How do you dance in creative destruction

Creative Destruction Collaborative - Feast — Curated Storefront

Christina Lindhout and Corrie Slawson

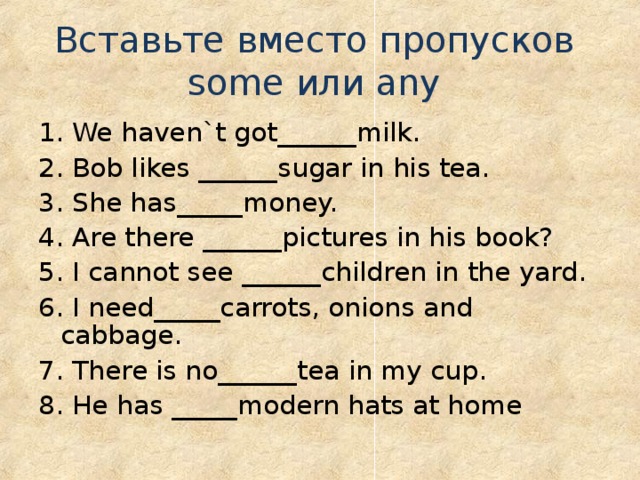

FeastCombination of sculpture/paintings/installation as well as digital media depicting the choreographic process of a ballet

About the Exhibit

Feast is a product of the performance collective, Creative Destruction. The collective includes Verb Ballets Principal dancers Christina Lindhout and Kelly Korfhage, and Artist Corrie Slawson. The narrative is a group effort with special expertise brought by University of Dayton Professor of Law Dr. Dalindyebo Shabalala, an expert and UN Presenter in Climate Change and Human Rights and Cleveland Museum of Natural History Director of Sustainability Marc Lefkowitz. Creative Destruction, an economics term coined by Joseph Schumpeter, is the accepted shorthand for free market capitalism. It proffers that short-term growth and job loss are natural results of economic growth. This appetite for constant growth is also linked to environmental degradation. Creative Destruction’s finished form will be a classical ballet with objects to illustrate the interconnectivity of environmental degradation, trade, economic theories and wealth distribution.

A combination of real, sculptural and store-bought objects with the movement of dancers will convey the complex narratives of six commodities: Sugar, Bananas, Coffee, Timber, Oil & Minerals and Beef. Creative Destruction explores these complexities through the interaction between dancers and objects to better communicate these theories to a general audience.

Location

O’neil Building

222 King James Way, Akron, OH, 44308

About the ARtists

Christina Lindhout:

Christina Lindhout been a company dancer with Verb Ballets in Cleveland, Ohio since August 2014. During that time, she has performed principal and leading roles in over 40 contemporary and classical ballets. Eighteen of these pieces were new choreographic works, created by acclaimed international choreographers. Christina has also performed as a principal dancer with the Cleveland-Havana Ballet Project in Havana, Cuba as well as with Body EDT at the National Theater in Tapei, Taiwan. She trained extensively with American Ballet Theater, BalletMet Columbus, Joffrey Midwest, the Orlando Ballet School, and Ashland Regional Ballet and has over 22 years of classical ballet training. Christina also has 18 years of jazz and Horton-based modern training. As a teacher, Christina has taught all levels and ages (3-99 years old) in classical ballet, pointe, jazz, modern, and tap. In 2019, she was named the School Director at Verb Ballets' Center for Dance as well as Adjunct Faculty in the Dance Department at Baldwin Wallace University. Most recently, in 2020, she and Corrie Slawson were awarded a Satellite Fund grant through SPACESCle and the Andy Warhol Foundation as on behalf of the Creative Destruction Collaborative. The grant was awarded for production of the Collaborative’s first work, a contemporary ballet and art installation entitled Feast.

Christina has also performed as a principal dancer with the Cleveland-Havana Ballet Project in Havana, Cuba as well as with Body EDT at the National Theater in Tapei, Taiwan. She trained extensively with American Ballet Theater, BalletMet Columbus, Joffrey Midwest, the Orlando Ballet School, and Ashland Regional Ballet and has over 22 years of classical ballet training. Christina also has 18 years of jazz and Horton-based modern training. As a teacher, Christina has taught all levels and ages (3-99 years old) in classical ballet, pointe, jazz, modern, and tap. In 2019, she was named the School Director at Verb Ballets' Center for Dance as well as Adjunct Faculty in the Dance Department at Baldwin Wallace University. Most recently, in 2020, she and Corrie Slawson were awarded a Satellite Fund grant through SPACESCle and the Andy Warhol Foundation as on behalf of the Creative Destruction Collaborative. The grant was awarded for production of the Collaborative’s first work, a contemporary ballet and art installation entitled Feast. For Feast, Corrie is the lead producer and visual artist/sculptor, and Christina is the lead choreographer and co-producer. Also in 2020, Christina was awarded an Akron Soul Train Fellowship in support of her choreography on Feast.

For Feast, Corrie is the lead producer and visual artist/sculptor, and Christina is the lead choreographer and co-producer. Also in 2020, Christina was awarded an Akron Soul Train Fellowship in support of her choreography on Feast.

Corrie Slawson:

Corrie Slawson’s work is a result of a journalistic survey of properties and land; she builds city/landscapes that underscore development patterns of population loss and land-use that emerge through layers of printmaking, drawing and painting. Her work has been exhibited in the US and internationally, including at MOCA Cleveland, The Toledo Museum of Art, Akron Art Museum, Centro Culturel de Tijuana, SPACES and Zygote Press. Corrie earned her BFA at Parsons School of Design (NY) and her MFA at Kent State University. Her work is represented by Shaheen Modern and Contemporary in downtown Cleveland.

Her practice is a lab-like experimentation with system and process in service of content. The “places” depicted analyze overarching patterns in development, population loss, land-use, climate change and environmental equity. Source imagery for these mixed media works is garnered from her own travels, experiences and commutes (abroad, domestic, and local). No matter the location, she finds visual language extant in the surroundings—color, architecture, texture and reflective materials, her work also mirrors movement through spaces: walking past city blocks or sun glare on the car window. In many cases, she features notable and obscure visual references that bring our own regions’ lifecycle of suburban sprawl and urban divestment to the forefront.

Source imagery for these mixed media works is garnered from her own travels, experiences and commutes (abroad, domestic, and local). No matter the location, she finds visual language extant in the surroundings—color, architecture, texture and reflective materials, her work also mirrors movement through spaces: walking past city blocks or sun glare on the car window. In many cases, she features notable and obscure visual references that bring our own regions’ lifecycle of suburban sprawl and urban divestment to the forefront.

Website

Creative Destruction Collective – FEAST: a ballet

Corrie Slawson

Artist Corrie Slawson’s work explores landscapes related to social and environmental equity, made through layers of printmaking, painting and other mixed media. Visual references to the history of Cleveland’s regional lifecycle are repeated throughout America’s Gilded age of unchecked wealth and growth imperiled by decision-making stuck in cycles of sprawl, divestment and racism. Corrie’s work can be seen in permanent public collections including The Cleveland Clinic Collection, University Hospitals Cleveland, Metro Health and Progressive Insurance. Nationally, her work has exhibited The Toledo Museum of Art, The Peoria Art Guild, Rockford Art Museum, and at her BFA Alma Mater, Parsons School of Design. Internationally her work has been exhibited at in Centro Cultural de Tijuana, Premio Marcchioni in Sardinia and through the Grafikwerkstatt, Dresden. She has won two Ohio Arts Council Individual Artist Awards Artist awards and, in 2021, was awarded a Mid-Career Cleveland Arts Prize. Corrie’s work has been featured at many Northeast Ohio venues including Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, The Massillon Museum, SPACES, Zygote Press and many others. Corrie teaches as part-time faculty for the Painting and Drawing Department at the Kent State University School of Art and is represented commercially by Shaheen Modern and Contemporary.

Corrie’s work can be seen in permanent public collections including The Cleveland Clinic Collection, University Hospitals Cleveland, Metro Health and Progressive Insurance. Nationally, her work has exhibited The Toledo Museum of Art, The Peoria Art Guild, Rockford Art Museum, and at her BFA Alma Mater, Parsons School of Design. Internationally her work has been exhibited at in Centro Cultural de Tijuana, Premio Marcchioni in Sardinia and through the Grafikwerkstatt, Dresden. She has won two Ohio Arts Council Individual Artist Awards Artist awards and, in 2021, was awarded a Mid-Career Cleveland Arts Prize. Corrie’s work has been featured at many Northeast Ohio venues including Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, The Massillon Museum, SPACES, Zygote Press and many others. Corrie teaches as part-time faculty for the Painting and Drawing Department at the Kent State University School of Art and is represented commercially by Shaheen Modern and Contemporary.

Christina Lindhout

Christina Lindhout is a professional dancer and choreographer based in Cleveland, Ohio, and has over 20 years of training in classical ballet, modern, jazz, and tap. She has danced professionally since she was 18 years old, and has performed many principal roles both locally and internationally. Christina performed as a Company Member with Verb Ballets from 2014 to 2020, performing with the company on several tours including to Taipei, Taiwan and Havana, Cuba. In addition to performing and choreographing, Christina directs the school at Verb Ballets Center for Dance, as well as teaches the amazing dance and theatre students at Baldwin Wallace University as an Adjunct Dance Faculty member. Christina has been a recipient of an Akron Soul Train Fellowship award for the choreography of FEAST, along with Kelly Korfhage. Most recently, she was also awarded a 2022 Individual Excellence Award for choreography from the Ohio Arts Council. IG: @christina_lindhout

She has danced professionally since she was 18 years old, and has performed many principal roles both locally and internationally. Christina performed as a Company Member with Verb Ballets from 2014 to 2020, performing with the company on several tours including to Taipei, Taiwan and Havana, Cuba. In addition to performing and choreographing, Christina directs the school at Verb Ballets Center for Dance, as well as teaches the amazing dance and theatre students at Baldwin Wallace University as an Adjunct Dance Faculty member. Christina has been a recipient of an Akron Soul Train Fellowship award for the choreography of FEAST, along with Kelly Korfhage. Most recently, she was also awarded a 2022 Individual Excellence Award for choreography from the Ohio Arts Council. IG: @christina_lindhout

Kelly Korfhage

Kelly Korfhage, a native of Cleveland, began her training at age 10 under Joanne H. Morscher and Ana Lobe. She attended summer intensives at ABT Detroit, Central Pennsylvania Youth Ballet, BalletMet, Cincinnati Ballet, and North Carolina Dance Theatre. She furthered her dance education at the University of Cincinnati-College Conservatory of Music as a Corbett Award scholarship recipient and graduated cum laude with a BFA in ballet performance. Following graduation, Kelly became a member of Kansas City Ballet’s second company, KCB2, for two seasons where she had the opportunity to perform with the company in repertoire such as Septime Webre’s Alice (In Wonderland) and Adam Hougland’s Rite of Spring. Kelly joined Verb Ballets in 2016 and has been featured in works such as Andante Sostenuto and Schubert Waltzes. Kelly appears in FEAST courtesy of Verb Ballets.

She furthered her dance education at the University of Cincinnati-College Conservatory of Music as a Corbett Award scholarship recipient and graduated cum laude with a BFA in ballet performance. Following graduation, Kelly became a member of Kansas City Ballet’s second company, KCB2, for two seasons where she had the opportunity to perform with the company in repertoire such as Septime Webre’s Alice (In Wonderland) and Adam Hougland’s Rite of Spring. Kelly joined Verb Ballets in 2016 and has been featured in works such as Andante Sostenuto and Schubert Waltzes. Kelly appears in FEAST courtesy of Verb Ballets.

Dalindyebo Shabalala

Dalindyebo Shabalala is an Associate Professor at the University of Dayton School of Law, a fellow of the UD Human Rights Center and the Hanley Sustainability Institute. He is also a fellow at the Institute for Globalization and International Regulation (IGIR) and Faculty of Law at Maastricht University, The Netherlands. His research focuses on climate change and intellectual property (IP) issues on one hand and on Traditional Knowledge and Folklore issues on the other. He has been an adviser to developing countries and civil society in negotiations at the UNFCCC, WIPO, the WTO, the Convention on Biological Diversity and in several regional and bilateral free trade agreement negotiations.

His research focuses on climate change and intellectual property (IP) issues on one hand and on Traditional Knowledge and Folklore issues on the other. He has been an adviser to developing countries and civil society in negotiations at the UNFCCC, WIPO, the WTO, the Convention on Biological Diversity and in several regional and bilateral free trade agreement negotiations.

Previously, Mr. Shabalala was Managing Attorney of CIEL’s Geneva office, and Director of CIEL’s Intellectual Property and Sustainable Development Project. He focused on issues at the intersection of intellectual property and climate change, human health, biodiversity and food security, as well as addressing systemic reform of the international intellectual property system. Mr. Shabalala was a research fellow in the Innovation, Access to Knowledge, and Intellectual Property Programme at the South Centre (2005-2006), an intergovernmental organization of developing countries in Geneva, Switzerland.

Marc Lefkowitz

Marc Lefkowitz is a sustainability consultant with over 15 years of experience as a researcher, project manager, and thought leader who has been driving community conversations in environmental policy, education, and community engagement. Lefkowitz led the GreenCityBlueLake Institute (GCBL) at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where he helped the public explore sustainability, natural history, and how to change human systems to address the existential climate crisis. Before that, Lefkowitz produced content for the GCBL web site (gcbl.org) for a decade, providing a comprehensive view of the sustainability sector in Northeast Ohio. Lefkowitz advised the City of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County on their Climate Action Plans and has served on numerous boards and advisory councils studying climate and sustainability solutions. Lefkowitz has a creative partnership with his wife, visual artist Corrie Slawson, producing the arts and culture online ‘zine Hotel Bruce from 2003 – 2004, as artists-in-residence at the TJ in China Project Space in Tijuana, Mexico, produced the novella, Borderlands, for the exhibit, The Transition and is managing content for Feast: A Ballet.

Lefkowitz led the GreenCityBlueLake Institute (GCBL) at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where he helped the public explore sustainability, natural history, and how to change human systems to address the existential climate crisis. Before that, Lefkowitz produced content for the GCBL web site (gcbl.org) for a decade, providing a comprehensive view of the sustainability sector in Northeast Ohio. Lefkowitz advised the City of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County on their Climate Action Plans and has served on numerous boards and advisory councils studying climate and sustainability solutions. Lefkowitz has a creative partnership with his wife, visual artist Corrie Slawson, producing the arts and culture online ‘zine Hotel Bruce from 2003 – 2004, as artists-in-residence at the TJ in China Project Space in Tijuana, Mexico, produced the novella, Borderlands, for the exhibit, The Transition and is managing content for Feast: A Ballet.

Natural selection in the economy. How Creative Destruction Works

The market is not compassionate, but at the same time it is open to all. Anyone can propose and implement a unique idea, but there is always a chance of failure. According to the theory of "creative destruction", such failures encourage the emergence of more powerful businesses and, in fact, move the economy forward. Let's explain how it works.

Anyone can propose and implement a unique idea, but there is always a chance of failure. According to the theory of "creative destruction", such failures encourage the emergence of more powerful businesses and, in fact, move the economy forward. Let's explain how it works.

Destroy to build

The term "creative destruction" was first used by the German economist Werner Sombart at 1913 in the book "War and Capitalism". It was popularized in 1942 by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. He believed that old technologies, industries, markets and settings must be destroyed in order to release energy that could be used for innovation.

Schumpeter viewed the economy as a dynamic process, which, unlike mathematical models, involves constant movement. In this case, equilibrium is not the goal of economic processes—entrepreneurs and workers in innovative industries will still create imbalances to find new profit opportunities. At the same time, supporters of old technologies will remain out of work.

Sounds harsh enough, but modern researchers consider creative destruction to be the main driver of economic growth. After all, in order for existing companies to stay afloat, they need to constantly develop, implement relevant technologies and increase productivity. And new businesses should initially carry innovations in order not to burn out against the background of existing participants. In such a rapidly changing pace, old technologies and ideas are quickly relegated to the background and destroyed.

The weak leave - examples of creative destruction

In recent decades, the world has experienced more than one technological leap. Here are some real examples from history.

• In 1913, Henry Ford made the first test of the assembly line: the assembly process was divided into many small operations. This technology revolutionized the assembly of automobiles and then spread to other industries. Gradually, the products were assembled in one place, this method completely lost its relevance and was no longer used.

• The 1930s saw the dawn of the telephone: people made thousands of calls a day, and at first a telephone operator connected the lines. With the development of technology, telephones have appeared in almost every apartment. However, since the beginning of the 21st century, mobile devices have come into use, which quickly replaced their outdated predecessors. On the one hand, many specialists had to look for work, on the other hand, progress accelerated, which gave impetus to the development of portable gadgets.

• Not too long ago, store shelves were full of movie cassettes and almost everyone had a VCR at home. Then the cassettes were replaced by discs: they took up less space and contained more information. Now, however, both devices are outdated and subjected to creative destruction - they have been replaced by online cinemas.

Who is next

The world does not stand still, in many areas the process of creative destruction has already begun. Let's assume what areas it can touch in the near future.

• With the development of marketplaces, more and more products can be ordered online and delivered the very next day. Moreover, they are often much cheaper than in offline stores. Perhaps in the near future, ordinary stores will completely become irrelevant, and they will be completely replaced by online platforms.

• There are more and more electric vehicles in the world, and this is logical. They are economical and do not produce harmful emissions. Already, a huge number of charging stations are being built in large cities, and the EU countries are going to get rid of gasoline and diesel cars by 2035.

• With the advent of the Internet, non-electronic media are predicted to end soon. Indeed, who needs paper newspapers or television when the news appears on the web a few seconds after it happened. Yes, as long as the "obsolete" media still exist. But it is obvious that the process of creative destruction has already begun here.

Read also: End of the era of the Great Calm. What it was and what will happen now

What it was and what will happen now

BCS Investment World

Creative destruction factor in modern models and economic growth policy | Katukov

1. V. V. Golikova, K. R. Gonchar, B. V. Kuznetsov, and A. A. Yakovlev (2007). Russian industry at a crossroads: What prevents our firms from becoming competitive. M.: Ed. HSE house.

2. Drobyshevsky S. M., Trunin P. V., Bozhechkova A. V. (2018). Long-term stagnation in the modern world // Questions of Economics. No. 11, pp. 125-141. https://doi.org/10.32609/0042-8736-2018-11-125-141

3. Zamulin O. A., Sonin K. I. (2019). Economic growth: the 2018 Nobel Prize and lessons for Russia // Questions of Economics. No. 1. S. 11-36. https://doi.org/10.32609/0042-8736-2019-1-11-36

4. Mironov V. V., Konovalova L. D. (2019). On the relationship between structural changes and economic growth in the world economy and Russia // Questions of Economics. No. 1. S. 54-78. https://doi.org/10. 32609/0042-8736-2019-1-54-78

32609/0042-8736-2019-1-54-78

5. Simachev Yu. V. et al. (2019). Structural aspects of Russia's trade policy. M.: Ed. HSE house.

6. Smorodinskaya N. V. (2017). Complication of the organization of economic systems in the conditions of non-linear development // Bulletin of the Institute of Economics of the Russian Academy of Sciences. No. 5. S. 104-115.

7. Smorodinskaya N. V., Katukov D. D. (2017). Distributed production and "smart" agenda of national economic strategies // Economic policy. T. 12, No. 6. S. 72-101.

8. Smorodinskaya N. V., Malygin V. E., Katukov D. D. (2015). How to strengthen competitiveness in the face of global challenges: a cluster approach. M.: Institute of Economics RAS.

9. TekhUspekh (2018). Current trends in the development of Russian fast-growing technology companies. Moscow: TekhUspekh.

10. Acemoglu D., Akcigit U., Alp H., Bloom N., Kerr W. (2018). Innovation, reallocation, and growth. American Economic Review, Vol. 108, no. 11, pp. 3450-3491. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130470

108, no. 11, pp. 3450-3491. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130470

11. Adler G., Duval R., Furceri D., Çelik S. K., Koloskova K., Poplawski-Ribeiro M. (2017). Gone with the headwinds: Global productivity. IMF Staff Discussion Note, No. 17/04.

12. Agénor P.-R. (2017). Caught in the middle?: The economics of middle-income traps. Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 771-791. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12175

13. Aghion P., Akcigit U., Howitt P. (2015). The Schumpeterian growth paradigm. Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 557-575. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115412

14. Aghion P., Bloom N., Blundell R., Griffith R., Howitt P. (2005). Competition and innovation: An inverted-U relationship. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 120, no. 2, pp. 701-728. https://doi.org/10.1162/0033553053970214

15. Aghion P., Howitt P. (1992). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, Vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 323-351. https://doi.org/10.2307/2951599

https://doi.org/10.2307/2951599

16. Aghion P., Howitt P. (1998). endogenous growth theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

17. Aghion P., Roulet A. (2014). Growth and the smart state. Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 913-926. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-040759

18. Ahmad N., Schreyer P. (2016). Are GDP and productivity measures up to the challenges of the digital economy? International Productivity Monitor, no. 30, pp. 4-27.

19. Aiyar S., Duval R. A., Puy D., Wu Y., Zhang L. (2013). Growth slowdowns and the middle-income trap. IMF Working Papers, 13/71.

20. Akcigit U., Alp H., Peters M. (2018). Lack of selection and limits to delegation: Firm dynamics in developing countries. NBER Working Papers, no. 21905.

21. Akcigit U., Kerr W. R. (2018). Growth through heterogeneous innovations. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 126, no. 4, pp. 1374-1443. https://doi.org/10.1086/697901

22. Alon T., Berger D. , Dent R., Pugsley B. (2018). Older and slower: The startup deficit’s lasting effects on aggregate productivity growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 93, pp. 68-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2017.10.004

, Dent R., Pugsley B. (2018). Older and slower: The startup deficit’s lasting effects on aggregate productivity growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 93, pp. 68-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2017.10.004

23. Andrews D., Criscuolo C., Gal P. N. (2015). Frontier firms, technology diffusion and public policy: Micro evidence from OECD countries. OECD Productivity Working Papers, no. 2.

24. Barro R. J., Sala-i-Martin X. (1995). economic growth. New York: McGraw-Hill.

25. Bergeaud A., Lecat R., Cette G. (2017). Total factor productivity in advanced countries: A long-term perspective. International Productivity Monitor, no. 32, pp. 6-24.

26. Bianchini S., Bottazzi G., Tamagni F. (2017). What does (not) characterize persistent corporate high-growth? Small Business Economics, Vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 633-656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9790-1

27. Bloom N., Eifert B., Mahajan A., McKenzie D., Roberts J. (2013). Does management matter? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 128, no. 1, pp. 1-51. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs044

Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 128, no. 1, pp. 1-51. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs044

28. Bloom N., Sadun R., van Reenen J. (2017). Management as a technology? NBER Working Papers, no. 22327.

29. Brandt L., van Biesebroeck J., Zhang Y. (2012). Creative accounting or creative destruction? : Firm-level productivity growth in Chinese manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 97, no. 2, pp. 339-351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.02.002

30. Brynjolfsson E., McAfee A. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. New York: Norton.

31. Byrne D. M., Fernald J. G., Reinsdorf M. B. (2016). Does the United States have a productivity slowdown or a measurement problem? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 2016, no. 1, pp. 109-182.

32. Calligaris S., Del Gatto M., Hassan F., Ottaviano G. I., Schivardi F., Monacelli T. (2018). The productivity puzzle and misallocation: An Italian perspective. Economic Policy, Vol. 33, no. 96, pp. 635-684. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiy014

Economic Policy, Vol. 33, no. 96, pp. 635-684. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiy014

33. Cowen T. (2011). The great stagnation. New York: Duton.

34. Crespo Rodríguez A., Pérez-Quirus G., Segura Cayuela R. (2012). Competitiveness indicators: The importance of an efficient allocation of resources. Banco de España Economic Bulletin, Vol. January, pp. 103-111.

35. Decker R. A., Haltiwanger J., Jarmin R. S., Miranda J. (2017). Declining dynamism, allocative efficiency, and the productivity slowdown. American Economic Review, Vol. 107, no. 5, pp. 322-326. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171020

36. Easterly W., Levine R. (2001). It's not factor accumulation: Stylized facts and growth models. The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 177-219. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/15.2.177

37. EBRD (2017). Transition report 2017-18: Sustaining growth. London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

38. Eichengreen B., Park D., Shin K. (2012). When fast-growing economies slow down: International evidence and implications for China. Asian Economic Papers, Vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 42-87. https://doi.org/10.1162/ASEP_a_00118

(2012). When fast-growing economies slow down: International evidence and implications for China. Asian Economic Papers, Vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 42-87. https://doi.org/10.1162/ASEP_a_00118

39. European Commission (2017). Economic challenges of lagging regions. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

40. Felipe J., Abdon A., Kumar U. (2012). Tracking the middle-income trap: What is it, who is in it, and why? Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Working Paper, no. 715.

41. Garicano L., Lelarge C., van Reenen J. (2016). Firm size distortions and the productivity distribution: Evidence from France. American Economic Review, Vol. 106, no. 11, pp. 3439-3479. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130232

42. Gordon R. J. (2016). The rise and fall of American growth: The U.S. standard of living since the Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

43. Grifell-TatjéE., Lovell C. A. K., Sickles R. C. (2018). Overview of productivity analysis: History, issues, and perspectives. In: E. Grifell-Tatjé, C. A. K. Lovell, R. C. Sickles (eds.). The Oxford handbook of productivity analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3-73.

In: E. Grifell-Tatjé, C. A. K. Lovell, R. C. Sickles (eds.). The Oxford handbook of productivity analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3-73.

44. Grossman G. M., Helpman E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

45. Grover Goswami A., Medvedev D., Olafsen E. (2018). High-growth firms: Facts, fiction, and policy options for emerging economies. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

46. Gurvich E. (2016). Institutional constraints and economic development. Russian Journal of Economics, Vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 349-374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ruje.2016.11.002

47. Hsieh C.-T., Klenow P. J. (2009). Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 124, no. 4, pp. 1403-1448. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.4.1403

48. Iwasaki I., Maurel M., Meunier B. (2016). Firm entry and exit during a crisis period: Evidence from Russian regions. Russian Journal of Economics, Vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 162-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ruje.2016.06.005

2, no. 2, pp. 162-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ruje.2016.06.005

49. Kuznetsov Y., Sabel C. (2011). New open economy industrial policy: Making choices without picking winners. PREM Notes, no. 161.

50. Lardy N. R. (2019). The state strikes back: The end of economic reform in China? Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

51. McGahan A. M., Porter M. E. (1999). The persistence of shocks to profitability. Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 81, no. 1, pp. 143-153. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465399767923890

52. Melitz M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, Vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 1695-1725. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00467

53. Mokyr J. (2018). The past and the future of innovation: Some lessons from economic history. Explorations in Economic History, Vol. 69, pp. 13-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2018.03.003

54. Moschella D. , Tamagni F., Yu X. (2019). Persistent high-growth firms in China's manufacturing. Small Business Economics, Vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 573-594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9973-4

, Tamagni F., Yu X. (2019). Persistent high-growth firms in China's manufacturing. Small Business Economics, Vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 573-594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9973-4

55. OECD (2014). Industry and technology policies in Korea. Paris: OECD Publishing.

56. OECD (2015). The future of productivity. Paris: OECD Publishing.

57. OECD (2017a). Debate the issues: Complexity and policy making. Paris: OECD Publishing.

58. OECD (2017b). The next production revolution: Implications for governments and business. Paris: OECD Publishing.

59. Park B.-G., Hill R. C., Saito A. (eds.) (2012). Locating neoliberalism in East Asia: Neoliberalizing spaces in developmental states. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

60. Porter M. E., Delgado M., Ketels C. H., Stern S. (2008). Moving to a new global competitiveness index. In: K. Schwab, M. E. Porter (eds.). The global competitiveness report 2008—2009. Geneva: World Economic Forum, pp. 43-63.

61. Romer P. M. (1990). endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, no. 5, Part 2, S71-S102. https://doi.org/10.1086/261725

Romer P. M. (1990). endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, no. 5, Part 2, S71-S102. https://doi.org/10.1086/261725

62. Russell M. G., Smorodinskaya N. V. (2018). Leveraging complexity for ecosystemic innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 136, pp. 114-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.11.024

63. Schumpeter J. A. (1942). capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York: Harper & Brothers.

64. Smorodinskaya N. V., Russell M. G., Katukov D. D., Still K. (2017). Innovation ecosystems vs. innovation systems in terms of collaboration and co-creation of value. Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/41798

65. Solow R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 65-94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884513

66. Summers L. H. (2015). Demand side secular stagnation.

-Step-18.jpg/aid1640374-v4-728px-Shuffle-(Dance-Move)-Step-18.jpg)