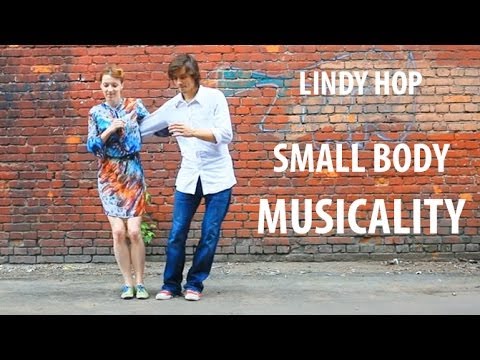

How to improve musicality in dance

How To Train Your Musicality As A Dancer

Musicality is a dancer’s sensitivity to and/or knowledge of music.

See Related Article: The Ultimate Guide To Musicality For Beginner Dancers

At its core, dancing is showing your musicality in physical form. It is a nonverbal way of telling people “this is what I hear in this song.”

See Related Article: How To Dance Better By Understanding Body Awareness

Musicality in ChoreographyChoreography is a thought out and planned form of showcasing your musicality.It’s like writing a research paper or doing homework.You take your time to prep to really understand the material and research it (by listening to the song repeatedly and exploring movements), and process the information you’ve gathered to create a final, cohesive piece.

See Related Article: How To Choreograph Your First Piece In 6 Simple Steps

Musicality In FreestyleFreestyling is like taking a test.You’ve done your homework and did a bunch of practice problems (familiarizing yourself with songs/rhythms and drilling movements/technique), and then you apply what you’ve learned from the different songs on the fly.

See Related Article: 5 Dance Tips To Begin Your Freestyle Foundation

Now let's train your musicality so you can become better at both choreographing and freestyling!

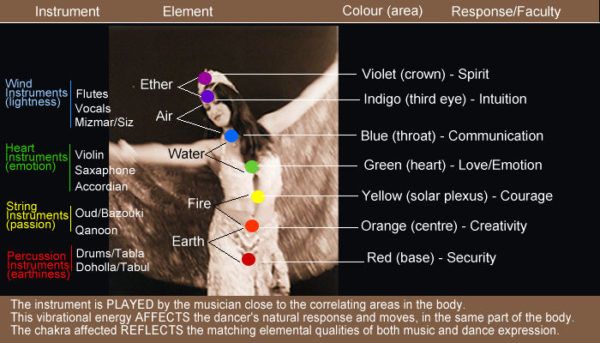

Step 1: Understand The Different Elements Of The SongA song is like a puzzle.You want to break it down and understand each part of the piece. Listen to the song several times and break down and isolate a different instrument or voice that’s contributing to the song. Some are blaringly obvious, like the vocals or the basic four-on-the-floor drum beat, but what makes the songs really interesting are the things that are harder to catch.

For example, syncopated rhythms are really fun to listen to, but they’re pretty complicated to understand. When I get to a syncopated rhythm, sometimes I have to stop and really pick it apart to be able to just be able to sing it back. And even then, I still struggle with being able to count a syncopated rhythm.

See Related Article: How To Dance Quickly To Slow Songs with Paul Ross (Cookies)

We also tend to focus on more of the obvious, so some sounds will be tucked in the song, but when you discover that dope, new sound in a song, it’s like finding gold. We’ve all had that “AH-HAH” moment in class where we FINALLY hear what the choreographer was trying to hit.

See Related Article: 24 Pleasures Only Dancers Would Know

As you start to understand the song better, you can start fitting the pieces together and see how they relate to one another. This allows you to pick and choose what you want to show through your dancing.

This allows you to pick and choose what you want to show through your dancing.

Now that you’ve isolated the elements in a song, you want to understand how they sound. Each layer of a song has different ways of being expressed. If you have a musical background, this may come easier for you since you understand that there are markings in the music that tells you exactly how to play the notes. When it comes to developing musicality, you’re doing the opposite. You’re extracting the quality of the sound out of what’s being played. A clear example of this is when you listen to the lyrics of the song.

See Related Article: How To Make Your Moves Match Vocals, with Markus Pe Benito (GRV)

Some syllables will be short and quick, and some will be dragged out longer. Sometimes, the pitch will be higher or lower and alternate in between. As a dancer, you want your movement to emulate the sound. Short quick syllables can be translated to sharp, quick motions. Lower pitches may make you want to hit a lower level. A more nuanced example is being able to hear the qualities of drum instruments.

As a dancer, you want your movement to emulate the sound. Short quick syllables can be translated to sharp, quick motions. Lower pitches may make you want to hit a lower level. A more nuanced example is being able to hear the qualities of drum instruments.

A snare is not always a quick, sharp sound – there is a space that the reverb fills afterwards. So a snare could be interpreted as a stick, rebound, or release depending on how you hear it.This goes for pretty much all instruments.The closer you listen, the more it will make sense.As you listen to music, your mind/body will create an image of the song to what you’re listening to through your ability to execute and dance vocabulary.

See Related Article: The Ultimate Guide To Execution Of Movement For Beginner Dancers

Step 3: Understand How You (Or Others) Perceive The MusicEach dancer has their own unique understanding of music. Now that you’ve picked apart the music and understand how the different voices in the song sound, you can pick and choose what you want to display. I tend to choreograph to mostly lyrics because I imagine myself being in the mind of the musician, but I also mix and match between beats and rhythm, too. And the best part about perception, is what you find interesting in a song will be completely different from what another dancer finds interesting in a song (try comparing different choreo to the same song).

I tend to choreograph to mostly lyrics because I imagine myself being in the mind of the musician, but I also mix and match between beats and rhythm, too. And the best part about perception, is what you find interesting in a song will be completely different from what another dancer finds interesting in a song (try comparing different choreo to the same song).

Even when doing the same exact piece, you'll see differences in how dancers perceive music. Though the timing and the frame of movements will be the same, the way they hit certain moves, soften some out more, or sit in others longer makes them who they are as a dancer.T ry thinking of ways to alter your understanding of a song. Maybe you always focus on the lyrics but there’s some dope beats going on in the back. Maybe instead of making a move for every single syllable, you can choose to move slowly and controlled through some lyrics instead.

Another great way to develop your own musicality is to study that of others. The greatest dancers out there have SUCH ridiculous and unique musicality.

The greatest dancers out there have SUCH ridiculous and unique musicality.

Study how a choreographer or dancer what he hears and try to understand how they hear it, then try to incorporate what you learn into your own repertoire. It's awesome watching dope dancers in class during groups and thinking, “Whoa I did not hear the song like that at ALL”.As you train your musicality, you can begin to train the way in which you approach a song when you choreograph or freestyle to it, and make a song your own.It will eventually become second nature.

It will become ingrained into who you are as a dancer, and with the skills and execution to match, you can showcase who you are as a dancer more definitively. Remember, without a deep understanding of music, you're just doing moves. Add layers, add complexity, and add your character!Follow along this textures drill to practice dancing to different sounds!

Do you have little tricks of the trade to build your musicality? Share it with us by commenting below! Get to know great choreographers' musicality in a STEEZY Studio class. They break down each sound and move so you can get really learn how they hear/dance a song.

Related Articles:

How to Track Your Progress as a Dancer

5 Tips To Start Your Freestyle Dance Foundation

How to Tune In and Develop Your Artistic Voice

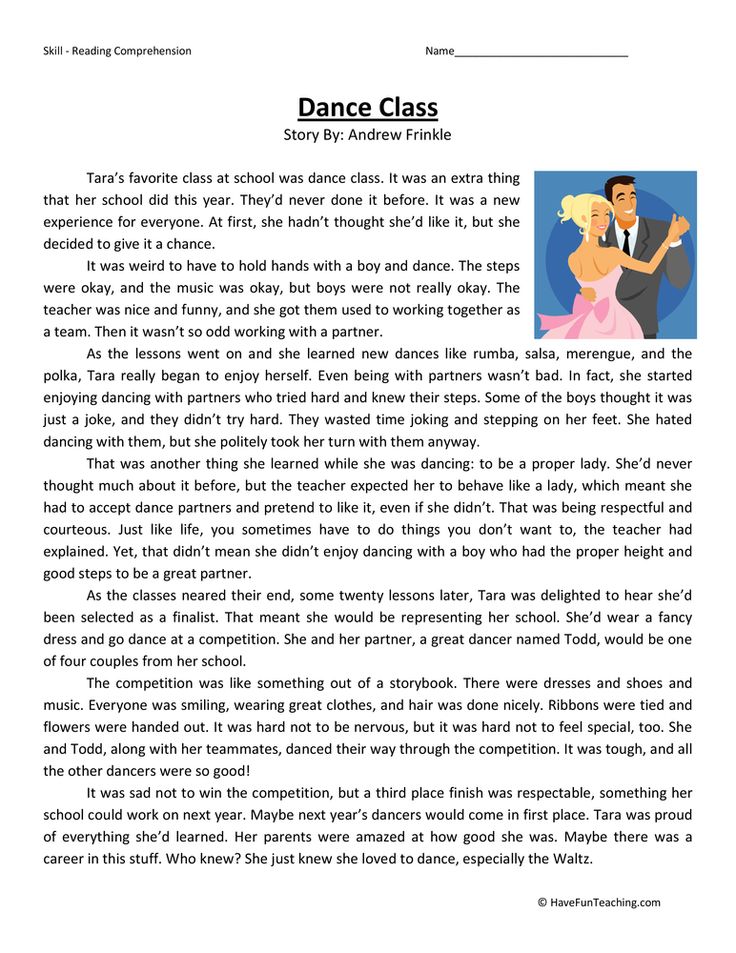

Ask a hundred people what musicality is, and you’re likely to get a hundred different answers. “Musicality is where an artist’s personality shines brightest,” says Smuin Contemporary Ballet member Ben Needham-Wood. For American Ballet Theatre soloist Skylar Brandt, “it’s what distinguishes one dancer from another. It helps me express myself more vividly and emotionally.”

Teachers encourage it, directors seek it out and dancers who possess it bring choreography to life in compelling ways. But what exactly is musicality, and how can dancers get more of it?

But what exactly is musicality, and how can dancers get more of it?

Putting Musicality Into Words

David Morse rehearses one of his ballets at Cincinnati Ballet. Jennifer Denham, Courtesy Cincinnati BalletMusicality could be loosely described as a dancer’s unique emotional and intellectual relationship to a piece of music, as expressed in their execution of choreography. “I connect musicality to rhythm, phrasing, tonality and mood—all these elements that allow the body to inhabit music from the inside out,” says Atlanta Ballet choreographer in residence Claudia Schreier.

Comparing two dancers in the same role can help make it clearer, says David Morse, a Cincinnati Ballet soloist, choreographer and class accompanist. He cites Royal Ballet principals Natalia Osipova and Marianela Nuñez in the Black Swan variation as a good example. “Natalia has this punch behind everything,” he says. “When she goes from Point A to Point B, there’s power on the front end and then a suspend. With Marianela, there is an airiness in arriving at the next position, more like a sustain across the beat. They could not be more different, in large part due to those small increases and decreases in speed.”

With Marianela, there is an airiness in arriving at the next position, more like a sustain across the beat. They could not be more different, in large part due to those small increases and decreases in speed.”

Claudia Schreier rehearses her ballet Passage with Dance Theatre of Harlem. Rachel Neville, Courtesy Schreier

Most of those choices are made in rehearsal, but sometimes they reflect a dancer’s spontaneity. Miami City Ballet principal soloist Lauren Fadeley remembers feeling caught off guard when MCB’s orchestra played unexpectedly slowly during Balanchine’s La Valse. “But our rehearsal pianist came up to me afterward and said, ‘That was one of the most musical performances of that ballet I’ve ever seen,'” says Fadeley. “You have to listen to the music and just dance. And enjoy it—that’s what will really shine through.”

These examples demonstrate a deeply personal element that each dancer can find within themselves. “The dancers we look up to are the ones who bring their true selves to every step through their musicality,” says Schreier. “What we really get drawn to is that freedom. And that comes from exploring their relationship to the music and falling in love with it in their own way.”

“What we really get drawn to is that freedom. And that comes from exploring their relationship to the music and falling in love with it in their own way.”

The Building Blocks

Ben Needham-Wood and Terez Dean in Amy Seiwert’s Renaissance. Chris Hardy, Courtesy Smuin Ballet

Paradoxically, dancers reach that level of musical freedom through deliberate, dedicated practice. “It has to start from barre,” says Brandt, who describes herself as “rigid” about doing combinations at the ballet master’s prescribed tempos because “it trains your body to handle the demands of a faster dégagé than you’re used to, or a slower adagio, when you get onstage.” Having so much command over her musicality, she says, “makes me feel like I can get lost in what I’m doing—like I can be an embodiment of the music, versus the music being a separate entity.” On the other hand, deliberately playing with the rhythms and patterns at barre can lead to equally important insights, says Brandt.

A basic understanding of music can be an inroad into greater self-expression. Fadeley, for instance, grew up playing piano and flute. Her ability to read music and quickly grasp time signatures has been critical to mastering the Balanchine oeuvre. “You can have a Stravinsky score that is so hard to count—there’s a 13 and a 9 and an 11,” she says, referring to the complex time signatures found in many Balanchine works. “Even in the ‘Waltz of the Snowflakes’ in The Nutcracker, there’s a part where we would count a 12 or a 13 after counting 8s.”

Take advantage of free online resources, like MusicTheory.net, Signals Music Studio’s YouTube demos and WikiHow.com’s section on reading music, to familiarize yourself with time signatures, concepts like tempo and phrasing, and forms like sonata and minuet. Along with entry points into the score a choreographer has chosen, that understanding can provide anchors for your interpretation of their choreography. “You might have your counts on 1 and 2 and 3,” says Needham-Wood, “but how you play with all those little ‘ands’ is how your musicality comes out. ”

”

As empowering as those building blocks are, the most compelling artists infuse their musical knowledge and technical mastery with something innate and, yes, undefinable. “When musicality is really in your body, you’re not thinking about it. It just happens because you are letting yourself move,” says Schreier.

Be Your Own Maestro

Lauren Fadeley and Chase Swatosh in Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments. Alexander Iziliaev, Courtesy MCB

Dancing at home is ideal for exploring your own sense of musicality and artistic voice, because you can turn off the Zoom camera and take some risks, free of any feedback but your own sense of what feels authentic. “This is not about proving anything to anyone. This is about taking an opportunity to discover what you’re able to do,” says Needham-Wood.

Ready to get started? These exercises can help you discover insights and artistry that you’ll bring back to the studio and the stage.

Reorchestrate the barre:

Barre is a great place to experiment with your musicality, says Brandt. “Play with your phrasing, play with your accent. Hold your fifth position a millisecond longer than you would have. Really differentiate your tendus that are accent out from tendus that are accent in. We should all be doing that anyway, so that by the time we arrive at rehearsal or a performance, we have musicality in our bodies.”

Push the boundaries:

“Make up a piece of choreography, and dance it to the same music three times,” says Schreier. “Try to do it exactly on the music, then just behind the music, and then just ahead. How does that change your physicality? How does it change your relationship to the music? Which one feels best for you? What can you pull out of the silences?”

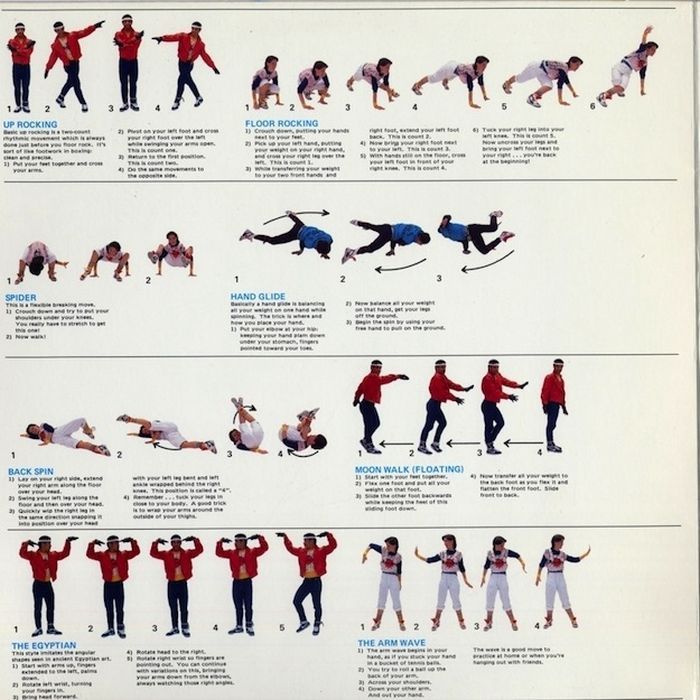

Bust a new move:

“If you only expose yourself to one approach to musicality, you’re limiting your potential to express yourself,” says Needham-Wood, who also teaches hip hop. Try tap, Broadway, or popping and locking. “Ballet is often about the melody, while contemporary brings in more percussive sound, and hip hop has a sense of weight to it. The more you allow yourself to get outside of your comfort zone, the more your comfort zone will grow.”

Try tap, Broadway, or popping and locking. “Ballet is often about the melody, while contemporary brings in more percussive sound, and hip hop has a sense of weight to it. The more you allow yourself to get outside of your comfort zone, the more your comfort zone will grow.”

Experiment with time signatures:

A time signature is a notation used in Western music to indicate the number of rhythmic beats in a measure of music—the ones most familiar to dancers are 4/4 (think of the steady 1-2-3-4 of tendus en croix) and 3/4, which is waltz time. Composers use time signatures to create effects in their music, from strident tension to a cascading sense of joy—if you’re dancing to agitated music by Stravinsky, for example, you might encounter 3/32, 4/16, 11/4, while in a pop ballet set to the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” you’ll find 11/8, 4/4 and 7/8.

A great way to build a sense of time signatures is to experience them for yourself. ABT principal conductor Charles Barker suggests listening to the nationalistic dances in Sleeping Beauty or Swan Lake, and hearing the time signatures of the mazurka, polonaise and waltz. “Listen to it, then move to it and feel how all the phrases are not all the same tempo.” Try the third movement of Brahms’ Symphony No. 3, which is in 3/8 time, or the second movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6, in 5/4. “Tchaikovsky has lots of music in 5/4. Play with it! He was playing with it, so we should as well.”

“Listen to it, then move to it and feel how all the phrases are not all the same tempo.” Try the third movement of Brahms’ Symphony No. 3, which is in 3/8 time, or the second movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6, in 5/4. “Tchaikovsky has lots of music in 5/4. Play with it! He was playing with it, so we should as well.”

Plastic and dance: how to learn?

Dance is an art, and two components make it beautiful: plasticity and musicality (although for sports dances, another criterion of technicality is added). The first relates to working with your own body, and the second - with music, and they work only as a set. If you remove at least some element, the dance will not look harmonious, but will turn into ordinary movements with music playing in the background. We definitely do not need such an effect, and therefore special attention should be paid to these points. It is worth talking about musicality directly when listening to music and using examples, but for now let's focus on plastic.

What is plastic surgery?

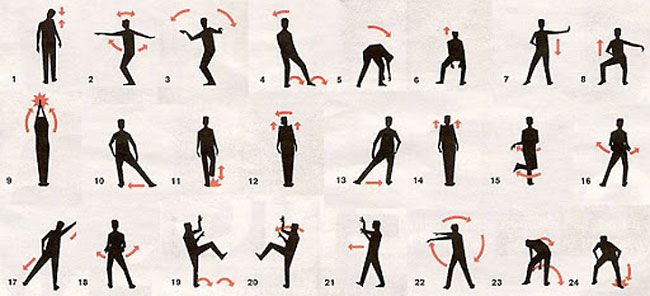

Body plasticity refers to better control of its various parts. Here the following points play a key role:

- "isolation" of individual points or parts of the body. By isolating one muscle from another, you will be able to perform the movement only with them, without using unnecessary parts of the body. For example, turn your head without turning your torso or work with your arms, shoulders with a static body;

- coordination as the ability to control several such points or parts of the body at the same time. When, for example, the legs take steps, the back remains straight, and the arms play their part.

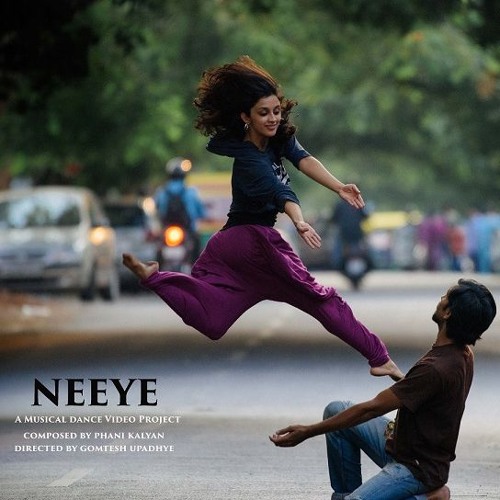

Plastic movements look much more advantageous. An element of the same complexity will look different for a plastic and a beginner dancer. From dances, plastic moves into ordinary life and is manifested by a graceful gait, confident movements and the ability to present oneself.

Developing plasticity

It is not possible to improve the plasticity of the body in theory - this can only be done in practice. Most of all, plasticity is needed in dancing, they are also best suited for its development. For example, Exotic Pole as one of the directions of pole dancing, focused specifically on plasticity, develops femininity (or, conversely, masculinity) and grace.

Most of all, plasticity is needed in dancing, they are also best suited for its development. For example, Exotic Pole as one of the directions of pole dancing, focused specifically on plasticity, develops femininity (or, conversely, masculinity) and grace.

The dance elements and training exercises here are selected in such a way that when they are performed, the plasticity of the body improves. Even if it will be difficult to complete them the first time, repeated repetitions with the exact implementation of the trainer's recommendations will lead to the desired result. No need to be lazy and do full leg, avoid exercises that cause discomfort. Only by leaving the comfort zone, one can improve and improve natural plasticity. If you leave training for a long time, the result may worsen again.

In addition to full-fledged dance training, some simple tricks help develop plasticity:

- watch videos of professional dancers, notice how they move, and try to repeat;

- do stretching - it does not guarantee plasticity, but helps to improve it;

- film yourself on video and look as if from the side.

Pay attention to what you would like to improve, dance again, shoot - and so on in a circle;

Pay attention to what you would like to improve, dance again, shoot - and so on in a circle; - work on a mirror, notice how the reflection changes depending on your work. When you see a picture that you like, concentrate on the sensations at that moment, remember them and try to repeat blindly;

- train your muscles and bring the mastered elements to automatism. Then there will be time to think about plasticity, and not about simply not forgetting any figure;

- work on yourself to remove excess tension from the muscles. Tense muscles are clamped, fettered and cease to be plastic.

And most importantly, enjoy what you do. Immerse yourself in music, create images for yourself, follow the impulses of the body and relax.

Connection (dance) - frwiki.wiki

For articles of the same name, see Connection.

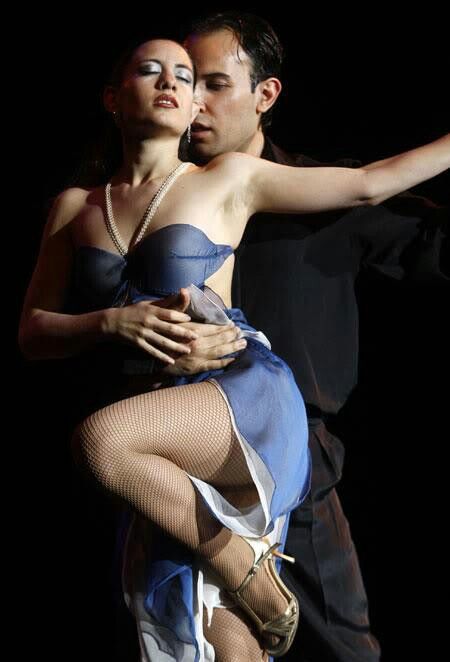

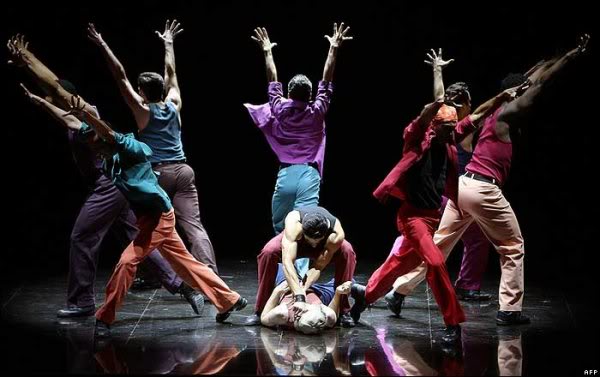

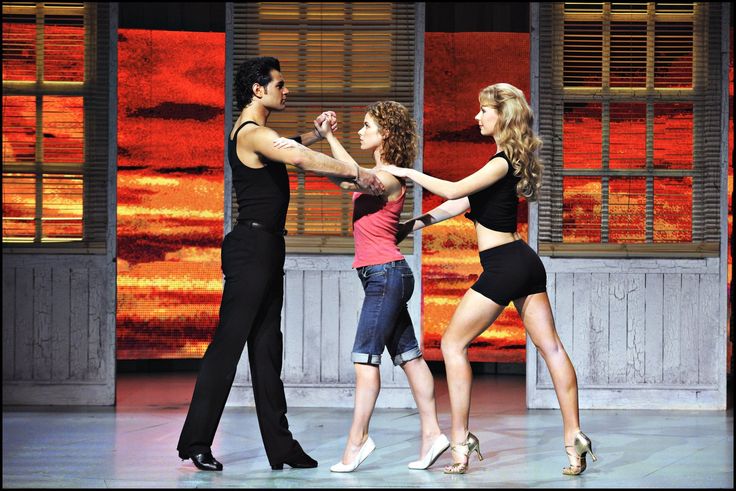

Two dancers connected with their bodies.

In partner dance , the link is a form of physical communication used by dancers to facilitate the synchronization of their dance moves. The connection in the dance is the feel of the dancers, not the appearance. One dancer guides another dancer's movements with non-verbal instructions transmitted through the physical connection between the dancers. It is an important technique in many partner dances, especially dances with significant physical contact between the dancers, such as Argentine tango, Lindy Hop, West Coast Swing and English Waltz, for example. The term "connection" also has a second meaning in dance, which is different from the first, but related to it. It is sometimes used to describe points of physical contact between the bodies of dancers, an aspect closely related to the dance setting.

The connection in the dance is the feel of the dancers, not the appearance. One dancer guides another dancer's movements with non-verbal instructions transmitted through the physical connection between the dancers. It is an important technique in many partner dances, especially dances with significant physical contact between the dancers, such as Argentine tango, Lindy Hop, West Coast Swing and English Waltz, for example. The term "connection" also has a second meaning in dance, which is different from the first, but related to it. It is sometimes used to describe points of physical contact between the bodies of dancers, an aspect closely related to the dance setting.

CV

- 1 Terminology

- 2 Guidance and suivage ( lead and follow )

- 2.1 Description

- 2.2 Synchronization (or lack thereof)

- 3 Connection purposes

- 3.1 Communication of information

- 3.2 Power transmission

- 4 connection types

- 4.

1 Physical connection

1 Physical connection - 4.1.1 At physical contact with the body (other than hands)

- 4.1.2 Without physical contact with the body (but only through the hands)

- 4.2 Non-physical connection

- 4.2.1 Visual and verbal communication

- 4.2.2 Psychological connection

- 4.3 Musicality

- 4.

- 5 Connectivity technology

- 5.1 Communication without physical contact with the body (but only through the hands)

- 5.2 Communication with physical contact with the body (other than hands)

- 6 See also

- 7 Notes and references

- 8 External links

Terminology

Initially, the dancing couple consisted of a man and a woman. The man led the dance and the woman followed her partner. This structure is still the most common today, but there are now more same-sex or opposite role-playing couples, both at social events and in competition. To designate these two roles , avoiding gender differences, we now use the terms leader and follower (or follower ), borrowed from English. The terms rider / horsewoman or male / female , which are sometimes only used to describe women leading or following men, as well as the terms mentor / guide , leader / leader and follower / follower" will not be used in this article because they make text heavier. by their genre, and the meaning of dancer is sometimes missing from their definitions. Thus, in order to maintain a uniform, concise and inclusive notation, in this article the names " leader" or " leader" refer to the dancer, leader couple, regardless of gender and gender, and the names " follower" or " attendant" denotes a dancer. follows his partner while dancing. These terms are already in use in the French-speaking dance community. Terms « guide" and " follow-up" will be used to indicate activities corresponding to the roles of the two partners.

To designate these two roles , avoiding gender differences, we now use the terms leader and follower (or follower ), borrowed from English. The terms rider / horsewoman or male / female , which are sometimes only used to describe women leading or following men, as well as the terms mentor / guide , leader / leader and follower / follower" will not be used in this article because they make text heavier. by their genre, and the meaning of dancer is sometimes missing from their definitions. Thus, in order to maintain a uniform, concise and inclusive notation, in this article the names " leader" or " leader" refer to the dancer, leader couple, regardless of gender and gender, and the names " follower" or " attendant" denotes a dancer. follows his partner while dancing. These terms are already in use in the French-speaking dance community. Terms « guide" and " follow-up" will be used to indicate activities corresponding to the roles of the two partners.

Guidance and suivage (

lead and follow )In most partner dances, one of the two partners leads the movements of the couple, and the other partner. This concept, called in English lead and follow ( lit. Guide and suivage ), allows to develop a couple on the dance floor and perform various drawings and assists at the same time.

Description

Leading and following is done through the connection between the dancers and their staff. The frame allows the leader to move the body of the transfer to the follower and gives the follower improvisation or styling support. A frame is a stable structural combination of two bodies held through the arms and/or legs of the dancers.

Synchronization (or lack thereof)

In many types of partner dances, the tension and compression of the lead through the connection are not signals for immediate future movements. Dancers don't always move at the same time. There is a slight time delay between leader indication and follower response . Follower must not move before leader has initiated his movement. Until the leader begins to move, the dancers must maintain their connection pressure without moving the involved body parts.

There is a slight time delay between leader indication and follower response . Follower must not move before leader has initiated his movement. Until the leader begins to move, the dancers must maintain their connection pressure without moving the involved body parts.

Connection purposes

The connection can be used to transmit power and energy as well as information and signals. Some dances (and some dancers) emphasize power or signals, but most use a combination of the two.

Transfer of information

One of the purposes of the connection is to provide information transfer between dancers. For example, leader can tell his partner what steps or figure he wants her to do. Through the connection, the dancers will also indicate to their partner their level of dancing, whether consciously or not. This may, for example, allow experienced dancers to tailor their efforts and expectations to their partner. An experienced dancer may lower his expectations or the energy of his movements if he dances with a beginner partner, or he will redouble his efforts and try to go beyond his limits if he dances with a partner of the same or higher level.

An experienced dancer may lower his expectations or the energy of his movements if he dances with a beginner partner, or he will redouble his efforts and try to go beyond his limits if he dances with a partner of the same or higher level.

In some dances, such as in Latin-style ballroom dancing (rumba, cha-cha-cha, samba, etc.), tensions and bonds of connection are mainly used to indicate an approaching figure. The dancers keep their structure, and, as a rule, the leader points to the follower at the figures by short-term tension and contraction, without exerting much effort.

Energy transfer

In dances such as West Coast Swing and some styles of Lindy Hop, communication is still used to transfer information between partners, but energy transfer is more important and tensions and contractions can be much stronger and maintained for many times. . . Sometimes the tension can become very strong, even if you do not start moving. These energy transfers are especially important in sudden changes of direction and dances that contain a lot of energy.

Connection types

Two dancers in a closed position with close skin contact.

Physical connection

The most commonly used term connection, in dance, refers to this type of connection, the physical connection. This type of connection can be divided into two subtypes, differing in the position of the dancers and in the contacting parts of the body.

At physical contact with the body (other than hands)

In the closed position (closed frame) in contact with the body, the connection is established by holding the frame. Dancers are not in contact with a limb, but with another part of their body. This type of connection is used, for example, in all standard international ballroom dancing.

When a frame is created, voltage is the primary means of establishing communication. In this type of connection the leader guides his partner mainly by moving his torso and very little or not at all with his arms. Tension changes are made to create variations in the rhythm of figures and movements, and these are transmitted through points of contact. At the follower moves to follow the leader , maintaining the pressure between the bodies as well as the position of its body.

Tension changes are made to create variations in the rhythm of figures and movements, and these are transmitted through points of contact. At the follower moves to follow the leader , maintaining the pressure between the bodies as well as the position of its body.

In standard ballroom dancing, dancers in this position tend to dance as if the couple had only one body. Contact is so close that 9The 0058 follower of can almost instantly respond to their partner's movements, contributing to the illusion that the two partners are moving as one body.

Without physical contact with the body (but only through the hands)

In an open position (open frame) or a closed connection without contact with the body, the arms and hands themselves provide a connection that can be in tension, compression or in a neutral position.

- the dancers move away from the partner and apply a force equal to the force of the latter and opposite to it.

The arms are not the only source of this strength: they are often assisted by tension in the muscles of the torso through body mass or momentum.

The arms are not the only source of this strength: they are often assisted by tension in the muscles of the torso through body mass or momentum. - At squeeze the dancers push each other.

- In the neutral position, the hands do not exert more force than is required to hold the hand.

The connection between the dancers' hands must be clear and allow for a quick change of direction while remaining continuous and avoiding jerks. Dancers must keep their hands in balance between hardness and softness.

Non-physical connection

Visual and verbal communication

Other forms of communication, such as visual or verbal cues, can sometimes help connect with a partner. However, these alternatives are only used in special situations, such as during training or when the dance figures are intentionally dancing apart (with no physical contact at all).

Psychic connection

Because dancers are human, psychological and sociological aspects come into play between dance partners. Good dancers empathize with their partner to enhance their experience. A sensitive connection can come from of a leader with clear and convenient guidance, from a conciliatory or compassionate follower of , or from a benevolent smile in response to a mistake. Ideally, communication is a dialogue: the leader remains aware of the follower's choice of interpretation and innovation, as well as the rigidity of the physical connection. The two dancers adapt to each other and constantly adjust their movements to keep the couple in harmony. Research has also shown that dance strengthens social bonds, in part through the synchronicity of the dancers' movements, and may also be used in some therapies.

Good dancers empathize with their partner to enhance their experience. A sensitive connection can come from of a leader with clear and convenient guidance, from a conciliatory or compassionate follower of , or from a benevolent smile in response to a mistake. Ideally, communication is a dialogue: the leader remains aware of the follower's choice of interpretation and innovation, as well as the rigidity of the physical connection. The two dancers adapt to each other and constantly adjust their movements to keep the couple in harmony. Research has also shown that dance strengthens social bonds, in part through the synchronicity of the dancers' movements, and may also be used in some therapies.

Musicality

“A technical dancer without musicality will be like a painting without color. To choose, I prefer to look at a dancer-musician, but not very flexible and with less beautiful legs. "

- Lorena Feijoo, soloist

In the context of dance, musicality is the ability to listen, perform and dance to music. The music can influence the actions of the dancers to some extent. In mastering both dancers, the notion of musicality can also be seen as a form of mental connection between partners, but the guiding and therefore physical connection also plays an important role.

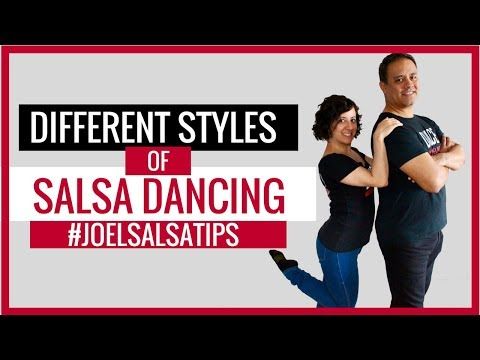

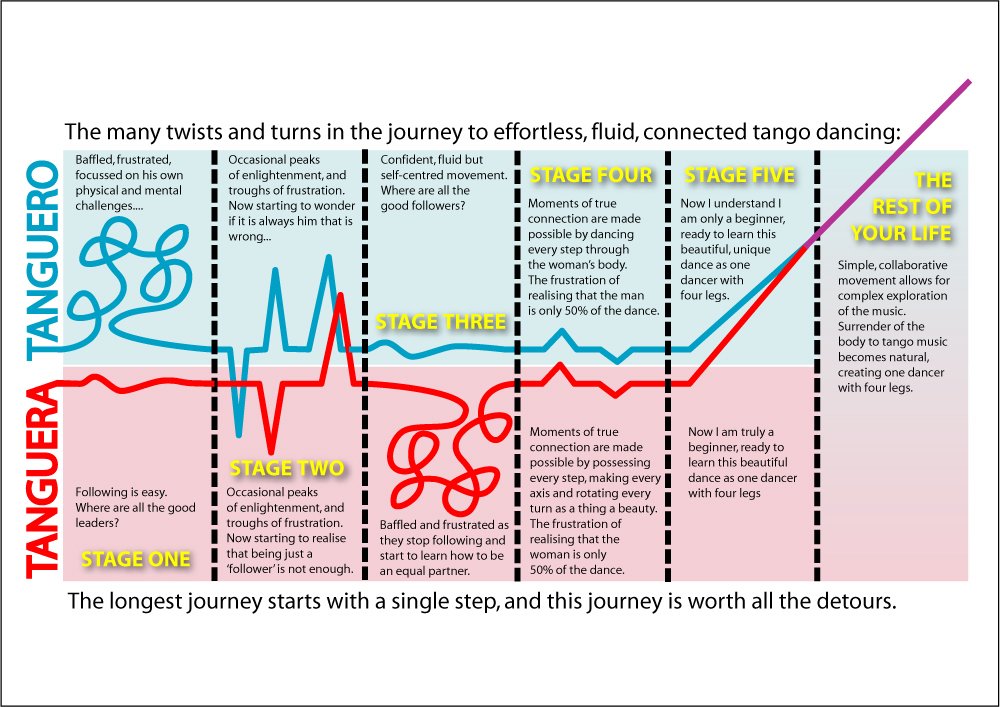

Musicality is more important in dances in which different figures often have different durations (here referred to as asymmetric ), such as swing dances (west coast swing, rock, etc.) or discofox. These dances differ from dances in which most figures are danced on the same number of beats as the musical phrase (here called symmetrical dances), often eight beats long, such as salsa and dance dances. standard sports. sit back.

The basis of a dancer's musicality, applicable to both symmetrical and asymmetrical dances, is the ability to stay in the rhythm of the music. Each dancer must be able to carry the weight of his body to the rhythm of the music and the conventions of his dance. This requires the ability to consciously or unconsciously feel the rhythm of the music. For the leader of , the ability to count beats is important in order to be able to direct the figures in rhythm and start the dance itself. More advanced musical skills, more important in asymmetrical dances, are, for example, the ability to adapt one's movements to the music by adapting the figures or the rhythm of one's steps, the ability to align one's figures with musical phrases, or the ability to mark key elements of music such as breaks or jumpers with style changes or short breaks.

For the leader of , the ability to count beats is important in order to be able to direct the figures in rhythm and start the dance itself. More advanced musical skills, more important in asymmetrical dances, are, for example, the ability to adapt one's movements to the music by adapting the figures or the rhythm of one's steps, the ability to align one's figures with musical phrases, or the ability to mark key elements of music such as breaks or jumpers with style changes or short breaks.

Connection Technique

Communication, like many concepts in dance, can be learned and improved with practice and experience. A good connection often requires a good structure, since the latter provides a medium through which a good connection can be established.

Communication

without physical contact with the body (but only through the hands) The general rule for open connections is that the movement of the arms of the leader to the left, right, forward or backward is the movement of the whole body. So for follower the movement of the bound hand is immediately transformed into the corresponding movement of the body. This effect is achieved by stretching and tensing the muscles and locking the hands, but this is uncomfortable and wrong. Such tension removes thin elements of the connection and prevents the free movement up or down necessary to perform many turns and turns.

So for follower the movement of the bound hand is immediately transformed into the corresponding movement of the body. This effect is achieved by stretching and tensing the muscles and locking the hands, but this is uncomfortable and wrong. Such tension removes thin elements of the connection and prevents the free movement up or down necessary to perform many turns and turns.

Instead of strengthening the arms, the connection is made with the muscles of the shoulder, upper body and torso. Movements are made from the center of the body (in English core ). Leader behaves by moving while maintaining the frame and connection. Different dance forms and different movements in each dance may require different types of connection. In some dances, the distance between the dancers remains more or less constant. In others, such as West Coast Swing, closing and pulling are fundamental to the dance and require flexion and extension of the arms, alternating contraction and tension. The feeling of connection between partners is different in each dance and with each partner. Good social dancers adjust to dance traditions and the reactions of their partners.

The feeling of connection between partners is different in each dance and with each partner. Good social dancers adjust to dance traditions and the reactions of their partners.

A good connection is neither too tight nor too soft. The connection should be easy and comfortable with minimal physical contact. Dancers touch with the palm of their hand or only with their fingertips, for example, hooking their fingers on a hook. The pressure exerted by the two dancers must be equal and constant. The follower of must not cling to the leader of because the latter must be able to change the connection at any time. Leader should adapt his indication in Followers of responses and guidance explicitly without forcing movement.

Communication

with physical contact with the body (other than hands) When the dancers are in contact with the torso, as in standard ballroom dancing, the connection is very different from the connection in the open position. In this position, the dancers are in contact with the right side of their body from the hips to the middle of the torso. This close bodily contact is necessary. In this situation, 9The 0058 leader is still leading from the core since it is in the open position, but the information is transmitted directly to the follower stem without passing through the shoulders, arms and hands. Guidance is no longer done by hand. The two dancers must give the impression of moving as one body. To avoid separation, the two dancers push each other slightly to keep the contraction. This means that the dancer moving backwards must hold the other dancer, they must back off while holding the weight forward. This close connection is also important for performing fast simultaneous movements such as quickstep jumps or quick turns in the Viennese waltz. In the English waltz, the dancers must perform a wave-like movement along a vertical axis together.

In this position, the dancers are in contact with the right side of their body from the hips to the middle of the torso. This close bodily contact is necessary. In this situation, 9The 0058 leader is still leading from the core since it is in the open position, but the information is transmitted directly to the follower stem without passing through the shoulders, arms and hands. Guidance is no longer done by hand. The two dancers must give the impression of moving as one body. To avoid separation, the two dancers push each other slightly to keep the contraction. This means that the dancer moving backwards must hold the other dancer, they must back off while holding the weight forward. This close connection is also important for performing fast simultaneous movements such as quickstep jumps or quick turns in the Viennese waltz. In the English waltz, the dancers must perform a wave-like movement along a vertical axis together.

For some dancers, the need for close physical contact can be unbearable or overwhelming. It is possible to dance dances that should have close contact without touching your body, but the dance is not technically performed correctly. It becomes less regular, less fluid, and some shapes become much more complex. Lack of body contact is also common among beginner dancers who do not always recognize its importance or have developed the habit of controlling their hands.

It is possible to dance dances that should have close contact without touching your body, but the dance is not technically performed correctly. It becomes less regular, less fluid, and some shapes become much more complex. Lack of body contact is also common among beginner dancers who do not always recognize its importance or have developed the habit of controlling their hands.

See also

- Frame

- Dance

Notes and links

- (fr) This article is taken in whole or in part from the English Wikipedia article titled "Communication (dance)" (see list of authors) .

- ↑ (in) " Dance Dictionary " on BallroomDancers.com (accessed October 15, 2020)

- ↑ a b and c (in) Richard Powers, " Connection ", at socialdance.

stanford.edu (accessed 15 October 2020)

stanford.edu (accessed 15 October 2020) - ↑ (in) Patty Wells " Dance Connection for Partner Dancing " on dancetime.com (accessed November 24, 2020)

- ↑ (c) " BYU Allows Same-Sex Couples in Ballroom National Competition " ["BYU Allows Same-Sex Couples in National Ballroom Dance Competition"], at universe.byu.edu (accessed October 6, 2020)

- ↑ a and b " 10 terms of the world of dance ", on partner-danse.fr (accessed 30 October 2020)

- ↑ " What to follow and what to lead? ", Available at Shouldweswinglyon.com (accessed 3 November 2020)

- ↑ Valeria De Luca, Semiotic Universes of Dance: Forms and Meaning Journey in Argentine Tango (PhD Thesis in Language Sciences/Semiotics), University of Limoges, (read online) , pages 211

- ↑ " Definition: rider, rider ", on larousse.

fr (accessed 3 November 2020)

fr (accessed 3 November 2020) - ↑ " Le Jive ", on lpa.be (accessed 30 October 2020)

- ↑ " jivestudio.com ", on jivestudio.com (accessed October 30, 2020)

- ↑ " La Belle Blues Paris ", on labelleblues.com (as of October 30, 2020)

- ↑ " Definition: Tracking ", on cnrtl.fr (accessed 3 November 2020)

- ↑ a and b (en) F. Matzdorf and R. Sen, " Demanding Followers, Strong Leaders: Dance as an 'Incarnate Metaphor' for the Leader-Follower Ship", Organizational Aesthetics , v. 5, p o 1, , pp.

114-130

114-130 - ↑ (in) Joseph Daniel DeMers, " Frame and Conformity .DELTA.P T ED: A Framework for Teaching Swing and Blues Partnerships ", Research in Dance Education , vol. 14, p o 1, , pp. 71-80 (DOI 10.1080 / 14647893.2012.688943)0363

- ↑ a b and c " Communication and guidance " on danserlerock.fr (accessed 22 October 2020)

- ↑ (in) Bronwyn Tarr, " Let's Dance: Synchronized Movement Helps Us Bread and Strengthen Friendships " on theconversation.

com, (accessed October 22, 2020)

com, (accessed October 22, 2020) - ↑ a and b " Musicality for dancers " on retroguidage.fr 9 (De) " Listening and dancing ", on west-coast-swing.net (accessed Nov 3, 2020)

- ↑ " Find the beginning of 32- multiples of sentences ", at aerobix.ccdmd.qc.ca (accessed October 22, 2020)

- ↑ (in) " Breaks " on west-coast-swing.net (accessed October 22, 2020)

- ↑ (in) " Ballroom Basics " ["Live Basics of Dance"] on thedancestoreonline.

com (accessed Nov 24, 2020)

com (accessed Nov 24, 2020) - ↑ (in) " Tips and Techniques: The Physics of Dance Communication " on dancestationusa.com, (accessed November 24, 2020)

External links

- " La Musicalité ", on temps-danse-asnieres.com (accessed 22 October 2020)

- Jean-Christophe Pare, " The dancer's musicality, the fragrance of the exceptional presence in the moment ", Repères, cahier de danse , vol. 20, , pp. 26-28 (DOI 10.3917 / reper.

020.0026, read online)

020.0026, read online) - (de) " Musikalität ", on west-coast-swing.net (accessed 22 October 2020)

- (en) Dan Radler, “ How Ballroom Dancing Competition 9 Is Scored0371", on ballroomdance.net (accessed October 22, 2020)

- (en) Harold and Meredith Sears, " Dance Position and Relationship Between Partners ", on rounddancing.net (accessed October 22, 2020)

- (en) “ How ballroom dancing can help you communicate ”, on fredastaire.