How to do mime dance

What Is a Mime? | Wonderopolis

ARTS & CULTURE — Entertainment

Have You Ever Wondered...

- What is a mime?

- When was mime invented?

- What are the two main types of mime?

Tags:

See All Tags

- acrobatic,

- acting,

- American,

- art,

- Bip,

- character,

- Charlie Chaplin,

- communicate,

- culture,

- dancing,

- eclectic,

- emotion,

- entertainment,

- European,

- expression,

- facial,

- feeling,

- France,

- funny,

- gesture,

- Greek,

- Jean Gaspard Batiste Deburau,

- language,

- laughter,

- make-up,

- Marcel Marceau,

- mime,

- non-verbal,

- pantomime,

- Paul J.

Curtis,

- performance,

- Pierrot,

- play-writing,

- Roman,

- silent,

- white

Have you ever been wandering around the streets of a city and happened upon a street performer wearing interesting clothes, lots of white make-up, but not making a sound? If so, chances are you've met a mime!

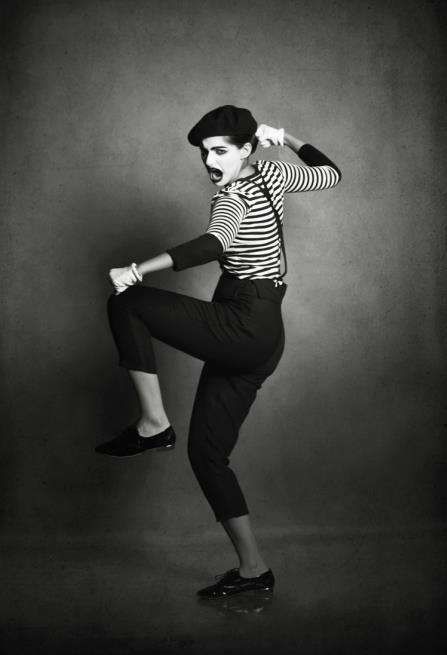

Mime is a form of silent art that involves acting or communicating using only movements, gestures, and facial expressions. A person performing mime is also called a mime.

Non-verbal communication dates all the way back to the first human beings. Before there was spoken language, gestures and facial expressions were used to communicate. As spoken language developed, these gestures and facial expressions were retained as a form of simple entertainment.

As spoken language developed, these gestures and facial expressions were retained as a form of simple entertainment.

Many people associate mime with French culture. However, mime is an ancient art that dates back to the early Greeks and Romans. It was in France, though, where mime flourished. It became so popular that mime schools were established throughout France, and a great tradition of French mimes soon followed.

Mime was brought to Paris in 1811 by Jean Gaspard Batiste Deburau, who was part of a touring acrobatic family. Deburau stayed in France and developed mime into the expressive modern version that still exists today. Deburau was famous for his foolish, naïve, lovesick character named Pierrot.

One of the most famous French mimes was Marcel Marceau. His character, Bip, wore a short coat and a top hat with a flower, Like Pierrot, Bip was mostly down on his luck. Marceau's work was also influenced by early silent film stars, such as Charlie Chaplin.

Modern mime can be divided into two main types: abstract and literal. Abstract mime usually does not feature a main character and has no plot. Instead, it focuses on provoking thought about a particular subject by expressing certain feelings or emotions.

Abstract mime usually does not feature a main character and has no plot. Instead, it focuses on provoking thought about a particular subject by expressing certain feelings or emotions.

Literal mime tells a story with a plot and characters. Often these stories are funny situations intended to elicit laughter from the audience. Some modern versions of mime also combine these two types into one interesting performance.

In 1952, Paul J. Curtis developed the art form now known as American mime. Different from its traditional, European counterpart, American mime combines acting, play-writing, and pantomime dancing. Modern mimes in America can often be seen blending many eclectic styles as they experiment and push the boundaries of the art form.

Wonder What's Next?

Tomorrow’s Wonder of the Day may have you shouting, “Show me the money!”

Try It Out

We hope you have no words for how WONDERful today's Wonder of the Day was! Learn even more when you explore the following activities with a friend or family member:

- Want to know more about one of the world's most famous mimes? Jump online to read all about the life of Marcel Marceau.

Share what you learn with a friend or family member. Can you find any videos online of Marcel Marceau?

Share what you learn with a friend or family member. Can you find any videos online of Marcel Marceau? - Want to see a mime in action? Check out Silent Storytelling: The Art of the Mime online. Do you think you could be a mime? Why or why not? What is the most compelling part of a mime's performance to you?

- Are you ready to give it a try? Yes! Even you can be a mime if you give it a try. To start, write a short, simple story that you would like to tell to another person. When you're finished, read through your story and think about how you could tell that story without saying a single word. Of course, you may want to change a few parts after you've given it some thought. When you're ready, become a mime and tell your story without words! Let your actions speak. If you're up for a challenge, you can even wear make-up and dress like a mime!

Did you get it?

Test your knowledgeWonder Words

- sound

- art

- form

- luck

- exist

- acting

- mime

- gesture

- facial

- silent

- performer

- lovesick

- expression

- flourish

- naïve

- abstract

- literal

- eclectic

Take the Wonder Word Challenge

Rate this wonder

Share this wonder

×GET YOUR WONDER DAILY

Subscribe to Wonderopolis and receive the Wonder of the Day® via email or SMS

Join the Buzz

Don’t miss our special deals, gifts and promotions. Be the first to know!

Be the first to know!

Share with the World

Tell everybody about Wonderopolis and its wonders.

Share Wonderopolis

Wonderopolis Widget

Interested in sharing Wonderopolis® every day? Want to add a little wonder to your website? Help spread the wonder of families learning together.

Add widget

You Got It!

Continue

Not Quite!

Try Again

Once upon a mime • Articles

There’s a moment in the cult TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer when Buffy pummels her fists into the air to show a friend how she beat up a particularly annoying demon. Buffy reckons the demon got its just deserts, but her friend retorts: ‘Nobody deserves mime, Buffy.’

Ouch! Mime does indeed have a bad rep. Just mention the word and stock images spring unbidden to mind: figures in white facepaint and black gloves, archly opening invisible doors; the withering heights of Kate Bush’s early am-dram phase; and of course, those perilous moments in classical ballet where the dancing stops so that someone can explain something using mannered, incomprehensible gesticulations. Yes, it’s easy to make fun of mime – and people do. The all-male Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, for example, milk mime for all it’s worth, and get laughs every time.

Yes, it’s easy to make fun of mime – and people do. The all-male Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, for example, milk mime for all it’s worth, and get laughs every time.

Yet mime is also a serious matter. The mute, stylised embodiment of utterance, action and emotion is a cornerstone of many performance traditions, from ballet to Japanese noh theatre, from classical Indian dance-drama to the uncanny aesthetics of puppetry, the visual storytelling of silent cinema, and the illusionist virtuosity of some hip-hop styles. Mime forms a vital seam in a whole range of performance techniques. To find out what mime looks like from the inside, rather than from sniggering distance, I spoke to a range of ballet practitioners: a dancer, a choreographer and two teachers.

‘I feel you could touch the words even though you can’t hear them’ — Gary Avis

First was Gary Avis, a principal character artist with the Royal Ballet whose on-Zoom persona was just as I had imagined: eager, unstarry, and incapable of talking without his hands leaping to life and waving about, as musical as a conductor’s. Avis has won the UK’s National Dance Award for best male classical performance not once, but twice (in 2012 and 2020) – a prize that generally goes to a principal dancer. On both occasions, he accepted the award with thanks for its recognition of character dancers – rarely the stars of the ballet world, yet integral to the artform.

Avis has won the UK’s National Dance Award for best male classical performance not once, but twice (in 2012 and 2020) – a prize that generally goes to a principal dancer. On both occasions, he accepted the award with thanks for its recognition of character dancers – rarely the stars of the ballet world, yet integral to the artform.

‘I was interested in storytelling from a very young age,’ he tells me. ‘At first I wanted to be in musicals, and went to musical theatre college before the Royal Ballet School.’ There, he was inspired in particular by his mime and character teachers. ‘I saw how you could be a dancer and also tell imaginative, intricate stories through mime, and through a kind of body language.’

That idea of mime – to tell stories without words – became a focus in the eighteenth century, as ballet moved from court to theatre. In the nineteenth century, it is found both in the general idea of expressive gesture, and a more stylised code with specific meanings: love, death, marry, dance. This codified form fell out of use in newer choreography, but remains embedded in the classics – though many modern productions trim or adapt these mime sequences.

This codified form fell out of use in newer choreography, but remains embedded in the classics – though many modern productions trim or adapt these mime sequences.

Expressive gesture and theatrical dancing, though, remain strong creative currents in ballet dancing and choreography. Indeed, as Avis talks, it becomes clear that he doesn’t make hard and fast distinctions between acting, mime and expression, or even dancing: underlying them all is a notion of body language. ‘It isn’t mime on one side or dance on the other. There’s a real crossover, now more than ever. Choreographers use mime in different ways to tell stories. Traditional ballet mime has more set gestures, but what’s interesting now is how mime morphs into more of a …’ – he searches for the word – ‘a physicality.’

Physicality, it seems to me, is the well that Avis taps – an inner impulse that finds its outlet in hugely different forms of expression: in the caperings of Dr Coppélius, the melodrama of Von Rothbart, MacMillan’s hot-headed Tybalt, or stolid Richard Dalloway in Wayne McGregor’s Woolf Works. How does he prepare for these roles?

How does he prepare for these roles?

‘I take the characters home with me,’ he says. ‘I’ve been caught many times pulling facial expressions on the train because I’m going through a piece of rep in my head!’ To understand the role, he says, ‘you need to know who your character is: where you’ve come from, why you’re in this situation, where you’re about to go.’ During performance too, he has words, dialogues, cues – a whole script that runs silently in his head but is ‘pronounced’, as he puts it, by his body.

Avis also watches people around him – on the train, in the street, on screen – and takes note of their mannerisms, interactions, ways of walking. Though he doesn’t understand sign language, he marvels at how people in the deaf community use it to converse. ‘It’s so expressive and so coded at the same time! Even if you don’t understand it, you sense the emotion, and the push and pull through the physical space of the dialogue. I try to get a sense of that energy when I’m performing. I like to feel that you could almost touch the words even though you can’t hear them.’

I like to feel that you could almost touch the words even though you can’t hear them.’

Choreographer Cathy Marston has, too, always been fascinated by storytelling and people-watching, and indeed has cast Avis in her ballets. But like most contemporary choreographers, she doesn’t use formal ballet mime, a gestural code which only the initiated understand. By way of illustration, she shows me the mime for ‘dance’ from Giselle – hands spiralling in a little vortex above her head, as if indicating a well-mannered cloud of gnats – and raises a quizzical eyebrow. Point taken.

Though she doesn’t use coded mime, Marston does use what you could call mimesis, or imitation – gesture, action and interaction – to build character and plot through movement. ‘A number of my ballets feature a cup of tea. It began with Ghosts in 2004, where I wanted that awkward feeling of people in the same room, but isolated – when you just hear swallowing and clinking and it’s all a bit louder than it should be. ’ She used gestures from tea making and drinking not just to signal the story but to build character, mood and metaphor: emotions brewing, desires stirring. Like many modern choreographers, Marston tries to fuse choreography with acting and symbolism, without showing the seams.

’ She used gestures from tea making and drinking not just to signal the story but to build character, mood and metaphor: emotions brewing, desires stirring. Like many modern choreographers, Marston tries to fuse choreography with acting and symbolism, without showing the seams.

Why have dancers with mime training, then? Not because they can perform ballet mime, but because of what lies behind that schooling. ‘Companies with a tradition of character dancing bring a level of acting into the choreography that is harder to get with more contemporary companies,’ she says. With Dangerous Liaisons (Royal Danish Ballet, 2017), for example, she recalls Sorella Englund – ‘nearly 80, fabulous, and with enormous respect through the whole company’ – as an emblem of how an acting style suffuses the whole company. San Francisco Ballet, with its far less theatrical repertoire, has a different culture. ‘When I first worked there I found it quite hard to draw the acting out. Whereas with the Royal or Royal Danish, the dancers can act big. It’s much easier to bring that down to the right level than to try to pull the acting out falsely.’

It’s much easier to bring that down to the right level than to try to pull the acting out falsely.’

Ballet teacher Justine Berry is, without a doubt, the most enthusiastic champion of the character dancer I have met. Programme manager for the RAD Professional Teacher Diploma, and guest teacher for numerous major schools and companies, she began as a dancer with London City Ballet, and took on character roles from an exceptionally young age – Giselle’s mother, for example, when she was just 20. ‘I was very different to a lot of young dancers,’ she exclaims, happily. ‘I always found the mime just fascinating!’ When pushed, she thinks her favourite mime character would be the witch Madge in La Sylphide. ‘It’s so easy to go, she’s just this grumpy old person, but I would look at her and think: there’s so much in your life that we don’t know about.’ Good or bad, old or young, Berry always wants to know why a character is as they are. She is interested in the motivation behind the mime, a question that is foundational in theatre training; in ballet, much less so. For Berry, though, an understanding of motivation and backstory marks the difference between character and caricature. ‘If you just ham up the character, they don’t resonate with anyone. They become laughable.’

‘It’s so easy to go, she’s just this grumpy old person, but I would look at her and think: there’s so much in your life that we don’t know about.’ Good or bad, old or young, Berry always wants to know why a character is as they are. She is interested in the motivation behind the mime, a question that is foundational in theatre training; in ballet, much less so. For Berry, though, an understanding of motivation and backstory marks the difference between character and caricature. ‘If you just ham up the character, they don’t resonate with anyone. They become laughable.’

Berry insists on teaching mime to music. ‘Music is always central. When you’re teaching mime, it’s important to attach it to a musical phrase. In the rep, everything happens on the dynamic of the music – that’s how choreography and acting and setting and story all fit together.’

Berry also notices how mime can develop dancers as performers. ‘Mime roles need stage presence. It takes enormous confidence to carry the story and inhabit that character. ’ Marston had mentioned this too: mime, and acting in general, can be intimidating – especially for younger dancers, who sometimes find their comfort zone within physical technique. Overcome those inhibitions, and you can hold a stage just by being on it.

’ Marston had mentioned this too: mime, and acting in general, can be intimidating – especially for younger dancers, who sometimes find their comfort zone within physical technique. Overcome those inhibitions, and you can hold a stage just by being on it.

Gestures are forms of recognition and validation. They humanise us.

That’s all well and good for people going into the profession – but what about the far greater number who take ballet classes but never make a vocation of it? Does mime serve any useful purpose for them? I put the question to Imogen Knight, a Trustee of the RAD and director of the Colours of Dance school in Cambridge, a largely non-vocational school that caters to lovers of dance rather than aspiring professionals.

Perhaps it’s that range of encounters that enables her to spell out what mime is. ‘In classical ballet,’ she says, ‘mime is a specialist discipline of its own, with its own code. Then you have these amazing mime artists in circus or theatre arts, with their own evolved disciplines that have nothing to do with ballet. And third, you have general storytelling, which is more like acting through movement. Underneath them all is the idea of non-verbal communication: how do I tell the story without words?’

And third, you have general storytelling, which is more like acting through movement. Underneath them all is the idea of non-verbal communication: how do I tell the story without words?’

Knight finds the coded ballet mime of most interest to adult students, who may already be balletgoers themselves. The RAD’s Discovering Repertoire programme is valuable here: mime becomes part of comprehending the art. For young children, Knight finds that storytelling comes into its own. ‘Older children perhaps are better at understanding abstracted moods that come from music or a way of moving, whereas at the junior levels you often get a stronger response if they have a storyline.’

Yet mime does play a part even at that young age. Take the reverence – a mimed ‘thank you’ that marks the beginning and end of every class. For Knight, this is no mere affectation, but a point of commonality that brings children together, both for each other and as a group. ‘It’s really simple,’ she says, ‘but it’s amazing how many parents burst into tears the first time they see it. ’

’

There is something profound here, about being individuals and about belonging. In her RADiate classes – the RAD programme for children whose specific social, emotional or physical circumstances can make verbal communication challenging – Knight draws on that depth. Gestures become forms of recognition and validation. ‘Effectively you’re saying: how you communicate is good. Not different, not right: good. That is normalising for every child in the room.’ Communication through movement is not simply a code or message delivery system, but a form of sociality that humanises us, to ourselves and to each other. And everybody deserves that.

Pantomime as the basis of effective dance

Pantomime as the basis of effective dance

The role of pantomime in choreographic art is enormous. It comes from the Greek word pantomimos, which meant an actor acting on stage using only one body language. Currently, there are two meanings of the word "pantomime". The first implies the art of expressing thoughts and feelings through gestures and facial expressions. The second definition characterizes pantomime as a theatrical performance that has musical accompaniment. The artistic image in it is created without a single word, only with the use of facial expressions, movements and gestures.

The first implies the art of expressing thoughts and feelings through gestures and facial expressions. The second definition characterizes pantomime as a theatrical performance that has musical accompaniment. The artistic image in it is created without a single word, only with the use of facial expressions, movements and gestures.

Pantomime performances originated in antiquity and were a great success. In the 18th century, Jean-Georges Nover made pantomime the main element of the ballet, which was used in synthesis with a dance or a plot scene. In addition, pantomime began to be actively used in folk performances, such as Italian comedies dell'arte, medieval mysteries, harlequinades and fair performances.

Later, elements of the harlequinade were used in silent and sound films, as well as in the circus. Russian dancers readily accepted the theoretical views of the great ballet reformer Jean-Georges Noverre and developed them practically. With all his activities, Noverre asserted the primacy of pantomime in a ballet performance.

With all his activities, Noverre asserted the primacy of pantomime in a ballet performance.

The striving for the pantomimization of dance, for the psychological and plastic development of characters, for the creation of a meaningful and naturally developing silent drama also characterizes the activities of Carl Didlot, who adopted the ideas of Noverre. Contemporaries regarded Didelot's ballets as "excellent dramas, full of fiction, truth, movement, expressed in the most eloquent pantomime."

The 20th century was the heyday of pantomime. Composers created pantomimes as separate works or parts of a large musical stage composition. The dance, which used the language of gestures and facial expressions, became a kind of correlation between recitative and aria in opera art. The dance carries an expressive beginning, and pantomime is responsible for the manifestation of the pictorial essence. With the help of movements, a generalized attitude is expressed, and with the power of gestures and facial expressions, a specific one.

The dance is based on the repetition of plastic elements to a certain rhythm. And pantomime, both in rhythmic and plastic terms, is quite heterogeneous in its composition. The movements used in dance are continuous and unified, while in pantomime they are disjointed and separate. Pantomime is related to drama theater on the one hand, and to dance on the other.

In the XVIII-XIX centuries, the language of facial expressions and gestures was used to express the action, and with the help of dance the state was transmitted. Pantomimes were separated from dance elements, as they often used conditional gestures. Both Nover and his follower in this direction Fokine wanted to destroy the invisible boundary between pantomime and dance.

In contemporary ballet, pantomime has acquired an enormous dramatic significance. But, despite this, it did not become the main means of expression in it. Dance still occupies a leading position here. The language of gestures and facial expressions plays an additional and concretizing role here. Throughout the 19th century, the pantomime traditions in ballet faded away, then revived again. Interest in pantomime arose at the beginning of the new twentieth century and is associated with the impressionistic ballets of M. Fokine and A. Gorsky. The birth of dramatic pantomime in Russia as an independent form of theatrical art, distinct from ballet, dates back to the same time.

The language of gestures and facial expressions plays an additional and concretizing role here. Throughout the 19th century, the pantomime traditions in ballet faded away, then revived again. Interest in pantomime arose at the beginning of the new twentieth century and is associated with the impressionistic ballets of M. Fokine and A. Gorsky. The birth of dramatic pantomime in Russia as an independent form of theatrical art, distinct from ballet, dates back to the same time.

The dance of Isadora Duncan was a phenomenon that caused an increased interest in pantomime, in the plastic expressiveness of the actor, in the culture of movement.

The first performance in Russia took place in 1905. Her principles of plastic expression created a sensation and served as the basis for the emergence of numerous studios that set themselves dramatic and pantomimic tasks. Her "Barefoot" dances professed the cult of the body, where it was assumed that the naked body, barely covered with transparent fabrics, returns humanity to its childhood, to the free manifestation of the spirit through the body.

Modern Pantomime is a form of stage spectacle, where with the help of body movements, gestures and facial expressions, the body of the actor's position reveals the character of the character, the content and idea of silent drama. The muteness of pantomime makes it related to the art of dancing. The close connection of pantomime with dance is also manifested in the fact that dance teaches pantomime the accuracy of form, while pantomime teaches dance dramatic expressiveness. An actor of pantomime may not dance, but he must necessarily have the ability to reincarnate, to characterize. To create an image not only by mimic means, but also by plastic ones.

A specific feature of pantomime is the dramatic beginning, which is the basis of the action, where the main thing is the expression of movements and the body of positions that express the actions, characters, feelings, intentions and relationships of the depicted persons. Pantomime can be both a big performance and a small suffering miniature - a silent short story, a story, a poem, a fairy tale, a farce, a fable, a caricature.

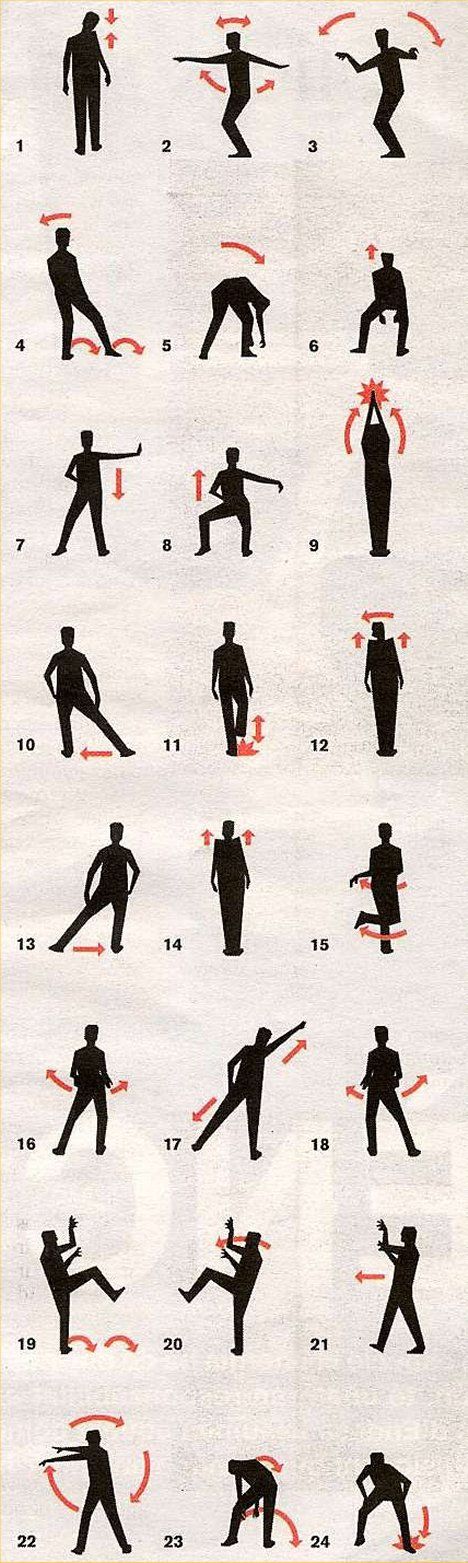

Gesture in the broadest interpretation - the movement of the arm, leg, torso, smile, facial gesture - is an expressive means of pantomime. Every pantomimic expression is based on ordinary natural movement.

The nature of a movement, gesture, action changes depending on the causes that cause it, on the character, age, emotional state of the character. These factors influence movement, tempo and rhythm, which gives each plastic expression its own individual coloring, its own meaning. The plastic characterization of the character is made up of successive actions and gestures that have their own logic. The logic of life behavior dictates to the actor the logic of stage behavior; the life gesture underlies the stage gesture, which must be easily deciphered and understood. Only a meaningful gesture is appropriate in realistic pantomime.

The art of pantomime is closely connected with dance, circus, drama, cinema, so it is difficult to consider it in isolation from these arts. Depending on which art pantomime is most closely combined with, we distinguish three types of pantomime:

Depending on which art pantomime is most closely combined with, we distinguish three types of pantomime:

-

Dance pantomime, its characteristic feature is a conditional, rhythmically and spatially organized gesture, facial expressions, movement.

-

Acrobatic pantomime, gesture brought to the maximum conventionality, easily turning into acrobatics.

-

Dramatic or natural pantomime, which is likened to a person's natural life behavior.

Often these three types of pantomime are found in a mixed form. In classical ballet, for example, we see, along with dance pantomime and acrobatic elements, a pronounced tendency towards a natural gesture of life.

The language of gestures and movements is understandable to everyone. This explains the irreplaceable qualities of pantomime - its democracy and internationality, its accessibility and understandability for all countries and peoples of the world. In addition, pantomime is designed to develop the imagination and expressiveness of choreographers. These qualities help the dancer to vividly demonstrate his actions and intentions, and therefore help to reveal the author's intention. Now I propose to play a game that will show how developed your imagination is.

In addition, pantomime is designed to develop the imagination and expressiveness of choreographers. These qualities help the dancer to vividly demonstrate his actions and intentions, and therefore help to reveal the author's intention. Now I propose to play a game that will show how developed your imagination is.

"Improvisation in dance like pantomime" | Project:

MBOU "Secondary School 37", Cheboksary,

Teacher of additional education (choreographer) - Dolgova K.A.

Project name: "Improvisation in dance, like pantomime"

Brief summary of the project: 2019 has been declared the Year of Theater in Russia. And the theater, just like dance, is in constant motion, acquiring new features. Increasingly, choreographers are resorting to the form of theater - dance, which allows you to reveal the full potential of the dancer and show the whole storyline to the viewer, keeping up with the times.

Theatrical art includes the art of pantomime. Pantomime is talking about a lot without saying a word. Pantomime is an excellent acting school. She develops humor, emotionality, teaches masterly control of her body. And, of course, any person tends to get carried away with the elements of movement, especially if it happens in dance and on stage.

Pantomime is an excellent acting school. She develops humor, emotionality, teaches masterly control of her body. And, of course, any person tends to get carried away with the elements of movement, especially if it happens in dance and on stage.

Recently, improvisation has become more and more common in dance. Improvisation is the spontaneous realization of a work without the use of new movements. But in contemporary art, there is a distrust of improvisation among dance masters, it is acceptable only for social dance and the search for new movements, but cannot be a stage genre.

In order to improvise more often on stage, you can use pantomime. A mime, a pantomime actor, must develop the ability to find the most expressive movements of his body for a particular plot in the dance.

Purpose of the project: development of dance and acting potential in children of middle school age at choreography lessons through improvisation, like pantomime.

Project objectives:

- To study the theoretical and practical foundations of pantomime and the characteristics of improvisation;

- To form the ability to improvise in dance and teach basic acting skills in dance art;

- Conduct and analyze choreography classes with elements of pantomime;

- Provide emotional relief for students, cultivate a culture of emotions on stage.

Target group of the project: Middle school students.

Project implementation period: 5 years

On the basis of MBOU "Secondary School No. 37 with in-depth study of individual subjects" in Cheboksary, on September 1, 2018, a dance group "School of Dance" was created.

"School of Dance" is an author's project and designed for students in grades 5-9 of a general education school aged 10-15, taking into account their age capabilities and abilities.

A distinctive feature of the project is the complexity of the approach to the implementation of educational tasks, which primarily imply the developmental focus of the project.

The following areas are identified in the project:

- development of children's physical abilities;

- acquisition of dance-rhythmic skills;

- work on dance repertoire;

- musical and theoretical training;

- theoretical and analytical work;

- concert and performing activities.

An integral part of the learning process in choreography is improvisation, where the student shows all the acting skills in pantomime. With the help of it, he develops attention, fantasy, rhythm, plasticity, emotions.

On the basis of this technique, a number was staged for the dance group "Olimp" from the "School of Dance" "On the streets of Paris".

This dance group, which consists of 15 students in grades 5-6, is engaged in only three quarters and the first results have appeared.

It is worth noting that not all students have been involved in choreography up to this point. For some, this was the first experience of performing in front of a large audience, for some it was overcoming self-doubt, for some it was communication, and someone came to improve their physical data and each student found his place in the team .

January 21, 2019of the year at the Open Cup of the Chuvash Republic in all dance directions "Dances 21" t / c "Olympus" with the dance "On the streets of Paris" took 1st place in the School League in the Formation Juniors nomination.