How do russian dancers float

Meet Russia's Gravity-Defying Answer to the Rockettes

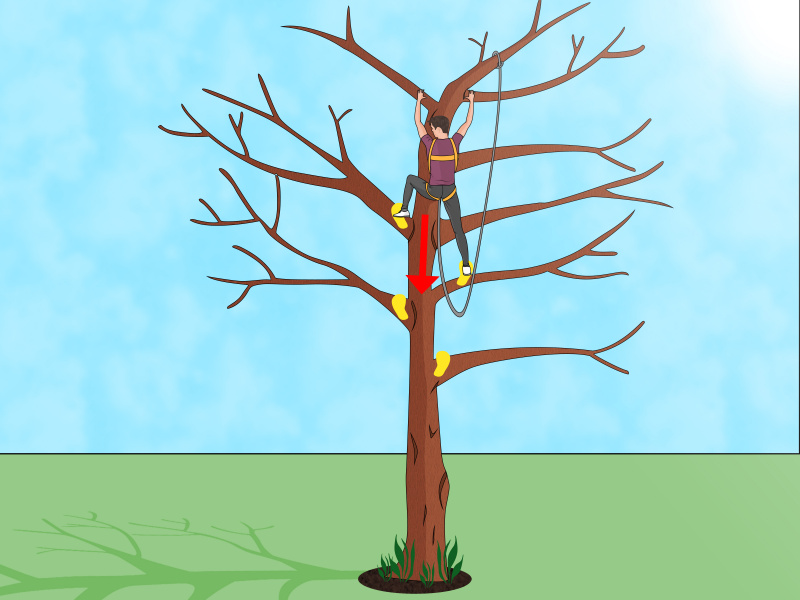

Manuel Palomino Arjona via FlickrOn a dimly lit stage, dozens of cloaked figures rise in unison under a somber, blue glow. As the spotlight grows brighter, the dancers are revealed; all unshakeable smiles and sparkles in their conical gowns that seemingly glide – no, float – across the stage like a life-sized music box. It’s enchanting, it’s eerie, and it’s kind of Russia’s answer to the Rockettes: the Berezka Dance Ensemble. Words don’t do these ladies’ footwork sorcery justice, so first things first, have a look:

Unreal, right? The dance, also spelled “Beryozka”, was invented in 1948 by Russian ballerina and choreographer Nadezhda Nadezhdina and literally means “little birch”, as the women would usually dance holding birch twigs. Today, it endures as one of Russia’s most iconic dance troupes, but Nadezhda was always quick to say that this wasn’t your average folk dance – this was the dance of the future. “Beryozka’s dances are not folk dances,” she said, “They are dances whose source is the creative work of the people. But composed by me”.

As with everything in the USSR, the prevailing norms favoured the work of the working class group over the individual. And the new Soviet woman, as exemplified through the Berezka dancers, was yet another highly polished team player with an evergreen smile. As Daniel Jaffé explains in Historical Dictionary of Russian Music, “there was a drive against vulgar ‘gypsy’ dances, waltzes, and tap dances associated with the decadent West and America in particular”.

The dancers in the 1970s. Manuel Palomino Arjona via FlickrThus, while the first of Nadezhda’s dancers were young farm girls from the current Tver region, they shuffled around the stage in silence to intricate dance patterns that felt much less folk-y and a lot more like life-sized Packman. It was unprecedented blend of old and new, with elements of the 1,000-yr-old folk art form, khorovod, which calls for circle dancing. “The khorovod is characteristic of all Slavic peoples,” Nadezhda told The New York Times on tour in 1972, “Its roots go back to pagan times. The circle represented the sun and the khorovod was danced to the god of the sun, Yarila”

It was unprecedented blend of old and new, with elements of the 1,000-yr-old folk art form, khorovod, which calls for circle dancing. “The khorovod is characteristic of all Slavic peoples,” Nadezhda told The New York Times on tour in 1972, “Its roots go back to pagan times. The circle represented the sun and the khorovod was danced to the god of the sun, Yarila”

Come 1951, they were so popular that the crowd literally swelled out of the building during their show at the Stockholm Music Academy. Above all, their ‘gliding’ dance style sent a fierce new message: the USSR is here, and it’s unbreakable. Same look, new ‘tude.

The key to how the dancers float has also remained a bit of a mystery to anyone outside the ensemble. “That’s a secret of the firm,” Nadezhda told the NY Times in the same interview, saying that “Not even all our dancers can do it,” she said. “You have to move in very small steps on very low half‐toe with the body held in a certain corresponding position. ”

”

Manuel Palomino Arjona via Flickr

Most impressively, Nadezhda’s troupe garnered praise both in and outside of the USSR throughout her life. In 1950, she won her country’s prestigious Stalin Prize; then, in 1959, she was awarded the Joliot-Curie Gold Medal by the World Peace Council. In that sense, Berezka was pretty amazing at finding a way to glide in and out from behind the Iron Curtain.

Russian Dancers Captivate Audience With Magical Floating Technique

Ah, the Russians and their rich culture. The knowledge we have of the stunning, populous nation includes their significant contribution to literature (“Anna Karenina”, “War and Peace”, “Crime and Punishment”), ballet (the Bolshoi Ballet and the Mariinsky Ballet), classical music (Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Alexander Borodin, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov), and painting (Andrei Rublev, Ilya Repin, Valentin Serov).

Add to that our general idea of their breathtaking geography, colorful folk costumes, and captivating scenery.

Source:

Pexels

If you are deeply interested in Russian culture and wish to explore more, you can start by watching remarkable performances that showcase the traditions of the nation, particularly dance.

Their folk dances, for instance, promise so much for the audience.

Source:

Pixabay/delo

You should know that there is more to Russian dance than the classic squat work, stomping, and split jumps.

When you look beyond the steps, you’ll notice that costumes are always intricately designed, with details highlighted beautifully by the dancers’ movements.

Source:

Pixabay/Ana Krach

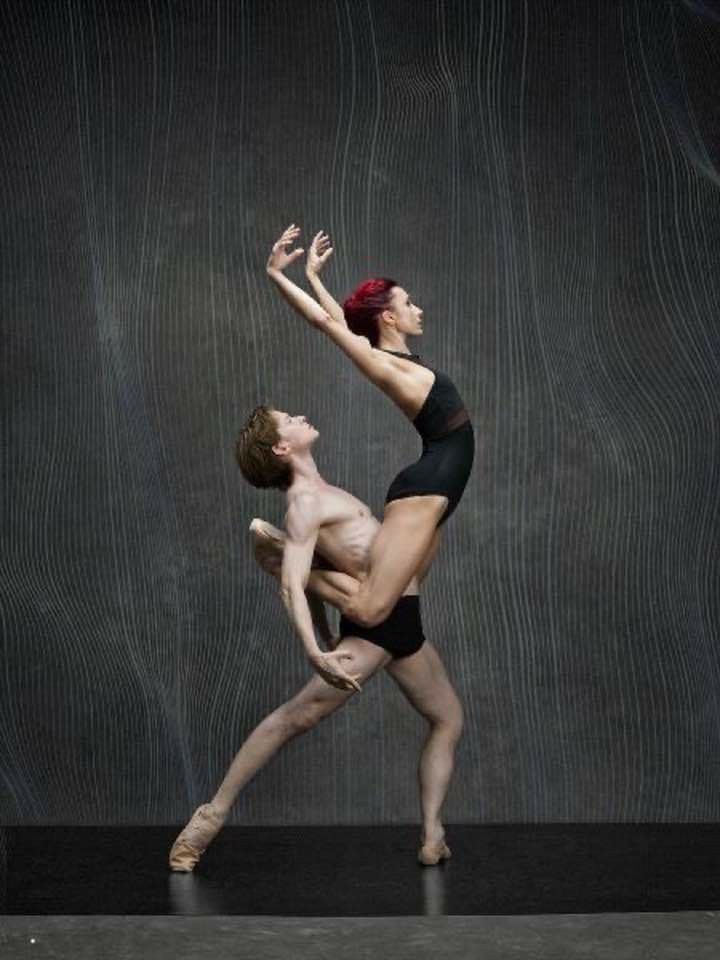

Take this number by Beryozka (or the Berezka Dance Ensemble), a troupe of female dancers founded by Nadezhda Nadezhdina.

The group is known for performing in striking long gowns and demonstrating movements that make it appear as though the dancers are floating. While their dances are generally considered part of Russian folk dancing, the founder and choreographer explains,

While their dances are generally considered part of Russian folk dancing, the founder and choreographer explains,

“Beryozka’s dances are not folk dances. They are dances whose source is the creative work of the people. But these dances are composed by me.”

Source:

YouTube Screenshot

Amazing as the floating illusion is, one will be surprised to know that not all the dancers in the group can actually do it. Nadezhdina adds,

“You have to move in very small steps on very low half‐toe with the body held in a certain corresponding position.”

Source:

YouTube Screenshot

The first part of their performance already gives the audience an idea of just how incredible this group is. Watch as they seem to float slowly and gracefully in a circle.

Source:

YouTube Screenshot

The dance is nothing short of enchanting but as you watch closely, you won’t be able to help but wonder just how much work goes into achieving the floating effect the dancers execute so flawlessly.

How many tiny steps done in quick succession does it take to make the audience believe that they’re simply waltzing on air from one direction to another?

The dedication it takes to produce such a magical piece will surely deepen your admiration for the Russians and their culture.

Source:

YouTube Screenshot

Wearing head pieces that match the vivid color of the long dresses, props in hand, the dancers of Beryozka grace their audience with a number that simply cannot be mirrored just like that

Despite the complicated work that goes behind the dance, the women of the dance troupe make it seem so effortless with their dainty movements and charming smiles.

Source:

YouTube Screenshot

Watch out for the incredible way they seem to float quickly into a tighter circle, like the closure of a flower.

Prepare to be entranced by the talented women of Beryozka as they showcase Russia’s culture wonderfully with their floating folk dance.

Please SHARE this with your friends and family.

Voluspa / Astrid

LiveScience

To learn more read our Editorial Standards.

Alissa Gaskell is a contributor at SBLY Media.

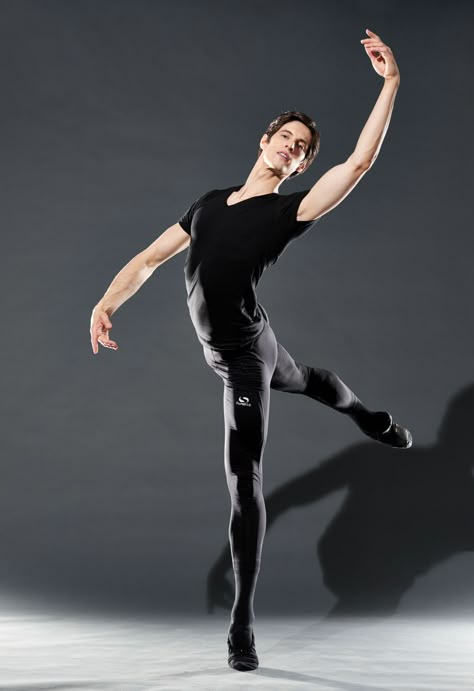

Butterfly Man: 10 facts about Vaslav Nijinsky

Publications of the Theater section

Audio version: Butterfly Man: 10 facts about Vaslav Nijinsky

Vaslav Nijinsky became famous after his first role. A few years later, he already shone on European stages: he brought the audience to crazy applause with his dance parts and to cries of indignation with the avant-garde choreography of his productions. Read why Nijinsky was fired from the Mariinsky Theatre, how he created his innovative performances, and in what unusual way the artist proposed to his bride.

Read why Nijinsky was fired from the Mariinsky Theatre, how he created his innovative performances, and in what unusual way the artist proposed to his bride.

"Jumping imp"

Vaslav Nijinsky. St. Petersburg, 1907-1911. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theater and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaclav Nijinsky as the White Slave and Anna Pavlova as Armida in Mikhail Fokine's ballet The Pavilion of Armida. Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, not earlier than 1907. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theater and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky as a Slave in Nikolai Sergeev and Marius Petipa's ballet "Tsar Candaulus". Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, 1908-1909. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky danced from a very young age: his father and mother were artists, kept their own ballet troupe and toured cities with it. When the father left the family, the mother gave the younger children - Vaslav and Bronislav Nizhinsky - to the Imperial Ballet School.

Nijinsky showed no interest in almost any discipline other than dance. He was strong and enduring, he easily repeated the most complex movements after the teachers. The hallmark of the light, plastic young man was high jumps: he jumped the farthest in his ballet class and hovered at the top, as if levitating above the floor.

Vaslav Nijinsky made his debut at the Mariinsky Theater at the age of 15 in the ballet Acis and Galatea. This was the first performance choreographer Mikhail Fokin staged at the Mariinsky Theater. And the ballet was already innovative: the choreographer placed the artists on several levels - some of them sat and lay on the stage - and abandoned the symmetrical dance pattern that was traditional in those years. But conservative spectators were shocked not so much by the production as by the debutant Nijinsky: after his performance, the audience shouted "Bravo!" and called the "jumping imp" for an encore.

Russian Ballet Premier

Vaslav Nijinsky as the Greek Slave in Mikhail Fokine's Evnika. Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, 1908-1909. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, 1908-1909. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky as the Young Man in Mikhail Fokine's ballet Chopiniana. Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, 1908-1910. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theater and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky as the White Slave in Mikhail Fokine's ballet The Pavilion of Armida. Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, 1907-1909. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Before Vaslav Nijinsky, Russian ballet was predominantly female: men did not play the main roles, they were secondary characters who, at the right moment, only supported the dancers and created a backdrop for their parts. This tradition was maintained by Marius Petipa, the chief choreographer of the Mariinsky Theater in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was replaced by Mikhail Fokin, who began to update the repertoire and reform the ballet as a whole. In Fokine's productions, bright male roles appeared, and young Nijinsky shone in them. He became the first premiere of Russian ballet since the beginning of the 19th century.

In Fokine's productions, bright male roles appeared, and young Nijinsky shone in them. He became the first premiere of Russian ballet since the beginning of the 19th century.

Romola Nizhinskaya, the artist's future wife, recalled how she first saw him in a ballet:

“Suddenly, a slender, flexible, like a cat, Harlequin flew onto the stage. Although his face was hidden by a painted mask, the expressiveness and beauty of his body made you realize that you were facing an outstanding dancer... magical power over the audience... Forgetting everything, the audience rose from their seats in unison; they shouted, sobbed, showered the stage with flowers, gloves, fans, programs, possessed by indescribable delight”

Expulsion from the Mariinsky Theatre.

Vaslav Nijinsky as Albert and Tamara Karsavina as Giselle in Mikhail Fokine's ballet Giselle. Paris, France, 1910. Photo: Bert August / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky as Harlequin and Lydia Lopukhova as Columbine in Mikhail Fokine's ballet Carnival. Paris, France, not earlier than 1910. Photo: Streletsky de Jean / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky as Albert in Mikhail Fokine's Giselle. Paris, France, 1910. Photo: Bert August / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

But the artist soon had to leave the first theater stage of the empire. There were rumors that Vaslav Nijinsky was the victim of behind-the-scenes intrigues: for example, Sergei Diaghilev, who had weight in society and connections, dreamed of luring him into his European enterprise. Be that as it may, in one of the productions of Giselle, the young dancer appeared on stage in a very revealing costume - a tight-fitting leotard, without the traditional bandage on the hips. This image was created for him by Alexander Benois, who wanted to bring the spirit of the Middle Ages into the dance. They tried to stop the ballet, but Nijinsky refused to change clothes and played his part. The Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna attended the performance. Soon Mikhail Fokin was given an order to fire Vaslav Nijinsky.

They tried to stop the ballet, but Nijinsky refused to change clothes and played his part. The Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna attended the performance. Soon Mikhail Fokin was given an order to fire Vaslav Nijinsky.

See also:

- Russian ballet abroad

- 10 theater artists of the Silver Age

- “Well, what a pharaoh you are! You are not a pharaoh, you are a lackey”

The failed ballets of the choreographer of the Russian Seasons

Vaslav Nijinsky as Faun in his ballet The Afternoon of a Faun. Paris, France, 1915. Photo: Streletsky de Jean / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky (left) and Entrepreneur Sergei Diaghilev. Nice, France, 1911. Photo courtesy of Alexandra Botkina / russiainphoto.ru

Vaslav Nijinsky as Faun in his ballet The Afternoon of a Faun. Paris, France, 1912. Photo: State Central Theater Museum named after A.A. Bakhrushina, Moscow

Sergei Diaghilev almost immediately invited Nijinsky to the Russian Seasons. Nijinsky first appeared on the Parisian stage in 1911 in the ballet The Phantom of the Rose, which immediately glorified the young dancer.

Nijinsky first appeared on the Parisian stage in 1911 in the ballet The Phantom of the Rose, which immediately glorified the young dancer.

A year later, the artist presented his own performance here - “Afternoon of a Faun”. His choreography was far from traditional: without exquisite complex movements, with angular static poses - Nijinsky was inspired to create them by images from ancient Greek vases. The nymphs were wearing sandals and started their step from the heel, and not from the toe, as in the classical dance.

A real scandal erupted in Paris. The city was divided into two camps. The owner of the Le Figaro newspaper, Gaston Calmette, published an article in it entitled "Mistake": “We saw a faun, unbridled, with disgusting movements of bestial erotica and completely shameless gestures. And that's it. Well-deserved whistles accompanied the overly expressive pantomime of a lustful animal, disgusting in front and even more disgusting in profile. Such animalistic realities are never accepted by a true spectator” . Auguste Rodin, an admirer of the Ballets Russes and Nijinsky in particular, wrote in a reply article: "... in no other role was Nijinsky so incomparable and delightful as in The Afternoon of a Faun." No jumps, no jumps - nothing but the facial expressions and gestures of a half-asleep animal... It has the beauty of antique frescoes and statues; he is the ideal model that every painter and sculptor yearns for.” .

Auguste Rodin, an admirer of the Ballets Russes and Nijinsky in particular, wrote in a reply article: "... in no other role was Nijinsky so incomparable and delightful as in The Afternoon of a Faun." No jumps, no jumps - nothing but the facial expressions and gestures of a half-asleep animal... It has the beauty of antique frescoes and statues; he is the ideal model that every painter and sculptor yearns for.” .

The ballet "The Rite of Spring" was even more unexpected for the public. Its plot told about the pagan ritual of spring sacrifice, in which the girl, who was "gifted" to the earth, danced frantically to death. Avant-garde music for the ballet - with dissonances and sharp transitions between keys - was written by Igor Stravinsky. The scenery and flashy make-up were designed by Nicholas Roerich. And Nijinsky built the choreography: the ballerinas danced with their socks turned inside and their shoulders upturned.

“People whistled, insulted the actors and the composer, shouted, laughed… The arguments of the audience were not limited to a verbal skirmish and eventually turned into hand-to-hand combat.

A richly dressed lady sitting in a box of benoir got up and slapped a young man who was whistling nearby ... Princess P. left the box with the words: "I am sixty years old, but for the first time they dared to make a fool out of me." At that moment, an enraged Diaghilev shouted from his box: "I beg you, gentlemen, let me finish the performance" ... I rushed backstage - it was no better there than in the auditorium. The dancers were almost crying, they were shaking nervously... The only calm moment came when it was time for the Chosen One to dance. Filled with such indescribable strength and beauty, he disarmed even the indomitable audience. This part, which requires incredible efforts from the ballerina, was excellently danced by Maria Pilz.0003

Nijinsky was still praised as a dancer, but his avant-garde ballets were only accepted by audiences over time. "Afternoon of a Faun" and "The Rite of Spring" entered the regular repertoire of the Seasons a few years later. And the street in the Swiss city of Montreux, where Igor Stravinsky worked, was even named after the ballet - Sacred Spring Street.

The Bird Man

Vaslav Nijinsky as the Golden Slave in Mikhail Fokine's Scheherazade. Berlin, Germany, late 1910 years. Photo: Bert August / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theater and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

From left to right: Alexander Orlov as Arap, Tamara Karsavina as Ballerina and Vatslav Nijinsky as Petrushka in Mikhail Fokine's Petrushka. Paris, France, 1911. Photo: Bert August / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky in Siamese Dance in Mikhail Fokine and Vaslav Nijinsky's ballet Orientalia. 1910–1914. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

During the life of Nijinsky, who was called the bird-man, butterfly-man, many suspected that the secret of his gift lay in the special structure of his legs. Even in childhood, they were unusually strong. And this despite the fact that Nijinsky never seriously went in for sports: ballet dancers were allowed only a few types of activities. At the Imperial School, boys could fence and play Russian bast shoes, and later, when theatrical performances began, they could only swim.

At the Imperial School, boys could fence and play Russian bast shoes, and later, when theatrical performances began, they could only swim.

Later, when the famous dancer got a personal massage therapist, he complained that he was terribly tired massaging his “muscles of steel”.

“Vaclav's legs are very strong, muscular, and they were really impressive. He could use his feet as well as his hands, he could even grab onto a block or rope with his toes, like a bird on a perch. The ankles were so thin that it seemed that when the leg itself was still, the muscles still twitched. His legs resembled those of a fine thoroughbred racehorse."0003

Romola Nijinska later recalled that one day a surgeon who was examining her husband after an injury in the theater was amazed by an x-ray of his legs. Allegedly, in structure, they resembled the limbs of a bird. However, the doctors who examined the artist's body after death did not find anything unusual in his legs.

Acquaintance with Auguste Rodin

Nijinsky's jump. Orientalia Ballet, 1910

Rodin was one of Nijinsky's most devoted admirers, both as a dancer and as a choreographer. After the play "Faun's Afternoon Rest", the sculptor approached the artist with the words: “My dreams came true. And you did it. Thank you" .

Thanks to a sculptor who brought a friend with a movie camera to the theater, a single video recording of Vaslav Nijinsky's dance appeared. Diaghilev was always categorically against filming. He believed that ballet was too complex an art form to be watched from the screen, especially since the quality of the recording in those years was very low.

Later, Auguste Rodin wanted to make a sculpture of a famous dancer. Nijinsky came to his studio, the sculptor made sketches and sketched his muscles in different positions. He settled on the pose of Michelangelo's David.

“Nijinsky patiently posed for hours, and when he got tired, Rodin sat him down and showed him his sketches.

Since they couldn't talk because of the language barrier, the sculptor painted what he wanted to explain. Vaclav answered with the help of movements. Maybe the code was too complicated for those around them, but both of them understood each other perfectly. The sessions had to be cancelled.

Pantomime - marriage proposal

Vaslav Nijinsky at a rehearsal at Le Palais du Soleil. Monte Carlo, Monaco, 1911. Photo courtesy of Alexandra Botkina / russiainphoto.ru

Vaslav Nijinsky (sixth from left) with the ballet troupe of Sergei Diaghilev on the deck of the steamship ARON on their way to South America. 1913 Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky with his wife Romola Pulskaya. 1916 years old Photo: Library of Congress, Washington, USA / wikimedia.org

Vaslav Nijinsky married in 1913 - a ballerina, a Hungarian aristocrat Romola de Pulska. She fell in love with the artist almost immediately when she saw him on stage - she got a job with Diaghilev, went with the Russian Ballet on all tours and even went to Buenos Aires, where many dancers refused to go: it was necessary to swim across the ocean for 21 days.

Romola later recalled how she tried to draw Nijinsky's attention to herself: she deliberately bumped into him on deck, sat for hours at rehearsals, asked to be introduced to her. The dancer could not remember her for a long time, did not distinguish her from the crowd, and did not even always say hello. But Romola Pulska did not give up, and on the 16th day of the voyage, Vaclav Nijinsky proposed to her. First, through the organizer of the tour, Dmitry Gintsburg, and a little later, personally.

“…It was half past ten when I went on deck. Suddenly, as if from nowhere, Nijinsky appeared. "Mademoiselle," he said in French, "won't you and I?" - and mimed, pointing to the ring finger of the left hand, where it was supposed to wear a wedding ring. I nodded in the affirmative, waved my hands and quickly said: “Yes, yes, yes.”

They got married in Buenos Aires: the first ceremony was held by the mayor of the city in the town hall, and the second, evening, traditionally took place in the church.

Follower of Leo Tolstoy

Vaslav Nijinsky in "Siamese Dance" in the ballet "Orientalia" by Mikhail Fokine and Vaslav Nijinsky. Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, 1907-1910. Photo: State Central Theater Museum named after A.A. Bakhrushina, Moscow

Vaslav Nijinsky (standing on the right) with the troupe of Sergei Diaghilev in the buffet of the German Club. St. Petersburg, 1910. Photo: Ivan Alexandrov / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theater and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky. St. Petersburg, 1907-1909. Photo: St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Romola Nijinska wrote that at one time her husband was fascinated by the ideas of Tolstoyism, the religious and ethical doctrine created by Leo Tolstoy. His followers professed love for their neighbor, constant work on their morality and simplification - the desire for minimalism in all areas of life. Nijinska recalled that her husband reproached her when she was upset because of lost luggage or dresses that had been gnawed by mice:

“I give you furs, jewelry and whatever you want,” Vaclav said softly, “but isn't it stupid to attach such importance to it? Haven't you ever thought about how cruelly to kill these animals? And how dangerous is the occupation of pearl divers: after all, they also have children, and yet they endanger themselves daily for the sake of adornment of women.

Already ill, he wrote in his diary about his wife: “She doesn't get better because she likes to eat meat. I have said many times that eating meat is bad. They don't understand me. They think that meat is a necessary thing. They want a lot of meat" .

"The horse is tired." Mental illness of the artist

Vaslav Nijinsky in the last years of his life. Austria, 1945–1950 Photo: Morgoli de Nick / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaclav Nijinsky as the Phantom of the Rose in Mikhail Fokine's ballet The Vision of the Rose. Late 1911 years old Photo: Bert August / St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatrical and Musical Art, St. Petersburg

Vaslav Nijinsky's last jump. 1939 Photo: Jean Monzon

After World War I, the Nijinskys settled in Switzerland. Here the first serious signs of a severe mental illness appeared: the dancer either fell into a melancholy mood, or became quick-tempered and irritable, and once pushed his wife and daughter down the stairs.

Romola Nijinska, who was accustomed to her husband's gentle and delicate treatment, for a long time could not understand what was happening to him. The diagnosis was made by a doctor in a Swiss clinic when Nijinsky almost did not recognize his relatives.

The last time the dancer and choreographer performed on stage was in 1919. About his performance, he said to his wife: “This will be my wedding with God” . Nijinsky danced strange, frightening parts, made a cross out of velvet on the stage, and at the end said: "The horse is tired" .

“The audience came to have fun. She thought I was dancing for fun. I danced terrible things. They were afraid of me, and therefore they thought that I wanted to kill them. I did not want to kill anyone”

Relatives did not give up hope of curing Nijinsky. The wife followed the medical prescriptions, Diaghilev found out about the illness and came to restore his mind with the help of the theater.

The impresario took the artist to performances, but he was indifferent to performances.

Nijinsky's last jump

In 1939, the dancer had been ill for almost 20 years, Serge Lifar, the famous dancer of the Russian Ballet, chief choreographer of the Paris Grand Opera and admirer of Nijinsky, came to the clinic. Lifar brought an accompanist and a photographer. The artist was going to dance the best parts from his ballets for Vaslav Nijinsky - he believed so strongly that the love of art would help the dancer to wake up from the illness. A separate room was vacated for the performance, in which Serge Lifar performed for several hours. And at one moment Vaslav Nijinsky got up and jumped. The photographer managed to capture this moment and the picture entered the history of the ballet under the name "The Last Jump of Vaslav Nijinsky".

Author: Diana Teslenko

Tags:

Theater historyBalletTheatersPublications of the Theater section

Publications of the Traditions section

Let's remember how they danced in Rus'.

Kamarinskaya and the mistress, a Cossack and a quadrille, a round dance and a fair dance with a bear. Not a single holiday in Rus' was complete without dance. The dances were named after the melody, the number of dancers or the pattern of movements. The dances were lyrical or martial. One for each case. The soul sings - the legs start dancing .

Khorovod . Dance with pagan roots. Circle in honor of Yarila, the ancient god of the sun. "Walking after the sun" is part of the Slavic rites. Over the centuries, the ritual character has faded into the background. The round dance has become the main decoration of Russian folk holidays. The nature of the dance changes from occasion to occasion. Either they start a round dance in honor of the arrival of spring, then they meet Ivan Kupala holding hands, scarves or girlish wreaths.

Three . A folk dance that can be unmistakably recognized by counting the dancers. Initially, it was a man and two women.

Rhythm and steps are like in a Russian trio of galloping horses. The troika is danced not only by folk dance groups, but also on the classical stage. As, for example, in the ballet The Nutcracker to the music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Kalinka . A dance performed to a song that is only reputed to be folk. Authorship belongs to Ivan Larionov. The Russian composer and folklorist wrote Kalinka in 1860. The melody went straight to the people from the stage of the Saratov amateur theater. There are no special choreographic figures in Kalinka: it is an improvisation dance. Including on ice, as in the case of figure skaters Irina Rodnina and Alexander Zaitsev.

Khorovod

Kalinka

Lady . A daring dance like a "social conflict" in the spirit of who will dance whom. The main characters are the "Madame-Lady" and the "Peasant Muzhik". To the accompaniment of an accordion or balalaika, majesty opposes prowess, smoothness of movement versus dexterity.

According to one of the versions, the Oryol province became the birthplace of the dance.

Kamarinskaya . The dance "hands on hips, from heel to toe" became a fantasy for the orchestra. Mikhail Glinka in his overture used the melody itself and the overtones characteristic of folk singing, and Pyotr Tchaikovsky included the theme in the "Children's Album". In the main role of the dance version is the "Kamarin peasant", a cheerful and provocative resident of Kamarichi, the volost of the Oryol province.

Cossack . Russian, Terek, Kuban. The dance is international with squats, pair dances and jumps. The peppy and fervent melody of a Cossack girl has been known since the 18th century. The glory of folk dance reached the Parisian salons along with the Russian troops. Alexander Dargomyzhsky wrote "Little Russian Cossack" for the symphony orchestra, and since the 19th century, the Cossack in Russia was "promoted" to a ballroom dance.

Kazachok

Russian folk dance

Russian folk dance

See also:

- Vesnyanka and round dances. Rites and traditions: from Easter to Krasnaya Gorka

- Test for knowledge of Slavic traditions

- "Birch". The secret of the floating step

Squatting . Dance as an element of combat. Initially, Slavic warriors squatted on the attack, and in the time of Suvorov they competed in the "combat squat" along with drill and shooting. Either an acrobatics exercise, or a dance that raises morale. In the Vologda Oblast, a century ago, they competed in dances, throwing knees, and the naval squatting dance was called "Apple" - after the name of the tune.

Quadrille . From a French village to a Russian one through noble assemblies. Russified French dance in Russia has acquired its own traditions. The dance meeting of several couples has grown into a real romance in a dance with many chapters: "acquaintance", "walk", "separation", "farewell".