How to interpret dance

A Guide to Interpreting Contemporary Dance

Visual Culture

Natalie Cenci

Feb 14, 2018 12:05AM

It’s safe to say the blueprint for dance in the United States and Europe has largely been upended over the past century. Watching dance performances was once a predictable affair—characterized by narrative plots, ornate costumery, theatrical set design, a classical score, and movement that either was (or followed the traditions of) ballet. But these days, seeing dance can, at times, feel as though you need a personal translator to make sense of what’s going on. But it doesn’t need to be an alienating experience. Below, we share a brief guide to understanding contemporary dance, including insights from choreographers, dance historians, and other experts to help demystify the art form’s practices today.

What is contemporary dance?

Merce Cunningham Dance Company in Beach Birds. Photo by Niklaus Strauss (1991). Courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust. All Rights Reserved.

So what are we talking about when we say “contemporary dance”?

While the term is mainly used in major dance hubs in the U.S. and Europe, it can be used to refer to anything from hip-hop to non-western folk or tribal dance rituals. More broadly, it refers to modes of dance that began to emerge in the mid-20th century.

Encompassing myriad cultural, economic, social, and temporal nuances, it may be better to understand the term as “a functional catchall,” says Moriah Evans, a choreographer and editor in chief of Movement Research Performance Journal. It implies “you are working on the form of dance in the current moment,” she offers.

Susan Foster, choreographer and dance scholar at UCLA, warns against trying to cobble together a hard and fast definition. “You come up with these overarching umbrella terms,” she explains, “and a lot of people who have very different ideas about what dance is become invisible.”

Attempts to classify what, exactly, contemporary dance is have been almost unanimously abandoned, due in part to the inability to account for the distinct historical contexts that individual dance practices emerge from. “Not every dancer has the luxury of being ‘of its time’ in the current world,” stresses dance scholar Noémie Solomon.

“Not every dancer has the luxury of being ‘of its time’ in the current world,” stresses dance scholar Noémie Solomon.

In today’s study of movement, Solomon continues, dance makers are seeking solutions to questions including: “What does it mean to move, or to be moved? Who is afforded movement, and who isn’t? What bodies are forced to move and others kept still? How does movement intersect with issues of labor and visibility?” Dance is also, by nature, an ephemeral art.

“Dance has often been hailed as an art that disappears, as if dance didn’t leave any tangible trace,” Solomon says. “Many contemporary dancers have really engaged with this question of what it is that dance produces in time.” We can see that dance evades categorical definition in the same way that it won’t be pinned down by the word “contemporary.”

The history of contemporary dance in the U.S. and Europe

Barbara Morgan (1900–1992)

Martha Graham, Letter to the World, 1940

Heritage Auctions

Bidding closed

Advertisement

American and European traditions have largely shaped how dance is understood in the West today, including the parameters that define what dance can be. These guidelines have been in question since the early 20th century, when modern dance began to develop.

These guidelines have been in question since the early 20th century, when modern dance began to develop.

In the U.S. today, contemporary dance is widely considered to be the outgrowth of explorations by the Judson Dance Theater in New York, where the vision of dance went beyond “defining what dance is” to “expanding what dance can be.”

Discussions of the origins of contemporary dance in North America almost always trace back to performances coming out of cultural hubs like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles from the end of the 19th century into the present. These traditions stem from a strong matriarchal lineage of modern dance, with Isadora Duncan at the helm.

At the turn of the 19th century, Duncan catalyzed a redefining of the discipline with her vision of dance as a vehicle for expressing the soul, and contended with the popularity of vaudeville performance. Her emphasis on making the inner life visible disrupted prevailing ideas around dance—that it should be strictly narrative based and entertainment driven. Martha Graham articulated this idea further, prioritizing expressive movement over narrative elements. Driven by an interest in gravity, she relinquished dancers from wearing ballet slippers, which were ubiquitous up to that point, and instead had them perform barefoot.

Martha Graham articulated this idea further, prioritizing expressive movement over narrative elements. Driven by an interest in gravity, she relinquished dancers from wearing ballet slippers, which were ubiquitous up to that point, and instead had them perform barefoot.

The innovations of Duncan and Graham created space for other radical practices to take shape. Sidestepping the teachings of Graham, her student Merce Cunningham was in direct dialogue with the visual arts community of the 1950s. He and John Cage were lifelong collaborators, and in the same way that the composer redefined music as sound, Cunningham redefined dance as movement. He integrated seemingly ordinary movements into his works and played with elements of chance, while stripping away the necessity of a musical backdrop. These explorations suggested that dance could be anything.

These explorations suggested that dance could be anything.

In tandem with this largely white experimental dance community in the U.S., choreographer and dancer Alvin Ailey forged a voice for African Americans, beginning in the late 1950s. His innovative choreography drew together influences from modern dance, ballet, and black cultural currents in the United States, such as jazz, blues, and gospel music.

Later, the artist-driven dance collective Judson Dance Theater formed in Greenwich Village in 1962, characterized by its militant blending of the boundaries between dance and life. Artists who performed for the collective during its two-year lifespan included prominent figures such as Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Robert Morris, Lucinda Childs, and Carolee Schneemann.

The reimagining of the body by the Judson Dance Theater freed dance to “be seen as a means to incorporate non-dancers within choreographic practices, to relate dance’s forms to everyday movements and broad cultural issues,” Solomon explains. Their influential work paved the way for the multifarious forms that dances takes into the present.

Their influential work paved the way for the multifarious forms that dances takes into the present.

Peter Moore, Performance view of Trisha Brown and Steve Paxton in Brown’s Trillium, Concert of Dance #4, January 30, 1963. © Barbara Moore/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy of Paula Cooper, New York.

In Europe, contemporary dance describes experimental dance forms that began to emerge in the 1980s. In contrast to the U.S., Europeans have less of a history of experimental dance that moved beyond the realm of ballet until that point, even though dance makers had been pushing the boundaries of classical forms throughout the 20th century. It’s also important to note that in European countries, there is a stronger economic investment in developing dance as an art form than in the U.S., which is one reason why the term contemporary may hold more weight abroad.

While groundbreaking dance stateside consistently involved a systematic and demonstrative rejection of classical modes of performance, in Europe, such traditions have served as fodder for new work. Avant-garde dance in Europe, for example, is strongly supported by a theatrical backbone that is still intact.

Avant-garde dance in Europe, for example, is strongly supported by a theatrical backbone that is still intact.

The itinerant Parisian dance troupe Ballets Russes, for instance, destabilized norms around content early on in the 20th century and made strategic use of shock factor, incorporating erotic plotlines and tribal references. Under the helm of Sergei Diaghilev, they too were known to commission costumes and sets by leading artists, including Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

Moriah Evans: Figuring, performance view, SculptureCenter, New York, 2018. Photo © Paula Court.

At the Bauhaus in the 1920s, experiments with dance became an interdisciplinary affair and dance was a medium for bringing the gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”) to life, through an emphasis on bridging the various performative elements of costume, lighting, music, and stage, again emphasizing theatricality.

The European trajectory of dance saw a simplification of movement in tandem with a heightening of emotion. This is evident in the work of German titan Pina Bausch who, as the director of the Tanztheater from the early 1970s until her death, started intensifying the mood on the stage, with highly dramatized performances where emotion transcended narrative.

This is evident in the work of German titan Pina Bausch who, as the director of the Tanztheater from the early 1970s until her death, started intensifying the mood on the stage, with highly dramatized performances where emotion transcended narrative.

Around the same time, as choreographer for the Stuttgart Ballet, William Forsythe was reworking ballet, changing its contours to reflect new visions of the practice that could integrate traditional and innovative ideas about choreography, costume, music, and set design to formulate something original. Forsythe’s career has extended into the visual arts, where he explores concepts of choreography.

Since the ’80s, dance maker Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker has continued these non-narrative tendency imposing rigorous everyday movements into her works, employing pattern, repetition, and speed. With a demand for discipline, her dances make fierce emotions visually palpable.

How does contemporary dance differ from performance art?

Keersmaeker: Fase by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker/Rosas. Photo © Herman Sorgeloos.

Photo © Herman Sorgeloos.

“Generally people think of dance as a kinetic art,” says Foster. “It’s about bodies being articulate through movement.” But how does it differ from certain types of performance art?

As some dance has become more interdisciplinary, the overlap with performance art has made distinguishing between the two a recurring conundrum. The confusion speaks to the fact that these experimental practices share common concerns, including “a reflexive approach to the body as art material,” and “the ways in which it endures and generates experiences of time and effect,” Solomon explains. “Performance art’s focus on duration can be seen in close relation to dance’s questioning of movement, which often leads to a stretching (or deceleration) of time.”

Circling back to the Judson Dance Theater (which is the subject of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in fall 2018), where speech, film, and experimental music were interlaced with dance as a way to upset expectation, we can arguably identify an origin of the murkiness. However, Foster would challenge that we cannot draw lines between the two, without looking at individual practices. In the same vein, Evans would encourage an interdisciplinary outlook, and doing away with the “identity-driven divisions” that confine practitioners to either dance or performance art.

However, Foster would challenge that we cannot draw lines between the two, without looking at individual practices. In the same vein, Evans would encourage an interdisciplinary outlook, and doing away with the “identity-driven divisions” that confine practitioners to either dance or performance art.

How to approach watching contemporary dance

A.Ailey, J.Truitte, D. Martin, M. White, E.Thompson, M.Marshall in Revelations. Photo by Jack Mitchell.

Given this brief primer on some of contemporary dance’s larger questions, we can begin to find an approach to viewing dance that may initially seem illegible to untrained eyes. It is important to first remember, as Foster says, that dance reflects who we are. “We are moving bodies, and dance makes that more evident than ever,” she says.

Recognizing ourselves in dance that is visually challenging can help to bring down the barrier between what we expect to see and what we actually see. To build on this, we as audience members, can work with the theory of kinesthetic empathy, which proposes that dance is a two-way conversation that engages all of our senses and “heightens how we feel our body in space, in relation to others,” Solomon explains.

Moving beyond the visceral components of comprehension, viewing more dance will, in time, allow us to draw formal connections and conclusions about what we’ve witnessed. It’s important to remember that dance is ostensibly a visually jarring experience.

If all else fails, take comfort in the fact that well-respected scholars, like Foster, are equally interested in the dance that happens on a stage, as that which happens in a bar. “It can tell you something completely illuminating about what the body is or can be, and about people's social relations to each other,” she says.

Natalie Cenci

How to Analyse Dance, Laban and Semiotic Levels, and Analysis (4.6.1)

Last Updated on March 4, 2022

Table of Contents

How to Analyse Dance

The analysis of the different data sources happened in overlapping phases. The videos were the first data set I started analyzing as the study revolved around the dance as physical performance and movement.

The analysis followed Adshead (1988, p. 13), who states that:

Making sense of a dance requires . . . that an interpretation is made, derived from a rigorous description of the movement and supported by additional knowledge of the context in which the dance exists.

Adshead (1988)

According to Adshead, to describe dance, we need to consider four elements:

- movements

- dancers

- visual settings

- and aural elements.

To interpret dance, for Adshead, it is also necessary to consider elements such as the:

- socio-cultural background

- context

- genre and style and the subject matter

Hence, from the videos, I analyzed the movements of the dance and also the context in which it was taking place, the people, the physical and social location, the props and costumes and the technology involved in the reproduction of dance.

Semiotic Levels in Dance

In addition to the elements highlighted by Adshead, dance has semiotic levels.

Giurchescu (2001, p. 112) posits that dance is a ‘cultural text’ in which social interactions and dance elements coexist and influence each other in various ways, according to the style.

Dance communicates through movement, as well as non-choreographic means of expression, such as props, text/poetry, music, costumes, staging, social rules, pantomime, gestures, verbal expressions, facial expressions and proxemics (use of space).

Giurchescu then identifies five interacting and coexisting semiotic levels:

- A transcultural level related to psychosomatic perceptions of the self (emotions, feeling, moods, intentions). Transcultural because human emotions transcend cultural boundaries.

- A conceptual level. This refers to acquired knowledge about dance.

- A ritual level, where dance has symbolic and mythical meaning.

- A level of social interaction. At this level, dance reflects the position of people in society and it includes reference to gender (and it could be added body types), kinship, social status, age.

- An artistic level, where dance is valued as a performance to entertain an audience.

Most of these levels can be observed in the videos, while written texts and interviews provide the discursive element, shedding more light on the observations gathered from the videos.

I found that texts and interviews were useful to discover the commonly held views and beliefs among practitioners about Raqs sharqi.

Similarly, Butterworth (2012, p. 44) identifies four layers for the semiotic of dance:

- The meaning that the choreographer brings such as intention, concept, ideas, content, form.

- The dance itself and the signs that reside in it once it is completed (the dancers, quality, patterns, vocabulary, the context).

- The feelings, experiences and interpretations of the performers.

- Reading, perceiving and making sense by the audience.

Following the analysis of videos and textual elements, it became clear that, although Raqs sharqi has all these elements, some levels were more evident and powerful than others in the discourse around it.

It emerged that the feelings and emotions were particularly significant for Raqs sharqi practitioners and audiences, as well as the individuality of the dancers and how their dance reflected their personalities.

Using Laban Analysis

As I started to analyze the movements from the videos, the type of analysis most suited to investigating the emotional aspects of movements (both with regards to individual dancers and to the qualities specific to a certain genre as a culturally influenced movement system), was Laban analysis.

I did not use a dance notation technique, as the dance was already documented in the videos.

Instead, I observed and analyzed the movements qualitatively and then compared my observations with observations by other practitioners available online and from interviews with participants.

Laban Movement Analysis (LMA)

Laban’s theory of movement includes a notation system and an analysis system, called Laban Movement Analysis (LMA).

Within LMA, there are many aspects and concepts that can be drawn upon but, for the purpose of this thesis, I will only elaborate on the ones which were relevant for this work.

The concept I have employed for my raqs sharqi analysis is the Laban’s ‘effort system’, based on the ideas of body, weight, space, time and flow (Horton Fraleigh and Hanstein, 1999; Newlove and Dalby, 2003; Butterworth, 2012).

The Body

In LMA, weight, space, time, and flow as expressed by the body, are connected to each other, and together they produce a variety of movement qualities, depending on the combination of these elements.

Weight

Weight refers to the resistance that the body (or one or more of its parts) opposes to gravity, whether it resists or gives in to gravity (Raqs sharqi, for example, often displays a quality of being earthy, connected to the ground with the feet, but also lifted at the same time, especially in the upper body).

So, a movement can be more or less heavy (strong) or light.

Time

Time refers to the movement speed, which can be more or less quick (sudden) or slow (sustained).

For example, in Raqs sharqi, there can be quick movements of the hips to mark a drum accent or slow hips figures of eight to embody a slow melody.

Space

Space refers to the pattern followed by a movement, which can be in a straight line (direct) or waiving in and out (indirect).

Raqs Sharqi Movements and Laban

Most Raqs sharqi movements are typically indirect, such as figures of eights, circles, and snake-like movements of torso and arms, but a dancer can decide to make gestures with straight arms or travel in space in a direct trajectory.

Movement qualities of weight, space, and time combine together in ‘qualitatively oppositional descriptions to indicate functional and expressive aspects of the lived body’ (Kaylo, 2009, p. 1). Figure 8 (Clara, 2012) illustrates the eight types of movement resulting from the combination of these oppositional combinations of qualities.

Figure 8 – Laban Movement Efforts and Qualities

Another attribute that contributes to the quality of movement, is flow, which can be free or bound. As Newlove and Dalby explain (2003, p. 127):

Flow is mainly concerned with the degree of liberation in movement . . . To understand and describe flow it is necessary to consider its complete opposite: movement which is broken up and jerky with the quality of ‘starting and stopping’.

Newlove and Dalby explain (2003)

In Raqs sharqi vocabulary, both types of flow are seen (to embody the expressions of the music), but different dancers (depending on their individual style, but also on the prevalent trend during their lifetime) may have a distinct preference for one or the other.

Free flow can be sweeping movements of the limbs or free-flowing hips and torso articulation, while bound flow is often seen in the hips and stomach, with slow contractions and quick releases of the muscles.

All these movement qualities need to be analyzed in combination, to create a holistic picture of the movement. As Foster (2016, p. 5) points out:

Laban’s mode of thought permits both analysis and synthesis. Every movement traverses space, and this takes time, the one implies the other, and every movement involves a degree of energy: but the three elements are inseparable, one cannot be altered without modifying the others and therefore the whole.

Foster (2016)

Emotional Characteristics and Quality of Movement

The qualities of movement do not just describe movement per se, but also express the emotional characteristics of a genre, as well as the inner feelings of the dancer.

This was Laban’s intention when devising his analysis system as, according to Preston-Dunlop (2010, p. 66), ‘Laban asserted that the factors of motion, its weight/force content, its spatial form, its timing, and its flow content are signifiers in all human performance . . . the embodiment of inner states of mind’.

. . the embodiment of inner states of mind’.

Another conceptual tool that guided the analysis of dance for this research is Kaeppler’s (1972, 2001) idea of kinemes, morphokines, motif and choremes, which she devised for the analysis of dance, drawing from linguistics. As Kaeppler (2001, p. 51) explains:

Kinemes are minimal units of movement recognised as contrastive by people of a given dance tradition (analogous to phonemes in a spoken language). Although having no meaning in themselves, kinemes are the basic units from which the dances of a given tradition are built. Morphokines are the smallest units that have meaning as movement in the structure of a movement system (meaning here does not refer to narrative or pictorial meaning).

Kaeppler (2001)

Kaeppler then mentions allokines, which are variations on a kineme; motifs, which are ‘sequences of movement made up of kinemes and morphokines that produce short entities in themselves’ (2001, p. 51) and choremes, which are ‘motifs choreographed in association with meaningful imagery’ (2001, p. 52).

51) and choremes, which are ‘motifs choreographed in association with meaningful imagery’ (2001, p. 52).

Motifs and choremes together form a dance, which can have a structured choreography or can be improvised. Table 9, on the following page, gives further definitions and illustrations of these concepts.

Click the graphic below to see larger version!

Table 9 – Kaeppler’s terminology and examplesKinemes and this Dance Heritage Research

For the purpose of this study, the elements analyzed have been limited to the levels of kinemes and, in some cases, motifs.

According to Kaeppler, a dance ethnologist can take note of the movements of a dance tradition (by using, for example, Labanotation) and then subject the resulting kinetic notation to ‘“emic” analysis to obtain an inventory of the significant movements’ (1972, p. 174) and identify the kinemes, by consulting the participants who practice a certain dance tradition.

For this research though, the researcher’s point of view was already emic, because of my inside knowledge of the movements’ tradition of Raqs sharqi.

By isolating small units of movement (kinemes and allokines (see footnote), it was possible to identify the basic Raqs sharqi movement vocabulary, which identifies this genre from a movement point of view.

This is important from a cultural heritage perspective, to start assessing authenticity since, as argued when outlining the research questions (3.8), to safeguard heritage we need to know what the object of this safeguarding is.

In analyzing the videos, my main focus was on the dance and its context.

However, the dimension of the videos as visual artifacts could not be ignored and these videos provided other types of data.

Using Visual Materials

I did not do an in-depth analysis of the videos as artifacts and carriers of meaning, as this would be outside the scope of this thesis, but some elements were considered.

According to Rose (2012, p. 19), visual materials include three sites: ‘the site of production . . . where the image is made; the site of the image itself . . . its visual content; and the site where the image encounters its spectators . . . its audiencing’.

. . its visual content; and the site where the image encounters its spectators . . . its audiencing’.

On top of these three sites, according to Rose, there are three aspects or modalities, which each of these sites has, and they are:

- technological

- compositional

- and social modalities

Figure 9, illustrates how these sites and modalities overlap.

In analyzing the data from the videos, some of these elements have been touched on.

For example, the social modality of the audiencing site is in part expressed by the comments available under the YouTube videos.

The technological modality of all three sites was also taken into consideration in trying to understand how technology influences the recording, representation, perception, and transmission of dance.

Figure 9 – Visual Sites and Modalities1st Phrase of Video Analysis

The first phase of the video analysis took place as I watched the videos for the first time (just over 1,000 videos).

As I watched and observed the videos, I wrote notes and, while doing so, I selected a smaller number of those videos, as being the most significant.

After watching a certain number of videos for each dancer, certain patterns emerged, which showed each dancer’s style and signature moves, as well as trends in the presentation and context of dance for each chronological timeframe.

As most videos showed a repetition of patterns for each dancer, only some of the videos watched in the first phase were selected for the second round of analysis.

In addition to making notes in Word, I created an Excel table with four tabs (see the screenshot in Figure 10).

In the first tab, I listed the most common basic Raqs sharqi movements (kinemes/morphokines) that I noticed in the first column on the left and the names of the dancers across the top in the first row and, in each column, whether each dancer used each movement or not.

In the first column, I also listed the Laban qualities, to check which ones each dancer expressed the most.

In the remaining three tabs, I listed, for each dancer, respectively: the dance styles; the costumes styles, and which props they used.

Figure 10 – Screenshot of movements and dancers Excel spreadsheet2nd Phrase of Movement Video Analysis

The second phase of the movement analysis overlapped with the writing of the dance analysis (Chapter 5) and with the analysis of some of the written texts and other visual material gathered online and offline.

After the first phase of the analysis, a well-defined timeline emerged, with specific timeframes.

Hence, this called for a chronological presentation of the dance analysis, which led to a history of Raqs sharqi.

As I wrote the dance analysis, I referred to the analysis table in Excel and to the notes I had written for the first phase of the video analysis.

At the same time, I watched again only the videos which I selected from the first phase of the analysis.

In the second phase of the video analysis, I also coded the videos and the notes taken while watching them, using Zotero (I will explain more of this process in 4. 6.3).

6.3).

At the same time, I read, annotated, and coded some of the online and offline texts, especially anything that related to the dancers whose dance was being analyzed or any associated emerging themes.

As I re-watched videos, explored more textual data, and coded this material, I was writing the dance analysis.

For this chapter, I also used material from the interviews I had coded, where there was a reference to the dancers who appeared in the videos.

In the dance analysis write-up, I narrowed down videos further, quoting only the most representative ones in the text.

While I watched the selected videos a second time, I also took screenshots of certain scenes, in order to use them in the thesis. This procedure helped me to focus and immerse myself even more in the data.

Limitations of this Dance Analysis

Before moving on to explain how I analyzed texts, I would like to discuss the limitations of this dance analysis.

In 2.5 and 4.4.1, I already mentioned that in dance studies it is widely acknowledged that videos, for documenting and analyzing dance, are very useful but also limited, as they mediate the dance and provide just a point of view of the performance.

Videos Only Show Dance from a Specific Angle

Videos allow the dance to be seen from a specific angle only. For this reason, Farnell (1994, p. 963) advises writing a Labanotation score, as well as recording videos, in order to capture ‘the spatial relationships between participants, and between participants and objects, and the organization of space internal and external to the rite’.

Moreover, Farnell (ibid.) posits, in order to write a Labanotation score, the researcher cooperates with the performers ‘to record the action from each agent’s perspective’ as videos are used as a base for discussions with participants while writing the score.

As the majority of the videos I used are from a distant past, I could not be present to notate a score and also it was impractical for me to discuss the videos with the performers, as they are not accessible (the majority of them have passed away and the few who are still alive are difficult to contact). Thus, I had to settle with analyzing videos only.

The Context of the Video as Part of a Movie

Another issue to take into consideration is that the majority of these videos are part of a movie.

Hence, the ways in which these films were shot, the techniques, the director’s point of view, and the language of cinematography as a medium in itself will have influenced the way in which the dance was represented.

Many old belly dance scenes on Youtube are from movies.For example, as Bacon (2003) discusses, dancers in movies tend to dance for the camera, thus creating a front similar to a stage rather than moving around facing different directions as they would do in a social setting.

Nevertheless, in Egyptian movies, even if, as Dougherty (2005) states, many dance numbers were actually representations of dance on stage, there are many representations of dance in different settings.

For example, there are many dance scenes during weddings or at nightclubs with the dancer performing amongst the tables.

While in some of these performances the dancer faces the camera, often the camerawork tries to present the dancers from different angles as well, in a way that is similar to what a spectator in a club or wedding setting would see the dancer.

Overall, in my analysis, I tried to always be aware of how being part of a film would influence the dance.

Using Laban Analysis for Non-Western Danmce

Another consideration focuses on the use of Laban analysis for dance forms that are not Western. Johnson Jones (1999), for instance, points out that Labanotation, although useful for notating African dances, is considered limited as it fails to represent elements that are necessary for African dance’s interpretation, such as empathy and storyline.

Similarly, Sklar (2006, p. 103) drawing on the dance critic Marcia Siegel, acknowledges that Laban analysis is biased towards extremes (i.e. tends to ignore movements that, for example, are neither quick nor sustained) and tends to emphasize Western aesthetic categories, such as ‘shape and spatial design, with little attention given to rhythm, interaction, continuity and change’.

Moreover, Sklar (ibid.) adds, Laban analysis does not cover ‘all possible kinds of vitality’ nor ‘social interaction or cultural constructions of meaning’.

Nevertheless, Sklar (ibid.) acknowledges that the Laban system is the best system we have, for the moment, to capture qualitative elements of movement that go beyond shapes and patterns.

With this in mind, I used Laban analysis as a tool to capture some of the feelings and energy of the movements of Egyptian raqs sharqi, whilst being mindful that Laban analysis does not cover everything.

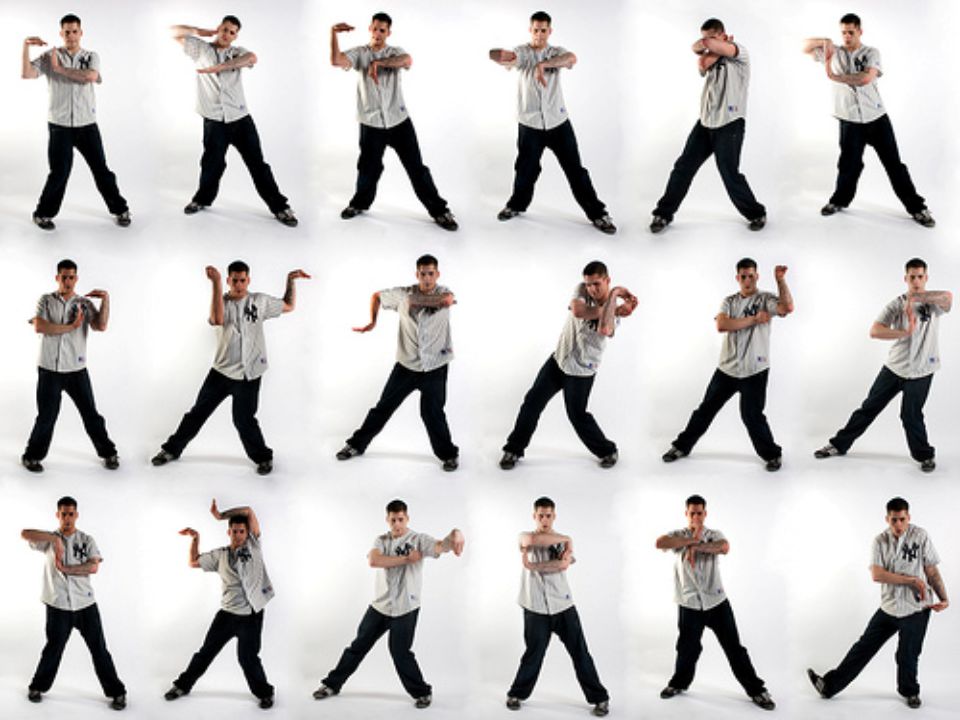

By analysing videos and using Laban analysis, I tried to overcome what Farnell (1994, p. 929) laments as being a ‘stumbling-block with regard to Western ways of “seeing” or not seeing human body movement’ by representing it only through a series of static images such as ‘photographs, sketches, diagrams, or positions of limbs plotted on a two dimensional graph’.

Studying Raqs Sharqi (Egyptian Style Belly dance) as a Non-Egyptian

The last point I would like to cover here is the fact that, although I have been practicing Egyptian raqs sharqi for over 15 years, I am not Egyptian and I do not speak Arabic.

According to Farnell (1999, p. 147), it is not possible to understand a movement system without an understanding of the spoken language as ‘human beings are language users, and the mind that uses spoken language does not somehow switch off when it comes to moving’.

Thus, Farnell (ibid.) argues, the way in which we think through language influences the way we move, and not acknowledging this means perpetuating the Cartesian body/mind division.

While I accept Farnell’s (1999) argument, I would argue that having practiced Egyptian Raqs sharqi for many years and having trained often with Egyptians who also communicated in words (even if in English) their understanding of the dance, helps my understanding of it.

There are limitations though, as my being an Italian who lives in the UK will always influence my way of interpreting any dance system.

Nevertheless, this thesis focuses on the international and transcultural dimensions of Egyptian Raqs sharqi. Thus, a transcultural influence in its analysis is not entirely out of place.

Footnotes

1 – I did not use morphokines, as kinemes and morphokines are usually indistinguishable in raqs sharqi (Table 9).

Next Page >> Texts and interviews analysis techniques.

Valeria

Hi – I’m Dr Valeria Lo Iacono and I am a dance researcher with a PhD in dance as a form of living heritage. I also teach belly dance and love to travel to discover new dances around the world. I have worked also as an academic and in the UK and in Korea. Thank you for visiting my site.

Dance interpretation of music in a choreographic work

Key words: ballet, piece of music, music, musical material, dance art, choreographic piece, interpretation, piece, stage, dance.

Human life is beautiful and diverse, it is filled with a variety of feelings and emotions. Birdsong, rain, wind, the sound of the surf, the light of the moon, the whisper of a loved one, the scent of flowers - all these circumstances affect our emotional state. One of the most influential factors is music. Music touches the most subtle strings of the human soul, changes the perception of the world, mood; music dominates our emotions, and, according to some scientists, can even overcome physical pain. It can make us cry or laugh, give us the opportunity to feel unusual tenderness, or arouse anger or resentment in us. With its rhythm, variety of melodies, dynamics and harmony, music conveys to us an endless range of feelings.

One of the most influential factors is music. Music touches the most subtle strings of the human soul, changes the perception of the world, mood; music dominates our emotions, and, according to some scientists, can even overcome physical pain. It can make us cry or laugh, give us the opportunity to feel unusual tenderness, or arouse anger or resentment in us. With its rhythm, variety of melodies, dynamics and harmony, music conveys to us an endless range of feelings.

Few talented people can bring their skill in composing music to the level of art. And each such master gives a piece of himself, his soul to compose a work. This is what the English writer Samuel Butler says about the authorship of the work: “Any human creation, whether it be literature, music or painting, is always a self-portrait.”

And the perception of composed works is even more individual, since there are millions of times more viewers and listeners than authors, and each viewer is a person with his own view and perception. Each person feels art, in particular music, in their own way. Listening to it, new thoughts are born in a person, original images, sensations arise, and then, we want to become co-authors of a musical work, and we begin to sing, compose poetry, move, dance, talking about our feelings and experiences in our own way, so new ones are born. arts - song, poetry, dance ...

Each person feels art, in particular music, in their own way. Listening to it, new thoughts are born in a person, original images, sensations arise, and then, we want to become co-authors of a musical work, and we begin to sing, compose poetry, move, dance, talking about our feelings and experiences in our own way, so new ones are born. arts - song, poetry, dance ...

Dance is one of the oldest forms of art, which also has a huge influence on the human soul. Dance is an expression of thoughts, feelings, beauty, emotions through movement, plasticity of the body. The emergence of dance in its finished form would not have been possible without music. It enhances the expressiveness of dance plasticity and gives it an emotional and rhythmic basis. Dance art is originally synthetic, because it does not exist outside of music [1, p. 89].

Listening to music, thoughts are born in us, and we begin to convey the meaning of this music through our sensations, understanding with the help of our physical and plastic abilities. Listening to the same piece of music, each choreographer has his own, individual ideas and choreographic images, each director interprets the musical material in his own way, resulting in works that are not similar to the works of other choreographers. According to the definition of I. M. Yarmolsky, “interpretation is (from Latin Interpretation - clarification, interpretation) - an artistic interpretation by a performing musician (singer, instrumentalist, conductor or chamber ensemble) of a musical work in the process of its performance. In the broad sense of the word, to a certain extent, the verbal description of the work is also an interpretation” [3, p.57].

Listening to the same piece of music, each choreographer has his own, individual ideas and choreographic images, each director interprets the musical material in his own way, resulting in works that are not similar to the works of other choreographers. According to the definition of I. M. Yarmolsky, “interpretation is (from Latin Interpretation - clarification, interpretation) - an artistic interpretation by a performing musician (singer, instrumentalist, conductor or chamber ensemble) of a musical work in the process of its performance. In the broad sense of the word, to a certain extent, the verbal description of the work is also an interpretation” [3, p.57].

An outstanding example of different interpretations of the same musical material is Aram Khachaturian's ballet Spartacus. A vivid example of the love of freedom and heroism of the Italian people found a response in the heart of Aram Khachaturian, perhaps after visiting the Colosseum and the Appian Way, where the fateful battle of the insurgent people with the Roman legionaries once took place. The ballet was written by the composer in 1950 and immediately gained extraordinary popularity among music lovers. Unusual bright music touched the most delicate strings of the soul, caused a storm of emotions and pushed many ballet masters to create their original, large-scale, author's works (only in the Soviet Union, the ballet had 16 stage versions, not counting several productions abroad).

The ballet was written by the composer in 1950 and immediately gained extraordinary popularity among music lovers. Unusual bright music touched the most delicate strings of the soul, caused a storm of emotions and pushed many ballet masters to create their original, large-scale, author's works (only in the Soviet Union, the ballet had 16 stage versions, not counting several productions abroad).

Today we will try to consider the interpretation of the music of A. Khachaturian's ballet "Spartacus" by great masters, such as Leonid Yakobson (1956), Igor Moiseev (1957), Yuri Grigorovich (1968).

The performance has an iron compositional and dramatic logic. Each monologue connects one picture with another, growing from the previous one into the next one, the action develops continuously and dynamically [2, p. 117]. Comparing the productions of these authors, we see a kind of choreographic style, the originality of the choreographer's decision and the individuality of the plastic interpretations of each artist.

When constructing the dramaturgy of a choreographic work, minor adjustments can be made to the musical score, that is, the choreographer has the right to change musical numbers, stop parts of the musical work. Spartacus by Leonid Yakobson was staged on December 27, 1956 for the stage of the Kirov (now the Mariinsky) Theatre. The ballet consisted of 4 acts and 9 scenes.

"Spartacus" by Leonid Yakobson was created according to all the canons of grand style, the production was considered innovative for its time. Amazing music by Aram Khachaturian, it combines heroism, tragedy and lyricism. From an interview with the great Maya Plisetskaya: “While composing the ballet, Yakobson used every musical moment, followed the composer from number to number - violent musical sophistication, whimsical and decorative music demanded staging luxury and polyphonic choreographic fantasy.” The performance was a real sensation for its time. When staging the ballet, Leonid Yakobson abandoned the genre of strict classical ballet, instead introducing plastic dance and pantomime, which was very new and unusual.

Thus, the peculiarity of the "Jacobsonian Spartacus" was the rejection of pointe shoes in women's dance and the construction of dance vocabulary in the style of free plastique. Another feature was the costumes of the performers - they were dressed in antique tunics and sandals to convey the atmosphere of the ancient world as much as possible.

A peculiar reading of the music by Aram Khachaturian was seen by the audience in the production of Igor Moiseev. Spartacus by Igor Moiseev was staged on March 12, 1958 at the Bolshoi Theatre. In the interpretation of Moiseev, in ballet, mass dances, which are usually the entourage of soloists, were of great importance, but with Moiseev, the masses are "the leading independent hero."

Moiseev's interpretations are characterized by brightness and freedom in creating figurative characteristics, the absence of traditional "stamps" and "self-quoting". The choreographer brought to the stage an everyday gesture, capacious and natural, clothed in a strict stage form. He did not use ready-made combinations taken from any dance system, but followed the path of the 20th century ballet theater reformers Gorsky and Fokine, creating newly invented vocabulary and achieving exceptional expressiveness of the human body in it [4].

He did not use ready-made combinations taken from any dance system, but followed the path of the 20th century ballet theater reformers Gorsky and Fokine, creating newly invented vocabulary and achieving exceptional expressiveness of the human body in it [4].

Unfortunately, "Spartacus" by Igor Moiseev was not captured in video recordings, but was only preserved in the memory of performers and balletomanes.

The ballet created by Yuri Grigorovich on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater had the happiest fate. Created by Yuri Nikolayevich in 1968, it has been going on for more than 40 years and delights the audience not only on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater, but also on all the main ballet stages of the world. The ballet consists of 3 acts, each with 4 scenes and 3 monologue episodes.

If both Yakobson and Moiseev built Spartacus more on pantomime, in a semi-acting, characteristic role, then in the interpretation of Grigorovich, the ballet was based on classical choreography. The choreographer “read” the brilliant music of Aram Khachaturian in a new way, it was classical dance that reigned in all monologues, duets, mass scenes. For the first time, the main characters danced, for them Grigorovich composed a detailed choreography, technical, virtuoso, powerful, with deep thought.

The choreographer “read” the brilliant music of Aram Khachaturian in a new way, it was classical dance that reigned in all monologues, duets, mass scenes. For the first time, the main characters danced, for them Grigorovich composed a detailed choreography, technical, virtuoso, powerful, with deep thought.

The famous critic VV Vanslov could not pass by such an outstanding work as "Spartacus" staged by Y. Grigorovich. In his book "Choreographer Yuri Grigorovich" he finds very accurate and correct words about this amazing production: "Khachaturian's music is distinguished by high figurative qualities. She is characterized by emotional pathos, romantic elation of tone, generosity of melodic, harmonic and orchestral colors. In the music of "Spartacus" episodes alternate both festive and tragic, heroic and dramatic images collide, subtle lyrical statements are replaced by monumental epic scenes. The pompous and heavy themes of Rome and the heroic-dramatic music of the gladiators, the pompously loud theme of Crassus and the noble, courageous theme of Spartacus, the sensually sultry adagio of Crassus and Aegina and the gentle, poetic duet of Spartacus and Phrygia - ballet is saturated with such contrasts. They express the depth of the main dramatic conflict" [2 p. 116].

They express the depth of the main dramatic conflict" [2 p. 116].

The symphonism of Khachaturian's music lies in the generalization of its emotional dramaturgy. Music does not illustrate events, but carries their inner meaning. That is why it develops according to the laws of large symphonic forms (based on the thematic development, waves of rises and falls, etc.) and acquires a figurative scale [2 p. 117].

In "Spartacus" Grigorovich embodied all the best he achieved in art: the depth and scale of the philosophical concept, consistent, logically built dramaturgy, original and impeccably perfect composition, strong characters obsessed with passions. And all this in a generous spill of the dance element, in a multitude of innovative finds - in the vocabulary and forms of dance art, in the highest triumph of symphonic dance [2 p. 115].

So, we tried to consider the interesting topic “interpretation of music in a choreographic work”, to touch on the secrets of the great choreographers of the 20th century, who, with their talent, a special sense of music, managed to create their own original solutions that have become masterpieces of world classical ballet. And every artist of dance, ballet, if he subtly and deeply understands music, can and should create his own original author's works that will always delight, bring to tears and delight the grateful audience.

And every artist of dance, ballet, if he subtly and deeply understands music, can and should create his own original author's works that will always delight, bring to tears and delight the grateful audience.

Literature:

- Blazis K. Dances in general / K. Blazis. - St. Petersburg: Lan: Planet of Music, 2008. - 352 p.

- Vanslov V. V. Choreographer Yuri Grigorovich / V. V. Vanslov. — M.: Teatralis, 2009. — 232 p.

- Petit R. I danced on the waves / R. Petit. - M .: ID Fluid, 2008. - 352 p.

- https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/balety-na-istoricheskuyu-temu-v-tvorchestve-i-a-moiseeva-salambo-i-spartak

Basic terms (automatically generated) : ballet, music, piece of music, musical material, dance art, choreographic piece, interpretation, staging, piece, scene.

Interpretation of folklore choreography into folk stage dance

“Interpretation of folklore choreography

into folk stage dance. Karelian Folklore”

Karelian Folklore”

The relevance of preserving the folklore heritage is of great importance. Today, in the conditions of complete urbanization of society, in the age of high technology, it is sometimes worth stopping, looking back and plunging into the history of your people, their traditions and customs.

The exact definition of the term "folklore" is difficult, because this form of folk art is not immutable and ossified. Folklore is constantly in the process of development and evolution

The term "folklore" was first introduced by scientist William Thomas in 1846 to refer to both artistic (legends, dances, music) and material (housing, utensils, clothing) culture of the people

Folklore choreography is the achievement of our people. Consider aspects of folk dance. Folk dance is one of the most widespread and ancient types of folk art. It arose on the basis of human labor activity. Folk dance has always been closely connected with the labor calendar of the peasants, the agricultural year (sowing, harvesting). It is also associated with various aspects of everyday life, customs, rituals, beliefs (births, weddings, games). In the dance, the people conveyed and continue to transmit their thoughts, feelings, mood, attitude to life phenomena.

It is also associated with various aspects of everyday life, customs, rituals, beliefs (births, weddings, games). In the dance, the people conveyed and continue to transmit their thoughts, feelings, mood, attitude to life phenomena.

Consider the definitions of folk and folklore dances:

Folk dance is a dance that is performed in its natural environment and has movements, rhythms, and costumes specific to the area.

Folklore dance is a spontaneous appearance of feelings, moods, emotions. A feature of folklore dance is that it is performed for oneself, and then for the viewer.

How to recreate the color of folk dance on the stage today, how to make it interesting for the modern audience? This question is asked by many choreographers who have folk dances in their repertoire, both in amateur and professional groups.

I.A. Moiseev is a great choreographer, founder of the State Dance Ensemble. This is the world's first professional choreographic group engaged in the artistic interpretation of the dance folklore of the peoples of the world.

The task set by I.A. Moiseev in front of the artists, was to creatively process and present on stage the samples of dance folklore common among the people. To this end, the ensemble members went on folklore and ethnographic expeditions around the country, where they searched for, studied and recorded disappearing dances, songs, rituals. 9Ol000 two

musical instruments

- Folk Instrument Orchestra

- Availability of the melody for hearing and performance

In order to preserve the identity of the nationalities inhabiting the northwestern region of the country, we must know and preserve all the knowledge of the folklore of the ethnogroups of the Leningrad region. Small ethnic groups inhabiting the Leningrad region are represented by the following peoples:

Finns - 4,366 people, Vepsians - 1380 people, Karelians - 1345 people, Vods - 33 people.The features of the folklore choreography of the above ethnic groups are very close: a common language, costumes have something in common, musical works are performed on the national instruments kantele, youhiko; general drawings of dances, similar movements in dance.

Vocabulary of the choreographic language of these peoples is simple and accessible to performers: steps, footsteps, jumps, gallops, percussion.Dance patterns of the Karelians and peoples of Scandinavia are simple:

“circle” (in Karelian “kruuga”), figure “shen” (in Karelian “shinka”).Some regions of Karelia have their own dances with a peculiar manner of performance.

In the northern regions of the republic, dances of a calm, strict nature are widespread. Even in the dance “It's time for us to have fun”, young people have fun with restraint. A typical example of a round dance dance is “Moloditsa”, in which the girls smoothly and calmly “swim” in a circle, at the same time they calmly knit on knitting needles, and the young men each follow the girl of their couple, trying to attract her attention.In the southern regions (Olonets, Petrovsky) dances are more lively and mobile. The cheerful dance “Ivan Poika” (Ivan's Son) is very common there, as well as various quadrilles

The dances of the Vepsians, one of the nationalities living in the republic, are distinguished by their originality.

Veps dances include: "Eight", "Kruuga". In character, they are close to the dances of the southern peoples, they are characterized by great mobility, liveliness, and sometimes humor.

Veps dances include: "Eight", "Kruuga". In character, they are close to the dances of the southern peoples, they are characterized by great mobility, liveliness, and sometimes humor. Ease and softness of movements, severity of lines, lyricism are the hallmarks of all Karelian dances.

The spatial pattern of the dances is clear and uncomplicated. The main movements are simple and intertwining steps, light running and light jumps, gallop, calm polka.

The dancers are alien to both complex, pretentious and violent temperamental movements. The body of performers in most of the dances is straight, strictly pulled up. The polite, somewhat ceremonial attitude of the young man towards the girl is combined in the dance with the graceful grace and restraint of the girl.The national culture of Karelia is closely connected with the names of choreographers of folk dances - these are Viola Malmi, Helmi Malmi, Vasily Kononov, Viktor Gudkov. All these great people at different times were the leaders of the State Ensemble "Kantele".

They were pioneers in the preservation and study of Karelian folklore, they began to interpret folklore dance on stage.

They were pioneers in the preservation and study of Karelian folklore, they began to interpret folklore dance on stage.

The concert programs of the ensemble "Kantele" were formed in accordance with the trends of the times. But the main task has always been to preserve the richest cultural heritage of the Karelian people. The repertoire was based on arrangements of Veps, Ingrian, Karelian, Russian, Finnish folk songs and dances, author's music, instrumental pieces by professional and amateur composers of Karelia and Russia, arrangements of vocal and instrumental works of Russian and Western European classics.Today, the Kantele Ensemble's repertoire includes choreographic numbers staged by the first choreographers of the group - Letka-Enka,

Vepska Krug, Six in Threes, Dance with Spoons, Ristu-Contra.

Musical works are performed on the Kantele instrument, composed by V. Gudkov back in the 30s of the 20th century."Finnish Polka", staged in the 1950s by Helmi Malmi at the State Dance Ensemble named after I.

Moiseev, is still in the repertoire of the legendary ensemble today.

Moiseev, is still in the repertoire of the legendary ensemble today. H.Malmi and V.Malmi made an invaluable contribution to the development and preservation of national folklore. They constantly held seminars, lectures, workshops on the dance heritage of Karelia.

The exoticism of Karelian culture, the magical sound of traditional instruments, the colorful costumes, restrained lyrics and the fervent spark of the national music of Karelia, all these are inseparable components of ethnic style that allow a person of any age and status to feel a harmonious connection with the origins of Karelian folklore.

Today, when the national question and the concept of “tolerance” are very pronounced, it is necessary to introduce people from childhood to the heritage, to the origins of folk art. Then a generation of young people will grow up who will understand, appreciate the beauty of national cultures, and respect the ethnic and cultural differences of peoples.

References:

- Antipenko N.

.

- Antipenko N.