How to cooking dance

Everything You Need to Know About Doing the Cooking Dance

Now that Lil B's signature dance has proved its staying power, it's time to crank some Cooking Music and make sure your wrist game reaches its full potential.

Chris Schonberger

There have been many food-themed dance crazes through the ages, from the Mashed Potato to the Peppermint Stick. But none captures the joys of culinary creativity as fully as the cooking dance, a trend that can be traced back to rapper and Internet legend Lil B (a.k.a., the Based God).

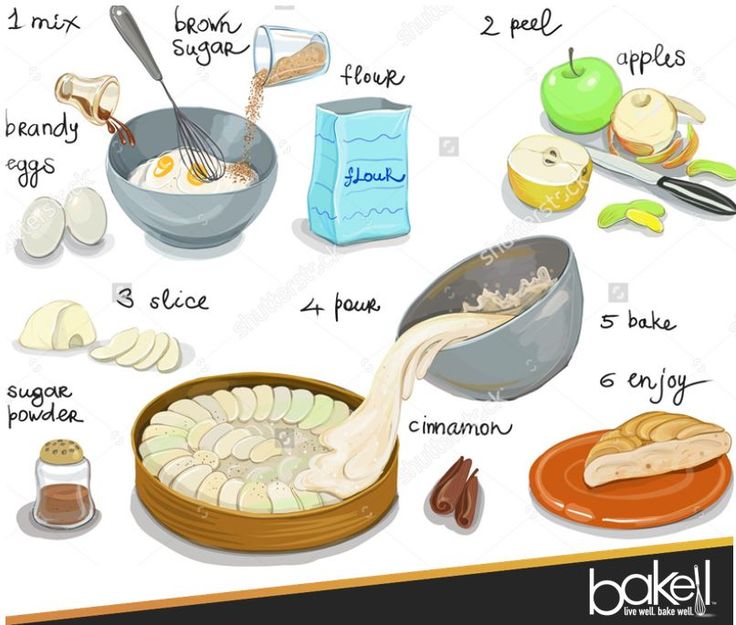

Lil B refers to many of his songs as Cooking Music, and they’re helpfully labelled as such on his YouTube page. These songs provide the ideal soundtrack for the cooking dance, which essentially involves simulating various kitchen maneuvers—whipping a pot, putting a tray into the oven, spooning food onto a plate—to the beat of the music. Part of the fun is trying to figure what, exactly, the dancer is imagining he’s doing while performing each move. Pounding out a schnitzel? Slicing pineapple of the top of an al pastor spit? Plating a modernist dessert?

After the Based God set the table, the cooking dance exploded as a viral sensation around 2011, starting with amateur YouTube videos and spreading to athletes and other celebrities who busted it out as shorthand for cultural savvy. But what’s most remarkable is it’s longevity—from Little Leaguers to the Aubrey “360 with the wrist” Graham, people have embraced the simplicity of the dance and transformed it from a flash-in-the-pan meme to something far more powerful.

Here at First We Feast, we believe there should be more dancing in the food world. Why don’t more “rock star” chefs have rock star moves when they’re tweezering microgreens onto a plate? And why don’t more restaurants have impromptu 50 Cent dance breaks like Ricardo’s Steak House in East Harlem?

If you love the kitchen and you love to dance, the cooking dance is for you. Here’s what you need to know to master the art.

There are only two appropriate things to say while doing the cooking dance.

One is “let that boy cook.” The other is “swag.”

Garish, impractical jewlery will only enhance your chances of cooking-dance success.

Soulja Boy, tell ’em.

You can flaunt your cooking cred by incorporating moves from your favorite celebrity chefs.

Emeril was doing the cooking dance long before Lil B uttered his first “swag,” tbh.

The cooking dance is appropriate for celebrating life’s triumphs, like scoring a goal in an international soccer matches…

Spread the cooking gospel to the world.

…or scoring a touchdown.

NFL Sundays are practically dancing feasts.

The most important ingredient you can bring to the dance is energy.

Don’t limit yourself to the cooking music of Lil B.

It is acceptable to do the cooking dance while holding actual food.

Some fine Internet denizens have created these GIFs to demonstrate.

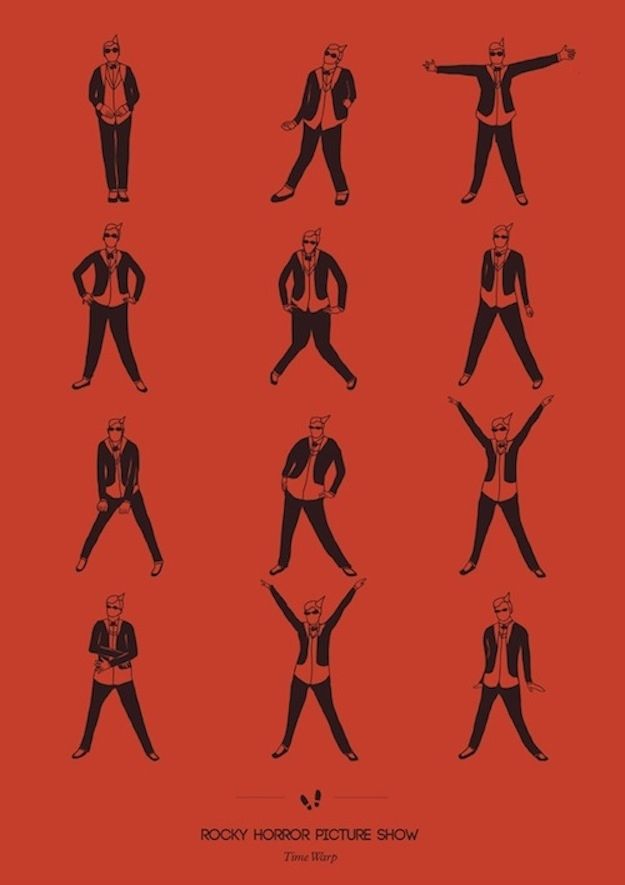

When possible, coordinate your cooking with friends.

Every chef de cuisine of dancing could use a sous chef.

Or a whole

brigade of sous, sauciers, and chefs de partie.The VCU men’s basketball team shows us how it’s done.

When in doubt, look to the Based God.

Don’t forget that eating is a part of cooking.

This move is particularly good for beginners with no rhythm.

Remember that the cooking dance is sort of about drugs, but it’s okay.

When 2 Chainz said he “made a million, off a dinner fork,” he wasn’t talking about making soufflés. He was talking about cooking crack. When visualizing your own cooking dance moves, you should probably focus on motions you’re more familiar with, like beating Betty Crocker brownie mix.

He was talking about cooking crack. When visualizing your own cooking dance moves, you should probably focus on motions you’re more familiar with, like beating Betty Crocker brownie mix.

Keep it G-rated.

C’mon, Nicki—the cooking dance is for the kids!

Tags

- Lil B

Sign Out

Dance and Cooking : An Intersection | by Richard Mazza

Horton technique has a deep and rich history, leaving those studying it with a long list of important aspects to contemplate in relation to their development as Horton dancers. What is a Horton dancer? Lester Horton intended for his technique to develop a dancer in a universal way, preparing them for any style of movement they wished to perform. So, anyone who has taken a Horton class can be considered a Horton dancer. This wide applicability of technique is not only isolated to the world of dance. Horton technique consists of both literal and metaphorical applications of its core concepts in the pedestrian world around the studio.

This wide applicability of technique is not only isolated to the world of dance. Horton technique consists of both literal and metaphorical applications of its core concepts in the pedestrian world around the studio.

Recently I began cooking at home 4–6 times a week. This new hobby sprouted from a fiscal pragmatism but has developed into a love of ritual. Terms like cooking are packed full with infinite fractals of action, feeling, idea, and more; cooking and dancing have this characteristic of endless explorability in common. Comparing cooking and dancing, for my purposes, would be too vague. Instead, I hope to compare the style of cooking I have begun exploring in relation to one of the many core concepts in the Horton training technique.

First, let me explain a bit of what my cooking style has developed into over the last 23 years. My journey is best described by the first meal I ever made, buttered sourdough toast. To my surprise this is many children’s first culinary creation. It is simple, and relatively difficult to make a mess of. If any aspect of the meal can be considered the most important it would be the toasting of the bread. The entire aesthetics of the creation depend on the ability of the creator to wield the power of transformation wisely. In this first homemade meal at age 5 I began to toy with one of the most powerful tools of Horton technique. Transforming is inherent in all cooking, whether it is transforming foods via heat, water, air, or some other technique transformation is inescapable. The same can be said with Horton. In dancing this way both the physical and nonphysical are transformed.

It is simple, and relatively difficult to make a mess of. If any aspect of the meal can be considered the most important it would be the toasting of the bread. The entire aesthetics of the creation depend on the ability of the creator to wield the power of transformation wisely. In this first homemade meal at age 5 I began to toy with one of the most powerful tools of Horton technique. Transforming is inherent in all cooking, whether it is transforming foods via heat, water, air, or some other technique transformation is inescapable. The same can be said with Horton. In dancing this way both the physical and nonphysical are transformed.

Dancing can be broken down into two categories, the physical and nonphysical. There is the act of dancing with a body which is very physical. There is the memory of seeing a performance or dancing a performance which can be decidedly nonphysical. Most actions or thoughts about a dance performance can slide into either category. This slide between the two is often caused by time: from physical to nonphysical or vice versa due to a transformation. When I began training in Horton I remember lacking a certain physical strength. At the time I had no idea what it was, but it was a clear physical lack of power. Now, I have transformed. Not only does my body posses a much larger grouping of muscles in its core and lower back, but I also have transformed to understand nonphysical concepts like opposition, shape, and clarity in a way that without them just the physical transformation alone would not be enough to dance the way that Horton technique demands.

When I began training in Horton I remember lacking a certain physical strength. At the time I had no idea what it was, but it was a clear physical lack of power. Now, I have transformed. Not only does my body posses a much larger grouping of muscles in its core and lower back, but I also have transformed to understand nonphysical concepts like opposition, shape, and clarity in a way that without them just the physical transformation alone would not be enough to dance the way that Horton technique demands.

The beauty of concepts as vast as physical and nonphysical is that they often apply to many things, my style of cooking can also be broken down into these two categories we broke Horton into categories. My transformation as a cook has been filled with immense pleasure. With cooking there is an instant gratification that is hard to translate to dancing. When you finish cooking something you get to eat, which is an apex experience. Eating however, can be achieved without cooking. So the act of eating something you cooked is distinctly satisfying. Similarly, the act of seeing a dance and performing a dance offer related but different experiences of satisfaction.

Similarly, the act of seeing a dance and performing a dance offer related but different experiences of satisfaction.

Learning the many techniques of transformation is where the connection between dancing and cooking is at its height. In cooking there are: endless knife techniques for preparation and presentation, layering techniques to develop aesthetics and flavor complexity, most importantly there is a technical aspect to flavor itself! In Horton there are: specific positions of the body like flat backs, spatial awareness and being able to navigate space effectively, as well as a technique to the pride you utilize while dancing. Overall, the final examples of each list seem to dominate the others. The techniques of both pride and flavor offer interesting similarities. Both are requites for satisfaction in both production and consumption of dance and food. However, what is more fascinating than their necessity is their crossover in application. This is meant to say that in order to the food you cook to work you need pride in serving it both to yourself and others. Also Horton doesn’t seem effective if you don’t have the flavors right.

Also Horton doesn’t seem effective if you don’t have the flavors right.

Flavor only has five columns: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. The challenge of ascribing flavors, which are usually reserved for the senses in the mouth and nose, to things we see is easily overcome when watching dance. Most of the time we talk about spicy dancing, which is similar but not actually a flavor. The flavor characteristics of Horton often fall into the rich and indulgent category of umami. Umami is a Japanese term and is most readily available in foods like soy sauce and tomatoes. Richness and savoring can be found all across the Horton technique. Distinctly the sense of extended energetic line and elevation both seem to embody umami the most. Every exercise in Horton technique clearly accentuates a distinct energetic line and a suspension of that energy. The stag and stag turn are great examples of this concept. Umami, if transported out of the realm of flavor and to the realm of idea, shares a relationship to concepts of confidence, strength, depth, and pride.

Pride in oneself facilitates growth. This growth transforms over time and takes a lot of experimentation. In cooking pride is often overlooked, and leaves many people in the kitchen playing it safe and preparing boring meals for themselves. Pride allows us to transcend this sad culinary existence. Without experimentation our cooking becomes weak, and the same can be said of our dancing. Interesting flavor combinations, satisfying texture juxtapositions, temperature control, and the look of it: am I talking about cooking or dancing? Either way all of these things can’t be achieved without countless failed attempts. The pride required to fail on one’s own is also required in order to share what you’ve made.

Sharing is by far the most satisfying aspect of both the Horton technique and home cooking. It requires all of the technical aspects, physical and nonphysical concepts, literal and metaphorical applications, understanding of flavor and pride, and most importantly a willingness to participate. Both my own home cooking style and style in Horton class have benefited from the technique of transformation. They inform one another in interesting and even tasty ways; however, more important than their success is their countless failed tries. These failures deepen my understanding of both separately and where they overlap. I look forward to experimenting with my food’s energetic line or suspending its inherent flavor profile. In the same way I am willing to share my food with anyone who has space to spare in their stomach I am pushing myself to share my dancing with that same fervor. Horton’s umami runs deep, and I hope that soon I can find what other flavors run deep in my dancing.

Both my own home cooking style and style in Horton class have benefited from the technique of transformation. They inform one another in interesting and even tasty ways; however, more important than their success is their countless failed tries. These failures deepen my understanding of both separately and where they overlap. I look forward to experimenting with my food’s energetic line or suspending its inherent flavor profile. In the same way I am willing to share my food with anyone who has space to spare in their stomach I am pushing myself to share my dancing with that same fervor. Horton’s umami runs deep, and I hope that soon I can find what other flavors run deep in my dancing.

Dance training: dance and its components

Very often the question arises - what is included in the concept of dance training? It is a mistake to think that this only includes learning the dance sequence and the ability to dance it to the music. The dance includes a lot of components, which we will try to list and characterize.

The physical requirements of dance

Dancers are not only performers, their bodies are also the instruments with which art is created. Therefore, the quality of this art necessarily depends on the physical qualities and skills that the dancers possess. The stronger and more flexible a dancer's body, the more capable they are of a wide range of motion. Almost all professional dancers start training at a young age in order to properly shape and develop their bodies. Certain necessary muscles and ligaments develop, as well as joints, the mobility of which, if not developed in childhood, then later it will be impossible, because they will become ossified.

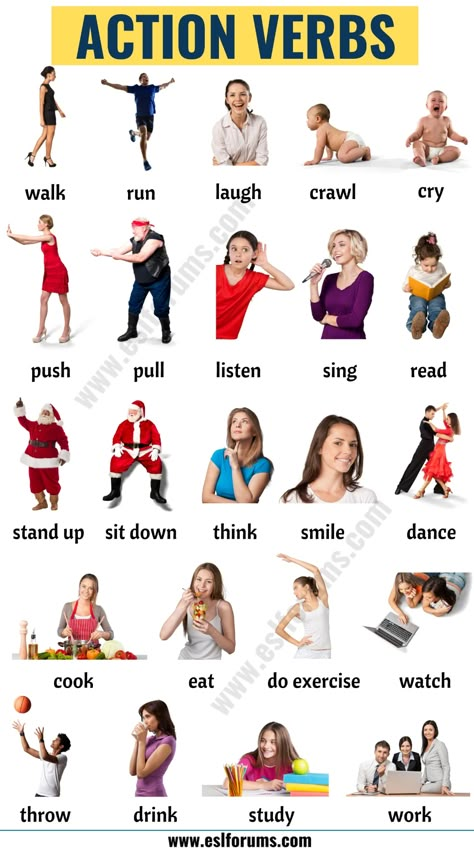

In addition to strength and mobility, a good dancer must also have developed coordination (the ability to work different parts of the body together), highly developed kinesthetic awareness (in order to know and control the position and condition of the body in space), weight control and balance in movement, a developed awareness of space, a strong sense of rhythm, as well as an understanding of music. Particularly in dramatic dance, the dancer must be able to project his movements clearly and make his expressive qualities understandable to the audience. Finesse and body harmony are as often desirable for a dancer as physical beauty, but these are subjective qualities that differ from one culture to another and vary with fashion. For example, today the physical ideal of a ballerina - a slender girl with long legs - is quite different from the preferences of the late 19th century - rounded shape.

Particularly in dramatic dance, the dancer must be able to project his movements clearly and make his expressive qualities understandable to the audience. Finesse and body harmony are as often desirable for a dancer as physical beauty, but these are subjective qualities that differ from one culture to another and vary with fashion. For example, today the physical ideal of a ballerina - a slender girl with long legs - is quite different from the preferences of the late 19th century - rounded shape.

Although modern avant-garde choreographers sometimes work with untrained dancers to take advantage of their natural qualities and talents, so to speak, unsophisticated movements, most dancers in the West are trained either according to a strict method based on classical ballet, or according to methods introduced in the 20th century by choreographers contemporary dance by Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. Other types of dance, such as jazz or tap, are usually taught in conjunction with these methods.

Training usually starts early, between 8 and 12 for girls and 14 for boys, although some ballet dancers and many more modern dancers start later. During ballet training, the rules published in 1828 by the Italian dance master Carlo Blasis in his Codex Terpsichore are closely followed. Blazis argued that at least three hours of dance classes a day were needed, including exercises that gradually developed different parts of the body.

Dance training and its importance

Daily practice is essential not only to shape the body and develop the necessary physical skills, but also to keep the body in proper shape and to prevent injury. Many dance steps require vigorous and unnatural movements requiring joints, muscles and tendons that can easily stretch or damage them if the body is not properly exercised.

As all physiotherapists and trainers say, some people's bodies are better for training than others. Therefore, today many aspiring dancers who want to build a professional career in the future undergo a thorough medical examination. This ensures that they do not have any handicap or disability, such as a weak or twisted spine, which would make them unsuitable for dancing or cause health problems in the future.

This ensures that they do not have any handicap or disability, such as a weak or twisted spine, which would make them unsuitable for dancing or cause health problems in the future.

The exercises to be assigned to the dancer in preparation depend on the dance style. For example, ballerinas must work hard to achieve full rotation of the legs in the hip socket so that the heels can touch the back and the legs can flex 180°. This allows them to lift their legs high into the air while jumping.

While ballet dancers rarely use their torso while dancing, African dancers and some contemporary dancers must be extremely flexible at the torso and pelvis to perform those specific and jerky movements that their particular dances require. Indian classical dancers develop great strength and flexibility in their legs. At the same time, with many years of training, they also achieve perfect control over the muscles of the face and neck, as well as flexibility and control of the joints and muscles of the hands. This is necessary in order to perform complex mudras with accuracy and grace - symbolic gestures with which Indians convey many different meanings in dances.

This is necessary in order to perform complex mudras with accuracy and grace - symbolic gestures with which Indians convey many different meanings in dances.

Individuality and differences between dancers

Strict and "same" training of dancers is often simply unacceptable, if only because each dancer always has his own personal dance style. Certain skills come more easily to some dancers than others, while others will be stronger at something else. For example, one dancer can make excellent jumps, while another can perfectly control the balance of his body in slow, carefully choreographed dance passages. The same choreography can look completely different when performed by two different dancers.

Also the dancers are very different in the way they express the meaning of the music and performance. Some dancers move tensely, vigorously, and even aggressively, while others move softly, fluidly, and fluidly. It would seem that they display the same idea of dance, but in fact they achieve this in different ways. Also, some dancers move exactly to the rhythm of the music, while the movements of others seem to be slightly independent of it. One dancer may move abruptly and expressively, while another may be "cool and detached", concentrating on technical perfection.

Also, some dancers move exactly to the rhythm of the music, while the movements of others seem to be slightly independent of it. One dancer may move abruptly and expressively, while another may be "cool and detached", concentrating on technical perfection.

In contemporary dance, the dancer may be highly valued for his individual style and technique, but is generally expected to bring out his personality in the choreography.

The display of individual style is clearly needed today in all styles of dance, such as ballet, ballroom dance, modern dance, where trained professionals perform complex productions for the enjoyment of the audience. Many dance styles allow individual dancers to showcase their talents. And in many folk dances, especially those that originated from ancient rituals, the sense of unity in the group is at the head of everything, and not the individual skill of any one dancer. The essence of such dances is not the manifestation of the talents of the dancer or choreographer, but the perfection of the ritual.

From amateur to professional in dance

Demanding standards and rigorous training from early childhood are a must when dance is to be an art to be performed in front of an audience. Scholars such as the German musicologist Kurt Sachs have pointed out that in the earliest cultures, where dance was something that all members of a tribe participated in, dancers were not seen as "specialists" who were "selected" and trained for their special skills or beauty.

But one day religious worship (the original reason for dancing) developed into a ritual in which it became important for the dancers to be as skilled and perform as well as possible. After all, people believed that if the ritual was not performed well and accurately, then prayers or magic would fail. The dancers were carefully selected for their subsequent special training, which was provided either by the family or by qualified people who lived and taught outside the community. The performance of the dancers has now become the subject of the strictest judgments. For example, Sachs mentions a tribe on the island of Santa Maria in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) where old men stood with bows and shot at every dancer who made a mistake.

The performance of the dancers has now become the subject of the strictest judgments. For example, Sachs mentions a tribe on the island of Santa Maria in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) where old men stood with bows and shot at every dancer who made a mistake.

Often in religious dances the dancer undergoes not only intense physical training, but also training in spiritual discipline. Such dancers often formed a special caste, separated from the rest of the community. In the religious Hawaiian hula dances, the dancers observed important taboos and took part in sacred rites in order to be in good shape for dancing. The traditional religious dancers of India had to remain virgins as they were seen as the brides of the gods. They were taught the art of dancing by masters of the highest caste. But over time, this practice became corrupt, and temple dancers were paid to dance in the homes of the rich.

Professional dance in history

In Europe, professional dance for many centuries was associated only with jesters and itinerant groups of jugglers, dancers, poets and musicians, who, as a rule, were considered as social "lower classes".

The early ballets at the royal courts were performed almost exclusively by amateur dancers (although this was done under the strict instructions of professional dancers). For these dancers, ballet was a means of demonstrating their own grace, dignity and good manners. At the same time, comic or burlesque productions were performed by much more professional people who were not so concerned with expressing their dignity.

King Louis XIV of France, himself an avid amateur dancer, was the first to realize that the art of dance could not develop unless the dancers were properly trained and raised to be true professionals. In order to provide the standards for this training, he created the Royal Academy of Dance in 1661, merging it into the Royal Academy of Music in 1672 (this Academy has survived to this day under the name "Paris Opera").

Thanks to the work of such masters as Pierre Beauchamps, the first director of the Royal Academy of Dance, the basic principles of dance technique were unified, after which the dancers quickly reached much higher heights of virtuosity than before. Prior to Louis's innovations, the split between court dances, with their carefully cultivated style and movement patterns, and the less refined peasant dances, was not so obvious. But from that moment on, professional and amateur dances in Europe really became very different.

Prior to Louis's innovations, the split between court dances, with their carefully cultivated style and movement patterns, and the less refined peasant dances, was not so obvious. But from that moment on, professional and amateur dances in Europe really became very different.

Modern dance uses many of the steps and positions of those classical court dances, although often in a completely different style.

Folk dances and social dances

Many of the steps used in folk dance are essentially basic versions of ballet dance steps. In addition, simple turns, where the dancer turns on one leg, and lifts, where the man grabs his partner by the waist and lifts her into the air, are often used. Hands and body movements in folk dances are usually simple and calm: the arms are held at the waist or hang freely at the sides, and the body sways in time with the movement.

In some dances the performers dance separately, in others they hold hands. The steps are usually repeated in long series, but they often follow fairly complex and highly ordered formations. Whether singles or couples dances, performers usually group in a circle (often two concentric circles moving in opposite directions) or in a line. Within these groups there are many specific formations; for example, four or more dancers hold hands and move in a circle, or dancers join hands to form an arch under which others pass.

The steps are usually repeated in long series, but they often follow fairly complex and highly ordered formations. Whether singles or couples dances, performers usually group in a circle (often two concentric circles moving in opposite directions) or in a line. Within these groups there are many specific formations; for example, four or more dancers hold hands and move in a circle, or dancers join hands to form an arch under which others pass.

Social dances are rarely performed in any strict formation, although dancers may occasionally form lines or circles spontaneously. Some of the most famous social dances include the waltz, foxtrot, tango, rumba, samba, and cha-cha-cha. The foxtrot is danced at a moderate tempo (time signature is 4/4 slow tempo). Waltz is a dance in 3/4 time, in which the most common figure is a full turn in two measures with three steps in each. Cha-cha-cha is a dance in 4/4 time, the tempo of which is 30 beats per minute.

The basic patterns of steps in any dance are complemented by various turns: dancers turn on one foot, as in a waltz, or change direction, as in a foxtrot. In many ballroom and social dances, the man and woman remain in the same position in relation to each other (either facing each other or slightly turned to the side). However, there are also dances such as cha-cha-cha, in which a man and a woman can dance generally separately from each other.

In many ballroom and social dances, the man and woman remain in the same position in relation to each other (either facing each other or slightly turned to the side). However, there are also dances such as cha-cha-cha, in which a man and a woman can dance generally separately from each other.

Choreography

Choreography is the art of creating dance, it is the collection and organization of movements into an ordered system. Many Western theatrical productions and dances were created by single choreographers, who were considered both authors and owners of their works. Thus, they can be compared to writers, composers and artists. Most social and recreational dances, on the other hand, are the product of a long evolution. They are associated with the innovations that groups of people or anonymous individuals eventually brought to traditional forms. This evolutionary process is also characteristic of most non-Western choreography, where the forms and types of dances were passed from one generation to another and changed very little over time. Even in those cultures where dancers and choreographers create their own variations on the theme of existing dances, there are also national minorities among which there are traditional dances that are passed down from one generation to another.

Even in those cultures where dancers and choreographers create their own variations on the theme of existing dances, there are also national minorities among which there are traditional dances that are passed down from one generation to another.

Motives and methods of choreographers

When choreographers create new works, or perhaps rework traditional dances, they always need an impulse or motivation for their work. This stimulus may be some specific function for which the dance is intended (for example, celebrating an event, praying for rain, etc.). Also, the dance may not have any specific function, and the choreographer may create it simply by responding to some external stimulus (a natural or social event, a piece of music, a picture or a story from literature ... and simply anything). Also, the desire of the choreographer to express a particular concept or emotion can act as a stimulus.

The methods by which different choreographers create their dances also differ. Some of them work closely with the dancers from the very beginning, trying out ideas and accepting suggestions from the dancers regarding the expression of the initial idea through dance. Others immediately begin with clear ideas about the future form of the work and its content.

Some of them work closely with the dancers from the very beginning, trying out ideas and accepting suggestions from the dancers regarding the expression of the initial idea through dance. Others immediately begin with clear ideas about the future form of the work and its content.

The choreographic process can be broadly divided into three stages: the selection of movements for the production, the development of these movements into dance forms, and the creation of the final structure of the production.

The way in which a choreographer selects movements for his production depends on the traditions with which he works. In some forms of dance, it may simply be the process of creating variations within traditional, age-old movements. For example, the dances of the Italian court masters of the 14th and 15th centuries were simply variations on existing dances. They were published in dance manuals under their own names.

Even today, many ballet choreographers use the traditional dance steps of past centuries as a source for their productions. The same is true for many modern Indian or Oriental dancers: they may not strictly follow the traditional structure and sequence of movements that have been passed down from generation to generation, but they remain the same in terms of the characteristic style and traditional quality of the movements. Also, their steps or movements do not differ much from the original.

The same is true for many modern Indian or Oriental dancers: they may not strictly follow the traditional structure and sequence of movements that have been passed down from generation to generation, but they remain the same in terms of the characteristic style and traditional quality of the movements. Also, their steps or movements do not differ much from the original.

Contemporary Western forms of choreography eventually developed new individual traditions to replace established ones. New trends were meant to satisfy personal visions of ideas in dance. But even in the work of the pioneer choreographers, major influences can be traced. For example, Martha Graham's early work in the 1920s clearly showed strong influences from American Indian culture and Southeast Asian dance forms previously used by her mentor Ruth St. Denis. Merce Cunningham's technique was largely adopted from classical ballet. Even the ballet by Vaslav Nijinsky "The Rite of Spring", which the audience during its premiere at 1913 was perceived as a complete contradiction to all known dance forms, perhaps influenced by the rhythmic-motor exercises of Jacques Dalcroze, as well as archaic forms of dance, interest in which had already arisen thanks to Isadora Duncan and Mikhail Fokin.

Although each choreographer draws from different sources and often uses contrasting styles, most of each choreographer's dance pieces have some sort of characteristic style of movement. However, dances are rarely just "a selection of individual movements". One of the most important features of any choreographer's style is the way in which he "assembles" individual movements into dance steps.

Development of dance movements into fragments

Fragments are a series of movements connected to each other through a single physical impulse, and also have a clear beginning and end. As an analogy, we can give an example of how a singer sings a series of words in one breath. A number of factors influence the viewer's perception of this series of movements as a single fragment.

The first of these is the presence of some kind of logical connection between the movements, that is, something of a single whole, due to which the movements do not seem arbitrary and isolated. One movement should flow easily and naturally into another within the same fragment, and there should not be any transitions that do not harmonize with a clearly visible pattern of movements (a good example is the basic three-step step in a waltz). Another essential factor is the rhythm, which must be the same for all movements in the fragment. In addition, in fragments that have a single rhythm, strong and weak accents in movements are repeated in the same sequence and at the same time tempo.

One movement should flow easily and naturally into another within the same fragment, and there should not be any transitions that do not harmonize with a clearly visible pattern of movements (a good example is the basic three-step step in a waltz). Another essential factor is the rhythm, which must be the same for all movements in the fragment. In addition, in fragments that have a single rhythm, strong and weak accents in movements are repeated in the same sequence and at the same time tempo.

Dance fragments vary both in length and shape. A fragment may begin with a sharp forceful movement that has a maximum energy, which gradually fades away towards the end of the fragment. Naturally, this does not have to be at the beginning of the fragment - a similar maximum burst of energy can be both in the middle and at the end of the fragment. In other dance fragments, on the contrary, there is a uniform distribution of energy. These factors determine how fragments will be perceived and what effect they will have on the viewer.

Long, steady-paced, repetitive passages produce a hypnotic effect, while a series of short passages with energetic climaxes seem nervous and dramatic. One of the distinguishing features of Martha Graham's early style was that she eliminated the transitions between fragments, which ended up being short, "chopped" and sharp.

Once a dance piece has been composed, it can be used in a dance in different ways. Perhaps the simplest way is to repeat the given fragment. Separate dance fragments can also be repeated in a dance in a certain order. Also, these fragments can be repeated in different ways: for example, with different numbers of people, at different speeds, with different styles of movement (sharp or smooth), or with different dramatic effects (happy or sad).

Used Wikipedia Materials

12 Life hacks to quickly learn how to dance from Mamita Dance

Dances

Author: Pavel Pavel

Psychologist, Lecturer Salsa and Tango

Dances

Author: 9000 Pavel Pavel Pavel Pavel Pavel Pavel Pavel Pavel Pavel Pavel Pavel Gat , teacher of salsa and tango

At the start, you always want to get a quick result. When it doesn't happen, the hypothesis arises that everything takes time. After a conditionally acceptable time, humility comes to mastering pair dances, which, perhaps, is not given, and I will just do what I learned somehow.

When it doesn't happen, the hypothesis arises that everything takes time. After a conditionally acceptable time, humility comes to mastering pair dances, which, perhaps, is not given, and I will just do what I learned somehow.

This is the most common story of those who believe that the mere act of attending a pair dance class is enough to learn how to dance.

Absolutely not. If you want to really dance well, you have to make an effort outside of the dance class. A good teacher will definitely be needed, but the initiative should be on your side.

1. Listen to music

The most common and accessible advice that is given already in the first lessons. And it definitely works. Music creates a certain atmosphere of the dance and intuitively you want to move to it. It doesn't matter where you listen to music - in the car, on headphones while walking or doing household chores.

An addition that will help you dance better is your active participation in the music. Sing along, dance or simply beat musical accents with any free parts of the body. In the subway, for example, it is enough to tap out bright moments with your fingers, in the car to sing along with sounds, and at home you can jump for pleasure.

Sing along, dance or simply beat musical accents with any free parts of the body. In the subway, for example, it is enough to tap out bright moments with your fingers, in the car to sing along with sounds, and at home you can jump for pleasure.

2. Watch videos of good dancers

It's complicated, but also obvious. It’s more difficult, because without recommendations from more experienced dancers, unfortunately, it’s not so easy to find a good quality video on the net (I mean not the resolution quality, but the content itself).

Meaningful video viewing is about building an understanding of HOW dancers make a particular impression on a partner or viewer. Technology is at the heart of everything. Understanding how the pros do it is a big step forward.

It is important to distinguish a show from a disco dance, a staged performance from an improvisation, a stylized dance from an authentic one, etc. Ask for recommendations and dance teachers will always throw off a couple of videos of worthy landmarks.

Tango Z. Showreel.

Online modern tango courses

Tango nuevo is the most advanced version of tango. We can quickly learn to dance from zero to a steep level.

| View details |

3. Dance in salsatecas/milongas/discotheques

A very delicate moment when it is worth coming to the first party. From a technical point of view, most students in 1-3 months have a sufficient set of figures and techniques to come and dance calmly. Psychologically, the same moment can be stretched out for an indefinite time. After all, it is imperative to “not lose face”, “learn more figures” and be sure what to do in case “there is an unfamiliar movement”.

In fact, the partygoers don't really care (except for a small layer of non-professional teachers who want to help inexperienced dancers by treating them as customers in the future). It is important to come and try dancing after a month of classes. You can only with friends or guys from your group. This will be enough to feel the adrenaline and inspiration from the dance.

You can only with friends or guys from your group. This will be enough to feel the adrenaline and inspiration from the dance.

4. Dance with partners or partners not of your level

The conventional wisdom that you need to practice in groups of your level does not stand up to the test of experience. Perhaps now your eyes widened in surprise, and you want to meaningfully read the phrase again. Yes, you saw everything correctly: when you dance with a partner of your level, you don’t grow anywhere.

It's important to understand that not only does it work one way and you have to dance with cooler dancers, but it works even more effectively the other way. It is no coincidence that teaching pair dances dramatically raises the level of the teacher himself. You have an endless stream of very beginner dancers.

How it works. A more experienced partner needs to be "stretched". It's easy and obvious. With beginners, you need to take more initiative on yourself, see the general pattern of the dance more widely, turn on and insure more, try to be an example and be more careful. The quality of interaction begins to grow significantly. And wonderful partners too.

The quality of interaction begins to grow significantly. And wonderful partners too.

Dancing with partners of your level doesn't make you grow. Dance with beginners and more advanced dancers

Dominican Bachata Women's Style Online Course

Want to learn how to hypnotize those around you with the most appetizing part of your body? On the course we will tell you all the secrets.

| Interesting |

5. Learn to dance for a partner and for a partner

Turks and Argentines are one of the best partners in the world. In Russia, partners are highly valued. Why? The answer is simple. In Argentina and Turkey, it is not questionable for men to ask another man to lead in one piece or another and give feedback on the quality of the lead. For them, it will be a great shame to hear moralizing from a partner, or even more so to be known in the community as an insecure partner.

In Russia, due to the constant, often far-fetched, opinion that there are more women in pair dances, partners calmly get up and study their partner's part. Such partners then grow into very cool dancers and teachers. In no case do this at parties, only in class. Here we are talking only about the learning strategy. At parties, be yourself.

Such partners then grow into very cool dancers and teachers. In no case do this at parties, only in class. Here we are talking only about the learning strategy. At parties, be yourself.

6. Do not memorize the links

Always try to look deeper and understand the through principle and idea of movement. Understanding what and how is done will make it possible to independently generate any sequences and chips.

Human memory is limited and there will always be a moment when something will escape and your repertoire will be limited by the size of RAM.

In Argentine tango, for example, there are seven levels of movement construction that, when mastered, will allow you to make millions of combinations. And how many dance sequences can you really remember? In rueda, more than 150 figures dance in a rare circle. It's hard to keep more in mind.

7. Develop your body

Many years of experience in teaching partner dance shows that as soon as everyone pairs up in class, any progress in individual style ends. But it is the individual style that distinguishes everyone at the disco: partners change, and style is always with you.

But it is the individual style that distinguishes everyone at the disco: partners change, and style is always with you.

The body as the main instrument of dance must be very plastic, responsive and emotional. Surprisingly, not all pair dance schools have a general physical warm-up. It is vital to tune the body and understand how it works.

You can always train extra and concentrate more on the basic steps, as their true value is as body work. The sequence of steps is, in fact, the simplest thing that can be in pair dancing. The quality of individual performance determines the craftsmanship.

8. Try on the images of inspiring dancers

A psychological life hack for those who have already mastered the steps, but still feel that there is not enough brightness and drive. Most are terribly afraid of being someone else's "clone". Here the action is the same as under the influence of hypnosis - the more you resist, the more you plunge into an altered state of consciousness.

With a high degree of probability, you are already dancing like someone else's "clone". A meaningful fitting of someone else's image is that you mentally take the image of the one who inspires you (inspiration is critical in this case) and "put on" yourself. Then you start dancing and trying to feel in general how it is to be able, for example, to be the best partner or the sexiest partner in a disco. This is much more difficult than it seems. But it works extremely efficiently.

9. Dance to offbeat music

Habitual rhythms keep you tight. Tango salon or speedy timba leave little room for experimentation and fantasy. Pattern dancing is always noticeable and is reserved for beginners.

The truly new is born outside of the usual. Look for places to experiment. If there is no place, organize self-training. The main thing is not to get carried away, because music determines the style. We bring something new to pair dances, rather than trying to change them.

Search, improvise, do not be afraid to go beyond, develop in different directions, be inspired by music atypical for style

10. Try your hand at basic dance directions

dances exist according to their own non-choreographic laws.

This is the deepest delusion, which has turned into a ceiling for the qualitative development of partner dances. After all, all professional dancers, for example, in salsa or bachata, build their ideas on the basic choreographic principles.

Do not think that choreography is only applicable on stage. Any meaningful movement of the body can be choreographic. In general, try classical or modern choreography. Basically, hip-hop can work too.

11. Look for battle sensations

Pair dances return us to an active position of manifestation of our body. As in the days of our ancient ancestors, we impress the members of the opposite sex by how dexterous, hardy, sexy, etc. we are. Modern laws of the jungle in the entourage of large cities.

As in the days of our ancient ancestors, we impress the members of the opposite sex by how dexterous, hardy, sexy, etc. we are. Modern laws of the jungle in the entourage of large cities.

If you look around the dance floor, it becomes clear that the majority are clearly herbivores (not in the sense of vegetarians, but in relation to those around them). I am sure that predators are always more interesting in terms of the attractiveness of the image - try to find a counterbalance among herbivores, for example, a cat woman or a lion man.

The conversation is about an internal position, not about aggressiveness. Lability and lack of control are inherent in adolescents, and not in adult self-sufficient people.

Accordingly, even a training or friendly battle gives, on the one hand, practical skills - to make a bright sequence of movements, bring an idea to a climax, show a spectacular feature, on the other hand, develops the psychological basis of the dance - self-confidence, resistance to extraneous attention, self-control and self-control in complex elements.

12. Communicate with professionals

The environment shapes the internal position. Basically, real passionaries of the dance community are ready to openly talk, discuss and support the development of dance in every possible way. Universal principles and the ideas they articulate have a much longer and more practical perspective than meets the eye.

Accept that, for example, behind the words "listen to your partner" is not only a beautiful metaphor, but also a practical skill to literally listen to your partner. At the same time, always treat every thought, even the most respected teacher, as a private opinion.

Your skill will lie in finding the scope of the idea even in conflicting opinions. Most often, the contradiction is speculative and the truth lies in the angle of perception or situationality.

Your dancing growth will stop sooner or later. This can happen at the level of three basic steps or years of experience in teaching and show performances.