I think that the jam model originated from Steve's martial arts background, from the dojo mentality where people of different levels practice together. Jem answered the question about how continue the practice. Perhaps someone set aside two hours on Sunday to practice with a few people. And then another thought, “Oh, that’s great. Let's go to the hot springs, where we can bathe in mineral waters, visit the sauna and dance all day”, “Good idea, let's go for the whole week. Let's start with a warm-up", etc.

Usually in The modern dance world has class, rehearsal and performance. I think that the jam model originated from Steve's martial arts background, from the dojo mentality where people of different levels practice together. Jem answered the question about how continue the practice. Perhaps someone set aside two hours on Sunday to practice with a few people. And then another thought, “Oh, that’s great. Let's go to the hot springs, where we can bathe in mineral waters, visit the sauna and dance all day”, “Good idea, let's go for the whole week. Let's start with a warm-up", etc.

Breitenbush Jam in Oregon was one of the first retreat jams at remote and very beautiful hot springs. A few years later, there was no longer enough space for everyone, so in Harbin Hot Springs in California has started another jam. And then people from the east coasts didn't want to go that far, so they had a jam on the east coast. And then the festivals began, and permanent bases (such as Arlequi in Spain and Earthdance in Massachusetts) began to hold regular workshops and CI activities. nine0003

nine0003

Since there is no teacher certification, the way thanks to which teachers stay in the know are meetings with each other friend, holding conferences, asking questions, establishing a dialogue. Instead of arguing over the official interpretation, teachers encouraged to communicate with each other: a number of teacher conferences have been developed and exchanges.

Throughout the development of contact mild anarchy prevailed in his "organization" - people freely defended their interests, and local and regional associations were formed to support for organized activities. nine0003

I think due to lack of certification there may be some problems, but at the moment it seems more useful to the form is that people are free to bring their own creative energy. This gives great value to the work.

Q&A

Man 1: What was the age of those who first participated in performances in New York? And when you started working with people who obviously weren't young and athletic?

1977 Reunion poster, Santa Monica, California (image: Steve Paxton and Nancy Stark Smith at the Gallery, Seattle, 1975) Nancy: I was nineteen, when I met Steve. He was thirty-two. Most of the dancers on the first CI speeches were twenty-year-old students, but there were also Steve's colleagues, who were about thirty.

He was thirty-two. Most of the dancers on the first CI speeches were twenty-year-old students, but there were also Steve's colleagues, who were about thirty.

At my first public classes, which I spent in California, there were very different people: artists, writers, filmmakers, sculptors - and very few dancers. There was one a famous poet named Diana di Prima, with whom I studied. She was not mover, but she was curious. However, she was unable to do somersaults. forward! I immediately ran into a problem. I couldn't learn CI like studied on her own. nine0003

I thought: “How can I teach contact improvisation if we can't roll forward?" I had to improvise! So I asked someone, "Could you stand like this way?" (kneel on all fours, like a table). Thus, Diana could just lie on the "table" - her partner - and feel, how her head hangs below her body. Then I thought, "Well, it's not that far anymore from continuing and supporting it until the end of the somersault." It worked so I used it again in class - backwards, sideways, all sorts of ways to get over the "table". So it was my first encounter with unfamiliar limits. I was happy that I succeeded convey the essence of the dance. The end result is a useful learning tool. nine0003

So it was my first encounter with unfamiliar limits. I was happy that I succeeded convey the essence of the dance. The end result is a useful learning tool. nine0003

Another example is the finger dance. Once I was at the opening of an exhibition in the museum, at that time I had been engaged in contact for several years. Someone asked me, “What are these dance things you do?” I usually say, "Well, that's like..." and just do it with them for a minute. But we were all in evening wear, holding martini glasses. So I said, "Put your glass down and just touch my finger." She touched my finger, and while I was trying to think of what to say next, our fingers (still touching) began to move in space. I said, "Okay, follow this!" We did this for a while and I thought, “Wow! It really looks like it!” I said, "Something like that, but the point of contact can be anywhere on your body." It has also become an appropriate way to communicate what a contact is. I called it "Ouija finger" 1 .

Dance work with people with disabilities began in the early to mid-1980s. At that time, several dancers in the UK, San Francisco and Eugene, Oregon were doing CI with people with various physical and mental disabilities.

Kevin Finnan and other dancers in England, those who received government grants had to go into the community and share their work - in prisons, hospitals and other institutions. They faced question: how can I share this type of dance with people who have severe physical limitations, such as with a person who could only move your eyes and thumb? But they found a solution and it was pretty exciting. nine0003

Alito Alessi and Karen Nelson brought together many of these dancers, as well as other people - both with limited opportunities, and without them, to a conference in Oregon to jointly explore such work in CI. Alito advanced enough in its approach, DanceAbility, and trainings for teachers. Others also continue their work in dance, research, jams and performances.

Man 2: Two questions. The way you describe the first experience of contact improvisation, seems to be a very serious and professional work of art. I would like to know when the elements of play and fun appeared? And the second question: what was the very early connection between contact improvisation and music? nine0053

Steve Paxton and Nancy Stark Smith Perform with Contact Group, Provincetown Art Association, Massachusetts, Summer 1977 Nancy: Communications contact and music at the very beginning was very simple: for many years it was not was. The connection of the body with gravity and other physical forces has its own synchronization. It is important to focus on this and study it on your own and in relationship with a partner. How fast you fall, how fast your partner falls he hesitates, he shifts, you fall. You must be ready to hear this timeliness. We as dancers have a habit of synchronizing with the music, so appropriate practice was required to establish this timeliness between us and these forces before we could add music as partner. Steve says in the Falling Newton video that we started use music to break the movement habits we have developed, dancing without music. nine0003

Steve says in the Falling Newton video that we started use music to break the movement habits we have developed, dancing without music. nine0003

Concerning seriousness and/or skill first meetings and performances - when did the game and fun begin? It started at the same time. It was fun from the start. It was a game.

It was serious. It was disciplined. We should have been careful for a long time. And the amazing thing in contact that we understood later, is that because of what you really need stay focused on the point of contact for a long time, it is became a kind of mind training, a kind of meditation practice. you follow beyond the point of contact, and if your mind wanders, you lose contact. And you realize that you are not focusing on the present, on the touch. Are you somewhere in another place. And then you come back. nine0003

Love affairs often happened between times affairs, because we opened up to each other for real. Partly due to 1960s, and also in connection with the flower-hipster sexual revolution, Steve wanted to make a clear distinction that this is not that. He needed draw a clearer line. But from the very beginning it was a lot of fun.

He needed draw a clearer line. But from the very beginning it was a lot of fun.

Woman 1: Where do you see contact improvisation in the future?

Nancy: Actually many places. It seems that it is already moving in many directions: as in areas of its practical application - in dance, theater, education, personal growth, recreation, and within oneself - her teaching and exchange formats within her. nine0003

The question is which coherence, coherence and integrity will have work as it will get bigger and go in different directions. Part of what I am I consider it my duty and interest in the creation of the Contact Quarterly magazine, is to constantly inform people about the development and display the diversity in this area, an attempt to bring clarity to practice and to hear different voices.

Lately I've been thinking about the "fundamental position” of contact improvisation. How is this activity defined? Now, when the work continues to expand in new directions, everything becomes it is more important to define and put into practice the fundamental provisions of the CI. nine0003

nine0003

Woman 2: Where do you see the connection between the contact improvisation and stage performance these days?

Nancy: In the very In the beginning, I felt that we were embodying a phenomenon. We even announced one of the first tours: “You will come. We'll show you what we do." Steve as an artist offered, and we followed him. This was his statement, his aesthetic. He urged us to wear training clothes; lighting was simple, not theatrical. Spectators usually sat at the edges of the hall; at the forefront it's almost never shown. nine0003

If someone is going to speak, they should take responsibility as an artist to offer what he offers. The right to execute is not inherited, but chosen. You make a choice like an artist to represent something - do you want to present a form as clean as possible or want to frame it with certain lighting, space or some other conditions. You have the same chance of great performance with contact, as with any dance form. The responsibility lies with the artists. nine0003

The responsibility lies with the artists. nine0003

Man 3: What was the reaction of the official dance world to contact in the 1970s? Was it considered art? And what Do you consider the aesthetics of art within contact improvisation?

Nancy: Contact was an avant-garde dance. If you really pushing the limits of the usual, then people committed to the traditional the way, for the most part, is not ready to accept it easily. It took place here respect, because Steve was respected as an artist, but they weren't sure how it fits into the big picture. Largely due to the fun and playfulness the contact may gain a reputation for being merely a "pleasant" social dance. As It's often said that it's more fun to do than to watch. nine0003

Contact performance has many complex aspects. You must focus on your partner and space used spherically - it radiates in all directions. It's not a form foreground, so it's a fun case for traditional theatres. How are you allow the power of the dance to radiate outward, while remaining in relationship with by yourself and your partners? In fact, it can be exciting spectacle.

How are you allow the power of the dance to radiate outward, while remaining in relationship with by yourself and your partners? In fact, it can be exciting spectacle.

The contact elements are currently in dance gene pool and appear in traditional choreography more and more. I think it is fair to say that the contact had a strong influence on modern choreography. It is taught in an increasing number of dance and theater academies. nine0003

But what is artistic about it? All this subjectively. I think contact improvisation is outstanding offer, and it's getting more and more outstanding all the time. Remarkably, that it remains remarkable no matter how the context changes and time. Steve's original structure, the way it was intended - that the dancers and physical forces cooperate to create a movement - interesting and beautiful, quite unpredictable and surprising, strange, risky, open, touching, curious, demanding and challenging. To me it sounds like good art. nine0003

Man 4: In the 1960s and 1970s, many creative people thought art could change society; were very optimistic expectation that another, better world is possible. You said that Steve was spending the difference between CI and hippie culture, free love. For you personally how much it was connected with a utopia, a hope or a desire, much more, than life or society, consciously or unconsciously? And how has it changed now?

You said that Steve was spending the difference between CI and hippie culture, free love. For you personally how much it was connected with a utopia, a hope or a desire, much more, than life or society, consciously or unconsciously? And how has it changed now?

Nancy: I couldn't even imagine something similar to contact improvisation. to me lucky to be there when Steve conceived it. I guess mine enthusiasm and participation contributed to its development. But Steve was a radical thinker man, and in his work political, social and human values. It dawned on me at a very specific age - I was nineteen years old and had not yet rebelled against much (except materialistic suburban upbringing). I was a teenager at the end of 1960s so I rode that wave.

Cynthia Novak, anthropologist and dancer, wrote dissertation (now the book Sharing the Dance) on contact as a subculture, about about what else was going on in America politically, socially, and artistically. plan around the time CI was born. The values of that period were or otherwise built into practice. It's like geology and rock formation - when something is formed, it takes into its structure the forces that are in it's time in the environment. I think contact contains a lot values of that period. Contact carries them and teaches them - even people who are not yet predisposed to them. To dance contact well, you need to relax to some extent. You must feel your weight, notice your feelings. You must listen. You must bring yourself to it. You can not overly controlling, but can't be too passive. Contact encourages people to discover and invent, collaborate, challenge, create within its limits. Did I mention generosity? There are many people, including me, who feel that this is peacekeeping work. But it could be too much other things, depending on what you emphasize in your practice. nine0003

plan around the time CI was born. The values of that period were or otherwise built into practice. It's like geology and rock formation - when something is formed, it takes into its structure the forces that are in it's time in the environment. I think contact contains a lot values of that period. Contact carries them and teaches them - even people who are not yet predisposed to them. To dance contact well, you need to relax to some extent. You must feel your weight, notice your feelings. You must listen. You must bring yourself to it. You can not overly controlling, but can't be too passive. Contact encourages people to discover and invent, collaborate, challenge, create within its limits. Did I mention generosity? There are many people, including me, who feel that this is peacekeeping work. But it could be too much other things, depending on what you emphasize in your practice. nine0003

Woman 3: How about improvisation? Now often are engaged in the choreography of performances that include contact. They jump in a certain way and say: "Oh, this is a contact jump." But where is improvisation?

They jump in a certain way and say: "Oh, this is a contact jump." But where is improvisation?

Nancy: When you watch or dance contact, new possibilities open up in your mind and you you can create a new partner element and set it as a choreography if want to. This is no longer contact improvisation, this is not improvisation, but maybe maybe she was inspired by the contact, or your imagination was thrown open thanks to him. nine0003

Contact improvisation is a structure, it is score for improvisation. You improvise all the time; you have a choice and you you use it; it's not fixed. However, vocabulary can become more and more fixed. Sometimes if you just change the consistency or don't do what the other person expects of you, you awaken them, and also himself to improvisation.

The question is, are we learning how to doing what our partner expects us to do, or how to be prepared be surprised and respond to what we did not expect? I would say the latter, but the first one also happens. You are an accomplice; it's a decision you make as a dancer. I AM I think this is part of the problem with such a large vocabulary. You can do a whole dance of very familiar movements. But you can also change them a little, to make them your own, customize them in the moment - by consistency, by phrase or by weight. It's like practicing scales on the piano before you start playing. There's nothing wrong with doing familiar things but once you've warmed up, you might want to open up and improvise a bit. nine0003

You are an accomplice; it's a decision you make as a dancer. I AM I think this is part of the problem with such a large vocabulary. You can do a whole dance of very familiar movements. But you can also change them a little, to make them your own, customize them in the moment - by consistency, by phrase or by weight. It's like practicing scales on the piano before you start playing. There's nothing wrong with doing familiar things but once you've warmed up, you might want to open up and improvise a bit. nine0003

True, with all this vocabulary, many dances may look similar, like some style. CQ has a great article by Mary Fulkerson in 1996 titled "Taking a glove without a hand". What's inside the form which gives it shape? If you take shape without what gives it shape what do you have?

This account of the history of contact improvisation last summer in Freiburg was notoriously limited - in time, context, memory, and my spur of the moment decisions. During its 35-year history, the contact has been formed and enriched by many people and events not touched upon in this conversation.