How to dance bon odori

Dance the Bon Odori and More at Obon, Japan’s Festival of Souls

Most of Japan is gearing up to celebrate one of its most important holidays: Obon (お盆), or simply “Bon” (the “o-” being an honorific) — a centuries-old, time-honored Japanese tradition that involves honoring one’s deceased ancestors for three days in summer.

Obon in 2022 will begin on Saturday, August 13, and end on Monday, August 15.

Observed in a number of ways — from quietly paying respects to the dead to dancing the Bon Odori in celebration, Obon still has a significant role in Japanese society to this day. Here’s all you need to know about this holiday!

Table of Contents

Obon: A Backstory

Obon has its roots in Buddhism. The story goes that Maha Maudgalyayana (or simply “Mokuren” in Japanese), one of Buddha’s most faithful disciples, discovered that his mother was suffering as a hungry ghost in the afterlife.

By “hungry ghosts,” we don’t mean a spirit that just needs a little nourishment. We’re talking evil, deeply unhappy, and/or neglected ghosts cursed with insatiable hunger. In some types of Buddhism, these ghosts have thin necks but severely distended stomachs, making them unable to eat at all.

But back to Mokuren’s mother. Buddha instructed Mokuren to offer food to her and other hungry ghosts on the 15th day of the seventh month to release them from their pitiful state. Around this time, the gates of the afterlife are said to open, leaving the dead free to walk the earth.

And because no one wants to see their loved ones in pain, people did as Mokuren did, offering food and cementing the Obon tradition and similar festivals in East and Southeast Asia.

When Is Obon?

Obon is observed in July, August, or even September — depending on who you’re asking and which calendar you’re looking at.

The Chinese lunar calendar, which ancient Japan followed for centuries, sets the dates for Obon as the 13th to 15th of the seventh month. But since Japan switched to the solar Gregorian calendar in 1873, there’s no fixed date for Obon across Japan — just like the Tanabata Star Festival.

Some regions celebrate Obon during the Gregorian calendar’s equivalent, which usually falls between August 8 to September 7, while others observe Obon from July 13–15. It’s not very common to see Obon celebrations in September, though. Typical dates for Obon holidays are July 13–15 and August 13–15.

Is Obon A Public Holiday?

No, Obon isn’t a public holiday, though there is one that falls close to it: Mountain Day on August 10. But out of respect for tradition (and to give employees extra holidays), many offices and establishments close for a few days in July or August in observance of Obon.

If you’re visiting Japan from mid-July to late August, we recommend checking in advance that the attractions you plan to visit will be open. As summer is one of Japan’s peak travel seasons, entertainment facilities like theme parks and aquariums typically don’t close for Obon, but shops and restaurants might change their business hours or close for a few days.

How Is Obon Celebrated?

From solemn and private to lively and large-scale, here are the ways that Japanese people observe Obon.

Guiding Lights

Lights play a significant role in Obon, as they’re also used to help spirits find their way home on mukaebon (迎え盆) — the first day of Obon — then to guide them back to the spirit world on okuribon (送り盆), the last day. (Mukae and okuri mean “to welcome” and “to see off,” respectively.)

Families hang lanterns outside their homes to serve as guiding lights, but some areas take this idea further by holding large-scale ceremonies.

Kyoto, for example, sends spirits off with the ritual bonfires of Gozan no Okuribi, better known as the Daimonji Festival. Every year on August 16th, large bonfires forming the shape of kanji characters, a torii shrine gate, and a boat are lit on five of Kyoto’s mountains. The most iconic of the bonfires is the one on Mt. Daimonji, forming the character 大 (dai, “large” or “great”).

Some hold toro nagashi (lantern-floating) ceremonies, in which candle-lit paper lanterns with messages written on them are floated down rivers. In Tokyo, toro nagashi events are held at Chidorigafuchi Moat in late July, and the Sumida River in Asakusa in mid-August.

In Tokyo, toro nagashi events are held at Chidorigafuchi Moat in late July, and the Sumida River in Asakusa in mid-August.

Nagasaki in southern Japan holds a similar festival: the Shoro Nagashi (Spirit Boat Procession), when elaborately decorated boats made of bamboo, grass, or hardened cardboard are sent downstream. While still meant to honor the dead, Nagasaki’s procession is a more lively affair, as people give spirits a send-off to remember with firecrackers, gongs, and loud chants.

Offerings and Spirit Animals

Whether or not your ancestors are hungry ghosts in limbo, a little pampering never hurts. Plus, this holiday is especially for them! Throughout Obon, families leave offerings of incense, food, and flowers on memorial altars at home, and/or their deceased loved ones’ graves. Ritually cleaning gravestones is another common practice.

Along with these offerings, people also decorate altars with cucumbers and eggplants propped up on sticks. These are shoryo uma (精霊馬, literally “spirit horse”) — spirit animals..jpg) The translation in English might be the same, but these are different from the Native American concept.

The translation in English might be the same, but these are different from the Native American concept.

The cucumber and eggplant symbolize a horse and a cow, respectively — spirits’ modes of transportation during Obon. The cucumber horse is slender and moves much faster, so it’s what spirits take to reach our world at the start of Obon.

The eggplant cow moves more slowly but is chunkier, so the spirits can take their time in leaving, while having enough legroom for all the offerings and well-wishes.

Bon Odori and Other Summer Festivals

Many, but not all, summer festivals have something to do with Obon. For instance, while they’re held throughout summer and have since lost the explicit connection to Obon, fireworks festivals tie into the concept of guiding lights. They may be all about putting on the biggest, brightest pyrotechnics shows now, but Japan’s earliest fireworks festivals were originally meant to honor the dead.

In contrast, as festive as Bon Odori dance festivals are, their connection to Obon is hard to miss — it’s in the name! Remember Mokuren from the backstory of Obon? He’s said to have danced with joy after learning that his mother’s suffering was over, starting an entirely new practice: the Bon dance.

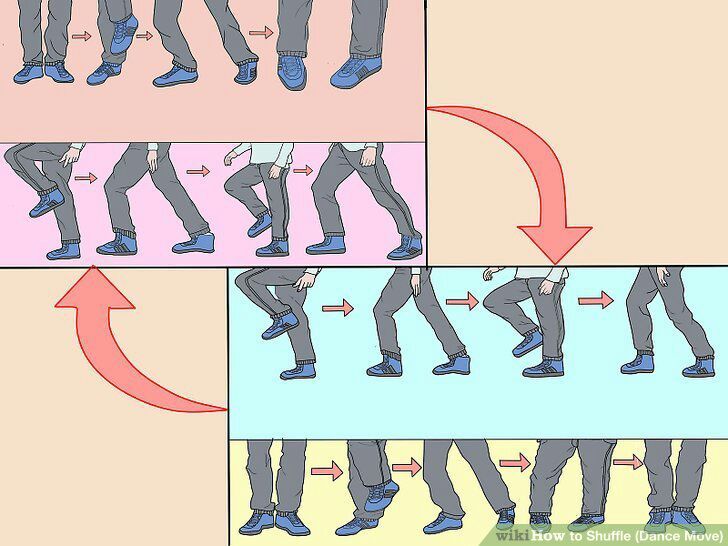

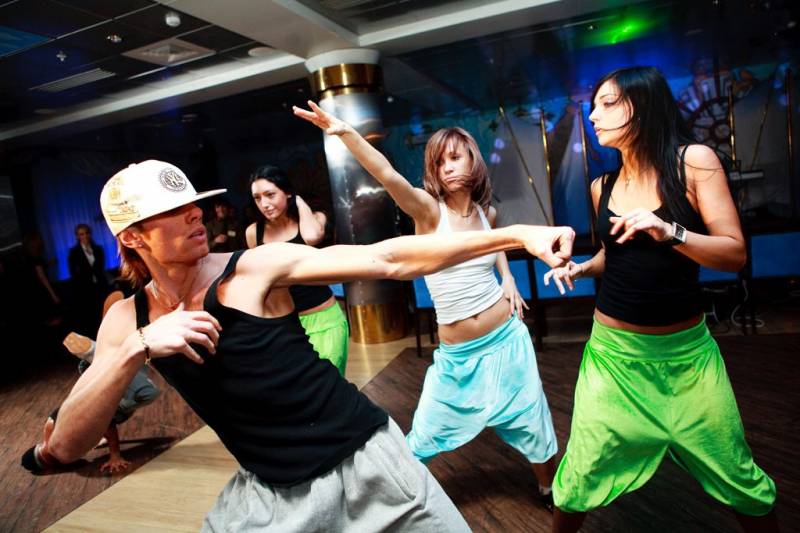

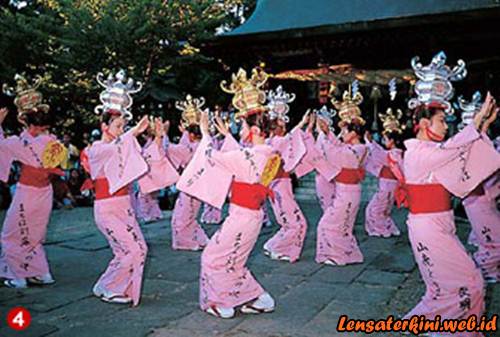

Bon Odori refers to a whole range of dances performed during Obon. These were originally meant to welcome the dead and celebrate their presence. Styles and music used vary across Japan, but the moves are generally simple and fairly easy to learn, so that everyone — even those with two left feet — can join in.

At Bon Odori events, people — typically clad in light cotton kimonos called yukata — gather around a tower-like elevated stage called yagura to dance around it from sundown until night. These festivals usually have lots more going on, like food, booze, and games, but the dance is the main attraction.

Who says traditions don’t evolve with the times? Don’t be surprised to see people dancing the Bon Odori to rock and disco music!

中野駅前大盆踊り大会

— はやとデラロッサ (@hayatodelarossa) August 14, 2018

ボンジョビで踊ってんだけど pic.twitter.com/hdMqLN0hYN

Some regions have their own distinctive versions of the Bon Odori, too. Shikoku’s Tokushima Prefecture is the birthplace of Awa Odori, a dance style that alternates between frenetic and slow, creeping movements.

And, while neighboring Kochi Prefecture’s yosakoi — a lively dance that uses clappers called naruko — isn’t a Bon Odori offshoot, it holds a huge yosakoi dance festival every August, around Obon.

JR Shikoku 3-Day Pass

If you’re really into Japanese dance, nothing beats going to Tokushima and Kochi to see their dance festivals, which take place just days apart from each other. But Tokyo, as well as several other big cities across the country, has its own Awa Odori and yosakoi festivals, too — and they’re also popular in their own right!

Sadly, in-person summer festivals won’t be happening this year, but some organizers have been thinking of holding them online. In the future, if you’re in town for a Bon Odori festival, don’t be shy; just join in and dance the night away!

In the future, if you’re in town for a Bon Odori festival, don’t be shy; just join in and dance the night away!

Ghost Stories for (Literal) Chills

Halloween may now be big among Japanese youths (albeit as a day for dressing up, not for scares), but the original spooky season in Japan has always been Obon. It makes sense: Obon is the time when the dead return to the world of the living, so there are bound to be some unhappy, vengeful spirits in the mix.

Gathering ‘round to tell ghost stories is an Obon practice that’s older than you think. Way back before air conditioning existed, many Japanese believed that ghost stories would give people the chills, therefore helping them beat the summer heat.

They even made parlor games out of this practice — hyakumonogatari kaidankai involves gathering in a dark room, lit only by 100 candles, to share tales of the supernatural. After each story, a candle would be extinguished. Blowing out the last one was said to summon something too frightening for words, so most players would stop at 99 tales.

Today, this Obon custom lives on in the form of haunted houses and other seasonal horror attractions at amusement parks. You might also see horror-themed Obon specials on TV, as well as ghost-story roundups in the media.

Obon in Modern Japan

So what do the Japanese of today do during Obon? Nowadays, most Japanese aren’t religious, though they observe religious customs for tradition’s sake. Many Obon-related festivals are now secular — just because some are held on temple or shrine grounds doesn’t mean that visitors are expected to take part in religious or spiritual rites.

Some treat Obon as a time for returning to their hometowns for a family reunion, but not necessarily to clean deceased ancestors’ graves. Households that don’t observe Buddhist customs may not even celebrate Obon at all!

As mentioned above, this is a peak time for travel. Japanese professionals tend to take vacations at the same time — that is, close to or during public holidays — because they’re usually too busy to take time off otherwise.

As such, it’s become common for young Japanese to travel around or outside the country during Obon. If you’re visiting Japan in summer, expect crowds and long lines at attractions and other establishments, especially around the first half of August.

Roads and expressways will be congested — allow for delays if you plan to travel on the road. Also, hotel rates, airfare, and highway bus prices usually spike around this time, and Shinkansen bullet trains may fill up easily.

If you’re planning to travel via Shinkansen during Obon, it’s best to reserve seats (and luggage storage, if need be) early enough. Otherwise, you can take a chance on non-reserved seating.

Get Unlimited Travel w/ JR Passes

Japan's 3 Great 'Bon Odori' Dance Festivals

Jessica Famularo

FestivalsJapanese CountrysideDanceSummer FestivalsShoryudoAkitaGifuTokushimaYamagata

3.

Nishimonai Bon Odori

Nishimonai Bon Odori https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UuoMoSVRT8A

This Bon dance takes place in the town of Ugo, which was formed by combining the former town of Nishimonai with six surrounding villages in the south of Akita Prefecture. The Nishimonai Bon Odori is composed of just two different dances performed by local residents to the accompaniment of taiko drums, shamisen and wooden flutes (yokobue). The dancers are distinguished by their patchwork kimono, called hanui, which are worn with large, semicircular straw hats called amigasa. Some dancers wear hikosa zukin, black hoods that recall the dead.

Recognized as a National Important Intangible Folk Cultural Property, the dance traces its origins back more than 700 years to a harvest festival initiated around the late 1280s. Following centuries of Onodera rule, in 1601, Onodera Shigemichi set fire to Nishimonai Castle rather than surrender to forces allied with Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was in the final stages of unifying all of Japan under what would become the Tokugawa Shogunate. Beginning that year, his surviving retainers would dance in memory of their former lord. Over time, the two dances merged, becoming the Nishimonai Bon Odori we see today. It takes place from August 16 to 18 every year, with the 18th representing the big finale.

2. Gujo Odori

https://zh.

wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gujo_Odori.jpg

This festival in Gifu Prefecture dates back over 400 years and stretches over 32 nights from July to September. Gujo Odori actually consists of 10 different types of dance, and the festival tours all over the town of Gujo Hachiman, moving from the castle town to city squares, shrines and more. The festival reaches its peak between August 13 and 16, with a host of all-night dance parties that run from 8 p.m. until the wee hours of the morning.

It's said that Gujo Odori originated as a way to create bonds between the different social classes at the end of the Warring States Period (1467-1590), including warriors, traders and craftsmen. Today all are welcome to participate in the event—tourists and locals alike!

1.

Awa Odori Dance Festival

Awa Odori Dance Festival https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0h4-mZLitBQ

Held every August in Tokushima Prefecture, Awa Odori is Japan's best-known dance festival, with spectators lining the streets to catch a glimpse of the dancers who parade the city streets. As they make their way down the road, the dancers chant:

“It’s a fool who dances and a fool who watches.

If both are fools, you might as well have fun dancing.”

踊る阿呆に 見る阿呆

Odoru aho ni miru aho

同じ阿呆なら 踊らにゃ損々

Onaji aho nara odaranya son-son

The festival got its start in 1587 (some sources say 1586) to celebrate the construction of Tokushima Castle in what was then known as Awa Province. Feudal lord Hachisuka Iemasa distributed sake to the townspeople, who got drunk and began to dance in the streets. And that, as they say, is history.

Feudal lord Hachisuka Iemasa distributed sake to the townspeople, who got drunk and began to dance in the streets. And that, as they say, is history.

By day, dancers perform the carefully choreographed "Selected Awa Dance" on stages. When the sun goes down, however, groups of dancers, called ren, perform through the streets of downtown Tokushima, including groups from all over Japan and even overseas. You can catch the festivities from August 12 to 15 each year.

Honorable Mention: Yamagata Hanagasa Festival

While not a form of Bon-odori, the Yamagata Hanagasa Festival, or Hanagasa Matsuri, is one of Tohoku's largest festivals, drawing crowds of over 1 million over the course of three days. This dance fest is fairly new as far as Japanese festivals go, getting its start in 1964, but has quickly become an important annual tradition.

This dance fest is fairly new as far as Japanese festivals go, getting its start in 1964, but has quickly become an important annual tradition.

The festival is named for the straw hats worn by its dancers, decorated with Yamagata Prefecture's signature safflowers. A total of 10,000 dancers flow through Yamagata City's main street, led by a fleet of elaborate floats. Hanagasa-daiko drums provide an upbeat rhythm as both dancers and onlookers shout, "Yassho! Makkasho!" While the festival originally featured technical group dance performances, the celebration now features a wider variety of dance.

The Yamagata Hangasa Festival takes place from August 5 to 7 in Yamagata City proper.

O-Bon festival, bon-odori dance and visiting the graves of ancestors

On O-Bon festival, fires are lit mukaebi , showing the spirits of ancestors the way to their home, making offerings to them and praying for their good posthumous existence. Along with the New Year period and spring holidays, O-Bon is a holiday season when many Japanese travel to their native places to visit the graves of their ancestors and dance the festive dance bon-odori .

Along with the New Year period and spring holidays, O-Bon is a holiday season when many Japanese travel to their native places to visit the graves of their ancestors and dance the festive dance bon-odori .

Tribute to ancestors

Traditions of commemoration of the dead exist in all countries of the world, taking unique forms characteristic of this culture. The Japanese summer festival O-Bon is an annual meeting of the souls of deceased ancestors who come to the house and an opportunity to pay tribute to them.

The dates of this holiday vary depending on the region, but in general it is customary to celebrate au-Bon for four days in August (or in July for the old style). O-Bon begins with the meeting of the souls of the ancestors returning to earth on August 13 and ends with the send-off on the 16th. These days it is customary to visit family graves; in some areas of Japan, the holiday is accompanied by traditional dances bon-odori . Most companies provide their employees with summer holidays - o-bon-yasumi , creating favorable conditions for observing ancient traditions.

In Buddhism, o-Bon is called urabon'e , in Shinto it is bon-matsuri . The source of the holiday was a Buddhist legend about a disciple of Shakyamuni Buddha, who learned about the suffering of his mother in the hell of "hungry ghosts" and decided to save her with the help of a commemoration ritual. The tradition of Buddhism that came from outside harmoniously intertwined with the cult of veneration of ancestors in the spiritual tradition of Japan, and starting from the Edo period (1603-1868), o-Bon has taken a strong place in the life of the Japanese, not inferior in importance to the New Year holidays.

Attributes of the holiday

In order for the souls of the ancestors to safely reach the house, on the 13th, a welcome fire is supposed to be lit at the entrance to the house - mukaebi . Once upon a time, it was a real fire kindled from flax stalks, but modern reality has made adjustments to this tradition as well - many Japanese meet the souls of their ancestors, carefully illuminating their path with the help of stylized electric lanterns.

Mukaebi in Numazu City (Shizuoka Prefecture): Locals light fires on the beach.

To commemorate the dead on the days of the O-Bon holiday, a special home altar is used seryodana , at the corners of which young bamboo branches connected by a rope are placed. Physalis flowers, shaped like a traditional lantern, mimic a welcome fire for returning souls. A wooden tablet with the posthumous name of the deceased is placed on the altar, in front of it are seasonal vegetables and fruits, fresh flowers and two homemade figurines - an eggplant buffalo and a cucumber horse with legs made of flax stalks. It is they who serve as the "transport" that moves the souls of the ancestors during o-Bon. A swift cucumber horse will help you quickly return to your earthly home, and an eggplant buffalo will slowly take the souls who have stayed on earth to another world.

Faithful helpers – cucumber horse and eggplant buffalo (photo ©JIJI Press)

On the 16th, on the day of seeing off the departed, it is supposed to light a farewell fire illuminating the road ( okuribi ). The most famous farewell fire - Gozan no Okuribi (or Daimonji - yaki, bonfires in the form of the character dai - "big") in Kyoto, which has become one of the largest city holidays, attracts many tourists to the city. In some regions of Japan, it is customary to lower boats or lanterns with lit candles down the river, but recently this beautiful tradition has been criticized by environmentalists.

The most famous farewell fire - Gozan no Okuribi (or Daimonji - yaki, bonfires in the form of the character dai - "big") in Kyoto, which has become one of the largest city holidays, attracts many tourists to the city. In some regions of Japan, it is customary to lower boats or lanterns with lit candles down the river, but recently this beautiful tradition has been criticized by environmentalists.

Farewell Lantern Festival in Kinokawa City (Wakayama Prefecture)

Visiting graves

Visiting a cemetery , close to family graves. At this time, it is customary to visit cemeteries, clean up the graves, decorate them with flowers and light candles, paying tribute to departed relatives.

Bon-odori dances

Another element of the au-Bon celebration is traditional dances bon-odori , also intended for meeting, commemorating and seeing off the souls of ancestors. Buddhist temples or city squares can serve as a platform for dancing. Today, bon-odori is far from being only one of the rituals of commemoration of the dead, but also an integral part of summer holidays in various localities. The dancers either gather in a circle, moving in time to the accompaniment of Japanese drums (for example, gujo-odori in Gifu Prefecture), or parade through the streets of the city ( awa-odori in Tokushima Prefecture).

Today, bon-odori is far from being only one of the rituals of commemoration of the dead, but also an integral part of summer holidays in various localities. The dancers either gather in a circle, moving in time to the accompaniment of Japanese drums (for example, gujo-odori in Gifu Prefecture), or parade through the streets of the city ( awa-odori in Tokushima Prefecture).

A traditional dance is not necessarily performed to a traditional tune. According to the survey results of the well-known information site ORICON STYLE, the rating of popular melodies for bon-odori was headed by the song of the peoples of the northern island of Hokkaido studied at school soran-bushi , in second place - often heard at baseball and football matches Tokyo ondo , on the third - a melody from the cartoon about the robot cat Doraemon, the favorite of children.

Dance bon-odori

In South American countries, the word "bon-odori" has entered the lexicon of local residents no less firmly than "sushi" and "karaoke". Every year, in the suburbs of the Argentine city of La Plata, a major event is held with the participation of more than ten thousand people. Dressed in summer clothes yukata , Argentines of Japanese, Spanish and Italian origin dance until late at night, festival guests stroll among countless mobile restaurants and have fun.

Every year, in the suburbs of the Argentine city of La Plata, a major event is held with the participation of more than ten thousand people. Dressed in summer clothes yukata , Argentines of Japanese, Spanish and Italian origin dance until late at night, festival guests stroll among countless mobile restaurants and have fun.

BON ODORI 2013 La Plata

The simplicity and repetitive nature of dance movements bon-odori makes it accessible to any participant, and the summer version of the kimono - yukata - becomes an additional element that allows you to feel involved in the atmosphere of traditional Japan . Round dances to drum music and veneration of ancestors are another link that unites such distant and seemingly different inhabitants of the northern and southern hemispheres of our planet.

Banner photo: bon-odori dance

Photo Credit:

Mukaebi in Numazu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, where locals light fires on the beach. ©Batholith

©Batholith

oh well - frwiki.wiki

There are paronyms in this article, see Aubonne , Eaux-Bonnes and Obón .

For articles of the same name, see Ok.

Dancers Bon odori .

Dancers Bon odori (Jojo-ji).

Tokyo (2014).

O BON (お お 盆 ? ) or just Bon (盆 ? , without honorary prefix) or Hurray Bon - this is the Japanese Buddhist Festival, dedicated to the spirit of the ancestors. O bon has been around for over five hundred years and was imported from China, where it is referred to as "ghost party".

Over the years, this religious holiday has become a family reunion, when people from big cities return to their hometowns and tend to the graves of their ancestors. A dance festival is traditionally held on these three days, Bon odori or " Bon dance". These days are not public holidays, but many Japanese take holidays during this period and some businesses close.

These days are not public holidays, but many Japanese take holidays during this period and some businesses close.

Summary

- 1 History

- 2 symbolic

- 3 Current dates

- 4 rituals

- 4.1 Toro nagashi

- 4.2 good Hatsu

- 4.3 Good odori

- 5 links

- 6 See also

- 6.1 Bibliography

- 6.2 Related Articles

- 6.3 External link

Historical

This Japanese rite has existed for more than five hundred years and was imported from China where it is called the "ghost festival" (Chinese: 鬼節; pinyin: guijie or Chinese: 中元節; pinyin: zhongyuanjie). O bon , however, has undergone Japaneseization, in particular by modeling customs for New Year's celebrations. During the celebration O bon we salute not only the ancestors, but also Sai no kami, the god of the ways. While the Chinese holiday lasts only a few days, Obon usually lasts a month.

Symbolic

O Bon - Snuming from the word Winds / UBBANNA (于 蘭 会 / 盂蘭盆 会 会 " Ullambana " in Sanskrit means "hung upside down in hell". At Blessings , burned by the dead, make it possible to reduce the pain of these souls in pain.

The legend associated with Good, says that Mokuren, a disciple of Shakyamuni, saw his dead mother tormented in the Hungry Ghost Realm, where she paid for her selfishness. Shocked, he went to ask the Buddha how he could save his mother from this realm. The Buddha replied, “On the fifteenth day of July, hold a great festival in honor of the last seven generations of the dead. The student complied with the request and thereby freed his mother. At the same time, he discovered the renunciation shown by his mother and the many sacrifices she made to him. The student, pleased with the mother's release and grateful for her kindness, danced with joy. dance of joy is born Bon odori .

O good time when we remember and thank our ancestors for their sacrifices. According to the calendar, this holiday falls on the month of ghosts, the only time the dead can return to Earth. It is a very popular holiday, although fewer and fewer people are taking the time to return to their hometowns to take care of their family's graves. These three days were for a long time the only public holidays of the year. for workers, which means the only time of the year when they can see their family in the countryside.

Current dates

The O-Bon Festival lasts for three days, but the start date varies in different regions of Japan. It was originally held around 15- day 7- month of the traditional lunar calendar. When this lunar calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar in the early Meiji era, the 29 days were removed to align with the Western calendar, and Meiji Five Years was converted to year 1st th th January Meiji 6.

When this lunar calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar in the early Meiji era, the 29 days were removed to align with the Western calendar, and Meiji Five Years was converted to year 1st th th January Meiji 6.

Regions reacted differently to the adaptation of the old festival date to the new calendar, resulting in three separate periods O bon .

- Shichigatsu bon ( Bon in July), also called " Shin bon ", is based on the solar calendar and is celebrated from ( welcome coupon ) at 15 00115 coupon ) in southern Kanto (Tokyo, Yokohama) and Tohoku. This is the result of a direct transfer from the seventh lunar month to the seventh solar month.

- Hachigatsu bon ( Bon in August), celebrated from 13 to , is the most common (eg Kansai.

..). It is also based on the solar calendar, but the date has been pushed back one month to compensate for the 29-day shift. This compromise between solar and lunar calendars is widely applied and used in many festivals.

..). It is also based on the solar calendar, but the date has been pushed back one month to compensate for the 29-day shift. This compromise between solar and lunar calendars is widely applied and used in many festivals. - Kyu dobro (old good ) is always celebrated on the 15th of the seventh lunar month, the date changes every year. Kyuubon is celebrated in northern Kanto, Chugoku region, Shikoku and the southwestern islands. These three days are not considered public holidays, but people are usually given a day off.

Hachigatsu Week in mid-August is one of the three most important holiday periods in Japan, along with New Year and Golden Week , and is marked by a very intense national and international tourist flow.

Rituals

Lanterns are lit in front of every house to guide the souls of the dead during the day. Some lanterns can be extremely complex, specially made. The most important part of the ritual is the offering of food (rice, vegetables, fruits, cakes, flowers, etc.), which is a symbol of exchange. This holiday, although religious and serious, is an occasion for joyful meetings.

Some lanterns can be extremely complex, specially made. The most important part of the ritual is the offering of food (rice, vegetables, fruits, cakes, flowers, etc.), which is a symbol of exchange. This holiday, although religious and serious, is an occasion for joyful meetings.

Colored lanterns are lit on the graves of ancestors near Hiroshima. The white lanterns belong to those who died between the end of the previous Obon and its beginning.

Night Lanterns are also lit to console the souls of the victims of the atomic bombing.

Choro nagashi

Toro nagashi in Sasebo.

Toro nagashi are small square paper lanterns placed on the water for the last half of the day O bon , and which should guide the spirits to the other world . Inside the lantern, a small candle is lit, which then floats in the river or sea.

Hatsu good

Good Hatsu (or shin good , NII good ) is the name given in good O following the year of death of the relative. Additional rituals are performed during this particular voucher O.

Good smell

Bon odori (盆踊り ? , Literally "dance goodness ") is a traditional dance associated with the festival whose origins date back to the Muromachi period. His style varies in different regions of Japan. This is one of the highlights of the O bon party. Bon odori takes place to remember one's gratitude in connection with one's ancestors.

Originally Bon odori was a folk dance nenbutsu, designed to calm the spirits of the dead. The style of this dance varies from region to region. Different prefectures often have special dances bonodori and their own music. Bon odori from Okayama Prefecture is completely different from Kanagawa Prefecture. The music also ranges from classical to traditional Japanese music such as makko ondo , including recent and even foreign songs.

The music also ranges from classical to traditional Japanese music such as makko ondo , including recent and even foreign songs.

It is believed that this tradition began at the end of the Muromachi period for the purpose of entertaining the people. Over time, the religious significance gradually faded and dances became associated with summer.

Most often, the dance takes place in a temple, on the banks of a river or sea, or in some public place. People usually gather in a circle around a small wooden building called yagura, which is being built by especially for the occasion. In Okinawa Prefecture, instead of bon odori , they dance eisu , whose rhythm is based on percussion.

Recommendations

- (fr) This article is partially or completely taken from the Wikipedia article in English titled "Bon Festival" ( see list of authors ) .

- ↑ a b and c Lawrence Kaye, Feasts and Observances of the Four Seasons in Japan , Presses Orientales de France, 1991.

- ↑ " Good ABC, 2002 " (Archive • Wikiwix • Archive.is • Google • What to do?) .

- ↑ a and b (ru) Fanny Hagin Mayer, Village Festival Calendar: Japan, Asian Folklore Studies , 1989, vol. 48, p o 1, p. 145 .

- ↑ (c) " Obon " at www.japan-guide.com (accessed 4 November 2019) .

See also

Bibliography

- Lawrence Kaye, Feasts and Observances of the Four Seasons in Japan , Presses Orientales de France, 1991.