How to count music for dance

Finding the 8 Count – Get Rhythm

QUICK PROMOTION: To help launch my new book on music, Hear the Beat, Feel the Music: Count, Clap and Tap Your Way to Remarkable Rhythm, the kindle is on sale for $2.99 (down from $4.99).

* Amazon ($12.95) * Kindle ($2.99 $4.99)

— Vince Lombardi, legendary Green Bay Packers coach

I’VE ALWAYS BEEN SUSPICIOUS OF THE COUNTING I HEARD IN DANCE CLASSES. I like numbers, and I’m a good counter, so it was odd. Dang it all, counting confused me! Fear not, I’ve expended endless calories, tortured and maimed untold brain cells and burned through thousands of dollars in dance lessons to make sense of this simple subject.

I believe part of the problem revolves around what is being counted. Although they’re related, counting music and counting step patterns are not the same. This chapter explores counting music; Chapter 6, “Counting Step Patterns,” looks at counting step patterns. For most people, especially men or anyone who believes he or she is rhythmically challenged, I believe learning to count, both the music and step patterns, is the gateway to intermediate-level dancing and above.

For me as a beginner, counting music was hard to pin down because—well, because nobody ever told me how to do it. Not only is it rarely taught in a class, except for one situation (when a teacher counts you in to start a dance, discussed at the end of this chapter), it’s rarely heard in class. And some teachers use musician lingo whenever they reference the musical count; that always threw me for a loop. Loops I didn’t need.

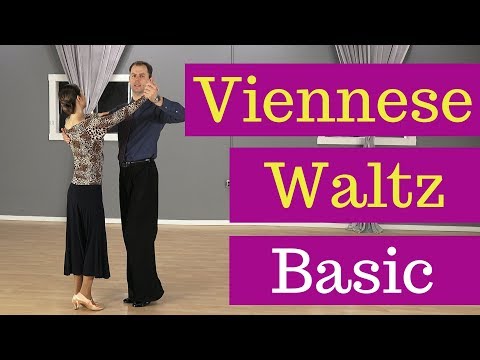

Counting music is counting the underlying beats of the music. Doing so reveals the structure of the music. It pertains only to the structure of the music—not the step pattern being danced—and virtually all dance music is counted the same. The one exception is waltz, which is covered on pages 74 and 124. When I refer to “virtually all dance music,” it means all dance music except the waltz.

The one exception is waltz, which is covered on pages 74 and 124. When I refer to “virtually all dance music,” it means all dance music except the waltz.

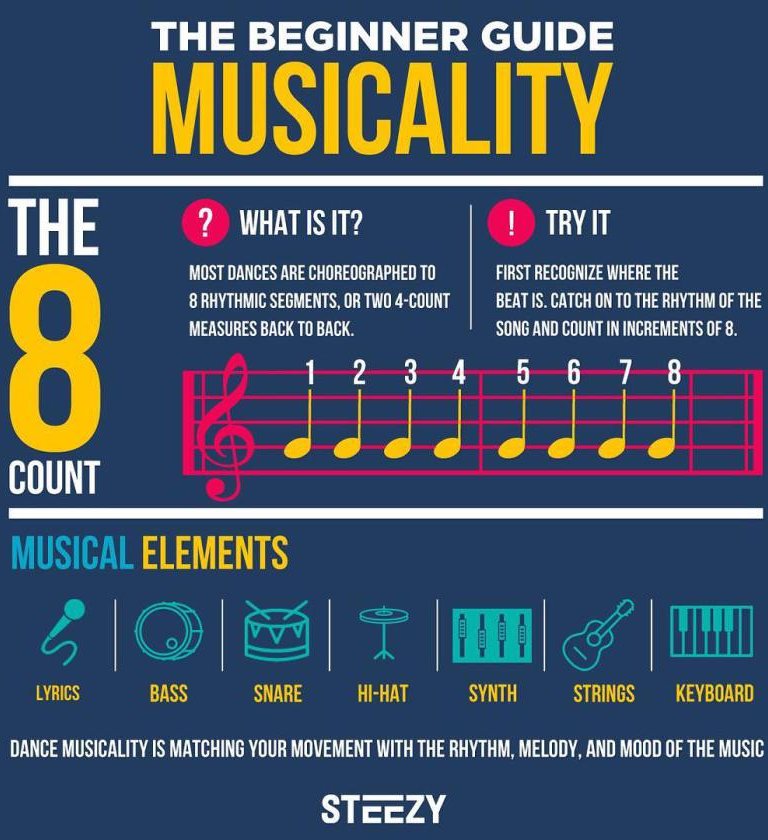

So, forget all the highfalutin-hieroglyphic-4/4-2/4-3/4-time-signature-mumbo-jumbo-music-theory you’ve been bulldozed with in the past. This is the only thing you need to know: virtually all dance music is counted in sets of 8 beats. It’s as simple as that. Sets of 8 exist because that’s how musicians compose the music; it’s how they give structure to the music. It’s the same way a sentence gives structure to the written word, as you’ll see in a moment. Sets of 8 are important to dancers for a number of reasons but most importantly because they identify and define the underlying beat of the music.

I remember the first time I ever heard the structure of music counted, with the help of John, a stranger at a bar. This was a big event for me. John caught my eye because the level of his dancing was high, higher than anything I’d ever observed in my local scene. I was dying to know his secret; so I approached him and asked why his dancing was so distinctive. He said he was connected to the music—through the count—and he demonstrated. We proceeded to listen to the house band, music I had listened to for years.

I was dying to know his secret; so I approached him and asked why his dancing was so distinctive. He said he was connected to the music—through the count—and he demonstrated. We proceeded to listen to the house band, music I had listened to for years.

He counted the music in sets of 8 beats. He counted 8 beats of music—“one two three four five six seven eight”—and then started over. He emphasized each count 1 of the music, the first beat of each set of 8, by punching the air with his hand. (And, to a lesser degree, he also emphasized each count 5, the fifth beat of a set of 8, with a smaller punch.) With the help of his hand motions I could hear that all the count 1s were, indeed, naturally emphasized in the music. (Lingo Alert: Sometimes the word “count” is omitted and a count 1 is identified as “the 1 of the music” or just “the 1.”) Moreover, I could hear that the 1s were beginning points that signaled the beginning of something new in the melody. The concept of a beginning point was subtle; but if someone identified it for me, I could hear it.

The concept of a beginning point was subtle; but if someone identified it for me, I could hear it.

He kept track of the sets of 8 as they passed, and he identified the bigger structure of the music. He predicted and caught all the big accents and breaks in the music with his hand motions—music he claimed he was not familiar with. This went on for song after song and, with his guidance, I could hear that every song had the same basic structure of sets of 8. I thought that maybe it was a trick; perhaps he was the band’s manager or something. Nope. He was just a stranger, first time in town, first time at this joint.

Not only did every song have the same structure, he claimed most popular music had this structure of sets of 8. Nahhh . . . impossible . . . surely it worked only for these songs because, well, they’re all from the same band or something. I couldn’t believe it would work for all songs—could it? Is it possible that I had danced for years oblivious to the common structure in virtually all dance music? Was I that detached from the music that no matter how many songs passed me by I couldn’t hear the structure that now screams at me? It’s remarkable that in seven years of dance lessons, nobody had done this demonstration for me before.

While it took time before I could count sets of 8 on my own to a broad spectrum of music and test this earth-shattering hypothesis, he was right: All dance music, except waltz, shares a similar structure. Heck, most popular music, even the gnarliest rock or rap you’ve ever heard, probably shares the same repeatable, predictable sets of 8 as dance music.

Sets of 8, which identify the underlying beat and reflect the true structure of the music, are the foundation of counting music. For beginners, counting music is done off the dance floor when you’re not dancing, to help you connect to the music. Counting is simple: listen for any count 1 to start, then count 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. Then start over. If you want to count how many sets of 8 go by, count the second set like this: 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8; count the third like this: 3, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8; count the fourth set like this: 4, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and so on. In this book, a set of 8 beats looks like this (note that they’re in pairs, which will make sense after you read the next two chapters):

Whether you can hear sets of 8 or not, sets of 8 are “in” the music. Once you develop your ear, which you will over time, a set of 8 will stand out, with integrity, in much the same way a sentence stands out from within a paragraph. Like the written word, music has themes and these themes are directly related to the musical count. In fact, if the song has vocals, sometimes a sentence or phrase of words aligns with a set of 8.

Once you develop your ear, which you will over time, a set of 8 will stand out, with integrity, in much the same way a sentence stands out from within a paragraph. Like the written word, music has themes and these themes are directly related to the musical count. In fact, if the song has vocals, sometimes a sentence or phrase of words aligns with a set of 8.

For me, hearing sets of 8 is a two-part approach. First, using a more left-brain-linear-analytical approach, I try to identify the count 1s, the first beat of a set of 8. A count 1 stands out because it typically has an emphasis or accent. It also stands out because it’s a beginning point for a piece of the melody or other thematic element; it sounds like a natural place to start something. It’s the same type of feeling you get at the start of a new sentence.

Second, using a more right-brain-holistic-intuitive approach, I listen to the overall melody of the music and try to hear the whole sentence (the whole set of 8). If I can hear, thematically, that I’m coming to the end of a sentence in the music, then I can feel when the next sentence will start. If I predict correctly, it gets confirmed by hearing the accent on the next count 1 and the feeling that, thematically, a new sentence has started. Today, this method, feeling the music, is the primary way I connect to the sets of 8, and much of it is done subconsciously, without thinking. Lingo Alert: I’m going to pull a fast one with language: Don’t tell any musicians but, for convenience, I tend to use the word melody generically to mean the themes I hear in any of the three components that combine to make a piece of music—melody, harmony or rhythm (drums).

If I can hear, thematically, that I’m coming to the end of a sentence in the music, then I can feel when the next sentence will start. If I predict correctly, it gets confirmed by hearing the accent on the next count 1 and the feeling that, thematically, a new sentence has started. Today, this method, feeling the music, is the primary way I connect to the sets of 8, and much of it is done subconsciously, without thinking. Lingo Alert: I’m going to pull a fast one with language: Don’t tell any musicians but, for convenience, I tend to use the word melody generically to mean the themes I hear in any of the three components that combine to make a piece of music—melody, harmony or rhythm (drums).

So what’s the catch? Hearing the count 1s and the sentence structure in the music is hard. If it were easy to hear I would have heard it on my own and you would be able to hear it on your own and we could all drop this book and go dance. Even after I realized that sets of 8 existed, it took many, many months of listening and practicing and getting confirmation from others before I could hear the structure and it became second nature. Until I could confidently count sets of 8, I was never 100 percent certain I was on the beat.

Until I could confidently count sets of 8, I was never 100 percent certain I was on the beat.

The Musician’s Measure

I wanted to label this discussion on the musician’s measure as an Advanced Info Alert as it may be too much information. I hate to burden the beginner with musical terms. But measure gets tossed around a lot among dancers, and understanding it will do a lot to help you hear the sets of 8.

A measure, a musical term, is a unit of time that counts virtually all dance music in groups of four beats. That’s how musicians deal with dance music, and there are dancers who follow this path of four. It’s a workable system for dancers . . . nahh, I take that back; just stick with sets of 8. They’re easier and more accurate. Even professional dance choreographers and aerobics instructors use sets of 8, also called a “dancer’s eight,” to choreograph their routines.

Actually, measures are naturally paired. So a set of 8 is just a combination of two four-beat measures, but sets of 8 work better for dancers because they’re more closely aligned to the natural structure.

Think of the pairing of measures this way: Break a pencil in half. It’s still the same pencil, and you can write with it. But it’s easier to work with the whole pencil. Musicians compose music half a pencil at a time, but their goal is to create a whole pencil. It’s easier for dancers to just look at the whole pencil. So, thematically, a four-beat measure, while it has some integrity on its own, sounds incomplete, like half a sentence.

The order matters in the pairing of measures. There’s the first half, the measure that begins the set of 8, counts 1 to 4; and there’s the last half, the measure that ends the set of 8, counts 5 to 8. To hear the correct order, listen to the melody, especially the feeling that the first measure begins something and that the last measure ends it. Also, listen for the relative difference in emphasis on the count 1 and the count 5. The point to note is that the count 1 has a stronger accent than the count 5, which will help you distinguish between the 1 and the 5.

(Recall from earlier, I said that John, the stranger who first helped me count music, also punched out the 5s with his hand, but to a lesser degree.) The order can be subtle—often very, very subtle—but it’s there, even if you can’t hear it. Like sets of 8, the natural pairing of measures is just in the count of the music.

Hearing accented beats, measures and sets of 8 is tricky. Depending on the music, there can be a lot going on or very little going on, which makes the process tough. But once you get it, it’ll become second nature.

Arcane Technical Info: Some dancers count tempo in measures per minute (MPM). Multiply MPM by four to get beats per minute (BPM). Most dance music falls in a range of, say, 80 to 160 BPM, which would be 20 to 40 MPM.

TIP: Sometimes vocals line up nicely with the sets of 8, sometimes not. Sometimes the accent on the count 1 is an accented vocal, sometimes not. The beat of the music is established by the percussion instruments, like drums. In general, don’t get distracted by lyrics.

In general, don’t get distracted by lyrics.

ANOTHER TIP: When practicing the beat, in addition to counting, it’s always good to get some body movement. While tapping your foot is okay, the most effective way to train your body to feel the beat is marching in place, doing a weight change on every beat of music.

Freebie Video: Check out my website (ihatetodancec.com and HearTheBeatFeelTheMusic.com) for some video clips, which will help you count sets of 8.

What’s so important about counting the musical structure? For me as a beginner, there were three elements. First, hearing the structure was a big step toward connecting to the music, which is what separates the poseur from the real dancer. Second, if I could hear the structure—if I could count sets of 8—I could confirm that I was on the beat. This was sweet: I no longer had to annoy friends and accost strangers with pleas to help me with the beat. Now, if I can’t count sets of 8, I know that I’m either off the beat or it’s a waltz or it’s not dance music.

This was sweet: I no longer had to annoy friends and accost strangers with pleas to help me with the beat. Now, if I can’t count sets of 8, I know that I’m either off the beat or it’s a waltz or it’s not dance music.

Finally, it answered one of the more troubling aspects of dance for me as a beginner: When, exactly, do I start a dance—when do I take the first step? Let me explain. The count 1 of any set of 8 is the best place to start a dance, because it feels like the beginning of something. While you can start a dance on any odd beat (counts 1, 3, 5 and 7), it will feel best if you start on a count 1. A count 5, the beginning of the second measure, is the next best choice. Generally, a follower expects you to start on a 1 or a 5. If you don’t, you may surprise her and it’ll be an awkward start.

Teachers always start a class dancing on a count 1 of the music. For now, pay attention as your teacher counts you in to start a dance. This is probably the only time you’ll hear music counted and you’ll usually hear just four to eight beats of it. Invariably, the teacher will start the music and then count something like “ . . . and a five six seven eight,” and you will take your first step on the next beat, the count 1 of the next set of 8. Any other counting a teacher does is probably counting step patterns, not the music.

For now, pay attention as your teacher counts you in to start a dance. This is probably the only time you’ll hear music counted and you’ll usually hear just four to eight beats of it. Invariably, the teacher will start the music and then count something like “ . . . and a five six seven eight,” and you will take your first step on the next beat, the count 1 of the next set of 8. Any other counting a teacher does is probably counting step patterns, not the music.

I still remember the feelings of being lost, standing motionless on the floor, like a statue, waiting uncomfortably, sometimes straining to hold back the sweat, trying to discern when to start. I danced for years feeling awkward about jumping into a dance because I didn’t know that virtually all dance music is structured in sets of 8 creating natural, predictable places to start. I found it interesting that teachers knew just where to start, but I figured that’s why they were the teachers—they had a gift—and I was the inept student. Sure, I guess I heard sentences in the music, but I didn’t know these sentences were so regular, consistent and predictable. I thought music was more random, always different. I now know this ignorance kept me from connecting to the music and stuck at the beginner level, in a rut.

Sure, I guess I heard sentences in the music, but I didn’t know these sentences were so regular, consistent and predictable. I thought music was more random, always different. I now know this ignorance kept me from connecting to the music and stuck at the beginner level, in a rut.

Please, no tears.

EXERCISE 1: Count Sets of 8

To get started, spend time with a teacher or friend listening to a variety of music. You can listen to your own music collection; but also surf the radio dial and music websites that let you sample music, as listening to unfamiliar songs is an important part of the process. Count the sets of 8. If a song stumps you, move on quickly, because you have to hear it in the easy pieces before you can hear it in the harder stuff. Do the count 1s stand out? Do the 1s and 5s seem to have the same emphasis? The beat with more emphasis, however subtle that may be, is the 1. If you have a hard time hearing the beat, plan on sticking with this exercise for many months, working both on your own and with occasional confirmation from others.

Advanced Info Alert: Intro to Phrasing

Phrasing, the way dancers use the word, refers to the structure of the music. While phrasing is not for newbies, I believe beginners who have had a few months of classes should begin to develop an ear for it. I’ll be gentle.

One set of 8 is also called a mini-phrase, a term coined by dance educator Skippy Blair. To the ear, a set of 8 or mini-phrase usually has a theme: a short piece of melody or harmony with a beginning and an ending. The themes of mini-phrases have some integrity, but they don’t tell the whole story. A mini-phrase, like a sentence of words, only tells part of the story.

Music also has “paragraphs.” A paragraph in music is often called a phrase of music or, more descriptively, a major phrase. Just as a paragraph is a series of sentences, a major phrase is a series of mini-phrases. To the ear, the theme of a major phrase typically encompasses the smaller themes of the mini-phrases to create a larger theme, which tells the whole story—a complete musical thought.

For example, a group of mini-phrases can come together to form a chorus or verse, which is thematically complete.

Unlike the mini-phrase, which is always eight beats (except waltz music), the number of beats in a major phrase will vary depending on the music. The most common major phrase is the 32-beat phrase, which is sometimes described as “four sets of 8” (4 × 8 = 32), easy to hear in everything from jazz to Latin to rock ’n roll. Also common is the 48-beat phrase, which can be described as “six sets of 8” and is considered standard phrasing for blues music. (Arcane technical info: Musicians call it 12-bar blues, a bar being slang for a four-beat measure: 12 × 4 = 48.)

Phrasing is important, because at the intermediate level and above you will dance to the major phrases. You will choreograph step patterns in a way that acknowledges the major phrases, which will connect you to the music at a higher level. And women will love you for it.

Freebie Video: There are some short videos on my website that count out 32-beat phrases.

Copyright © 2010 – 2018 James Joseph. All rights reserved.

How to Count Music • Dance Papi

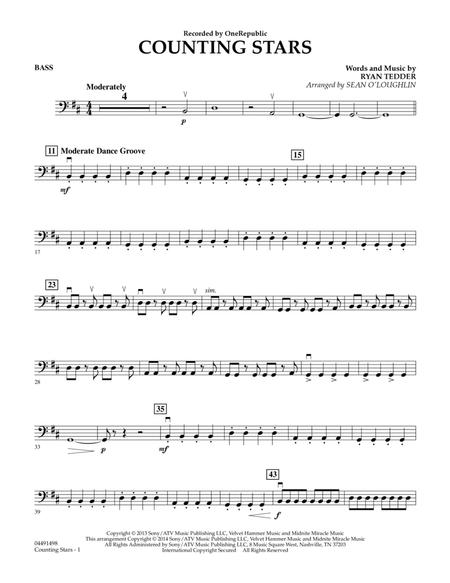

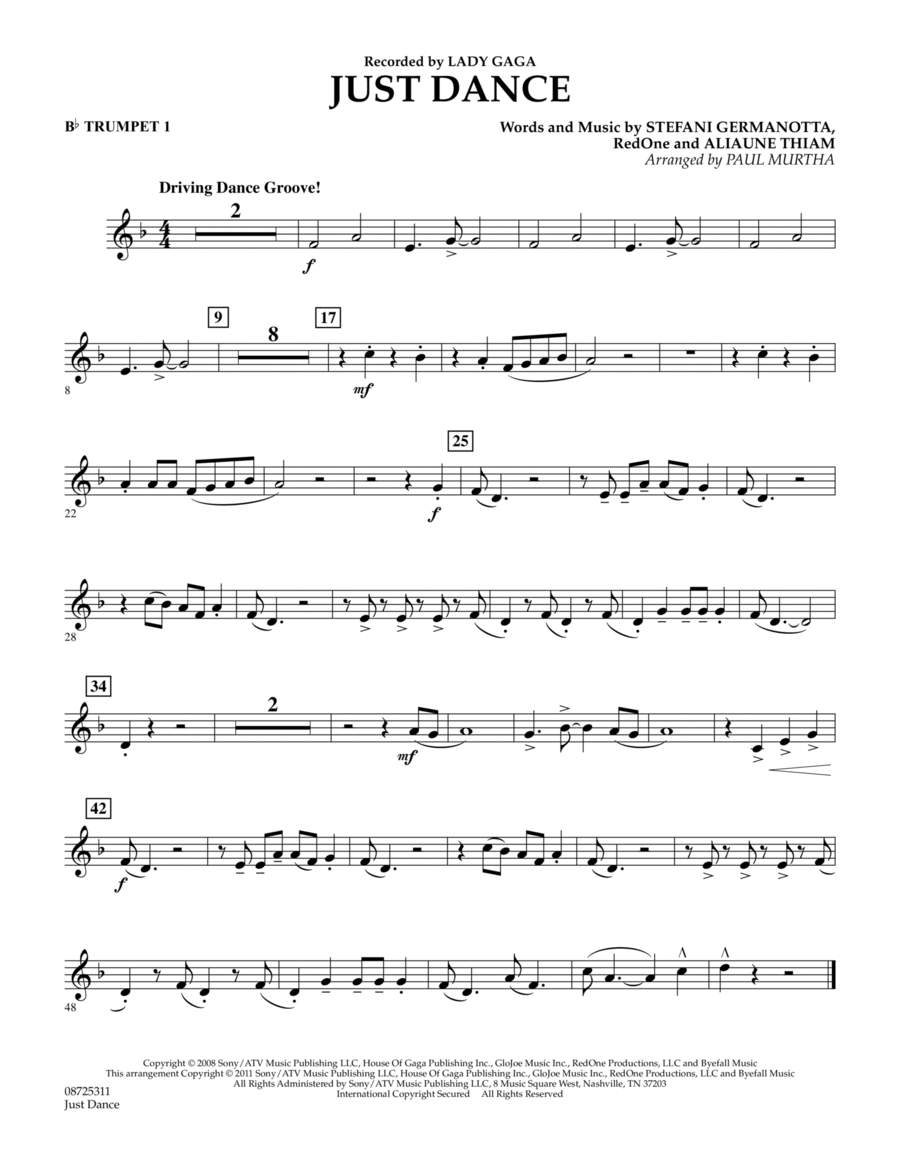

Salsa is danced to a 4/4 count—but what the heck does that mean? Counting music is most easily achieved if you know how to read music (so you’re already ahead if those jazz band years in middle school still ring a bell). If not, don’t worry. Learning the value of each note is pretty easy. The graph below, a copyright-free image compliments of Wikimedia commons, shows you what each note requires to make a count of four:

The top value is one whole note, the second is two half notes, the third is four quarter notes, the fourth is eight eighth notes, and the last is 16 16th notes. You can get much more in-depth when it comes to reading music, including understanding time signatures that dictate beats per measure and the value of each beat, but that’s likely way more information than the average salsa dancer is seeking out.

Listen to Your Gut (and the Music)

Counting aloud is the best way to decipher beats and counts. You’ve heard salsa instructors start a dance with “one and two and three and four and …” or “one, two, three four,” to help everyone pinpoint the music’s beat. Really, they’re just sub-dividing quarter notes in a recognizable manner. Practicing at home yourself, listening to salsa music, is the best way to teach your ear to pick up 4/4 beats.

You’ve heard salsa instructors start a dance with “one and two and three and four and …” or “one, two, three four,” to help everyone pinpoint the music’s beat. Really, they’re just sub-dividing quarter notes in a recognizable manner. Practicing at home yourself, listening to salsa music, is the best way to teach your ear to pick up 4/4 beats.

Wait a minute. What does 4/4 even mean?

It’s pretty simple. 4/4 means there are four beats per measure. Oftentimes in salsa, the beats are four quarter notes—but technically can be one whole note, two half notes, and so on (check out the illustration above for examples of the options!).

When counting aloud, you’ll most likely use numbers and the word “and.” The downbeat in each measure gets the number while the upbeats get the “and.” This is by far the most common, but it’s not a rule. You might meet some instructors who use vowels as well, count out “trip-a-let” or even make up triple-syllable words.

Reading sheet music comes in handy when you’re also teaching yourself how to count. For instance, if you have a 4/4 measure that includes one half note, one dotted quarter and an eighth note, you might say, “one, two, three-and four and.” If numbers and “and” don’t work for you, experiment. There are a slew of methods you can find and test out online. Unless your goal is to become an instructor, you’ll probably be the only person listening to your unique method anyway.

For instance, if you have a 4/4 measure that includes one half note, one dotted quarter and an eighth note, you might say, “one, two, three-and four and.” If numbers and “and” don’t work for you, experiment. There are a slew of methods you can find and test out online. Unless your goal is to become an instructor, you’ll probably be the only person listening to your unique method anyway.

Tools of the Trade

It might seem like some people naturally pick up how to count music while others struggle longer. That’s okay. A metronome can be a great tool to help you keep time. It’s your steadfast tempo guide, and there’s a reason musicians use it. You can also use it when listening to music as it helps you identify beats and values.

Pay close attention to your instructors when they count aloud or, better yet, ask them to help you identify the 4/4 measure before or after class with popular songs they play. Something few instructors make transparent is that they’re not always right. There are certainly times when someone counts wrongly aloud, but unless it’s a glaringly obvious mistake (it won’t be, it will be subtle), nobody is the wiser. Kind of like with dance, sometimes sheer confidence can help you seem like you know what you’re doing!

There are certainly times when someone counts wrongly aloud, but unless it’s a glaringly obvious mistake (it won’t be, it will be subtle), nobody is the wiser. Kind of like with dance, sometimes sheer confidence can help you seem like you know what you’re doing!

What About BPM?

Beats per minute are an easy way to see if a song might be suitable for a certain dance. In salsa, the BPM ranges from 120-250ish, with most popular songs hitting around 165. It’s just what it sounds like: How many beats are there in each minute? You may have seen some salsa pros and instructors say offhandedly, “This is a 210 bpm song, so—” and be amazed that they could know that instinctively. They’re likely close, but might not be right on point. The song could easily be anywhere from 180-225 and they’re close enough that nobody will argue with them.

The only real way to know a song’s BPM is to listen to the song and its beat. Close your eyes and, if you’re having trouble, try to pick out the drums (if applicable). Watch the second hands on a clock or a stopwatch. Count for 15 seconds, multiply by four, and you have your BPM. DJs are especially good at ballparking it, since their job is to seamlessly segue from one song to another, and they need to do this with beats.

Of course, if you don’t know whether a song is salsa-approved or not and aren’t confident in counting music, the simplest way to find out is to dance to it! You’ll discover quickly if you’ve found a new gem with a great salsa beat, or if it’s better suited to another kind of dance. The odds are high that if a song is great for salsa dancing, another salsero has already made the discovery—so an online search can save you a big headache!

How to learn to hear the rhythm in music | All articles | Planet of Talents

I am sure that all people love to dance. However, many believe that they do not have an ear for music or a sense of rhythm, not enough plasticity or coordination to dance, call themselves a “tree” and sit quietly in the corner at a disco. And yet, only a small proportion of them are right (and even then not in the part about the “tree”). Often the problem lies precisely in the ability to feel the music, in particular, the rhythm. But the problem is solved! For most people, the sense of rhythm is dormant. And only a very small percentage suffers from “rhythmic deafness”.

And yet, only a small proportion of them are right (and even then not in the part about the “tree”). Often the problem lies precisely in the ability to feel the music, in particular, the rhythm. But the problem is solved! For most people, the sense of rhythm is dormant. And only a very small percentage suffers from “rhythmic deafness”.

In my dance teaching practice, sometimes I come across people who can't hear the rhythm. For a group of fifteen people, there are on average 1-2 people. Agree, not such a big percentage for non-professionals. But this is where I ran into trouble. How to explain to a middle-aged person without a musical education what a strong and weak beat is, why sometimes we perform movements on “three”, and sometimes on “eight”, and how to count a piece in general? .. I think all teachers face this problem, It doesn't matter if they work with young children, youth or adults.

First you need to figure out if the student actually hears the music. First, you can clap a short, simple rhythm and ask him to repeat it. If the student reproduced it in full, then all is not lost! Secondly, you can turn on the music and step along with it, setting the pace. Then you need to pause, talk about something so that he is distracted, and turn on the same music again and ask him to walk to it in the same rhythm without you. There may be several options:

If the student reproduced it in full, then all is not lost! Secondly, you can turn on the music and step along with it, setting the pace. Then you need to pause, talk about something so that he is distracted, and turn on the same music again and ask him to walk to it in the same rhythm without you. There may be several options:

- the student walked to the beat, because he remembered the rhythm when you walked to the music together. And it's not a bad choice! Perhaps he needs to pay a little more attention than the others, stand next to him and show the movements individually, in the end his memory and great desire will bear fruit.

- the student walked in his rhythm, not hearing the music. Here the matter is more complicated. With such people, you need to deal with individually or gather them in one group and make a lesson in musicality for them. One or two sessions may be enough.

In such lessons, you need to explain what a strong beat is in music, how a melody is broken down into measures. Of course, you need to be patient, and most importantly, read music theory if you are not strong in it. In fact, it is not so scary, because the rhythmic pattern in the music school is studied in the lower grades. On the other hand, it is not necessary to overload the brain of students with this theory. Just think of a few metaphors. Rhythm can be compared with the beating of our heart, with clocks, with steps. Everything has its own rhythm - the moon and the sun, the surf, the seasons, a poem, the noise of a train, and even the sounds of a cricket. For such activities, you need simple, understandable music with a clear rhythm, for example, a march or, oddly enough, club music, with a characteristic “tuna-tuna”. The duration of notes can be compared with seconds, minutes, hours.

Of course, you need to be patient, and most importantly, read music theory if you are not strong in it. In fact, it is not so scary, because the rhythmic pattern in the music school is studied in the lower grades. On the other hand, it is not necessary to overload the brain of students with this theory. Just think of a few metaphors. Rhythm can be compared with the beating of our heart, with clocks, with steps. Everything has its own rhythm - the moon and the sun, the surf, the seasons, a poem, the noise of a train, and even the sounds of a cricket. For such activities, you need simple, understandable music with a clear rhythm, for example, a march or, oddly enough, club music, with a characteristic “tuna-tuna”. The duration of notes can be compared with seconds, minutes, hours.

By the way, using the example of a march, you can easily learn to hear a strong beat. I would suggest using this particular march http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VGfGxqHPF0s

In it, you can clearly hear how all the instruments of the orchestra play on a strong beat. I think that your students of any age will walk this melody with pleasure, and most importantly, to the beat!

I think that your students of any age will walk this melody with pleasure, and most importantly, to the beat!

A good helper in mastering the rhythm will be a metronome. Moreover, now everyone can install it on their smartphone or tablet and train at any time! By the way, the metronome is successfully used in the treatment of stuttering, and this says a lot.

In fact, I believe that anyone can learn to hear music and dance to it. All it takes is motivation. He works wonders even with the most seemingly hopeless students.

If the desire to learn to dance is great, follow a few simple but effective tips:

1. Listen to more music. Even more! Listen to it in any free minute. Learn almost by heart the pieces you need to dance to.

2. Divide music into instruments. The whole orchestra never plays the same tune. Double basses or bass guitars always set the rhythm, the main part is given to the violins or the voice, etc. Yes, it requires high concentration and attention, but it is really effective!

3. Learn to use a metronome.

Learn to use a metronome.

And remember, only working out the technique will not bring results. Love music, learn to hear it in the world around you, eventually become music, and then you will succeed!

© Arina Grakhantseva

Musicality: first steps. General questions, eights, squares.

Dear blog readers! Thank you very much for writing to us, contacting us with requests and questions, sharing your successes and difficulties. As promised, we will be happy to help, advise and tell you about everything that we ourselves know, and are also ready, at your request, to write our thoughts and views on the topic of interest to you. In particular, this post was the result of repeated questions that had different wording, but essentially meant the same thing: I can't get into the break, help, what should I do ?!

Attention : this post does not imply any special musical knowledge of either the readers or the authors, and does not claim to be accurate definitions and the ideal correctness of the terms. This is just an attempt to find a convenient way for some dancers to convey information about how to orient their dance in music and solve typical basic problems with musicality to other dancers - nothing more. This text has nothing to do with musical theory - only our practical experience, presented in a way that seems convenient and possible for us to understand! Rather, it is a small set of applied knowledge and the deliberately simple narrow theoretical justifications necessary for them, by no means reflecting the complete musical picture, but using which we were personally able to cope with the main problems that arise in the early stages of boogie-woogie dancing.

This is just an attempt to find a convenient way for some dancers to convey information about how to orient their dance in music and solve typical basic problems with musicality to other dancers - nothing more. This text has nothing to do with musical theory - only our practical experience, presented in a way that seems convenient and possible for us to understand! Rather, it is a small set of applied knowledge and the deliberately simple narrow theoretical justifications necessary for them, by no means reflecting the complete musical picture, but using which we were personally able to cope with the main problems that arise in the early stages of boogie-woogie dancing.

In general, the information presented in this post is not new and nothing here is any special discovery of our author, we simply present it in a form that turned out to be convenient for us to understand and apply. One way or another, all Russian and foreign teachers that we know, to one degree or another, touch on this issue in their Beginners-Intermediate classes. We learned a lot in the classes of Igor pivoo and Marina malina_a , a lot - on the training disks of Markus Koch and Barble Kaufer ( , despite the prescription of the year of issue, in some ways they have not lost their relevance and now ), the rest was brought from the camps or thought up by yourself (we recommend that you, in addition to studying the sources, also rely more on yourself and still try to figure it out on your own, come up with your own exercises and look for your "logic" in music and musicality, because the sense of rhythm and understanding of music, the way of systematization and interpretation is very individual for all people and, unfortunately, there is no universal approach). Thus, this post is just an attempt to systematize and combine theoretical information and practical exercises into a single complex, thanks to which you can comprehensively master the initial skills of musicality: to hear eights, squares and breaks, as well as highlight them in primitive ways .

We learned a lot in the classes of Igor pivoo and Marina malina_a , a lot - on the training disks of Markus Koch and Barble Kaufer ( , despite the prescription of the year of issue, in some ways they have not lost their relevance and now ), the rest was brought from the camps or thought up by yourself (we recommend that you, in addition to studying the sources, also rely more on yourself and still try to figure it out on your own, come up with your own exercises and look for your "logic" in music and musicality, because the sense of rhythm and understanding of music, the way of systematization and interpretation is very individual for all people and, unfortunately, there is no universal approach). Thus, this post is just an attempt to systematize and combine theoretical information and practical exercises into a single complex, thanks to which you can comprehensively master the initial skills of musicality: to hear eights, squares and breaks, as well as highlight them in primitive ways .

----------------------------------------

We would like to make a reservation right away that here we are not talking about musicality in general, in the sense of M u sical t and - it usually means some kind of magic , the miracle of the unity of a dancer and music, the harmony of expressing sounds with the body, and so on, which in principle cannot be taught and which either grows or does not grow in a dancer "by itself". We understand this very well and do not encroach on this side of the matter. But this does not mean that fasting, reasoning and teaching musicality are not possible in principle. Possible and necessary! For example, the Literary Institute trains certified writers, and the conservatory trains certified composers. Does this mean that the Tolstoys and Dostoevskys come out of the first, and the Tchaikovskys come out of the second? Of course not. Because in art there are always things that cannot be taught. But there are others who can, and moreover, need. It is not known whether inspiration will come to a graduate of a literary institute or a conservatory, but if it comes, they will have a chance to express it, because they have learned the means, methods and techniques of expression, they have the technique.

But there are others who can, and moreover, need. It is not known whether inspiration will come to a graduate of a literary institute or a conservatory, but if it comes, they will have a chance to express it, because they have learned the means, methods and techniques of expression, they have the technique.

Since the dancer must have his own technique: the main move, lead-follow, basic musicality.

----------------------------------------

From the conversation:

- Soooo, don't you know all this crap

about swing-blues square and eights?

- Well, we were once mentioned at the beginning, but actually

they say that music should be felt...

How can I feel if I don't know what.

There is a myth among dancers that there are two opposite approaches to music - counting and "feeling". At the same time, from high-level dancers who have long overcome such problems, one can often hear statements in the style of "counting is wrong, mechanical, nerdy, but feeling is right" . .. Often, these are rather dishonest statements in relation to a beginner, for upon closer contact with the authors of such speeches, it often turns out that many of them simply forget what they also considered at an early stage. Or they do not want to mention it as some kind of dark spot in the biography. Or - even worse - because of laziness or the belief that "counting is shameful", until the very late period they had / remain problems with the accuracy of hitting breaks, the purity of inserting ligaments and the professionalism in the performance of a competitive dance, which could easily be I would solve it by applying counting exercises and accustoming my brain and body to be accurate in music, and not to make a figure, in the brilliant expression of Katrunov, "in the near-break area." (It is a pity that often an inexperienced spectator, especially one brought up in Russian boogie culture and rarely and inattentively studying European boogie, thanks to the great practice of any advance-level dancer, including Russian, to adapt their vocal cords to music "somehow" with all sorts of social -ways, it may not be obvious, and even worse, there are times when it is, unfortunately, not obvious to the judges either).

.. Often, these are rather dishonest statements in relation to a beginner, for upon closer contact with the authors of such speeches, it often turns out that many of them simply forget what they also considered at an early stage. Or they do not want to mention it as some kind of dark spot in the biography. Or - even worse - because of laziness or the belief that "counting is shameful", until the very late period they had / remain problems with the accuracy of hitting breaks, the purity of inserting ligaments and the professionalism in the performance of a competitive dance, which could easily be I would solve it by applying counting exercises and accustoming my brain and body to be accurate in music, and not to make a figure, in the brilliant expression of Katrunov, "in the near-break area." (It is a pity that often an inexperienced spectator, especially one brought up in Russian boogie culture and rarely and inattentively studying European boogie, thanks to the great practice of any advance-level dancer, including Russian, to adapt their vocal cords to music "somehow" with all sorts of social -ways, it may not be obvious, and even worse, there are times when it is, unfortunately, not obvious to the judges either).

We are convinced that these two methods do not contradict each other in any way, but rather complement each other, flow from one another, are closely intertwined, both are necessary for a professional boogie-woogie dancer and we dream of debunking the myth of the opposite, because nothing but complexes "I do not feel "and inhibited development in the pursuit of "flair", he does not bring to a novice dancer. And yes, we want to eventually solve the problem that, due to the lack of a clear program for teaching basic musicality (minimally hearing breaks and being able to corny reflect them), as well as active reasoning that music, they say, "should be felt", in a novice dancer complex begins to form: and if I don't "feel", then maybe I'm "not given"? Calm down, given to you, given! Such a simple thing as hitting and hitting breaks is given to everyone, you just need to make a little effort and patience, as well as try to listen to yourself and develop for yourself your own individual approach and your own individual exercises that will come from your own mindset, abilities, talents, inclinations and psychology.

----------------------------------------

Eights and squares.

Various structural parts are distinguished in music. Among musicians, the minimum unit of articulation of music is a measure, for a boogie-woogie dancer it is a figure eight, which represents two measures (eight beats / counts). The meaning of the division into eights lies rather in the field of harmony, but if we speak more simply, the eight is one line of the verse.

The first thing to learn is to count eights, which in fact means to hear its beginning and, accordingly, its end.

To do this, you will have to learn how to count beats, as well as distinguish between a strong and a weak beat.

When a person is sitting right next to you and music is playing, it is very easy to explain, but it’s not very easy to put it in the text, so if you don’t understand what it’s all about, it’s better to approach your teacher or just a friend -Advancer, turn on the music and ask you to count to eight!

So, in the music to which boogie-woogie is danced, one can distinguish between a strong and a weak beat. This means that the beats (what creates the pace of the track, in our music can be associated with the pianist's left hand part or double bass) are not the same, and some are emphasized more strongly, while others are weaker. To get a feel for what it's all about, put on a song that isn't too fast and give it a try (SEE AUDIO APPENDIX at the end)

This means that the beats (what creates the pace of the track, in our music can be associated with the pianist's left hand part or double bass) are not the same, and some are emphasized more strongly, while others are weaker. To get a feel for what it's all about, put on a song that isn't too fast and give it a try (SEE AUDIO APPENDIX at the end)

- count and clap every bit

- count every bit and clap for every odd count (1,3,5,7)

- count every bit and clap for every even count (2,4,6,8)

Try hear and feel how it is more comfortable and organic for you to clap, look for the difference between every first and every second beat by ear. Try this experiment with different songs and make sure you can hear the beats and clap meaningfully on odd and even beats.

The beginning of the square - the beginning of the first eight after the introduction - is the beginning of a new musical phrase. Here are some clues how it started to hear

- the verse begins. That is, after the introduction, for example, the vocalist begins to sing. Usually he does this exactly from the beginning of the square (although often "from the beat" - from count 7, for example, the introduction, but in this case, the stressed syllable usually falls on time, so the beginning is still highlighted, well, or belatedly , for example on the count of 2 of the first eight of the square, but this is not so significant, in general terms, the vocal intro will help you feel the beginning of the square.Listen to different songs and look for this beginning).

Usually he does this exactly from the beginning of the square (although often "from the beat" - from count 7, for example, the introduction, but in this case, the stressed syllable usually falls on time, so the beginning is still highlighted, well, or belatedly , for example on the count of 2 of the first eight of the square, but this is not so significant, in general terms, the vocal intro will help you feel the beginning of the square.Listen to different songs and look for this beginning).

- the line of the song is about an eight. Try to imagine the lyrics of the song written in verse. Where, actually, the rhyming ends of the lines are the boundaries of the eights

, the loss begins. The verse ends most often with the end of the square, which means that you can hear the beginning of a new one because the singing has ended and the musicians have begun to fry the solo

- a new instrument enters. Most often, new instruments are added to the music from the beginning of a new square. Also, the nature of their playing can simply change, the dynamics of the rhythm section intensify and weaken, etc. - all changes of this type in music usually occur on the borders of squares

Also, the nature of their playing can simply change, the dynamics of the rhythm section intensify and weaken, etc. - all changes of this type in music usually occur on the borders of squares

Listen carefully to the audio applications and try these experiments with different songs. Everything will work out! The main thing you need now is to try to hear when a new musical phrase (square) begins and start counting up to 8. One poetic line will fit into each eight. This will mean that you have mastered the shares and eights. Then everything is much easier!

----------------------------------------

Square.

Next, when you have learned to hear the beginning of the square, you need to learn to hear its end. Most (not all!) of the music to which boogie-woogie is danced can be divided into two categories according to the squares of which it consists.

1. Swing square.

Swing square.

Typical for songs that are rooted in jazz, swing, etc. Consists of 4 eights . In simple terms, this means that the break occurs at the end of every fourth eight of the song. If you start counting from the beginning of the square, then the first three eights will be dynamically similar to each other, and in the fourth there will be something special - stops, interruptions, pauses, accented beats or, in extreme cases, just a harmonic completion of the phrase - "turn around", break .

(Musicians usually understand the structure of 16 AABA eights as a swing square, this term is rarely used among dancers, it is worth bearing in mind).

2. Blues square.

Typical for songs that came from the blues, rock and roll. Consists of 6 eights. This means that the break occurs at the end of every sixth eight of the song. That is, if you start counting from the beginning of the square, then the first four or five eights will be dynamically the same, and the fifth and sixth (sometimes only the sixth) will be "breaks", that is, something special will happen in them, different from the previous even four.

Often, to hear this type of square, you do not need to listen to it until the break, because in this type of songs the grouping of eights in twos is most clearly audible. That is, every two eights sound like a micro-phrase, often it is a question-answer or just a parallel repetition. In a swing square, this practically does not happen, there is a uniform development from the first to the fourth eight. You'll get a feel for this over time, just try counting first and see if you can now "calculate" breaks using a count of eights.

3. Since this post is for beginners, without going into details, we will simply mention that there are all sorts of other different cases and exceptions, for example, alternating six- and four-eight squares (most often - a couplet of 4 eights, and losing - 6 each), an eight-eight square, a three-eight square, as well as complete nonsense, such as several additional accounts or pauses. The main thing is to learn how to count the basic structures, as a result there will be no problems to understand all the others.

Listen to different songs, as many different songs as you can, and try to count eights and listen at what moment changes occur, based on this, draw conclusions with what type of square you are dealing with. Learn well confidently and accurately by listening to music and counting, to understand where the square begins and where it ends. Count a lot and often until you learn. Over time, this will turn into automatism and the very "flair" that you often heard about will be developed.

----------------------------------------

Lyrical digression. Tell me, can you say how much, for example, 10 percent of 100 will be, without making mathematical calculations? You can. And you can also say how much 15 and 20 will be. Many can do the same with more complex numbers. Does this mean that we somehow particularly "feel" interest? Nothing like this. It’s just that once upon a time we first studied in detail that “you must first divide by a hundred, and then multiply by the required number of percent”, and before that we also had to learn the multiplication table, and after that for a very long time and a lot of solving all sorts of things orally and in writing examples and tasks, then I encountered this more than once in my life and used it regularly - and this turned into automatism, now actions are performed subconsciously, and you do not fix them, but only get a ready answer.

In the same way, any process can turn into automatism, including the notorious "count of eights". For example, we dealt with hitting breaks quite quickly, much earlier than with many other basic technical problems, because we used this method: we listened a lot and counted without dancing at all, then counted a lot during the dance, invented and did different exercises on counting, thanks to which at one fine moment there was no need to consciously carry out the counting process, it happens somewhere by itself, and now we can boast that in the sense of hitting the breaks, we "feel" the music, since we do not formally work on counting. But the way to this basic "flair" lay through the usual account, exercises, patience and work.

----------------------------------------

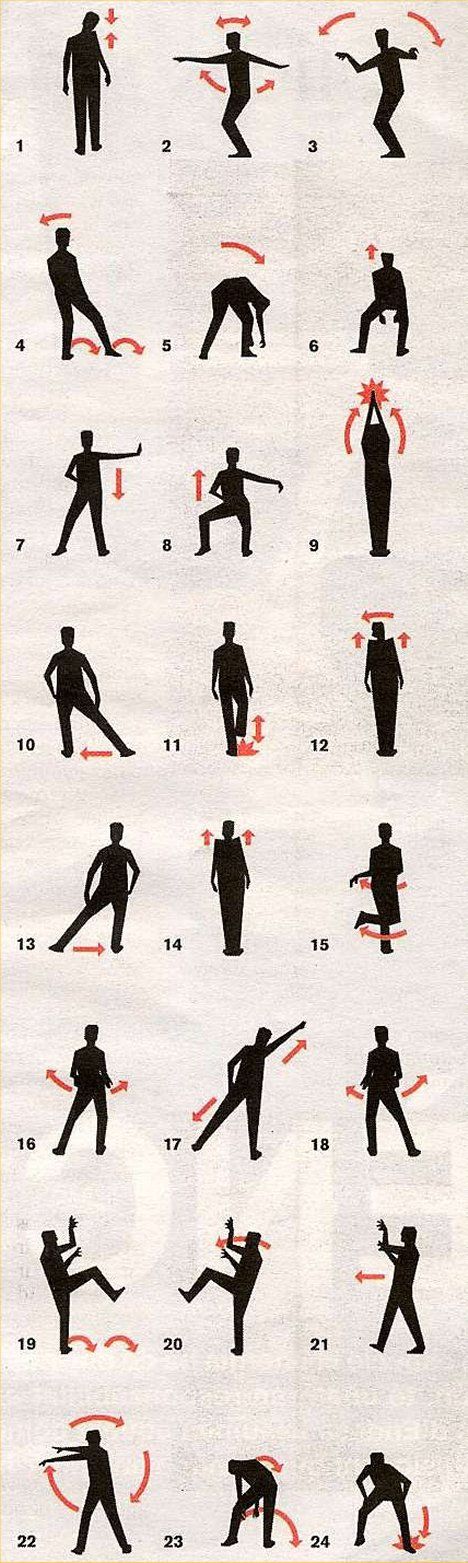

As a result - a few simple exercises that must be performed to develop counting skills. Of course, they are recommended more to the partner, but it is more interesting and useful to do them together, because a partner who is different from a vegetable and who knows how to understand the song is good.![]()

1. Listen to music and "count" it outside of the dance. Often and a lot! Until you bring it to automatism.

2. Watch a lot of videos, preferably European competitions, not just for entertainment and interest, but for specific purposes. For example, look for figure eights, squares, breaks, etc. in the dance. and see how it affects the dance. Look for accents, see how, in what ways musical accents turn into dance ones. Think and consider what happens to what accounts? what eights? what part of the square? Why is this on this account and something else on that one? What are the patterns? Etc. Ask yourself as many questions as possible about the relationship between the dance of the best dancers and the music, look for as much as possible of the typical in the dances of world stars and in the music we dance to. Systematize, try to understand the internal logic of modern boogie-woogie, accustom your brain to it.

3. Get into the habit as soon as you hear the song to determine the type of square as quickly as possible. Try to do it as early as possible, try by ear to look for something in common between all the "swing" and "blues"-square songs, as well as the signs by which they are similar and different, in order to determine the type before how the first break will take you by surprise. Do this first outside of the dance, just while listening to music, and as soon as you get confident - in the dance.

Try to do it as early as possible, try by ear to look for something in common between all the "swing" and "blues"-square songs, as well as the signs by which they are similar and different, in order to determine the type before how the first break will take you by surprise. Do this first outside of the dance, just while listening to music, and as soon as you get confident - in the dance.

For example, the exercise is as follows: the partner's task is to determine the type of song as quickly as possible. You start dancing and as soon as the partner has decided, he speaks to the partner. After that, you can move on to the next song. Thus, you will get into the habit of not starting your competitive dance mechanically or half-delirious, but immediately from the first second of the performance turn on your head, think, work. Over time, this will become automatic, but first you have to work somehow.

4. In order to learn how to disconnect the head from the legs and allow it to listen to music calmly while the legs are doing basic, the following exercise is useful. The music turns on, you start doing BASIC together and counting eights. You can at first out loud, but when it starts to turn out - be sure to yourself. Over time, you can try not to count at all, but rely on "intuition".

The music turns on, you start doing BASIC together and counting eights. You can at first out loud, but when it starts to turn out - be sure to yourself. Over time, you can try not to count at all, but rely on "intuition".

Cotton can be used afterwards. To begin with, you and your partner agree to clap, for example, at the expense of 8, you can do it together or take turns. You dance basic and don't stop clapping on the agreed score. If it doesn’t work on BASIC, try first just standing, then on the steps, and only then on BASIC. When you feel comfortable clapping every eighth count, try clapping every fourth count, then every second count (without stopping the BASIC!). Start at a slow pace and build up gradually.

Later, when this exercise becomes easy for you, try clapping on some uncomfortable count, for example, on 3 or 5. Well, as an aerobatics - you can clap a rhythmic pattern every eight, for example, on 1,4 and 7. Or one can clap for every 3rd count, and the other for every 7th, and so on.

5. A good BASIC workout, which also develops the feeling of squares, is that you and your partner stand opposite each other and dance BASIC in turn in a square. The goal is to enter at the time of the first eight and finish at 8 of the last (fourth - if the song is with a swing type of square, sixth - if with blues) to each in turn. At first we recommend counting, over time it will start to turn out intuitively.

6. As you know, in the classical version, jazz movements are performed in such a way that they begin on the last count of eight - eight (if you do not understand what it is about, analyze, for example, shim-sham). Jazz dancing also helps the musicianship a lot. For example, you can take turns dancing any simple jazz movements known to you (boogie back, boogie forward, shoty joe, apple jack, suzy cue, etc.) in one square, each square is different. Or in turn - one starts, the other picks up, then vice versa. The goal is to start on the eighth count and keep doing it without breaking until the end of the square.

7. Studying jazz tracks and show numbers is very instrumental in the growth of musicality: you train your ear and body to work according to the pattern, which is a track or a number composed by other people who are at a different stage of musicality. Learn that boring shim sham already! Take a look at the video and learn someone else's show number! Try to adopt someone else's musicality, listen to it, understand it, understand how and what works, what and why is musical and what is not.

8. Try dancing and stopping for breaks. Stop for a break, that means no oh damn, it seems to have already begun (although at first it will do, of course), but confidently calmly think about what is happening in the music now, what is the structure of the track and what moment is right now, and when will the break be, and calmly prepared confidently stop on the first count of the last eight (or in the case of a blues square, you can count on the first count of the fifth (penultimate) eight) and calmly stand until the end of the square, entering a new one. When the stops get more confident, you can think of some movement for the break, such as twists. When the movements also began to turn out confidently, you can move on to learning how to make some figures in breaks (for example, the easiest task is to make exactly the last eight of the square a swingout, starting at one and ending at eight, without knocking off your feet anywhere, without losing the BASIC and evenly laying all the figures in a square).

When the stops get more confident, you can think of some movement for the break, such as twists. When the movements also began to turn out confidently, you can move on to learning how to make some figures in breaks (for example, the easiest task is to make exactly the last eight of the square a swingout, starting at one and ending at eight, without knocking off your feet anywhere, without losing the BASIC and evenly laying all the figures in a square).

The purpose of all these exercises - is to develop a reflex that will not give you the opportunity to miss the break even in the most difficult song, because over time the count will fade into the background, the ears and brain will get used to and begin to hear those very magical harmonic changes , which occur in any square and which predict a break. Thus, you will learn how to effortlessly insert a one-eight figure / link exactly into the fourth eight of the swing square and into the sixth of the blues, and two-eight into the third of the swing and fifth of the blues, and also learn how to insert a solo track at the beginning of the square. Actually, this is the primitive basic musicality that you need to master first of all, long before any discussion about feeling, hearing and given or not given .

Actually, this is the primitive basic musicality that you need to master first of all, long before any discussion about feeling, hearing and given or not given .

A well-composed combination with correct accents + the ability to start on time of the required eight at the initial stage is the key to a simple but good competitive dance. This is the basis on which you can already impose "sensitive" musicality, trifles, accents, inside which you can play with the character and mood of movements, create an individual vision of music and dance your own dance. But without this foundation you can't dance a decent dance!

----------------------------------------

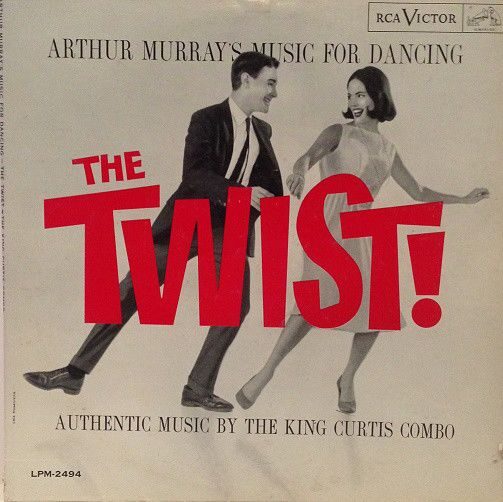

For clarity, we attach two audio files. The first file is the song Bill Haley - See You Later Alligator, the square of which consists of 6 eights (a typical blues-rock and roll structure), the other track is Chubby Checker - Let´s twist again, a 4-eight song (standard swing structure).

Each track starts with a count of eights and squares. In writing, it looks like this: (1) 2345678 / (2) 2345678 / (3) 2345678, etc., where the first score (in brackets) means the number of the eight, and the remaining numbers - the count of the shares in the eight. After that, in each file there are claps on the first beat and claps on the second beat. Note that second beat claps sound more organic to this music. On the last eight squares, you will hear the cry "BREAK" in the background - this is the very place that is important to be able to find and highlight in our dance.

And for the last time: make it a rule to count eights and figure out the structure of the song when you listen to music, and very soon you will really "feel" the breaks and never get lost inside the song!

lets twist_lesson - Hitruk

lets twist_lesson - Hitruk

-------------------------------- --------

PS.