How to dance bharatanatyam

Guide to Bharatanatyam — Paper Darts

Paper Darts

Fiction

Namrata Verghese

Step One: Tatta Adavu (Tapping)

Tapping is first. Tapping is always first, from the first infinity to the last. Tapping is the crux of dance and dance is the crux of life. Learn to tap, your guru says, and everything else will follow.

That’s why the first thing you learn in dance class is how to count under your breath. “One, two, three . . . beat . . . one, two, three . . .” You have to say it out loud. If you don’t, numbers don’t form fully and rhythm eludes you. Your hot breath mingles with sweat and stale deodorant. “One, two, three . . .” Soon, the numbers slip from your mouth easily and you know the count the way you know the words of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, although you haven’t yet learned how to read.

When your hand remembers the steps faster than you can, your guru pats your back for the first time. Although her figure has bloated with the years, she is a dancer herself. She pretends to wear her curves sensually and knows the value of this moment.

"Congratulations," she tells you. "You’re on your way."

But don’t forget to bend your knees. Make sure your hands are behind your waist and that your palms bend outwards.

Tapping matters. But not as much as you thought it did.

Step Two: Natta Adavu (Stretching)

Stretch. Stretch until your calves ache and quiver, until the balls of your feet feel melded to the rubbery floor. Deviations from focus will wobble you, ground you in the now, and you will lean as the earth leans.

By now, you are a dance veteran. At four, you joined the class with your horde of friends since birth, all smooth feet and curls. Indian parents have a need to push their children: karate for Karans and kathak for Kirans. But as feet grew blisters and hair grew frizzy, your friends started to vanish one by one. Now, it’s just you and five other girls in the dingy gym rented from the local basketball team for one hour every Wednesday night. Five other girls who don’t mind standing on their tippy toes until their nails crumble and peel. Who don’t mind tightening their buns until their heads ache and throb. Who, like you, know that this doesn’t matter. Because when you can tell stories with your eyes and hands, how could anything else matter?

But as feet grew blisters and hair grew frizzy, your friends started to vanish one by one. Now, it’s just you and five other girls in the dingy gym rented from the local basketball team for one hour every Wednesday night. Five other girls who don’t mind standing on their tippy toes until their nails crumble and peel. Who don’t mind tightening their buns until their heads ache and throb. Who, like you, know that this doesn’t matter. Because when you can tell stories with your eyes and hands, how could anything else matter?

Step Three: Visharu Adavu

This is the step where you begin to wish you really were a goddess and not just playing one, so you would have arms enough to accommodate the moves. It’s the hardest part, according to your guru. If you can do this, you can do anything. Balance your arms in the lotus position; they may burn and shiver, but that just means you’re doing it right. Slowly, you realize your hands are no longer part of you—they have a will of their own. After a while, they move to the beat before the instructions reach your brain. They remember the steps faster than you can. You’re impressed and slightly taken aback by this. For the first time, you don’t have to think to dance.

After a while, they move to the beat before the instructions reach your brain. They remember the steps faster than you can. You’re impressed and slightly taken aback by this. For the first time, you don’t have to think to dance.

Today is the first day that your guru pats your back. “Good,” she says, and her smile is not forced. She is a dancer herself, so she knows the value of this moment. You wouldn’t be able to tell if she hadn’t told you, though. Her figure has bloated with the years, although she pretends to wear her curves sumptuously. Her eyes are still the eyes of a dancer, however; they are dark and expressive, like yours should be. Open wide for a smile. Lashes fluttering for femininity. Slanted cheekily for character.

After a year, you can wrap a sari like an expert and shame on you if you haven’t already mastered the art of kajal. Stories are important, your guru says. But you need to look the part as well. After all, Princess Sita would never have been seen with smeared lipstick.

Oh, and don’t forget to smile.

Step Four: Tattimetti Adavu (Balancing)

After the stretching comes the balance. You stand in the same position for so long that you begin to feel twinges in places you didn’t know twinges could happen. Your backside cramps every day, but your mother ices your spine and you harden your mind.

This is the year that your dance class moves out of the gym and into a small, red brick building all to itself, with an official sign and business cards to its name. Suddenly, your guru is more serious about everything. No stray smudges of mascara, no tiny tremors in positions. This is her business now and you are her client. You wonder what happened to the woman your mother used to invite over for tea.

You dance in a studio now. The walls are hospital white and the girls are just shadows on their surfaces. Mirrors are everywhere. There are two, three—too many to count; they must stretch into infinity. There’s a moment, in the middle of a twirl, when you can look at your reflection and lose it before it’s found. You dance against the light beating in those tiny cracks where one mirror ends and the other has not yet begun.

You dance against the light beating in those tiny cracks where one mirror ends and the other has not yet begun.

Step Five: Teermanam Adavu (Ending)

Your guru’s hair is newly cut and highlighted with streaks of light brown, so she has to blow it heavily out of her eyes when she criticizes you now. Illogically, this softens the blow of the insult. “Big smiles,” she reminds you. “This is the happy ending.”

The endings are always happy.

As you pose for the ending, arms raised high in the air, you feel the weight of an invisible book in your hands. If you were to open it, it would shine in the dim light of the stage. It’s hard to read the words inside, but easy to imagine them.

You presume you came from somewhere, but this is all you can remember: the noise of lethargic applause, the dim light, and the watching eyes.

Your mother couldn’t come to watch this show; she is the on-call nurse at the hospital, and your father is away on business in Singapore. Before she dropped you off, she kissed your cheek and told you that you looked like a princess in your costume. You disagree—in a too-big sari that’s tapered in all the wrong places, you look like an upside-down ice cream cone—but you smiled back at her anyway. Now you wait in the parking lot, watching as proud parents hug accomplished daughters and drive off into the hazy afternoon sun.

Before she dropped you off, she kissed your cheek and told you that you looked like a princess in your costume. You disagree—in a too-big sari that’s tapered in all the wrong places, you look like an upside-down ice cream cone—but you smiled back at her anyway. Now you wait in the parking lot, watching as proud parents hug accomplished daughters and drive off into the hazy afternoon sun.

Molting gray pigeons perch on the sidewalk beside your battered flip flops. Their claws scratch words you can’t understand into the dirt. Together, you wait for a new day.

Step Six: Sarikal Adavu (Sliding)

It doesn’t seem logical that you learn to slide after you learn to finish. Your guru tells you that this is because there is a grace to the slide that can only come from experience.

This is a lie, you learn quickly. The slide isn’t an art; it’s a calculation. It translates movements into variables, renders your actions generic to the contours of any form. Your body is linear, the y-axis of a Cartesian plane, and the three points of your head, chest and torso are distributed evenly and vertically. Symmetry matters. Poetry doesn’t.

Your body is linear, the y-axis of a Cartesian plane, and the three points of your head, chest and torso are distributed evenly and vertically. Symmetry matters. Poetry doesn’t.

Your dance is boiled down into degrees of measured space.

Before, school was a temporary station in between dance classes. But the quiet boy two rows down from you in your biology class has changed that. He is like no one you’ve ever seen before, with steely eyes and a face of planes and angles. You admire him the way women admire men who know they are to be admired.

“Everything is dying!” your teacher proclaims excitedly, jolting you out of your daydreams as she tries in vain to hammer the concept of entropy into the brains of summer-ready students.

She’s misunderstood the concept. You know this because you’ve read ahead in the textbook. Everything isn’t dying, it’s simply changing. One state to another. Ice melts, then boils. It is far better to be many things than it is to be one.

Step Seven: Kudittametta Adavu (Jumping)

The final step is the jump. This is a dancer’s pride and joy; this is the step that differentiates mediocre from good, good from excellent. The day you master the jump, your head spins in giddiness. This is it. You are a dancer. It’s done. You know you’ve nailed it because, after a performance, a bird-like woman with bright lip gloss hands you a business card. “Dance is an art,” she tells you. “We need young dancers like you.”

This is a dancer’s pride and joy; this is the step that differentiates mediocre from good, good from excellent. The day you master the jump, your head spins in giddiness. This is it. You are a dancer. It’s done. You know you’ve nailed it because, after a performance, a bird-like woman with bright lip gloss hands you a business card. “Dance is an art,” she tells you. “We need young dancers like you.”

Your guru offers you a tight-lipped smile. “Congratulations,” she says, and for the first time you can remember, her eyes are empty.

After the woman walks away, you pointedly throw the card in the trash, making sure that your guru can see. She pretends that she can’t.

The boy’s name is Alex, and he likes football. You realize the minute he asks you out that it’s a mistake, but you say yes anyway. Sweaty palms. Nervous giggles. You kiss like a rooster; you lost your feathers in the fight. Your eyes must be muted when you paint yourself with papier-mâché.

After you end things with him, you quit dance. Your guru’s eyes betray no emotion, but you can see glimpses of who you used to be reflected in their hollow spaces. Memorize your script and recite it.

Your guru’s eyes betray no emotion, but you can see glimpses of who you used to be reflected in their hollow spaces. Memorize your script and recite it.

On your way out, the darkness of the studio lights up with a blue and red pulse. A heartbeat thuds in the background, but it is not your own. You forget that you must tap to it. Out of the corner of your eye, you think you see the shadow of a woman, a dancer, silhouetted against the wall. Light hits it, and she dissipates. She becomes floating particles in the air. Dust you swallow when you’re struggling to breathe. The room is a riddle; its vacant space is organized into a question. Our answer has already been found and forgotten.

One, two, three . . . beat . . . one, two, three . . .

Namrata Verghese is an undergraduate third-year and Robert W. Woodruff Scholar at Emory University, pursuing a double major in English/Creative Writing and Psychology/Linguistics. Her work has appeared in storySouth, Litro Magazine, NY Magazine, and elsewhere. Her first collection of short stories, tentatively entitled Hyphenated, is forthcoming from Speaking Tiger Books.

Her first collection of short stories, tentatively entitled Hyphenated, is forthcoming from Speaking Tiger Books.

Illustrated by Carson McNamara.

Grin & Shimmy

Do you remember when we lived on the reservation?

Guide to Bharatanatyam

The Possible Causes of Your Suffering

Foreclosure

Castle Island

Standing Profile

Some Day My Princess Will Come

Choose Your Own Adventure: If You Expect Life to Be Easy and Without Pain, Turn to Another Story

0 LikesPaper Darts

Paper Darts

Latest Article

Follow Us

@tudorinsidestyle

Ads can be placed here

The araimandi debate in Bharatanatyam

The dance world is obsessed with araimandi — from teachers and students to critics. But this is not really a new obsession. The ardhamandali or the araimandi stance, with bent knees turned out and body lowered, central to most Indian dance styles, has been around for centuries. And there’s evidence of it in sculptures and texts across India. The question is how much is enough.

But this is not really a new obsession. The ardhamandali or the araimandi stance, with bent knees turned out and body lowered, central to most Indian dance styles, has been around for centuries. And there’s evidence of it in sculptures and texts across India. The question is how much is enough.

According to scholar Dr. V. Raghavan, texts have provided specifications regarding the mandala, in which the feet form a rhombus. ‘The Sanskrit text Nrttaratnaavali (1253 AD) calls this Kharvataa and mentions 12 inches for this lowering; the Tamil text of Aram Valarthu Nadhanaar (Bharata Siddhaantam) says that if you measure the distance from the nose to the naval and measure the inside distance between the two knees bent in mandala, the two should be equal.’

As any practitioner will tell you, the dance style causes heel, knee and back pain. There is a study published in Indian Anthropologist (1998) by Joyce Paul and Satwanti Kapoor that says 35% of the Bharatanatyam dancers surveyed (a small sample of 70) seem to have had injuries caused by dancing, the knee being the most affected. They blame the araimandi, equating it to the demi-plie of ballet, which is known to cause injury. They observe that the dancers with limited external rotation at the hip are the ones most affected. Kuttanam, the forceful stamps, and the cement or stone practice floors are the other culprits.

They blame the araimandi, equating it to the demi-plie of ballet, which is known to cause injury. They observe that the dancers with limited external rotation at the hip are the ones most affected. Kuttanam, the forceful stamps, and the cement or stone practice floors are the other culprits.

Dance or dancer?

Who is at fault? The dancers or the dance style? The authors of the study argue that since the dance tradition goes back 1,500 years, the principles of yoga would have been taken into consideration, but not the principles of anatomy and modern-day physiology. They also say that the structure, ‘rather than being based on functional anatomy, lays its foundation on the aesthetic beauty of lines and angles formed by the varied positioning of angas or the different parts of the body.’

A similar opinion is expressed by scholar Kapila Vatsyayan in her book, Indian Classical Dance , “The Indian dance is not concerned with the musculature of the human form, but rather, like the sculptor, takes the joints and fundamental anatomical bone-structure of the human form as its basis. ”

”

Veteran Bharatanatyam exponent Vyjayanthimala Bali

Dancers who have had the privilege of working with nattuvanars, the traditional repositories of Bharatanatyam, disagree that the dance style may be flawed. Vyjayanthimala Bali (disciple of Vazhuvoor Ramiah Pillai, K.P.Kittappa Pillai and K.N.Dhandayuthapani Pillai), Nandini Ramani (disciple of Kandappa Pillai, T. Balasaraswati and K. Ganesan) and Alarmel Valli (disciple of Pandanallur Chokkalingam Pillai and Pandanallur Subbaraya Pillai) emphasise the hours of practice that prepare the body. Lakshmi Viswanathan (disciple of Kanjeevaram Ellappa Pillai) says that though the nattuvanars ruled with an iron rod, they had a knack of teaching each dancer according to her ability. Nritta was not given the importance it is given now, varnam korvais were measured and brief, and the jatiswaram was slow and perfect.

Slow and steady

In the Kandappa Pillai-Balasaraswati style, the basic course was three-four years long. Nandini says, “Araimandi was very important. The focus was first on nritta. We had more than 100 adavus, and we used to practise them in three speeds, from Monday to Saturday for two hours or more. It started with footwork. It took more than a year for arm movements, kai , to be allowed. We considered it an achievement. It was a gradual way of training; we were never overfed or spoon-fed. Unless you have gone through this kind of training, the shaping of the body will not happen. I feel heel or back pain is mainly due to inappropriate or wrong posture from the beginning.”

Nandini says, “Araimandi was very important. The focus was first on nritta. We had more than 100 adavus, and we used to practise them in three speeds, from Monday to Saturday for two hours or more. It started with footwork. It took more than a year for arm movements, kai , to be allowed. We considered it an achievement. It was a gradual way of training; we were never overfed or spoon-fed. Unless you have gone through this kind of training, the shaping of the body will not happen. I feel heel or back pain is mainly due to inappropriate or wrong posture from the beginning.”

Nandini Ramani

Vyjayanthimala echoes the importance of training. “We didn’t leave out a single detail,” she says. In the Thaiyya Thai set, we practised all 10. We had 72 adavus. The adavu foundation with araimandi, the muzhumandi to araimandi movement, straight elbows without sagging, all were important. I was a good student and Guru Kittappa was happy with me. I would not sit down or drink water during practice. I would dance in front of the mirror to get it right. Adavu sutham and anga sutham were most important. Laya also — the salangai and the talam had to go together, the mridangam would follow the feet.’

I would dance in front of the mirror to get it right. Adavu sutham and anga sutham were most important. Laya also — the salangai and the talam had to go together, the mridangam would follow the feet.’

Alarmel Valli has additional learnings from her gurus. “Guru Chokkalingam taught us the contrast between force and lightness and power and grace. For the Paichal Adavu, he would say, when you take off it should be forceful, but your landing should be like a flower falling. You cannot find these aesthetic principles in books; only the repositories of this culture were able to transmit it to their students. They taught us body-friendly principles and wove certain safeguards into the technique. To perform a margam, I would practise for 90 minutes to build up stamina. This is more important than rehearsals.”

Recalling how dancers of an earlier era like Pandanallur Jayalakshmi danced through the day eating only pazhedu (fermented rice), Valli says they consecrated their lives for dance. “I have danced for 50 years on a cement floor, both in the dance class at Egmore and later, when Subbaraya Pillai sir came home to conduct classes. While I did have spondylitis, I never suffered any debilitating injuries or pain that kept me from doing justice to the dance. This was definitely thanks to the footwork technique imparted by my gurus, of striking the floor mainly with the front of the feet. The resultant sharper, more cadenced sound was generated from the hollow of the feet rather than the heels. This emphasis on the use of vallinam and mellinam, or light and shade in footwork, spared me major knee and spinal injuries.

“I have danced for 50 years on a cement floor, both in the dance class at Egmore and later, when Subbaraya Pillai sir came home to conduct classes. While I did have spondylitis, I never suffered any debilitating injuries or pain that kept me from doing justice to the dance. This was definitely thanks to the footwork technique imparted by my gurus, of striking the floor mainly with the front of the feet. The resultant sharper, more cadenced sound was generated from the hollow of the feet rather than the heels. This emphasis on the use of vallinam and mellinam, or light and shade in footwork, spared me major knee and spinal injuries.

C. V. Chandrasekhar

“For the araimandi, we were taught to position the feet in a wide, obtuse angle, a wide V, rather than as a straight line, at a full 180 degrees. The knees, however, had to be open and turned well outwards. This helped us maintain the araimandi stance more comfortably, without undue pressure exerted on the heels to maintain balance. I remember my Guru, Chokkakingam Pillai, saying that very high arches were not conducive to the kind of stamping that Bharatanatyam calls for. I too have noticed in my classes that often students with high arches suffer pain in the ball of the foot. I have low arches myself and I feel it has been beneficial.”

I remember my Guru, Chokkakingam Pillai, saying that very high arches were not conducive to the kind of stamping that Bharatanatyam calls for. I too have noticed in my classes that often students with high arches suffer pain in the ball of the foot. I have low arches myself and I feel it has been beneficial.”

Valli too developed a heel injury, but that was only after active practice on a cement floor for 25 years. Given her busy performance schedule, the dancer, besides taking up a healing yoga routine, wore a skin-coloured cotton sock on her left foot with the toes cut off for better traction.

“Fortunately, no one noticed. You have to practise with the right kind of technique. Imbalance leads to stress and injury, as also mental stress. Of course, we had a much more leisurely and contemplative life without the tyranny of social media,” says Valli.

The one technique that was emphasised in Kalakshetra according to Professor C.V. Chandrasekhar and Jaya Chandrasekhar was to tuck your bottom in (they called it the dhobi bundle), important for body centring and putting less pressure on the knees. The reasoning is that if we lean forward we can sit more, but this leads to wrong weight distribution. Incidentally Kalakshetra’s old campus in the Theosophical Society campus had mostly mud floors in its cottages.

The reasoning is that if we lean forward we can sit more, but this leads to wrong weight distribution. Incidentally Kalakshetra’s old campus in the Theosophical Society campus had mostly mud floors in its cottages.

With the passing away of most of the old-school nattuvanars, we have lost a part of history and an irreplaceable knowledge bank. It would be a good idea to try and collate their philosophies while also establishing a standard body strengthening protocol to assist dance training. It could be based on yoga. Any takers?

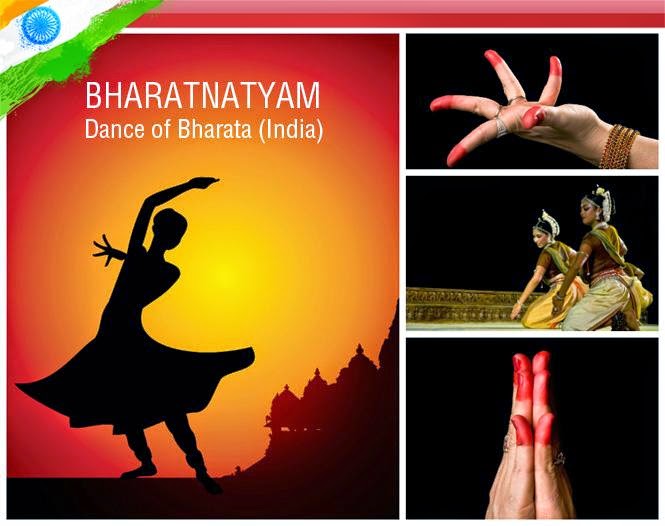

Indian dances: what are they? Bharatanatyam | The world around us

There are dances that are among the oldest in the world, these are Indian classical dances. They are usually divided into styles, traditionally subdivided into eight main ones.

There are dances where every movement of a finger, every movement of an eyebrow, not to mention arms and legs, is all geometrically verified and of great importance. First of all, because these dances have a sacred character. Facial expressions and gestures, an impeccable sequence of poses and a dance pattern - everything is strictly defined and subject to the plot.

First of all, because these dances have a sacred character. Facial expressions and gestures, an impeccable sequence of poses and a dance pattern - everything is strictly defined and subject to the plot.

These dances include all the classical dances of India, and perhaps the most famous of them is Bharatanatyam (sometimes written separately: Bharata Natyam). It translates as “feelings-music-rhythm-dance-theater”, all together, such a multifaceted art form. And all the classical dances of India are considered somehow connected with yoga, as well as with ancient Hindu symbols, historical legends.

In India, in the south of the country in Tamil Nadu, in one of the main "chakras of the world", as they sometimes say, there is a city with a temple complex - Chidambaram , it is also the city of the dancing god, it is there that Shiva dances his space dance. Pilgrims flock to Chidambaram, tourists visit, sacred festivals are held there all year round, and you can talk about it endlessly (you can watch the video in the comments).

Pilgrims flock to Chidambaram, tourists visit, sacred festivals are held there all year round, and you can talk about it endlessly (you can watch the video in the comments).

The Bharatanatyam dance is associated with this temple complex. The dance originates from there and is inspired by the sculptures of the temples. And vice versa, many sculptures have incorporated elements of the most ancient dance culture.

In addition to the gods, demigoddesses can also be seen. These are the apsaras, the celestial dancers. Figurines and bas-reliefs of Apsaras can be seen throughout Indochina. Apsaras danced, often seduced ascetics, and were the wives or lovers of the Gandharvas - demigods, singers and musicians. Sometimes Apsaras and Gandharvas are compared with ancient Greek nymphs and centaurs. In India itself, there has always been a deep connection between different types of art - music, poetry and literature, dance, drama, painting, sculpture. And that deep connection continues to this day.

In India itself, there has always been a deep connection between different types of art - music, poetry and literature, dance, drama, painting, sculpture. And that deep connection continues to this day.

The Bharatanatyam dance itself is given a certain age - 5000 years. The south of India turned out to be a reserve for dance, thousands of years of tradition remained intact. It is difficult to judge the age of the dance, but its figures are described in the oldest Tamil treatises. Temple dancers danced - devadasi - "God's slaves", Western tradition gave them the name "bayadere" (from Portuguese - dancer). Devadasis served in temples, performed the prescribed rituals, and danced. There was often a sexual aspect to the life and work of the temple dancers, but the sacred dance remained a sacred dance—it was a divine dance in the truest sense of the word. (The Devadasi system was abolished in India only in 1988 year. However, the government is aware that the devadasis have not disappeared, although their role has changed somewhat).

However, the government is aware that the devadasis have not disappeared, although their role has changed somewhat).

So, a girl is dancing, most often solo. In other cultures and traditions, men may also dance. This dance can also be regarded as a dance of fire. The movements themselves often resemble dancing flames - a celebration of the universe through a celebration of the beauty of the material human body. The whole universe is the dance of the supreme dancer Nataraja, that is, the Hindu god Shiva. After all, it was the supreme deity who transferred the ability to this dance to people.

It is said that there are no more than two hundred skilled performers of this dance all over the world. Those who understand this dance are also few, because you need to know the meaning of each gesture. Nevertheless, there are also enough people who want to learn the basics of this dance, no longer in a sacred, religious sense, not in the glorification of the dancing Shiva, but in the “pure” form of an ancient, beautiful (albeit exotic for a European) dance. In popular culture, Bharatanatyam has already been widely adapted in both film and television programs around the world.

Nevertheless, there are also enough people who want to learn the basics of this dance, no longer in a sacred, religious sense, not in the glorification of the dancing Shiva, but in the “pure” form of an ancient, beautiful (albeit exotic for a European) dance. In popular culture, Bharatanatyam has already been widely adapted in both film and television programs around the world.

There are a lot of people who want to join the "revival" of classical Indian dances. There are academic and commercial institutions in different countries, the training takes several years. Nevertheless, the popularity of the ancient Indian dance is growing. Moreover, there is also a "pure dance" - the so-called nritta - abstract, but coordinated movements, dance as such , without a clear designation of the plot.

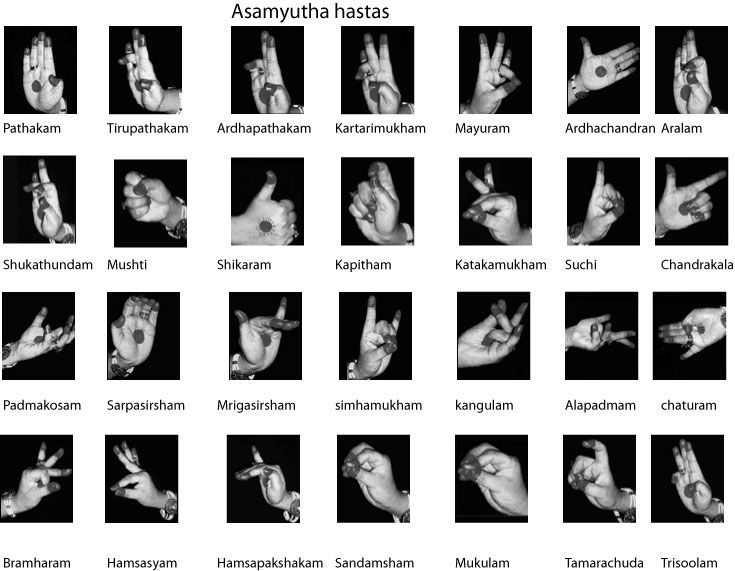

And it's not easy to dance. Among other things, you need to learn a huge number of movements and understand their meaning. Learn to express feelings “in Indian way” (love, joy, peace, sadness, fear and surprise, anger and even heroism). You need to learn how to convey these feelings not only with the help of choreography, but also filigree and subtly - through "small" movements of the head, neck, eyebrows and eyes (only the latter can be from 8 to 36). After all, Bharatanatyam is both pantomime and theater at the same time. You need to learn every hand movement (and they represent completely different), combinations of leg movements, you need to hear the music and understand the terms in Tamil and Sanskrit (and these terms cannot be simply interpreted). Lots of stuff needed...

Among other things, you need to learn a huge number of movements and understand their meaning. Learn to express feelings “in Indian way” (love, joy, peace, sadness, fear and surprise, anger and even heroism). You need to learn how to convey these feelings not only with the help of choreography, but also filigree and subtly - through "small" movements of the head, neck, eyebrows and eyes (only the latter can be from 8 to 36). After all, Bharatanatyam is both pantomime and theater at the same time. You need to learn every hand movement (and they represent completely different), combinations of leg movements, you need to hear the music and understand the terms in Tamil and Sanskrit (and these terms cannot be simply interpreted). Lots of stuff needed...

Of course, it is not necessary for all of us to urgently learn classical Indian dances. Although, for fun, you can learn a couple of gestures or movements and one day express your feelings "in Indian style. " Say, husband or lover. The same love, joy, peace, sadness, fear and surprise, anger and even heroism. No, admiration is better. We'll see how it goes.

" Say, husband or lover. The same love, joy, peace, sadness, fear and surprise, anger and even heroism. No, admiration is better. We'll see how it goes.

And if we don't learn how to dance Bharatanatyam, nothing bad will happen to us. We would like to restore our own somehow. But at least there is hope that Indian dances themselves will no longer seem meaningless to us. They are very meaningful: not only every “phrase of the body”, but even the look of a dancer (dancer) tells a connoisseur a lot.

To be continued…

Tags: traditions, India, art, dancing, culture, history

|

About studio Bharatanatyam Indian folk dances News Photo gallery

| bharatanatyam Classical Indian dance tradition in India for over 2000 years. The history of the style is centuries old, however, one can reliably trace how it looked to the depth of three or four centuries. During this time, the terms, movements, and performed numbers, content, the musical component also changed and developed along with the style. The style was born and changed on the territory of such modern states as Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, which at one time were part of one South Indian kingdom, ruled by the Pallava and Chola dynasties, and today, since over time these states have their own local varieties of dance, the style is considered to belong to state of Tamil Nadu. The name of the style can be translated as Indian dance (Bharata - one of the names of India, natyam - dance) or Bharata dance - Bharata is named by the author of the treatise Natya Shastra. Also one of the interpretations - by syllables - Bha-bhava - feeling, Ra - raga - music, ta - tala - rhythm. This name was given to the style during the revival of Indian culture, followed by the liberation of India from the power of the English colonialists. The dance was originally performed in temples by devadasi dancers (maidservants of the god). At the temples, there were entire villages of dancers, and the parishioners of the temple often gave their daughters to the servants of the temple. During the heyday of culture, there were up to 400 devadasis at the temples. If the ruler liked the dancers of the temple, then individual dancers or their entire villages, and the temple itself were honored with gifts, the names of many dancers are immortalized in records on the walls of temple complexes. Devadasi dances served a variety of functions. The devadasis themselves were considered the wives of the temple deity, so one of their duties was to entertain the temple deity by dancing for him. Also, the dancers performed their numbers during the festivals, when the temple deity (often in the temple for this there is a special leaving "murti" - the image of the deity) was taken out of the temple on a chariot, accompanied by a procession of musicians, brahmins, dancers and believers. There were also families of singers and musicians who kept the South Indian classical style of Carnatic music - which was also an accompaniment for the Sadir dancers. From such a family of musicians came such famous Sadir reformers as the Tanjore Quartet - four brothers, court musicians under the Chola rulers, who made a great contribution to the codification of dance, in which many features of the dance that we know today appeared (adavu - dance elements, "bricks "the technical component of the dance," margam "- a dance performance program containing dance numbers that are different in complexity and content). With the arrival of the British colonialists in India and with the gradual impoverishment of the rulers, there was also a general decline in culture. Sadir did not escape this fate either. It was revived and restored during the struggle for the independence of the Indian people. We know such names of fighters for the revival of dance as Krishna Iyer (a South Indian lawyer who, in order to draw attention to this type of art, not only arranged evenings of South Indian classical art, but was also a dancer himself), Rukmini Devi Arundale - a Brahmin girl who married Englishman, and actively fought for the revival of art, the restoration of its reputation in the eyes of Indian society. Rukmini Devi began to study style quite late - at the age of 25, and soon organized the Kalakshetra Dance Institute, which became the first center to spread the national heritage (dance, music, crafts) in reborn India. Many researchers searched for dancers and teachers who continued to preserve the art despite the neglect of society, so today there are many schools within the style. The Kalakshetra sub-style was formed at the Kalakshetra Institute of Fine Arts in Chennai. Its founder, Rukmini Devi, trained in the Pandanallur style, refining it and introducing strict and rigid rules in both movements and repertoire, establishing a fairly high degree of stylization that the school has kept unchanged for many decades. Also under Rukmini Devi, the modern costume for the Bharatanatyam dance developed, which she developed together with European tailors - the costume is a stylized image of a sari, exquisitely draped on the dancer. During the existence of the school, many of its students became famous performers, many of them founded their own schools. These are such famous names as Leela Samson, the Dhananjayanov couple, Professor Chandrashekhar and many, many others. Pandannalur sub-style - different teachers emphasize different features of this style in their own way - some emphasize the naturalness and depth of abhinai-pantomime, others emphasize the complexity, clarity and jumpiness of the technical aspect - in the case of Pandanallur, it will be difficult for a modern viewer to draw a conclusion about its features , seeing one or two of its performers, as being passed along the chain from teachers to the next generation of performers, it inevitably changes, reflecting the abilities, talent and preferences of each next performer in an endless teacher-student chain. |

The history of dance is usually counted from the period of creation of the Natya Shastra. - a treatise on drama and music, many of the rules and requirements for dance of which are still applied in dance. The author of the Nayatya Shastra is considered to be the holy sage Bharata, whose life is attributed to the period from 200 BC. before 200 AD Of course, it is impossible to say with certainty what the dance looked like even a thousand years ago. Only records of dance in South Indian literature have come down to us, images of dancers on the walls of temples, records in temples of dancers. However, it can be argued that many of the features of the dance, which he acquired many centuries ago, have been preserved and continue to form the basis of the diversity of the classical styles of India. Over the centuries, the styles of each region have improved, more and more new movements, images and techniques have appeared in the dance. In South India, several styles of performance have developed, and one of them is Bharatanatyam.

The history of dance is usually counted from the period of creation of the Natya Shastra. - a treatise on drama and music, many of the rules and requirements for dance of which are still applied in dance. The author of the Nayatya Shastra is considered to be the holy sage Bharata, whose life is attributed to the period from 200 BC. before 200 AD Of course, it is impossible to say with certainty what the dance looked like even a thousand years ago. Only records of dance in South Indian literature have come down to us, images of dancers on the walls of temples, records in temples of dancers. However, it can be argued that many of the features of the dance, which he acquired many centuries ago, have been preserved and continue to form the basis of the diversity of the classical styles of India. Over the centuries, the styles of each region have improved, more and more new movements, images and techniques have appeared in the dance. In South India, several styles of performance have developed, and one of them is Bharatanatyam.

Previous style names - Dassiattam, Sadir.

Previous style names - Dassiattam, Sadir.  At the temples, there was also an institution of nattuvanars - male teachers who taught and trained dancers, as well as accompanying dancers during a performance. Many rulers were patrons of temples, science and arts, sometimes they themselves were also the authors of poetic or musical works, sometimes they also danced. Gradually, the dance went beyond the temple, and court rajadasi dancers also appeared.

At the temples, there was also an institution of nattuvanars - male teachers who taught and trained dancers, as well as accompanying dancers during a performance. Many rulers were patrons of temples, science and arts, sometimes they themselves were also the authors of poetic or musical works, sometimes they also danced. Gradually, the dance went beyond the temple, and court rajadasi dancers also appeared.

The most famous of them are the substrata of Kalakshetra, Pandanallur, Vajuvur, Thanjavur and a number of others.

The most famous of them are the substrata of Kalakshetra, Pandanallur, Vajuvur, Thanjavur and a number of others.