How did dance cards work

| American Antiquarian Society

| In the Spring of 2012, AAS published The American Antiquarian Society, 1812-2012: A Bicentennial History by Philip F. Gura. To supplement this publication, the Society digitized and made available in high-resolution the images and descriptions from the text. | |

| Architectural resources in the collection include design books, drawings, lithographs, engravings, periodicals, and photographs. | |

| In 1995, AAS welcomed its first class of Creative and Performing Artists and Writers Fellows. Visual artists, fiction writers, non-fiction writers, poets, playwrights, performance artists, musicians and composers, as well as film and media makers came to the society seeking to create original works based on American history to present to non-academic audiences and readers. | |

| This online resource both catalogs and contextualizes the twenty-two pieces of the Ridgway dinner service “Beauties of America” – a subset of the Society' collection of Staffordshire potter using maps, photographs, source prints and rich descriptions of the objects. | |

| Most of the prints in this exhibit were designed simply to please the eye, but they are also useful to historians who would like to understand how 19th century Americans thought about the world in which they lived. | |

| Drawing on the American Antiquarian Society’s unparalleled collection of prints and books, the exhibition, Beyond Midnight: Paul Revere, will transform viewers’ understanding of the iconic colonial patriot. This in-depth examination of Revere’s many skills as a craftsman will help illustrate the entrepreneurial spirit of an early American artisan who stood at the intersection of social, economic, and political life during the formation of the new nation. | |

| This online exhibition features lithographs, chromolithographs, trade catalogues, trade cards, and product labels from the American Antiquarian Society's collection that help shed light on major changes in the way Americans in the North produced and sold their food in the second half of the nineteenth century. | |

| The Caribbeana Project at the American Antiquarian Society features some of the major works about the Caribbean or published in the Caribbean that can be found in AAS's collections. These include letters, manuscripts, almanacs, laws, newspapers and bound volumes of all kinds. While not a comprehensive accounting of AAS's Caribbeana holdings, this exhibition examines and emphasizes the close relationship between early British North America or the United States and the Caribbean World in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This website samples over one hundred of AAS’s most interesting Caribbean items, delving into the close relationship between these two regions, and opening up the collection for scholarship by identifying avenues for potential research. | |

| In 2015, the William C. | |

| This exhibition highlights the Society's outstanding collection of lithographs, watercolors, and drawings of artist David Claypoole Johnston. | |

| Some of the earliest and rarest materials printed in British North America were not printed in English. Instead, these books, pamphlets, and broadsides were printed in the various dialects of Algonquian, the language of the Native Americans who populated the American Northeast. | |

| In the early days of the American Antiquarian Society, founder Isaiah Thomas asked members to send materials for preservation in the Society's library at Worcester, Massachusetts. Over the course of two hundred years, generations of the Society's members, friends, and staff have ably answered Thomas's call. This exhibition celebrates the generosity and farsightedness of some of the many collectors, book dealers, and librarians who have, each in his or her own way, contributed to the greatness of AAS. | |

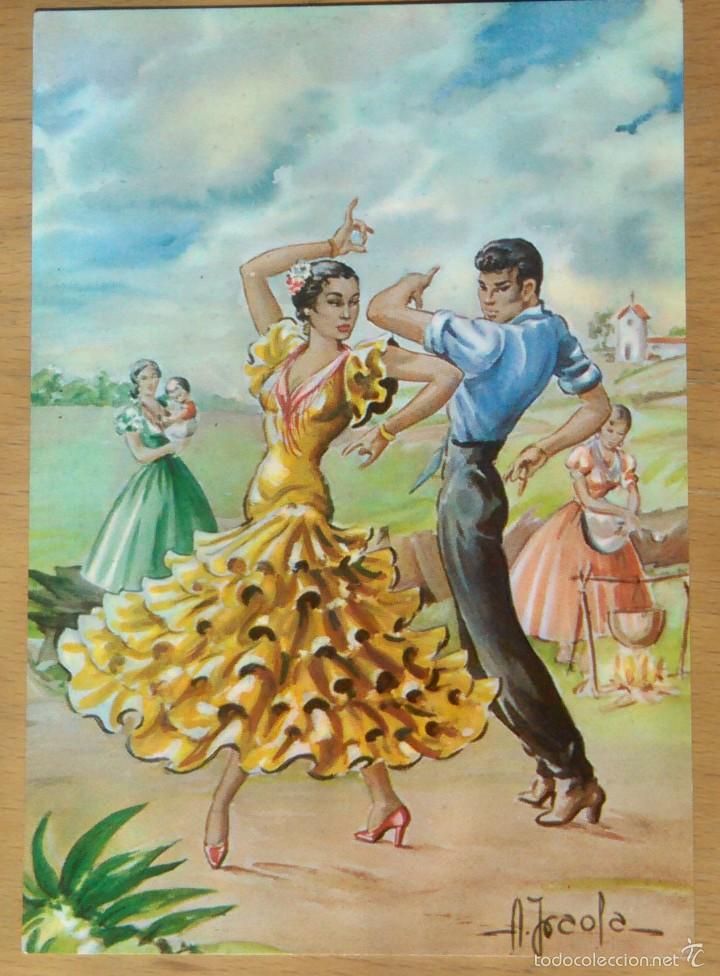

| An Invitation to Dance: A History of Social Dance in America showcases the unique print culture items on the subject of dance within the Society's holdings. | |

| With over 800 images and 300 mini-essays, this site offers a unique and comprehensive view of the broadsides that Isaiah Thomas (1749-1831) collected in early nineteenth-century Boston. Each broadside includes a brief explanation of its content by Kate Van Winkle Keller. | |

| The American Antiquarian Society is a natural home for an online exhibition about James Fenimore Cooper's works. For many years the Society has supported The Writings of James Fenimore Cooper, an editorial project the bears the seal of the MLA Committee on Scholarly Editions. To support the work of the editors of the Writings, also knows as the Cooper Edition, the Society has actively collected editions of Cooper's works printed in any language up to the year 1877. | |

| This online exhibition showcases the collection and career of Boston lithograph firm Louis Prang & Company, within the collections of the American Antiquarian Society. Featuring prints, salesman's samples and progressive proof books, this exhibition tells the story of Prang during the height of his career in chromolithography during the second half of the nineteenth century. Prang pioneered developments in the chromolithographic process, creating painting-like prints for the general public. He is also considered the "Father of the American Christmas card" having introduced it to the American public in 1874 after the wife of an agent suggested the idea to him while he was promoting his business abroad. Instrumental in the promotion of art education for public school students, Prang helped develop curriculum for schools, teaching art instructors, and creating safe, quality art supplies for students. | |

| Making Valentines: A Tradition in America is designed to show the evolution of the Valentine's Day card. This exhibition is drawn, in part, from an original display created by AAS staff member Audrey Zook in 1985. It includes a select group of Valentine's Day cards belonging to the Society. | |

| This online exhibition explores images of men in the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. The selection of prints from the Society's collections represents male roles and activities and reflects social expectations. | |

| At the start of America’s industrial revolution, a large number of young women found employment and a unique form of independence in American textile mills. Featuring selections both by and about the mill girls, from approximately 1834 to 1870, the exhibition highlights the culture and working conditions of the mills and the actions the women took to better their lives through self-advocacy. | |

| The history of America has always been intimately entwined with the history of communications media—and that has always been changing. This exhibition broadly explores the interconnectedness of American news media, in all its formats, with changes in technology, business, politics, society, and community from 1730 to 1865. | |

| This exhibitions uses images and objects from the AAS collections to illuminate the spaces where reading happened in early America. | |

| This exhibition features the images of thirty-one Worcester residents depicted in the Society's portrait paintings, miniatures, and sculpture collections. | |

| As one of the first publishers to focus exclusively on products for children, McLoughlin Brothers was able to shape and define the American picture book market. | |

| This online exhibition effectively creates a digital archive of several Algonquian-language printed books and pamphlets, or wussukwhonk as they are called in the Nipmuc language, chosen for the value they add to current language reclamation work taking place in Nipmuc country. The manuscript collections featured here include town records, land deeds, and account books from English settlements established on Nipmuc homelands in the southern part of the area now referred to as Worcester County. | |

| Using print and manuscript collections at the American Antiquarian Society and the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, this exhibition explores portrayals of Turner in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. | |

| This online exhibit, generated using images from the Prints in the Parlor cataloging and digitization project, considers the ways William Shakespeare's (1564-1616) characters were pictured inside the covers of literary annuals and gift books in the nineteenth-century. | |

| This exhibition brings together a selection of images from the Society's collections that illustrate the most popular and most beautiful New England destinations for summertime visitors. | |

| As this exhibition shows, the practice of exchanging valentines on February 14th was a distinctly modern tradition, first popularized in the United States in the 1840s. Following practices previously developed in England, lovers, friends, and family members bought or made fanciful valentines decorated elaborately with paper lace, colorful printed materials, ribbons, hair, and scraps. Manufacturers of valentines, such as Esther Howland and George C. Whitney, played a crucial role in establishing Valentine’s Day as an American holiday. These same manufacturers often sold valentine writers, collections of short poems and affectionate messages meant to be copied verbatim, to aid the less poetically-inclined in wooing their beloved. Along with valentines themselves, these writers shaped the way Americans both expressed and experienced affection for one another. | |

| Visions of Christmas exhibits an array of Christmas images from the Society's collections. Among the featured artists are F.O.C. Darley, Thomas Nast, Louis Prang, and the McLoughlin Brothers. | |

| This exhibition explores the connections between American and French lithography in the early days of this printing technology. Themes include the circulation and reproduction of French imagery in the United States, the stylistic contributions of French lithographic artists who immigrated to America, and the reproduction of American genre paintings by French publishers for distribution in Europe and the United States. | |

| A look at women's work, from before the American Revolution through the Industrial Revolution, using selected images from the Society's collection. | |

| This exhibition explores the AAS collection of dime novels. Full of romance and adventure, dime novels were a variety of melodramatic fiction that was popular in the United States from about 1860 until the early 1900s. |

Dance Card Days | Millikin University

Dance Card from Millikin's SENIOR BALL May 20, 1927

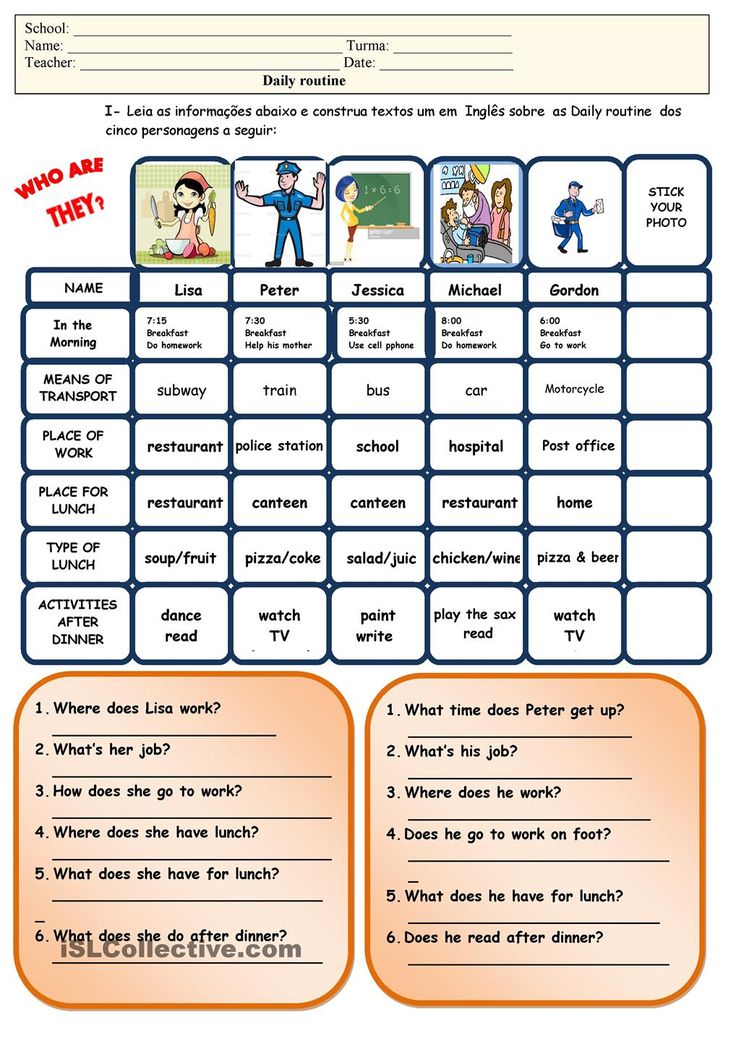

From Millikin's earliest days, dances became an important part of student life. During the first three decades at J.M.U., getting “carded” at a dance carried an entirely different meaning from what would likely enter the mind of today's students. Popular on college campuses in the early 20th century, the Dance Card was a decorative and functional keepsake that every woman who attended a dance was able to use during the dance and take home as a souvenir. This exhibit features the Dance Cards from Millikin's past.

Dance Card for unknown dance. Interior of card.

What is a dance card?

A dance card or ballspende, is a card, often decorative, that is used by an attending woman to record with whom she will dance at formal dances and balls. Though originating in the 18th century, they became quite popular in the ballrooms of Vienna and elsewhere in Europe in the 19th century and remained popular at college dances in the U.S. into the 1920s, lingering on into the 1930s in some cases (including here at Millikin University).

Though originating in the 18th century, they became quite popular in the ballrooms of Vienna and elsewhere in Europe in the 19th century and remained popular at college dances in the U.S. into the 1920s, lingering on into the 1930s in some cases (including here at Millikin University).

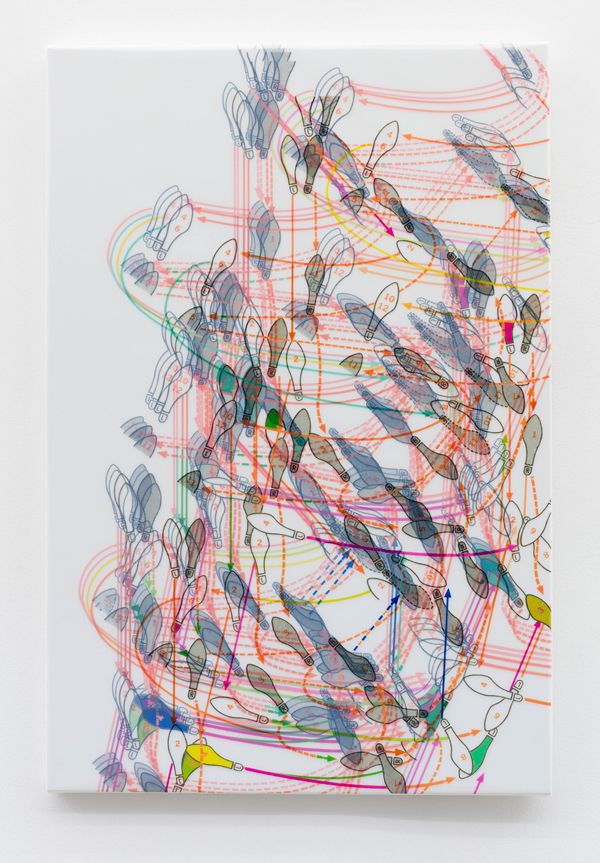

The cards were designed to be worn on the wrist (hence the long strings often attached to them) or attached to the gown and would allow the woman to “pencil in” the names of gentlemen seeking a dance.

Though the cards themselves have long since disappeared from college dances, the term is still sometimes used metaphorically, as in “is their room on your dance card?” meaning “do you have some time for me?” Or in sports to refer to teams on the upcoming schedule as in “who is on the team's dance card this season?” Even the term “pencil me in” is still in use today. (Note the tiny pencil attached to the card pictured above and the names "penciled" in on the inside of the card)

What is in the cards?

While some hold that Tarot cards can reveal the future, the “dance card” can be even more revealing—about the past! Perhaps a bit more challenging than your typical primary source, the tiny dance card is loaded with historical information. It certainly provides a glimpse into the culture and society of its time, but can also reveal specifics of time, date, location, attendees, traditions (such as the same song appearing as the same dance # year after year for a specific fraternity's dances), popular menu choices of the time, and so on.

It certainly provides a glimpse into the culture and society of its time, but can also reveal specifics of time, date, location, attendees, traditions (such as the same song appearing as the same dance # year after year for a specific fraternity's dances), popular menu choices of the time, and so on.

Delta Sigma Phi March 1926 dance

You will notice that the title page provides you with the date, time, and location of the dance and that it was for the Alpha Lambda chapter of Delta Sigma Phi fraternity (the Millikin chapter opened in 1920 and remains active on campus today).

The next page on this dance card provides the menu for the dinner portion of the formal dance and reveals some of the "typical" formal dining fare of the 1920s.

The next two pages feature the numbered lines for each of the dances. Notice that two of the scheduled songs for those dances are pre-listed. The 6th song of that evening was to be "Dear Old Girl of Delta Sigma Phi" and the 7th was to be the "Carnival Dance. ”

”

Some dance cards would list songs for each numbered selection, others would list the names of male fraternity members rather than song numbers, so the woman would pencil in the song rather than the male partner's name.

A quick glance at other Delta Sigma Phi cards reveals that the 6th & 7th songs being the choices listed here was a tradition for the fraternity, as they are found on dance cards from throughout the 1920s.

The final page lists the chaperones, (which included then University President Mark Penney and his wife) the band that provided the music and the members of the dance committee.

Above: This Tau Kappa Epsilon dance card from a TKE dance in April of 1932 provides an example where the names of members of TKE were listed as opposed to the songs.

Oldest card in the collection

The oldest card in the Archives' collection is one from a May 1907 dance of men's social fraternity known as I.T.G.O.S.T. (Millikin University's very first, and least known about, fraternity)

Above: The symbol on the front cover of the card incorporates all the letters of I. T.G.O.S.T. It is not known at present what those letters stood for, although one possibility is In The Good Old Summer Time (a popular song from the time period of the fraternity's founding in 1903).

T.G.O.S.T. It is not known at present what those letters stood for, although one possibility is In The Good Old Summer Time (a popular song from the time period of the fraternity's founding in 1903).

As the front cover indicates, the card belonged to a "Babe" but it is not known what her actual name was.

The dances and songs are listed and the names of members of I.T.G.O.S.T. with which she shared those dances are signed in as well.

The final page lists the members of the I.T.G.O.S.T. and their patron, Prof. William Clarence Stevenson.

Other Dance Cards in the Collection

Delta Sigma Phi (Apr 1927) Delta Sigma Phi (Apr 1928)

Delta Sigma Phi (May 1929) Tau Kappa Epsilon (Apr 1932)

Tau Kappa Epsilon (Sept 1928) Unknown dance (Dec 1922)

Unknown Dance (Unknown Date) Delta Delta Delta (Apr 1926)

Sigma Alpha Iota (Autumn Dance, unknown date) Millikin University Senior Ball (May 1928)

Theta Gamma (May 1925) Sigma Alpha Epsilon (May 1925)

Junior Prom (Apri 1929) Sigma Alpha Epsilon (May 1927)

Sigma Alpha Iota (unknown date) - unique leather pouch with removable cards

Sigma Alpha Iota (unknown date) Sigma Alpha Iota (Unknown date)

Aston Hall Prom (Feb 1924) Pi Mu Theta (May 1921)

unknown dance (unknown date) unknown dance (unknown date)

Balls and traditions.

Interesting facts

Interesting facts Ball, ball, ball!!!

Ball is always a holiday. Bright, colorful, sparkling, cheerful. And this holiday has always been desired and loved in Russia.

Balls were given all year round, but the season began in late autumn and continued throughout the winter. Often in one evening I had to attend two or three balls, which required considerable strength, besides, many balls ended in the morning, and the next day it was necessary to make visits and prepare for the upcoming amusements.

Balls and masquerade balls were divided into class, professional, age categories, timed to coincide with special celebrations, and were court, public, private, merchant, wedding, children's ...

Balls of the Noble Assembly, balls of artists and balls held by foreign embassies, merchant balls.

History of balls in Russia

The first ball in Russia took place in Moscow at the wedding of False Dmitry and Marina Mnishek.

Peter I resumed the balls, and since then they have become loved and revered both in the capitals and in the provinces of the Russian Empire.

Peter's assemblies became the prototype of future balls. The assemblies were gatherings with dances. Assemblies began to be held in St. Petersburg and Moscow as early as 1717 in the homes of the Russian nobility.

Assemblies served not only as a means of entertainment - "for fun", but also a place "for reasoning and friendly conversations."

Then, during the reign of Anna Ioannovna, Elizabeth Petrovna and Catherine II, assemblies completely supplanted balls and masquerade balls.

A ball is a solemn public or secular event, the main component of which is a dance program.

Therefore, since the 18th century, dance has become a compulsory subject in all higher and secondary educational institutions, schools and boarding schools. It was studied at the royal lyceum and at modest vocational and commercial schools, at the gymnasium and at the cadet school.

In Russia, they not only perfectly knew all the latest and old ballroom dances, but also knew how to perfectly perform them. The dance culture of Russia in the 19th century stood at a high level.

Ballroom dress code

The ball has its own ceremonial and rules of conduct, which makes it so majestic and luxurious. All this allowed to maintain sophistication and attractiveness.

It was customary to come to the ball dressed smartly. Cavaliers - in a tailcoat pair, tuxedo or suit (depending on specific requirements and conditions), white shirt and vest. By the way, tailcoats were of different colors, only by the end of the 30s of the XIX century the fashion for black was established.

White gloves were an obligatory item of clothing for gentlemen. The civilians wore kid gloves, and the military wore suede gloves.

Moreover, according to the rules, the lady had every right to refuse the gentleman without gloves. Therefore, it was better to come to the ball in black gloves than no gloves at all.

Civilian gentlemen's costumes depended little on fashion and were recommended to be sewn in classical forms.

The military came in full dress uniforms corresponding to their regiments.

Cavaliers came to the ball in boots. Ballroom boots were also worn by the military, and only uhlans were allowed to wear boots. The presence of spurs was not approved. The fact is that the spurs tore the dresses during the dance. But some lancers broke this rule for the sake of panache.

Ladies and girls dressed in fashionable dresses. As a rule, the dress was sewn for one ball and only in extreme cases was used twice.

Ladies could choose any color for the dress, unless otherwise specified. For example, on January 24, 1888, an emerald ball was held in St. Petersburg, at which all those present were dressed in the appropriate color.

Dresses for girls were made in white or pastel colors - blue, pink and ivory, that is, the color of "ivory".

Matching gloves or white gloves were matched with the dress. By the way, wearing rings over gloves was considered bad manners. Even more interesting facts can be found in the historical park "Russia-My History".

Ladies could adorn themselves with a headdress.

The girls were encouraged to have a modest hairstyle. But in any case, the neck had to be open.

The cut of ball gowns depended on fashion, but one thing remained unchanged in it - open neck and shoulders.

With such a cut of the dress, neither a lady nor a girl could appear in the world without jewelry around the neck - a chain with a pendant or a necklace. That is, something had to be worn necessarily.

Ladies' jewelry could be any - the main thing is that they are chosen with taste. Girls were supposed to appear at balls with a minimum amount of jewelry, for example, with a pendant around their neck or a modest bracelet.

An important component of the ladies' ball costume was the fan, which served not so much to create a fresh breath, but as a language of communication, now almost lost.

Recovering to the ball, the lady took with her a ball book - carne or agenda - where, opposite the list of dances, she entered the names of gentlemen who wanted to dance this or that dance with her. Sometimes the reverse side of the fan could be used instead of the agend. It was considered excessive coquetry to brag about your completed agenda, especially to those ladies who were rarely invited.

Rules of conduct at the ball

By accepting the invitation to come to the ball, everyone thus assumed the obligation to dance. Refusing to participate in dances, as well as showing dissatisfaction or making it clear to a partner that you dance with him only out of necessity, was considered a sign of bad taste. And vice versa, it was considered a sign of good education at the ball to dance with pleasure and without coercion, regardless of the partner and his talents.

At a ball, more than at any other social event, a cheerful and amiable expression is appropriate. To show at the ball that you are not in a good mood or are dissatisfied with something is inappropriate and impolite in relation to those having fun.

To show at the ball that you are not in a good mood or are dissatisfied with something is inappropriate and impolite in relation to those having fun.

Starting conversations with acquaintances before paying tribute to the owners was considered indecent. At the same time, not greeting acquaintances (even with a nod of the head) was also unacceptable.

There was a special culture of invitation to dance at the balls. An invitation to a dance was allowed in advance, both before the ball itself and at the ball. At the same time, it was considered impolite if a lady arrived at the ball promising more than the first three dances in advance.

In the ballroom, order and dancing are supervised by the ball steward.

During the ball, gentlemen should monitor the comfort and convenience of the ladies: bring drinks, offer help. The gentleman had to make sure that his lady was not bored.

Talking at a ball is certainly permissible. At the same time, it is not recommended to touch on complex and serious topics, as well as to gather a large company around you.

Buffoonery is not appropriate at balls. Even gentlemen who have a too cheerful disposition are advised to behave with dignity at the ball. Quarrels and quarrels between gentlemen are highly discouraged during the ball, but if disagreements arise, then it is recommended to resolve them outside the dance hall. Ladies are the main decoration of any ball. Therefore, it behooves them to behave affably and nicely. Loud laughter, slander, bad humor can cause disapproval of a decent society. The behavior of the ladies at the ball should be distinguished by modesty, the expression of extreme sympathy for any gentleman can give rise to condemnation.

Most of all, any manifestations of jealousy on the part of ladies and gentlemen are inappropriate at the ball. On the other hand, immodest looks and defiant behavior that provokes other participants in the ball are also unacceptable.

Dancing

According to the rules, the gentleman began the invitation to dance with the hostess of the house, then all her relatives followed, and only then it was the turn to dance with their familiar ladies.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the ball opened with a polonaise, where in the first pair the host walked with the most honored guest, in the second pair - the hostess with the most honored guest.

At the end of the 19th century, the ball began with a waltz, but court, children's and merchant balls opened with a majestic polonaise.

During the 19th century, the number of dances that a gentleman could dance with one lady during a ball changed. So at the beginning of the century this number was equal to one, and already in the 1880s two or three dances were allowed, not following one after another in a row. Only the bride and groom could dance more than three dances. If the gentleman insisted on more than expected number of dances, the lady refused, not wanting to compromise herself.

During the dance, the gentleman entertained the lady with light secular conversation, while the lady answered modestly and laconic.

The cavalier's duties also included preventing collisions with other couples and preventing his lady from falling.

At the end of the dance, the gentleman asked the lady where to take her: to the buffet or to the place where he took her from. After exchanging mutual bows, the gentleman either left, or could remain next to the lady and continue the conversation for some time.

As a rule, after the mazurka, the gentleman led the lady to the table for dinner, where they could talk and even confess their love.

Everyone had dinner in the side parlors, at small tables.

In addition, a buffet was always open at the balls with various dishes, champagne, a large selection of hot and cold drinks.

At the beginning of the century, the ball ended with a cotillion or Greek dance, and from the second half of the 19th century, the ball program ended, as a rule, with a waltz.

The guests could leave whenever they liked, without focusing on their departure - but over the next few days, the invitee paid the hosts a grateful visit.

More information about this time period can be found in the historical park "Russia-My History".

how to attract clients to dance school classes

Alla Makarova has been dancing since the age of four and has been thinking about her school since early childhood. But her dream came true only a little over a year ago, right before the period of self-isolation. We learned from the founder of M&M Dance Studio how the business works and how she copes with difficulties.

How the business started

Alla told Open Academy that she had been dancing since early childhood, but her parents were against such work. Therefore, she studied at the Faculty of Tourism and Service, but at the university she began to teach dances.

At first, Alla worked as a coach, led many groups, and then decided to open her own dance school. She found a studio and rented it in mid-2019. For half a year, a base of coaches and students was formed, but then something happened that happened.

How we coped with the pandemic Alla and the team began to shoot video tutorials, conduct live broadcasts and sell online workouts. It was saved by the fact that no one expected a pandemic, and therefore they were engaged with pleasure.

In order not to alienate clients, Alla set an affordable cost for classes, and the workouts were sold.

When the restrictions were lifted, I had to start all over again: re-assemble the base and build relationships with clients and coaches. And step by step, Alla managed to build a strong business model. Now she plans to scale the business and open new schools in Moscow and the Moscow region.

How to work with coaches

One of the features of the business is that most often students follow the coach, for a specific person and train with him. Therefore, it is important to build trusting relationships with employees and look for an approach to each of them.

Therefore, it is important to build trusting relationships with employees and look for an approach to each of them.

Alla admits that it can be difficult to work with creative people, but she comes up with a system of motivation for each employee. And if a new coach comes, then the leader becomes a curator and helps to get involved in the work process.

How to attract clients

Finding clients is the main part of Alla's job. She builds a sales funnel, attracts students to the first open lesson, where you can meet a new coach. And then converts visitors into buyers.

Targeted advertising on Instagram and work with bloggers are also used for promotion. And Yandex.Maps works well in such a business: a lot of people just find a dance school on the map and come to classes.

Alla told Open Academy that it is much easier to attract adult clients than children. Targeted advertising works much worse to attract schoolchildren, but they come with the help of word of mouth. A bright sign is also important here, so that it would be easier for parents with children to find and pay attention to the dance school.

Targeted advertising works much worse to attract schoolchildren, but they come with the help of word of mouth. A bright sign is also important here, so that it would be easier for parents with children to find and pay attention to the dance school.

Three Tips for New Entrepreneurs

- Find out what interests you and what you are passionate about. Alla's hobby has grown into a business, she easily pays attention to the company both on holidays and on weekends. If she did not like dancing, it would be much more difficult.

- Before starting a business, you need to prepare: study the market, competitors, prices. Understand how you can differ from other companies.

- Do not open a business if there is no client base. Many make repairs, logos, websites, but do not think where to get customers and whether they exist at all. So you can invest large amounts and not earn anything.

Explored are artistic depictions of the standard of beauty, ideal beauty, women as objects, variations on the standard, true womanhood, women at home, American slavery, women in public life, women as performers, use of women as advertising strategies and more.

Explored are artistic depictions of the standard of beauty, ideal beauty, women as objects, variations on the standard, true womanhood, women at home, American slavery, women in public life, women as performers, use of women as advertising strategies and more.

Cook Jacksonian Era Collection arrived at AAS adding almost five hundred books, prints, manuscripts, newspapers, and more to the Society's already significant holdings from or about the Jacksonian Era. This online exhibition follows the books from that collection through the process of being integrated into the Society's other library collections in order to reveal the everyday work of collection-building being done by AAS members, staff, friends, and researchers.

Cook Jacksonian Era Collection arrived at AAS adding almost five hundred books, prints, manuscripts, newspapers, and more to the Society's already significant holdings from or about the Jacksonian Era. This online exhibition follows the books from that collection through the process of being integrated into the Society's other library collections in order to reveal the everyday work of collection-building being done by AAS members, staff, friends, and researchers. This exhibition explores the contributions of those who labored in translating and printing works in the Algonquian family of native languages.

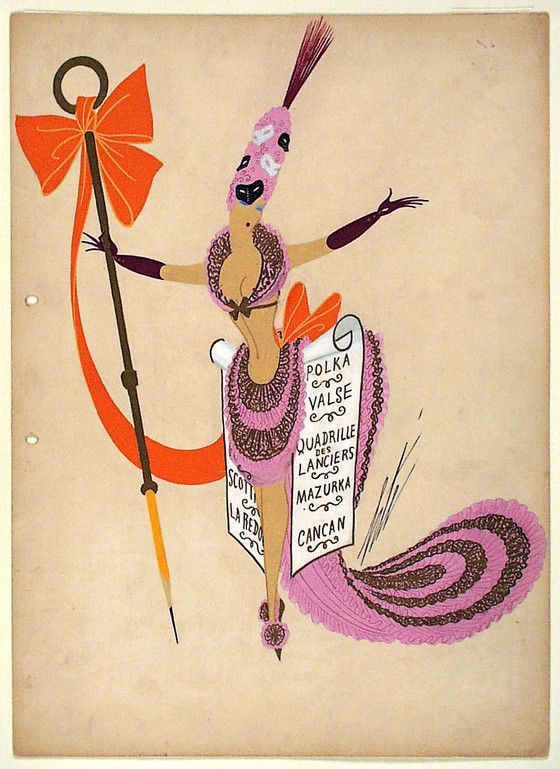

This exhibition explores the contributions of those who labored in translating and printing works in the Algonquian family of native languages.  From its fashion and origins, to its etiquette and opposition, this online exhibit features a sampling of artifacts from the 18th and 19th centuries. Click on the image to the left from Stephen Salisbury's "Bal Masque" ticket to attend.

From its fashion and origins, to its etiquette and opposition, this online exhibit features a sampling of artifacts from the 18th and 19th centuries. Click on the image to the left from Stephen Salisbury's "Bal Masque" ticket to attend.

This exhibition documents the working practice of the firm by associating its products with many of the tools used during the production process, such as printing blocks, designer mock-ups, and watercolor illustration art.

This exhibition documents the working practice of the firm by associating its products with many of the tools used during the production process, such as printing blocks, designer mock-ups, and watercolor illustration art. The bookends of this exhibition are the two “confessions”: one from 1831 and the other from 1967 when William Styron created the most controversial version of Turner to date.

The bookends of this exhibition are the two “confessions”: one from 1831 and the other from 1967 when William Styron created the most controversial version of Turner to date.

Published as cheap paperbacks (most cost only ten cents), they were generally regarded as low-quality fiction.

Published as cheap paperbacks (most cost only ten cents), they were generally regarded as low-quality fiction.