How much do hula dancers get paid

I quit an accounting job to be a hula dancer—here's what I learned

When I tell people I used to be a dancer the first type of dance that enters their mind is ballet. Then modern. Then jazz. Then tap. Never hula.

When I say I’ve been a hula dancer for most of my life, a lot of people ask, “Hula hooping?”

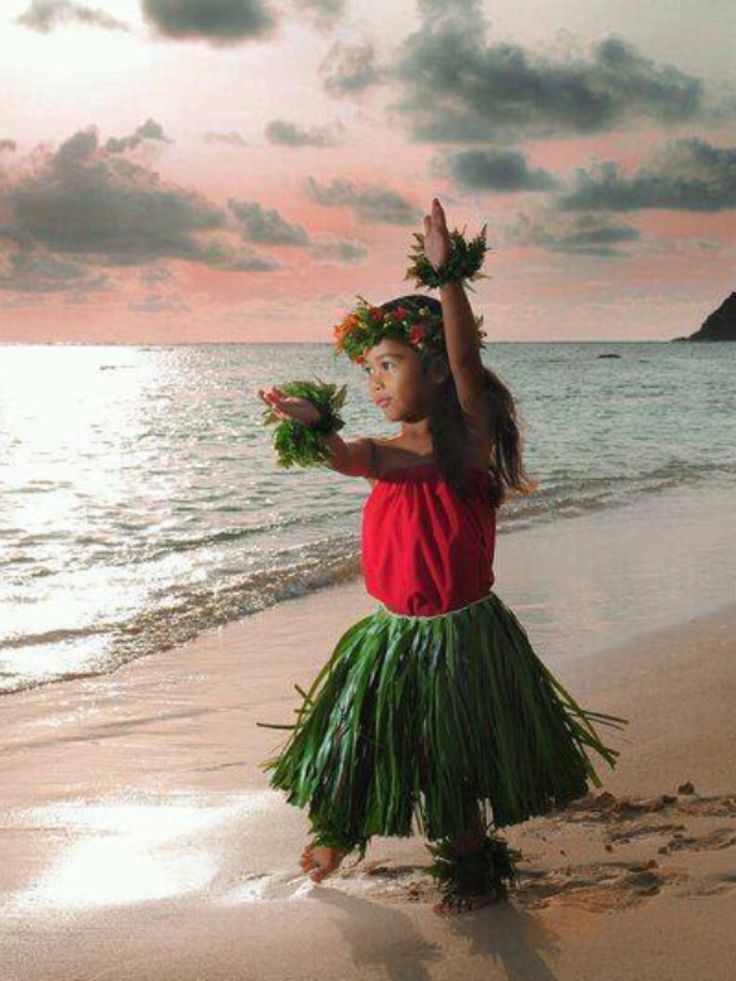

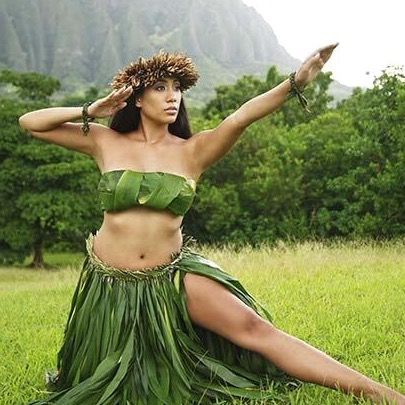

“No,” I say. “Think grass skirts and coconut bras.”

“Oh!”

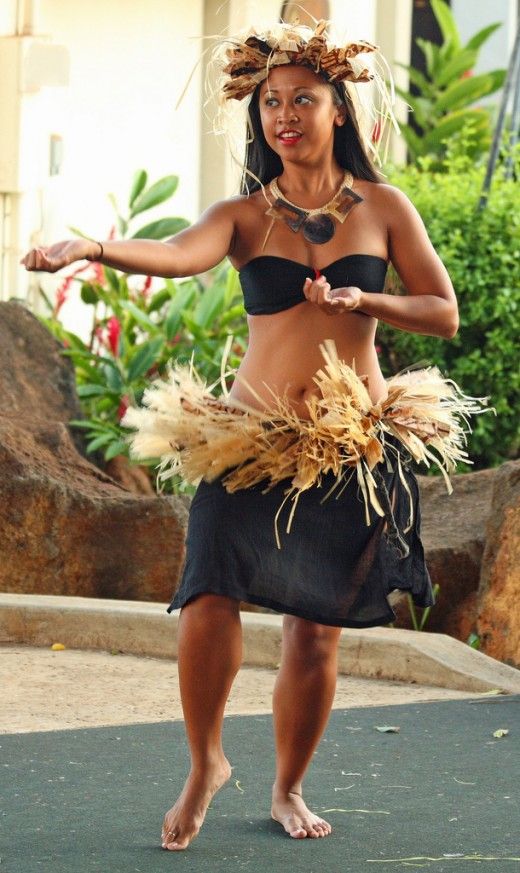

Being a professional hula dancer is an uncommon craft. I think it’s because hula isn’t traditionally a performance art. Dancers go to halaus (traditional Hawaiian hula schools) to honor a calling. While I may not be of Hawaiian blood, I honor and respect the beautiful culture this dance came from and the heritage in which it has thrived.

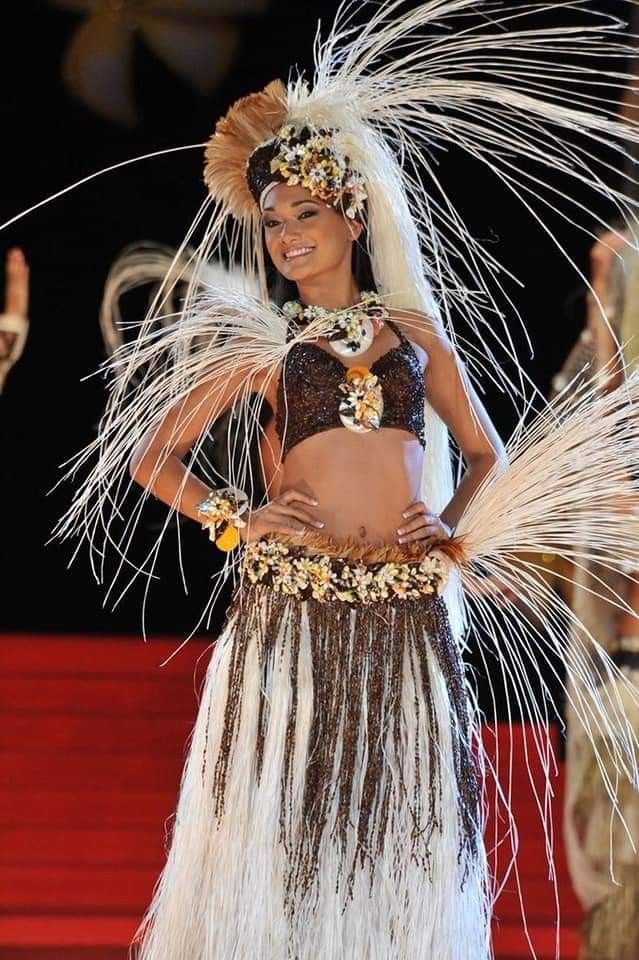

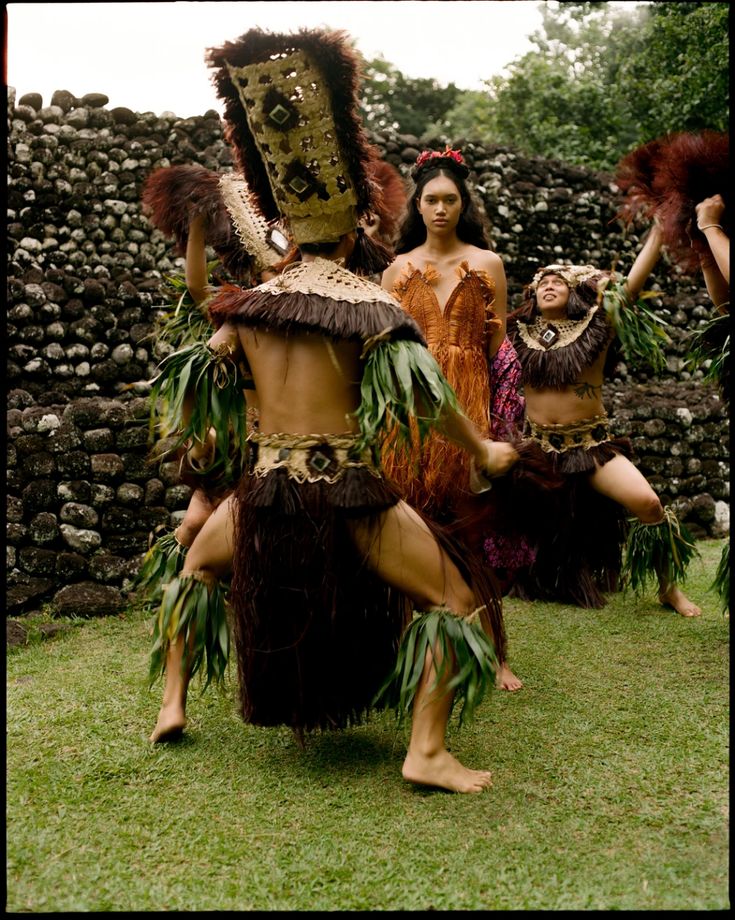

And that’s why I performed. I wanted to somehow share these indescribable emotions, these profound feelings, with others, especially those outside Hawaiian culture and small world that is hula dancing. So after years of training in a halau and dancing with various Polynesian dance groups (which typically include Hawaiian hula, Tahitian ori, and other Polynesian styles of dance), I assembled my own performance troupe with the help of my husband.

Together, we created our very own luau show. I choreographed both Hawaiian and Tahitian dances, auditioned and trained all our dancers, and my husband made all the costumes (by hand!). He also ran our production and sound and served as our resident fire breather.

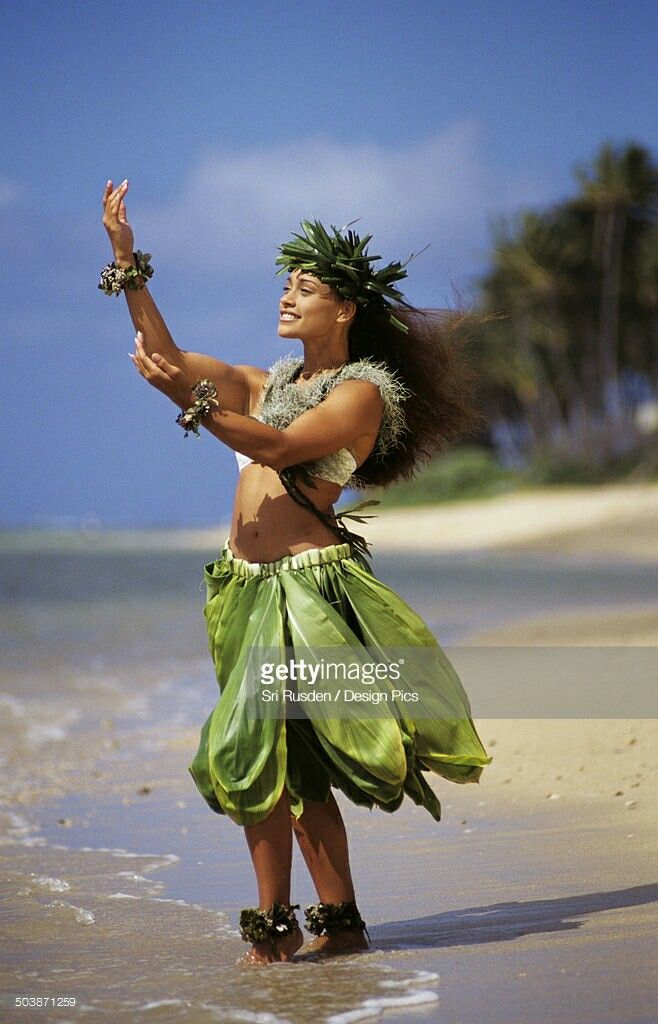

We spent two years traveling all over California, from San Diego to Santa Rosa, performing at festivals, fairs, schools, businesses, weddings, movie openings, birthday parties, and so, so much more. Here’s what I learned from those wacky, crazy days as a full-time hula dancer.

Do what you love (no matter how you look doing it)

Before starting our dance troupe I was a little apprehensive about telling my friends and colleagues. I was stepping away from an accounting career that I’d begun when I was just seventeen. I’d developed that career in San Jose, California, aka Silicon Valley, the technology capital of the world…and I wanted to go off and be a dancer for a little while. What would people think? Would it make me look flaky and irresponsible? Probably.

I did it anyway, and one of the most frequent compliments we received after a performance was “It’s clear you guys love what you do!” How was that not enough to make my day? I made a living playing dress up, listening to awesome music, and sharing something deeply meaningful to me with other people. I was even privileged enough to employ other women, other dancers, who loved it as much as I did! Who cared if I was in Silicon Valley making a living wearing fruit and foliage? I loved every minute of it, and it was absolutely worth the risk!

Sometimes, smiling more actually makes you feel better

Like cheerleaders, we hula dancers have a much-practiced perma-grin, that smile that never fades and never wavers during a performance no matter what. No. Matter. What. Not even when a cute little doggie comes nipping at your heels during a performance. Not even when the concrete you’re dancing on is so hot you end up with blisters by the end of the show. Not even when it’s 50 degrees outside and windy and you’re dancing on a ledge next to a swimming pool praying you don’t fall in…oh, and it’s raining.

When I took this lesson back to the super-focused, often cranky, high-stress corporate world I found it invaluable. Sitting all day again was a shock to my system after two years of dancing full-time. Not seeing sunlight for hours at a time was also a hard reality to accept. I tried to keep smiling even when I didn’t have to perform. And you know what? Sometimes it really worked.

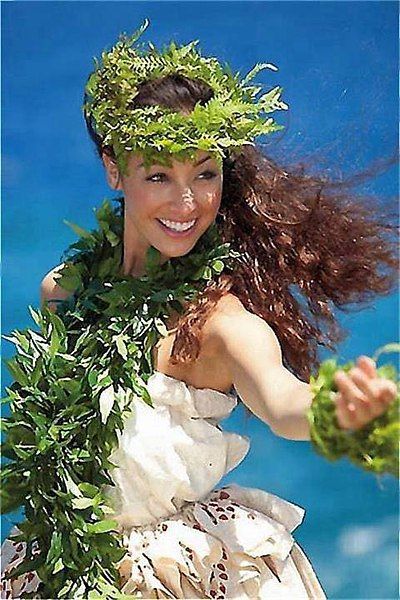

Everyone needs a little more aloha in their lives

The meaning of aloha is a bit elusive. At its most basic, it’s a word used to greet someone (Hello!) or to wish someone well when parting (Goodbye!). But, as I learned, it’s also a way of expressing love and affection toward another person. The deeper meaning is alluded to in the common phrases such as “the aloha spirit” and “the aloha way.” These simple phrases point to something much more profound. They speak to a way of living, a way of being in the world while acknowledging your connection to everyone and everything in it.

This sense of connection permeated every one of our performances. Every time I danced I felt like I was inviting the audience to share in a unique and special part of my life. Every time a show ended, I was approached by audience members eager to share their own personal stories of having been to Hawaii, or their desire to go, or their memories of a family member who loved Hawaii and would’ve truly enjoyed our performance.

These moments of connection surprised me, and the eagerness with which others longed to connect often caught me off guard…until I remembered we are social creatures always looking for connections whether we realize it or not.

I carry these experiences with me every day, and I’m so thankful I took the risk I did. The lessons I learned and moments I shared with people I may never see again still inform every day of my life.

Reese Leyva is a number cruncher by day and wordsmith by night who dreams of owning chickens and building her own natural swimming pool. She blogs about gentle parenting at www.raisingdahlia.com and posts her poetry at www.reeseleyva.com. When she’s not working or writing she’s partying with her super cool infant daughter and nifty homemaker husband. And by partying, she means napping.

She blogs about gentle parenting at www.raisingdahlia.com and posts her poetry at www.reeseleyva.com. When she’s not working or writing she’s partying with her super cool infant daughter and nifty homemaker husband. And by partying, she means napping.

[Image via iStock]

Hawaiʻi is Home for Many Musicians and Kumu Hula, but Japan Pays the Bills

For many Hawaiian musicians and singers, performing is both their passion and their livelihood.

So, when there’s not enough places to perform locally, or the pay is too low, they have to improvise. Some work day jobs and perform at night, or get creative with their repertoire and services.

Others venture to the Land of the Rising Sun, where they find more opportunities and better pay. “Hawaiian musicians have never been able to sustain ourselves as performers in Hawaii alone. We’ve always traveled. We’ve always had to travel,” says Aaron Sala, a Na Hoku Hanohano award-winning Hawaiian music artist who goes to Japan five or six times a year. He’s also the director of cultural affairs at the Royal Hawaiian Center.

He’s also the director of cultural affairs at the Royal Hawaiian Center.

Japan also has more demand for hula, providing opportunities for local kumu hula to sustain their halau by performing and teaching there.

Sala says Japan’s strong affinity for Hawaiian culture, means “Japan has become a really comfortable place for Hawaiian artists to go to.”

Video: Kumu Hula Kaui Delire expresses how the demand for hula has grown worldwide

Challenges at Home

Photo: Sean Marrs

When lehua hula Kawaikapuokalani Hewett first went to Japan in the 1980s to perform and teach workshops, he rarely saw any Hawaiian kumu or entertainers. “Today, they’re all over the fricking place,” he says. “And you know why, right? Economy. Everybody got to make money. No more jobs here in Hawaii for entertainers. And maybe get jobs, but they don’t pay well.”

Everybody got to make money. No more jobs here in Hawaii for entertainers. And maybe get jobs, but they don’t pay well.”

Over the years, the jobs available for Hawaiian music artists have declined, especially in Waikiki, where once almost every hotel had a showroom where music – not just the Hawaiian genre – could be heard. Also, fewer brick-and-mortar music stores mean fewer CDs are sold, and digital downloads and online streaming don’t pay artists as much.

Most Hawaiian music artists have nonmusic day jobs, and those that only perform are often on tour, says Pali Kaaihue, president of the Hawaii Academy of Recording Arts. The academy presents the yearly Na Hoku Hanohano awards – often called Hawaii’s Grammy Awards – and sponsors Hawaiian music and hula concerts in Japan and Hawaii.

It’s similar for some kumu. Sallie Yoza says her full-time job at Kamehameha Schools is the only way to support her family and sustain her Halau O Napualaikauikaiu, which has locations in Kalihi and Waipahu. “For me, to work is to help alleviate the cost for our families, because our families, too, cannot afford the hula,” she says. “But yet be able to bring home income on both sides.”

“For me, to work is to help alleviate the cost for our families, because our families, too, cannot afford the hula,” she says. “But yet be able to bring home income on both sides.”

In Hawaii, hula competes for young students with many other activities that interest children. That makes it hard for a kumu to build up the roster at a halau. | Photo Courtesy of Moku o Keawe

Her halau performs twice a month, and any money generated from these performances, such as at local hotels, helps pay the bills. However, some kumu say many performances are not paid. Instead, a halau may receive free food or drink, a small donation or just the opportunity to perform in return for their time and expenses.

Any performance is beneficial, even if unpaid, because it helps ensure people know the halau is available. Kumu Hokuaulani Nihipali of Halau Olapakuikalai o Hokuaulani in Kaneohe says hula now competes with other activities that kids want to do, so if students stop dancing hula, that’s lost tuition, and it makes it hard for a kumu to build up a halau.

On the Hawaiian music side, some artists say, the pay for local performances isn’t always enough to sustain them. Kaaihue estimates that a good performance fee in Hawaii is $300 to $500 for a three-hour performance, but that money must be split among all the musicians. So, many artists who perform full time are doing gigs throughout the day.

The performance fees are “not chump change,” and help people make ends meet, says Weldon Kekauoha, a Na Hoku Hanohano award-winning Hawaiian music artist. He makes a living from a lot of sources: private events, like weddings, travels to Japan once a month and regular performances at Kani Ka Pila Grille in Waikiki. He says if Japan was no longer an option, he’d probably need to do gigs at least three or four times a week to make a decent living.

“It’s a different world than it was 20 years ago,” says Matthew Kawaiola Sproat of the Na Hoku Hanohano award-winning trio Waipuna. “As recording artists, we always know that our money comes from performances and being creative with things. That’s the name of the game is being creative.”

That’s the name of the game is being creative.”

For Waipuna over the years, “being creative” has included cultural consulting, selling T-shirts, opening a music school in Japan, and playing for hula shows, adds Kahookeleholu “Kale” Hannahs.

Terminology

Three hula teacher titles are used in this story: kumu hula, loea hula, and lehua hula. Kumu means “teacher” or “source,” and is the most commonly used title for hula teachers. Loea hula and lehua hula both mean “hula master.” Kawaikapuokalani Hewett prefers the use of lehua hula for himself because that was the title gifted to him by his kumu.

The Na Hoku Hanohano award-winning trio Waipuna performs in Japan once a month. From left, David Kamakahi, Matthew Kawaiola Sproat, and Kahookeleholu “Kale” Hannahs. | Photo: Sean Marrs

A Dichotomy

Georja Skinner, chief officer of the Creative Industries Division in the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism, says artists have told her that Japan lets them pursue a career they love, and without it, they wouldn’t be able to survive as artists in Hawaii without a day job. “They’re so revered in Japan that … it’s a little bit of a dichotomy when you think about it. The majority of revenue made indeed comes from their gigging and their performances and their teaching in Japan.”

“They’re so revered in Japan that … it’s a little bit of a dichotomy when you think about it. The majority of revenue made indeed comes from their gigging and their performances and their teaching in Japan.”

The demand for their music has increased so much in Japan, says Leah Bernstein, president emeritus of Mountain Apple Co., that artists are no longer traveling there just in the summer, as in the 1980s. Now, they’re going throughout the year.

And why not? They’re treated like rock stars, says Kaaihue, who is also a musician and performs in Japan several times a year. “From a musician’s standpoint, the audiences are so focused and enamored and overjoyed when you’re performing, when you’re there. And from the business standpoint, obviously, they buy the tickets, they purchase the CDs,” he says.

“And I don’t think it’s any secret when I say as far as the performance fee that an artist would get in Japan versus what they get here is night and day. It’s night and day.”

Part of that support comes from Japan’s higher ticket prices, says Eric Takahata, managing director of Hawaii Tourism Japan, Hawaii Tourism Authority’s partner for marketing in Japan. Sometimes, tickets cost hundreds of dollars, he says, compared to the less-than-$40 ticket price typically found in Hawaii.

Sometimes, tickets cost hundreds of dollars, he says, compared to the less-than-$40 ticket price typically found in Hawaii.

“The Japanese will pay them top dollar and treat them with a little bit more reverence. … So the musicians who are going there know that that’s viable for them … and of course they’re going to go,” says Jerry Santos of the Na Hoku Hanohano award-winning group Olomana. “If somebody’s going to wave a lot of money in your face and say, ‘Come over here and I’ll treat you like a king,’ you’d be kind of a fool not to do it.”

He admits he’s concerned that there appears to be a stereotype of Hawaiian music and hula that Japanese audiences want to see. Often, it’s the winners of the Na Hoku Hanohano Awards and Merrie Monarch Festival who are invited to perform and teach in Japan, he says. “Hawaii has so much more than that. So, while I am happy for the ones that have the great opportunity, I almost wish that everybody would have the same opportunities across the board,” he says.

Kumu Kaui Dalire has halau in Kaneohe, Japan, Australia, Mexico, and on the Mainland. She says each overseas halau is led by an instructor, and she visits each location two or three times a year. | Photo: Sean Marrs

Keeping the Culture Alive

Hewett credits loea hula and Merrie Monarch co-founder George Naope with opening the door for Hawaii kumu who are in Japan today. Kumu have been establishing branches of their halau in Japan for the past 10 to 20 years, often to help sustain themselves at home. Before opening six branches of her halau in Japan and one in Korea, Nihipali used her production company – which coordinates Hawaiian entertainment for overseas events – to financially sustain her Kaneohe halau. When those overseas branches opened, they took over that financial support, so she says, it would be very challenging to keep her Kaneohe halau running without them.

Nihipali travels to each of her Japan branches at least once a month and says tuition for hula classes can be, on average, 20 percent higher than in Hawaii, though she has different tuition rates for different Japanese cities, depending on the cost of living.

But the main thing is not the money, she emphasizes. “We all need to make a living. And we all need to get ahead. … But I’m very fortunate to have a strong hula base now with my Kaneohe haumana here and then also with my Japan students.

“We are grateful to the Japanese for keeping a lot of us in business and keeping our culture alive,” she adds.

The financial success of halau in Japan can be attributed to the higher numbers of Japanese students – it’s often said Japan has more hula dancers than Hawaii – and their willingness to pay higher tuition. Takahata says this willingness stems from the value Japanese students place on getting an education, and that value is increased if the Japan halau is associated with a kumu from Hawaii – such as having a Japanese sensei being taught or guided by a kumu, or a kumu directly overseeing the halau.

“(There are) many hula students in Japan, it’s a phenomenal ongoing business that they run there,” says kumu Ainsley Halemanu of Hula Halau Ka Liko O Ka Palai. “… So the prosperity opens up to our local teachers. So all the big names jump on the bandwagon.”

“… So the prosperity opens up to our local teachers. So all the big names jump on the bandwagon.”

Preserving Traditions

Many kumu agree there are more hula dancers in Japan than Hawaii. Over the years, hula has been taught in Japan in community centers, universities and halau. Eric Takahata of Hawaii Tourism Japan has heard that Japan has about two million hula dancers, compared to his estimate of less than 50,000 across Hawaii. There’s no official count of Hawaii dancers – even the Merrie Monarch Festival doesn’t keep track, says judge Ainsley Halemanu – but other people estimate that Hawaii has 8,000 to 20,000 hula dancers.

Some Hawaii kumu began teaching in Japan because they were concerned that people who didn’t have hula training were opening schools and calling themselves kumu. That’s why Kumu Kaui Dalire launched ikumuhula.com in April to offer hula classes online. She says she felt a responsibility to make sure the traditions of hula and Hawaiian culture were passed on properly.

She also has halau in Kaneohe, Japan, Australia, Mexico and on the Mainland. She says many kumu struggled with whether to start teaching outside Hawaii because they feared they were selling out the Hawaiian culture. “I truly believe 100 percent that we’ve been given this talent for a reason,” she says. “We shouldn’t be made ashamed to be able to capitalize on it in a way that sustains our families, because to live in Hawaii, it’s really hard. It’s expensive. I mean it’s a struggle for survival and for me, I’m just happy that I’m able to do what I love doing and still be able to provide for my five boys as a single parent.”

Maelia Loebenstein Carter, kumu hula of Ka Pā Hula o Kauanoe o Waahila, was one of those kumu who originally struggled with the idea of teaching in Japan. She now has 600 or 700 students across her nine Japanese halau branches, but she says it’s not a business venture – it’s about being a presence of traditional hula. “I always knew that when my day of reckoning came, I would be able to face my ancestors and know that I didn’t sell out our culture. I didn’t sell out for a dime,” she says.

I didn’t sell out for a dime,” she says.

Kuuipo Kumukahi, immediate past president of the Hawaii Academy of Recording Arts, says she doesn’t fault kumu if they have to go abroad to make a living, though she thinks they have sold Hawaii.

She acknowledges that Hawaiian kumu are teaching Japanese people to be good stewards of hula and its traditions. But, if the kumu or their Japanese partners are simply in it to make money, “Forget the olelo Hawaii, forget that they’re wearing the leis … you’ve sold it. And so kumu hula have to be responsible,” for what they’re sharing in Japan.

The musicians, on the other hand, just play the music, not teach, she adds. But they have to decide whether they’re OK with being commodities: “So the idea of becoming a commoditized Hawaiian musician … it’s, ‘Can you sleep with that, are you OK with that?’ ” she asks.

Nā Hoku Hanohano award-winning Hawaiian music artist Weldon Kekauoha. | Photo: Sean Marrs

Local Commitments

Some venues in Hawaii still commit to providing Hawaiian music and hula performances today. One is the Kuhio Beach Hula Show that has been running for over 20 years in Waikiki. Another is Mele Mei, an annual celebration of Hawaii’s music, hula and culture. According to co-creator Pali Kaaihue, the event was started in part to show the venues that didn’t have live Hawaiian music that they needed to step up their game.

One is the Kuhio Beach Hula Show that has been running for over 20 years in Waikiki. Another is Mele Mei, an annual celebration of Hawaii’s music, hula and culture. According to co-creator Pali Kaaihue, the event was started in part to show the venues that didn’t have live Hawaiian music that they needed to step up their game.

The Hilton Hawaiian Village in Waikiki was one of the first hotels to jump on board with Mele Mei, says Lora Gallagher, regional marketing director for Hilton Hawaii. She says its longstanding commitment to Hawaiian music is evident today at Hilton Hawaiian Village’s Tropics Bar & Grill and Tapa Bar. “It’s just part of our DNA, I guess. We know we need to have it. It’s good for our business and it’s good for people. Like I said, I think the visitors expect it,” she says.

There are also places like Kani Ka Pila Grille at the Outrigger Reef Waikiki Beach Resort and the Royal Hawaiian Center. The grille works with over 30 musicians who predominantly play traditional Hawaiian music every night. Luana Maitland, director of cultural programs, says her challenge is not having enough days of the week to have all the musicians play. The Royal Hawaiian Center has long held regular hula and Hawaiian music performances, and Aaron Sala, director of cultural affairs, says: “There will never be an intent on our part to stop that in any way. If anything, we’re looking to increase it.”

Luana Maitland, director of cultural programs, says her challenge is not having enough days of the week to have all the musicians play. The Royal Hawaiian Center has long held regular hula and Hawaiian music performances, and Aaron Sala, director of cultural affairs, says: “There will never be an intent on our part to stop that in any way. If anything, we’re looking to increase it.”

There’s also support for musicians from the state government’s Creative Lab Hawaii Music Immersive Program, which helps artists – not just Hawaiian musicians – find new markets and revenue in music for film or TV projects. The five-day program pairs selected artists with mentors to help them write music for these projects, says Tracie Young, an economic development specialist with the Creative Industries Division.

Kumu Sallie Yoza of Halau O Napualaikauikaiu. | Photo: Sean Marrs

“Dime a Dozen”

Part of the problem with being able to make a living in Hawaii, some say, is that Hawaiian music and hula are taken for granted. “In Hawaii, we’re a dime a dozen. All the times (Waipuna gets) calls for baby luau, we get, ‘Oh how come you guys cost so much?’ That’s our value,” says Waipuna’s Kahookeleholu “Kale” Hannahs. “And then, ‘I’m just going to get my uncle fo play,’ you know? ‘My uncle can play and all I got to give him is his beer.’ And that’s the truth about Hawaii. And that’s why with supply and demand, there is value for us anywhere outside of Hawaii.”

“In Hawaii, we’re a dime a dozen. All the times (Waipuna gets) calls for baby luau, we get, ‘Oh how come you guys cost so much?’ That’s our value,” says Waipuna’s Kahookeleholu “Kale” Hannahs. “And then, ‘I’m just going to get my uncle fo play,’ you know? ‘My uncle can play and all I got to give him is his beer.’ And that’s the truth about Hawaii. And that’s why with supply and demand, there is value for us anywhere outside of Hawaii.”

Kuhao Zane agrees with Hannahs. “It’s just that here we have a culture of like, ‘Oh yeah, you can get free Hawaiian music along with your meal. Come to a sunset dinner,’ ” says Zane, who is a dancer from Halau o Kekuhi on Hawaii Island, which performs in Hawaii and Japan to fundraise for the Edith Kanakaole Foundation.

Artists should be able to make a living by performing and teaching just in Hawaii, says Kuuipo Kumukahi, immediate past president of the Hawaii Academy of Recording Arts. But that would only happen if Hawaii’s financial support of Hawaiian music and hula was as much as Japan’s. “But it’s not,” she says. “Now that’s shameful.”

She used to travel to Japan every six months to perform. “It’s tiring,” she says. “And you cannot do that forever.” She wishes there was more demand for hula performances and lessons beyond Merrie Monarch.

Despite the challenges, some Hawaiian music artists have made it work at home. When musical venues around Waikiki started disappearing in the 1990s, says Jerry Santos of Olomana, he adapted by moving from one type of venue to another and diversifying his repertoire. He’s performed four or five nights a week for the past 40 years.

“It is possible to make a living at home,” he says. “I can play on a concert stage because I know how to do that. I’ve played with the symphony because I’ve had that experience. But at the same time, if there’s no big shows this weekend, and if I don’t have the opportunity to do that, I can still go play in nightclubs because I have more than enough music to do that.”

DWTS Salary: How much do celebrities and professional dancers get paid to dance with the stars?

'Dancing With the Stars' One of the longest running and most popular reality shows in the US. Since its debut in 2005, the show has been gaining momentum. Even today in 2020, Dancing with the Stars remains hugely popular, and it's likely that it's still many years away.

Since its debut in 2005, the show has been gaining momentum. Even today in 2020, Dancing with the Stars remains hugely popular, and it's likely that it's still many years away.

Fans of the show need no introduction, but for those of you unfamiliar with its format, Dancing with the Stars pairs a celebrity with a professional dancer and sees several such teams compete in pre-determined dance performances to win over audiences. . judges and the public. The couple that receives the fewest points from the judges and the fewest votes from the audience are eliminated from the tournament every week until only one couple remains and becomes the champion.

Dancing with the Stars has over the years seen celebrities such as Floyd Mayweather, Kim Kardashian, Denise Richards, Buzz Aldrin, Pamela Anderson, Zendaya and Bill Nye take part. Because getting boxing legends, scientists, and actors to compete in the dance competition is no easy task, many fans have asked how much the show pays. If you're wondering how much celebrities and dancers earn by participating in the competition, we've got you covered.

If you're wondering how much celebrities and dancers earn by participating in the competition, we've got you covered.

How much do celebrity members earn?

Dancing with the Stars has been around since 2005, so it's important to note that payouts have changed over the 15 years of existence. Therefore, we will focus on more recent figures; according to Variety According to a 2019 report, celebrities who participate in the show earn $125,000 per person for the rehearsal period and the first two weeks of performance. As the show goes on and contestants drop out, the payouts keep going up for every contestant that stays.

However, it's important to note that as of 2019, the maximum amount a celebrity could take home was $295,000. All three finalists take home the full $295,000 - the winning couple's star member doesn't take home any extra money, but does win the Mirror Ball Trophy and earn bragging rights.

It should also be noted here that the maximum potential payout used to be higher at around $350,000 each for the three finalists. However, in 2019year it was revised and shortened due to budgetary problems. Hence, it also makes sense to assume that celebrities may have to receive lower payouts in season 29 as well, because the world is in the midst of a global pandemic and economic crisis.

How much do professional dancers earn?

While celebrities can certainly earn a lot by participating in Dancing with the Stars, their competitiveness is ensured by professional dancers who work with them in pairs. However, these pros don't earn as much as their celebrity counterparts, although it's fair to say that they still take home a lot of money after every season.

As of 2019, professional dancers can earn up to $100,000 per season (including rehearsal time) for appearing on shows and helping their celebrities reach the top of the competition. While this is significantly less than the $295,000 celebrity income limit, it's still a huge amount of money. That being said, it should be noted that the pros' actual payouts per episode are not in the public domain, and what we know about their season earnings comes from secondary sources such as reports and interviews.

While this is significantly less than the $295,000 celebrity income limit, it's still a huge amount of money. That being said, it should be noted that the pros' actual payouts per episode are not in the public domain, and what we know about their season earnings comes from secondary sources such as reports and interviews.

Hawaiian Hula Dance: Aloha Studio

We can't talk about hula without talking about the places it was inspired by - like Pune (Bol. Hawaii). There, Hiyaka (Pele's sister) sang the dancing hala groves, where "Puna herself dances in the wind." A dance about how friends Pele and Hiyaki danced here, which is one of the earliest references to the hula. Today, this Hiyaka chant still resounds:

Puna dances in the wind

Kea'au Hala Grove of Dance

Hōpoe dance in Hā'ena -

Woman dancing

Her hips spinning by the sea of Nanahuki,

Dancing with merriment

By the sea of Nanahuki,

Pune, the thundering sea.

The sound of the sea strikes the ear here

Lehua flowers everywhere

Look towards the sea at Hōpoe,

at the Woman whose hips are turning by the sea

One of the first - and perhaps the first school for teaching hula was established by Kapo in Kan, Molokai .

Who is dancing the hula?

Although it is firmly believed that only men danced the hula in antiquity, stories survive of men and women, children and elders dancing the hula. When King Kalani'puu announced hula on the island of Hawaii in the late 1700s, the only people who didn't expect it were babies - it was natural to introduce children into the world of hula even before they could walk (!)

And by the way, Kalani'puu himself was still dancing at 80!

Hallau is not only "hula school"

When you hear "halau", you automatically think "hoola".

But although " Hālau hula " are hula schools, the word "halau" itself literally refers to the longhouse or congregation house. For example, a canoe is stored in hālau wa'a .

For example, a canoe is stored in hālau wa'a .

Halau hula is more than "dance school" in the Western sense.

Hula students need to know a lot more than just dance techniques and the dance itself.

Learning and singing " ōlelo Hawai'i " (in Hawaiian) is an excellent basis for understanding mele.

Knowledge of Hawaiian history is also very important.

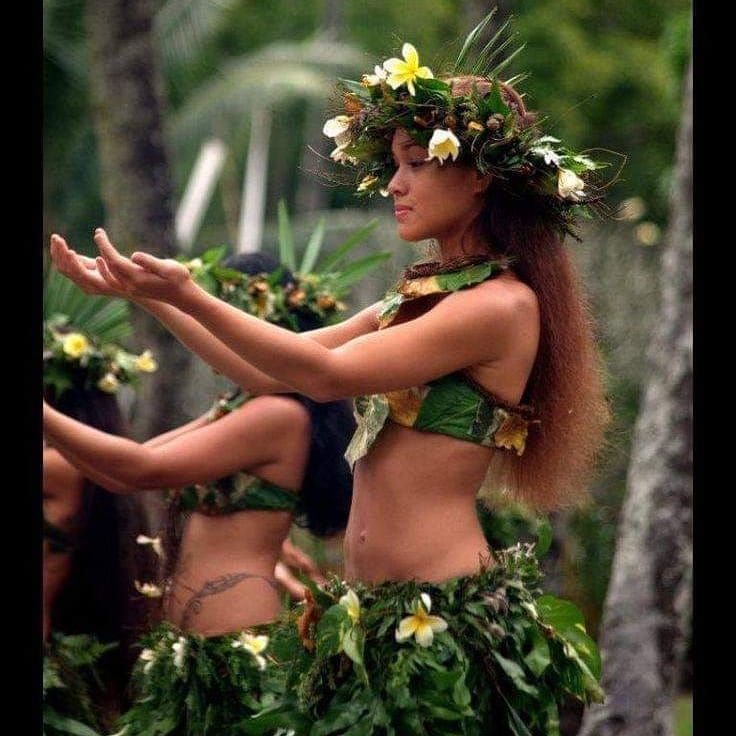

And in the tradition also the study of the creation of costumes and decorations for performances, all variants of execution (from flowers, kukui nuts, etc.), and the creation of them by the students for themselves each and every time.

Hallau can also act as a performance venue: performances bring our stories to life and keep them in the hearts of the Hawaiian people. Sometimes these stories live only through mele hula and nowhere else. In this way, hālau hula helps perpetuate our traditions.

As for mele for dancing, is mele for describing all kinds of situations and expressing all sorts of feelings - and Hula gives extra depth to all of them.

School rules

There used to be many kapu (taboos) in hula training, for example:

- certain foods such as limu seaweed and squid were forbidden to eat (because their names suggest hiding (pe'e) and fleeing (he'e) from knowledge hula),

- hair and nails were forbidden to cut and shave, because these actions involve cutting off knowledge,

- and it was very important to keep yourself clean (so don't miss a swim and please put on a fresh set of clothes before class!)

In addition, students may not share their food with anyone other than members of their halau.

You can't talk to kumu (you can only listen).

One cannot criticize the path of other halau....

By following the kapu, the dancers will be blessed by the hula gods, keeping knowledge pure and cultivating in hula.

The most sacred place in the halau was the place where the kuahu, or altar . Kuahu is dedicated to Laka and other akua (gods) hula, and their kinolau (special offerings) are placed on it.

Kuahu is dedicated to Laka and other akua (gods) hula, and their kinolau (special offerings) are placed on it.

If the kapu were not disturbed and the hula training went well, the kinolaus on kuahu remained green and fresh - maile, ʻieʻie, halapepe, ʻōhiʻa lehua, and palapalai did not fade.

The presence of akua on kuahu will inspire and bless the dancers.

Today, some halau follow the traditional kapu. Other halau combine traditional teachings with their own rules. The prayers and even the movements of the arms and legs are not all the same among the different halau. Therefore, it is important to remember:

“ʻAʻohe pau ka ʻike i ka hālau hoʻokahi” - not all knowledge is studied in one school.

What is kinolau and what are they like

The Hawaiian akua gods can take on more than one form (animals, plants), which is why their forms are called "kinolau" - many bodies.

Here are some of the kinolau of some of the akua hula that are traditionally placed on kuahu:

1. maile - kinolau of Lucky and the four maile sisters: Mailekhi'vile, Mailekalueya, Mailelauli, Mailepakakha

2. 'IE'I -Kinolau of lauka'ie

3. Halape -Kinolau from Kapo

4. ōhi'a lehua -kinolau laka and kūka'ahi'alka 9000 9000 9000 9000 5. Palapalai -kinolau Hiyaki

6. Piece of lima wood -kinolau Laka; symbol of enlightenment

Other akuis of the area and "hamakua" people in halau can also pray and ask to come and inspire.

Position and titles

There are different positions and titles in the traditional hula world. Different halau may have different definitions and kuleana for these roles. They include the following:

- 'ōlohe - the highest rank, even higher than kumu; usually an older, more mature person with a higher skill level

- kumu - teacher, leader, conductor

- po'opua'a - a person responsible for placing plants on kuahu, addressing questions-requests to the godfather on behalf of the students and responsible for carrying out the orders of the godfather

- paepae - helper po'opua'a

- ho'oulu - one who keeps the atmosphere and hall clean, who fills a bowl of kuah with fresh kava

- ho'opa'a - drummer and singer; ho'opa'a remembers mele and pule (prayers)

- ' ōlapa - dancers

More than two hula styles

Today, hula styles are often divided into kahiko and 'auana.

The word kahiko means old, so hula kahiko refers to ancient hula.

The word ' auana means to wander, and the hula 'auana is a modern hula in which the dance "wanders the tradition".

But there are other styles of hula, for example:

- hula pahu (sacred pahu or drum dance),

- ʻai haʻa (high-energy low-stance dance) ...

//and that's not all! I know for sure that there is a special style of humorous hula, for example.../

Garbage Collection

Hula students often go to the forests to gather plants for performances and special occasions.

If hula students are on their way to pick ferns or flowers and you ask them what they are doing, they can simply say: “I ka ʻohi ʻōpala” (I’m going to pick up trash).

This form of response probably appeared as a means of avoiding an unfortunate outcome (for example, not finding suitable plants or getting into bad weather).

This tradition is similar to the practice of Hawaiian fishermen who say they are going "holoholo" rather than fishing (hukilau).

Before a student of hula enters the forest of Laki, a prayer is chanted mele kāhea for permission to enter. The answer is the signs of nature, indicating the acceptance or denial of the request.

A similar chant is used to ask permission to enter the halau hula, which is also considered a sacred place. If the request is approved, the kumu will reply mele komo (singing the permissive phrase). It is curious that in some halau these two meles are used in reverse (swap).

If permission is not granted immediately, the student repeats his mele until permission is granted.

Entrance to the sacred space requires being "makaukau" or ready.

What does kumu hula ask the group before each training session by singing:

- Ho'omakaukau?

And the students in chorus should answer "Ae" - yes.

When you are macaw you are calm, focused and free from any negative thoughts or energy. As a Macau, you are ready to receive teachings and gifts.

As a Macau, you are ready to receive teachings and gifts.

With teachings and gifts comes responsibility, or kuleana .

These are all indispensable parts of training in halau hula.

Hula as a profession

The hula dancers in Waikiki were not the first to make a living from hula dancing. Traditionally, the best hula dancers were at the court of the chiefs (aliyah). Their food and livelihood were provided.

Some hula dancers made a living moving from place to place and performing for spectators (the most famous of them is the Ariori clan, peace dancers).

Celebrations and other events may require hula. The biggest occasion for hula was at the birth of a high chief. The death of the paramount chief will also be an occasion for hula, in which the songs and dances written for that ali'i will be sung.

Also, in some communities it was customary to dance hula in honor of special guests.

Hawaii without hula?

It's hard to imagine Hawaii without hula. However, there was a time when blasphemy was forbidden. Among the laws prohibiting murder, robbery and other heinous acts was the prohibition of public blasphemy .

However, there was a time when blasphemy was forbidden. Among the laws prohibiting murder, robbery and other heinous acts was the prohibition of public blasphemy .

Hula was seen as a pagan practice in the eyes of Protestant missionaries.

When Queen Kaahumanu converted to Christianity, she proclaimed in 1830 along with a law encouraging her people to follow the Word of God, a ban on blasphemy in public places. Letters to local newspapers denounced the practice of hula.

In 1851, a law was passed requiring a license to speak in public. And a few years later, a license that cost $10 per performance only allowed hula performances in Honolulu and Lahaina, and not in any other public place.

But halau hula still worked, albeit in secret, on all the islands.

And only during the reign of David Kalakaua (at the very end of the 19th century) hula gained a second wind after 50 years of persecution. Thanks to his support and love for hula, hula again entered the mainstream of Hawaiian values openly distributed on the islands.