How to critique a dance performance

| Guidelines for Viewing Dance and Writing Critiques for Dance Performances Chance favors a prepared mind! A mind is like a parachute; it works best when it’s open! The creative critic approaches each concert with open eyes and an open mind. Do not go with preconceived ideas or compare one performance against other performances. Each person will find a different aspect of the dance that is interesting for their own personal reasons and interests.

Guidelines for Viewing a Dance Performance:

Guidelines for Writing About a Dance Performance:

Mechanics:

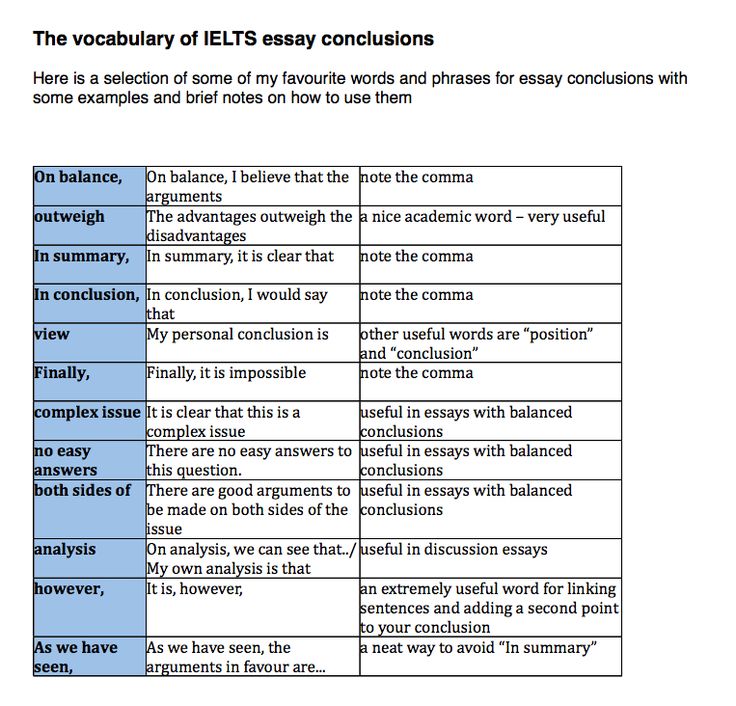

Dance Critique Pet Peeves: When writing about the subjects below: Refer to male dancers, men or danseurs (if classical ballet) Refer to female dancers, women or ballerinas (if classical ballet) Refer to a piece, work or dance Refer to movements Refer to live music Refer to recorded or pre-recorded music Refer to danced together or in unison Refer to the performance or the concert DO use both names ("Catherine Zeta-Jones danced well in Chicago" or "Ms. DO write in the third person DO NOT make general assumptions for the audience DO NOT include title page information on first page of critique (name, date, professor's name, class, performance) DO NOT switch tenses; DO NOT identify the performers in a list from the program notes.

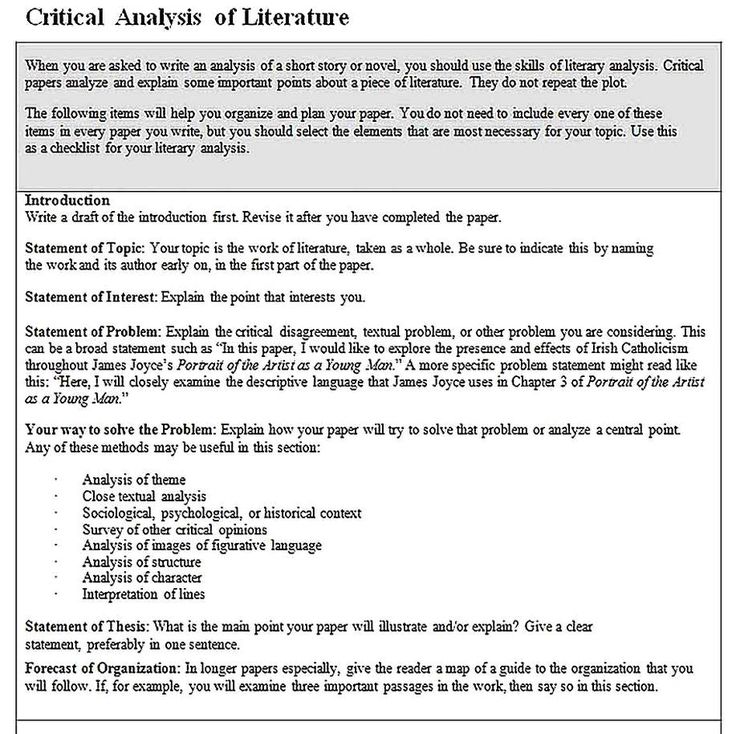

Example This is poor example of an opening paragraph because it does not grab the reader’s attention and only lists information readily found in the program. Also it does not provide the reader with any additional information or insights into the performance.

Dance Critique Checklist: _____ Title page including: student's name, due date of paper, class, concert critiqued, professor's name, pledge written in full. No title page information should be included on first page since you have a title page. _____ The ticket stub and/or verification from the performance must be attached to each critique. _____ Student's last name and page number should be included in upper right corner of each page. _____ Be sure to use one-inch margins on all sides in the text of your paper. Check your computer for margin settings. _____ Do not write in the first person. Write in the third person. _____ The first sentence of your critique sets the tone for the paper and should draw the reader in. _____ Critique has a centralized theme. _____ Critique has a conclusion. Other Disciplines | Writer's Web | Make a Tutoring Appointment | Modlin Center | Dept. of Theatre & Dance |

Responding to Dance - KET Education

Attending with a Purpose: Questions To Ask, Concepts To Know

It is always a good idea to have a purpose in mind when we are asked to respond to a dance performance, regardless of whether it is a formal concert, a performance of our peers, or a showing of a film or video. Below are some good questions to consider before, during, and after attending a dance performance. They are based on standards, key concepts, and key vocabulary that all Kentucky students are expected to understand and/or achieve (indicated below in italics).

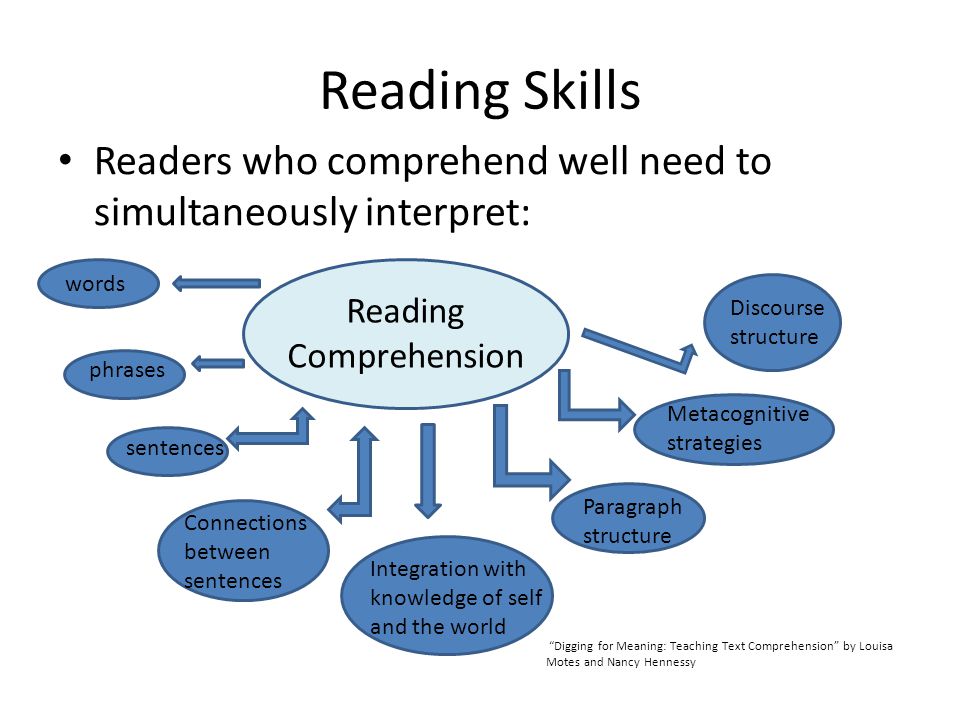

Being aware of your First Impressions allows you to think about your immediate response to the dance, both as you are experiencing it and immediately afterward. Since the Body is the instrument of expression in dance, it’s a good idea to understand how dancers prepare for a performance and to pay attention to the way they use their bodies in a performance. The material that choreographers use to communicate ideas, thoughts, and feelings is Movement (locomotor and non-locomotor). Finally, it is helpful to pay close attention to the Elements of Dance (Time, Space, Energy). If the dance is created for an artistic purpose, the choreographer uses the elements of dance, movement ideas, and the physical and expressive abilities of the dancers to create a dance that entertains, proves interesting, or moves (emotionally) the audience members in some way. Most dances, even social dances, have some Element of Production, such as costuming, setting, props, or lighting. Finally, dance occurs in a Social, Cultural, and Historical Context. It may be necessary to do some basic research regarding these contextual elements in order to fully understand and enjoy the performance.

Finally, dance occurs in a Social, Cultural, and Historical Context. It may be necessary to do some basic research regarding these contextual elements in order to fully understand and enjoy the performance.

Before You Go

Before you see the dance, review the questions below. Afterward, consider the same questions. Can you answer them? What more will you need to know in order to answer them well?

- Did the dance hold your interest? Can you say why or why not?

- Did you find it entertaining? If so, what parts did you particularly enjoy?

- Did the dance teach a lesson or have a moral?

- How did the dancers’ movements allow you to understand what the choreographer was trying to “say”?

- Did you have an emotional reaction to the dance? How did it make you feel?

- If the purpose of the dance was to tell a story (narrative), were you able to follow and understand it?

It will also be helpful for you to know some background information about the dance you are going to see before you actually see it. What research or reading might you need to do?

What research or reading might you need to do?

- Does the dance have a specific purpose?

- Is the purpose artistic? If so, what is the artistic form or genre?

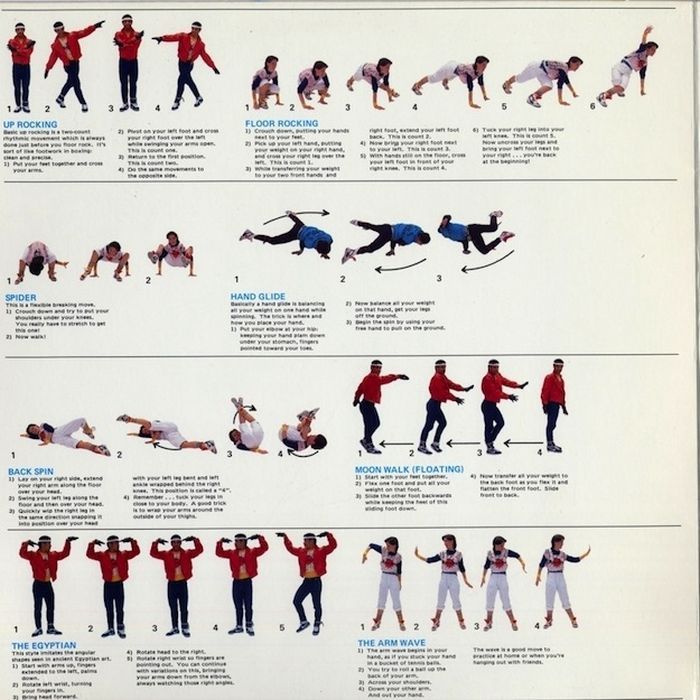

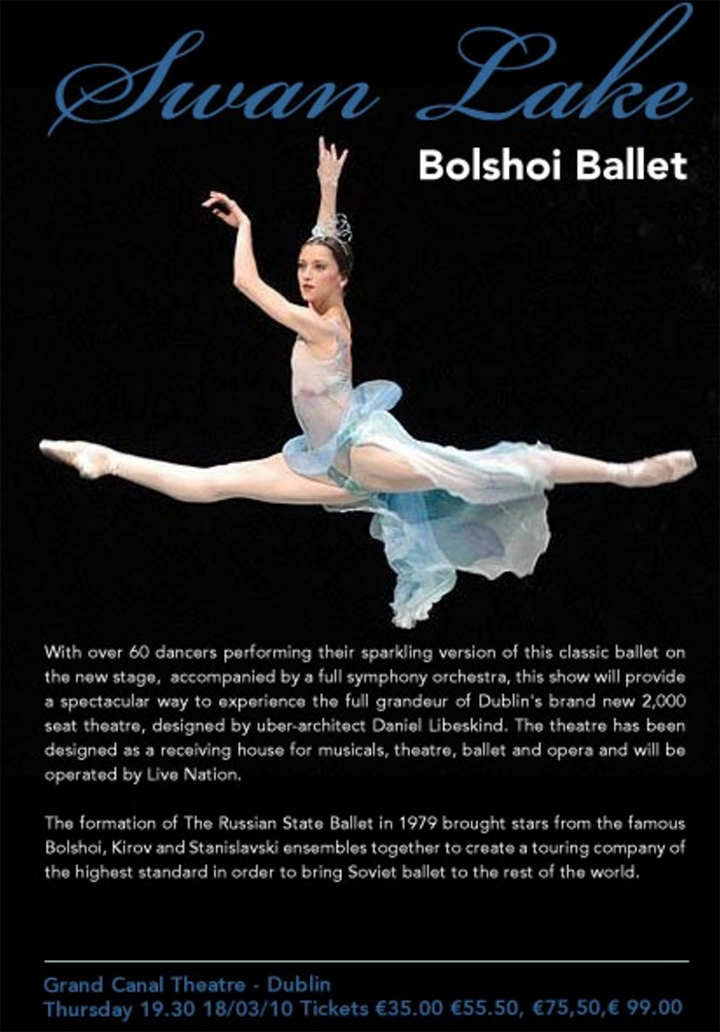

- Can you describe the characteristics of ballet, modern dance, jazz dance, or tap dance?

- How could you find information about these artistic forms of dance before you see the dance?

- Did someone choreograph this dance, or has this dance been passed down by tradition?

- Is this dance associated with a particular culture or ethnic group within a society?

- How can you find out more about the stylistic elements associated with the choreographer, culture, or ethnic group?

- Rather than artistic, is the purpose of the dance recreational or ceremonial?

- What does the purpose of the dance say about the culture or society it represents?

↑ Top

Viewing the Performance

In order to understand and enjoy the dance more fully, you may need to understand some key vocabulary and concepts before you see it. As you review the questions below, what further questions occur to you? Look for words and concepts in the Kentucky Dance Core Content that you need to understand better. Make sure you have at least reviewed a definition of these concepts before you see the dance.

As you review the questions below, what further questions occur to you? Look for words and concepts in the Kentucky Dance Core Content that you need to understand better. Make sure you have at least reviewed a definition of these concepts before you see the dance.

First Impressions:

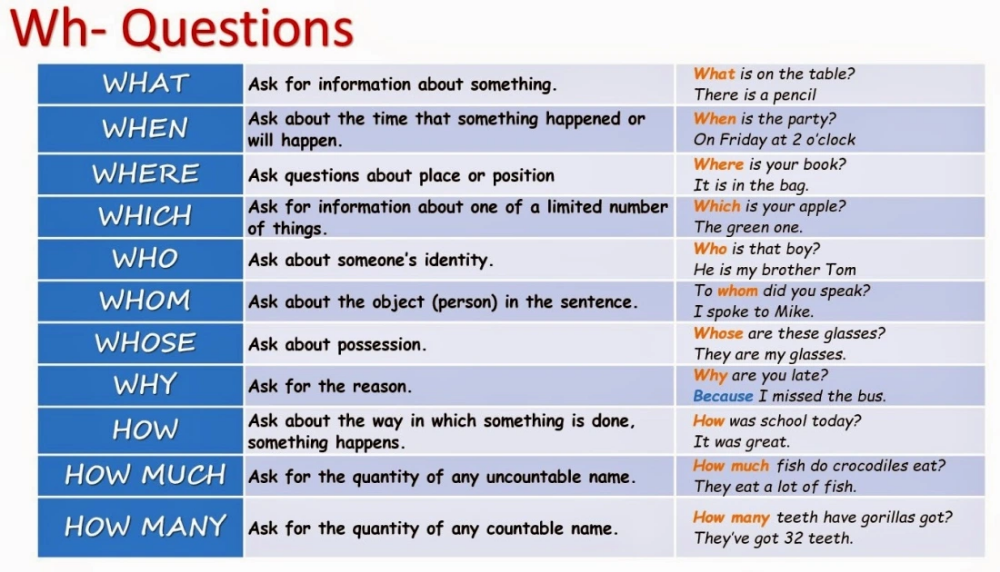

- How did the performance begin?

- What were some of your first impressions at the beginning of the dance?

- Did the dance have musical accompaniment? How did you like the music?

- Why do you think the choreographer chose this music?

- What made the strongest impression on you as the dance progressed?

- Can you describe this dance? Did it have a distinct beginning, middle, and end?

- Did you have a favorite dancer?

- What elements of the production (music, costumes, lighting, scenery) made the biggest impression on you?

The Dancers’ Bodies:

- How were the dancers’ bodies used in this dance?

- What different body parts did they use?

- Did they seem to move skillfully?

- Can you explain the roles that the skills of body alignment and dance technique play in a dance performance?

- Do you know when these skills are important and when they might not be?

- How can you use what you learned from the dance you have seen to understand these concepts more fully?

- What is it about the dancers’ training that allows them to use their bodies expressively?

- How did the musical accompaniment affect the way the dancers moved?

- What were the physical relationships between the dancers to each other during the dance? Did they ever move in unison?

- How are these movements different from everyday movements or sports movements?

- How do dancers train their bodies? What do they have to do to get ready for a performance?

- Can you compare the ways dancers warm up and prepare their bodies for dancing with the way that athletes warm up and prepare for competitions?

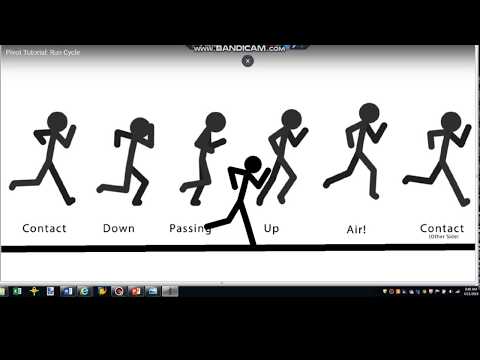

Movement (Locomotor and Non-Locomotor):

- Using the elements of dance, can you describe some of the movements in the dance, especially the ones that made a big impression on you?

- What did the dancers’ movements remind you of?

- How did the dancers combine locomotor and non-locomotor movements?

- What do you remember the most about the movements of the dancers?

- Did the movement seem to “go with” the music?

- How are the movements that are part of the dance similar to or different from everyday movements and sports movements?

Space:

- What shapes did the bodies of the dancers make?

- What floor patterns in space did the dancers make as they traveled through space?

- Did the dancers change levels at any time during the dance?

- Were there many “lifts”?

- In what sections of the dance was space emphasized the most?

- Were the shapes they made symmetrical or asymmetrical?

- How did the choreographer use aspects of the element of space to make the dance more interesting or to communicate the theme of the dance?

- Did the music seem to have any impact on the way the choreographer chose to use space?

Time:

- What aspects of the element of time were used?

- Was the dancing fast or slow? Were there changes in the tempo?

- What did you notice about the dancers’ rhythms?

- Were any of the movements accented?

- Was the tempo of the movement always the same as the tempo of the music?

- How did the choreographer use aspects of time to communicate his or her ideas or to make the dance more interesting?

Energy:

- How would you describe the energy of the dancers and the dance?

- Can you name all the different movement qualities (the way force and energy were used) you saw in the dance?

- Did the dance have a mood?

- How did the energy in the movement affect the mood of the dance?

- How was the energy of the movement similar to or different from the dynamics of the music?

- How did the dance make you feel?

Production Considerations:

- How effectively did the dance incorporate sets, lights, costumes, and sound, if at all?

- How did these elements complement the movement and the choreography?

- Can you describe at least three different ways that lighting was used to enhance the choreography?

- Were the costumes elaborate or simple?

- Why do you think the choreographer and costume designer made this choice?

- What skills do lighting designers and costume designers need to have?

- Did the choreography “fit” the dancing space (the stage)?

Historical, Social, and Cultural Context:

- How does dance in general contribute to society, both as an activity and as an art form?

- How does this dance reflect the personal history of the choreographer or the culture of a particular country or culture?

- How does the dance portray thematic ideas or societal issues?

- Does the musical accompaniment seem to reflect a particular culture, style, or historical period?

- Does it communicate or “comment on” any social or political beliefs?

- Put yourself in the role of the dancers for this performance.

How is their participation and preparation for the performance similar to or different from your own and other audience members’?

How is their participation and preparation for the performance similar to or different from your own and other audience members’? - Why did the choreographer create the dance?

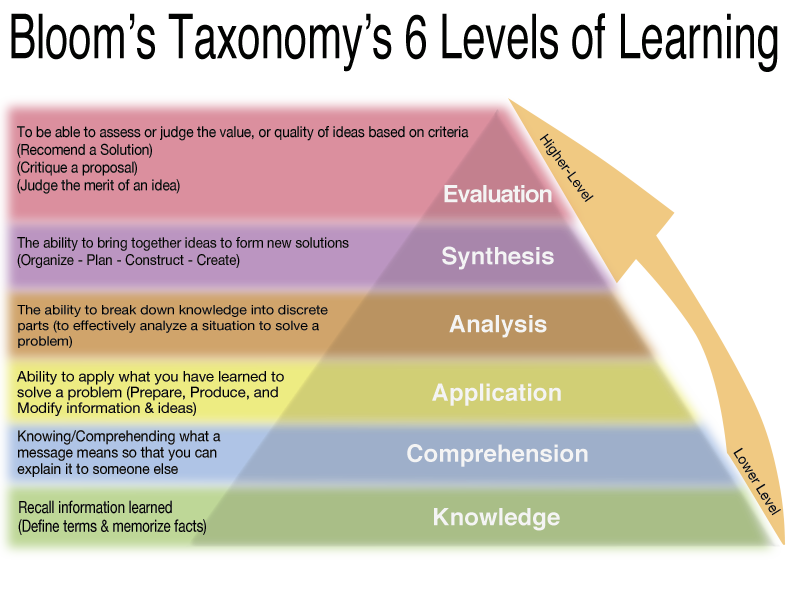

Analysis and Interpretation:

- Did the dance tell a story?

- Was the dance expressing feelings or an idea?

- What was the theme or the subject matter of the dance? How effectively was it carried through in the choreography?

- What choreographic form did the dance take?

- What was the meaning of the dance to you?

- If you observed more than one dance on the same “program,” how were the dances alike and different?

- Did the dance work for you (make sense to you) as a whole?

- What relevance does this dance have for you or others who might see it?

↑ Top

Critique

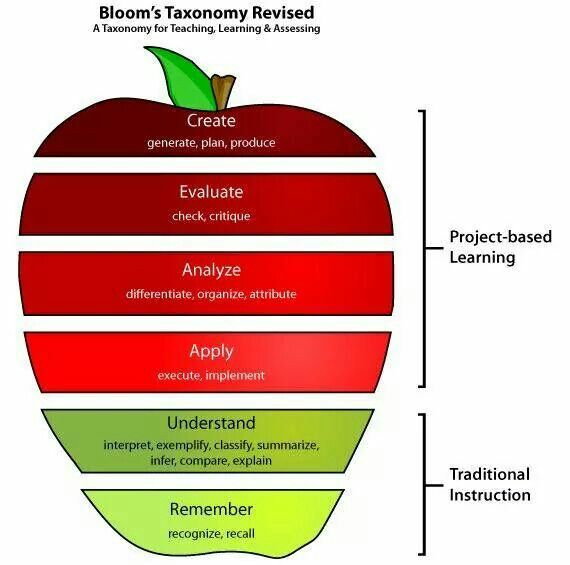

Now you are ready to make a judgment and communicate to an audience about the dance production you have seen. In responding to the questions above, you needed to describe movement and the elements of dance, analyze how they fit together, and explain or justify your response. Review your responses to the questions above and use your understanding of the concepts contained in these questions to help you determine your personal reaction to the performance. Now you are ready to write a critique!

Review your responses to the questions above and use your understanding of the concepts contained in these questions to help you determine your personal reaction to the performance. Now you are ready to write a critique!

Audience:

- Who are the intended readers of your critique?

- How will you interest them in what you have to say?

Purpose:

- Keep in mind your goal or purpose in writing for your audience.

- Are you trying to persuade your readers to see the performance (or not) or merely to persuade them to agree with your opinion after they have seen it?

Focus:

- What are the most important things to comment on when writing about your analysis of the performance? Remember to support your opinion with specific facts or examples from the performance.

Content:

- What was your overall impression of the performance?

- Was it an enjoyable or otherwise worthwhile experience? Why or why not?

- What entertained or impressed you the most?

- Were there weaknesses in the dancers’ performance, the choreography, or the production elements that you need to point out?

- On the other hand, what were the strongest aspects of the production?

- Would you recommend that others see it? Why or why not?

↑ Top

Quest Pistols Show about dance, criticism and zeitgeist -

Archive Not so long ago, the show group Quest Pistols Show released their new EP "Soundtrack", and exactly a week ago they presented a new clip "Wet" - "Wave" talked with the QPS members about what inspires them, what dance is for them and about many other things friend.

- - I'll probably start with a question that you've been asked a hundred times: how did you decide to switch to this format - Quest Pistols Show instead of Quest Pistols?

Nikita: It was a natural transformation. We didn't want to be guys in a popular band forever - pop idols don't last forever, there's nothing exciting about that. At some point, we and our producer Yura Bardash realized that nothing is impossible for Quest Pistols - and this is the whole catch, the very moment with which you want to calm down, but you can’t, because this is not a reward, but a reason to look for a new one. call. And we found it - it's the Quest Pistols Show, a dance performance that we put all our creative resources into.

- - So this is some kind of return to the roots, it turns out?

Nikita: Yes, a kind of synthesis between the past and the future. After all, we started as a ballet, and for all the amazing things that have happened to us over the past 8 years, we owe it to dance. Sooner or later it had to happen.

Sooner or later it had to happen.

- — Was it difficult to make the transition at all?

Nikita: There was no transition as such: we worked on the show for a year and a half and came up with it together, saturated with its ideas, and, as a result, at some point we just saw ourselves completely different from the outside. In addition, we found excellent artists: Washington, Vanya, Mariam. In general, when work on the Quest Pistols Show began, we were not going to expand the line-up of the group - we were just looking for bright non-format dancers. Everything worked out by itself. We saw the spirit of Quest Pistols in the guys and they are amazing artists, each of which surprises not only with their body movements, but also with their sense of music.

- - You are constantly rehearsing, working on yourself.

How difficult is it all?

How difficult is it all?

Vanya: Easy! Everything is fine, we hit it off as soon as we met. We immediately realized that these were our guys, our character. I think they probably thought so too. (laughs) At least I hope so. Well, right away - the guys dance very cool, Anton is still very cool in breaking. When we came as dancers, we did not feel such a moment that the guys were only singers, and we were kind of like backup dancers. No. Everything turned out differently: the guys taught us many things, sometimes they still suggest something - we get experience from them. We suggest something to them in terms of dancing technique there, that is, everything turned out great.

- — By the way, what is more important for you now: music, dance or their synthesis?

Nikita: It's just that dance, probably, cannot exist without music, and music cannot exist without dance. This is unequivocal - and it somehow happened. Well, like a puzzle, you know?

Mariam: The overall goal is to inspire people through music and dance, to let them feel the music of life and how they can find their own rhythm in it.

- — Now you have released a new EP: isn't it a problem that a person listens to songs, but can't correlate them with the dance, because he doesn't see this dance?

Nikita: I don't think that's a problem, because we actually support every audio work with a video. Any listener can watch, listen and see how this can basically happen to this music. Our new release "Soundtrack" is dance music written by people who know a lot about dance like no other. So no problem, you can just turn on the tracks and try to dance, everything will work out. Dance is a universal thing, it is a body language in which you can easily declare your love, or confess something completely immodest, this is the highest level of flirting. This is exactly what our new clip “Wet” is about.

- — It seemed to me that the lyrics became less ironic, more serious?

Vanya: How can I put it?

Nikita: They became provocative… Not in the sense of some vulgarity and outrageousness, on the contrary, an honest look at reality and the topics that occupy modern boys and girls: the search for sex, money and love.

- — But before that, it seems that you also had a lot of provocations?

Vanya: Yes, well, now is the era of dancing. Everything that happens in the world and with people can be danced, which is almost always much softer and more attractive than talking about it. Everyone is dancing. A man came up here recently, it was literally on the set, he came up and said, you know, I never liked dancing before. I just didn’t watch them, and I didn’t want to myself, but when I saw you, I fell in love with dancing. For me personally, it was very pleasant - that people are inspired by it. "Santa Lucia" inspired many people to go dancing or wear more colorful things, showing their character and some inner feelings. I think it was a win.

Mariam: What is very nice is that this song and video were liked not only by adults, but also by children. We have a lot of comments on Instagram, everyone sits and writes, for example, “my two-year-old daughter dances, she always asks to turn on this track. ” I have friends who have two children and I watch them dance in the same way. The day begins with Santa Lucia in the morning. You know, it seems to me that children cannot be deceived. And children very subtly feel quality and truth. And, probably, somewhere this track turned out to be so truthful and very sunny.

” I have friends who have two children and I watch them dance in the same way. The day begins with Santa Lucia in the morning. You know, it seems to me that children cannot be deceived. And children very subtly feel quality and truth. And, probably, somewhere this track turned out to be so truthful and very sunny.

- - Did you get any inspiration for the show itself? Did you get away from something?

Nikita: We have been working on the creation of the Quest Pistols Show for more than a year and a half - when it all started, we could not even imagine that the result would be like this. We just realized that we wanted to go beyond a pop group and do a show. As a result, we traveled half the world in search of dancers and inspiration - from Broadway to Cirque du Soleil.

Mariam: I was personally inspired by American shows. I went to America several times, watched various dance and musicals there, and they inspired me a lot. For example, "Chicago". Although we have absolutely nothing in common with it, but the people who dance there give such energy - I want to repeat something like that. What we are trying to do in our show.

I went to America several times, watched various dance and musicals there, and they inspired me a lot. For example, "Chicago". Although we have absolutely nothing in common with it, but the people who dance there give such energy - I want to repeat something like that. What we are trying to do in our show.

Nikita: It's probably West Side Story as well.

Vanya: Again, we do what we want. What inspires us, for the most part, has nothing to do with our show. That is, at some points we even surpassed those shows that we aspired to. I say this openly, because when you see this picture, the interaction of light, music, unreal video sequence and dance skills of all the people who take part - I think it all came together amazingly and gave such a result, and now the soundtrack is coming out.

- - It seemed to me that there is still an echo of the rave in all this ...

Nikita: Reyva? Of course. In the past few years, we have been greatly inspired by the club culture, because the dance came back just with its help. Therefore, in addition to the main Quest Pistols Show, we created another special club show - we just travel around the cities and arrange parties for people that they have never been to before. In Germany, for example, this project broke everyone.

Therefore, in addition to the main Quest Pistols Show, we created another special club show - we just travel around the cities and arrange parties for people that they have never been to before. In Germany, for example, this project broke everyone.

- — Speaking of change, do you even care that not all listeners are ready to accept radical change?

Nikita: Sometimes yes, but we often don't pay attention to comments, because after finishing a certain work we enter the next stage and deepen in it. We don't always have time to evaluate something...

Mariam: Most people like change, but paying attention to a minority... why? We have confidence in what we do.

- - That is, criticism is not honored?

Vanya: Cool. Criticize! We are shit - cool. We are cool? Cool! Something like this. Everyone has their own opinion, and that's the way it should be. And I think it's very cool.

- — In general, what interests me the most is: is it difficult for you to sing and dance at the same time?

Nikita: A little, yes. Although, to be honest, it is very difficult. Because you sing, you think about the words and you can't count the rhythm. It's hard to think of the words and read the rhythm at the same time. But, one way or another, we join with Anton and always support everyone in all manifestations of dance. When we can, we turn on. Initially, we do not forget our roots - we are dancers, we came out of dance, regardless of the fact that we have been as a group for 8 years. Often we look at the stage and often cross paths with other artists, nothing happens there. There, 2-3-4-5 people just go on stage and stand in rhythm, move, sing. Well, that's bad. That's why we came up with the Quest Pistols Show. Because just to sing about what people are interested in actually turned out to be very simple, but to make people just come and give you their head, heart and soul and say that they just didn’t see anything better.

Although, to be honest, it is very difficult. Because you sing, you think about the words and you can't count the rhythm. It's hard to think of the words and read the rhythm at the same time. But, one way or another, we join with Anton and always support everyone in all manifestations of dance. When we can, we turn on. Initially, we do not forget our roots - we are dancers, we came out of dance, regardless of the fact that we have been as a group for 8 years. Often we look at the stage and often cross paths with other artists, nothing happens there. There, 2-3-4-5 people just go on stage and stand in rhythm, move, sing. Well, that's bad. That's why we came up with the Quest Pistols Show. Because just to sing about what people are interested in actually turned out to be very simple, but to make people just come and give you their head, heart and soul and say that they just didn’t see anything better.

- — Does it matter to you whether the song takes off or not? Or is the show the main thing, and what happens to the song is already secondary?

Nikita: Mmmm… No, we don't release songs just like that. In fact, it's normal when a song is successful. We came to the conclusion that each of our work is like some kind of theatrical performance. This is both visual and audio work, and everything that brings these works to the masses: both information and some kind of entourage.

In fact, it's normal when a song is successful. We came to the conclusion that each of our work is like some kind of theatrical performance. This is both visual and audio work, and everything that brings these works to the masses: both information and some kind of entourage.

- - You were talking about the era of dance. What else do you think is in the spirit of the times right now?

Nikita: A revolution of colors, mood, harmony. The whole world is music that has its own harmony, and our music has its own.

Washington: To be alive. When you listen to "Happy" by Farrell, you want to go to work, to study. This is what gives you exactly this feeling - I'm alive. And it is in "Santa Lucia".

Vanya: We just did it because it was cool, because we wanted to. We put our dancing skills there, which certainly gave such an effect. Even by and large, not the song itself, but the mood that we gave people, this is our main task - to give people a mood. And we wanted to tell people that there is "Santa Lucia". This is how she can be.

And we wanted to tell people that there is "Santa Lucia". This is how she can be.

- - Let's sum it up with an equally simple question: what is dance for you?

Mariam: This is our way of communicating with the world.

Vanya: Dance is generally unique. Do you know how many girls I met through dancing? Only due to this. I want to say that this is the first way to reveal yourself. You imagine that you came to some kind of party, and you do it cool. You're actually drawing attention to yourself. Everything happens like this. I would like to wish people to dance as much as possible.

Interview

- Artem Makarsky

Plow everything, and we wave our hands

Plow everything, and we wave our hands | Colta.ruSeptember 12, 2018ArtModern dance

11031

Ethical substantiation of the project "Soviet Gesture"Dancing onlineSpirit and flesh treacherously slip awayDance after pornographyExcited curatorDancers of our days Plow everything, and we wave our hands

On August 20, the exhibition "Here and Now", a review of Russian contemporary art of recent years, ended in the Manege. The exposition caused conflicting responses from the art community: from praise to negativity in the informal field of telegram criticism.

The exposition caused conflicting responses from the art community: from praise to negativity in the informal field of telegram criticism.

Some said that the exhibition shows Russian art "as it is today", demonstrates the original solution of space, openness and friendliness towards the audience [1] . They attacked along several lines: the lack of a thoughtful curatorial decision and the speculative use of performative elements. Thus, the resonant channel "Zakuliska" reminded readers that "Here and Now" was created hastily for the September elections and was sponsored by the Moscow City Hall. As a result, the channel reported, it turned out to be a hodgepodge of "sovrisk artists familiar to the curator - who has something lying around in the garage" [2] .

Another line of attack went through the event elements of the exposition, which, in addition to objects, installations and video works, included performances. The exhibition was criticized for being zombie-performative: the speculative use of living bodies, which, by the mere fact of their presence, should legitimize controversial or banal ideas [3] .

Works are often done as if in a vacuum and disappear without a trace, and the absence of their archive and comprehension does not create opportunities for continuity and development.

Although the exhibition case deserves a separate analysis, in this text we use it as an occasion to talk about another phenomenon of the Moscow art scene. In parallel with the exposition program, a blackbox was assembled on the ground floor of the Manezh and five works of Russian contemporary dance were shown there (curated by Katya Ganyushina). Although the program remained outside the field of interest of apologists and critics of the exhibition, it can be considered the first big show of new Russian dance in a museum institution. And the shown works, in our opinion, quite logically selected, became evidence of the existence of an actual dance scene in Moscow [4] .

Guide to imposture

Imposture Lab© Ekaterina Pomelova

Only thirty people can sign up for the Imposture Lab. You need to come in comfortable clothes, and at the entrance instead of a ticket they give you a bottle of water. Then, for three hours, participants undergo an empowerment training under the guidance of three artists: Vik Laschenova, Vera Shelkina and Dmitry Volkov.

You need to come in comfortable clothes, and at the entrance instead of a ticket they give you a bottle of water. Then, for three hours, participants undergo an empowerment training under the guidance of three artists: Vik Laschenova, Vera Shelkina and Dmitry Volkov.

The training exercises revolve around issues of professional identity, combining vigorous street workouts (physical activity), imaginative tasks, pair sessions and group discussions. Artists immediately declare that they themselves are impostors in dance and art and, in general, eternal professional migrants. Vic worked in consulting, then worked in photography and video, until he realized himself as a modern choreographer. Vera is a translator and part-time dance artist. Dima came from world IT but "not sure if the impostor is in art". Further events in the style of uplifting and soothing commercial training allegedly help participants "to realize and accept the impostors in themselves." Looks like a real therapy group - if not for the disturbing absurdity of some of the exercises [5] .

At the first workout, Vik suggests spreading your arms to the sides and feeling the energy balls in your palms. Then, to the accompaniment of a cheerful track, everyone learns to throw these balls, hitting exactly the dream target or destroying the enemy .

Fifty years of ban on modern forms of movement, the primacy of ballet (our everything) and the habit of being proud of athletic training add points to the marginalization of the already unrecognized modern dance.

Next, the participants stand in two lines and share their experience of imposture with each other. In a pair exercise, one is trying to "take his place", while the other is looking for strategies to move him. Then everyone learns to take off using concentration, dream visualization and proper weight distribution.

Another workout: you choose a “celebrity” for yourself (the Pope, Trump, the President of Croatia or, for example, an Internet cat), practice imitating his / her gestures and go out with them to the center of the hall, where you meet other characters. At this moment, the laboratory turns into an exhibition of embodied GIFs, which, meeting in space, give rise to kinesthetic communication gaps. Trump almost kills Queen Elizabeth in triumphant machismo, the robot enters into a strange post-anthropocentric symbiosis with a cat.

At this moment, the laboratory turns into an exhibition of embodied GIFs, which, meeting in space, give rise to kinesthetic communication gaps. Trump almost kills Queen Elizabeth in triumphant machismo, the robot enters into a strange post-anthropocentric symbiosis with a cat.

Another workout - apparently from leadership training, when participants practice the skill of "leading." In a group set to the same energetic music, everyone memorizes a fitness dance, the main pose of which is copied from the Motherland Calls monument. Everything ends with the learning of a bunch a la tai chi under the guidance of Vera Shchelkina, who combines the exercises developed during the training into a single “healing” complex.

"Laboratory of imposture"© Ekaterina Pomelova

Nominally, the laboratory deals with universal imposture (when we are forced to constantly change professions, wander through creative services) and seems to help to work with psychological discomfort, cultivating self-confidence, positivity and self-empowerment. However, it is distinguished from real trainings by the alienating elements, which together evoke anxiety and misunderstanding of the purpose and format of what is happening (whether it is really a training, or a performance without spectators, which still implies a view from the outside). One of these elements is aggression, wired into friendly exercises of "belief in yourself." You either get closer, revealing to each other the experience of imposture, then you learn to throw balls at the enemy or displace the partner from their place. The theme of the competition of all with all is not presented openly, but looms like an alarming sign hidden in harmless tasks.

However, it is distinguished from real trainings by the alienating elements, which together evoke anxiety and misunderstanding of the purpose and format of what is happening (whether it is really a training, or a performance without spectators, which still implies a view from the outside). One of these elements is aggression, wired into friendly exercises of "belief in yourself." You either get closer, revealing to each other the experience of imposture, then you learn to throw balls at the enemy or displace the partner from their place. The theme of the competition of all with all is not presented openly, but looms like an alarming sign hidden in harmless tasks.

Another disturbing sign is the forms of bodily practices molded from perverted dance and somatic exercises. Artists take body-spiritual training practices and introduce iconographic elements from pop culture or Soviet visual history into them. In the process of preparation, the guys collected athletic “images of strength”, whether it was the poses of comic book heroes or heroes of Soviet monuments, and then introduced them into their exercises. If the participant notices this (sees himself from the outside), the practice loses its apparent neutrality and betrays ideological content. And although outwardly the scenario looks like a training in flexibility and opportunism (“everyone is impostors, everything will work out, you have to believe in yourself”), dozens of barely noticeable oddities leave those who came in anxious doubt about the attitude of the artists themselves to professionalism, precarity and ways to adapt to it.

If the participant notices this (sees himself from the outside), the practice loses its apparent neutrality and betrays ideological content. And although outwardly the scenario looks like a training in flexibility and opportunism (“everyone is impostors, everything will work out, you have to believe in yourself”), dozens of barely noticeable oddities leave those who came in anxious doubt about the attitude of the artists themselves to professionalism, precarity and ways to adapt to it.

Please don't dance

Oneh Zucker's "It's okay, basically." Show at TsIM© Ekaterina Kraeva

"Imposture Laboratory" is the perfect prologue for the entire dance program. It shows what contemporary dance can be like today: formally, meaningfully and at the level of communication with the audience. The work has nothing to do with popular notions of dance as “an art that expresses feelings and thoughts through movement” and shakes the visual stereotype about contemporary dance : Barefoot people in loose clothing dance expressively. The other performances of the program also do not fit into the common school definition. Strictly speaking, there is not much dance in them at all [6] , but almost all works assume that the viewer not only looks, but also passes them through the body.

The other performances of the program also do not fit into the common school definition. Strictly speaking, there is not much dance in them at all [6] , but almost all works assume that the viewer not only looks, but also passes them through the body.

For example, the work “In principle, everything is fine” by the One Zucker group is not a performance, but a dance installation. For eight hours, attendees co-exist with blackbox performers, lying in bed with them, chatting, drinking tea or watching solo performances. By dissecting different layers of their everyday experience — from automatic movement patterns to everyday speech — artists are trying to create a different, detached everyday life, a kind of “normal environment” for artistic experience, almost indistinguishable from ordinary life. However, the blackbox's formal frame allows the visitor to develop a special vigilance for this everyday normality.

"In principle, everything is fine" by One Zucker. Show at TsIM© Yuliya Zakharova

Show at TsIM© Yuliya Zakharova

Since there is no continuous tradition of contemporary dance in Russia, it can be assumed that both the "Laboratory", and the installation "One Zucker", and the performances shown there "Urban Planning" by Tatiana Chizhikova, "We Were Here" dance The Po V.S. Dances and Professional companies by Tatyana Gordeeva and Ekaterina Bondarenko inherit the lines of the American-European dance avant-garde, which has always followed the path of artistic reflection and formal lawlessness.

Its history begins in the USA in the 1960s and is connected with the convergence with the visual arts, as well as the crisis of modern dance, which emphasized movement as a means of expression, authorship, spectacle and emotionality. The period from the 1960s to the 1980s was a time of renewal, radicalization and deep self-reflection of dance art, leaving a layer of theoretical and aesthetic developments that dance artists still refer to [7] . The continuation of this line can be seen in the European dance 1990s - 2000s and the "non-dance" direction, in which choreographers abandon traditional work with movement in favor of other theatrical and artistic media. The same line is characterized by the critical position of choreographers regarding their art and the conditions of its existence. Since then, everything new in dance has been less about producing spectacular form (in a conservative sense) than about finding the boundaries of dance and movement, exploring ways of bodily communication, exploring the potential of dance to produce communities, emphasizing the social message that the body carries, the study of dance as an action, a way of thinking and producing affects.

The same line is characterized by the critical position of choreographers regarding their art and the conditions of its existence. Since then, everything new in dance has been less about producing spectacular form (in a conservative sense) than about finding the boundaries of dance and movement, exploring ways of bodily communication, exploring the potential of dance to produce communities, emphasizing the social message that the body carries, the study of dance as an action, a way of thinking and producing affects.

In this sense, the concept of "modern dance" today does not indicate one form or another of the work, and even the presence of moving bodies in the work, but rather informs that for the artist it is important to work with the body, action, movement, time, but how he understands and presents it is not known in advance. The performances of the program demonstrate this formal irreducibility and understanding of dance as a field of reflection and artistic experiment. And collected in one program, they present themselves as a special phenomenon in the world of Russian dance - or, one might say, a new dance scene.

Beyond professionalism

Performance "Professional". Show at TsIM© Ekaterina Kraeva

Returning to the "Laboratory", it is important to say that the theme of (un)professionalism is one of the central ones for contemporary Russian dance. It combines a painful relationship for dancers with classical technical dance and their eternal precariousness, which is also tied to the physical capabilities of the body. Although Western modern dance won the right to not necessarily be technical back in the middle of the last century, in Russia this knowledge does not seem to be widely assimilated, and there is a historical justification for this [8] . Fifty years of ban on modern forms of movement, the primacy of ballet (our everything) and the habit of being proud of sports and dance training, as well as exposing it as a national treasure, add points to the marginalization of the already unrecognized modern dance. People from related fields often come here, without professional training, and the sphere itself can hardly be called professional: there is no clear understanding of how to build an education, it is not clear how to make a career and earn money. And although it is possible to trace the mentioned works to the Western dance avant-garde, it is important to take into account the specific Russian context in which they are created.

And although it is possible to trace the mentioned works to the Western dance avant-garde, it is important to take into account the specific Russian context in which they are created.

Tanya, a former dancer of the Kremlin ballet, could not explain to her relatives what she was doing for a long time after leaving for modern dance.

This is a context of general low awareness of dance history, fueled by a lack of education in contemporary dance theory. Although the new dance is often closer to performance and even installation than to classical theatre, it is not usually included in the educational programs of art schools. If we talk about the professional training of dancers, in it physical development is rarely accompanied by art criticism and theoretical studies. Therefore, Russian dance is characterized by being out of time and a certain forgetfulness. Often the works are done as if in a vacuum and disappear without a trace, and the absence of their archive and comprehension does not create opportunities for continuity and development.

In this sense, I would like to think that the selected works are trying to settle down in the history of art, relate themselves to modern philosophical thought, build artistic strategies and value positions [9] .

Performance "Professional". Show at TsIM© Ekaterina Kraeva

Perhaps that is why the new dance in Russia is especially characterized by auto-reflection. The study and pronunciation of the conditions of one's existence is a psychological necessity. This is largely based on "Professional" - a performance by Tatyana Gordeeva and Ekaterina Bondarenko, who completed the dance program at the Manezh. It combines a conversation with the audience about work with reflection on the professional qualities of a dance performer. Tanya, a former artist of the Kremlin Ballet, after leaving for modern dance, for a long time could not explain to her relatives what she was doing: in her current works, only criticism of the ballet remained. Katya is a playwright without a dance background who has recently become a performer. In the performance, she half-jokingly understands how the audience should perceive her nedonets. At the end, they measure the level of boredom in the audience by voting, combining therapy and metacommentary on the work in an ironic gesture [10] .

Katya is a playwright without a dance background who has recently become a performer. In the performance, she half-jokingly understands how the audience should perceive her nedonets. At the end, they measure the level of boredom in the audience by voting, combining therapy and metacommentary on the work in an ironic gesture [10] .

Fortunately, everything is not limited to self-digging, and choreographers use their position to think and talk about common things - and let the audience experience their work directly through the body.

[1] The concept of the exhibition, the conditions for its creation and the list of works are available at this link.

[2] The text of the post is at this link.

[3] The text of the post is at this link. Here, performances that were periodically repeated throughout the exposition were criticized: for example, Elena Kovylina's performance "Cultural Carrots", originally shown at the Danilovsky market.

[4] The dance program includes five works created in 2017-2018 and previously shown at other venues in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Minsk and Kyiv: Imposture Laboratory by Vik Laschenov, Vera Shelkina and Dmitry Volkov , “In principle, everything is fine” by the “One Zucker” group, “Urban planning” by Tatyana Chizhikova, “We were here” by the companies “Po V.S.Tantsy” and “Professional” by Tatyana Gordeeva and Ekaterina Bondarenko. The authors of these works belong to different generations of Russian contemporary dance, but all of them are more like modern dance artists than choreographers in the classical sense of the word (people who come up with movements and assemble them into bundles). The program assembled in this way is interesting to contrast with the contemporary dance festival held on the same dates in St. Petersburg Open Look , which focuses on showing technical spectacular dance without much pretense of criticism or relevance.

[5] "Laboratory" can also be seen in line with the recent trend to present (pseudo)trainings, yoga classes, parties, raves, somatic practices and therapy sessions as new forms of dance and performance representation.

[6] Although the "Laboratory" does not thematize stereotypes around dance art, the very presentation of such "non-dance" works in the contemporary dance program strongly states that this field is much wider than specific techniques or styles. Since the Russian audience often expects technical, expressive movement from contemporary dance, the selection of such works is a conscious curatorial decision. We also note that the refusal of choreographers to work with dance in the usual sense goes back to the French intellectual dance of the late 1990s - a trend called "non-dance". There is a well-known incident when a spectator, who came to the performance of “non-dance” by Jerome Bel, sued the festival that showed it because the dance work did not contain expressive movements and jumps to the music. "Non-dance" and other branches of "conceptual dance" actively developed in Europe until about the mid-2000s and are analyzed in the books of Andre Lepeka, Ramsey Bert, Bojana Cveich. Subsequently, the "conceptual dance" was criticized, which is stated, for example, in an essay by the Swedish choreographer Martin Sponberg "Post-dance, an advocacy" .

Subsequently, the "conceptual dance" was criticized, which is stated, for example, in an essay by the Swedish choreographer Martin Sponberg "Post-dance, an advocacy" .

[7] Sally Baines' cult book Terpsichore in Sneakers: Postmodern Dance, first published in America in 1979, tells about this in detail. In 2018, the publishing house of the Garage Museum published a book in Russian.

[8] On the Russian dance scene, one can feel the opposition of modern experimental dance to ballet, modern or technical contemporary , and sometimes hostility of representatives of different directions towards each other. Although new forms of dance were actively developing in the USSR, thanks in part to the popularity of the Duncan school, from 19In the 1930s, their development was stopped. While western dance has gone through a consistent development from modern to postmodern, non-dance and post-dance, in Russia a new dance is revived only in the late 1980s on unfavorable ground. Ballet, sports, gymnastics are held in high esteem, while reflexive experimental (not) dance is either not perceived at all by the professional community, or is perceived in a negative way - as the work of half-educated people. Perhaps due to the pressure of conservative views, experimental dance is increasingly striving for galleries, museums and venues of the Center for Contemporary Art.

Ballet, sports, gymnastics are held in high esteem, while reflexive experimental (not) dance is either not perceived at all by the professional community, or is perceived in a negative way - as the work of half-educated people. Perhaps due to the pressure of conservative views, experimental dance is increasingly striving for galleries, museums and venues of the Center for Contemporary Art.

[9] In addition to the works and groups mentioned above, this also includes works by the Isadorino Gore cooperative, Alexander Andriyashkin, Anya Kravchenko. Although these are very different artists, they are united by the desire to see their work in a broad context of artistic and socio-political processes.

[10] Olga Tarakanova wrote about this performance in detail in an article on The Village .

Did you like the material? Help the site!

Test

Santa Claus Kiss

Forbidden Christmas hit and other holiday songs in a special test and playlist COLTA. RU

RU

news

March 11, 2022

14:52 COLTA.RU blocked in Russia

March 3, 2022

17:48 "Rain" temporarily stops broadcasting

17:18 The Union of Journalists of Karelia complained about Roskomnadzor to the Prosecutor General's Office

16:32 Sergey Abashin left the Association of Ethnologists and Anthropologists of Russia

15:36 The Prosecutor General's Office called participation in anti-war rallies extremism

All news

New in Art sectionMost read

Two chalks on blue paper

54421

Birch grove barcode and artificial birds chirping

42375

Pension claim

13166

Leaky contrast

13005

Dark Rays

12458

Against illustration

14039

“The feeling of Brezhnev’s quarantine returned along with covid”

13648

March of Microbes

15548

Imagine technologically

13726

Dust free

19721

“Pictures with a touch of civic sorrow are needed”

21069

Developed by light

18465

Today online

Around the horizontalGrigory Yudin about the past and future of the protest.

Big talk

Big talk What becomes the basis for mass protest? What are its starting conditions? What prejudices and mistakes threaten him? Does protest need decentralization? And how to evaluate its success?

December 1, 20225199

Around the horizontalGert Lovink: “Web 3 is really a new beast”

Will Web 3.0 be able to handle the freeing of the global web from large platforms? What is gained, what is lost, and, in general, is this reform so revolutionary? Mitya Lebedev spoke with a well-known media theorist

November 29, 20221886

Around the horizontal"How to keep the complexity of relationships and support each other when you can't hug each other?"

Horizontal communities in wartime—between ruptures, isolation, loss of soil, and gain of soil. A conversation between two representatives of cultural initiatives - Elena Ishchenko, who left Russia, and an activist who remained in Russia, who speaks on condition of anonymity

A conversation between two representatives of cultural initiatives - Elena Ishchenko, who left Russia, and an activist who remained in Russia, who speaks on condition of anonymity

November 4, 202211459

Around the horizontalHow to make money for self-organized communities

A guide to old (and working) and brand new features

October 25, 202211497

Around horizontal"Community is a superpower"

How new expats come together to help themselves and others

September 29, 202211328

Around horizontalJust below radar

Introduction to self-organization.

Remember that there is no right answer since art is abstract and everyone responds to art differently.

Remember that there is no right answer since art is abstract and everyone responds to art differently.

” Vienna-Lusthaus (revisited); Reviewed by George Jackson: Dance Magazine, May 2003: 79.

” Vienna-Lusthaus (revisited); Reviewed by George Jackson: Dance Magazine, May 2003: 79.  When speaking about any element of design, you must include the designers' names.

When speaking about any element of design, you must include the designers' names.  Check your computer for margin settings.

Check your computer for margin settings.  Zeta-Jones danced well in Chicago.")

Zeta-Jones danced well in Chicago.")

Performing lead roles were, Léonide Massine and Tamara Toumonova. Also dancing were Tatiana Riaboushinska, Alexandra Danilova, Yurek Lazowski, Vera Zorina, Marc Platoff, Vera Volkova, Igor Youchkevitch and George Zoritch. Hector Berlioz did a great job composing both the music and the libretto for this performance.

Performing lead roles were, Léonide Massine and Tamara Toumonova. Also dancing were Tatiana Riaboushinska, Alexandra Danilova, Yurek Lazowski, Vera Zorina, Marc Platoff, Vera Volkova, Igor Youchkevitch and George Zoritch. Hector Berlioz did a great job composing both the music and the libretto for this performance.