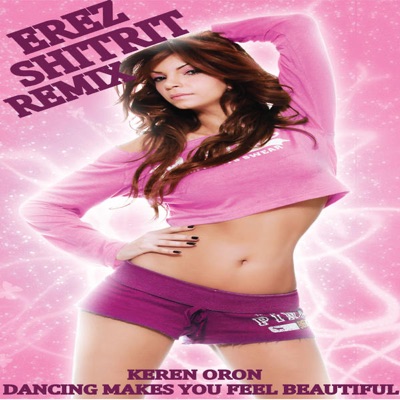

How dancing makes you feel

Science Confirms that Dancing Makes You Happy!

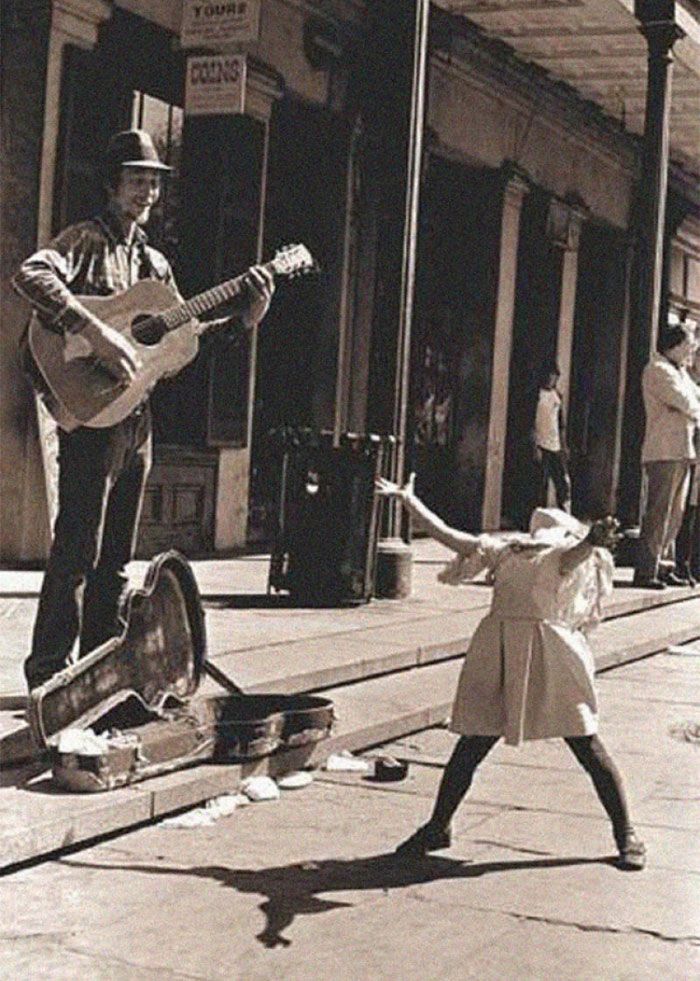

“Without music, life would be a mistake”, said Nietzsche, and he wasn’t entirely wrong because we have a natural instinct that leads us to follow the rhythm of the music. In fact, most children move and clap their hands when they hear a song they like. It is a spontaneous response related to our need to communicate and express our emotions through the movement and the body.

There is no doubt that music is a universal language and everyone, except the people who suffer from amusia, is able to appreciate and enjoy it. In fact, it was discovered that people of different cultures react emotionally in the same way when listening to different types of music. So, it is no coincidence that anthropological studies indicate that groups who were more likely to survive were those who had developed a particular dance and were able to share their feelings dancing.

Of course, music and dance not only serve as social glue, but are also very useful for our physical and mental health. Recent studies revealed that one of the keys to happiness and satisfaction is right on the dance floor.

Steps that heal, movements that make us happy

In 2013, psychologists at the University of Örebro realized an experiment with a group of teenagers who suffered from anxiety, depression and stress, in addition to presenting psychosomatic symptoms such as neck and back pain. Half of these were asked to attend two dance classes a week, while the rest continued with their daily routine.

After two years, those who continued to attend the dance classes (where emphasis was on the pleasure of the movement rather than performance), not only showed a significant improvement in psychosomatic symptoms, but also reported to feel happier.

In another study conducted at the University of Derby, the psychologists worked with people who were suffering from depression. These people received “salsa” lessons for a period of nine weeks. The improvements began to be appreciated after four weeks and, after finishing the course, the participants said they had fewer negative thoughts, better concentration and a greater sense of peace and tranquility.

But the truth is that dance is not only an excellent therapeutic resource. A study at Deakin University revealed that dance has a very positive effect on our daily lives. These Australian researchers interviewed 1,000 people and found that often those who were dancing not only reported feeling happier, but also more satisfied with their lives, especially in relationships, health, and the goals achieved over the years.

Interestingly, also the psychologists at the University of New York discovered a similar effect in children. These researchers worked with 120 children, aged 2 to 5 years old, who were exposed to different types of sound stimuli, some were rhythmic and imitated the rhythm of the music, others were completely arrhythmic. They could appreciate that children who were moving following the rhythmic movements showed more positive emotions and felt happier. Therefore, these researchers concluded that not only we have a tendency to move to the beat of the music, but also that dancing improves our mood.

Why dancing makes us happy?

When we dance our brain releases endorphins, hormones which can trigger neurotransmitters that create a feeling of comfort, relaxation, fun and power. Music and dance do not only activate the sensory and motor circuits of our brain, but also the pleasure centers.

Indeed, neuroscientists at Columbia University say that when we move in tune with the rhythm, the positive effects of music are amplified. Therefore, a little secret to make the most of the music is to synchronize our movements with the beat, so we will be doubling the pleasure.

However, the magic of dancing can not simply be reduced to brain chemistry. Dancing is also a social activity that allows us connect with the others, share experiences and meet new people, which has a very positive effect on our mental health.

What’s more, as we move, our muscles relax to the music, which allows us to free ourselves of the tension built up during the day, especially the one accumulated in the deepest part of the musculature.

Sources:

Duberg, A. et. Al. (2013) Influencing Self-rated Health Among Adolescent Girls With Dance Intervention A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.; 167(1): 27-31.

Zentner, M. & Eerola, T. (2010) Rhythmic engagement with music in infancy. PNAS; 107(13): 5768-5773.

Birks, M. et. Al. (2007) The benefits of salsa classes for people with depression. Nursing Times; 103(10): 32-33.

Lesté, A. & Rust, J. (1984) Effects of dance on anxiety. Percept Mot Skills; 58(3): 767-772.

Credit: Psychology-spot.com

Science confirms: Dancing makes you happy

Home » Science confirms: Dancing makes you happy

“Without music, life would be a mistake”, said Nietzsche, and he wasn’t entirely wrong because we have a natural instinct that leads us to follow the rhythm of the music. In fact, most children move and clap their hands when they hear a song they like. It is a spontaneous response related to our need to communicate and express our emotions through the movement and the body.

There is no doubt that music is a universal language and everyone, except the people who suffer from amusia, is able to appreciate and enjoy it. In fact, it was discovered that people of different cultures react emotionally in the same way when listening to different types of music. So, it is no coincidence that anthropological studies indicate that groups who were more likely to survive were those who had developed a particular dance and were able to share their feelings dancing.

Of course, music and dance not only serve as social glue, but are also very useful for our physical and mental health. Recent studies revealed that one of the keys to happiness and satisfaction is right on the dance floor.

Steps that heal, movements that make us happy

In 2013, psychologists at the University of Örebro realized an experiment with a group of teenagers who suffered from anxiety, depression and stress, in addition to presenting psychosomatic symptoms such as neck and back pain. Half of these were asked to attend two dance classes a week, while the rest continued with their daily routine.

Half of these were asked to attend two dance classes a week, while the rest continued with their daily routine.

After two years, those who continued to attend the dance classes (where emphasis was on the pleasure of the movement rather than performance), not only showed a significant improvement in psychosomatic symptoms, but also reported to feel happier.

In another study conducted at the University of Derby, the psychologists worked with people who were suffering from depression. These people received “salsa” lessons for a period of nine weeks. The improvements began to be appreciated after four weeks and, after finishing the course, the participants said they had fewer negative thoughts, better concentration and a greater sense of peace and tranquility.

But the truth is that dance is not only an excellent therapeutic resource. A study at Deakin University revealed that dance has a very positive effect on our daily lives. These Australian researchers interviewed 1,000 people and found that often those who were dancing not only reported feeling happier, but also more satisfied with their lives, especially in relationships, health, and the goals achieved over the years.

Interestingly, also the psychologists at the University of New York discovered a similar effect in children. These researchers worked with 120 children, aged 2 to 5 years old, who were exposed to different types of sound stimuli, some were rhythmic and imitated the rhythm of the music, others were completely arrhythmic. They could appreciate that children who were moving following the rhythmic movements showed more positive emotions and felt happier. Therefore, these researchers concluded that not only we have a tendency to move to the beat of the music, but also that dancing improves our mood.

Why dancing makes us happy?

When we dance our brain releases endorphins, hormones which can trigger neurotransmitters that create a feeling of comfort, relaxation, fun and power. Music and dance do not only activate the sensory and motor circuits of our brain, but also the pleasure centers.

Indeed, neuroscientists at Columbia University say that when we move in tune with the rhythm, the positive effects of music are amplified. Therefore, a little secret to make the most of the music is to synchronize our movements with the beat, so we will be doubling the pleasure.

Therefore, a little secret to make the most of the music is to synchronize our movements with the beat, so we will be doubling the pleasure.

However, the magic of dancing can not simply be reduced to brain chemistry. Dancing is also a social activity that allows us connect with the others, share experiences and meet new people, which has a very positive effect on our mental health.

What’s more, as we move, our muscles relax to the music, which allows us to free ourselves of the tension built up during the day, especially the one accumulated in the deepest part of the musculature.

Sources:

Duberg, A. et. Al. (2013) Influencing Self-rated Health Among Adolescent Girls With Dance Intervention A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.; 167(1): 27-31.

Zentner, M. & Eerola, T. (2010) Rhythmic engagement with music in infancy. PNAS; 107(13): 5768-5773.

Birks, M. et. Al. (2007) The benefits of salsa classes for people with depression. Nursing Times; 103(10): 32-33.

Nursing Times; 103(10): 32-33.

Lesté, A. & Rust, J. (1984) Effects of dance on anxiety. Percept Mot Skills; 58(3): 767-772.

814.7K

Shares

Jennifer Delgado

I am a psychologist and I spent several years writing articles for scientific journals specialized in Health and Psychology. I want to help you create great experiences. Learn more about me.

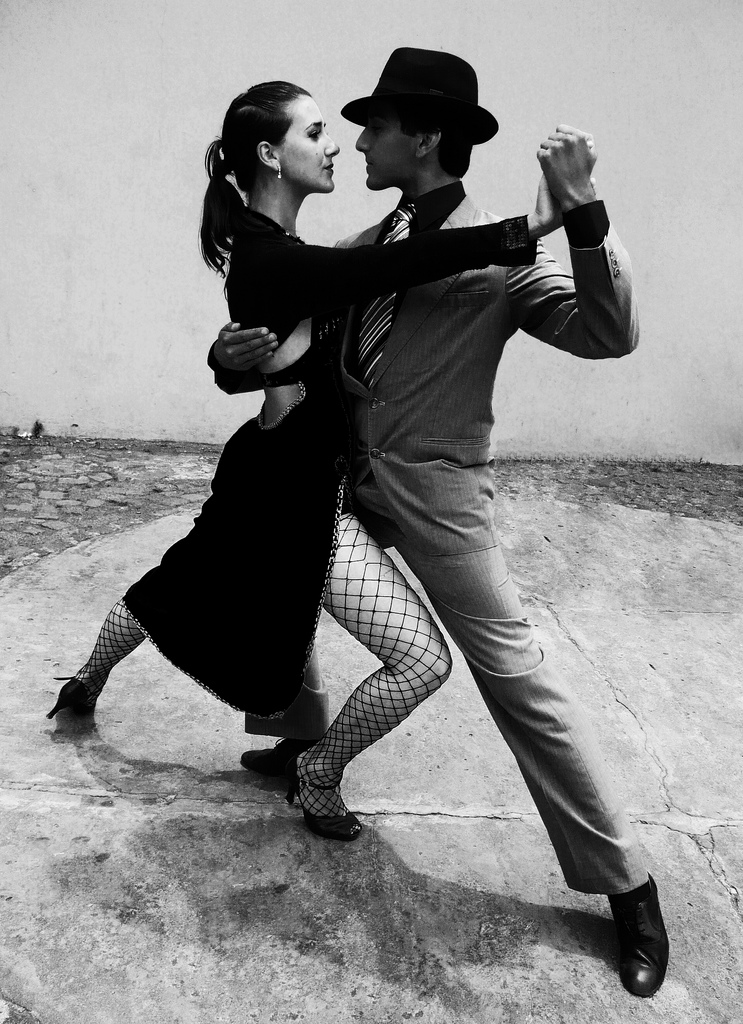

Dances of Emotions

But the possibilities of dance as a peculiar way of linking the body, mind and psyche into a single whole, of course, people guessed before. The dance was used for ritual purposes (shamans and healers of all parts of the world with its help achieved “enlightenment”, which allowed them to communicate with spirits), was used as a sign of belonging and belonging to their tribe, was an important element of communication and a way of transferring knowledge (for example, in the Ancient In Egypt, with the help of dances, they depicted the movement of heavenly bodies), performed a cathartic function, being a way of defusing, relieving emotional and physical stress, or, conversely, helping to mobilize one’s condition and raise morale before hunting or battle.

During the late Middle Ages, the dance was divided into folk dances and special performing arts. Later, dances lost their original meaning and turned into secular entertainment, and then became the property of professionals. The ability of dance to be a natural continuation of human movement, to reflect the emotions and character of the performer was truly noticed again only at the beginning of the 20th century thanks to the emergence of free characteristic dance, the founder of which was the famous American dancer Isadora Duncan, including in our country. She abandoned the formalities of classical ballet and began to dance barefoot, expressing herself in the dance, rather than playing someone else's role. She was convinced that the state of mind of a person is directly related to bodily movements, and pain, resentment, failures and disappointments - all this can be simply “danced” out of oneself. In a characteristic dance, the importance of personal, expressive self-expression was emphasized and the possibility of addressing the themes of the unconscious arose.

Since 1942 dances and dance movements have been officially used in medicine. It was in this year that psychiatrists took notice of the classes that Marian Chase taught and invited her to try her methods with hospitalized psychiatric patients at St. Elizabeth's Hospital. At that time, the practice of collective therapy was developing very actively in medicine, and dance-movement therapy was the best fit for the new trend. After a kind of "dance" treatment, patients who were considered hopeless (regressive, non-speaking and psychotic patients, schizophrenics) were able to express their feelings and joined in group interaction, which allowed doctors to move on to traditional types of psychotherapy for these patients.

© Marian Chace Foundation

Marian Chace (pictured in black) works with patients at St. Elizabeth's Hospital.

As one of Marian Chase's students, who happened to observe her work in the hospital, later recalled, “she approached her duties very diligently and scrupulously. During my training years, I accompanied her to closed rooms, moving a huge record player. Entering the ward, Marian immediately analyzed the habits of patients: how they greeted each other, what they said, how they nodded their heads. Then, in the common hall, she watched how patients communicate with each other, how they unite in groups, what moods reign. After that, she decided where to start work. When everyone gathered, she greeted each one separately and explained in detail who she was and why she had come. She usually suggested starting with a waltz, a neutral dance and, as she noticed, often not laden with memories. Some immediately joined the circle she created, and for those who did not immediately decide to take part in the general dance, she gave time to muster up courage. However, even those who were always on the sidelines got their fair share of attention and participated in the group session in their own way. Depending on the characteristics of the group, the work could be intense, energy-intensive, fun or confidential.

During my training years, I accompanied her to closed rooms, moving a huge record player. Entering the ward, Marian immediately analyzed the habits of patients: how they greeted each other, what they said, how they nodded their heads. Then, in the common hall, she watched how patients communicate with each other, how they unite in groups, what moods reign. After that, she decided where to start work. When everyone gathered, she greeted each one separately and explained in detail who she was and why she had come. She usually suggested starting with a waltz, a neutral dance and, as she noticed, often not laden with memories. Some immediately joined the circle she created, and for those who did not immediately decide to take part in the general dance, she gave time to muster up courage. However, even those who were always on the sidelines got their fair share of attention and participated in the group session in their own way. Depending on the characteristics of the group, the work could be intense, energy-intensive, fun or confidential. The whole range of emotions was expressed in movements, and sometimes verbally. Each person left the session with a clearer sense of their Self and their connection with others, even if at first a sense of isolation prevailed, because Marian watched every movement very carefully and respectfully, giving her conscious response to the symbolic expression of patients in movement.

The whole range of emotions was expressed in movements, and sometimes verbally. Each person left the session with a clearer sense of their Self and their connection with others, even if at first a sense of isolation prevailed, because Marian watched every movement very carefully and respectfully, giving her conscious response to the symbolic expression of patients in movement.

Chase's idea was further developed by other choreographers who began to use dance as a way to treat people with "war neurosis" and normal and neurotic clients. However, it was not until the late 1950s that the beginnings of dance movement therapy theory and the first teaching programs began to appear, as most of the early dance therapists were professional dancers, not doctors or scientists. Finally, in 1966, the American Dance Psychotherapy Association was established, and this date is considered to be the beginning of the development of dance movement therapy as an independent discipline. Some time later, a similar association appeared in Europe, and in 1995 - and in Russia.

The first dancers-therapists acted mainly by intuition, only noticing that the state of their students or patients changed after dancing, and then somehow systematized these observations. But later, a certain scientific work was carried out, which made it possible to identify the psychophysiological mechanisms of the influence of dance on the human body and confirm the early conclusions.

Probably any dance has its therapeutic effect (at the very least, a person’s pulse speeds up, blood vessels dilate, blood is saturated with oxygen - everything is like with good cardio training), but this does not mean that it can be used as part of a dance - movement therapy, since in this case the achievement of a therapeutic effect is based on very specific principles:

- body and mind are inseparable and have a constant mutual influence on each other;

- in the dance a person communicates with himself, with other people and with the world;

- the triad "thoughts-feelings-behavior" is a single whole and changes in one aspect entail changes in the other two;

- the body is perceived as a process, not as an object or an object.

In this form, dance movement therapy has been successfully used for all forms of neurosis, childhood autism, learning disorders, mental disability or senile dementia (including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's).

Another important value of dance movement therapy is the possibility of its use for personal growth. Such classes are held for people who do not suffer from problems, but want to achieve something more in their lives. In this case, dance becomes a way of recognizing oneself and one's special individual qualities. It helps to realize the hidden possibilities of the body, expand the idea of oneself, find new ways of self-expression and interaction with other people.

Currently, dance movement therapy is developing in several directions, and one of the most popular is the Rio Abierto movement, founded more than 60 years ago by the Argentine Maria Adela Palkos. We managed to ask a few questions about this movement to Maria Adela herself, as well as to her Russian student, Elya Mullagaliyeva.

– Maria Adela, how did you come to create Rio Abierto, what was the impetus for doing it?

Maria Adela (MA): It all started a long time ago - when I was still very young. The world then was completely different - it was under a very strong influence of Western culture, which was much more tangible than now. Mind plays a dominant role in Western education. You need to provide him with as much information as possible, enlighten him and in a sense obey him. Hence, a clear division appeared: an intelligent person should engage in intellectual work, and those who did not succeed in this should learn to work with their bodies, becoming athletes, workers, and so on. Smart athletes did not fit into this scheme.

I myself grew up in a very intellectual family. Friends of my parents often gathered in our house, many of whom were university professors. I talked to them a lot, and they had a very big influence on me intellectually. But since childhood, I have been inherent in the desire for a sense of joy and freedom. My mind wanted something, imagined something, but the body, as it turned out, did not fully obey it - there was a certain mismatch between them.

My mind wanted something, imagined something, but the body, as it turned out, did not fully obey it - there was a certain mismatch between them.

I stubbornly searched for answers to those questions that tormented me, reading philosophers and books on oriental practices (these books, it must be said, were very few at that time). But the greatest role in my life was played by meetings with those people whom I now call my teachers. At the age of 15, life brought me together with Anibal Sabatini. Much of what we talked about and discussed with him then formed the basis of Rio Abierto later: culture, understanding of personality, understanding of the “false” personality, and much more. A little later, from 1952 years old, I began to study in the rhythmic gymnastics classes of Suzanne Milderman. She was engaged in research in the field of work with the body, leading to psychophysical transformations, as a result of which, by 1950, she created a system of expressive rhythmic gymnastics. Among her students were doctors, kinesiologists, psychologists, ballerinas, dancers, actors. In 1961, Milderman closed the doors of her class so that each of us - her students - would find their own future path on their own. I began to gather around me like-minded people who were interested in doing this, opened my own class, and after a short time, at 1966, registered the organization Fundacion Rio Abierto, and already began to train instructors herself.

Among her students were doctors, kinesiologists, psychologists, ballerinas, dancers, actors. In 1961, Milderman closed the doors of her class so that each of us - her students - would find their own future path on their own. I began to gather around me like-minded people who were interested in doing this, opened my own class, and after a short time, at 1966, registered the organization Fundacion Rio Abierto, and already began to train instructors herself.

Suzanne Milderman's rhythmic gymnastics class in the 80s.

Elya Mullagalieva (E.M.): Suzanne Milderman, by the way, was largely inspired by Isadora Duncan and her approach to dance - that dance should be a natural expression of music, and that the dancer feels. From here comes one of the key concepts - "expressiveness", which Milderman used in her system - "expressive rhythmic movement". Marie Adela calls this "expressive movement of life." That is, in a sense, they even move away from the concept of "dance" as such, introducing some new meanings and definitions.

– What goals did you set for Rio Abierto, what did you try to achieve with it?

MA: From childhood I was surrounded by intellectual people. But it seemed to me that they had no contact with certain aspects of their own personality, that their emotional world did not develop at all. I firmly believe that we must develop all the aspects with which we are endowed: intellectual, physiological, emotional, instinctive, creative imagination, including musical or artistic sensibility. We are multidimensional, and therefore it is very important to develop ourselves as a harmonious personality. I wanted to integrate mind, body and emotions into one whole and help others to do the same - those who want it.

As a rule, our days are filled with a series of automatic actions, many of which we are not even aware of. This greatly distorts the perception of ourselves and leads away from understanding who we really are, what we want and where we can go.

– Today the practice of division of labor is extremely important. The reality is that if a person is engaged in many things at once, then he will not succeed as a specialist - there is simply not enough time to understand everything well...

The reality is that if a person is engaged in many things at once, then he will not succeed as a specialist - there is simply not enough time to understand everything well...

М.А.: I think that harmonious development cannot be transferred to division by specialties, it's a bit about different things. If it is important for a person to develop in a chosen direction, let him receive a special education. But a person must first learn to be a person, and only then - a chemist, artist, football player or someone else. The very fact of striving for harmonious development makes him a man. And we are all committed to this. Without this, it is impossible to become completely happy.

In our culture, we develop primarily as intellectuals. At the same time, there is no way to express emotions, but they continue to act within us, often against us. We spend a huge amount of energy on holding back tears, sadness, amazement, screaming... For many, this becomes not just an obstacle in revealing their potential, but leads to illnesses, and sometimes very serious ones. The idea of Rio Abierto is to see all the potential that a person has, to meet all his possibilities. However, we are not concerned about the final result. Here they do not offer: if you want to be a scientist, we will develop the mind, if you want to be an artist, we will develop sensitivity. This is an invitation to know yourself.

The idea of Rio Abierto is to see all the potential that a person has, to meet all his possibilities. However, we are not concerned about the final result. Here they do not offer: if you want to be a scientist, we will develop the mind, if you want to be an artist, we will develop sensitivity. This is an invitation to know yourself.

© Rio Abierto archive

© Rio Abierto archive

© Rio Abierto archive

– How does dancing help this? Why movement, and, for example, not a conversation with a psychotherapist?

MA: The body provides contact with the senses. An upbringing that suppresses feelings and the expression of emotions leads to the emotional scarcity that is characteristic of modern Western man. What cannot be expressed remains in the body as a block and gradually destroys it from within. The body also has sensitivity - the ability to give a sense of what is bothering us. In movement classes, we go through conflicting and even antagonistic qualities and states of mind before we can put it into words. That is, before we move on to the expression in words, we already have a bodily awareness of the manifested qualities, they are no longer absolutely alien: "I have already observed myself and recognize them for myself." Movement makes the mind listen to the body. The mind, which perceives the signals of the body, becomes its ally.

That is, before we move on to the expression in words, we already have a bodily awareness of the manifested qualities, they are no longer absolutely alien: "I have already observed myself and recognize them for myself." Movement makes the mind listen to the body. The mind, which perceives the signals of the body, becomes its ally.

In addition, expressive movement affects not only muscles, joints, blood circulation, but also the course of emotions, experiences, and the human nervous system. It allows every aspect of our being to make its own movement, and thereby receive the necessary charge.

© Rio Abierto archive

© Rio Abierto archive

E.M.: Through movement, a person learns something new about himself. And this is always more valuable than when some specially trained person explains the same thing to you. Through movement, we discover our fixations and blocks - what causes stiffness, tension and pain. These things are projected onto other aspects of our lives: stiffness manifests itself in relationships or the initiative to act, tension in communication or performing both physical and mental actions, soreness in relationships, traumatic situations, or already developed organic disease.

By liberating the body, we stop being a prisoner of dominant states. The flexibility of the body is projected into the psyche, making mental processes more flexible: sensations, imagination, thinking. Therefore, we say that this system is aimed at developing human potential. Man is generously endowed with many things. But it is necessary to remove the restrictions imposed on him in the process of upbringing or due to distortions in education (in the direction of developing only logic, attention, memory). "Caring" restrictions from childhood lead to the fact that we lose confidence in our own body, in our abilities.

– How are classes at Rio Abierto?

E.M.: The hosts prepare music in advance, which could contribute to the manifestation of the most diverse states, the most diverse emotional shades. My task as a teacher is to develop bodily flexibility in people, and through it - emotional and mental flexibility. This can be done by taking people through different moods, from something fun, joyful, lively to maybe even aggressive.

At the beginning of the lesson, the facilitator turns on the music and sets an example with his own movements. It doesn't have to be any typical dance moves. Much more often it is quite the opposite - movements become the result of the emotional state that the leader is experiencing at that moment. As a rule, everything starts with rhythmic, energetic music: we walk, stomp, jump. This is due to the fact that from the very beginning a person must feel, find support - and not only physical (the floor in the studio), but also psychological, internal support. This is a very important aspect, because if you have something to rely on inside, then then you do everything differently, more efficiently: you think, act, build relationships.

The first thing I ask people to do is repeat the movements like children do. We all once learned to do something simply by copying adults, and in the classroom we return to our natural mechanism of cognition: the leader sets the movements, and everyone else in the circle repeats it. In ordinary life, a person does not allow himself, for example, to wave his arms in the same way or clench his hands into fists, as he does here, repeating the movements after others. And this triggers in him emotions associated with the same clenching of the fist - everything that he may have suppressed in himself, because in childhood he was forbidden to do so. And here the whole layer of desires to show strength, protect oneself or do something else, which was once voluntarily or involuntarily hidden, can be revealed. But the problem is that this "layer" has not gone anywhere - it sits inside a person like a compressed spring.

In ordinary life, a person does not allow himself, for example, to wave his arms in the same way or clench his hands into fists, as he does here, repeating the movements after others. And this triggers in him emotions associated with the same clenching of the fist - everything that he may have suppressed in himself, because in childhood he was forbidden to do so. And here the whole layer of desires to show strength, protect oneself or do something else, which was once voluntarily or involuntarily hidden, can be revealed. But the problem is that this "layer" has not gone anywhere - it sits inside a person like a compressed spring.

So during the lesson we can feel sad, laugh at something – that is, live with a wider range of emotions. We give them an outlet so that at some point each participant can manifest their own Self - that which fills them now.

© Rio Abierto archive

© Rio Abierto archive

© Rio Abierto archive

This is how all lessons go. Moreover, we do not know in advance what each participant will come to in the middle of the lesson - for us this is a big mystery and an opportunity to plunge into something new. By the end of the lesson, the leader necessarily leads everyone to an even, harmonious state. But there are also more complex courses, combined, for example, with a variety of joint discussions and reflections.

Moreover, we do not know in advance what each participant will come to in the middle of the lesson - for us this is a big mystery and an opportunity to plunge into something new. By the end of the lesson, the leader necessarily leads everyone to an even, harmonious state. But there are also more complex courses, combined, for example, with a variety of joint discussions and reflections.

- What is the main reason people come to Rio Abierto - do they really want to reach their potential or do they really want to solve some existing psychological problem?

E.M.: When a person comes to Rio Abierto, it means that he has hit a point of imbalance and wants to change something. I myself once came to classes because I had health problems, and I wanted to deal with them. Some come in the hope that they are moving and their body will change, others - to cheer up their mood, others - to learn to better control themselves. But in the process, they all find themselves changing much more. Usually, by the middle of the session, people begin to move on their own, following their inner impulses, and suddenly someone starts saying: “I just realized that I am not allowing my children to express themselves, to reveal themselves.” Someone picks up: “But I impose my rules on everyone and I can’t stand it when they are not followed.” And so, when you yourself discover this and begin to recognize it in yourself, then, having come home, you already quite calmly perceive the fact that your child does not listen to all the wisdom that pours out of you. Gradually you accumulate more and more "acceptance", and the space, the boundaries into which you can let other people or other ideas, expand more and more. And because of this, a lot of things change in life.

Usually, by the middle of the session, people begin to move on their own, following their inner impulses, and suddenly someone starts saying: “I just realized that I am not allowing my children to express themselves, to reveal themselves.” Someone picks up: “But I impose my rules on everyone and I can’t stand it when they are not followed.” And so, when you yourself discover this and begin to recognize it in yourself, then, having come home, you already quite calmly perceive the fact that your child does not listen to all the wisdom that pours out of you. Gradually you accumulate more and more "acceptance", and the space, the boundaries into which you can let other people or other ideas, expand more and more. And because of this, a lot of things change in life.

MA: In fact, both of them have something in common, namely the feeling that they do not live the way they could. Therefore, many people answer the question why they came to Rio Abierto very simply: to change their lives for the better. They are trying to find more satisfaction in life and do what they really want - to be able to realize themselves, whether they are an artist, an engineer or a scientist.

They are trying to find more satisfaction in life and do what they really want - to be able to realize themselves, whether they are an artist, an engineer or a scientist.

How the dance affects the viewer • Episode transcript • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

Course What is modern danceAudio lecturesMaterialsContents of the fifth lecture from Irina Sirotkina's course "What is modern dance"

Watching a dance or sport is even more interesting if you yourself are involved in dance, gymnastics or sports. As it is often said, "art is in the eye of the beholder". I see what I see, what my eye sees. And the art of dance is also “in the body of the beholder”, because a person perceives dance not only with his eyes, but with his whole body. This lecture is about the sense of movement, kinesthesia. It, this feeling, not only allows us to move and dance, but also serves as a kind of radar, helping to pick up the movements of others and understand the art of dancing.

What is the sense of movement, kinesthesia, everyone knows from their own experience. Remember, for example, the pleasant sensations when you get up after a long sitting, stretch, stretch your numb body.

The term "kinesthesia" appeared relatively recently, in the 20th century. Before him, they talked about "muscular", "dark" or even "sixth" sense. Sixth - because traditionally, starting with Aristotle, it is customary to count five senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste. In the middle of the 19th century, the physiologist Ivan Mikhailovich Sechenov argued that when walking, the sensations from working muscles and from the contact of the foot with the ground or floor are important - the resulting feeling of support. Normally, if everything works well for us and nothing hurts, we are not aware of the work of the muscles, but only the movement itself. The sensations that a person experiences when moving, maintaining a posture, gesticulating, or tensing the vocal cords, as a rule, are not conscious or almost unaware. For this they were called a dark feeling and for a long time they were not separated from touch.

For this they were called a dark feeling and for a long time they were not separated from touch.

Compared to seeing or hearing, in which the source of sensations is external, kinesthetic sensations originate inside the body. The direct, immediate character of muscular feeling is its important advantage. As the same Sechenov wrote, muscular feeling "goes to the root." And according to the time of its occurrence, the "sixth" sense is actually the first. When an embryo grows in the mother's womb, it does not yet have sight and hearing, but it can already move. This means that he already has a muscular feeling; it is fundamental, basic, and all other feelings are built on top of it.

At the very beginning of the 20th century, the physiologist Charles Sherrington proposed to call the muscular feeling proprioception, and the neurologist Henry Bastien used the Greek word "kinesthesia" for the same: kinesis - "movement", aisthesis - "sensibility". Since then, this last term has firmly entered the scientific language and has already given rise to several derivative concepts: kinesthetic intelligence, kinesthetic empathy, and even kinesthetic imagination.

Since then, this last term has firmly entered the scientific language and has already given rise to several derivative concepts: kinesthetic intelligence, kinesthetic empathy, and even kinesthetic imagination.

The first of these concepts is kinesthetic intelligence. With the help of muscular sense, we perceive, in particular, spatial relations, thereby carrying out an elementary act of thinking about the relations of things in space. This act of thinking is colloquially called sometimes dexterity - the ability to cope with a motor task quickly and efficiently. And psychologists sometimes talk about motor talent and even measure this ability with special tests.

Dancers are well aware that "thinking" and "muscle" are close. American postmodern dancer Yvonne Rainer at 19In the 60s, she staged a dance, which was called: “The Mind Is a Muscle” (“Mind is a muscle”). Part of this composition, entitled "Trio A", consists of a repetitive series of simple, everyday movements: low jumps, arm swings, squats, and so on. All series are equivalent and follow each other without interruption. Movements are made slowly, under control, not relaxed, in real time and with real weight. The dancers do not stop their efforts and do not lose energy for a moment, showing the same endurance as long-distance runners. The spectator, according to the choreographer's idea, seems to be witnessing the work of the mind - not machine, but human rationality, operations of the mind, which in this case are performed through the body.

All series are equivalent and follow each other without interruption. Movements are made slowly, under control, not relaxed, in real time and with real weight. The dancers do not stop their efforts and do not lose energy for a moment, showing the same endurance as long-distance runners. The spectator, according to the choreographer's idea, seems to be witnessing the work of the mind - not machine, but human rationality, operations of the mind, which in this case are performed through the body.

Soviet physiologist Nikolai Bernshtein created the theory of movement construction and operationalized the concept of dexterity. Bernstein was referred to by the American psychologist, the author of the concept of multiple types of intelligence, Howard Gardner, when he spoke about bodily-kinesthetic intelligence ( bodily-kinesthetic intelligence ). Gardner defines bodily-kinesthetic intelligence as "the ability to control one's own movements and skillfully handle objects."

The idea of the corporeal mind has been in the air for a long time. In 1932, a book by the physiologist Walter Cannon called The Wisdom of the Body was published, and five years later his colleague Mabel Todd published The Thinking Body, about how to develop refined neuromuscular coordination with the help of creative mental imagery and conscious relaxation. Over the past half century, many systems for the development of the human motor sphere have appeared: the Franz Alexander technique, the Moshe Feldenkrais method, Thomas Hanna's "somatics", Lulu Sveigard's "ideokinesis" and others.

In 1932, a book by the physiologist Walter Cannon called The Wisdom of the Body was published, and five years later his colleague Mabel Todd published The Thinking Body, about how to develop refined neuromuscular coordination with the help of creative mental imagery and conscious relaxation. Over the past half century, many systems for the development of the human motor sphere have appeared: the Franz Alexander technique, the Moshe Feldenkrais method, Thomas Hanna's "somatics", Lulu Sveigard's "ideokinesis" and others.

This trend intensified after the Second World War, when people realized that the whole system of education had to be changed. As opposed to control, discipline and authoritarianism, it was necessary to recognize as a value such qualities as openness, awareness, reflection, creativity and freedom. Attention to the body, development of a sense of movement, awareness of the internal state have become the goals of new systems of bodily-motor education. They have replaced training systems based on obedience, discipline, and conformity. According to movement culture historian Georges Vigarello, in the practices that appeared after the war, the main role was assigned to the inner side of the movement, its self-perception. The new approach offered an in-depth study of oneself, awareness of one's body and movements, the use of imagination, visualization of different parts of the body and the formation of a holistic body image. Physiological thought followed the line of increasing confidence in what is called the bodily, moving mind.

According to movement culture historian Georges Vigarello, in the practices that appeared after the war, the main role was assigned to the inner side of the movement, its self-perception. The new approach offered an in-depth study of oneself, awareness of one's body and movements, the use of imagination, visualization of different parts of the body and the formation of a holistic body image. Physiological thought followed the line of increasing confidence in what is called the bodily, moving mind.

The second concept is kinesthetic empathy. Kinesthesia is not only a way to regulate one's own movements and interact with the world, but also the basis for understanding someone else's movement. As early as the beginning of the 20th century, the German art critic Hans Brandenburg argued that only those who themselves have “developed bodily awareness” can perceive the movements of a dancer. Looking at the dancer, the spectator allegedly makes imperceptible movements himself, which to some extent imitate the movements of the dance. Through kinesthetic sensations from his own body, he is able to better perceive this dance.

Through kinesthetic sensations from his own body, he is able to better perceive this dance.

At the end of the 19th century, the hypothesis that the ability to understand the movements of other people is determined by one's own motor experience was formulated by the German psychologist Theodor Lipps. He proposed the term "empathy" - empathy, entry into the inner world of another, empathy for him. And then he began to write about empathy at the level of the body, kinesthetic. According to Lipps, we perceive not only the movement of a living organism, a person, but also movement in general, “pure” or “abstract”, as if reproducing it in an internal plane, imitating it internally. This seems to be less about a literal, physical imitation of movement, such as a reflex flinching at the sight of another person flinching, than about some kind of kinesthetic experience. Simplifying, it can be compared with emotional sympathy, empathy: we ourselves do not directly experience the emotion that another person experiences, but, looking at him, we begin to empathize with her; we ourselves do not move, but, looking at the movements of another, we experience sensations reminiscent of those experienced by a moving person.

American critic John Martin called this ability metakinesis. If kinesis is physical movement, then metakinesis will be its inner, psychological side. Without this ability for kinesthetic empathy, Martin argued, the audience would have no more pleasure in seeing a ballerina balancing on one pointe shoe than in contemplating a feather floating in the air. The audience applauds the ballerina because they realize the force of gravity, which firmly holds them on the ground.

Kinesthetics allows us to feel the quality of tension in other people, helps us to guess the intentions of others - they are going to stroke us or hit us. Kinesthetics allow us to avoid bumping into other people as we walk down the street. This is a kind of physiological radar, thanks to which we feel impulses and intentions and react ahead of our consciousness, our thought. Theatrical people know that the kinesthetic feeling is the substance of any performance. It allows the viewer to follow the intentions of the performer, feel and often anticipate them without even realizing how it happens. Acrobatic tricks entertain the viewer at the level of his kinesthetic nature - one of the lower, muscular levels connects the viewer and the actor. Circus and acrobatic performances, built on the power of attraction or on a sense of balance, achieve such a powerful impact, which is often lacking in complex dramatic performances, despite their intellectual, aesthetic strength. That is why circus and street performers became a model for the theater reformers of the early twentieth century.

Acrobatic tricks entertain the viewer at the level of his kinesthetic nature - one of the lower, muscular levels connects the viewer and the actor. Circus and acrobatic performances, built on the power of attraction or on a sense of balance, achieve such a powerful impact, which is often lacking in complex dramatic performances, despite their intellectual, aesthetic strength. That is why circus and street performers became a model for the theater reformers of the early twentieth century.

Finally, in addition to kinesthetic empathy and intelligence, we can also talk about kinesthetic imagination. With its help, a person is freed from normative, habitual ways of moving and creates new motor "events". The motor nature of kinesthetic imagination was finally recognized relatively recently, at the end of the 20th century, thanks to the work of sports psychologists, as well as physicians who were rehabilitating patients with motor impairment or symptoms such as phantom pain. The researchers tried to show that motor imagination uses all the same parts of the brain as real movement. It turned out, however, that the activation of the motor system during kinesthetic imagination and that which occurs during motor excitation are not identical and only partially intersect. In addition, it was found that during the imagination of a particular movement, the activity of the motor cortex is weaker than during its actual execution.

It turned out, however, that the activation of the motor system during kinesthetic imagination and that which occurs during motor excitation are not identical and only partially intersect. In addition, it was found that during the imagination of a particular movement, the activity of the motor cortex is weaker than during its actual execution.

Kinesthetic imagination, says dancer and philosopher Maxine Sheets-Johnston, is necessary for both making movement and perceiving it. She gives the example of a person dancing in a circle, forming a certain shape, or "gestalt". His movements are perceived holistically. “We form an imaginary gestalt by representing each moment of the circle as a spatiotemporal present in relation to a spatiotemporal past and future,” she says. - The present is not isolated from the past and the future, it is a jump from the past to the future, a transitional moment in some space-time whole, even if only imaginary. This is not a sequence of images, but a single and inseparable circular line.

Practitioners also talk about ideomotor movement - imaginary, represented only in the mind: athletes, coaches, dancers. They use this concept to teach new skills. So, for example, before performing some complex movement, the student is first asked to repeatedly play it in the imagination.

Developed kinesthetic imagination is simply necessary for a choreographer who comes up with new movements and dances. A good choreographer does not just see patterns, images of eye movement - he feels them in his body. Or he trusts the dancer to find these patterns, who also looks for them, starting from his own kinesthetic sensations. This is how one of the most successful choreographers of our time, the Englishman Wayne McGregor, creates his compositions. He also likes to talk a lot about the role of kinesthesia and body thinking in dance.

More to read:

Bernstein N. A. Dexterity and its development.