How to ethiopian dance

The Renaissance of Traditional Dance? – Ethiopian Business Review

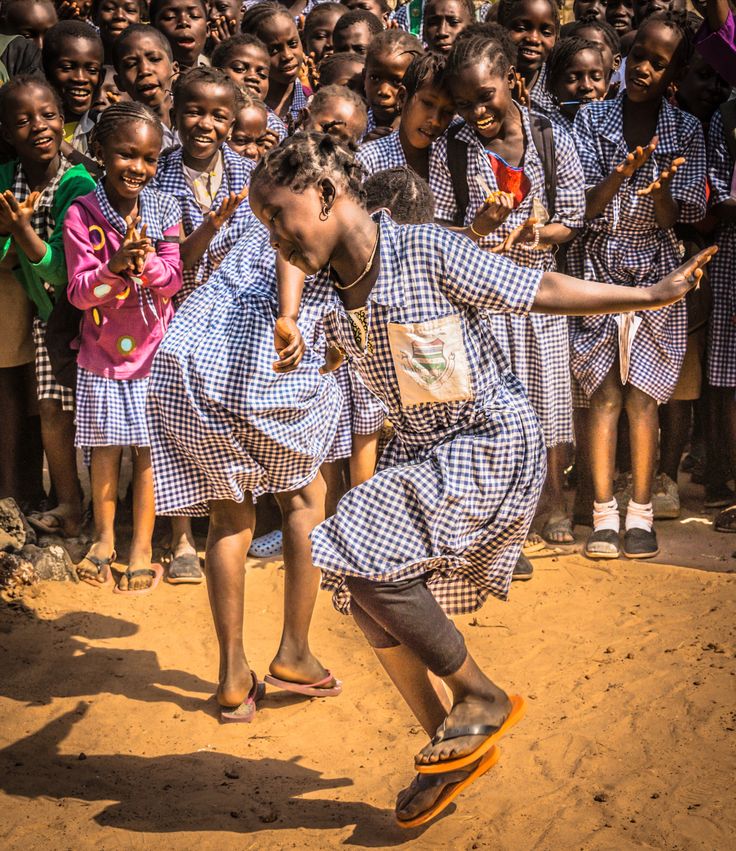

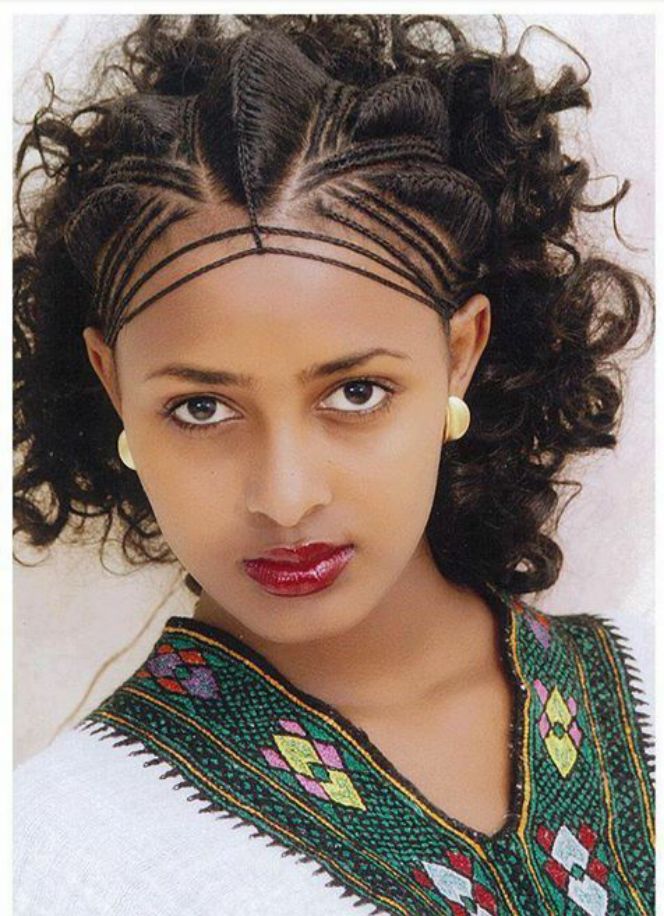

In Ethiopia, traditional dances used to celebrate festivals, weddings, and occasions of every kind. With more than 80 traditional dances from all the corners of the country, one of the most widely known forms of Ethiopian traditional dance, known as eskista, has been experiencing some ups and downs in the past few years. However, eskista along with other traditional dances are making their way to global audiences currently. Even some people in Europe and America are learning Ethiopian traditional dances on their own. EBR’s Menna Asrat looks at where Ethiopian traditional dance is today and what the future may hold for the art form.

Traditional dancing has been part of everyday life in Ethiopia. Although it existed for centuries traditional dance has not made the transition to a respected art form for so long. In the past, theatres in Ethiopia even hosted regular shows dedicated solely to showcasing traditional dancing from different parts of the country. However, in the past two decades, the places where traditional dance could be showcased on a national and international level have decreased. After the shows at the country’s theatres dwindled and eventually stopped, and formalised traditional dance has all but become a thing of the past.

But now, younger dancers and the ubiquity of social media are starting to make people more aware of the art, which in turn, encouraging folks to try and revive its popularity. In fact, traditional dance currently is becoming a fixture in restaurants and bars, as well as music videos with a group of dancers performing eskista, a catch-all term for a dance from many parts of the country that focus on intense shoulder and chest movements, sometimes described as resembling the movement of a snake’s tail.

Meron Tsegaye has been dancing for the last 20 years. She started teaching traditional dance about five years ago, and she has seen a resurgence I popularity in classes, but not for those trying to become professionals. “In the last few years, I have seen some older people becoming more interested in learning traditional dance,” she told EBR. “But I still haven’t seen as much of an increase in the public perception of traditional dance as a profession.”

“In the last few years, I have seen some older people becoming more interested in learning traditional dance,” she told EBR. “But I still haven’t seen as much of an increase in the public perception of traditional dance as a profession.”

Among the more than 80 or more types of traditional dances (termed wuziwaze in Amharic) existed in Ethiopia, eskista is one of the most well-known especially in northern part of the country particularly in the state of Amhara. One of those eskista dancers is Biruk Melesse. The 24-year-old started dancing with his friends after being inspired by broadcasts of the old shows in the country’s theatres. “I got interested when I was a child,” he told EBR. “I got together with a group of my friends and we began to teach ourselves to dance. Sometimes we got pointers from older relatives or other kids in the neighbourhood.”

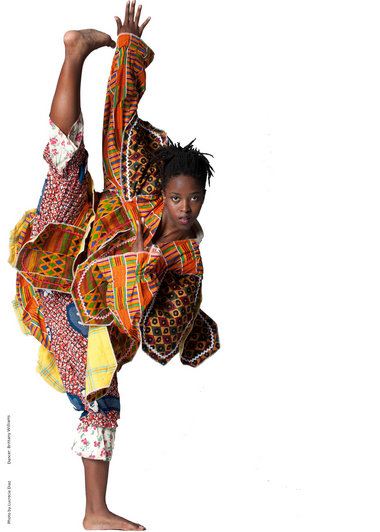

There are even those who used the art form to move into other areas of dance. Medina Hussen, in an interview with EBR in May 2018, explained how traditional dance had started what would become a lifelong love affair and career path for her. Medina is one of the few dancers who work in spite of her physical disabilities. Even though she now works in contemporary dance, eskista opened doors for her. “I started out with a group of traditional dancers,” she says. “That was what sparked my passion.”

Medina is one of the few dancers who work in spite of her physical disabilities. Even though she now works in contemporary dance, eskista opened doors for her. “I started out with a group of traditional dancers,” she says. “That was what sparked my passion.”

Traditional dance is also used as a selling point to attract tourists to Ethiopia from all around the world. However, some of those in the industry feel that attracting tourists has been placed above professionally developing dancers.

Melesew Menberu, a traditional dancer and teacher has been dancing since he was 17. The 38-year-old feels that even though venues understand the business value of traditional dancing, they don’t pay much attention beyond that, leading to small salaries, a lack of teachers and a long term impact on the industry.

“This is more than a profession,” he said. “The young dancers in the industry could have reached great places by now. Once you get into this industry and start to love the people and the art, there’s no going back. But the dancers in the restaurants and bars only make around ETB2000 on average.”

But the dancers in the restaurants and bars only make around ETB2000 on average.”

Melaku Belay, a seasoned veteran of the Ethiopian traditional dance scene, has worked in shows in Addis, and all around the world. As a dancer who has performed with stars like Mehamud Ahmed, and others, Melaku founded a dance and music group called Fendika, and operates a venue by the same name in Addis Ababa. In the time that he has been working, he has seen people come and go in the industry, and has had a front row seat to the changes in how people perceive traditional dance.

“In the past, traditional dance was not considered an art form,” he told EBR. “With the changing times, it seems as if it doesn’t have more respect than it used to have, but is becoming more monetized.”

Traditional dance seems to be facing many hurdles. Customarily, in many African cultures, and Ethiopia as well, artistic jobs like dance have been misunderstood, if not outright rejected. It is in that environment that Melaku has been operating. “The problem lies with the way traditional dance is perceived, not just by the general public, but by the government,” he argues. “There isn’t a governmental protection for traditional dance. There are few concrete researches conducted on traditional dance.”

“The problem lies with the way traditional dance is perceived, not just by the general public, but by the government,” he argues. “There isn’t a governmental protection for traditional dance. There are few concrete researches conducted on traditional dance.”

The people in charge of the country’s cultural and historical profiles agree. Nebiyou Baye, former head of the National Theatre, and the current head of the Addis Ababa Culture and Tourism Office, takes the same stance as Melaku. “Right now, if you want to see Ethiopian culture and dancing and singing, you have to wait until night, and go to a bar or restaurant,” Nebiyou said in an interview with EBR in July 2018. “There are no refined, national-level culture displays in Ethiopia. Cultural nights are private initiatives, and you can’t be sure of what you’ll see. It’s such a sad thing that Ethiopian culture is associated with going out and drinking at bars.”

Melaku agrees. “It does tend to cheapen it when you trade on your culture,” he says. “The fact that this art is not regulated and protected by the government exposes it to misuse. People just up and go to other countries in the name of doing a traditional dance show. But they are exposed to being trafficked and mistreated abroad. Even in Addis, the women who work in the various bars as dancers are mistreated.”

“The fact that this art is not regulated and protected by the government exposes it to misuse. People just up and go to other countries in the name of doing a traditional dance show. But they are exposed to being trafficked and mistreated abroad. Even in Addis, the women who work in the various bars as dancers are mistreated.”

With such a complex problem facing traditional dancers, it seems like there is a long road ahead for those who love the art form. Until a lasting solution is found however, Melaku says, something is better than nothing. “It isn’t ideal to have our culture represented only in bars and restaurants. But it is better than letting it die out completely.”

Meron agrees. “There should be an official body that studies and preserves traditional dances. There are over 80 ethnic groups. Their dances should be studied, and classified into what is reserved for weddings, or funerals or festivals. We’ve not come as far as we should have with dance.”

6th Year • Sep. 16 – Oct. 15 2018 • No. 66

16 – Oct. 15 2018 • No. 66

Vision & History — Ethiopian Dance Art Association

Led by the most prominent dance artists in Ethiopia, Ethiopian Dance Art Association is poised to represent Ethiopian dance globally and to become conduits of national and international exchange.

Ethiopian Dance Art Association’s goals are:to support the development of dancers in Ethiopia and protect their rights as professionals,

to conduct and disseminate research about the rich dance heritage of Ethiopia,

to facilitate collaboration among Ethiopian dancers, as well as exchange between Ethiopian dancers and artists/organizations around the world.

Historically, movement has always been part of our life and work, spiritual and communal rituals. Ordinary people in Ethiopia have engaged in “chefera” (loosely meaning playful dance) for ages, extracting movement and gestures from daily life and work. Our religious and spiritual traditions also make use of either improvised or choreographed movement, along with music, to express and embody our connections to the divine.

Our religious and spiritual traditions also make use of either improvised or choreographed movement, along with music, to express and embody our connections to the divine.

Currently, dance in Ethiopia is a diverse, growing professional field, encompassing traditional Ethiopian dance primarily distilled from indigenous movements as well as forms that are primarily influenced by Western traditions. Despite differences, we all agree that our shared field of dance needs cultural validation and institutional support.

Although dance artists make essential contributions to the social fabric of Ethiopia, we and our art forms are grossly undervalued by society.

Our profession is a modern formation that has developed along with the building of the Ethiopian nation since the turn of19th and 20th century. The traditional dance forms we know today have resulted from governments in the 20th century investing resources to research, synthesize, and stage the diverse indigenous movement traditions in Ethiopia.

This investment has declined significantly since the 1990s, and the social and economic status of dance professionals have suffered as a result. To advocate for ourselves and to uphold the profession, we established Ethiopian Dance Art Association in 2018. This was a historic step when dance’s contribution finally gained recognition by the government.

We now have the ability to participate in civil society and policy making at national and international levels. In 2019, within a year of establishing EDAA, we participated in a UN forum on cultural policies held in Addis Ababa. Now we are engaged in a UNESCO project to build our organizational capacity.

Our capacity building involves expanding membership to include dance artists from many regions of Ethiopia, strengthening leadership and financial accountability and developing research expertise. This work is being done with volunteer work from the founding members of EDAA, with support of international professionals knowledgeable about civil society organizations and dance research, and with UNESCO IFCD funding.

Through our collaborations and conversations, we are gaining more clarity as to what a vibrant field of dance in Ethiopia needs. What we express below is a necessary vision that will guide the work of dance professionals in Ethiopia in the coming years. We also hope that this vision will shape how the Ethiopian public and government think about the value and place of dance in our society.

To develop dance into a professional field, we need concerted effort from the government, the private sector, citizens and dance artists, with a shared vision.

Our vision is based on the premise that dance contributes to the wellbeing of the entire society by expressing our cultural identities, facilitating our social connections, maintaining health and healing from traumas. The dance field can only thrive if dancers are supported.

Therefore EDAA has taken the charge to facilitate professional development, social recognition, and economic security of Ethiopian artists regardless of gender and age. Our ultimate desire is to contribute to the peace and prosperity of our country.

Our ultimate desire is to contribute to the peace and prosperity of our country.

-

Ethiopian society recognizes dance as an essential cultural resource for expression, for healing, and for social cohesion.

Dancers are recognized as professional artists and guaranteed economic and social security (good salaries, life and health insurance, and retirement benefits) through their professional work, free of debasement and harassment, regardless of gender, age, class, and ethnicity.

A formally recognized school of dance, preferably incorporated into the university system.

This school will not only teach students to dance and choreography, but to think and write about dance and to conduct dance research, including both research in the humanities and scientific research about dance and its benefits.

This school will not only teach students to dance and choreography, but to think and write about dance and to conduct dance research, including both research in the humanities and scientific research about dance and its benefits. A national Ethiopian dance library and archive, including print and digital resources, such as Amharic and English publications on dance and compilation of digital archives of Ethiopian dance.

A comprehensive, multi-level curriculum of dance based on the research done at the university level, and drawing from the national archive, to be adopted by universities and schools alike.

Government investment in the existing state theaters and new performance companies that pay dancers decent wages, offer them employment benefits, and protect them from debasement such as sexual harassment.

Funding of dance and dance research by the private sector and individuals.

National and international dance festivals that signifie and facilitate international recognition of Ethiopian dance, and our engagement with international dance organizations and artists.

-

Numerous skilled Ethiopia dance artists working in the country and in the diaspora.

Existing state theaters and local groups.

Existing media and public interest in dance as means of entertainment and fitness.

International supporters with expertise on organizational capacity and dance research.

Existing dance archives that document the history of Ethiopian dance development.

Dedicated EDAA leadership to engage with the government, private sector and other stakeholders.

-

To continue to reach out to dance artists around the country to build consensus about the future of the field.

To talk to the media, the public, government, and tourist sector in order to raise awareness of our vision.

To raise funds and develop expertise to build a comprehensive dance and dance studies curriculum, with the school to follow in the future.

To engage with the diaspora and internationals interested in strengthening the dance sector in Ethiopia.

To establish an EDAA library. Support our library project with Books for Africa.

African dance | Belcanto.ru

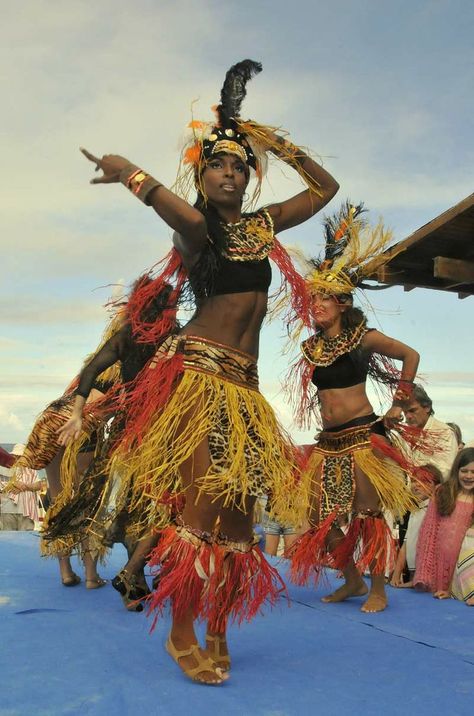

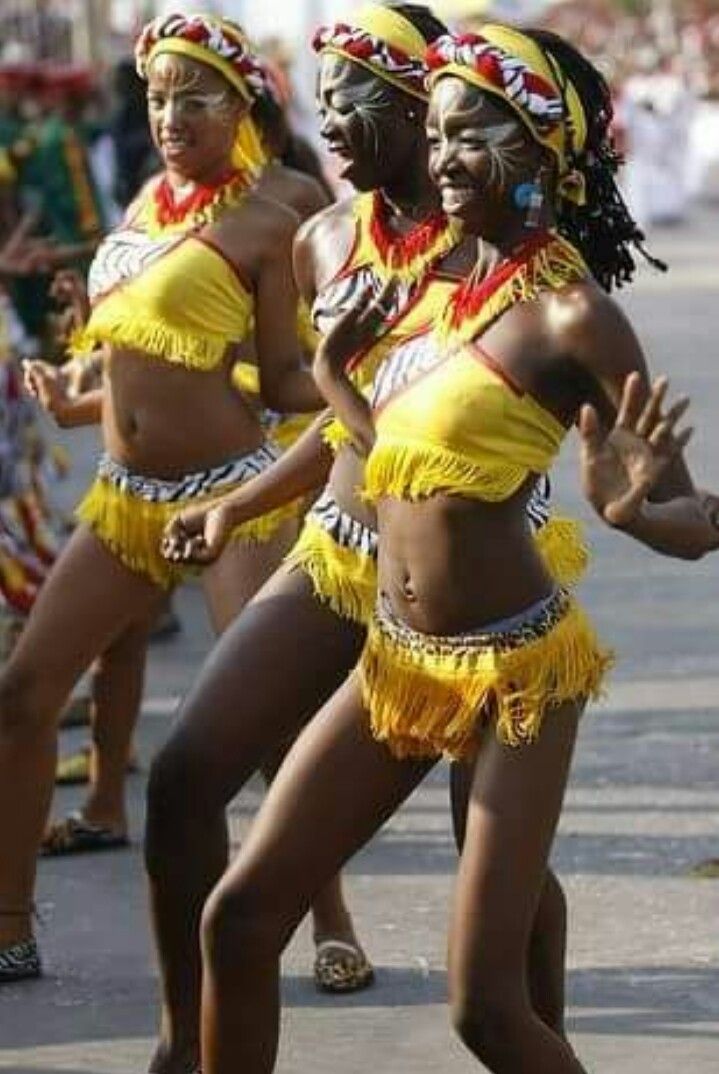

The concept that conditionally unites the original dances of the peoples inhabiting Africa. A. t. is inextricably linked with the life, religious beliefs, folklore of every nation that has its own historical. and ethnic. past. Dance. culture of the countries of the North. Africa (Algeria, Lebanon, Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia) developed under the influence of the common Arab-Muslim culture of the Mediterranean. An independent place in the development of A. t. is occupied by the cultures of the countries of the Ethiopian highlands and the peoples of the coast of the Southeast. Africa (the latter have long maintained ties with South Asia). Tropical zone, or so-called. Equatorial, Africa, despite the diversity of its ethnicity. composition, is characterized by an undoubted similarity in the conditions of cultural development and, according to the traditions of African studies, is considered separately from the sowing. and east. regions. Dances of the peoples Central., Zap. and Yuzh. Africa has been little studied.

Africa (the latter have long maintained ties with South Asia). Tropical zone, or so-called. Equatorial, Africa, despite the diversity of its ethnicity. composition, is characterized by an undoubted similarity in the conditions of cultural development and, according to the traditions of African studies, is considered separately from the sowing. and east. regions. Dances of the peoples Central., Zap. and Yuzh. Africa has been little studied.

Due to the originality of the historical fate of the African continent prof. dance the art of African peoples arose relatively recently and before the 20th century. was limited to the realm of folklore. The first information about A. t. give rock paintings (so-called petroglyphs) in the mountain ranges of the Sahara (8-6th millennium BC). The rock art of the Bushmen (South Africa) testifies to the role of dance in the life of Africans. The image is fantastic. creatures and dancing people in animal skins with horns and in elephant or antelope masks indicate the connection of the dance with the mythological. African perceptions. Terracotta figurines found in the area of Lake Chad, called "disguised dancers", whimsically combine the features of human figures with animal heads, which indicates the presence of masks as an indispensable attribute of dance. A. t. developed over many years. centuries is synthetic. genre, a bright fusion of sounds, colors and movements, full of meaning for an African who knows how to "read" it. His main rhythmic the pattern is associated with the rhythm of percussion instruments, primarily the "talking drums" of tom-toms. The dance is accompanied by choral singing, often accompanied by wind instruments - hunting horns, reed flutes, ocarinas, pipes made of elephant tusks and tree trunks. The brilliance and expressiveness of the dance is emphasized by the use of masks - ritual, cult, play, etc. (sometimes weighing up to 6-8 kg), bright makeup, tattoos, as well as costumes, stilts, bells, decomp. jewelry (bracelets, feathers, etc.), weapons.

African perceptions. Terracotta figurines found in the area of Lake Chad, called "disguised dancers", whimsically combine the features of human figures with animal heads, which indicates the presence of masks as an indispensable attribute of dance. A. t. developed over many years. centuries is synthetic. genre, a bright fusion of sounds, colors and movements, full of meaning for an African who knows how to "read" it. His main rhythmic the pattern is associated with the rhythm of percussion instruments, primarily the "talking drums" of tom-toms. The dance is accompanied by choral singing, often accompanied by wind instruments - hunting horns, reed flutes, ocarinas, pipes made of elephant tusks and tree trunks. The brilliance and expressiveness of the dance is emphasized by the use of masks - ritual, cult, play, etc. (sometimes weighing up to 6-8 kg), bright makeup, tattoos, as well as costumes, stilts, bells, decomp. jewelry (bracelets, feathers, etc.), weapons.

Most of the African dances. performances lasted several. hours (from sunset to morning). Tropical peoples. African dance was associated primarily with hunting and farming. Man used the language of dance, hoping to influence plants, animals and nature, to win them over. The hunters imitated the habits and cries of animals and birds; totemic performers dressed in animal skins. dances promised good luck in hunting. Before hunting for large animals, Africans arranged a big dance. representation. In costumes made of leopard, monkey, antelope or deer skins, with ostrich feather decorations on their heads, the dancers portrayed animals pursued by hunters. These dances were exceptional. richness, variety and sharpness of the rhythmic. drawing, for example. the Ndlamu dance of the Bantu peoples (South Africa), which has survived to this day, is performed by participants (up to 300 people) in costumes made of animal skins, fur bracelets and headdresses made of bird feathers. The composition of the dance is built linearly, the accuracy of the ensemble and the severity of discipline indicate a connection with the training of hunters.

performances lasted several. hours (from sunset to morning). Tropical peoples. African dance was associated primarily with hunting and farming. Man used the language of dance, hoping to influence plants, animals and nature, to win them over. The hunters imitated the habits and cries of animals and birds; totemic performers dressed in animal skins. dances promised good luck in hunting. Before hunting for large animals, Africans arranged a big dance. representation. In costumes made of leopard, monkey, antelope or deer skins, with ostrich feather decorations on their heads, the dancers portrayed animals pursued by hunters. These dances were exceptional. richness, variety and sharpness of the rhythmic. drawing, for example. the Ndlamu dance of the Bantu peoples (South Africa), which has survived to this day, is performed by participants (up to 300 people) in costumes made of animal skins, fur bracelets and headdresses made of bird feathers. The composition of the dance is built linearly, the accuracy of the ensemble and the severity of discipline indicate a connection with the training of hunters. Sticks adorned with white monkey fur replace spears. The participation of a soloist is obligatory, singing a song and setting the rhythm to the dance, gradually accelerating and becoming more and more complicated. Traces of the old hunting dance are worn by the muchongolo dance of the Pedi tribes (northern Basuto), one of the few that have survived in the tropics. Africa dancing with shields. The high skill of the muscles of the torso is demonstrated by the Hausa dances, united under the name uteiro (Northern Sudan). The Zulu deer hunting dance (South Africa) is interesting.

Sticks adorned with white monkey fur replace spears. The participation of a soloist is obligatory, singing a song and setting the rhythm to the dance, gradually accelerating and becoming more and more complicated. Traces of the old hunting dance are worn by the muchongolo dance of the Pedi tribes (northern Basuto), one of the few that have survived in the tropics. Africa dancing with shields. The high skill of the muscles of the torso is demonstrated by the Hausa dances, united under the name uteiro (Northern Sudan). The Zulu deer hunting dance (South Africa) is interesting.

Farmers, trying to bring the rain necessary for crops, recreated musical plastic. pictures of floating clouds, peals of thunder, pouring streams of water. Many tribes were widespread dances of birds that protect crops from pests, dances of "thanksgiving to nature". The dances performed in the agricultural ceremony have a more fluid character of play and dance movements (for example, the tashada dance in Western Sudan, performed by men in brightly painted headdresses with birds attached to them, holding a snake in their beak, the round dance of the ngoma of the Nguni tribes in South Africa). The dance, which symbolizes the power of man over domestic animals, is accompanied by the waving of whips from the tails of buffalo and is accompanied by songs about the earth and the harvest. An important place in the folklore of African peoples is occupied by ritual dances associated with the cult of ancestors. Their great emotional arts. the impact is aimed at creating a sense of collective community with the ancestors of the tribes. The ritual dance of worshiping ancestors and the desire to propitiate them requires great skill and lengthy preparation from the performers (for example, the solemn dance of chikone during the ritual of sacrifice to the ancestors by the leader). A special place is occupied by dances-rites of initiation of young men, which exist in many. areas of modern Africa (Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, Congo, etc.). The dances, symbolizing the new birth of man, were so complex that they required 3-4 months of rehearsals (for example, the Venda python dance). Improvisation dances were not allowed.

The dance, which symbolizes the power of man over domestic animals, is accompanied by the waving of whips from the tails of buffalo and is accompanied by songs about the earth and the harvest. An important place in the folklore of African peoples is occupied by ritual dances associated with the cult of ancestors. Their great emotional arts. the impact is aimed at creating a sense of collective community with the ancestors of the tribes. The ritual dance of worshiping ancestors and the desire to propitiate them requires great skill and lengthy preparation from the performers (for example, the solemn dance of chikone during the ritual of sacrifice to the ancestors by the leader). A special place is occupied by dances-rites of initiation of young men, which exist in many. areas of modern Africa (Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, Congo, etc.). The dances, symbolizing the new birth of man, were so complex that they required 3-4 months of rehearsals (for example, the Venda python dance). Improvisation dances were not allowed.

Most of the peoples of the Central, Western. and Yuzh. Africa before the 20th century did not have a written language (it was replaced by oral literature, music and dance art). Historical traditions, legends and myths were preserved and passed down from generation to generation by musicians-narrators (in West Africa - "griots", in South Africa - "imbongs"). People's speeches musicians and dancers are widespread in many places. African countries. Accompanying yourself on some music. instrument, they sing and dance, talk about the great events of the past, broadcast the news of today. These traditions continue into the 20th century. The leaders had singers and dancers in their retinue, whose duties included singing and dancing to praise the leaders themselves and their guests, inspire the members of the tribe in the fight against enemies, mourn the heroes, ridicule the unworthy. In connection with the victory, whole performances were arranged. With the disintegration of the tribal organization and the gradual disappearance of the ancient traditions, art lost its ritual and cult character. In some African countries, prof. dancers performing to the public at rural holidays. In parallel with ritual performances, comedy began to develop. masquerades are purely entertaining.

In some African countries, prof. dancers performing to the public at rural holidays. In parallel with ritual performances, comedy began to develop. masquerades are purely entertaining.

The long domination of the colonialists in Africa disrupted the natural process of cultural development of the African peoples. The colonialists destroyed culture and arts. values of the local population. The age-old heritage of the African peoples was declared inferior, and antiquities were eradicated as "barbaric" and "idolatrous."

With the success of the national liberation. movement of the peoples of Africa and the emergence of independent African states, the question of the development of African culture became acute. The problems of cultural development are not resolved everywhere in the same way, not all countries can allocate sufficient funds for these purposes. In many African states created cultural centers, which, along with the collection of muses. folklore organize song and dance ensembles, hold festivals and reviews, which are of great importance for the preservation and dissemination of cultural heritage. Progressive cultural figures are trying to develop and renew the Nar. art in accordance with the needs of the present. They associate the development of folklore traditions with mastering the best achievements of world art.

Progressive cultural figures are trying to develop and renew the Nar. art in accordance with the needs of the present. They associate the development of folklore traditions with mastering the best achievements of world art.

First prof. The ensemble of A. t. was organized in 1948-49 in Paris by the Guinean Keita Fodeba. Since 1950 under the name African ballets this group toured Europe. The experience of the African ballet team was used by other dancers. teams from Guinea - "Joloba" and Nat. ballet of Guinea, toured with the dance. compositions ("The creator is the people", "New Guinea", "Midnight") in Bulgaria (1960), the GDR (1961), the USSR (1968) and other countries. In the repertoire of the National Ballet of Guinea includes dance. pantomime from the play "Stages", showing peaceful labor before the arrival of Europeans, colonial slavery, rebellion and liberation. Many performances are staged by the leading dancer of this troupe, Cisco Amadou.

The development of African national dance was especially active in Senegal. In 1961, under the direction of Maurice Sonara Senghor and Abu Mama Diouf formed the National Ballet Ensemble of Senegal, which showed, in addition to dance numbers, genre sketches "Scenes from the life of the people" and muses. performances. National The Senegal Ballet Ensemble toured Great Britain, Belgium, Holland, France, Germany, and Switzerland. The ballet "Dianka Vali" was shown by the ensemble in Moscow in 1975. In Dakar there is also an art school with a dance department. Dance. Ensembles have also been set up in a number of other towns in Senegal. At 1964 in Dakar, another music and dance group began to work, showing the play "The Adventure of Rhythm".

In 1961, under the direction of Maurice Sonara Senghor and Abu Mama Diouf formed the National Ballet Ensemble of Senegal, which showed, in addition to dance numbers, genre sketches "Scenes from the life of the people" and muses. performances. National The Senegal Ballet Ensemble toured Great Britain, Belgium, Holland, France, Germany, and Switzerland. The ballet "Dianka Vali" was shown by the ensemble in Moscow in 1975. In Dakar there is also an art school with a dance department. Dance. Ensembles have also been set up in a number of other towns in Senegal. At 1964 in Dakar, another music and dance group began to work, showing the play "The Adventure of Rhythm".

In the Republic of the Ivory Coast at the Center for Culture and Folklore Nat. Institute of Arts in 1959 in Abidjan was established theater. a troupe whose repertoire consisted of dances and small skits based on folklore material. In 1960 the troupe performed at a festival at the Théâtre des Nations in Paris. On the day of the independence of Upper Volta, the first performance of dances took place in Ouagadougou. collective of the country "Daughter of Volta" (headed by Musa Savadny).

collective of the country "Daughter of Volta" (headed by Musa Savadny).

In Nigeria, in 1964, the ballet troupe Ori Olokun Dance Company was founded at the University of Ife in Ibadan, whose experimental productions caused great controversy among African cultural figures. The leader of the troupe, P. Harper, seeks to synthesize elements of Yoruba folklore, the traditional A. t. with some modern techniques. European and Amer. ballet. In 1971, at the competition of the magazine "African Arts", the experimental performance "Alatangana" was recognized as the best. In this play on a mythological plot, dances of different peoples of Nigeria were used. At the seminar "Oral tradition of the Yoruba", held at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ife, the troupe showed the play "Ogun Onire", where the language is classical. European dance combined with African elements. The production of "Purakpali" based on a story from Australian mythology has the same character.

By the time of the independence of the Congo (Brazzaville) in 1960, the Congolia ballet company was formed, demonstrating the art of the Equatorial province and other regions of the country. Later, the ensemble "Nguakatour", or "Ballet Diabua" (headed by M.I. Diabua) was created. In 1972, the National Ensemble of the People's Republic of the Congo.

Later, the ensemble "Nguakatour", or "Ballet Diabua" (headed by M.I. Diabua) was created. In 1972, the National Ensemble of the People's Republic of the Congo.

In Africa and abroad, the ballet troupe of Sierra Leone (created in 1963, under the direction of D. Akar), the Ensemble of the Republic of Chad (headed by Ngerio Butl Sektil), and Dance are also gaining popularity. Ensemble of the Republic of Zambia (headed by Mofiya), Nat. ballet company of the Republic of Benin (headed by E. Gay). At the Algiers Festival 1969 was awarded the Nat. the Liberian troupe (in its repertoire the ballets "Farmers", "Child of Sorrow", "Gratitude to Africa"). In 1975, the Ensemble of the Republic of Mali came to Moscow on tour. Permanent prof. opera and ballet theaters were created in Ethiopia (headed by R. Hagen, a musician from Australia). Several folk ensembles. dance exists in Sudan. In 1961, a dance department was organized at the Council of Arts in Ghana, on the basis of Legon University, the Institute for African Studies, and the National. ensemble (headed by A. Onoku).

ensemble (headed by A. Onoku).

Ways of development prof. ballet in the Republic of South Africa are difficult because of the apartheid regime and racial discrimination against the African population. Universities provide training. The University of Cape Town has a music faculty, including a ballet school (with a department for Bantu). Despite the opposition of the authorities, folklore dances are included in many. dramatic performances ("Umbata", staged at 1972; adaptation of Shakespeare's "Macbeth" in Zulu. full of dances of the Bantu peoples).

First experimental post. theaters of the East. Africa "Chikkvakwa Theater" (created by M. Ezeron in 1971 in Lusaka on the basis of the Arts Department of the University of Lusaka, Zambia), a troupe of the theater department. arts at the University of Dares Salam (Tanzania) and others are saturated with folklore dances. Numerous competitions, conferences and festivals dedicated to African music. culture and ballet, popularize the activities of dance. groups in African countries. Traditional African culture and, in particular, dance have a meaning. influence on modern European and Amer. choreography. From 1966 in Dakar festivals of Negro art are held, where numerous people perform. dance teams.

groups in African countries. Traditional African culture and, in particular, dance have a meaning. influence on modern European and Amer. choreography. From 1966 in Dakar festivals of Negro art are held, where numerous people perform. dance teams.

Ballet. Encyclopedia, SE, 1981

11 words to help you understand Ethiopian culture • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

- History

- Art

- Literature

- Anthropology

I'm lucky!

Anthropology

Why are artisans in Ethiopia considered sorcerers and werewolves, is it possible to dance without a song and vice versa, and what do fetching water and gossip have in common?

Author Maria Bulakh

This year, the HSE Institute of Classical Oriental and Antiquity opened admissions for the new bachelor's program "Ethiopia and the Arab World" for the first time. To help prospective students make their choice, Arzamas asked the academic director of the program, Maria Bulakh, to talk about the culture of Ethiopia through its basic concepts

To help prospective students make their choice, Arzamas asked the academic director of the program, Maria Bulakh, to talk about the culture of Ethiopia through its basic concepts

1. Injera (ənǧära)

Ethiopian bread

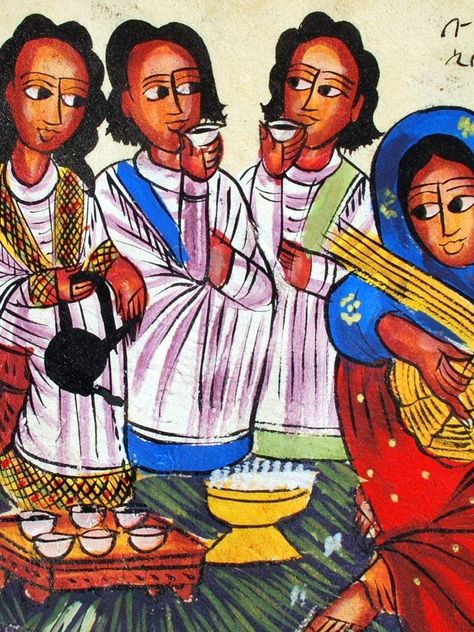

Ethiopian women making injera. Fresco on the main staircase of Abbadie Castle The owner of the castle, Antoine d'Abbadie, a French explorer and traveler of the 19th century, spent more than 10 years in Ethiopia and made a huge contribution to the study of its geography, ethnography and languages. © ethiopiko.org Eunjera is Ethiopian bread. However, it doesn’t look like bread at all, but rather giant pancakes of a grayish tint (the lighter, the better the quality), loose and unsweetened, with a specific sour taste. Flour for ynjera should be from tef ( ṭef ), a special cereal that grows only in the fertile regions of the Ethiopian highlands. But sometimes other cereals are also used, most often sorghum.

A large ınjera pancake is spread on a round dish called gebeta ( gäbäta ), meat, rice, boiled vegetables, cottage cheese are spread on top - in a word, anything. Then the ynjeru is twisted, pieces are torn off from it, the filling is selected for it, dipped in the sauce and sent to the mouth. Eating alone is not accepted, any meal - from a modest snack to a luxurious feast - is a gathering of people around the gebeta. Spouses or lovers often put pieces of ynjera in each other's mouths, thus showing special tenderness and care. This custom is so popular that now, as part of the fight against coronavirus, along with calls not to shake hands and not to kiss, recommendations are being distributed: "Do not feed out of each other's hands!" ( Attəggoraräsu! ).. Such a piece is called gursha ( gurša , from the verb gorräsä , "to put food in the mouth"). By the way, it is this word in modern Ethiopia that means “tipping”.

Of course, when reading the Lord's Prayer in Amharic, Ethiopian Christians ask for a daily ynjere. A person in search of a job is called ənǧära fällagi - "yndzhera seeker". “To give to ynjeru” means “to feed, to give food”. Therefore, the stepmother is called "Indzhera's mother", and the stepfather is called "Indzhera's father". Finally, ynjera is the most pleasant thing you can imagine - they can say about a kind, gentle person: "His character is just ynjera."

A person in search of a job is called ənǧära fällagi - "yndzhera seeker". “To give to ynjeru” means “to feed, to give food”. Therefore, the stepmother is called "Indzhera's mother", and the stepfather is called "Indzhera's father". Finally, ynjera is the most pleasant thing you can imagine - they can say about a kind, gentle person: "His character is just ynjera."

2. Farange (färänǧ)

White man

Audrey Hepburn in Ethiopia with the UNICEF mission. 1988 © Derek Hudson / Getty ImagesThe Ferengi is you and me. Any person with a more or less light skin tone, once in Ethiopia, immediately turns into a farenja. Kids running after you down the street in Addis Ababa, or Lalibela, or any other town or village, will yell, "Farange, farenj!" - and they will try to grab your hand, because touching a Farenge is considered a good omen.

Farangi are alien and incomprehensible people. This is not the name of an African from a neighboring or distant country, nor an Arab, nor even an Indian. The attitude towards Farenges is ambivalent. Farange is a source of money, and therefore an object of close and often annoying attention. At the same time, the Farange, although respected, also arouses suspicion: what if he is not just a curious tourist, but has come with a mercenary purpose? And of course, the Farenju cannot hide in this country, not pretend to be local. No matter how well he speaks Amharic or other Ethiopian languages, he will still remain a Farenge - incomprehensible, unlike, strange.

The attitude towards Farenges is ambivalent. Farange is a source of money, and therefore an object of close and often annoying attention. At the same time, the Farange, although respected, also arouses suspicion: what if he is not just a curious tourist, but has come with a mercenary purpose? And of course, the Farenju cannot hide in this country, not pretend to be local. No matter how well he speaks Amharic or other Ethiopian languages, he will still remain a Farenge - incomprehensible, unlike, strange.

This word, however, can be heard not only in Ethiopia: it is used in various versions in other countries of Africa, and in a number of Arab countries, and in India. It goes back to the ethnonym "Frank", which came through the Arabic language ( ʔifranǧ ). Initially, the word "farenj" in Ethiopia was called Catholics, and later Protestants. Today, these religious associations have faded into the background (for example, in the Ethiopian diaspora in Israel, this word is used to refer to native Israelis). So in modern Amharic there is not only the expression yäfäränǧ gänna 'Catholic Christmas' (literally 'Fairen's Christmas'), but also yäfäränǧ addis amät 'European New Year' (literally 'Fairen's New Year'). The first is contrasted with Ethiopian Christmas gänna (from Greek γέννα ), which is celebrated, as Orthodox Christmas is supposed to, on January 7th. The second is the Ethiopian New Year holiday, celebrated on September 11th.

So in modern Amharic there is not only the expression yäfäränǧ gänna 'Catholic Christmas' (literally 'Fairen's Christmas'), but also yäfäränǧ addis amät 'European New Year' (literally 'Fairen's New Year'). The first is contrasted with Ethiopian Christmas gänna (from Greek γέννα ), which is celebrated, as Orthodox Christmas is supposed to, on January 7th. The second is the Ethiopian New Year holiday, celebrated on September 11th.

And the word "farange" appears in the names of some overseas plants that have become widespread in Ethiopia only recently. Let's say the cucumber is called yäfäränǧ duba (“Farenga gourd”).

3. Habesha (habäša)

Abyssinian

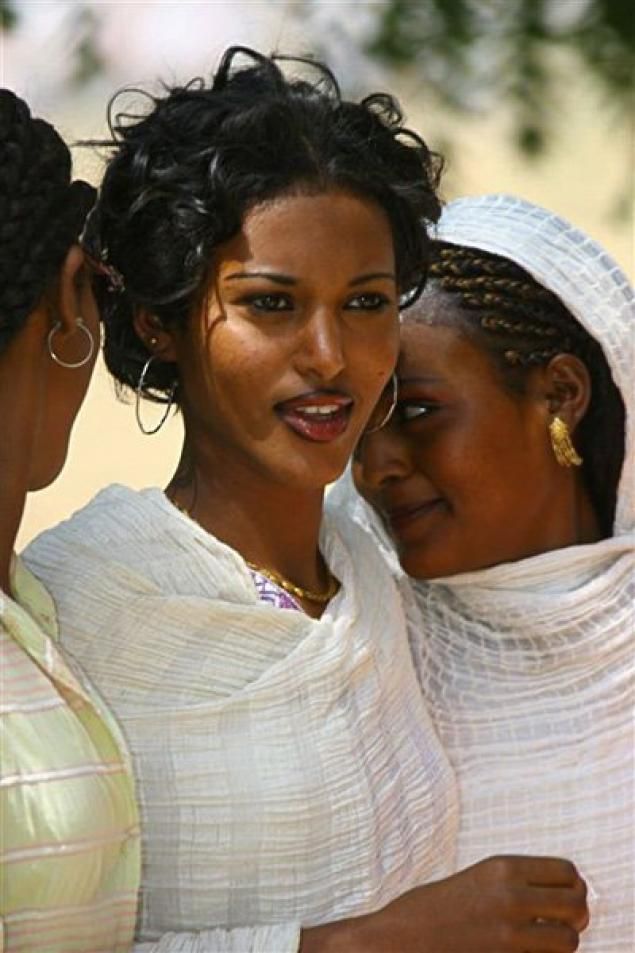

Abyssinians. From a series of Ethiopian photographs of Captain Tristram Speedy. 1860s Bonhams This is how many Ethiopians call their people - that is, Christians who inhabit the Ethiopian highlands and speak Semitic languages, Amharic and Tigrinya. Both Amharic and Tigrinya can refer to themselves as habesha (tigrinya ḥabäša , Amharic habäša or abäša ). This word is also used by Ethiopians who are far from their homeland, and now in many cities in Europe you can see a cafe called Habesha Bar or something like that. On the one hand, the word "habesha" can be opposed to the word "farenj". But on the other hand, in Ethiopia itself, it refers only to a part of the population - these are Christians living in the central regions.

Both Amharic and Tigrinya can refer to themselves as habesha (tigrinya ḥabäša , Amharic habäša or abäša ). This word is also used by Ethiopians who are far from their homeland, and now in many cities in Europe you can see a cafe called Habesha Bar or something like that. On the one hand, the word "habesha" can be opposed to the word "farenj". But on the other hand, in Ethiopia itself, it refers only to a part of the population - these are Christians living in the central regions.

The word "habesha", like "farenj", apparently came to the modern languages of Ethiopia from Arabic, where the traditional name of Ethiopia is al-Ḥabaša . The Arabic word goes back to the ancient name of a tribe or people, attested already in the first millennium in monuments on the territory of South Arabia (and also in Ethiopia itself, where, however, this word did not take root). In the Middle Ages, the name al-Ḥabaša from the Arabic language re-entered Ethiopia. The same Arabic word was the source for the European name Abyssinia, by which Ethiopia was known until the 20th century. This is how Nikolai Gumilyov called Ethiopia both in his poetry (“Abyssinian Songs”) and in travel notes made during several expeditions to this country.

The same Arabic word was the source for the European name Abyssinia, by which Ethiopia was known until the 20th century. This is how Nikolai Gumilyov called Ethiopia both in his poetry (“Abyssinian Songs”) and in travel notes made during several expeditions to this country.

During the 20th century, the word "Abyssinia" gradually fell out of use: both in the constitution of 1931 and in international politics, the name "Ethiopia" began to be used as the official name of the country. Today in Ethiopia, the word "Abyssinia" can be found in the name of the oldest bank in the country, Bank of Abyssinia, or in the popular song of the national pop star Tewodros Kassahun, or Teddy Afro, "Ethiopia, Abyssinia ...".

other words from other cultures

12 Filipino words

Infinite gratitude and the ability to avoid conflicts

11 Persian words

Good reputation, the sale of wisdom and ostentatious intelligence

12 Italian words

Local patriotism, “Current Coffee” and “Man with three nostrils”

4.

Ityoṗyawinnät (Ityoṗyawinnät)

Ityoṗyawinnät (Ityoṗyawinnät) Ethiopian

Portrait of Emperor Tewodros II, who united Ethiopia into a single empire. Painting by Yshetu Tyruneh Etiopijos nacionalinis muziejus Ethiopian ( ʔityoṗyawinnät, - derived from the word ʔityoṗyawi - "Ethiopian") means the equality of all citizens at the state level. To understand why, let's look at the history of the word "Ethiopia". The name Ethiopia is as old as Abyssinia, but has always been much broader. Initially, it was not at all tied to the territories of the Horn of Africa: in Greek, αἰθίοψ ("Ethiopian") literally means "burnt-faced, (person) with a burnt face" (from αἴθω, αἴθομαι, "burn", ὄψ, "appearance, face" ), and Aἰθιοπία - "a country of people with burnt faces". In early Greek sources, the toponym Aἰθιοπία could be used to denote distant lands both in the southeast (in Africa and Asia) and in the southwest (in Africa). In particular, India was often referred to by this term (while India, in turn, could be called Arabia and Ethiopia).

Greek was actively used in ancient Ethiopia: it was the language of trade on the Red Sea, in which the ancient Ethiopian state of Aksum actively participated. The rulers of Aksum often referred to themselves as kings of the Ethiopians in Greek inscriptions. Apparently, already in the Aksumite period, the name Ethiopia entered the local languages, and in the Middle Ages, local chroniclers used this word to call their Christian state. In contrast to the word "habesha", the name Ethiopia became associated not with a specific territory and its population, united by a common culture and religion, but with the state.

Ethiopia is a multinational state inhabited by representatives of more than 90 nationalities. For centuries, the Amhara people have been in power, which, at the same time, is not the most numerous, today inferior in number to the Oromo people. That is why the term "Ethiopia" turned out to be very useful in revolutionary and post-revolutionary times, when the principles of equality of all peoples inhabiting the country began to be proclaimed. So, the slogan "Forward, Ethiopia!" ( Ityoṗya təqdəm , literally "Let Ethiopia lead!") was put forward already in the first days of the 19 revolution74 years old: it was a patriotic slogan, but addressed to all the inhabitants of the country, regardless of their ethnicity. In fact, the word ʔityoṗyawi ( "Ethiopian") is equally applicable to all the inhabitants of the country: today, representatives of different nationalities proudly call themselves that way.

So, the slogan "Forward, Ethiopia!" ( Ityoṗya təqdəm , literally "Let Ethiopia lead!") was put forward already in the first days of the 19 revolution74 years old: it was a patriotic slogan, but addressed to all the inhabitants of the country, regardless of their ethnicity. In fact, the word ʔityoṗyawi ( "Ethiopian") is equally applicable to all the inhabitants of the country: today, representatives of different nationalities proudly call themselves that way.

Of course, the introduction of the concept ʔityoṗyawinnät did not solve the national question. On the contrary, it is interethnic conflicts that are one of the most acute problems of today's Ethiopia. But it is significant that Ethiopia is equally dear to both the ruling party and the protesters. It is no coincidence that in one of the recent conflicts, representatives of the Sidamo people came up with the slogan Sidamannät kälelä ʔityoṗyawinnät yälläm - “If there is no Sidamism, there will be no Ethiopianism”, where sidamannät is a word formed on the same principle as ʔityoṗyawinnät . That is, "there is no harmonious multinational state without the right to self-determination for each individual people, such as the Sidamo."

That is, "there is no harmonious multinational state without the right to self-determination for each individual people, such as the Sidamo."

5. Därg

Military junta; literally "committee"

Derga First Deputy Chairman Mengistu Haile Mariam. 1977 © Universal Images Group / Diomedia The word därg comes from the Old Ethiopian language (Ge'ez). Old Ethiopian is now used only in worship, but Old Ethiopian vocabulary often serves as a source for the formation of neologisms - approximately as if in modern Russian they began to use the words of the Church Slavonic language instead of European borrowings. In Old Ethiopian, the word därg means "union, connection", but is most often used in adverbial phrases därgä or bä-därg (“together, in a group”). In Amharic, it has become synonymous with the French loanword komite ("committee"). However, only one committee was called därg - the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, the Police and the Ground Forces, formed in 1974 by the revolutionary-minded military. When Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown on September 12, 1974, this organization was renamed the Provisional Military Administrative Committee ( gizeyawi wättadärawi astädadär därg ). At the same time, the word abyot ("revolution"), also taken from the Old Ethiopic language, where ʔabəyot means "disobedience", and the expression abyot fänädda ("revolution exploded"), which clearly reflects suddenness, entered the Amharic language. and disastrous consequences of this event.

When Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown on September 12, 1974, this organization was renamed the Provisional Military Administrative Committee ( gizeyawi wättadärawi astädadär därg ). At the same time, the word abyot ("revolution"), also taken from the Old Ethiopic language, where ʔabəyot means "disobedience", and the expression abyot fänädda ("revolution exploded"), which clearly reflects suddenness, entered the Amharic language. and disastrous consequences of this event.

Formally, General Teferi Bante held the chair of the Derg, but Major (later Colonel) Mengistu Haile Mariam, the first vice-chairman of the Derg, became the de facto leader. Derg's ideology was expressed by the word ḥəbrätäsäbawinnät "socialism". This is another neologism that uses ancient Ethiopian roots and word-formation principles: ḥəbrätä säb (literally “union of people”) in the Amharic language means “society, society”. Hence the adjective ḥəbrätäsäbawi "public, social". Already by adding the Amharic suffix -nnät , an abstract noun ḥəbrätäsäbawinnät is formed from the adjective. Ethiopian socialism proclaimed the equality of all the peoples of Ethiopia and the principle of "land to the plowman" ( märet läʔarašu ). However, the land reform actually turned into state control over the agricultural sector, and the desire to exterminate dissidents and eliminate political competitors resulted in a terrible “red terror” ( ḳäy šəbbər ). The Derg, although called temporary, remained the ruling power until 1987, when Ethiopia was declared the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Mengistu Haile Mariam was "elected" as its president, that is, he became the sovereign ruler for four years, until his flight at 1991 years.

Already by adding the Amharic suffix -nnät , an abstract noun ḥəbrätäsäbawinnät is formed from the adjective. Ethiopian socialism proclaimed the equality of all the peoples of Ethiopia and the principle of "land to the plowman" ( märet läʔarašu ). However, the land reform actually turned into state control over the agricultural sector, and the desire to exterminate dissidents and eliminate political competitors resulted in a terrible “red terror” ( ḳäy šəbbər ). The Derg, although called temporary, remained the ruling power until 1987, when Ethiopia was declared the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Mengistu Haile Mariam was "elected" as its president, that is, he became the sovereign ruler for four years, until his flight at 1991 years.

In the memory of people, the period of Derg's reign was remembered as a time of bloody executions and a harsh dictatorship. You can hardly meet people who remember the time of Derg ( yädärg gize ) with nostalgia; except that the former dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam himself, now living in the Republic of Zimbabwe. During the years of Mengistu Haile Mariam's rule, Ethiopia became one of the poorest countries in the world, survived famine and civil war. At home, the High Court of Ethiopia sentenced him in absentia to life imprisonment and then to death..

During the years of Mengistu Haile Mariam's rule, Ethiopia became one of the poorest countries in the world, survived famine and civil war. At home, the High Court of Ethiopia sentenced him in absentia to life imprisonment and then to death..

6. Qedda (qädda)

Copy, multiply entities; literally "to draw or pour water"

A postcard depicting rural women from Arusi carrying water. Addis Ababa, 1957 HipPostcardFor most rural Ethiopians, and indeed many urban women, fetching water is still one of the heaviest daily chores. For residents - because this is a traditionally female occupation: every morning it is women who shoulder a plastic canister ( ǧärikan , from English jerry can ), which replaced the earthenware jug ( ənsəra ), go down to the river, fill ( qädda ) the container with water, far from always clean, and, bending under the load, are returning home.

The verb qädda not only means “to fill with water” (a jug or canister), but also “to pour liquid from a larger vessel into a smaller one”—for example, to pour coffee from a traditional jaeben coffee pot into porcelain cups ( ǧäbäna ). Qädda is also taking someone else's fire, for example, to light a candle or light it from someone else's cigarette. And wäre qädda (“to scoop / pour a conversation”) means “to gossip, gossip” (after all, news, like water from a vessel to a vessel, overflows from one mouth to another).

Qädda is also taking someone else's fire, for example, to light a candle or light it from someone else's cigarette. And wäre qädda (“to scoop / pour a conversation”) means “to gossip, gossip” (after all, news, like water from a vessel to a vessel, overflows from one mouth to another).

Of course, we all often use the Russian verb "to draw" in the sense of "to borrow (thoughts, ideas, etc.)". In Amharic and in many other Ethiopian languages, "scoop" is also used in a figurative sense, but in a much narrower sense: it means "imitate, imitate", as well as "make a copy, write off, record", including "make an audio recording". It is based on the idea that a person who draws water from a source into a vessel, as it were, recreates the source, produces its analogue. This metaphor has become so firmly established in the language that modern photocopies are called the word qəǧǧ , derived from qädda , literally "something scooped up".

Urubamba children's podcast about Ethiopia

How to shake shoulders? How to remember 80 relatives? And is it true that eating with your hands tastes better?

7.

Teiyb (ṭäyəb)

Teiyb (ṭäyəb) A person of the lowest grade; literally "craftsman"

A woman spinning cotton. Traditional Ethiopian leather painting © eBayṬäyəb is the general name for all artisans, that is, blacksmiths, tanners, weavers, potters (or rather, potters, because only women work with clay). Ṭäyəb comes from the word ṭäbib , "wise" (sometimes the latter is also used in the meaning of "craftsman"). The very concept of "craft" is denoted by the expression "wisdom of the hand" ( yäʔəǧǧ ṭəbäb ) - as opposed to "wisdom of reading" ( yänäbib ṭəbäb ), which refers to book knowledge that has no practical application.

This origin of the word ṭäyəb does not at all fit with its use. This word is associated primarily with negative qualities - artisans ( ṭäyəbočč ) in Ethiopia from time immemorial were considered dirty, foul-smelling and prone to various vices.

All of the above crafts were despised in traditional rural Ethiopia. Peasant farmers looked at artisans as people of the lowest grade and never entered into family ties with them. Craftsmen often settled on the outskirts of the village, they did not own the land on which they lived, and if the demand for their work fell, they easily removed from their place and moved to another area.

Artisans were also considered sorcerers and werewolves. It is no coincidence that many prayers against evil spells, written in magic scrolls - parchment amulets that were worn on the chest in a special leather case or hung on the wall - begin with the words: "Prayer from the evil eye, and from the demon, and from the artisan / blacksmith ( ṭäbib )…” Religious prejudices are also mixed in here: after all, due to the fact that artisans belonged to a lower caste, as a rule, they were also ethnically different from farmers. In former times, in Northern Ethiopia, this niche was most often occupied by Ethiopian Jews - representatives of the Beta Israel people, who professed Judaism. At the end of the 20th century, the majority of Beta Israel emigrated to Israel, restoring, so to speak, historical justice, because betä əsraʔel literally means "the house of Israel".. It is clear that various supernatural abilities were attributed to the Gentiles engaged in unclean work, and, of course, no good was expected from them. In this sense, the word ṭäbib/ṭäyəb could become synonymous with the word "buda" ( buda ) - "hyena man". According to Ethiopian beliefs, a buda is a werewolf with an evil eye and the ability to turn into a hyena. The hyena eats its victim and sucks out the blood, that is, it sends damage, from which the victim withers and gradually dies. Such abilities were attributed primarily to blacksmiths. And since Ethiopian Jews were often engaged in blacksmithing, there was an idea that Jewish blacksmiths descended from the blacksmith who forged the nails for the crucifixion of Christ.

At the end of the 20th century, the majority of Beta Israel emigrated to Israel, restoring, so to speak, historical justice, because betä əsraʔel literally means "the house of Israel".. It is clear that various supernatural abilities were attributed to the Gentiles engaged in unclean work, and, of course, no good was expected from them. In this sense, the word ṭäbib/ṭäyəb could become synonymous with the word "buda" ( buda ) - "hyena man". According to Ethiopian beliefs, a buda is a werewolf with an evil eye and the ability to turn into a hyena. The hyena eats its victim and sucks out the blood, that is, it sends damage, from which the victim withers and gradually dies. Such abilities were attributed primarily to blacksmiths. And since Ethiopian Jews were often engaged in blacksmithing, there was an idea that Jewish blacksmiths descended from the blacksmith who forged the nails for the crucifixion of Christ.

Of course, much has changed in modern Ethiopia, and over the past fifty years there has been a consistent destruction of the caste system, as well as many other foundations of traditional society. However, this process is gradual, and in those areas of the country where the traditional village way of life is preserved, the superstitious fear of the werewolf artisan remains in the mind.

However, this process is gradual, and in those areas of the country where the traditional village way of life is preserved, the superstitious fear of the werewolf artisan remains in the mind.

8. Cheffare (č̣äffärä)

Sing and dance

Liebig promotional card featuring an Ethiopian military dance. 1906 © Getty ImagesThe word č̣äffärä is used to describe how many people sing and dance, usually during a big celebration.

Interestingly, the verb with ̣̌äffärä traditionally also meant "to assemble in detachments, to mobilize before a big battle." The fact is that such meetings were also inevitably accompanied by singing and dancing (it is no coincidence that the noun с̣̌əffära (“dance with song”) is often found in the narrower sense of “war dance”).

The fact that one word, from our point of view, means two actions - singing and dancing - is not surprising. From the point of view of an Ethiopian, it is strange to dance without a song or, conversely, to sing without moving to the music.

On the other hand, secular and church singing/dance are clearly distinguished. The latter will never be called verb č̣äffärä . The word zämmärä . This word is connected with the noun mäzmur (“psalm”) and the title of the book with which, for many centuries, a school began for everyone who learned to read and write in Christian Ethiopia: mäzmurä Dawit (“Psalms of David”), that is, the Psalter .

9. Gytym (gəṭəm)

Poetry

Azmari playing the begen. 1930 Period PaperThis word comes from the verb gäṭṭämä , which in Amharic means "converge, meet, unite." Let's say gubaʔe gäṭṭämä - "the meeting came together, got together", and с̌əggər gäṭṭämäw - "he encountered a problem". Hence aggaṭṭami - "coincidence, accident", and bagaṭṭami - "accidentally, accidentally, by coincidence".

Gəṭəm is “connection of words”, and gäṭṭämä can also mean “to connect words, compose poetry”. The process of creating a poem is the process of finding the right combinations, isn't it? However, originally word gəṭəm meant not poetry in the modern sense, but samples of folk art, performed - as it should be for folk works - in the form of songs. It was precisely this kind of poetry that wandering musicians performed - azmari ( azmari ) Amusingly, this name is historically associated with the term for church music, which was mentioned above. , literally “poetry of lamentation”), etc. Often poetic works were performed impromptu, and in traditional descriptions of certain historical events one can find a mention that a certain historical person, having heard bad or good news, utters a couplet appropriate to the occasion. So, in one of the stories about Empress Taitu it is said that, mourning the death of her husband, the great emperor Menelik II, she uttered the following poem:

The process of creating a poem is the process of finding the right combinations, isn't it? However, originally word gəṭəm meant not poetry in the modern sense, but samples of folk art, performed - as it should be for folk works - in the form of songs. It was precisely this kind of poetry that wandering musicians performed - azmari ( azmari ) Amusingly, this name is historically associated with the term for church music, which was mentioned above. , literally “poetry of lamentation”), etc. Often poetic works were performed impromptu, and in traditional descriptions of certain historical events one can find a mention that a certain historical person, having heard bad or good news, utters a couplet appropriate to the occasion. So, in one of the stories about Empress Taitu it is said that, mourning the death of her husband, the great emperor Menelik II, she uttered the following poem:

Säw mähon ayqärrəm därräsä täračcən [Earlier] it was our business only to order that the drum be beaten and the ymbilta [a traditional wind instrument, like the drum, used during solemn ceremonies with the participation of the emperor], and now it's the turn to become a [simple] person . Author's translation.

Author's translation.

In the 20th century, the term gəṭəm began to be used in relation to poetry in the modern sense, hence gäṭami - "poet". And for the special designation of folklore poetic works, the word qalgəṭəm appeared, literally “poetry of the word”, that is, oral poetry.

10. Fidäl (fidäl)

Letters

Two scribes. Miniature from a manuscript from Aksum. Early 18th century Wikimedia Commons The origin of the word fidäl is unknown, but it is already mentioned in the dictionary of the Old Ethiopic language, published in 1661 by the father of Ethiopian studies, the German scholar Job Ludolph, as the name of the Ethiopian syllabary as a whole or its elements. The syllabary is an analogue of the alphabet, which consists of symbols denoting not individual sounds, but syllables. In most Semitic alphabets - Phoenician, Ugaritic, Hebrew, Arabic, South Arabian - letters denote consonants, and additional diacritics may be used for vowels. Ethiopian writing (with the exception of the earliest periods) always denotes vowels, but does not use separate characters for vowels. Instead, each sign has seven forms (orders), according to the number of vowels. The Ethiopians call these seven forms "geez" ( gəʕəz , i.e. proper “Old Ethiopian”), “second” ( kaʕəb ), “third” ( śaləs ) etc. The sixth order - sadəəəs - is used either to combine the consonant with the vowel 90 (pronounced approximately like Russian [s]), or to indicate a single consonant. And learning to write is “counting letters” ( fidäl qoṭṭärä ). Children in a traditional church school ( nəbab bet , "reading house") learn to read by repeating each syllable in order, starting with the first consonant h : ha, hu, hi ... That is why the "alphabet" in Amharic is hahu .

Ethiopian writing (with the exception of the earliest periods) always denotes vowels, but does not use separate characters for vowels. Instead, each sign has seven forms (orders), according to the number of vowels. The Ethiopians call these seven forms "geez" ( gəʕəz , i.e. proper “Old Ethiopian”), “second” ( kaʕəb ), “third” ( śaləs ) etc. The sixth order - sadəəəs - is used either to combine the consonant with the vowel 90 (pronounced approximately like Russian [s]), or to indicate a single consonant. And learning to write is “counting letters” ( fidäl qoṭṭärä ). Children in a traditional church school ( nəbab bet , "reading house") learn to read by repeating each syllable in order, starting with the first consonant h : ha, hu, hi ... That is why the "alphabet" in Amharic is hahu .

Old Ethiopic had 30 consonants, and the syllabary had 202 elements (less than 30 × 7 because some consonants do not combine with all vowels). In modern languages, some others have been added to these symbols for those sounds that are not found in Old Ethiopic. So it is not surprising that the old Amharic wish for longevity sounds like this: Bäfidäl quṭr ədme yəsṭäwo - "Let Him give you the age according to the number of letters."

In modern languages, some others have been added to these symbols for those sounds that are not found in Old Ethiopic. So it is not surprising that the old Amharic wish for longevity sounds like this: Bäfidäl quṭr ədme yəsṭäwo - "Let Him give you the age according to the number of letters."

11. Matab (matäb)

Baptismal cord; metaphor for the Christian faith

Baptism. Miniature from a handwritten psalter. Ethiopia, 20th century © University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History The Amharic word matäb , which has found its way into many other languages of the Christian peoples of Ethiopia, is borrowed from Old Ethiopian (Ge'ez), a dead language that has survived as the language of worship in Ethiopia Orthodox Church. In Old Ethiopian this word ( maʕtab ) is derived from the verb ʕataba - "to mark with a certain sign, seal" (usually about God marking believers), and also "to make the sign of the cross". Accordingly, maʕtab in Geez means either “seal”, or “sign”, or “sign of the cross, symbol of the cross”. Apparently, it was from the general meaning of “sign” that the use of the word maʕtab arose to designate the subject that in Ethiopia is the main sign of the Christian faith. This object is a blue or black silk cord that is tied around the child's neck during baptism. Mateb is the sign of the adoption of Christianity. Cross (which the Ethiopians call mäsqäl , “crucifixion”, from the verb säqqälä , “raise up”, hence “crucify”) is a mandatory attribute of a priest, and a simple believer can do without it. You can, however, hang a cross on the mateb, but rather for decoration - several crosses can hang on the mateb, or some other small metal objects, such as a ring.

Accordingly, maʕtab in Geez means either “seal”, or “sign”, or “sign of the cross, symbol of the cross”. Apparently, it was from the general meaning of “sign” that the use of the word maʕtab arose to designate the subject that in Ethiopia is the main sign of the Christian faith. This object is a blue or black silk cord that is tied around the child's neck during baptism. Mateb is the sign of the adoption of Christianity. Cross (which the Ethiopians call mäsqäl , “crucifixion”, from the verb säqqälä , “raise up”, hence “crucify”) is a mandatory attribute of a priest, and a simple believer can do without it. You can, however, hang a cross on the mateb, but rather for decoration - several crosses can hang on the mateb, or some other small metal objects, such as a ring.

To renounce the Christian faith means “to break the matäb” ( matäb bäṭṭäsä ). And if they say about a person that he is "without mateba" ( matäb yälläš ), it means that he is dishonest and capable of betrayal (of course, this is an analogue of the Russian “there is no cross on him”).