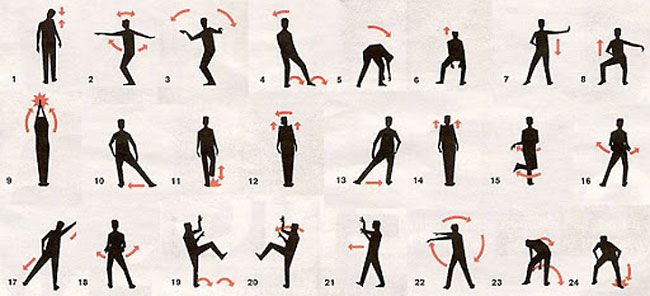

How to write dance steps

How to Write Choreography - Mandi's Lindy Hop Blog

I was lucky to have my very first choreography class with Eddie Jansson of the original Rhythm Hotshots. The class wasn’t just about learning choreography–it was about learning to write and memorize choreography. The method that he taught was excellent and I still use it to this day.

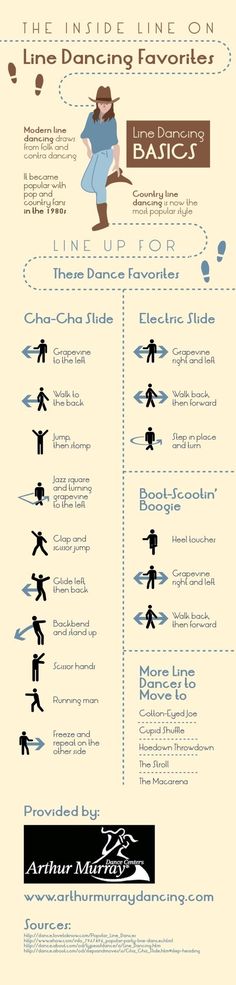

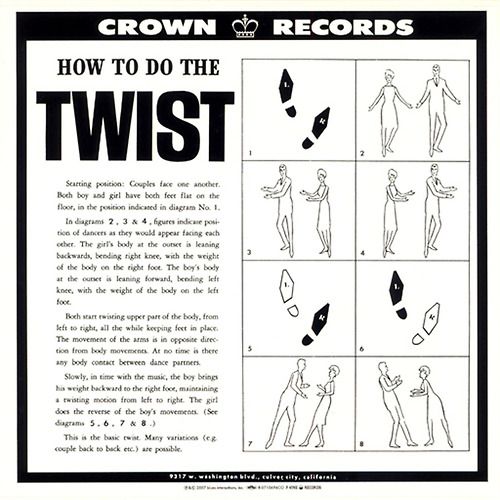

The first thing to do is to pick your music. Once you have the music, it’s time to chart it.

Sit down with a piece of lined paper and a pen and listen. Every time the music completes 8 counts, make a vertical mark along the lined paper. Leave some space before the next mark. When it’s the end of a phrase and a new phrase is beginning, move to the next line down.

Listen to the song twice to ensure that you’ve made the marks in the appropriate places.

Use the marks that you’ve made to create a chart. Each horizontal line should represent a phrase of the music.

A standard 32 beat phrase of music, which is made of four 8-counts, will have four rectangles on each line. A standard chorus would look like this:

After you’ve charted an entire standard song, if it had 4 chorus’ it might look like this:

Once you have your empty chart, it’s nice to listen again and make a little mark in places in the song where something interesting is taking place musically, such as a very punchy break, or an instrumental section.Now that you know the song and you have a nice visual representation of it, Then you can get started with your actual choreography.

Now that you know the song and you have a nice visual representation of it, you can get started with your actual choreography. It might make sense to start writing at the beginning, or it might make sense to create your most exciting sequences first, to match the highlights in the music.

Here are some examples of choreography that’s been charted.

This is what the first chorus of the Shim Sham would look like:

| Right Shim Sham | Left Shim Sham | Right Shim Sham | Shim Sham Break |

| Push, Push, Crossover Right | Push, Push, Crossover Left | Push, Push, Crossover Right | Double Cross Over |

| Tack Annie | Tack Annie | Tack Annie | Shim Sham Break |

| Half Break | Shim Sham Break | Half Break | Shim Sham Break |

Then for Chorus #2 – freezes in place of the Shim Sham breaks

| Right Shim Sham | Left Shim Sham | Right Shim Sham | FREEZE |

| Push, Push, Crossover Right | Push, Push, Crossover Left | Push, Push, Crossover Right | Double Cross Over |

| Tack Annie | Tack Annie | Tack Annie | FREEZE |

| Half Break | FREEZE | Half Break | FREEZE |

| Boogie Forward | Boogie Back | Boogie Forward | Boogie Back |

| Shorty George | Jump Boogie Back | Shorty George | Jump Boogie Back |

When you’re writing choreography that isn’t just made up of 8-counts (which is much more dynamic and interesting) you might make a chorus of the music look something like this:

In this example, I’ve broken up each phrase in smaller fractions to represent the 6-count moves vs. the 8-count moves.

the 8-count moves.

When Eddie first taught us to use this method, he had us chart out the first chorus of the song Leap Frog. This is a great, exciting song to use for your first stab at choreography. Then we worked in groups to choreograph that first chorus of music and performed for one another.

This is an example of a much more complicated, irregular choreography that I wrote many years ago. I still remember it because the song was so irregular and the visual stayed in my mind. This is for the song Hallelujah I Just Love Her So which is based on a blues structure but there are a mix of full 12-bar phrases and 8-bar phrases. This old choreography chart also shows how helpful it is to get a visual of the entire song so that you can know where you are within the larger piece of music.

Here’s our classic “Frankie Choreo” danced to Duke Ellington’s, Let’s Get Together:

And here it is in action!

Writing choreography doesn’t have to be difficult, and you have to start somewhere. Try this method to ensure that you’re basing the choreography on the music as the first priority. It’s a great learning experience. Oh, and as Eddie taught us, don’t forget to always take a bow at the end of your performance to thank the audience for gracing you with their attention! Good luck.

How I Write Down My Choreography – Dance Insight

This post may contain affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and make a purchase, we may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you. All affiliate links are marked with an asterisk.

Every choreographer has a different method for remembering what she taught her dancers. Some people keep it all in their head, many take a video at the end of every rehearsal, and some just ask the dancers to remind them, “how did that part go?”

It’s perfectly acceptable for a choreographer to forget her own choreography. It doesn’t mean she’s being lax or absent-minded, it just means that her focus is on making the dance look better. Unlike a performer who has to know every step by heart, a choreographer can stand at a distance and give critiques even if they don’t have every step memorized.

It doesn’t mean she’s being lax or absent-minded, it just means that her focus is on making the dance look better. Unlike a performer who has to know every step by heart, a choreographer can stand at a distance and give critiques even if they don’t have every step memorized.

In the end, it will always be up to the dancers to remember the steps and all the intricacies of energy and focus that the choreographer puts in place. But sometimes when you’re working in a less-than-professional setting, you can’t expect your dancers to remember every little detail. The best example is working with kids. They need constant re-teaching, and they need someone to do it with them (depending on the age) before they will be good on their own.

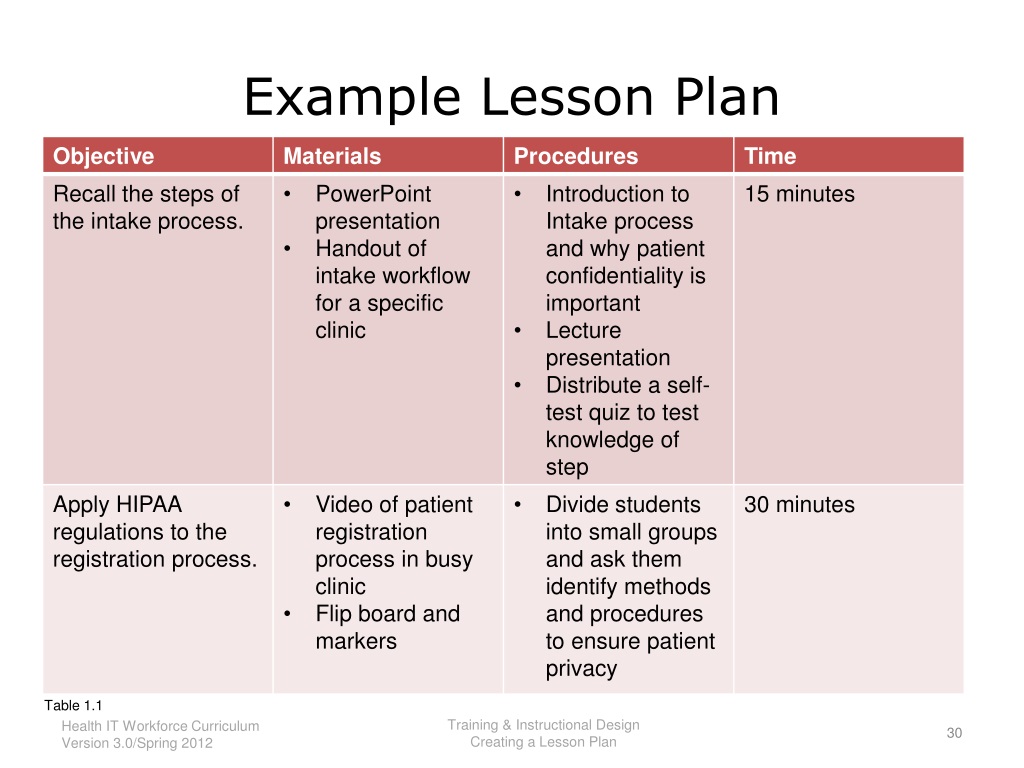

Nothing is more embarrassing than doing the dance with your kids and messing up the steps because you forgot. It’s happened to me many times and I always feel like an inadequate teacher. (Thankfully my kids have never laughed at me.) So I have developed an organized way of writing down choreography, which is helpful for several reasons:

- It makes lesson planning easier.

I can choreograph the whole dance at once, then just look back at my record as we learn week by week.

I can choreograph the whole dance at once, then just look back at my record as we learn week by week. - It’s easy to resolve disputes. If one kid thinks the pose is on count 5 and one thinks the pose is on count 4, you can say, “Let’s check the book,” and settle it right then and there.

- Video is complicated and prone to malfunction. I consider myself a tech-savvy person and I still always have trouble using video in class. The camera takes precious minutes to set up in the first place, and if you want to play the video next week in class, you need to bring extra equipment and, again, take up precious minutes getting everything ready. That’s a lot of trouble just to check what count the pose was on.

- You get a record for future use. You’ll end up choreographing in a lot of different contexts throughout your life, and sometimes repurposing something old is easier than coming up with something new. When I ran out of ideas for my beginner ballet class’s holiday dance, I recalled a little “Deck the Halls” number that I had done with a private school in a different city.

All I needed to do was pull up that choreography and rework it for different music and a slightly older class.

All I needed to do was pull up that choreography and rework it for different music and a slightly older class.

Whether you write down your choreography or not is entirely up to you and your teaching style. Note that this whole method assumes you do your choreography ahead of time, not in the moment during class. If you’re a come-up-with-it-on-the-spot person (more power to you because I find that impossible), I would not recommend taking time out of class to write it down! If you choreograph that way and really want a written record, I recommend taking a video and then notating based on the video after class. But whatever your style, if my method sounds like something worth pursuing, read on.

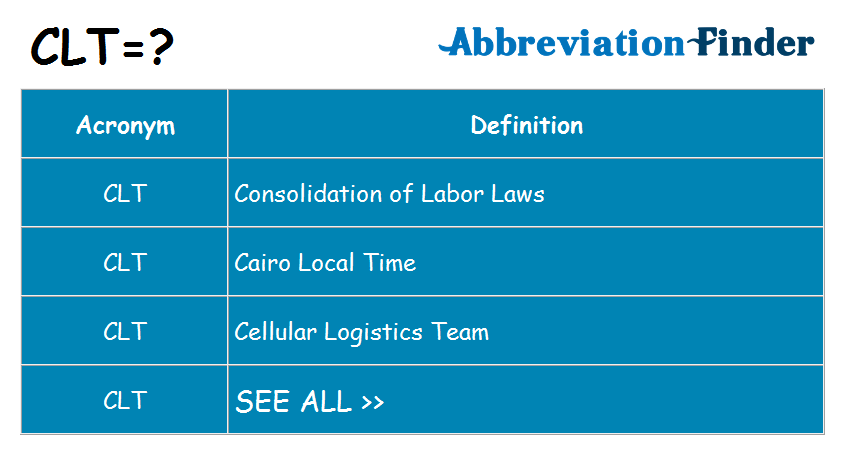

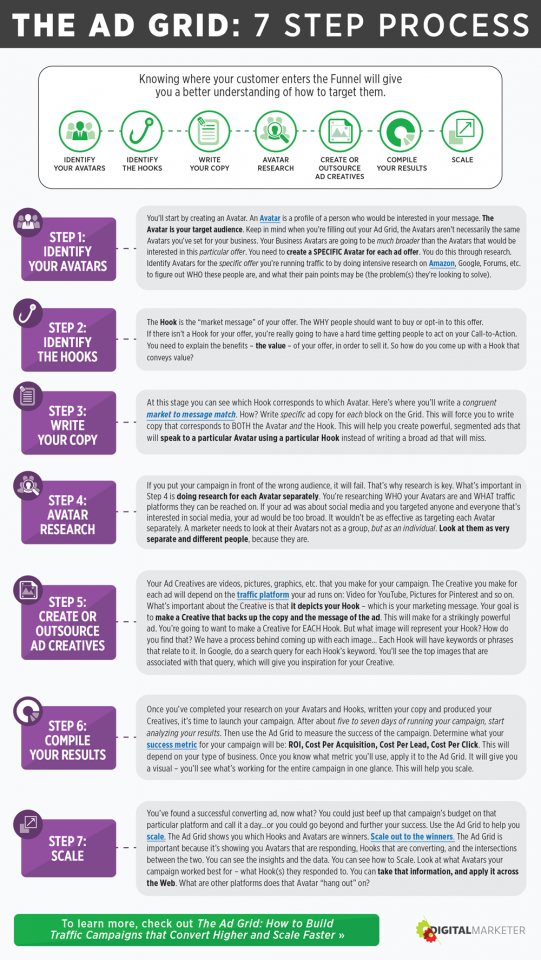

AbbreviationsThe key to writing down choreography without getting bogged down is to abbreviate as much as possible. I’ve developed a kind of shorthand to help me write complicated things quickly. Here’s a chart:

- SR – Stage right

- SL – Stage left

- US – Upstage

- DS – Downstage

- USL/USR – Upstage left/right

- DSL/DSR – Downstage left/right

- C2, C4, C6, C8 – Vaganova method “Corner 2,” “Corner 4,” etc.

- G1, G2, etc. – Group 1, Group 2, etc.

- L1, L2, etc. – Line 1, Line 2, etc.

- b/w – Between

- b4 – Before

- tog – Together

- w/ – With

- w/o – Without

- b/c – Ball Change

- 2 – To

- ct – Count

- || – Parallel

- PDB – Pas de bouree or port des bras depending on the context

- RDJ – rond de jambe

- EDH/EDD – en des hours/en des dans

- R arm/R leg – Right arm/right leg

- L arm / L leg – Left arm/left leg

- FSB – Front, side, back

- FL/BL – Front leg/back leg

- USL/DSL can also be used for “Upstage leg” and “Downstage leg”

So if I wrote “L1 go SR2SL, L2 go SL2SR,” you would know what I’m saying, right? Takes a lot less time than writing it all out!

Formations and GroupsThe first thing I do when choreographing a dance is give each dancer a single letter abbreviation. Use the first letter of their first name whenever possible, but if you have a duplicate, use a letter that will help you remember who it is. For example, let’s say you have an Abby and an Ashlin. If one of them has an unusual last initial like Y, you could have one be “A” and the other be “Y”. Alternatively, you could take a unique letter from the middle of their name. For Abby and Ashlin, I would either do B and A or A and S. You could also do Ab and As, but I like single letters because it gives my formations a clean, consistent look.

For example, let’s say you have an Abby and an Ashlin. If one of them has an unusual last initial like Y, you could have one be “A” and the other be “Y”. Alternatively, you could take a unique letter from the middle of their name. For Abby and Ashlin, I would either do B and A or A and S. You could also do Ab and As, but I like single letters because it gives my formations a clean, consistent look.

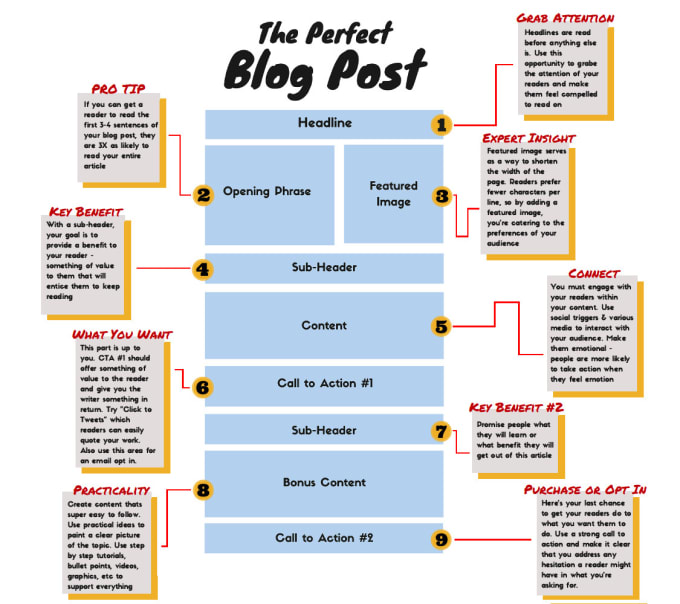

At the top of your page, write each dancer’s name and their abbreviation. Then listen to the music all the way through and note how many 8-counts are in each section. In the example shown, 8.5 means that there are 8 1/2 eight-counts in the chorus (68 counts total).

Throughout the piece, you will note whenever the dancers change formation. Sometimes you may need to include arrows if motion is involved. Be sure to also include which side is the audience, and keep it consistent. Your sketch of the formation is also the place to note groups, even if they don’t occur right away. Notice in the example that the cannon doesn’t occur until after the unison phrase, but instead of drawing the whole formation again, all I need to write is “Cannon SL2SR as indicated.” (Click the picture to enlarge and read my handwriting.)

Notice in the example that the cannon doesn’t occur until after the unison phrase, but instead of drawing the whole formation again, all I need to write is “Cannon SL2SR as indicated.” (Click the picture to enlarge and read my handwriting.)

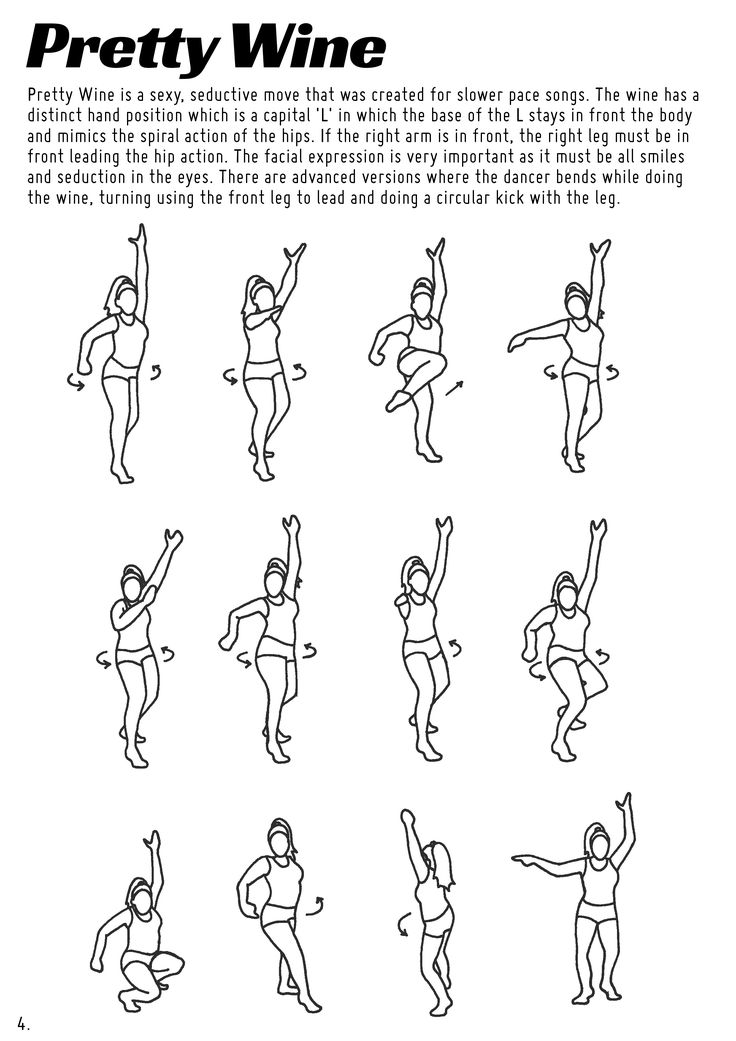

This is the part that no one in the history of dance has been able to figure out (And honestly, I haven’t really either). The history of dance notation is actually quite fascinating if you want to read more about it. The easiest dance form to notate is ballet, because there is a discreet number of positions and steps, each with a name. Begin fifth position croise facing corner 2, arms am bas. On count 1, tendu croise devant, right arm high, left arm al a seconde. As long as you know what method I’m teaching (Vaganova, otherwise you would be facing the other corner and the arms would be wrong), you know exactly what that means.

But what about modern, jazz, and other forms where sometimes movements don’t even have names? A typical modern teacher usually just yells out words like, “Head, roll, arm, leg!” The dancers might know what he’s talking about, but it won’t make much sense on paper.

I have only partially solved this problem by giving a name to everything I can. As long as you know what each name means, it will work for you. From my time as a show choir choreographer, I learned to be very specific about hand positions. There are only four options: Jazz hand, blades (fingers glued together), fists, and neutral (like blades but some space between the fingers).

Likewise, I gave names to a lot of common arm positions. “Suspenders” is when both hands are by the shoulders and the elbows are pointing out. You can be in “suspenders” with jazz hands, blades, fists, or neutral, and you can also be in “half suspenders,” where only one arm is in that position. I have a whole arsenal of made-up names, including “coffin,” “Captain America,” “tabletop,” “shampoo,” and “jungle.” Unique or even silly names work best because they help you remember what is what. Use words that work for you.

The point is to use as few words as possible. Use ballet terminology when applicable, even if you’re not doing ballet. (Just because you call it a “|| assemble” in your notes doesn’t mean you have to call it that when you’re teaching.) Ballet terminology is quite comprehensive for describing basic locomotor motions like jumping off one foot and landing on two (assemble), as well as positions relative to the audience like “croise.”

(Just because you call it a “|| assemble” in your notes doesn’t mean you have to call it that when you’re teaching.) Ballet terminology is quite comprehensive for describing basic locomotor motions like jumping off one foot and landing on two (assemble), as well as positions relative to the audience like “croise.”

Notice in the example above that I use commas to separate individual movements. At the end of the second line, I write “step R to half lunge hands to knee,” followed by a comma and a superscript 5 6. That means that you step to a lunge and move your hands to your knee at the same time, taking two counts, 5 6. If there had been a comma after “step R to half lunge,” then you would know that the hands don’t move until after you’ve lunged. Everything between a set of commas happens at the same time.

Occasionally it will make more sense to notate movements by the lyrics rather than the counts. I will write the lyrics above the steps they happen on, hyphenating syllables when necessary.

You never want to write more words than you have to, and an easy way to cut down on words is to not write out repeats. If a repeat happens right then and there, I’ll use square brackets, like this:

[Tendu, close, tendu, close, degage, pique, pique, close plie] en crois

[pdb R, pdb L, single pirouette edh, step R L] 3x

Other times, you have to go back to an earlier part of the dance. I’ve shown a simple example here. Notate your starting and ending points with letters, then all you have to do is write “Repeat A to B.”

Those are the basics of my choreography notation system. Keep in mind, this isn’t supposed to be a universal system that everyone understands (wouldn’t it be nice if we could write down choreography like we can for music?). It’s supposed to be a personalized method for you to write down your creation, then come back to it years later and still understand it.

I hope you’re able to adapt my method to your needs and start preserving your choreography in a tangible form! If you want more details or have specific questions, let me know in the comments!

Here is the full page for easy reference: (This is not a real dance, by the way. It was created for the purposes of this blog post. The song lyrics are also fictional.)

It was created for the purposes of this blog post. The song lyrics are also fictional.)

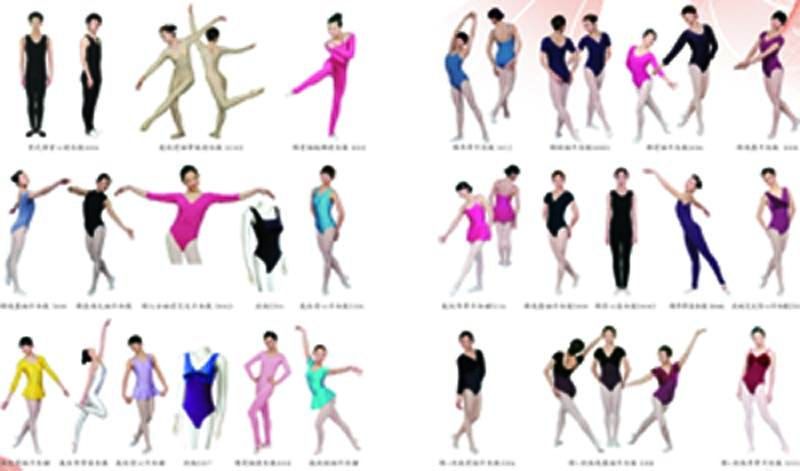

A small educational program on dance terms.: v_mire_tanca — LiveJournal

What does Amor do at night in a nervous state instead of a kin and a bed? Right: he watches his own videos to send to another contest (a nightmare, they are all terrible!) and reads a new edition of his article about michaeltans.

That's what I actually am. I decided, before I forgot on the go, to write a small educational program on dance terms. Because this is what you stumble upon everywhere, but I will clarify what people usually do not know, not because of illiteracy, but because of the specifics.

1. The word "dancer", if you are talking about a professional, is unacceptable. This is an outdated word that has now migrated a little into modern culture. For example, "disco dancer" came into use. This is also a controversial form, but still it is more or less closer to the meaning. Since in a professional environment this can be called a dancer at a folk festival, a disco is also a kind of folk festival.

Since in a professional environment this can be called a dancer at a folk festival, a disco is also a kind of folk festival.

In general, if you say "dancer" in a strict academic environment, they will simply kill you. :) Only "DANCER", "BALLET ARTIST". There is no third. A dancer is a bad word in a professional environment, like the word "dancer", it is perceived as an insult. Yes, and you can only "dance" folk dances at the festivities. If we are talking about a profession, then only "dance".

This may be the question: Michael Jackson can be a dancer? Well, in the old days, even in a nightmare, I would not have dreamed such a word in such a context. Doubtful. A dancer in any way is just a person who somehow knows how to dance, vernacular. A high-class professional is a dancer.

You are not talking about the ballerina "dancer" (such a word was somewhere in the "Queen of Spades", yes). It's the same with a man.

In flamenco and Spanish dance, two variants of the word dancer are accepted, by the way: "baylarin" and "baylaor". So the first is related to academicism and is closer to the concept of "ballet dancer". The second - to pure flamenco, as a folk dance.

So the first is related to academicism and is closer to the concept of "ballet dancer". The second - to pure flamenco, as a folk dance.

There is such a word "ballerun" among the people. :))) But in terms it is not. But I’ll add an interesting fact about the ballerina. Now this is the name of any dancer in classical ballet. But in the old days, in the same era of Anna Pavlova, only a well-deserved dancer with a certain class of parts and salary had the right to be called a "ballerina", this was a title. Although at the same time the artist could dance the supporting parties, not only the main ones. A simple corps de ballet dancer was not a ballerina. In Italy, there was the concept of "prima ballerina assolute" - a soloist who always performed only the first parts.

Now, of course, all that has lost its meaning.

2. The word "pa" is a French ballet term, it means "step", "foot movement", "jump", for example, "pas de bure" (step with legs crossed), "pas de basque" - " Basque step, jump from foot to foot. Pas can sometimes be such a concept as a certain dance number: "pas de deux" - a composition of dances for two (adagio, two solo variations and coda), "pas de trois" - a dance for three, "pas de quatre" - a choreographic composition from dances for four.

Pas can sometimes be such a concept as a certain dance number: "pas de deux" - a composition of dances for two (adagio, two solo variations and coda), "pas de trois" - a dance for three, "pas de quatre" - a choreographic composition from dances for four.

So, not every movement can be called "pa". If we are talking about someone waving their arms, lifting up their skirt or jerking their ass, then this is not "pa" at all. :)

In Spanish dances there is a similar word of the same root: paso, meaning "step", "move".

3. In flamenco now, wherever you spit, they write "flamenco styles". What styles? This is a terrible tracing paper from Spanish, where there is such an expression as "estilo flamenco" as a synonym for the word "palo" (literally "branch") - a song and dance form or genre. But speaking Russian "style" in this context sounds ridiculous. Style is, for example, all flamenco, baroque, jazz, gothic, oriental style, fashion style, etc. But solea, sevillana or alegrias is different in Russian in meaning. You don't talk about waltz, polka or minuet - "style". Is it possible to say "in the style of the minuet", but not "style of the Minuet". Rather, "minuet dance", "genre". And allegrias with sevillana are genres of music and dance, forms. But not "styles" - what a horror. :)))

You don't talk about waltz, polka or minuet - "style". Is it possible to say "in the style of the minuet", but not "style of the Minuet". Rather, "minuet dance", "genre". And allegrias with sevillana are genres of music and dance, forms. But not "styles" - what a horror. :)))

This is what I have been wanting to say for a long time, since I come across it regularly. For example, the word "dancer" has now entered the environment of the new generation of professionals, who have no education and upbringing, to such an extent, what a horror. You look at the site of a dance studio or some site for dance lovers, and there is a "dancer" everywhere. People write letters in the mail: "can you tell me some dancer who teaches this?" Darkness and horror. As a child, I would have been hit on the head for this even in a choreography circle.

4. Actually "choreography". You often hear this word in relation to the situation when it comes to learning the basics of classical dance. For example, people go to Irish dances or flamenco in the studio and say: "Besides flamenco, we also do choreography. " You see, it's like saying "besides dancing, we also do dancing." :))) Choreography is a dance art of any kind, from folklore to jazz. And what has stuck to us through the habit of calling children's circles with a classical approach "choreography" is wrong. If this is a form of training, it is called "classical exercise", if this direction is "classical dance", if it is a base - "basics of classical dance" or "classics".

" You see, it's like saying "besides dancing, we also do dancing." :))) Choreography is a dance art of any kind, from folklore to jazz. And what has stuck to us through the habit of calling children's circles with a classical approach "choreography" is wrong. If this is a form of training, it is called "classical exercise", if this direction is "classical dance", if it is a base - "basics of classical dance" or "classics".

Vot. If I remember something, I'll write more, well, and if you yourself remember something that raises questions - ask. :)

Choreographic text - as the main component in the dance composition

Murzabaeva, G. I. Choreographic text as the main component in dance composition / G. I. Murzabaeva. - Text: direct // Young scientist. - 2015. - No. 8.2 (88.2). - S. 39-40. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/88/17468/ (date of access: 12/13/2022).

Reality in a figuratively generalized vision is reflected by all types of art, and each of them has its own expressive means. Expressive means of choreography are: movements of arms, legs, head, body, i.e. dance vocabulary, language. Expressive means also include facial expressions, gestures that are fixed in dance poses [1].

Expressive means of choreography are: movements of arms, legs, head, body, i.e. dance vocabulary, language. Expressive means also include facial expressions, gestures that are fixed in dance poses [1].

Dance movements are the basis of choreographic movement. The origin of the dance movement began from ancient times of human existence [2].

"Choreographic vocabulary - separate pas movements and poses that make up the dance as an artistic whole, i.e. as a work of choreographic art movement. Choreographic vocabulary arises on the basis of communication of expressive movements of a person, over the centuries it has been accumulated, improved and polished. By themselves, the elements of choreographic vocabulary are not carriers of a certain figurative content, but they have a range of expressive possibilities that are realized in the specific context of the dance as a whole and the relationship of the elements of choreographic vocabulary develops a choreographic text.

The development of dance and its design was influenced by the living conditions of the people, their occupations, climate, etc. The dance language has absorbed the character of the people, their temperament, as well as their way of life, their social system.

The dance language has absorbed the character of the people, their temperament, as well as their way of life, their social system.

Each movement consists of several parts:

- Starting position

- Zatakt

- Main element (reveals the idea of this combination)

- Passing (connecting)

- Climax (fixation, posture, ending, point in motion)

To create a dance language, to reveal artistic qualities, the combination of movements of arms, legs, and head is of no small importance. Separate dance movements are combined in various combinations, each type of choreographic art has its own dance language. The mixing of the dance language leads to a loss of purity, to a violation of the integrity of the choreographic work. There are: imitative, figurative, national dance languages.

When compiling a choreographic text, the close relationship between the idea and drama of the dance, musical material, national features of the dance, the nature of the images, the pattern of the dance with the dance vocabulary are taken into account.

The movement in the dance has a specific duration in time, combined with pauses. First of all, it is necessary to show not the internal logic of building a movement, which makes it possible to convey certain emotions.

The second feature of the emotional movement is naturalness, immediacy. Fokine said: “Every movement in artistic dance is an improved development of natural movement in accordance with the character that this dance should reveal, not one deviation from natural movement should not be unjustified. The dancer rises on her fingers, whether she takes off into the air, whether she taps her heels on the floor, all this is not a distortion, but the development of a natural movement. The combination of technical movements with the image of dance is an important point in compiling a dance language. The director should not avoid complex movements if they help the development of images, but also overload the text with "tricks" for the sake of "beauty or show the performer's capabilities. "

"

Currently, the scope of choreographic works has expanded greatly, and this sets new requirements for the choreographer. It is required not only means of expression, but also to create its new forms.

“Guided by subtle intelligibility, the ballet creator can take from them as much as he wants to determine the character of his dancing heroes. It goes without saying that he who seizes the first element in them can develop it and fly higher than his original, like a musical genius, from a simple song heard on the street, creates a whole poem, at least then there will be more sense in dancing, and, thus, this light, airy and fiery language can be more figuratively depicted before the village is still somewhat constrained. N.V. Gogol.

Music in a choreographic work.

1. Musical material is an important basis in the work of a choreographer in creating a choreographic work.

- The principle of selecting a piece of music for the implementation of a choreographic production.

- Creation of a choreographic composition based on musical material. Unity of idea, theme, music in a choreographic work.

When staging a dance, dance numbers, the question arises about the relationship between choreography and music. Their conformity - the expression of one another - is one of the general crisis criteria for the artistry of dance art. Dance does not produce music, but exists on the basis of music and is performed with music, but music itself cannot be danced. Dance does not exist outside of music.

The meaning of the expression "Music in dance" firstly: in accordance with the choreography and image of music, this refers to the general nature of the construction, but also to complex images; secondly: in accordance with the tempo, rhythm, i.e. in harmony with the tempo and character of the music.

J. Noverre “Letters on dances and ballet”: “Good music should paint, should speak. Responding to her, the dance becomes, as it were, an echo, obediently repeating after her everything that she says.

In dance, it is not necessary to beat each rhythmic beat, sometimes the dance movements may not correspond to each beat of the measure, but the discrepancy between music and dance is not conceivable both in general and in phrases.

If the images match, then the choreographer has correctly understood the piece of music. This means that he managed to reveal the image laid down by the music with dance movements. The choreographer builds works based on the idea. The choreographer often meets with a finished piece of music, either a composition by the composer on the instructions of the choreographer or a libretto [3].

When a composer composes music according to the playwright's idea, the choreographer creates a composition plan.

In a piece of music, the choreographer finds material for the national features of the hero and intonation to characterize the era, and reflects all this in his work.

When selecting music for a dance, several methods can be used:

1. Arrangement method.

Arrangement method.

2. Fragmentation method.

3. Work with the work program.

4. Ordering music for an amateur or professional composer.

Requirements for musical material:

1. Danceability.

2. Imagery.

3. The logical construction of music.

4. Musical-rhythmic completeness.

5. Single style of music.

Conclusion: both music and dance carry a figurative thought. Both of these arts are not concrete, but associated.

Both dance and music are fed from the same “plate”, i.e. everything comes from life.

For choreography, it is important not only how the choreographer choreographs, but also in the name of what he choreographs. Only in this case, the expressive means of music and dance will help create figurative and semantic actions, while musical forms may be different.

Literature:

1. Slonimsky Yu. "Seven ballet stories", 1967, L.

- "Dramaturgy of the ballet theater of the 19th century", 1977, M.