How to dance persian

A Glimps into Persian Dance Technique

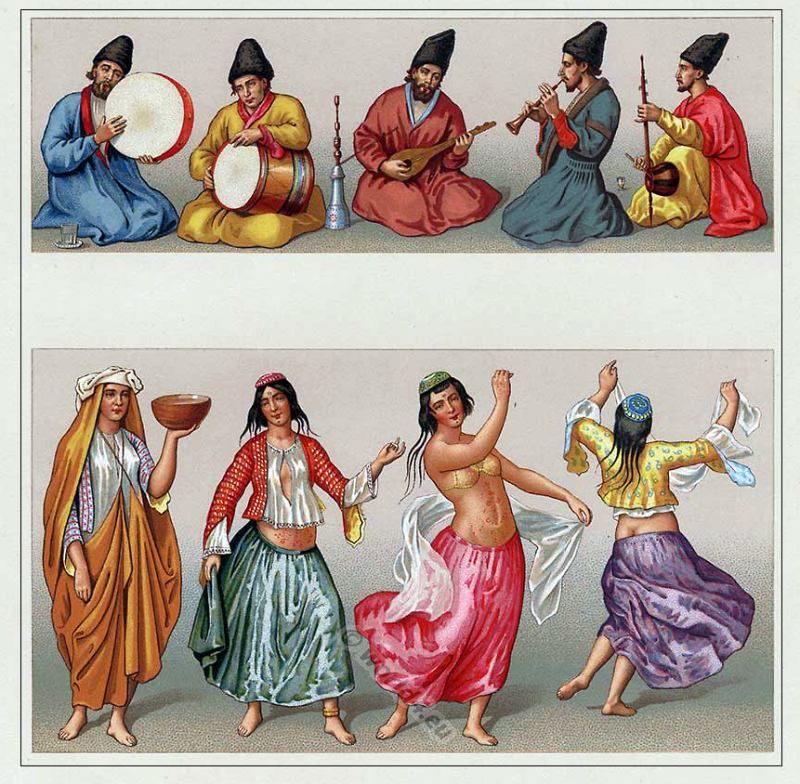

Persia, bordering Central Asia and the Middle East, is the home of Persian Dance. This dance style is fluid yet rhythmic, and emphasizes the use of hands and wrists. The movement and positioning of the body reflect the rich and refined aesthetics of Persian culture. The shape of the hands, motion of the wrists, rhythmic foot patterns, and coordination of arms and legs, are integrated to capture the Persian aesthetics in the body line, and to create a flow distinct to this culture.

The dance technique described and illustrated in this article is founded upon both ancient and contemporary aesthetics in Persian culture and, though influenced by solo improvisational dance from various Iranian ethnic groups, is not an interpretation of any particular folk dance or a representation of any particular tribe. I could refer to this technique as Iranian dance, but I have chosen to call it Persian because political tension between the United States and Iran has given the word Iranian a negative connotation. The word "Persian", however, remains nonpolitical and evokes images of an ancient civilization rich in history, beauty, and art, not to mention beautiful felines.

With a deep understanding - both intellectual and intuitive - of Persian cultural aesthetics, I have drawn parallels between the different media and identified a common thread that signifies a set of aesthetics distinct to Persian culture. The bigger challenge has been to fathom how these aesthetics manifest as movement. This remains an ongoing and very intriguing process. Through the years, as the manifestation of Persian cultural aesthetics in movement became clearer to me, I began to organize and categorize movement patterns and eventually created a pedagogy of steps that includes specific, numbered positions of the arms and hands, rules used to guide the body into the correct line, and descriptions of dynamic qualities in movement patterns and transitions. The result is a dance technique that is undeniably recognizable by Persian people as Persian, yet it is difficult to describe what makes it authentically Persian without a solid reference to any written format and virtually no historical background for contextualizing it.

The nomenclature presented here was created by me with help from my linguist friend Dr. Koorosh Angali, family, and friends, and is specific to Shahrzad Technique, which I have developed over the last two decades. It is the result of my interpretation of Persian aesthetics inherent in Persian art and their manifestation into movement, combined with my intuitive knowledge of Persian culture. Some of the movement vocabulary presented may be similar or identical to movement taught by other Persian dance teachers. In years of exploring Persian dance, I have certainly attained, through osmosis, some movements from watching other dance companies, such as Avaz National Dance Theater or Pars National Ballet, or videos of dance performances choreographed by Robert de Warren before the Islamic revolution in Iran. It is impossible for me to know how much of this information is influenced by other Persian dancers and how much is my own interpretation of Persian aesthetics translated into movement. This dance technique is solidly founded upon aesthetics that exist in Persian culture, making it appropriate to refer to it as classical Persian dance.

This dance technique is solidly founded upon aesthetics that exist in Persian culture, making it appropriate to refer to it as classical Persian dance.

Classical dance (in the Western context) is defined as "ballet", which has its origin in Italianballo (dance), which comes from Latin ballare, meaning to dance, which in turn comes from the Greek ballizo, to dance, to jump about. Therefore, any formal and established dance style from any culture could be considered the ballet of that culture (e.g., Ballet Folklorico de Mexico or Ballet du Senegal). I consider my dance form to be a classical dance of Persia/Iran, so I often refer to my dance style as Persian ballet. My goal in creating this format has been to bring form and structure to a dance style with existing and recognizable cultural aesthetics and create a system to teach and disseminate this art form.

Every dance style is composed of a technique often several techniques developed by different teachers and choreographers, particular dynamic qualities, and expression within the parameters of distinct movement aesthetics. When these components are mastered, the dancer is able to feel the dance both emotionally and kinetically the way it was intended by the choreographer, and the audience receives the correct energetic message through the dancer's expression.

When these components are mastered, the dancer is able to feel the dance both emotionally and kinetically the way it was intended by the choreographer, and the audience receives the correct energetic message through the dancer's expression.

There is a misconception among some Persians that to perform Persian dance one must be a native because the dance is learned intuitively with intrinsic cultural knowledge and cannot be taught using a systematic method of movement analysis. "Dr. Anthony Shay, professor of dance at Pomona College in Southern California", shares his thoughts on the difficulty of codified teaching of a dance style the aesthetics and dynamic qualities of which are culturally embedded in the movement.

It is extremely difficult to extract meaningful movement elements as separate analytical units to use in the classes in which I teach Iranian dance, because they are generally very individual and idiosyncratic to specific dancers. Nevertheless, certain movements are common to most dancers.Whereas non-Iranian students can more readily learn and read such artificially isolated movements, Iranian students are hard pressed to articulate and isolate from the flow of movement these actions, which they instinctively know and have learned from childhood. This is analogous to the manner in which many native speakers of a language cannot always articulate its grammar, because its linguistic organization and rules are embedded in their mental structure. (Choreophobia, 1999, 20)

I agree that Persian dance carries a specific movement flow that is intrinsic to native Persian dancers. This natural flow is a major part of the aesthetic identity of this dance style. In my years of teaching Persian dance, I have personally experienced the resistance inherent to Iranians when it comes to learning Persian dance in a step-by-step manner. It is difficult to step out of an intuitive whole-body experience and study it analytically; however, I believe that in teaching any subject matter that transcends the student's existing knowledge whether intuitive or intellectual it must be broken down into isolated parts, examined, and then carefully reassembled. This must be done skillfully, especially when recapturing the original flow is a vital part of the process.

This must be done skillfully, especially when recapturing the original flow is a vital part of the process.

Using Shays analogy of language, I assert that not only is it necessary for a non-native speaker to learn grammar through an introduction to the linguistic rules, but for a native speaker to develop his linguistic skills beyond colloquial conversation and comprehend layers of advanced concepts that will require more than his intrinsic knowledge, he must study his native language in an organized and analytical way. Similarly, to surpass social dance and develop movement vocabulary and composition, even a native Iranian must study the dance technique by breaking down the natural flow of the movement into single, analytically digestible elements. Once these layered elements are given time and practice to become integrated in the mind and body, they can feel natural and organic. Breaking down flowing movements into parts may seem artificial, as with anything that is taken out of its context, but it is a temporary and necessary part of the learning process in any subject dance is no exception.

When performing, it is important to apply the correct technique for executing movement, and developing the correct technique requires repetitive exercises. These exercises must be done diligently and with keen attention to detail in order to capture minute but important nuances in the movement style.

The following concepts and exercises demonstrate the essence of Persian aesthetics as they manifest in movement and, through diligent practice, one can gain mastery of the technique necessary to express himself within those aesthetic parameters. By learning to manipulate the body to form precise shapes and lines and produce dynamic nuances and transitions, one will achieve the type of movement flow distinct to this dance style.

Foundational Principles

The hands are perhaps the most expressive part of the body in Persian dance. While dancing, there should be a generous amount of energy flowing through the wrists, hands, and fingers and extending out the fingertips. Hand and wrist movements are fluid but can also be rhythmic in response to music. The face, head, and upper body respond to hand and arm movement in a poetic dialogue.

Hand and wrist movements are fluid but can also be rhythmic in response to music. The face, head, and upper body respond to hand and arm movement in a poetic dialogue.

Hand Shape

To bring attention to the fingers, the thumb and middle finger are drawn slightly toward each other, and the fingers are separated to allow for movement visibility. It is important to keep the fingers extended and not curled inward. I call this position dal because it roughly resembles one of the letters of the Persian alphabet (Figure 1). It also looks a bit like the mathematical symbol >. The energy is extended out of the fingertips, making the fingers as long as possible and preventing them from curving in toward the palm. This is not a stagnant position, however, so the fingers should be allowed to move, and the shape of the hand should ripple and change as the hands move, but there should be a general tendency toward the dal shape, especially during moments when the hands are intentionally still.

Figure 1a - Persian letter dal

Figure 1b and 1c - dal hand shape

Wrist Motion

Part of the fluidity of this dance style is achieved by leading arm movements with the wrists. This requires the wrists to remain relaxed but engaged and expressive. The wrists manipulate the movement and rhythm in the hands and have a strong connection to music. They are often the spark that begins a movement. The arms, and subsequently the spine and head, follow the lead of the wrists.

Below are examples of basic Persian dance movements initiated by the wrist:

Abshar

Meaning waterfall, this movement consists of a small vertical paintbrush motion of the wrists. The wrists pull the hands in opposite directions at the same time. Therefore one wrist is flexing while the other is extending. This movement can be performed in a fluid and a-rhythmic way, or with a staccato quality to accentuate the beat in the music.

Qalammoo

Qalammoo means paintbrush, and it refers to a fluid arm motion, initiated and led by the wrist. Imagine the arm and hand as a paintbrush, the arm representing the handle, the hand representing the brush, and the fingers the bristles. The wrist is the juncture of connection between the brush and the handle. As the imaginary paintbrush moves through space, the brush and bristles trail behind. In body movement, this means when the arm sweeps upward, it is the wrist that initiates the upward motion, leaving the fingers to trail along, pointing downward. Similarly, when the arm moves downward the motion is led by the wrist and so, the fingers point upward. This is also true when the arm moves in a horizontal, diagonal, or circular path.

Imagine the arm and hand as a paintbrush, the arm representing the handle, the hand representing the brush, and the fingers the bristles. The wrist is the juncture of connection between the brush and the handle. As the imaginary paintbrush moves through space, the brush and bristles trail behind. In body movement, this means when the arm sweeps upward, it is the wrist that initiates the upward motion, leaving the fingers to trail along, pointing downward. Similarly, when the arm moves downward the motion is led by the wrist and so, the fingers point upward. This is also true when the arm moves in a horizontal, diagonal, or circular path.

There is some resistance, a legato quality, in this movement that gives it a rich flavor. It feels as if the dancer is moving through water.

Qalamoo in frontal plane with side hinge

Understanding the technique of a particular dance style is crucial, and the movement vocabulary introduced in this article may give you an idea of this dance form. It is a good place to start in exploring the beautiful art of Persian dance. However, technique alone is not enough to artfully perform or choreograph in any dance style. Important elements such as understanding of dynamics and musicality, are necessary to transform a well-executed movement pattern into a work of art. In the end, it is the dancers' individual expression that will bring the movement to life.

It is a good place to start in exploring the beautiful art of Persian dance. However, technique alone is not enough to artfully perform or choreograph in any dance style. Important elements such as understanding of dynamics and musicality, are necessary to transform a well-executed movement pattern into a work of art. In the end, it is the dancers' individual expression that will bring the movement to life.

Persian Dance – The Struggle for Identity

Persian dance seems to be an obscure genre, often confused with other more popular Middle Eastern dance styles, such as Egyptian belly dance. In fact, the majority of Westerners are under the impression that Persian dance is synonymous with belly dance, which in Iran is referred to as Raghs-e Arabi or Arabic dance. Most Middle Eastern dance scholars, however, are aware of the existence of Persian dance as a distinct form, but a scarcity of teachers and information on Persian dance and its history prevents them from becoming familiar with it.

Dance, music and food are a big part of Persian culture. Families and friends often gather to enjoy each other's company, during which they prepare great feasts, play both traditional and modern music, sing old and new songs, and dance. In every kind of celebration, such as: Yalda (the winter soltice), Mehregan (the autumn equinox), Norooz (The spring equinox and the Persian new year), or simply birthday, wedding, or any happy occasion, Persians integrate dancing into the event. These events are multigenerational, and therefore the dances are passed on from one generation to the next. Professional dancers, often choreograph dances which are founded in and stem from these family and community dances.

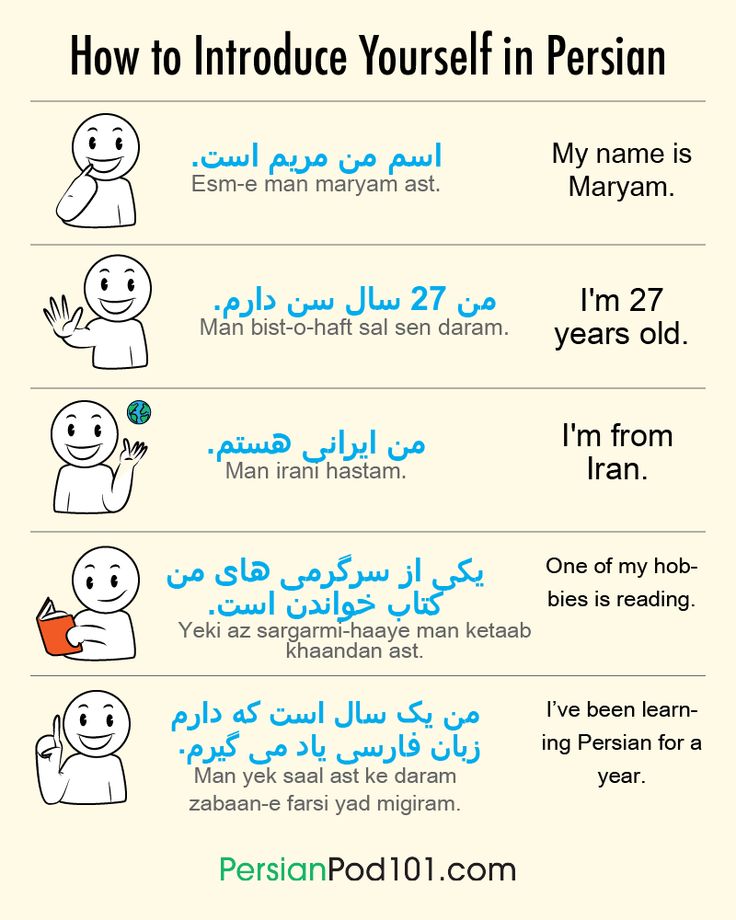

There is some confusion over the use of the terms Persian and Iranian. Though commonly used interchangeably, the former refers to an ethnicity, whereas the latter refers to a nationality. About 2500 years ago, Iran, a country on the map defined by geographical borders, was ruled by the Persians, an Iranian tribe from Persia proper (today's Fars Province). According to linguist Koorosh Angali,

According to linguist Koorosh Angali,

Under the Persian Empire (550-330 BC ) which was founded by Cyrus the Great, the land extended from the northwestern China to Egypt and Libya (in the southwest) and Anatolia to Lydia (in the northwest), including the Central Asia and today's Middle and Near East. (personal interview, 2014)

Today's Persians, the descendants of the ancient Persians, are the dominant ethnic group in Iran. Many ethnic groups, such as Kurds, Lurs, Baluch, Armenians, Assyrians, Turks, and Arabs, inhabit Iran and have their own distinct Iranian language or dialect, customs, music, and dance; however, all Iranians learn to speak, read, and write in Persian (also known as Farsi), the official language of Iran.

So, what does Persian/Iranian dance look like? Well, there are different genres, which I will briefly describe, compare, and contrast.

Genres

For almost two decades I have been exploring this rare and beautiful art form, and in my attempts to create a clear definition of Persian dance I have identified three genres.

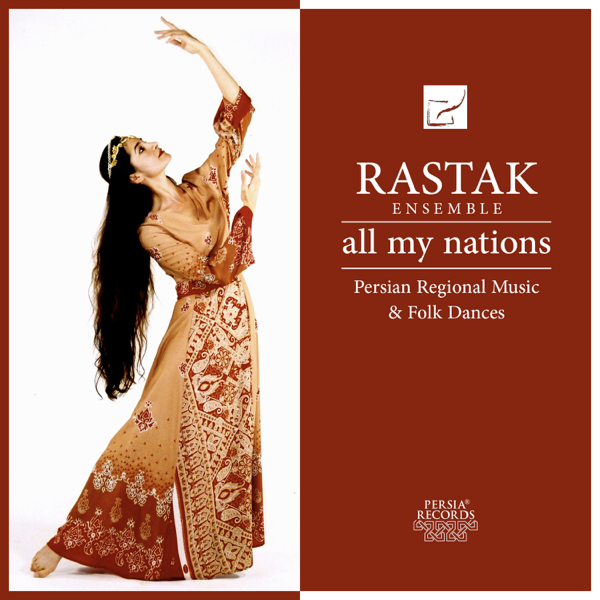

Folk Dance

Folk dance, which is tribal, regional, and often part of social ritual and ceremony, is the oldest and most likely the foundation of all other genres. Groups of dancers may contain more than one generation and both genders. These dances are intended for the enjoyment of the participants and not necessarily meant to be viewed by an audience. There are many different tribes in Iran (sometimes multiple tribes within a region) that speak their own dialect and follow their own customs. Much like the language, the dances of each region, in addition to the music and attire, are distinct. For instance, performers of a folk dance from the northern region just below the Caspian Sea in the province of Gilan, referred to as Gilaki dance, wear long skirts with several stripes on the bottom and fringed scarves on their heads. The movements include sharp isolations of the hip and beshkan, the Persian snap that uses both hands.

Another popular folk dance, this one from the southern region by the Persian Gulf, called Bandari, is very similar to Khaliji, a dance popular in several Middle Eastern countries. The word khalij means gulfboth styles of dance are from the Gulf region, one within the boundaries of Iran and the other in several other countries surrounding the Persian Gulf. The word bandar, meaning port, implies the famous Bandar Abbas, located in southern Iran at the Persian Gulf. This dance style looks so different from Gilaki that it is hard to imagine both dances existing within the same country. Bandari dance movements are very grounded, much like African dances, with the hands often held wide open and shaking. Shoulder and hip shimmies are signature movements of this dance style. The rhythmic structure and the musical instruments used are distinct to this region, and the attire is a long tunic with pants that are decorated at the bottom with beads, sequins, and gold or silver thread.

The word khalij means gulfboth styles of dance are from the Gulf region, one within the boundaries of Iran and the other in several other countries surrounding the Persian Gulf. The word bandar, meaning port, implies the famous Bandar Abbas, located in southern Iran at the Persian Gulf. This dance style looks so different from Gilaki that it is hard to imagine both dances existing within the same country. Bandari dance movements are very grounded, much like African dances, with the hands often held wide open and shaking. Shoulder and hip shimmies are signature movements of this dance style. The rhythmic structure and the musical instruments used are distinct to this region, and the attire is a long tunic with pants that are decorated at the bottom with beads, sequins, and gold or silver thread.

In northwestern Iran, which is inhabited by Turkish speakers, the folk dances are almost identical to those from the neighboring nations of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Turkey. These dances are composed of quick, rhythmic foot patterns with erect upper bodies and graceful sweeping arm motions. The athletic male dances include quick squatting and standing to the fast beat of the music, jumping, and spinning on knees.

The athletic male dances include quick squatting and standing to the fast beat of the music, jumping, and spinning on knees.

These are just a few examples of the many folk dance styles that exist in Iran today.

Social Dance

Social dance, or raqs-e mehmouni (party dancing), also sometimes called Raqs-e Tehrani (implying urban dance, as opposed to village dances), is done primarily at celebratory social functions in urban areas of Iran and social events or Persian dance parties and dance clubs in the diaspora where dancing in public is permitted (public display of dance has been outlawed in Iran since the Islamic revolution of 1979). This dance style is informal, meaning that it does not require formal training, yet it embodies the aesthetics of Persian culture in a detailed and sophisticated way. A trained ballet dancer in the West spends years gaining mastery of the body through disciplined repetitions of specific challenging movement exercises to achieve perfect execution of choreographed movement. The trained dancer is also consciously aware of and can verbally articulate the description of the exact movement pattern she is performing. An untrained or intuitive dancer may simply dance to express herself without paying much attention to movement patterns. In the context of social dance, Persians not formally trained in dance, often with little awareness of their movement patterns and no intentional mastery of their body, can intuitively and often quite skillfully perform authentic Persian movements to Persian music. Depending on the ability of the dancer, the movements can be mediocre and repetitive or innovative, dynamic, and entertaining.

The trained dancer is also consciously aware of and can verbally articulate the description of the exact movement pattern she is performing. An untrained or intuitive dancer may simply dance to express herself without paying much attention to movement patterns. In the context of social dance, Persians not formally trained in dance, often with little awareness of their movement patterns and no intentional mastery of their body, can intuitively and often quite skillfully perform authentic Persian movements to Persian music. Depending on the ability of the dancer, the movements can be mediocre and repetitive or innovative, dynamic, and entertaining.

My experience in teaching non-Persians has led me to the conclusion that it is most helpful for a non-Persian dancer to train formally in this social dance style. There are so many minute and intricate cultural nuances embedded in the technique, and so much of the style depends on the dancers reaction to and interpretation of the music, that unless the dancer was engulfed in and surrounded by Persian culture at a young age, her intuitive understanding of this movement style and the music would not be enough for her to become proficient in it.

Classical Persian Dance

For years I have wondered about the appropriate label for my dance style. I hesitate to call it "court dance" because I do not perform it in Persian courts, nor is it a replica of dances historically performed at Persian courts. I have at times referred to it as art dance, but that title seems a bit vague. I often use the term classical Persian dance to distinguish it from Persian social dance and folk dance. The word classical, however, often refers to Western traditions, so, uncertain of the implications of the term for authentic Persian dance, I decided to look to the dictionary for some guidance.

The word classical implies a structured form that is established and accepted as a model and characterized by attention to balance, proportion, and controlled emotion. Most definitions use words such as structure, order, and restraint, and at least one describes the word as form and structure founded upon existing aesthetics. We can conclude, then, that the term classical in the context of dance implies a movement style that is based on form and structure and has a codified method, with a restraint on indulgent emotional expression. I think all dancers would agree, however, that the element of emotion is a vital component in dance, and restraining the emotional expression in the art form would diminish its beauty and hinder its artistic integrity. And since Persian arts such as poetry and miniature painting are most often based on passionate emotions of love and yearning, it could be said that restraint on emotional expression is not very "Persian". So, let us focus on the part of the definition that implies form and structure.

I think all dancers would agree, however, that the element of emotion is a vital component in dance, and restraining the emotional expression in the art form would diminish its beauty and hinder its artistic integrity. And since Persian arts such as poetry and miniature painting are most often based on passionate emotions of love and yearning, it could be said that restraint on emotional expression is not very "Persian". So, let us focus on the part of the definition that implies form and structure.

Many cultures have a formal, codified dance structure, which can be referred to as the country's classical dance. For example, India possesses classical dances that go back thousands of years. These dances are embedded in religious philosophies and rituals and written in manuscripts that are followed rigidly by Indian dance scholars and educators. In the West, classical ballet was developed in Europe in the 15th century. It began in Italy and later became popular in France, Russia, and eventually America. It is now well known and practiced around the world. In both classical Indian dance and European classical ballet there exist an established technique, a right and wrong way to execute the movements, and specific dynamic qualities to capture. It is, therefore, easy to detect any deviation from the originally established form.

It is now well known and practiced around the world. In both classical Indian dance and European classical ballet there exist an established technique, a right and wrong way to execute the movements, and specific dynamic qualities to capture. It is, therefore, easy to detect any deviation from the originally established form.

For Persian dance, there is no evidence of any set of codified movements inside or outside Iran, nor is there any accessible archive of ancient choreographed dances and pedagogy that would be treated as an established and formal method for teaching and performing. What is known as authentic Persian dance includes folk or tribal dances, many of which may have their own nomenclature and set of established movement patterns, and social dances performed in urban areas by the natives. These dance genres are by nature intuitive and emotionally expressive and, although they are performed within historically set aesthetic parameters, they do not share one codified format, vastly different from classical dance as defined by dictionaries. However, Persian dance, as intuitively based as it may be, is composed of an informal movement vocabulary and has the potential for codification. Dance historian Anthony Shay suggests "the performance of this dance tradition does not derive from a formless, meaningless collection of movements, but rather forms a coherent movement system&like Persian classical music, dance is capable of being systematized, a prerequisite for the creation of an aesthetic system." (Shay, Choreophobia, 1999, 177)

However, Persian dance, as intuitively based as it may be, is composed of an informal movement vocabulary and has the potential for codification. Dance historian Anthony Shay suggests "the performance of this dance tradition does not derive from a formless, meaningless collection of movements, but rather forms a coherent movement system&like Persian classical music, dance is capable of being systematized, a prerequisite for the creation of an aesthetic system." (Shay, Choreophobia, 1999, 177)

When trying to define my style of Persian dance, I repeatedly find myself in a vast space filled with abstract imagery, concepts, memories, and emotions that make sense to me on an intuitive level but have no tangible thread of form or history to follow. Having been born and raised in Iran, I am intuitively familiar with the cultural aesthetics. To get a deeper understanding of Persian dance, I use my intuitive knowledge of Persian aesthetics and my academic background in the art and science of dance. I have also spent the last two decades observing and contemplating the common aesthetics apparent in various Persian art media. There is a theme of curvilinear lines with dynamic but graceful brush strokes in Persian paintings and calligraphy. Compositions often consist of circular patterns, smooth transitions between images, and distinct and dynamic juxtaposition of color and imagery. There are also geometric design elements in Persian architecture that carry similar visual motifs to the painting and calligraphy. The same dynamic nuances translate into Persian musical compositions and rhythmic structures.

I have also spent the last two decades observing and contemplating the common aesthetics apparent in various Persian art media. There is a theme of curvilinear lines with dynamic but graceful brush strokes in Persian paintings and calligraphy. Compositions often consist of circular patterns, smooth transitions between images, and distinct and dynamic juxtaposition of color and imagery. There are also geometric design elements in Persian architecture that carry similar visual motifs to the painting and calligraphy. The same dynamic nuances translate into Persian musical compositions and rhythmic structures.

With a deep understandingboth intellectual and intuitiveof Persian cultural aesthetics, I have drawn parallels between the different media and identified a common thread that signifies a set of aesthetics distinct to Persian culture. The bigger challenge has been to fathom how these aesthetics manifest as movement. This remains an ongoing and very intriguing process. In the last 19 years, as the manifestation of Persian cultural aesthetics in movement became clearer to me, I began to organize and categorize movement patterns and eventually created a pedagogy of steps that includes specific, numbered positions of the arms and hands, rules used to guide the body into the correct line, and descriptions of dynamic qualities in movement patterns and transitions. The result is a dance technique that is undeniably recognizable by Persian people as Persian, yet it is difficult to describe what makes it authentically Persian without a solid reference to any written format and virtually no historical background for contextualizing it. It is my hope that this format/technique, described in detail in my book, The Art of Persian Dance, is the first step to establishing a codified system for Persian dance world-wide. As the art form gain popularity, more dancers need access to a systematized way of learning and understanding this complex dance style.

The result is a dance technique that is undeniably recognizable by Persian people as Persian, yet it is difficult to describe what makes it authentically Persian without a solid reference to any written format and virtually no historical background for contextualizing it. It is my hope that this format/technique, described in detail in my book, The Art of Persian Dance, is the first step to establishing a codified system for Persian dance world-wide. As the art form gain popularity, more dancers need access to a systematized way of learning and understanding this complex dance style.

Famous dancers

There have been few famous dancers recorded in the history of Persian dance. In fact, there is little recorded information on Persian dance in general. However, in more recent history, 20th century, Robert de Warren, a British ballet dancer and director has become a well-known name. He was invited by the Ministry of Culture in the 1960's to train Persian dancers in Ballet and to invite foreign Ballet dancers to perform in Ballet productions. Being intrigued by the dance of the natives, he eventually began to interpret Persian dance and created choreography in that style. He also recorded folk dances of various regions. Unfortunately these recordings were destroyed during the political revolution on 1978, which ended his stay in Iran.

Being intrigued by the dance of the natives, he eventually began to interpret Persian dance and created choreography in that style. He also recorded folk dances of various regions. Unfortunately these recordings were destroyed during the political revolution on 1978, which ended his stay in Iran.

One of the soloist in Mr. Warren's company was Farzaneh Kaboli, who still teaches dance in Iran, although the public display of dance is prohibited by the current regime. She is allowed to produce concerts, given all the dancers and the audience are females, and even then, her choreography is subject to censorship and possible rejection. Each show must be approved by the government before it can be performed. Haydeh Changizian, former prima ballerina of Iran (before the Islamic revolution), is suffering the same fate as Ms. Kaboli.

Dr. Anthony Shay is also an expert in Persian culture and dance. He lived in Iran for a number of years and has studied many international dances. He directed AVAZ International Dance Theater in Los Angeles for many years, and is now faculty at Pomona College.

Nima Kian is a ballet dancer who used Persian themes in his work. He has also written about Persian dance history. Robin Friend, dancer and choreographer in Los Angeles, is a long-time Persian dance, music, and culture connoisseur and has written several articles on the subject. Shahrokh Moshkinghalam, a contemporary dancer based in France, often uses Persian poetry and literature as his inspiration for choreography. And Helia Bandeh, residing in Holand, is an explorer of Persian dance and has created her own creative voice in this genre. These dancers are well-known in the small circle of Persian dance enthusiasts. However, because Persian dance is not a popular dance form and most people are unaware of its existence, these dancers are not "world famous".

It seems the evolution of Persian dance as an art form has always been a struggle and continues to be one, for both political and social reasons. Those of us in the diaspora struggle to bring awareness to this rare, rich, potent, and beautiful art form.

It is my hope that this article will stimulate the curiosity of dancers and scholars, and thus take us one step closer to bringing recognition for this under-defined art.

Traditional Persian dance: Arabic dance in reverse

Traditional Persian dances

Iran (former Persia) is the birthplace of Persian dances. Typically, Persian dances differ from Arabic dances in that Arabic dances emphasize the movement of the hips, while Persian dances mainly involve the upper body.

In Iran, dance and music are an integral part of holidays such as: Yalda (winter solstice), Mehregan (autumn equinox), Norooz (spring equinox and Persian New Year). Also, traditional dances are often performed at birthdays and weddings. During these events, both young people and the elderly participate. Therefore, folk festivals are a great opportunity to transfer knowledge about traditional dances from one generation to another. nine0004

The most common traditional dances staged by contemporary choreographers include Karevan, Ghalibaf, Be Yad-e Gilan, Chai-khooneh, Baroon and Aroosak.

Traditional Persian dances

"Karevan"

The style of this dance is called "Bandari" (the word "Bandar" means "port" in Persian). The dance style and musical accompaniment were strongly influenced by both Arabic and African rhythms and movements. The dance is performed in celebration of a long journey and return from it. nine0004

Traditional Persian dances

"Ghalibaf" (Carpet weaver)

The choreography of this dance is of a woman weaving a carpet. Considering that this is her main way of earning money, she has been doing this every day of her life since childhood. The geometric patterns of the carpet, along with the monotonous repetitive motions of weaving, put the woman into a trance state and she begins to dance, expressing her inner music through dance.

Traditional Persian dances

"Be Yad-e Gilan" (In memory of Gilan)

This is a traditional dance of the Ghasemabad people in northern Iran. The dance tells about the harvest of rice, the most common and popular food in the region. As with most folk dances, children and adults dance together to celebrate the bountiful harvest.

The dance tells about the harvest of rice, the most common and popular food in the region. As with most folk dances, children and adults dance together to celebrate the bountiful harvest.

Traditional Persian dances

"Chai-khooneh" (Tea house)

This style of Persian dance is called Jaheli. The word Jahel means "uneducated underage person" and is used to refer to Persian street hooligans. A teahouse is a typical place where people gather to chat over a cup of tea. The dance tells about Iranian life, when sedate people and hooligans gather nearby for communication. nine0004

Traditional Persian dances

Baroon (Rain)

This is a prayer dance performed to call for rain. This dance describes the bounty of the harvest and the unity of the villagers who worked hard to provide for their families.

Traditional Persian dances

"Aroosak" (Doll)

This dance is part of a theatrical performance in which a child's doll comes to life while the child sleeps. Dance plays on the fine line between imagination and reality. nine0004

Dance plays on the fine line between imagination and reality. nine0004

Persian Dance - frwiki.wiki

Dance in Iran has a long history and has evolved over time since the early Achaemenids. Indeed, excavations over the past 30 years provide access to evidence of dance in Iran since the advent of the cult of Mithra in 2000 BC. For this ancient people, dance can be seen as an important social event and/or religious ritual. However, political restrictions on Iranian and dancing occurred after the revolution in 1979, dance and music are always frowned upon, if not banned for a time, but this ancient story is still going on, sometimes in a more private setting.

Dances in Iran can take place in many different contexts; such as social events, initiation rites, exorcisms, and ceremonies. These contexts can be associated with traditional or historical events (national holidays, religious holidays, pre-Islamic festivals, tribal migrations...) or take place during unplanned events. nine0004

These contexts can be associated with traditional or historical events (national holidays, religious holidays, pre-Islamic festivals, tribal migrations...) or take place during unplanned events. nine0004

Summary

- 1 Rhythm of music

- 2 Main types of dance

- 2.1 Improvisation

- 2.2 Pro / Show

- 2.3 In a straight line or in a circle, holding hands

- 2.4 Circle without holding hands

- 2.4.1 Dancing with objects

- 2.5 Ceremonies

- 2.5.1 Cyclic rituals

- 2.5.2 Zurkhane

- 2.5.3 Itself

- 2.5.4 Trance or healing dances

- 3 styles

- 4 links

- 5 External links

- 6 Bibliography

Rhythm of music

The most common rhythm used for dancing in Iran is 6/8, which is denoted by the term shir-e madar (literally: "mother's milk"). Rhythm and its variations can be found in dance music throughout Iran. The division of the meter always follows the accents of the melody.

The division of the meter always follows the accents of the melody.

However, interesting rhythmic variations can occur. For example, the first beat of a measure can be extended to nearly two beats (thus creating a 7/8), as is the case in a dance style called Motrebi .

Basic types of dance

Improvisation

This type of dance is the most common in Iran for a very large number of social events. Characteristically, the dancer has a certain number of movements that he combines to express himself. This type of dancing in a family setting has undoubtedly been the most common in the Middle East for centuries. Another feature is that the participants never touch each other, do not hold on to the waist, even when dancing in pairs. In addition, the dancers, even when in a circle, do not perform any programmed movements. nine0004

The most common form of dance among the urban youth of Iran today is called Tegrani ( raqs-e tehrânî ). This dance is related to the dances of the Uyghurs, Uzbeks, Anatolian Turks, Armenians, and the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean. Depending on the social situation (restrictive or not), groups or couples may or may not mix. In Tehran dance, the arms are held at shoulder level, the emphasis is on arm movements, facial expressions, and relatively gentle movements of the lower body and hips. All movements are improvised to music in 6/8 rhythm called reng . In its most complex form, this dance style is the foundation of professional Iranian dance. It is the most common dance form among Iranians living outside of Iran; and we can meet him at all important emigrant events where dance is an integral part of the entertainment.

Depending on the social situation (restrictive or not), groups or couples may or may not mix. In Tehran dance, the arms are held at shoulder level, the emphasis is on arm movements, facial expressions, and relatively gentle movements of the lower body and hips. All movements are improvised to music in 6/8 rhythm called reng . In its most complex form, this dance style is the foundation of professional Iranian dance. It is the most common dance form among Iranians living outside of Iran; and we can meet him at all important emigrant events where dance is an integral part of the entertainment.

Improvised dances can also be found in the villages and tribes of Iran. For example, in the dances of the Baloch women, they improvise, dancing to the rhythm of rank . In addition to hand movements, they keep the rhythm by banging their metal bracelets together.

Professional / Show

Show dance is a style of dance based on the raqs-e tehrani style, taken to the point of becoming an art for others. Movements require exceptional body flexibility, grace and a variety of facial expressions. In professional dance, dancers may also manipulate objects such as tea glasses and small plates attached to their fingers. These professional dancers are called motrebi or lots . Throughout Iran, especially in urban areas, motrebi groups include musicians, singers, dancers, actors and others.

Movements require exceptional body flexibility, grace and a variety of facial expressions. In professional dance, dancers may also manipulate objects such as tea glasses and small plates attached to their fingers. These professional dancers are called motrebi or lots . Throughout Iran, especially in urban areas, motrebi groups include musicians, singers, dancers, actors and others.

Dance is also an integral part of the traditional theater Rû-Hawzî, in which each role has its own style of dance; Hadji Firöz, for example, the roles of women played by men, etc. These groups played in the streets or were available for weddings and other parties. These shows could be very vulgar and require very rough and suggestive movements and words. nine0004

In a row or in a circle holding hands

Kurdish dance on the occasion of the wedding in Sanandaj.

Line or circle dances, in which the dancers hold hands, are the most common type of dance in the Near and Middle East, as well as in Europe. A common feature of all these dances is limited improvisation. The emphasis is on leg movements and body postures rather than facial expressions and upper body movements.

A common feature of all these dances is limited improvisation. The emphasis is on leg movements and body postures rather than facial expressions and upper body movements.

This type of dance is widespread in Iran, especially in the west. One of these most common dances found in Azerbaijan is the six-beat dance, in which the dancers, holding each other by the waist, move in a line, taking one step to the right (1), one step to the left (2), a step to the right ( 3), lifting the left foot (4), step to the left (5), lifting the right foot (6). This is also Israel's step horo , Bulgarian horo and other similar dances found in Europe and other countries in the Middle East.

In Kurdish dancing, the dancers stand very close to each other, their hips almost touching. Fingers interlaced, elbows bent at a right angle (or straight arms laid behind the body). The main movement is to lower the body above the hips and move the legs vigorously. The upper body forms a single mass. This dance is reminiscent of the Arabic debka and has more Arab world influences than Central Asian influences. nine0004

This dance is reminiscent of the Arabic debka and has more Arab world influences than Central Asian influences. nine0004

One of the most popular dances among the Assyrians is sheikhani . We hold hands, as in the Kurdish dance described above. First, the dancers face the center of the circle. They all approach the center together, then move away. When the dancers return to take their place in the original circle, they turn to the right, keeping their hands tied (right hand in front of the body and left hand twisted behind the back), take a few steps in the direction of the circle, then resume movement. The steps may vary depending on the village, but the basic principle remains the same. nine0004

In a circle without holding hands

When the hands are not held, a greater variety of dance steps is possible, including improvisation and dancing with objects, because the hands are free and the dancer is free from direct influence.

Khorasan and Balochistan dances belong to this type. Each dancer takes the same steps in unison, but they can assume different poses, which would not be possible if they were holding hands. Male dances of the Turkmen people in Iran are accompanied by rhythmic vocalizations that are used to accompany the dance. nine0004

Each dancer takes the same steps in unison, but they can assume different poses, which would not be possible if they were holding hands. Male dances of the Turkmen people in Iran are accompanied by rhythmic vocalizations that are used to accompany the dance. nine0004

Another region of Iran where you can meet a round dance without holding hands is the Persian Gulf. The folklore of this region shows great influence from neighboring Arab cultures such as Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, as well as Africa (probably through the African slaves brought to the Persian Gulf). The standard tempo is 6/8, but some rhythms focus on 1 - m , 5 - m or 6 - m times, which gives a characteristic impression, repeated from bar to bar. This style of rhythm shows an African influence. The dance steps are basic, each moving in a lead line, the emphasis is on very fast and sharp shoulder movements (which are actually performed by the torso movement), and the arms are held at shoulder level, fins out. Dancers may also be accompanied by handclaps. nine0004

Dancers may also be accompanied by handclaps. nine0004

Dance with objects

When dancers are not physically bound, their hands can move in all sorts of ways, including manipulation of objects such as sticks ( Chûb-bazî ) or scarves. There are many examples of women dancing with the headscarf in southwestern Iran, in the Qashqai, Lors and Bakhtiyar tribes. It is believed that these dances originated from the imitation of the activities of women in their daily lives, such as weaving and spinning. Qashqai define two types of dance: akor hali , slow and heavy dance, and lakke hali , light and fast dance.

You can also use everyday items such as dishes. An example from northern Iran is the "rice dance" performed by the women of Gilan. In this dance, a woman dances with a large utensil placed in front of her body or head and imitates the actions taken while cooking rice.

ceremonies

The following dances are grouped under the term "ceremonies". These dances are closely related to their context and cannot be separated from it. The forms of these dances are less important than their context and purpose. nine0004

These dances are closely related to their context and cannot be separated from it. The forms of these dances are less important than their context and purpose. nine0004

Cyclic rituals

Iran is a country populated mainly by Indo-European peoples whose pre-Islamic traditions are still observed. These examples include Nowruz (new year on the vernal equinox) and Shab-e yalda (winter equinox). In northwestern Iran, these celebrations sometimes include dancing, sometimes associated with winter, fertility, and the return of spring. These events are directly related to rituals such as Kukeri and Lazaruvane in Bulgaria and similar rituals in Anatolia. During these events, groups of men move from house to house, singing, reciting poetry, dancing, and collecting money or food. Thus, the purpose is to bring good luck and fertility, as well as ensure the end of winter and the return of spring. nine0004

Zurkhaneh

Zurkhaneh (literally "house of power"), is a context that can be considered part ceremonial and part display. The building is centered around a courtyard around which the men are stationed, and a gallery for the master ( Ostad ) or spiritual leader ( Morshed ) and musicians. The musical accompaniment is now limited to percussion and recitation of passages of the Shahnama from Ferdowsi. Several rhythms are used and a wide variety of movements are associated with them, including displays of power generated by handling heavy objects (wooden weights and metal chains) and displays of flexibility. nine0004

The building is centered around a courtyard around which the men are stationed, and a gallery for the master ( Ostad ) or spiritual leader ( Morshed ) and musicians. The musical accompaniment is now limited to percussion and recitation of passages of the Shahnama from Ferdowsi. Several rhythms are used and a wide variety of movements are associated with them, including displays of power generated by handling heavy objects (wooden weights and metal chains) and displays of flexibility. nine0004

Itself

Sama is part of the religious ceremonies of the dervish brotherhoods in Iran (the orders of Nematullahi, Oveisi and Aliollahi), representing a form of dance. Members gather at haneke , listen to the spiritual master recite the mystical verses of Hafez and Rumi, and find certain words in rhythm ("Allah" or "Ali"). What follows is a kind of dance in place until some fall into a trance or exhaustion. They think that by moving their body in this way, they drive it away from evil and achieve union with God. nine0004

nine0004

Trance or healing dances

Musical exorcisms are performed in some parts of Iran to deliver those affected by evil spirits. These exorcisms consist of playing music and putting the "sick" into a trance, a state in which the exiled person eventually rejects the evil spirit. In this type of dance, movement is not of great importance, what is important is the healing power of the dance.

Styles

- Baba Karam

- Bandari

- Bojnurdi dance

- Chub bazi

- Classic Persian court dance

- Hajj Naranji dance

- Kereshmeh

- Khaliji dance

- Harman dance

- Khorasan dance

- Kurdish dance

- Latar dance

- Lezgi dance

- lori dance

- Matmati

- Mazandarani dance

- Motrebi dance

- Kasemabadi

- Rax-i Chobbazi

- Raqs-e Parcheh nine0077 Ru-Hosey

- Herself

- Shamshir dance

- Tent dance

- Tehran dance (Tehruni)

- Zaboli dance

- Zargari Dance

Recommendations

- ↑ (in) "Avaz" - Stanford University Persian Students Association (accessed June 11, 2006).

External links

- Persian folk dances (VIDEO)

Bibliography

- R.S. Blum - Music in contact: the development of oral repertoire in Mashed, Iran. Oberlin College Doctoral Thesis, 1972.

- J. During - Emotion and Trance: Musical Exorcism in Balochistan . Cultural Parameters of Iranian Musical Expression, Margaret Cayton and Neil Siegel, eds. Persian Performing Arts Institute, Redondo Beach, 1988.

- SA Enjavi - Jashnâ-ha wa âdâb wa mo'taqadât-e zemestân: Jeld-e avval. nine0120 Tehran, 1352–1354 / 1973–1975 and Jashna-ha wa adab wa mo'taqadat-e zemestan: Jeld-e dovvom. Tehran, 1352–1354 / 1973–1975

- M. Rezvani - Theater and dance in Iran , Paris, 1962.

- Modern Persian dance in Iranica encyclopedia, volume VI, chapter 6

| Persian Art | |

|---|---|

|

| Dance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Current main genres |

| |

| Regional dances |

| |

| Dances |

| |

| Technical |

| |

| Other topics |

| |

Learn more

Learn more

- How much are dance shoes

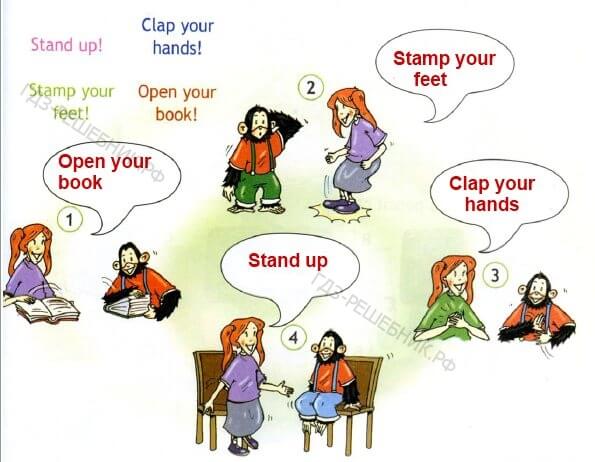

- How to do the dance

- How to dance on your hands

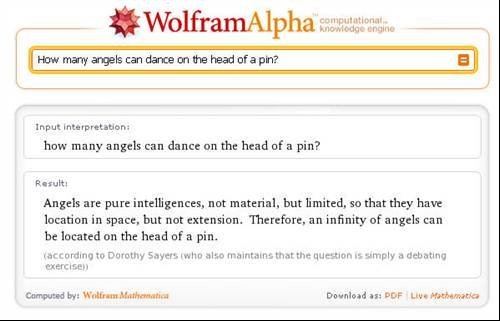

- How many angels can dance on the head of a pin meaning

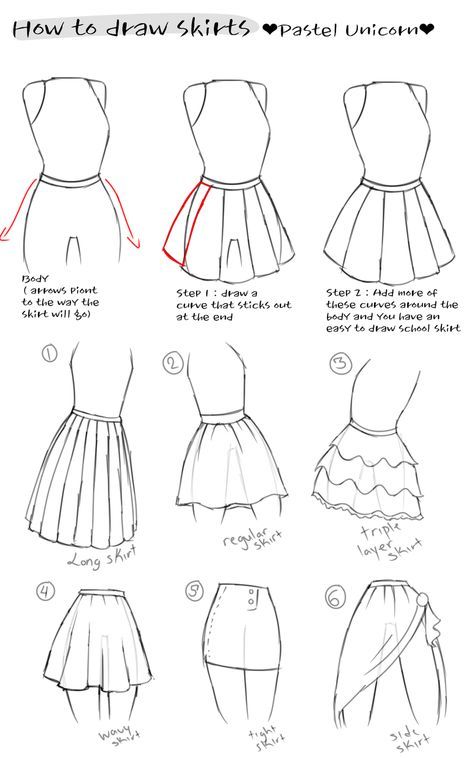

- How to make your own dance clothes

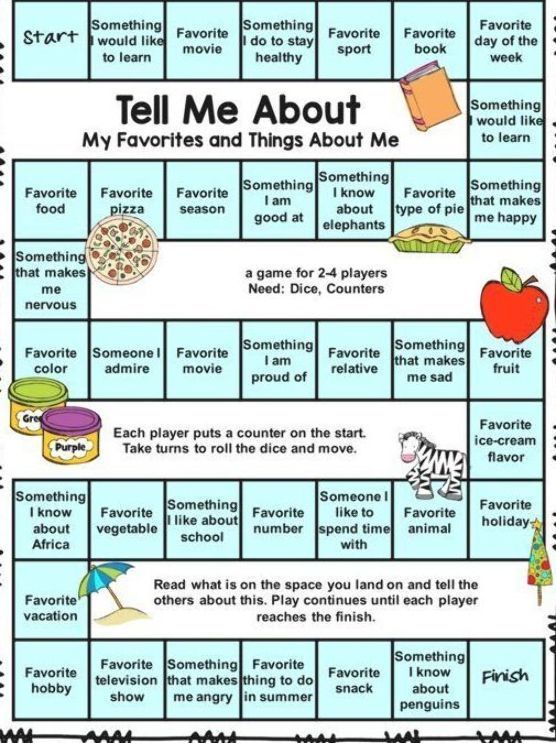

- How do you learn tiktok dances

- How to learn salsa dance at home

- Learn how to line dance

- How to dance for 8 year olds

- How to dance greek zeibekiko

- How to loose weight by dancing