How to dance ballet without shoes

Footloose: Dancing Barefoot

Lori Belilove & The Isadora Duncan Dance Company members sport bare feet in Duncan’s Bacchanal. (Vladimir Lupovsky)

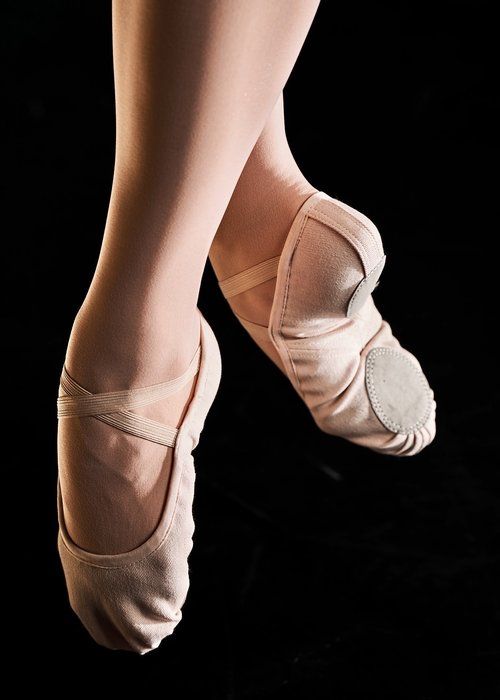

When you’re sporting a pair of jazz shoes or ballet slippers, you can throw off strings of chaînés and multiple turns without a problem. But when you shed your footwear for modern class, everything changes. Your feet get sweaty and stick to the floor, making your movements jerky and uncomfortable. And those triples you can pull off in ballet shoes? Not happening.

Learning to dance barefoot like a pro takes time and patience. But for aspiring modern and contemporary dancers, the ability to move seamlessly without shoes is essential. And even ballerinas and commercial dancers can benefit from having this skill up their sleeves; you never know when a choreographer will ask you to shed your shoes. DS talked to the pros about the trials—and joys—of dancing barefoot.

Feeling the Floor, Then and Now

The history of barefoot dancing in the U. S. begins with Isadora Duncan, who shocked early-20th-century audiences by refusing to wear shoes when she performed. Duncan’s bare feet were a rebellious act, representing her desire to push dance beyond the rigid confines of classical ballet.

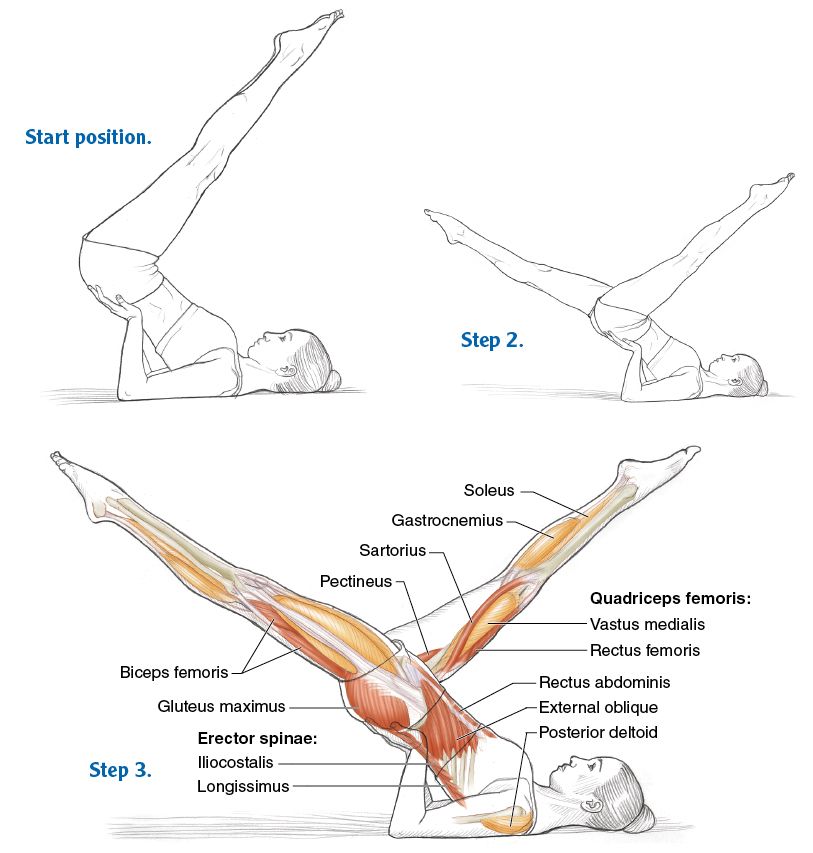

But there’s another side to this story, too. Some modern dance innovators, including Martha Graham, actually adopted the practice of dancing barefoot for practical reasons: Without shoes, Graham’s dancers could maintain better balance and stability. Emily D’Angelo, a current member of Lori Belilove & The Isadora Duncan Dance Company, enjoys working barefoot for the same reasons. “When you’re barefoot, you have a larger area of contact with the floor, which makes balancing easier,” she says. “Your feet can widen into the floor and use their natural moisture to make a connection.” Next time you’re feeling frustrated in modern class, remember this: While your pirouettes may be suffering, your balance has probably never been better.

Making the Transition

Madelyn Ho and Justin Kahan in Paul Taylor’s Esplanade (Tom Caravaglia)

While D’Angelo grew up dancing barefoot, most dancers don’t begin to do so until later in their training. Taylor 2 dancer Madelyn Ho had never danced shoeless until her first college modern class. “It was so weird not having anything on my feet,” she remembers. To get used to dancing barefoot, Ho recommends dancers take the time to break down challenging steps, like turns and slides, moment by moment. Practicing movements slowly can help you figure out the places where your bare feet will stick or slip naturally. Instead of trying to work against the traction your feet feel on the floor, learn how you can work with it. “Once I learned to stay grounded while turning,” says Ho, “pirouettes without shoes came more naturally.”

Taylor 2 dancer Madelyn Ho had never danced shoeless until her first college modern class. “It was so weird not having anything on my feet,” she remembers. To get used to dancing barefoot, Ho recommends dancers take the time to break down challenging steps, like turns and slides, moment by moment. Practicing movements slowly can help you figure out the places where your bare feet will stick or slip naturally. Instead of trying to work against the traction your feet feel on the floor, learn how you can work with it. “Once I learned to stay grounded while turning,” says Ho, “pirouettes without shoes came more naturally.”

Toughening Up

When you’re just beginning to dance barefoot, it doesn’t only feel strange—it’s often painful, too. Blisters, floor burns and split skin are no fun. But don’t worry: You’ll begin to build protective calluses on the toes and balls of your feet quickly. According to Dr. Donald J. Rose, director of the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries, you can accelerate the process by soaking your feet in black tea, which helps prevent skin damage. “The tannic acid in black tea helps harden the skin,” he says.

“The tannic acid in black tea helps harden the skin,” he says.

If you do experience a particularly bad split or blister, proper care is important. (Studio floors are dirty.) “Clean raw and open wounds to keep them from getting infected,” Rose advises. “Cover them while you dance with elastic athletic tape, but make sure to remove it at night to allow the wounds to heal.” Your calluses need a little TLC, too. “Thick calluses are likely to split or tear from underlying skin layers,” Rose warns. “Use a pumice stone to gently exfoliate calluses if they grow too dense.”

Practice Makes Perfect

As with most elements of dance, regular practice is the only tried-and-true way to get comfortable dancing shoeless. Don’t be tempted to “save your feet” by rehearsing a barefoot piece in socks or shoes—even if your choreographer allows it. You’ll only set yourself up for more challenges when it’s finally time to perform. Instead, advises Ho, relax and enjoy the experience. “I actually feel better when I’m barefoot,” she says. “It makes my dancing so much freer.”

“I actually feel better when I’m barefoot,” she says. “It makes my dancing so much freer.”

Barefoot Dance: The Good the Bad and the Ugly | ATOMIC Ballroom

Skip to content Barefoot Dance: The Good the Bad and the UglyBehind the scenes in the world of dance an ongoing debate has been underway over the pro’s and cons of dancing without shoes.

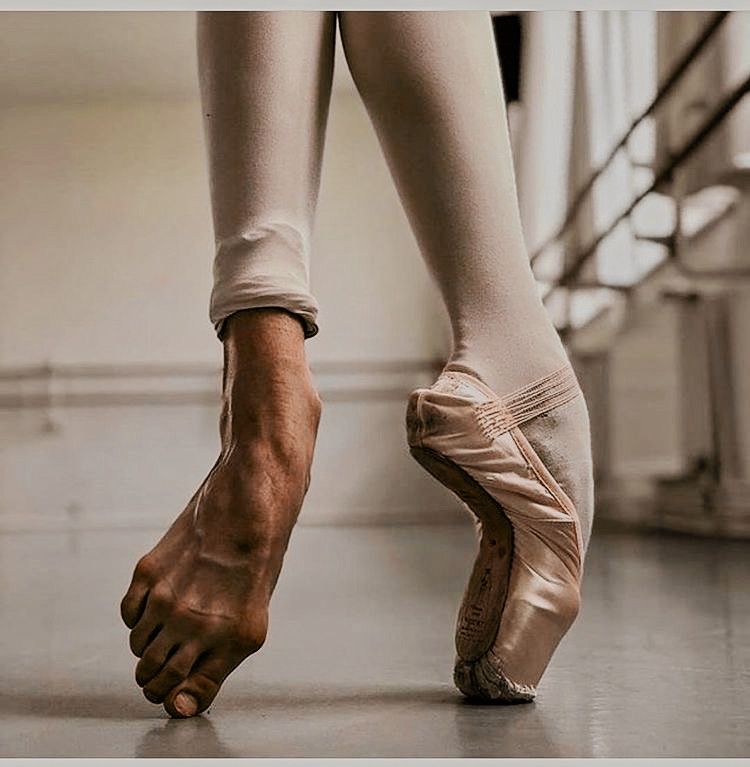

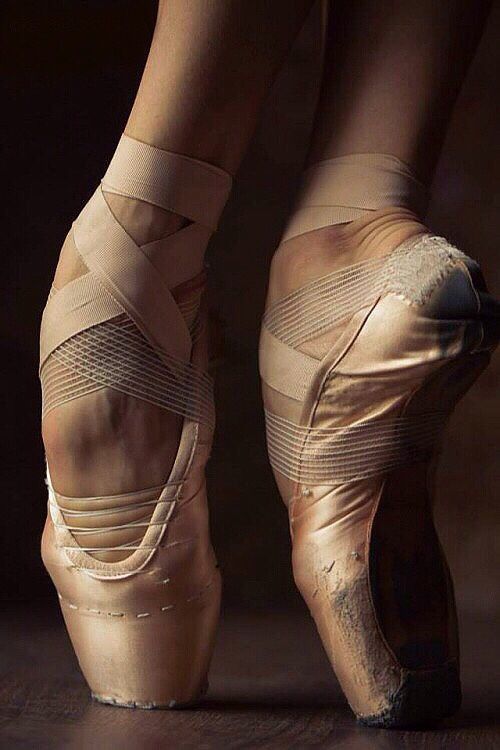

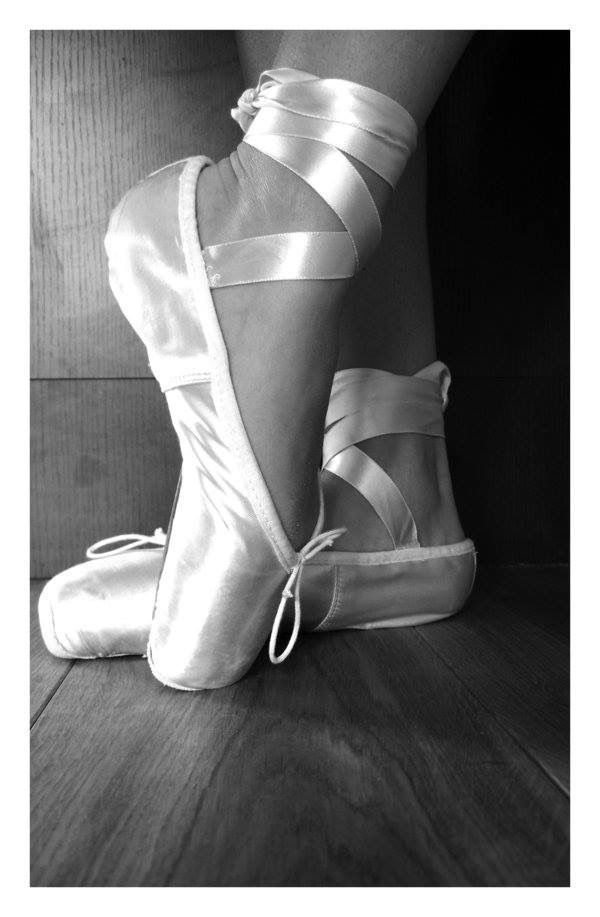

Some arguments against dancing without shoes are of course that it compromises safety and even claims that boogying barefoot increases the spread of fungal infections, passed around by unclean feet or conditions. Others report that they are more prone to blistered, bleeding, torn up feet without the protective barrier that footwear would provide. While other cases made are merely superficial, such as that of the ballet world which prides itself on uniformity of movement as well as appearance. From the neatly pulled back buns to matching monochromatic leotards, it is typically frowned upon to stand out or stray far from tradition, even down to the footwear. The irony is that it is no secret that ballet shoes (particularly pointe shoes) are known to severely blister and bruise feet. The easily broken down design is not made to last long, much less cushion the leaps and spins of the hardworking dancers. Despite these sometimes painful realities, there are others in the dance world who disagree.

From the neatly pulled back buns to matching monochromatic leotards, it is typically frowned upon to stand out or stray far from tradition, even down to the footwear. The irony is that it is no secret that ballet shoes (particularly pointe shoes) are known to severely blister and bruise feet. The easily broken down design is not made to last long, much less cushion the leaps and spins of the hardworking dancers. Despite these sometimes painful realities, there are others in the dance world who disagree.

For dance styles like contemporary, Senegalese and Afro-Brazilian, just to name a few, dancers perform barefoot in order to fully feel and connect with the ground beneath them. Proponents argue that this allows for greater precision of pointed feet, spins, and greater dexterity of movement overall. Some even go on to assert that the callouses dancers get from dancing barefoot are good on the contrary, and are essential for more precise movements.

Early founders of modern dance advocated dancing barefoot in part to further distinguish it from ballet, for which proper footwear and attire is mandatory. It was also believed to reflect core values like connection with ones body and a representation of earthly ideals. This was in spite of the fact that being barefoot was seen as defiant at a time and place when it was considered scandalous for a woman to bare her ankles let alone her naked feet. Dancing barefoot has since become the standard of modern and contemporary dance training, whether practicing in the studio or performing on stage.

It was also believed to reflect core values like connection with ones body and a representation of earthly ideals. This was in spite of the fact that being barefoot was seen as defiant at a time and place when it was considered scandalous for a woman to bare her ankles let alone her naked feet. Dancing barefoot has since become the standard of modern and contemporary dance training, whether practicing in the studio or performing on stage.

Maria Hanley Blakemore, an advocate for early childhood dance education and youth ballet instructor, strongly believes that dancers, especially children should not wear shoes at all. In fact, she insists that her students dance barefoot. One reason is that shoes often fall off or constantly need to be tied. Also, some students complain about their shoes being uncomfortable and want to remove them anyway. Once one dancer removes his or her shoes, the others tend to want to follow suit; which lends to the next problem of students mixing their shoes up with one another’s. So rather than waisting time and becoming a distraction in class, she encourages them to go with out shoes from the start, so that they can focus their attention on dancing rather than what they’re wearing. Blakemore and others argue that greater sensations can be felt while barefoot, allowing one to experience greater connection by imagining the feeling of things like mud or other objects between their toes.

So rather than waisting time and becoming a distraction in class, she encourages them to go with out shoes from the start, so that they can focus their attention on dancing rather than what they’re wearing. Blakemore and others argue that greater sensations can be felt while barefoot, allowing one to experience greater connection by imagining the feeling of things like mud or other objects between their toes.

Putting the above arguments to the side, one advantage of being barefoot that all sides could agree on is being able to show support for the charity Soles4Souls, which raises money to provide shoes for over 300 million underprivileged kids worldwide. The organization encourages supporters to join the movement simply by kicking their shoes off their feet while under their desk at work or running around barefoot in the grass. One way that I partake is by kicking off my shoes and socks before a long drive. I genuinely feel more attentive and connected while on the road just by feeling the contour of the pedals directly on my feet. Whether you kick off your shoes at work, on the dance floor or at the beach with the warm sand running between your toes, take a moment to truly feel the contours of the ground beneath you this Go Barefoot Day, June 1st. (Yes, this is a real nationally observed day!) You can let your feet breath and have a moment to unwind all while supporting a worthy cause.

Whether you kick off your shoes at work, on the dance floor or at the beach with the warm sand running between your toes, take a moment to truly feel the contours of the ground beneath you this Go Barefoot Day, June 1st. (Yes, this is a real nationally observed day!) You can let your feet breath and have a moment to unwind all while supporting a worthy cause.

About the Author: Nneka

Having fearlessly explored every continent, Nneka is multi-lingual and passionate about travel, culture and life. A SDSU alumni, she has worked in KTVU Fox's newsroom, interviewed notable figures and hosted programs for various media outlets. She has also written features for The San Leandro Times and LostGirlsWorld.com. Also a seasoned performer and fitness professional, Nneka holds several fitness certifications, has shared the stage with entertainment icons, and has appeared on various TV Shows. Follow her global adventures in the arts and beyond on IG @nnekaworldtrekker.

Follow her global adventures in the arts and beyond on IG @nnekaworldtrekker.

Toggle Sliding Bar Area

Pointe shoes: ballet, desire and power

Have you ever been on pointe shoes? Do not rush to answer "no". After all, the French expression "sur la pointe des pieds", from where pointe shoes originate, can mean a tiptoe stand, on "half-toes", and not just on the fingertips. Finger dancing in ballet shoes adapted for this purpose with a strongly reinforced toe, which are also called “pointe shoes,” is a relatively recent phenomenon, less than two hundred years old. Judging by the ancient images, the ancient Greeks stood on their toes without any special shoes, and simply without shoes. And in later times, writes Lyubov Dmitrievna Blok, who became a ballet historian in the middle of her life, “it was considered useful to start studying pointe shoes without a shoe: even P.A. Gerdt taught me to stand on my fingers in one tights" (Block 1987:36)[1].

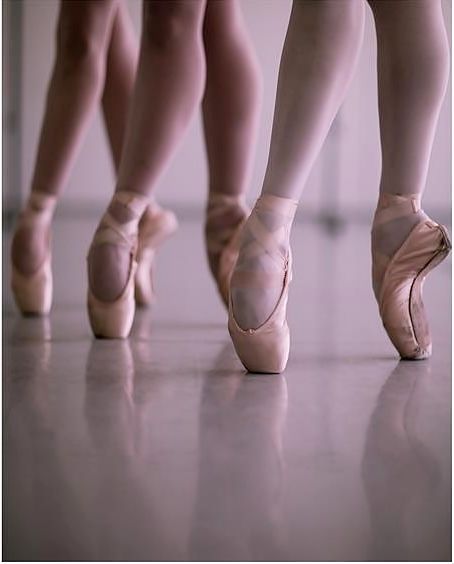

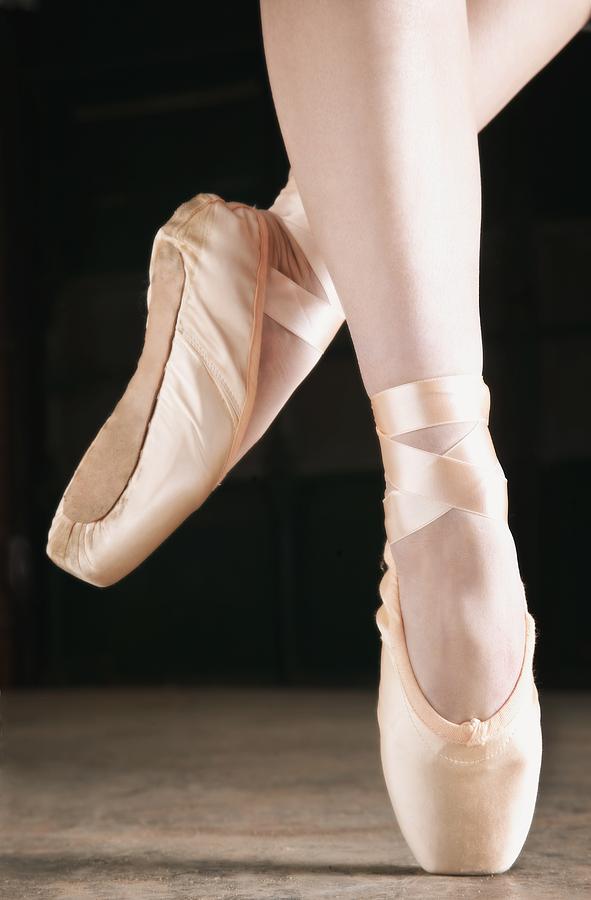

Nowadays, however, pointe shoes are primarily associated with shoes - modern ballet shoes with a hard square toe, as well as the dance technique in them. The sock slightly increases the area of support: the point - “pointe” - turns into, albeit quite small, but a platform, a “patch”, on which the ballerina must stay. The pointe shoes technique is also special: they are stepped on in one movement, whether it is relevé (lifting), sauté (jumping) or piqué (standing first on the tip of one shoe, then on the other). Pointe shoes require not only a "steel" toe, but also, according to Blok, "a firmly extended knee, a strongly forward arched instep, an effaced heel, and the straightness of the entire leg as a whole" (Ibid.). In ballet schools, pointe shoes are put on only after the girl's bones have hardened enough, the necessary muscles have formed, and the ability to maintain balance in posture and movement has developed - that is, not earlier than ten or eleven years.

Arguing about who was the first of the ballerinas to stand on her fingertips, two names are usually called: Genevieve Gosselin and Avdotya Istomina. This happened in Zephyr and Flora, which Charles-Louis Didelot staged in Paris in 1815 and brought to the Petersburg stage three years later (Crane & Mackrell 2000). However, Didlo had only one motionless pose on her fingers. This spectacular trick was turned into a dance technique by Maria Taglioni under the guidance of her father, Filippo Taglioni. She herself mentioned among her predecessors also Amalia Brugnoli, who, in her words, “did extraordinary things with her fingertips”, although she had to help herself with her hands (quoted in: Rambaud 2005: 190).

This happened in Zephyr and Flora, which Charles-Louis Didelot staged in Paris in 1815 and brought to the Petersburg stage three years later (Crane & Mackrell 2000). However, Didlo had only one motionless pose on her fingers. This spectacular trick was turned into a dance technique by Maria Taglioni under the guidance of her father, Filippo Taglioni. She herself mentioned among her predecessors also Amalia Brugnoli, who, in her words, “did extraordinary things with her fingertips”, although she had to help herself with her hands (quoted in: Rambaud 2005: 190).

Taglioni did not yet have special shoes with reinforced toes - she danced in satin ball shoes (in the era of the Directory they lost their heels and had a flat and flexible sole), the toe of which was only quilted. The ballerina Alicia Markova, who owned Taglioni shoes, compared them to "kid gloves" (Terry 1962: 60). It is impossible to stand on such pointe shoes for a long time or twist 32 fouettes, and the first pointe technique was radically different from the modern one. Dance historian Inna Sklyarevskaya believes that the first pointe shoes were not perceived separately from the body, but, as it were, continued its movements. Taglioni's movements were light, airy, "fluttering" and "swirling" (Sklyarevskaya, manuscript)[2]. Only the next generation of ballerinas, technical Italians like Pierina Legnani, had shoes with a tight glued toe made of leather or cork. In the modern ballet shoe with a hard toe (which is increasingly made of plastic), the foot has lost its flexibility and, in the words of Sklyarevskaya, has "only three positions: the first - when standing on the floor, the second - when the instep is extended, on the fingers or in the air, and the third is on the half-fingers. Departing from the stage, Taglioni contemptuously called the new shoes "orthopedic devices." “A ballerina who jumps hard on hard socks stuffed with cork and cotton, and who is firmly held by the gentleman, besides helping her to rotate,” writes Sklyarevskaya, “all this was outrageous clowning for Taglioni” (ibid.

Dance historian Inna Sklyarevskaya believes that the first pointe shoes were not perceived separately from the body, but, as it were, continued its movements. Taglioni's movements were light, airy, "fluttering" and "swirling" (Sklyarevskaya, manuscript)[2]. Only the next generation of ballerinas, technical Italians like Pierina Legnani, had shoes with a tight glued toe made of leather or cork. In the modern ballet shoe with a hard toe (which is increasingly made of plastic), the foot has lost its flexibility and, in the words of Sklyarevskaya, has "only three positions: the first - when standing on the floor, the second - when the instep is extended, on the fingers or in the air, and the third is on the half-fingers. Departing from the stage, Taglioni contemptuously called the new shoes "orthopedic devices." “A ballerina who jumps hard on hard socks stuffed with cork and cotton, and who is firmly held by the gentleman, besides helping her to rotate,” writes Sklyarevskaya, “all this was outrageous clowning for Taglioni” (ibid. ). The ephemeral nature of Taglioni's shoes corresponded to the airiness of her jumps, the grace of pirouettes and the romantic image of an unearthly, weightless creature that she diligently created in La Sylphide and Giselle. Giving away her ballet shoes to fans, Taglioni inscribed them in small, elegant handwriting on thin leather soles. Balletomaniacs turned her shoes into a fetish, and one St. Petersburg fan ordered the pair presented to him to be boiled - and ate it with a side dish![3]

). The ephemeral nature of Taglioni's shoes corresponded to the airiness of her jumps, the grace of pirouettes and the romantic image of an unearthly, weightless creature that she diligently created in La Sylphide and Giselle. Giving away her ballet shoes to fans, Taglioni inscribed them in small, elegant handwriting on thin leather soles. Balletomaniacs turned her shoes into a fetish, and one St. Petersburg fan ordered the pair presented to him to be boiled - and ate it with a side dish![3]

We will return to pointe shoes as a fetish (that is, an object endowed with special power) a little later, but for now let's see what gives the dancer and choreographer the rise to pointe shoes. Ballet dancers, aficionados and scholars of the art make various arguments for the need for pointe shoes. Firstly, dancing on the fingertips helps to create the impression of lightness, airiness, the illusion that gravity does not act on the dancers. Secondly, pointe shoes continue and bring to perfection the line so valued in ballet: “no matter how high you stand on your toes, the leg still forms a broken line,” notes L. D. Block. “To get the same straight line that we can have in the air, in a jump, we need to stand on our fingers” (Block 1987:19). Dancer and choreographer Mikhail Fokin valued dance on pointe for its "artificiality" or, in the words of the theater theorist Eugenio Barba, its "extra-ordinary", that is, going beyond the limits of everyday existence, to another level, which Barba calls "expressive" ( Barba, Savarese 2010: 42–46). Blok also considers the “unnaturalness” of pointe shoes to be more of a virtue than a disadvantage: “Yes, they are completely unnatural, quite the product of abstract thinking. But if we had remained in the realm of sound with the intervals “naturally” inherent in primitive man – the fourth, the fifth and the octave – we would not have gone far and modern music would not exist” (Block 1987:18–19). Both Fokine and Blok believe that art is “artificial.” Another opinion about the meaning of pointe shoes was expressed by the critic Akim Volynsky: “if the vertical position essentially reflects the face of a person, then standing on the fingers is its apotheosis” (Volynsky 2008: 25).

D. Block. “To get the same straight line that we can have in the air, in a jump, we need to stand on our fingers” (Block 1987:19). Dancer and choreographer Mikhail Fokin valued dance on pointe for its "artificiality" or, in the words of the theater theorist Eugenio Barba, its "extra-ordinary", that is, going beyond the limits of everyday existence, to another level, which Barba calls "expressive" ( Barba, Savarese 2010: 42–46). Blok also considers the “unnaturalness” of pointe shoes to be more of a virtue than a disadvantage: “Yes, they are completely unnatural, quite the product of abstract thinking. But if we had remained in the realm of sound with the intervals “naturally” inherent in primitive man – the fourth, the fifth and the octave – we would not have gone far and modern music would not exist” (Block 1987:18–19). Both Fokine and Blok believe that art is “artificial.” Another opinion about the meaning of pointe shoes was expressed by the critic Akim Volynsky: “if the vertical position essentially reflects the face of a person, then standing on the fingers is its apotheosis” (Volynsky 2008: 25). The physical essence of a person is in his upright, upright position and, therefore, rising on his fingers can be considered its most complete disclosure, the highest point - this is how the balletomane Volynsky made the ballerina the ideal of a person.

The physical essence of a person is in his upright, upright position and, therefore, rising on his fingers can be considered its most complete disclosure, the highest point - this is how the balletomane Volynsky made the ballerina the ideal of a person.

Even more interesting is the explanation offered by the famous dance theorist Susan Lee Foster (Foster 1995: 1–24). She makes a bold comparison of the ballerina's body with the phallus. An archaic symbol of power, the phallus has always been depicted as straight and solid, like a royal rod (the penis is a very imperfect phallus!). Like the phallus, the ballerina's body - strong, hard, resilient - is straightened vertically. Pointe shoes enhance the resemblance of the ballet body to the phallus, and hence its symbolic power. The leg, wrapped in a pale pink leotard, ends in a satin ballerina of the same color as the rounded pommel of the phallus. Its sock is in a special way, inhumanly hard (today it is made of inorganic materials). Absolutely extended at the knee and ankle, the leg is in a perfectly straight line. Trained muscles and increased mobility of the hip joint allow the leg to move as if separately from the body, to rise high in grand batmans and arabesques and linger in the air - even more reminiscent of an erect phallus. There are legends about the strength of ballet legs: long before the advent of karate, a joke was told that a ballerina (this was also said about Taglioni) could kill a horse with a kick. So, "phallic pointe shoes", according to Foster, a symbol in which male desire and its female object are combined; the ballerina personifies both the desire itself and the instrument of its satisfaction.

Absolutely extended at the knee and ankle, the leg is in a perfectly straight line. Trained muscles and increased mobility of the hip joint allow the leg to move as if separately from the body, to rise high in grand batmans and arabesques and linger in the air - even more reminiscent of an erect phallus. There are legends about the strength of ballet legs: long before the advent of karate, a joke was told that a ballerina (this was also said about Taglioni) could kill a horse with a kick. So, "phallic pointe shoes", according to Foster, a symbol in which male desire and its female object are combined; the ballerina personifies both the desire itself and the instrument of its satisfaction.

The comparison of the ballerina to the phallus can be disputed, but its productivity cannot be denied - it makes us think about the relationship of ballet to issues of gender and power. So, thanks to him, I understood why one of my girlfriends, as an adult, wanted to study ballet, and, of course, on pointe shoes. Pointe shoes themselves have become the subject of her vigilant concern - she writes out the most technically advanced pointe shoes from abroad at an expensive price, she worries about having a constant supply - because they wear out quickly. Apparently, she, a woman already quite strong and strong-willed, is guided not only by the desire for grace and glamour, but also by the discovery of additional sources of strength and power for herself. Pointe shoes are an affordable way for women to convert their skills and appearance into social capital, to gain a reputation in their circle. Let us recall the trepidation with which a ballet school student picks up and then puts on her first pointe shoes. She feels that ballet shoes with a hard toe give her the right to virtuosity, the right to be special, not like everyone else. Pointe shoes literally elevate her above others, including men, make her a “superworldly” being. But also one that draws attention and arouses desire, because in today's narcissistic culture, girls learn very early how to please.

Pointe shoes themselves have become the subject of her vigilant concern - she writes out the most technically advanced pointe shoes from abroad at an expensive price, she worries about having a constant supply - because they wear out quickly. Apparently, she, a woman already quite strong and strong-willed, is guided not only by the desire for grace and glamour, but also by the discovery of additional sources of strength and power for herself. Pointe shoes are an affordable way for women to convert their skills and appearance into social capital, to gain a reputation in their circle. Let us recall the trepidation with which a ballet school student picks up and then puts on her first pointe shoes. She feels that ballet shoes with a hard toe give her the right to virtuosity, the right to be special, not like everyone else. Pointe shoes literally elevate her above others, including men, make her a “superworldly” being. But also one that draws attention and arouses desire, because in today's narcissistic culture, girls learn very early how to please.

Traditionally, women dance on pointe shoes: in the romantic ballet (created by Taglioni and her contemporaries in the 1830s), they are assigned the role of being graceful, airy and flexible, while men are given the role of a strong, heroic, but auxiliary - to serve as a support for the dancer. Serge Lifar regretted that “female elevation temporarily defeated male elevation, and not only won, but also pushed the dancer — for the entire 19th century — into the background” (Lifar 2014: 113). Akim Volynsky, on the contrary, was satisfied with such a gender distribution of roles. Reproducing a gender stereotype, he compared the dancer with a plant, flower, grass swaying in the wind, and the dancer with a bird: he “will fly up from his place, in a bold jump, and show his active heroism in the air with a whole series of figures, partly inaccessible to a woman. He doesn't need fingers. He has wings” (Volynsky 2008: 28–29). Now the distribution of roles has changed: modern ballerinas are no less athletic and just as technical as men, and the appearance of a dancer, on the contrary, can be androgynous or feminized. In some troupes - the Trocadero Ballet from Monte Carlo, the St. Petersburg Men's Ballet - men dance on pointe shoes. In the romantic ballet of the 19th century, male roles were often performed by female drag queens; in the same troupes, male drag queens perform female roles. Spectators in such productions are attracted by a combination of remarkable strength, homoeroticism, carnival grotesque and humor.

In some troupes - the Trocadero Ballet from Monte Carlo, the St. Petersburg Men's Ballet - men dance on pointe shoes. In the romantic ballet of the 19th century, male roles were often performed by female drag queens; in the same troupes, male drag queens perform female roles. Spectators in such productions are attracted by a combination of remarkable strength, homoeroticism, carnival grotesque and humor.

If pointe shoes are an essential feature of ballet, then the free dance program is a bare foot. It is no coincidence that Isadora Duncan's manifesto The Dance of the Future (1903) opened with a hymn to the bare foot. In her youth, Isadora was engaged, among other things, in the classical machine, but later she found her own style and refused to dance en pointe. It sounded like a declaration: in doing so, she abandoned the traditional gender role for the ballet scene. Her dancer was not an elf, but remained a woman, earthly and full-blooded. The “new” dancer, or, more precisely, the “new” dancing woman, could and did evoke the desire of men, but did not turn into an object, retained her own desires and feelings. To continue Susan Foster's analogy between pointe shoes and phallic power, barefoot is a resolute rejection of such power on stage and in life. Free dance was born from the desire of dancers to move and enjoy movement, from the desire to be themselves, to create and improvise, to express their own feelings, to dance their own dance. The bare foot of the dancer did not symbolize the phallus, but something completely different. Duncan once had a dispute about this:

To continue Susan Foster's analogy between pointe shoes and phallic power, barefoot is a resolute rejection of such power on stage and in life. Free dance was born from the desire of dancers to move and enjoy movement, from the desire to be themselves, to create and improvise, to express their own feelings, to dance their own dance. The bare foot of the dancer did not symbolize the phallus, but something completely different. Duncan once had a dispute about this:

“Once a lady asked me why I dance barefoot, I answered her:“ This is because I feel reverence for the beauty of the human foot. The lady noticed that she had not experienced this feeling. I said, "But, ma'am, it is necessary to feel it, because the shape and plasticity of the human foot is a great victory in the history of human development." “I don’t believe in the development of man,” objected the lady. “I am silent,” I said, “all I can do is refer you to my venerable teachers Charles Darwin and Ernst Haeckel” (Snezhko 1990:17).

Instead of symbolically satisfying male desire, the dancer's feet now served to celebrate human evolution and progress! The pale pink leotard turns the dancer's slender leg into the leg of a marble statue, into an object, a work of art. Duncan took off not only pointe shoes, but also tights. Having discovered their insecurity and imperfection, the dancer's legs became a symbol of naturalness, closeness to nature, the harmony of man with the cosmos. Duncan vehemently criticized ballet for its artificiality and teased balletomanes that they "can't see beyond a ballet skirt and leotards." “If,” she wrote, “their gaze could penetrate deeper, they would see that unnaturally disfigured muscles move under skirts and tights; and if we look even deeper, we will see the same disfigured bones under the muscles: an ugly body and a twisted skeleton dances before us! (ibid: 19). So, instead of sylphs - dance of death. Calling to look deeper, through tights and even the skin of a ballerina, Duncan made us think: “what kind of ideals does ballet express?”. The shrewd Isadora knew that dance, like everything in the world, is a political matter and serves the interests of certain groups, and most often - money and those in power. She also knew that a tutu, leotards and pointe shoes not only open, expose the body of a dancer, but also hide the flesh, turning a woman into a glamorous doll, a toy of other people's desires. Leotards and satin pointe shoes give the dancer shine, sex appeal, glamour, but nudity, Duncan argued, is more beautiful and more moral than glamour (ibid.: 21).

The shrewd Isadora knew that dance, like everything in the world, is a political matter and serves the interests of certain groups, and most often - money and those in power. She also knew that a tutu, leotards and pointe shoes not only open, expose the body of a dancer, but also hide the flesh, turning a woman into a glamorous doll, a toy of other people's desires. Leotards and satin pointe shoes give the dancer shine, sex appeal, glamour, but nudity, Duncan argued, is more beautiful and more moral than glamour (ibid.: 21).

Modern dance has not only listened to this sermon, but has also learned to extract a lot of useful things from barefoot. In contrast to aristocratic ballet, dancing with bare feet or in sports shoes (Sally Baines' book on postmodern dance is called Terpsichore in Sneakers (Banes 1987)) positions itself as a democratic art - although, due to its technical complexity, it can be practiced far Not all. The refusal to put on ballet shoes, straighten your knees and pull your toes is synonymous with the protest spirit of modern dance, as well as modern art in general. Today, the preference is given to a body that is relaxed or slightly relaxed, "alive" and responsive, which obeys its own will, and not someone else's discipline. Modern choreographers, both in ballet (which is now also often danced barefoot or in soft shoes) and in modern dance, can use the opposition of pointe shoes to the bare foot as a means of expression. So, in John Neumeier's ballet The Little Mermaid (2005), the prince's girlfriends from high society are ideal, on pointe shoes, and the Little Mermaid - crooked, barefoot and in a wheelchair - is "natural", but also not free in her nature because of the desire to be on pointe shoes. them similar. And in the work of the Canadian choreographer Marie Chouinard “bODY_rEMIX/gOLDBERG_vARIATIONS” (2005), dance on pointe shoes is adjacent to dance on prostheses and crutches, and the viewer sees, as Taglioni once did, that both are “orthopedic devices”.

Today, the preference is given to a body that is relaxed or slightly relaxed, "alive" and responsive, which obeys its own will, and not someone else's discipline. Modern choreographers, both in ballet (which is now also often danced barefoot or in soft shoes) and in modern dance, can use the opposition of pointe shoes to the bare foot as a means of expression. So, in John Neumeier's ballet The Little Mermaid (2005), the prince's girlfriends from high society are ideal, on pointe shoes, and the Little Mermaid - crooked, barefoot and in a wheelchair - is "natural", but also not free in her nature because of the desire to be on pointe shoes. them similar. And in the work of the Canadian choreographer Marie Chouinard “bODY_rEMIX/gOLDBERG_vARIATIONS” (2005), dance on pointe shoes is adjacent to dance on prostheses and crutches, and the viewer sees, as Taglioni once did, that both are “orthopedic devices”.

Another suggestive juxtaposition is pointe shoes with a corset. Dance theorist Philippe Verrielle is even more categorical: “the fetishistic function of the tutu and pointe shoes cannot be understood without comparing them with a corset” (Verrièle 2006: 198). Most likely, because the mechanisms of biopower and desire - in this case, the transformation of a part of the costume into a fetish - are best studied in relation to the corset. The ballet is aristocratic, it originated at the royal court, where ladies could only appear in corsets. Compressing the camp and maintaining the bearing, the corset limits the movement of the diaphragm and prevents breathing. And yet, even a hundred years ago, ballerinas wore a corset under their stage costume - partly following the tradition, for reasons of decency, but also to maintain the vertical of the body. Both pointe shoes and a corset combine a support function with a restrictive, repressive function, strength with discipline and pain, and this, in particular, is the basis of the operation of turning them into a fetish (see: Steele 2010).

Most likely, because the mechanisms of biopower and desire - in this case, the transformation of a part of the costume into a fetish - are best studied in relation to the corset. The ballet is aristocratic, it originated at the royal court, where ladies could only appear in corsets. Compressing the camp and maintaining the bearing, the corset limits the movement of the diaphragm and prevents breathing. And yet, even a hundred years ago, ballerinas wore a corset under their stage costume - partly following the tradition, for reasons of decency, but also to maintain the vertical of the body. Both pointe shoes and a corset combine a support function with a restrictive, repressive function, strength with discipline and pain, and this, in particular, is the basis of the operation of turning them into a fetish (see: Steele 2010).

In her desire to become closer to nature, Duncan rejected both pointe shoes, and a corset, and leotards, and a bra (for which, of course, her Puritan compatriots, Americans, criticized her). The most radical of the women of her generation, she went to the end in everything, including denying any need for marriage in order to live with a man and give birth to children. Nevertheless, even such an ideological opponent of ballet as Duncan, once at the Mariinsky Theater, could not help but applaud the Russian ballerinas when they fluttered around the stage, more like birds than human beings" (Snezhko 1990:112). Russian classical ballet knew how to charm, and pointe shoes were part of that magic. But magic had to be carefully prepared. Anna Pavlova, whom Duncan admired, brought her pointe shoes to perfection in a way known only to her. First, she let them “break” one of the dancers of her troupe (we are talking about the time after Pavlova’s departure from Russia), then she ripped off the sacking sewn from the inside, pulled out the cardboard and replaced it with some other material (perhaps it was durable leather that gave hardness sock). Pavlova complained that her toes were too long and her instep was too high and arched.

The most radical of the women of her generation, she went to the end in everything, including denying any need for marriage in order to live with a man and give birth to children. Nevertheless, even such an ideological opponent of ballet as Duncan, once at the Mariinsky Theater, could not help but applaud the Russian ballerinas when they fluttered around the stage, more like birds than human beings" (Snezhko 1990:112). Russian classical ballet knew how to charm, and pointe shoes were part of that magic. But magic had to be carefully prepared. Anna Pavlova, whom Duncan admired, brought her pointe shoes to perfection in a way known only to her. First, she let them “break” one of the dancers of her troupe (we are talking about the time after Pavlova’s departure from Russia), then she ripped off the sacking sewn from the inside, pulled out the cardboard and replaced it with some other material (perhaps it was durable leather that gave hardness sock). Pavlova complained that her toes were too long and her instep was too high and arched. The dancer Vera Karalli recalled that she told her: “Oh, if only I had your legs!” , and Pavlova has a very thin ankle with a huge rise, which ... interfered with her in dancing ”(quoted from: Gamula 2009: 137–154 (147)). To maintain balance, Pavlova needed a little more support than standard pointe shoes would allow. Nevertheless, in her photographs, it seems that the toe of her pointe shoes, on the contrary, is smaller and the ballerina is literally balancing on one point. The explanation for this is simple – in the photo, the toe of the pointe shoes is painted over and retouched (Hill 2013: 143–166 (147)).

The dancer Vera Karalli recalled that she told her: “Oh, if only I had your legs!” , and Pavlova has a very thin ankle with a huge rise, which ... interfered with her in dancing ”(quoted from: Gamula 2009: 137–154 (147)). To maintain balance, Pavlova needed a little more support than standard pointe shoes would allow. Nevertheless, in her photographs, it seems that the toe of her pointe shoes, on the contrary, is smaller and the ballerina is literally balancing on one point. The explanation for this is simple – in the photo, the toe of the pointe shoes is painted over and retouched (Hill 2013: 143–166 (147)).

Metaphorically speaking, Anna Pavlova's hand was as light as her leg. It is known about her friendly professional communication with a shoemaker from New York, Salvatore Capezio, who sewed shoes for actors and dancers. Pavlova's name helped establish his firm's reputation, and the Capezio brand still produces pointe shoes with the Pavlova name. A line of pointe shoes, called "Duro Toe" ("Hard fingers"), was created by Capezio in 1930 year; for greater durability, a piece of suede was placed in the toe of ballet shoes.

A ballerina should not only wear pointe shoes with a hard toe, like ordinary shoes, so that they sit on her leg, but also “break”, soften the toe for herself. They say that Galina Ulanova, wherever she danced, did not part with the hammer, with which she broke the socks of pointe shoes. Piglet of pointe shoes is lined with a piece of fabric or sheathed with threads so as not to shaggy; new skin is scratched or rubbed with rosin so that it does not slip. Inside the shoe, from the side of the heel, a constriction loop is made (it presses the shoes to the leg so that the edges do not puff out) and, finally, ribbon ribbons are sewn on. And all the same, pointe shoes rub calluses and cause deformation of the foot and ankle, in the worst case, they lead ballet dancers to professional diseases.

Anatomically and biomechanically, pointe dancing can be compared to high heeled walking (see: Laws 2008: 25). When walking in high heels, as well as when climbing pointe shoes, the position of the body changes: the pelvis moves back, the chest protrudes forward, the deflection at the waist increases, and as a result, the silhouette of the dancer seems more erotic. It is no coincidence that both types of shoes are fetishized. As cultural theorist Frenchie Lanning writes, high heels are associated with restraint, loss of balance, and therefore breathtaking danger (Lunning 2013: 102). Dance shoes are easily turned into a fetish also because dance is traditionally associated with erotica and sexuality. Let us remember Cinderella's glass slipper or Andersen's cruel fairy tale about red shoes, putting on which, the girl allegedly succumbs to the elements of dance and sin and dies. The enfant terrible of high shoe fashion, Christian Louboutin, combined two fetishes - pointe shoes and stiletto heels - in one pair of shoes ("Fetish Ballet" - "Fetish Ballerine Shoe", 2007). Francesco Russo created for Sergio Rossi "The Art of Fetishism" (Art of Fetishism, 2013) - also a fusion of stiletto and pointe shoes. Explaining the idea of "Fetish Ballet Shoes", Louboutin asks: "Isn't ballet pointe shoes the highest expression of a heel? The heel that raises the dancer to heaven, raises her above all other women? (cited in Hill 2013: 162).

It is no coincidence that both types of shoes are fetishized. As cultural theorist Frenchie Lanning writes, high heels are associated with restraint, loss of balance, and therefore breathtaking danger (Lunning 2013: 102). Dance shoes are easily turned into a fetish also because dance is traditionally associated with erotica and sexuality. Let us remember Cinderella's glass slipper or Andersen's cruel fairy tale about red shoes, putting on which, the girl allegedly succumbs to the elements of dance and sin and dies. The enfant terrible of high shoe fashion, Christian Louboutin, combined two fetishes - pointe shoes and stiletto heels - in one pair of shoes ("Fetish Ballet" - "Fetish Ballerine Shoe", 2007). Francesco Russo created for Sergio Rossi "The Art of Fetishism" (Art of Fetishism, 2013) - also a fusion of stiletto and pointe shoes. Explaining the idea of "Fetish Ballet Shoes", Louboutin asks: "Isn't ballet pointe shoes the highest expression of a heel? The heel that raises the dancer to heaven, raises her above all other women? (cited in Hill 2013: 162). This statement of a modern male fashion designer perfectly illustrates, on the one hand, the hymn to “fingers” that Akim Volynsky once sang in the “Book of Jubilations”, and on the other hand, the idea of modern theorists about pointe shoes as a “phallic” symbol of power.

This statement of a modern male fashion designer perfectly illustrates, on the one hand, the hymn to “fingers” that Akim Volynsky once sang in the “Book of Jubilations”, and on the other hand, the idea of modern theorists about pointe shoes as a “phallic” symbol of power.

Literature

[Barba, Savarese 2010] - Barba E., Savarese N. Dictionary of theatrical anthropology. The secret art of the performer M.: Artist. Producer. Theatre, 2010 (Barba Je., Savareze N. Slovar' teatral'noj antropologii. Tajnoe iskusstvo ispolnitelja M.: Artist. Director. Teatr, 2010).

[Block 1987] - Block L. Classical dance. History and modernity. Moscow: Art, 1987

(Blok L. Klassicheskij tanec. Istorija i sovremennost'. M.: Iskusstvo, 1987).

[Volynsky 2008] - Volynsky A. Book of jubilations. The ABC of Classical Dance (1925). St. Petersburg: Lan, 2008

(Volynskij A. Kniga likovanij. Azbuka klassicheskogo tanca (1925). SPb.: Lan', 2008).

Kniga likovanij. Azbuka klassicheskogo tanca (1925). SPb.: Lan', 2008).

[Gamula 2009] - Gamula I. Vera Karalli. Life through the prism of time (According to the materials of the funds of the State Central Theater Museum named after A.A. Bakhrushin) // Pages of the History of Ballet. New research and materials / Ed. N.L. Dunaeva. SPb., 2009

(Gamula I. Vera Karalli. Zhizn' skvoz' prizmu vremeni (Po materialam fondov GCTM im. A.A. Bahrushina) // Stranicy istorii baleta. Novye issledovanija i materialy / Pod red. N.L. Dunaevoj. SPb., 2009).

[Lifar 2014] - Lifar S. Dance. The main currents of academic dance. M.: GITIS, 2014

(Lifar' S. Tanec. Osnovnye techenija akademicheskogo tanca. M.: GITIS, 2014).

[Sklyarevskaya; manuscript] - Sklyarevskaya I. Taglioni, father and daughter. Genesis of a new style. Preparing for printing. Moscow: New Literary Review

(Skljarevskaja I. Tal'oni, otec i doch'. Genezis novogo stilja. Gotovitsja k pechati. M.: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie).

Tal'oni, otec i doch'. Genezis novogo stilja. Gotovitsja k pechati. M.: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie).

[Snezhko 1990] - Isadora Duncan / Ed. S.P. Snezhko. Kyiv, 1990

(Ajsedora Dunkan / Red.-sost. S.P. Snezhko. Kiev, 1990).

[Steel 2010] - Steel W. Corset. Moscow: New Literary Review, 2010

(Stil V. Korset. M.: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2010).

[Banes 1987] - Banes S. Terpsichore in Sneakers. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1987.

[Crane & Macrell 2000] - Pointe // Oxford Dictionary of Dance. Crane D., Mackrell J. (tds). 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2000.

[Foster 1995] - Foster S. The Ballerina's Phallic Pointe // Corporealities: Dancing Knowledge, Culture, and Power / Ed. Foster S.L. London: Routledge, 1995.

[Hill 2013] - Hill C. Ballet Shoes: Function, Fashion, Fetish // Dance & Fashion / Ed. by Valerie Steele. N.Y.: Yale University Press, 2013.

by Valerie Steele. N.Y.: Yale University Press, 2013.

[Laws 2008] - Laws K., with Sugano A. Physics and the Art of Dance: Understanding Movement. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2008.

[Lunning 2013] - Lunning F. Fetish Style. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

[Rambaud 2005] - Rambaud C. The Lure of Perfection: Fashion and Ballet, 1780-1830. N.Y.: Routledge, 2005.

[Terry 1962] - Terry W. On Pointe! The Story of Dancing and Dancers. N.Y.: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1962.

[Verrièle 2006] - Verrièle P. La Muse de mavaise réputation: danse et érotisme. Paris: La Musardine, 2006.

Notes

[1] P.A. Gerdt taught at the Imperial Choreographic School in St. Petersburg. (Hereinafter - approx. Aut. )

[2] I thank Inna Robertovna Sklyarevskaya for the opportunity to read this chapter in manuscript.

[3] As follows from the signature under the exhibit - Maria Taglioni's shoes - in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O64103/shoe .

5 famous brands of pointe shoes | IngoDance

August 24, 2021

Compilation

There are many more modern manufacturers of ballet shoes, but it is these brands that have the individuality and history behind which stands a real master.

Flexible and customized: BLOCH pointe shoes

An Australian manufacturer has been making pointe shoes since the early 1930s. At the same time, she sews dance clothes and shoes that can be worn at least every day - for example, ballet flats. The name of the company refers to the founder - Jacob Bloch, a native of Lithuania, who settled in Australia and sewed ballet shoes by hand. The master turned out to be talented and very able-bodied: it is known that at 19In the 1950s, Bloch himself created up to 50 pairs of pointe shoes a week. The demand for his creations went beyond Australia.

The demand for his creations went beyond Australia.

Bloch's pointe shoes have always been chosen for their exceptional flexibility. It was achieved thanks to the special technology turnshoe: the master sewed the upper to the sole, and then turned it inside out. It turned out a kind of shoe inside out - flexible and comfortable.

About 10 years ago, the manufacturing company improved the technology: thermal paste was used in the production of pointe shoes. To "plant" such shoes on the leg, it is enough to warm up the pointe shoes with a hairdryer. Under the influence of temperature, flexible thermal paste adjusts the glass - a rigid sock that fixes the thumbs - to the shape of the ballerina's foot. Thanks to this, the shoes do not need to be kneaded.

Ballerinas of the Bolshoi Theater mostly use BLOCH pointe shoes. The same shoes are worn by dancers from the Australian Ballet and other companies around the world.

The brand's bestseller is Serenade pointe shoes, which are incredibly flexible and do not require "fitting".

Top-selling: Pointe shoes Capezio

The brand was founded by the Italian shoemaker Salvatore Capezio. He created his brainchild in 1880. A feature of this shoe was an individual approach. Capezio made a wooden block, taking into account the physiological characteristics of the foot of the dancer for whom he created shoes. This approach, together with the development of a flatter and more stable nickel, made the Italian master's pointe shoes in demand among many ballet stars. For example, Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova and American dancer Eleanor Powell appeared on stage wearing Capezio shoes. Today, the manufacturer also offers dance clothes and bright accessories for the stage.

The bestseller of the brand is Capezio Gliss pointe shoes, which appeared in 2003 and became the best-selling ballet pair in history. They feature a streamlined outsole, a slightly angled heel counter, a stable platform and elastic laces. The rosé-flesh tone and satin exterior are the visual cues that make these shoes recognizable around the world.

Pointe shoes for every taste and color: Freed of London

Another manufacturer from the 1930s: Englishman Frederick Fried founded a shoe company named after himself in London. Together with his milliner wife, they occupied the basement of Covent Garden, and before that they worked for another pointe shoe manufacturer, Gamba. From 19For 37 years, production has been expanding and changing several workshops. Over the decades, the company has managed to hone the pad production technology to virtually perfection. Soon, Freed of London expands its footwear business and begins to produce clothing. Chacott, a manufacturer of Chacott pointe pointe shoes, appears as a separate branch. Unlike Freed of London, this shoe has a shorter drying time.

Today, Freed of London supplies pointe shoes to ballet companies around the world. And in 2018, the manufacturer, together with the organization Ballet Black, released a noticeable and sensational collection - pointe shoes in nude shades, including brown and bronze. The shoes are designed for black and Asian ballet dancers so that they can easily match their pointe shoes to their skin color. The creations of the London manufacturer are often chosen by artists of the Royal Theater and New York City Ballet, the Paris Grand Opera and the Dutch National Ballet.

The shoes are designed for black and Asian ballet dancers so that they can easily match their pointe shoes to their skin color. The creations of the London manufacturer are often chosen by artists of the Royal Theater and New York City Ballet, the Paris Grand Opera and the Dutch National Ballet.

The brand's bestseller is the classic Freed Pointe pointe shoes, well known to ballet professionals. Shoes are traditionally made by hand and decorated with signature peach-colored satin.

Repetto Pointe Shoes, Invented by a Loving Mother

Repetto, a French ballet shoe company, owes its name and concept to Rosa Repetto. Her son studied ballet, and she personally created shoes in which he would be comfortable dancing. For this first model, Rosa used the "cousu retourné" technique - in other words, she sewed the insole inside out to improve the cushioning for the feet. The first clients of the Repetto studio were the artists of the Parisian "Opera Garnier".

In the 1960s, the Repetto factory produced not only pointe shoes, but also ballet flats, in which Brigitte Bardot herself starred. Today, the ballet shoes of the French company are chosen by both corps de ballet dancers and prima ballerinas of world theaters.

The brand's bestseller is Gamba pointe shoes. There are eight models in this line, one of which was designed specifically for American Ballet dancers.

Plastic and durable: Gaynor Minden pointe shoes

Compared to previous manufacturers, the American brand Gaynor Minden is new to the market. The company has been making ballet shoes since 1993: This is when designer Eliza Minden developed her pointe shoes. She wanted to create durable and affordable shoes. She approached the task like a real researcher: she opened more than one pair from leading manufacturers in order to thoroughly study what was inside. As a result, she patented her invention.

Insole and cup combined into a one-piece construction made of elastomers.