How to describe dancing in writing

How to write a Professional Dance Scene (Tips and Examples)

So you don’t know how to write a dance scene? The words to use, the actions to describe. It can be challenging. What’s too much? What’s too little?

This post will give eight tips on writing dance scenes in a screenplay that most people miss and give actual dance scene examples from scripts accompanied by the movie scene.

So you can write your next dance scene, whether that be:

- Slow dance

- Salsa dance

- Dancing in a club

- Lap dance

- Pole dance

- Breakdance

Let’s begin:

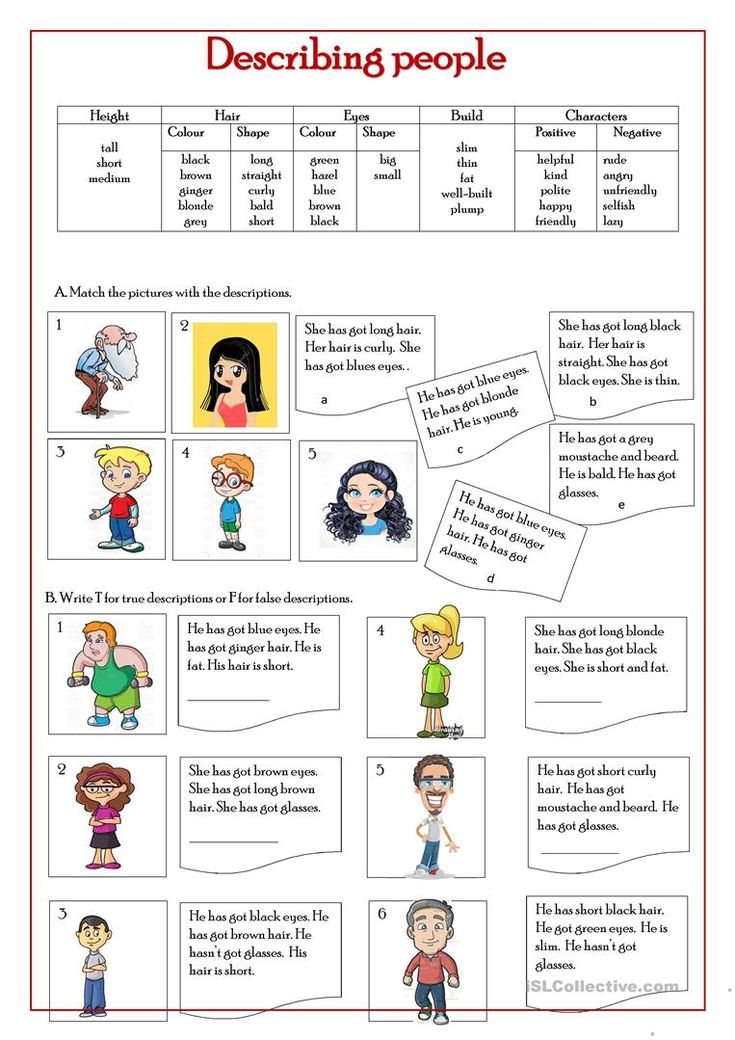

1.) Know the Dance Style and Tell the Reader

This first tip will break the show don’t tell rule, but in specific scenarios, it’s justified.

Name it.

Whether it’s a classical ballet dance or a tap dance.

Saying what type of dance we are about to read on the page is the best way to describe it. It doesn’t matter how you tell them as long as it’s in there.

Examples:

They enter a wonderland of hip-hop break dancers.

She laces up her ballerina shoes.

Announcer Next up to the pole, we call her...White Diamond.

It’s best towards the beginning, especially if the movie isn’t about a dancer and this is a one-off scene. You have to let the reader know what type of dance is happening.

Naming, the dance in the opening, helps the reader imagine what the setting looks like and how slow or fast the dance is happening.

If it’s in a nightclub, people will assume it’s fast-paced unless described differently. If it’s in a strip club, people will think it’s slow and sexual.

We will get in some great ways to describe it, but you must first understand, what you say is more important than how you say it.

2.) Dance scenes are written short

This tip always stops people in their tracks. But yes, dance scenes are written short and not that descriptive.

In my research, every single written dance scene is shorter than the actual movie version. Generally, for every one page in a script, it equals one minute on the screen. But for most scenes with motion, like dance scenes, action scenes, fight scenes.

Screenplays are just a blueprint for a film, so when writing, remember naming every twirl, flip, or spin isn’t just not needed it’s arguably considered bad writing.

How short are we talking?

I’ve read dance scenes that say

They dance

Yes, Hollywood produced screenplays.

Example:

Pulp Fiction ScreenplayPulp Fiction Dance SceneWhy?

The director will come up with what it looks like; it’s your job to come up with what it feels like. It’s your job to write the essential parts. Now that’s extreme, but it shows how minuscule this part of your script should be.

Example 2:

LALA Land ScreenplayLALA Land Opening SceneEven in a musical, The entire four-minute scene is written in half a page.

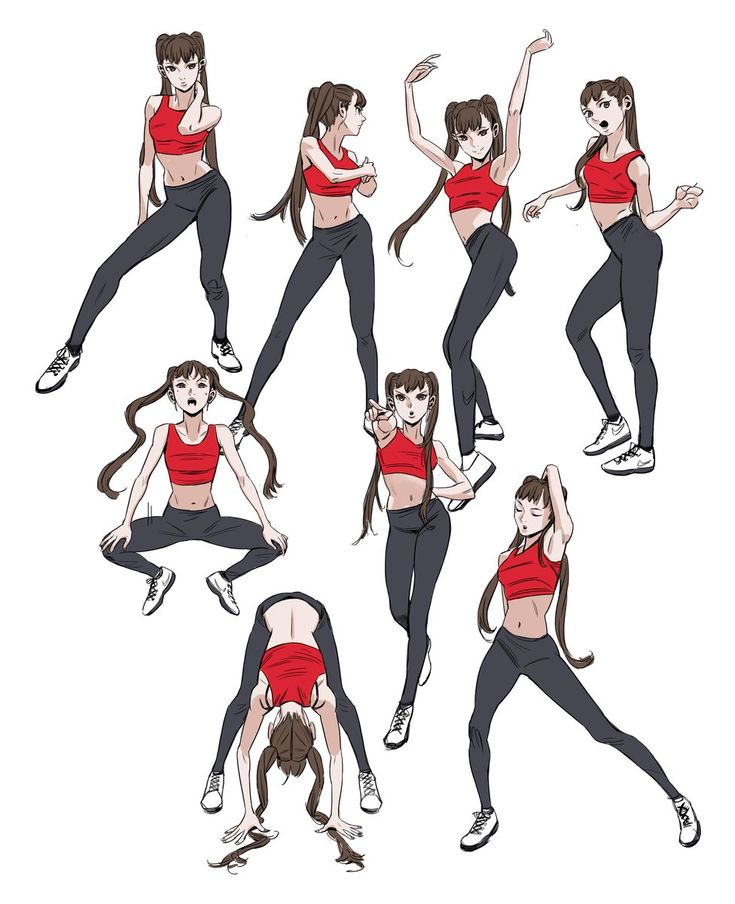

4.) Describe the Whole Emotion, not the Entire Dance

When writing a dance scene, you want to give a feeling. This feeling should reflect the tone at the moment.

The non verble comunication.

What are the expressions and emotions your character gives off while dancing? These words are far more valuable in a dance scene than the actual move itself.

Example:

There are no dance descriptions even written just about the emotion the protagonist is feeling.

But what dance moves do you describe? Keep reading.

3.) Only Describe the Essential Dance Moments

What is essential?

The broad strokes of a dance or the most crucial moment.

- The big move for the judges.

- The hardest part for the dancer to pull off.

- The moment of significantly heightened emotion.

If you watch movies, every dance scene has one. And if you read the screenplays, the writer usually writes only that part.

4.) Use Vivid Action Words

How do you describe dance in words? Don’t use dance terminology unless your writing about some Olympic or sporting event. Or if the term is being used in dialogue.

We can talk about what you don’t do because there aren’t firm rules on what you should do when it comes to creativity.

But generally use words that paint a picture. The image you give with your words is all that matters.

Example:

Don’t write this

She jumps

Write this

She leaps

or better yet

She floats in the air.

Think about it everyone jumps basketball players, kids on the playground. But “floating” paints a picture of grace I can see. It’s specific to a ballerina or contemporary dance.

Example 2:

Don’t write:

She dances with her hands up.

Write:

Her hands held rollercoaster high, raging to the beat of the drum.

I’m trying to describe dancing in a club or a Rave.

Since we are trying not to bore the reader with too many details, we have to paint an image with the words we know. Think what type of jump it was? Basic terms will not work when describing a dance. You have to think harder than that.

5.) Break Up More Extended Scenes with Dialogue

Dialogue is a great way to break up any action, including dance. It stops your dance scene from being two-wordy and keeps the reader engaged.

I think about the Mr. and misses smith dance scene. This scene is quite long, but what keeps it intresting is the antiques and wordplay from both assassins trying to get the upper hand during the dance.

Example:

Mr. and Mrs. Smith Dance Scene6.) Know the Steaks of the Dance SceneWho wins or loses.

Not purely speaking from a competition sense but ask yourself:

- What do we find out about the protagonist?

- What questions do we have after the scene?

The actions your character takes during the dance scene speak volumes.

Just like the Mr. and Mrs. Smith example above, we can tell by the conversation they don’t trust each other, but by the end, we find out that maybe in their marriage, real feelings were involved.

Find out the steaks of the scene, who wins and who loses based on the result of the scene.

If you noticed, this isn’t much of a Dance scene thing but how to write a scene in general because every scene must have these things.

This brings me to my second to the last point.

7.) What do we Discover as a Result of the Dance Scene?There has to be an end goal of discovery. If not, it doesn’t matter how amazing your wordplay is or your character’s actions.

By looking at your story from a birds-eye view, a skilled reader will know you have no idea what you’re doing.

Example:

LALA Land SceenplayLALA Land Dance Scene8. Reference the Sound

Sound is just as big a part of a dance scene as the physical movement is, so don’t hesitate to engage more of the readers’ senses by referencing the sounds that the viewer will hear in the scene, such as the music or, like in this scene from Black Swan, the way that the music ends.

Conclusion

In this post, you learned:

What not to do when writing dance scenes just as much as what to do.

- Tell the reader the type of dance upfront.

- Keep them short—preferably short, punchy sentences.

- Emotion trumps actions.

- Never use dance terminology. It confuses the reader.

- Have a point ot the dance scene.

Now its time to hear from you:

Did I miss anything?

How have you seen dance scenes written in screenplays?

Whatever your answers are, let’s hear them in the comments below.

Happy writing.

Posted in How to Guides By D.K.WilsonPosted on Tagged dance scene

Quotes and descriptions to inspire creative writing

Search for creative inspiration

19,597 quotes, descriptions and writing prompts, 4,960 themes

Search entire site for dance

Descriptionari works better if you enable javascript in your browser settings.

See also

GeneralDance was the speaking of my chi, how it communicated with my own soul and others.

Read more

By Angela Abraham, @daisydescriptionari, February 19, 2021.

GeneralTo dance is the art of my most happy soul.

Read more

By Angela Abraham, @daisydescriptionari, February 19, 2021.

To dance is to heal, to speak in the language of emotion, a language that is so much more ancient than words.

Read more

By Angela Abraham, @daisydescriptionari, February 19, 2021.

Romance / GeneralWhen Alisha flowed in dance it was as if it were the only way her body truly knew how to speak. Verbally she was guarded, physically she would shrink and fade into the background no matter where she was.

On stage her personality, her sensuality burst through into the most vibrant picture of a beautiful soul. Troy watched her move to the music filling the gymnasium, crackling somewhat from the old cassette recorder. For the most part that ancient music machine was her only audience, watching her with those two dusty black eyes. As she turned her eyes caught him standing there, him less adept at hiding in the shadows than she. He dropped his eyes momentarily before looking, his head tilted to one side and a hopeful smile playing on his lips.

Read more

By Angela Abraham, @daisydescriptionari, October 8, 2015.

GeneralWhen Kory heard the music it was like liquid adrenaline being injected right into his blood stream - not so strong as to freak him out, but just enough to make him tingle and start to move his body.

He'd never had a dance class, but he and his mates had jived to music since their early teens, competing in the friendly way boys do to "up" one another. Now, just turned twenty, he was a well oiled machine on the dance floor. He didn't dance to show off, to make the girls watch - but they did. Anyone that could move like their limbs were half liquid in perfect rhythm and still look strong were interesting to say the least. He was used to the attention and he liked it. Then one day a new girl was at the club, not a mover and shaker, kinda shy in the way she moved, but he couldn't help but imagine them together. She was black, her hair in tight braids and he looked at her like he'd never really seen a woman before. Then for the first time in years he felt like if he opened his mouth nothing witty or interesting would come out...

Read more

By Angela Abraham, @daisydescriptionari, February 24, 2015.

Jerome grew up in a household of women who danced. There was never a day that went by without his mother or an aunt taking him by the hands to waltz or boogie around the room. Music was on from first light to last. In a way it flowed through them and between them, creating bonds stronger than the walls of the temple. Every time he heard those old tunes in the years to come he was dancing again, dancing with those women who loved him more than the rising sun.

Read more

By Angela Abraham, @daisydescriptionari, October 8, 2015.

GeneralPolly never walked anywhere.

Her legs extended like a prima ballerina and she glided from place to place, arms held in front, finger tips touching. For her a moment spent not dancing was a moment wasted. Others saw it as eccentricity, but to me it was perfection. Expression through movement was her genius and watching her hone it was more breathtaking than the new flowers of spring.

Read more

By Angela Abraham, @daisydescriptionari, October 8, 2015.

GeneralTo dance was freedom, to dance was to become an opening flower or a bird aloft. To feel the movement was new breath for my body and nourishment for a soul so tired. I could dance until the sweat dripped to the polished wood and my reflection showed pink cheeks.

After that sleep came easy and the dreams were of more twirls and leaps to the music that was part of my blood.

Read more

By Angela Abraham, @daisydescriptionari, October 8, 2015.

%username%, %age%.

Dance and choreography as copyright - n'RIS

Movies, music, literary works come to mind when you think about copyright - what about dance? They can be seen as an art form combining the original expression of choreography, rhythmic and plastic sets of movements. Many agree that the dance should be protected by copyright. Is this true, and what are choreographic works as an object of copyright?

What is a choreographic work

A choreographic work is a set of successive planned human movements that creates an integral choreographic image and is accompanied by music. In the civil legislation of the Russian Federation, choreographic works are classified as protected objects of copyright along with works of literature, science and art (Article 1259 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation). The work will be protected both in part and in full.

In the civil legislation of the Russian Federation, choreographic works are classified as protected objects of copyright along with works of literature, science and art (Article 1259 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation). The work will be protected both in part and in full.

Dance, including plastic and rhythmic movements, can be attributed to a choreographic work. But how do you know which dance will be copyrighted and which won't? Is there a difference between dance moves in a club, a theater production, or dancing in a music video?

In order for a choreographic work to be protected by copyright, it must have two features:

- expressed in some objective form, for example, it can be a sound and video recording, images, text form

- have a creative component

For protection the word "work" plays an important role, since a work is the result of the author's creative work, with a plot and in the form of a finished product. A choreographic work, along with films, performances and novels, can have a plot, culmination and denouement, that is, a single composition with a pronounced idea, images, characters, style and message. Impromptu dances in a club would hardly fit the definition of "choreographic work".

A choreographic work, along with films, performances and novels, can have a plot, culmination and denouement, that is, a single composition with a pronounced idea, images, characters, style and message. Impromptu dances in a club would hardly fit the definition of "choreographic work".

Moreover, a choreographic work may include not only dance, but also an audiovisual show, singers' numbers, theater scenes, and so on. Therefore, the dance, as part of a choreographic work, will be protected by copyright.

The copyright for a choreographic work belongs to the choreographer or other author who is staging it. If several choreographers took part in the creation of a choreographic work, they will be co-authors, regardless of who and what part contributed to the final work. A work created in co-authorship is used jointly by co-authors, unless otherwise provided by agreement between them. In the case when such a work forms an inseparable whole, none of the co-authors has the right to prohibit the use of such a work without sufficient grounds (Article 1258 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation).

How to copyright a dance production

Claiming copyright for a dance is not as easy for a choreographer as it is for example for a poet who has written a poem. As stated above, dance as an object of copyright must be expressed in an objective way. There are several ways to express the dance:

- Make a written description of the dance in as much detail as possible (the choreographers know the name of each movement). The description should not be too general, otherwise it will not be possible to prove the right to it

- Record the dance on video. It is important to understand here that the creators of this video (cameraman, editor, etc.) can be recognized as co-authors if they made a creative contribution to the recording of the video (clause 2 of article 1228 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation). If the operator only presses the button and only controls the filming process, he will not be recognized as a co-author.

You can record yourself by mounting the camera on a tripod. Be sure to set the shooting date and time so that they appear on the recording

You can record yourself by mounting the camera on a tripod. Be sure to set the shooting date and time so that they appear on the recording - Take successive photographs of each movement and, again, take photographs yourself, for example, using a timer, without involving other persons for this

Under civil law, it is not necessary to register copyright, they arise at the time of creation of the work. Despite the fact that copyright does not require registration, in the event of a dispute, the author may need proof of authorship, so they can and should be recorded. For example, there is an increasing number of controversies on TikTok, where the dance spreads across the social network at lightning speed, copied and repeated by thousands of users, making it difficult to ascertain who the original creator was.

If a situation arises in which someone appropriates the authorship of the dance or copies it, the author will need proof that he was the creator of it. Therefore, creators are increasingly resorting to electronic (digital) depositing of their works, that is, fixing copyrights. In n'RIS, you can deposit a work in a few minutes.

Therefore, creators are increasingly resorting to electronic (digital) depositing of their works, that is, fixing copyrights. In n'RIS, you can deposit a work in a few minutes.

When depositing, the author places the file in a secure digital box, the contents of which are not available to third parties. During the procedure, authorship, date and time of registration are recorded. The uploaded file may contain consecutive photographs of the dance, a video recording or a textual description of the movements. If the authors of the dance were several choreographers, when depositing, you can indicate the co-authors and the percentage of their shares in the work. After uploading the file, the author receives a certificate of deposit - it will become a document confirming the authorship of the object.

Deposit a video of your choreography -

take care of fixing the authorship of the dance number

Deposit

Related rights: when a dance has several authors

Initially, the copyright for the dance belongs to the person who created it - the choreographer. In order for the dance to be conveyed to the viewer, someone must perform (dance) it. This is how related rights arise - these are rights related to copyright. Related performance rights may belong to the dancer, but may also belong to the theater, if the dancer has an employment contract (then he creates "service performances", for which he is paid remuneration).

In order for the dance to be conveyed to the viewer, someone must perform (dance) it. This is how related rights arise - these are rights related to copyright. Related performance rights may belong to the dancer, but may also belong to the theater, if the dancer has an employment contract (then he creates "service performances", for which he is paid remuneration).

A related right arises when a theatrical performance (performance) is staged by the production director, and it can also belong to the theater, as in the case of a dancer, if it is a service object.

There is no difference between copyright and related rights in terms of turnover. It is not necessary to register related rights, they arise at the moment when the author's object becomes available for perception. For example, the choreographer who created the dance will own the copyright, and the theater on the basis of which the dance was realized will own related rights.

In order to exercise related rights, the consent of the author of the choreographic work, the choreographer, is required. If you do not first obtain permission to use the copyright object, this will be considered an infringement. Usually, consent is obtained by concluding a license agreement, in which the rights to the object (dance) are transferred in a limited way, for example, for a period of 5 years.

Examples of protected choreographic works

Copyright for a choreographic work extends in any case if it is expressed in an objective form and has a creative component. Some choreographers' work has become so famous that if someone implements their work in their work, it will obviously be considered plagiarism.

For example, in 1983 Michael Jackson introduced Thriller, one of the most famous music videos in history. The musician collaborated with choreographer Michael Peters, who created the unique zombie dance Thriller, which instantly swept the world and still remains an important part of pop culture. Even though millions of people perform the dance, rights holders do not file infringement lawsuits. Another question is that if someone copied Thriller and performed it in a commercial video, this would be a violation of the rights of the authors.

Even though millions of people perform the dance, rights holders do not file infringement lawsuits. Another question is that if someone copied Thriller and performed it in a commercial video, this would be a violation of the rights of the authors.

In 2009, Beyoncé made the crowds move to the song Single Ladies. The dance in the video was created by choreographer Jaquel Knight and is based on a Bob Fosse dance performed by American dancer Gwen Verdon on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1969. Despite the fact that many noticed the similarity of the original performance with Beyoncé's dance, in fact, they turned out to be two different works.

As a result, in 2021, Jaquel Knight became the first ever choreographer to secure the rights to dance moves from Single Ladies. He also choreographed the music video for Lemon by rap rock band N.E.R.D. and Rihanna, and one of his latest viral works is a WAP clip from Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion. Knight is now in the final stages of registering all of his known works.

Knight is now in the final stages of registering all of his known works.

Another high-profile incident occurred with the dance work of Martha Graham, a famous American dancer and choreographer. According to her will, after her death, the copyright for the choreography should pass to photographer Ron Protas. Despite this, the school she founded, the Martha Graham Center for Contemporary Dance, continued to use both the dancer's choreography and the trademark with her name, despite Protas's displeasure. After a lengthy legal battle, in 2002 the U.S. District Court ruled that 45 dances were copyrighted by the Center, 10 of them were in the public domain, 5 were reserved to the persons for whom they were created, and only one dance was owned by Protas.

The court found that Graham worked as an employee of the Center from 1956 to 1991 - during this period she was paid a salary, therefore the works created by her are considered official works, the rights to them belong to the Center. The Center now licenses Martha Graham ballets to professional dance companies and educational institutions. All licensing projects are managed by a professional registrar selected and trained by the Center.

The Center now licenses Martha Graham ballets to professional dance companies and educational institutions. All licensing projects are managed by a professional registrar selected and trained by the Center.

Cases of plagiarism in choreography

Plagiarism is a partial or complete copying of the author's original work, in which the plagiarist refers to himself as the author of the new work. Plagiarism happens in any work, including choreography.

German ballet dancer Kurt Joss showed how to protect yourself from plagiarism. After the musical Sensation in San Remo, starring Marika Röckk, was shown in theaters on September 6, 1951, the choreographer filed a lawsuit to temporarily ban the film from being shown in its original version at the Lichtburg cinema in Essen. He demanded that the scene called Die Sittlichkeit kommission (Moral Commission) be removed from the film, as the movements of the people dressed in black were strikingly similar to the images from his ballet Der grüne Tisch (The Green Table).

The Essen District Court was not long in coming: on September 26, 1951, the production company was ordered to cut the relevant scene from the film. Despite sworn statements by Rökk, director Georg Jacobi and producer Rolf Meyer that they knew absolutely nothing about Der grüne Tisch, the court ruled that there was "a high possibility that the table scene was borrowed in part from a dance drama by Kurt Joss" .

Another discussion about dance plagiarism arose after the release of Beyoncé's musical Countdown in 2011. The singer allegedly borrowed the choreography from two works of art by the Belgian dancer Anna Teresa De Keersmaeker: Achterland 1994 and Rosas danst Rosas 1997. Beyoncé acknowledged that the movements in the video were influenced by De Keersmaeker's ballet, noting that it was not her only inspiration.

Daniil Gleikhengauz, Russian figure skating coach and program director, made a performance for the song Bad Guy by Billy Eilish for the figure skater Alina Zagitova for the tour of Japanese ice shows Fantasy on ice. At the end of the two-week tour, a video of the performance hit the Internet. He was immediately noticed by American dancer and choreographer Jojo Gomez, writing on social media: “That feeling when your choreography for Bad Guy is stolen and broadcast on national television. Daniil Gleichengauz, I'm flattered that I inspired you so much, but next time just hire me and book me a flight to Japan instead of stealing the idea.

At the end of the two-week tour, a video of the performance hit the Internet. He was immediately noticed by American dancer and choreographer Jojo Gomez, writing on social media: “That feeling when your choreography for Bad Guy is stolen and broadcast on national television. Daniil Gleichengauz, I'm flattered that I inspired you so much, but next time just hire me and book me a flight to Japan instead of stealing the idea.

The issue of dance copyright is increasingly emerging on the social network TikTok. In March 2021, American singer and dancer Addison Rae appeared on The Jimmy Fallon Show where she performed eight dances popularized through the platform. Viewers were quick to note that most of the dances featured were created by other dancers, with Ray being the center of attention thanks to other people's merit. Later, to correct the dancers' resentment, Fallon invited dance creators to the show to discuss their creative process and perform dance routines (albeit virtually).

Creating a dance requires a lot of effort on the part of the author, so it's important to know what copyrights dancers, choreographers and other choreographers have. To protect the work from plagiarism and copying, you should fix it through a video recording, photographs or a text description, then deposit it - in disputable situations, the deposit document will become one of the proofs of ownership of the rights to your dance.

Protect your works

Go to your personal account and manage your

Intellectual Property Online

Deposit

The Art of Hearing Dance: Practices of Foreign Schools of Audio Description / Un Certain Regard

Listen to Publication Commentary: color photograph. The figure of a red-haired dancer frozen in a jump against the backdrop of the sea. She has lush red hair and a slender three-quarter body. The girl is wearing a short tight-fitting black top with a closed neck and bare shoulders, shorts and a long translucent black skirt fluttering in the wind. She lifts the edge of her skirt with straight outstretched arms. The dancer seems to be standing in the air on her left knee, her right leg is bent and raised high up. She tilted her head slightly and looked down.

She lifts the edge of her skirt with straight outstretched arms. The dancer seems to be standing in the air on her left knee, her right leg is bent and raised high up. She tilted her head slightly and looked down.

"Dance is a poem, every movement in it is a word." This statement is attributed to the famous adventurer and dancer Margareta Gertrude Zella, whom the whole world knows under the name of Mata Hari. But the words of such a poem are not available to everyone. Already from the very definition of the word "dance" - the art of plastic and rhythmic movements of the body - it is obvious that vision plays a big role in its perception. What remains if you do not see the movements of the dancers? Music? Strained breathing? Rustle of clothes? The sound of footsteps? Can all this interest the viewer and give him pleasure?

Audio description (which in our country is called audio commentary) is a way to convey the beauty of dance to people who, for one reason or another, cannot see it. Joel Snyder, one of the leading experts in this field, calls audio description a form of literary work and likens it to a haiku. With just a few words, the audio descriptor creates a verbal copy of the visual image, translates the visible into the audible. Bright, figurative words draw vivid pictures before the mind's eye of the listener.

Joel Snyder, one of the leading experts in this field, calls audio description a form of literary work and likens it to a haiku. With just a few words, the audio descriptor creates a verbal copy of the visual image, translates the visible into the audible. Bright, figurative words draw vivid pictures before the mind's eye of the listener.

“Dance is not just movement,” says Iris Permuy Hercules de Solas, audio descriptor for dance TV shows on a Spanish TV channel. “Dance conveys feelings and moods. This is artistic art. The dancer draws pictures with his whole body, creates ephemeral masterpieces that the audio descriptor must have time to consider and describe.

“The entire visible universe is movement,” said dance teacher and theorist Rudolf von Laban. To describe this movement to someone who does not see it is not an easy task. However, it is quite doable.

Anne Hornsby, one of the UK's first audio descriptions, has described many theater productions, including the famous Mamma Mia! and Les Misérables, believes that special choreographic education is not required: “Only the usual skills of verbal description are needed. The ability to briefly, but figuratively express their thoughts; attentiveness and observation; the ability to convey the mood of the work; the ability to meet the allotted time - that's what really matters. At the same time, the soundscape and music cannot be drowned out – the viewer must hear their breathing.”

The ability to briefly, but figuratively express their thoughts; attentiveness and observation; the ability to convey the mood of the work; the ability to meet the allotted time - that's what really matters. At the same time, the soundscape and music cannot be drowned out – the viewer must hear their breathing.”

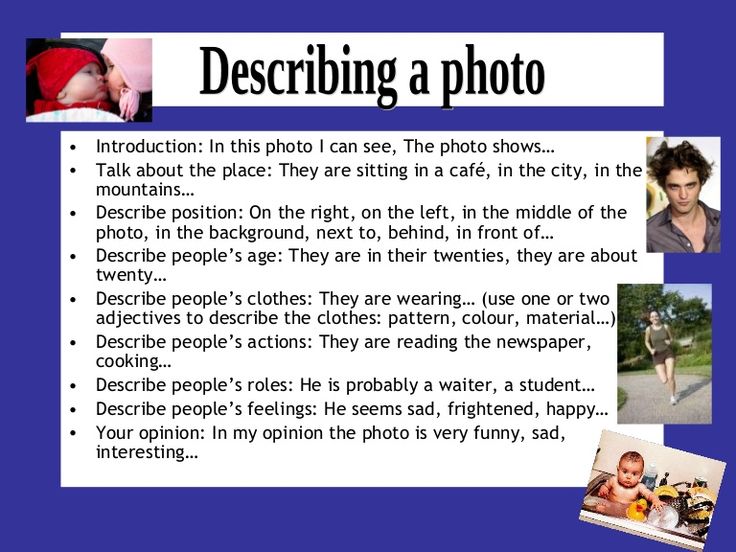

Do all dances need to be described? In the back of the hall, a barefoot girl is dancing a contemporary dance. She wears knee-high athletic trousers and a loose gray T-shirt. She stands on a straight right leg, the left straight leg is raised to the level of the waist and laid aside, the body is tilted to the opposite side, the right arm bent at the elbow is raised up, the left is wound behind the back. The operator shoots the girl's dance on a video camera.

If we are not talking about an independent dance production, but about an episode of a play or a film, then, on the advice of the leading specialist in audio description of dance, the author of the Talking Dance manual, Louise Fryer, you need to ask yourself an important question: what role does this dance play? Is it necessary for the development of the plot? Perhaps he somehow reveals the character of the characters? Maybe he tells about the relationship between the heroes of the production? Do these relationships change after or even during the dance? Or does the dance simply fill in a pause in the play so that the actors can change for the next scene? Does dance contribute to creating a certain atmosphere? For example, it can immerse us in a historical era.

During the same performance or film, we can see different types of dance that serve completely different purposes. The audio descriptor must understand the intent of the scriptwriter and director and, depending on this, choose a way to describe this or that dance. “The choreographer and director can help a lot by sharing their vision,” says Louise Fryer. “It’s also good to be present at the rehearsal.”

Photo: Tim Gouw

Tiflocommentary: seashore, cloudy sky and bright orange rays of the setting sun. Five girls dance on the platform, they run one after another in a circle: the left hand is raised up, the hand is turned with the palm to the sky, the right hand is bent at the elbow and directed forward with the palm away from you. All of them are in white corsets tightened on the back with thin straps. Four girls are wearing light long light skirts with a fluttering frill at the bottom, while the fifth girl is wearing a more fluffy light skirt with rows of frills along the entire length. She rises high from quick movements, under the skirt of the dancer there are light tights with lace.

She rises high from quick movements, under the skirt of the dancer there are light tights with lace.

Audio description is a kind of translation (intersemiotic or intersemiotic, according to the classification of R.O. Jacobson). As Bruce Metzger wrote: “Translation is the art of choosing the right thing to lose.” These words fully apply to the description of the dance. Depending on its goals and the plot of the work, sometimes you need to focus on the technique of the dancers, sometimes on the costumes, sometimes on the behavior of the characters during the dance, and in some cases it is enough just to say that the characters are dancing without going into details, so how they can distract from the development of the plot.

The well-known film translator Aleksey Kozulyaev repeatedly emphasizes that the audio descriptor is part of the "collective author" of an audiovisual work, and each addresses the viewer in his own language: costume designers - in the language of costumes, the composer - in the language of music, actors - in the language of words, facial expressions and gestures, the director - in the language of images, etc. All together they create a single work. The task of the audio descriptor is to merge into the structure of this collective author so that his “language” organically fits into the general choir.

All together they create a single work. The task of the audio descriptor is to merge into the structure of this collective author so that his “language” organically fits into the general choir.

It must be remembered that a person comes to a performance or a cinema to relax and enjoy. Therefore, you can not overload the viewer with an abundance of details. An overly detailed description can be accurate, but it also confuses viewers and distracts from the plot.

Word choice

The dancers themselves say that when you dance for real, you involuntarily discover that you don't have enough words, and there are not enough concepts in any language of the world to convey your feelings. Isadora Duncan, for example, said: "If you could explain something in words, there would be no point in dancing it." No wonder they say that dance is like love: this state can be felt, but it is very difficult to describe.

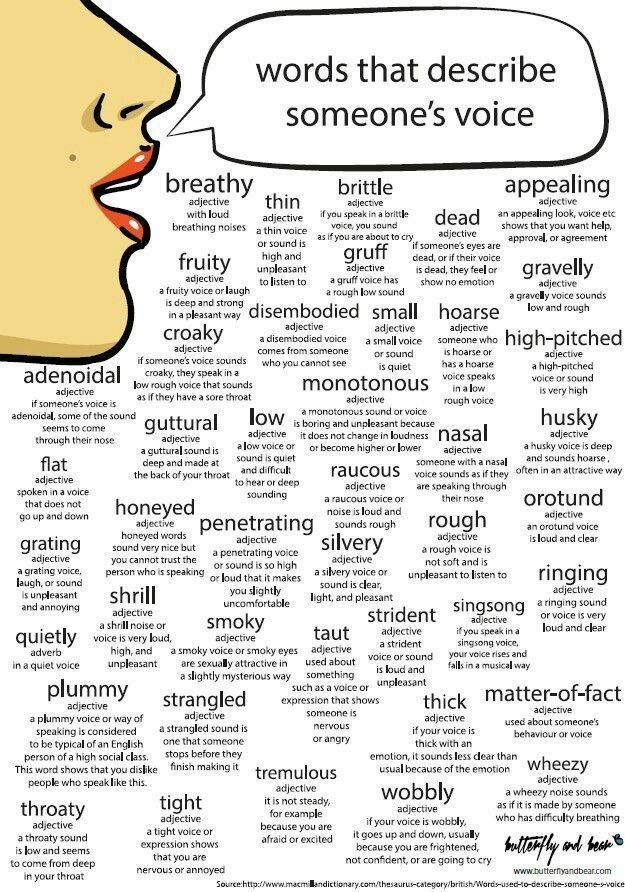

"You need to create verbal pictures of the dancers' movements," says Ann Hornsby, "but in a way that doesn't sound like a dry description of physical exercise. " Iris Permuy Hercules de Solas adds: "It takes a rich vocabulary to describe it colorfully, gracefully, energetically, sadly, just like the dance itself."

" Iris Permuy Hercules de Solas adds: "It takes a rich vocabulary to describe it colorfully, gracefully, energetically, sadly, just like the dance itself."

Description: color photograph. Scene. The dancer in a black suit stands with his back to the audience, his right leg is set aside on his toe, his left hand is extended to the dancer, who is flying back in a jump with her arms spread apart. She looks at the dancer and smiles broadly. She is wearing a white suit: a tutu with a flat skirt, a leotard with thin straps with golden embroidery in the center, white leggings and pointe shoes. The dancers are watched by performers dressed as villagers. In the depths of the stage, in the blue twilight, there are scenery with buildings and the silhouette of a tilted ship.

The choice of the right word is the most important moment in the description of the dance, according to all experts. “For people who are far from choreography, the most terrible thing is the special terminology,” says Louise Fryer. - Knowledge of professional terms will not hurt. Describing, say, architecture, we want to show the difference between the Norman arch from the Gothic or the Ionic order from the Corinthian. By the same logic, it is important for us to know whether this ballet rotation is a pirouette or not. Of course, not everyone may know what a pirouette is (although there may be experts in the auditorium), however, if we use a special term, we thereby emphasize that it is ballet on stage, and not ballroom dancing.

- Knowledge of professional terms will not hurt. Describing, say, architecture, we want to show the difference between the Norman arch from the Gothic or the Ionic order from the Corinthian. By the same logic, it is important for us to know whether this ballet rotation is a pirouette or not. Of course, not everyone may know what a pirouette is (although there may be experts in the auditorium), however, if we use a special term, we thereby emphasize that it is ballet on stage, and not ballroom dancing.

Ann Hornsby stresses that the meaning of the terms must be clarified. Sometimes, when describing a ballet, it is useful to make an introduction before it begins and explain there what the words “pirouette”, “arabesque”, “fuete”, etc. mean.

Anne Hornsby explains: “The meanings of some words are clear without explanation. However, if possible, brief explanations do not hurt. But what you should not do is just list professional terms and dance moves. The viewer simply does not have time to comprehend all this in a short time. In addition, such a technical description will not say anything about the quality of the movement, its speed, the plot of the dance, the emotions of the hero and his motives.

In addition, such a technical description will not say anything about the quality of the movement, its speed, the plot of the dance, the emotions of the hero and his motives.

Laban's movement analysis

The well-known choreographer, dance theorist, teacher Rudolf von Laban developed a movement analysis system that is still used today. He discovered that any dance step exists in four dimensions, or factors: space, time, dynamics and flow. Therefore, the process of motion analysis begins with finding out the following main points: where the motion occurs; why the movement occurs; how the movement occurs; What are the traffic restrictions? All this will help the audio descriptor to find the right words.

It is relatively easy to describe a dance that has a story. However, as von Laban noted, “modern dance may lack a clear story. It is often impossible to convey the content of the dance in words, although the movements themselves can always be described.

He further explains: “An actress playing the part of Eve can pick the forbidden fruit in different ways, while her movements will express different emotions. She can seize the fruit greedily and quickly, or slowly and sensually. But when we describe movement as “greedy,” “sensual,” or “dispassionate,” we are not really talking about what we see. The viewer at this moment sees a fast and sharp or slow and sliding movement of the hand. And already the imagination interprets the actions of Eve as greedy or sensual.

She can seize the fruit greedily and quickly, or slowly and sensually. But when we describe movement as “greedy,” “sensual,” or “dispassionate,” we are not really talking about what we see. The viewer at this moment sees a fast and sharp or slow and sliding movement of the hand. And already the imagination interprets the actions of Eve as greedy or sensual.

Joel Snyder points out that von Laban is essentially referring to the fundamental principle of audio description: "Describe only what you see." “It's important to be precise,” Snyder explains, “but the description needs to be alive so that the listener paints the picture in their own mind. You need to be objective, using precise and figurative words, while avoiding interpretation. That is, our Eve “plucks an apple with a sharp, impetuous movement of her hand,” and not “with a mixed expression of greed and guilt on her face.”

Tiflocommentary: color photograph. Light walls, gray door, padlocked. To the left, a diagonal of a metal staircase with a railing rises up. Halfway up, a ballerina in a black leotard with lace-trimmed straps and a cutout at the chest. She stands on her right leg, with her right hand extended forward, holding on to the parapet, her left leg and left arm raised at an angle of 45 degrees and laid parallel back. The body is turned towards the viewer, the back is strongly concave. Her hair is pulled back into a bun, and on her feet are flesh-coloured pointe shoes.

Halfway up, a ballerina in a black leotard with lace-trimmed straps and a cutout at the chest. She stands on her right leg, with her right hand extended forward, holding on to the parapet, her left leg and left arm raised at an angle of 45 degrees and laid parallel back. The body is turned towards the viewer, the back is strongly concave. Her hair is pulled back into a bun, and on her feet are flesh-coloured pointe shoes.

Dance is the language of tradition

Description of traditional dances is a separate line of audio description. Dr. Doning Liang of the Hong Kong Audio Description Association has extensive experience in describing Chinese dances, in particular the famous Lion Dance. One of the difficulties is that completely different people will listen to the description: both those who are familiar with this dance and those who hear about it for the first time.

“I'm not just describing the dance,” says Doning, “I'm sort of acting as a teacher for blind people.