How to spot dance

Spotting 101: Help Your Students Master This Turning Essential

Spotting 101: Help Your Students Master This Turning Essential

Even before 19th century Italian ballerina Pierina Legnani first performed the feat of 32 consecutive fouettés, dancers have known that “spotting”—or whipping the head quickly around during a turn so that the eyes remain focused in the same location—is an essential part of multiple turns.

Spotting keeps a dancer from becoming dizzy during pirouettes, and it also gives turns a certain aesthetic sharpness. Dancers use spotting as a way to balance themselves and keep track of where the body is in space. Most dancers learn to spot when they first learn to execute pirouettes, but there are a few specific points that can improve even an advanced dancer’s spotting technique. Here are some tips from the experts to help you teach better turns.

Focus

Vaganova-trained choreographer and teacher Nikolai Kabaniaev stresses that students should focus their eyes when spotting, picking an object on which to concentrate and coming back to it during each revolution. “The entire time, students should really see what is in front of them,” he says. Teaching your students to maintain a specific focus will help them orient themselves and improve balance.

Many dancers like to spot their own image in the mirror, but they should be reminded that during a performance, they will need to find other objects on which to focus. It’s helpful to have your students practice by picking out specific items to spot, even when working in a mirrored classroom.

Maintain Alignment

According to Dr. Kenneth Laws, professor emeritus of physics at Dickinson College and author of Physics and the Art of Dance, many dancers misguidedly believe that spotting provides the impetus for turning. However, even though it may feel as though whipping the head around one last time helps eke out a final rotation, it is not physically possible for spotting to create enough force for an extra turn.

“In a correct pirouette, you don’t move your head from the axis of rotation,” Laws explains. “And there’s not much you can do to change the rotational momentum or speed with just your head, if it’s properly aligned.” Although students should relax their necks during a turn so that they have the maximum range of motion from side to side, allowing the head to dip and swoop does not add any momentum to the turn. It’s important to correct students who try to “nod” their way into one last pirouette.

Jorge Esquivel, former principal dancer with the Ballet Nacional de Cuba and now a teacher at San Francisco Ballet School, tells dancers to choose a focal point that keeps the eyes high, so that the neck is lengthened and straight. If the eyes are cast slightly downward, he says, the head has a tendency to droop forward slightly, throwing off the axis of rotation.

Let the Spot Lead

Esquivel explains that most students do not allow the spot to “lead” the turn; they tend to leave the head behind too long at the start of each revolution. “The turn of the head must not be delayed,” he emphasizes. “There must be a strong accent of the head, an attack. Get your dancers to find the spot fast!” If the head stays too long before whipping around, as Esquivel shows by leaving his head until his chin is nearly in line with his shoulder, the neck muscles begin to pull the head back slightly. By attacking the spot, the dancer can more easily keep her vertebrae in line.

“The turn of the head must not be delayed,” he emphasizes. “There must be a strong accent of the head, an attack. Get your dancers to find the spot fast!” If the head stays too long before whipping around, as Esquivel shows by leaving his head until his chin is nearly in line with his shoulder, the neck muscles begin to pull the head back slightly. By attacking the spot, the dancer can more easily keep her vertebrae in line.

If a student’s spot seems slow, Kabaniaev suggests the following exercise: Have the student stand on two feet with the arms in front as if she were executing a pirouette. Then ask her to perform three or four turns by taking small steps, concentrating solely on the technique of spotting as she does so, to build correct muscle memory. “You can start with a slower speed and then go faster as the coordination improves,” says Kabaniaev.

Keep the Rhythm

“It is important for students to use the spot to keep the rhythm of the turn,” Esquivel says. Have your students coordinate their spots with musical beats, if possible, so that their turns begin and end in time with the music.

Have your students coordinate their spots with musical beats, if possible, so that their turns begin and end in time with the music.

Esquivel advises teachers to help students choose the pacing of the spot to suit the number of pirouettes. “The spot for one or two pirouettes is very different from the spot for five or six pirouettes,” he says. “It varies from student to student, but the dancer must know beforehand the right rhythm and the exact amount of force needed to fit either the slower pirouette or the faster pirouette.” Helping your students find that perfect amount of force will allow them to execute multiple turns cleanly and musically.

How to Spot in Ballet to Improve Your Turns – On the Way to the Barre

Sarah | On The Way To The Barre

How to Spot in Ballet to Improve Your Turns

When dancers turn, they keep their eyes focused on one location to avoid getting dizzy. As they rotate, their heads whip faster than their bodies, returning their eyes as quickly as possible to the same spot. This is what is called “spotting”.

As they rotate, their heads whip faster than their bodies, returning their eyes as quickly as possible to the same spot. This is what is called “spotting”.

If you’ve ever been sea-sick or car sick, you may understand how unpleasant being dizzy can be. In those situations staring at the horizon can help orient your brain and make you feel better. The reason we get dizzy when we spin around quickly is the fluid in our inner ears that controls balance continues to slosh around for a little while after we stop moving. This makes our brains think we’re still spinning, producing the feeling of dizziness. Spotting, keeping your eyes fixed when you turn, like staring at the horizon when you are motion sick, tricks the brain into thinking it isn’t moving. It may not keep you 100% dizzy free, but it will help, and the benefit is, spotting will help your turns immensely.

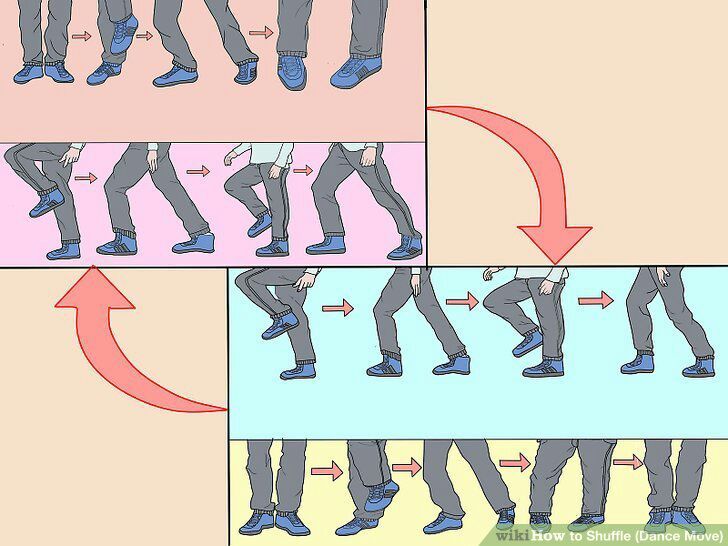

How to SpotStand and fix your eyes on a point in front of you. We usually practice this in the dance studio facing the mirror, and I tell dancers to spot their own eyes, but if you are at home, just look at something small that is at or a little above eye level, like a refrigerator magnet or the “12” of the clock hanging on a wall. Have your feet parallel a few inches apart, in “sixth position,” my teacher would have said. Start to march your feet so that your body is turning very slowly to the right but keep your head facing that magnet or clock (or whatever you’ve chosen as your spot point) with your eyes fixed on that point. When your body has turned so far around that your neck cannot keep your head looking over your left shoulder anymore, turn your head quickly to the right to look over your right shoulder and find that same spot point again with your eyes. Your body will not be facing forward yet – that is correct, your head will be quicker! Continue walking your feet and turning your body slowly until your body matches your head and all parts are facing your spot point. Did you do it? Don’t change your spot point midway through! If you don’t understand this, comment below and I will post a link to a video. Now that you’ve done it to the right, try it to the left.

Have your feet parallel a few inches apart, in “sixth position,” my teacher would have said. Start to march your feet so that your body is turning very slowly to the right but keep your head facing that magnet or clock (or whatever you’ve chosen as your spot point) with your eyes fixed on that point. When your body has turned so far around that your neck cannot keep your head looking over your left shoulder anymore, turn your head quickly to the right to look over your right shoulder and find that same spot point again with your eyes. Your body will not be facing forward yet – that is correct, your head will be quicker! Continue walking your feet and turning your body slowly until your body matches your head and all parts are facing your spot point. Did you do it? Don’t change your spot point midway through! If you don’t understand this, comment below and I will post a link to a video. Now that you’ve done it to the right, try it to the left.

As you practice spotting, it is helpful to keep your neck and head really loose so that your neck can turn. Spotting is not just in your eyeballs-your chin will be above one shoulder and then you have to turn your head so your chin is over the other shoulder.

Spotting is not just in your eyeballs-your chin will be above one shoulder and then you have to turn your head so your chin is over the other shoulder.

Try keeping your chest open and even squeeze your shoulder blades together. You may find your neck is a bit easier to turn this way.

It’s also helpful to keep your head straight up and down and not let your head tilt side to side as you are turning. That way the fluid in your ears will only have one axis of dizziness with which to contend.

Pro-tip: If you are already quite good at spotting, try – during pirouettes – to spot yourself in the mirror using the eye of your standing leg. It’s a really powerful tip that can help your pirouettes.

Getting Un-DizzyIf you get dizzy after crossing the floor in a series of turns like chaines or other turns, or even after one turn, even when you are spotting correctly, that is totally okay. This is a work is progress and so are you. You will get better at it, and your inner ears will also get better at adjusting to turning over time! In the meantime, here are some things you can do to quickly get un-dizzy so you can keep dancing:

- Jump up and down three times staring at a stationary object.

I imagine the fluid in my ears gets jolted out of it’s swooshing motion and gets settled back in place thanks to gravity, as a result of the three little hops. This method works best for me.

I imagine the fluid in my ears gets jolted out of it’s swooshing motion and gets settled back in place thanks to gravity, as a result of the three little hops. This method works best for me. - Another thing you can try is to place one hand, fingers together, vertically in between your eyes – splitting your face in half, from your forehead to your nose. I like this method too.

- You can also put your hand horizontally underneath your eyes. I think this gives your eyes an imitation horizon with which to orient your brain, like staring at the horizon except in the dance studio.

- Some people find that a few revolutions in the opposite direction works better for them. Try each one and see what works best for you – different methods may help you at different times.

Neck Range of Motion

Having good mobility and range of motion in your neck can also help your spotting. If you get tense in your neck like I sometimes do, you may not find that sweet, easy spot where you sail around and the whipping action of your head easily transfers down, giving your body a little added momentum each time you rotate. To increase the range of motion and reduce tension in your neck, try this:

To increase the range of motion and reduce tension in your neck, try this:

First, turn your head to the right and left to test your range. One side may be more restricted depending on what shoulder you carry your purse, how you sleep and other factors. Place the heel of your right hand to the right side of your head. Turn your head to the right again, but this time use your hand to prevent your head from turning. You will be doing a lot of work with your neck and arm but don’t let your head move. After holding this for several seconds, release your head and try gently turning your head to the right again and see if your neck is a bit freer this time. Once you’ve done it to the right, do the left as well. You can also do this with lateral (ear to shoulder) and front any back movements of your head to release your neck. If you have neck issues or this hurts, just skip it or ask your doctor.

Like anything else, it takes a bit of practice and it takes reminding yourself to use your now-excellent spotting when it comes time to turn. When you relax your neck and focus your eyes, almost as if instead of serious dance business, it were more like playing in a grassy field on a summers day – that is when you’ll find the sweetest spot of all.

When you relax your neck and focus your eyes, almost as if instead of serious dance business, it were more like playing in a grassy field on a summers day – that is when you’ll find the sweetest spot of all.

~ Sarah

Please see the Classes page for my current teaching schedule. I’d love to see you at the barre!

Like this:

Like Loading...

I am a dancer, actor, teacher, writer, cat-mom, sister, friend, human. View all posts by Sarah | On The Way To The Barre

What is dance • Episode transcript • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

CourseWhat is modern danceAudio lecturesMaterialsContents of the first lecture from Irina Sirotkina's course "What is modern dance"

Although everyone has an idea of dance, it is not easy to define it. Probably the most general definition of dance is the movement of a person, moving him in space to music or rhythm. But questions immediately arise. What movement? Moving where? And if this is a movement not of the whole body, but of one finger? Try moving your finger now. Will it be a dance? And with the whole hand? And if you move your shoulder a little, turn on the body and turn your head? You have probably already felt how difficult it is to draw a line and say where "just movement" ends and "dance" begins.

But questions immediately arise. What movement? Moving where? And if this is a movement not of the whole body, but of one finger? Try moving your finger now. Will it be a dance? And with the whole hand? And if you move your shoulder a little, turn on the body and turn your head? You have probably already felt how difficult it is to draw a line and say where "just movement" ends and "dance" begins.

The second word in our definition is man. But can only humans really dance? And if, for example, autumn leaves are spinning on the path of the park, can it be called a dance?

And finally, is the presence of music in the dance obligatory? It is known that many modern dance artists preferred rhythm alone. For example, Mary Wigman's favorite musical instrument is the gong. Trying to make dance an independent, independent art, they tried to free themselves from music as from something imposed on the dance from the outside, and declared that they would dance "the music of their own body. " And Alexander Sakharov, a dancer from the Russian Empire, who lived and worked in Munich at the beginning of the 20th century, participated in the Blue Rider art association, even danced paintings - abstract paintings by Wassily Kandinsky.

" And Alexander Sakharov, a dancer from the Russian Empire, who lived and worked in Munich at the beginning of the 20th century, participated in the Blue Rider art association, even danced paintings - abstract paintings by Wassily Kandinsky.

So, we return to the fact that it is hardly possible to give any formal definitions of dance that claim to be rigorous. However, you can try to answer the question "What is dance?" Not directly, but by pointing to the contexts in which it is included.

Definitely, dance is a part of the movement culture of mankind. Speaking of motor culture, we draw an analogy with visual culture, which everyone is familiar with: these are the visual images that we produce, among which we live, our man-made visual environment.

Aleksey Gastev, one of the founders of the so-called movement for the rationalization of labor, which developed in our country in the 1920s, spoke about motor culture. Motor culture Gastev called "the sum of the motor habits of the people", a set of "motor skills and abilities" available to a person. Gastev was himself a skilled worker at a metal plant, and he had in mind, first of all, the culture of labor movements. After the revolution, millions of soldiers, yesterday's peasants, poured into the city, and Gastev believed that they needed to be taught the culture of movements, and not only labor, but also everyday habits that were new to them, the skills of city life - to eat, sleep, wash.

Gastev was himself a skilled worker at a metal plant, and he had in mind, first of all, the culture of labor movements. After the revolution, millions of soldiers, yesterday's peasants, poured into the city, and Gastev believed that they needed to be taught the culture of movements, and not only labor, but also everyday habits that were new to them, the skills of city life - to eat, sleep, wash.

Then, in Soviet Russia, they talked a lot about the creation of a "new man" - and so, the inoculation of a new culture of movements was a real way to create this new man. At the same time, the sciences of biomechanics appeared (the same Gastev helped its birth), the physiology of movements, and kinesiology. They - each in their own way - studied movement as a physical process: biomechanics - the structure and functioning of the motor apparatus; physiology - muscle fatigue, coordination and regulation of movements from the nervous system; Kinesiology is a practical discipline, the application of biomechanics and physiology to the goals of therapy and movement improvement.

The concept of “body technique” is close to the concept of motor culture. The French ethnographer and sociologist Marcel Mauss proposed in 1930 to refer to the ways in which people in different societies use their bodies: it is similar to what Gastev called "movement habits." At the same time, Moss (as one might expect from an ethnographer) cited as an example not only some exotic movements, but also body techniques of a contemporary person. He tells, for example, that when he was little, he was taught to swim breaststroke. And there was such a habit - to draw in water and spit it out, just like a paddle steamer does. So, Moss swam in this way until the end of his life and was never able to switch to a new, modern crawl. These body techniques are engraved in our body, we carry them in ourselves as part of our "I".

And one more concept, useful for those who want to understand what dance is: the concept of the modes of functioning of the body. I first heard about it from the St. Petersburg philosopher Alla Mitrofanova, but it appeared, most likely, earlier. In the work of the body, there can be different modes that a person can consciously switch, like speeds on a gearbox. For example, the body may be tense, tense, muscular, working, ready to make a physical effort. And it can be relaxed, resting, in a state of calm tone, without excessive stress. Choreographers have long noticed that these modes can be used to create different moods for the audience, different impressions of the dance. Recall, for example, the resting body of the faun Vaslav Nijinsky in his ballet The Afternoon of a Faun: this body is soft, relaxed, but ready for effort, for a jump, like that of an animal.

Petersburg philosopher Alla Mitrofanova, but it appeared, most likely, earlier. In the work of the body, there can be different modes that a person can consciously switch, like speeds on a gearbox. For example, the body may be tense, tense, muscular, working, ready to make a physical effort. And it can be relaxed, resting, in a state of calm tone, without excessive stress. Choreographers have long noticed that these modes can be used to create different moods for the audience, different impressions of the dance. Recall, for example, the resting body of the faun Vaslav Nijinsky in his ballet The Afternoon of a Faun: this body is soft, relaxed, but ready for effort, for a jump, like that of an animal.

And the bodies of the dancers in the "Dances of Machines" are the finale of Fyodor Lopukhov's ballet "The Bolt", staged in the early 1930s on a production theme - tense, dynamic, high-speed.

In the last third of the twentieth century, a special discipline appeared - the anthropology of movement and dance. Returning to our question, what is dance: when anthropologists were faced with a variety of forms and types of dance, with very different movements, which in different cultures are classified as dance, they formulated the question in a different way. They began to ask not "What is dance?", but "What do people do when they dance?" For example, people can perform a ritual in this way. Or get acquainted. They can, if they are professional dancers, earn a living or participate in the creation of a performance. They can celebrate something, or they can grieve - for example, in archaic rites, where dances were part of the mourning ceremony and people danced not only at weddings, but also at funerals, saying goodbye to the deceased.

They can celebrate something, or they can grieve - for example, in archaic rites, where dances were part of the mourning ceremony and people danced not only at weddings, but also at funerals, saying goodbye to the deceased.

Around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, a movement for the emancipation of the body began. In the 19th century, in a decent society, the body was not accepted not only to be shown, but it was impossible to mention it. If it was required, for example, to talk about the body and its parts, then instead of "legs" they came up with the euphemism "lower limbs", and the body itself was hidden under clothes - multi-layered, tight and clumsy. Women wore, among other things, a tight corset in which it was difficult to breathe, petticoats in which it was uncomfortable to walk and run, and men - high collars and a tie in which you couldn’t even turn your head. And when, say, a performance from the life of the ancient Greeks or Egyptians was going on in the theater, the dancers, instead of taking off part of their clothes and walking around like half-naked Greeks and Egyptians, on the contrary, pulled tights over their feet and drew toes on its fabric. The sight of bare feet, bare skin was considered indecent, and nudity in public places could only be imitated.

The sight of bare feet, bare skin was considered indecent, and nudity in public places could only be imitated.

By the way, the clothing reform began with a dance, or rather with several dancers, one of whom is Isadora Duncan. She is called the founder and even the grandmother of modern dance It is customary to call modern dance such areas of choreography of the twentieth century as modern, postmodern and contemporary dance (this term usually combines different currents of stage dance that developed in the second half of the century, primarily in Europe and North America, and incorporating elements of not only modern and postmodern, but also neoclassical ballet, jazz and other types of dance and movement culture). , but most of all she looks like a dance revolutionary. However, we will return to her dance revolution, but for now I will say that Isadora has greatly advanced the reform of clothing - not only in the theater, but also in life, everyday clothes. She herself abandoned the corset, shoes and stockings in life and on the stage and dreamed that people in the future would become free, with an absolutely free body - and return, already at a new stage, to the golden age of Antiquity, when happy humanity spent time in communication with nature and dancing in green meadows.

Isadora was wrong: it is impossible to return to the golden age. But she and her associates supported a very important movement for the culture of the body, the culture of the body. The creators of various gymnastics, athletes, vegetarians, "naturists", nudists, progressive doctors and physiologists who discovered the laws of self-regulation and wrote about the "wisdom of the body", and many others have already participated in this movement. At the beginning of the 20th century, dance joined this movement. Followers of Isadora even got the name "sandals". Now it seems natural for us not only to walk barefoot or in sandals and sandals, but also to take care of our body, its hygiene in general, to think about how to improve it or at least maintain its health and youthful shape. But let's not forget that all of this, including improved bodily health and increased (hopefully) longevity, is partly due to the new dance.

More to read:

Butterworth J. Dance. Theory and practice. Kharkiv, 2016 .

Dance. Theory and practice. Kharkiv, 2016 .

Sirotkina I. "How can we know the dancer from the dance?": Anthropology of movement and dance. New literary review, No. 145, 2017 .

Williams D. Anthropology and the Dance: Ten Lectures. Urbana, 2004 .

What Is Dance? Readings in Theory and Criticism. Oxford, 1983 .

Radio Arzamas Viking Age Scandinavia. Part 2

The second half of Fyodor Uspensky’s course is about how medieval Icelanders managed without power and what they considered the worst punishment, why baptized authors continued to talk about pagan gods, and why King Harald the Blue-toothed transferred the bones of his pagan parents to the church

be aware of everything?

Subscribe to our newsletter, you'll love it. We promise to write rarely and to the point

Courses

All courses

Special projects

Audio -lectures

10 minutes

1/7

What is a dance

than the usual movement differs from the dance, which is being studied by biomechanics and kinesiology and as at the beginning of the 20 body

Reading by Irina Sirotkina

How does ordinary movement differ from dance, what is studied by biomechanics and kinesiology, and how attitudes towards the body changed at the beginning of the 20th century

16 minutes

2/7

Dance as a philosophy

Why Nietzsche’s God must dance and how the choreographers talked about loneliness, the future of mankind and the causes of the First World War

Reading Irina Sirotkina

loneliness, the future of mankind and the causes of the First World War

13 minutes

3/7

How is dance different from dance

Why should the authorities control the festivities, what is the utopia of ecstatic dancing and what is the danger of an undisciplined body

Reading by Irina Sirotkina

Why should the authorities control folk festivals, what is the utopia of ecstatic dancing and what is the danger of an undisciplined body

13 minutes

4/7

Dance: elements or art?

Why teach natural movements, how to make a dancer a "non-human" being and what do pointe shoes and bio-prostheses have in common

Reading Irina Sirotkina

Why teach natural movements, how to make a dancer a "non-human" creature and what do pointe shoes and bio-prostheses have in common

15 minutes

5/7

How dance affects the viewer

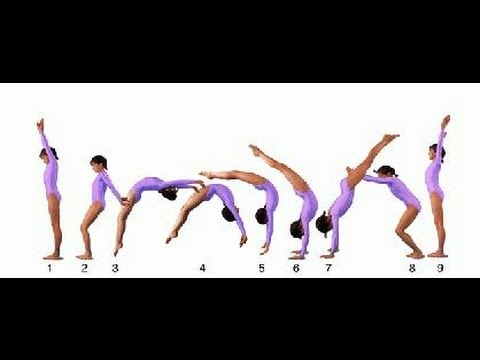

Where does dexterity come from, what is the attraction of acrobatics and why is it more interesting to watch dance if you have tried dancing yourself

the attractiveness of acrobatics and why it is more interesting to watch dance if you have tried dancing yourself

14 minutes

6/7

The ideal body for dancing

be able to dance everything

Reading by Irina Sirotkina

How does a ballet body differ from a jazz body, why Martha Graham would not tolerate virgins in her troupe, and is it possible to be able to dance everything

12 minutes

7/7

ordinary movements of an untrained body that shocked the audience in Isadora Duncan and why dance is a desire machine

Reads by Irina Sirotkina

What ordinary movements of an untrained body can tell about what shocked the audience in Isadora Duncan and why dance is a desire machine

Materials

9 Modern Dance languages

How to find out Pina Bausch, George Balanchin and other choreographers for several movements of

What danced in the XX century

The most fashionable dances of salons and discos and the most daring phenomena of choreography

History History contemporary dance in 31 productions

Ballets, performances and performances that changed the idea of choreography

Test: Distinguish ballet from opera

Find among the photographs not Giselle, not The Nutcracker and not Swan Lake

What can I do to avoid losing my subscription after Visa and Mastercard leave Russia? Instructions here

Dance | it's.

.. What is the Dance?

.. What is the Dance? InterpretationTranslation

- Dance

-

Depiction of dance in ancient Greece

Ballroom dance

Modern ballroom dance, 2008

Dance (via Pol. taniec from Middle Eastern-New tanz [1] ) is an art form in which an artistic image is created through rhythmic plastic movements and changes in the expressive positions of the human body. Dance is inextricably linked with music, the emotional and figurative content of which is embodied in its movements, figures, and composition.

Contents

- 1 Definitions

- 2 Directions and styles of dance

- 2.1 Acrobatic dance

- 2.2 Ballet

- 2.

3 Ballroom dancing

3 Ballroom dancing - 2.4 Hustle

- 2.5 Historical dance

- 2.6 Dances of Latin America

- 2.7 Folk dance

- 2.8 Swing

- 2.9 Ritual dance

- 2.10 Modern dance (beginning - middle of the 20th century)

- 2.11 Contemporary dance (late 20th - early 21st century)

- 3 Dance films

- 4 See also

- 5 Notes

- 6 Links

Definitions

The definition of what dance is is highly dependent on historical and cultural contexts. Havelock Ellis defined dance as a virtuoso development of the sexual impulse [2] .

American choreographer Marpuk defined dance as a genuine expression of the deepest emotional feelings, released through the movement of the body. Anthropologist Joan Kealiinohomoku defines it as follows: “dance is a transitory, fleeting mode of expression that takes place in a given form and style through body movements” [3] .

-Step-18.jpg/aid1640374-v4-728px-Shuffle-(Dance-Move)-Step-18.jpg)

Julie Charlotte Van Camp ( Julie Charlotte Van Camp ) in her dissertation [4] collected the main provisions that make up the definitions of dance:

DANCE is a rhythmic movement performed by one or more people in time with music. A virtuoso is one who perfectly masters the technique of his art, his business.

Dance is a human movement that is formalized, that is, performed in a certain style or pattern, has qualities such as grace, elegance, beauty, is accompanied by music or other rhythmic sounds, has the purpose of telling a story, and has the purpose of communication or expression. feelings, themes, ideas that can be promoted by pantomime, costume, scenery, stage lighting, etc.

She also notes that the various definitions of "dance" are unanimous only on the first point - that dance is a human movement.

Dance has existed and exists in the cultural traditions of all human societies. Over the long history of mankind, it has constantly changed, reflecting cultural development.

There is a huge variety of types, styles and forms of dance.

There is a huge variety of types, styles and forms of dance. Dance is used as a way of self-expression, social communication, for religious purposes, as a competitive sport, as an exemplary art form.

Dance (folk and modern) is one of the nominations of the Delphic Games.

Through dance we can see and feel music.

Directions and styles of dance

Acrobatic dance

Cheerleading (cheerleading group)

Acrobatic rock and rollBallet

Ballet

- romantic

- classic

- modern

Ballroom dance

- Ballroom dance

- European program

- slow waltz

- tango

- viennese waltz

- foxtrot

- quickstep (fast foxtrot)

- Latin American program

- samba

- cha-cha-cha

- rumba

- paso doble

- jive

- European program

Hustle

- Hustle

History dance

- History dance

- mazurka

- minuet

- polonaise

- Pavane

- Rigaudon

- Allemande

- Burre

- Gavotte

- Courant

- Bassdance

Dances of Latin America

- Argentine tango, not to be confused with European tango.

- Latin dance

- samba

- rumba

- bachata

- merengue

- mambo

- salsa

- zouk

- lambada

- cumbia

- tango

- pachanga

- bolero

- begin

Folk dance

- Folk dance

- lasso

- attan

- hopak

- jig

- Scottish dancing

- Krakowiak

- kochari

- lezginka

- polka

- ril

- belly dance

- gypsy dancing

- trepak

- uzundere

- round dance

- hornpipe

- chardash

- yalli

Swing

- Swing

- Boogie-woogie

- Lindy Hop

- Balboa

- Charleston

- Jive

- Rock and roll

- East Coast Swing

- West Coast Swing

- Modern Jive

ritual dance

- ritual dance

- Herself

- Kecak

Modern dance (beginning - middle of the 20th century)

- free dance

- musical movement

- modern dance

- modern jazz

- contemporary

- contact improvisation

- butoh

Modern dance (late XX - early XXI century)

- Club dance

- Industrial Dance

- Waacking

- Vogue

- House

- Strip dance

- Go-Go (Club Dance)

- Hakka

- Jumpstyle

- Shuffle

- Square Dance

- Street dance

- Hip Hop

- House

- Breaking

- Popping

- Electro dance (Tektonik)

- C-walk

- Drum'n'Bass Step

- Dubstep

- Crump

- Locking

- Flexing

- Lameriga

Dance films

- Flash-dance (1983)

- Dirty dancing (1987)

- Dirty Dancing 2 or Havana Nights (2004)

- Dirty Dancing (TV Series)

- Shall We Dance (2005)

- Dance with me (1998)

- Striptease 1996)

- Show girls (1995)

- One Last Dance (2003)

- Dance Academy (TV series) (2010 Dance Academy)

- Dancing Machine (1990)

- Disco dancer (1982)

- Bring It On (2000)

- Chorus Line (A Chorus Line, 1985)

- Bal (Le Bal, 1983)

- The Tango Lesson (1997)

- Macarena (Macarena, 1998)

- Tango Bar (1988)

- Step Up

- Step Up 2.

The Streets

The Streets - Step up 3D ( Step up 3D , 2010)

- Step up 4. Revolution , 2012

- Crybaby

- Saturday Night Feaver (1977)

- The Dancer

- Billy Elliot (2000)

- Stomp the Yard

- How She Mooved

- Make It Happen (2009)

- Take the Lead (2006)

- Australian Tango (1992)

- Winter evening in Gagra

- Another Cinderella Story

- To the rhythm of the tango

- Flamenco ( Flamenco , 1995)

- Proscenium - 1.2 ( Centerstage )

- Time to dance

- Save the last dance , 2001)

- Salsa Queen ( Die Salsa Prinzessin , 2001)

- Street Dance ( Street Dance , 2010)

- Street Dance 2 ( Street Dance 2 , 2012)

- Moulin Rouge ( Moulin Rouge , 2001)

- Burlesque ( Burlesque , 2010)

- Black Swan ( Black Swan , 2010)

- Honey (Honey, 2003)

- Honey 2 (Honey 2, 2010)

- The Maiden Dances to Death (Hungary, 2011)

See also

- Choreography

"My dad Baryshnikov"

- Dance recording

free (2011)

Notes

- ↑ Vasmer M.

Etymological dictionary of the Russian language. — Progress. - M., 1964-1973. - T. 4. - S. 19.

Etymological dictionary of the Russian language. — Progress. - M., 1964-1973. - T. 4. - S. 19. - ↑ Havelock Ellis. The Art of Dancing // The Dance of Life. — Houghton Mifflin Company, 1923.

- ↑ John Blacking, Joann W. Kealiinohomoku. The Performing arts: music and dance. - Walter de Gruyter, 1979. - P. 21. - 344 p. — ISBN

- 78700, 978

- 78707

- ↑ Julie Charlotte Van Camp Philosophical problems of dance criticism. PhD dissertation (1981). Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

Links

- “On the Meaning of Dance” Article by M. Voloshin;

- Ritual Dance and Myth by L. P. Morin

- Ballet and dance music. Dance history. Gallery

- Ballroom dancing

- Petrovsky L. Rules for noble public dances, published by the dance teacher at the Sloboda-Ukrainian gymnasium Ludovik Petrovsky.