How much does a dance therapist make

What is A Dance Therapist?

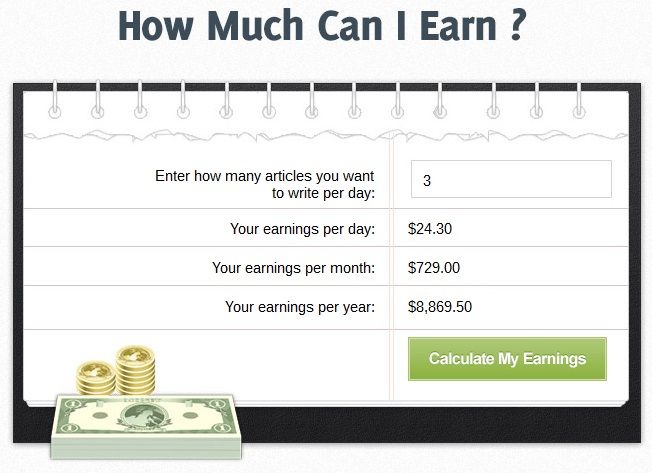

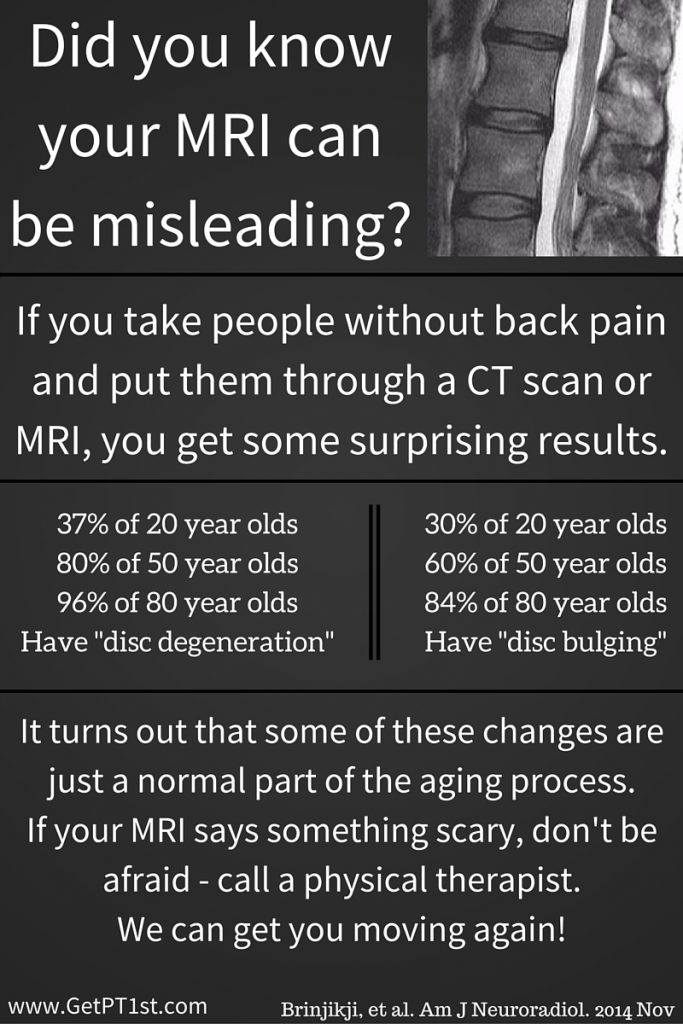

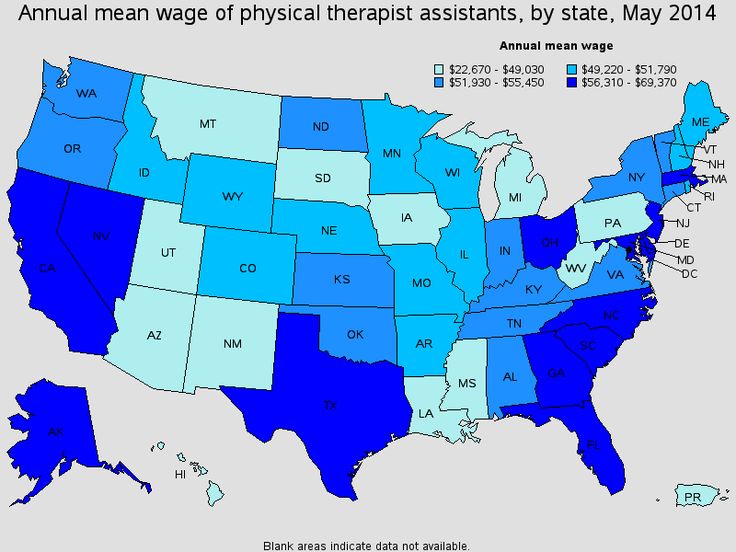

The average dance therapist salary is $51,634. The most common degree is a bachelor's degree degree with an rehabilitation science major. It usually takes 3-6 months of experience to become a dance therapist. Dance therapists with a Board Certified Dance/Movement Therapist (BC-DMT) certification earn more money. Between 2018 and 2028, the career is expected to grow 7% and produce 1,400 job opportunities across the U.S.

What Does a Dance Therapist Do

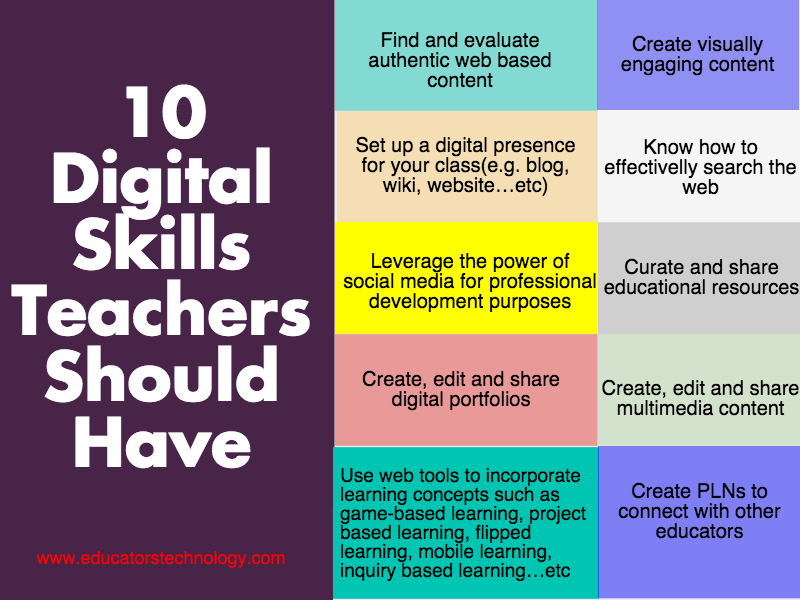

There are certain skills that many dance therapists have in order to accomplish their responsibilities. By taking a look through resumes, we were able to narrow down the most common skills for a person in this position. We discovered that a lot of resumes listed leadership skills, listening skills and speaking skills.

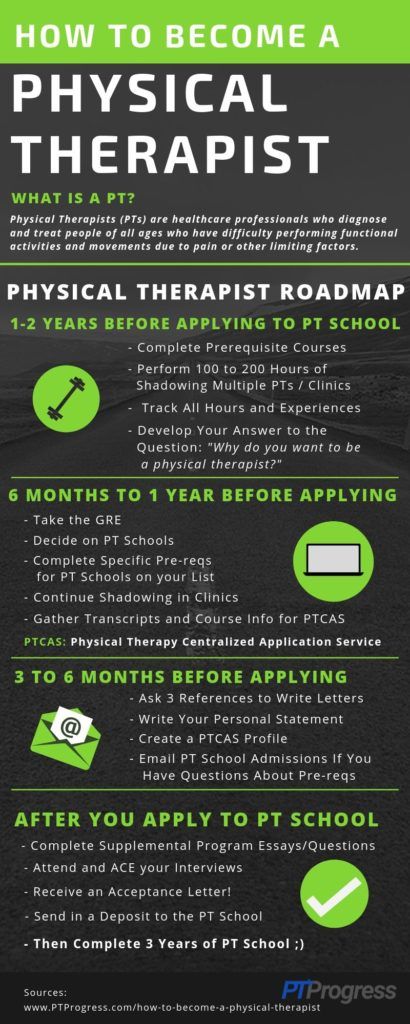

How To Become a Dance Therapist

If you're interested in becoming a dance therapist, one of the first things to consider is how much education you need. We've determined that 69. 6% of dance therapists have a bachelor's degree. In terms of higher education levels, we found that 26.1% of dance therapists have master's degrees. Even though most dance therapists have a college degree, it's impossible to become one with only a high school degree or GED.

Top Dance Therapist Jobs Near You

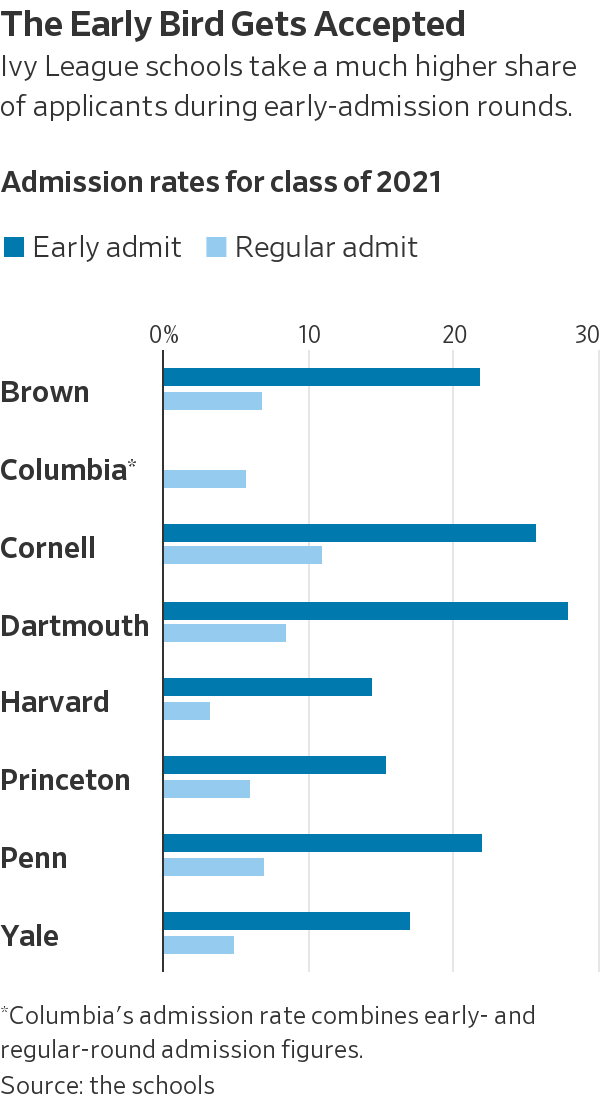

Dance Therapists in America make an average salary of $51,634 per year or $25 per hour. The top 10 percent makes over $74,000 per year, while the bottom 10 percent under $35,000 per year.

Average Dance Therapist Salary

$51,634 Yearly

$24.82 hourly

$35,000

10 %

$51,000

Median

$74,000

90 %

What Am I Worth?

Dance Therapist Education

Dance Therapist Majors

Rehabilitation Science

30.8 %

Psychology

15.4 %

Human Development

Dance Therapist Degrees

Bachelors

69.6 %

Masters

26.1 %

Diploma

Top Colleges for Dance Therapists

1.

Columbia University in the City of New York

Columbia University in the City of New YorkNew York, NY • Private

In-State Tuition

$59,430

Enrollment

8,216

2. California State University - Long Beach

Long Beach, CA • Private

In-State Tuition

$6,798

Enrollment

31,503

3. Hunter College of the City University of New York

New York, NY • Private

In-State Tuition

$7,182

Enrollment

16,205

4. University of Washington

Seattle, WA • Private

In-State Tuition

$11,207

Enrollment

30,905

5. New York University

New York, NY • Private

In-State Tuition

$51,828

Enrollment

26,339

6. Northwestern University

Evanston, IL • Private

In-State Tuition

$54,568

Enrollment

8,451

7. University of South Florida

Tampa, FL • Private

In-State Tuition

$6,410

Enrollment

31,321

8. Howard University

Washington, DC • Private

In-State Tuition

$26,756

Enrollment

6,166

9.

San Jose State University

San Jose State UniversitySan Jose, CA • Private

In-State Tuition

$7,796

Enrollment

27,125

10. Duke University

Durham, NC • Private

In-State Tuition

$55,695

Enrollment

6,596

The skills section on your resume can be almost as important as the experience section, so you want it to be an accurate portrayal of what you can do. Luckily, we've found all of the skills you'll need so even if you don't have these skills yet, you know what you need to work on. Out of all the resumes we looked through, 77.3% of dance therapists listed group therapy on their resume, but soft skills such as leadership skills and listening skills are important as well.

Choose From 10+ Customizable Dance Therapist Resume templates

Zippia allows you to choose from different easy-to-use Dance Therapist templates, and provides you with expert advice. Using the templates, you can rest assured that the structure and format of your Dance Therapist resume is top notch. Choose a template with the colors, fonts & text sizes that are appropriate for your industry.

Choose a template with the colors, fonts & text sizes that are appropriate for your industry.

Dance Therapist Demographics

Dance Therapist Gender Distribution

Female

After extensive research and analysis, Zippia's data science team found that:

- Among dance therapists, 92.9% of them are women, while 7.1% are men.

- The most common race/ethnicity among dance therapists is White, which makes up 74.9% of all dance therapists.

- The most common foreign language among dance therapists is Spanish at 100.0%.

Online Courses For Dance Therapist That You May Like

Advertising Disclosure The courses listed below are affiliate links. This means if you click on the link and purchase the course, we may receive a commission.

Occupational Therapy Introduction - ACCREDITED CERTIFICATE

How to become occupational therapist, basic Psychology, Physiology & Anatomy, working with disabilities, children adults. ..

..

View Details on Udemy

CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Therapists & Coaches

(1,237)

Comprehensive CBT Therapy Training Cognitive Behavior Therapy Practitioner Level Treat Anxiety, Depression & More...

View Details on Udemy

Introduction to CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

(4,168)

Online Counselling & Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Training Course...

View Details on Udemy

Show More Dance Therapist CoursesJob type you want

Full Time

Part Time

Internship

Temporary

How Do Dance Therapist Rate Their Jobs?

Do you work as a Dance Therapist?

Rate how you like work as Dance Therapist. It's anonymous and will only take a minute.

Top Dance Therapist Employers

Most Common Employers For Dance Therapist

| Rank | Company | Average Salary | Hourly Rate | Job Openings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cottage Hospital | $53,670 | $25. 80 80 | 1 |

| 2 | MemorialCare | $52,648 | $25.31 | 5 |

| 3 | Austin State Hospital | $52,248 | $25.12 | 1 |

| 4 | Miami-Dade County Public Schools | $50,257 | $24.16 | 1 |

| 5 | Whitehall Services Inc. | $48,811 | $23.47 | 1 |

| 6 | Courtland Consulting | $48,205 | $23.18 | 1 |

| 7 | The Wealshire/ The Ponds | $47,545 | $22.86 | 1 |

| 8 | Manhattan Psychiatric Center | $43,102 | $20.72 | 1 |

| 9 | The League for People with Disabilities | $40,697 | $19.57 | 1 |

| 10 | Health Education Council | $33,597 | $16.15 | 1 |

Updated September 9, 2022

Dance Therapist | Berklee

Career Communities

- Communities

- Industries

- Locations

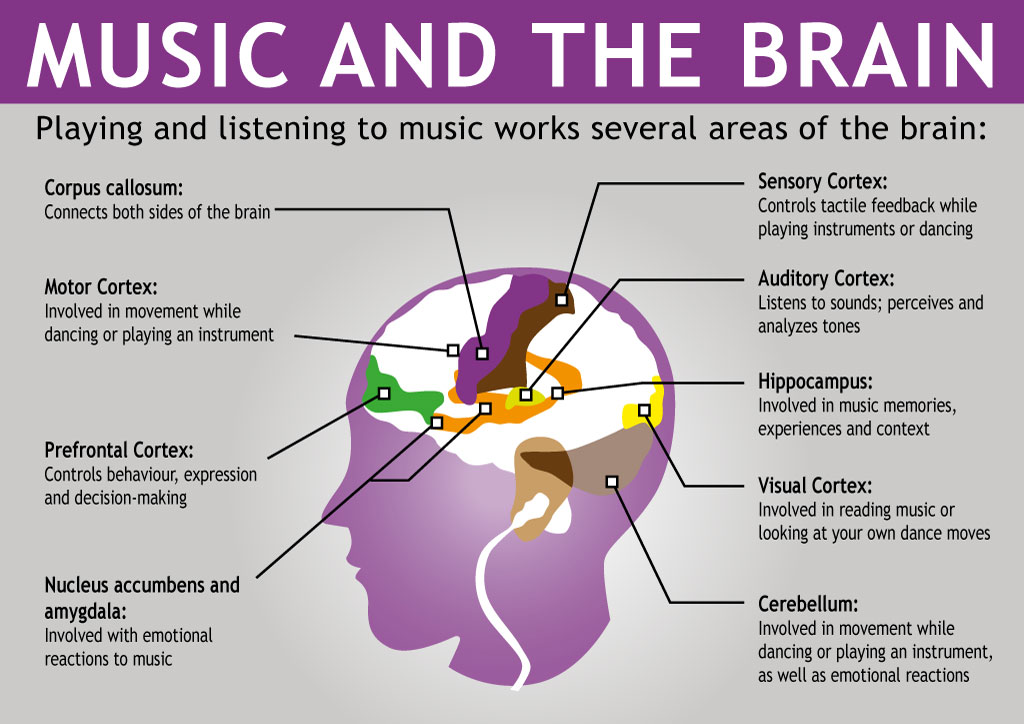

The power of structured movement like dance to aid physical rehabilitation and improve coordination, strength, and health is well known. However, few are aware that dance and movement activities can also improve psychological, emotional, and behavioral health. Dance therapists work on the understanding that the body and mind are deeply connected, and utilize this connection both to assess and treat their patients.

However, few are aware that dance and movement activities can also improve psychological, emotional, and behavioral health. Dance therapists work on the understanding that the body and mind are deeply connected, and utilize this connection both to assess and treat their patients.

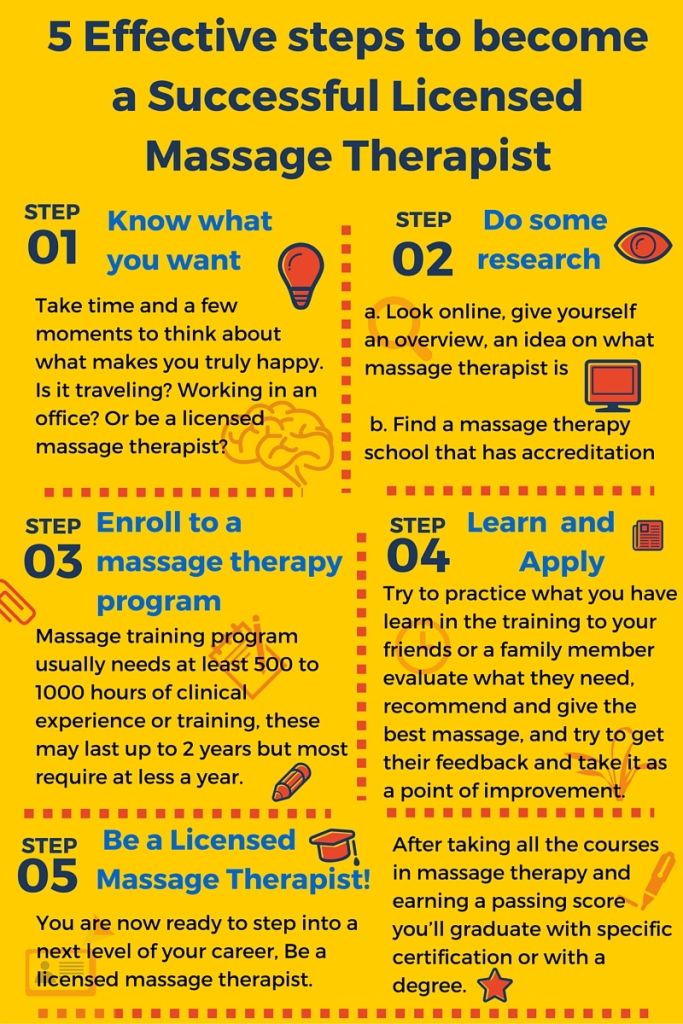

Working as a dance therapist generally requires an undergraduate degree, in addition to a master's degree or post-graduate program approved by the American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA).

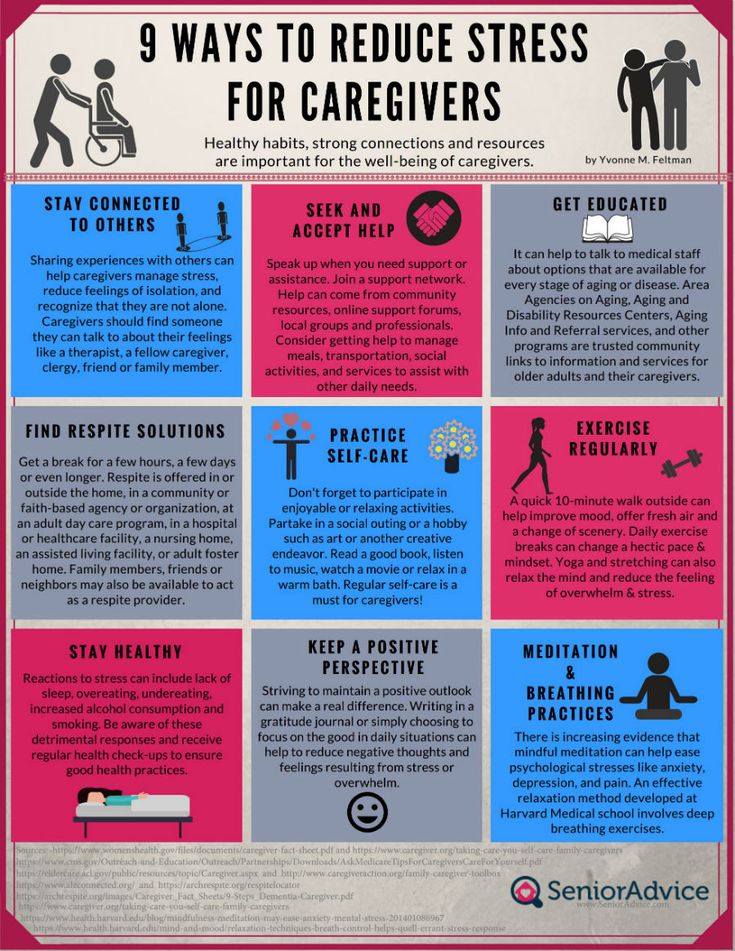

Clients come to dance therapists with a variety of ailments, including chronic illness, anxiety, depression, OCD, abuse, trauma, and eating disorders. It’s the dance therapist’s job to assess their needs, invite them into a safe therapeutic space, and create tailored sessions that utilize a combination of movement exercises and choreography activities—in a wide range of styles—to treat them. Although movement itself can have great therapeutic value, reducing stress and improving mood management, dance therapists are equally interested in what lies beneath the movements: a hidden language that they can interpret, helping bring to light repressed thoughts, memories, attitudes, and feelings.

At a Glance

Career Path

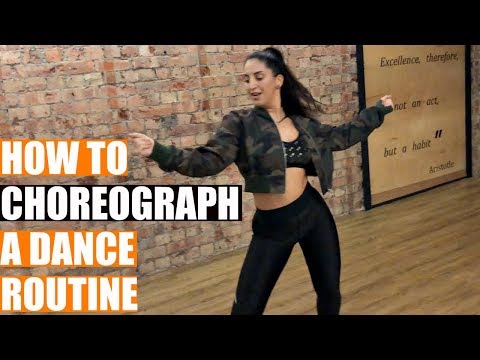

Most dance therapists get started as dancers or choreographers. Working as a dance therapist generally requires an undergraduate degree, in addition to a master's degree or post-graduate program approved by the American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA). In order to advance within the field, dance therapists might seek additional training—also ADTA-approved—to become board-certified practicioners, or pursue licenses, which are awarded on a state level and possess differing requirements. Dance therapists might also go on to work with or found dance therapy-focused nonprofit organizations, or incorporate other art forms into their practice, becoming creative or expressive arts therapists.

Finding Work

Dance therapists work in a wide variety of settings, from medical, rehabilitation, and drug treatment facilities to schools, community centers, and prisons. They can also create their own opportunities by founding private practices, or work within a local community as freelancers.

Professional Skills

- Dance performance and choreography in a wide variety of genres

- Assessing clients' needs and developing treatments

- Teaching

- Anatomy

- Research

- Establishing therapeutic relationships

- Empathy

Interpersonal Skills

Dance therapists should strive to be patient, perceptive, and persistent. Analytical skills are helpful in assessing clients' needs and interpreting their communication through movement, but perhaps more critical are empathy and emotional openness, which can go a long way towards making clients feel safe and comfortable. Of course, excellent communication skills will only help.

Work Life

Dance therapists might work a fairly predictable daily schedule in a school, hospital, or mental health institution, combine a number of small gigs in different settings, or create their own schedule working out of a private practice. While dance therapists might spend some time at a desk organizing clientele, seeking out new jobs, or taking care of billing and other paperwork, the majority of their workday is spent on their feet with clients. Time is also set aside for continuing one's education and acquiring new tools and approaches.

Time is also set aside for continuing one's education and acquiring new tools and approaches.

Grow Your Network

The Chace Approach to Dance Therapy

| Comment: This article was written jointly by the authors, last names are listed in alphabetical order. The authors studied with Marian Chase at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington for a year (1964-1965), Claire Schmeis also took a course with her in March 1960 at the School of Music (New York). By observing and talking with Chase, the authors were able to absorb, understand and apply her method of using dance in therapy. It was not easy for her to share her vast knowledge and experience, but if someone showed a persistent desire to learn, Chase was a generous and patient mentor.

Chaiklin S. & Schmais C. The Chace Approach to Dance Therapy. // Theoretical Approaches in Dance-Movement Therapy. Ed. by Penny Lewis. Kendall/Hant Publishing House, Iowa, USA. Translation: A. Garafeeva, B. Labkovsky, T. Oberemko |

History

1what I learned from Marian Chase from my feelings for her. She was a strong and complex woman, and not everyone could understand and accept this. I was very worried in anticipation of a meeting with M. Chase, when at 19In 1964, I visited her at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington. Chace's articles touched something important in me. For many years I have been looking for how to fulfill my interest in dance and people. What she was describing in her work seemed to offer an answer, but I didn't know what it was yet.

We met that day and agreed that I would come every week. I started working in her groups as a participating observer, some of them led by Katerina Hamilton (Pasternak). I accompanied Chase everywhere: I observed, participated and asked endless questions. I soon realized that there were no observers in her groups, only participants. I was completely involved.

I was completely involved.

Gradually I was allowed to lead part of the class, and finally to lead when Chace left. I also enjoyed the privilege of watching and assisting her in the annual productions with patients she performed. A year later, I received her "permission" to work in another clinic.

Marian Chase taught but never explained everything. To some extent, after training at St. Elizabeth's Hospital, I acted like a teenager. There was so much more to be understood, perhaps the "old lady" did not know so much. But since then, experimenting, learning from others, growing, growing up, re-learning and integrating have become my constant process. The more I learned, the more I understood what I first perceived, albeit dimly, from Marian.

Single, short sentences typical of Marian Chase seemed to get deeper and deeper. Some of them I seemed to see for the first time, because only now I understood them. One can perceive the knowledge and ideas offered by others, but they must be implemented and passed through one's own experience, vision and interaction with the world. It is difficult for me now to separate what I received for the first time from Chace from what I acquired later.

It is difficult for me now to separate what I received for the first time from Chace from what I acquired later.

It became mine, and it is a gift received from her, for which I will always be grateful.

In recent years, I have often really missed Miss Chase. I miss her because I have reached the point where I can discuss and ask deeper questions, and I would like to hear her opinion. I miss her because I could now share with her as an equal and thus lighten her burden as a trailblazer.

I know that now I am closer to understanding. I can solve many problems myself. I also learned this from Marian Chase.

Theoretical model

In the 1940s and 50s, Marian Chase was the first to use dance as a therapy. She reworked, improved and expanded her ideas and gradually created the principles and methods that are now considered as the theoretical basis of dance therapy. However, she never systematized this material. Her articles were always dictated by immediate tasks, such as lectures, conferences or journal publications. Thus, they were limited by the requirements of a particular context. It is clear that much thought and scholarship formed the basis of her work, although the existing records do not contain any references or bibliographies. In her written work, the main concepts are presented clearly and concisely, yet they remain as deep and relevant as when they were first articulated by her (Chaiklin, 1975).

Thus, they were limited by the requirements of a particular context. It is clear that much thought and scholarship formed the basis of her work, although the existing records do not contain any references or bibliographies. In her written work, the main concepts are presented clearly and concisely, yet they remain as deep and relevant as when they were first articulated by her (Chaiklin, 1975).

Chace began using dance as a therapy when she taught modern dance in her own studio. However, her ideas were most developed during her work at St. Elizabeth's Hospital, where she began working in the 1940s. At that time, tranquilizers and other drugs had not yet begun to be widely used. She was able to test her theories on patients who exhibited a wide range of disorders such as violent behavior, catatonic withdrawal, hysteria, and so on.

Dance is communication

Chase's main contribution lies in recognizing and identifying those elements of dance that serve therapeutic purposes and in developing the therapist's interactive role at the motor level.

The basic concept from which all others stem is that dance is a communication that relates to basic human needs. It seems to us that there are four main categories, encompassing the basic principle that Chase used in therapy. Although they are not defined in this way in her notes, we believe that they are the underlying concepts of her work, as she constantly reiterated and emphasized these ideas.

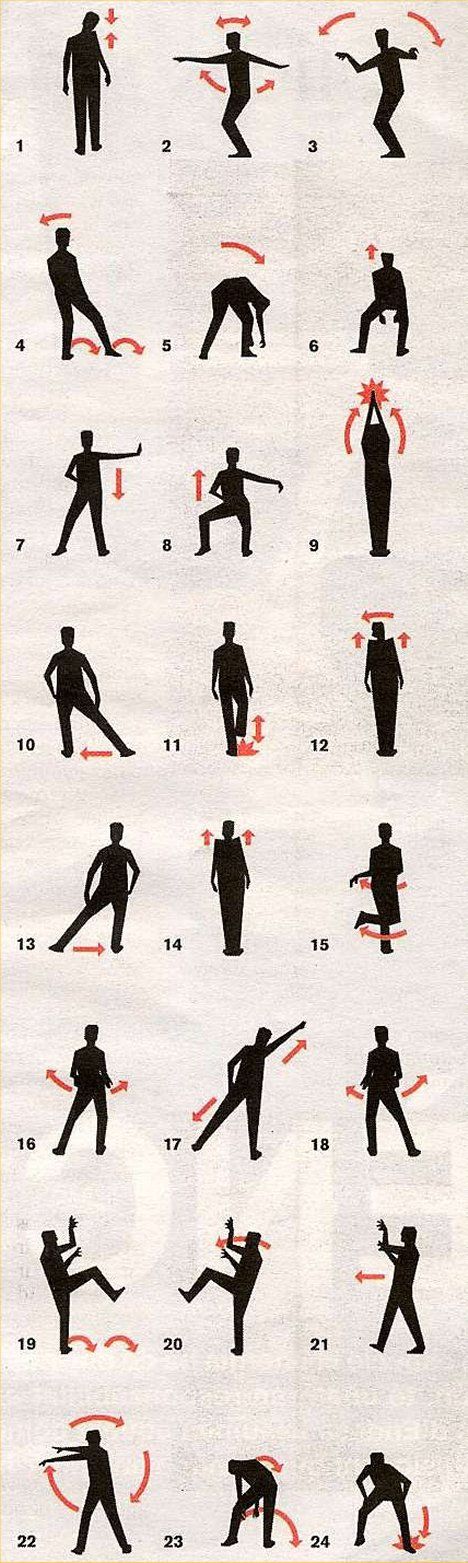

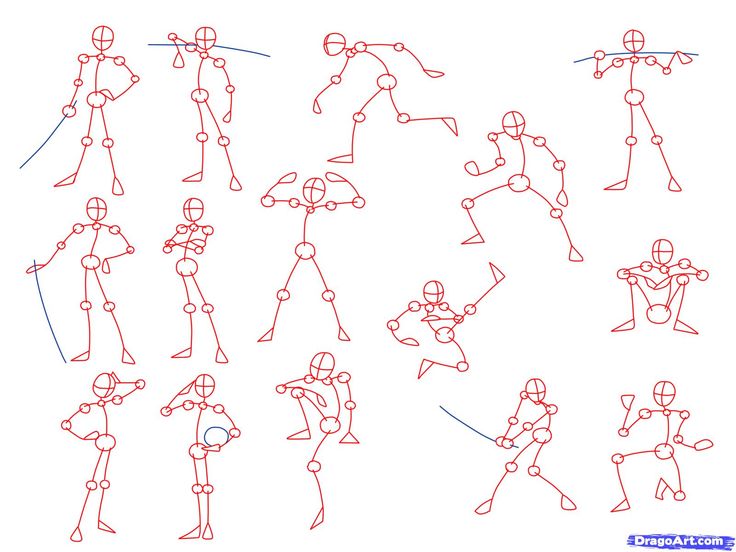

1. Body action

Chase believed in the intrinsic value of a lean, coordinated and healthy body. She viewed the disruption of body form and function as an unfortunate adaptation response to conflict and pain. "When emotions become pathologically oriented, body image begins to distort" (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 231). For example, some people block energy by restricting their actions in space, losing touch with body parts, or holding their breath to protect themselves from feelings such as guilt, aggression, or sexuality. Others become hyperactive, exploding in time and space in response to real or imagined fears.

Chase realized that dance moves help patients feel relaxed and stimulated at the same time, which prepares them to express emotions. "Because the muscular activity that expresses emotions is the basis of dance, and since dance is a means of structuring and organizing such activities, it can be assumed that dance could be a powerful means of communication for the reintegration of patients with severe mental disorders" (Chaiklin, 1975, p. .71).

With the help of dance movements, the patient acquires the mobility of the skeletal muscles. Awareness of body parts, breathing patterns, or the degree of tension that blocks emotional expression gives the therapist the key to identifying a sequence of physical actions that can develop emotional readiness. But it is not simply memorizing the movements that lead to change: change occurs when the patient is willing to allow himself to experience the action in his body. There is a close relationship between the integration of changes in posture and changes in mental attitude.

It is only when he is ready that it becomes meaningful to him and causes changes in his body image. You can ask a person to raise his hand, but until he feels this movement inside, it will not become real in the body (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 229).

Understanding the innate relationship between mobility, dance and emotional expression, the therapist helps the patient to move and follow his inner movement impulses.

2. Symbolism

Both psychotic patients and dancers use symbolic bodily action to convey emotions and ideas that defy everyday language; but their intentions are different. If the dancer can impartially choose strange and exaggerated poses to communicate with the audience, then the patient expresses his subjective emotions in a single moment, conveying the complexity and depth of feelings that he cannot put into words.

"Basic dance" 2 is the outward expression of inner feelings that cannot be expressed in rational language, but can be conveyed through rhythm and symbolic action" (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 203)

203)

The versatility of these non-verbal symbols can help break through the barriers of disease, age, and culture. Schizophrenics in particular feel more confident in the symbolic language of movement, while in the language of words they often cannot communicate and do not benefit from verbal interaction. The camouflage of the movement symbol makes it easier for these patients to express their needs, feelings, and desires.

Mrs. R. withdrawn... curled up, remains in the corner of the room, absorbed in her feelings... Suddenly, after a large circle has been formed, she begins to stamp her foot rhythmically. Following this movement, she moves around the room, but remains outside the circle of other dancers. When she stomps, she moves her shoulders forward in sharp, alternating jerks, stretches out her arms and sings to the rhythm of the music about her loneliness and isolation.

Recently, she suddenly demanded: "Put it on again. It looks like 1920." And when asked if she knows this music, she replied: "It refers to the time when I was just starting.

" The music was repeated and she continued to dance with extraordinary intensity throughout the session. By the end of the hour, she relaxed, sank heavily into a chair, and in response to the question: “Are you tired?”, She said: “Yes. I just lived 20 years, and now I'm here” (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 142) .

Symbolism in dance therapy is the medium by which the patient can remember, replay and relive his material. Some problems can only be worked out on a purely symbolic level. The dance therapist accepts the patient's symbolic meanings. The patient feels that he is understood, and this allows him to continue the symbolic narrative.

The dance therapist not only reacts to the patient's symbolic expressions, but also adds content himself. Together they create a new symbolic interaction. Since dance and emotional expression involve the same neuromuscular pathways, the dance therapist uses this connection by choosing appropriate dance patterns. For example, to help a patient who is holding back feelings of anger, the therapist might suggest the image of chopping down a tree. The strong, direct movements required for such activity can bring feelings of anger or hatred to the surface. Dance moves can also evoke special memories.

The strong, direct movements required for such activity can bring feelings of anger or hatred to the surface. Dance moves can also evoke special memories.

Jumping and jumping can trigger unexpected memories of incidents and events from childhood.

3. Therapeutic Movement Relationship

Chase discovered how to establish a therapeutic relationship at the movement level. She achieved this by relying on the visual and kinesthetic perception of the patient's motor expression. Using her high sensitivity and skills, she was able to reproduce the emotional content of the patient's behavior in her motor response. With her movement, she literally said "I know how you feel" and thus established an effective empathic interaction:

Ms. H. is dancing, absorbed in her fantasies. She uses music without paying attention to its timbre, although she follows the rhythmic pattern. When she moves quickly around the room, there is no feeling that she is aware of the surrounding space.

Her feet barely touch the floor; her arms can stretch out to the sides, but not into space. She can stretch out in an exaggerated gesture, but he looks strangely disembodied. This creates a feeling of loneliness and detachment that accompanies any other emotion, such as hatred, fear or some kind of need, that arises as themes of her dance.

It was almost impossible to contact this patient through words. She is preoccupied with her own world and unable to listen with understanding. However, she can be approached through a dance that is similar to her own. The patient will accept another dancer, although her sense of isolation may persist for some time. The therapist is in interaction with the client for short periods of time, gradually increasing their duration. Finally, the patient usually glances at the other dancer, then a quick hello, and a smile in return sets the start of a new interaction (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 140-141).

Chase entered the patient's world by reproducing the main semantic movements characteristic of his expression. As she replicated the patient's behavior in her own body, she sensed opportunities to develop interaction through repetition, extension, and addition of movements. At different moments it reflected, continued or supplemented the patient's movement, signaling in such a way that his behavior was understood. By performing an important gesture at the right time to the extent that the patient could accept it, Chase established a trusting relationship that gave the patient the opportunity to share his repressed ideas and feelings and to take risks, to venture into new experiences and interactions.

As she replicated the patient's behavior in her own body, she sensed opportunities to develop interaction through repetition, extension, and addition of movements. At different moments it reflected, continued or supplemented the patient's movement, signaling in such a way that his behavior was understood. By performing an important gesture at the right time to the extent that the patient could accept it, Chase established a trusting relationship that gave the patient the opportunity to share his repressed ideas and feelings and to take risks, to venture into new experiences and interactions.

4. Rhythmic group activity

Rhythm underlies all aspects of human life. In everyday activities, talking, walking, working and playing would be chaotic if they were not structured in time. The flow of inhalation and exhalation, the uniformity of the pulse represent the individual rhythms of a person, while the group moving together seems to have one breath and one pulse.

Chase often referred to "primitive dance" when explaining the meaning of rhythm:

Even primitive man understands that a group of people moving together evokes a feeling of greater strength and security than any individual can feel alone (Chaiklin, 1975, p.

54).

I believe it was no accident that primitive man resorted to music and dance (or rhythmic activity) to honor and reinforce the sense of the group in the community. It is no coincidence that the "magic" of the healer (or spiritual leader) was manifested through ritual chanting and bodily actions (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 61).

Chase understood rhythm as something that organizes individual behavior and creates a sense of solidarity and belonging between people. For example, patients who experience difficulty or resistance to following a spatial pattern of movement may work with a group rhythm. When feelings are expressed in a common rhythm, each participant draws energy from a common source and experiences an increased sense of strength and security.

The dance therapist uses the most basic forms of emotional expression. An element of rhythm is added to the movement, which is used by everyone. Although these movements are often outside the patient's awareness, they are placed in the focus of attention through a general symbolic rhythmic action. Chase viewed rhythm as a therapeutic means of communication and body awareness.

Chase viewed rhythm as a therapeutic means of communication and body awareness.

These four basic concepts, which we have named: bodily actions, symbolism, therapeutic movement relationships and rhythmic group activity, form the foundation on which the theory of dance therapy is built.

Psychiatric setting

Chase developed her approach to dance therapy at St. Elizabeth Mental Hospital in Washington DC. The dance therapy section was part of the psychotherapy unit and Chase participated in case discussions and other clinical and educational activities.

Chace has worked with all patients - short-term positive patients and long-term chronic patients in the furthest wards. Most sessions took place indoors at the ward, so that patients had the choice to participate or leave the session. Patients who were not ready to actively participate in the group could join the group dynamics by remaining on the periphery. A separate dance therapy room allowed patients who were quite independent to come in for individual sessions.

Patients

While most sessions were in groups, with patients who needed more direct contact, Chace worked individually. These patients either found the group sessions too intimidating or were too demanding and disruptive to the group. Patients were also referred to her, whose lack of verbal communication and the ability to interact caused anger and frustration of the staff.

Chase characterized the motor patterns of three types of patients. These are: manic, depressive psychotic and schizophrenic.

The manic patient, as she describes it, bursts into space with exaggeratedly rapid movements. Due to its speed and lack of spatial boundaries, these movements are perceived as aggressive, but they are rarely directed towards another individual.

The ability to use movement as a direct expression of emotions, together with its dominance in the surrounding space, makes the manic patient an excellent and inspired dancer. His dance moves are exaggerated, strong, perfectly coordinated, but they always seem to be an expression of anger, emptiness and despair.

He seems to have no idea of himself as a successful person in his mind, but only as aspiring somewhere, attacking, and then giving in to despair (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 135).

Although the actions of the depressed patient are not as striking as those of the manic patient, they nevertheless reveal his inner feelings. Within this category, Chase describes two kinds of patients. One is lethargic, slow to react, indifferent to the world around him, and yet aware of his own reactions.

Patients experiencing the state of inhibition that accompanies emotional depression seem to be more aware of their bodily reactions than most psychiatric patients. They seem to feel additional anxiety caused by their inability to act in a conventional way. They often seek dance activity as a constructive way to alleviate their fear and confusion (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 136).

The second type of depressed patient interacts with his feelings, engaging in endless, unsatisfactory activities.

It seems that the patient who expresses his depression in relentless action does not feel the reduction of his anxiety in these endlessly repetitive movements. A person can walk 24 hours a day, rub his hands or constantly rock in a chair, but the tension of the body at the end remains as strong as at the beginning, although there is no doubt about the feelings played out by these actions ... If the patient is left to himself himself or just talk to him, he will make such movements for a long time. However, it often responds to rhythmic movements. He can be encouraged to move in a completely different way and use other modes of movement, and the tension will be relieved to such an extent that he can enter into conversation, laugh and join the work of the group, albeit temporarily (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 136-137).

At first glance, bizarre movements of a schizophrenic are characterized by a departure from space, only peripheral parts of the body participate in the movement: the head, feet or hands. This particular style directly conveys his feelings of fear, guilt, or hostility.

This particular style directly conveys his feelings of fear, guilt, or hostility.

Through movement, he also expresses his feelings of helplessness and dependence. It is natural that his anxiety does not decrease with a change in body posture, since he does not receive a satisfactory response from his environment at the level that he is able to perceive. He seems lost in the four-way lack of communication. The patient expresses himself verbally in a way that is incomprehensible to most and not perceived by others. People around him speak in a way that he does not understand, and the non-verbal expression of feelings also remains unconscious to him (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 137).

Goals

As a dance therapist, Chase set long-term goals for working with each person's limitations. She was aware of the possible directions in which one could work with each individual and with the group as a whole, and determined her own goals for each occupation. The main part of the experience was built in such a way that it served as an intermediate step to achieve the ideal. Short-term goals changed from situation to situation as relationships changed and patients took risks to gain new experiences.

The main part of the experience was built in such a way that it served as an intermediate step to achieve the ideal. Short-term goals changed from situation to situation as relationships changed and patients took risks to gain new experiences.

Although we categorize these goals according to the concepts of body movement, symbolism, therapeutic movement relationship, and rhythmic group activity, it must be understood that there are continuous and dynamic relationships between them.

Aims consistent with the concept of the therapeutic relationship:

1. Establishing one's own identity.

2. Development of trust.

3. Promotion of independence.

4. Recreation of conscious interaction in society.

5. Developing and maintaining one's integrity while accepting social influences.

Targets according to the concept of body movement:

1. Create a realistic image of the body.

2. Activation and integration of body parts.

3. Gestalt posture reconstruction.

4. Awareness of inner sensations.

5. Energy mobilization.

6. Development of possession and control of body movements.

7. Expansion of the expressive range.

Targets corresponding to the concept of symbolism:

1. Integration of words, experiences and actions.

2. Putting on a concrete outer form of inner thoughts and feelings.

3. Expansion of the symbolic repertoire.

4. Restoration of important events of the past.

5. Resolving conflicts through action.

6. Achieving insights.

Goals corresponding to rhythmic group activity:

1. Feeling of one's own vitality.

2. Participation in a shared experience.

3. Canalization of energy within a framework.

4. Awareness of others and one's own responses to them.

5. Development of ways of interaction.

6. Building connections between people with very different feelings and lifestyles.

7. Developing an understanding of the feelings and experiences shared by others.

8. Development of openness to new knowledge and self-acceptance.

Therapeutic process

For Chase, the session began the second the door opened and she entered the room. She calmly greeted patients and staff as she walked past them, weaving a thin, barely perceptible web of communication with her presence. This greeting process gave her many clues about the energy and mood of those present. She noted what the patients did, what they didn't do, whether they spoke or were silent, the degree of isolation, disconnection, and any other significant details. In the few minutes it took her to get in, put on the record, and turn on the turntable, she was able to gauge enough of the group's mood, tension, and configuration to determine how best to start.

If the general mood of the group was quiet and depressing, she started with calm, slow music that reflected this feeling. If the room was noisy and tense, she turned on energetic music with a clear rhythm. This helped to set the overall attention in such a way that individuals could begin to interact in unison with each other. Most often, there were many emotional nuances at the same time. Chase then began waltzing, which she considered relatively neutral, evoking few strong emotional responses, and, at worst, simply "boring." Since she understood that music evokes many reactions due to the rhythm, feeling, intonation and personal memories associated with individual pieces, each entry was chosen very carefully.

Most often, there were many emotional nuances at the same time. Chase then began waltzing, which she considered relatively neutral, evoking few strong emotional responses, and, at worst, simply "boring." Since she understood that music evokes many reactions due to the rhythm, feeling, intonation and personal memories associated with individual pieces, each entry was chosen very carefully.

Whether these were new patients or she had already worked with them, she usually began by quickly picking up and responding to the verbal and bodily messages of one patient, and then quickly moved on to another.

Although contacts are made in the space of the room on the basis of the individual interaction of the therapist with the patient, several such contacts can occur almost simultaneously. The action of the dance is so fast and so fluid that when the therapist leaves one patient to immediately meet another, the emotions experienced and expressed can change as she turns.

During this time, the therapist feels that he is building multiple individual lines of communication, none of which can be neglected even for a moment. Gradually, they grow into group activities in which she acts as a catalyst (Chaiklin, 1975, pp. 74-75).

She invited participation but knew how to let people say no. During therapy, all movements were considered significant and expressive. Movements indicating hostility, aggression, withdrawal, isolation, or any other feeling were equal in importance to direct interactions. This focus led her to argue that dance therapy should work with the "healthy parts" of the personality. Her sense organs were open, and she perceived the rhythm, the muscle tension, which parts of the body were being held back and which parts were being used, which affects or emotions it corresponded to. She reacted to each patient depending on the characteristics of his motor configuration.

One patient is standing leaning forward, contracted in the abdomen, his whole posture is that of a person in a state of horror.

The therapist feels the tension in her own abdomen, and using this as the center of action, she unfolds a chain of dance moves to release the tension. The initial contraction she feels can be translated into an expansive movement, or else into some kind of relaxed action, neither of which can be interpreted as a threat. In any case, it must repel or be closely related to the patient's own contracted movements (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 73).

At the same time, she did not just try to accurately reflect, mirror the movement of the patient. She used her own body movement to understand and thus communicate the acceptance and validity of his expression. There is a fine line between motor empathy and imitation. Imitation involves the repetition of the external outlines of the movement without the emotional content that exists in the dynamics and fine organization of the movement.

Ms. A. made threatening attacks on the nurses. The attending physician, who was familiar with dance therapy classes, suggested that I dance with her.

Although the space was limited to an island between the beds, we danced wildly together. In this case, I met her hostile attack movements exactly the same. The patient danced in an attacking manner, playing the role of a child in anger, typing a step and swinging her fists in the direction of the attack, apparently trying to destroy her partner in the dance. I reacted by responding with movements of hostility. However, Miss A. never actually touched me, and she moved to the beat of the music the entire time she pretended to fight. Later, when she had used up a lot of energy in this way, I sank to the floor, pretending to be defeated. Miss A calmly returned to her bed…" (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 139).

Chace understood that responding with similarly shaped movements dispelled the feeling of isolation, while verbal battles reinforced that feeling. She did not cover up her sadness or pain with feigned amusement. To empathize, to be empathic, was to share the essence of non-verbal expression, which resulted in what she called "direct communication. "

"

You can see how the initial contacts develop and a dynamic group is formed. The therapist moves from one patient to another, reflecting different rhythms and moods. She has a keen sense of how much time each person needs, anticipates the acceptable degree of intimacy, the way of communication, touch, and completes before the patient feels threatened or wants to make a move to leave. This approach respects the patient and allows him to come and go. The therapist is open to physical contact and will reach out when he or she decides the patient is ready to receive it. However, the first touch is the prerogative of the patient. Similarly, the distance and space used are determined by the movement of the patient. The therapist moves rhythmically around the room to one patient, then from him to another, developing a continuity of action and energy that is based on the emerging motor expression. The flow of traffic begins to connect one patient to another. The therapist's presence and movements throughout the room begin to define the space and structure.

Individual boundaries begin to lose their distinctness, and thus a collective space emerges. As each patient establishes a relationship with the therapist and wants to connect with others, a circle is formed. The circle shape allows for equal participation, visual contact among group members, and a sense of security in a clearly defined space. Patients can leave and return without disrupting groups. They can be in it, outside it, on its periphery, while remaining a part of it. The circle can grow or shrink, allowing you to vary the touch and distance. Leadership can easily shift from one group member to another, and people can choose who they want to follow, be around, and avoid.

The circle is the primary structure from which other forms of relationship can develop. His education indicates the beginning of group work. When the circle becomes a safe place, group members can take on a variety of forms, such as lines, group clusters, and even relatively indefinite forms of movement. The acceptance of the diversity of structures reflects their changing attitudes and relationships.

The acceptance of the diversity of structures reflects their changing attitudes and relationships.

The purpose of the first part of the session, "warm-up", is to mobilize the group's ability for emotional expression and interpersonal interaction. The therapist, as a member of the circle, begins the session with a simple movement such as shaking hands. She performs movements that involve all the joints one after the other until the whole body is warmed up. The more parts of the body are involved in the action, the more part of the personality is involved in the movement. The need for pace and energy gradually increases, resulting in deeper breathing that merges with movement. At the same time, changes in relationships become possible due to variations in the amplitude of movement in relation to the body and to the surrounding space. For example, someone may reach out to someone or move away. During this period, the therapist successfully establishes eye contact with each member of the group and at the same time adjusts his movements to reflect the unique style of each person. It moves simply, rhythmically and constantly repeating so that all participants can join in the action and feel like part of the group. The sequence of movements must have some bodily logic, i.e. flow easily from one part of the body to another, be aesthetically justified and convincing. The dance must be attractive so that patients want to join.

It moves simply, rhythmically and constantly repeating so that all participants can join in the action and feel like part of the group. The sequence of movements must have some bodily logic, i.e. flow easily from one part of the body to another, be aesthetically justified and convincing. The dance must be attractive so that patients want to join.

Once contact is established, the therapist gradually increases the patient's movements to make them more apparent. By exaggerating and clarifying the form and dynamic content of the movement, it makes the patient more aware of his own intentions and tendencies to act or not to act. The therapist is the catalyst through which different experiences are expressed and shared. By demonstrating her readiness for emotional expression, she tests the patient's willingness to take the risk of expressing her feelings more directly. One of our patients, who had difficulty giving or taking anything, was helped to symbolically re-enact this conflict. To do this, he simultaneously used one hand to give and the other to take. The participation of group members in the structure of the movement serves as a kind of further permission and support for the patient to symbolically play out his repressed feelings and desires in a safe place.

To do this, he simultaneously used one hand to give and the other to take. The participation of group members in the structure of the movement serves as a kind of further permission and support for the patient to symbolically play out his repressed feelings and desires in a safe place.

The therapist makes a choice each time, reinforcing those movements of the patient that lead to healthier functioning. She works with the reality of the moment. Random movements are not offered. Instead, the therapist moves with the patient to help him expand and develop his movement repertoire. This may take the following form: the patient's ability to be strong in one part of the body can be extended to the whole body; moving from trial opening and closing to moving towards and away from someone; the development of a partly aggressive movement into a full blow to a specific target; channeling disparate strikes into focused, controlled actions.

The therapist also supports spontaneous changes in established movement patterns. Subtle differences are clearly reflected by the therapist in order to reinforce the new behavior. This process allows the patient to respond to situations in a new way, perhaps with a strength he never knew he had, or with a tenderness he had never before dared to express.

Subtle differences are clearly reflected by the therapist in order to reinforce the new behavior. This process allows the patient to respond to situations in a new way, perhaps with a strength he never knew he had, or with a tenderness he had never before dared to express.

Attunement to an emotional state is only the beginning of a therapeutic relationship. This is the material on which the therapist develops a motor dialogue, a group dance, the purpose of which is self-awareness and emotional development. By recognizing his own movement intentions and reactions to the group "gestalt" and by perceiving the evolving movements of group members, the therapist decides what should follow. The therapist uses the motor expression of group members, develops them and encourages spontaneity and integrity of rhythmic interaction. Like a choreographic passage, the initial period of development leads to the main part of the lesson, which may be centered on one or more topics. Themes are chosen from what has arisen in the movement - helplessness, distrust, disunity, loss, or any other human feeling or need.

Ms. Y. had unhealthy thoughts about death and destruction. In fact, she used to see death as a solution to serious problems and killed her husband. Her creative dance during one psychotic episode inevitably led to this theme. In order to teach others how to group dance based on her ideas, she needed to put her creative thoughts into structure so that she could connect with other people for the first time during her stay in the hospital. Creative dance provided the basis for this structure. She concentrated on the patterns of her thoughts so that the group could reproduce it, thus arousing her interest in structured forms that were beyond her subjective painful emotions. In this case, creative art proved to be useful, but only in combination with the need to teach, which forced her to put her thoughts in an objective form, and not express her pain directly and exaggeratedly (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 216).

Occasionally, feelings are expressed verbally, but more often than not, the therapist carefully thinks out the topic based on the patient's symbolic motor expression. Her concern is to develop topics carefully selected during the "warm-up" that will allow each person and group to grow and develop as a whole. The quality of movement, the arrangement of space and rhythms are determined by the intersecting needs of individuals and groups. Each movement, carefully selected by the therapist, is based on the expressive context of the individual members of the group. These movements are outlined and framed by the therapist in a way that allows the group to function as a whole. The choice depends on the readiness of the group to turn on and support the individual member of the group and his particular emotional expression. During the session, the therapist seeks to capture and to some extent develop the movements of each member of the group.

Her concern is to develop topics carefully selected during the "warm-up" that will allow each person and group to grow and develop as a whole. The quality of movement, the arrangement of space and rhythms are determined by the intersecting needs of individuals and groups. Each movement, carefully selected by the therapist, is based on the expressive context of the individual members of the group. These movements are outlined and framed by the therapist in a way that allows the group to function as a whole. The choice depends on the readiness of the group to turn on and support the individual member of the group and his particular emotional expression. During the session, the therapist seeks to capture and to some extent develop the movements of each member of the group.

While movement is the primary means of therapeutic intervention, imagery, syntax, and timbre of the voice are also used to advance the therapy process during dance therapy sessions. A verbal image often helps to determine the quality of movement that a person is striving for. Asking the patient to walk quickly will elicit one response, and asking the patient to imagine walking on a hot sandy beach will elicit another response. The therapist encourages participants to develop imaginations related to their own lives and fantasies and to share these fantasies with the group.

Asking the patient to walk quickly will elicit one response, and asking the patient to imagine walking on a hot sandy beach will elicit another response. The therapist encourages participants to develop imaginations related to their own lives and fantasies and to share these fantasies with the group.

There is a difference in how we elicit a response: with a demand or with a question. For example, the question "How tall can you be?" elicits many different responses, including "I can't be tall." While the requirement: "Be tall", does not give the patient a choice. Questions are also used to develop simple movements into symbolic actions. For example: "Can you push, slash, swim, etc.?" The next level of verbalization can move the patient from action to interaction, connecting awareness with physical action. For example: "Who are you pushing? What are you chopping now?"

The therapist uses tone of voice to express the mood and feelings of the group. It can be soft or provocative, it can be angry or demanding. Voice quality enhances movement dynamics and serves to communicate with patients who cannot bear eye contact. This constant conversation of the therapist helps maintain the state of the group. It is especially useful in those moments when the movement is difficult to see or make. In addition to this, continuous verbalization facilitates the emergence of insight, as well as the definition of affect and further interaction. There may be moments when the movement stops and the conversation just continues. But more often words are woven into a constant movement, where one reinforces the other.

Voice quality enhances movement dynamics and serves to communicate with patients who cannot bear eye contact. This constant conversation of the therapist helps maintain the state of the group. It is especially useful in those moments when the movement is difficult to see or make. In addition to this, continuous verbalization facilitates the emergence of insight, as well as the definition of affect and further interaction. There may be moments when the movement stops and the conversation just continues. But more often words are woven into a constant movement, where one reinforces the other.

Group members are encouraged to use words and sounds to support their actions. Sometimes the band finds connecting rhythms without having to use music. Patients make noises, clap their hands, stomp, or sing.

The session usually lasts about an hour. The relative duration of the initial warm-up, the main part and the end may be different. There are sessions when the warm-up is drawn out and continues longer due to the unwillingness of the group to be involved in some topic or some movement until the therapist makes this unreadiness a topic. In other sessions, the warm-up period is shortened because many feelings are eager and ready to be expressed.

In other sessions, the warm-up period is shortened because many feelings are eager and ready to be expressed.

Termination is also very important. The work of each session must be correctly completed so that patients leave the session in a comfortable state. That is, there must be a meaningful exchange with each patient during the session, and that none of them have been left in a state of insecurity. Work and group interaction take on a natural ending. At this point, Chase goes back to creating the circle, acknowledging each individual's contribution, and ending the session with simple, repetitive, shared movements that enhance feelings of friendship, camaraderie, and well-being.

Resume

Chase has developed a theory of dance therapy practice that originates in dance movement. It was through dance that she found a way to re-establish contact with psychotic patients. Instead of relying on theoretical models that emphasize pathology, she focused on movement and health. Her deep understanding of rhythmic movement has allowed her to create a method by which to connect and ignite the life force in those who feel fearful or alienated. She was able to break the barrier of isolation and interact on an equal footing with closed, detached and disturbed people. How well she understood the power of movement in interaction with other people!

Her deep understanding of rhythmic movement has allowed her to create a method by which to connect and ignite the life force in those who feel fearful or alienated. She was able to break the barrier of isolation and interact on an equal footing with closed, detached and disturbed people. How well she understood the power of movement in interaction with other people!

Case Study

Marian Chase focused on group interaction and the resulting group dynamics that led to individual growth. Consideration of the case can be carried out from the standpoint of the development of the group as such. Such an analysis can show how the group changes its character, structure, thematic material, interaction patterns, etc. in the process of achieving therapeutic goals.

Another way to look at an interactive process is to study the individuals within that process who are part of that process. In this presentation of the case, we chose to follow the changes of one particular woman, Rosa, who participated in a dance therapy group in a small mental hospital. (This patient was referred to a group led by Sharon Chaiklin.) We will present only those aspects of the group history that will clarify how Rosa used the group in the course of her treatment. The therapeutic model is based on the concepts of Marian Chase.

(This patient was referred to a group led by Sharon Chaiklin.) We will present only those aspects of the group history that will clarify how Rosa used the group in the course of her treatment. The therapeutic model is based on the concepts of Marian Chase.

Preliminary information

Rosa voluntarily came to the hospital. She was diagnosed as a schizophrenic, chronic and undifferentiated type. Rose looked older than her age. She didn't take care of herself. She had gray hair, a motionless face, and her body was constantly tilted forward. From her history, it was known that from an early age she experienced fears and was withdrawn, aloof. She failed to successfully complete the first grade of school and eventually dropped out of school after the ninth grade at the age of sixteen. All her heterosexual relationships were unsuccessful. She was only interested in work and driving.

She was admitted to the hospital when she could no longer work as a clerk due to a disturbing thought disorder and retreat into her fantasy world. "I live in my fantasy world because reality is unpleasant." Rosa was 48 years old when she entered the hospital. She was unmarried and lived alone. She had an average IQ and functioned quite normally at that level despite her psychosis. She received a brief treatment at a government hospital 16 years ago. One factor in her re-hospitalization was her decision to stop taking her medication.

"I live in my fantasy world because reality is unpleasant." Rosa was 48 years old when she entered the hospital. She was unmarried and lived alone. She had an average IQ and functioned quite normally at that level despite her psychosis. She received a brief treatment at a government hospital 16 years ago. One factor in her re-hospitalization was her decision to stop taking her medication.

Psychological testing carried out towards the end of her hospitalization showed the following:

In the unstructured situation represented by the Rorschach tests and the Drawing of a Person, both her thinking disorder and her fixed defensive position became even more noticeable and expressed. She has considerable difficulty in interpreting reality. She exhibits a wary, avoidant and restless attitude, seeking to protect herself from her own vulnerability. The ego functions do not appear to be integrated, but she is good at hiding it. Although she cannot communicate freely, is constantly on her guard, avoids contact and withdraws into herself, she is able to "function", but the price she pays is very strong social isolation and withdrawal from human contact.

She is afraid of her fantasies and tends to repress them, thus suppressing catharsis and creative ways of expressing them. On the surface, she may seem completely devoid of the ability to fantasize, but in reality she is unwilling or unable to share them with others. This may be good for her, as her thoughts can be so vague, conflicting and confused that their expression can create even more distance between her and other people if the latter were to recognize these thoughts.

The interdisciplinary team saw the goal of treatment as helping Rosa reduce her fantasies and improve her social skills. Since her illness was of long duration and her defenses are well hidden and secured, the result may be that Rosa will be able to gain control of her psychotic thinking in order to return to work. If she could work, she would not be completely isolated and would be able to structure her life somehow again. Perhaps she could learn again to be with other people in a satisfying way.

Rosa was referred to dance therapy because she needed to develop a clearer body image and skills to interact with others. Her drug treatment was complemented by her participation in hospital-wide activities, entertainment, occupational therapy, art therapy, and occasional verbal therapy groups. The total duration of hospitalization was 13 months, after which she remained for some time in a special department, where patients live independently for some time. From the weekly discussions at the general meetings of the hospital staff, it was possible to find out how people involved in other methods of treatment perceive Rosa's behavior. This comparison makes this case quite interesting.

Rose and dance therapy

Rose began weekly dance therapy sessions five days after admission to the hospital. When she began to do this, she was still in the acute stage of psychosis: in a state of confusion and isolation. She seemed to enjoy these sessions, but she moved with minimal momentum. There were temporary manifestations of lightness and quickness in the movements of her arms and hands. During the first few sessions, she was able to focus on the movements of others and thus make adjustments to her own style. She was unable to identify or use her back muscles, her head and torso were lowered, and her range of motion was very limited. For example, she never fully extended her arms. Often she was not aware of the space around her.

There were temporary manifestations of lightness and quickness in the movements of her arms and hands. During the first few sessions, she was able to focus on the movements of others and thus make adjustments to her own style. She was unable to identify or use her back muscles, her head and torso were lowered, and her range of motion was very limited. For example, she never fully extended her arms. Often she was not aware of the space around her.

During the first sessions of Rosa, the members of the group were especially divided. We began to work on becoming more aware of the surrounding space and feeling ourselves in it. People started by pushing the air in all directions with different parts of the body, expanding their spatial boundaries. Gradually, we "broke through" the individual space and came to the feeling of a common space. The therapist suggested an exercise in which you had to push your back and shoulders through the space. Many found it difficult to distinguish between back movements and shoulder movements. Rosa was very vaguely aware of her back and the space behind her. She participated with the group in this exercise, but remained on the sidelines due to her inability to move through space towards the people around her. But she was able to straighten her body and head from a very bent position, while noting: "So I feel different, and the sensations are pleasant."

Rosa was very vaguely aware of her back and the space behind her. She participated with the group in this exercise, but remained on the sidelines due to her inability to move through space towards the people around her. But she was able to straighten her body and head from a very bent position, while noting: "So I feel different, and the sensations are pleasant."

During the first weeks, Rosa was passive and somewhat depressed, but gradually began to get involved in the work. She tried to do everything the band did. Her disturbed thought patterns seemed to be becoming more adequate. By the seventh session, she was clearly interacting with the therapist, focused, and remembered the work of previous sessions. However, space utilization remained a problem. Her body became straighter, but although she was active, her range of motion and coordination did not improve. Every week she became more and more depressed. The dance therapist's report of session 20 shows that she is "introverted, passive, calm, repetitive, hands trembling, no sense of joy, no purpose, no focus, no direction. "

"

Shortly thereafter, she became physically ill and all psychotropic medications were withdrawn. During the next two sessions, she was present in the room but did not participate. Returning to active participation, she began to show strength in her movements and began to approach others. During her twenty-sixth session, she visually fixed her gaze on something in front of her. It was, however, not clear whether she was hallucinating or not. Then, she clearly outlined her spatial field without rotating or turning her torso. Her whole body unfolded as a single whole, as if around a common axis. When the therapist commented on this limited use of space, Rose extended her arms, took the therapist's hands, and began to rock slowly. The therapist responded to this direct message by saying, "I want to see you. Can you see me?" At the same time, the word "see" was used both symbolically and literally. But can Rose see someone else and also allow others to peer into her? Rose's eyes filled with tears. This was the first emotion that Rosa showed since the beginning of the treatment. Rosa and the therapist continued to touch gently with their hands. Meanwhile, the rest of the group, realizing the importance of this moment, silently and supportively gathered around them. The rose opened, allowing the group to join hands with them, but then, almost immediately, she moved away from the group, retreating back into her space of solitude.

This was the first emotion that Rosa showed since the beginning of the treatment. Rosa and the therapist continued to touch gently with their hands. Meanwhile, the rest of the group, realizing the importance of this moment, silently and supportively gathered around them. The rose opened, allowing the group to join hands with them, but then, almost immediately, she moved away from the group, retreating back into her space of solitude.

In the next session, although she was trembling and uncomfortable, she discussed with the therapist the problem that her glasses were constantly falling off and preventing her from seeing. And whether they see each other or not has become a constant topic of discussion.

To maximize the expression of affect, the therapist asked that she continue to be off drugs. Recognizing the validity of the psychotherapist's request, the psychiatrist agreed with this. The dance therapist asked Rosa to participate in the second group of dance therapy in order to become more involved in the work. Rosa reacted positively to this proposal and was even more involved in the process in the next lesson. Her movements, despite their limitations, had reached the peak of her abilities. She began to use her lower torso, mastered the pattern of shifting body weight from one leg to the other. Her mind became organized enough to follow a fairly complex pattern and remember actions and events that had taken place in previous sessions. But it was still difficult for her to rotate her upper body. By this time, she began to make her own movements, which she often used later: turning the body, with her arms raised up. Her glasses no longer slipped, and she told the therapist, "Now we can see each other."

Rosa reacted positively to this proposal and was even more involved in the process in the next lesson. Her movements, despite their limitations, had reached the peak of her abilities. She began to use her lower torso, mastered the pattern of shifting body weight from one leg to the other. Her mind became organized enough to follow a fairly complex pattern and remember actions and events that had taken place in previous sessions. But it was still difficult for her to rotate her upper body. By this time, she began to make her own movements, which she often used later: turning the body, with her arms raised up. Her glasses no longer slipped, and she told the therapist, "Now we can see each other."

Rosa continued to actively participate. As she became more upright and used her legs and hips better, she began to feel the weight of her body as well as her own strength. The range of her movements increased, and as she began to feel the space around her, she began to use her back with more awareness and more confidence.

During the thirtieth session, the group felt uncomfortable because of the hostility of the patient, who screamed loudly and refused to participate in the work. To help the group express hostility, the therapist initiated quick, jerky movements that gradually became slower and more relaxed. The group members began to stretch and pat each other on the back, which symbolized good feelings towards each other. The therapist worked with Rosa's back, using touch to strengthen the relationship. Rosa responded quite spontaneously, kneading the therapist's back, saying that she enjoyed doing it. In the next session, the patients also gave each other back massages. It was clear that she enjoyed giving more than receiving.

A few more weeks have passed. Rosa continued to put in more energy and began to show some signs of wit. She showed more initiative in interacting with others and began to make movements in a horizontal plane, such as turning towards others. The dynamics of her movements became more diverse. At this point, she began to frequently ask to play polka music. She responded to the two-quarter rhythm, moving alone or with a partner.

At this point, she began to frequently ask to play polka music. She responded to the two-quarter rhythm, moving alone or with a partner.

Despite everything that happened in the dance therapy classes, there were no similar changes in other activities. Hospital staff, recreational assistants, and a psychiatrist all commented on her regression and non-functionality. She clearly singled out dance therapy as a place where she can develop close interaction, express feelings and connect with others.

For no apparent reason, Rosa began to clearly regress in dance therapy as well, and reached the point where she became difficult, hostile, and confused. Her thought patterns became strange again. She expressed hostility, very clearly delineating what she would and would not do. At this point, the dance therapist decided that medication might help Rosa feel more comfortable. She took medication and it helped her function with less confusion. After a month, during which there were noticeable improvements, the staff began to notice changes that previously only appeared in dance therapy. Reports indicated that she communicated more verbally, was in a good state of mind, was sympathetic to others, and showed an ability to do things for herself.

Reports indicated that she communicated more verbally, was in a good state of mind, was sympathetic to others, and showed an ability to do things for herself.

Rose was now using dance therapy in the opposite way. The sessions became a place where she could work with what she had previously struggled with: her thoughts, her sense of isolation, her distance from the group experience. She came up with a kind of ritualized walking, in her words "dance means moving the feet", which consisted of rhythmic steps back and forth at right angles to the general group. This went on for six sessions (three weeks). At this point, she was not encouraged to join the group in order to change her pattern. Instead, the therapist praised Rose for being good at her own movements. She accepted this support, and then demonstrated her "turning motions" to the group, inviting everyone to move in the same way. It was very clear that she was once again choosing dance therapy to work on "different" behaviors, and she needed support to work in her own way.

At the next class, Rosa continued to walk. When she received support, she connected hand movements. She moved in pairs with other people, but the only time she could become part of the group was when she became the center and the circle moved around her. Then she did her characteristic turns with her hands raised up. In the next session, Rose joined the group of her own accord and helped build the circle. Since then, she has done this as a full and active member of the group, while also following the general movements of the group and leading the group as a leader.

The staff began to discuss the possibility of releasing Rosa from the hospital. She had the opportunity to return to her old job. At this point, Rosa was placed in a self-care unit where she would be more responsible for caring for herself. During this period of uncertainty, the dynamics of her movements again became limited. She did not use the strength and lightness that she had shown before. She began to shrink inside herself again. During one session, the group worked on an exercise where people lean on each other in order to feel the support that everyone can give. Rosa was unable to lean on another person, nor to support anyone. Rosa looked good, but she had chaotic, shaking movements of her legs, body and arms. When asked about it, she replied that it was "rhythm waiting for the music". She dealt with this in class by structuring her involvement in the group: she made decisions about when to be active, when to rest, and when to smoke. The group that supported her behavior considered Rosa an important member of the group and were kind to her despite her remoteness. Rosa completed her dance therapy course after a year of hospitalization and returned to work after that.

During one session, the group worked on an exercise where people lean on each other in order to feel the support that everyone can give. Rosa was unable to lean on another person, nor to support anyone. Rosa looked good, but she had chaotic, shaking movements of her legs, body and arms. When asked about it, she replied that it was "rhythm waiting for the music". She dealt with this in class by structuring her involvement in the group: she made decisions about when to be active, when to rest, and when to smoke. The group that supported her behavior considered Rosa an important member of the group and were kind to her despite her remoteness. Rosa completed her dance therapy course after a year of hospitalization and returned to work after that.

Conclusion

Dance therapy was the only therapeutic method that this patient was able to use. For some reason, known only to Rosa, the movement turned out to be not dangerous, not scary for her, but a supportive therapy that allowed her to be herself, no matter what she was at different periods of time. As it changed at the level of functioning, the overall motor behavior did not change much over time. There was a certain increase in the use of space, improved coordination, rhythmic responses and the ability to move with others, which was completely new to her: "I used to always dance by myself." Close interaction and trust with the therapist was developed. Although one can rarely hope for profound changes in the case of chronic schizophrenia, this case can be considered successful. In particular, Rosa was able to rebuild herself and return to society. It would not be realistic to hope for anything more in Rosa's case. And it is quite clear that dance therapy was a very strong factor in achieving this result.

As it changed at the level of functioning, the overall motor behavior did not change much over time. There was a certain increase in the use of space, improved coordination, rhythmic responses and the ability to move with others, which was completely new to her: "I used to always dance by myself." Close interaction and trust with the therapist was developed. Although one can rarely hope for profound changes in the case of chronic schizophrenia, this case can be considered successful. In particular, Rosa was able to rebuild herself and return to society. It would not be realistic to hope for anything more in Rosa's case. And it is quite clear that dance therapy was a very strong factor in achieving this result.

The analysis illustrates the main principles of Chace. On the action level of the body, Rose was helped to master the grounded movements of the whole body, which gave her the potential for strength and confidence. Symbolic expressions were taken as direct messages; walking alone - represented the need to be alone, and the dance of "turns with raised hands" - expressed good health. The symbolic use of sight proved to be of fundamental importance in "crossing the abyss" from solitude to partnership with others.

The symbolic use of sight proved to be of fundamental importance in "crossing the abyss" from solitude to partnership with others.

Sharing her feelings with the group and with the therapist through rhythmic movements enabled Rosa to receive support, acceptance and energy to move on with her life. Although dance therapy was not the only factor that affected her during her hospitalization, it was clear that this was the step and the place where she was able to throw off her defensive position and allow herself to become visible to others.

Notes

1) Story narrated by Sharon Chaiklin.

2) The term "basic dance" was introduced to distinguish it from artificial and elaborate forms of dance that depend on physical steps and are a means of entertainment rather than communication" (Chaiklin, 1975, p. 219).

let movement into your life! NATA CARLIN

Since ancient times, people have used dance as a tool for relationships. People danced during all significant events, in their anticipation and for the glory of what happened. This happened outside the door of the woman in labor and near the deathbed. With the development of civilization, dances have become a subject of art for a person. They were given a strict place, limited by the boundaries of decency reasons for dancing. But in human nature there is a love for dance, and then dance therapy was invented.

People danced during all significant events, in their anticipation and for the glory of what happened. This happened outside the door of the woman in labor and near the deathbed. With the development of civilization, dances have become a subject of art for a person. They were given a strict place, limited by the boundaries of decency reasons for dancing. But in human nature there is a love for dance, and then dance therapy was invented.

Famous psychologists laid the foundations of this science. Among them are Freud, Adler, Jung. This science was promoted by A. Duncan, M. Wigman, Rudolf von Laban.

American dancer Marion Chase is considered to be the first dance therapist in the world. She worked in the 30s of the last century. Her work was based on strict teaching the rules of various dances. However, the woman noticed that people dance more relaxed, and give themselves up to invented movements with great enthusiasm. Their body is liberated, and a smile plays on their faces. She began to build her lessons on the combination of spontaneous dance and traditional movements.

She began to build her lessons on the combination of spontaneous dance and traditional movements.

To help emotions get out, a person must dance.

In 1966, America's first dance association was founded. In the 90s, the movement, popular by that time in the West, came to us.

Dance Movement Therapy: Theory and Practice

Dance therapy has a positive effect on people who are unable to express emotions and suffer from it. Classes with dance therapists are built both on an individual basis and in groups. For a teacher of courses, a psychological and dance education is required. The principle of working in a group is simple - those present receive a task, complete it and share their impressions with each other.

The benefits of dance therapy are triple:

Normalizes the state of health, blood circulation and physical fitness;

A person, feeling himself in a new incarnation, acquires a greater;