How to write down dance choreography

How I Write Down My Choreography – Dance Insight

This post may contain affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and make a purchase, we may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you. All affiliate links are marked with an asterisk.

Every choreographer has a different method for remembering what she taught her dancers. Some people keep it all in their head, many take a video at the end of every rehearsal, and some just ask the dancers to remind them, “how did that part go?”

It’s perfectly acceptable for a choreographer to forget her own choreography. It doesn’t mean she’s being lax or absent-minded, it just means that her focus is on making the dance look better. Unlike a performer who has to know every step by heart, a choreographer can stand at a distance and give critiques even if they don’t have every step memorized.

In the end, it will always be up to the dancers to remember the steps and all the intricacies of energy and focus that the choreographer puts in place. But sometimes when you’re working in a less-than-professional setting, you can’t expect your dancers to remember every little detail. The best example is working with kids. They need constant re-teaching, and they need someone to do it with them (depending on the age) before they will be good on their own.

Nothing is more embarrassing than doing the dance with your kids and messing up the steps because you forgot. It’s happened to me many times and I always feel like an inadequate teacher. (Thankfully my kids have never laughed at me.) So I have developed an organized way of writing down choreography, which is helpful for several reasons:

- It makes lesson planning easier. I can choreograph the whole dance at once, then just look back at my record as we learn week by week.

- It’s easy to resolve disputes. If one kid thinks the pose is on count 5 and one thinks the pose is on count 4, you can say, “Let’s check the book,” and settle it right then and there.

- Video is complicated and prone to malfunction. I consider myself a tech-savvy person and I still always have trouble using video in class. The camera takes precious minutes to set up in the first place, and if you want to play the video next week in class, you need to bring extra equipment and, again, take up precious minutes getting everything ready. That’s a lot of trouble just to check what count the pose was on.

- You get a record for future use. You’ll end up choreographing in a lot of different contexts throughout your life, and sometimes repurposing something old is easier than coming up with something new. When I ran out of ideas for my beginner ballet class’s holiday dance, I recalled a little “Deck the Halls” number that I had done with a private school in a different city. All I needed to do was pull up that choreography and rework it for different music and a slightly older class.

Whether you write down your choreography or not is entirely up to you and your teaching style. Note that this whole method assumes you do your choreography ahead of time, not in the moment during class. If you’re a come-up-with-it-on-the-spot person (more power to you because I find that impossible), I would not recommend taking time out of class to write it down! If you choreograph that way and really want a written record, I recommend taking a video and then notating based on the video after class. But whatever your style, if my method sounds like something worth pursuing, read on.

Note that this whole method assumes you do your choreography ahead of time, not in the moment during class. If you’re a come-up-with-it-on-the-spot person (more power to you because I find that impossible), I would not recommend taking time out of class to write it down! If you choreograph that way and really want a written record, I recommend taking a video and then notating based on the video after class. But whatever your style, if my method sounds like something worth pursuing, read on.

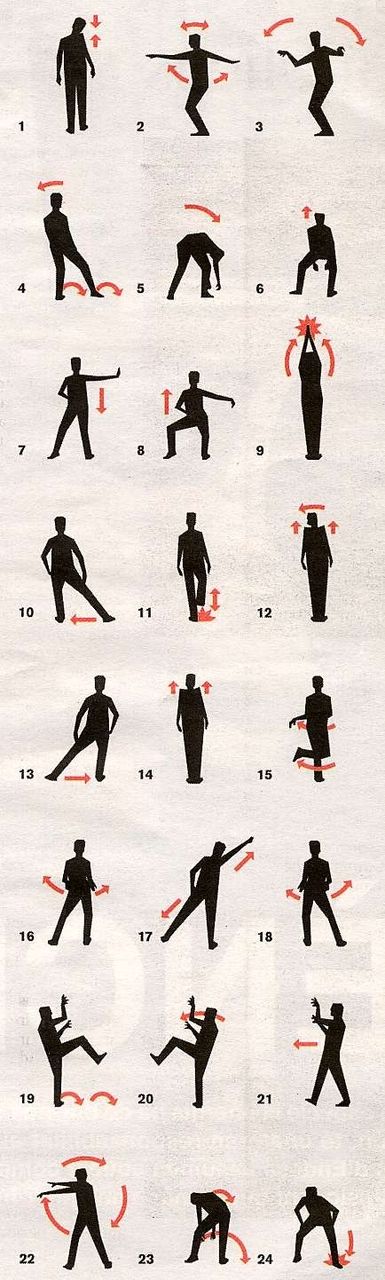

The key to writing down choreography without getting bogged down is to abbreviate as much as possible. I’ve developed a kind of shorthand to help me write complicated things quickly. Here’s a chart:

- SR – Stage right

- SL – Stage left

- US – Upstage

- DS – Downstage

- USL/USR – Upstage left/right

- DSL/DSR – Downstage left/right

- C2, C4, C6, C8 – Vaganova method “Corner 2,” “Corner 4,” etc.

- G1, G2, etc.

– Group 1, Group 2, etc.

– Group 1, Group 2, etc. - L1, L2, etc. – Line 1, Line 2, etc.

- b/w – Between

- b4 – Before

- tog – Together

- w/ – With

- w/o – Without

- b/c – Ball Change

- 2 – To

- ct – Count

- || – Parallel

- PDB – Pas de bouree or port des bras depending on the context

- RDJ – rond de jambe

- EDH/EDD – en des hours/en des dans

- R arm/R leg – Right arm/right leg

- L arm / L leg – Left arm/left leg

- FSB – Front, side, back

- FL/BL – Front leg/back leg

- USL/DSL can also be used for “Upstage leg” and “Downstage leg”

So if I wrote “L1 go SR2SL, L2 go SL2SR,” you would know what I’m saying, right? Takes a lot less time than writing it all out!

Formations and GroupsThe first thing I do when choreographing a dance is give each dancer a single letter abbreviation. Use the first letter of their first name whenever possible, but if you have a duplicate, use a letter that will help you remember who it is. For example, let’s say you have an Abby and an Ashlin. If one of them has an unusual last initial like Y, you could have one be “A” and the other be “Y”. Alternatively, you could take a unique letter from the middle of their name. For Abby and Ashlin, I would either do B and A or A and S. You could also do Ab and As, but I like single letters because it gives my formations a clean, consistent look.

For example, let’s say you have an Abby and an Ashlin. If one of them has an unusual last initial like Y, you could have one be “A” and the other be “Y”. Alternatively, you could take a unique letter from the middle of their name. For Abby and Ashlin, I would either do B and A or A and S. You could also do Ab and As, but I like single letters because it gives my formations a clean, consistent look.

At the top of your page, write each dancer’s name and their abbreviation. Then listen to the music all the way through and note how many 8-counts are in each section. In the example shown, 8.5 means that there are 8 1/2 eight-counts in the chorus (68 counts total).

Throughout the piece, you will note whenever the dancers change formation. Sometimes you may need to include arrows if motion is involved. Be sure to also include which side is the audience, and keep it consistent. Your sketch of the formation is also the place to note groups, even if they don’t occur right away. Notice in the example that the cannon doesn’t occur until after the unison phrase, but instead of drawing the whole formation again, all I need to write is “Cannon SL2SR as indicated.” (Click the picture to enlarge and read my handwriting.)

Notice in the example that the cannon doesn’t occur until after the unison phrase, but instead of drawing the whole formation again, all I need to write is “Cannon SL2SR as indicated.” (Click the picture to enlarge and read my handwriting.)

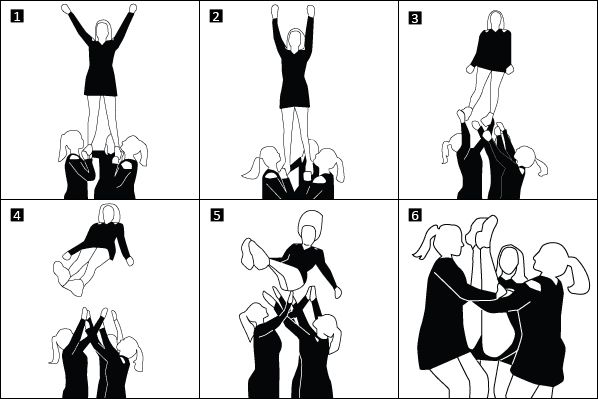

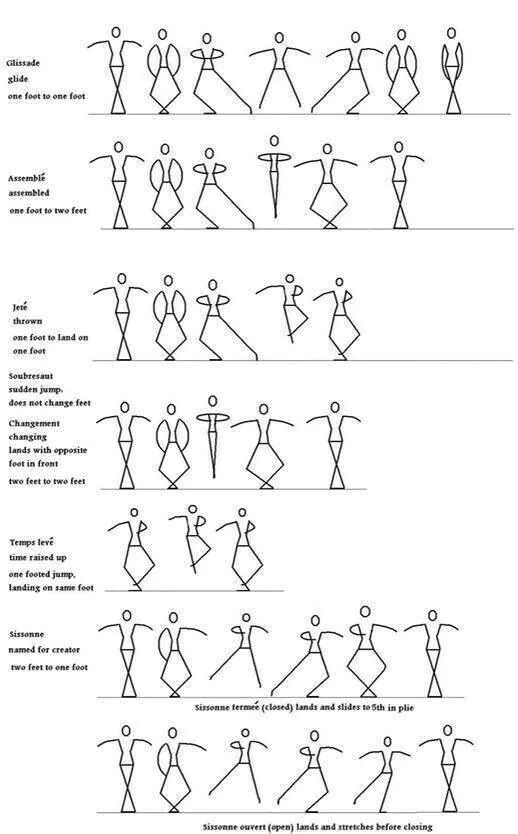

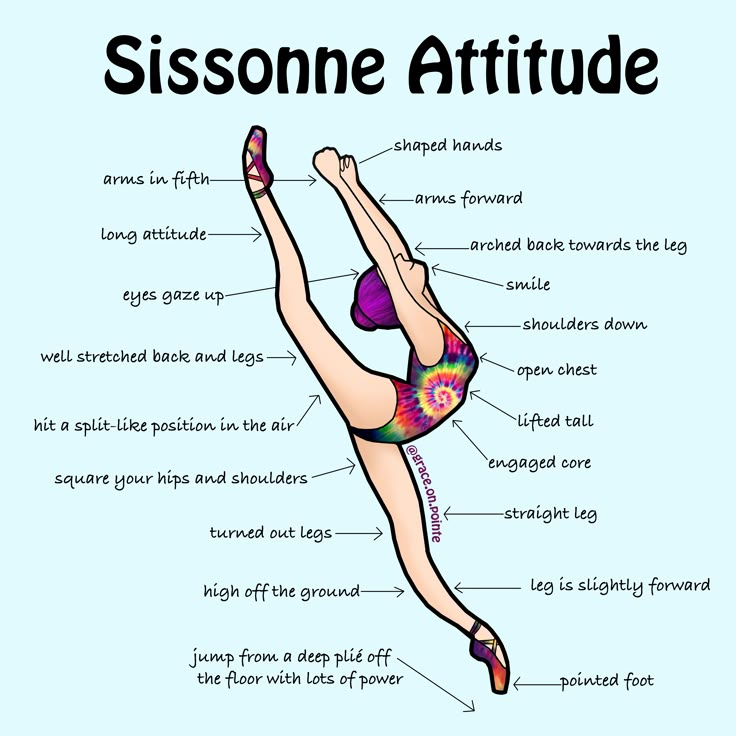

This is the part that no one in the history of dance has been able to figure out (And honestly, I haven’t really either). The history of dance notation is actually quite fascinating if you want to read more about it. The easiest dance form to notate is ballet, because there is a discreet number of positions and steps, each with a name. Begin fifth position croise facing corner 2, arms am bas. On count 1, tendu croise devant, right arm high, left arm al a seconde. As long as you know what method I’m teaching (Vaganova, otherwise you would be facing the other corner and the arms would be wrong), you know exactly what that means.

But what about modern, jazz, and other forms where sometimes movements don’t even have names? A typical modern teacher usually just yells out words like, “Head, roll, arm, leg!” The dancers might know what he’s talking about, but it won’t make much sense on paper.

I have only partially solved this problem by giving a name to everything I can. As long as you know what each name means, it will work for you. From my time as a show choir choreographer, I learned to be very specific about hand positions. There are only four options: Jazz hand, blades (fingers glued together), fists, and neutral (like blades but some space between the fingers).

Likewise, I gave names to a lot of common arm positions. “Suspenders” is when both hands are by the shoulders and the elbows are pointing out. You can be in “suspenders” with jazz hands, blades, fists, or neutral, and you can also be in “half suspenders,” where only one arm is in that position. I have a whole arsenal of made-up names, including “coffin,” “Captain America,” “tabletop,” “shampoo,” and “jungle.” Unique or even silly names work best because they help you remember what is what. Use words that work for you.

The point is to use as few words as possible. Use ballet terminology when applicable, even if you’re not doing ballet. (Just because you call it a “|| assemble” in your notes doesn’t mean you have to call it that when you’re teaching.) Ballet terminology is quite comprehensive for describing basic locomotor motions like jumping off one foot and landing on two (assemble), as well as positions relative to the audience like “croise.”

(Just because you call it a “|| assemble” in your notes doesn’t mean you have to call it that when you’re teaching.) Ballet terminology is quite comprehensive for describing basic locomotor motions like jumping off one foot and landing on two (assemble), as well as positions relative to the audience like “croise.”

Notice in the example above that I use commas to separate individual movements. At the end of the second line, I write “step R to half lunge hands to knee,” followed by a comma and a superscript 5 6. That means that you step to a lunge and move your hands to your knee at the same time, taking two counts, 5 6. If there had been a comma after “step R to half lunge,” then you would know that the hands don’t move until after you’ve lunged. Everything between a set of commas happens at the same time.

Occasionally it will make more sense to notate movements by the lyrics rather than the counts. I will write the lyrics above the steps they happen on, hyphenating syllables when necessary.

You never want to write more words than you have to, and an easy way to cut down on words is to not write out repeats. If a repeat happens right then and there, I’ll use square brackets, like this:

[Tendu, close, tendu, close, degage, pique, pique, close plie] en crois

[pdb R, pdb L, single pirouette edh, step R L] 3x

Other times, you have to go back to an earlier part of the dance. I’ve shown a simple example here. Notate your starting and ending points with letters, then all you have to do is write “Repeat A to B.”

Those are the basics of my choreography notation system. Keep in mind, this isn’t supposed to be a universal system that everyone understands (wouldn’t it be nice if we could write down choreography like we can for music?). It’s supposed to be a personalized method for you to write down your creation, then come back to it years later and still understand it.

I hope you’re able to adapt my method to your needs and start preserving your choreography in a tangible form! If you want more details or have specific questions, let me know in the comments!

Here is the full page for easy reference: (This is not a real dance, by the way. It was created for the purposes of this blog post. The song lyrics are also fictional.)

It was created for the purposes of this blog post. The song lyrics are also fictional.)

How to Write Choreography - Mandi's Lindy Hop Blog

I was lucky to have my very first choreography class with Eddie Jansson of the original Rhythm Hotshots. The class wasn’t just about learning choreography–it was about learning to write and memorize choreography. The method that he taught was excellent and I still use it to this day.

The first thing to do is to pick your music. Once you have the music, it’s time to chart it.

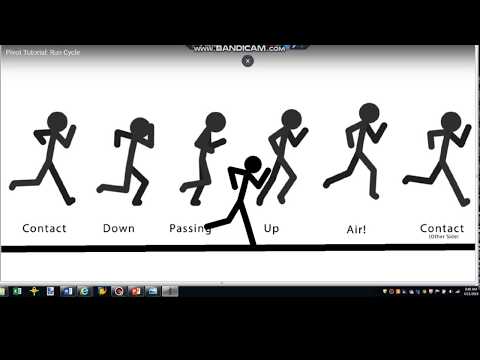

Sit down with a piece of lined paper and a pen and listen. Every time the music completes 8 counts, make a vertical mark along the lined paper. Leave some space before the next mark. When it’s the end of a phrase and a new phrase is beginning, move to the next line down.

Listen to the song twice to ensure that you’ve made the marks in the appropriate places.

Use the marks that you’ve made to create a chart. Each horizontal line should represent a phrase of the music.

A standard 32 beat phrase of music, which is made of four 8-counts, will have four rectangles on each line. A standard chorus would look like this:

After you’ve charted an entire standard song, if it had 4 chorus’ it might look like this:

Once you have your empty chart, it’s nice to listen again and make a little mark in places in the song where something interesting is taking place musically, such as a very punchy break, or an instrumental section.Now that you know the song and you have a nice visual representation of it, Then you can get started with your actual choreography.

Now that you know the song and you have a nice visual representation of it, you can get started with your actual choreography. It might make sense to start writing at the beginning, or it might make sense to create your most exciting sequences first, to match the highlights in the music.

Here are some examples of choreography that’s been charted.

This is what the first chorus of the Shim Sham would look like:

| Right Shim Sham | Left Shim Sham | Right Shim Sham | Shim Sham Break |

| Push, Push, Crossover Right | Push, Push, Crossover Left | Push, Push, Crossover Right | Double Cross Over |

| Tack Annie | Tack Annie | Tack Annie | Shim Sham Break |

| Half Break | Shim Sham Break | Half Break | Shim Sham Break |

Then for Chorus #2 – freezes in place of the Shim Sham breaks

| Right Shim Sham | Left Shim Sham | Right Shim Sham | FREEZE |

| Push, Push, Crossover Right | Push, Push, Crossover Left | Push, Push, Crossover Right | Double Cross Over |

| Tack Annie | Tack Annie | Tack Annie | FREEZE |

| Half Break | FREEZE | Half Break | FREEZE |

| Boogie Forward | Boogie Back | Boogie Forward | Boogie Back |

| Shorty George | Jump Boogie Back | Shorty George | Jump Boogie Back |

When you’re writing choreography that isn’t just made up of 8-counts (which is much more dynamic and interesting) you might make a chorus of the music look something like this:

In this example, I’ve broken up each phrase in smaller fractions to represent the 6-count moves vs. the 8-count moves.

the 8-count moves.

When Eddie first taught us to use this method, he had us chart out the first chorus of the song Leap Frog. This is a great, exciting song to use for your first stab at choreography. Then we worked in groups to choreograph that first chorus of music and performed for one another.

This is an example of a much more complicated, irregular choreography that I wrote many years ago. I still remember it because the song was so irregular and the visual stayed in my mind. This is for the song Hallelujah I Just Love Her So which is based on a blues structure but there are a mix of full 12-bar phrases and 8-bar phrases. This old choreography chart also shows how helpful it is to get a visual of the entire song so that you can know where you are within the larger piece of music.

Here’s our classic “Frankie Choreo” danced to Duke Ellington’s, Let’s Get Together:

And here it is in action!

Writing choreography doesn’t have to be difficult, and you have to start somewhere. Try this method to ensure that you’re basing the choreography on the music as the first priority. It’s a great learning experience. Oh, and as Eddie taught us, don’t forget to always take a bow at the end of your performance to thank the audience for gracing you with their attention! Good luck.

Dance recording | Belcanto.ru

The system of symbols for choreography was originally called choreography (this term was introduced in 1700 by the dance teacher R. Feuillet, France). The need for Z. t. has existed for a long time. It is believed that the ancient Egyptians used hieroglyphs for this purpose. In the temples of South In India, sculptural images of 108 karanas have been preserved - the main provisions of the Indus. classical dance. The Romans used a system of recording gestures used in pantomime. In Zap. In Europe, attempts to describe and record dances have been preserved in manuscripts of the 15th century. (Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro, 1463; anonymous, so-called "golden" manuscript of the bass dances of Margaret of Austria), where, just as in one of the first printed works on the dance, attributed to M. Toulouse (c. 1499), the literal way of designating pas was used (the first letter of the dance term usually served as a designation of movement). This method was most successfully applied by Tuano Arbo ("Orchesography", 1588), who supplemented it with descriptions and drawings. In book. F. Caroso "Dancer" (Venice, vol. 1-2, 1581) was the first attempt to convey the scheme of the dance procession in graphic. form. Feuille in his work "Choreography, or the Art of Recording a Dance..." (1700) used the principles developed by his teacher P. Beauchamp, choreographer of the Royal Academy of Music in Paris. Introduced by Feuille graphic. the recording system, based on the symbol of the movement, lasted until the end.

In Zap. In Europe, attempts to describe and record dances have been preserved in manuscripts of the 15th century. (Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro, 1463; anonymous, so-called "golden" manuscript of the bass dances of Margaret of Austria), where, just as in one of the first printed works on the dance, attributed to M. Toulouse (c. 1499), the literal way of designating pas was used (the first letter of the dance term usually served as a designation of movement). This method was most successfully applied by Tuano Arbo ("Orchesography", 1588), who supplemented it with descriptions and drawings. In book. F. Caroso "Dancer" (Venice, vol. 1-2, 1581) was the first attempt to convey the scheme of the dance procession in graphic. form. Feuille in his work "Choreography, or the Art of Recording a Dance..." (1700) used the principles developed by his teacher P. Beauchamp, choreographer of the Royal Academy of Music in Paris. Introduced by Feuille graphic. the recording system, based on the symbol of the movement, lasted until the end. 18th century (in the first half of the 18th century, the French dance master P. Rameau developed it, supplementing it with the notation of hand movements and musical size). In the beginning. 19in. with the complication of dance. technology, there was a need for a more accurate transmission of movement along the vertical, in connection with which they began to use schematic. image of a moving person. In 1852 the French ballet. A. Saint-Leon in the book. "Stenochoregraphy ..." made an attempt to show the development of dance in space, introducing the designation of the wings (plans of the stage) and indicating for each movement of the legs the corresponding coordinated movements of the body, head and hands.

18th century (in the first half of the 18th century, the French dance master P. Rameau developed it, supplementing it with the notation of hand movements and musical size). In the beginning. 19in. with the complication of dance. technology, there was a need for a more accurate transmission of movement along the vertical, in connection with which they began to use schematic. image of a moving person. In 1852 the French ballet. A. Saint-Leon in the book. "Stenochoregraphy ..." made an attempt to show the development of dance in space, introducing the designation of the wings (plans of the stage) and indicating for each movement of the legs the corresponding coordinated movements of the body, head and hands.

In Russia, the system of Saint-Leon was developed and improved in the work of A. Ya. Zorn "Grammar of dance art and choreography" (1890). Means. of interest is the Z. t. system, created by the artist St. Petersburg. ballet by V. I. Stepanov, who developed the principles of linear notation (signs were located on the stave). Stepanov introduced the concept of a degree (the amount of flexion and extension of the joints) into the Z. t., and successfully fixed the rhythm. mise-en-scenes and movement plans. Stepanov's recording system was taught by ballet. A. A. Gorsky in the ballet class Petersburg. theatre. schools. According to this system, 27 ballets were recorded at the Mariinsky Theater.

Stepanov introduced the concept of a degree (the amount of flexion and extension of the joints) into the Z. t., and successfully fixed the rhythm. mise-en-scenes and movement plans. Stepanov's recording system was taught by ballet. A. A. Gorsky in the ballet class Petersburg. theatre. schools. According to this system, 27 ballets were recorded at the Mariinsky Theater.

20th century attempts continued in different countries to create a system of Z. t., satisfying modern. requirements: transmission of the direction, length, width and shape of the step, the features of setting and taking off the legs from the ground, the positions of the arms, torso, head; rhythm, tempo and dynamic. features of movement in its relationship with music; the transfer of mise-en-scenes and a plan for the movements of the characters on the site, as well as the movements of all parts of the body in decomp. planes. In some cases, the systems were based, as before, on linear notation (J. Kula, 1927; P. Konta, 1931) or on the record using the image of a moving man (S. Babica, 1939). New systems also use conventional signs (J. Morris, 1928, etc.). The most widespread are two systems: developed in Germany by R. von Laban and R. and J. Benesh in the UK. Laban based his system on the principles of the theory of expressive gesture developed by F. Delsarte (France). Laban called his analysis of the forms of movement "choreutics" ("Choreography", 1926). In the future, it established itself under the name "Labanoteyshen". In the 40s. Laban and his followers continued to develop this system. At 1940 in New York, the Dance Recording Bureau was created, one of the founders of which was E. Hutchinson, the largest contemporary. specialist in Z. t. The Bureau organized the recording of many. productions (J. Balanchine, H. Holm, D. Humphrey). In the UK, the system of R. and J. Benes, published in 1956, has become widespread. It is based on the conventions for the positions of body parts in relation to the stage. space. Stan with a dance recording. movements is placed under the stave.

Babica, 1939). New systems also use conventional signs (J. Morris, 1928, etc.). The most widespread are two systems: developed in Germany by R. von Laban and R. and J. Benesh in the UK. Laban based his system on the principles of the theory of expressive gesture developed by F. Delsarte (France). Laban called his analysis of the forms of movement "choreutics" ("Choreography", 1926). In the future, it established itself under the name "Labanoteyshen". In the 40s. Laban and his followers continued to develop this system. At 1940 in New York, the Dance Recording Bureau was created, one of the founders of which was E. Hutchinson, the largest contemporary. specialist in Z. t. The Bureau organized the recording of many. productions (J. Balanchine, H. Holm, D. Humphrey). In the UK, the system of R. and J. Benes, published in 1956, has become widespread. It is based on the conventions for the positions of body parts in relation to the stage. space. Stan with a dance recording. movements is placed under the stave. The Benes system is studied in English. ballet schools (including the Royal Ballet School). Benesi was created at the beginning. 60s Institute of Choreology, which trains specialists in Z. t. Leading Western European. troupes have "choreologists" on staff who record new performances.

The Benes system is studied in English. ballet schools (including the Royal Ballet School). Benesi was created at the beginning. 60s Institute of Choreology, which trains specialists in Z. t. Leading Western European. troupes have "choreologists" on staff who record new performances.

In the USSR, the development of decomp. ways Z.t. engaged in the All-Union House Nar. creativity to them. N. K. Krupskaya in Moscow, Republican Houses of Nar. creativity and Vseros. theatre. society. Filming is widely used. The most common descriptive way of fixing the dance, especially when recording nar. dancing. In 1940, S. S. Lisitsian's book A Record of Movement was published, which outlines the history of Z. t., developed an original system, and gave an extensive bibliography. In 1980, the Ministry of Culture of the USSR adopted the technique of Z. t., which is the basis of the copyright of choreographers.

Ballet. Encyclopedia, SE, 1981

recommend

see also

Chamber Ensemble Terms and concepts

Naples Cities

Melos Terms and concepts

Offertory Church music

Introductory tone Terms and concepts

Septet Terms and concepts

Consonance Terms and concepts

Ashgabat Cities

Falsetto Opera, vocals, singing

Grand opera Opera, vocals, singing

Advertising

Theatre.

• Body Recording and Body Recording

• Body Recording and Body Recording Vaslav Nijinsky in The Afternoon of a Faun, Diaghilev's Russian Ballet, Paris, 1912

In a classical ballet focused on self-preservation, the role of choreographic notation is simple and clear, but Theatre. interested in the adventures of notation in "non-ballet"

Attempts to record dance in the same way as music, so that anyone familiar with choreographic writing could read, evaluate and perform what was written, have been known since the end of the 15th century. Choreographers saw here a way to bring their creations to the widest possible audience and preserve them for posterity in integrity, theaters and dancers - a practical way to reduce costs by minimizing the presence of a choreographer when staging or a dance teacher when preparing performances.

Notation in ballet

Choreographic notation flourished in 18th century France, and this is easy to explain, given the tradition of lavish festivities and the passion for systematization in all areas of art. In 1700, Raoul-Auger Feyet's treatise "Chorégraphie" was published, that is, literally "recording of the dance." Although Feyet was accused of stealing the intellectual property of the dancer Beauchamp, the very fate of his system reflects the high status of dance at the French court: it has withstood many reprints; are also set out in Diderot's Encyclopedia. Feyet's system visually reflected the already existing dance vocabulary. It was necessary to know ballet terms in order to use the system (developed by another dancer, Favier, the terminology-independent notation system given in the same Encyclopedia had no practical use). Around 1780, the last book on the Feyet system was published (“Treatise on the Art of Dance” by Malpier), after the French Revolution, no more appeared: the system was a thing of the past along with the court culture that gave rise to it.

In 1700, Raoul-Auger Feyet's treatise "Chorégraphie" was published, that is, literally "recording of the dance." Although Feyet was accused of stealing the intellectual property of the dancer Beauchamp, the very fate of his system reflects the high status of dance at the French court: it has withstood many reprints; are also set out in Diderot's Encyclopedia. Feyet's system visually reflected the already existing dance vocabulary. It was necessary to know ballet terms in order to use the system (developed by another dancer, Favier, the terminology-independent notation system given in the same Encyclopedia had no practical use). Around 1780, the last book on the Feyet system was published (“Treatise on the Art of Dance” by Malpier), after the French Revolution, no more appeared: the system was a thing of the past along with the court culture that gave rise to it.

The theoretical thought of the choreographers of the 19th century linked the invention of a new, more advanced system of notation with an in-depth study of anatomy and patterns of movement. Carlo Blasis wrote about this in his treatise of 1820, and already in 1831-1832, the French-English teacher Edward Elcock Teller not only entered into an argument with the generally accepted French classification of positions and movements, but also proposed a notation system, for understanding which knowledge of terminology was not necessary. Another thing is that in the 19th century, notation lost its practical appeal, because the accuracy (authenticity) of both fixation and reproduction ceased to be an encouraged value. The ballet spread through plagiarism: the choreographers came to the Paris premiere, memorized the performance with spectacular dances and staged it, as they remember, at the duty station. So, for example, "Pas de trois pour M. Albert" to the music of Carafa di Colobrano, added in 1828 to the ballet "Paul and Virginia" for the first dancer Albert, came from the Paris Opera to Copenhagen, becoming part of Bournonville's early ballet "Soldier and peasant" (1829), and to Moscow, where these notes were signed as the property of the dancer Richard Sr.

Carlo Blasis wrote about this in his treatise of 1820, and already in 1831-1832, the French-English teacher Edward Elcock Teller not only entered into an argument with the generally accepted French classification of positions and movements, but also proposed a notation system, for understanding which knowledge of terminology was not necessary. Another thing is that in the 19th century, notation lost its practical appeal, because the accuracy (authenticity) of both fixation and reproduction ceased to be an encouraged value. The ballet spread through plagiarism: the choreographers came to the Paris premiere, memorized the performance with spectacular dances and staged it, as they remember, at the duty station. So, for example, "Pas de trois pour M. Albert" to the music of Carafa di Colobrano, added in 1828 to the ballet "Paul and Virginia" for the first dancer Albert, came from the Paris Opera to Copenhagen, becoming part of Bournonville's early ballet "Soldier and peasant" (1829), and to Moscow, where these notes were signed as the property of the dancer Richard Sr. The choreography was recognized as intellectual property only in 1862 at the trial of Jules Perrot against Marius Petipa (Petipa staged a dance created by Perro without his permission and indication of the name). In this process, interestingly, Perrault's lawyer involved as a witness and expert Arthur Saint-Leon, a multi-talented choreographer, dancer, musician and author of the system of notation set forth by him in the book Stenochoreography (1852). The court was interested in the testimony of Saint-Leon as a professional and an eyewitness who had been in St. Petersburg. Of course, there was no talk of notation as a document proving authorship. In practical terms, it was easier and faster for Saint-Leon’s colleagues (it doesn’t matter whether they composed their own or transferred other people’s ballets) to write names or abbreviations of movements over the notes, explaining them with drawings and some special signs, as did the Danish classic August Bournonville or Henri Justaman, who settled down in Cologne, former choreographer of theaters in Lyon, Brussels and Paris.

The choreography was recognized as intellectual property only in 1862 at the trial of Jules Perrot against Marius Petipa (Petipa staged a dance created by Perro without his permission and indication of the name). In this process, interestingly, Perrault's lawyer involved as a witness and expert Arthur Saint-Leon, a multi-talented choreographer, dancer, musician and author of the system of notation set forth by him in the book Stenochoreography (1852). The court was interested in the testimony of Saint-Leon as a professional and an eyewitness who had been in St. Petersburg. Of course, there was no talk of notation as a document proving authorship. In practical terms, it was easier and faster for Saint-Leon’s colleagues (it doesn’t matter whether they composed their own or transferred other people’s ballets) to write names or abbreviations of movements over the notes, explaining them with drawings and some special signs, as did the Danish classic August Bournonville or Henri Justaman, who settled down in Cologne, former choreographer of theaters in Lyon, Brussels and Paris.

So did Marius Petipa, chief choreographer of the Imperial Theaters from 1869 to 1903. Petipa was interested in systems of notation, his archives contained sheets from Faye's treatise, but he himself, as he said, was easier to compose anew than to wait for the decipherment of the recorded dance. In the 1890s, the aged master staged ballets that became absolute classics: Sleeping Beauty (1890), Swan Lake (1895, together with Lev Ivanov) and Raymonda (1898). But in these years, much more acute than before, the problem arose of maintaining the overgrown ballet economy in order (resumptions, introductions, dances in operas, etc.), which was becoming increasingly difficult for an elderly and not very healthy person. Moreover, Petipa's own ballets, given his vanity and authority, had to be resumed with the utmost accuracy. In attempts to apply to Petipa's creations the same methods that he himself used in relation to the works of other choreographers, he saw a personal insult and settling scores on the part of the directorate, an example of which is the scathing comments in his memoirs about the renewal of his Don Quixote in Moscow (1900) and Petersburg (1902), carried out by Alexander Gorsky.

This, apparently, explains the interest with which the directorate of the Imperial Theaters in the early 1890s reacted to "one talented invention" (the words of the theater official Pavel Pchelnikov) - a dance recording system proposed by the young corps de ballet dancer Vladimir Stepanov. “While still a graduate of the Imperial St. Petersburg Theater School, he more than once stopped to think why human speech and sounds have recording methods, but movements do not,” wrote Gorsky. - Developing this idea and analyzing the imaginary process of the emergence of the alphabet and musical notes, he decided to compile the alphabet of the movements of the human body, basing it on anatomical data, under the guidance of Professor Lesgaft, and developing it in Paris, according to the instructions of Professor Charcot "[Gorsky A.A. Table signs for recording the movements of the human body according to the system of the Artist of the Imperial St. Petersburg Theaters V. I. Stepanov. St. Petersburg, [1899]. pp. 3–4].

pp. 3–4].

Stepanov's system embodied the dream of a choreographic recording similar to a musical one. The type of recording - three staves, similar to musical ones: the lower one for recording the movements of the legs, the middle one for recording the movements of the legs, and the upper one for the head and body - resembled some bell ringing notations (and perhaps they were prompted by them). Notes and additional signs indicated body positions, so the system did not depend on terminology. It was approved for use by a commission of choreographers and leading artists. Probably, if Stepanov invented some other, more traditional system, the directorate of the Imperial Theaters would also approve of it. One way or another, thanks to the assistance of the administration, for the first time in history, choreographic notation was introduced into the curriculum of the Imperial Theater School. A reward was also established for recording ballets in the theater, which created the conditions for its professional development.

Exercise No. 111 from the book “Choreography. Examples for reading. Animation according to choreographic notation – Sergei Konaev

From Stepanov to Nizhinsky

What, however, does this have to do with free dance in all its forms, with what is easiest to define from the opposite: everything that is not ballet?

Stepanov's system is described in the book "Alphabet des mouvements du corps humain: Essai d'enregistrement des mouvements du corps humain au moyen des signes musicaux". It was published in 1892 in French and practically unknown in Russia. The most striking thing in it is the preface, in which the Imperial Ballet itself, where Stepanov served and which provided organizational support to his quest, is given only one paragraph. Stepanov is looking for "a rigorous method of recording movement" to help "an artist create an impeccable theory of choreography for the development of ballet art, a theory that would allow one to navigate in an innumerable set of movements of the body, which would establish the laws of harmony of movements" [Alphabet Des Mouvements Du Corps Humain: Essai D'Enregistrement Des Mouvements Du Corps Humain Au Moyen Des Signes Musicaux. Paris, 1892. P. V-VI].

Paris, 1892. P. V-VI].

This set of movements has no hierarchy, they are equal in rights and equally important for the notator-researcher. It is as interesting for Stepanov to record the dances of Marius Petipa as it is to try to express the plasticity of a mentally ill woman in a letter, to find a formula for her movements: “Hands imitate playing the drum, the girl beats on the floor at regular intervals, as if she were beating time; at the same time, the head turns rapidly from left to right.

In short texts by Stepanov and Gorsky (he taught the system after Stepanov's premature death and before his transfer to Moscow at 1900) the whole range of ideas is given, the development of which Rudolf von Laban, the founder of Ausdruckstanz, the teacher of the largest choreographers and artists of this direction: Mary Wigman, Kurt Joss, Sigurd Leeder and others, will devote his search in the 1910-1920s. In his theory of the patterns of movements, there is a sense of dance as a higher art that cannot do without "dance writing": the preservation of choreographic monuments is an obligatory guarantee of its prosperity and development. Laban is close to the idea that the choreographer composes the dance score in the same way as the composer does, and the artists, like the musicians of the orchestra, learn it from the notation.

Laban is close to the idea that the choreographer composes the dance score in the same way as the composer does, and the artists, like the musicians of the orchestra, learn it from the notation.

Stepanov's notation did not become a mass hobby in the theater school. Bronislava Nijinskaya wrote: “Since 1900, when I entered the Imperial Theater School in Petrograd, I saw only two people who were interested and put a lot of effort into “grafting” and the desire to leave several ballets of M. I. Petipa recorded. These were N. G. Sergeev and A. I. Chekrygin (unfortunately, they did not consider Fokine’s ballets, not recognizing them as art, and possibly not having the means to record movements so unlike the previous conditional “pas”)” [Nijinskaya B.F. School and Theater of Movements. // Mnemosyne. Issue. 6. M., 2014. S. 385]. Moreover, Fyodor Lopukhov, an avant-garde artist and experimenter, was skeptical about notation from the school 1920-1930s. His sister Lydia, a famous ballerina who danced at Diaghilev's, laughingly called these lessons "kabbalism. "

"

Not just a practical tool, but one that will keep his creations in their sacred immutability. Tellingly, he did not leave a key to his notation, and only one is known from the complete records: in 19In 15, Nijinsky, interned by the authorities of Austria-Hungary, recorded The Afternoon of a Faun. When the manuscript was discovered, it took Ann Hutchinson Guest many years to decipher it.

Not just a practical tool, but one that will keep his creations in their sacred immutability. Tellingly, he did not leave a key to his notation, and only one is known from the complete records: in 19In 15, Nijinsky, interned by the authorities of Austria-Hungary, recorded The Afternoon of a Faun. When the manuscript was discovered, it took Ann Hutchinson Guest many years to decipher it. The views and hobbies of her brother had a tremendous influence on Bronislava Nijinska. When, in 1918-1919, simultaneously with Laban and independently of him, in her Kyiv studio, Nijinska developed a program for educating a new person (“School and Theater of Movements”), for “only a strong spiritually developed person can create”, Stepanov’s notation was an obligatory item of this program , a guide, a means of preserving dance, helping to navigate the laws of movement and consciously build new ones: “Movement must be used as a drawing, paint. All colors are beautiful, all lines are beautiful. What is needed to identify <. ..>, then it must be taken from the accumulated movements or newly seen", "there are no ugly movements, nothing in school should be denied, every movement must be" saved ", be able to master it and it will always be necessary for something whole."

..>, then it must be taken from the accumulated movements or newly seen", "there are no ugly movements, nothing in school should be denied, every movement must be" saved ", be able to master it and it will always be necessary for something whole."

In Nijinska's incomplete plans and statements, which have not taken shape in a coherent system, one of the constant motives, like in Laban, is the demand to remove dance from subordination to music, which is also impossible to achieve without choreographic notation: "If musical scores are being written now after many conversations with the choreographer and the artist, yet neither the choreographer nor the composer can be satisfied with each other. Another thing is if the choreographic score could be understood - the music would be written on an already finished creation, and then only for the first time the composer-choreographer would see himself. There would be no self-violence applied to already written music. You might think that then music in choreography would be reduced to some kind of working position? This is not true. With a ready-made choreographic score, it would be easier to criticize, the composer-musician could point out the weak, in his opinion, places in the choreographic score, and together with the composer-choreographer and the artist, they would come to the highest understanding of each other and therefore to the creation of integral works " .

With a ready-made choreographic score, it would be easier to criticize, the composer-musician could point out the weak, in his opinion, places in the choreographic score, and together with the composer-choreographer and the artist, they would come to the highest understanding of each other and therefore to the creation of integral works " .

The Laban system

Rudolf von Laban (1879–1958), the founder and theorist of "expressive" dance, believed that "the cathedral of the future is a moving temple built from dances that are prayers." A Hungarian by birth, Laban spent his childhood in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where his father was governor. Laban's biographers have no doubt that the idea of reuniting man with nature and the cosmos through dance was inspired by the dance rites of the Bosnian villages. Like his Russian contemporaries, Laban dreamed of a dance writing that would allow choreography, like other arts, to preserve and accumulate its treasures, movements of various types and forms. For him, this accumulation was imbued with a mystical meaning, for it contributed to the coming transformation of mankind. But also analytical, because it is impossible to teach a person (each person, and not a group of selected dancers) self-knowledge in dance, without knowing these patterns and without having the means to convey knowledge to the masses, who, having united in crowded "moving choirs", could aspire towards the achievement of the highest goal. With a systematic mindset, wide education and perseverance, Laban worked out his theory for many years.

For him, this accumulation was imbued with a mystical meaning, for it contributed to the coming transformation of mankind. But also analytical, because it is impossible to teach a person (each person, and not a group of selected dancers) self-knowledge in dance, without knowing these patterns and without having the means to convey knowledge to the masses, who, having united in crowded "moving choirs", could aspire towards the achievement of the highest goal. With a systematic mindset, wide education and perseverance, Laban worked out his theory for many years.

His revolutionary discovery, made during the First World War in Switzerland, in the Monte Verita colony of idealists, seekers and vegetarians, was the kinesphere: a three-dimensional figure of 20 faces and 12 spatial directions (icosahedron), formed by all possible positions of the elongated limbs of a person and with a single center. Within this icosahedron, Laban identifies a “sequence of movements” similar to musical scales: “This three-dimensional figure, more complex than that which reflects classical dance (an octahedron of eight faces and six spatial directions), allows us to embrace the entire integrity of the forms of human movement and in the best way imagine unstable spatial forms, such as diagonals, curvature and angles. By combining the study of space with the concept of dynamics, Rudolf von Laban also makes it possible to consider movement as an existential whole, and not as a linear unfolding. He breaks with the Cartesian tradition of separating gesture and expression. With the kinesphere, a different quality of movement arises, capable of reflecting new relations of power in space (fall, break, whirlwind) and emphasize the density of gestures, ”writes the French dance historian 1920-1930s Laure Guilbert [Laure Guilbert. Danser avec le IIIe Reich: les danseurs modernes sous le nazisme. 2000. P. 33]

Within this icosahedron, Laban identifies a “sequence of movements” similar to musical scales: “This three-dimensional figure, more complex than that which reflects classical dance (an octahedron of eight faces and six spatial directions), allows us to embrace the entire integrity of the forms of human movement and in the best way imagine unstable spatial forms, such as diagonals, curvature and angles. By combining the study of space with the concept of dynamics, Rudolf von Laban also makes it possible to consider movement as an existential whole, and not as a linear unfolding. He breaks with the Cartesian tradition of separating gesture and expression. With the kinesphere, a different quality of movement arises, capable of reflecting new relations of power in space (fall, break, whirlwind) and emphasize the density of gestures, ”writes the French dance historian 1920-1930s Laure Guilbert [Laure Guilbert. Danser avec le IIIe Reich: les danseurs modernes sous le nazisme. 2000. P. 33]

Modern dance was born from the desire of his founding father for harmony - in contrast with the sad circumstances of the world war and personal life: Laban at that time was completely alone, almost all of his students had left Monte Verita, so that the only one on whom he could test his theories was Mary Wigman, who recalled: “It was at this time that Laban began to work intensively on his dance notation. Since there was no one, I became for the most part an obedient and sometimes stubborn victim of his theoretical research. Every morning Laban knocked on her door, exclaiming: "The choreographer is coming." He laid out “papers covered with hastily sketched notes and signs, from crosses to thin human figures and again crosses, asterisks and curves”, and difficult joint work began. “The result of this hard struggle was the development of his movement scales (Schwungskalen). The first of these scales consisted of five different pendulum movements leading in a spiral from bottom to top. The organic combination of these spiraling directions and their natural three-dimensional properties led to perfect harmony. The various movements not only effortlessly came from one another, they seemed to be born one from the other. To indicate their dynamic value, he gave them names - pride, joy, anger, etc. <...> Each movement had to be done again and again before it was possible to master, analyze, transpose and transform into an adequate sign

Since there was no one, I became for the most part an obedient and sometimes stubborn victim of his theoretical research. Every morning Laban knocked on her door, exclaiming: "The choreographer is coming." He laid out “papers covered with hastily sketched notes and signs, from crosses to thin human figures and again crosses, asterisks and curves”, and difficult joint work began. “The result of this hard struggle was the development of his movement scales (Schwungskalen). The first of these scales consisted of five different pendulum movements leading in a spiral from bottom to top. The organic combination of these spiraling directions and their natural three-dimensional properties led to perfect harmony. The various movements not only effortlessly came from one another, they seemed to be born one from the other. To indicate their dynamic value, he gave them names - pride, joy, anger, etc. <...> Each movement had to be done again and again before it was possible to master, analyze, transpose and transform into an adequate sign  I have always had a clear sense of rhythm and dynamics, and my belief in "living through" and not just doing the movement was strong. So my personal approach to expressiveness and reaction was as much torture to Laban as his relentless attempts to achieve objectivity of movements were to me. Laban flew into a rage at Wigman's attempts to execute the "anger" move in his own way. He called Wigman a clown, a grotesque dancer, and reproached her for a complete lack of harmony, arguing that the movement of "anger" is anger itself, without any individual interpretations.

I have always had a clear sense of rhythm and dynamics, and my belief in "living through" and not just doing the movement was strong. So my personal approach to expressiveness and reaction was as much torture to Laban as his relentless attempts to achieve objectivity of movements were to me. Laban flew into a rage at Wigman's attempts to execute the "anger" move in his own way. He called Wigman a clown, a grotesque dancer, and reproached her for a complete lack of harmony, arguing that the movement of "anger" is anger itself, without any individual interpretations.

Laban's notation took shape in the system in the 1920s, after he moved to Germany. This was facilitated by the expansion of the cause and the strengthening of the practical need - moving choirs and dance schools of students and supporters of Laban were established all over Germany. Cinematography, based on the chapter "Guide to Recording" ("Schriftanleitungen") of Laban's Choreographie (1926), was officially presented in 1928 at the Second German Dance Congress in Essen and became the fruit of the collective efforts of Laban and his followers: Dusi Bereska, Sigurd Leeder, Kurt Joss and Albrecht Knuss. In addition to the term "kinetography", two others were also used: dance recording (Tanzschrift) and dance recording (Schrifttanz). "While the 'recording of the dance' is seen as a means of documenting and preserving the dance, the dance-recording should facilitate the process of creating a dance composition as such." According to Laban, “the ultimate artistic goal of cinematography is not the recording of dance, but the recording of dance,” Vera Maletich points out in the book on Laban’s notation “Body, Space, Expression” [Vera Maletic. Body, Space, Expression. 1987. P. 114]

In addition to the term "kinetography", two others were also used: dance recording (Tanzschrift) and dance recording (Schrifttanz). "While the 'recording of the dance' is seen as a means of documenting and preserving the dance, the dance-recording should facilitate the process of creating a dance composition as such." According to Laban, “the ultimate artistic goal of cinematography is not the recording of dance, but the recording of dance,” Vera Maletich points out in the book on Laban’s notation “Body, Space, Expression” [Vera Maletic. Body, Space, Expression. 1987. P. 114]

The ideas of cinematography, combined with the cult of mass festivities and spectacles that reigned in Germany in the 1920s-1930s, were realized on a scale that Stepanov and Gorsky could not dream of. They assumed that the choreographer would simply compose the score of the dance, and the artists would learn it according to their parts. Laban's notation was gradually turning from a way of self-knowledge and collective experience in dance into an instrument of political influence. In 1931, Martin Gleissner, a student of Laban, a supporter of the Social Democrats and the concept of “dance for all”, worked for eight months on the preparation of the choral game “Red Song”, presented in Berlin at the celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the German League of Worker Singers: “Thanks to the notation he did not need a single rehearsal, except for the general one, to stage the finale of the spectacle with a thousand participants, ”writes Laura Guilbert. Gleisner, who had Jewish roots, fled Germany with the rise of the Nazis, who initially encouraged moving choirs. At 19In 36, as part of the Olympic celebrations, Laban prepared a choral game for two thousand participants “From the spring wind and new joy” (“Vom Tauwind und der neuen Freude”), the purpose of which was to demonstrate the German spirit. The game was learned by the participants - some of whom were qualified dancers, some amateurs - from the scores. But while approving notation as a drill tool, the Nazi state, represented by the Minister of Propaganda, was wary of the intellectual nature of Laban's choreography (the state artist had to appeal to feelings).

In 1931, Martin Gleissner, a student of Laban, a supporter of the Social Democrats and the concept of “dance for all”, worked for eight months on the preparation of the choral game “Red Song”, presented in Berlin at the celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the German League of Worker Singers: “Thanks to the notation he did not need a single rehearsal, except for the general one, to stage the finale of the spectacle with a thousand participants, ”writes Laura Guilbert. Gleisner, who had Jewish roots, fled Germany with the rise of the Nazis, who initially encouraged moving choirs. At 19In 36, as part of the Olympic celebrations, Laban prepared a choral game for two thousand participants “From the spring wind and new joy” (“Vom Tauwind und der neuen Freude”), the purpose of which was to demonstrate the German spirit. The game was learned by the participants - some of whom were qualified dancers, some amateurs - from the scores. But while approving notation as a drill tool, the Nazi state, represented by the Minister of Propaganda, was wary of the intellectual nature of Laban's choreography (the state artist had to appeal to feelings). As a result, he was removed from the preparation of the Olympic Games, the choral game was banned, and a year later Laban was accused of containing "Eastern Masonic elements" in his theory and notation. He was forced to leave Germany [Lilian Karina, Marion Kant. Hitler's Dancers: German Modern Dance and the Third Reich. P. 57-58].

As a result, he was removed from the preparation of the Olympic Games, the choral game was banned, and a year later Laban was accused of containing "Eastern Masonic elements" in his theory and notation. He was forced to leave Germany [Lilian Karina, Marion Kant. Hitler's Dancers: German Modern Dance and the Third Reich. P. 57-58].

But at the same time, in 1941, in the educational program for mass dance teachers in Germany, compiled by Rosalia Chladek, Dorothea Günther, Jutta Klamt, Lotta Wernicke, Mary Wigman and Gustav Fischer-Klimt, the theory of National Socialism and folklore dance were side by side with the same notation and choral dance [Ibid. P. 215].

Since the 1940s, thanks to the energetic work of Ann Hutchinson Guest, student of Sigurd Leeder and founder of the Dance Notation Bureau in New York (1940), Laban's notation in the dance world came to be seen primarily as a way of preserving heritage. In 1955, she had an influential competitor - the musician Rudolf Benes and the dancer from Sadler's Wells Joan Benes introduced their notation system, which eventually became the official recording system of the Royal Ballet. Despite a number of practical properties that make recording in this system more compact and faster, it did not revolutionize the theory of dance, and the Beneš Institute of Choreology from its very foundation in 1962 was rather a purely English heritage preservation institution.

Despite a number of practical properties that make recording in this system more compact and faster, it did not revolutionize the theory of dance, and the Beneš Institute of Choreology from its very foundation in 1962 was rather a purely English heritage preservation institution.

From Laban to Forsyth

Laban's theory continued to enter the circle of constant reflections of those architects of modern dance who built their texts on spatial harmony. “Dance has a divine beginning and therefore it is impossible to try to explain it - it cannot be explained. But we can understand its essence if we devote our whole life to loving it and obeying the rules dictated by it,” stated Merce Cunningham. At 19In 1968, when no 3D animation existed, Cunningham thought about what it would be worth thinking about "electronic notation <...>, that is, three-dimensional. It could be contour diagrams or something like that, but so that they move in space so that you can see the details of the dance; and you can stop them or slow them down <. ..> see where each of them is in space, the form of movement, the rhythm” [T. Schiphorst. Making Dances with the Computer. // David Vaughan. Merce Cunningham: Creative Elements. P. 80].

..> see where each of them is in space, the form of movement, the rhythm” [T. Schiphorst. Making Dances with the Computer. // David Vaughan. Merce Cunningham: Creative Elements. P. 80].

However, with the invention of the computer, it was easier for him to design dances behind a monitor, in a visualized three-dimensional environment, directly, rather than building it out of two-dimensional notation. Since 1989, Cunningham has used the LifeForms 3D animation program to create dances, "a useful tool for the artist" but not a substitute for "curiosity and ingenuity."

A new turn in the development of choreography, caused by Laban's theories and notation, was made by Cunningham's antipode, the eternal experimenter and master of deconstruction William Forsyth. It happened at 1983, when Forsythe suffered a knee injury (the irony is that the same cause and forced rest helped in 1927 Kurt Joss to make a decisive contribution to the formation of cinematography). Forsyth rethought the ordered harmonious universe of Laban, turning its laws inside out. He made its principle not balance, but falling, not movement from one center, within one sphere, but movement from a multitude of spheres with their centers, competing and inconsistent with each other.

Forsyth rethought the ordered harmonious universe of Laban, turning its laws inside out. He made its principle not balance, but falling, not movement from one center, within one sphere, but movement from a multitude of spheres with their centers, competing and inconsistent with each other.

Forsyth introduced Laban's theory and notation into his laboratory for creating movements, the complexity of which is illustrated by interviews with Frankfurt Ballet dancer Dana Kaspersen. So, in "A LI E IN A©TION. Part I" (1992) Forsythe created these movements through iteration: “We took sheets of transparent paper, drew shapes on them, and cut geometric shapes, which we then folded back together to create a three-dimensional surface, under which another opened up. We superimposed an oblate projection of the Laban cube and computer-generated timelines organized into geometric shapes on top of a book page (the work of David Kern and Bill [Forsyth]). Then we xerified them. We then transferred simple geometric shapes onto these copies and repeated the process until we had a layered document. We used this document to start with to generate the motion. Then each of us created our own list of Laban notation symbols, time scales, letters, numbers from the document, and we used these lists as a map by which you can navigate in the stage space and the structure of the work as a whole. The words that were supposed to show through the cutouts on the document were translated into the 27-part alphabet of movements that Bill created (the alphabet refers to a series of small gestures based on words. In this case, H is transmitted through a gesture that reflects the thought of the word Hat - hat). The drawn lines connecting the words are visible on the scene board, and the 3D objects folded from paper are imagined as volumes or lines inscribed in the space of the scene, along which these phrases from the gestures we made are directed. For example, I take the gesture from my first word: a bent arm with a shoulder, moving from the highest to the lowest right point (according to the Laban model), and redirect this gesture into space, following a figure on the map, which I imagine projected into scene space ”[Dana Caspersen.

We used this document to start with to generate the motion. Then each of us created our own list of Laban notation symbols, time scales, letters, numbers from the document, and we used these lists as a map by which you can navigate in the stage space and the structure of the work as a whole. The words that were supposed to show through the cutouts on the document were translated into the 27-part alphabet of movements that Bill created (the alphabet refers to a series of small gestures based on words. In this case, H is transmitted through a gesture that reflects the thought of the word Hat - hat). The drawn lines connecting the words are visible on the scene board, and the 3D objects folded from paper are imagined as volumes or lines inscribed in the space of the scene, along which these phrases from the gestures we made are directed. For example, I take the gesture from my first word: a bent arm with a shoulder, moving from the highest to the lowest right point (according to the Laban model), and redirect this gesture into space, following a figure on the map, which I imagine projected into scene space ”[Dana Caspersen. It Starts From Any Point: Bill and the Frankfurt Ballet // Choreography and Dance 2000, Vol. 5, Part 3. P. 24–39. 2000].

It Starts From Any Point: Bill and the Frankfurt Ballet // Choreography and Dance 2000, Vol. 5, Part 3. P. 24–39. 2000].

Contemporary dance in many of its forms does not reject notation. For example, its ardent supporter is the Frenchman Angelin Preljocaj, who writes his ballets according to the Benes system. Three ballets (four scores) by William Forsythe, including "In the Middle Somewhat Elevated" and "Hermann Schmermann", are recorded in the same system. True, in 1990, an expert on Labanotation concluded that although the procedures performed with movements in Forsyth's ballets can generally be recorded, the sequence of movements in itself cannot be notated [Steven Spier. William Forsythe and the Practice of Choreography: It Starts From Any Point. P. 123]

However, there is a strange pattern in that most of the choreographers who were influenced by Laban's ideas and personality, even those who knew the notation, did not care too much about the preservation of their creations and did not consider conservation their mission. Of the 40-50 ballets by Kurt Joss, co-author of kinetography, only four remain, recorded by Ann Hutchinson Guest at Labanotation in 1973 and resumed in 1976 at Geoffrey Ballet. Merce Cunningham's will stated that his choreography would die with him. Pina Bausch did nothing during her lifetime to record her work, she cared little whether the West Wind survived or not (Wind von West, 1975), in 2014 reverently reconstructed and notated by John Giffin in Germany and America, also with the assistance of the Dance notation bureau. Trisha Brown is no longer going to show her ballets.

Of the 40-50 ballets by Kurt Joss, co-author of kinetography, only four remain, recorded by Ann Hutchinson Guest at Labanotation in 1973 and resumed in 1976 at Geoffrey Ballet. Merce Cunningham's will stated that his choreography would die with him. Pina Bausch did nothing during her lifetime to record her work, she cared little whether the West Wind survived or not (Wind von West, 1975), in 2014 reverently reconstructed and notated by John Giffin in Germany and America, also with the assistance of the Dance notation bureau. Trisha Brown is no longer going to show her ballets.

Disillusioned with choreography as a mystical message that can stop wars; in the fact that the masses can unite in dances with nature and space, and not to demonstrate strength to political opponents and intimidate internal enemies, the heirs of Laban and the choreographers inspired by him paradoxically approached his most important, as it seems, ideal - self-knowledge in a dance that cannot be documented .