How to dance in a black church

|   | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

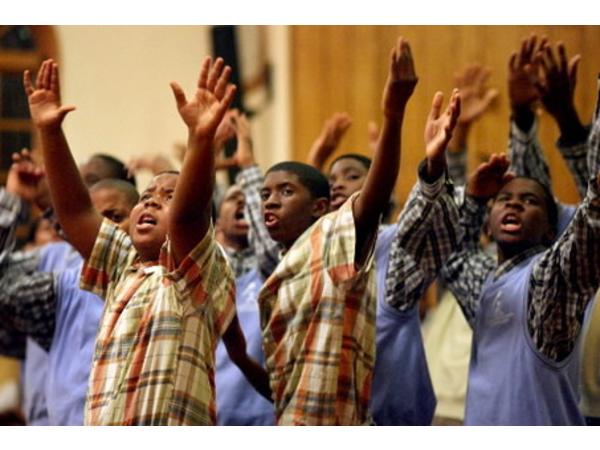

WORSHIP AND ARTS SUNDAY CULTURAL RESOURCES Sunday, September 22, 2013 Tammy L. Kernodle, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator Scriptures: Psalm 149:1-4, Psalm 20:1-5, and Psalm 33:1-4 I. The History/Historical Documents Section Within the spectrum of Black Christianity the practice of worship has taken on different meanings since the first all-black congregations began to appear in the Southern colonies during the Antebellum period. Today worship extends beyond the singing of the choir and the instrumental worship of the musicians to also include multiple forms of praise dancing, gospel miming, holy hip-hop, stepping, and what some call performance art (primarily spoken word performances). The religious roots for African American worship in song and dance can be found in the Old Testament. The concept of worship through song is first introduced in the fifteenth chapter of Exodus when the children of Israel witness the miracle of God parting the Red Sea and subsequently destroying Pharaoh and his army. Moses first engages the Israelites in singing a song of praise (vv. 1-18) and later Miriam, the sister of Aaron, praised God with the timbrel and dance (vv. Throughout the Old Testament, the wonders and miracles of God were responded to with corporate praise. Worship was so central to the covenant between God and his people that He not only designated a specific tribe of people to lead the others into worship (Levites; see Numbers 3), but God also defined the type of worship that should take place in the temple. The eclectic nature of this worshipdancing, singing, and the playing of instrumentshas been reflected in the practices of the Black Church since its beginnings, and these same practices were brought to the Americas by our enslaved foreparents who danced, sang, and played instruments as part of their everyday cultural formation, especially in west Africa. Black Song Traditions and the Black Church In the praise houses, brush harbors, and "secret places" that framed the early worship services of African Americans, various song practices developed. Since most blacks could not read and in many instances it was illegal for them to do so, these early practices relied heavily on call-and-response in order to sustain corporate worship, and the melodies and texts drew on every available sourcehymns sung by white Protestants during the Second Great Awakening, spirituals that slaves crafted out of their understanding of the Bible and God, and African melodies that had been retained and passed down. Although there were marked differences between black church practices in the South and the North, music constituted a larger portion of the worship experience in both locations. Many northern congregations began to advance the arranged spiritual, anthem, and the sacred works of European composer such as Bach and Handel during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The choir increasingly became the important conduit for worship as the 20th century progressed and music ministries came to include multiple choirs performing varied repertoires. The gospel song, as defined first by the compositions of Charles Tindley, Lucie Campbell, and Thomas Dorsey, slowly became a popular song form in many black churches alongside long meter hymns, anthems, and congregational songs.

Clark's work extended out of her role in the COGIC denomination, while James Cleveland's work with choirs stretched across multiple denominations. In addition to multiple recordings with choirs throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, Cleveland's most enduring legacy is the Gospel Music Workshop of America, which has focused on the performance, promotion, and preservation of gospel music.3 Both inspired a new generation of choir directors and songwriters including Hezekiah Walker, Rickey Dillard, Richard Smallwood, Kirk Franklin, and Donald Lawrence, who furthered the popularity of the mass or gospel choir in the late 20th century. The evidence of this influence can be seen in the repertory and performance approaches used by choirs every Sunday morning. The late 1990s also marked the emergence of praise and worship teams in many black churches. The concept of praise and worship was first used in contemporary white church services during the 1970s. Praise and worship grew in popularity in contemporary white evangelical churches and was mass-mediated through the recordings of artists such as Twila Paris and Keith Green.4 Black musicians also began to transition to this style in the 1980s, most notably Andra Crouch and Thomas Whitfield.

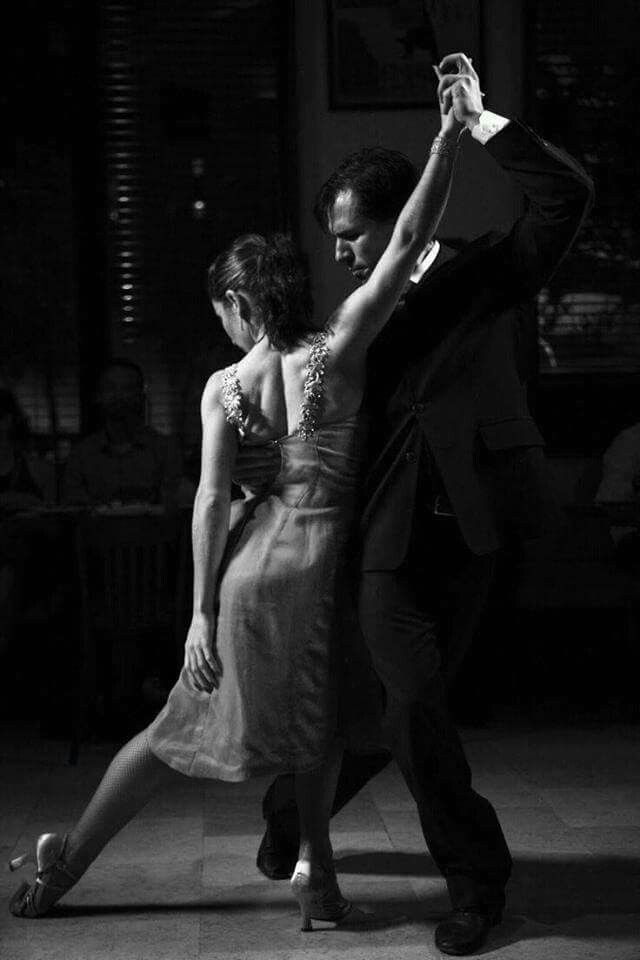

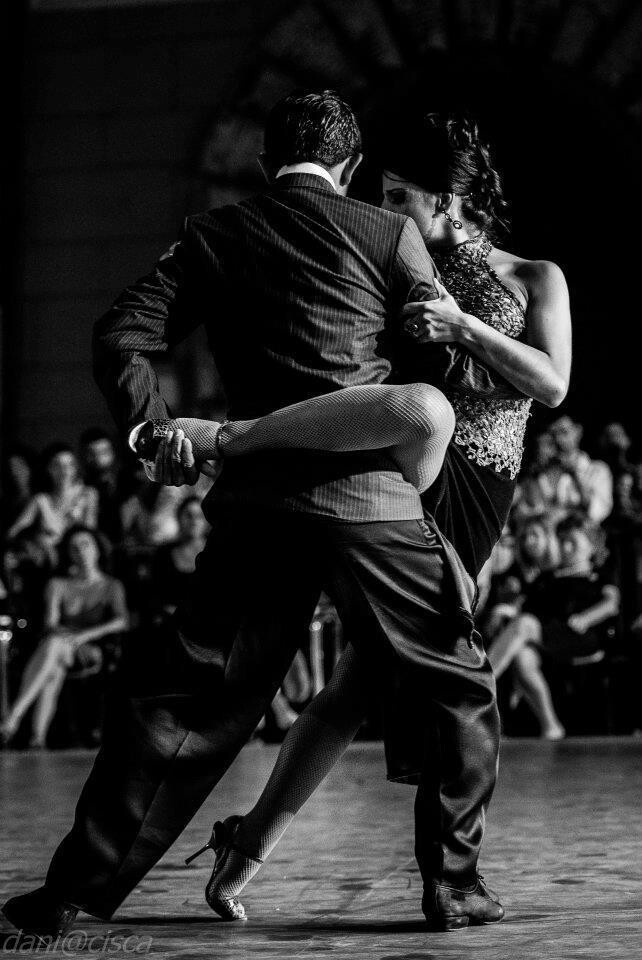

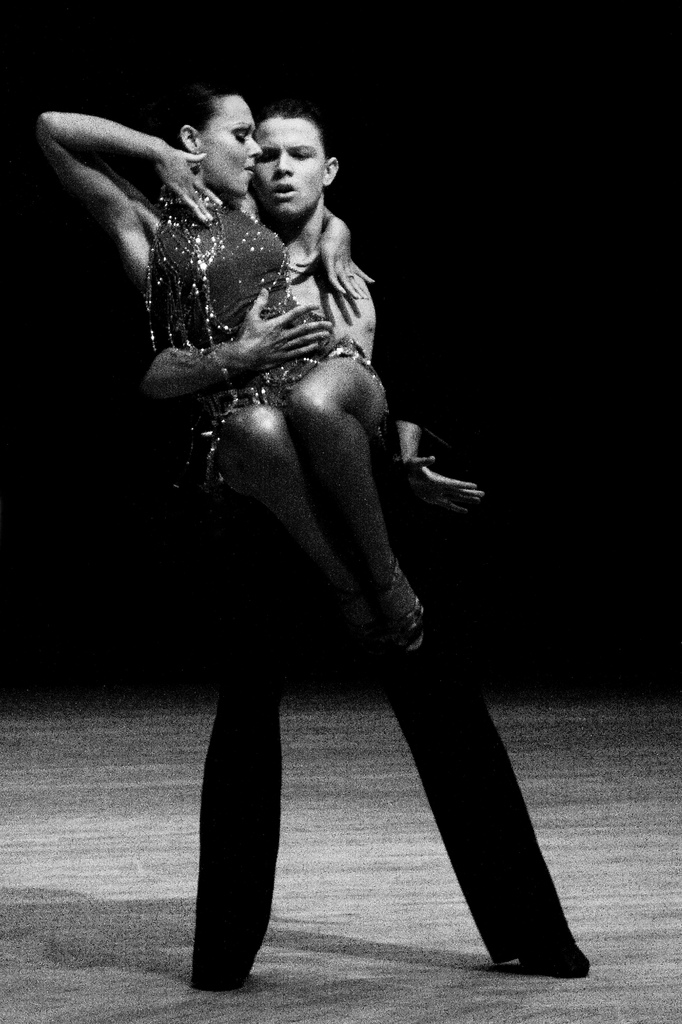

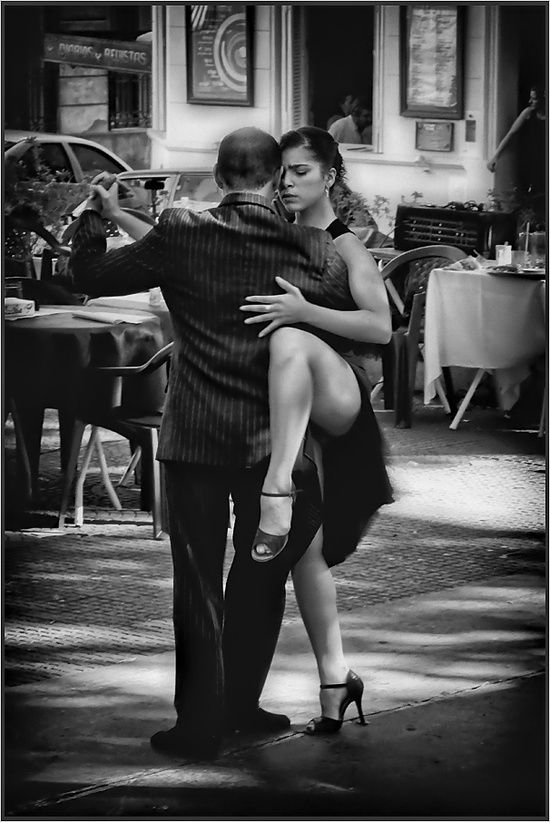

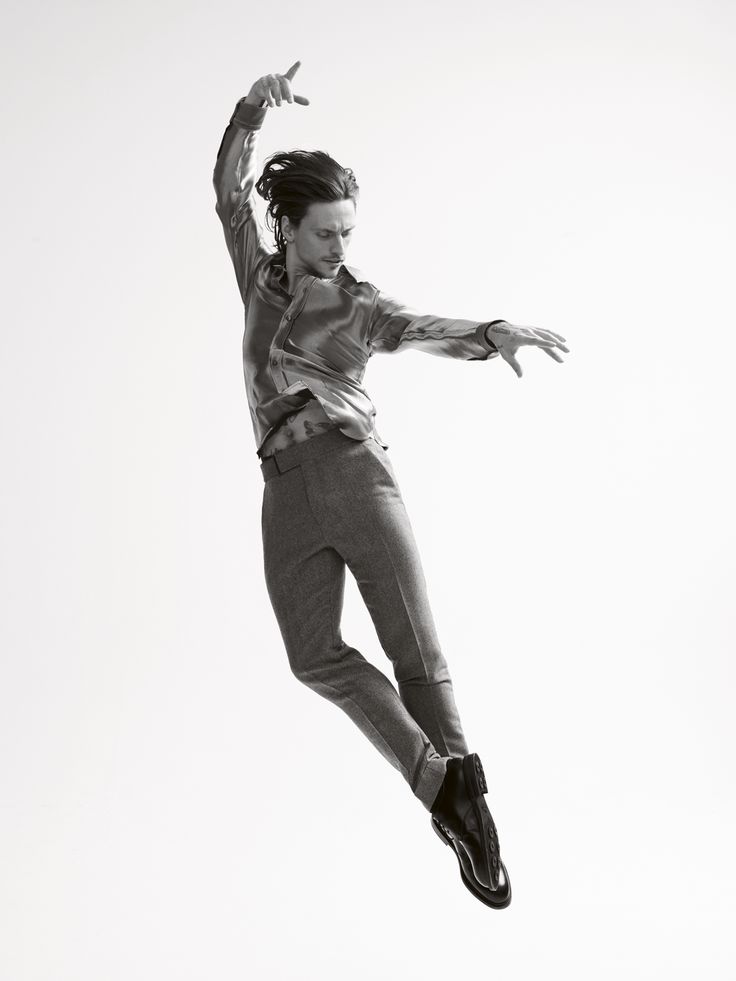

But praise and worship really became popular among black congregations through the recordings of Judith Christie McAllister, Israel Houghton, Joe Pace, and Fred Hammond in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some congregations have adapted the praise and worship format as the core form of musical worship in lieu of the traditional choir and chorus. This has prompted a shift in the personnel comprising some music ministries, as choir directors have given way to worship leaders who are now responsible for the selection of songs and the leading of congregation, singers, and musicians in worship. The popularity of this type of aggregation has also given birth to new song styles and also diversified the context of corporate worship on Sunday mornings. Dance in the Black Church Sacred dance has been a facet of the worship practices of African Americans since these cultural expressions have been documented. Where the song represented the vocalization of praise, dance reflects the physical manifestation of praise. In the praise houses of the early African American religious experience, the ring-shout served as one of the examples of the symbiotic relationship between music and movement within traditional African worship practices. But the ring-shout constituted only one facet of sacred dance in the early church; "shouting" or the embodied response to the movement of the Holy Spirit was also an important facet of worship. In the late 20th century, new forms of dance began to appear within the context of worship. Dance in this new form has taken on many different connotations and representations. One example is the flag/banner ministries, which does not include the engagement in physical dance but in the waving of colored flags or banners (which have specific meanings) throughout the worship service in order to facilitate the movement of the Spirit. The most common form of sacred dance is liturgical dance, which was first introduced to worship services in the 1970s. This type of dance draws on modern, jazz, and Afro-Caribbean dance styles. Many attribute the integration of this practice into worship services to two major influences. First was the popularity of modern dance styles advanced by Alvin Ailey, most notably his religious dance tome "Revelations" and Arthur Mitchell's Dance Theater of Harlem. The second was the emergence of the Sacred Dance Guild and its involvement with black congregations during this period. Started in 1958, The Sacred Dance Guild (SDG) was significant in the resurgence of sacred dance practices in Protestant and Catholic denominations. The Guild diversified its scope in the 1970s and 1980s to include modern, African, and other ethnic traditions, and many of its members began to create the first liturgical dance troupes in black churches.5 The growing popularity of liturgical dance over the past twenty years in black churches has sparked much debate about the role of dance in worship practices, but many have viewed this as an important and vital part of the worship experience. The ministry of the Edmonds brothers has provided the blueprint for numerous gospel mimes. It should also be noted that the incorporation of mime in worship services has also challenged the gendered aspects of who dances in what way in the church, as males dominate this genre and females dominate most of the other genres. Instrumental Worship in the Black Church Since the days of the early temple in the Old Testament, the worship of God with instruments has been an important facet of worship. While trumpets, timbrel, and harps are often referenced in early practices, today the Hammond organ, piano, and in some churches various keyboards, horns, drums, and electric bass frame the most common forms of instrumental worship. Worship through instruments extends beyond simply accompanying choirs, congregational singing, and the pastor. Long before the first notes are sung, or the first Scripture or prayer is offered, the instruments set the atmosphere for worship. II. Biographical and Autobiographical Stories/Personal Testimonies Mattie Moss Clark (19251994) and the Development of the Modern Gospel Style

James Cleveland (19321991)

My Personal Story I've had the unique opportunity to serve in various capacities within the Black Church. For over thirty years, I've spent my Sunday mornings either seated behind a piano, leading a congregation in praise and worship, or directing a choir. I've worked in numerous churches in almost every conceivable denomination, but the most profound experience I've had was during my tenure at the First Baptist Church in Oxford, Ohio. Located west of Dayton, Ohio, and about 35 miles north of Cincinnati, Oxford is a small town with a rich cultural past. When I arrived there in 1997, I had very little knowledge of the city or that it had been a major point of migration for many leaving Mississippi and Alabama during the World War II years. I began attending the First Baptist Church shortly after arriving in Oxford. Although I was reared in the South, I had only heard long meter hymns on the records I checked out at the music library while a student at Ohio State University. But on that first Sunday, I came in contact for the first time with a diversity of black sacred music. The service started with the traditional devotional service. The deacons arranged themselves at the front of the church and one read a Scripture and then another gave a prayer. Then Deacon Jimmie Brown started lining out the song "I Love the Lord He Heard My Cry." The congregation, young and old, instinctively fell right into the song and before long that little church was filled with sound. He sang verse after verse and everyone followed. The rest of the service was filled with everything from devotional songs such as "Can't Nobody Do Me Like Jesus" to gospel songs performed by the choir. But as those deacons and church members got older and transitioned from this world, the devotional service gave way to new songs. Over the years, I transitioned from simply being an observer to a participant. Although I initially eschewed the role of pianist or Minister of Music, in time the Pastor convinced me that my talents were to be used by God in this way. In 2011, I took a leave of absence from First Baptist to pursue a teaching fellowship at another university in another state. But as I sat at the piano for what would be my last Sunday as Minister of Music, I reflected on what I had learned over the years. Deacon Jimmie Brown and the other senior members of that congregation had taught me valuable lessons over the years. The first is that progress is okay, but never discard the great traditions of the past. Even with my love for the contemporary gospel songs of Donald Lawrence, Kirk Franklin, and groups such as Youthful Praise, every Sunday I tried to include hymns and the traditional devotional songs of the previous generation. The second lesson is that music is an important ministry and every song, note, and nuance should be about praise and not entertainment. A music ministry can set or destroy the atmosphere of a service, so one should be focused on the move of the "Spirit" and not what would spotlight an individual. The third lesson is that praise is not just sung but can be embodied through movement. I had never had any experience with praise dancing before First Baptist, and over the years the liturgical dance team and choir collaborated and performed together. I do not believe there is anything more transformative that seeing hands, feet, bodies, voices, and instruments used in corporate praise to God. My thinking and approach to music ministry radically changed during my tenure at First Baptist Church, and I am grateful for the time that had at that little church in Southwestern Ohio. III. Resource and Excerpts

IV. Songs That Speak to the Moment Anthem of Praise (Tenors) (Tenors & Altos) (Tenors) (All) (Tenors) (Altos & Sopranos) / (Tenors) (All) (Tenors) (Rounds) Lift Him up (Sopranos) (Tenors) (Tenors & Altos) (Tenors & Altos & Sopranos) (All) More Than Anything I lift my hands in total admiration unto you You hold me in your arms I love you Jesus The Reason Why I Sing Verse 1: Chorus: Verse 2: And when we cross that river to study war no more Chorus11 V. Audio Visual Aids

VI. Books to Enhance Your Understanding of Music, Dance, and Instrumental Worship

Notes 1. 2. Kernodle, Tammy. "Work the Works: The Role of African America Women in the Development of Contemporary Gospel," Black Music Research Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, Spring 2006, 9799. 3. Maxille, Horace. "James Cleveland." Encyclopedia of African American Music, vol. 1: AG, Emmett Price, Tammy L. Kernodle, and Horace Maxille, Jr., eds. (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press, 2011), 208. 4. Pollard, Deborah Smith. When the Church Becomes Your Party: Contemporary Gospel Music (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2008). 5. "History of the Sacred Dance Guild." Online location: http://www.sacreddanceguild.org/ (accessed March 20, 2013). 6. "Interview with K&K Mime." Online location: http://www.blackgospel.com/interviews/kandkmime/ (accessed March 21, 2013) 7. Dunbar, Paul Laurence. When Malindy Sings (New York, NY: Dodd Mead and Co. 8. Bratcher, Connie Campbell. "A Wonderful Choir." Online location: http://faithpoetry.com/faith5/awonderfulchoir.shtml (accessed March 20, 2013). 9. Anthem of Praise. By Richard Smallwood. Richard Smallwood with Vision: PersuadedLive in D.C. New York, NY: Verity, 2001. 10. More Than Anything. By Lamar Campbell. When I Think about You. Brentwood, TN: Chordant, 2000. 11. The Reason Why I Sing. By Kirk Franklin. Kirk Franklin and the Family. Inglewood, CA: Gospocentric, 1998. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|   | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

fat white man at a black church dance

TikTokUpload

For You

Following

scgreen23

SEAN GREEN

White Peeps at a Black church!! 🤣🤣 #comedy #dancing #churchtiktok

TikTok video from SEAN GREEN (@scgreen23): "White Peeps at a Black church!! 🤣🤣 #comedy #dancing #churchtiktok". original sound.

original sound.

483 views|

original sound - SEAN GREEN

dwwing33

Dwwing33

#fat #whitepeople #blessmyheart

118 Likes, 12 Comments. TikTok video from Dwwing33 (@dwwing33): "#fat #whitepeople #blessmyheart". Fat white man “dancing” . original sound.

4323 views|

original sound - PARADIISE 💞

rudeboyfm

RudeBoy FM

big guy dance! #fyp #funnyvideos #dancechallenge #jamaica #fatmandancing #turkish

19.8K Likes, 517 Comments. TikTok video from RudeBoy FM (@rudeboyfm): "big guy dance! #fyp #funnyvideos #dancechallenge #jamaica #fatmandancing #turkish". original sound.

977.1K views|

original sound - RudeBoy FM

yaritzadiva12

Yaritza ✨

Reply to @kimulari save the video and crop it in your camera roll 😌🌚 #greenscreenvideo #nigerianmusic🇳🇬 #whiteguydancing #afrobeats #comedy #fyp

1. 1K Likes, 58 Comments. TikTok video from Yaritza ✨ (@yaritzadiva12): "Reply to @kimulari save the video and crop it in your camera roll 😌🌚 #greenscreenvideo #nigerianmusic🇳🇬 #whiteguydancing #afrobeats #comedy #fyp". original sound.

1K Likes, 58 Comments. TikTok video from Yaritza ✨ (@yaritzadiva12): "Reply to @kimulari save the video and crop it in your camera roll 😌🌚 #greenscreenvideo #nigerianmusic🇳🇬 #whiteguydancing #afrobeats #comedy #fyp". original sound.

82.7K views|

original sound - 🥸

tylerthadon

Tyler Breshears

🤣FAT White BOII goes CrA-zzzz🤣. #sanantonio #bar #breakdance #viral #fat #fatboii #foryou #foryoupage 🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣

TikTok video from Tyler Breshears (@tylerthadon): "🤣FAT White BOII goes CrA-zzzz🤣. #sanantonio #bar #breakdance #viral #fat #fatboii #foryou #foryoupage 🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣". Fat white boii. original sound.

674 views|

original sound - Tyler Breshears

twenzeez

Twen!

why wouldn’t it? 😝 #lucki #big #buff #black #dude #dancing #fy #fyp #viral #vbucksglitchtohelpmerecievehoes

393 Likes, 22 Comments. TikTok video from Twen! (@twenzeez): "why wouldn’t it? 😝 #lucki #big #buff #black #dude #dancing #fy #fyp #viral #vbucksglitchtohelpmerecievehoes". luckiiiiiiii.

TikTok video from Twen! (@twenzeez): "why wouldn’t it? 😝 #lucki #big #buff #black #dude #dancing #fy #fyp #viral #vbucksglitchtohelpmerecievehoes". luckiiiiiiii.

17.9K views|

luckiiiiiiii - 👁

montreal211

Montreal Fisher

I'll guess I'll do for yall. #biguysoftictok #fyp #dance #jigglejiggle #black #fatpeople

257 Likes, 28 Comments. TikTok video from Montreal Fisher (@montreal211): "I'll guess I'll do for yall. #biguysoftictok #fyp #dance #jigglejiggle #black #fatpeople". Thighs Jiggle Wiggle.

17.3K views|

Thighs Jiggle Wiggle - Tik Toker

owen.horn18

Owen Horn

Dennis having is little dance sesh #fyp #dance #blackdude #fat #awesomedude #sus

190 Likes, 7 Comments. TikTok video from Owen Horn (@owen.horn18): "Dennis having is little dance sesh #fyp #dance #blackdude #fat #awesomedude #sus". "Dance if you will never touch 🐱 in your life" "mf named Dennis". Why are ppl using this.

TikTok video from Owen Horn (@owen.horn18): "Dennis having is little dance sesh #fyp #dance #blackdude #fat #awesomedude #sus". "Dance if you will never touch 🐱 in your life" "mf named Dennis". Why are ppl using this.

5112 views|

Why are ppl using this - 🤍🕊

pan2tuii

Dương💁♂️

Fat Black guy dancing #fat #dancing #dance #editor #edit

421 Likes, 21 Comments. TikTok video from Dương💁♂️ (@pan2tuii): "Fat Black guy dancing #fat #dancing #dance #editor #edit". nhạc nền - Fb: Dương Lưu Văn.

31.5K views|

nhạc nền - Fb: Dương Lưu Văn - Dương💁♂️

what blacks do in American churches At least in the "black" churches of America, whose parishioners are entirely American blacks. Why services in African-American churches are more like parties, and you can only leave the temple by raising your finger up, says Lenta.

ru.

ru. Anyone who has ever visited an African-American church at least once in his life noted that you will not see such a warm welcome and fun even at the grandmother's jubilee. There is no smell of incense here, they are not asked to keep silence and stand still. The service in the "black" church is more like a carnival or a holiday, which has long been the subject of jokes. The difference between "black" and "white" churches is devoted to more than one stand-up, blog article and episode in the popular television series.

And if the Protestant church is Protestant because its morals are less severe than in the Catholic and Orthodox ones, then the last service in the "black" church may seem not just strange, but even blasphemous. Indeed, an Orthodox priest during the liturgy will not dare to insert a couple of lines from the new track of Eldzhey or Nikita Dzhigurda into the prayer. For the pastor of the “black” church, during the service, rapping or praying for the new Beyoncé album is a common thing.

However, the "black" church is basically not about fun, songs and dances. African American worship is part of the culture of the black population of the United States, who has known all the horrors of slavery and discrimination, but still finds the strength to thank and glorify God.

We are here because of faith

By the time Africans arrived in what would later become the United States of America, they had lost much of their culture and spiritual heritage. The reason was either that they were losing contact with their community and ancestors, or the brutal slave system of the early colonial period, which separated families.

According to one version, the Africans have already brought Christianity with them, it was already spread in some regions of Africa. In particular, scientists date the traces of Christian mysticism in the north of the mainland to the end of the 2nd century, and part of the kingdoms in the Nile Valley was already Christian by the 7th century.

This is not surprising, because Africa was one of the first continents to which the teachings of Christ spread. In Matthew's gospel, the holy family flees to Egypt, or "the land of Ham," to avoid the massacre of the infants, and finds refuge among its black inhabitants. That is why black slaves were especially offended by the fact that, oppressing them, white slave owners willingly referred to the Holy Scriptures.

Related materials:

According to the Gospel, Ham, the son of Noah who escaped the flood, was not the most pleasant person. Seeing his drunken father sleeping, he did not cover his nakedness, but went to tell his brothers about what he saw. In Christianity, his act began to be interpreted as a sin - disrespect for the father, rudeness. There are many interpretations of this story, but what matters is how it ended.

Ham's sin was paid for by his son Canaan, and with him all the African slaves. According to legend, Noah cursed his grandson, saying: “Cursed be Canaan; he shall be a servant of servants to his brothers” (Genesis 9:25). It was this line of Scripture that was used as an argument by white theologians - the defenders of slavery.

It was this line of Scripture that was used as an argument by white theologians - the defenders of slavery.

Related materials:

Creators of evil often used the Bible to justify their actions. However, until the letter of the Apostle Paul to the Galatians, which says: “There is no more Jew, no Greek, no slave, no free man, no man and no woman, you are all one in Christ Jesus,” the slave owners apparently did not finish reading.

Photo: Lucas Jackson / Reuters

White slave owners quickly forgot that they themselves fled Europe from religious persecution, and therefore, until the abolition of slavery, many "black" Christian churches were illegal. Just like the early Christians, the slave Christians gathered underground in the so-called hush harbors. To coordinate their plans, they used secret codes - in particular, the songs "Steal Away to Jesus" and "Gospel Train" that have become classics of the spiritual culture of African Americans.

Steal Away to Jesus

The church for slaves was not only a place where they could turn to God. Here people could communicate, share news, and, most importantly, get an education. According to the Bibles that the white opponents of slavery passed to the black priests, the slaves learned to read and write.

Here people could communicate, share news, and, most importantly, get an education. According to the Bibles that the white opponents of slavery passed to the black priests, the slaves learned to read and write.

Rarely in the "quiet havens" were accusations and threats of revenge against the cruel planters. The sermons said that God sees everything, and punishment will follow from him, but for now everyone needs to take care of themselves.

Prayer in a Texas "black" church

Photo: Joe Raedle / Getty Images

A distinctive feature of the "black" church was and remains the language of the sermon, not at all similar to that used during worship in the "white" churches. It appeared because in their sermons the clergy encoded special messages that the slave owner should not have recognized. In addition, the priest during the service needed not only to pray, but also to entertain, enlighten and tell the parishioners about important news, and for such purposes, the usual reading of the Gospel is not suitable.

So the "black" church initially became not only a place of worship to God, but also a haven where slaves could find comfort and justice.

Sing, dance and stay away from whites

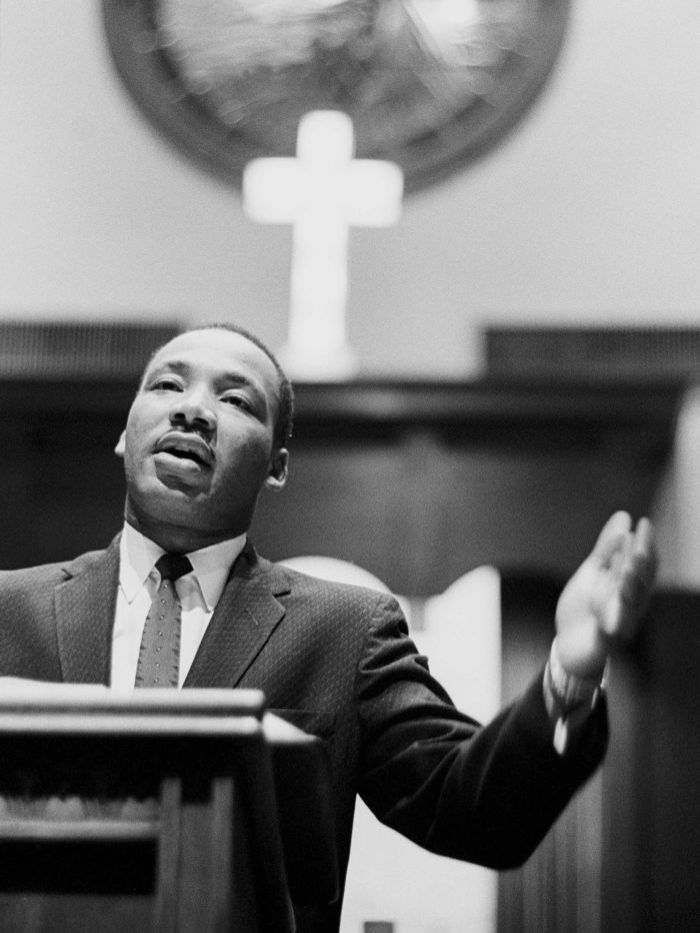

The history of the "black" churches is inextricably linked with the movement to abolish slavery. She was a help and support to those who fought for their civil rights. Many famous African American freedom fighters, including Martin Luther King Jr., were priests.

Many of the black civil rights activists in the United States were clergymen: James Luther Bivel, Ralph Abernathy, Claude William Black, and others. The most prominent of these was the Baptist preacher Martin Luther King Jr. He was killed by a sniper on April 1968 years old.

The first united African-American community, the Free African Society, was founded in Philadelphia in 1787. It established contacts with religious organizations in other cities. Five years later, members of the Society began building the first independent "black" church. By this time, a large number of states in the north of the United States had already renounced slavery, and the law did not interfere with them, which cannot be said about the south of the country, where the power of the planters was still extremely great.

By this time, a large number of states in the north of the United States had already renounced slavery, and the law did not interfere with them, which cannot be said about the south of the country, where the power of the planters was still extremely great.

Related materials:

Only a century later, in 1865, when the Civil War ended and slavery was put an end to, blacks throughout the country stopped hiding in "quiet havens." And yet, former slaves were not allowed into churches on an equal basis with whites: they, for example, had to sit on separate pews. Not all blacks were ready to put up with segregation in the House of God, and "black" churches began to spread rapidly in the United States.

Priest praying

Photo: Joshua Lott / Getty Images

However, the reason for the division was not only segregation and racism, the peculiarities of worship also played a role. The "black" services were held at a completely different pace than the "white" ones. They were distinguished by emotionality, elements of African culture, stories about the suffering of black slaves and a special southern flavor were woven into them. The priest did not just read a sermon, he sang a song of praise to God, and the parishioners sang along with him and supported him with remarks from the audience.

They were distinguished by emotionality, elements of African culture, stories about the suffering of black slaves and a special southern flavor were woven into them. The priest did not just read a sermon, he sang a song of praise to God, and the parishioners sang along with him and supported him with remarks from the audience.

In 1986, to get rid of white influence in African American churches, the National Baptist Convention was organized. Ten years later, it already had three million black Americans. The second largest "black" Christian organization was the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In the future, the number of such organizations only grew.

Black, run!

Paradoxically, the more influence the "black" churches gained, the more they were oppressed. By the middle of the 20th century, when the black civil rights movement gained sufficient strength, African American churches became a solid social and political base for former slaves.

"Black" churches became a kind of cornerstone of the African American civil society - this important role allowed them to raise people to fight for their rights. However, not everyone did this: some black holy fathers refused to combine religion and politics.

However, not everyone did this: some black holy fathers refused to combine religion and politics.

Related materials:

Soon the churches became real strongholds of resistance and mobilization centers for the black population, platforms where activists developed plans for the struggle for equality. Their involvement became so obvious that they were overcome by the anger and rage of those who believed that blacks should use separate elevators and sit away from whites on public transport.

The Ku Klux Klan is a radical ultra-right organization in the United States, created immediately after the end of the Civil War in 1865. The movement professes nationalism, racism and subsequently anti-communism, arranged lynching of abolitionist activists and defenders of the rights of blacks. In its heyday, the number of the organization reached six million people, at present, according to various estimates, it ranges from five to eight thousand.

In September 1963, a Baptist church in Alabama was attacked. Four children died. It was just one of the massacres that were usually the responsibility of the Ku Klux Klan. However, black rights activists showed courage and perseverance, and a year after this attack, racial segregation in the United States was officially abolished.

Four children died. It was just one of the massacres that were usually the responsibility of the Ku Klux Klan. However, black rights activists showed courage and perseverance, and a year after this attack, racial segregation in the United States was officially abolished.

By this time it became obvious that the "black" church is not a single organization, it is a rather general concept, which includes more than one denomination. At 19In 1990, there were already seven of them: the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ), the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church (CME), the National United Baptist Meeting of the USA (NBC), the National Independent Baptist Meeting of America (NBCA), Progressive National Baptist Congregation (PNBC) and Church of God in Christ (COGIC).

However, despite the growth in the number of denominations, in the 21st century "black" churches face a new problem: the outflow of parishioners. This is largely due to the improvement in the situation of the black population of the United States: teenagers can sit with white classmates at the same desk, they no longer need to consider themselves part of "black America" - they can simply be Americans, without any reservations.

Related materials:

In addition, earlier people did not have unlimited access to information: what was said in the church was the law and guidance in life. Now teenagers can go online, watch a documentary about black church corruption, and wonder why my family makes donations every week, and instead of a new church organ, the priest gets a new car?

Older parishioners say that when they were younger, they didn't ask questions. They did as their ancestors did, as they were told in the church. However, today's teenagers question any authority. They learn from examples rather than blindly following directions. “If I see how vile my churchly father does every day, why should I follow his advice on how to live right?” - about such questions are asked by teenagers.

In a black-and-black church...

"Black" churches, of course, are strikingly different from those where white people come to humbly stand and pray before the face of the Son of God. A mulatto high school student from North Carolina shared a religious-cultural embarrassment from her family history. Ashley's father is black, mother is white. Once, at the funeral of a relative, the white part of the family mourned quietly for the deceased, while the black part sang and loudly glorified the Lord, who was preparing to receive his servant into the kingdom of heaven. The incident almost provoked a family scandal. This episode vividly illustrates the differences in black and white American religious cultures.

Ashley's father is black, mother is white. Once, at the funeral of a relative, the white part of the family mourned quietly for the deceased, while the black part sang and loudly glorified the Lord, who was preparing to receive his servant into the kingdom of heaven. The incident almost provoked a family scandal. This episode vividly illustrates the differences in black and white American religious cultures.

Black churches also have unwritten rules that are best adhered to. First: you need to go to church in special festive clothes. The older generation puts on ironed and starched shirts and dresses on Sundays, hats are obligatory for women. Black aunty hats are a special wardrobe item that gets a lot of attention.

Second, there is a special custom in churches to sit down. Elderly and respected parishioners sit in the front rows. The so-called mother of the church, one of the oldest parishioners, also sits there. The mother of the church has unquestioned authority - she, for example, can reprimand someone's daughter for wearing a too short skirt and covering her legs with a scarf.

Third: alms are an integral part of worship. There may be several of them during the service. Going to the toilet and generally leaving before the collection of alms begins is highly discouraged. If there is nothing to donate, you can simply touch the container in which the money is collected, but in no case refuse to donate. Another “better not” is to agree to sit down when the priest asks if you would like to sit down and rest. The optimal response to such a proposal would be: “No, holy father, continue preaching, we are standing here so beautifully!” Even if you have been standing for two hours, do not sit down.

Service in an African American church

Photo: Sean Gardner / Reuters

Another interesting feature of the "black" church: when African Americans leave the temple, they raise their index finger. It's funny that no one can explain the origin of this gesture. The most common version is that the slaves thus made it clear that they had received permission from the owner to leave. The reason for the many jokes was that worship in the African American church is not limited by time. While in other temples of God the priest sets aside a certain time for prayer and, as a rule, does not go beyond it, black pastors follow the divine stream and can preach for several hours, sometimes inserting lines from the last song of Chris Brown into their speech, without omitting obscene scolding, or explaining the divine meaning of the title of Beyoncé's album "Lemonade". By the way, the whole sermon is conducted with musical accompaniment.

The reason for the many jokes was that worship in the African American church is not limited by time. While in other temples of God the priest sets aside a certain time for prayer and, as a rule, does not go beyond it, black pastors follow the divine stream and can preach for several hours, sometimes inserting lines from the last song of Chris Brown into their speech, without omitting obscene scolding, or explaining the divine meaning of the title of Beyoncé's album "Lemonade". By the way, the whole sermon is conducted with musical accompaniment.

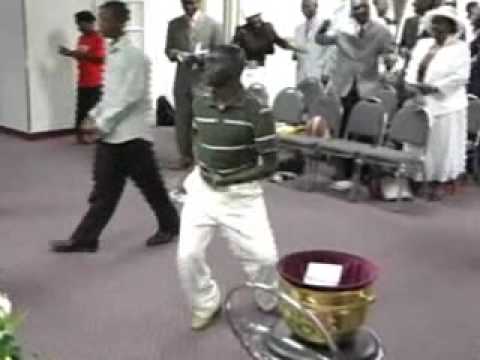

During the service, someone may begin to convulse - this means that a "black divine spirit" (black holy spirit) descended on a person, which he does not resist.

Particular attention should be paid to interaction with the priest. All his statements must be answered with cries of “Amen!”, “The Lord is with us!”, “So be it!”, “Yes, priest, preach!” - and stuff like that. If the priest says, "Turn to your neighbor and say 'neighbor'," you must follow the instructions. No one knows why, but during the service, parishioners are asked several times to do this procedure. It is usually accompanied by hugs. In general, parishioners are always welcome in the "black" churches, and the service here is like a holiday, and not like a typical worship of God.

No one knows why, but during the service, parishioners are asked several times to do this procedure. It is usually accompanied by hugs. In general, parishioners are always welcome in the "black" churches, and the service here is like a holiday, and not like a typical worship of God.

***

African American Christians have come a long and hard way from underground gatherings of uneducated slaves to the creation of official religious organizations that are fully involved in US political life. Features of worship, which absorbed the culture of blacks, the features of the life of their ancestors, surprise anyone who gets acquainted with this culture. The cheerfulness and spirituality with which the descendants of black slaves approach the service of God, and in general to life, make one admire the fortitude of the spirit of people who spent hundreds of years in slavery, but managed to free themselves.

Black Church

At the height of summer, guests come to New York: if their own prefer to flee the city from the heat, then strangers do not pay attention to it. Among the relatively recent sights that have appeared on the tourist map are the African-American churches of Harlem. This renaissance district attracts foreign visitors with its exoticism - jazz concerts in historic clubs, original cuisine of the American South and worship in black churches. The latter have become so popular that they open galleries on the second floor especially for foreign tourists, where you can enjoy the service without interfering with its course. However, this is not an attraction, but a rare spiritual experience.

Among the relatively recent sights that have appeared on the tourist map are the African-American churches of Harlem. This renaissance district attracts foreign visitors with its exoticism - jazz concerts in historic clubs, original cuisine of the American South and worship in black churches. The latter have become so popular that they open galleries on the second floor especially for foreign tourists, where you can enjoy the service without interfering with its course. However, this is not an attraction, but a rare spiritual experience.

We associate religion with goodness. We have learned to see in the church a temple of quiet, profound piety. Who would think of dancing to a Bach chorale? Going under the church vaults, we bow our heads and lower our voices. However, such an attitude towards faith is not only not universal, but also not indisputable.

"Religion," wrote Georges Bataille, "requires at least excess. It requires a feast, the apex of which is ecstasy. "

"

To see, if not share, I went to an African-American church in a small town in New Jersey. Unlike the guide-booked Harlem, whites do not come here often. Even the biblical characters in the religious paintings hung in the hall have black faces. Among the parishioners, I noticed only three white women, who, apparently, were well known here.

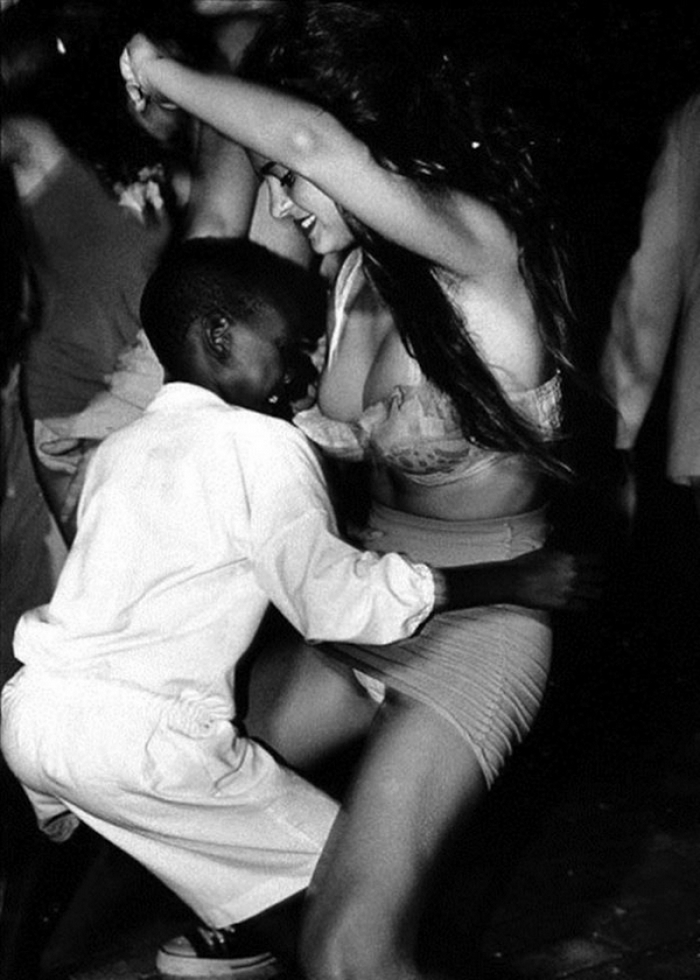

To be honest, the service was more like a rock concert. Parishioners of all ages, from children to matrons, gladly led themselves into a frenzy. They sang, clapped their hands, burst into cries of delight. Every now and then someone started to dance. The most violent fell into a trance. One smartly dressed old woman in a special Sunday hat struggled, falling to the floor. She was caringly supported by her grandchildren. This was just that "excess", overflowing religious feeling.

There was nothing threatening or frightening in all that was happening. People praised God and their faith without restraining their emotions. For them, going to church on Sunday was the highlight of the week. A real holiday in its much more ancient than we are used to understanding: an ecstasy that allows you to merge with the communal body of the community, to feel like a part of the whole. Here they did not just pray to God, here they merged with him - in a much more direct sense of the word than it seems possible to us.

A real holiday in its much more ancient than we are used to understanding: an ecstasy that allows you to merge with the communal body of the community, to feel like a part of the whole. Here they did not just pray to God, here they merged with him - in a much more direct sense of the word than it seems possible to us.

Unable to share someone else's enthusiasm, I, the only one in the church, looked at what was happening from the side, and even sitting. The storm of other people's emotions rather oppressed me than inspired me. But that was my problem. The rest, laughing and crying, experienced deep delight. I have never seen such an open manifestation of religious feeling, capable, as it, in fact, should literally drive a person out of himself.

The pastor - tall, young, athletic, dressed in an impeccable suit, in a white shirt with an exquisitely selected tie, did not look like a fanatic, but he led the service like a shaman. The pastor tossed about on the podium like a hurricane. He sang and shouted his sermon. The words merged into a groan, then into a hymn. His shirt was wet, his elegant Italian jacket blackened with sweat. Without releasing the microphone, Page selflessly drove himself to exhaustion. The frantic dance of his prayer mesmerized everyone. The parishioners participated in the joy of soul and body. Skillfully inflaming the flock, Page heated the hall. When the tension reached its limit, he froze in place. An electric spark seemed to pass through it. Twitching convulsively, the pastor began to heartfeltly and solemnly shout out non-existent words in angelic languages.

He sang and shouted his sermon. The words merged into a groan, then into a hymn. His shirt was wet, his elegant Italian jacket blackened with sweat. Without releasing the microphone, Page selflessly drove himself to exhaustion. The frantic dance of his prayer mesmerized everyone. The parishioners participated in the joy of soul and body. Skillfully inflaming the flock, Page heated the hall. When the tension reached its limit, he froze in place. An electric spark seemed to pass through it. Twitching convulsively, the pastor began to heartfeltly and solemnly shout out non-existent words in angelic languages.

The Holy Spirit, as Pentecostals believe, descends upon the righteous. The sign of chosenness is the ability to glossolalia, that is, the ability to speak "angelic languages". I've read about it before, of course, but I've never heard it myself. Now it happened.

Today, say theologians, there is a mighty renaissance of the most archaic cults. The 21st century promises to be the century of the return of the most ancient, original forms of religious life. Philip Jenkins, a columnist for The Atlantic Monthly, wrote of such a restoration: “The West is not yet aware that the world has entered the era of a new Christian revolution. Today the centers of Christianity are moving to the Global South, to the third world countries.”

Philip Jenkins, a columnist for The Atlantic Monthly, wrote of such a restoration: “The West is not yet aware that the world has entered the era of a new Christian revolution. Today the centers of Christianity are moving to the Global South, to the third world countries.”

Demographic shifts are accompanied by a doctrinal revolution. The southern church professes Christianity in its most orthodox version, coming from the New Testament. Rejecting the Western liberal tradition with its allegorical interpretation of the gospel texts, Third World Christianity follows the spirit and letter of Scripture. The main thing here is the supernatural beginning. As one African bishop said, we don't read the Bible, we do what it says. Following the path of restoration, the southern church is restoring practices and rituals long forgotten in the West. What liberal Christians in the West consider to be obsolete medieval prejudices, the southern church considers to be a living tradition based on the authority of Holy Scripture.

20-21).

20-21). Despite the diversity of structure and form that each of these song forms reflected, each articulated a theology of transcendence that governed the lives of these people. The black sacred song became central in the survival of black people through all of the social, economic, and political influences that framed black life through Emancipation, migration, and segregation.

Despite the diversity of structure and form that each of these song forms reflected, each articulated a theology of transcendence that governed the lives of these people. The black sacred song became central in the survival of black people through all of the social, economic, and political influences that framed black life through Emancipation, migration, and segregation.

2

2 It is defined by small ensembles ranging from 37 members, accompanied by a range of instruments from only a piano to praise bands who engage the congregation in singing songs that precipitate energetic but also reverent praise. The text of the songs, which are generally simple to sing and in which verses or refrains are recited over and over, is either projected on a large screen or printed in church bulletins.

It is defined by small ensembles ranging from 37 members, accompanied by a range of instruments from only a piano to praise bands who engage the congregation in singing songs that precipitate energetic but also reverent praise. The text of the songs, which are generally simple to sing and in which verses or refrains are recited over and over, is either projected on a large screen or printed in church bulletins. Songs such as "Highest Praise" (Pace), "Blessed" (Hammond), and "We Worship You" (Houghton) have replaced the traditional lining out hymns or devotional songs such as "I'm a Soldier (in the Army of the Lord)" in many churches. The popularity of praise and worship has not only marked changes in repertory but also practice as many congregations have replaced the traditional devotional services led by the deacons with 3040 minutes of praise and worship.

Songs such as "Highest Praise" (Pace), "Blessed" (Hammond), and "We Worship You" (Houghton) have replaced the traditional lining out hymns or devotional songs such as "I'm a Soldier (in the Army of the Lord)" in many churches. The popularity of praise and worship has not only marked changes in repertory but also practice as many congregations have replaced the traditional devotional services led by the deacons with 3040 minutes of praise and worship.

One of the most recent forms of dance to emerge in black congregations is mime, which is also referred to as gospel mime. This ministry draws from pantomime traditions that involve the acting out of texts or songs with body motions and facial expressions. Practitioners typically paint their faces in the white makeup that has defined the secular tradition. The practice was formally introduced to black worship services in the late 1980s by brothers Karl and Keith Edmonds, commonly known as K&K Mime. They have been showcased by such gospel luminaries as Dr. Bobby Jones, Kirk Franklin, and Donnie McClurkin, and are now identified as the "Godfathers of Gospel Mime."6

One of the most recent forms of dance to emerge in black congregations is mime, which is also referred to as gospel mime. This ministry draws from pantomime traditions that involve the acting out of texts or songs with body motions and facial expressions. Practitioners typically paint their faces in the white makeup that has defined the secular tradition. The practice was formally introduced to black worship services in the late 1980s by brothers Karl and Keith Edmonds, commonly known as K&K Mime. They have been showcased by such gospel luminaries as Dr. Bobby Jones, Kirk Franklin, and Donnie McClurkin, and are now identified as the "Godfathers of Gospel Mime."6 Other churches have also integrated step teams and Holy Hip Hop dance teams into their youth ministries as a means of offering new ways for young people to express themselves. All of these ministries point to the various ways in which contemporary congregations have sought to expand the context of worship and reconnect with African practices that married music and worship with movement.

Other churches have also integrated step teams and Holy Hip Hop dance teams into their youth ministries as a means of offering new ways for young people to express themselves. All of these ministries point to the various ways in which contemporary congregations have sought to expand the context of worship and reconnect with African practices that married music and worship with movement. Instrumental interpretations of hymns and/or well-known gospel songs serve as the prelude to worship, but throughout the service musicians are instrumental in facilitating the movement of the "Spirit," transitioning from one moment to the next and shaping the overall tone of the service. Too often one can overlook the importance of instrumental worship, but it has proven to be one of the most influential factors in establishing and progressing the flow of the worship service.

Instrumental interpretations of hymns and/or well-known gospel songs serve as the prelude to worship, but throughout the service musicians are instrumental in facilitating the movement of the "Spirit," transitioning from one moment to the next and shaping the overall tone of the service. Too often one can overlook the importance of instrumental worship, but it has proven to be one of the most influential factors in establishing and progressing the flow of the worship service. Within a year of her arrival, she discovered the Church of God in Christ (COGIC), joined the church, and became director of the choir at Bailey Temple COGIC. Her compositional and musical abilities led to her appointment as the music director of the Southwest Jurisdiction of COGIC. She later became the international president of the denomination's music department, through which she mentored a number of talented singers and musicians, including Rance Allen, Vanessa Bell Armstrong, and Walter Hawkins. Clark was the dominant force behind the choir movement in the COGIC denomination and is credited with introducing intricate and innovative performance approaches to gospel arrangements. In 1958, she became one of the first to record a gospel choir and in her lifetime she penned more than seven hundred songs, recorded twenty albums, and dramatically shaped harmonic and vocal practices in gospel music. She was central in shaping the repertory of the COGIC denomination until her death in 1994.

Within a year of her arrival, she discovered the Church of God in Christ (COGIC), joined the church, and became director of the choir at Bailey Temple COGIC. Her compositional and musical abilities led to her appointment as the music director of the Southwest Jurisdiction of COGIC. She later became the international president of the denomination's music department, through which she mentored a number of talented singers and musicians, including Rance Allen, Vanessa Bell Armstrong, and Walter Hawkins. Clark was the dominant force behind the choir movement in the COGIC denomination and is credited with introducing intricate and innovative performance approaches to gospel arrangements. In 1958, she became one of the first to record a gospel choir and in her lifetime she penned more than seven hundred songs, recorded twenty albums, and dramatically shaped harmonic and vocal practices in gospel music. She was central in shaping the repertory of the COGIC denomination until her death in 1994.

As a composer and arranger he also contributed a number of songs that became standards in the repertory of gospel choirs"Peace Be Still," "I've Been in the Storm Too Long," and "Lord Do It for Me."

As a composer and arranger he also contributed a number of songs that became standards in the repertory of gospel choirs"Peace Be Still," "I've Been in the Storm Too Long," and "Lord Do It for Me." Most of all I had no idea that the few black churches that were located in Oxford had been great incubators of black cultural traditions.

Most of all I had no idea that the few black churches that were located in Oxford had been great incubators of black cultural traditions. Sunday after Sunday for the first ten years I was living and worshiping in Oxford this scene was repeated.

Sunday after Sunday for the first ten years I was living and worshiping in Oxford this scene was repeated. I unfortunately did not master the practice of long meter hymns, but I one day hope to, and I will try wherever I am to stress its importance to the next generation of musicians.

I unfortunately did not master the practice of long meter hymns, but I one day hope to, and I will try wherever I am to stress its importance to the next generation of musicians. I came to realize during that period of my life that when the ministries of music and movement work in tandem with the ministry of the Word, lives can be transformed and the world around you can be changed.

I came to realize during that period of my life that when the ministries of music and movement work in tandem with the ministry of the Word, lives can be transformed and the world around you can be changed. "

" You're the reason why I sing

You're the reason why I sing Harris, "In the Life of the Church, Praise and Worship Leaders Play a Key Role," March 30, 2012; online location: http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2012-03-30/local/35446333_1_praise-and-worship-worship-leader-choir-director.

Harris, "In the Life of the Church, Praise and Worship Leaders Play a Key Role," March 30, 2012; online location: http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2012-03-30/local/35446333_1_praise-and-worship-worship-leader-choir-director. "To experience Ailey's dynamic suite of spirituals is like being in church," one enthusiast suggested.

"To experience Ailey's dynamic suite of spirituals is like being in church," one enthusiast suggested. Readings in African American Church Music and Worship. Chicago: GIA Publications, 2001.

Readings in African American Church Music and Worship. Chicago: GIA Publications, 2001. Boyer, Horace. "Thomas Dorsey: Father of Gospel Music." Black World, July 1974, 24.

Boyer, Horace. "Thomas Dorsey: Father of Gospel Music." Black World, July 1974, 24. , 1903).

, 1903).