How did the ghost dance lead to a tragic conflict

The Lakota Ghost Dance and the Massacre at Wounded Knee | American Experience | Official Site

From the Collection: Native Americans

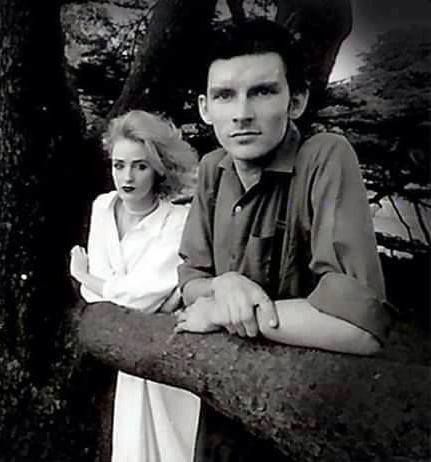

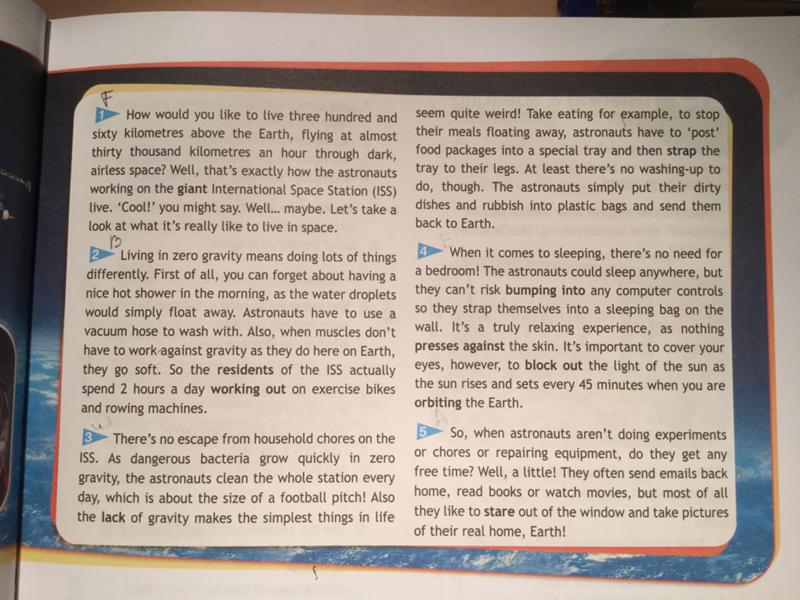

Native Americans performing ritual Ghost Dance. One standing woman is wearing a white dress, a special costume for the ritual dance, 1890. Photo by James Mooney, an ethnologist with US Dept. of Interior. AlamyEditor’s note: When L. Frank Baum and other white settlers arrived in Aberdeen, South Dakota in the 1880s, they were entering land that had been part of the homeland of the Western Sioux or Lakota. On the Standing Rock and Pine Ridge reservations west of Aberdeen, conditions were dire for the over 10,000 Lakota living there. In the following excerpt from God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America, Louis S. Warren recounts the Lakota struggle to resist assimilation and survive in the face of violent suppression from the administration of President Benjamin Harrison.

In the west, drought had baked the earth bare. Indian reservations occupied poor land that had little game and few wild plants of any use. In the withering heat, what grass was left by cattle and sheep (most of them owned by white ranchers) quickly shriveled. Scarce game vanished. By 1885, many Indians had turned their hand to farming, but in 1890 their crops wilted. Starvation, that old monster, circled the camps.

It was thus not surprising that some Indians had turned to a new faith. In doing so, Indian believers unwittingly launched upon a collision course with the anxious American public. What swept the West that summer was an evangelical revival that synthesized ancient Indian beliefs with new millenarian teaching. Strange stories made their way from neighbor to neighbor, from one people to the next, stories of distant laughter on the breeze, dead loved ones brought back to life, and an earth again made green and bountiful.

Bison hunting had ceased by the early 1880s, for the animals were nearly extinct. The only survivors of the great herds were living in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, on a few private ranches far to the south or in Canada, and in zoos and traveling Wild West shows. But in 1890, in the midst of the drought, a few of the shaggy beasts appeared suddenly on one of the Sioux reservations in South Dakota. Had the spirits returned their favor? How else could one explain this miraculous event?

The only survivors of the great herds were living in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, on a few private ranches far to the south or in Canada, and in zoos and traveling Wild West shows. But in 1890, in the midst of the drought, a few of the shaggy beasts appeared suddenly on one of the Sioux reservations in South Dakota. Had the spirits returned their favor? How else could one explain this miraculous event?

Stories like these spread among friends and acquaintances, raising unanswerable questions and inspiring new faith. And all that fall, Indians danced. They danced from the deep Southwest to the Canadian border and into Alberta. They danced from the Sierra Nevada to eastern Oklahoma. They danced in southern Utah, and in Idaho. They danced in Arizona.

In Nevada, a thousand Shoshones danced all night, and as the eastern sky turned pale shouts rang out that the spirits of deceased loved ones were appearing among the faithful. A thousand voices shouted in unison, “Christ has come!,” and they fell to the ground, or perhaps to their knees, weeping and singing and utterly exhausted. Although many had dismissed the springtime talk of a messiah somewhere in the mountains of western Montana, the rumor seemed only to grow over time. From the Southwest to the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming and on into the plains of South Dakota, Indians spoke of a redeemer to the north.

Although many had dismissed the springtime talk of a messiah somewhere in the mountains of western Montana, the rumor seemed only to grow over time. From the Southwest to the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming and on into the plains of South Dakota, Indians spoke of a redeemer to the north.

By the fall of 1890, authorities who read the telegrams and heard the reports had become uneasy. Thirty Indian reservations were transfixed by the prophecies of the Messiah, but the teachings had a particularly enthusiastic following among the Lakota Sioux, also known as the Western Sioux. Because of the relatively recent history of US hostilities with these people—the notorious Sitting Bull was learning the new faith—it was there that government agents soon focused their attentions.

It is almost impossible to overstate how vehement officials and other Americans eventually became over the need to break up the dances. Of all the features of the new ritual that garnered commentary, the physical excitement of the dancers received the most attention. The central feature of the Ghost Dance everywhere was a ring of people holding hands and turning in a clockwise direction—“men, women, and children; the strong and the robust, the weak consumptive, and those near to death’s door,” as one observer described them. Lakotas had grafted onto the Ghost Dance some symbols of their primary religious ritual, the Sun Dance. Thus, Sioux believers felled a tree, often a young cottonwood, and re-erected it at the center of their dance circle. On it they hung offerings to the spirits, including colored ribbons and sometimes an American flag. Near the tree stood the holy men, supervising the event and assembling the believers, who began by taking a seat in the circle around the tree. There was a prayer, and sometimes a sacred potion was passed for participants to drink. Then dancers might together utter “a sort of plaintive cry, which is pretty well calculated to arrest the ear of the sympathetic.

Of all the features of the new ritual that garnered commentary, the physical excitement of the dancers received the most attention. The central feature of the Ghost Dance everywhere was a ring of people holding hands and turning in a clockwise direction—“men, women, and children; the strong and the robust, the weak consumptive, and those near to death’s door,” as one observer described them. Lakotas had grafted onto the Ghost Dance some symbols of their primary religious ritual, the Sun Dance. Thus, Sioux believers felled a tree, often a young cottonwood, and re-erected it at the center of their dance circle. On it they hung offerings to the spirits, including colored ribbons and sometimes an American flag. Near the tree stood the holy men, supervising the event and assembling the believers, who began by taking a seat in the circle around the tree. There was a prayer, and sometimes a sacred potion was passed for participants to drink. Then dancers might together utter “a sort of plaintive cry, which is pretty well calculated to arrest the ear of the sympathetic.![]() ” Once these preliminaries were completed, the dancers rose and started singing—unaccompanied, without drums or other instruments—and the circle began to turn.

” Once these preliminaries were completed, the dancers rose and started singing—unaccompanied, without drums or other instruments—and the circle began to turn.

Astonished and disturbed by the enthusiasms of the ritual, some American witnesses were moved to dire warnings. One agent reported that the Indians favored “disobedience to all orders, and war if necessary to carry out their dance craze.” “The Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy,” hyperventilated the agent at Pine Ridge. Another denounced the actual dance as “exceedingly prejudicial” to the “physical welfare” of the Indians, who became exhausted by it. “I think, “the agent went on, “steps should be taken to stop it.” Fearful that unconscious women might be molested, one white witness at Pine Ridge claimed that women “fall senseless to the ground, throwing their clothes over their heads, and laying bare the most prominent part of their bodies, viz., ‘their butts’ and ‘things.’” Concluded still another, “The dance is indecent, demoralizing, and disgusting. ”

”

For these observers, the dance was a physical manifestation of irrationality, a refusal to be governed in body or in spirit by the codes of Victorian decorum handed down from missionaries. In one sense, at least, this view was substantially correct. For the Lakota and for other Indians, however, the Ghost Dance was both strikingly new—even radical—and reassuringly familiar. Ghost Dancers were searching for a new dispensation, seeking to restore an intimacy with the Creator that seemed to have vanished. And for followers, the religion’s key attractions included the chance to worship in a form that reconstituted Indians as a community and expressed their history, families, and identity—in a word, their Indianness. The Ghost Dance invited believers, as one Sioux evangelist put it, to “be Indians” again.

The real "messiah craze" of 1890 was the fixation of Americans on Indian dancing and their relentless compulsion to stop it, and the root of that craze was this American passion for assimilation, which was, after all, every bit as millennial a notion as the Second Coming itself. What more utopian a dream could there be for a rapidly globalizing society riven by fractures of race, culture and class than that a day would come when differences between people had simply disappeared? So it was that, in a show of hostility to physical exaltation reminiscent of the Puritans, policymakers waged war on Indian dances. In 1882 US Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller issued new orders to suppress “heathenish dances, such as the sun dance, scalp dance, &c.,” in order to bring Indians into line with conventional Christian practice.

What more utopian a dream could there be for a rapidly globalizing society riven by fractures of race, culture and class than that a day would come when differences between people had simply disappeared? So it was that, in a show of hostility to physical exaltation reminiscent of the Puritans, policymakers waged war on Indian dances. In 1882 US Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller issued new orders to suppress “heathenish dances, such as the sun dance, scalp dance, &c.,” in order to bring Indians into line with conventional Christian practice.

The situation was all the more frustrating because it should have been easy. Indians had practically no power. They held no citizenship and remained federal subjects unable to vote. With no political representatives, they depended on appointed officials—reservation supervisors known as “Indian agents”—for their very survival. Dawes and others believed that education, example, and compulsion could turn Indians into good citizens. If Congress would mandate (and Indians agents would follow) a stern policy of assimilation, surely it would “kill the Indian and save the man,” as one prominent assimilationist put it. Thus would Indians enter the fold of the civilized, pointing the way for millions of immigrants and African Americans and preparing the ground for that glorious day when all dark skins would somehow whiten and racial strife would vanish.

If Congress would mandate (and Indians agents would follow) a stern policy of assimilation, surely it would “kill the Indian and save the man,” as one prominent assimilationist put it. Thus would Indians enter the fold of the civilized, pointing the way for millions of immigrants and African Americans and preparing the ground for that glorious day when all dark skins would somehow whiten and racial strife would vanish.

For Americans, then, the challenge of assimilation was the great social question whirling at the center of the Ghost Dance of 1890. A millennial enthusiasm for assimilating others, as well as a deep anxiety that they might refuse to be assimilated, explains much of what made the Ghost Dance so troubling. To most white Americans, the dance itself was proof that assimilation had failed to dampen the savage impulse and that America’s irresistible conquest might prove resistible after all. In this light, the dances in South Dakota were more than just dances, and more than another Indian uprising. For Americans, something more, much more, was on the line.

In this light, the dances in South Dakota were more than just dances, and more than another Indian uprising. For Americans, something more, much more, was on the line.

Still, well into the fall of 1890, Ghost dances were nothing more than a curiosity, titillating fare for newspaper readers in distant cities. Although the dances had increased in intensity early in the fall, officials on the scene were mostly unconcerned. As late as the first week of November, only one Indian agent in South Dakota had requested military intervention; the others believed that the dance would die out of its own accord. Most local newspapers carried little to no news of the Ghost Dance.

But on November 13, President Harrison ordered the army into the Sioux reservations to shore up beleaguered officials and prevent “any outbreak that may put in peril the lives and homes of the settlers of the adjacent states.” With one-third of the entire US Army descending on some of the most remote and impoverished communities in the United States, the “Ghost Dance War” quickly became the largest military campaign since Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

The arrival of columns of soldiers panicked the Indians and, in conjuring the possibility of war, terrified many settlers, who until that moment had not felt threatened. After treating the Ghost Dance mostly as a curiosity, the press now sank to new lows, riveting a considerable portion of the nation’s 63 million people with stories about imminent “outbreaks” by bloodthirsty savages—never mind that fewer than a quarter of a million Indians remained in the United States, and only 18,000 of these were Lakota Sioux. Never mind that there were only about 4,200 Ghost Dancers, and that most of them were children, their mothers, and the very old. The New York Times quoted estimates of 15,000 “fighting Sioux,” and others picked up rumors of an impending Sioux “outbreak.” Some even reported that thousands of armed Indians had surrounded the reservation and killed settlers and soldiers.

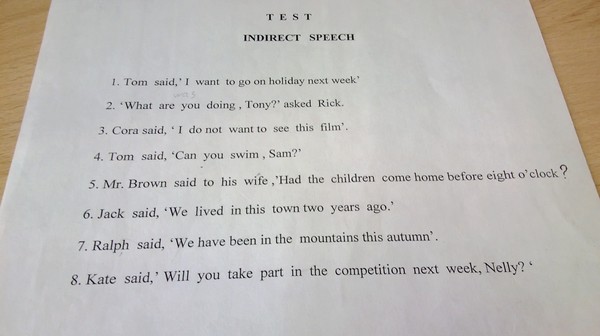

Sitting Bull by D F Barry, 1883 Dakota Territory, Public DomainIn mid-December, James McLaughlin, the agent at Standing Rock Reservation (some 275 miles north of Wounded Knee), sent the Indian police to arrest Sitting Bull, the most renowned Lakota chief still living. McLaughlin had long harbored a personal grudge against Sitting Bull. Now, since Sitting Bull had allowed Ghost Dances to take place at his camp, McLaughlin hoped to exploit the Ghost Dance tumult to have him removed from the reservation. When the detachment arrived at Sitting Bull’s home at dawn on December 15 and took him into custody, however, some of Sitting Bull’s enraged followers opened fire, and in the conflagration that followed the police shot the famed chief in the head and chest. The killing of Sitting Bull sent waves of panic and fear across the reservation, and when Lakota Indians there and at other reservations heard the news, they began to crisscross the countryside looking for refuge from the troops.

McLaughlin had long harbored a personal grudge against Sitting Bull. Now, since Sitting Bull had allowed Ghost Dances to take place at his camp, McLaughlin hoped to exploit the Ghost Dance tumult to have him removed from the reservation. When the detachment arrived at Sitting Bull’s home at dawn on December 15 and took him into custody, however, some of Sitting Bull’s enraged followers opened fire, and in the conflagration that followed the police shot the famed chief in the head and chest. The killing of Sitting Bull sent waves of panic and fear across the reservation, and when Lakota Indians there and at other reservations heard the news, they began to crisscross the countryside looking for refuge from the troops.

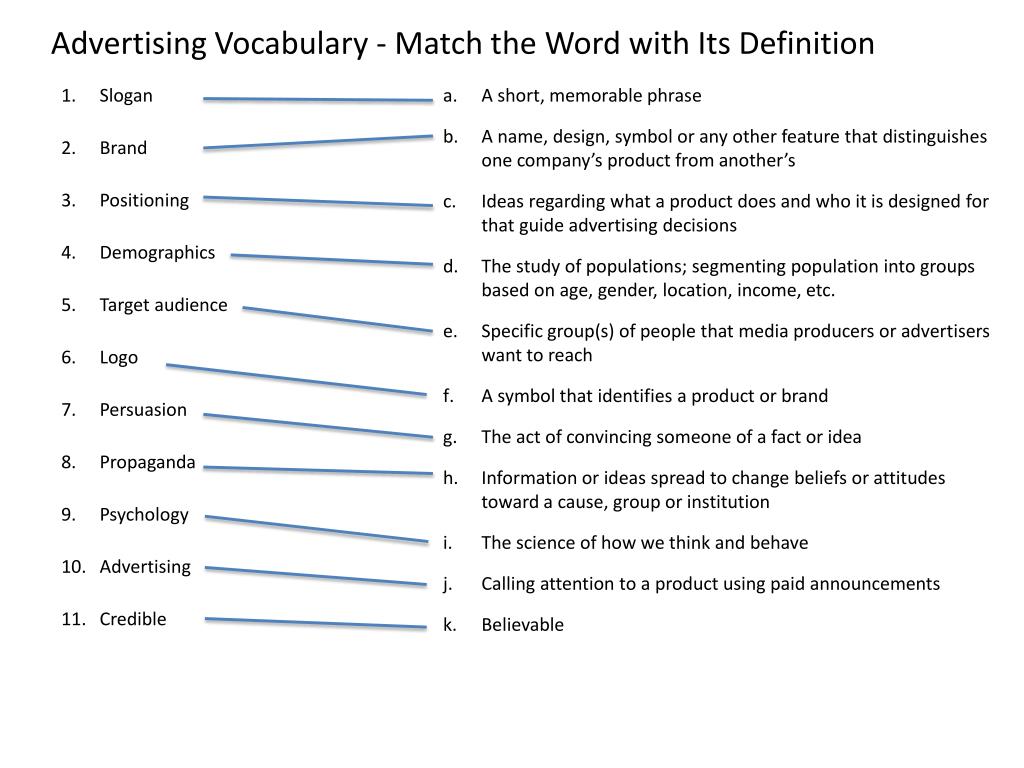

So it was that on December 28 a starving band of Ghost Dancers who had fled their homes on Cheyenne River Reservation surrendered to Colonel James Forsyth’s Seventh Cavalry at Wounded Knee Creek. The next morning troops upended Sioux lodges in a hunt for weapons. Two soldiers were attempting to seize a weapon from a Lakota man when it discharged. No one was hurt, but it did not matter. The ranks of soldiers opened fire. With four rapid-fire Hotchkiss guns on the edges of the ravine, Custer’s old regiment loosed an exploding shell nearly every second from each of the big guns—and a fusillade of rifle and pistol fire besides—into the mass of mostly unarmed villagers below. Indian men who were not instantly cut down did their best to fend off the troops with a few guns, some knives, rocks, and their bare hands as the ranks of women, children and old people fled up the creek.

Two soldiers were attempting to seize a weapon from a Lakota man when it discharged. No one was hurt, but it did not matter. The ranks of soldiers opened fire. With four rapid-fire Hotchkiss guns on the edges of the ravine, Custer’s old regiment loosed an exploding shell nearly every second from each of the big guns—and a fusillade of rifle and pistol fire besides—into the mass of mostly unarmed villagers below. Indian men who were not instantly cut down did their best to fend off the troops with a few guns, some knives, rocks, and their bare hands as the ranks of women, children and old people fled up the creek.

Among the Sioux men at Wounded Knee were a handful of the continent’s most experienced close-range fighters, and when the conflict was over, the army did not emerge unscathed. The Seventh left the field with dozens of wounded, and thirty troopers died. The army took thirty-eight wounded Indians with them but left the Indian dead and more of their wounded to the mercy of the Dakota sky. As night fell, winter descended in all its high-country fury. Temperatures dropped far below freezing, and a fierce blizzard howled in from the north. Corpses turned to ice. When soldiers and a burial party returned three days later, they found several wounded Lakotas yet clinging to life and some surviving infants in the arms of their dead mothers. All but one of these babies and most of the others soon succumbed.

As night fell, winter descended in all its high-country fury. Temperatures dropped far below freezing, and a fierce blizzard howled in from the north. Corpses turned to ice. When soldiers and a burial party returned three days later, they found several wounded Lakotas yet clinging to life and some surviving infants in the arms of their dead mothers. All but one of these babies and most of the others soon succumbed.

Soldiers heaped wagons with the Indian dead, who looked eerily like the haunting plaster casts of the Pompeii victims of Mount Vesuvius, some having frozen in the grotesque positions in which they had hit the ground. Others were curled up or horribly twisted, their hands clawing at the air and mouths agape, each a memorial to the agony of open wounds, smothering cold and the relentless triumph of death. A photographer arrived to take pictures (which immediately became a popular line of postcards).

Big Foot's camp three weeks after the Wounded Knee Massacre with bodies of several Lakota Sioux people wrapped in blankets in the foreground and U. S. soldiers in the background, Dec. 29, 1890. Library of Congress

S. soldiers in the background, Dec. 29, 1890. Library of CongressThe gravediggers lowered the bodies of 84 men, 44 women and 18 children into the ground. More had died, but many had been taken by kin or managed to leave the field before dying, perhaps in another camp, or alone on the darkling plain. We can look at old photographs, read crumpled letters and scan columns of crumbling newspaper, but death is final and pitiless, and its tracks soon vanish. We cannot account for all who were killed at Wounded Knee.

Religion is an affair of the heart, but it offers relief and guidance for people living in a hard-edged world. Indians became Ghost Dancers partly in response to changing material conditions that had created an existential crisis. Much of the religion’s allure came from how it addressed a radically shifting material world and helped Indians cope with the Industrial Revolution and its accompanying juggernaut of modernity, the rise of corporate structures to economic dominance in the United States, and the expanding bureaucracy of the state and modern education. The Ghost Dance served the needs of Indians hoping to adjust to life under industrial capitalism in a nation where literacy was key to negotiating courtrooms and the government offices that administered so much of Indian life.

The Ghost Dance served the needs of Indians hoping to adjust to life under industrial capitalism in a nation where literacy was key to negotiating courtrooms and the government offices that administered so much of Indian life.

In other words, in the aftermath of American invasion, the Ghost Dance helped believers find ways to negotiate and assert new dimensions of control not only over their own spiritual lives but also over their governance. In this sense, the massacre at Wounded Knee marks a brutal suppression not of naive, primitive Indians but of pragmatic people who sought a peaceful way forward into the twentieth century.

It is testament to its modernity that the religion was not so easily killed. The promise of the Ghost Dance was so great that Indian people carried on its devotions long after Wounded Knee. It survived on the Southern Plains and in Canada well into the twentieth century. In many places, it made lasting contributions to Indian ritual, some of which survive to the present day.

Louis S. Warren

Louis S. Warren is W. Turrentine Jackson Professor of Western U.S. History at the University of California, Davis, where he teaches the history of the American West, California history, environmental history, and U.S. history. His most recent book, God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America. His other books include The Hunter’s Game: Poachers and Conservationists in Twentieth-Century America and Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show.

Excerpted from God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America by Louis S. Warren. Copyright © 2017. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

James Mooney Recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs, 1894

The Ghost Dance among the Oglala Lakota as depicted by Frederic Remington from sketches made at the event, Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 1890. Printed in Harper’s Weekly, December 1890. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3a07191

Printed in Harper’s Weekly, December 1890. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3a07191

In the summer of 1894 James Mooney, a scholar of American Indian culture and language, made recordings of songs of the Ghost Dance in several languages. The James Money Recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs have recently been updated and are part of the presentation, Emile Berliner and the Birth of the Recording Industry. It is likely that these recordings were sung by Mooney himself. This was not unusual, as the common practice of the time was for ethnographers to memorize songs and stories from the people they studied, performing them back to the people helping them to learn the songs so that they had as accurate a performance as possible. In this way human memory was the “recording” before actual recording technology was widely available. Even today ethnographers often learn to reproduce songs and stories from the cultures they study as part of participant/observation and because much can be learned by memorizing and repeating them.

This recording is an example of a Caddo Ghost Dance song. The Caddo Nation is a confederation of several Southeastern Indian peoples who at this time lived on a reservation in Oklahoma:

The Ghost Dance was a spiritual movement that arose among Western American Indians. It began among the Paiute in about 1869 with a series of visions of an elder, Wodziwob. These visions foresaw renewal of the Earth and help for the Paiute peoples as promised by their ancestors. This followed a period when many people had died as a result of contact with European diseases. A typhoid epidemic in 1867 may also have influenced the birth of this movement. Initially Wodziwob said that he saw some great cataclysm removing all the Europeans leaving behind only Indians, but in later visions he saw an event that removed all people from the continent, after which those who faithfully practiced the spirituality of their ancestors would be miraculously returned. Later still, his vision no longer predicted the destruction of Europeans, but an immortal and peaceful life for those who practiced his spiritual teachings. A ceremony that featured a communal circle dance was central to the spiritual practice suggested by these visions. Wodziwob passed away in 1872.

A ceremony that featured a communal circle dance was central to the spiritual practice suggested by these visions. Wodziwob passed away in 1872.

On January 1, 1889, a Northern Paiute named Wovoka (born Quoitze Owalso, he also took the name Jack Wilson) had a dream during the eclipse of the sun. His prophesy was similar to that of Wodziwob. He said that he saw the European settlers leaving or disappearing, the buffalo returning, and the land restored to Indian peoples all across the continent. In this vision, ancestors would be brought back to life and all would live in peace. Wovoka had been raised by the European American family of David Wilson after the death of his father. His teachings emphasized maintaining a peaceful relationship with white Americans. He had had some exposure to Christianity and so it is not surprising that there are mentions of Jesus or a messiah in his teachings. He said that by practicing the circle dance ceremony his vision of a peaceful world would be made to come about.

Hearing of the new prophet among the Paiute, representatives from many different tribes traveled to speak with him. Letters were sent by leaders of the movement to other Indian peoples to explain the vision and the ceremony that would help bring about the transformation of the Earth. Leaders of the movement also visited various Indian nations to help teach them about the vision and the dance.

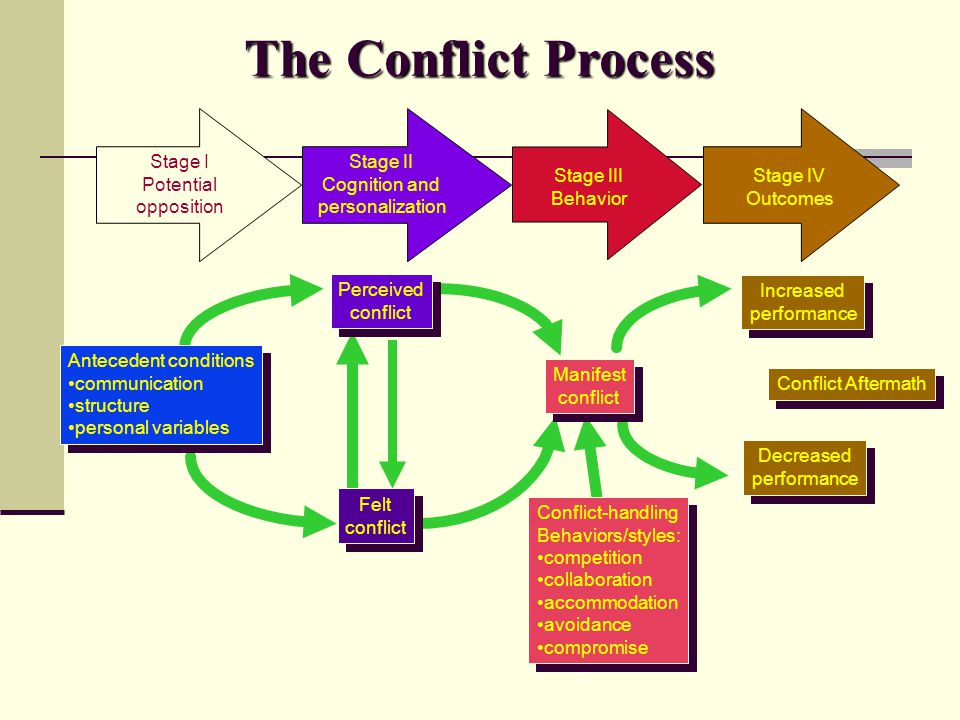

“Ghost dance – Cheyennes & Arapahoes.” Detail of a photo taken at the Indian Congress of the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska, by Adolf F. Muhr, ca 1898. The Ghost Dance was often performed around a pole, and in this case the dancers chose to use the American Flag. //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c25485

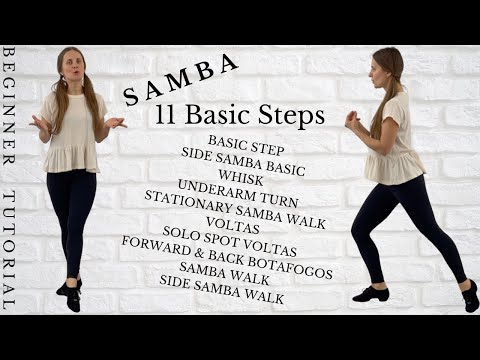

Dancing is common among many Indian spiritual practices. The Ghost Dance was based on the round dance that is common to many Indian peoples, used as a social dance as well as for healing practices. Participants hold hands and dance around in a circle with a shuffling side to side step, swaying to the rhythm of the songs they sing. In a traditional round dance there is a drum played in the center of the circle. But the Ghost Dance ceremony did not typically use a drum. Instead there was often a pole or a tree in the center of the circle, or sometimes nothing at all. The details of the dance varied somewhat among the peoples who performed it.

In a traditional round dance there is a drum played in the center of the circle. But the Ghost Dance ceremony did not typically use a drum. Instead there was often a pole or a tree in the center of the circle, or sometimes nothing at all. The details of the dance varied somewhat among the peoples who performed it.

According to Mooney, the dance induced an hypnotic state in some dancers, with some making an effort to achieve a trance. To help this process, someone would stand in the circle waving a feather or a cloth for dancers to watch. Songs with a faster rhythm were sung to help the dancers wishing to achieve a trance and perhaps experience visions. Those experiencing a trance might leave the circle of dancers and dance on their own or lie on the ground.[1] In the print by Frederic Remington at the top of this article, the circle of dancers are in the background. In the foreground are people who have dropped out of the dancing as Mooney described.

The Ghost Dance songs had a common pattern of a line repeated twice, then another line repeated twice, and so on. According to Judith Gray, the American Folklife Center’s expert on American Indian music and song, this pattern was common among the Paiute and other peoples of the Northwest Plateau, but was not used among the Plains Indians or many of the other peoples who took up the Ghost Dance. But the people adopted this song form that was new to them and used it as they made Ghost Dance songs in their own languages.

According to Judith Gray, the American Folklife Center’s expert on American Indian music and song, this pattern was common among the Paiute and other peoples of the Northwest Plateau, but was not used among the Plains Indians or many of the other peoples who took up the Ghost Dance. But the people adopted this song form that was new to them and used it as they made Ghost Dance songs in their own languages.

This recording is of two Arapaho Ghost Dance Songs. The first is a slower song than the second:

The Ghost Dance ceremony to spread rapidly to many different Indian peoples, mainly in Western states. This interaction between Indians distant from each other and the spread of the dance became alarming to European Americans and so became a concern for the United States Army.

While many European Americans were alarmed by the Ghost Dance and saw it as a militant and warlike movement, it was quite the opposite — an emergence of a peaceful resistance movement based on Indian beliefs. It was also a movement of desperation, as existing treaties had been violated and Indians in the West were forced onto reservations. For the Plains Indians, this was a period of starvation as the buffalo were slaughtered, destroying their way of life and main source of food. From an Indian point of view, Europeans were not only destroying the way of life of Indian peoples, but destroying the natural resources of the plains to an extent that would make it impossible for anyone to live there. European Americans often saw the Ghost Dance as irrational. From an Indian point of view, what was being done to them and their way of life was irrational.

It was also a movement of desperation, as existing treaties had been violated and Indians in the West were forced onto reservations. For the Plains Indians, this was a period of starvation as the buffalo were slaughtered, destroying their way of life and main source of food. From an Indian point of view, Europeans were not only destroying the way of life of Indian peoples, but destroying the natural resources of the plains to an extent that would make it impossible for anyone to live there. European Americans often saw the Ghost Dance as irrational. From an Indian point of view, what was being done to them and their way of life was irrational.

James Mooney wrote a book about the Ghost Dance, hoping it would help to counter newspaper articles about it that were inaccurate and promoted prejudice toward the Indians. His research was first published as part of a report in 1890, then enlarged as a book in 1896. The press encouraged popular belief that the dance was dangerous and possibly a prelude to an Indian uprising. Mooney emphatically explained that it was peaceful. In his introduction he describes several fieldwork trips between 1890-1894 that “occupied twenty-two months, involving nearly 32,000 miles of travel, and more or less time spent with about twenty tribes.” [2] As a participant/observer he sang and danced with the Arapaho and Cheyenne, consulted with participants in the new religion, and also took photographs. One reason for the excitement about the Ghost Dance among ethnographers at that time was that the researchers of American Indians were seeing the emergence of a new religion developing in a surprisingly short time and crossing culture and language barriers. This was an extremely rare event.

Mooney traced the beliefs of the Ghost Dance movement to earlier spiritual prophesies among many Indian groups that predicted a restoration of their land and the return of life as it was lived before Europeans settled the Americas. These emerged not long after the first settlements were established and conflicts between Europeans and Indians began. [3] So although the Ghost Dance seemed to emerge suddenly, the ideas found in it had a long history among many different Indian groups.

The body of Spotted Elk, chief of the Miniconjou, Lakota Sioux, lying in snow, after the Massacre at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, December 29, 1890. Written on the photo is “Big Foot, chief of the Bules [sic] taken at the Battle of Wounded Knee, S.D.” Published by Trager and Kuhn c 1891. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c16812

The Ghost Dance was associated with one of the great tragedies of American history. In December 15, 1890, during a dispute about a Ghost Dance ceremony, police killed Chief Sitting Bull at Standing Rock Reservation, South Dakota. After this, a group of over 300 Miniconjou Lakota men, women, and children led by Chief Spotted Elk (also called Big Foot) left the Standing Rock Reservation to try and reach the relative safety of the Pine Ridge Reservation. They were detained by United States Army at a creek called Wounded Knee and held at gunpoint, including Hotchkiss guns, an early type of machine gun. The men were separated from the women and children and as the soldiers confiscated weapons from the men, something happened and shooting began. According to some accounts one man, who may have been deaf, refused to give up his rifle. The number of dead is among many things about this incident that are disputed, but between 150 and 300 Indians were killed, many of them unarmed women and children. The larger figures given by historians include those died of exposure and their wounds after the battle, including small children whose mothers had been killed. Spotted Elk, who was unarmed and suffering from pneumonia, was shot as he lay on the ground. The Army lost 25 men.

Mooney gives a detailed account of the events leading up to the conflict, the conflict, and its aftermath. He includes first-hand accounts of the conflict and accounts from Indians who went to the site of the conflict shortly after to look for survivors. He attributes the differing figures on the number of people who died in a failure to account for the people who did not die at once in the battle. He estimates that about 300 people were killed, died later of their wounds, or died of exposure.[4]

He attributes the differing figures on the number of people who died in a failure to account for the people who did not die at once in the battle. He estimates that about 300 people were killed, died later of their wounds, or died of exposure.[4]

In atmosphere of the fear of the Ghost Dance of these times, this event was called a battle, the soldiers were called heroes, and they received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Today the incident is called the Wounded Knee Massacre. The change of view came about in 1971 with the publication of the history Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West by Dee Brown and the rise of the Indian civil rights movement. At last the Indian side of history was being told. I remember this moment because I was just finishing high school and I was upset by the way my history books and history teachers portrayed American Indians. I had already read Vine Deloria’s Custer Died for your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. My mother had bought and read Dee Brown’s new book and she gave it to me saying only “Here, you need to read this.”

My mother had bought and read Dee Brown’s new book and she gave it to me saying only “Here, you need to read this.”

It was two years after the terrible events at Wounded Knee that Mooney first published his research. He intended to calm fears that might lead to further violence. He did newspaper interviews and became the leading expert on the Ghost Dance. His recordings of Ghost Dance songs were also an attempt to preserve something about the reality of the Ghost Dance. But in the popular ideas of the time, the Ghost Dance was a threat to America that ended 1890 in the snow in South Dakota during that massacre. Some histories of these events still say so. The Bureau of Indian Affairs attempted to ban the Ghost Dance, also contributing to the idea that it had ended. But in fact the Ghost Dance ceremony continued to be performed into the early 20th century and some of the songs are preserved in the traditions of Indians today. Examples of Ghost Dance songs sung by Indians in various languages can be found in the collections of the American Folklife Center (available on site only). Researchers in our archive and others should know that some collectors described these as “new religion songs” rather than Ghost Dance songs.

Researchers in our archive and others should know that some collectors described these as “new religion songs” rather than Ghost Dance songs.

In 1973 a protest by the Lakota Sioux took place at Wounded Knee as part of the Indian rights movement, showing the importance that the events there continue to hold for Native Americans. I think some aspects of the ideas in Ghost Dance spirituality exist in Indian rights expressions even today — the idea of peaceful resistance to prejudice and oppression, for example. Listen to the recordings, and see what you think.

Notes

- Mooney, James. “The Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890.” Published in the Fourteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1892-93, Part 2, pp. 922 -926. Available online. Other editions available.

- Mooney, James. “The Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890,” p. 654. Available online. Other editions available.

- Mooney, James.

“The Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890,” pp. 657-706. Available online. Other editions available.

“The Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890,” pp. 657-706. Available online. Other editions available. - Mooney, James. “The Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890,” pp. 824-894. Available online. Other editions available.

Plots - Targaryen and Blackfire Conflict | Page 48

Anonymous-san wrote:

The Greyjoys, as I understand it, were betrayed after Damon's death.

Click to expand...

Thorvin clearly ruled after Dagon Greyjoy. Thorvin betrayed Ægor Rivers and it seems that this happened during the Third Blackfire Rebellion when Ægor was captured:

A complete chronicle of their reign can be found in Archmaester Heireg's History of the Ironborn. You will also read about Dagon Greyjoy, the Last Despoiler, whose boats ravaged the west coast when Aerys I Targaryen sat on the Iron Throne.

About Blessed Alton Greyjoy, who wished to find and conquer new lands beyond the Lonely Light. Of Thorvin Greyjoy, who made a blood oath to the Searing Blade, but betrayed his brother to his enemies. Of Loron Greyjoy, nicknamed the Bard, and his great and tragic friendship with the young Desmond Mallister, a knight from the green lands.

Towards the end of the great work of Hayreg, you learn of Lord Quellon Greyjoy, the wisest of men who have held the Sea Throne since the days of Aegon's Conquest. A huge man, six and a half feet tall, he was said to be strong like a bull and agile like a cat. As a young man, Quellon gained a reputation as a warrior fighting corsairs and slavers in the Summer Sea. A loyal servant of the Iron Throne, during the War of the Ninepenny Kings, he led a hundred rooks and thus played a decisive role in the battles at the Steps.Press to open...

Haegon Blackfyre and Searing Blade start a third rebellion in 219 AC.

All the deeds that took place in those days, both good and bad, have long been described. Maekar's leadership role, the actions of Aerion Brightfire, and the courage of Maekar's youngest son, and the second battle between Blood Raven and Searing Blade are highlighted... how he gave his sword. And Ser Aegor Rivers, Burning Blade, was taken alive and brought in chains to the Red Keep. Many still believe that if he had been put to the sword on the spot, as Prince Aerion and Blood Raven insisted, that would have put an immediate end to the Blackfires' ambitions.

But that didn't happen. Although Burning Blade was tried and sentenced for high treason, King Aerys spared his life by ordering him sent to the Wall to spend the rest of his days as a husband of the Night's Watch. Alas, this merciful decision did not turn out to be wise - the Blackfires still had many friends at court, and some willingly passed on the necessary information. A ship carrying Searing Blade and a dozen other convicts was intercepted in the Narrow Sea en route to Eastwatch.The freed Aigor Rivers returned to the Golden Company. Before the end of the year, he crowned Haegon's eldest son as Daemon III Blackfyre in Tyrosh and again began to plot against the king who had spared him.

Press to open...

Dagon Greyjoy is not reported to have been in contact with the Blackfires. He was simply engaged in traditional robbery in the Sunset Sea:

Aerys I put on the crown during the Great Spring Pestilence and was immediately forced to take care of restoring order in the state, for, as soon as the plague died down, the ships of Dagon Greyjoy, Lord of the Iron Islands, set off on predatory raids along the entire coast of the Sunset Sea. And in those same days, across the Narrow Sea, Searing Blade and the sons of Daemon Blackfyre were plotting. Apparently, in order to resolve all these issues, Aerys turned to Brynden Rivers and named him his right hand.

Press to open...

Searing Blade and the sons of Daemon Blackfire plot evil in Tyrosh, Dagon Greyjoy's krakens roam the Sunset Sea like wolves. They captured half the wealth of Bright Island and a hundred women.

Click to expand...

"Eg and I are going north to Winterfell," Dunk frowned. “Lord Beron Stark summons swords to drive the krakens off their shores forever.

"It's too cold out there for me," said Ser Maynard. - If you want to hunt krakens, you better go west. The Lannisters are building a fleet to strike at the Iron Men on their home islands. This is the only way to end Dagon Greyjoy. It is useless to beat him on land - he crawls into the sea. It must be finished on the water.

There was a reason for this, but somehow Dunk didn't want to fight the Iron Men at sea. The "White Lady", who was on her way from Dorne to Oldtown, was once attacked by pirates, and he put on armor and began to help the sailors.In a desperate bloody battle, Dunk almost fell overboard - if that happened, he would have been finished.

"It would do well for the throne to take a cue from Stark and Lannister," Ser Kyle remarked. “At least they fight, but what about the Targaryens?” King Aerys pores over books, Prince Rhaegal runs naked around the Red Keep, Prince Meyekar does not show his nose from Summer.

Eg stirred the fire with a stick, blowing sparks, and remained silent when his father was remembered. This pleased Dunk; it seemed that the boy had finally learned to keep his mouth shut.

"I blame it all on the Red Raven," Ser Kyle continued. “He is the Hand of the King, and it is his direct duty to oppose the krakens that sow terror along the shores of the Sunset Sea.

“His only eye is fixed on Tyrosh,” Ser Maynard shrugged, “where the Searing Blade in exile plots evil, along with the sons of Daemon Blackflame. He keeps the royal fleet close at hand should they wish to cross.

"The Burning Blade would be welcome here," Ser Kyle replied.– The Red Raven is the root of all our troubles, the worm that gnaws at the heart of our state.

"A man's head could be cut off for such words," Dunk frowned, remembering the hunchbacked septon of the Stone Sept. “Some might consider them treasonous.Click to expand...

Jay wrote:

North - neutral, apparently

Click to expand...

The North had many problems of its own:

Decades later, the North had to see how the ruling house had to deal with the uprising on Skagos, with the ironborn who resumed raids under Lord Dagon Greyjoy, with the invasion of the wildlings, led by the King beyond the Wall, Raymun Redbeard (it happened in 226 A.D. E). The Starks were destined to give their lives in each of these encounters, and yet their house was almost invariably lucky, probably due to the firm determination of most of the lords of Winterfell not to take part in the intrigues of the court in the south.

Click to expand...

The best ballet performances in the world. The most famous ballets of the world

in the 16th century have come a long way and have become popular all over the world by our time. Numerous ballet schools and theater troupes, whose number is increasing every year, are both classical and modern.

But if there are dozens of famous show ballets, and, in fact, they differ from other dance ensembles only in the level of skill, then national ballet theaters with a long history can be counted on the fingers.

Russian Ballet: Bolshoi and Mariinsky Theaters

You and I have something to be proud of, because Russian ballet is one of the best in the world. Swan Lake, The Nutcracker, the famous plastic ballets that appeared in our country at the beginning of the 20th century made Russia the second home of this art and provided our theaters with an endless stream of grateful spectators from all over the world.

Nowadays, the troupes of the Bolshoi and Mariinsky Theaters compete for the title of the best, whose skills are being improved day by day. The dancers of both troupes are selected among the pupils of the St. Petersburg Academy named after A. Ya. Vaganova, and from the first days of training, all its students dream of one day performing a solo part on the main stage of the country.

The dancers of both troupes are selected among the pupils of the St. Petersburg Academy named after A. Ya. Vaganova, and from the first days of training, all its students dream of one day performing a solo part on the main stage of the country.

French Ballet: Grand Opera

The cradle of world ballet, whose attitude to productions has been unchanged for three centuries, and where only classical academic dance exists, and everything else is regarded as a crime against art, is the ultimate dream for all dancers of the world.

Each year, its membership is replenished with only three dancers who have passed through so many selections, competitions and tests, as even the astronauts never dreamed of. Tickets to Paris operas are not cheap, and only the most wealthy connoisseurs of art can afford them, but the hall is full during each performance, because in addition to the French themselves, all Europeans come here who dream of admiring classical ballet.

United States: American Ballet Theater

Made famous by the release of The Black Swan, American Ballet Theater was founded by a soloist of the Russian Bolshoi Theater.

Having its own school, the ballet does not hire outside dancers and has a distinctive Russian-American style. The productions coexist with classic stories, such as the famous Nutcracker, and new dance styles. Many ballet connoisseurs claim that ABT has forgotten about the canons, but the popularity of this theater is growing year by year.

UK: Birmingham Royal Ballet

Curated by the Queen herself, the London Ballet is small in number of dancers, but distinguished by a strict selection of participants and repertoire. Here you will not meet modern trends and genre deviations. Perhaps that is why, unable to withstand the harsh traditions, many young stars of this ballet leave it and begin to create their own troupes.

It is not easy to get to the performance of the Royal Ballet, only the most noble and rich people of the world are awarded this, but once every three months charity evenings with an open entrance are organized here.

Austrian Ballet: Vienna Opera

The history of the Vienna Opera has a century and a half, and all this time the first soloists of the troupe are Russian dancers. Known for its annual balls, which didn't take place until World War II, the Vienna Opera House is Austria's most visited attraction. People come here to admire the talented dancers and, looking at their compatriots on stage, proudly speak their native language.

Known for its annual balls, which didn't take place until World War II, the Vienna Opera House is Austria's most visited attraction. People come here to admire the talented dancers and, looking at their compatriots on stage, proudly speak their native language.

It is very easy to get tickets here: thanks to the huge hall and the absence of resellers, you can do it on the day of the ballet, except for the days of premieres and the opening of the season.

So, if you want to see classical ballet performed by the most talented dancers, go to one of these theaters and enjoy the ancient art.

Ballet is called an integral part of the art of our country. Russian ballet is considered the most authoritative in the world, the standard. This review contains the success stories of five great Russian ballerinas, whom they still look up to.

Anna Pavlova

Outstanding ballerina Anna Pavlova was born into a family far from art. The desire to dance appeared in her at the age of 8 after the girl saw the ballet performance of Sleeping Beauty. At the age of 10, Anna Pavlova was accepted into the Imperial Theater School, and after graduation, into the troupe of the Mariinsky Theater.

At the age of 10, Anna Pavlova was accepted into the Imperial Theater School, and after graduation, into the troupe of the Mariinsky Theater.

Curiously, the novice ballerina was not put into the corps de ballet, but immediately began to give her responsible roles in productions. Anna Pavlova danced under the guidance of several choreographers, but the most successful and fruitful tandem, which had a fundamental influence on her style of performance, turned out with Mikhail Fokin.

Anna Pavlova supported the bold ideas of the choreographer and readily agreed to experiments. The miniature "The Dying Swan", which later became the hallmark of the Russian ballet, was almost impromptu. In this production, Fokine gave the ballerina more freedom, allowed her to feel the mood of The Swan on her own, to improvise. In one of the first reviews, the critic admired what he saw: “If it is possible for a ballerina on stage to imitate the movements of the noblest of birds, then this has been achieved:”.

Galina Ulanova

Galina Ulanova's fate was predetermined from the very beginning. The girl's mother worked as a ballet teacher, so Galina, even if she really wanted to, she could not bypass the ballet barre. Years of grueling training led to the fact that Galina Ulanova became the most titled artist of the Soviet Union.

After graduating from the choreographic college in 1928, Ulanova was accepted into the ballet troupe of the Leningrad Opera and Ballet Theatre. From the very first performances, the young ballerina attracted the attention of viewers and critics. A year later, Ulanova was entrusted to perform the leading part of Odette-Odile in Swan Lake. Giselle is considered one of the triumphant roles of the ballerina. Performing the scene of the heroine's madness, Galina Ulanova did it so soulfully and selflessly that even the men in the hall could not hold back their tears.

Galina Ulanova reached . She was imitated, the teachers of the leading ballet schools of the world demanded that the students do steps “like Ulanova”. The famous ballerina is the only one in the world to whom monuments were erected during her lifetime.

The famous ballerina is the only one in the world to whom monuments were erected during her lifetime.

Galina Ulanova danced on stage until she was 50 years old. She has always been strict and demanding of herself. Even in old age, the ballerina started every morning with classes and weighed 49 kg.

Olga Lepeshinskaya

For passionate temperament, sparkling technique and precision of movements Olga Lepeshinskaya was nicknamed "Dragonfly Jumper". The ballerina was born into a family of engineers. From early childhood, the girl literally raved about dancing, so her parents had no choice but to send her to the ballet school at the Bolshoi Theater.

Olga Lepeshinskaya easily coped with both classical ballet (Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty) and modern productions (The Red Poppy, The Flames of Paris). During the Great Patriotic War, Lepeshinskaya fearlessly performed at the front, raising the morale of the soldiers.

Title="Olga Lepeshinskaya -

ballerina with a passionate temperament. | Photo: www.etoretro.ru." border="0" vspace="5">

| Photo: www.etoretro.ru." border="0" vspace="5">

Olga Lepeshinskaya -

a ballerina with a passionate temperament. | Photo: www.etoretro.ru.

Despite the fact that the ballerina was Stalin's favorite and had many awards, she was very demanding of herself. Already at an advanced age, Olga Lepeshinskaya said that her choreography could not be called outstanding, but "natural technique and fiery temperament" made her inimitable.

Maya Plisetskaya

Maya Plisetskaya is another outstanding ballerina whose name is inscribed in golden letters in the history of Russian ballet. When the future artist was 12 years old, she was adopted by her aunt Shulamith Messerer. Plisetskaya's father was shot, and her mother and little brother were sent to Kazakhstan to a camp for the wives of traitors to the Motherland.

Aunt Plisetskaya was a ballerina at the Bolshoi Theatre, so Maya also began attending choreography classes. The girl achieved great success in this field and after graduating from college she was accepted into the troupe of the Bolshoi Theater.

The girl achieved great success in this field and after graduating from college she was accepted into the troupe of the Bolshoi Theater.

Plisetskaya's innate artistry, expressive plastique, and phenomenal jumps made her a prima ballerina. Maya Plisetskaya performed leading roles in all classical productions. She especially succeeded in tragic images. Also, the ballerina was not afraid of experiments in modern choreography.

After the ballerina was fired from the Bolshoi Theater in 1990, she did not despair and continued to give solo performances. Overflowing energy, and allowed Plisetskaya to make her debut in the production of "Ave Maya" on the day of her 70th birthday.

Ludmila Semenyaka

Beautiful ballerina Ludmila Semenyaka performed at the Mariinsky Theater when she was only 12 years old. A talented talent could not go unnoticed, so after some time Lyudmila Semenyaka was invited to the Bolshoi Theater. Galina Ulanova, who became her mentor, had a significant influence on the ballerina's work.

Semenyaka coped with any part so naturally and naturally that from the outside it seemed as if she was not making any effort, but simply enjoying the dance. At 19In 76, Lyudmila Ivanovna was awarded the Anna Pavlova Prize from the Paris Academy of Dance.

In the late 1990s, Lyudmila Semenyaka announced her retirement as a ballerina, but continued her activities as a teacher. Since 2002, Lyudmila Ivanovna has been a teacher-repetiteur at the Bolshoi Theater.

But he mastered the art of ballet in Russia, and most of his life he performed in the USA.

Classics are not only symphonies, operas, concertos and chamber music. Some of the most recognizable classical works have appeared in the form of a ballet. Ballet originated in Italy during the Renaissance and gradually developed into a technical form of dance that required a lot of training from the dancers. The first ballet company created was the Paris Opera Ballet, which was formed after King Louis XIV appointed Jean-Baptiste Lully as director of the Royal Academy of Music. Lully's compositions for ballet are considered by many musicologists to be a turning point in the development of the genre. Since then, the ballet's popularity has slowly faded from one country to another, giving composers of different nationalities the opportunity to compose some of their most famous works. Here are seven of the most popular and beloved ballets in the world.

Lully's compositions for ballet are considered by many musicologists to be a turning point in the development of the genre. Since then, the ballet's popularity has slowly faded from one country to another, giving composers of different nationalities the opportunity to compose some of their most famous works. Here are seven of the most popular and beloved ballets in the world.

Tchaikovsky wrote this timeless classical ballet in 1891, which is the most frequently performed ballet of the modern era. In America, for the first time, The Nutcracker appeared on stage only in 1944 (it was performed by the San Francisco Ballet). Since then, it has become a tradition to stage The Nutcracker during the New Year and Christmas season. This great ballet not only has the most recognizable music, but its story brings joy to both children and adults.

Swan Lake is the most technically and emotionally complex classical ballet. His music was way ahead of its time, and many of its early performers argued that Swan Lake was too difficult to dance. In fact, very little is known about the original first production, and what everyone is used to today is the production reworked by the famous choreographers Petipa and Ivanov. Swan Lake will always be considered the standard of classical ballets and will be performed for centuries.

In fact, very little is known about the original first production, and what everyone is used to today is the production reworked by the famous choreographers Petipa and Ivanov. Swan Lake will always be considered the standard of classical ballets and will be performed for centuries.

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream has been adapted to many art styles. The first full-length ballet (for the whole evening) based on this work was staged in 1962 by George Balanchine to the music of Mendelssohn. Today, A Midsummer Night's Dream is a very popular ballet that is loved by many.

The ballet "Coppelia" was written by the French composer Léo Delibes and choreographed by Arthur Saint-Leon. "Coppelia" is a light-hearted story depicting a man's conflict between idealism and realism, art and life, with vibrant music and lively dancing. Its world premiere at the Paris Opera was a huge success in 1871, and the ballet remains a success today, being in the repertory of many theaters.

Peter Pan

Peter Pan is a great ballet suitable for the whole family. The dances, sets and costumes are as colorful as the story itself. Peter Pan is relatively new to the world of ballet, and since there is no single classical version of it, ballet can be interpreted differently by every choreographer, choreographer, and music director. Although each production may differ from each other, the story remains almost the same, which is why this ballet was classified as a classic.

The Sleeping Beauty

The Sleeping Beauty was Tchaikovsky's first famous ballet. In it, music is no less important than dancing. The story of the Sleeping Beauty is the perfect combination of ballet-royal celebrations in a magnificent castle, the battle between good and evil and the triumphant victory of eternal love. The choreography was created by the world famous Marius Pepita, who also directed The Nutcracker and Swan Lake. This classical ballet will be performed until the end of time.

This classical ballet will be performed until the end of time.

Cinderella

There are many versions of Cinderella, but the most common is Sergei Prokofiev's version. Prokofiev began his work on Cinderella in 1940, but due to the Second World War he finished the score only in 1945. In 1948, choreographer Frederick Ashton staged the production in its entirety using Prokofiev's music, which was a huge success.

Ballet as a musical form evolved from a mere adjunct to a dance, to a specific compositional form that often had the same meaning as the accompanying dance. Originating in France in the 17th century, the dance form began as a theatrical dance. Formally up to 19th century, ballet did not receive "classical" status. In ballet, the terms "classical" and "romantic" have chronologically evolved from musical usage. Thus, in the 19th century, the classical period of ballet coincided with the era of romanticism in music. Ballet music composers of the 17th and 19th centuries, including Jean-Baptiste Lully and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, were predominantly in France and Russia. However, with increasing international fame, Tchaikovsky during his lifetime saw the spread of ballet musical composition and ballet in general throughout the Western world.

Ballet music composers of the 17th and 19th centuries, including Jean-Baptiste Lully and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, were predominantly in France and Russia. However, with increasing international fame, Tchaikovsky during his lifetime saw the spread of ballet musical composition and ballet in general throughout the Western world.

Collegiate YouTube

1 / 3

✪ Absolute rumor about the ballet "Sleeping Beauty"

✪ Dona nobis pacem Grant us peace I S Bach Mass h-moll Tatar Opera and Ballet Theater 2015

✪ ♫ Classical music for children.

Subtitles

History

- Until about the second half of the 19th century, the role of music in ballet was secondary, with the main emphasis on dance, while the music itself was simply borrowed from dance melodies. Writing "ballet music" used to be the work of musical artisans, not masters. For example, critics of the Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky perceived his writing of ballet music as something vile.

From the earliest ballets until the time of Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), ballet music was indistinguishable from ballroom dance music. Lully created a distinct style in which music would tell a story. The first "Ballet of Action" was staged in 1717. It was a story told without words. The pioneer was John Weaver (1673-1760). Both Lully and Jean-Philippe Rameau wrote an "opera - ballet", where the action was performed partly by dancing, partly singing, but ballet music gradually became less important.0016 The next big step took place in the early years of the nineteenth century, when ballet dancers began to use special rigid ballet shoes - pointe shoes. This allowed for a more fractional style of music. In 1832, the famous ballerina Marie Taglioni (1804-1884) demonstrated her dance on pointe for the first time. It was in Sylph. It was now possible for the music to become more expressive. Gradually the dances became more daring, with the dancers lifting into the air by the men.

Until the time of Tchaikovsky, the composer of ballet did not separate from the composer of symphonies. Ballet music was the accompaniment for solo and ensemble dance. Tchaikovsky's ballet "Swan Lake" was the first musical ballet work that was created by a symphonic composer. At the initiative of Tchaikovsky, ballet composers no longer wrote simple and light dance parts. Now the main focus of the ballet was not only on the dance; the composition after the dances took on equal importance. At the end of 19century Marius Petipa choreographer of Russian ballet and dance, worked with composers such as Caesar Pugni to create ballet masterpieces that both boasted of both complex dance and complex music. Petipa worked with Tchaikovsky, collaborating with the composer on his Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, or indirectly through a new edition of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake after the composer's death.

Ballet music was the accompaniment for solo and ensemble dance. Tchaikovsky's ballet "Swan Lake" was the first musical ballet work that was created by a symphonic composer. At the initiative of Tchaikovsky, ballet composers no longer wrote simple and light dance parts. Now the main focus of the ballet was not only on the dance; the composition after the dances took on equal importance. At the end of 19century Marius Petipa choreographer of Russian ballet and dance, worked with composers such as Caesar Pugni to create ballet masterpieces that both boasted of both complex dance and complex music. Petipa worked with Tchaikovsky, collaborating with the composer on his Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, or indirectly through a new edition of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake after the composer's death.

In many cases still short ballet scenes were used in operas to change scenery or costume. Perhaps the most famous example of ballet music as part of an opera is the "Dance of the Hours" from the opera La Gioconda (1876) by Amilcare Ponchielli.

A dramatic change in mood occurred when Igor Stravinsky's ballet The Rite of Spring (1913) was created.

The music was expressionistic and discordant, the movements were highly stylized. In 1924, George Antheil wrote The Mechanical Ballet. This was suitable for a film of moving objects, but not for dancers, although it was an innovation in the use of jazz music. From this starting point, ballet music is divided into two streams - modernism and jazz dance. George Gershwin attempted to fill this gap with his ambitious score for Let's Dance (1937), amounting to more than an hour of music, which covered the rational and technically kicked jazz and rumba. One of the scenes was written especially for the ballerina Harriet Hawthor.

Many say jazz dance is best represented by choreographer Jerome Robbins, who worked with Leonard Bernstein on West Side Story (1957). AT in some respects it is a return to "opera-ballet" as the story is mostly told in words. Modernism is best represented by Sergei Prokofiev in the ballet "Romeo and Juliet". This is an example of pure ballet, and there is no influence from jazz or any other kind of popular music.Another direction in the history of ballet music is the tendency towards the creative adaptation of old music.Ottorino Respighi processed the works of Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868) and their joint series in the ballet is called The Magic Shop, which premiered in 1919. The ballet audience prefers romantic music, so new ballets are combined with old works through new choreography. A famous example is "Sleep" - music by Felix Mendelssohn, adapted by John Lanchbury.

This is an example of pure ballet, and there is no influence from jazz or any other kind of popular music.Another direction in the history of ballet music is the tendency towards the creative adaptation of old music.Ottorino Respighi processed the works of Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868) and their joint series in the ballet is called The Magic Shop, which premiered in 1919. The ballet audience prefers romantic music, so new ballets are combined with old works through new choreography. A famous example is "Sleep" - music by Felix Mendelssohn, adapted by John Lanchbury.

Ballet composers

At the beginning of the 19th century, choreographers staged performances based on collected music, most often composed of popular and well-known opera fragments and song melodies. The first who tried to change the existing practice was the composer Jean-Madeleine Schneitzhoffer. For this, he was subjected to considerable criticism starting from his first work - the ballet "Proserpina" (1818):

The music belongs to a young man who, judging by the overture and some ballet motifs, deserves encouragement.

But I firmly believe (and experience supports my opinion) that motives skillfully chosen to situations always better serve the intentions of the choreographer and reveal his intention more clearly than almost completely new music, which, instead of explaining pantomime, itself awaits explanation.

Despite the attacks of critics, following Schneitzhoffer, other composers began to depart from the tradition of creating ballet scores assembled from musical fragments based on the motives of other famous (most often opera) works - Ferdinand Gerold, Fromental Halévy, and, first of all, and then fruitfully working with Marius Petipa, when creating his scores, he strictly followed the instructions of the choreographer and his plan - right down to the number of bars in each number. In the case of Saint-Leon, he even had to use melodies set by the choreographer: according to the memoirs of Karl Waltz, Saint-Leon, himself a violinist and musician, more than once whistled motives to Minkus, which he “feverishly translated into musical signs”.

This practice did not correspond to the principles of the same Schneitzhoffer, who valued his reputation as an independent author and always worked separately from the choreographer when creating scores (an exception was made only when creating the ballet "La Sylphide" together with

07/17/2012

Ballet is a stage art; it is an emotion embodied in musical and choreographic images.

Ballet - the highest level of choreography, in which dance art rises to the level of musical stage performance, arose as an aristocratic court art much later than dance, in the 15th-16th centuries.

The term "ballet" appeared in Renaissance Italy in the 16th century and meant not a performance, but a dance episode. Ballet is an art in which dance, the main expressive means of ballet, is closely connected with music, with a dramatic basis - a libretto, with scenography, with the work of a costume designer, lighting designer, etc.

The ballet is diverse: plot - classical narrative multi-act ballet, dramatic ballet; plotless - ballet-symphony, ballet-mood, miniature.

World scenes have seen many ballet performances based on masterpieces of literature to the music of brilliant composers. That is why the British Internet resource Listverse decided to compile its rating of the 10 best ballet performances in history.

1. Swan Lake

Composer : Pyotr Tchaikovsky

Choreographer : Julius Resinger

The first Moscow production of "Swan Lake" was not successful - its glorious history began almost twenty years later in St. Petersburg. But it was the Bolshoi Theater that contributed to the fact that the world was gifted with this masterpiece. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote his first ballet commissioned by the Bolshoi Theatre.

The famous Marius Petipa and his assistant Lev Ivanov, who went down in history primarily thanks to the staging of standard "swan" scenes, gave a happy stage life to "Swan Lake".

The Petipa-Ivanov version has become a classic. It underlies most subsequent productions of Swan Lake, except for the extremely modernist ones.

The prototype for the swan lake was the lake in the Davydov Lebedeva economy (now Cherkasy region, Ukraine), which Tchaikovsky visited shortly before writing the ballet. Resting there, the author spent more than one day on its shore, watching snow-white birds.

The plot is based on many folklore motifs, including an old German legend that tells about the beautiful princess Odette, who was turned into a swan by the curse of the evil sorcerer - knight Rothbart.

2. "Romeo and Juliet"

Composer : Sergei Prokofiev

Choreographer : Leonid Lavrovsky

Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet is one of the most popular ballets of the twentieth century. The premiere of the ballet took place in 1938 in Brno (Czechoslovakia). Widely known, however, was the version of the ballet, which was presented at the Kirov Theater in Leningrad in 1940

"Romeo and Juliet" - ballet in 3 acts 13 scenes with prologue and epilogue based on the tragedy of the same name by William Shakespeare. This ballet is a masterpiece of world art, embodied through music and amazing choreography. The performance itself is so impressive that it is worth watching at least once in a lifetime.

This ballet is a masterpiece of world art, embodied through music and amazing choreography. The performance itself is so impressive that it is worth watching at least once in a lifetime.

3. "Giselle"

Composer : Adolphe Adam

Choreographer : Jean Coralli

"Giselle" - "fantastic ballet" in two acts by the French composer Adolphe Adam on a libretto by Henri de Saint-Georges, Theophile Gauthier and Jean Coralli according to the legend retold by Heinrich Heine. In his book “On Germany”, Heine writes about the vilis - girls who died from unhappy love, who, having turned into magical creatures, dance to death the young people they meet at night, taking revenge on them for their ruined life.

The ballet premiered on June 28, 1841 at the Grand Opera, choreographed by J. Coralli and J. Perrault. The production was a huge success, there were good reviews in the press. Writer Jules Janin wrote: “There is nothing in this work. And fiction, and poetry, and music, and the composition of new pas, and beautiful dancers, and harmony, full of life, grace, energy. That's what is called ballet."

That's what is called ballet."

4. Nutcracker

Composer : Pyotr Tchaikovsky

Choreographer : Lev Ivanov and Marius Petipa

The history of stage performances of Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker, based on Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann's fairy tale The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, knows many author's editions. The ballet premiered at the Mariinsky Theater on December 6, 1892.

The premiere of the ballet was a great success. The ballet The Nutcracker continues and completes the series of ballets by P. I. Tchaikovsky that have become classics, in which the theme of the struggle between good and evil, begun in Swan Lake and continued in Sleeping Beauty, sounds.

A Christmas tale about a noble and beautiful enchanted prince turned into a Nutcracker doll, about a kind and selfless girl and their evil opponent the Mouse King, has always been loved by adults and children. Despite the fairy-tale plot, this is a work of real ballet mastery with elements of mysticism and philosophy.

5. La Bayadère

Composer : Ludwig Minkus

Choreographer : Marius Petipa

La Bayadère - a ballet in four acts and seven scenes with the apotheosis of choreographer Marius Petipa to music by Ludwig Fyodorovich Minkus.

The literary source of the ballet "La Bayadère" is the drama of the Indian classic Kalidasa "Shakuntala" and the ballad of W. Goethe "God and the bayadère". The plot is based on a romantic oriental legend about the unhappy love of a bayadère and a brave warrior. "La Bayadère" is an exemplary work of one of the stylistic trends of the 19th century - eclecticism. There is both mysticism and symbolism in "La Bayadère": the feeling that from the first scene a "sword punishing from heaven" is raised above the heroes.

6. "The sacred spring"

Composer : Igor Stravinsky

Choreographer : Vaslav Nijinsky

The Rite of Spring is a ballet by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, premiered on 29 May 1913 at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées in Paris.

The idea of The Rite of Spring was based on Stravinsky's dream, in which he saw an ancient ritual - a young girl, surrounded by elders, dances to exhaustion to awaken spring, and dies. Stravinsky worked on music at the same time as Roerich, who wrote sketches for scenery and costumes.

There is no plot as such in the ballet. The content of The Rite of Spring is described by the composer as follows: “The bright Resurrection of nature, which is reborn to a new life, a complete resurrection, a spontaneous resurrection of the conception of the world”

7. “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

Composer : Felix Mendelssohn

Choreographer : Frederick Ashton

A Midsummer Night's Dream is a comedy by William Shakespeare in 5 acts. It is believed that A Midsummer Night's Dream was written between 1594 and 1596. It is possible that Shakespeare created the play specifically for the wedding of a certain aristocrat or for the celebration by Queen Elizabeth I of St. John the Baptist.

John the Baptist.

Musical accompaniment to the play was written in 1826 by Felix Mendelssohn. Two of the most famous ballet productions were created in the 60s: George Balanchine directed his Dream in 1962 for the NYCB, and in 1964 Frederick Ashton did it for the Royal Ballet.

In this production, Ashton condenses A Midsummer Night's Dream and reduces it to forest scenes only, focusing on the magical king of the fairies and elves Oberon and his wife Titania, Athenian artisans and peasants who stumble upon a moonlit magical night.

Finely honed choreography has Ashton's characteristic feature - precision, lightness, fluency.

8. Sleeping Beauty

Composer : Pyotr Tchaikovsky

Choreographer : Marius Petipa

The Sleeping Beauty ballet by P.I. Tchaikovsky - Marius Petipa is called "an encyclopedia of classical dance". The carefully constructed ballet amazes with the splendor of various choreographic colors. But as always, at the center of every Petipa performance is a ballerina. In the first act, Aurora is a young girl who perceives the world around her lightly and naively, in the second, she is an alluring ghost, summoned from a long-term dream by the Lilac fairy, in the finale, she is a happy princess who has found her betrothed.

In the first act, Aurora is a young girl who perceives the world around her lightly and naively, in the second, she is an alluring ghost, summoned from a long-term dream by the Lilac fairy, in the finale, she is a happy princess who has found her betrothed.

The inventive genius of Petipa dazzles the audience with a bizarre pattern of diverse dances, the top of which is the solemn pas de deux of lovers, Princess Aurora and Prince Desire. Thanks to the music of P.I. Tchaikovsky, the children's fairy tale became a poem about the struggle between good (the Lilac fairy) and evil (the Carabosse fairy). The Sleeping Beauty is a genuine musical and choreographic symphony in which music and dance are merged into one.

9. "Don Quixote"

Composer : Ludwig Minkus

Choreographer : Marius Petipa

Don Quixote is one of the most life-affirming, bright and festive works of the ballet theatre. Interestingly, despite its name, this brilliant ballet is by no means a staging of the famous novel by Miguel de Cervantes, but an independent choreographic work by Marius Petipa based on Don Quixote.