How to dance like a mexican

The Mexican Hat Dance - Jarabe Tapatio

The jarabe Tapatío is a Mexican dance, often called the national dance of Mexico.

- donquijote

- Mexican Culture

- Mexican Society

- Jarabe Tapatio

NATIONAL IDENTITY

The jarabe Tapatío is a Mexican folk dance, often called the national dance of Mexico, and better known internationally as the Mexican hat dance. Despite its rather innocent steps by today’s standards (dancers do not touch one another), early 19th century colonial authorities found the moves too sexually suggestive and even challenging to Spanish rule.

They banned the dance, inspiring popular appreciation for the Jarabe Tapatío in Mexico, as the ban added an element of rebellious expression to it and provided an opportunity for dancers eager to make a statement on social freedom and political independence a chance to subtly defy the colonizers.

Mexican independence in 1821 brought a new sense of cultural awareness, and the popularity of jarabe dances spread even more, along with national identity. Although other varieties of jarabe exist including jarabe de Jalisco, jarabe de atole and jarebe Moreliano, the Tapatío version, which originated in Guadalajara, is the most famous.The dance celebrates romantic courtship. It is usually performed by a man and a woman, where the man appears to invite his partner into a world of intimate affection. At first, the woman rejects her partner’s advances, but warms up to his persistence as the two dance on, only to reject him again when her positive signals inspire excessive giddiness in her suitor.

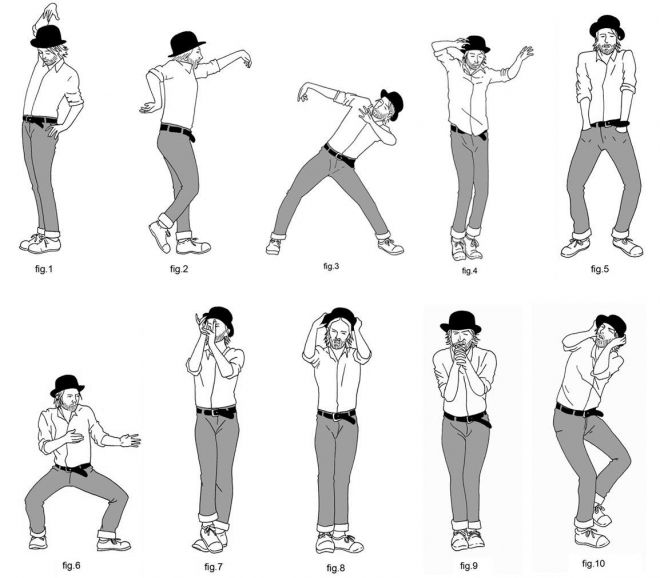

THE DANCE

During the dance, the man’s sombrero is placed on the ground, and after lively hopping, sliding and kicking around the sombrero, the woman bends to pick up the hat, at which point the man kicks his leg over her head. Needless to say, timing and careful choreography are important. Then the performance closes when she holds the hat up and both dancers’ faces disappear behind it, leaving captivated audiences to assume that the two are finally confirming mutual romantic interest and sealing it with a kiss.

Then the performance closes when she holds the hat up and both dancers’ faces disappear behind it, leaving captivated audiences to assume that the two are finally confirming mutual romantic interest and sealing it with a kiss.

THE COSTUME

The Mexican hat dance and the dancer’s clothing have become nationally and internationally recognizable symbols of Mexican heritage. Women wear a wide, colorfully decorated skirt and blouse outfit, the style of which is called China Poblana. The origin of the name and style of the skirt has inspired curious legends including that of a beautiful 17th century princess from India named Mirra who was kidnapped, taken to the Philippines, and sent to Mexico to be sold there as a slave. Her exotic and vibrant clothing left such an impression, that woman in Mexico began copying the style and adapting and embellishing it to popular indigenous tastes.

Men traditionally wear a black suit with metallic embroidery called a charro. The man’s pant legs are lined with silver buttons that highlight his flashy kick and stamp moves. The origin of the name of the dance itself has also stirred some controversy. The Arabic word Xarab means mixture of herbs. The name may refer to the mix of influences that created the dance style, which includes waltz, polka, and indigenous American dances.

The man’s pant legs are lined with silver buttons that highlight his flashy kick and stamp moves. The origin of the name of the dance itself has also stirred some controversy. The Arabic word Xarab means mixture of herbs. The name may refer to the mix of influences that created the dance style, which includes waltz, polka, and indigenous American dances.

THE MUSIC

The music that accompanies the dance may be performed by mariachi bands or other types of string instrument groups. Originally composed by Jesus Gonzalez Rubio in 1924, the song increases its tempo as the steps and story line of the dance intensify.The jarabe Tapatío dance is a Mexican folk art that recalls the sense of national identity fostered by post revolutionary efforts to unify and celebrate its traditions and culture. The charm and grace of the dance along with the vivid color of its clothing, which provides viewers with a swirling collage of vibrancy and shine, have captured the hearts of folk art lovers in Mexico and around the world.

Latin American dance | History, Styles, & Facts

Aztec round dance

See all media

- Related Topics:

- tango juego de los voladores samba rumba baile de palo

See all related content →

Latin American dance, dance traditions of Mexico, Central America, and the portions of South America and the Caribbean colonized by the Spanish and the Portuguese. These traditions reflect the distinctive mixtures of indigenous (Amerindian), African, and European influences that have shifted throughout the region over time.

This article surveys selected genres of dance across the vast and diverse region of Latin America. After a brief consideration of dance in preconquest cultures (for further treatment, see Native American dance), the narrative turns to the profound influence on dance practice of the European-imposed Roman Catholic Church and its calendar of festivals and commemorations. At the same time, imported elite dance practices became part of the colonial cultures and were in turn infused with local and regional flavours. From the 19th century on, national variations have asserted themselves throughout dance practice in Latin America and in the Latino cultures of North America. (Latin American music shows a similar path of development; a great deal of the region’s nonclassical music, both vocal and instrumental, accompanies or shares a history with dance.)

At the same time, imported elite dance practices became part of the colonial cultures and were in turn infused with local and regional flavours. From the 19th century on, national variations have asserted themselves throughout dance practice in Latin America and in the Latino cultures of North America. (Latin American music shows a similar path of development; a great deal of the region’s nonclassical music, both vocal and instrumental, accompanies or shares a history with dance.)

Although the article discusses theatrical derivatives of traditional dance (which are often grouped under the name folklórico) because of their visibility and importance in the region, not included are international forms of concert dance, such as ballet and modern dance. After a chronological survey of broad trends, with examples, the article focuses on individual countries. Haiti, which was colonized by the French, is included in this article because it shares important African-derived ritual practices with Brazil and Cuba and because its history is entwined with that of the Dominican Republic. Perhaps needless to say, this article can only skim the surface of such a vast topic.

Perhaps needless to say, this article can only skim the surface of such a vast topic.

From encounter to independence

On their arrival in the Western Hemisphere in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, explorers from the Iberian kingdoms of Portugal and Castile (Spain) encountered peoples—even entire empires—previously unknown to Europeans. A few of the Europeans wrote about the music and dance practices they observed during ritual festivals among the local populations. The indigenous populations were decimated by disease, forced labour, and warfare, and their history was disrupted. In the Caribbean very few indigenous people survived, but on the mainland significant populations managed to preserve their communities.

Some early dance history can be inferred from the archives and from what seem to be continuous practices. For example, creation stories were a common aspect of indigenous spiritual practice, and their telling often incorporated dance as a vital element. Natural forces (i.e., gods and goddesses) and animal spirits were honoured or represented as dramatic actors; dance rituals were often meant to forestall or explain cataclysmic events. The great civilizations of the Aztec and Inca (like the Roman Catholic Church of their conquerors) organized time according to complex ritual calendars, and dance was essential in their communal ritual life.

Natural forces (i.e., gods and goddesses) and animal spirits were honoured or represented as dramatic actors; dance rituals were often meant to forestall or explain cataclysmic events. The great civilizations of the Aztec and Inca (like the Roman Catholic Church of their conquerors) organized time according to complex ritual calendars, and dance was essential in their communal ritual life.

The dances of the Aztec were precisely structured and executed. Priests trained young people in the movements of the ritual dances and organized the ceremonies into massive arrangements of dancers who moved in symbolic geometric patterns. Combat was a major theme that featured male dancers: weapons in hand, individuals or groups of dancers enacted struggles between gods or between military units such as eagle warriors and jaguar warriors. Dances could last more than a day to test the warrior-dancers’ endurance and commitment. In some ceremonies dancers moved in columns to represent revolving astral bodies in their annual and millennial circuits; in others they represented planters working in looping zurcos (furrows). In the danza de los voladores (“dance of the fliers”), one of the few surviving preconquest dances of Mesoamerica, traditionally four fliers (dancers) who are suspended upside down from the top of a tall pole make 13 revolutions for a combined total of 52; in the Nahuatl belief system of the Aztec and Toltec peoples, 52 years make a “year-binding,” or xiuhmolpilli.

In the danza de los voladores (“dance of the fliers”), one of the few surviving preconquest dances of Mesoamerica, traditionally four fliers (dancers) who are suspended upside down from the top of a tall pole make 13 revolutions for a combined total of 52; in the Nahuatl belief system of the Aztec and Toltec peoples, 52 years make a “year-binding,” or xiuhmolpilli.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

Ritual contexts

The institution of the Roman Catholic Church—with its rituals, doctrines, and ways of looking at the world—accompanied the Iberians to the New World and was integral to the functioning of the viceroyalties in New Spain (based in Mexico; 1535–1821) and Peru (1542–1824), which between them administered the colonial territories of the Spanish. After the military conquest, religious music, dance, processions, and festivals became tools of cultural transformation and social control. Catholic priests and monks—Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites, Augustinians—allowed, even encouraged, indigenous dancers to continue their rituals, modified to incorporate Catholic saints and ideas in place of their own. The indigenous peoples adapted their own rich calendar of public festivals to new uses and new places. Into the present day, ancient ritual dances echo in the yearly observances that take place in front of churches and at other sacred sites, especially as part of the patronal fiestas, the festivals in honour of a town’s (or country’s) patron saint.

The indigenous peoples adapted their own rich calendar of public festivals to new uses and new places. Into the present day, ancient ritual dances echo in the yearly observances that take place in front of churches and at other sacred sites, especially as part of the patronal fiestas, the festivals in honour of a town’s (or country’s) patron saint.

In Roman Catholic countries around the world, nonliturgical Carnival celebrations mark the last-chance merrymaking that occurs during the weeks before Ash Wednesday, the day that begins the austere 40-day period of Lent; in many parts of Latin America, Carnival parades feature exuberant group dances. As in the religious pageants, fantasy and elaborate costuming allow the Carnival dancers to become the “other” and to use dance as a means of escaping the anxieties of everyday life.

Perhaps the most widespread dance ritual of Latin America derives from the dance of Moors and Christians (la danza de Moros y Cristianos), which was performed at major religious festivals in medieval Spain. The dance was based on an older form of religious street theatre, autos sacramentales (“mystery plays”), portrayals of the competition of forces of good and evil. In the 8th century Moors had brought Islam to Spain from North Africa, and Christians in Spain fought to regain ground until 1492, when the houses of Aragon and Castile expelled the remaining Muslims. (For more on that period, see Spain: Christian Spain from the Muslim invasion to about 1260.) After the dance-drama was imported to Mesoamerica and Peru in the 16th century, the oppositional forces in it were refashioned to cast the Spanish (good) against the Indians (bad). Although the danza de los Moros y Cristianos exists throughout Latin America, it is known by a variety of names, including danza de la conquista, danza de los Moros, marujada (in Brazil), and danza de Santiago.

The dance was based on an older form of religious street theatre, autos sacramentales (“mystery plays”), portrayals of the competition of forces of good and evil. In the 8th century Moors had brought Islam to Spain from North Africa, and Christians in Spain fought to regain ground until 1492, when the houses of Aragon and Castile expelled the remaining Muslims. (For more on that period, see Spain: Christian Spain from the Muslim invasion to about 1260.) After the dance-drama was imported to Mesoamerica and Peru in the 16th century, the oppositional forces in it were refashioned to cast the Spanish (good) against the Indians (bad). Although the danza de los Moros y Cristianos exists throughout Latin America, it is known by a variety of names, including danza de la conquista, danza de los Moros, marujada (in Brazil), and danza de Santiago.

Blended rituals such as la danza de la conquista became part of colonial religious festivals. Theatrical enactments of the conquest, or farsas de guerra (“war farces”), played a prominent role in entertaining and enculturating colonial populations. In Mexico the entertainments became known as mitotes (from the Nahuatl mitotia, “to make dances”). Mitotes drew upon both Spanish dramatic action, which featured lengthy sections of dialogue, and the Aztec and Chichimec Indian tradition of using divided bands of enemies to represent the central theme of battle.

Theatrical enactments of the conquest, or farsas de guerra (“war farces”), played a prominent role in entertaining and enculturating colonial populations. In Mexico the entertainments became known as mitotes (from the Nahuatl mitotia, “to make dances”). Mitotes drew upon both Spanish dramatic action, which featured lengthy sections of dialogue, and the Aztec and Chichimec Indian tradition of using divided bands of enemies to represent the central theme of battle.

The conquest dances were taken to Spain and performed for elite audiences. Although their popularity faded in Spain during the 17th century, these spectacles became models for further ritual dances in the New World. July 25 marks the feast day of St. James (Santiago, Spain’s patron saint) throughout Spanish-speaking Latin America. For this major festival, many local traditions included dances to commemorate ancient battles between opposing forces. Dances of los vejigantes in Puerto Rico and los tastoanes in Mexico are prominent examples. In both festivals there are representations of Spanish horsemen and masked figures representing African slaves or members of the indigenous resistance.

In both festivals there are representations of Spanish horsemen and masked figures representing African slaves or members of the indigenous resistance.

Upper-class immigrants from Europe brought with them their fashionable social dances (los bailes de salón). The aristocracy of the viceroyalties kept up with a succession of popular European dances. These included open-couple dances, in which couples generally did not touch—such as minuet, allemande, sarabande (zarabande in Spanish), chaconne, galliard, pavane, and volta. The interdependent-couple contredanse (contradanza in Spanish) and its variations (quadrille, lancer, and cotillion) were developing during the 17th century. Such choreographed dances of intricate geometries originated in Europe before sweeping quickly through Latin American ballrooms and dance salons during the 18th century. The fashion caught on across the social spectrum; for example, indigenous dancers in northeast Mexico adopted the contradanza into their ritual expression of the matlachines dance.

Contradanzas and quadrilles remained common throughout Latin America and the Caribbean in the early 21st century. Their characteristic interlacing lines, bridges, circles, and grand right-and-left patterns are easily recognized in hundreds of dances. In the Caribbean, contradanzas and quadrilles included the bélè, belair, and belén, as well as kadril and numerous other variants of quadrille. In northeastern Brazil they became quadrilhas, the traditional dances for the festival of St. John the Baptist (São João) on June 24; the dances remained popular in the Northeast, and into the 21st century quadrilha competitions occurred on the state and national level.

As struggles for independence roiled Latin America during the 19th century, closed-couple dances, specifically the waltz, schottische, and polka, became fashionable in elite society. In closed-couple dances the partners touch most of the time; as a result, these dances were considered rebellious acts of sexual immorality. In addition the new couple dances were distinctive because each couple could choose steps from a range of possibilities. With the passage of time, these social dances became commonplace and their intimacy more accepted. The dances migrated to the countryside, where most of the people of African heritage lived. African-influenced hip movements—which could be seen as sexually suggestive—were incorporated into the dances, and they again transgressed the Roman Catholic Church’s standards of morality.

In addition the new couple dances were distinctive because each couple could choose steps from a range of possibilities. With the passage of time, these social dances became commonplace and their intimacy more accepted. The dances migrated to the countryside, where most of the people of African heritage lived. African-influenced hip movements—which could be seen as sexually suggestive—were incorporated into the dances, and they again transgressed the Roman Catholic Church’s standards of morality.

▷ Traditional Mexican Dances 🥇 en.versiontravel.com

In the culture of Mexico we find exciting dances with a long history. While some are very lively, others are slower. Likewise, there may be various influences in them, although some are local. In this article, we will tell you the name and tell you about the most important. In addition, we will show you images and videos.

Below you have an index with all the items we are going to cover in this article.

Content

- 1 Tapatio syrup

- 2 Old

- 3 Huapango

- 4 La Bamba

- 5 Yukatkekan Jaran

- 6 deeds dance

- 7 shells

- 8 Northern Polka 9000 9 omarabet

- 11 brittle

Tapatio syrup

Tapatio syrup is National dance from Mexico. It originated in the 19th century in Jalisco and combines several regional dances. The word tapatío refers to the zapateado performed by men.

It originated in the 19th century in Jalisco and combines several regional dances. The word tapatío refers to the zapateado performed by men.

When it comes to dancing, a man surrounds a woman to woo her. She stomps and waves her skirt. Both wear typical village costumes: the man is dressed in a charro suit, and the woman in poblana porcelain.

If you want to know more about the typical dress of the country, we recommend that you visit this article: Typical Mexican costumes by region.

This regional dance is so typical that it is usually danced at a Quinceañera party where a young woman celebrates that she is 15 years old and therefore has passed into adulthood.

Old

This folk dance is quite amazing for people who don't know it, as their dancers are dressed like elders. He is represented in Michoacán and was born in the city of Haracuaro.

In the beginning, this dance, dating from pre-Spanish , was performed as part of a ritual in honor of an old god or god of fire. The costume they wear consists of a wooden mask, a walking stick, wooden-soled shoes, trousers, a white shirt, and a Mexican shawl or jorongo ,

He mexican shawl or jorongo This is a typical men's garment from Mexico, traditionally used to protect against cold and rain. It looks like a poncho and is usually quite colorful.

The main characters are four men who imitate old people through their falls and the way they walk. They are led by a couple known as Veripiti and Maringuía . They are also ugly teasing dance of four old men , In Michoacán, children are taught from an early age.

They are led by a couple known as Veripiti and Maringuía . They are also ugly teasing dance of four old men , In Michoacán, children are taught from an early age.

Huapango

Huapango is practiced in various states, including Hidalgo, Puebla, San Luis Potosi and Veracruz. Therefore, in each territory we find different variants, although they have certain common characteristics.

This Mexican dance is usually performed on a wooden stage. Usually the man wears white trousers and a hat, while the woman wears a rather wide white skirt. Music is performed by three people who play the violin and buster and huapanguera (two types of guitar).

La Bamba

Bamba is one of the mixed dance the most representative of the state of Veracruz. It mixes the seguidillas and fandangos of Spain with the zapateados and guajiras originating in Cuba.

This dance is represented by one couple, and the color that prevails in both people is white. Between them they form a loop with the movement of their steps, as we can see in this video:

Yucatecan Jarana

The Yucatecan Jarana is typical of the Yucatan Peninsula. One aspect that draws the most attention is that the dancers wear objects on their heads while representing the dance.

One aspect that draws the most attention is that the dancers wear objects on their heads while representing the dance.

This style began between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when the Spaniards who were in the area danced. Over time, the Mexicans adapted it to their style. He dances like a couple and walks dressed in white.

Deer dance

This pre-Hispanic dance is practiced in state Sonora . It has three symbols: the deer (an animal revered by the natives), pascola and the coyote. The dance represents deer hunting, so the person who plays this role must be quite nimble.

The dance represents deer hunting, so the person who plays this role must be quite nimble.

The instruments that interpret the music of the deer dance are percussion, in addition to the reed flute.

shells

Conjeros developed after the arrival of the settlers in the territory, so although it is an indigenous dance, it incorporates Spanish elements such as some religious themes.

This dance has two forms. One is called hours and honors femininity, night, mother earth and the jaguar. The other reveres masculinity, the day, solar energy and the eagle. One of the elements that make up the costumes are feathers.

One of the elements that make up the costumes are feathers.

Northern Polka

This popular dance is the mestizo, as its origin is German. The natives watched the upper classes of the settlers dance it and they ended up adapting it to their style.

This is practiced mainly in the northern states, among which we find Baja California, Coahuilla, Chihuahua, Nuevo Leon, Sonora and Tamaulipas.

Pineapple flower

Pineapple flower is a dance that originated in San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec, Oaxaca. This is very recent, from the 20th century. At 19In 58, Governor Alfonso Pérez Gasga ordered that the author Samuel Mondragón develop an aboriginal choreography for a piece of music with that title.

The responsible person was Polina Solis. Since then, this dance has only been performed by women who wear huipil or a sleeveless shirt in bright colors and two long braids with colored stripes. In addition, they carry a pineapple on their shoulder.

In addition, they carry a pineapple on their shoulder.

Scrabble

Raspa is a representative dance of eastern Mexico that originates in Veracruz. It is a mestizo dance because it mixes elements of the natives with the forms of the settlers. Because of its light structure, children are usually taught in school.

brittle

Quebradita is also known as rocking horse .

In his music we hear the rhythm of the Mexican cumbia. This is a fusion of two different musical styles: techno and folklore. In it, the man hugs the woman around the waist and puts his right leg between the two legs of the girl. The couple spins and makes small jumps or streams.

The couple spins and makes small jumps or streams.

One practice that is practiced is Tombe in which the man forces the woman to lean back straight. The brightest modality is acrobatic.

Top image Brendan,

This article has been shared 63 times.

Finally, we have selected the previous and next block article " Prepare your trip " so you can continue reading:

Mexican dance "Voladores" - Culture of Mexico

Perhaps one of the most impressive among the many national dances in Mexico are the dances "Voladores" and "Guaguas". And because they combine elements of an acrobatic show and require special equipment, and because they are colorful and have a deep meaning, rooted in the Indian traditions of pre-Hispanic Mexico. These are indeed very ancient dances that were previously performed as rituals. Dances may have existed as early as 1200 AD. Today they are very popular in the Papantla region, the state of Veracruz, as well as in the states of Puebla, Hidalgo and San Luis Potosi.

And because they combine elements of an acrobatic show and require special equipment, and because they are colorful and have a deep meaning, rooted in the Indian traditions of pre-Hispanic Mexico. These are indeed very ancient dances that were previously performed as rituals. Dances may have existed as early as 1200 AD. Today they are very popular in the Papantla region, the state of Veracruz, as well as in the states of Puebla, Hidalgo and San Luis Potosi.

Both dances are impressive in their execution and use rotating mechanisms made of wood. In the dance "Voladores" ("Flyers"), rotation is carried out in a horizontal plane, and in "Guaguas" - in a vertical one. The use of mechanisms carries a certain risk for the dancers, but it is extremely spectacular for the audience. There is evidence that these dances existed during the Toltec period, and with them they spread to Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador. Both dances are closely connected with the cult of the fertility gods Xipe-Totec and Tlazolteotl.

Both dances came from very ancient ceremonies and were not just entertainment. In the Papantla region, performers say that "Voladores" is a greeting to the Sun Father and a request for rain, while "Gua Gua" symbolizes gratitude for the gifts received. Therefore, when both dances are performed in the same place, "Voladores" is performed first.

The use of rotary mechanisms of their tree has its own characteristics. For "Voladores" a pole is used, and for "Guaguas" a cross or mill is used. In the past, Voladores performers used a pole high enough to reach the ground in 13 revolutions around the pole. Multiplying 13 by 4 (the number of dancers), we get 52 - an extremely important number in calendar symbolism, denoting Shiumolpilli, or the 52-year cycle of the Indian calendar. The rotation of the mechanism in the dances personified the movement of the Sun, which the participants of the ceremony greet with their music and dance movements. Researchers believe that the combination of symbolic elements was achieved in the Aztec era, which gravitated toward spectacle: music as an offering to the gods, a dangerous dance on top of a pillar, four dancers instead of two, the position of the performers upside down and with outstretched arms, and, of course, brightly colored costumes. birds associated with the sun: macaws, quetzals, eagles and larks.

birds associated with the sun: macaws, quetzals, eagles and larks.

Loading

Watch on Instagram

The symbolism of both dances, associated with fertility, is expressed in the aspiration of the dancers to the ground from the height of a pillar, similar to the fall of raindrops.

During the era of the Conquest, dances persist despite the attempts of missionaries to eradicate them. An Inquisition document has been published recommending a ban on the Voladores dance. In some regions the ban did not work, in others it was successful, and these dances disappeared for a while. But since the tradition had deep roots, they reappeared and are still being performed.

For the Voladores dance, a pole is used, made from a tree trunk, which must be cut down and “planted”, that is, dug in. All these actions are accompanied by ceremonies. Only three local breeds are suitable for the ritual. The tree must be relatively tall (up to 40 m) and straight, and its wood must be strong enough to support both the rotating mechanism and the weight of the performers.

The dancers who prepare the tree-cutting ceremony must observe strict sexual abstinence, just as was done in pre-Hispanic times. Each stage of the cutting, dragging and digging ceremony is accompanied by music played by the "foreman" on his sedge flute, called "puskol", beating the rhythm on a small drum "litlackni". First, the participants ask for forgiveness from the owner of the forest - the god Kiguikolo. They offer the god a ritual treat, cane alcohol and cigarettes. Before cutting, the participants of the ceremony dance around the tree, starting from the east side. Each of them stands in a certain place strictly on the cardinal points. The tree trunk at the same time personifies the center of the universe.

The “foreman” starts cutting the tree, making the first blows with an ax, followed by each of the four dancers, and the inhabitants of the village who have gathered for the ceremony finish. The felled tree is stripped of branches and bark and rolled over the ground on rollers made from branches. Today, a tractor is used for this, but in the old days, the pole was carried so that it did not touch the ground. Previously, they also chose a person who had to spend the night with a cut down tree so that it would not feel lonely.

Today, a tractor is used for this, but in the old days, the pole was carried so that it did not touch the ground. Previously, they also chose a person who had to spend the night with a cut down tree so that it would not feel lonely.

The trunk is dressed, that is, tied with woven vines or ropes that will serve as a ladder, the upper part is prepared to fix the “apple” (a coil that rotates a wooden square frame) on it and a pictla, a small wooden plank, is installed on which the dancers place their feet in a seated position on top of the pole and from which they push off to spin the frame.

Loading

Watch on Instagram

When the pole pit is ready, an offering of tamales, cane alcohol and live chicken or chicken eggs is placed on the bottom of the pit. All this is done to the sound of flute and drum. This is a request for forgiveness to protect the dancers from possible accidents.

As soon as the pole is raised and dug into the ground, a rotary mechanism is installed on it and ropes are tied. Now the pillar is finally ready for the dance.

Now the pillar is finally ready for the dance.

Today, metal poles are often used, so many elements of the ritual are reduced.

Before climbing the pole, the performers dance around to the sound of traditional melodies. First, four dancers rise, and the last is the "foreman" or musician. The “Chief” is also called the flyer because he can stand on top and perform a very risky dance on a very small surface of the reel without any safety devices.

Playing his instruments, the "foreman" beats the rhythm and moves, bowing to all four directions of the world, while standing on one leg. Then he sits on the coil and leans back, remaining on his back facing the sun, to which he dedicates a special song. He speeds up the rhythm, signaling the beginning of the ritual. Four dancers seated at the corners of a square frame lean back and begin to spin the frame. Having descended from it, they spin around the pillar slowly and solemnly, head down, with outstretched arms and legs crossed on the rope that supports them. The sounds of the flute and drum fill everything around, creating a special background for this ceremony. If the audience shows admiration, one of the dancers may arch in the air and touch their legs with their hands. This position requires great effort and can only be used for a short moment.

The sounds of the flute and drum fill everything around, creating a special background for this ceremony. If the audience shows admiration, one of the dancers may arch in the air and touch their legs with their hands. This position requires great effort and can only be used for a short moment.

As the ropes unwind, the circles described by the dancers get wider and wider. When the dancers can already touch the ground with their hands, they do a somersault in the air, stand on their feet and complete their ritual by running in a circle. The "foreman" descends one of the ropes, which are held taut by four dancers. Dancing to the sound of the last tune around the post, the dancers say goodbye.

Loading

Watch on Instagram

The Guaguas dance, which is considered ritual even today, is not surrounded by such rich solemnity. Participants of the ceremony set up a semblance of a windmill. Before using it, the participants in the ritual dance to several different melodies, and their movements are symbolized by the movement of the luminaries across the sky.