How to dance like lil buck

Lil Buck: Walking on Water

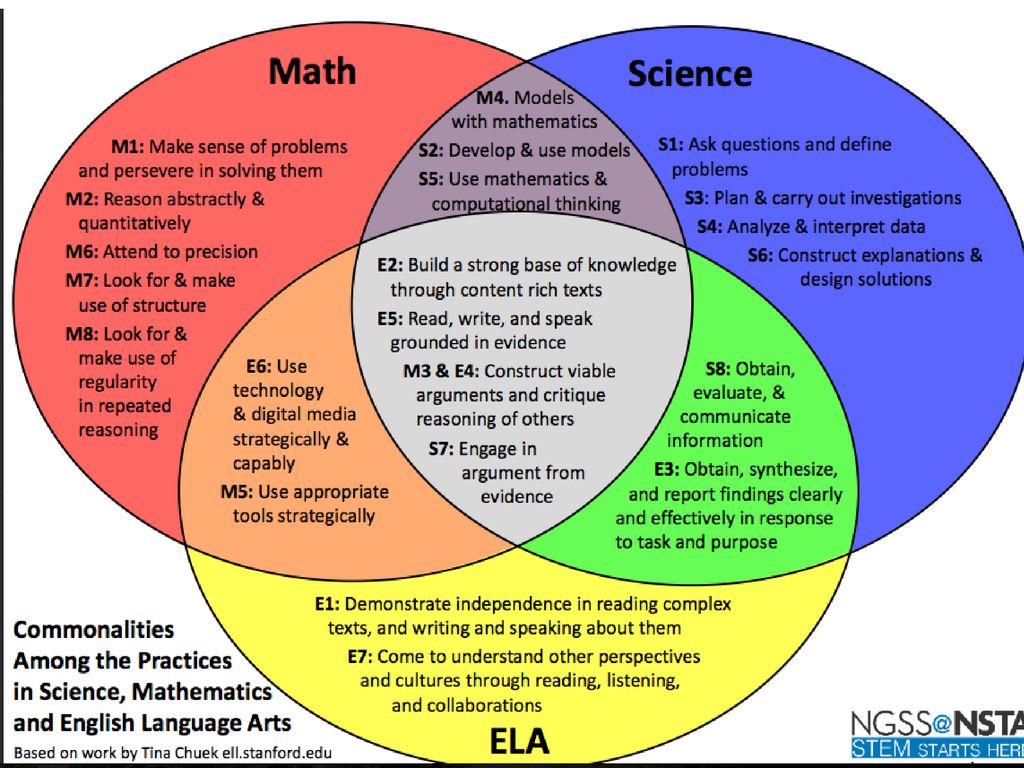

Buck went to the Disney Concert Hall in downtown LA to a performance by Ma where they planned to meet. “Yo-Yo gave me the biggest hug,” he remembers, “ and he says, ‘I want to try something,’ so we went out to the hallway and he started playing ‘The Swan,’ and I started dancing. It was magic.” They eventually coordinated a performance at a meeting between different creative celebrities to incorporate the arts in education that ended up in the viral video recorded by Spike Jonze.

What I originally loved so much about the video was the shocking departure from what I was used to seeing with the sort of classical music like “The Swan.” I expect careful, reserved expressions that find confidence in their surviving antiquation. I don’t expect what Lil Buck does. In a way, I felt embarrassed by my reaction to Lil Buck’s dancing. Why is it that we find discomfort in the pairing of art forms? What would be possible if we found ways to destroy the barriers of relation?

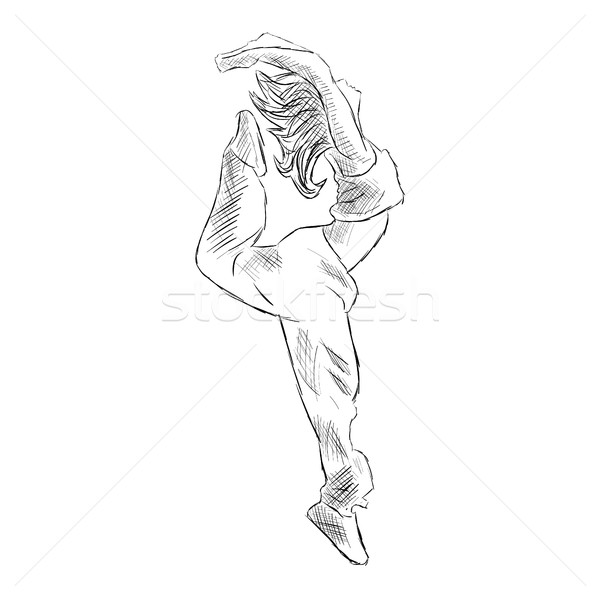

For an artist like Lil Buck, it’s not that his art asks these questions. Rather, his art is a rare moment of explanation. An answer, unexpected. When I ask him how it felt to jook with Yo-Yo Ma, he admits, “I can't even describe the feeling,” and continues, “it felt natural and it felt real for me because that was who I am.” To Buck, dancing with Yo-Yo Ma was a product of a lifetime of finding his voice. “I didn't grow up with much of a voice,” he says, “I didn't grow up thinking there was anything special about me. I knew that this was something I could speak to. This was something that people can understand.”

It was an unexpected moment for Buck, an accomplishment he didn’t expect to achieve, blending the conservative, elite, and aged world of classical music with Memphis jookin’, merging a world felt unattainable to someone like Buck with a form that, to him, was once unattainable. To destroy boundaries like this is deserving of a master that has himself has done the impossible already in his life. “To present street dancing like Memphis jookin’ to the classical world and have them see for themselves that street dancing an art form as any other dance, any other art,” he slows, “it’s beautiful. Like growing a rose out of concrete.”

Like growing a rose out of concrete.”

Buck continued to grow and spread the message of Memphis jookin’ to all those who would look. Over the next ten years, he would dance with Madonna at the Super Bowl, model for fashion catalogs, perform with the New York City Ballet, organize more collaborations with Yo-Yo Ma, and appear in more Spike Jonze movies. And yet, even with all of these collaborations, it took time for Buck to create the sort of project that was by and for himself. Not “the jooker,” not, “the street dancer that performed with Yo-Yo Ma,” not, “Madonna backup dancer,” but just as Charles “Lil Buck” Riley.

“I’ve always wanted to touch on who I am as a person,” he explains, “I speak my truth in my dance but I never got a chance to tell my own story. I never got to express the traumas I went through.” Although he was appearing with some of the biggest names in all corners of the art world, he didn’t feel as though anyone knew who he was beyond the dancing.

Recently, Buck was teaching a dance class with Red Bull, who regularly sponsors dancers, and started speaking to different people at the company about creating a video. He got in touch with director David Javier to start on something, a video, that would just be about Buck.

Buck grew up close to the church with his parents being dedicated Christians. “I think choir is a big reason I got so passionate about dance,” he says. “I always thought the choir was where the holy ghost was. When they started singing, I couldn’t control myself. I would jump up and start moving. And my mom would scream and say, ‘My son got the holy ghost!’ These are the moments I never get to talk about.”

Buck told David about his past, everything he went through as a child, and how the recent Black Lives Matter protests were bringing out memories of his life in Memphis, dealing with police brutality and gun violence within his community. So they made a video, released one week ago, titled, “Nobody Knows,” a dance collaboration with Pastor T. L. Barrett and The Youth for Christ Choir. It’s a short video, a little less than five minutes, that tells a lifetime. A boy from Memphis, reaching outside of what is human, touching hands with God. A manifestation not only of personal history but also community memory. It encompasses pain and the love and hope found in common strength. And it’s a dance.

L. Barrett and The Youth for Christ Choir. It’s a short video, a little less than five minutes, that tells a lifetime. A boy from Memphis, reaching outside of what is human, touching hands with God. A manifestation not only of personal history but also community memory. It encompasses pain and the love and hope found in common strength. And it’s a dance.

“I couldn't hold myself back,” Buck remembers. “I started to cry in some instances because it was something so personal to me and something that. I feel like I got to get off my chest and I got to speak through in the best way I knew. I'm actually speaking to your soul through dance, my truth. This was me out there naked.”

I half expect when I watch “Nobody Knows” for a singer to appear at some point in the video and begin to perform along with the themes, and yet it would feel out of place. “Nobody Knows” is a landmark for Buck as the central subject. It’s a departure from an empty sort of emotion that Superbowl dancers may know far better than Memphis street dancers: feeling like your work isn’t being seen. “Growing up jookin’,” Buck starts, “we take pride in the time and effort we have to do to cultivate this art that we've been growing. And we've been training ourselves. We're craftsmen, man. We're artists. We’re not just background dancers for other artists.”

“Growing up jookin’,” Buck starts, “we take pride in the time and effort we have to do to cultivate this art that we've been growing. And we've been training ourselves. We're craftsmen, man. We're artists. We’re not just background dancers for other artists.”

While Buck reached heights in his career that he never expected growing up in Memphis, he found a surprising distance from the appreciation of his form the bigger he got, and it’s a problem all dancers in the industry face. “I'm working really hard to try to inspire the dance community,” he says. “Hone in on who you are as an artist and invest in that.” Buck feels especially passionate about making sure that those within the Black community, who are historically exploited within the dance sphere, are not undervaluing the power they have through movement. “This is a mission for me,” he states, “to show the Black kids in my community that they have a voice with their dance. You have power with your dance. As long as you focus and hone in on what you do, and work really hard at what you love. Don’t take no for an answer. You can make this happen for yourself.”

Don’t take no for an answer. You can make this happen for yourself.”

I can’t tell if Buck’s dancing is what it looks like to be touched by God, or if it’s the sort of thing that makes others believe they are witnessing an act of God. I imagine witnessing Lil Buck perform may feel similar to how it felt to witness the Chicago Bulls win their first NBA championship against the Magic Johnson LA Lakers led by a young man named Michael Jordan. Perhaps it is how those sitting in the Vivian Beaumont Theater felt when they saw a young woman named Whitney Houston perform “Home” on The Merv Griffin Show in 1983. It must have been what Lil Buck felt when he first saw Michael Jackson dancing on TV when he was a kid growing up in Memphis.

But, one of the most inspiring things I found in my conversation with Lil Buck was realizing that he doesn’t see himself the way that I or any of his admirers see him. After a lifetime of beating impossible odds, he reflects on his career with humility and compassion for young artists like the kid he was watching Michael Jackson on VHS.

Dancer ‘Lil’ Buck’ Riley brings jookin to the fore

1 of 2

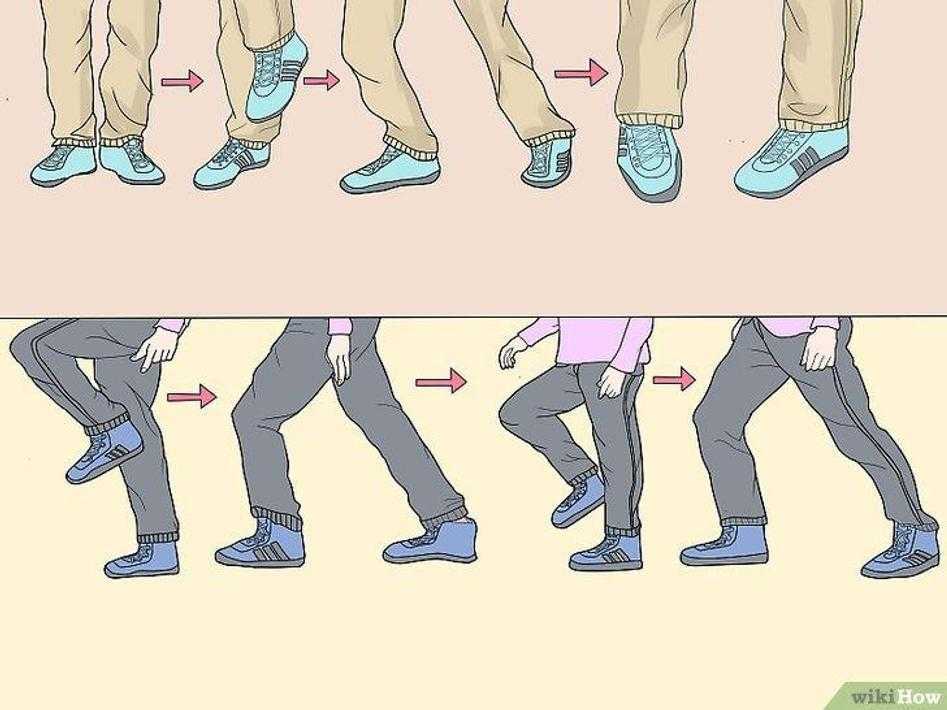

“Lil’ Buck: Real Swan” comes to the M.V. Film Center for one night, Saturday, March 20. It will also be online for a 24-hour period. This documentary by Louis Wallecan outlines the stunning form of dance called “jookin” that got its start among young Blacks in Memphis, Tenn. Jookin is the unique, fluid form of hip-hop street dancing that evolved from Gangsta Walk, and Charles (“Lil’ Buck”) Riley epitomizes its intricate footwork.

Open since 1981, the Crystal Palace was a roller-skating rink, now defunct, and once skating was over, it gave young Black men a chance to dance. Gangsta Walk became a way to get out anger and frustration without joining a gang, with the violence and drugs that way of life involved. Although it is a minor element in the film, a woman is shown jookin behind the Crystal Palace food counter where she worked, and Lil’ Buck first learned about jookin from his older sister. Jookin dancers worked to make enough money to go to the Crystal Palace. Once the Crystal Palace closed in 2017, its empty space became the biggest stage dancers could perform on. They also danced on concrete, more of a challenge.

Once the Crystal Palace closed in 2017, its empty space became the biggest stage dancers could perform on. They also danced on concrete, more of a challenge.

According to Lil’ Buck, the jookin culture was like a territorial war for young Black men. “It was like the wild, wild West,” he said. “Rather than be murderers, we’d just dance it out. Jookin kept us out of the street. It’s a lifestyle.” When DVDs of jookin by Daniel Price began to circulate, they gave jookin greater popularity, and Lil’ Buck, in particular, became seen as an incredible dancer.

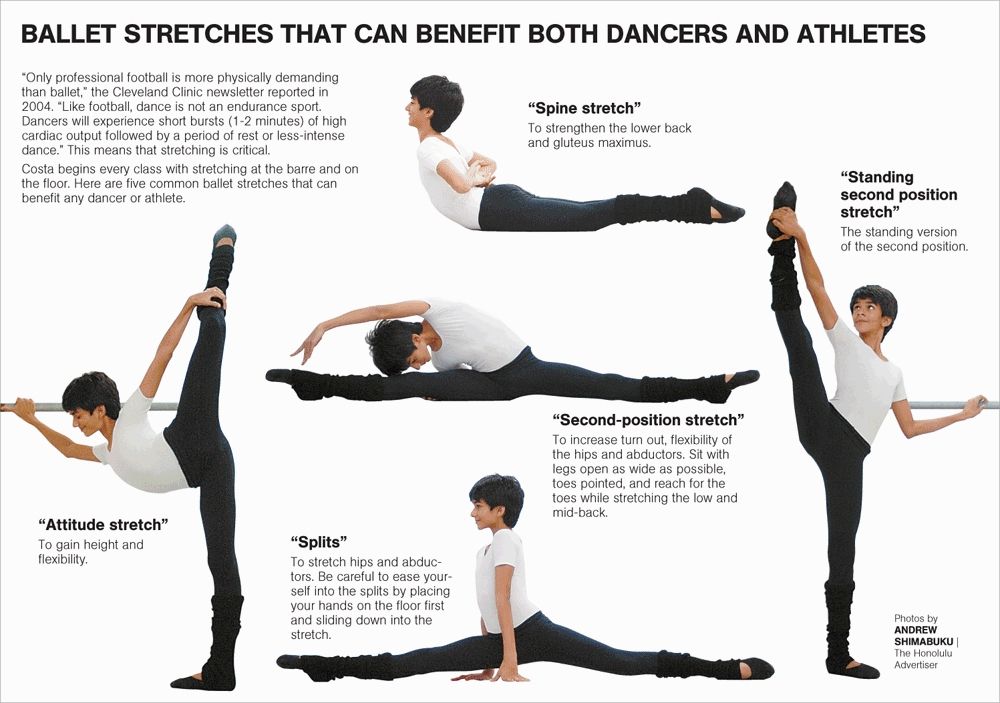

Lil Buck’s mother, Sabrina Moore, supported his dancing. “His tennis shoes would last one week,” she said. Concerned about the influence of gangs in the gang-infested Orange Mound neighborhood where Lil’ Buck was growing up, she enrolled her son in the performing arts school, Memphis New Ballet, where ability to pay was not an issue. While there, Lil’ Buck decided to add ballet to his jookin repertoire. “I wanted the discipline,” he said. Referring to his ballet instructor, he added, “Katie helped me understand dance, and opened my eyes to the world.”

Referring to his ballet instructor, he added, “Katie helped me understand dance, and opened my eyes to the world.”

An important aspect of jookin influenced by ballet was performing en pointe (on dancers’ toes), and Lil’ Buck learned how to improve his jookin toe dancing in sneakers from his ballet classes. Aiming for celebrity, he went to California. “I gave him the last money I had,” his mother said. “It paid for his flight out.”

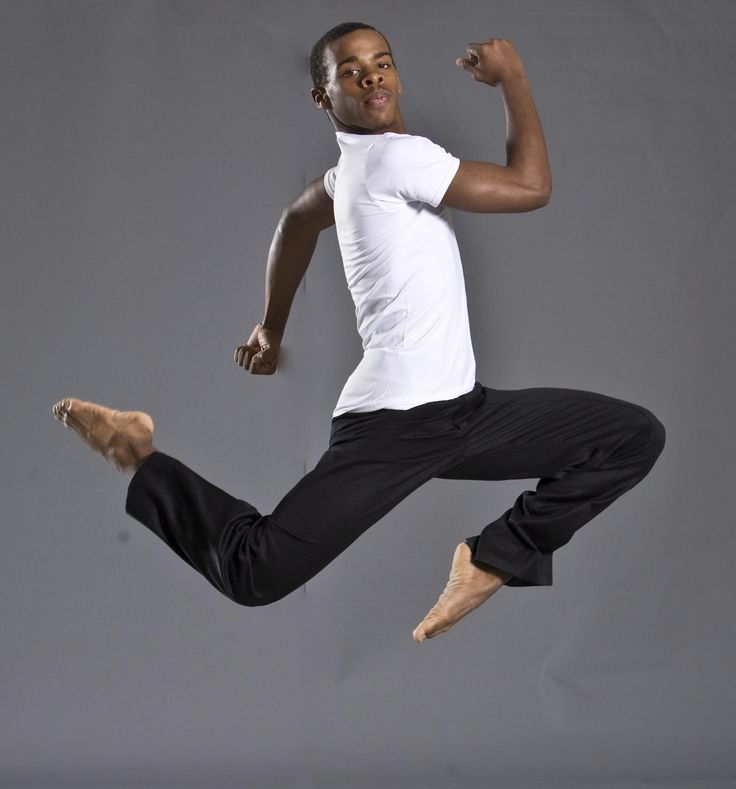

Buck’s fellow dancers became like family, and he collaborated with hip-hop performers in California. “We gotta show ’em our art,” he said. When choreographer Benjamin Millepied saw Lil’ Buck, he described him as a beautiful dancer, and encouraged him to dance barefoot: “Just to see his body in this pure form.”

Filmmaker Spike Jonze ended up making a video of Lil’ Buck performing Camille Saint-Saëns’ “The Swan” with Yo-Yo Ma on cello, and the video went viral. The “Lil’ Buck: Real Swan” film conveys the fluidity of Lil’ Buck’s movements and his remarkable capacity to interpret music through jookin. Lil’ Buck performed in Beijing with Ma, and later with the Fondation Louis Vuitton in an interpretation of Stravinsky’s “Petrushka” ballet.

Lil’ Buck performed in Beijing with Ma, and later with the Fondation Louis Vuitton in an interpretation of Stravinsky’s “Petrushka” ballet.

When Lil’ Buck returned to Memphis, he combined teaching and activism with performance in a rare combination of them. “Lil’ Buck: Real Swan” is worth viewing for the breathtaking artform that jookin is, and for an appreciation of an important aspect of Memphis culture.

Information and tickets for “Lil’ Buck: Real Swan,” both at the Film Center and virtually, are available at mvfilmsociety.com.

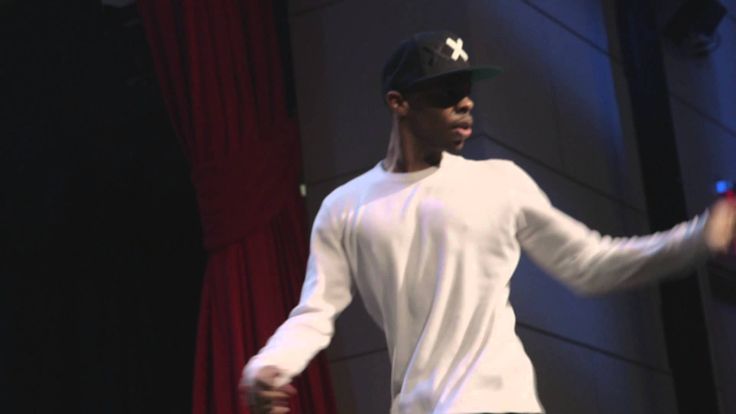

90,000 Krump - Dancing is the inside of the world

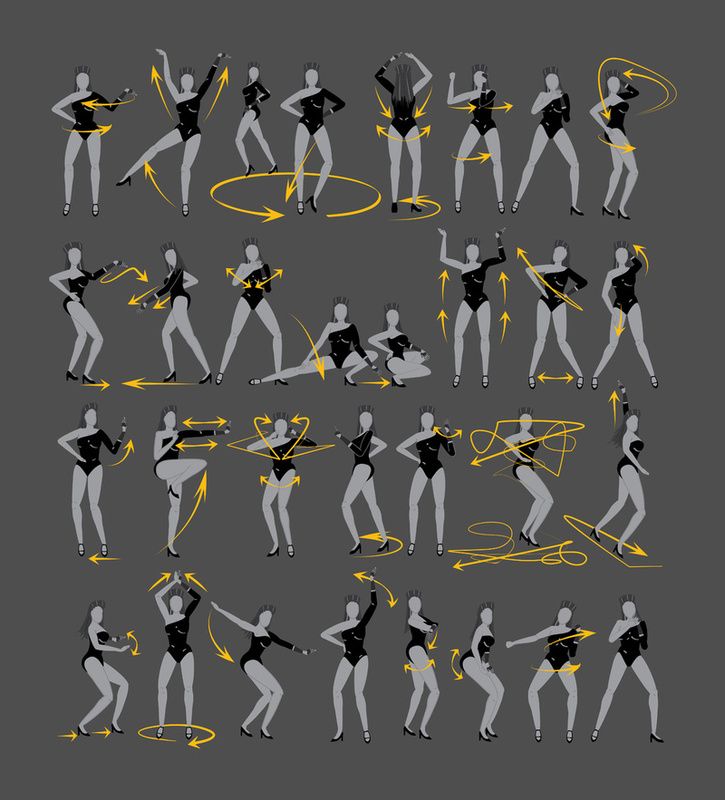

| KRUMP (OLD School) (Kramp ) - an abbreviated name, deciphered as: Kingdom Radically Uplifted Mighty Praise (Imperiya Absolute Forces). All those who were the founders of Krump are believers. In spirit, this dance is energetic and rather sharp, aggressive. The dancers are organized into groups known as families. This organization is similar to the group structure in Break dance . Each of the families is formed around the main dancer Big Homie, who acts as a dance instructor and as a spiritual teacher to others. The internal structure of the family has its own hierarchy. The level of the dancer in it is based on professionalism and respect from other krumpers. There are other "positions" in the family. The younger and inexperienced krump dancers are under the patronage of the elders. Experienced krumpers teach beginners and allow them to perform on their behalf in dance battles. For example, Lil' Homies often get the name of their Big Homie. Lil' Homies, who dance under the patronage of Tight Eyez, include jr. Eyez, Lil Eyez, Soulja Eyez, Young Eyez. Krump has the following titles: jr(junior), lil, young, boy, kid, baby, child, tiny, infant, twin, prince, Souljah, General. Some dancers move in the level immediately and get a higher status. The main thing is the basic movements, the fundamental foundations, without which no dance can do, including Krumping. How to take the first step towards professionalism? How to become a buck dancer and really enjoy what you do? Tight Eyez answers these questions in a series of tutorial videos. So: - Stomp (stump) . The first step to success is learning how to do the stomp movement correctly. Tight Eyez notes that everyone in the back family knows all about this basic move: “It's what turns you on, it's like the beginning of everything. Stomp is the first basic principle to be properly learned in dance. Everyone I teach Krumping starts with a stomp. To dance you need to know how to move your legs. Without this, you will stand like a donkey, and you will not be able to do anything. - Chest pop . This is the movement of the chest in different directions. But still, these are not simple chaotic body movements. Tight Eyes says, “Every Krump dancer initially has the problem of getting the chest pop right because it didn't fit into the rhythm. But it's not just the rhythm. The main thing is to catch the wave. To do this, you need to know where the movement comes from and where it is directed. If you just wave your shoulders like a chicken wings or a gypsy in the market, nothing will work. - Arm swing . Tight Eyez likens it to a fist that punches an imaginary opponent first in the upper body and then in the lower. Arm swing is used to show strength, power and to do the best possible in order to be respected. To become a true Krump master, you need to learn how to do basic chain movements. In addition, the movements must be done quickly and as clearly as possible, regardless of which one the dancer is going to perform. nine0015 Krump-up This is where Krump actually starts. Tight Eyez compares this movement to the operation of a car: “When you start your car, you put the key in the ignition, turn it, and your car is ready to go. Tricks lays the foundation that every dancer uses in the movement chain. The main thing in this technique is to work out the movements to automatism. It combines all the basic movements of Krump. But the peculiarity of dance tricks is simply to captivate others with the skill of performance. nine0016 Kill-offs (kill-offs ), a move that is used at the very end of your dance. Tight Eyez reflects on this: “We have dance sessions every day. And kill-off is not just a movement. I want people to come and see me some more. So I have to go all out and show class.” The manner in which Tight Eyez kill-offs is called heel-toe. His dancer performs with the help of heel movement. And Tight Eyez compares the entire kill-off sequence with the regulation of movement, by analogy with the wave of the traffic controller’s hand to the side, so he does arm swing at the end of his dance. nine0016 In total, there are currently three types of this dance: 1)Clowning is the initial stage. 2) Old School of Krump - stable fixed stage. 3) New Style of Krump - a new modified stage. |

The Art of Hearing Dance: Practices of Foreign Schools of Audio Description / Un Certain Regard

Listen to the publication Audio commentary: color photograph. The figure of a red-haired dancer frozen in a jump against the backdrop of the sea. She has lush red hair and a slender three-quarter body. The girl is wearing a short tight-fitting black top with a closed neck and bare shoulders, shorts and a long translucent black skirt fluttering in the wind. She lifts the edge of her skirt with straight outstretched arms. The dancer seems to be standing in the air on her left knee, her right leg is bent and raised high up. She tilted her head slightly and looked down. nine0016

The figure of a red-haired dancer frozen in a jump against the backdrop of the sea. She has lush red hair and a slender three-quarter body. The girl is wearing a short tight-fitting black top with a closed neck and bare shoulders, shorts and a long translucent black skirt fluttering in the wind. She lifts the edge of her skirt with straight outstretched arms. The dancer seems to be standing in the air on her left knee, her right leg is bent and raised high up. She tilted her head slightly and looked down. nine0016

"Dance is a poem, every movement in it is a word." This statement is attributed to the famous adventurer and dancer Margareta Gertrude Zella, whom the whole world knows under the name of Mata Hari. But the words of such a poem are not available to everyone. Already from the very definition of the word "dance" - the art of plastic and rhythmic movements of the body - it is obvious that vision plays a big role in its perception. What remains if you do not see the movements of the dancers? Music? Strained breathing? Rustle of clothes? The sound of footsteps? Can all this interest the viewer and give him pleasure? nine0016

Audio description (which in our country is called audio commentary) is a way to convey the beauty of dance to people who, for one reason or another, cannot see it. Joel Snyder, one of the leading experts in this field, calls audio description a form of literary work and likens it to a haiku. With just a few words, the audio descriptor creates a verbal copy of the visual image, translates the visible into the audible. Bright, figurative words draw vivid pictures before the mind's eye of the listener. nine0016

Joel Snyder, one of the leading experts in this field, calls audio description a form of literary work and likens it to a haiku. With just a few words, the audio descriptor creates a verbal copy of the visual image, translates the visible into the audible. Bright, figurative words draw vivid pictures before the mind's eye of the listener. nine0016

“Dance is not just movement,” says Iris Permuy Hercules de Solas, audio descriptor for dance TV shows on a Spanish TV channel. “Dance conveys feelings and moods. This is artistic art. The dancer draws pictures with his whole body, creates ephemeral masterpieces that the audio descriptor must have time to consider and describe.

“The entire visible universe is movement,” said dance teacher and theorist Rudolf von Laban. To describe this movement to someone who does not see it is not an easy task. However, it is quite doable. nine0016

Anne Hornsby, one of the UK's first audio descriptions, has described many theater productions, including the famous Mamma Mia! and Les Misérables, believes that special choreographic education is not required: “Only the usual skills of verbal description are needed. The ability to briefly, but figuratively express their thoughts; attentiveness and observation; the ability to convey the mood of the work; the ability to meet the allotted time - that's what really matters. At the same time, the soundscape and music cannot be drowned out – the viewer must hear their breathing.” nine0016

The ability to briefly, but figuratively express their thoughts; attentiveness and observation; the ability to convey the mood of the work; the ability to meet the allotted time - that's what really matters. At the same time, the soundscape and music cannot be drowned out – the viewer must hear their breathing.” nine0016

Do all dances need to be described? In the back of the hall, a barefoot girl is dancing a contemporary dance. She wears knee-high athletic trousers and a loose gray T-shirt. She stands on a straight right leg, the left straight leg is raised to the level of the waist and laid aside, the body is tilted to the opposite side, the right arm bent at the elbow is raised up, the left is wound behind the back. The operator shoots the girl's dance on a video camera. nine0016

If we are not talking about an independent dance performance, but about an episode of a play or a film, then, on the advice of the leading specialist in audio description of dance, the author of the Talking Dance manual, Louise Fryer, you need to ask yourself an important question: what role does this dance play? Is it necessary for the development of the plot? Perhaps he somehow reveals the character of the characters? Maybe he tells about the relationship between the heroes of the production? Do these relationships change after or even during the dance? Or does the dance simply fill in a pause in the play so that the actors can change for the next scene? Does dance contribute to creating a certain atmosphere? For example, it can immerse us in a historical era. nine0016

nine0016

During the same performance or film, we can see different types of dance that serve completely different purposes. The audio descriptor must understand the intent of the scriptwriter and director and, depending on this, choose a way to describe this or that dance. “The choreographer and director can help a lot by sharing their vision,” says Louise Fryer. “It’s also good to be present at the rehearsal.”

Photo: Tim Gouw

Tiflocommentary: coastline, cloudy sky and bright orange rays of the setting sun. Five girls dance on the platform, they run one after another in a circle: the left hand is raised up, the hand is turned with the palm to the sky, the right hand is bent at the elbow and directed forward with the palm away from you. All of them are in white corsets tightened on the back with thin straps. Four girls are wearing light long light skirts with a fluttering frill at the bottom, while the fifth girl is wearing a more fluffy light skirt with rows of frills along the entire length. She rises high from quick movements, under the skirt of the dancer there are light tights with lace. nine0016

She rises high from quick movements, under the skirt of the dancer there are light tights with lace. nine0016

Audio description is a kind of translation (intersemiotic or intersemiotic, according to the classification of R.O. Jacobson). As Bruce Metzger wrote: “Translation is the art of choosing the right thing to lose.” These words fully apply to the description of the dance. Depending on its goals and the plot of the work, sometimes you need to focus on the technique of the dancers, sometimes on the costumes, sometimes on the behavior of the characters during the dance, and in some cases it is enough just to say that the characters are dancing without going into details, so how they can distract from the development of the plot. nine0016

The well-known film translator Aleksey Kozulyaev repeatedly emphasizes that the audio descriptor is part of the "collective author" of an audiovisual work, and each addresses the viewer in his own language: the costumers - in the language of costumes, the composer - in the language of music, the actors - in the language of words, facial expressions and gestures, the director - in the language of images, etc. All together they create a single work. The task of the audio descriptor is to merge into the structure of this collective author so that his “language” organically fits into the general choir. nine0016

All together they create a single work. The task of the audio descriptor is to merge into the structure of this collective author so that his “language” organically fits into the general choir. nine0016

It must be remembered that a person comes to a performance or to a cinema in order to relax and have fun. Therefore, you can not overload the viewer with an abundance of details. An overly detailed description can be accurate, but it also confuses viewers and distracts from the plot.

Choice of word

The dancers themselves say that when you dance for real, you involuntarily discover that you don't have enough words, and there are not enough concepts in any language of the world to convey your feelings. Isadora Duncan, for example, said: "If you could explain something in words, there would be no point in dancing it." No wonder they say that dance is like love: this state can be felt, but it is very difficult to describe. nine0016

"You need to create verbal pictures of the dancers' movements," says Ann Hornsby, "but in a way that doesn't sound like a dry description of physical exercise.![]() " Iris Permuy Hercules de Solas adds: "It takes a rich vocabulary to describe it colorfully, gracefully, energetically, sadly, just like the dance itself."

" Iris Permuy Hercules de Solas adds: "It takes a rich vocabulary to describe it colorfully, gracefully, energetically, sadly, just like the dance itself."

Tiflocommentary: color photograph. Scene. The dancer in a black suit stands with his back to the audience, his right leg is set aside on his toe, his left hand is extended to the dancer, who is flying back in a jump with her arms spread apart. She looks at the dancer and smiles broadly. She is wearing a white suit: a tutu with a flat skirt, a leotard with thin straps with golden embroidery in the center, white leggings and pointe shoes. The dancers are watched by performers dressed as villagers. In the depths of the stage, in the blue twilight, there are scenery with buildings and the silhouette of a tilted ship. nine0016

The choice of the right word is the most important moment in the description of the dance, according to all experts. “For people who are far from choreography, the most terrible thing is the special terminology,” says Louise Fryer. - Knowledge of professional terms will not hurt. Describing, say, architecture, we want to show the difference between the Norman arch from the Gothic or the Ionic order from the Corinthian. By the same logic, it is important for us to know whether this ballet rotation is a pirouette or not. Of course, not everyone may know what a pirouette is (although there may be experts in the auditorium), however, if we use a special term, we thereby emphasize that it is ballet on stage, and not ballroom dancing. nine0016

- Knowledge of professional terms will not hurt. Describing, say, architecture, we want to show the difference between the Norman arch from the Gothic or the Ionic order from the Corinthian. By the same logic, it is important for us to know whether this ballet rotation is a pirouette or not. Of course, not everyone may know what a pirouette is (although there may be experts in the auditorium), however, if we use a special term, we thereby emphasize that it is ballet on stage, and not ballroom dancing. nine0016

Ann Hornsby stresses that the meaning of the terms must be clarified. Sometimes, when describing a ballet, it is useful to make an introduction before it begins and explain there what the words “pirouette”, “arabesque”, “fuete”, etc. mean.

Ann Hornsby explains: “The meanings of some words are clear without explanation. However, if possible, brief explanations do not hurt. But what you should not do is just list professional terms and dance moves. The viewer simply does not have time to comprehend all this in a short time. In addition, such a technical description will not say anything about the quality of the movement, its speed, the plot of the dance, the emotions of the hero and his motives. nine0016

In addition, such a technical description will not say anything about the quality of the movement, its speed, the plot of the dance, the emotions of the hero and his motives. nine0016

Laban's movement analysis

The well-known choreographer, dance theorist, teacher Rudolf von Laban developed a movement analysis system that is still used today. He discovered that any dance step exists in four dimensions, or factors: space, time, dynamics and flow. Therefore, the process of motion analysis begins with finding out the following main points: where the motion occurs; why the movement occurs; how the movement occurs; What are the traffic restrictions? All this will help the audio descriptor to find the right words. nine0016

It is relatively easy to describe a dance that has a story. However, as von Laban noted, “modern dance may lack a clear story. It is often impossible to convey the content of the dance in words, although the movements themselves can always be described.

He further explains: “An actress playing the part of Eve can pick the forbidden fruit in different ways, while her movements will express different emotions. She can seize the fruit greedily and quickly, or slowly and sensually. But when we describe movement as “greedy,” “sensual,” or “dispassionate,” we are not really talking about what we see. The viewer at this moment sees a fast and sharp or slow and sliding movement of the hand. And already the imagination interprets the actions of Eve as greedy or sensual. nine0016

She can seize the fruit greedily and quickly, or slowly and sensually. But when we describe movement as “greedy,” “sensual,” or “dispassionate,” we are not really talking about what we see. The viewer at this moment sees a fast and sharp or slow and sliding movement of the hand. And already the imagination interprets the actions of Eve as greedy or sensual. nine0016

Joel Snyder points out that von Laban is essentially referring to the fundamental principle of audio description: "Describe only what you see." “It's important to be precise,” Snyder explains, “but the description needs to be alive so that the listener paints the picture in their own mind. You need to be objective, using precise and figurative words, while avoiding interpretation. That is, our Eve “plucks an apple with a sharp, impetuous movement of her hand,” and not “with a mixed expression of greed and guilt on her face.”

Tiflocommentary: color photograph. Light walls, gray door, padlocked. To the left, a diagonal of a metal staircase with a railing rises up. Halfway up, a ballerina in a black leotard with lace-trimmed straps and a cutout at the chest. She stands on her right leg, with her right hand extended forward, holding on to the parapet, her left leg and left arm raised at an angle of 45 degrees and laid parallel back. The body is turned towards the viewer, the back is strongly concave. Her hair is pulled back into a bun, and on her feet are flesh-coloured pointe shoes. nine0016

Halfway up, a ballerina in a black leotard with lace-trimmed straps and a cutout at the chest. She stands on her right leg, with her right hand extended forward, holding on to the parapet, her left leg and left arm raised at an angle of 45 degrees and laid parallel back. The body is turned towards the viewer, the back is strongly concave. Her hair is pulled back into a bun, and on her feet are flesh-coloured pointe shoes. nine0016

Dance is the language of tradition

Description of traditional dances is a separate line of audio description. Dr. Doning Liang of the Hong Kong Audio Description Association has extensive experience in describing Chinese dances, in particular the famous Lion Dance. One of the difficulties is that completely different people will listen to the description: both those who are familiar with this dance and those who hear about it for the first time.

“I'm not just describing the dance,” says Doning, “I'm sort of acting as a teacher for blind people.

In addition, Krump is very diverse, as different people can use completely different styles from each other. The main thing is that Krump matches the character of the dancer and his attitude. Krump is a kind of alternative to street violence, which was very common in America at the end of the 20th century. Krump originated in South Los Angeles, a street dance style that jumped out of the dark corners of the ghetto and now makes bodies move around the world. We can say that krump is a stormy and hyper-speedy dance. The competitive structure of the Krump evolves along with the status and respect for the Krumping dancers and is called a "battle" (battle), just like in Break dance. If there is a massive krump-battle, then some American citizens may even call the police. Kramper dance is often confused with a real fight because it is so energetic. The word "krump" itself is often used to describe powerful and earth-shattering dance steps that sound like "KRUMP!" The uniqueness of krump lies in the nature of his movements - the krump dances jerky, moves quickly, often jumps, and comes into physical contact with partners in the dance "fight".

In addition, Krump is very diverse, as different people can use completely different styles from each other. The main thing is that Krump matches the character of the dancer and his attitude. Krump is a kind of alternative to street violence, which was very common in America at the end of the 20th century. Krump originated in South Los Angeles, a street dance style that jumped out of the dark corners of the ghetto and now makes bodies move around the world. We can say that krump is a stormy and hyper-speedy dance. The competitive structure of the Krump evolves along with the status and respect for the Krumping dancers and is called a "battle" (battle), just like in Break dance. If there is a massive krump-battle, then some American citizens may even call the police. Kramper dance is often confused with a real fight because it is so energetic. The word "krump" itself is often used to describe powerful and earth-shattering dance steps that sound like "KRUMP!" The uniqueness of krump lies in the nature of his movements - the krump dances jerky, moves quickly, often jumps, and comes into physical contact with partners in the dance "fight". nine0015

nine0015  Sometimes another person takes the place of the dancer when the latter leaves the family or loses a name in a dance battle. nine0016

Sometimes another person takes the place of the dancer when the latter leaves the family or loses a name in a dance battle. nine0016  ” There are several types of stomp. Some do it with both feet, some with one, it all depends on what the dancer is pursuing and what he wants to show. The most important thing is to feel what you are doing. Stomp is not just a stomp of the feet, as in the army, but also not a gentle fingering, like a girl on a first date. This is a whole art. In order to do it right, you need to be quite tough and strong person. Feel the dance floor, feel the touch of the shoe on the floor and understand that you have feet to dance with. nine0016

” There are several types of stomp. Some do it with both feet, some with one, it all depends on what the dancer is pursuing and what he wants to show. The most important thing is to feel what you are doing. Stomp is not just a stomp of the feet, as in the army, but also not a gentle fingering, like a girl on a first date. This is a whole art. In order to do it right, you need to be quite tough and strong person. Feel the dance floor, feel the touch of the shoe on the floor and understand that you have feet to dance with. nine0016  Just pulling your shoulders back is also not an option. It's like a sudden powerful explosion. You need to understand how to properly do a chest pop in order to come up with a stomp that usually comes with chest pop. Tight Eyez lists the main thing in this link: "Stomp turns you on, chest pop helps you move on and arm swing acts as the final explosion of the link." nine0016

Just pulling your shoulders back is also not an option. It's like a sudden powerful explosion. You need to understand how to properly do a chest pop in order to come up with a stomp that usually comes with chest pop. Tight Eyez lists the main thing in this link: "Stomp turns you on, chest pop helps you move on and arm swing acts as the final explosion of the link." nine0016  Same with Krump. The key is Stomp, the ignition is chest pop and arm swing, and ready to ride is krump-up. That's all science."

Same with Krump. The key is Stomp, the ignition is chest pop and arm swing, and ready to ride is krump-up. That's all science."  This is very important, because at the end of the session, people may be a little tired and only think about how to go home, get in, go fishing or do something else.

This is very important, because at the end of the session, people may be a little tired and only think about how to go home, get in, go fishing or do something else.