How to dance the charlston

How To Do The Charleston? • Learn The 20s Charleston

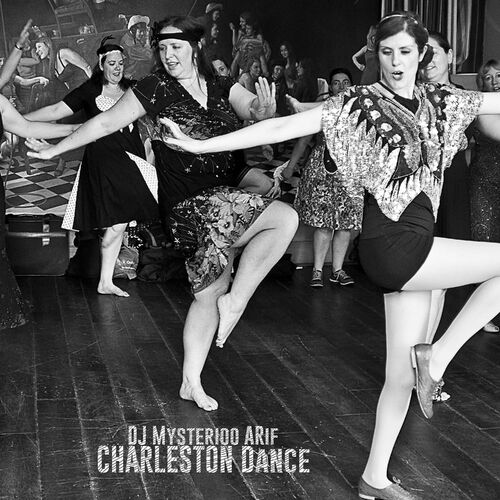

The Charleston dance was "The King of dances" in 20th century and had a huge influence on American culture. In this blog you can find out different ways of how to do the dance, its technique and footwork.

Charleston dance history

Charleston is a name of the city, dance style, step and song. Scholars attribute the spread and invention of the geechee inspired Charleston dance to the Jenkins Orphanage Band boys from Charleston city, South Carolina. The Charleston song written by John P. Johnson, inspired by Gullah rhythms, became the signature tune for the dance.

This dance has African roots and was created by African - American people. It was first sighted in the streets of Harlem in 1903. Though it was popularised by young flappers during 1920's. It became internationally known thanks to Josephine Baker Parisian "Le revue negre".

If you'd like to learn about the origins of the dance there is a full blog on The History of The Charleston dance.

6 version of how to do the Charleston step

In order to know how to do the Charleston “basic” step we should know that it has changed with time and place. It started as a step with twists, then transformed into a crazy wild kicking move with the swing era.

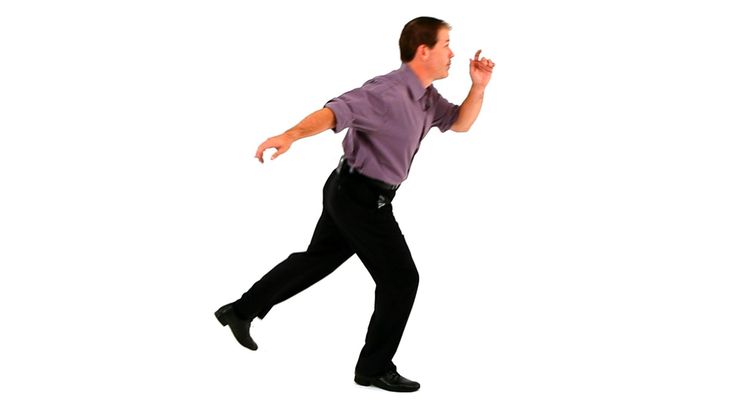

There are at least 6 versions of the “basic” step: groove walk, kicks, swinging kicks, 20’s twist, 20’s glide, and afro version “reverse twist” Charleston. Each version has its specifics.

- When doing groove walk, we should remember to keep a steady and strong bounce (pulse).

- For kicks the most important thing is to keep the right timing of the kick step and kick from the knees. All while keeping the body inclined forward and only forward and making sure to move with the kicks and not to stay on one spot.

- 20’s Charleston style with twists has its thing in a constant (every single beat) energetic though light twisting of the feet with the weight on the balls of the feet. All while making the kick up in the air and accentuating the weak (off) beat.

- 20’s glide is similar to 20s Charleston twist but is done without lifting the feet off the floor this way creating continuous gliding on the floor.

- Finally, to do the reverse Charleston twist we shall keep the legs bent low and keep the whole foot on the ground with the weight mainly of the heels.

In this video you can learn 6 basic versions of how to do the Charleston “basic” step: groove walk, kicks, swinging kicks, 20’s twist, 20’s glide, and afro version “reverse twist”.

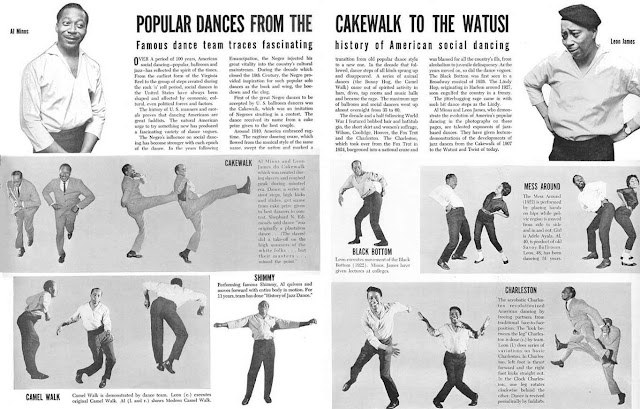

35 Charleston variations

Here is a video of two legendary dancers Al Minns and Leon James perform jazz dances talk show "Playboy's Penthouse". You can hear Marshall Stearns discusses the dance history with Hugh Hefner. This was probably filmed around 1960. Stears explains that there were 35 variations of the Charleston step. Minns and James show a few: original 20's charleston, scare crow, squat, around the world, high kick and hand to hand variations.

This was probably filmed around 1960. Stears explains that there were 35 variations of the Charleston step. Minns and James show a few: original 20's charleston, scare crow, squat, around the world, high kick and hand to hand variations.

How to do the 20s Charleston dance style?

20s Charleston is not only a step, it’s a style. A style that is defined by music, clothing style, manner and expression. 20s Charleston was a craze during the Jazz Age. It is danced to ragtime, hot jazz and Charleston. In order to look authentic we should remember a few important technical elements on how to do the 20s Charleston:

- As it is danced to ragtime and hot jazz (early jazz, Dixieland, New Orleans jazz).

The music is syncopated and has a “rag” rhythm though it is still quite even. The accentuation is on 2 and 4 and so will be the bounce, as the bounce always reflects the music rhythm.

The music is syncopated and has a “rag” rhythm though it is still quite even. The accentuation is on 2 and 4 and so will be the bounce, as the bounce always reflects the music rhythm. - As the music is ragged and the body can embody this quality the best when being more “puppet” like. It is better if we use more joints rather than muscles for the light, ragged, fast movements of 20s Charleston

- The accentuation is on 2 and 4 and so should be the accent when doing the 20s kicks. The accent is in the air and not on the floor.

How to achieve this light yet energetic and powerful state when dancing Charleston 20s? How to handle this hell of a tempo and curvy, twisty moves? We need to adopt the right body state. The imagery for the Charleston body that I love to use is a puppet or marionette. This loose movement, fully working on release, using movement of the joints, so that every kick and move pops to every beat and syncopation in the music.

The magic of Charleston dance is as well in the feet. Every single step is a twist. They create that recognisable angular and asymmetric signature Charleston look. Imagine, you are dancing on a hot frying pan, how would you move your feet?

Every single step is a twist. They create that recognisable angular and asymmetric signature Charleston look. Imagine, you are dancing on a hot frying pan, how would you move your feet?

In this video below you can learn about the Charleston 20s body and the twists!

To dive deeper in the fury of Charleston footwork, try this class on Happy Feet move, one of the signature steps.

Aesthetics of the 20s

There is a lot to learn from seeing the connection of the Charleston dance aesthetics with cultural elements of 20th century America.

- Deep connection to African roots reveals elements of improvisation, spontaneity as well as grounded body position.

- There is connection with flappers and their revolutionary new image of a woman and sexually charged movements.

- Comedy connects to 20s Charleston with its silly moves and irony.

- We can see connection with silent movies through the exaggerated overly dramatic expressions.

- Finally eccentric dance is a part of this dance culture with its legomania and bizarre movements.

You will look super authentic if you will include those qualities, impressions in your dance.

Its important to mention that this dance was immensely popular during the period of 1920's Prohibition as well as 1930's Great Depression. When US stock market crashed and part of the society was left in complete poverty, dancing for many was an anti - depression pill. It swept the worries away.

Look at the fantastic Bee Jackson, the “Queen of Charleston” and get ideas on how to do the Charleston! Miss Bee Jackson of the Piccadilly Cabaret and Kit Kat Club demonstrates her gimmick - dancing on a very small floor space.

In this demo video you see me demonstrating the concept of a “Silent Movie”. I am slowing down and speeding up in the real time (without FX), while searching for exaggerated overly dramatic face expressions. The idea comes from the fact that the music was layered on silent movies after the film was done. Oftentimes the music played an atmospheric role. Therefore the dance and movements looked out of time with the actual beat of the song.

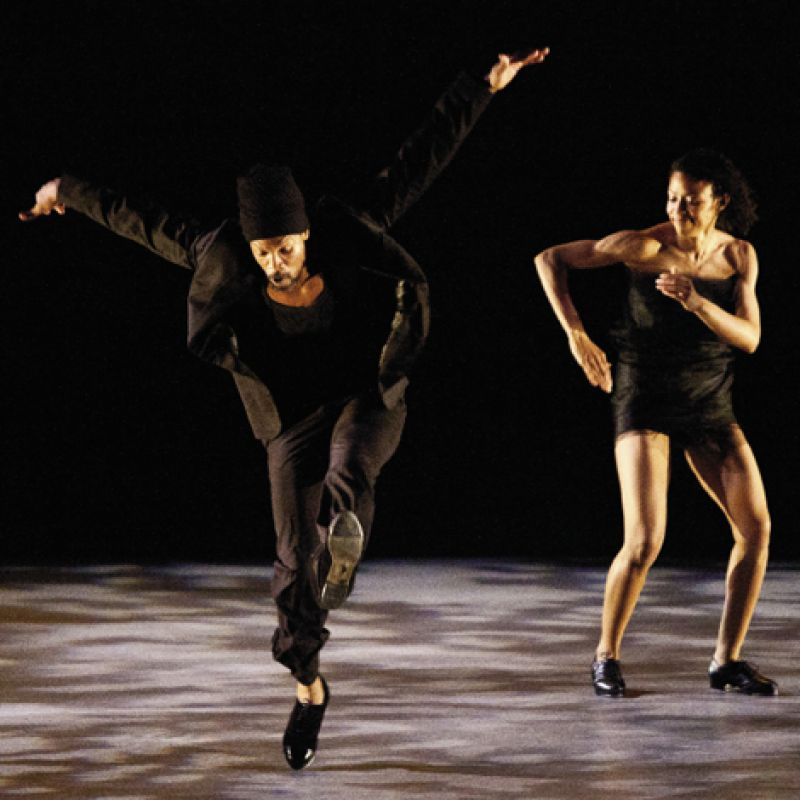

Animalism and African roots

I'd like to accentuate the connection with animalism in dance movements as the Charleston dance belongs to the family of African-American vernacular dances. To know more on what are the characteristics of African-American dances that as well reflect in the this dance, read the blog on “ A brief cultural history of black dance”

In this video class from the course Secrets of Charleston 20s, where you can learn how to do the step called the “Cow Tail”. Animalistic move, in a way it was inspired by the cows waving their tail to get rid of the flies.

All of this and more you can learn by taking a course Secrets of Charleston 20s, course with over 40 video.

Iconic Charleston dancers

Some of the iconic dancers to watch, learn and get inspired:

Josephine Baker

Ann Pennington

Bee Jackson

Al Minns

Leon James

Mildred Melrose

Joan Crawford

Jenkins Orphanage Band boys

In this video playlist on Secrets of Solo channel I collected videos of the most famous dancers, historical figures. Watch to get inspired.

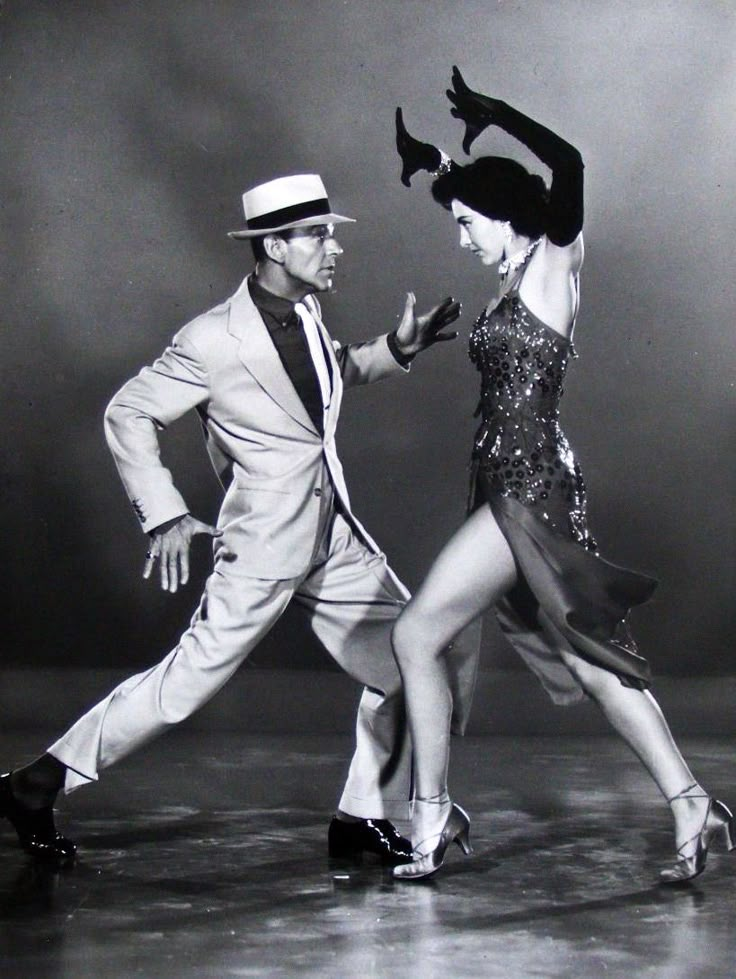

The difference between 20s & 30s style Charleston

As we mentioned before the Charleston dance style has changed with time and music. I use this categories to spotlight the difference that was strongly affected by the music, more specifically rhythm section.

20s

In 20s Charleston with hot twists and eccentric moves was danced to ragtime, hot jazz music. It has half time pulse and accentuated the 2 and 4 beat. It replicates the bass tuba or the double bass. Bass tuba line for early jazz was either 1 and 3 or 2 and 4. When double bass came to stage, the players wither played half time notes or doubled up on the same note twice. 1/2 feel reflects in half time pulse in the dancers body. The movement is more even, more vertical and ragged.

It has half time pulse and accentuated the 2 and 4 beat. It replicates the bass tuba or the double bass. Bass tuba line for early jazz was either 1 and 3 or 2 and 4. When double bass came to stage, the players wither played half time notes or doubled up on the same note twice. 1/2 feel reflects in half time pulse in the dancers body. The movement is more even, more vertical and ragged.

The 20s style is based on the twists and twisted kick. The most important image is the "crossed" twisted leg. The legend says, some dancers got "Charleston twist" of the knee, when they twisted too hard.

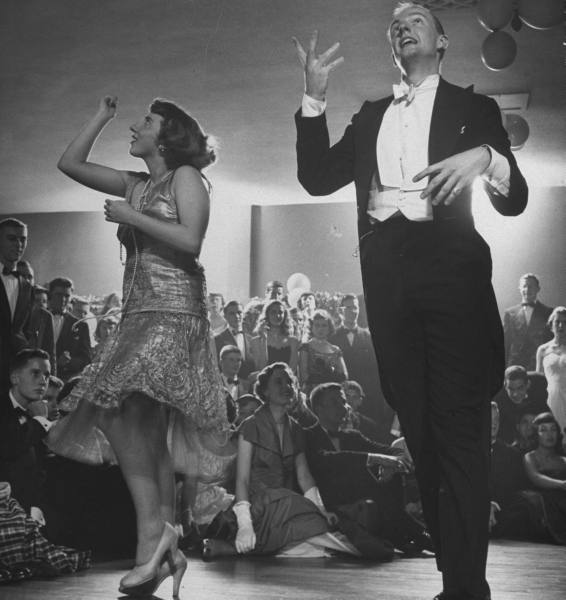

In this video you can hear a very rag song. Notice that the dancers are holding their bodies more upright. Their pulse is ragged (even jumpy at times).

30s

In 1930's the dance changed with swing music to so called lindy kicks. You could see now dancers doing big wide kicks and travelling across the floor. The feel of the Charleston is 4/4 (4 on the floor). It reflects the double bass in swing tunes, that has a walking line. So called "walking bass". Musicians say "the bass walks", when the player hits every single note. 4/4 feel reflects in constant pulse in the dancers body. The movement is "spreading", it is more horizontal. It looks softer and smoother.

So called "walking bass". Musicians say "the bass walks", when the player hits every single note. 4/4 feel reflects in constant pulse in the dancers body. The movement is "spreading", it is more horizontal. It looks softer and smoother.

In this video you can hear the 4/4 feel on the bass and clearly see how dancers reflect it in their smooth pulse. Note, when dancers go to lindy Charleston kicks, how much they lower their upper body and start to hover over the ground.

Music to dance Charleston

Ragtime

The first tune you would think to dance Charleston to is, of course, famous ragtime tune "The Charleston", written by James P. Johnson. The Charleston beat is considered a clave rhythm.

As a musical entity ragtime was, and is, an instrumental work in 2/4 time composed for the piano. The style surfaced in the early 1900's and was developed by composer Scot Joplin. It was the forerunner to jazz. It combines a syncopated series of melodies accompanied by a steady, even rhythm. The left hand plays a steady, almost march-like succession of bass notes and chords while the right hand plays syncopated melodies in a "ragged" manner. Hence, the name of the style.

The left hand plays a steady, almost march-like succession of bass notes and chords while the right hand plays syncopated melodies in a "ragged" manner. Hence, the name of the style.

Here is a Spotify playlist of ragtime tunes. You will hear the music of Eubie Blake, Scot Joplin, James P. Johnson.

Dixieland

Other music style that one can dance 20s Charleston is early jazz. Early jazz, that is as well called “New Orleans jazz”, Dixieland jazz, hot jazz are the terms referring to the same style of jazz based on the music that developed in New Orleans at the start of the 20th century. Its 4 main influences were ragtime, military brass bands, the blues, and gospel music.

New Orleans jazz or Dixieland Jazz was incredibly popular through the 1920s, Jazz Age. One of the first uses of the term "Dixieland" with reference to music was in the name of the Original Dixieland Jass Band (later changed to "Jazz"). They recorded their first vinyl in 1917. What defines the sound of Dixieland music is that one instrument plays the melody (often trumpet) and all the other musicians improvise around it.

Here is a Spotify playlist with a very popular songs for 20s Charleston. You will hear music of such artists as Original Dixieland Band, Fats Waller, Sidney Bechet, King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, Frankie Trumbauer and his Orchestra, Fletcher Henderson, Bix Beiderbecke, Jelly Roll Morton, Benny Goodman and other. Or else you can listen to my YouTube Charleston compilation.

Written by Ksenia Parkhatskaya

Tracing the Roots of the “Charleston” Dance

The dance craze known as the “Charleston” achieved world-wide fame nearly a century ago and has endured as the epitome of the carefree exuberance of the “Roaring Twenties.” Although this popular phenomenon shares a name with our home town, it arose from cultural ingredients stewing in the melting pot of New York City at the crest of the Jazz Age. We might not have invented the “Charleston” in Charleston, but evidence suggests that residents of the Palmetto City and of the Lowcountry in general provided the inspiration and key elements that define its iconic rhythm and footwork.

The “Charleston” is a multi-faceted cultural phenomenon that arose during the early 1920s. It’s a dance, it’s a tune, and it’s a set of lyrics (which most people have never heard). All three forms first captured public attention in late October 1923 in a Broadway revue called Runnin’ Wild, which ran for more than seven months at the New Colonial Theater in midtown Manhattan. That African-American production included music by James P. Johnson (1894–1955), lyrics by Cecil Mack (1873–1944), and the talents of a large cast of black singers and dancers. The popular success of Runnin’ Wild catapulted the “Charleston” to national and international fame within a period of less than two years. To this day, the “Charleston” is closely associated with the decade of the 1920s, an era frequently called the “Jazz Age.” Despite the existence of Federal laws prohibiting the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, that decade is largely remembered as an era of exuberant parties, superficial glamor, energetic jazz, and hedonistic excess in general. Separately and in tandem, the dance and the tune called “Charleston” epitomize the gay spirit of the “Roaring Twenties.”

Separately and in tandem, the dance and the tune called “Charleston” epitomize the gay spirit of the “Roaring Twenties.”

Charleston Time Machine · Episode 166: Tracing the Roots of the “Charleston” Dance

So it’s a fair question to ask: What—if anything—does the cultural phenomenon known as the “Charleston” have to do with the city and county of Charleston, South Carolina? Well, that’s not an easy question to answer, but I’m willing to give it a try, as long as we all agree that we cannot plumb the full depth of this topic in one podcast. With that caveat, I’ll try to follow a narrow path through the dense cultural history and lead you to a reasonably satisfactory answer. In short, the connection between the “Charleston” music and dance and the place we call home is indirect, elusive, and difficult to articulate. Nevertheless, I assure you that a connection most definitely exists.

In short, the connection between the “Charleston” music and dance and the place we call home is indirect, elusive, and difficult to articulate. Nevertheless, I assure you that a connection most definitely exists.

The genesis of the “Charleston” phenomenon in New York City in the early 1920s was a direct result of a large population shift now known as the “Great Migration.” During the first half of the twentieth century, millions of Americans of African descent left their homes in the various Southern states and moved northward in search of economic opportunities and greater civil liberties. This exodus began quietly in the years after the end of slavery in 1865 and increased a bit around the turn of the twentieth century as the so-called “Jim Crow” laws adopted by Southern states generally eroded the already-poor quality of life afforded to non-white citizens here. The stream of African Americans moving northward swelled significantly during World War I and remained strong for several decades. Historians of this phenomenon estimate that more than six million black Americans moved from the largely-agricultural South to the largely-industrial North between 1910 and 1970.

Historians of this phenomenon estimate that more than six million black Americans moved from the largely-agricultural South to the largely-industrial North between 1910 and 1970.

This sustained mass movement of people resulted in significant and long-lasting changes in our national economy and political demographics. It also had powerful cultural implications. People of African descent had been living and working in the Southern states for nearly three centuries before the 1920s, melding and adapting African cultural traditions amongst themselves and interacting with both Native American and European culture. Northern communities like New York weren’t completely devoid of their own African-American culture, of course, but the Great Migration infused communities like Harlem with a flood of new practices and energy. That fertile environment gave rise to a profusion of cultural expression that became known as the Harlem Renaissance in New York and similar phenomena in other Northern cities.

The “Charleston,” meaning both the song and the dance, serves as an excellent example of the cultural effects of the Great Migration. James P. Johnson, whose infectious and original “Charleston” tune is known around the globe, later said he had borrowed its distinctive syncopated rhythm from South Carolina longshoremen who had migrated to New York. Anyone familiar with the traditions of Gullah-Geechee spirituals will recognize that rhythm as an integral part of a Lowcountry shout or “ring shout,” so it’s not difficult to hear some truth in his statement. While working as a pianist in a nightclub frequented by former Charlestonians, Johnson improvised piano music to match their distinctive footwork and handclapping rhythms. Although a native of New Jersey, Johnson also demonstrated his familiarity with the Lowcountry his neighbors left behind in other compositions like his Carolina Shout of 1921 and his extended “Negro Rhapsody” of 1928 called Yamecraw.[1]

Other early descriptions of the footwork associated with the “Charleston” dance mention New Yorkers observing Gullah-Geechee migrants strutting their vernacular stuff in Harlem nightclubs. A century after its birth, it’s now impossible to identify a specific person or event or location that directly inspired the creation of the “Charleston” dance, but contemporary newspaper reports provide useful clues. The success of Runnin’ Wild and its signature dance number caught the attention of local journalists, who in turn tried to describe the new phenomenon to a broader audience. Within a year of the show’s Broadway debut, even the Charleston Evening Post took note of the publicity and joined the growing conversation about the new dance craze.

A century after its birth, it’s now impossible to identify a specific person or event or location that directly inspired the creation of the “Charleston” dance, but contemporary newspaper reports provide useful clues. The success of Runnin’ Wild and its signature dance number caught the attention of local journalists, who in turn tried to describe the new phenomenon to a broader audience. Within a year of the show’s Broadway debut, even the Charleston Evening Post took note of the publicity and joined the growing conversation about the new dance craze.

“Something new in the way of advertising for Charleston is developing quite rapidly in New York,” said the Post in early November 1924, “and, if it follows the usual course, will in due time become the newest rage in the terpsichorean art.” More importantly for our fair city, the local press noted that the new dance sensation will “have the name of ‘Charleston’ on the tongues of thousands throughout the country. ” That bold prediction proved to underestimate the dance’s international appeal, of course, but we have to remember that the “Charleston” seemed little more than a passing fad in 1924. Because the new dance was reputed to have authentic roots in the Palmetto City, however, the editors of the Evening Post deemed it necessary to reprint the entire text of a story from the New York World: I’d like to share the text, too, because I think it represents the best contemporary summary of the genesis of the “Charleston” dance:

” That bold prediction proved to underestimate the dance’s international appeal, of course, but we have to remember that the “Charleston” seemed little more than a passing fad in 1924. Because the new dance was reputed to have authentic roots in the Palmetto City, however, the editors of the Evening Post deemed it necessary to reprint the entire text of a story from the New York World: I’d like to share the text, too, because I think it represents the best contemporary summary of the genesis of the “Charleston” dance:

“‘Can you do the ‘Charleston?’ That is the question generally asked in Harlem among negroes, irrespective of age, size or physical condition. In other sections of New York City the “Charleston” has its enthusiastic devotees, but not so many as in the 135th Street and Lenox Avenue district where they energetically indulge in this terpsichorean specialty on the ball room floor, in cabarets, ratskellers and even in the home.

On the street corners, day and night, crowds assemble to watch urchins ‘do the Charleston’ for voluntary contributions ranging from a penny upward.

‘Charleston’ contests are conducted weekly in North Harlem theaters patronized largely by negroes. On some occasions 30 or more contestants, usually boys, give individual exhibitions.

Danced somewhat indifferently by a few local negroes prior to the engagement of ‘Runnin’ Wild’ in the Colonial theater last season, the ‘Charleston’ began to grow in popularity when 22 girls and three boys in the colored production put it over in spectacular fashion at the close of the first act of a musical number of that name, written by Cecil Mack and Jimmie Johnson. Quick to appreciate something new and novel was being offered in the realm of dancing, white Broadway musical shows immediately made the ‘Charleston’ a feature.

The ‘Charleston,’ apparently of African origin and characterized by [a] tom-tom beat, is described as the wing of the buck and wing dance, only the dancer steps forward and backward instead of sideways. Usually, it is done without musical accompaniment and to the clapping of hands in two-four time.

It is said to have been brought to New York by negroes formerly living in Charleston, S.C., having been first danced on the neighboring islands by negroes known as the “Geeche[e].

In recent months, the ‘Charleston’ has been supplemented with many new steps, the two most popular being the ‘camel walk’ and the ‘black bottom.’ To be a successful and graceful dancer of the ‘Charleston,’ agility and nimbleness of foot are the requisites—avoirdupois [heavy weight] being a decided handicap.”[2]

Although it may be impossible to identify the specific individuals and incidents that catalyzed the “Charleston” phenomenon in early-twentieth-century Harlem, this 1924 newspaper report contains a few clues that appear to support a belief long-held here in Charleston. It mentions that most of the early practitioners of the dance steps were “boys”—specifically, poor boys or “urchins”—who frequently appeared on street corners giving “exhibitions” for pennies and other loose change. For readers familiar with the history of the Jenkins Orphanage Band, these words instantly call to mind the band’s annual migrations in the early twentieth century, during which they played and danced on street corners in Northern cities to raise money for their Charleston home. As the late Jack McCray described in his 2007 book about Charleston Jazz, musicians in the Palmetto City have long believed that it was the young boys of the touring Jenkins Orphanage Band who introduced both the distinctive rhythm and footwork that characterize the “Charleston” dance phenomenon.

For readers familiar with the history of the Jenkins Orphanage Band, these words instantly call to mind the band’s annual migrations in the early twentieth century, during which they played and danced on street corners in Northern cities to raise money for their Charleston home. As the late Jack McCray described in his 2007 book about Charleston Jazz, musicians in the Palmetto City have long believed that it was the young boys of the touring Jenkins Orphanage Band who introduced both the distinctive rhythm and footwork that characterize the “Charleston” dance phenomenon.

For those of you not so familiar with the history of the Jenkins Orphanage Band, I’ll offer a brief synopsis to bring you up to speed. In December 1891, the Reverend Daniel J. Jenkins (1862–1937) established an Orphan Aid Society to assist indigent black children living in the lower wards of urban Charleston. (Rev. John L. Dart’s school, founded in 1895, served black children on the city’s north side). Reverend Jenkins’s work included a day school for boys and girls and an orphanage to house the neediest children. To help raise money for these charitable institutions, the Orphan Aid Society immediately sought to capitalize on one of the most valuable talents within the city’s black community: music. The Society solicited donations of band instruments and recruited some young adult black musicians to instruct some of the school children. By the mid-1890s, the Jenkins Orphanage, as it was commonly called, had a band of more than a dozen young boys who could play ragged versions of popular songs and dance tunes. Many writers have described the Jenkins Orphanage Band as the “cradle of jazz” in Charleston, but the roots of African-American band music in this city extend back nearly two centuries before Reverend Jenkins started his orphanage. That long and complicated story merits its own conversation, so for the present we’ll stick to the early twentieth century.

To help raise money for these charitable institutions, the Orphan Aid Society immediately sought to capitalize on one of the most valuable talents within the city’s black community: music. The Society solicited donations of band instruments and recruited some young adult black musicians to instruct some of the school children. By the mid-1890s, the Jenkins Orphanage, as it was commonly called, had a band of more than a dozen young boys who could play ragged versions of popular songs and dance tunes. Many writers have described the Jenkins Orphanage Band as the “cradle of jazz” in Charleston, but the roots of African-American band music in this city extend back nearly two centuries before Reverend Jenkins started his orphanage. That long and complicated story merits its own conversation, so for the present we’ll stick to the early twentieth century.

The youthful Jenkins Orphanage Band was a fixture of the local music scene—not only in Charleston, but in other communities as well. Every year for nearly half a century, the band set out by rail, steamship, and motor bus with adult chaperones to perform from Maine to Miami. They toured Southern cities in the winter months, and headed north every summer. At their peak in the 1920s, there were four Jenkins Orphanage bands on the road at the same time, and, for a while, an all-girl band as well. In communities with large black populations, the bands played indoor concerts and entertained crowds at barbeques and parties. Most of their performances took place on street corners and sidewalks, however, where they gathered pennies and nickels from passing pedestrians.

They toured Southern cities in the winter months, and headed north every summer. At their peak in the 1920s, there were four Jenkins Orphanage bands on the road at the same time, and, for a while, an all-girl band as well. In communities with large black populations, the bands played indoor concerts and entertained crowds at barbeques and parties. Most of their performances took place on street corners and sidewalks, however, where they gathered pennies and nickels from passing pedestrians.

Surviving descriptions, photographs, moving pictures, and personal recollections all demonstrate that footwork was an integral part of the Jenkins Orphanage band’s routine. While the standing musicians might have been too busy making noise to dance in place, the ubiquitous band leader was often the star of the show. The smallest and perhaps youngest member or members of the troupe—perhaps too young to play an instrument—usually stood in front of the band, dancing and waving his arms in time with the music. Ostensibly “conducting” the performance, he was really putting on a show to entertain the audience. The energy and novelty of the young conductor’s fancy footwork was a key element in the band’s fund-raising success. Did the conductor perform “the” Charleston steps? We may never know for sure, but it seems likely that some Charleston-like moves were part of his physical repertoire.

Ostensibly “conducting” the performance, he was really putting on a show to entertain the audience. The energy and novelty of the young conductor’s fancy footwork was a key element in the band’s fund-raising success. Did the conductor perform “the” Charleston steps? We may never know for sure, but it seems likely that some Charleston-like moves were part of his physical repertoire.

Back in Charleston, fires at the Jenkins Orphanage headquarters in December 1936 and again in November 1988 destroyed most of the institution’s early records. One sound recording survives from a grainy 1928 newsreel, but the poor quality of its audio provides only a hint of the band’s brassy sound. The paucity of surviving resources now renders it difficult to reconstruct the details of the band’s musical characteristics, the itinerary its annual migrations, and the identity of its youthful participants. Thanks to surviving newspaper reports and oral histories, however, we know that Manhattan and Harlem were regular stops. It’s quite possible, therefore, that New Yorkers, specifically Harlemites, learned the distinctive rhythm and footwork that became known as the “Charleston” not from anonymous dockworkers who had migrated northward from the Palmetto City, but from the energetic boys in the Jenkins Orphanage Band.[3]

It’s quite possible, therefore, that New Yorkers, specifically Harlemites, learned the distinctive rhythm and footwork that became known as the “Charleston” not from anonymous dockworkers who had migrated northward from the Palmetto City, but from the energetic boys in the Jenkins Orphanage Band.[3]

In short, the “Charleston” dance phenomenon was a product of various cultural forces originating in Africa and Europe that germinated in the crucible of Charleston and blossomed in Harlem in the early 1920s. It arose from the urban black community and was quickly imitated by white artists who introduced it to broader audiences in New York and around the world. Over the past ninety-odd years, tens of millions of people have enjoyed its rhythm and energy that came to epitomize the Jazz Age. Even if they know nothing about our fair city by the sea, at least they know the name of Charleston.

In fact, the marketing and distribution of the “Charleston” dance represents another chapter in the history of this cultural phenomenon. If you’ve read any book or article about the history of the “Charleston” dance, or searched the vast digital ocean of the Internet for information on this topic, you’ve surely seen an image of a young white female dancing the “Charleston” with the uniformed boys of the Jenkins Orphanage Band standing behind her. That photograph, which has been reproduced thousands of times, was staged here in Charleston in the spring of 1926 as part of a promotional campaign, but few people remember the curious story behind its creation. Next week, we’ll continue this dance theme with the story of Beatrice Adelaide Jackson and her campaign to become the international queen of the “Charleston.”

If you’ve read any book or article about the history of the “Charleston” dance, or searched the vast digital ocean of the Internet for information on this topic, you’ve surely seen an image of a young white female dancing the “Charleston” with the uniformed boys of the Jenkins Orphanage Band standing behind her. That photograph, which has been reproduced thousands of times, was staged here in Charleston in the spring of 1926 as part of a promotional campaign, but few people remember the curious story behind its creation. Next week, we’ll continue this dance theme with the story of Beatrice Adelaide Jackson and her campaign to become the international queen of the “Charleston.”

[1] Jack McCray, Charleston Jazz (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2007).

[2] Charleston Evening Post, 4 November 1924, page 12, “Can you Dance the Charleston?” quoting an article of the same title by Lester A. Walton in the New York World, 3 November 1924.

Walton in the New York World, 3 November 1924.

[3] Extant descriptions of the band’s precise movements on tour are now rare, but a very useful example appears in New York Times, 1 August 1912, page 6, “Concert by Negro Children.”

PREVIOUS: Remembering Charleston’s Liberty Tree, Part 2

NEXT: Bee Jackson Wanted to “Charleston” in Charleston in 1925

See more from Charleston Time Machine

Types of modern dances. Charleston dance.

The Charleston is a dance named after the city of Charleston in South Carolina. Rhythm gained ground in US mainstream music with the premiere of a show on Broadway called "Runnin' Wild", which debuted the song "Charleston" written by James P. Johnson and became an immediate hit.

It is impossible to name the exact place where the dance originated, although today in the city of Charleston, South Carolina, they will not only tell you that the dance was born here, but they will even demonstrate a specific place - an orphanage "Jenkins Orphanage" - according to legend, it was the orphans from this orphanage who invented the dance, later called the Charleston, the music on the basis of which formed the basis of the musical, which became zamenimy.

And its existence is recognized long before the triumphant appearance on the stage of the musical “ Runnin’ Wild ”, where, along with the debut of James P. Johnson’s song “ Charleston ”, the dance of the same name was performed. However, it was from this moment that the popularity of the Charleston began to rapidly gain momentum.

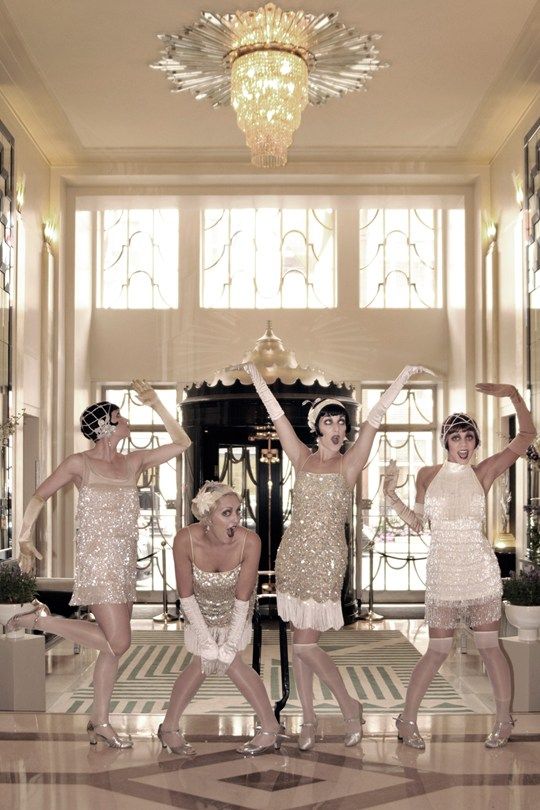

At first, this dance was mostly associated with young emancipated girls, who were called flappers (from the English - cracker), it was they who could afford to dance alone and demonstrate contempt for the old traditions in the dance.

Despite accusations of immorality and swagger, undermining the foundations of the nation's spirituality, all segments of the American population were carried away by the Charleston. There was no official Charleston training in dance classes, so wealthy people began to take lessons from their own servants: cooks, maids and laundresses, who mastered this dance much faster.

In general, there was nothing complicated in the performance of the dance. He was considered easy to learn, it was only necessary to learn how to make energetic movements with his arms and legs to fast music. On the other hand, the number of injured people has increased due to the irrepressible desire to put all the available energy and strength into the Charleston.

Charleston was a new dance. The Charleston was a fast dance. The Charleston was a simple dance. The Charleston was a dance that could be danced with a partner or alone. But most importantly, the Charleston was the first dance to blur the line between "dance being danced" and "dance being looked at" - by 1925, it seemed that everyone danced it.

Dance Critic Roger Pryor Dodge recalled a police officer in St. Louis who directed traffic by dancing the Charleston.

Charleston, unlike other dances, became both spectacular and performing: it could be danced and watched. Charleston was brought to Europe by Josephine Baker , it was in her performance that the Parisian public saw this dance for the first time. Thanks to her, dance in Europe has become no less popular than in America.

Charleston was brought to Europe by Josephine Baker , it was in her performance that the Parisian public saw this dance for the first time. Thanks to her, dance in Europe has become no less popular than in America.

Charleston technique

Charleston has a syncopated rhythmic structure, 4/4 time.

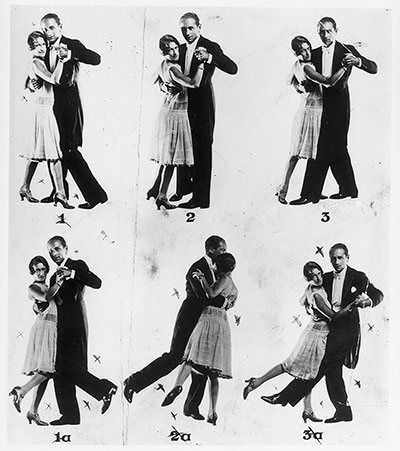

They dance the Charleston both in pairs and solo. The basic step is performed in place or moving forward, backward and to the side. The step begins with an off-beat movement, when the heels are parted, the support is on the left leg, and the right one simultaneously rises in a bent position with a twist to the right and back.

The same movement is carried out with the other leg. The off-beat movement is performed with closed knees. Hands move freely and vigorously.

The basic step can be performed by moving back and forth and sideways, as well as turning around its axis. The dance requires a lot of improvisation and, if performed in pairs, the main move varies in the positions of the partners and combinations of movements.

Charleston Features

Vigorous hand movements and characteristic foot turns are the main features of this dance. It has certain features of ballroom choreography, namely, the foxtrot, with the difference that the Charleston has a limited nature of movement and is performed most often on the spot. The musical accompaniment is represented by certain compositions of jazz and swing.

Despite its scandalous reputation, at the beginning of the last century Charleston became the king of dances. Having begun his victorious march in America, he conquered Europe somewhat later. It was impossible not to be infected by the desire to dance this provocative, easy-to-perform dance. Chalston was performed both in pairs and individually.

Ballrooms and hotels regularly held dance competitions showing hundreds of variations of the basic Charleston step (officially there were 74 movements in the Charleston).

One of the most famous Charleston competitions was held in 1925 at the Orpheum Theater in Kansas City. It was won by Leonard Reid , the future creator of Shim Sham .

Unfortunately, Leonard did not manage to get his award - the competition was “only for whites”, and although he managed to participate in it thanks to his fair skin, someone envied his win and gave his secret to the organizers of the competition

Charleston was the king of dances - but it also suffered the fate of any "fashionable" phenomenon - in 1926 a new "fashionable" dance arose - Black Bottom , and the Charleston was to be forgotten, just as were previously forgotten Bunny Hug , Apache Dance and many more.

Salvation came in the form of a new trendy dance - Lindy Hop , which incorporated many of the Charleston movements. And thirty years later, when the Lindy Hop went out of fashion, the Charleston returned again - this time in the form of two rock and roll dances - Charley Bop and Mashed Potato, which did not last long, however.

And thirty years later, when the Lindy Hop went out of fashion, the Charleston returned again - this time in the form of two rock and roll dances - Charley Bop and Mashed Potato, which did not last long, however.

And then another fifty years passed - and Charleston began to dance on both sides of the ocean again ...

Dance clubs and schools

Types of dance 9000

9000 9000 9000 You're viewing: do_dance_charlston.html

NewOldUsefulUseless

Page 1 of 1

Write a review

Charleston, Cheerful dance, depraved dance

Charleston, South Carolina. Church of St. Mikhaila

Mulattos, bay, coffee export, so to speak, coffee dumping, Charleston “My girl has a little thing”

Ilya Ilf, Evgeny Petrov. Golden Calf

The world has changed

Oh, how beautiful and well designed the world seemed at the end of 19th and early 20th century, when the glorious Victorian era ended! Like a mighty steam locomotive, rushing at full speed into the future. Even in the class, sexual, national and racial inequality of the then society, many politicians and philosophers saw some lofty idea. Social inequality ensured the proper functioning of society and seemed as natural as the structure of a living organism, in which not all organs are equal, but all are necessary. Arts and literature contributed in every possible way to the improvement of morals. Technology and science have made humanity powerful and able to withstand the challenges of nature.

Even in the class, sexual, national and racial inequality of the then society, many politicians and philosophers saw some lofty idea. Social inequality ensured the proper functioning of society and seemed as natural as the structure of a living organism, in which not all organs are equal, but all are necessary. Arts and literature contributed in every possible way to the improvement of morals. Technology and science have made humanity powerful and able to withstand the challenges of nature.

In this sweet ecstasy, humanity fell into the First World War, hoping to end this little misunderstanding by Christmas. But it turned out that the war was destined to last four terrible years.

Dance the Charleston

During this war, it turned out that science and technology gave rise to the most productive weapons of murder: machine guns, airplanes, zeppelins and poison gases. All those who survived in the midst of this lethal frenzy, with good reason, considered their survival a miracle. And they doubted very much that this miracle was sent by God, as they had been taught once in childhood. Already they, the survivors, knew for sure that prayers did not save in battles. Death did not make out ranks, races and religions. On the battlefield, soldiers, semi-literate hard workers and peasants, and officers, the educated class were equally vulnerable. Bullets and shrapnel turned out to be infernal internationalists and equally struck white Europeans, blue-black Senegalese, and dark-skinned Indians.

And they doubted very much that this miracle was sent by God, as they had been taught once in childhood. Already they, the survivors, knew for sure that prayers did not save in battles. Death did not make out ranks, races and religions. On the battlefield, soldiers, semi-literate hard workers and peasants, and officers, the educated class were equally vulnerable. Bullets and shrapnel turned out to be infernal internationalists and equally struck white Europeans, blue-black Senegalese, and dark-skinned Indians.

Unexpectedly, feminism won. The weaker sex showed its strength and vitality, successfully replacing men at the machines, and at hard work, where, it seemed, nature itself set strict limits for women.

In general, the survivors seriously thought about whether they lived correctly before the war. And they understood: no, it's not. You can not hope for the future, it may simply not be! You can not build abstract plans! You have to live in the moment! If you really want to, hope in God, but don’t make a mistake yourself!

The Roaring Twenties

The decade after the Great War is often referred to as the "Roaring Twenties". The title is well deserved. They were indeed loud in the truest sense of the word. cars voted , which were produced in such quantities that, unlike horses, they became available to everyone. Radio became a mass medium, a small miracle that delivered news and music to people's homes. The music came from everywhere, from every entertainment establishment that visibly spread around: cafes, dance halls, theaters and cinemas.

The title is well deserved. They were indeed loud in the truest sense of the word. cars voted , which were produced in such quantities that, unlike horses, they became available to everyone. Radio became a mass medium, a small miracle that delivered news and music to people's homes. The music came from everywhere, from every entertainment establishment that visibly spread around: cafes, dance halls, theaters and cinemas.

Ksenia Parhatskaya performs the Charleston

And yes, the music has also changed. Before the war, this music, all this jazz, seemed like a cacophony. But now the hearing of mankind was corrupted by the thunder of guns and the explosions of shells. And jazz came just right.

For new music, terribly democratic, it was not necessary to go to concert halls dressed up as if for a diplomatic reception. In a cabaret, that is, in a tavern where wine was served, it was permissible to dance from the heart in front of everyone, to give out some kind of bullshit on the dance floor to dashing Negro music. Emboldened women no longer waited for the invitation of gentlemen. Under this rhythmic and crazy music, one could go on a crazy act in the old days and dance alone or in pairs with a girlfriend, raising their beautiful legs high and waving their arms cheerfully. Fortunately, dresses shortened to the knees of a new fashionable style made it possible to dance deftly and beautifully. It was not imperialism or socialism that captured the world, it was captured charleston .

Emboldened women no longer waited for the invitation of gentlemen. Under this rhythmic and crazy music, one could go on a crazy act in the old days and dance alone or in pairs with a girlfriend, raising their beautiful legs high and waving their arms cheerfully. Fortunately, dresses shortened to the knees of a new fashionable style made it possible to dance deftly and beautifully. It was not imperialism or socialism that captured the world, it was captured charleston .

Charleston from Charleston

The name of the dance comes from the city of Charleston (Charleston) in the US state of South Carolina. The city was founded in 1670 by settlers from England, naming it in honor of the then reigning king Charles II (1630 - 1685). But a piece of land on the American continent, where this city is located, was called a colony Carolina in honor of the father of this Charles, king, Charles I (1600 - 1649) , who was beheaded during previous revolutionary riots. Later, in 1729, the Carolinas split into North and South. So, the British monarchy and a frivolous dance turned out to be connected by a long thread of historical events!

Later, in 1729, the Carolinas split into North and South. So, the British monarchy and a frivolous dance turned out to be connected by a long thread of historical events!

The finale of the film "Chicago". Charleston

The Jenkins Orphanage is traditionally considered the birthplace of the Charleston dance. A brass band made up of black orphans played at city charity events. Young musicians merrily danced to the beat of the music. But the local dance would have remained a landmark of the provincial Charleston, if it did not get on Broadway. At 191920s black composer

James P. Johnson (1894-1955) wrote the song "Charleston" for the musical show "Runnin' Wild", which became an instant hit. The dance, which the artists danced wildly to this melody, quickly gained popularity. The American and world public has only just begun to get used to the idea of women's equality. And there was a Charleston - this has never happened before! - women's dance, and it excited the audience. Girls who danced the Charleston alone or as a couple were called "flappers". It was an ambiguous word. In English, it means "crackers". Judging by the old way, the name seemed to be contemptuous. After all, it is not fitting for a woman to dance without a gentleman! And if she dances alone, then she is looking for a man, a sponsor, which means she is a prostitute. The word "flapper" had another meaning, "whore". Charleston - the dance of accessible girls? O!

And there was a Charleston - this has never happened before! - women's dance, and it excited the audience. Girls who danced the Charleston alone or as a couple were called "flappers". It was an ambiguous word. In English, it means "crackers". Judging by the old way, the name seemed to be contemptuous. After all, it is not fitting for a woman to dance without a gentleman! And if she dances alone, then she is looking for a man, a sponsor, which means she is a prostitute. The word "flapper" had another meaning, "whore". Charleston - the dance of accessible girls? O!

Josephine Baker on the cover of her record

But, as already mentioned, during the war there were serious changes in society, and emancipated flapper girls usually worked. Because they had the means of subsistence. And they dreamed of a friend of the heart more than of a breadwinner spouse. And since, as a rule, the “crackers” were simple girls, their response to disrespectful harassment could also be simple, but sensitive. By the way, once again about the ambiguity of the word "flapper". Another meaning is "mallet". Therefore, down with tradition and glory to Charleston!

By the way, once again about the ambiguity of the word "flapper". Another meaning is "mallet". Therefore, down with tradition and glory to Charleston!

Charleston conquered America. Learning to dance was not difficult. His movements were simple and unsophisticated. The main skill was to move energetically to fast, rhythmic music and, smiling, raise legs rather high and swing arms vigorously. In 1925, all of America danced the Charleston.

When the time came to export the Charleston to Europe, the famous mulatto dancer Josephine Baker (1906-1975) came to Paris on tour from America. She fascinated Paris, but she herself was so fascinated by this city that, in the end, she took French citizenship. She proved her loyalty to her new homeland during World War II, fighting in de Gaulle's army against the Nazis. However, this is a different story. And at 19In 27, she danced the Charleston almost naked in a banana skirt, which outraged the usual French much less than the Americans. In general, thanks to Josephine Baker, the French public took the American dance with enthusiasm. And from Paris, he conquered all of Europe like Napoleon, and became as popular here as in America. So the Charleston became the king of dance in the 1920s.

In general, thanks to Josephine Baker, the French public took the American dance with enthusiasm. And from Paris, he conquered all of Europe like Napoleon, and became as popular here as in America. So the Charleston became the king of dance in the 1920s.

Well, speaking of kings, let's talk about how American dance captivated British kings. The Charleston crossed the English Channel and became so popular in Great Britain that even the heir to the crown, Edward, Prince of York, danced it. Probably, the spirit of King Charles II, after all, but involved in the name of this dance, was confused. He would never have thought that a candidate for his crown would be jumping around imitating the wild dances of black slaves from American plantations! This will not lead to good! Just look, a great-great-grandson will get along with some unbecoming American!

The old man looked into the water! Edward VIII married an American divorcee in 1936, for which he renounced the crown. And the history of the British Empire in the twentieth century, far from Charles II, went in a completely different way.

Red Charleston?

The Charleston drew attention even in the country of the victorious proletariat, in the USSR. People liked this dance, which came from the decaying West, but the Soviet ideological authorities did not. People's Commissar Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky, for example, wrote that he considered this dance extremely disgusting and harmful. The People's Commissar said - the People's Commissar did. Or rather, not the people's commissar himself, but the Main Repertory Committee subordinate to him. The performance of American dances on the stage and in Soviet institutions was banned at 1924 year. At the same time, the decree on the ban noted that these dances “... are undoubtedly aimed at the basest instincts. ... they are essentially a parlor imitation of sexual intercourse and all sorts of physiological perversions” . As always, the managing grandfathers took care of the growing youth: they wouldn’t corrupt! Simultaneously with the Charleston, the foxtrot, shimmy and two-step were banned.