How to write about dance

Writing about Dance

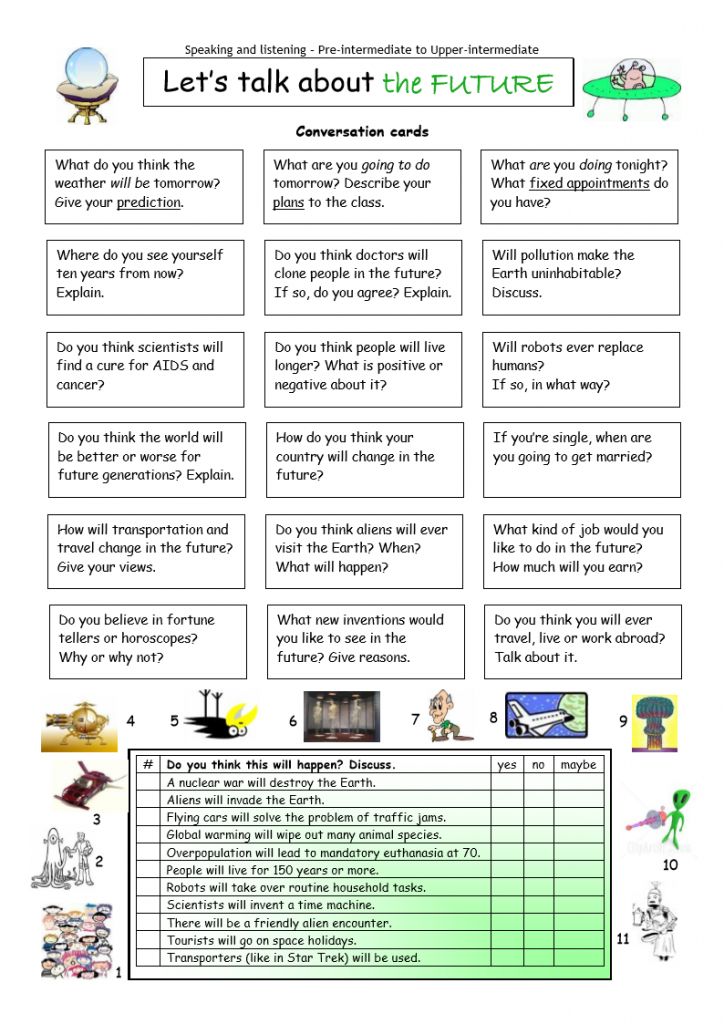

Writing about Dance Most cultivated people are able to respond sensitively to and can discuss in a reasonably informed manner most or at least some of the fine arts. Yet when it comes to dance (Redfern, 1975) they seem totally lost. Two traditions have had something to do with this unusual state of affairs. In the remarks that follow, I discuss these traditions briefly, offer an introduction to dance (with an emphasis on modern dance), and provide a few hints on writing about dance.1. Dance Criticism

We notice that the tradition of dance criticism is weaker than those of such fine arts as art and drama. Few writers in the field of dance have produced the "evocative criticism" we expect from writers like Donald Tovey (d. 1940) or Bernard Berenson (d. 1959) or F.R. Leavis (d. 1976), that is, criticism which catches and conveys something of the flavor of the work and is itself a work of art in its own right. In this regard, it was Clive Barnes, the New York based critic, who set the standard during the late 1960's and the early 1970's. Today, we look to Anna Kisselgoff, who writes for The New York Times, and Robert Everett-Green, who writes for the Globe and Mail.

Until recently (of course) the materials for appreciating dance have not been not available in an easily accessible form. The proliferation of films and video-tapes devoted to dance, not to mention televised performances, make a difference here.

2. Education Policies

In the past, the educational policies of high schools and universities have concentrated on the study of masterpieces in art, literature, drama, and music. Today, the notion of a "cannon" is itself suspect.

However, the proliferation of dance programs of the past three decades, together with the increasing availability of dances, on film and on tape, for example, has fostered the serious study of dance. These programs have shifted their emphasis slightly; instead of concentrating on performing work, they also encourage the practice of evaluating works. Most directors (of dance programs) strive to establish a balance between performance and appreciation: they believe that the one enriches the other. After all, the sort of appreciation that is possible during the dancer's performance is quite different from the appreciation that is possible for the spectator. Obviously, dancers cannot be aware of the work as a whole. For example, they cannot see what takes place behind their back.

Most directors (of dance programs) strive to establish a balance between performance and appreciation: they believe that the one enriches the other. After all, the sort of appreciation that is possible during the dancer's performance is quite different from the appreciation that is possible for the spectator. Obviously, dancers cannot be aware of the work as a whole. For example, they cannot see what takes place behind their back.

Many people think of dance as human communication at its most basic level. Some form of dance can be found in every culture, regardless of its location or stage of development. It is easy to see that dance is a natural, universal human activity. Scholars tell us that dance sprang from religious needs; they say that the theater of ancient Greece developed out of that society's religious, tribal dance rituals. How is dance unique?

- For one thing, dance focuses on the human form, i.e., human bodies moving through time and space, shaping space as it were, reminding us of kinetic sculpture (Martin and Jacobus, 1997, p.

296).

296). - As well, abstract dance especially calls attention to visual patterns, reminding us of abstract painting.

- We also notice that dance calls attention to narrative, reminding us of drama.

- By the same token, we notice that dance is intensely rhythmic, unfolding in time, reminding us of music.

Normally, music accompanies dance; now and then, however, dance makes up part of opera.

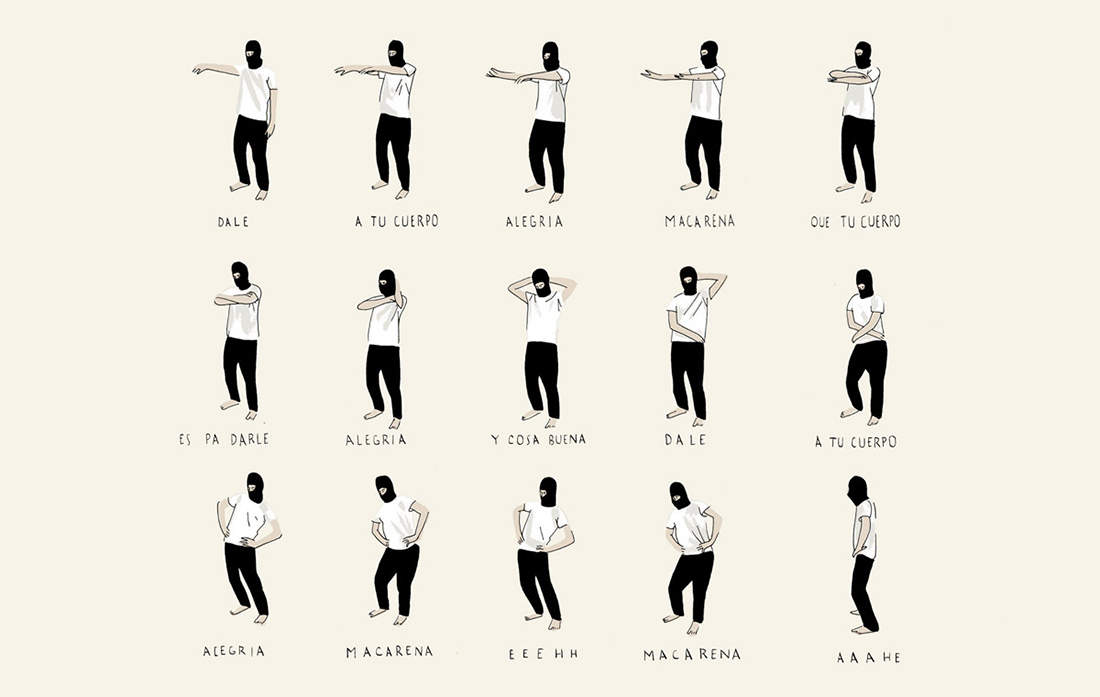

Basic Movements

Modern dance (the focus of my remarks here) utilizes four basic movements or activities: bend, stretch, twist, and rotate. To add weight, dancers accentuate movements in terms of space and time. To add color and texture, dancers accentuate movements in terms of ebb and flow. Via these movements, then, dances suggest mind, feelings (emotion), and body.

Subject Matter

Dance is an art of time and space. It utilizes many of the elements that can be found in other arts.

- Dance takes as its subject matter abstract motion, i.

e., shapes and patterns.

e., shapes and patterns. - As well, dance takes as a pervasive subject matter feelings: you might say that this is what dance is all about. The body exhibits feelings less abstractedly than music, i.e., the feelings are "embodied."

Our ability to identify with other human bodies is very strong; the dancer exhibits feelings and we in turn experience those feelings. The choreographer--who creates the dance--interprets the feelings for us. In this way, we understand these feelings--and ourselves--with greater insight.

- Dance also explores states of mind. Feelings, such as pleasure and pain, are relatively transient; however, states of mind, such as attitudes, tendencies that engender feelings, endure for a longer period of time. For example, jealousy involves a strong feeling, which can be described as passion (p. 297).

The serial structure of the dance provides just the vehicle needed to interpret these enduring states of mind. What is revealed is not so much why things happen as the inner reactions to the happening (p.

298).

298). - Narrative provides a subject matter for many dances. We think of Robert Helpmann's ballet, Hamlet, which takes Shakespeare's play as its subject matter. It interprets the inner life of a tragic drama.

Form

Dance takes as its subject matter moving visual patterns, feelings, states of mind, and narrative, in various combinations. The form of the dance, the details and the parts as they work together to organize the structure, gives us insight into the subject matter. However, the details, the parts, and the structure are not as easily perceived as they are in painting, sculpture, or architecture, because the dance "moves on" relentlessly through time (pp. 298-99).

To enjoy the dance, we have to develop a memory of those movements. We do this by noticing the repetitive movement and the variations on those movements. We notice how the dance builds tension--by withholding movements we think should be repeated. Thus, repetition or the lack of it serves as an important "shaping" feature of the dance (p. 299).

299).

We can identify a number of formal qualities:

1. repetition

The repetition of movements might be patterned on the repetition in the music. The musical structure of A-B-A is common. Often, the movements performed at the beginning are developed, enlarged, and modified in a later section, and then are repeated at the end, so as to help the viewer understand the full significance of the development.

2. balance

Choreographers employ a number of techniques to give their dances balance. First, the dancers balance themselves across the space allotted to them. Second, they might give the dance centrality of focus, so that we see an overall shape. Third, the most important dancers take up center stage. Thus, we detect balance in terms of the relationship between the main dancers and the subordinate dancers and between individual dancers and the group.

Appreciating dance involves developing an eye for the ways these movements combine to create individual works. Modern dance develops a slightly different vocabulary.

Modern dance develops a slightly different vocabulary.

The origins of modern dance can be traced to Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, who rejected the stylization of ballet, with ballerinas dancing on their toes and executing the same basic movements in very performance (pp. 311-12).

Duncan preferred natural movement; she danced bare footed, wearing gossamer drapery that showed her body and legs in motion. Also, she insisted on placing the center of motion just bellow the breastbone--the solar plexus. In this way, Duncan (d. 1927) and her followers infused a new energy into the dance. She based her dances on abstract subject-matter, especially states of mind and moods, and expressed her understanding of them via her movements. Her works tended to be lyrical, personal, and (often) extemporaneous. Her movements tended to be on-going; they rarely came to a complete rest (pp. 312-13).

Martha Graham, Erick Hawkins, Jose Limon, Doris Humphrey, and other innovators who followed developed modern dance in a variety of directions. For example, Graham created dances on themes of Greek tragedies, such as Medea (p. 313).

For example, Graham created dances on themes of Greek tragedies, such as Medea (p. 313).

Martha Graham

Graham (d. 1991) studied with Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn (at the Denishawn School), who pioneered instruction in Oriental and primitive techniques. It soon became clear that classical ballet was not for Graham; she preferred the uncharted terrain of human passions as translated into angular movements, flexed (not pointed) feet, and rhythmic "contraction and release" breathing. Graham became a virtuoso dancer.

In 1926, she organized her own company and school (in New York), where she developed the "Graham technique," which is reminiscent of ballet in its rigor and discipline. Graham's contraction is a common movement: this is the sudden contraction of the diaphragm with the resultant relaxation of the body. This movement builds on Duncan's emphasis on the solar plexus, but adds to that emphasis the systolic and diastolic rhythms of heartbeat and pulse (pp. 316-17).

316-17).

At times, Graham's dances have been very literal, with narrative pretexts (as in ballet). In Night Journey, she interprets Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, the dance accentuating the emotional links between Jocasta and her son-husband Oedipus (p. 317).

Life magazine selected (in 1991) Graham as one of the 100 most important Americans of the 20th century.

Graham performed until she was 76. To many, she has made the greatest contribution to modern dance. Graham has been compared her to Picasso and Stravinsky. She created 181 dance altogether, ranging from Greek dances to collaborations with composers, e.g., Copland and Stravinsky. Most of the major choreographers in the USA have studied the Graham technique, including Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, and Twyla Tharp. Many actors have studied this technique too: Kirk Douglas, Gregory Peck, Eli Wallack, Joanne Woodward, Diane Keaton, and Woody Allen. In an interview (1985), she said:

I believe that dance was the first art. A philosopher has said that dance and architecture were the first two arts. I believe dance was the first because it's gesture, it's communication. That doesn't mean it's telling a story; it means it's communicating a feeling, a sensation to people.

I believe that dance was the first art. A philosopher has said that dance and architecture were the first two arts. I believe dance was the first because it's gesture, it's communication. That doesn't mean it's telling a story; it means it's communicating a feeling, a sensation to people.Twyla Tharp

Tharp has developed a style pleasing to serious critics and dance amateurs, including a playfulness that seems appropriately modern. She has taken advantage of the new opportunities for showcasing dance on television, e.g., the Dance in America series. She has been particularly successful in adapting jazz of the 1920's and the 1930's to dance, e. g., "Sue's Leg" (1976), which features the music of "Fats" Waller (p. 321).

g., "Sue's Leg" (1976), which features the music of "Fats" Waller (p. 321).

In writing about dance, we share our insight into the artfulness of a work; our task is to identify the artistic qualities which make up the work in question. This means helping readers perceive the form of the work, and thereby appreciate its content. Much more is required than such expressions of personal taste as: "I don't know anything about dance, but I liked it" or "I didn't like it."

Of course, the ephemerality of dance makes reviewing three-dimensional moving images exceptionally difficult.

- A rather good place to start is to consider the title, as a device for directing or mis-directing the attention of the audience.

For example, Kurt Jooss's The Green Table features a Dance of Death in eight scenes (first performed in 1932): the movement of the figures (dressed in formal attire: top hat and tails) around a very long board-room table covered with regulation green cloth represents the endless and futile conferences of European politicians during the inter-war years, i.

e., mobilization, combat, war profiteering, movement of refugees, and so on. All the time Death is featured in the background dancing out the rhythm of the ballet.

e., mobilization, combat, war profiteering, movement of refugees, and so on. All the time Death is featured in the background dancing out the rhythm of the ballet.We should not forget that a dance comes across all at once, that is, it is fully comprehensible, no matter what we as observers bring to it in terms of concepts, interests, and so on.

- Program notes, which may or may not outline the origins of the work, the choreographer's intentions, methods of presentation etc.

- Technical aspects, such as the costumes, lighting, accompaniment, and so on.

- Sculptural features, that is, the movement itself in terms of developing shapes and patterns. Notice how the "chase" shapes many films, especially westerns.

Dance is one of the most difficult of the arts to appreciate because, as Henry Moore argued, many people are blind to form. Moore claimed that, although many people attain some accuracy in the perception of flat form, they do not make further intellectual and emotional effort to comprehend form in its full spatial existence (quoted in Redfern, 1975).

Moore argued that sculpture is probably the most difficult of the arts to appreciate.

Moore argued that sculpture is probably the most difficult of the arts to appreciate.A case might be made for the following argument: dance poses an even greater challenge, i.e., dance too exists in three-dimensional space: moving shapes and transient patterns unfold from one moment to the next.

Again: the basic material out of which dancers shape their works is movement, i.e., in terms of bending, stretching, twisting, and rotating movement, to express their minds, emotions, and bodies. Individual movements vary in quality, according to the space in which they are executed, the time taken to execute them, and the weight given them.

In other words, movements acquire color and texture according to whether they ebb or flow, whether they are bound or unbound. Such patterning as the straight line/chorus line say or the circle (cf. Martha Graham) shape movement in unique ways, i.e., giving it solidarity or wholeness as opposed to the sense of fragmentation no patterning at all might convey.

- It goes without saying that different dancers bring different qualities to their performances. Think of the unusual qualities Merce Cunningham brings to his work, e.g., flexibility and fluidity.

- The piece as a composition: this means "getting inside" the dance.

We think of choreography as the primary impulse behind what we see. At this level of perception a language specifically relevant to dance is needed, one that includes technical terms and the language of "physical reality." In other words, as reviewers we must become involved in what we see: we must describe what we see and feel and think.

In conclusion: Every writer who writes about dance faces the following problem: what we cannot describe to ourselves tends to pass us by as part of the formless unknown: what we do not notice we cannot attend to. Engaging in criticism of any kind helps us--as performers as well as spectators--to discipline our perceptions.

Sources Barnes, C.

"The Function of a Critic." In Visions, ed. M. Crabb. Toronto: Simmons and Pierre, 1976, pp. 76-80.

"The Function of a Critic." In Visions, ed. M. Crabb. Toronto: Simmons and Pierre, 1976, pp. 76-80.Coton, A.V. Writings on Dance, 1938-69. London: Dance Books, 1975.

Osborne, H. The Art of Appreciation. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Martin, F. David, and Lee A. Jacobus. The HUmanities through the Arts. 5th Edn. New York: The McGraw-Hill Comanies, Inc., 1997.

Redfern, B. "Developing Critical Audiences in Dance Education." In Collected Conferences Papers on Dance. Warwick: University of Warwick Arts Centre, 1975, ii, 59-76.

Taplin, D.T. "On Critics and Criticism of Dance." In New Directions in Dance, ed. D.T. Taplin. Toronto: Pergamon Press, 1979, pp. 77-91.

Wigman, M. The Language of Dance. London: MacDonald and Evans, 1966.

return to the COMS 365 Home Page

How to write a Professional Dance Scene (Tips and Examples)

So you don’t know how to write a dance scene? The words to use, the actions to describe. It can be challenging. What’s too much? What’s too little?

It can be challenging. What’s too much? What’s too little?

This post will give eight tips on writing dance scenes in a screenplay that most people miss and give actual dance scene examples from scripts accompanied by the movie scene.

So you can write your next dance scene, whether that be:

- Slow dance

- Salsa dance

- Dancing in a club

- Lap dance

- Pole dance

- Breakdance

Let’s begin:

1.) Know the Dance Style and Tell the Reader

This first tip will break the show don’t tell rule, but in specific scenarios, it’s justified.

Name it.

Whether it’s a classical ballet dance or a tap dance.

Saying what type of dance we are about to read on the page is the best way to describe it. It doesn’t matter how you tell them as long as it’s in there.

Examples:

They enter a wonderland of hip-hop break dancers.

She laces up her ballerina shoes.

Announcer Next up to the pole, we call her...White Diamond.

It’s best towards the beginning, especially if the movie isn’t about a dancer and this is a one-off scene. You have to let the reader know what type of dance is happening.

Naming, the dance in the opening, helps the reader imagine what the setting looks like and how slow or fast the dance is happening.

If it’s in a nightclub, people will assume it’s fast-paced unless described differently. If it’s in a strip club, people will think it’s slow and sexual.

We will get in some great ways to describe it, but you must first understand, what you say is more important than how you say it.

2.) Dance scenes are written short

This tip always stops people in their tracks. But yes, dance scenes are written short and not that descriptive.

In my research, every single written dance scene is shorter than the actual movie version. Generally, for every one page in a script, it equals one minute on the screen. But for most scenes with motion, like dance scenes, action scenes, fight scenes.

Generally, for every one page in a script, it equals one minute on the screen. But for most scenes with motion, like dance scenes, action scenes, fight scenes.

Screenplays are just a blueprint for a film, so when writing, remember naming every twirl, flip, or spin isn’t just not needed it’s arguably considered bad writing.

How short are we talking?

I’ve read dance scenes that say

They dance

Yes, Hollywood produced screenplays.

Example:

Pulp Fiction ScreenplayPulp Fiction Dance SceneWhy?

The director will come up with what it looks like; it’s your job to come up with what it feels like. It’s your job to write the essential parts. Now that’s extreme, but it shows how minuscule this part of your script should be.

Example 2:

LALA Land ScreenplayLALA Land Opening SceneEven in a musical, The entire four-minute scene is written in half a page.

4.) Describe the Whole Emotion, not the Entire Dance

When writing a dance scene, you want to give a feeling. This feeling should reflect the tone at the moment.

The non verble comunication.

What are the expressions and emotions your character gives off while dancing? These words are far more valuable in a dance scene than the actual move itself.

Example:

There are no dance descriptions even written just about the emotion the protagonist is feeling.

But what dance moves do you describe? Keep reading.

3.) Only Describe the Essential Dance Moments

What is essential?

The broad strokes of a dance or the most crucial moment.

- The big move for the judges.

- The hardest part for the dancer to pull off.

- The moment of significantly heightened emotion.

If you watch movies, every dance scene has one. And if you read the screenplays, the writer usually writes only that part.

4.) Use Vivid Action Words

How do you describe dance in words? Don’t use dance terminology unless your writing about some Olympic or sporting event. Or if the term is being used in dialogue.

We can talk about what you don’t do because there aren’t firm rules on what you should do when it comes to creativity.

But generally use words that paint a picture. The image you give with your words is all that matters.

Example:

Don’t write this

She jumps

Write this

She leaps

or better yet

She floats in the air.

Think about it everyone jumps basketball players, kids on the playground. But “floating” paints a picture of grace I can see. It’s specific to a ballerina or contemporary dance.

It’s specific to a ballerina or contemporary dance.

Example 2:

Don’t write:

She dances with her hands up.

Write:

Her hands held rollercoaster high, raging to the beat of the drum.

I’m trying to describe dancing in a club or a Rave.

Since we are trying not to bore the reader with too many details, we have to paint an image with the words we know. Think what type of jump it was? Basic terms will not work when describing a dance. You have to think harder than that.

5.) Break Up More Extended Scenes with Dialogue

Dialogue is a great way to break up any action, including dance. It stops your dance scene from being two-wordy and keeps the reader engaged.

I think about the Mr. and misses smith dance scene. This scene is quite long, but what keeps it intresting is the antiques and wordplay from both assassins trying to get the upper hand during the dance.

Example:

Mr. and Mrs. Smith Dance Scene6.) Know the Steaks of the Dance SceneWho wins or loses.

Not purely speaking from a competition sense but ask yourself:

- What do we find out about the protagonist?

- What questions do we have after the scene?

The actions your character takes during the dance scene speak volumes.

Just like the Mr. and Mrs. Smith example above, we can tell by the conversation they don’t trust each other, but by the end, we find out that maybe in their marriage, real feelings were involved.

Find out the steaks of the scene, who wins and who loses based on the result of the scene.

If you noticed, this isn’t much of a Dance scene thing but how to write a scene in general because every scene must have these things.

This brings me to my second to the last point.

7.) What do we Discover as a Result of the Dance Scene?There has to be an end goal of discovery. If not, it doesn’t matter how amazing your wordplay is or your character’s actions.

By looking at your story from a birds-eye view, a skilled reader will know you have no idea what you’re doing.

Example:

LALA Land SceenplayLALA Land Dance Scene8. Reference the Sound

Sound is just as big a part of a dance scene as the physical movement is, so don’t hesitate to engage more of the readers’ senses by referencing the sounds that the viewer will hear in the scene, such as the music or, like in this scene from Black Swan, the way that the music ends.

Conclusion

In this post, you learned:

What not to do when writing dance scenes just as much as what to do.

- Tell the reader the type of dance upfront.

- Keep them short—preferably short, punchy sentences.

- Emotion trumps actions.

- Never use dance terminology. It confuses the reader.

- Have a point ot the dance scene.

Now its time to hear from you:

Did I miss anything?

How have you seen dance scenes written in screenplays?

Whatever your answers are, let’s hear them in the comments below.

Happy writing.

Posted in How to Guides By D.K.WilsonPosted on Tagged dance scene

Dance and its role in the life of children about the direction of dance

/Register for a lesson and dance for children and teenagers here/

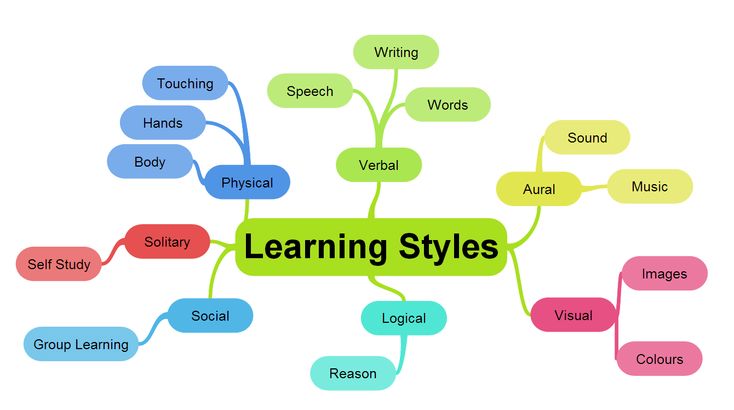

Among the many forms of artistic education of the younger generation, choreography occupies a special place. Dance classes not only teach to understand and create beauty, they develop imaginative thinking and fantasy, give harmonious plastic development. In comparison with music, singing and fine arts, which have their permanent place in the school schedule, dance, despite the efforts of well-known teachers, choreographers, psychologists and art historians, could not be included in the number of compulsory school subjects. Meanwhile, choreography, like no other art, has enormous potential for the full-fledged aesthetic improvement of the child, for his harmonious spiritual and physical development. nine0003

Dance classes not only teach to understand and create beauty, they develop imaginative thinking and fantasy, give harmonious plastic development. In comparison with music, singing and fine arts, which have their permanent place in the school schedule, dance, despite the efforts of well-known teachers, choreographers, psychologists and art historians, could not be included in the number of compulsory school subjects. Meanwhile, choreography, like no other art, has enormous potential for the full-fledged aesthetic improvement of the child, for his harmonious spiritual and physical development. nine0003

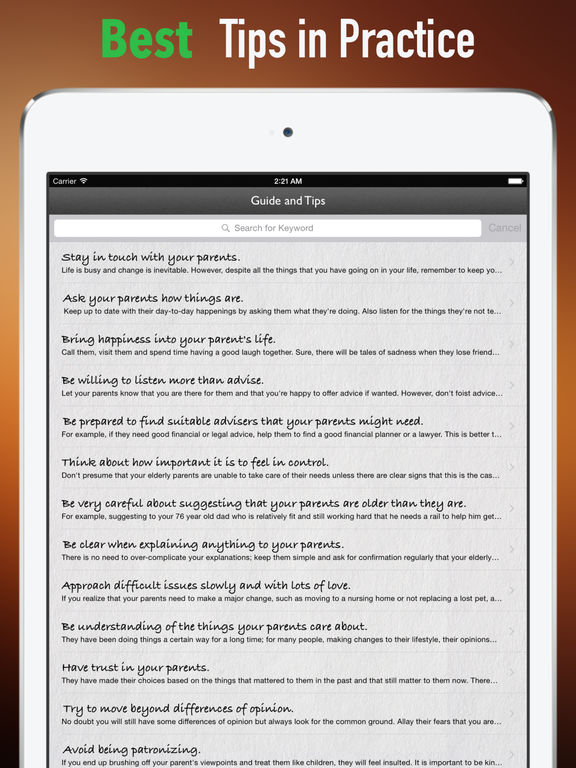

Choreography classes are designed to: develop strength, endurance, dexterity, flexibility, coordination of movements, the ability to overcome difficulties, temper the will and improve the health of children. And also develop a sense of rhythm, form beautiful manners, gait, posture, expressiveness of body movements and postures, get rid of shyness, tightness, complexes, teach you to enjoy the success of others and contribute to the overall success.

The movements used in the choreography, which have passed a long selection, certainly have a positive effect on the health of children. We can talk about a kind of choreotherapy - a method developed and tested in recent years

Man started dancing a long time ago, much earlier than he started talking. The desire to dance expressed the need to convey to others their feelings, emotions with the help of the body. For a person of a primitive society, dance was a way of thinking, a way of life - almost all important events in life were celebrated with dances: birth, death, war, healing of the sick, etc. Through dance, people prayed for the appearance of rain, sun, fertility, protection, etc. The dance was not just connected with life, but was life itself. For example, in ancient Greece, the muse of dance and choral singing Terpsichore was included in the pantheon of deities. In India, according to Hindu legend, the world was created by the dancing god Shiva. In the East, dance is perceived as something divine that a person once received from the gods as a gift. nine0003

nine0003

The most important thing is that there are no people who don't dance. Naturally, this does not mean a professional dance, which has its own rules, numerous steps and certain movements, but a dance devoid of any rules, in which only the body dances, and the mind is turned off. Such dances can usually be found on dance floors (discotheques, clubs, etc.) and streets.

Everyone loves to dance - both adults and children. And it doesn’t matter if, according to the rules, a person dances or moves as best he can. Either way, dancing is fun. Moreover, the feeling of joy acquires new nuances depending on what kind of dance a person performs - cheerful or romantic, tender or passionate

Dance creativity as such occupies an important place in the spiritual and moral education of children, adolescents and youth. Creative teams of a choreographic orientation are one of the most popular and demanded by society areas of leisure activities, additional education and vocational guidance for children and youth. In this regard, it is difficult to overestimate the importance of professional pedagogical skills for the head of a choreographic team. In his work, the leader of such a team solves a huge number of tasks. Dance art itself is multifaceted, the choreographer must understand almost all areas: art, education, pedagogy, psychology, economics, etc. He must love his work. nine0003

In this regard, it is difficult to overestimate the importance of professional pedagogical skills for the head of a choreographic team. In his work, the leader of such a team solves a huge number of tasks. Dance art itself is multifaceted, the choreographer must understand almost all areas: art, education, pedagogy, psychology, economics, etc. He must love his work. nine0003

Children definitely love to dance, they have fun, they rejoice, imagine themselves in different images, fantasize and develop. They learn purposefulness, due to the desire to learn, to achieve the correct execution of this or that movement, this or that manner of a certain style of dance. Children are interested in this artistic direction, dancing they open up, relax and splash out excess energy. If a child is seriously passionate about dance, it means that he has something to strive for, something to do, someone to look up to. As a result, the end result will please everyone, but first of all - the children and the teacher. Dance is important for children, so dance art needs to be developed, choreographic circles and groups should be created in schools, leisure houses, etc. nine0003

Dance is important for children, so dance art needs to be developed, choreographic circles and groups should be created in schools, leisure houses, etc. nine0003

Dance classes not only develop musicality, but also help to develop willpower, communication skills and develop creative potential. Indeed, many studies by psychologists have proven that children involved in dancing achieve greater academic success than their peers, and are also ahead of them in general development. Dance helps to form the initial mathematical and logical representations of the child, trains the skills of orientation in space and develops speech. Dancing helps to develop qualities such as organization and diligence. Rhythm, plasticity form the basic motor skills, abilities and prevent postural disorders. Such classes enrich the child's motor experience, improve motor skills, develop active mental actions in the process of physical exercises. Even the most withdrawn children become more liberated, open and sociable. nine0003

nine0003

Music and dance are what you need to develop a good ear for music and a sense of rhythm in your child. It has long been proven that there is a connection between movement and thinking. Through the training of each new movement, the child develops the most powerful nerve networks. When the repertoire of movements expands, then each step in development will give the senses (especially hearing, touch and vision) an increasing advantage in the perception of environmental information.

The art of dance is an excellent means of educating and developing children. It generalizes the spiritual world, helps the child to reveal himself as a person. The organic combination of movement, music and play creates an atmosphere of positive emotions, which in turn liberate the child and make his behavior natural and beautiful. A real dance is a true feast for the soul and body. There is a huge variety of such holidays - ballet and ballroom dancing, rock and roll and salsa, rumba and tango, belly dance and classical waltz

There is a good African proverb “If you can talk, you can sing; if you can walk, you can dance”. We all know how to dance, a dancer lives in each of us, and he wants to dance. You don't have to learn to dance, everything happens very simply. To do this, you just need to retire for a while and put on the music that you like, forget about everything that worries you, and just relax. Yes, and you need to know that you are not dancing for anyone, but just dancing, and your dance is a kind of disappearance from this world. nine0003

We all know how to dance, a dancer lives in each of us, and he wants to dance. You don't have to learn to dance, everything happens very simply. To do this, you just need to retire for a while and put on the music that you like, forget about everything that worries you, and just relax. Yes, and you need to know that you are not dancing for anyone, but just dancing, and your dance is a kind of disappearance from this world. nine0003

Registration of children and teenagers for any kind of dance is HERE.

Author: Vavilova L.Yu.,

teacher ODOD GBOU lyceum 384

Kirovsky district of St. Petersburg

“How to understand modern dance and how to write about it?”

The IV Open Forum of Experimental Plastic Theaters “PlaStforma” invites

February 9-13 at 19.00

to the series of lectures

“How to understand modern dance and how to write about it?”

Lectures will be held by Polish experts Anna Krulitsa and Jadwiga Majewska. nine0003

nine0003

The lectures will focus on an overview of the general landscape and the main trends in the development of contemporary dance, as well as analytical methods and approaches with which to understand and analyze contemporary dance. The lectures will be accompanied by a video demonstration.

Schedule of lectures

February 9 at 19.00 / National Center for Contemporary Arts

(Nekrasova str., 3) – lecture by Anna Krulitsa “Modern dance in the theory and practice of writing” . Entrance with CSI tickets! nine0003

Anna Krulitsa about the lectures:

“How can we talk and write about modern dance? This question constantly pops up in many discussions and does not lose its relevance for people involved in the world of dance. In the course of the two lectures, my goal will be to introduce some of the ideas aimed at understanding modern dance, as well as its reflection in two historical contexts - the dance theater (Tanztheater) and the archeology of dance.

Tanztheater is one of the key turning points in the history of contemporary dance. It was initiated by Kurt Joss and received wide distribution and recognition in the work of Pina Bausch. The Wuppertal Dance Theater of Pina Bausch presented a new face of dance and the possibilities of its perception. Tanztheater convinced audiences all over the world that it is possible to go beyond pure dance and talk about the social context through the body and plasticity. The performances of Pina Bausch grow out of the comprehension of personal and cultural memory. nine0031 Archeology of dance is a young direction in thinking about dance, aimed at extracting information about choreography from the past. Choreographers become a kind of archaeologists who carry out "excavations" in the reservoir of cultural memory. Their goal is to extract from the past the "products" of the work of predecessors. At the same time, their task is more difficult than that of historians or archaeologists proper, since the problem of dance and theater is the lack of material products of the activity of actors / dancers and directors. When there is a void in the place of the original, how can we fill it? And what to do with it?" nine0003

When there is a void in the place of the original, how can we fill it? And what to do with it?" nine0003

February 10 at 20.00 / Art Center “Krok”

(Kuibysheva st., 22, building 6, 3rd floor, room 56) – lecture by Anna Krulitsa “Modern dance in the theory and practice of writing” (continued) .

Admission is free!

February 11 at 19.00 / National Center for Contemporary Arts – lecture by Jadwiga Mayevskaya “Everything was possible. Rethinking the concept of "dance" in the 1960s - Judson Dance Theater" . Entrance with CSI tickets!

Jadwiga Majewska about the lecture:

“The term “postmodern dance” was introduced by Yvonne Rainer, who in this way characterized her own works and those of her peers, carried out jointly at the beginning of the 1960s at the Judson Memorial Church in New York. Reiner meant, first of all, chronology, since she belonged to the generation that came after modern dance. The first generation of Judson Dance Theater artists created an alternative, on the one hand, to the traditions of modern dance, and on the other, to the traditions of classical ballet. The transformation, which at first was perceived as a natural change of generations, turned out to be a radical breakthrough in understanding what dance is.”

The transformation, which at first was perceived as a natural change of generations, turned out to be a radical breakthrough in understanding what dance is.”

“Reiner, Simon Forti, Steve Paxton and other choreographers 19From the point of view of aesthetics, nothing united the 60s, except for their radical approach to choreography, the desire to redefine the concept of dance” (Sally Baines “Terpsichore in Sneakers”).

February 12 at 19.00 / Krok Art Center – lecture by Yadviga Maevskaya “After modernity – postmodernity. Sources, Methods, Contexts and Consequences of Judson Dance Theater and Grand Union” . Free admission!

Jadwiga Majewska about the lecture:

“The transformation, which at first was perceived as a natural change of generations, turned out to be a radical breakthrough in understanding what dance is, in understanding the tasks and specifics of the activity of a choreographer and dancer (artist), as well as a witness and participant in events ( spectator). Moving away from the principles of historical modern dance and even avant-garde 19In the 1950s (including not only Cunningham, but also Anna Halprin, James Warring, Merle Marsicano and others), post-modern choreographers found new ways to expose dance as a medium. This desire coincided with a cultural trend reflected in Susan Sontag's Against Interpretation (selected essays from the 1960s and 1970s)

Moving away from the principles of historical modern dance and even avant-garde 19In the 1950s (including not only Cunningham, but also Anna Halprin, James Warring, Merle Marsicano and others), post-modern choreographers found new ways to expose dance as a medium. This desire coincided with a cultural trend reflected in Susan Sontag's Against Interpretation (selected essays from the 1960s and 1970s)

the most important features of postmodern dance. Among them: references to nature, history, a new attitude to time, space and body, to the understanding of dance, its function and structure. nine0003

While each member of the Judson generation had a distinct personality, we will talk about their activities in the context of a group. Each of them developed their own original program not only for creativity, but for creative life, without caring about social status or media success. They were not trained specialists in the academic sense of art. These are ordinary people who have observed what is happening around and with a genuine passion sought to transform reality into actions that can be shared with others.