How to do the highland sword dance

The History and Tradition of Highland Dancing

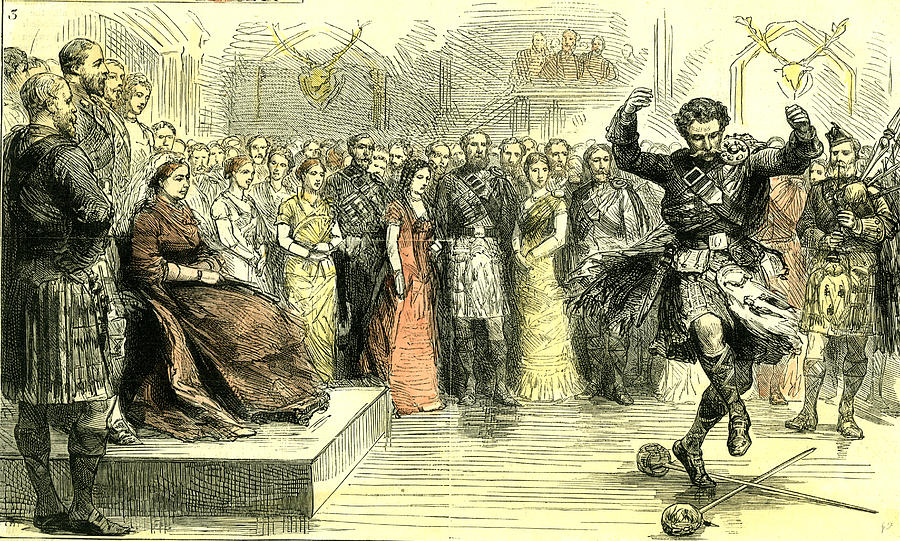

Perhaps nothing captures the spirit of Scottish culture better than the sight of Highland dancing being performed at some Highland gathering in some far flung corner of the world. This sophisticated form of national dancing has been spread by Scottish migrants across the world and competitions are now regularly organised in Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and the United States. Whilst the majority of dancers now entered into these competitions are female, the roots of these ritualistic dances lay with warriors imitating epic deeds from Scottish folklore.

According to tradition, the old kings and clan chiefs used the Highland Games as a means to select their best men at arms, and the discipline required to perform the Highland dances allowed men to demonstrate their strength, stamina and agility.

Although likely to date back to a much earlier period, the first documented evidence of intricate war-dances being performed to “the wailing music of bagpipes” was at the second marriage of Alexander III to his French bride Yolande de Dreux at Jedburgh in 1285.

It is also said that Scottish mercenaries performed a sword dance before the Swedish King John III at a banquet held at Stockholm Castle in 1573. The dance was apparently part of a plot to assassinate the king, the weapons necessary to complete the dastardly deed ‘just happened’ to be a natural prop for the festivities. Luckily for the king the signal was never given to implement the plan.

A reception given in honour of Anne of Denmark at Edinburgh in 1589 included a “Sword dance and Hieland Danses”, and in 1617 a sword dance was performed before James VI. Still later in 1633, the Incorporation of Skinners and Glovers of Perth performed their version of the sword dance for Charles I whilst floating on a raft in the middle of the River Tay.

It was after the Battle of Culloden in 1746 that the government in London attempted to purge the Highlands of all unlawful elements by seeking to crush the rebellious clan system. An Act of Parliament was passed which made the carrying of weapons and the wearing of kilts a penal offence. The Act was rigorously enforced. So much so it seems that by the time the Act was repealed in 1785, Highlanders had lost all enthusiasm for their tartan garb and lacked the main prop required to perform their sword dances.

The Act was rigorously enforced. So much so it seems that by the time the Act was repealed in 1785, Highlanders had lost all enthusiasm for their tartan garb and lacked the main prop required to perform their sword dances.

The revival of Highland culture was greatly boosted when Queen Victoria discovered the road north and recognised first-hand, the magnificence of Scotland for herself. This revival saw the beginnings of the modern Highland games, with of course, Highland dancing forming an integral part.

Primarily to make judging easier however, the selection of dances being performed were gradually narrowed down over the years and decades that followed. The result of this was that many traditional dances simply got lost, as they were no longer required for competition purposes. In addition, over the years Highland dancing has moved from being an exclusively male pursuit, to one that today includes more than 95% of female dancers.

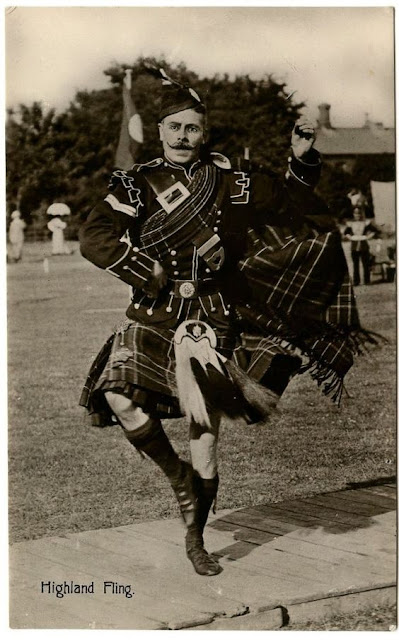

As far as competitive Highland dancing is concerned, until 1986 only four standard dances remained – The Sword Dance (Gille Chaluim), The Seann Triubhas, The Highland Fling and The Reel of Tulloch. Like many other dance traditions Highland dancing has changed and evolved over the years, integrating elements that may have their roots set in centuries old tradition with elements that are much more modern.

Like many other dance traditions Highland dancing has changed and evolved over the years, integrating elements that may have their roots set in centuries old tradition with elements that are much more modern.

Some of the legends associated with today’s modern dances include;

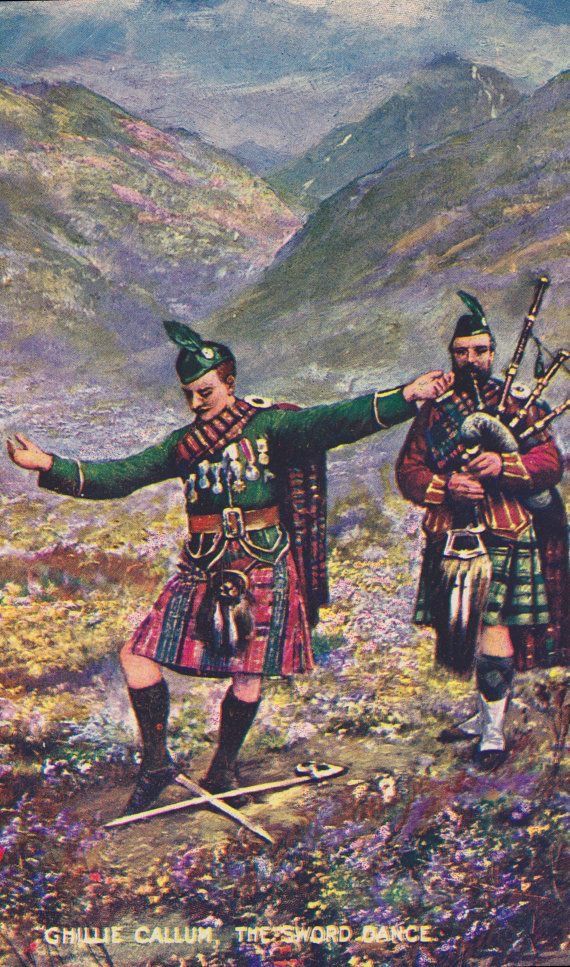

The Sword Dance (Gille Chaluim – Gaelic for “the servant of Calum”) – One story said to originate from the times of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, recalls that when King Malcolm III (Canmore) of Scotland killed a fellow chieftain in battle, he celebrated by dancing over his own bloody claymore crossed with the sword of his enemy. Yet another story tells that a soldier would dance around and over crossed swords prior to battle; should his feet touch the blade during the dance however, then this was considered an ill omen for the following day. Another and more practical explanation is that the dance was simply an exercise used to develop and hone the nibble footwork required to stay alive in sword play.

The Seann Triubhas – Gaelic for “old trousers” – Pronounced “shawn trewus”, the dance is romantically associated with the highlander’s disgust at having the wear the hated Sassenach trousers that they were forced to wear when the kilt was banned following the 1745 rebellion. The initial slow dance steps involve lots of leg shaking; symbolising attempts to shed the hated garments; the final faster steps demonstrating the joy of returning to the kilt when the ban ended in 1782.

The Highland Fling – One legend associates it as a warriors dance of triumph following a battle. It was supposedly danced over a small round shield, with a spike projecting from the centre, known as a Targe. Yet another legend links the dance to a young boy imitating the antics of a stag rearing and wheeling on a hillside; the curved arms and hands representing the stag’s antlers.

The Reel of Tulloch (Ruidhle Thulaichean) – It was supposedly on one cold morning in the village of Tulloch in north-east Scotland, that many years ago the congregation were waiting for the minister to let them into the church. To keep warm the people began to stamp their feet and clap their hands, and when someone started to whistle a highland tune the whole developed into a lively dance. A set perhaps, later stolen by the cast of Fame! A more gruesome story however, links the dance to a game of football said to have been played by the men of Tulloch with the severed head of an enemy.

To keep warm the people began to stamp their feet and clap their hands, and when someone started to whistle a highland tune the whole developed into a lively dance. A set perhaps, later stolen by the cast of Fame! A more gruesome story however, links the dance to a game of football said to have been played by the men of Tulloch with the severed head of an enemy.

Ghillie Callum - Highland Bagpipes traditional tunes’ stories by Stephane BEGUINOT

Back to menu Score Next tune

GHILLIE CALLUM (sword dance)

HISTORY

Scotland has an enormous variety of "Sword Dances" including the Argyll Broadswords, the Jacobite Sword Dance, the Clansmen Sword Dance, the Broadswords of Lochiel, the Lochaber Broadswords, the Elgin Long Sword Dance and the Papa Stour to name but a few.

| But, today, the term "Sword Dance" invariably refers to "Ghillie Callum" performed by a solo dancer over two swords, laid as a cross, on the ground. "Ghillie Callum (1)" is one of the oldest and most famous traditional Scottish dances. This ancient dance of war of the Scottish Gael is said to date back to King Malcolm Canmore (2). After defeating one of MacBeth’s generals at the Battle of Dunsinane in 1054, Malcolm placed his sword over that of his enemy and performed a dance over and atop them symbolizing both his victory and his martial dexterity, a quality admired in leaders at this period. |

(1) The name Ghillie Callum means Servant of Malcolm. Originally, ghillie was the name given to the young man [the literal and original meaning of "gille" is "youth" or "lad." It is cognate with (and derived from) the Irish "giolla."] who would guide the Highland chiefs on hunting and fishing expeditions. It was later generalized and used in a derogatory way by lowlanders to describe the men servants who always accompanied Highland chiefs. Ghillies are also a soft shoe without a tongue, worn for traditional Scottish Highland Dances. They are usually black in color with decorative laces and slightly larger than the foot as they are often worn with the thick socks of the traditional Highland garb.

(2) Malcolm Canmore (Canmore means great head) was the illegitimate son of King Duncan of Scotland whom Macbeth (about whom William Shakespeare wrote his famous play), the Earl of Moray, defeated and killed in the year 1040 and took the crown of Scotland. Malcolm fled to England and took refuge there, dreaming always of returning to Scotland and reclaiming his father’s throne. After long years Malcolm went north with an army and defeated Macbeth at Dunsinane Hill (1054). Malcolm then gained control of the southern part of Scotland and spent the next three years pursuing Macbeth, who fled to the north. With the support of the English King, Malcom defeated and killed Macbeth at Lumphanan in Aberdeenshire in 1057. Lulach, Macbeth’s stepson, took over the throne but Malcolm killed him also in the following year. |

Malcolm Canmore was crowned Malcolm III in 1058. Malcolm founded the dynasty of the House of Canmore which lasted 200 years until the House of Stewart. By his first marriage to Ingebjrg (her mother’s father was a brother of the Norwegian kings Olav Haraldsson and Harold Hardrada) he had two sons, Duncan II (who became king after Malcolm) and Donald. Following Ingebjrg’s death, around 1069, he married Margaret, the sister of Edgar Atheling would have become King of England if William the Conqueror from Normandy had not over-run the country. By this marriage there were six sons, three of whom (Edgar, Alexander and David) would become king. Following Ingebjrg’s death, around 1069, he married Margaret, the sister of Edgar Atheling would have become King of England if William the Conqueror from Normandy had not over-run the country. By this marriage there were six sons, three of whom (Edgar, Alexander and David) would become king.The large number of English exiles who had gathered in the court and raids by Malcolm into Northumbria and Cumbria became a concern to the English King William who marched North. Malcolm was forced to submit and sign the Treaty of Abernethy in 1071 and agree to his son Duncan becoming a hostage in England. Even so, Malcolm made two more raids into England in 1079 and 1091, and again he lost and had to submit to the English king. Malcolm led a final incursion in 1093. This led to his defeat and death at Alnwick. His son and heir Edward died in the same battle and Queen Margaret died in Edinburgh Castle, four days later. |

His brother Donald III succeeded him as the Scottish nobles (reacting with the anglophile tendency of the reign of Malcolm) preferred to return to the tradition of tanistrie [a succession law practiced by the Celts where the successor of a king or chieftain must be selected from collateral relatives (brothers , cousins, nephews) rather than from its direct descendants. It allowed to choose a powerful man of adulthood, but it was often a source of violent conflict in case of disagreement, since it did not specify a hierarchy among potential successors].

It allowed to choose a powerful man of adulthood, but it was often a source of violent conflict in case of disagreement, since it did not specify a hierarchy among potential successors].

THE DANCE

Records of this dance are obscure until the late Sixteenth Century where male dancing proficiency was as much esteemed as male athletic prowess, in Scottish Highland community. This demonstrates a change from dance as ritual to dance as exercise to strengthen legs and improve agility.

| Ghillie Callum is first recorded as a competition dance in 1832. The dance performed at the Highland Games today typically comprises one dancer performing over two crossed swords and includes two or three slow steps followed by one or two quick steps (the dancer claps to give her a boost and to tell the bagpiper to speed up the tempo) and focuses on technical accuracy and the precise placing of the feet. Because the dancer is representing a warrior, the head must be proud and poised and the steps executed to give an appearance of strength, control and conviction. |

In the first step the dancer performs the steps outside the sword or "addresses" the sword (It infers that the swords have 'personality'. So the dancer is requesting permission to dance within the swords by executing the first step correctly without disturbing the swords). Subsequent steps are danced over the crossed blades, but notice that once inside the blades, the dancer never dances with his back turned to the swords - only a fool would turn his back on a weapon.

| It requires tremendous dexterity not to displace the swords. But nowadays, nevertheless following the tradition, if the dancer touched the sword he would not be wounded the next day but disqualified or 5 points penalised (depending of the dancer level) if the sword is touched but not displaced. |

The dancer progresses in an anticlockwise direction ("widdershins" or the way of the witches) around the swords but the direction of travel as late as 1880 was clockwise. A description of the clockwise dance is given in "Book Of The Club Of The True Highlander",1881. One example of a "clockwise" step can be found in the form of the Third Step of "The Jacobite Sword Dance" collected by Mrs. M. I. MacNab.

A description of the clockwise dance is given in "Book Of The Club Of The True Highlander",1881. One example of a "clockwise" step can be found in the form of the Third Step of "The Jacobite Sword Dance" collected by Mrs. M. I. MacNab.

The origins of the convention of progressing anticlockwise lie in the fact the men were wearing a sword on their left hip (the normal scabbard position for right-handed person). To move in this way was easier as they were less encumbered. The same occurs in couples where the male dancer holds his partner with the right hand to prevent her dress caught in the scabbard, and stands in the center of the circle when dancing round the ballroom dance floor to avoid his scabbard clashing with spectators. So the only possible move for such position (as Ladies cant promenade backwards as the length of their dress would become caught beneath their feet) is an anticlockwise one.

THE TUNE

The tune Ghillie Callum can be traced back to 1768 and is probably connected to an old kissing dance - "Babbity Bowster".

This courting ritual dance, almost always performed as the last dance of the evening, shows the substitution of a magic wand or a stick for a sword. In the Central and West Highlands and the Western Isles, the leader would twist a handkerchief into a rope, lay it on the floor like a sword, and do a few steps of the Gille Calum sword dance in a clockwise direction. The words of the dance-song Gille Calum, about getting a sweetheart and a wife, apply more aptly to a kissing dance than to a combat dance. The tune is replaced by The White Cockade when a white handkerchief replaced an actual sword or by The blue bonnet when a blue bonnet was substituted for the handkerchief.

This courting ritual dance, almost always performed as the last dance of the evening, shows the substitution of a magic wand or a stick for a sword. In the Central and West Highlands and the Western Isles, the leader would twist a handkerchief into a rope, lay it on the floor like a sword, and do a few steps of the Gille Calum sword dance in a clockwise direction. The words of the dance-song Gille Calum, about getting a sweetheart and a wife, apply more aptly to a kissing dance than to a combat dance. The tune is replaced by The White Cockade when a white handkerchief replaced an actual sword or by The blue bonnet when a blue bonnet was substituted for the handkerchief. The earliest record of the tune is in David Young’s 1734 Drummond Castle Manuscript Gillie Callum which retained its popularity into the next century, and J.S. Skinner, who was a dancing master as well as a celebrated violinist, taught the dance at such places as Elgin and Balmoral. He included the tune later in his collection The Scottish Violinist, under the title "Sword Dance. " The first definite reference in print appears in 1804.

" The first definite reference in print appears in 1804.

GHILLIE CALLUM SONG LYRICS

After re-acquiring his father’s kingdom, Malcom later ascended the throne, as King Malcolm III and incurred the displeasure of the Highlanders by marrying a Saxon princess (Margaret) which led to the change of the court language from Gaelic to English; the shifting of his court from its ancient seat (Dunstaffnage Castle) in Argyllshire, to Dunfermline; and the addition to the coinage of a very small coin, the bodle, or two pennies Scots, equal in value to the third part of our halfpenny.

It was called in Gaelic bonn a sia, or coin of six, being the sixth part of a shilling Scots, which was so small as to be contemptible in the eyes of his Highland subjects.

This last action resulted in the heroic Sword Dance Gille Caluim being danced to music accompanied by verses ridiculing the new coin where Ghillie Callum is Callum’s tax-gatherer (an odious official everywhere) immortalized in melody, while the traditional story is well nigh forgotten.

Nevertheless, only the picturesque Callum, the agile highlander, has survived to the present day.

There are puirt-a-beul words to the tune (a bawbee was a Scottish halfpenny. The word means, properly, a debased copper coin, valued at six pence Scots):

| Chorus Gille-Caluim twa pennies a bodle I can get a lass for naething (sweetheart) Chorus I can get a wife for tuppence, Chorus | Refrain Ghillie Callum et sa piécette à deux sous Je peux avoir un amour de fille pour rien Refrain Je peux prendre épouse pour deux pennies Refrain | Luinneag Gille-Caluim : da pheighinn Gheibhinn leannan gun dad idir Luinneag Gheibhinn bean air da pheighinn Luinneag |

VIDEO SUGGESTION(S)

| Traditional Highland sword dance | Sword Dance, Las Vegas Tattoo 2011 |

| Sword dance - Primaries | Sword dance tutorial |

| Sword - Cowal 2014 - Rebecca Thow | Sword - Cowal 2014 - Kaylee Finnegan |

- This page has been accessed 24627 times -

Copyright © 2009-2021 Stéphane BÉGUINOT, All Rights Reserved.

Scottish sword dancing

Sword dancing performance in Scotland folklore has been recorded since the 15th century.

Related customs are found in Welsh and English. Morris Dance in Austria, Germany, Flanders, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Romania.

- In Gilly Cullum or "Scottish sword dance": the dancer crosses two swords on the ground in an "X" or "+" shape and dances around and within 4 quarters of it.

- The Dirk dance includes one or two dancers, each holding a dagger. [1] [2]

Swedish king John

The history of the Scottish sword dance

As part of the traditional Scottish intangible heritage, the sword dance was recorded as early as the 15th century. At that time in the Scottish royal court it was generally recognized as a war dance with some ceremonial meaning. Old kings and clan chiefs organized the Highland Games as a method of choosing their best fighters, and the discipline required to perform the Highland dances allowed men to display their strength, endurance, and agility. The earliest reference also mentions that the dance is often accompanied by bagpipe music. The basic rule requires the dancer to cross two swords on the ground in an "X" or "+" shape and dance around and within 4 quarters of it. [3]

[3]

The earliest mention of these dances in Scotland is in Scotichronicon , compiled in Scotland by Walter Bauer in the 1440s. Excerpt with Respect Alexander III and his second marriage to the French lady Yolande de Dreux at Jedburgh in Roxburghshire October 14, 1285 others doing superb martial dances with intricate weaves. Behind him was a figure, regarding which it was difficult to decide whether it was a person or a ghost. It seemed like he was gliding like a ghost rather than walking. Just as he seemed to be out of sight, the whole frantic procession stopped, the song ceased, the music ceased, and the dancing contingent suddenly and unexpectedly froze.

In 1573, Scottish mercenaries say they performed a dance with a Scottish sword before the Swedish king, John III, at a banquet held at Stockholm Castle. The dance, "a natural feature of the festivities", was used as part of a plot to kill the king (Mornay Plot), where the conspirators could draw their weapons without arousing suspicion. Fortunately for the king, at the decisive moment, the agreed signal was never given. [4]

Fortunately for the king, at the decisive moment, the agreed signal was never given. [4]

"Sword dances and Highland dances" were included at a reception for Anne of Denmark in Edinburgh in 1589 [5] and again for Charles I in 1633 by combining skinners and glovemakers from Perth:

His Majesty's Chair was placed on the wall next to Tai water, after which a floating stage made of wood, sheathed with birches, appeared on which, to meet His Majesty and enter, thirteen of our brothers of this vocation Glover with green caps, silver threads, red ribbons, white shoes and bells on their feet, rapier haircuts in their hands and all other insults, danced our sword dance with many intricate knots and allapallajesse, five of which were under and five above on the shoulders, three of which danced through the legs and about them drinking wine and breaking glasses. Which (thank God) was done and done without harm to anyone.

Types of sword dance

Scottish sword dancer "Jilli Cullum" in Inverness, c. 1900

1900

Many of the Highland Lost Dances were once performed with traditional weapons, including the Lochaber Axe, the broadsword, a combination of aim and cutlass, and a flail. [ need quote ]

Old Skye dance song Bualidh mi u an sa chean ( Buailidh mi thu anns a 'cheann "I'll break your head"), may indicate some form of gunplay As for music, then "break the head" was the winning blow in fights all over Britain, "the moment the blood flows an inch above the eyebrow, the old player to whom it belongs is beaten and must stop."

C.N. McIntyre North describes a clockwise rotating sword dance in his 1880 book of the True Highlanders' Club. [6] McIntyre North describes nine steps. The first step beats the rhythm to the tune of "Jilli Callioun" [sic].

Sword dance [ clarification needed ] the so-called Highland dirk dance still exists and is often associated with a sword dance or dance called "Macinorsair" ( Mac an Fhòrsair ), "Broad Sword Exercise" or "Belly" (combat dance). These dances are mentioned in a number of sources and may have been performed in various forms by the two performers in dueling form and solo. [ citation needed ]

These dances are mentioned in a number of sources and may have been performed in various forms by the two performers in dueling form and solo. [ citation needed ]

Dancing with Highland Regiments

Malagasy Envoys in Cape Town - entertainment in the Officers' Mess of the 1st Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

Regimental traditions

To prepare for the Sword Dance, the soldier must place two swords on the ground in an X shape, then he will dance an elaborate series of steps and movements between and around the swords to the sound of bagpipes. The dance itself can be performed by more than one person. This tradition of exhibition and competitive dance has survived into the 21st century. It was performed at regimental games in the mountains around 1930s. There are four swords on the dance floor in the form of a cross. The dancer then performs a series of intricate dance steps across and around the blades of the sword, keeping the back straight, the arms raised and the arms in a certain shape. For decades, this style of dance has become an integral part of the performance of the bagpipe and drum orchestra as it tours around the world. Highland country dancing (often a less formal style of dancing) was also encouraged in the regiment. [7]

For decades, this style of dance has become an integral part of the performance of the bagpipe and drum orchestra as it tours around the world. Highland country dancing (often a less formal style of dancing) was also encouraged in the regiment. [7]

Sword dance, 93rd, camped at Chobham, England, 1853.

Lochaber axe, traditional Scottish fighting weapon

In fact, the weapon in the traditional sword dance is not just the basket-handled broadsword. In The Highland and Traditional Scottish Dances, Mr. McLellan mentioned that when his father lived on Loch Fineside in Argyll, he developed a four-piece sword dance as a counterpoint to the Lochaber Dance, which was originally danced with Locaber axes. The broadsword referred to the basket-hilted sword carried by officers of the Highland Regiments, and is sometimes erroneously referred to as the Claymore, which is a large two-handed weapon. The original version of the Broadsword Dance is described in Mr. McLellan's book, and the steps, four stratspeys and one fast tempo, as well as the exercises for moving in and out of the dance scene, are simpler and less complex than those seen in some modern forms. dance. This is not the Old Thyme dance, and it is not of regimental origin. [8]

dance. This is not the Old Thyme dance, and it is not of regimental origin. [8]

Highland Regiment Dance Influence

RIT, P, Ds and D Coy with local children who put on a Highland Dancing show in Topermory, Isle of Mull culture and Highland Dancing competitions. This has increased the amount of training and intensive preparation, either by students among students attending the Pipeline Course in Edinburgh or schoolchildren from the Victorian School performing at the King's Tournament in London and the Edinburgh Tattoo Festival due to their interest in Highland dance. To inspire students to get involved, the school held special Highland dance classes. In the south of England, highland and Scottish country dancing created a wave of enthusiasm that swept through the service industry. Many officers of the Highland Brigade supported the dance and it was taught at the Joint Staff College, the Army Staff College, the Royal Naval College and the Royal Military Academy. The only "stronghold" resisting this Scottish "investment" is the R.A.F. Staff College.

The only "stronghold" resisting this Scottish "investment" is the R.A.F. Staff College.

Pipers of the 1st Battalion perform a sword dance

The Highland Dancers of Regimental Headquarters - Sergeant Oliver, Corporal, Yule and Eliott and P. Ferguson --- made notable progress at the Oban Games on 15 September. [ clarification needed ] . The Regimental Four won the Alasdair Maclean Regimental Drum Dance Challenge Cup, defeating the Gordon Highlanders and Highlanders of the Light Four. Corporal Yule won the Poltalloch Cup, presented by Colonel George Malcolm, for a non-professional dancer serving in the armed forces who received the highest aggregate score in four individual dance competitions. It was the first year of the fight for the Cup. [9]

The Official Highland Dance Council of Scotland has published its Guide to the Technique and Performance of Traditional Highland Dances, Individual and Quadruple. This is a detailed guide with illustrations of the basic positions, movements and steps. The book also discusses the organization and conduct of Highland dance competitions.

The book also discusses the organization and conduct of Highland dance competitions.

Regimental Pipe and Dance Society

The Society was formed to stimulate interest in bagpiping in the mountains, to generate enthusiasm for highland dancing and thus to raise the level of performance of both these arts in the units of the regiment. The aims of the Society are: A. To assist in the training of pipers and highland dancers in the regiment and to observe their progress throughout the regimental career. Standardize flute settings for the entire regiment. In every possible way to assist the conductors in their duties, both technical and administrative, in order to maintain the highest level of pipe playing and regimental dancing. To train judges to play the flute and dance in the interests of regimental and national competitions. The Regimental Committee, representing all battalions of the regiment, is to develop the policy of the Society. 9 The Thin Red Line Regimental Magazine of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders . GREAT BRITAIN. 1956. p. 64.

References

Illustration from the True Highlanders Club Book showing the steps and times of the Sword Dance: http://www.electricscotland.com/history/club/club2%20084.jpg

Weapon Dance

In weapon dances, as the name implies, the performers use weapons (or stylized versions of weapons) to simulate or enact combat in the form of a dance. As a rule, such dances serve some ceremonial purpose, and they are also quite common in folk rituals in many parts of the world. The weapon dance is certainly very ancient. There are mentions of him among the earliest historical evidence that has survived to this day. For example, in ancient Sparta, the “Pyrrhic” (or “Pyrrhic dance”) was practiced. It was used as a kind of ritual to prepare for battle.

But today there are practically no places in the world where the weapon dance is directly related to the upcoming or recent battle. This is especially true of European states, which have long abandoned tribalism, which usually leads to the emergence of such folk dances. But this is also true in parts of the world where tribal traditions have given way to colonialism and the forces of globalism. The folk dances that everyone sees today are often part of a movement developed by local societies aimed at preserving and "rejuvenating" tribal or local traditions. Some of these movements have not changed for centuries - for example, among the indigenous North American tribes and the indigenous peoples of Australia.

But this is also true in parts of the world where tribal traditions have given way to colonialism and the forces of globalism. The folk dances that everyone sees today are often part of a movement developed by local societies aimed at preserving and "rejuvenating" tribal or local traditions. Some of these movements have not changed for centuries - for example, among the indigenous North American tribes and the indigenous peoples of Australia.

Hunting dances are closely related to weapon dances and war dances. There is a very ancient mention of a hunting dance with weapons in the form of a rock art at Çatal Huyuk, a large Neolithic settlement in south-central Anatolia. This drawing depicts a hunting ritual in which the dancers hold their bows.

In today's world, dance has come to be seen as something that can be done simply for recreation. Thus, it distanced dance from the important role it has played in many human cultures throughout history (a method of expressing, preserving and transmitting the culture and history of a people). Many of the activities that people have been engaged in for thousands of years (such as religion and courtship) have traditionally been reflected in various types of dance. Another occupation - fighting - obviously also occupied a central place in the life of most human cultures. Thus, dances can be found that celebrate skill in the use of weapons. In fact, there are many such weapon dances in the world. They range from general displays of skill in the use of weapons to reenactments of actual culture-specific battles.

Many of the activities that people have been engaged in for thousands of years (such as religion and courtship) have traditionally been reflected in various types of dance. Another occupation - fighting - obviously also occupied a central place in the life of most human cultures. Thus, dances can be found that celebrate skill in the use of weapons. In fact, there are many such weapon dances in the world. They range from general displays of skill in the use of weapons to reenactments of actual culture-specific battles.

Early examples of sword and spear dances can be found among the Germanic tribes of Northern Europe (they were mentioned by the famous ancient Roman historian Tacitus), Norwegian peoples and Anglo-Saxon tribes. In the barrow necropolis of Sutton Khu, images of people dancing with spears were found. Other references to similar traditions can be found in The Book Ceremony of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (c. 953), which describes the Varangian Guard (a group of Norwegian and then English and Anglo-Danish warriors) dancing in two circles. Some of them wore animal skins and masks, while others struck their shields in rhythm with their staves.

Some of them wore animal skins and masks, while others struck their shields in rhythm with their staves.

The sword dance still exists in some parts of Europe. Weapons may be used to act out mock combat during the dance, or may be included as an element of the dance itself, with the dancers "weaving lace in the air" with their blades. In some places sticks are used instead of swords. In Iberian stick dances (paulitos, paloteos, ball de bastons), two rows of dancers line up opposite each other. One of the most popular sword dances in Europe is the Moresca in Spain, which is meant to commemorate the struggle between Christians and Muslims in that country from the 12th to the 15th century. Also, these battles are celebrated by the "parade of Moros and Christianos", as well as the British dance Morris.

In Macedonia and northern Italy, weapon dances may be used to drive away evil spirits before marriage. Saber dances also exist in the Balkans. The most famous of them comes from Albania - in it two "rivals" - men imitate a duel over a woman.