How to talk about dance

Let’s Talk about Dance – Bram Vreeswijk

‘Let’s talk about dance’ is a conversation based research on dance conducted by Bram Vreeswijk. It explores physical experiences of dancing and watching dance in conversations with people; audiences, choreographers, and dancers (professionals and amateurs).

Point of departure for the work is the fact that during a dance-performance every-body involved has physical experiences; dancers on stage as well as those that watch and sense dancing. These experiences are relevant in the process of creating and receiving dance.

Another important principle for the work is that dance – since dance deals with physical experiences – is connected to all other areas of life. In dancing as well as watching dance, the whole human being is involved, including histories that are stored in peoples bodies and minds.

Rob talking about ‘Rocco’, a choreography by Emio Greco and Pieter C. Scholten.

Articulating and sharing physical experiences

Talking about physical experiences is not easy. Physical experiences are partly unconscious and difficult to put in words. It seems that our language is much more suited for talking about goals, plans and objects outside our bodies, than about our own experiences, sensations and feelings. Therefore in this research special attention is paid to the conditions of meetings and conversations. How can we create the conditions for articulating and sharing physical experiences? How to find the relevant words? Words that might be vague, poetic or metaphoric… How to build conditions of trust necessary to share information that is often intimate? How to create conversations in which the different ‘truths’ of different people are respected? How to deal with the physicality of talking (gestures, pace, posture etc.)?

Some of these meetings will be in a theatres, open to a public. Other meetings will be only for invited people, in dance-studios, living-rooms etc.

Other meetings will be only for invited people, in dance-studios, living-rooms etc.

Events, research and presentation

The aim of this project is to do the research together. The traditional separation between doing research (by a researcher) and presenting the results of a research (to audiences / readers) is avoided as much as possible. Work will be presented at meetings which are research-events in themselves. Audiences are encouraged to be active and contribute to the research which is happening at the spot.

The conversations documented at this website are meant as points of reference for future conversations.

I hope to meet you at a future event.

.

(In)visibility in Dance – Maria Mavridou and students of ArtEZ

The Delicacy of the Loving Act – Mor Shani

Motivations for Movement – Emio Greco and Pieter C. Scholten

essay: Trauma and Trauma Healing. Movement, Dance and Performance

.

.

.

.

.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Responding to Dance - KET Education

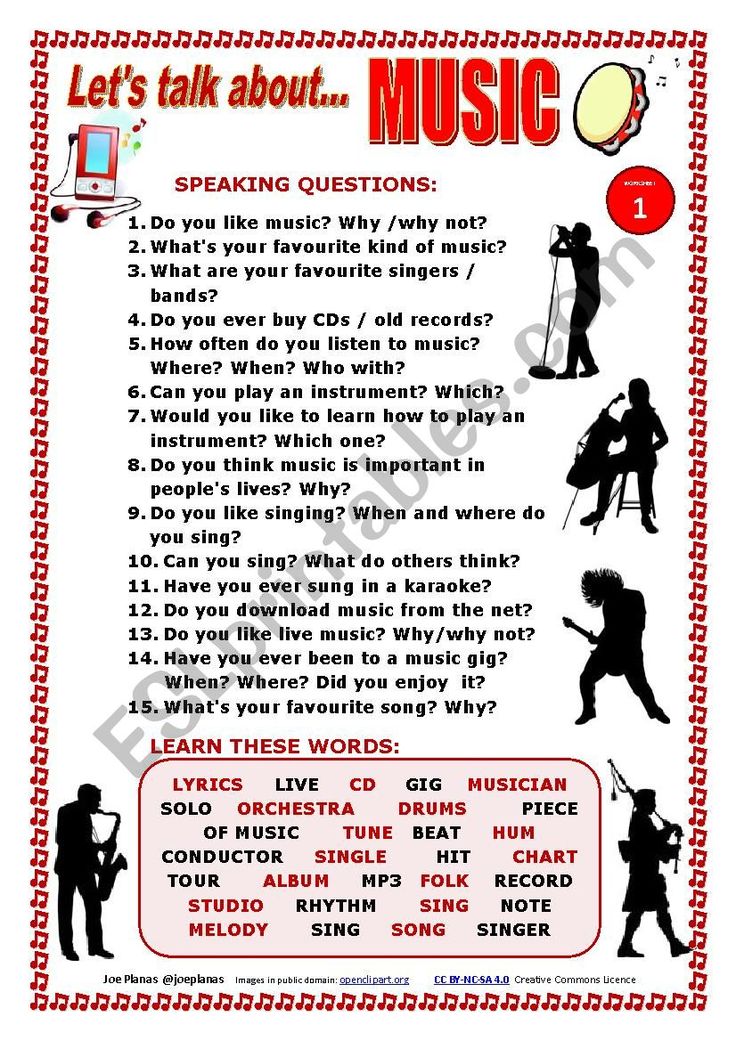

Attending with a Purpose: Questions To Ask, Concepts To Know

It is always a good idea to have a purpose in mind when we are asked to respond to a dance performance, regardless of whether it is a formal concert, a performance of our peers, or a showing of a film or video. Below are some good questions to consider before, during, and after attending a dance performance. They are based on standards, key concepts, and key vocabulary that all Kentucky students are expected to understand and/or achieve (indicated below in italics).

Being aware of your First Impressions allows you to think about your immediate response to the dance, both as you are experiencing it and immediately afterward. Since the Body is the instrument of expression in dance, it’s a good idea to understand how dancers prepare for a performance and to pay attention to the way they use their bodies in a performance. The material that choreographers use to communicate ideas, thoughts, and feelings is Movement (locomotor and non-locomotor). Finally, it is helpful to pay close attention to the Elements of Dance (Time, Space, Energy). If the dance is created for an artistic purpose, the choreographer uses the elements of dance, movement ideas, and the physical and expressive abilities of the dancers to create a dance that entertains, proves interesting, or moves (emotionally) the audience members in some way. Most dances, even social dances, have some Element of Production, such as costuming, setting, props, or lighting. Finally, dance occurs in a Social, Cultural, and Historical Context. It may be necessary to do some basic research regarding these contextual elements in order to fully understand and enjoy the performance.

The material that choreographers use to communicate ideas, thoughts, and feelings is Movement (locomotor and non-locomotor). Finally, it is helpful to pay close attention to the Elements of Dance (Time, Space, Energy). If the dance is created for an artistic purpose, the choreographer uses the elements of dance, movement ideas, and the physical and expressive abilities of the dancers to create a dance that entertains, proves interesting, or moves (emotionally) the audience members in some way. Most dances, even social dances, have some Element of Production, such as costuming, setting, props, or lighting. Finally, dance occurs in a Social, Cultural, and Historical Context. It may be necessary to do some basic research regarding these contextual elements in order to fully understand and enjoy the performance.

Before You Go

Before you see the dance, review the questions below. Afterward, consider the same questions. Can you answer them? What more will you need to know in order to answer them well?

- Did the dance hold your interest? Can you say why or why not?

- Did you find it entertaining? If so, what parts did you particularly enjoy?

- Did the dance teach a lesson or have a moral?

- How did the dancers’ movements allow you to understand what the choreographer was trying to “say”?

- Did you have an emotional reaction to the dance? How did it make you feel?

- If the purpose of the dance was to tell a story (narrative), were you able to follow and understand it?

It will also be helpful for you to know some background information about the dance you are going to see before you actually see it. What research or reading might you need to do?

What research or reading might you need to do?

- Does the dance have a specific purpose?

- Is the purpose artistic? If so, what is the artistic form or genre?

- Can you describe the characteristics of ballet, modern dance, jazz dance, or tap dance?

- How could you find information about these artistic forms of dance before you see the dance?

- Did someone choreograph this dance, or has this dance been passed down by tradition?

- Is this dance associated with a particular culture or ethnic group within a society?

- How can you find out more about the stylistic elements associated with the choreographer, culture, or ethnic group?

- Rather than artistic, is the purpose of the dance recreational or ceremonial?

- What does the purpose of the dance say about the culture or society it represents?

↑ Top

Viewing the Performance

In order to understand and enjoy the dance more fully, you may need to understand some key vocabulary and concepts before you see it. As you review the questions below, what further questions occur to you? Look for words and concepts in the Kentucky Dance Core Content that you need to understand better. Make sure you have at least reviewed a definition of these concepts before you see the dance.

As you review the questions below, what further questions occur to you? Look for words and concepts in the Kentucky Dance Core Content that you need to understand better. Make sure you have at least reviewed a definition of these concepts before you see the dance.

First Impressions:

- How did the performance begin?

- What were some of your first impressions at the beginning of the dance?

- Did the dance have musical accompaniment? How did you like the music?

- Why do you think the choreographer chose this music?

- What made the strongest impression on you as the dance progressed?

- Can you describe this dance? Did it have a distinct beginning, middle, and end?

- Did you have a favorite dancer?

- What elements of the production (music, costumes, lighting, scenery) made the biggest impression on you?

The Dancers’ Bodies:

- How were the dancers’ bodies used in this dance?

- What different body parts did they use?

- Did they seem to move skillfully?

- Can you explain the roles that the skills of body alignment and dance technique play in a dance performance?

- Do you know when these skills are important and when they might not be?

- How can you use what you learned from the dance you have seen to understand these concepts more fully?

- What is it about the dancers’ training that allows them to use their bodies expressively?

- How did the musical accompaniment affect the way the dancers moved?

- What were the physical relationships between the dancers to each other during the dance? Did they ever move in unison?

- How are these movements different from everyday movements or sports movements?

- How do dancers train their bodies? What do they have to do to get ready for a performance?

- Can you compare the ways dancers warm up and prepare their bodies for dancing with the way that athletes warm up and prepare for competitions?

Movement (Locomotor and Non-Locomotor):

- Using the elements of dance, can you describe some of the movements in the dance, especially the ones that made a big impression on you?

- What did the dancers’ movements remind you of?

- How did the dancers combine locomotor and non-locomotor movements?

- What do you remember the most about the movements of the dancers?

- Did the movement seem to “go with” the music?

- How are the movements that are part of the dance similar to or different from everyday movements and sports movements?

Space:

- What shapes did the bodies of the dancers make?

- What floor patterns in space did the dancers make as they traveled through space?

- Did the dancers change levels at any time during the dance?

- Were there many “lifts”?

- In what sections of the dance was space emphasized the most?

- Were the shapes they made symmetrical or asymmetrical?

- How did the choreographer use aspects of the element of space to make the dance more interesting or to communicate the theme of the dance?

- Did the music seem to have any impact on the way the choreographer chose to use space?

Time:

- What aspects of the element of time were used?

- Was the dancing fast or slow? Were there changes in the tempo?

- What did you notice about the dancers’ rhythms?

- Were any of the movements accented?

- Was the tempo of the movement always the same as the tempo of the music?

- How did the choreographer use aspects of time to communicate his or her ideas or to make the dance more interesting?

Energy:

- How would you describe the energy of the dancers and the dance?

- Can you name all the different movement qualities (the way force and energy were used) you saw in the dance?

- Did the dance have a mood?

- How did the energy in the movement affect the mood of the dance?

- How was the energy of the movement similar to or different from the dynamics of the music?

- How did the dance make you feel?

Production Considerations:

- How effectively did the dance incorporate sets, lights, costumes, and sound, if at all?

- How did these elements complement the movement and the choreography?

- Can you describe at least three different ways that lighting was used to enhance the choreography?

- Were the costumes elaborate or simple?

- Why do you think the choreographer and costume designer made this choice?

- What skills do lighting designers and costume designers need to have?

- Did the choreography “fit” the dancing space (the stage)?

Historical, Social, and Cultural Context:

- How does dance in general contribute to society, both as an activity and as an art form?

- How does this dance reflect the personal history of the choreographer or the culture of a particular country or culture?

- How does the dance portray thematic ideas or societal issues?

- Does the musical accompaniment seem to reflect a particular culture, style, or historical period?

- Does it communicate or “comment on” any social or political beliefs?

- Put yourself in the role of the dancers for this performance.

How is their participation and preparation for the performance similar to or different from your own and other audience members’?

How is their participation and preparation for the performance similar to or different from your own and other audience members’? - Why did the choreographer create the dance?

Analysis and Interpretation:

- Did the dance tell a story?

- Was the dance expressing feelings or an idea?

- What was the theme or the subject matter of the dance? How effectively was it carried through in the choreography?

- What choreographic form did the dance take?

- What was the meaning of the dance to you?

- If you observed more than one dance on the same “program,” how were the dances alike and different?

- Did the dance work for you (make sense to you) as a whole?

- What relevance does this dance have for you or others who might see it?

↑ Top

Critique

Now you are ready to make a judgment and communicate to an audience about the dance production you have seen. In responding to the questions above, you needed to describe movement and the elements of dance, analyze how they fit together, and explain or justify your response. Review your responses to the questions above and use your understanding of the concepts contained in these questions to help you determine your personal reaction to the performance. Now you are ready to write a critique!

Review your responses to the questions above and use your understanding of the concepts contained in these questions to help you determine your personal reaction to the performance. Now you are ready to write a critique!

Audience:

- Who are the intended readers of your critique?

- How will you interest them in what you have to say?

Purpose:

- Keep in mind your goal or purpose in writing for your audience.

- Are you trying to persuade your readers to see the performance (or not) or merely to persuade them to agree with your opinion after they have seen it?

Focus:

- What are the most important things to comment on when writing about your analysis of the performance? Remember to support your opinion with specific facts or examples from the performance.

Content:

- What was your overall impression of the performance?

- Was it an enjoyable or otherwise worthwhile experience? Why or why not?

- What entertained or impressed you the most?

- Were there weaknesses in the dancers’ performance, the choreography, or the production elements that you need to point out?

- On the other hand, what were the strongest aspects of the production?

- Would you recommend that others see it? Why or why not?

↑ Top

How to think and talk about dance

For many people, dance is not just a non-intellectual activity, it is an anti-intellectual activity. Such an opinion seems to be supported by experience and stereotypes, but contradicts modern neuroscience. Look, for example, at Chernigovskaya's lecture, which says a lot at the beginning about Jiri Kilian, a classic of modern ballet, and about how complex brain work is needed to create and perform his choreography.

Such an opinion seems to be supported by experience and stereotypes, but contradicts modern neuroscience. Look, for example, at Chernigovskaya's lecture, which says a lot at the beginning about Jiri Kilian, a classic of modern ballet, and about how complex brain work is needed to create and perform his choreography.

The common opinion “I come to the dance to turn off my head” expresses the inner truth of a person, but contradicts his other truths, external and internal. In the integral approach, we are interested in a dance that can embody and express the fullness of the human being. How can we dance so that the mind is part of the dance and not a hindrance to it?

The impetus for writing this text was other texts about dance and, first of all, a wonderful post by Anatoly Levenchuk about the system engineering approach to dance thinking in its opposition to the usual one. Not only the text itself is interesting, but also the discussion of it. The very first line “… we dance not with the body, but with the brain” so contrasts the author's position with the vague spiritual holism of most dance discourses that it causes rejection of varying degrees of passivity.

Not only the text itself is interesting, but also the discussion of it. The very first line “… we dance not with the body, but with the brain” so contrasts the author's position with the vague spiritual holism of most dance discourses that it causes rejection of varying degrees of passivity.

If we translate this opposition into emphasizing the difference between different cognitive processes, between different ways of understanding, experiencing and managing the process of movement, then we can take some good ideas from this text.

First, in what context are we discussing the dance, what interests and positions of power do the participants in the dialogue have? Dancers, spectators, choreographers, critics - everyone will have a different interest and different positions.

Second, from what perspectives do we proceed when speaking about dance. Educational perspective - how best to learn, master and appropriate this or that language of movement? Or a creative, poetic viewpoint — what is experienced in motion as something beautiful and generated precisely by man?

And it turns out that we need some (or better, qualitative) cognitive abilities for the development of dance, and somatic and operational instructions more often and more accurately lead to the required quality and pattern of movement. That there are different levels of movement organization (hello to Nikolai Bernstein!), and if you start without working out and mastering the earlier, basic levels of movement organization, then mastering complex patterns begins to suffer and suffer. These are just a few ideas I pulled out of a large and dense text.

That there are different levels of movement organization (hello to Nikolai Bernstein!), and if you start without working out and mastering the earlier, basic levels of movement organization, then mastering complex patterns begins to suffer and suffer. These are just a few ideas I pulled out of a large and dense text.

Another indicator of the significance of this text for me will be an audio track based on Levenchuk’s text, recorded by my friend and colleague Valery Veryaskin, known for his project “Buddha in the City”. If the text gives rise to a desire to think and create, it is a good text. Enjoy and dance!

To dance, you need to love it. He will give you nothing in return - no manuscripts, no paintings to display in museums or at home, no poems to publish and sell.

Nothing, just one fleeting moment when you feel you are alive.

Merce Cunningham

Prev. Hormones of happiness and "bad" emotions Next More dance

Dance as a philosophy • Episode transcript • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

CourseWhat is modern danceAudio lecturesMaterialsContents of the second lecture from Irina Sirotkina's course "What is modern dance"

It is believed that the goal of education is to get rid of imposed opinions, patterns, stereotypes. There are also many stereotypes about dance. Many people think, for example, that dancing is not an intellectual pursuit: intellectuals are not interested in dancing, and dancers do not read books. And it is also believed that it is better to dance than to talk or read about dance. Let's say right away: it's better - both. Moreover, one thing - dancing - is hardly possible without the other - without thinking, talking, reading about dance.

Stereotypes, alas, are peculiar not only to poorly educated people, but sometimes even to philosophers. Philosophy in the West and in our country has long ignored the body. The body has been the Cinderella of classical philosophy ever since, in the 17th century, René Descartes separated the thinking substance, res cogitans (or, literally, "the thing that knows"), from the material substance, res extensa, endowed only with the property of extension. Thought was thus incorporeal. But philosophers were only interested in it - thought. Already in the 19th century, Hegel declared that the subject of thought is an incorporeal spirit. This was probably due to the fact that philosophers took very little care of their own bodies and sat a lot.

Nevertheless, let's give Hegel his due: he considered sculpture to be the highest and most beautiful of all arts. And the favorite subject of sculptors is the human body. Hegel defined beauty as the conformity of form to an idea, as an expression of the eternal idea of beauty. These were the ancient sculptures of heroes, gods, sages-philosophers, whom everyone then admired. But dance is related to sculpture! Dance, like sculpture, is often classified as a plastic art. And at the beginning of the 20th century, a new dance appeared, which was called plastic. It is quite possible to imagine that dance is a sculpture in motion, plasticity is in dynamics.

These were the ancient sculptures of heroes, gods, sages-philosophers, whom everyone then admired. But dance is related to sculpture! Dance, like sculpture, is often classified as a plastic art. And at the beginning of the 20th century, a new dance appeared, which was called plastic. It is quite possible to imagine that dance is a sculpture in motion, plasticity is in dynamics.

Friedrich Nietzsche was the first to notice that in dance the body also becomes a work of art, which means that it also expresses an idea, a thought. Nietzsche literally turned classical philosophy upside down. And he did it not least with the help of dance. Like Isadora Duncan, Nietzsche loved antiquity and believed that in ancient Greece the highest stage of human development was reached - a golden age, which people then lost. In The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, Nietzsche composes a real ode to dance - an ancient and eternally young dance: “... man ... is ready to dance into the airy heights. Witchcraft speaks with his body movements. …He feels like a god.” And in the philosophical poem Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche writes: "I would only believe in a God who could dance." His Zarathustra dances with nymphs in green meadows. For Nietzsche, dance becomes an attribute of the highest, divine art and thought. Therefore, dance for Nietzsche is a metaphor for thought. The divine lightness of the dance is opposed to everything "serious, weighty, deep, solemn" - in a word, boring; opposes "the spirit of gravity, by which all things fall to the ground." Through the mouth of Zarathustra, the philosopher calls to "learn to fly", "to be light", "to dance not only with your feet, but also with your head" - that is, to be light and free in your thinking, just as a good dancer is free and light in dancing.

Witchcraft speaks with his body movements. …He feels like a god.” And in the philosophical poem Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche writes: "I would only believe in a God who could dance." His Zarathustra dances with nymphs in green meadows. For Nietzsche, dance becomes an attribute of the highest, divine art and thought. Therefore, dance for Nietzsche is a metaphor for thought. The divine lightness of the dance is opposed to everything "serious, weighty, deep, solemn" - in a word, boring; opposes "the spirit of gravity, by which all things fall to the ground." Through the mouth of Zarathustra, the philosopher calls to "learn to fly", "to be light", "to dance not only with your feet, but also with your head" - that is, to be light and free in your thinking, just as a good dancer is free and light in dancing.

At that time, which is called the Silver Age in Russia, very many became Nietzscheans, spoke his language, using the metaphor of dance. The poet Andrei Bely dreamed that his works were "a dance of self-fulfilling thought. " The same idea is echoed by today's Nietzscheans like the French philosopher Alain Badiou. For him, too, dance is “a metaphor for unsubdued, light, refined thought”, “a sign of the possibility of art inscribed in the body”. Free, unfettered, non-dogmatic thought is like a dance.

" The same idea is echoed by today's Nietzscheans like the French philosopher Alain Badiou. For him, too, dance is “a metaphor for unsubdued, light, refined thought”, “a sign of the possibility of art inscribed in the body”. Free, unfettered, non-dogmatic thought is like a dance.

Nietzsche exclaimed: "And let the day be lost for us when we never danced!" The influence of this philosopher-dancer, not only on his colleagues in the workshop, but also on the dancers, can hardly be overestimated. Isadora Duncan loved to read Nietzsche and quoted him in her reflections on dance. She was not the only one: Nietzsche was also read by the German dancer, one of the creators of Art Nouveau, Mary Wigman. Wigman put one of her compositions on a chapter from Nietzsche's poem "Thus Spoke Zarathustra", which is called "Song-Dance". Maurice Béjart and many other dancers read Nietzsche. These are real intellectuals from dance, artist-thinkers. They created not only choreography, but also artistic manifestos and programs: Duncan wrote "Dance of the Future", Rudolf Laban - "The Dancer's World", Mary Wigman - "Philosophy of Modern Dance".

What was the Nietzschean idea of these outstanding intellectual dancers? First, in the criticism of everything artificial. Isadora passionately criticized ballet for its alleged artificiality, conventionality, and the harm it does to the body. And she herself presented an alternative - a "natural" dance, similar to movement in nature. His examples are not six ballet positions (that is, several positions of arms and legs on which the entire choreography of classical ballet is based), but “wave vibrations and the rush of winds, the growth of living beings and the flight of birds, floating clouds and ... human thoughts ... about the Universe ... ". Duncan considered one of the manifestations of the extreme artificiality of the ballet that the movements in it are fractional, isolated, do not follow from each other, are not connected with each other and "are unnatural, because they seek to create the illusion that the laws of gravity do not exist for them." On the contrary, in a free dance, the actions “should carry in themselves a germ from which all subsequent movements could develop” - approximately in the same way as evolution occurs in nature. Dancing, Isadora believed, should be every person, and it will be his own, personal dance, corresponding not to ballet canons, but to the structure of his own body. In other words, she insisted on individuality, freedom, spontaneity in dance - motivating this by the fact that nature itself works this way. “Duncan is not just a name, but a program,” wrote one of her fans in Russia, art critic Alexei Sidorov.

Dancing, Isadora believed, should be every person, and it will be his own, personal dance, corresponding not to ballet canons, but to the structure of his own body. In other words, she insisted on individuality, freedom, spontaneity in dance - motivating this by the fact that nature itself works this way. “Duncan is not just a name, but a program,” wrote one of her fans in Russia, art critic Alexei Sidorov.

German dancer Mary Wiegmann (real name - Marie Wiegmann) lived 86 years (1886-1973). By the way, this is far from the only case of longevity among dancers - it seems to me that these people, who were burning with their work, simply could not die and leave this work on earth. So, Wigman began to create her dances in a unique place - on the mountain of Truth, Monte Verita. This was the name of the community of artists, philosophers, anarchists, theosophists, vegetarians, nudists who set up a colony in Italian Switzerland, on the shores of Lake Maggiore. There at 19In the year 13, Rudolf Laban, the son of a field marshal from Austria-Hungary, arrived, who at that time was studying architecture in Paris. And here he began - like Zarathustra dancing in "round dances" - to lead his "moving choirs". It was like a pantomime performed by a group of people. Wigman, Suzanne Perrotte, and many other future dancers, creators of new styles - expressionism and modernity, participated in these "choirs" (where there was no music and songs, only movement and gestures). In the warm Swiss climate, they danced on the banks of Lago Maggiore, naked or half-clothed, celebrated mass to the sun, and thought up other rituals for the new, liberated humanity. What the colonists on Monte Verita offered - given that at that very time a fratricidal world war was going on in Europe, in which Christians destroyed Christians - was not the worst offer to humanity.

And here he began - like Zarathustra dancing in "round dances" - to lead his "moving choirs". It was like a pantomime performed by a group of people. Wigman, Suzanne Perrotte, and many other future dancers, creators of new styles - expressionism and modernity, participated in these "choirs" (where there was no music and songs, only movement and gestures). In the warm Swiss climate, they danced on the banks of Lago Maggiore, naked or half-clothed, celebrated mass to the sun, and thought up other rituals for the new, liberated humanity. What the colonists on Monte Verita offered - given that at that very time a fratricidal world war was going on in Europe, in which Christians destroyed Christians - was not the worst offer to humanity.

Almost all modern dance came from a small commune in the Swiss Alps. We have already mentioned Wigman - here she created her ingenious dance-rituals: she came up with her "Dance of the Witch", then she created the "Dance Song" to the words of Nietzsche, and later, with her students, staged "Monument to the Dead" ("Totenmal") . In her article "The Philosophy of Modern Dance" (1933), she wondered if classical ballet was possible after the World War. Wigman believed that dance should be updated - not only in terms of new movements, steps or steps, but also in terms of the seriousness of the questions that choreographers ask.

In her article "The Philosophy of Modern Dance" (1933), she wondered if classical ballet was possible after the World War. Wigman believed that dance should be updated - not only in terms of new movements, steps or steps, but also in terms of the seriousness of the questions that choreographers ask.

In addition to Wigman, other modern choreographers also began to address current political and existential issues, questions about life. Kurt Joss staged the contemporary ballet "Green Table" - about those negotiations that European diplomats failed, which led to the world war. Pina Bausch began to study with Joss - she later created her own dance theater in the German city of Wuppertal, one of the most famous in the world. In the 20th century, along with dance-entertainment, a dance-reflection, dance-satire appeared. This is the result of real intellectual dancers appearing—or, as in the case of Laban, intellectuals began to dance, to become dance artists.

This is the result of real intellectual dancers appearing—or, as in the case of Laban, intellectuals began to dance, to become dance artists.

They opposed themselves to that light entertainment genre that ballet was traditionally considered to be. It must be said that in the 18th and 19th centuries ballet served as light entertainment, divertissement: ballets in the theater were given in intermissions between two short operas or between two acts of an opera, and often it was called that - ballet divertissement (divertissement in French "entertainment") . To distance themselves from this tradition, the new choreographers called their style not ballet, but modern dance. Modern included Mary Wigman, Kurt Joss and other students of Laban in Europe, and in the USA Martha Graham and other dancers. In our country, modern dance began to develop successfully in 1920s, but was banned for ideological reasons. After that, academic ballet reigned for a long time, and other genres (except, perhaps, folk stage dance) became marginal.

At first, classical ballet remained aloof from the processes that took place in modern dance. However, here, too, choreographers-philosophers appeared who staged meaningful performances. Maurice Bejart also belonged to the dancing philosophers, or philosophizing dancers (he left us relatively recently, in 2007). His real name is Berger; he is the son of the philosopher Gaston Berger, who, in particular, wrote a treatise on Husserl's phenomenology. Maurice graduated from the Lyceum with honors in philosophy, and then he took and went to study classical dance. As in philosophy, he was also successful in ballet - despite his small stature and short legs, he performed the title role of Siegfried in Swan Lake.

In the mid-1950s, Béjart founded his first company and staged his first ballet, La Symphonie for a Solo Man (La Symphonie pour un homme seul) to "concrete music" by contemporary composer Pierre Henry. Specific music was an electronic compilation of musical fragments, sounds of nature and household noises - for example, factory horns. The music alone provoked the audience - there really was a scandal at the premiere. Moreover, the theme is not typical for ballet: existentialism, loneliness, anxiety. These sentiments, however, were very typical of those years when Jean-Paul Sartre was the most popular philosopher. Bejart, thus, immediately declared himself as a choreographer-philosopher. And five years later he finally read Nietzsche, and this reconciled his two strongest passions - philosophy and dance. And his dance changed, became more powerful, passionate and vital. Having created a new company - "Ballet of the 20th century", Bejart turns to ancient myths, in which movement, dance have a sacred meaning, and puts on the ballets "Orpheus", "The Rite of Spring", "Sacrifice".

The music alone provoked the audience - there really was a scandal at the premiere. Moreover, the theme is not typical for ballet: existentialism, loneliness, anxiety. These sentiments, however, were very typical of those years when Jean-Paul Sartre was the most popular philosopher. Bejart, thus, immediately declared himself as a choreographer-philosopher. And five years later he finally read Nietzsche, and this reconciled his two strongest passions - philosophy and dance. And his dance changed, became more powerful, passionate and vital. Having created a new company - "Ballet of the 20th century", Bejart turns to ancient myths, in which movement, dance have a sacred meaning, and puts on the ballets "Orpheus", "The Rite of Spring", "Sacrifice".

In 1961 Béjart staged perhaps his most popular ballet, Boléro. Bejart's favorite dancer Argentine Jorge Donn, Maya Plisetskaya, Sylvie Guillem shone in it ... Bejart was not the first to turn to Ravel's music. In fact, this composition was composed by Ravel at the request of the dancer Ida Rubinstein. The ballet "Bolero" was staged for her by the sister of the famous Vaslav Nijinsky, the wonderful performer and choreographer Bronislava Nijinsky herself. The ballet takes place in a tavern, and in the finale, Ida jumped on the table and danced on it, surrounded by enthusiastic male patrons. If you have seen Béjart's "Bolero" (or you can watch it right now), then you know that this dance is also performed on a raised platform. But due to a completely different choreography, idea, mood, this dance is more like not drunken fun in a pub, but a very serious and passionate sacrificial ritual. Even Bejart's table is not a table, but an altar on which sacrifice is made.

Such was the increased seriousness and even sacredness of modern dance in comparison with its predecessor, classical ballet of the 19th century. It should be added that Bejart himself converted to Islam in the late 1960s, but Buddhism was also close to him. And he called his last dance schools "Mudra" (which means "gesture" in Hindi) - in Brussels, and "Rudra" (after the name of the deity) - in Lausanne. Over the past twenty years, Béjart has staged almost a hundred ballets, including, a year before his death, Zarathustra: Song and Dance. Zarathustra for him is a philosopher, a prophet, a legislator, a dancing god who dances with his feet and head.

It should be added that Bejart himself converted to Islam in the late 1960s, but Buddhism was also close to him. And he called his last dance schools "Mudra" (which means "gesture" in Hindi) - in Brussels, and "Rudra" (after the name of the deity) - in Lausanne. Over the past twenty years, Béjart has staged almost a hundred ballets, including, a year before his death, Zarathustra: Song and Dance. Zarathustra for him is a philosopher, a prophet, a legislator, a dancing god who dances with his feet and head.

More to read:

Badiou A. Small guide to inaesthetics. St. Petersburg, 2014.

Bezhar M. A moment in the life of another. Memoirs. M., 1989.

Valerie P. On Art. Soul and dance. M., 1993.

Duncan A. Dance of the future.

Nietzsche F. Thus spoke Zarathustra.

10 quotes from the memoirs of Korney Chukovsky

The looted library in Peredelkino, Blok's mania for cleanliness, Leonid Andreev's donkey, and "false ideas about the world of animals and insects" in children's fairy tales.