How do you say lap dance in spanish

Lap%20dance | Traductor de inglés a español

lap%20dance

Estás viendo los resultados para lap dance. Si quieres ver los resultados de lap%20dance, haz clic aquí.

el lap dance

Diccionario

Ejemplos

Pronunciación

Frases

lap dance(

lahp

dahns

)

Un sustantivo es una palabra que se refiere a una persona, un animal, un lugar, un sentimiento o una idea (p.ej. hombre, perro, casa).

sustantivo

1. (sexual)

a. el lap dance

(m) significa que un sustantivo es de género masculino (p.ej. el hombre, el sol).

(M)

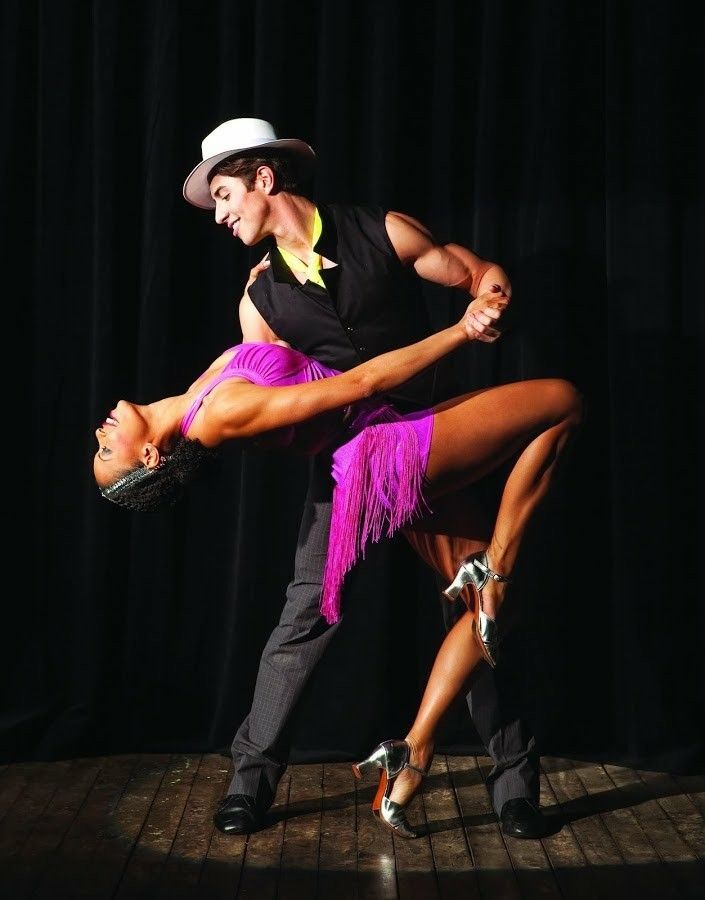

The script required the actress to give the actor a lap dance. El guion exigía a la actriz hacerle un lap dance al actor.

Copyright © Curiosity Media Inc.

Ejemplos

Frases

bailar el baile | |

el regazo sacar una vuelta a | |

I like to dance | me gusta bailar |

dance class | la clase de baile |

Do you like to dance? | ¿Te gusta bailar? |

I love to dance | me encanta bailar |

dance studio | el estudio de danza |

she likes to dance | le gusta bailar |

dance floor | la pista de baile |

dance club | la discoteca |

dance with me | bailar conmigo baila conmigo |

tap dance | el claqué bailar claqué |

I used to dance | bailaba |

do you dance | bailas |

we like to dance | nos gusta bailar |

dance team | el equipo de baile |

Do you want to dance with me? | ¿Quieres bailar conmigo? |

let's dance | bailemos |

I like to sing and dance | me gustar bailar y cantar |

they like to dance | les gusta bailar |

Traductores automáticos

Traduce lap%20dance usando traductores automáticos

Ver traducciones automáticas

¿Quieres aprender inglés?

¡Aprende inglés gratis!

Traductor

El diccionario de inglés más grande del mundo

Verbos

Conjugaciones para cada verbo en inglés

Vocabulario

Aprende vocabulario fácilmente

Gramática

Aprende todas las reglas de gramática

Pronunciación

Escucha miles de pronunciaciones

Palabra del día

afraid

asustado

inglés. com Premium

com Premium

¿Ya lo probaste? inglés.com Premium incluye:

Hojas de repaso

Sin anuncios

Aprende sin conexión

Guías de conversación

Aprende más rápido

Apoya inglés.com

If you want to learn how to give a lap dance, a private dance, and how [...] to use the power of seduction, then this is the site for you! panama-chicas.com panama-chicas.com |

Si quieres aprender a dar un baile de regazo, un baile privado y cmo [. utilizar el poder de la seduccin, entonces este es el sitio para ti. panama-chicas.com panama-chicas.com |

The software will give you accurate lap times, and many [...] additional essential features. sms-timing.com sms-timing.com |

El software le [...] proporcionar tiempos de vuelta precisos y muchos [...] ms aspectos esenciales. sms-timing.es sms-timing.es |

Off-the-track, you can do a lap round the bars, dance out your adrenalin [. at a music festival or a post-race rock concert. australia.com australia.com |

Fuera del [...] circuito, podr dar una vuelta por los bares, liberar adrenalina [...] en el festival de msica o asistir a un concierto [...] de rock despus de la carrera. australia.com australia.com |

This mission overlaps with UBW's community-focused [...] philosophy of using dance to give a voice to the marginalized, [...] she observed. america.gov america.gov |

Este objetivo coincide con la filosofa de UBW centrada en la

[. observ. america.gov america.gov |

When you dance you give the same importance [...] to leg movements and arm movements, do you believe in the total dancer concept? esflamenco.com esflamenco.com |

En tu baile das la misma importancia [...] a los brazos que a las piernas Defiendes el concepto actual de bailaora completa? esflamenco.com esflamenco.com |

I came back and

[...]

held him in my lap," she recalls, "to give him a little [. bit of water. unicef.org unicef.org |

Regres y lo puse sobre mi regazo, para darle un poco de agua. unicef.org unicef.org |

The style of dancing [...] in these clubs is to catwalk topless and lap dance. alixmodelos.com alixmodelos.com |

El baile que se estila en [...] estos clubes es baile de pasarela topless y lap dance. alixmodelos.com alixmodelos.com |

By the end of the school year, Stewart says, John

[...]

was snuggling on her lap and giving her hugs. 4children.org 4children.org |

Hacia el final del ao escolar, cuenta Stewart, John [...] se acurrucaba en su regazo y le daba abrazos. es.4children.org es.4children.org |

It's very important to see what [...] flamenco can give to modern dance and vice versa. esflamenco.com esflamenco.com |

Es muy importante ver lo que el [...] flamenco pueda exportar a la danza contempornea y viceversa. esflamenco.com esflamenco.com |

It's dance and more dance, we try to give each style a [. different colour and flavour. esflamenco.com esflamenco.com |

Es baile y baile, querindole dar a cada palo del flamenco [...] un color y una actitud. esflamenco.com esflamenco.com |

This is the third national laurel for San Martn, which holds the titles of 2007 and 2008, and now has frustrated the [...] possibilities for Len de Hunuco from becoming the first team within [...] the country to give the Olympic lap in a national [...] tournament . conmebol.com conmebol.com |

Se trata del tercer lauro nacional de la San Martn, que atesora los ttulos de 2007 y 2008, y que ahora frustr la posibilidad de Len de

[. Hunuco de convertirse en el primer equipo del interior [...] del pas incaico en dar la vuelta olmpica en un torneo [...] nacional. conmebol.com conmebol.com |

Even before babies can sit up on their own, they [...] can cuddle on your lap and look at board [...] books with black and white drawings or pictures of faces. 4children.org 4children.org |

Incluso antes de que los bebs puedan sentarse por s mismos, pueden [...] acurrucarse en su falda y mirar imgenes [...] de libros con dibujos en blanco y negro o fotos de rostros. es.4children.org es. |

The length of the lap may be changed to [...] accommodate the length of the mileage accumulation test track. eur-lex.europa.eu eur-lex.europa.eu |

La longitud de la vuelta puede modificarse [...] para adaptarse a la longitud de la pista de ensayo de acumulacin de kilometraje. eur-lex.europa.eu eur-lex.europa.eu |

If there is, the Americans come [...] whistling past one lap of the circuit ahead [...] of us whatever the event, to use a sports image. europarl.europa.eu europarl.europa.eu |

Por usar una metfora deportiva, los estadounidenses nos sacan, con

[. lo que sea. europarl.europa.eu europarl.europa.eu |

Many local bars (and restaurants) [...] offer the opportunity to give this Latin American dance hip-swinging tryout. martinair.com martinair.com |

Muchos bares (y [...] restaurantes) de la ciudad nos dan la oportunidad de probar este baile latinoamericano sacudiendo [...] las caderas. martinair.com martinair.com |

Dance" - Give another turn to the allies next to the dancer. fireemblemwod.net fireemblemwod.net |

Bailar" - Permite vailar para dar un turno ms a los [...] aliados cercanos. fireemblemwod.net fireemblemwod.net |

What does flamenco give to Spanish dance and vice versa? esflamenco.com esflamenco.com |

Qu aporta el flamenco a la danza espaola, y viceversa? esflamenco.com esflamenco.com |

We offer cooking and dance classes to give students another, [. more relaxed setting in which to socialize and study a different aspect of Spanish culture. eurekamadrid.com eurekamadrid.com |

Cursos complementarios de [...] cocina espaola y de baile con los que aprender [...] otro tipo de vocabulario. eurekamadrid.com eurekamadrid.com |

Between June 12 and June 17 each year, dancers [...] and musicians give life to the diablada or dance of the devils, a carnavalesque dance for expelling demons. thisischile.cl thisischile.cl |

Entre el 12 y el 17 de

[. demonios. thisischile.cl thisischile.cl |

Unfortunately, in many [...] cases, this guard dog has often emerged as nothing but a lap dog. europarl.europa.eu europarl.europa.eu |

Lamentablemente, en muchos [...] casos este perro guardin se ha comportado como un perro faldero. europarl.europa.eu europarl.europa.eu |

Otherwise, sit up straight in a chair,

[...]

holding your baby at breast level across your lap. usa.philips.com usa.philips.com |

De lo contrario, sintese derecha en una silla y [...] sostenga al beb en el regazo a la altura del pecho. philips.es philips.es |

You can gain a lot of lap time here with having [...] a confidence in your car. jaguar.com jaguar.com |

Aqu puedes ganar un [...] montn de tiempo de la vuelta si confas en tu coche. jaguar.com jaguar.com |

Seat younger children in your lap and encourage good listening skills. virtualpre-k.org virtualpre-k.org |

Siente a los [...] ms pequeos en su regazo y mustreles el arte [...] de saber escuchar. virtualpre-k.org virtualpre-k.org |

An overwhelming number of employees use a mobile phone, a lap-top, or a similar device to send or retrieve information for their work. eur-lex.europa.eu eur-lex.europa.eu |

Una abrumadora mayora de los trabajadores utilizan un telfono mvil, un ordenador porttil o un dispositivo similar para enviar u obtener informacin para su trabajo. eur-lex.europa.eu eur-lex.europa.eu |

On the racetrack, this reduction in wind resistance can make a

[. kawasaki.eu kawasaki.eu |

Esta reduccin en la resistencia al viento puede suponer una enorme diferencia en los [...] tiempos parciales de vuelta. kawasaki.es kawasaki.es |

Combined with the [...] everyday the dance allows us to constantly give a new meaning [...] to the unsatisfaction or frustration of [...] life, increasing the tolerance towards it. sentirtango.com sentirtango.com |

En combinacin con la cotidianeidad la danza nos permite resignificar constantemente [. la insatisfaccin o frustracin de [...] la vida, acrecentando la tolerancia hacia ello. sentirtango.com sentirtango.com |

We hope to give birth to tomorrow's dance for the future [...] needs of society to come ". harlequinfloors.com harlequinfloors.com |

La danza para las necesidades de la sociedad futura. harlequinfloors.com harlequinfloors.com |

Project title: DNA: Give birth and dance again ue2008. ue2008.fr |

Ttulo del proyecto: ADN: Parto y Danza de nuevo ue2008.fr ue2008.fr |

Sheets of extruded polystyrene (XPS) of the highest quality (Styrodur by BASF) for insulation, green in colour and with tongue and groove or half-lap joint for easy installation and thermal bridge breaking. grupovalero.com grupovalero.com |

Planchas de poliestireno extruido (XPS) de la ms alta calidad (Styrodur by BASF) para aislamiento, de color verde y machihembrado o con media madera para su fcil colocacin y rotura de puentes trmicos. grupovalero.com grupovalero.com |

Dance and theater groups daily give demonstrations of the cultures of their towns and regions, along with presentations of the mission and witness of the churches and organizations [. from which they come. wcc-assembly.info wcc-assembly.info |

El Caf Teolgico que funciona en el predio de la Pontificia Universidad Catlica de Ro Grande do Sul ofrece un buen espacio para el debate teolgico y el encuentro ecumnico wcc-assembly.info wcc-assembly.info |

We animals

We wanted more. They beat the table with fork handles, banged spoons on empty plates: they demanded more. We wanted more volume, more riot. They twisted the knob of the TV to the point that the ears hurt from angry screams. When the radio played, we wanted more, more music - we wanted rhythm, we wanted rock. We wanted to build muscle on thin arms. We had bird bones, hollow and light, and we wanted to thicken, to become heavier. We were six grasping hands, six stamping feet; we were brothers, boys, three little kings waging an eternal war for more.

Do not self-medicate! In our articles, we collect the latest scientific data and the opinions of authoritative health experts. But remember: only a doctor can diagnose and prescribe treatment.

But remember: only a doctor can diagnose and prescribe treatment.

When it was cold, we fought among ourselves for blankets until the fabric was torn in the middle. And when it got really cold, when the breath flew out in frosty clouds, Munny crawled into the same bed with me and Joel.

"Self-heating," he said.

- Self-heating, - we agreed.

We wanted more - flesh, blood, warmth.

When we fought, boots, garage tools, tongs, pliers were used - we grabbed and threw everything that came to hand; we wanted more fragments, more broken plates. We wanted to destroy.

And when Paps came home, he flogged us. From the belt, our small round buttocks turned red, burned. We knew that there was something on the other side of the pain, on the other side of the spanking. A sharp heat rose from the buttocks, from the hips, the flames devoured the brains, but we knew there was something else, the place where Paps was leading us through it all. They knew because he was methodical, accurate, because he did his job slowly. He awakened us; through the whipping fire, he led us somewhere farther away, where there is no quick way to get to.

They knew because he was methodical, accurate, because he did his job slowly. He awakened us; through the whipping fire, he led us somewhere farther away, where there is no quick way to get to.

And when our father left, we ourselves wanted to be fathers. We were looking for living creatures. They kneaded mud by the stream, catching snakes and frogs. They took robin chicks out of the nests. We liked to feel how a tiny heart beats, how wings flutter. We brought the tiny physiognomy of the creature to our face.

— Who is your parent? they asked, and then they threw the animal into a shoebox.

They always demanded more, always rummaged around, fumbled in search of more. But sometimes there were other moments, quiet, when our mother slept, slept off after a sleepless day and a half, and any sound - a creaking staircase, a door, stifled laughter, any voice in general - could wake her up, motionless crystal mornings, when we wanted to protect her, this a confused dupe who stumbles at every step, our mother with her effusions, with her aching back and headaches, with her tired-tired look, this transplanted Brooklyn plant, a mother who is strict only in words, unable to tell us without tears that loves us, with her stupid love, with her beggarly love, with her warmth, there were mornings when the sun found cracks in our blinds and crossed the carpet in clear stripes, quiet mornings when we breakfasted on oatmeal, and then lay on our stomachs with colored crayons and paper, with glass balls that they tried not to hit once, mornings when our mother was sleeping, when there was no smell of sweat, breath, or mold, when the air was still and light, mornings when silence was our secret game, our gift and our only achievement - these mornings we did not want more, and the less the better: less burden, less work, less noise, less father, less muscles, skin, hair. We didn’t want anything at all, if only so, if only so.

We didn’t want anything at all, if only so, if only so.

All three of us were sitting at the kitchen table in raincoats, and Joel was smashing tomatoes with a small rubber mallet. We saw this on TV: a man with an unbridled mustache is chopping vegetables with a mallet, and people in transparent plastic ponchos get pulp in their faces and are insanely happy about it. Our goal was to smile like them. We felt the pop and splatter of the spraying tomato slurry; it flowed down from the walls, splashed our cheeks and foreheads, glued our hair together. When the tomatoes ran out, we went to the bathroom and got tubes of mother's creams from under the sink. Then they took off their cloaks and positioned themselves so that the white cream, after the blow of the mallet, was everywhere: in the folds of tightly compressed eyelids, in the convolutions of the ears.

Mother came down to the kitchen, wrapping her dressing gown, rubbing her eyes and asking:

— My God, what time is it, I wonder?

We told her it was eight-fifteen, and Ma said: damn, she still didn’t open her eyes, she only rubbed them harder, then repeated louder: damn, she grabbed the kettle, banged it on the stove and shouted:

— Then why don’t you at school?

It was eight-fifteen in the evening, and besides, it was Sunday, but no one began to tell her this. She worked the night shift at the brewery up the road from our house, and sometimes she got lost. She could wake up at any time and get up without thinking anything, confusing days, confusing hours, she could order us to brush our teeth, put on pajamas and go to bed in the middle of the day; or we half-asleep came to the kitchen in the morning, and she, pulling baked meat out of the oven, asked: “What's wrong with you guys? I call you, I call you for supper, but you don't go."

She worked the night shift at the brewery up the road from our house, and sometimes she got lost. She could wake up at any time and get up without thinking anything, confusing days, confusing hours, she could order us to brush our teeth, put on pajamas and go to bed in the middle of the day; or we half-asleep came to the kitchen in the morning, and she, pulling baked meat out of the oven, asked: “What's wrong with you guys? I call you, I call you for supper, but you don't go."

We learned not to correct her, not to lead her out of error: this could only make things worse. Once, when we didn't understand it yet, Joel refused to go to the neighbors to ask for a pack of butter. It was almost midnight and she was about to bake a cake for Manny.

"Ma, you're out of your mind," Joel said. - Everyone is sleeping, and he doesn't even have a birthday.

She stared at the clock for quite some time, then turned her head—quickly, back and forth—and finally stared at Joel; she bored into his eyes with her gaze, as if she wanted to reach the depths of his brain. The mascara with which she had lined her eyelashes was all smeared, her coarse hair was thickly blackened, curling around her face and falling in a tangled mass from behind. She was like a raccoon seen rummaging through the garbage: caught off guard, dangerous.

The mascara with which she had lined her eyelashes was all smeared, her coarse hair was thickly blackened, curling around her face and falling in a tangled mass from behind. She was like a raccoon seen rummaging through the garbage: caught off guard, dangerous.

“I'm sick of my life,” she said.

Joel cried when he heard this, and Munny hit him hard on the back of the head.

“Who pulled you by the tongue, you asshole,” he hissed. “Fuck it, it’s my birthday.”

After that, we no longer resisted anything that came into her mind; we lived like in a dream. Sometimes at night, Ma would put us in the car and we would go to the grocery store, to the laundromat, to the bank. We stood behind her and giggled when she tried to open the locked door or, cursing, shook the heavy bars.

Now, finally seeing the mixture of tomato pulp and ointment running down our faces, she opened her mouth in surprise. The eyes widened, then narrowed. She called us to her and gently ran her finger along each cheek, cutting through the slimy slurry. And again she inhaled convulsively with her open mouth.

The eyes widened, then narrowed. She called us to her and gently ran her finger along each cheek, cutting through the slimy slurry. And again she inhaled convulsively with her open mouth.

“That’s exactly how you got out of me,” she whispered. - Just like that.

We groaned in unison, but she continued to talk about it - about the mucus that enveloped us, about how Manni struck her when she was born with a hairy head without a single bald spot. First of all, she counted everyone's fingers and toes.

"I wanted to make sure they didn't forget anything inside," she explained, and we all started to make fake vomiting sounds.

- Now do it for me.

— What? we asked.

- So that I was born.

"Ran out of tomatoes," Munny said.

— Take the ketchup.

I gave her my raincoat because mine was the cleanest, and we told her not to open her eyes under any circumstances until we said she could. She knelt down and rested her chin on the table. Joel flung a mallet over her head, Munny aimed the hole of the ketchup tube between her eyes.

She knelt down and rested her chin on the table. Joel flung a mallet over her head, Munny aimed the hole of the ketchup tube between her eyes.

- On the count of three, - we said and shouted out the numbers in turn - mine came last. Sucking in air through their teeth, everyone took the deepest, longest breath they could. Each had clenched fists, his face was wrinkled into a tight grimace. They sucked in a little more air, their chests opened up. The room became like a balloon when you blow into it, blow it, blow it, and it's about to burst.

- Three!

The beater split the air. Mom screamed, slid down to the floor and remained lying - eyes wide open, ketchup everywhere, looking as if she had been shot in the back of the head.

- Mommy is born! we shouted. - Congratulations!

We ran to the kitchen cabinet, pulled out the largest pots, heavy ladles and rumbled with might and main, dancing around my mother's body and throat:

- Happy birthday! . . Happy New Year! .. Time is zero-zero-zero, here what time is it for you!.. An unprecedented minute!.. The best moment in your life!

. Happy New Year! .. Time is zero-zero-zero, here what time is it for you!.. An unprecedented minute!.. The best moment in your life!

We came from school and saw that Paps filled the whole kitchen with him: he cooked, listened to music and was in a great mood. He sniffed the steam from the pan, clapped his hands and rubbed them vigorously. His eyes were wet, they sparkled with crazy life. He turned up the volume of the stereo - it sounded mambo performed by Tito Puente.

“Look,” he said, and, wearing slippers, in a flying bathrobe, gracefully pirouetted. With a shiny, greasy metal spatula he swung to the beat of the bongo drums.

We stood at the kitchen door, huddled together, laughed, really wanted to join, but waited for an invitation. Paps tapped his soles on the linoleum towards us, grabbed us by flaccid elbows and, pulling, dragged us to the "dance floor". We began to twist our clenched fists in front of us and wag our hips to the sound of the trumpet. He grabbed one after the other by both hands, dragged him along the floor between his legs and let them jump out from that side. Then, dancing, we followed him in single file around the kitchen.

He grabbed one after the other by both hands, dragged him along the floor between his legs and let them jump out from that side. Then, dancing, we followed him in single file around the kitchen.

It was hot on the stove: pork chops were fried in their own fat, rice in Spanish was boiling, tapping the lid of the pot. The air was thick with steam, spices, and music, and the only small window above the sink was fogged up.

Paps turned the stereo knob again - it became so loud that, if we screamed at the top of our voice, no one would have heard, so loud that it seemed that Paps was far away and could not reach him, even though he was all there, right in front of us . Then he took a can of beer from the refrigerator, and we followed with our eyes the trajectory of the can to his lips. We saw how many empty ones were standing behind him on the cutting table, and exchanged glances. Munny rolled his eyes and started dancing again, Joel and I too, moving in single file again, only now Munny was daddy goose and we followed him.

- Well, now how rich! Paps shouted to us, drowning out the music with his powerful voice. We went on tiptoe, with our noses up and our little fingers pointing upwards.

"No, you're not rich," Paps said. - Well, now like the poor.

We knelt down, clenched our fists, extended our arms to the sides; we shrugged our shoulders and threw back our heads, wild, free, desperate.

- And you are not poor. Well, now as white.

We began to move like robots, stiff and angular, not even smiling. Joel was the most convincing, we've seen him train in our room before.

- No, you are not white! Paps shouted. - Well, now like Puerto Ricans.

We paused, gathered our courage. And they gave out the best mambo they could, trying to be serious, move smoothly, feel every blow with their feet and, in addition to blows, feel the rhythm. Paps looked at us for a while, leaning against the cutting table and taking long sips from a beer can.

Paps looked at us for a while, leaning against the cutting table and taking long sips from a beer can.

"You are mutts," he said. “Not whites and not Puerto Ricans. Look how the pure breed dances, how we dance in the ghetto.

He spoke every word loudly, shouting over the music, and it was not clear whether he was angry or just having fun.

He began to dance, and we tried to see what distinguishes him from us. He pursed his lips, put one hand on his stomach. The arm is bent at the elbow, the back is straight, but for some reason there was emancipation in his every movement, there was freedom, there was confidence. We tried to look at his feet, but something in the way they scurried about, the way they weaved their pattern, something in his whole figure pushed our eyes to his face, to his wide nose, to dark half-closed eyes and pursed lips, half angry, half smiling.

“This is your legacy,” he said, as if this dance could tell us about his own childhood, about what life smells and feels like in cheap apartment buildings in Spanish Harlem, about Red Hook residential areas, about dances, about city parks, about his Paps, how he beat him, how he taught him to dance; as if we could hear the sounds of Spanish in his movements, as if Puerto Rico is a man in a bathrobe, taking another can of beer from the refrigerator and bringing it to his lips - head thrown back, legs still dancing, feet still drawing their pattern, perfectly in tune.

In the morning we stood at the door of the room side by side and looked at Ma - she was sleeping with her mouth open, and we could hear the air, gurgling, with difficulty passing through her throat clogged with saliva. Three days ago, she returned home with swollen purple cheeks. Paps carried her into the house and laid her on the bed, then stroked her head and whispered in her ear. He told us that the dentist hit her on the cheeks when she passed out after the injection: so, they say, they loosen her teeth before removing them. Since then, Ma has been lying in bed all the days, in front of the bed on the floor there were bottles of painkillers, glasses of water, half-drunk mugs of tea, and bloody napkins were lying around. Paps forbade us to enter the bedroom, and for three days we obeyed, only watched her breathing from the doorway, but today we could not stand it.

Approached her on tiptoe and lightly touched her bruises with your fingers. Ma felt it, muttered something, but did not wake up.

Ma felt it, muttered something, but did not wake up.

I was seven years old that day, so it was winter, but the window, drawn by the curtain, shone brightly, like spring. Munny went to the window and wrapped himself in the curtain, leaving only his face. One Sunday, we begged Ma to take us to church for a service, and there we saw painted men in hoods with folded palms and upturned eyes.

“Monks,” Ma explained to us then. “They comprehend God.

“Monks,” Munny whispered now, and we understood. Joel wrapped himself in a sheet, which she knocked to the floor in a dream, I in another curtain, and, like monks, we froze, only we wanted to comprehend Ma with her black matted hair, closed eyes, swollen jaw. We looked at her little body under the covers - she twitched, she moved her leg - and her chest rose and fell evenly, rose and fell.

When she finally woke up, she called us handsome.

- My beauties, my babies - were the first words in three days that her unfortunate mouth uttered, and it turned out to be too much; we turned away from it. I pushed my hand up to the glass, suddenly embarrassed, needing something to cool me off. It sometimes happened with Ma and me: I had to cuddle up to something cold and hard, otherwise my head would spin.

"It's his birthday," Munny said.

“Happy birthday,” Ma said in a voice tinged with pain.

"He's seven," Munny said.

Mom nodded slowly and closed her eyes.

“Seven means he will leave me now,” she said.

— How is it? Joel asked.

- When the boy is seven, he leaves me. So it was with you two. Closes from me. That's what big boys do, seven-year-olds.

I already pressed both palms against the glass, caught the cold and pressed it to my cheeks.

- Not me.

“They have changed,” Ma said, turning her head towards me. - They began to evade when I wanted to caress them, they could not sit quietly on my lap. I had to let them go, to make my heart hard from soft. They would only break everything, only fight.

The brothers were embarrassed, but, strangely, they became proud - such was their appearance. Munny winked at Joel.

- Well, no, - he objected, - we are not like that.

- Is it? Ma asked.

"I don't want to break anything," I said. — I want to comprehend God and never get married.

“Good,” said Ma. “Then you will always have six.

"What nonsense," Joel said.

Ma slowly raised her hand to show that that was enough.

- Will you get up today? I asked.

— How do I look?

"Purple," I said.

"Crazy," Joel said.

— Torn to pieces, Munny said.

"But it's your birthday," Ma reminded me.

- But it's my birthday.

She pushed the blanket to her waist and brought her hands to her face, gently guarding her cheeks, as if someone's hand could appear in the air at any moment; then she sat down, then put her feet on the floor, then stood up in her long green T-shirt, from under which her bare legs stuck out, thin, rather thin, with painted nails.

There was a mirror with a brass handle on the chest of drawers, and as soon as Ma raised it to her face, tears welled up in her eyes - they stood up and were in no hurry to flow down. Ma was surprisingly able to keep tears on her eyelids for a surprisingly long time; there were days when she walked like this for hours, not letting them slide. On such days, she traced objects with her finger along the contour or sat with the phone on her knees, was silent, and it was necessary to call her three times for her to pay attention to you.

Now Ma was holding back her tears and looking at her ugliness. The three of us had already begun to move towards the exit, and then she called me over, said that she wanted to talk about how to stay six years old, but apart from these words, I heard little from her: she just looked in the mirror and looked, turning chin at different angles.

— What did he do to me? she asked.

“He hit you in the face,” I said, “to loosen your teeth.

I jumped at the sound of breaking glass. In an instant, the heads of the brothers rose again in the door, a smile on their faces from ear to ear, they look at Ma, then at me, then at the fragments of the mirror, then at the wall where she launched it, then at Ma, then at me.

Ma's hands were again protecting her cheeks, her eyes were closed. When Ma spoke, she spoke each word slowly and distinctly.

- Do you think it's funny when a man hits your mother?

The brothers stopped smiling, scowled, and disappeared through the door again.

I went to the window and wrapped myself in the curtain again, resting my forehead against the window pane. The snow and the white sky, reflecting the light, drove him back and forth, up and down; light particles stuck in frosty patterns on the window. It was too bright outside to focus on anything. I opened my eyes as wide as I could, they were burned with light, and I thought that it would be good to go blind, because they say that if you look directly at the sun with all your eyes and do not take them away, you will go blind - but, no matter how hard I tried, couldn't go blind.

Ma sat on the edge of the bed, breathing loudly and slowly, she forgave me. She called me to her knees, I went up, sat down, and we began to breathe together. Then Ma sang my favorite song about a woman with feathers and oranges and about Jesus Christ walking on water. My head reached her right up to her shoulder, but she still rocked me, rocked me, and where she forgot the words, she simply purred a motive.

“Promise me,” she said, “promise that you will always have six.

— How is it?

- Very simple. You are not seven now, but six plus one. In a year it will be six plus two. And so forever.

- Why?

- If you are asked how old you are, and you answer: I am six plus one, plus two or more, this will mean that even though you have grown up, you still remain your mother's boy. And if you remain my boy, then I will never lose you, you will not start dodging me, you will not be slippery, unyielding, and I will not have to make my heart hard.

- Did you stop loving them when they were seven?

"Don't be a fool," said Ma. — She pulled my hair back from my forehead. - It's just that big boys are loved differently than little ones: they harden, and one must be firm with them. Sometimes I get tired of it, that's all, and you - I don't want you to leave me, I'm not ready for this.

Then Ma leaned down and whispered in my ear even more about why she needed me at the age of six. She whispered everything about how much she needs me, that there is no softness anywhere, only Paps and boys who turn into paps. And not so much the tender words themselves, but the moist voice with a touch of pain, the warm proximity of her bruises - that's what ignited me.

I turned to her, saw swollen cheeks, dirty purple skin with yellowness around the edges of the spots. These bruises looked so sensitive, so soft, vulnerable - and inside me, in the very depths, this trembling flashed, this spark, a secret unholy trembling, tingling went down my chest, it moved along the arms, reached the palms. I grabbed her by both cheeks and pulled her towards me to kiss.

A sharp, swift pain darted into her eyes, turning the pupils into large black circles. She tore her face away from mine and pushed me away, threw me to the floor. She scolded me, scolded Jesus, and the tears rolled down, and I became seven.

She scolded me, scolded Jesus, and the tears rolled down, and I became seven.

Fragment of the novel courtesy of Corpus

The novel "We the Animals" by Justin Torres will be published by Corpus in January 2013

Read Orchid Spell - Carlos Fuentes

Carlos Fuentes

Orchid Spell

- Look, winter has come.

From behind the heavens, a stream of bright blades poured into Panama, which, having wounded the earth in the adjacent streets, rushed to Via España. At the edge of the highway, raging rivers spilled in confusion in breadth, involuntarily shy before the hot thirst for asphalt. The distant breath of the city and the surf of its noises were dissolved in the vapors of the sidewalks, in the cosmos of palm trees, in the crowds of human bodies under the awnings.

A womb light dawned, yellow as clay in the arms of rain. When Muriel awoke, it was already noon. The open windows tapped rhythmically on the third syllable from the end, heavy sheets piled up on the body. The shadows from the legs of the table crawled somewhere, silence swallowed the man's cough. Ana had already left, perhaps returning by evening, soaked to the marrow in her weightless cocoon.

The shadows from the legs of the table crawled somewhere, silence swallowed the man's cough. Ana had already left, perhaps returning by evening, soaked to the marrow in her weightless cocoon.

Muriel shrugged his shoulders and clasped his head in his hands. In a matter of fractions of a minute, green midges painted the gray contours of his torso, but the wave of his hands moved the air. Around - emptiness. Only in the distance could be seen the hills, truncated by the dark knife of a rainy day. No bird, no prophetic sign. Only time in a tangled mane of lightning. He began to lazily look for a poetic meter, for this country is full of rhythms, rhythms are inalienable, like your own legs ...

Alanje, Guarare, Macaras, Arrayhan,

Chiriqui, Sambu, Chitre, Penome,

… Chikan, Cocoli, Portogan… This rhythm always saved him.

When the downpour subsided, Muriel got out of bed, wiping his damp forehead. And went to the toilet for shoes. There was brown mold on them, just like books, swollen and unwilling to be read. There were still wet ice cubes on the plate. He put them on his chest, pressed hard with his palm, but the cough returned again. Under the windows, the jasper shrub again spread its red-veined foliage. And there the sun and unhurried human fuss revived again; Central Street pulsed languidly, a bifurcated line of life, squandered by frayed papers in Santa Ana shops, drowned in the juice of squeezed lemons, a line that continued along both banks of the Canal Zone and branched to infinity. Random noises filled Muriel's head, sweat dripping down his back like a drip.

There were still wet ice cubes on the plate. He put them on his chest, pressed hard with his palm, but the cough returned again. Under the windows, the jasper shrub again spread its red-veined foliage. And there the sun and unhurried human fuss revived again; Central Street pulsed languidly, a bifurcated line of life, squandered by frayed papers in Santa Ana shops, drowned in the juice of squeezed lemons, a line that continued along both banks of the Canal Zone and branched to infinity. Random noises filled Muriel's head, sweat dripping down his back like a drip.

At that very moment, Muriel felt an itch in his tailbone. He scratched it with his nails, but the itching got worse. Something else was also felt ... some kind of bump that seemed to have nothing to do with the body. The desire to be healed by sorcery or medicine got him out of bed. Who knows what kind of tropical thing it is, capable of appearing anywhere and created from living tissue, but, like everyone else here, in the tropics, with a dead soul and stone flesh! A day was coming, a day that concealed darkness and death in its joyful grin. Rather, the night would come to return to the clear covenants, to catch the light and pour it into rhythms. Constancy is inherent in the night: the bewitching cumbia [1], the monotonous tambourine, the melodic clatter of glasses and the incessant clanging of glasses fetter that eternal movement that comes to life in silence under the sun. At night there is a time for goodbyes.

Rather, the night would come to return to the clear covenants, to catch the light and pour it into rhythms. Constancy is inherent in the night: the bewitching cumbia [1], the monotonous tambourine, the melodic clatter of glasses and the incessant clanging of glasses fetter that eternal movement that comes to life in silence under the sun. At night there is a time for goodbyes.

Dampness be damned! Fingers slid over the blister, but could not catch it, comb it ... And the blister grew, grew, until it burst and became a wet nostril rosette. Muriel stripped naked and, turning his head, tried to see his back in the mirror. It was no longer possible to give free rein to the nails - and look, you could damage the yellow-violet petals, the metallic coating of pollen, the juicy stem. A beautiful orchid blossomed there, scornful of symmetry, lazily indifferent to the place of its appearance.

Tailbone Orchid. He felt that this still life was sucking him, prickling with needles, growing into the depths of his body, turning brains into stones, and eyes into their blind fragments.

But everyday problems also arose that needed to be resolved. How to wear pants now? What to do with a flower that has become part of the body? Moist fluids rushed from the core of the orchid to the solar plexus, firmly connecting the life of the flower with its own life. There was no other way out than to cut a round hole in the back of the pants - and let the orchid flaunt in front of everyone. With such an ornament, it was not a shame to go out into the street: there were their own norms of prestigious decoration. Probably, the long months of the Carnival mixed all the concepts of decency and behavior, and this was seen as just a funny joke. And so the orchid floated, swaying gracefully, under the timid glances of Hindu merchants, between the hard skirts and purple shirts of the Negroes from Caledonia, never alarming anyone except one snake. Hours of exposure to the heat did nothing to dampen the lovely freshness of the flower. In a tavern, Coco Pelao Muriel splashed her with liquor. The flower turned pale, but absorbed the moisture with pleasure; its petals pressed against the man's buttocks, pushed him out of the tavern and sent him to the doors of Happyland [2].

The flower turned pale, but absorbed the moisture with pleasure; its petals pressed against the man's buttocks, pushed him out of the tavern and sent him to the doors of Happyland [2].

That evening, Muriel danced with great enthusiasm. The orchid trembled in time with the music, its juices poured into the dancer's heels, rose to the main nerve, rocked his knees, forced him to choke from a dry, furious cry. From the root of the orchid came thick moaning waves like some kind of spell. Chimbombo! Chimbombo!

Chimbombo! Close my wounds, fold my hands,

Erendoro! Heal my crotch, stop my time

Give me the future

Give me back my tears oh Chimbombo

Quiet my laughter, drive away my fear,

Give me peace,

Let me speak Spanish,

Alambobb,

Kill my rhythms so I can grow,

Connect the shores, so I can breathe,

Fill the channel with earth and flowers,Don't sell me for an empty moon,

Build bridges with my nails,

Scrape off my star tattoo,

Chimbombo!

This is how the orchid lamented, and the people – impudent sailors, tourists, lustful mulattos – marveled at the sad beauty of the flower, its alluring swaying, changing shades with each new dance. The orchid has become a treasure grown in the greenhouse of a falcon, but! ... If it bloomed there, why not grow other, unique specimens, again and again, endlessly different types of orchids, flowers that would be exported in refrigerators on airplanes to thousands of cities where there still remains at least one single woman, greedy for exquisite flattery.

The orchid has become a treasure grown in the greenhouse of a falcon, but! ... If it bloomed there, why not grow other, unique specimens, again and again, endlessly different types of orchids, flowers that would be exported in refrigerators on airplanes to thousands of cities where there still remains at least one single woman, greedy for exquisite flattery.

Muriel jumped out of Happyland and ran headlong home. Ana hasn't returned yet. No matter. He quickly undressed and took out a knife. Without hesitation, with one blow, he cut off the orchid from himself and put it in a glass. A short stump was green on the tail.

The first flowers will go for twenty dollars apiece! All that remained was to stretch out on the bed and wait for a new orchid to bloom every day from twelve to two. Or maybe several will grow at once - by forty, eighty, one hundred dollars daily.

But all of a sudden, for no apparent reason, a sharp splintered bough came out in the place of the cut Flower.

..]

..]

..]

..]

..]

comunidad de utilizar la danza para dar voz a los marginados, [...]

..]

comunidad de utilizar la danza para dar voz a los marginados, [...]

..]

..]

..]

..]

..]

..]

4children.org

4children.org ..]

facilidad, una vuelta de ventaja en [...]

..]

facilidad, una vuelta de ventaja en [...]

..]

..]

..]

julio de cada ao, bailarines y msicos dan vida a la diablada, danza carnavalesca para expulsar a los [...]

..]

julio de cada ao, bailarines y msicos dan vida a la diablada, danza carnavalesca para expulsar a los [...]

..]

big difference in lap times.

..]

big difference in lap times.  ..]

..]

fr

fr ..]

..]