How does dance relate to science

Science of Dance (Guide on Physics of Dance)

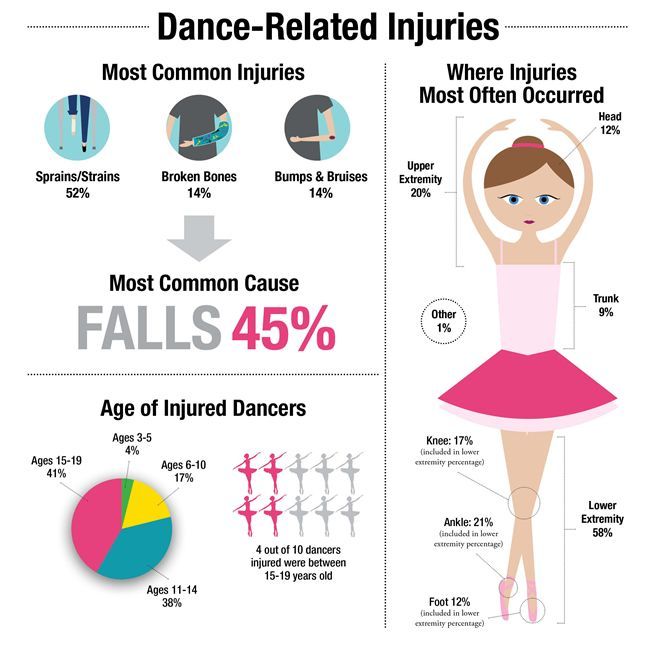

Dance Science is a field of research that aims to investigate dance extensively. From how lack of training can affect the health of dancers in this area to preventing injuries, this science has provided some surprising findings.

Researchers have looked at how to make dancers safer by finding better ways to spot heart problems before they become severe, and even looking at what happens when you get hurt on stage.

Furthermore, the Science of Dance explores the human body’s reaction to movement as it changes in space and time, the fundamental building blocks of any type of dance.

It focuses on developing fitness and personal abilities through incorporating studies of both the anatomy of the body and movement patterns.

This scientific knowledge facilitates understanding and knowledge of body movement while increasing athletic performance through the intricate balancing and acrobatics required to master specific movement patterns.

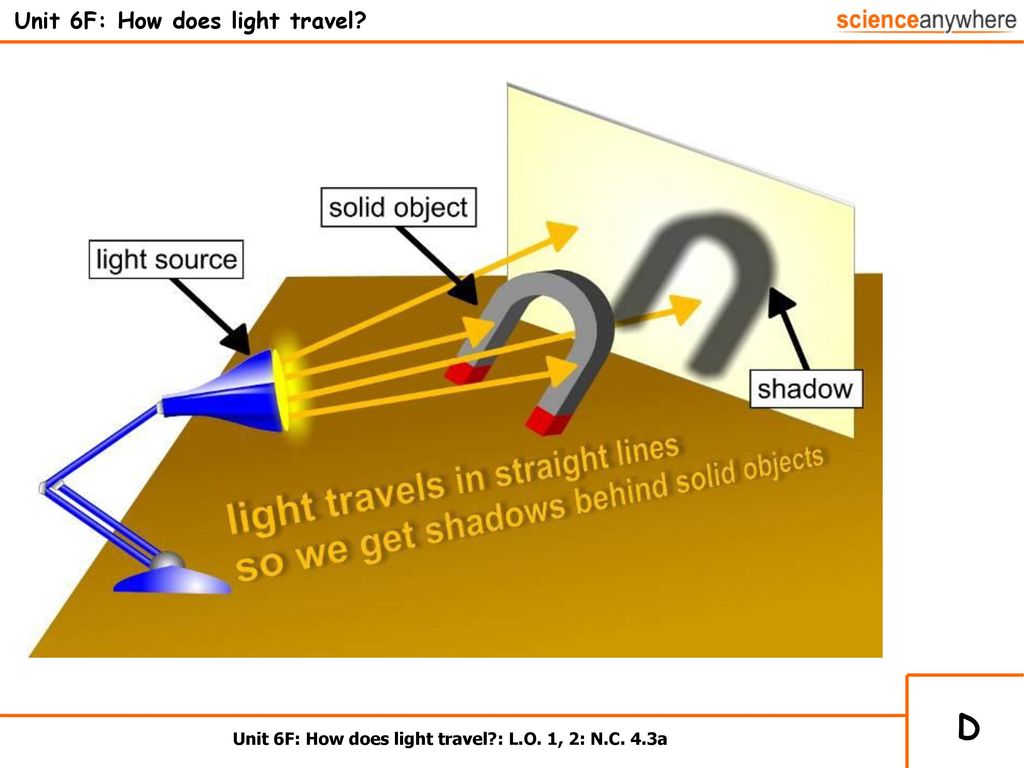

The study of physics—mainly classical physics—is integral to a well-rounded education. However, we rarely associate it with any kind of dance. Contrary to popular belief, classical mechanics can describe the movement and bodies of a dancer.

The laws of physics, however, just like any other physical object in the universe, may describe the movements of a dancer.

1. Newton’s First Law of Motion

Newton’s first law of motion states: “Any object will remain at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless compelled to change its state by the action of an external force.” When a dancer leaps, the center-of-gravity must is initially raised off the ground, and there needs to be a force acting on it.

This is because of a property known as inertia; all objects resist a change in their state of motion.

There are three forces acting on a dancer while he or she is in the air. There is the force of gravity, there is the force of friction, and there is the force of inertia.

These three forces cause the dancer to accelerate once he or she leaves the ground. There is a force that the dancers’ body applies on the ground that pushes them into the air (normal force).

The other force is one between the dancers and the earth (gravitational force), which pulls them down.

Although the dancer is breaking inertia with a kick or other movement, inertia is able to break the dancer back down to the floor again.

This shows that once all the forces of dance are working together to keep the dancer airborne, and these forces must combine to take the dancer back down as well.

2. Newton’s Second Law of Motion

Newton’s Second Law of Motion states: “The rate of change of momentum of an object is directly proportional to the force applied.” Many forces act on a dancer, and every force has a direction and magnitude.

However, what most people never notice is that these opposing forces have to be balanced in order for a dancer not to fall over.

The normal has to act upwards in order to balance how gravity pulls the dancer downwards.

Now that we know that gravitational force, normal force, and friction act upon the dancer, we need to know-how? Let’s observe.

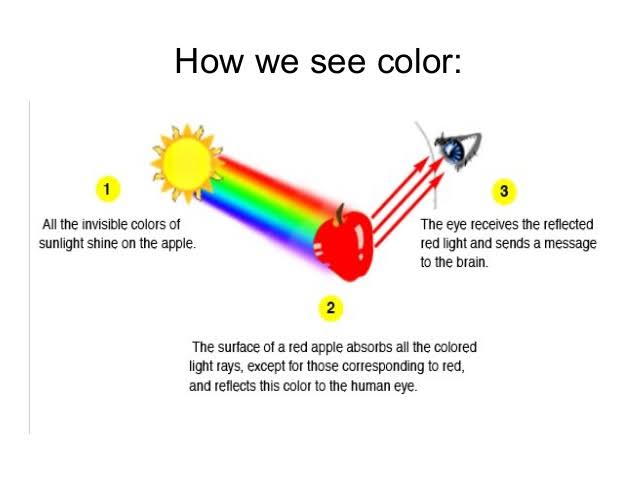

Experiment: A skydiver fell from the airplane and will have no initial velocity. When the skydiver jumps off the plane, they will not have any acceleration towards the ground.

Now when the skydiver is in mid-air, gravity is pulling them towards the land which pulls them. While these downward forces are trying to accelerate the skydiver toward the ground, upward forces such as air resistance prevent this and slow down the skydiver.

Dancing takes place on a similar principle. All the forces are stable, and the dancer stays upright, through the concept of balanced force physics-how the net force on a body must be zero in order to stand still.

So, an essential requirement of dancing is to balance the various forces acting on the body- including gravity and friction.

Gravitational force makes things fall. It acts upon all objects; no matter if they are on earth, gravity will continue to act as it does. So, how is it equalized?

The normal force is a support force that is compared to the weight of an object. The normal force supports objects and keeps them upright. In dance, we use the same concept when we are resting in a plie position.

As gravity is pulling us down into the earth, our hips would naturally like to collapse inward upon the supporting muscles of our body.

However, if we place our mind into the normal force of our leg support, then this upward force will support and hold our hips open as we sink down.

Thus, gravity is opposed, and the dancer stays upright.

3. Newton’s Third Law of Motion

Newton’s third law of motion states that “for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” This means you generate a force on the pointe shoe when you push against the ground; ballerinas call this pushing off.

The ground pushes back up at the dancer at the same speed and with the same strength, creating the force for pointe shoes to work.

But this can only happen in a balanced manner if the centre of gravity is aligned with the point of contact.

If the center of gravity were not aligned, then the forces would not be equal, which creates a state of unbalance.

The dancer would topple over. This also explains why dancers spin around the same rotational axis. If they didn’t, the center of gravity would move.

Maintaining balance is a combination of skill and experience. Dancers must anticipate, calculate and respond quickly to situations they encounter in order to keep their center of gravity and rotation stable.

The Science Behind The Effects of Dancing

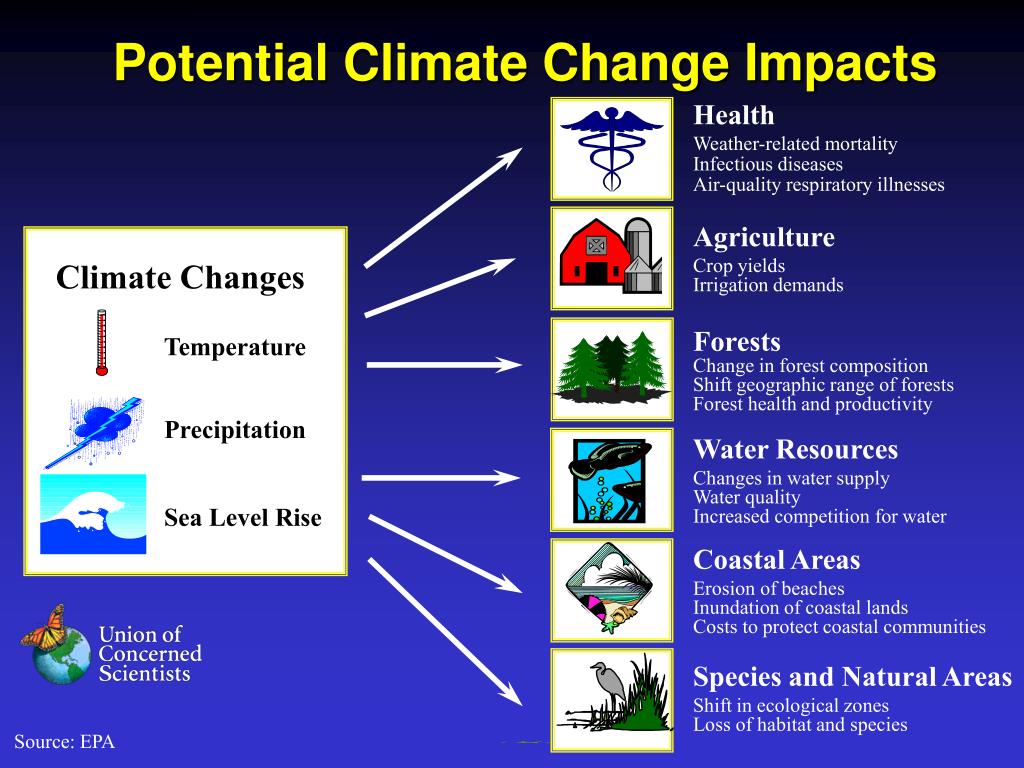

Research overwhelmingly shows that dancing physical and mental conditions such as social isolation, stress, depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, ADHD, and Alzheimer’s.

This is because it improves the frame of mind and even some cognitive skills. Scientists have also found that taking a class in ballroom dancing can improve cognitive function in healthy seniors and in older adults with mild impairment.

Scientists have also found that taking a class in ballroom dancing can improve cognitive function in healthy seniors and in older adults with mild impairment.

Dancing can be physically exhausting, and after dancing you should be ready to relax. The heightened endorphins help lengthen your attention span and make you more receptive to positive stimuli, on stage and off.

Happy thoughts make for a happy mood. It reduces stress and stimulates the release of serotonin, the feel-good hormone.

It also helps in neuroscience, including developing new neural connections, enabling long-term memory, and improving spatial recognition. All in all, it’s extremely good for health.

How A Dancer Controls Dizziness

The brain of a dancer rewires itself after constant training. Dancers are less likely to feel dizzy because they have fewer neurons sending signals to a cerebral cortex area responsible for the perception of dizziness.

Although an advantage for dancers, this adaptability can lead to greater feelings of dizziness when people give up dancing.

Their brains no longer receive the same input that made them adapted to suppress the response. They experience symptoms of perceiving motion as they would if they had never been dancers.

Dance Science Degrees

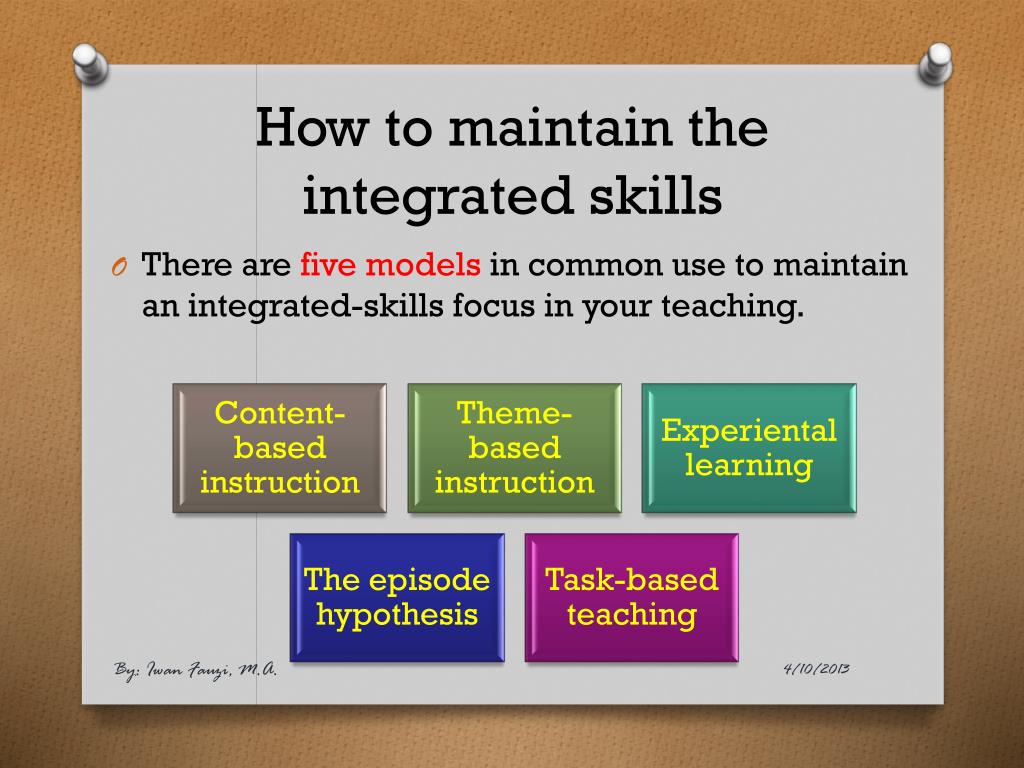

After completing a Bachelor’s degree in dance science at CSULB, students will be able to integrate the concepts of leading scientists and researchers within neuroscience, biomechanics, and psychology that guide their exploration of both fundamental and chronicle questions in the advancement of the self.

The major objective is to conduct research based on primary data that establish formulas for movement patterns.

The Dance Science major integrates coursework in dance and human performance with scientific disciplines so that students can connect with other majors on campus.

There are several levels of education in Dance Science. These include- Undergraduate, Post Graduate, and Ph.D.

A lot of universities in the United States offer a variety of courses as well. These degrees can go on to offer lifelong careers.

These degrees can go on to offer lifelong careers.

Dance Science Careers

Dance degrees are an excellent way to gain a firm grounding in a wide range of practical performance skills and conceptual dance techniques alongside social sciences and humanities.

They combine practice, theory, and aesthetics, making it the perfect bridge between the dance industry and academia.

They open the doors for a plethora of careers, including the following. Remember, this is only a small sample of the careers you can pursue with a degree in dance science.

1. Dance Movement Psychotherapist

Dance Movement Psychotherapy is a holistic and integrated approach to treatment that takes the whole person and the whole of his or her experience into account.

It sees the body as a means of expressing experiences, exploring issues, and finding solutions. It provides an opportunity to experiment with new possibilities for resolving difficulties, to find out what works best in different situations.

2. Dance Administrator

Dance administrators may work for independent dance studio owners, large corporations, or government organizations.

Regardless of their specific position, all dance administrators have similar responsibilities regarding bookkeeping, human resources, and business operations.

Dance administrators are also responsible for handling personnel problems ranging from employee relations to resolving performance issues within the dance company.

3. Choreographer

There are many roles in the entertainment industry that require choreography. A choreographer and the dancers they work with are responsible for several different types of performances, including features in films and television, live shows at theatres, and music videos.

In order to break into this career, you’ll usually need a degree in dance or movement arts, often combined with a related subject like a business.

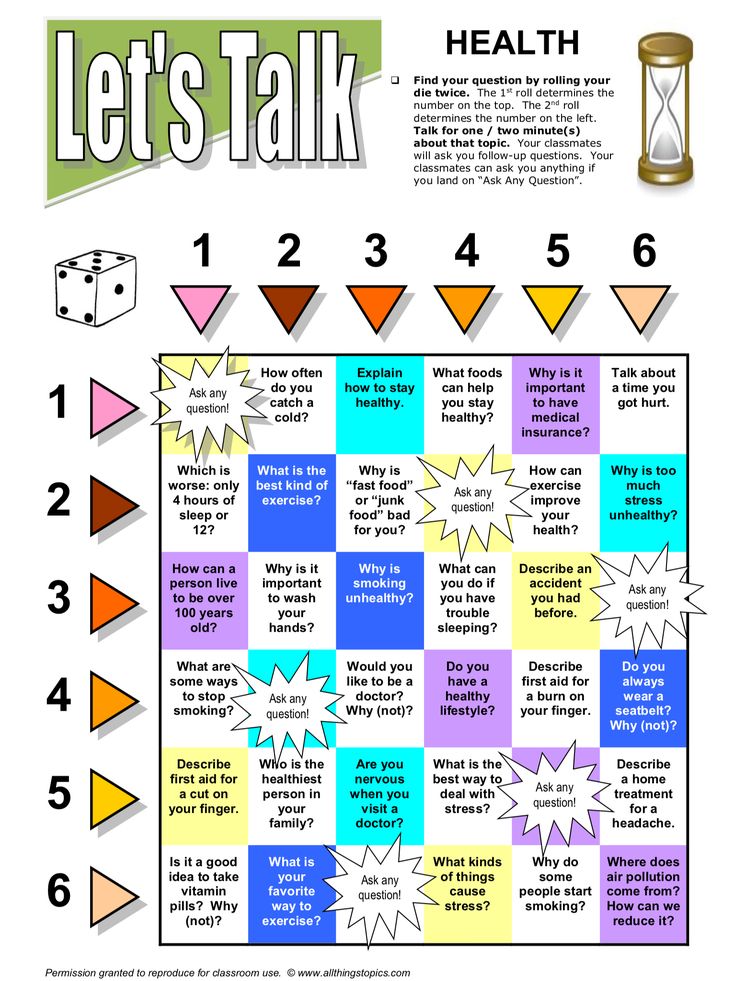

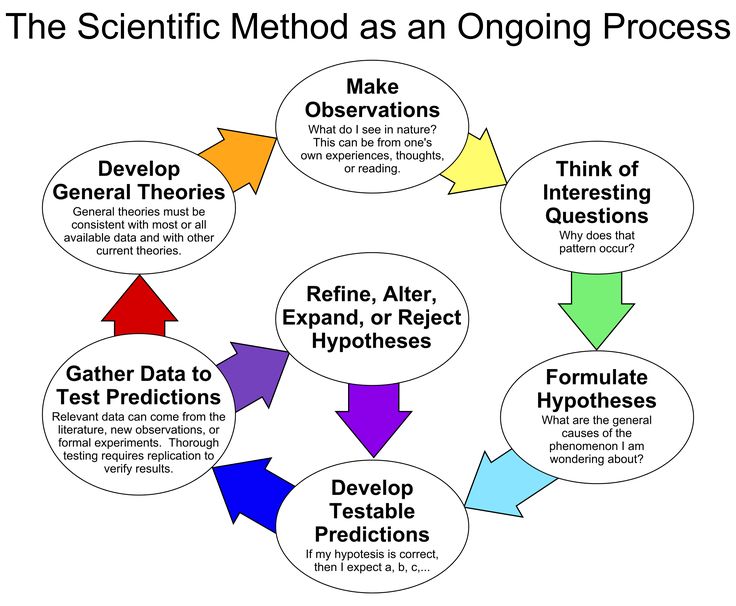

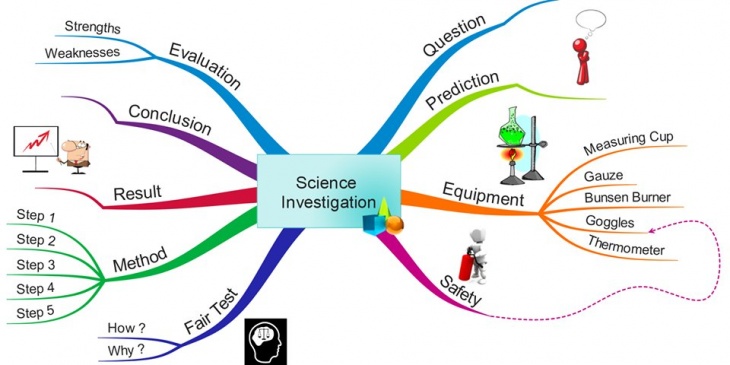

Dance-Related Science Fair Projects

Science fair projects don’t have to be limited to only those that can easily explain through numbers and data. Sometimes, science fair projects are most intriguing when scientific theories are best demonstrated with visual aids.

Sometimes, science fair projects are most intriguing when scientific theories are best demonstrated with visual aids.

For example, dance-related science fair projects are a unique way to combine science with the art of dance. Students can easily demonstrate their hypotheses and find solutions to a lot of questions through the following experiments:

1. Demonstrating Health Benefits

This experiment would involve taking a group of people of various ages who do not dance and get them to go to beginner dance classes.

At the start and end of six months, perform the same physical tests on both groups. This will reveal whether there are any health benefits from taking up dance lessons. These strength tests may include:

- Flexibility- How far can they split

- Muscular Endurance- How long they can hold a plank

- Cardiovascular Endurance- How far can they run on a treadmill

2. Demonstrating Emotional Effects

Compile a series of videos of varying types of dances with different music. Play all the videos for a wide range of people and record the change in emotions.

Play all the videos for a wide range of people and record the change in emotions.

Notice if the emotion has anything related to the dance and music. For example, if it’s a nostalgic, soulful song- what mood does it cause? If it’s an upbeat pop sound with breakdancing, how do they react?

List your observations and present them at the fair. If possible, do this with the judges as well! It’s an interesting spin to a science project.

3. Demonstrating Varying Effects of Dizziness

Put a group of dancers and non-dancers on a rolling chair and tell them to pull a lever when they are feeling dizzy.

Dancers and non-dancers alike reported feeling dizzy after about 7 seconds of spinning. But dancers took an average of six seconds longer to pull the lever than non-dancers.

The results suggest that everyone’s sensory cues are based on the same unconscious system for telling them when their bodies are spinning at a dangerous speed.

But in dancers, this system is strengthened by daily practice, making them more aware of how to balance on one foot and hold their arms above their shoulders without getting sick.

The biggest difference between dancers and non-dancers is that dancers will pull the lever about one second earlier.

They know when they are feeling unstable a lot sooner than non-dancers do. And the reason for that is that they have very strong proprioceptive awareness.

Proprioception is your sense of your body in space, knowing where your limbs are and how they relate to each other, and having a sense of balance.

So, they will not feel dizzy after they finish spinning. Note down your observations and present them at the fair.

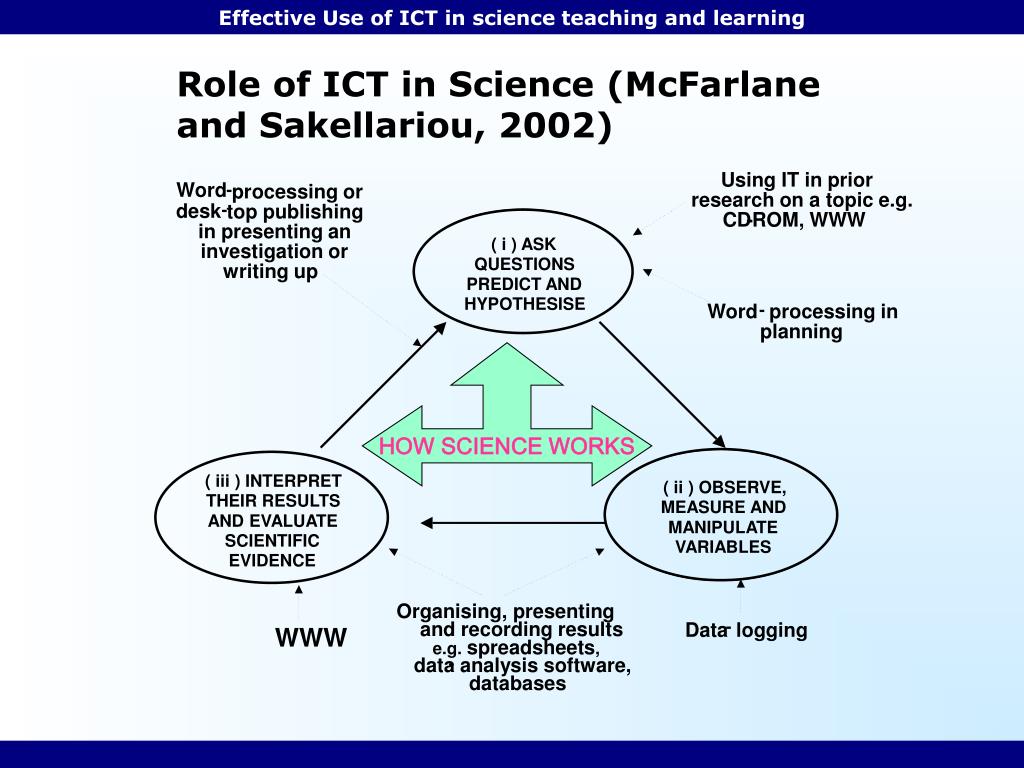

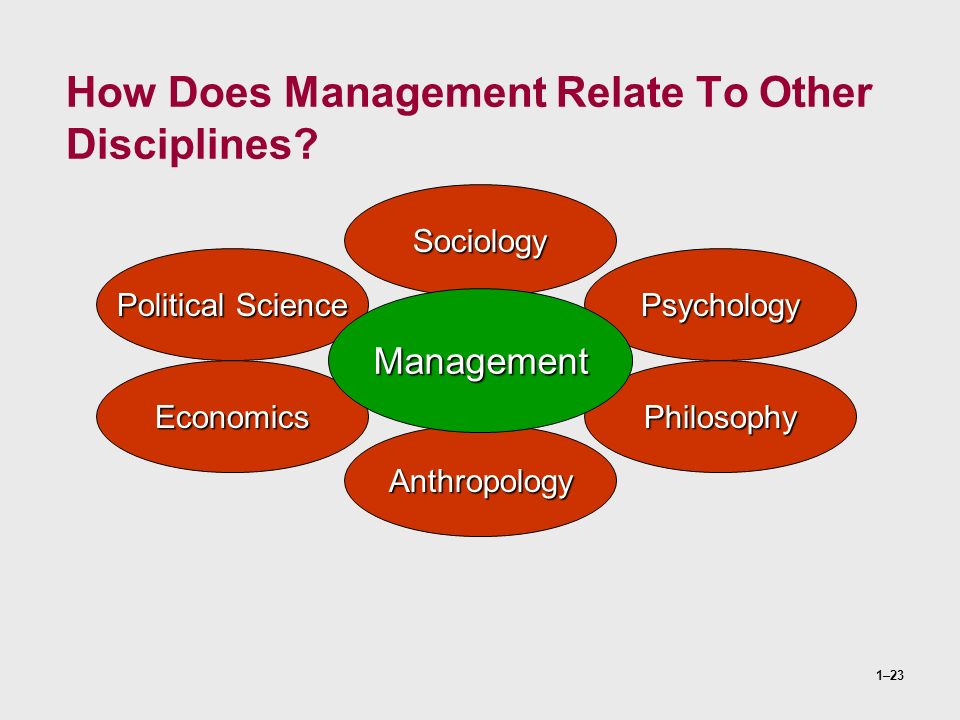

How Is Science Used In Dance?

Science has always been an integral part of dance, with physics and anatomy class being an essential part of training at many schools.

Science is also used in dance in a more specific way to improve performance and reduce injury risk. The practice of dance science came about after the traditional method of fixing dancers’ problems individually proved inadequate. It simplifies the lives in many fields, such as:

1.

Health and Performance

Health and PerformanceThe physical health of a dancer is one important aspect that can seriously affect their ability to perform well.

These fitness routines are why many dancers have a strict diet that includes eating right and exercising daily.

They are also required to keep up with annual physicals just like any other athlete. This study of science is responsible for developing fitness routines for dancers that will keep them in the best possible physical and mental condition for dancing.

This understanding of the fitness required to be a performer is essential. Scientists realized that dance provides an excellent way to stay fit, but it is not enough to keep healthy. Various workout programs can help you enjoy dancing more while maintaining an outstanding fitness level.

Science has a straightforward answer for how one can use dance, exercise, and physical therapy together to improve the fitness level of students.

Three general types of classes are commonly available in gyms and health clubs: cardio-focused dance classes, aerobics classes, and flexibility/muscular endurance classes.

Each of these kinds of styles builds a different type of fitness. Hip hop dance classes are combined with other workouts that challenge posture and endurance, such as breathing exercises and strength training. These help in endurance, a longer career, and speedy recoveries with injuries.

2. Choreography

What is the science of choreography? It’s a complicated question because perfection in dance is hard to define. However, each dance move is broken down into minute components, and dancers scientifically analyze each part.

Understanding the scientific aspects of dance allows them to evaluate and improve their own choreography, which is crucial as it denotes the plot and structure of dance routines.

To a scientist, perfection isn’t a visible quality. It is measurable through mathematical and statistical processes. Dance has something similar, which is called “perfect score.” Science is utilized in various dance genres, from contemporary to hip hop.

Modern ballet, for example, incorporates a lot of biomechanical principles and physiological principles, such as understanding the anatomy of the body and how the structure interacts with force to create motion.

Principles of physics and human physiology are used to improve the body’s efficiency and control. Mechanics help dancers proportion their weight to not overwork limbs, particularly hands and wrists.

Science is used to minimize frictional forces, leading to injuries such as pulled muscles, torn ligaments, and even joint damage.

In ballet, dancing a perfect pointe shoe means having one’s heel on the floor, and all toes pointed. A perfect pirouette is where the dancer does not lose her balance and keeps her feet in line with her hips, shoulders, and head while turning on one foot.

The excellent turnout shows that every leg muscle has been used to achieve the outside position of the foot joints in a turned-out position. Leg muscles aren’t allowed to make an effort during this movement. Every one of these moves has its base in science.

3. Mind-Body Relationship

It is vital for dancers to understand the relationships between their minds and their bodies as they must be able to control their bodies and allow them to put a soul in routines.

Investigating this is important, as we can see the human body as a complex machine, and dance requires very complicated manoeuvres which allow dancers to communicate with their bodies.

Due to this intimate relationship between mind and body, dancers are in a unique position to test the connection between the two, and how it plays a role in their performance.

Additionally, dance is gradually becoming especially important for the field of neuroscience. Researchers learn that dance, and the creative arts in general offer insight into disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders, and even mental disorders like depression.

Scientists study the mind-body relationship to better understand the link between thoughts, emotions, and the brain, focusing on how the brain reacts to and starts movement during dancing.

Dancers can quickly provide insights into how thought processes and movement because of the creative component involved in their performances.

The study of dance can reveal how spontaneous responses differ from movements (i.e., routines) that are practised or memorized. This has a basis in neuroscience.

The Conclusion

Dance is considered to be part of the arts, but it is interesting to realize that there is a large amount of science in dance.

Dance Science investigates it extensively. This area of study is an emerging, multi-disciplinary field that seeks to understand, not just the physical and aesthetic aspects of dance, but also the cognitive, emotional, social and spiritual reactions we have to movement and music.

From this viewpoint, dance is seen as a deeply-rooted human behaviour, and has an amazing impact on life.

What Is Dance Science? (with pictures)

`;

Hobbies

Fact Checked

Marisa O'ConnorDance science is one of the latest additions to the field of sports science. It is aimed at improving dancing performance and reducing injury. This field of science is also concerned with the neuroscience involved in dance and movement. Dancers can benefit a great deal from scientific principles, and science also has a lot to learn from the art of dance.

It is aimed at improving dancing performance and reducing injury. This field of science is also concerned with the neuroscience involved in dance and movement. Dancers can benefit a great deal from scientific principles, and science also has a lot to learn from the art of dance.

One of the first concerns of dance science is a dancers' health and performance. In this way, it can be considered similar to other sport sciences. This study of science is responsible for developing fitness routines for dancers that will keep them in the best possible physical and mental condition for dancing. Just as there are certain muscle groups baseball players work on, there are also specific exercises that benefit dancers more than any other sport. This science can also help speed recovery when dance-related injuries occur, but it is primarily concerned with preventing injury.

Just as there are certain muscle groups baseball players work on, there are also specific exercises that benefit dancers more than any other sport. This science can also help speed recovery when dance-related injuries occur, but it is primarily concerned with preventing injury.

Another aspect of dance science is using science to improve choreography and dance performance. Scientific principles are implemented to approach perfection in dance routines, particularly in classical ballet, but also in modern dance. Physics and logic are considered when choreographing new routines. Dance is primarily a form of expression, and the logical flow of one movement to the other can make or break the effectiveness of the dance's communication.

Dance is primarily a form of expression, and the logical flow of one movement to the other can make or break the effectiveness of the dance's communication.

Another one of the primary aspects of dance science is the understanding of the mind-body relationship while dancing. The word science comes from the latin word meaning knowledge. Dancers have a unique relationship to their bodies. They are able to memorize complicated routines, and communicate with their bodies in a way that no other sport or activity allows. Neuroscientists, in particular, stand to gain much knowledge about body memory and expression from dancers.

The brain is still full of informative treasures, waiting to be discovered by neuroscientists. Dance science can help researchers understand what is going on in the brain during dancing that is different than sitting or walking. The creative aspect of dancing also can provide quite a bit of insight into brain activity. Neuroscientists can study how the brain reacts to, and/or initiates movement during improvised routines, and how it is different than movement during memorized dance routines.

Dance science is also being used to bring more understanding and enjoyment of dance to the scientific community, as well as to bring more understanding and appreciation of science to the dance community. Many dance scientists argue that there is a lot of common ground between the two fields of study, and each can learn a lot from one another. Much interest is brewing around learning about science through dance, and dance and science workshops are popping up all over the U.K. to meet this demand.

Many dance scientists argue that there is a lot of common ground between the two fields of study, and each can learn a lot from one another. Much interest is brewing around learning about science through dance, and dance and science workshops are popping up all over the U.K. to meet this demand.

You might also Like

Recommended

AS FEATURED ON:

Dance as a Philosophy • Episode Transcript • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

Please change your browser settings.

Contents of the second lecture from Irina Sirotkina's course "What is modern dance"

It is believed that the goal of education is to get rid of imposed opinions, patterns, stereotypes. There are also many stereotypes about dance. Many people think, for example, that dancing is not an intellectual pursuit: intellectuals are not interested in dancing, and dancers do not read books. And it is also believed that it is better to dance than to talk or read about dance. Let's say right away: it's better - both. Moreover, one thing - dancing - is hardly possible without the other - without thinking, talking, reading about dance.

Stereotypes, alas, are peculiar not only to poorly educated people, but sometimes even to philosophers. Philosophy in the West and in our country has long ignored the body. The body has been the Cinderella of classical philosophy ever since, in the 17th century, René Descartes separated the thinking substance, res cogitans (or, literally, "the thing that knows"), from the material substance, res extensa, endowed only with the property of extension. Thought was thus incorporeal. But philosophers were only interested in it - thought. Already in the 19th century, Hegel declared that the subject of thought is an incorporeal spirit. This was probably due to the fact that philosophers took very little care of their own bodies and sat a lot.

Thought was thus incorporeal. But philosophers were only interested in it - thought. Already in the 19th century, Hegel declared that the subject of thought is an incorporeal spirit. This was probably due to the fact that philosophers took very little care of their own bodies and sat a lot.

Nevertheless, let's give Hegel his due: he considered sculpture to be the highest and most beautiful of all arts. And the favorite subject of sculptors is the human body. Hegel defined beauty as the conformity of form to an idea, as an expression of the eternal idea of beauty. These were the ancient sculptures of heroes, gods, sages-philosophers, whom everyone then admired. But dance is related to sculpture! Dance, like sculpture, is often classified as a plastic art. And at the beginning of the 20th century, a new dance appeared, which was called plastic. It is quite possible to imagine that dance is a sculpture in motion, plasticity is in dynamics.

Friedrich Nietzsche was the first to notice that in dance the body also becomes a work of art, which means that it also expresses an idea, a thought. Nietzsche literally turned classical philosophy upside down. And he did it not least with the help of dance. Like Isadora Duncan, Nietzsche loved antiquity and believed that in ancient Greece the highest stage of human development was reached - a golden age, which people then lost. In The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, Nietzsche composes a real ode to dance - an ancient and eternally young dance: “... man ... is ready to dance into the airy heights. Witchcraft speaks with his body movements. …He feels like a god.” And in the philosophical poem Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche writes: "I would only believe in a God who could dance." His Zarathustra dances with nymphs in green meadows. For Nietzsche, dance becomes an attribute of the highest, divine art and thought. Therefore, dance for Nietzsche is a metaphor for thought. The divine lightness of the dance is opposed to everything "serious, weighty, deep, solemn" - in a word, boring; opposes "the spirit of gravity, by which all things fall to the ground.

Nietzsche literally turned classical philosophy upside down. And he did it not least with the help of dance. Like Isadora Duncan, Nietzsche loved antiquity and believed that in ancient Greece the highest stage of human development was reached - a golden age, which people then lost. In The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, Nietzsche composes a real ode to dance - an ancient and eternally young dance: “... man ... is ready to dance into the airy heights. Witchcraft speaks with his body movements. …He feels like a god.” And in the philosophical poem Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche writes: "I would only believe in a God who could dance." His Zarathustra dances with nymphs in green meadows. For Nietzsche, dance becomes an attribute of the highest, divine art and thought. Therefore, dance for Nietzsche is a metaphor for thought. The divine lightness of the dance is opposed to everything "serious, weighty, deep, solemn" - in a word, boring; opposes "the spirit of gravity, by which all things fall to the ground. " Through the mouth of Zarathustra, the philosopher calls to "learn to fly", "to be light", "to dance not only with your feet, but also with your head" - that is, to be light and free in your thinking, just as a good dancer is free and light in dancing.

" Through the mouth of Zarathustra, the philosopher calls to "learn to fly", "to be light", "to dance not only with your feet, but also with your head" - that is, to be light and free in your thinking, just as a good dancer is free and light in dancing.

At that time, which is called the Silver Age in Russia, very many became Nietzscheans, spoke his language, using the metaphor of dance. The poet Andrei Bely dreamed that his works were "a dance of self-fulfilling thought." The same idea is echoed by today's Nietzscheans like the French philosopher Alain Badiou. For him, too, dance is “a metaphor for unsubdued, light, refined thought”, “a sign of the possibility of art inscribed in the body”. Free, unfettered, non-dogmatic thought is like a dance.

Nietzsche exclaimed: "And let the day be lost for us when we never danced!" The influence of this philosopher-dancer, not only on his colleagues in the workshop, but also on the dancers, can hardly be overestimated. Isadora Duncan loved to read Nietzsche and quoted him in her reflections on dance. She was not the only one: Nietzsche was also read by the German dancer, one of the creators of Art Nouveau, Mary Wigman. Wigman put one of her compositions on a chapter from Nietzsche's poem "Thus Spoke Zarathustra", which is called "Song-Dance". Maurice Béjart and many other dancers read Nietzsche. These are real intellectuals from dance, artist-thinkers. They created not only choreography, but also artistic manifestos and programs: Duncan wrote "Dance of the Future", Rudolf Laban - "The Dancer's World", Mary Wigman - "Philosophy of Modern Dance".

She was not the only one: Nietzsche was also read by the German dancer, one of the creators of Art Nouveau, Mary Wigman. Wigman put one of her compositions on a chapter from Nietzsche's poem "Thus Spoke Zarathustra", which is called "Song-Dance". Maurice Béjart and many other dancers read Nietzsche. These are real intellectuals from dance, artist-thinkers. They created not only choreography, but also artistic manifestos and programs: Duncan wrote "Dance of the Future", Rudolf Laban - "The Dancer's World", Mary Wigman - "Philosophy of Modern Dance".

What was the Nietzschean idea of these outstanding intellectual dancers? First, in the criticism of everything artificial. Isadora passionately criticized ballet for its alleged artificiality, conventionality, and the harm it does to the body. And she herself presented an alternative - a "natural" dance, similar to movement in nature. His examples are not six ballet positions (that is, several positions of arms and legs on which the entire choreography of classical ballet is based), but “wave vibrations and the rush of winds, the growth of living beings and the flight of birds, floating clouds and . .. human thoughts ... about the Universe ... ". Duncan considered one of the manifestations of the extreme artificiality of the ballet that the movements in it are fractional, isolated, do not follow from each other, are not connected with each other and "are unnatural, because they seek to create the illusion that the laws of gravity do not exist for them." On the contrary, in a free dance, the actions “should carry in themselves a germ from which all subsequent movements could develop” - approximately in the same way as evolution occurs in nature. Every person should dance, Isadora believed, and it will be his own, personal dance, corresponding not to ballet canons, but to the structure of his own body. In other words, she insisted on individuality, freedom, spontaneity in dance - motivating this by the fact that nature itself works this way. “Duncan is not just a name, but a program,” wrote one of her fans in Russia, art historian Alexei Sidorov.

.. human thoughts ... about the Universe ... ". Duncan considered one of the manifestations of the extreme artificiality of the ballet that the movements in it are fractional, isolated, do not follow from each other, are not connected with each other and "are unnatural, because they seek to create the illusion that the laws of gravity do not exist for them." On the contrary, in a free dance, the actions “should carry in themselves a germ from which all subsequent movements could develop” - approximately in the same way as evolution occurs in nature. Every person should dance, Isadora believed, and it will be his own, personal dance, corresponding not to ballet canons, but to the structure of his own body. In other words, she insisted on individuality, freedom, spontaneity in dance - motivating this by the fact that nature itself works this way. “Duncan is not just a name, but a program,” wrote one of her fans in Russia, art historian Alexei Sidorov.

German dancer Mary Wiegmann (real name - Marie Wiegmann) lived 86 years (1886-1973). By the way, this is far from the only case of longevity among dancers - it seems to me that these people, who were burning with their work, simply could not die and leave this work on earth. So, Wigman began to create her dances in a unique place - on the mountain of Truth, Monte Verita. This was the name of the community of artists, philosophers, anarchists, theosophists, vegetarians, nudists who set up a colony in Italian Switzerland, on the shores of Lake Maggiore. There at 19In the year 13, Rudolf Laban, the son of a field marshal from Austria-Hungary, arrived, who at that time was studying architecture in Paris. And here he began - like Zarathustra dancing in "round dances" - to lead his "moving choirs". It was like a pantomime performed by a group of people. Wigman, Suzanne Perrotte, and many other future dancers, creators of new styles - expressionism and modernity, participated in these "choirs" (where there was no music and songs, only movement and gestures). In the warm Swiss climate, they danced on the banks of Lago Maggiore, naked or half-clothed, celebrated mass to the sun, and thought up other rituals for the new, liberated humanity.

By the way, this is far from the only case of longevity among dancers - it seems to me that these people, who were burning with their work, simply could not die and leave this work on earth. So, Wigman began to create her dances in a unique place - on the mountain of Truth, Monte Verita. This was the name of the community of artists, philosophers, anarchists, theosophists, vegetarians, nudists who set up a colony in Italian Switzerland, on the shores of Lake Maggiore. There at 19In the year 13, Rudolf Laban, the son of a field marshal from Austria-Hungary, arrived, who at that time was studying architecture in Paris. And here he began - like Zarathustra dancing in "round dances" - to lead his "moving choirs". It was like a pantomime performed by a group of people. Wigman, Suzanne Perrotte, and many other future dancers, creators of new styles - expressionism and modernity, participated in these "choirs" (where there was no music and songs, only movement and gestures). In the warm Swiss climate, they danced on the banks of Lago Maggiore, naked or half-clothed, celebrated mass to the sun, and thought up other rituals for the new, liberated humanity. What the colonists on Monte Verita offered - given that at that very time a fratricidal world war was going on in Europe, in which Christians destroyed Christians - was not the worst offer to humanity.

What the colonists on Monte Verita offered - given that at that very time a fratricidal world war was going on in Europe, in which Christians destroyed Christians - was not the worst offer to humanity.

Almost all modern dance came from a small commune in the Swiss Alps. We have already mentioned Wigman - here she created her ingenious dance-rituals: she came up with her "Dance of the Witch", then she created the "Dance Song" to the words of Nietzsche, and later, with her students, staged "Monument to the Dead" ("Totenmal") . In her article "The Philosophy of Modern Dance" (1933), she wondered if classical ballet was possible after the World War. Wigman believed that dance should be updated - not only in terms of new movements, steps or steps, but also in terms of the seriousness of the questions that choreographers ask.

The Witch's Dance by Mary Wigman. 1920s

1920s In addition to Wigman, other modern choreographers also began to address current political and existential questions, questions about life. Kurt Joss staged the contemporary ballet "Green Table" - about those negotiations that European diplomats failed, which led to the world war. Pina Bausch began to study with Joss - she later created her own dance theater in the German city of Wuppertal, one of the most famous in the world. In the 20th century, along with dance-entertainment, a dance-reflection, dance-satire appeared. This is the result of real intellectual dancers appearing—or, as in the case of Laban, intellectuals began to dance, to become dance artists.

They opposed themselves to the light entertainment genre that ballet was traditionally considered to be. It must be said that in the 18th and 19th centuries ballet served as light entertainment, divertissement: ballets in the theater were given in intermissions between two short operas or between two acts of an opera, and often it was called that - ballet divertissement (divertissement in French "entertainment") . To distance themselves from this tradition, the new choreographers called their style not ballet, but modern dance. Modern included Mary Wigman, Kurt Joss and other students of Laban in Europe, and in the USA Martha Graham and other dancers. In our country, modern dance began to develop successfully in 1920s, but was banned for ideological reasons. After that, academic ballet reigned for a long time, and other genres (except, perhaps, folk stage dance) became marginal.

To distance themselves from this tradition, the new choreographers called their style not ballet, but modern dance. Modern included Mary Wigman, Kurt Joss and other students of Laban in Europe, and in the USA Martha Graham and other dancers. In our country, modern dance began to develop successfully in 1920s, but was banned for ideological reasons. After that, academic ballet reigned for a long time, and other genres (except, perhaps, folk stage dance) became marginal.

At first, classical ballet remained aloof from the processes that took place in modern dance. However, here, too, choreographers-philosophers appeared who staged meaningful performances. Maurice Bejart also belonged to the dancing philosophers, or philosophizing dancers (he left us relatively recently, in 2007). His real name is Berger; he is the son of the philosopher Gaston Berger, who, in particular, wrote a treatise on Husserl's phenomenology. Maurice graduated from the Lyceum with honors in philosophy, and then he took and went to study classical dance. As in philosophy, he was also successful in ballet - despite his small stature and short legs, he performed the title role of Siegfried in Swan Lake.

As in philosophy, he was also successful in ballet - despite his small stature and short legs, he performed the title role of Siegfried in Swan Lake.

In the mid-1950s, Béjart founded his first company and staged his first ballet, La Symphonie for a Solo Man (La Symphonie pour un homme seul) to "concrete music" by contemporary composer Pierre Henry. Specific music was an electronic compilation of musical fragments, sounds of nature and household noises - for example, factory horns. The music alone provoked the audience - there really was a scandal at the premiere. Moreover, the theme is not typical for ballet: existentialism, loneliness, anxiety. These sentiments, however, were very typical of those years when Jean-Paul Sartre was the most popular philosopher. Bejart, thus, immediately declared himself as a choreographer-philosopher. And five years later he finally read Nietzsche, and this reconciled his two strongest passions - philosophy and dance. And his dance changed, became more powerful, passionate and vital. Having created a new company - "Ballet of the 20th century", Bejart turns to ancient myths, in which movement, dance have a sacred meaning, and puts on the ballets "Orpheus", "The Rite of Spring", "Sacrifice".

Having created a new company - "Ballet of the 20th century", Bejart turns to ancient myths, in which movement, dance have a sacred meaning, and puts on the ballets "Orpheus", "The Rite of Spring", "Sacrifice".

In 1961 Béjart staged perhaps his most popular ballet, Boléro. Bejart's favorite dancer Argentine Jorge Donn, Maya Plisetskaya, Sylvie Guillem shone in it ... Bejart was not the first to turn to Ravel's music. In fact, this composition was composed by Ravel at the request of the dancer Ida Rubinstein. The ballet "Bolero" was staged for her by the sister of the famous Vaslav Nijinsky, the wonderful performer and choreographer Bronislava Nijinsky herself. The ballet takes place in a tavern, and in the finale, Ida jumped on the table and danced on it, surrounded by enthusiastic male patrons. If you have seen Béjart's "Bolero" (or you can watch it right now), then you know that this dance is also performed on a raised platform. But due to a completely different choreography, idea, mood, this dance is more like not drunken fun in a pub, but a very serious and passionate sacrificial ritual. Even Bejart's table is not a table, but an altar on which sacrifice is made.

Even Bejart's table is not a table, but an altar on which sacrifice is made.

Such was the increased seriousness and even sacredness of modern dance in comparison with its predecessor, classical ballet of the 19th century. It should be added that Bejart himself converted to Islam in the late 1960s, but Buddhism was also close to him. And he called his last dance schools "Mudra" (which means "gesture" in Hindi) - in Brussels, and "Rudra" (after the name of the deity) - in Lausanne. Over the past twenty years, Béjart has staged almost a hundred ballets, including, a year before his death, Zarathustra: Song and Dance. Zarathustra for him is a philosopher, a prophet, a legislator, a dancing god who dances with his feet and head.

More to read:

Badiou A. A small guide to inaesthetics. St. Petersburg, 2014.

A small guide to inaesthetics. St. Petersburg, 2014.

Bezhar M. A moment in the life of another. Memoirs. M., 1989.

Valerie P. On Art. Soul and dance. M., 1993.

Duncan A. Dance of the future.

Nietzsche F. Thus spoke Zarathustra.

11 words to help you understand the culture of French-speaking Belgium

Constant rains, carnival processions, hundreds of beers and the most complicated state structure. We talk about French-speaking Belgium in the new issue of the series about languages and countries

Want to be aware of everything?

Subscribe to our newsletter, you'll love it. We promise to write rarely and in the case of

courses

All courses

Special projects

Audiolects

10 minutes

1/7

What is a dance

What is the usual movement different from the dance, which is studied by biomechanics and kinesiology and how at the beginning of the 20th century, the attitude towards the body changed

Reading by Irina Sirotkina

How does ordinary movement differ from dance, what is studied by biomechanics and kinesiology, and how the attitude to the body changed at the beginning of the 20th century

16 minutes

2/7

Why God must 9008 dance and how choreographers started talking about loneliness, the future of mankind and the causes of the First World War

Reading Irina Sirotkina

Why God must dance in Nietzsche and how the choreographers started talking about loneliness, the future of mankind and the causes of the First World War

13 minutes

3/7

What is the difference between dance and dance

Why should the authorities control folk festivals, what is the utopia of ecstatic dancing and what is the danger of an undisciplined body

ecstatic dance and what is dangerous about an undisciplined body

13 minutes

4/7

Dance: element or art?

Why teach natural movement, how to make a dancer a "non-human" being, and what do pointe shoes and bioprostheses have in common 915 minutes attractiveness of acrobatics and why it is more interesting to look at dance if you have tried to dance yourself

Reads by Irina Sirotkina

Where does dexterity come from, what is the attractiveness of acrobatics and why is it more interesting to look at dance if you have tried to dance yourself

14 minutes

6/7

The ideal body for dancing

How does a ballet body differ from a jazz one, why Martha Graham would not tolerate virgins in her troupe and is it possible to be able to dance everything

different from jazz, why Martha Graham would not tolerate virgins in her troupe and is it possible to be able to dance everything

12 minutes

7/7

Dance as desire

What ordinary movements of an untrained body can tell about what shocked the audience in Isadora Duncan and why dance is a desire machine

Reading by Irina Sirotkina

What ordinary movements of an untrained body can tell about, what shocked the audience in Isadora Duncan and why dance is a desire machine

Materials

9 languages of modern dance

How to recognize Pina in several movements

What was danced in the 20th century

The most fashionable dances of salons and discos and the most daring phenomena of choreography in 100 years

The history of modern dance in 31 productions

Ballets, plays and performances that have changed the idea of choreography

Test: Distinguish ballet from opera culture

What Madonna, Andy Warhol and Charlie Chaplin borrowed from the main choreographers of the 20th century

0004 OdnoklassnikiVKYouTubePodcastsTwitterTelegramRSS

History, literature, art in lectures, cheat sheets, games and expert answers: new knowledge every day

© Arzamas 2022. All rights reserved

All rights reserved

What should I do to avoid losing my subscription after Visa and Mastercard leave Russia? Instructions here

the problem of origin and definition0001

UDC 130.2

E.S. Pshikova

Siberian State University of Physical Culture and Sports

Omsk

DANCE AS A KIND OF HUMAN ACTIVITY: THE PROBLEM OF ORIGIN AND DEFINITION

The problem of the origin of dance culture and dance as its particular manifestation is considered. The purpose of writing the article is to study the basic concepts (cosmological, biological and social) that study the origins of dance and determine the essential aspects of the concept of "dance". The idea is substantiated that the origin of dance depends not only on external factors (environment) that affect the development of a cultural phenomenon, but also on external factors (need for movement) that stimulate a person to change the world around him. Particular attention is paid to an attempt to synthesize existing theories regarding the problem of the origin of dance and its definition. The author proposes a new definition of the concept of "dance", which includes key points in the study of this cultural phenomenon. The scientific community still cannot come to a consensus on the topic put forward, so the question of the origins of the origin of the dance with convincing arguments continues to be debatable. Key words: culture, rhythm, genesis, dance, language of culture.

The author proposes a new definition of the concept of "dance", which includes key points in the study of this cultural phenomenon. The scientific community still cannot come to a consensus on the topic put forward, so the question of the origins of the origin of the dance with convincing arguments continues to be debatable. Key words: culture, rhythm, genesis, dance, language of culture.

Throughout its history, humanity has been continuously interacting with the environment, and the processes of the influence of objects on each other, their mutual conditioning and the processes of generation by one object of another occur indirectly - through the human body. Cognition of the world occurs by fixing sensations, sights, smells, sounds. At the earliest stage of human development as a biological species, this fixation was prevalent, the body was the main source of information about the world around us, but over time, interest in the human body faded into the background, giving way to moral laws and the triumph of reason.

At present, one can observe a huge number of different bodily practices that revive interest in the human body. This is confirmed by the wide spread of martial arts techniques, the emergence of new dance styles and their popularization, the formation of a youth policy aimed at the development of sports through events related to the demonstration of the human body (beauty contests, bodybuilding, etc.), as well as by the media . This situation refers us to the patterns of development of the semiosphere proposed by Yu.M. Lotman, where cultural phenomena arise, develop and move in the space of the entire culture, moving from its center to the periphery and vice versa [6, p. 351]. Today, bodily practices occupy one of the central places in the development of modern culture. Since by culture in a broad sense we understand everything that is created by a person in the process of his active activity, then bodily practices, as its particular manifestations, can also be classified as human activity that forms and transforms the human environment.

Bodily practices represent a wide range of manifestations: the position of the human body in space, established forms of behavior in a particular situation, algorithms of human actions in a certain situation - all these manifestations are described in great detail in ethnographic essays, works devoted to the culture of everyday life. Each society, developing in a certain territory, develops its own habits, value orientations, consolidates the experience gained. So, for each people, society, culture, a certain technique of movements, rituals, dances is formed, directly

related to body movement techniques. These forms of bodily practices take on their own forms and become an integral part of every culture.

Bodily practices permeate all human life, existing both in everyday life and on special occasions - holidays, sacred rituals, rituals. A striking example of bodily practice that functions in everyday life and in solemn situations is dance, which also pursues an aesthetic component.

Dance and, as its broader embodiment, dance culture are closely connected with the history of mankind as a whole. At its core, it is one of the types of aesthetic embodiment of human consciousness in reality, but along with other types of art, it arose earlier. As some researchers point out, “based on the evidence we know about people of the ancient Stone Age, we can conclude that musical and dancing activity was also inherent in the distant paleoanthrope (which is confirmed by finds 25-35 thousand years ago)” [2, p. 9]. The art of dance is inherent in all peoples inhabiting the planet, so we can conclude that the phenomenon of dance itself does not depend on any particular territory (local affiliation determines only the individual characteristics of a particular dance, giving rise to ethnic dances). Thus, it is obvious that dance is a cultural phenomenon that not only refers to a certain tradition, but also speaks of a universal belonging.

The genesis of any cultural phenomenon, and in this case dance, is not only the moment of origin, but also the subsequent process of development and change of the phenomenon, both gradual and abrupt. Thus, studies of the origin of dance will allow not only to take a fresh look at this cultural phenomenon, but also to assess its significance in the development of culture as a whole from a different point of view.

Thus, studies of the origin of dance will allow not only to take a fresh look at this cultural phenomenon, but also to assess its significance in the development of culture as a whole from a different point of view.

Probably, the phenomenon of dance arose from the need of a person to express his inner world through the movement of the body, to show his involvement in the surrounding world, to feel like a part of something greater. However, there is still no consensus in the scientific community regarding the nature of dance, about what was the impetus for its appearance. There is a large amount of visual, textual, graphic material that describes the dance, considering the dance culture from many angles. The variety of descriptive material has given rise to cultural pluralism regarding the problem of the origin of dance.

The origin of dance, like any other phenomenon of human culture, depends on both external and internal factors, which makes it possible to talk about the synthesis of circumstances that influence the emergence and further development of dance culture as a whole. Currently, research is underway in the field of the genesis of dance, but there is no new unified point of view on this problem yet, therefore, at this stage in the development of science in the field of dance art, there are three main concepts.

Currently, research is underway in the field of the genesis of dance, but there is no new unified point of view on this problem yet, therefore, at this stage in the development of science in the field of dance art, there are three main concepts.

The cosmological concept led by H. Ellis assumes a direct relationship between dance and the Universe. According to this theory, the rhythm-forming principle forms the basis of the cosmos as a world order. Dance, in turn, arises under the influence of rhythm - in this, according to Ellis, there is a key similarity through which the relationship of dance to the cosmos, as part to the whole, is subsequently built. The rhythm-forming beginning is the essence of the dance, because he is “a phenomenon in which everything is subject to strict rules for calculating rhythm, meter and order, strict adherence to the general laws of form and clear subordination of a part of the whole” [4, p. 9].

Scientists who defend the biological concept of the origin of dance believe that the dance occurred as a result of the ritualization of behavioral stereotypes. The fauna is replete with examples of dance-like mating rituals of birds, synchronous group "dances" of fish, butterflies, bees, etc. These examples point to a general biological need for orderly movements that facilitate the transmission of valuable information. So, biologist

The fauna is replete with examples of dance-like mating rituals of birds, synchronous group "dances" of fish, butterflies, bees, etc. These examples point to a general biological need for orderly movements that facilitate the transmission of valuable information. So, biologist

M. Ichas notes: “it is striking not so much that the bees “dance”, but that other individuals are able to understand the meaning of the dance and be guided by it in their own behavior” [3, p. 245].

Based on this, we can conclude that the belonging of a person to living nature, the identification of similarities in the ordering of certain movements in humans and animals speaks of the biological nature of the first dances. That is, a person is characterized by sensory-emotional reactions to certain phenomena of reality, which, although they change, still retain their biophysiological nature and go back genetically to the corresponding reactions of animals. Perhaps that is why many primitive dances were somewhat similar to animal dances, but there are still differences in these dances. And the main difference lies in the nature of the dance movements. In animals, “dances” are innate, and in the case of humans, there is a moment of learning. A person first learns to dance, and then demonstrates his skills. In addition, the movements in primitive dances largely imitated the phenomena of the surrounding world and did not yet record innate talents. Moreover, “endowing the environment with an inner sacred meaning and trying to symbolically influence it, primitive man imitated the habits of animals, trying to imitate them” [2, p. 85].

And the main difference lies in the nature of the dance movements. In animals, “dances” are innate, and in the case of humans, there is a moment of learning. A person first learns to dance, and then demonstrates his skills. In addition, the movements in primitive dances largely imitated the phenomena of the surrounding world and did not yet record innate talents. Moreover, “endowing the environment with an inner sacred meaning and trying to symbolically influence it, primitive man imitated the habits of animals, trying to imitate them” [2, p. 85].

Another point of view presents a sociological view of the origin of dance. Proponents of this approach understand dance as a phenomenon that is determined by the socio-cultural life of a person. That is, representatives of the sociological concept consider dance as a kind of model of communicative communication, “focusing in itself the most common motor-motor patterns that are most often and successfully used in the lives of most people of this cultural community” (A. Lomax) [6, p. 16].

Lomax) [6, p. 16].

Many research projects dealing with non-verbal communication systems raise the question of the social conditioning of expressive means. And yet, there is a lot of evidence in favor of the hypothesis of dance movements as innate gestures. I.A. Gerasimova argues that it is necessary to distinguish between a person's personal beginning, which is culturally determined, and the individual beginning, on which social conditions do not have any effect, and this is only the realization of internal potentials, possibly genetically incorporated. She says that the emergence of dance took place along two interdependent directions - both socially determined and innate.

As you can see, there are quite a few critical opinions regarding the concepts presented. However, there are reasonable grounds for all these approaches. If all three concepts are combined, then together they will give more information about the nature of dance and help to consider this phenomenon from a different angle of vision. After all, a person, as a representative of a biological species, is also subject to the general laws of nature, and one of the organizing principles of nature is rhythm. Often, the external influence of rhythm on a living being, including a person, has a direct physiological effect. There are many scientific works aimed at studying and reproducing the main natural rhythms, possibly universal, which have either a calming or activating effect on a person [10, p. 329-322], but this is already beyond the scope of our subject field. And already under the influence of internal and external factors, a person is forced to build communication with other people, and often such communication occurs on the basis of dance-like movements, which subsequently evolve and become an independent type of human creative activity.

After all, a person, as a representative of a biological species, is also subject to the general laws of nature, and one of the organizing principles of nature is rhythm. Often, the external influence of rhythm on a living being, including a person, has a direct physiological effect. There are many scientific works aimed at studying and reproducing the main natural rhythms, possibly universal, which have either a calming or activating effect on a person [10, p. 329-322], but this is already beyond the scope of our subject field. And already under the influence of internal and external factors, a person is forced to build communication with other people, and often such communication occurs on the basis of dance-like movements, which subsequently evolve and become an independent type of human creative activity.

If we delve not into the genetic roots of dance, but try to reveal its commonality with other types of human activity, then a different picture emerges. By its very nature, dance is an art form. Actually, in almost all encyclopedic publications, it is defined in this way. This generic attribute points to the entity

Actually, in almost all encyclopedic publications, it is defined in this way. This generic attribute points to the entity

dance, but there are details that make it possible to more specifically determine the place of dance among other art forms. So, according to the form of being of artistic images, that is, according to its ontological status, dance is a kind of spatio-temporal art. It is also worth noting the special figurative expressiveness of movements that are born from the power of rhythm, which sets the main vector of dance development. Therefore, it would be more accurate to say that dance is “a type of space-time art, the artistic images of which are created by means of aesthetically significant, rhythmically systematized movements and poses” [4, p. 21].

There are many points of view regarding the nature of dance, its structure, relationship with other areas of human activity, and all of them are correct in their own way, since they consider dance art from a special angle. But one can see unity in these theories - all versions consider dance as a phenomenon, one way or another dealing with messages expressed through dance “pas”. That is, it would be legitimate to call dance one of the means of communication in human society - which gives new material for thinking about the communicative component in dances.

But one can see unity in these theories - all versions consider dance as a phenomenon, one way or another dealing with messages expressed through dance “pas”. That is, it would be legitimate to call dance one of the means of communication in human society - which gives new material for thinking about the communicative component in dances.

Yuri Mikhailovich Lotman, a representative of national cultural studies, was closely involved in the issues of communications in culture. For him, culture was a device that generates, transmits and stores information, and, in fact, all manifestations of culture (phenomena that reproduce) were considered by the researcher as mechanisms of culture. In his works, Lotman defines the basic concepts of semiotics (text, code, language, sign), which gradually becomes the basis for a communicative analysis of the entire culture. Such a semiotic approach makes it possible to study individual cultural forms, such as dance, considering them from the point of view of cultural languages that can provide information about the culture within which a particular cultural phenomenon was formed.

Thus, we can say that at the moment of the development of the science of dance culture there is a lot of applied, "field" information that requires analytical and systematic processing. At the same time, existing concepts that consider dance from different points of view represent a spectrum of meanings built on reasonable grounds and sufficiently reasoned. Together, these theories provide a detailed overview of the dance and allow you to judge this phenomenon more freely, going beyond the scope of choreographic analysis.

The synthesis of the basic concepts that study the origin of dance and the mechanism of its existence allows us to say that dance is a natural phenomenon, genetically embedded in a person, which manifests itself under the influence of some music or just rhythm and serves to transmit and receive information. Dance is the language of culture and undoubtedly contains elements that testify to its communicative nature.

It can be said that dance is a text created in a special language, and, being one of the most widespread phenomena of human culture, it can help reconstruct the cultural space of a person of any era. In order to actively use dance in the analysis of any historical period or a certain area, it is necessary to study in detail and carefully the mechanism of its functioning and more accurately determine its origins, because the available information about the genesis of dance will allow us to understand its formation, development, understand transformations and, possibly, predict dance culture crisis.

In order to actively use dance in the analysis of any historical period or a certain area, it is necessary to study in detail and carefully the mechanism of its functioning and more accurately determine its origins, because the available information about the genesis of dance will allow us to understand its formation, development, understand transformations and, possibly, predict dance culture crisis.

References

1. Vashkevich, N.N. History of choreography of all centuries and peoples / N.N. Vashkevich. - M .: Planet of music, 2009. - 192 p.

2. Gerasimova, I.A. Dance: the evolution of kinesthetic thinking / I.A. Gerasimova // Evolution. Language. Cognition / Institute of Philosophy RAS; under total ed. I.P. Merkulov. - M.: Languages of Russian culture, 2000. -S. 84-112.

3. Ichas, M. On the nature of the living: mechanisms and meaning / M. Ichas. - M. : Nauka, 1994. - 245 p.

4. Koroleva, E.A. Early forms of dance / E.A. Queen. - Chisinau: Shtiintsa, 1977 . - 215 p.

- 215 p.

5. Lotman, Yu.M. Conversations about Russian culture. Life and traditions of the Russian nobility / Yu.M. Lotman. -SPb. : Art - St. Petersburg., 1994. - 399 p.

6. Lotman, Yu.M. Semiosphere: culture and explosion. Inside the thinking worlds / Yu.M. Lotman. - St. Petersburg. : Art - St. Petersburg., 2000. - 703 p.

7. Mechkovskaya, N.B. Semiotics: Language. Nature. Culture / N.B. Mechkovskaya. - M. : Academy, 2008. -

432 p.

8. Morina, L. Ritual dance and myth / L. Morina. - M. : Nauka, 2005. - 86 p.

9. Romm, V.V. Ancient dances / V.V. Romm. - Novosibirsk, ZSO MSA, 2011. - 306 p.

10. Suleimanov, R.F. Music and mental states: influence, interaction or mutual assistance // Psychology of mental states: theory and practice / R.F. Suleimanov // Proceedings of the First All-Russian scientific and practical. conf. Kazan State University, November 13-15, 2008 Part II. - Kazan: New knowledge, 2000. -S. 329-332.

11. Tsvetkov, V. N. Music as a factor in increasing the effectiveness of sports / V.N. Tsvetkov, V.I. Shaposhnikova // Physical culture: upbringing, education, training. - M., 2009. - No. 5. - S. 45-46.

N. Music as a factor in increasing the effectiveness of sports / V.N. Tsvetkov, V.I. Shaposhnikova // Physical culture: upbringing, education, training. - M., 2009. - No. 5. - S. 45-46.

12. Yagodinsky, V.N. Rhythm! Rhythm! Rhythm! Etudes of Chronobiology / V.N. Yagodinsky. - M.: Knowledge, 1985. - 192 p.

E.S. Pshikova

Siberian State University of Physical Culture and Sport DANCE AS A FORM OF HUMAN ACTIVITY: THE PROBLEM OF ORIGIN AND DEFINITION

A culture is all that human created in the process of his activity. Dance as a form of bodily practices is a vivid example of cultural phenomenon, that performed functions of creating meaning, communication and aesthetics direction. Today scientific society is facing a problem of origin and definition of dance. We are facing the questions: when has dancing culture emerged? What was the reason for the emergence of dance? There are 3 main concepts of the emergence of dance. First, cosmological theory supposes emergence of the dance from rhythm-forming base of Universe, i. e. dance as a part of the world arises and develops under the influence of the rhythm. Second, biological concept states that the dance emerged as a result of ritualization of behavioral patterns. Third, the pioneers of sociological theory think that the emergence of dance takes roots in human's need of communication with other members of the group by means of the movement. All these theories have reasonable evidence and consider the dance from a different side. Synthesis of these concepts allows us to say that the dance is a natural genetically inherited phenomenon that is expressed under the influence of music or rhythm and serves for sending and receiving information. Scientists that are using dance could reconstruct any historical epoch.

e. dance as a part of the world arises and develops under the influence of the rhythm. Second, biological concept states that the dance emerged as a result of ritualization of behavioral patterns. Third, the pioneers of sociological theory think that the emergence of dance takes roots in human's need of communication with other members of the group by means of the movement. All these theories have reasonable evidence and consider the dance from a different side. Synthesis of these concepts allows us to say that the dance is a natural genetically inherited phenomenon that is expressed under the influence of music or rhythm and serves for sending and receiving information. Scientists that are using dance could reconstruct any historical epoch.

Key words: culture, rhythm, genesis, dance, cultural language.

References

1. Vashkevich N.N. Istorija horeografii vseh vekov i narodov [History of choreography of all centuries and nations]. Moscow, Planeta muzyki, 2009, 192 p.

2. Gerasimova I.A. Dance: evolution of kinesthazitically thinking. Jevoljucija. Jazyk. Knowledge. Moscow, 2000, pp. 84-112.

3. Ichas M. Oprirode zhivogo: mehanizmy i smysl [About the nature of the living: mechanisms and meanings]. Moscow, Nauka, 1994, 245 p.

4. Koroleva E. A. Rannie formy tanca [Early forms of dance]. Kishenev and Shtiinca, 1977, 215 p.

5. Lotman U.M. Talk about Russian culture. Byt i tradicii russkogo dvorjanstva [Discussions about Russian culture. Everyday life and traditions of the Russian nobility]. St. Peterburg, Iskusstvo - SPB, 1994, 399 p.

6. Lotman U.M. Semiosfera: kul'tura i vzryv. Vnutri mysljashhih mirov [The semi: culture and explosion. Inside thinking worlds]. St. Peterburg, Iskusstvo - SPB, 2000, 703 p.

7. Mechkovskaja N.B. Semiotika: Jazyk. Nature. Kul'tura [Semiotics: The Language. Nature. culture]. Moscow, Akademija, 2008, 432 p.

8. Morina L. Ritual'nyj tanec i mif [Ritual dance and myth]. Moscow, Nauka, 2005. 86 p.

Moscow, Nauka, 2005. 86 p.

9. Romm V.V. Ancient dances [Ancient dances]. Novosibirsk, ZAO MSA, 2011. 306 p.

10. Sulejmanov R.F. Music and mental state: the impact, interaction or vzaimosodeistviya. Psihologija psihicheskij sostojanij: teorija i praktika. Materialy Pervoj Vserossijskoj nauchno-prakticheskoj konferencii. 2000, vol. 2, pp. 329-332.

11. Cvetkov V.N. Music as a factor of increase in efficiency of sports. Fizicheskaja kul'tura: vospitanie, obrazovanie, training. 2009, vol.5, pp. 45-46.

12. Jagodinskij V.N. rhythm! rhythm! rhythm! Jetjudy chronobiologii [The rhythm! The rhythm! The rhythm! Etudes chronobiology]. Moscow, Znanie, 1985, 192 p.

© Pshikova E.S., 2014

Author of the article - Ekaterina Sergeevna Pshikova, post-graduate student, Siberian State University of Physical Culture and Sports, e-mail: [email protected].

Reviewers:

O.F. Vinogradova, candidate of pedagogical sciences, secondary school No. 54, Omsk; D.V. Konstantinov, candidate of philosophical sciences, Siberian State University of Physical Culture and Sports.

54, Omsk; D.V. Konstantinov, candidate of philosophical sciences, Siberian State University of Physical Culture and Sports.

UDC 130.2

N.Yu. Shchelkanova

Omsk State Pedagogical University

PROPERTIES AND ANTI-THINGS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF THE PAST AND THE FUTURE

The thing is considered in the context of the future and the past as independent categories, demonstrating the inevitability of tactile and visual representations within them. The assessment of the importance of a thing both for the past and for the future is ambiguous, since it includes not only thingsist, but also anti-thingish views. The vision of the ideal structure of society, together with the ideal material environment, is viewed through the prism of the mythical "golden age", carried forward or backward in time. The novelty of this study is associated with an unusual perspective of considering the categories of the past and the future. Key words: thing, materialism, past, future.

Along with other values, the thing plays a significant role in the dynamics of the development and change of culture. Despite the obvious need to possess some things, human history notes a very ambiguous attitude towards it as such and its relationship with man.

For two chronological dimensions, past and future, let's try to give an approximate assessment of the relationship with the thing. Here, the past acts as an independent category and is considered not within the framework of historical epochs, but precisely as the "past" for any period - that which has already been. The future is also not defined by chronological frames and real forecasts, but refers to how it is foreseen at any time. Such a context of ideas about the past and the future is immanently present in any historical epoch and in each individual.

Going about daily activities, a person is often occupied with thoughts of completely extraneous things, his mind is directed to pondering what has already happened, or dreaming about what has not yet happened.