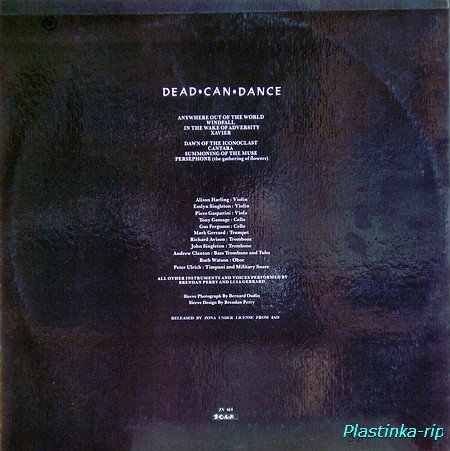

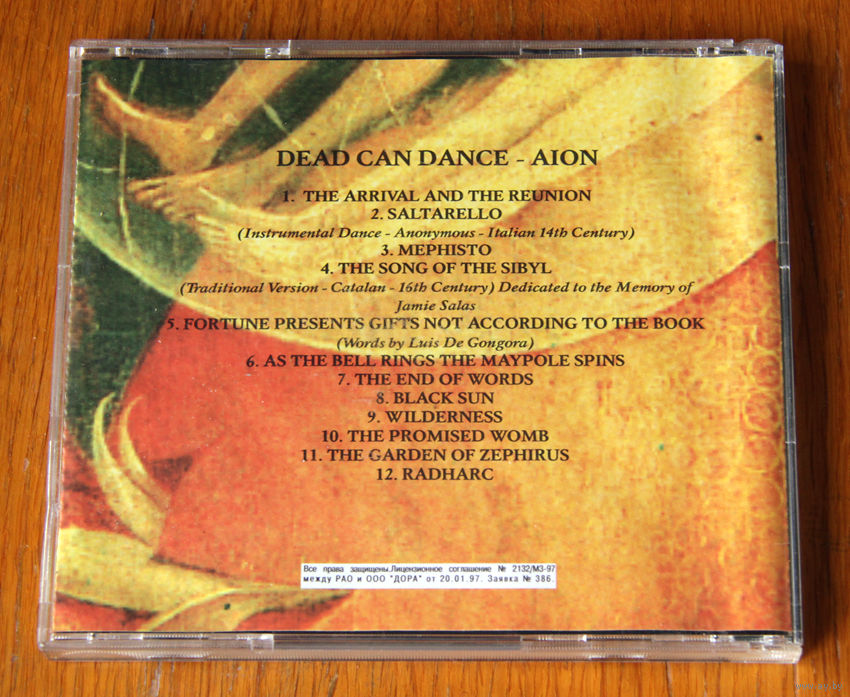

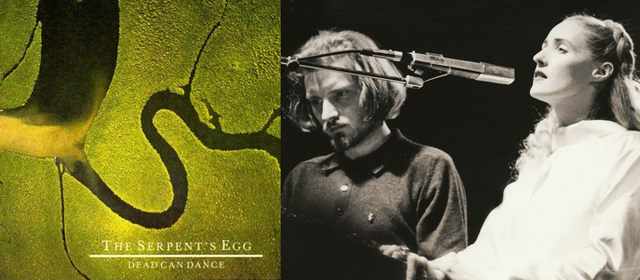

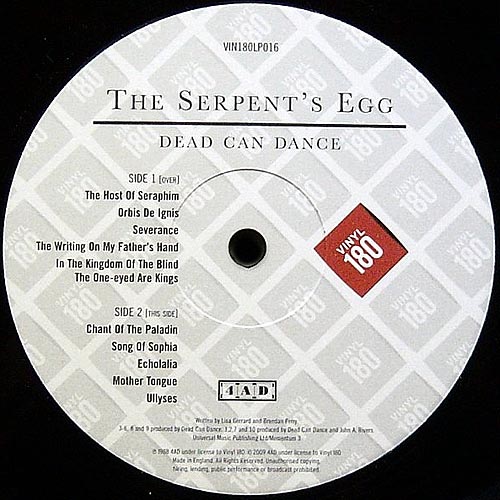

Dead can dance how fortunate the man with none

How Fortunate the Man With None (Remastered) by Dead Can Dance on Beatport

Track

Link:

Embed:

Artists Dead Can Dance

- Release

- Length 9:14

- Released 2022-08-18

- BPM 119

- Key G min

- Genre House

- Label 4AD

People Also Bought

Recommended Tracks

-

Be Kind Radio Edit

Pat The Cat, UnderCover Squad

-

Tell Me About the Forest (You Once Called Home) Remastered

Dead Can Dance

-

The Carnival Is Over Remastered

Dead Can Dance

-

The Ubiquitous Mr. Lovegrove Remastered

Dead Can Dance

-

Las Aguilas Paradise Mix

Samoa Beach

-

Yousax Original Mix

Rolando Becket

-

Higher Original Mix

Gil Everest

-

La Morenita Original Mix

Javier Mio

-

Rest Original Mix

Urulu

-

Ich lieb dich nicht immer Slow-down Remix

Pixie Paris

-

Used To Dream Original Mix

Calippo

-

Tear Club Original Mix

Moullinex

How fortunate the man with none – Discursive anomalies

-

There is something to be said for iterations on themes. It makes it hard to miss the point, and even those who do not pay close attention get a chance to catch up. Those who heard it the first time now know it even more, and those who now hear it for the first time are now up to speed. As a method of getting everyone on the same page, iteration is hard to surpass.

If it were sufficient to say something once, a whole host of problems would have been solved right after the Sermon on the Mount. Clearly, there is still work to be done.

Brecht iterates on the same theme four times, using four examples to drive home his point. Three of these are of historical character, and anyone familiar with the Ancients will know both their virtues and their fate. The last example is you as a reader, supposing that you are a virtuous person and see yourself as such. The implication being that you share the same situation as these great persons of the past.

Three of these are of historical character, and anyone familiar with the Ancients will know both their virtues and their fate. The last example is you as a reader, supposing that you are a virtuous person and see yourself as such. The implication being that you share the same situation as these great persons of the past.

In each case, he ends with the titular phrase “how fortunate the man with none”, emphasizing the distance between then and now. It is a striking phrase, at once both acknowledging and rejecting virtue as a thing to strive for; virtue is what brings ruin to the invoked Ancients, even in their own times. Solomon’s wisdom didn’t help much in the end; Caesar’s courage brought him to an abrupt end; and Socrates’ honesty didn’t match his fate. How much better would it have been had they been just a tad less of themselves, and thus able to save themselves from themselves?

A direct reader might leap to the interpretation that this is the right and proper thing to do – renounce outdated virtues and morals in favor of pragmatic efficiency. To be sure, modern society confronts its citizens with many situations where the “right” thing to do is to not care too much or apply too much empathy. Whether it be the beggar in the street, the loud noises and screams from the couple living upstairs or the ever present temptation to be less than honest in an attempt to get a bureaucratic edge – the act of doing the right thing will more often than not turn out to be counterproductive to whatever it is you are doing, or get you into trouble you could have easily avoided. There is the right and moral thing to do, and there is the right and efficient thing to do, and every time you hastily pass by a beggar or ignore yet another upstairs ruckus, you have made a choice between the two.

To be sure, modern society confronts its citizens with many situations where the “right” thing to do is to not care too much or apply too much empathy. Whether it be the beggar in the street, the loud noises and screams from the couple living upstairs or the ever present temptation to be less than honest in an attempt to get a bureaucratic edge – the act of doing the right thing will more often than not turn out to be counterproductive to whatever it is you are doing, or get you into trouble you could have easily avoided. There is the right and moral thing to do, and there is the right and efficient thing to do, and every time you hastily pass by a beggar or ignore yet another upstairs ruckus, you have made a choice between the two.

Brecht is not in the business of making you feel bad about this choice. Feeling bad is not the proper revolutionary spirit. Rather, the proper stance towards this dilemma is to acknowledge it as the endemic and eternal moral condition of modernity: you will always face this choice, even if you do the right thing. Even if you work yourself to exhaustion to make the (or your) world a better place, the same standoff between virtue and pragmatism will inevitably play itself out. The only difference being that you are now tired and in a position to think: how fortunate are those who do not have to do what you do. How fortunate are those who can not care.

Even if you work yourself to exhaustion to make the (or your) world a better place, the same standoff between virtue and pragmatism will inevitably play itself out. The only difference being that you are now tired and in a position to think: how fortunate are those who do not have to do what you do. How fortunate are those who can not care.

This brings into play the distinction between alienation and unease. Being made uneasy when confronted with these choices is only natural – seeing others suffer should never not make one uneasy. Alienation, on the other hand, means that you do not recognize yourself in the situation that you are actually in. Neither is a particularly comfortable state of mind, but the difference lies in the directness with which one confronts matters. Unease is here and now; alienation is not.

A person has to be alienated in order to function in a modern society. Confronting the reality of the situation without filters lead to madness. Do not investigate too closely where your food, clothes or wealth come from, and always be prepared to build thick walls against the suffering at the source of these should you ever find out. The unease will eat you alive otherwise, and possibly others with you.

The unease will eat you alive otherwise, and possibly others with you.

The proper stance towards this is to acknowledge that the world came into being before we did, and that we are not responsible for putting it in place. But we are also not helpless automatons bound by the forces of determinism, unable to make moral choices for ourselves. We have to alienate ourselves from our alienation, as it were, and reaffirm some semblance of right and virtue in the midst of all this modern pragmatic efficiency. We cannot save the world all by ourselves, but this is not a reason to not do anything at all. We are still human.

When Brecht says “how fortunate the man with none”, he says it to invoke a subject who has given up on their humanity, who just plays along in order to get by. He says it four times, three times to invoke history, one time to invoke you. The hope being that you haven’t given up your humanity just yet, and that you choose to not turn into an efficient clerk organizing train timetables without thinking too much about either cargo or destinations. That you can resist the path of least resistance, the one which simply follows orders.

That you can resist the path of least resistance, the one which simply follows orders.

It is a hope that bears further iterations. Despite the unease.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Brecht: How fortunate the man with none

Sergey KUZNETSOV. Alive and adults

Sergey KUZNETSOV. Alive and adults. - M .: Livebook, 2019 (in fact - 2018).

The space in Sergey Yu. Kuznetsov's trilogy is divided into two opposing parts: the world of the living and the world of the dead, which coexist not in a metaphysical, but in the most ordinary - geographical sense. The bright and optimistic world of the living is most similar to the world of idealized late Soviet childhood; the world of the dead is the world of the pure, profit and temptations from Soviet propaganda, and death - the transition from one world to another - is semantically identical to emigration here. Dying (even as a result of an accident), a person actually makes his choice: now for the living he is a stranger, an enemy, a renegade, and members of his family are under suspicion. In principle, any plot could be placed inside this space - from horror to spy thriller, but Sergey Yu. Kuznetsov opts for teenage fantasy. As a result, Alive and Adults is at the same time a novel of upbringing, an exquisite metaphor for overcoming death, an original rethinking of the Soviet experience, and, last but not least, an ingenuously gripping story about friendship and growing up.

In principle, any plot could be placed inside this space - from horror to spy thriller, but Sergey Yu. Kuznetsov opts for teenage fantasy. As a result, Alive and Adults is at the same time a novel of upbringing, an exquisite metaphor for overcoming death, an original rethinking of the Soviet experience, and, last but not least, an ingenuously gripping story about friendship and growing up.

Sergey Kuznetsov. Alive and adults. - M .: Livebook, 2019 (in fact - 2018).

Nominated Galina Yuzefovich.

Dmitry Bavilsky :

Surprisingly, Sergei Kuznetsov's fantasy trilogy, read immediately after Licinius Quintus, Mikhail Korolyuk's trilogy about falling into the socialist past, looks like its negative.

More precisely, in a positive way, since it was written not from imperial, but from humanistic, “universal” positions, gradually teaching readers the “right position in life”.

These two books are large in volume (the book edition of Living and Adults contains 974 pages versus 1062 for Korolyuk), they have three parts, correlating as “thesis”, “antithesis” and “synthesis” (Korolyuk, however, inconclusive) who study the Soviet past from the point of view of the "adult" present, rising above what was a mountain of "new experience".

Kuznetsov also has a storyline of a mathematical prodigy who is able to calculate the location of parallel and border worlds, grouped near the Border of the transition between the world of the dead and the world of the living, in which four brave schoolchildren (Marina, Nika, Gosh and Lyova) live, busy destroying this very Borders.

It is not clear why they are doing this, it seems to be to free humanity from the unnecessary division into friends and foes that interferes with absolute freedom, however, the further into the text of "Alive and Adults" the more the division of the world into antagonistic halves looks logical and even reasonable.

Judge for yourself.

Schoolchildren live in a country reminiscent of the late Soviet period - Sergey Kuznetsov was clearly inspired by the experience of his own childhood and youth: his trilogy is another way to “close the gestalt” of his own “experience of lack of freedom”, to which everyone who lived in the USSR was sentenced, or, on the contrary, to try once again to relive the period when the trees were large, all people seemed to be brothers and sisters, and there was nothing more important than love, friendship, freedom, equality, brotherhood.

The country in which Marina, Nika, Gosha and Lyova live desperately resembles the Soviet Union, but for the "safety" of narrative operations, as well as for the sake of creative freedom, Kuznetsov shifts the description of reality towards light historical generalizations - he takes not so much from the USSR the specifics of everyday life (which he reconstructs, however, very carefully), as much as the logic of the development of territories surrounded by enemies, saturated with detective work and state suspicion, which easily turn into a lack of elementary freedoms and a total dictate of ideological control.

Historical reality shifts towards the plot scheme, and proper names are played with puns - the names of Soviet and Western films, books, firms, cities, countries turn into easily recognizable neologisms.

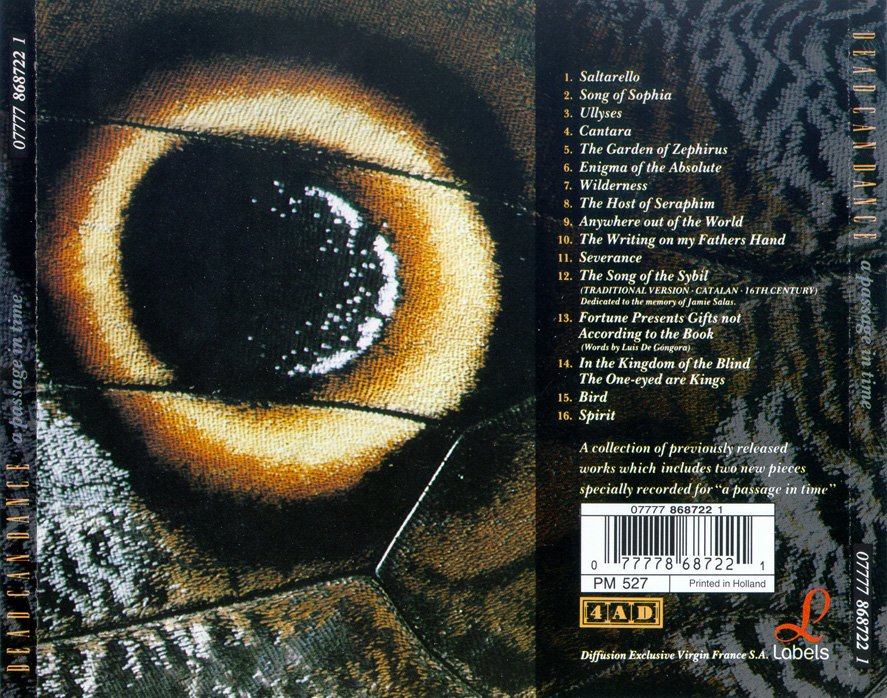

This is how the books “Friday Ends on Monday” and “Toward a Thunderstorm”, “Mathematicians Laugh” and “Glass Dirk”, the rock group “The Living Can Dance”, the cities of Paris and View York come into being.

Thus, the author, on the one hand, pays tribute to the predecessors and sources of his inspiration, on the other hand, he shows the features of the method, punning at all meaningful levels, from shoveling reality to meaningful metamorphoses that turn the meaning we are used to inside out.

However, Kuznetsov is silent about the main prototypes, voluntary or involuntary, or perhaps he simply forgets about them - like a Soviet person who grew up in late Soviet culture, for which other names and titles became a natural habitat, dissolving in it to the fullest. indistinction.

Of course, Anatoly Rybakov's trilogy ("Dirk", "Bronze Bird", "The Last Summer of Childhood"), constantly mentioned by Leva in the first volume, is an important example of adventurous adventures within everyday life, when a young man is able to open abysses at every turn, however , much more important for understanding the origin of "Alive and Adults" is seen, well, for example, the work of Vladislav Krapivin.

A principled abstract humanist of the last Brezhnev decades (who lives, by the way, still), Krapivin for decades wrote eternal stories about the “tears of a child”, childish resentment faced with the injustice of an indifferent world and the enduring “thirst for freedom” of children, connected primarily , with an indefatigable "flight of fancy".

A subtle psychologist, able to bring the reader to tears by the clash of "truth" and "fiction", Krapivin defiantly lived on top of the scoop, although he enjoyed all the privileges available to him.

Here are Kuznetsov's schoolchildren, who are trying to destroy the Boundary between the worlds (there is no need to look for metaphysics in the fact that the "living" are opposed by the "dead" - it's just a division into "us" and "them"), first they come into conflict with their own special services , then with foreign servicemen, and when they are convinced that our Office and their Office work together, they begin to cooperate with them.

And Marina, the most important and honest girl of this friendly special detachment, who does not burn in fire and does not sink in water, managing to roam between worlds without any accompaniment, even enters the Academy - the main service university of the living, dizzying career to the most powerful top.

Marina tells her friends that she will be an intruder of the "forces of good" who have infiltrated the system through her.

And friends, of course, believe her, even when in the most dangerous and hopeless situations "helicopters" of adults appear "out of the machine" - our valiant scouts, pulling pioneer heroes, for example, from the wild jungle, where on domestic children bloodthirsty natives hunt.

You can't go anywhere without adults, but for our guys, everything is built on trust, and also on a sense of their own exclusivity, which the sacrifices they constantly make cannot shake.

Usually people die in the "Alive and Adults" who treat our guys well and try to help the fellows in every possible way.

In the first volume (“Living and Adults. The Beginning”), a young teacher, Zinochka, dies; in the second (“Alive and adults. On the other side”) - Sandro, a resident of View York, who let the guys in to stay when they had nowhere to spend the night.

Helping to free Gosha from prison, he dies, but the pioneers, as if nothing had happened, return in the third volume ("Alive and adults: The world as we see it") to his mother, Senera Fernandez, since the dead, It seems like there is no time and memory.

However, closer to the end, Soviet schoolchildren, together with domestic servicemen, finally achieve the loosening of the boundaries and changes in the physical characteristics of both worlds, because of which the dead begin to change and grow old - their eternity is exhausted.

And here it is no longer clear who rocked the boat more - four friends or cunning servicemen, who realized in time that the more people cross the Borders, the more mobile they become.

Having turned the Frontier into a commercial venture, the Office is starting an international festival where hundreds of the dead are to arrive in the capital of the living world.

Then the Border will become completely conditional and the country, which previously defended itself from all other states, will be covered with an even layer of commercial stalls with fashionable dead goods.

The thing is that if the “living” are the people of the Soviet country, then the “dead” are Western capitalists, they have the best clothes and the most interesting films, chewing gum, rock bands and the absolute restlessness of the total consumer society.

The living, it seems, were lucky to be born in the most calm, bright and spacious country, however, in a strange way, the truth of existence is in a completely different place - and there is no greater reward for a living person than, for example, a business trip to the dead, where you can stock up on mass fashion rags and glossy magazines.

The world is ambiguous, Kuznetsov teaches, moving from a “romance of growing up” and a “romance of education” to a thriller similar to a computer game with shooters, and then to a thriller with the participation of infernal forces (including zombies) summoned from the very the depths of a dead universe: it seems that the main author's interest and the main fuel of the trilogy is the constant change of genres that flow into each other without having time to take shape into something solid.

When plots are put on stream in modern culture, the play of genres and discourses turns out to be the most lively of the author's possibilities.

It is she who, by regularly changing the rules of perception, makes the narration somewhat unpredictable.

Sorokin taught us this method of total renewal of the "memory of the genre", but most of all Western cinema plays this way - for example, Tarantino with Rodriguez, although the most successful example of a mix of "old form" and new content is "Brokeback Mountain".

In it, director Ang Lee mixes a pair of enduring national myths that have never crossed before: the legend of the courageous cowboys, which is superimposed on the logic of a tearful gay drama.

It is significant that two incompatible stories are put into one scheme by an émigré director who is able to look at the American unconscious from the outside: Lee plays with differently directed storylines like a postmodernist juggling with ready-made "information blocks".

In the long list, Alexander Pelevin acts in a similar way, “Four” of which, however, clearly follow the “rules of genres” (moreover, three at once), and do not “open the reception”, as Sergei Kuznetsov, a French emigrant in the first generation, intended .

In his trilogy, he takes the forms of world thriller and horror in order to graft them onto the Russian wild “youth novel” and fantasy about hitmen who are gradually realizing that everything is ambiguous in this world and there is no one-size-fits-all truth in the world.

The fact that everyone has their own truth and feel sorry for everyone is already a feature of noir, which flickers somewhere in the backyard of the genre of "Alive and Adults": the dead Abroad, written off from conditional America, is sustained precisely in such tones of a black-and-white, fast-moving film .

Horror, consisting of foreign elements, is filled with native content: most of all, this hit in View York reminds Nikolay Nosov's "Dunno's Journey to the Moon" - because it is not far from View York to San Komarik, not to mention Los -Svinos, Los Cabanos and Los Poganos.

And not only linguistically.

Mom Gosha, who disappeared in one of the buffer zones on the White Sea, but surfaced on the other side of the Border, spent almost half a year among the dead, after which she began working for the Office with a vengeance (she used to be a dissident and hated servicemen).

« They covered the windows of our houses with their dead advertising posters. Even worse, they demolished our old houses, they built new, dead ones in their place. They were built for us to work in. For the work they pay us dead money - and in order to have something to spend on, they built their shops on our squares and there they sell us their dead things for their dead money.

Even worse, they demolished our old houses, they built new, dead ones in their place. They were built for us to work in. For the work they pay us dead money - and in order to have something to spend on, they built their shops on our squares and there they sell us their dead things for their dead money.

Instead of five living skyscrapers, they erected dozens of dead buildings, huge to the sky. Living people cannot live in such houses. These are houses for the dead.

Our city is the city of the dead.

Where there were living cozy yards, there are dead buildings.

Where there were spacious squares, there are dead shops.

Where there were wide, free avenues - there is a camp of dead cars, motionless, night and day.

Where there were bushes and trees, there was only gas and burning.

We are afraid to walk on our streets.

We are afraid to enter our entrances.

We are afraid to let our children leave the house.

If you lived alone in the Open World, I wouldn't even let you go to school alone.

Because the dead are walking around the city - people like Orlok.

They are looking for a living, they are looking for a victim, they are thirsty for blood, living flesh.

I wouldn't let you go outside, son.

I would say: stay at home, read books.

But they took our books from us too. Instead, they gave us millions of dead books.

Instead of our films, live films about courage and love, they gave us dead films, thousands of dead films about ghosts, zombies and vampires… »

which begins to seem that she describes the capital of the living, but no - an inhuman caricature of the "welfare society", as if taken from the Alligator magazine, a description of the very View York that any of the living dreams of visiting.

It seems that Gosha's mother is completely confused, and I am confused along with her: after all, the dead in this book look like the living - they can be afraid, do heroic deeds, contrary to their mean nature, transform from bad to good and vice versa (with the exception of perhaps the most notorious maniac villains), while living pioneer heroes are doomed to serve numerous plot moves, which is why their range is narrower, and they themselves are more schematic.

Constant genre mutations are a test not only for the characters, but also for the author, who leads them through the thorns of constant change.

And the plasticity of the prose here turns out to be more important than the overall construction, which looks logical inside the fantasy trilogy, but does not stand up to the outside view.

The living are arguing with the dead in a variety of genre states of aggregation and it is no longer possible to make out which side the truth is on.

Moreover, the closer to the end, the more and more holes there are in Kuznetsov's structure, just like in that same Border between the Open World of the Undead and the world of the living, locked inside forced socialism.

In the third volume, the author focuses on the canons of completely commercial Western genres, worn out from constant use, in which winning by any means is more important than saving friends and, moreover, one's own face.

So it turns out that the dispute between the living and the dead in this trilogy is a duel between two traditions of mass fiction, Russian and world.

Kuznetsov connects them approximately like "living water" and "dead water": where he includes "Rybakov" or "Krapivin" it is interesting, but where noir and shooters begin - not very much.

Apparently, I'm just not the age category that the author expects.

On the other hand, who, apart from Sergei's peers, remembers ice cream in a waffle cone for 19 kopecks and soda in a vending machine for three?

However, if we perceive the main content of The Alive and Adults precisely as a literary meta-dispute between two traditions, all the conceptual contradictions of the trilogy are instantly removed.

True, which of the two approaches won here, I did not understand.

Are you for the Moon or for the Sun?

Most likely, friendship won.

Vladimir Berezin :

Underadults

God only knows how Kuznetsov's text got on this list. If he was on the short list of "Kniguru", I would not be surprised, because this text, in general, is about teenagers and talks about teenagers.

But for me this book (horrible in size, 60 author's sheets, a thousand pages) turned out to be more interesting to many than the books I read this summer. And it’s not at all because I like the novel “Alive and Adults” so much.

The main feature of the book (both the strength and the weakness of this text) is that it is a novel not just about teenagers, but about teenagers from the late USSR. This is a well-known way of creating literature - it is written “by myself”, while I understand this “by myself” very well, because I grew up at the same time, in the same city. Whatever the author writes "by himself", the Second School and the novel "Crystal Coffin" come out. No matter how he kills the film critic in himself, he will name the subspecies of the dead "fulci" and "romeros". As soon as he begins to describe torture and dismemberment with feeling, you remember that the author wrote about the maniac "The Skin of a Butterfly".

Whatever the author writes "by himself", the Second School and the novel "Crystal Coffin" come out. No matter how he kills the film critic in himself, he will name the subspecies of the dead "fulci" and "romeros". As soon as he begins to describe torture and dismemberment with feeling, you remember that the author wrote about the maniac "The Skin of a Butterfly".

In Kuznetsov's "world of the living" there are four muskets... (crossed out), four friends of Harry Poe... (crossed out), four Soviet schoolchildren, only the author dealt with the Soviet world with the help of contextual substitution: - .

That is, in a semi-memoir story about seventh-eighth graders (who later grow into third-year students), the words "West" and "capitalist countries" are replaced by the words "World of the Dead." And in this world of the dead is full of beautiful things, from jeans to televisions, but in the socialist world of the living there is a real stagnation, gloomy school discipline, the struggle with earrings among schoolgirls and the cult of the great war with the dead. Here, however, a terrible punning machine begins to work, turning "polyethylene" into "polyethylene", and the monument to Gogol into a monument to Mogol. Something is always wrong with these puns, although you can imagine how the author tried and came up with this Pelevinism, how he laughed with his family and friends, and the bilious reader strives to compare all this not even with Pelevin, but with Voinovich. By the way, there is something else with the editing, because the “bird key” seems to have settled into the text instead of the supposed “bird's beak”, well, and all sorts of other case inconsistencies. But what a volume! You don't follow.

Here, however, a terrible punning machine begins to work, turning "polyethylene" into "polyethylene", and the monument to Gogol into a monument to Mogol. Something is always wrong with these puns, although you can imagine how the author tried and came up with this Pelevinism, how he laughed with his family and friends, and the bilious reader strives to compare all this not even with Pelevin, but with Voinovich. By the way, there is something else with the editing, because the “bird key” seems to have settled into the text instead of the supposed “bird's beak”, well, and all sorts of other case inconsistencies. But what a volume! You don't follow.

Another thing is important: there are two layers in the book - Soviet childhood, which includes a nostalgic mechanism in adults just like a chopped onion causes tears, and a layer of adventures of schoolchildren of the “living world” with pistols firing silver bullets, ritual knives waving and so on. . From time to time, the heroes stop in the middle of the chase and begin to talk about the fractal structure of the world. These layers are connected like water and oil - that is, in no way. The nostalgic part touches some strings in me, but the part built on adventures just reminds me of the old and current writer Lukyanenko.

These layers are connected like water and oil - that is, in no way. The nostalgic part touches some strings in me, but the part built on adventures just reminds me of the old and current writer Lukyanenko.

Here we need to make a digression: the experience of the Kuznetsov generation (and it is my generation) is unique. People were born and formed in one world, and then found themselves in another. But those who are now thirteen, they were born and live in this new world of things. As a school teacher, I peer at the students with great interest, and over and over again I find that the children's problems of the late USSR do not interest teenagers at all. And even teenage love is different now. And betrayal then was arranged in a completely different way than now. However, what am I saying: the author himself created a summer school, quite similar to Hogwarts (only paid) and goes there as Dumbledore. So he knows about teenage problems as much as I do.

A separate question, which thanks to this novel, I began to think about, is the question of length (And here the topic itself provokes the author - let's talk about Soviet cinema in terms of "The Living and the Dead", but without Simonov, but let's put all our memories there - from video cassettes and bands, but let's rename them so that the reader has a funny recognition click. So it turns out a very long novel - under that very thousand pages. And I began to think about how the author should adjust to his target audience. On the one hand , in "War and Peace" there is also quite a lot of text, but on the other hand, go ahead, say at least in front of a mirror: "My book will be required to be read in the same way as Tolstoy. "No, if the writer honestly considers himself a conductor of meanings from the divine world to human, then he does not care about the audience, the target audience and everything in general, not to mention the fee.But the worst thing is when he starts to rush between these two worlds, as between the world of the dead and the living, however this is not about the author, but so, by the way.

So it turns out a very long novel - under that very thousand pages. And I began to think about how the author should adjust to his target audience. On the one hand , in "War and Peace" there is also quite a lot of text, but on the other hand, go ahead, say at least in front of a mirror: "My book will be required to be read in the same way as Tolstoy. "No, if the writer honestly considers himself a conductor of meanings from the divine world to human, then he does not care about the audience, the target audience and everything in general, not to mention the fee.But the worst thing is when he starts to rush between these two worlds, as between the world of the dead and the living, however this is not about the author, but so, by the way.

The problem is that Kuznetsov is a very smart person. I, for one, really like how he tries to reconcile logic and corporate obligations. He is well-read, active and therefore pronounces different meanings more than is necessary in prose. Therefore, there are some difficulties with the target audience of this text. This complexity is exhaustively described by one hero of Dumas: "For Athos, this is too much, but for the Comte de la Fer, this is too little." For a teenager it is too difficult, and for an adult it is too much about teenagers.

This complexity is exhaustively described by one hero of Dumas: "For Athos, this is too much, but for the Comte de la Fer, this is too little." For a teenager it is too difficult, and for an adult it is too much about teenagers.

In a word, this novel is wonderful. And of course, it symbolizes the new horizons of fantasy literature, addressed to the "teenage theme" (that's a nasty phrase, yes). And perhaps the ideal audience for this text is parents reflecting on the fate of their children who have ceased to be children, remaining, so to speak, immature.

Andrey Vasilevsky :

Good prose by a good prose writer (read like Kuznetsov's other books, with pleasure) and yet... alas, alas. Everyone notes that the “world of the living” created by the author partly corresponds to the late Soviet time familiar to us, conditionally - the 70s. The author introduces fantastic assumptions into this recognizable “reality” (fiction writers often work this way, but the prose writer Sergei Kuznetsov does not seem to have such previous experience). Introduces, "without noticing" that these assumptions affect the ontological (someone would prefer the term "metaphysical" in this case) foundations of the universe. Let me suggest that under such ontological/metaphysical prerequisites, the human society (“the world of the living”) could hardly develop/evolve/exist as it happened in real human history and in the forms familiar to us; The "world of the living" would then not be "something" different, but different in everything. Simply put: there could not have been any conditional “Soviet Union of the 70s” there. Yes, and the conditional "West" too. What would happen? I can't imagine it. I don't think Sergey Kuznetsov can either.

Introduces, "without noticing" that these assumptions affect the ontological (someone would prefer the term "metaphysical" in this case) foundations of the universe. Let me suggest that under such ontological/metaphysical prerequisites, the human society (“the world of the living”) could hardly develop/evolve/exist as it happened in real human history and in the forms familiar to us; The "world of the living" would then not be "something" different, but different in everything. Simply put: there could not have been any conditional “Soviet Union of the 70s” there. Yes, and the conditional "West" too. What would happen? I can't imagine it. I don't think Sergey Kuznetsov can either.

The writer either doesn't realize this problem or thinks no one will notice. He was not mistaken: almost no one noticed.

Shamil Idiatullin :

A familiar world with eternal division into two camps, ours and not ours. Our highly spiritual, against the war and with an armored train on the siding, not ours - with jeans, soulless movies and music, unemployment and aggressive military. The border between the worlds, built in battles, is, of course, locked, and only merchants and scouts have the key. There is only one difference: ours are alive, not ours are dead. Our deceased becomes an enemy, his relatives become the relatives of the enemy. But how to relate to a normal, like a kid, whose mother did not die, but voluntarily went to the dead? And how can such a kid live on? Very simple: you need to find friends, take a silver knife, and then a couple of pistols with the appropriate bullets, and go ahead through the boundaries, walls, rules, the living, the dead and the foundations of this filthy universe.

The border between the worlds, built in battles, is, of course, locked, and only merchants and scouts have the key. There is only one difference: ours are alive, not ours are dead. Our deceased becomes an enemy, his relatives become the relatives of the enemy. But how to relate to a normal, like a kid, whose mother did not die, but voluntarily went to the dead? And how can such a kid live on? Very simple: you need to find friends, take a silver knife, and then a couple of pistols with the appropriate bullets, and go ahead through the boundaries, walls, rules, the living, the dead and the foundations of this filthy universe.

This is the beginning of the first book by Sergei Kuznetsov, published eight years ago and obviously playing with the cliches of a children's spy novel of the 50s in the style of problematic youthful prose of the same and subsequent years, moreover, the most boring version (Oseeva, Mukhina-Ketlinskaya, Dostyan, etc.). d.). Even the inlays of mystical horror and zombie-post-pop did not knock the narrative off this tone.

A thick trilogy published at the end of last year (under a thousand pages) was nominated for the award. Her second book is a frank, direct quote homage to King, Krapivin, and, suddenly, Lovecraft and Wes Craven. The third focuses on Anglo-American spy thrillers (I did not catch the target bows to Fleming, Le Carre and Child-Preston, but, perhaps, only because of my own little erudition). At the same time, the text is maintained in the same rather dry style, syllable and present o-very long time, which personally puzzled me as a reader no less than the number of typos and clumsiness, surprising for a book published by a respected publishing house (“ Geogriy ”, “ Marina, in her worn jeans, trying to get lost in the crowd ”, “ There was a dining room in the large hall, vacationers came here four times a day—breakfast, lunch, afternoon snack, dinner ”).

Sergey Kuznetsov is known as a skillful pro, deftly using a huge arsenal of tools and techniques. Unfortunately, in The Living and the Dead, he not only limited his choice to a couple of chisels, but also surprisingly accurately selected chisels that were uninteresting and unsympathetic to me personally. In a very short retelling, the trilogy seems like a dream book - at least for a starving teenager with a lack of unprecedented adventures, who crawls in my head and makes me still read and write. This dream has been realized as an endless construct of the second order, which is trying to reveal the dichotomy "alive-dead" in the maximum number of foundations and details of the reality known to us, from the sacralization of a long-standing war to the Tatu ensemble and the exchange of oil for chewing gum - and persists in this intention through one hundred, three hundred and five hundred pages after the most stupid reader in my face understood this, accepted and reconciled. Deliberately infantile characters do not save, dashing with bust plot - all the more so: it is difficult to sympathize with half-cardboard boy-girls who are guaranteed to get out of any hell and who at the same time do not really reflect, even sacrificing a random old man.

Unfortunately, in The Living and the Dead, he not only limited his choice to a couple of chisels, but also surprisingly accurately selected chisels that were uninteresting and unsympathetic to me personally. In a very short retelling, the trilogy seems like a dream book - at least for a starving teenager with a lack of unprecedented adventures, who crawls in my head and makes me still read and write. This dream has been realized as an endless construct of the second order, which is trying to reveal the dichotomy "alive-dead" in the maximum number of foundations and details of the reality known to us, from the sacralization of a long-standing war to the Tatu ensemble and the exchange of oil for chewing gum - and persists in this intention through one hundred, three hundred and five hundred pages after the most stupid reader in my face understood this, accepted and reconciled. Deliberately infantile characters do not save, dashing with bust plot - all the more so: it is difficult to sympathize with half-cardboard boy-girls who are guaranteed to get out of any hell and who at the same time do not really reflect, even sacrificing a random old man.

I read Living and Adults for a long time, painfully, with long breaks, finishing off purely on moral and strong-willed. They were mainly used to curb irritation about the cornerstone (for some reason) for the text of the crooked winks of our reality (the Malbrook cigarettes, the green Croca-Cola soda - “ is something like our Buikal, only tastier than ” , gireliers from Banama and an Italian duo singing about “ happiness is when we are together and I hold your hand ”). I finished reading, impressed by the amount of work done by the author. They are grandiose and in some places obscure the horizons, which, unfortunately, are not easy to call new.

Konstantin Frumkin :

Sergei Kuznetsov set himself an extremely ambitious literary task: to write a novel in the style and in the spirit of Soviet children's and youth novels about "the adventures of young friends." “Alive and Adults” is largely written under Anatoly Aleksin, under Anatoly Rybakov, under “Two Captains”. And most importantly, Sergei Kuznetsov succeeded. First love, children's characters, and of course a strong, strong friendship, a fantastic friendship, purely literary, which even in the text of "Alive and Adults" refers to a literary model - to the musketeers. Note that the literary samples in the spirit of which Kuznetsov writes created a completely false, implausible world - however, the world is ideal for building adventures with likeable characters, and Sergey Kuznetsov took full advantage of these advantages of the chosen style.

And most importantly, Sergei Kuznetsov succeeded. First love, children's characters, and of course a strong, strong friendship, a fantastic friendship, purely literary, which even in the text of "Alive and Adults" refers to a literary model - to the musketeers. Note that the literary samples in the spirit of which Kuznetsov writes created a completely false, implausible world - however, the world is ideal for building adventures with likeable characters, and Sergey Kuznetsov took full advantage of these advantages of the chosen style.

True, the adventures are all scary, so it turned out like Tatyana Koroleva: "Timur and his team and vampires."

Another interesting algorithm used in writing Living and Adults: Kuznetsov takes numerous and well-known circumstances and plots concerning the relationship of the USSR to the capitalist encirclement, and the Soviet population to the bourgeois abroad, and turns them into relations between the world of the living and the world the dead. The whole Soviet history is rewritten from this angle: the revolution took place for the sake of drawing the border between the worlds of the living and the dead, the Great Patriotic War was against the dead, including zombies and vampires, etc. As a device for a small humorous story, this would be extremely witty, but since Kuznetsov describes his Universe within the framework of a huge trilogy and with all the details, too many questions arise. First of all, you note that Kuznetsov made the work of the creator of the universe easier for himself: he doesn’t have to invent anything, he needs to take all the well-known details of Soviet life and simply insert here and there instead of “foreign” - “dead”. Dead goods, dead jeans, dead music.

The whole Soviet history is rewritten from this angle: the revolution took place for the sake of drawing the border between the worlds of the living and the dead, the Great Patriotic War was against the dead, including zombies and vampires, etc. As a device for a small humorous story, this would be extremely witty, but since Kuznetsov describes his Universe within the framework of a huge trilogy and with all the details, too many questions arise. First of all, you note that Kuznetsov made the work of the creator of the universe easier for himself: he doesn’t have to invent anything, he needs to take all the well-known details of Soviet life and simply insert here and there instead of “foreign” - “dead”. Dead goods, dead jeans, dead music.

Too many logical inconsistencies occur. First of all, Kuznetsov requires the reader to forget everything he knew about the reasons why the USSR was bad with goods, and what was the reason for lagging behind Western technology - the explanations given in the novel are completely ridiculous. You begin to wonder where, in fact, the whole foreign country has gone from the world of the living, why all foreign countries are in the world of the dead, and in the world of the living only the USSR, and even Siberia and Yakutistan.

You begin to wonder where, in fact, the whole foreign country has gone from the world of the living, why all foreign countries are in the world of the dead, and in the world of the living only the USSR, and even Siberia and Yakutistan.

If indeed the world of the dead were before our eyes and all people more or less accurately knew their posthumous fate, then the main consequence of this would be that the preparation for death and ensuring their posthumous well-being became the main industry in the world of the living. Moreover, the living do not live long, and the dead are almost immortal, which means that life becomes only a short preparation for a long afterlife. World religions, even without reliable facts about the afterlife, often subordinated the whole life of society to the care of eternity, and if these facts were, then all other tasks would fade into the background.

Finally, Sergei Kuznetsov fails to endure the attitude to the dead as to the dead. After all, if we have dangerous adventures, then we need to kill someone. But how to kill if the dead here they are - quite alive and well? And Kuznetsov is forced to invent the ability to kill the dead, and invents deep worlds where the dead go after the second death. That is, the dead are not actually dead, so why fence the garden?

But how to kill if the dead here they are - quite alive and well? And Kuznetsov is forced to invent the ability to kill the dead, and invents deep worlds where the dead go after the second death. That is, the dead are not actually dead, so why fence the garden?

Without expressing any claims, I would also like to note that “Alive and Adults” are under the rule of a stereotype that generally gravitates over our (and not only our) fantasy, that the most interesting thing worth writing about is the activities of special services and special forces. Every time you rejoice when a Russian science fiction writer does not fall into this well-trodden rut, but not this time.

Still “Alive and Adults” undoubtedly touch upon the theme of understanding the changes that have taken place in the USSR, the theme of the collapse of the USSR, painful and important, our literature has yet to develop a lot of reflections on this topic. However, if you start looking at perestroika and its consequences from the universe of Dirk and Two Captains, then the optics will be somewhat distorted.

All this does not negate the absolute merits of The Living and the Dead: the adventures of its characters are really interesting, the plot is built flawlessly, the language of the novel is simple but accurate, the characters' characters are written out, that's just the volumes - however, epics and sagas are now in vogue.

Debts, bullying, hunger fainting. How Korean kids are preparing to become K-pop stars

British Instagram blogger Evodias went through a rigorous selection process as a child and went to Korea to become a K-pop star - Korean pop music, popular all over the world. She told the BBC what the life of future K-pop stars consists of and why she left this career.

K-pop - is a genre of music that originated in South Korea and combines elements of western electropop, hip-hop, dance music and contemporary R&B. At the beginning of the XXI century, K-pop turned into a large-scale musical subculture with millions of fans, especially among teenagers. The stars of this genre are called "idols" in the country: they usually not only sing, but also act in films and on television and maintain popular blogs.

The stars of this genre are called "idols" in the country: they usually not only sing, but also act in films and on television and maintain popular blogs.

Becoming a K-pop star is not easy: it usually takes years of intense training and sometimes even plastic surgery . But that didn't stop Evodias who, while still a schoolgirl, left her home in northeast England and went to South Korea to become an "idol". BBC journalist Elayne Chong retells her story as she heard it from Evodias herself.

- Korean wave: how K-pop and dramas are taking over Kyrgyzstan

"At that time, K-pop was unknown in Britain. But I, half Chinese, half Korean, watched South Korean dramas such as "Boys Over Flowers and "Naughty Kiss" and fell in love with K-pop and culture in general. While my classmates were crazy about Britney Spears and Backstreet Boys, I listened to Wonder Girls and B2ST.

I had a burning desire to become an actress and perform. In South Korea, one way to do this is to become an "idol", someone who does everything: modeling, acting, singing and dancing... I thought K-pop was the way to my dream.0003

Image copyright Euodias

I've been auditioning for different companies for 10 years. Often it was necessary to send a video of myself: sometimes I skipped school to record, which my mother was very angry about.

And one day when we went to visit my grandmother in Seoul, I went to the casting, which was attended by 2000 people.

We were all gathered in a huge waiting room. You might have seen something similar on Britain's Got Talent, but we didn't have chairs. We sat on the floor in rows of ten.

My turn came after six hours of waiting. My heart was beating very fast as we were called one by one.

Photo by Euodias

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of Story Podcast

When the first girl sang, the judge shouted "Stop! Next!" before she even started singing the chorus. The other girls were treated the same way.

When it was my turn, I gave a monologue from a Korean TV movie. The referee cut me off in the middle. "We are looking for those who sing," he said. - "Will you sing?" I didn't prepare a song, but I decided to try singing "A Whole New World" from Disney's Aladdin.

The judge interrupted me and asked me to dance. I was not ready for this either and felt like an idiot. They turned on the music and I improvised something. After conferring with the assistants, the judge gave me a piece of yellow paper. This meant that I passed to the next stage.

This meant that I passed to the next stage.

I was sent to a room where I was asked to walk along a line on the floor, and my face was photographed from different angles to see how I would look in the frame. A few days later I was asked to come with my parents and discuss the contract.

According to the contract, I had to leave my family and move to South Korea to pursue a career in the company. The company could get rid of me at any time if they thought I wasn't good enough for them. But if I decide to leave my career on my own, I will have to pay the full cost of my education, which is thousands of dollars.

- The dark side of Korean show business

My mother reluctantly signed a two-year contract for me, which was the minimum they could offer. After that meeting, we quarreled, and my mother did not speak to me for a month.

Shortly after I became an apprentice, the company transferred my contract to another firm. Such movements are common, and no one asks for the opinion of the students.

Such movements are common, and no one asks for the opinion of the students.

My new company was harsh. I had to live in her building along with other students who were between the ages of nine and 16. Boys and girls lived separately.

We only left the building to go to school. Korean students went to local public schools, but because I was British, I went to an international one. Apart from school, we were not allowed to go anywhere without permission. But even when we asked permission, we were usually denied.

If parents wanted to visit their children, they had to obtain permission in advance. Relatives who came without warning were not allowed.

image copyrightEuodias

Our usual day went like this: we got up at five in the morning and danced. School started at eight. After school they returned to the company and were engaged in singing and dancing. The students practiced until 11 pm and even later to impress the instructors.

At night we were on our own. We had a tight schedule and they made sure we were all there before locking the doors.

It was forbidden to go on dates, although some people secretly did go. All students were required to act as if they were heterosexual, even if they were not. Anyone who claimed to be gay was kicked out.

Both boys and girls had "managers" - older people who could text us at night to keep an eye on us. If we didn't answer right away, they called and asked where we were.

We didn't have weekends or holidays. On holidays such as the Lunar New Year, the students stayed in the company building while the workers took a break.

Photo by Euodias

The company divided us into two groups, something like Team A and Team B. I was one of 20 or 30 members of Team A - we were considered to have the strongest potential.

Team B had about 200 students. Some of them even paid tuition. They could have been preparing for years and not be sure that they would ever "debut" at all. "Debut" was the moment someone started performing in K-pop.

They could have been preparing for years and not be sure that they would ever "debut" at all. "Debut" was the moment someone started performing in K-pop.

Team A girls lived four people in a room. Ordinary students slept together in a huge room on rugs - right on the floor.

I saw how tired students from Team B slept right in the dance studios after class - the mats there were still the same as in the hostel.

Only once did I see a student from Team B move to Team A. But if a member of Team A behaved badly or complained about something, they could be intimidated by being kicked out or transferred to Team B.

- Star kay Sulli's butt is found dead. She was bullied on social networks

However, usually no one complained. We were all young and ambitious. The company believed that everything we have to go through is part of the discipline training, and this is necessary for the future "idol". We agreed with everything.

We agreed with everything.

We didn't use our own names in the company building, except when talking to other students. We had a number and a stage name, given in accordance with the image that was chosen for us.

I was given the name Dia. But our instructors usually referred to us by the numbers they saw on our shirts. It was wild, like we were participating in some kind of scientific experiment.

I knew that I had the makings of a successful "idol". The company liked me because I was small - the instructors constantly praised me for being petite. Don't get me wrong, I love to eat, but I have a high metabolism and don't gain weight.

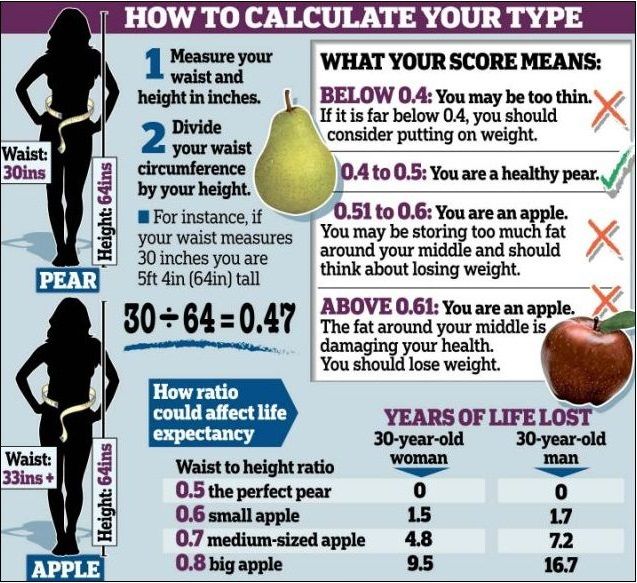

And the weight was an eternal headache for everyone. Each student had to weigh no more than 47 kg, regardless of age and height. At the weekly weigh-in, we were examined by a coach and our weight was announced to the whole room.

If the weight exceeded the established norm, they reduced the diet. Sometimes those who were "overweight" were left without food at all, given only water.

Sometimes those who were "overweight" were left without food at all, given only water.

It all seemed pretty cruel to me, because some of the girls couldn't help it - they were tall.

It was normal to starve yourself. Some had anorexia or bulimia, and many girls did not have their periods. Fainting was common. We often ourselves carried those who lost consciousness to the hostel.

- Another K-pop star found dead. Goo Hara didn't live to be 29 years old

I fainted twice in class, probably from dehydration, though maybe from malnutrition. I woke up in bed and couldn't remember how I got into it.

At some point I realized that I don't have any friends there. They were all colleagues. The environment was too tense and competitive to make friends.

Monthly reviews supported the atmosphere of stress. Each student performed in front of everyone and received marks from the instructors. If the grades were low, the student was immediately kicked out.

If the grades were low, the student was immediately kicked out.

Image copyright Euodias

The streams of newcomers came to replace them. Many of them came after plastic surgery and looked like K-pop stars.

Bullying was common among students. One girl was teased for being overweight. Another, who danced well, had her ballroom shoes stolen.

I missed my old friends back in England, but I couldn't get in touch with them as the instructors told us to hand over our phones so we could focus on class. The company wanted us to look more mysterious before debut and not post anything inappropriate on social media.

We could get our phones for 15 minutes in the evening and I used that time to call my mom. But many students secretly had second phones.

My parents knew that studying was hard, but they couldn't do anything, because I was bound by a contract, and they were very far away. Most of the Korean students didn't tell their parents because they didn't want them to worry.

What helped me was the belief that one day I would debut as a member of a K-pop group. However, the company had seats for less than half of the members of the A-Team. We competed for them through constant examinations.

K-pop groups are usually structured like this: lead vocalist, dancer, rapper, youngest member, and so on. Everyone has a special role.

I was delighted when they first told me that they wanted to choose me as a vocalist. But then the company said that they see me in a different role - visual.

The visual is the face of the group. You are chosen for this role because of your appearance, and especially because of how you are likely to look in the future. Another girl competed for this place with me. She was more attractive than me, but the company thought that if I got plastic surgery, I would be prettier than her and could become a visual.

My face is too large for Korean standards, and they wanted to change my nasal septum and make my jaw smaller.![]() The company could not force me to go for the operation, but it encouraged me in every possible way. Plastic surgery in South Korea is a common thing, and this prospect did not scare me. I looked at it as an investment in my future. The cost of the operation was to be added to my debt to the company.

The company could not force me to go for the operation, but it encouraged me in every possible way. Plastic surgery in South Korea is a common thing, and this prospect did not scare me. I looked at it as an investment in my future. The cost of the operation was to be added to my debt to the company.

My mother did not like this idea. She understood that the operation brought me closer to the dream of becoming an "idol", but she was worried about me.

When the company announced that I had been chosen for the visual role, I was happy. I was told that I would be a K-pop star. You can imagine what that meant to a teenager.

Then I learned more about my future image. Dia, which I would have to become, was supposed to be modest, sweet and innocent. As a visual, I had to become the embodiment of these qualities. But Dia was not me. I am sassy and loud. And I began to doubt whether I could be an obedient girl in public.

I thought that acting would be worth the candle if I became an actress as a result. But when I tried to talk to the company about it, the answer was: "No, we think you're more suitable for a girl group."

But when I tried to talk to the company about it, the answer was: "No, we think you're more suitable for a girl group."

Some of the management told me that since I'm only half Korean, my acting career is only for supporting roles. I felt that my dreams were crumbling.

My contract was just about to expire and needed to be renewed before starting the group. And I said I don't want to.

This was a rare case: most students go to great lengths to realize their dream. But despite my refusal, I parted ways with the company kindly. I fulfilled my obligations under the contract and did not owe anything. If I had stayed and debuted with the group, I would have had to pay for instructors, housing, and plastic surgery. Even successful artists must keep working to pay off the debts that build up during training, as well as the new debts that form when a student becomes an "idol". In general, it is quite difficult for K-pop stars to earn something.

I returned to England with my friends without having the operation. I passed my final exams along with everyone else. Later I studied art and got a place at a fashion school in France. And I was lucky because a lot of K-pop students dropped out at 18 or graduated at 21 and didn't know what to do next. They gave everything for trying to become a K-pop star - and ended up with nothing.

image copyrightEuodias

My mother was happy to have me back. She always considered my training a mistake. But she knew that I had to figure it out myself. And it took a long time before I realized that my mother was right.

When I see videos of the band I was supposed to be in, I feel relieved: thank God I'm not on stage with them. All this seems to me a lie, but I know these girls personally, and the way they behave in public does not at all correspond to what they are in life.

Now I don't think about speaking. If only as a hobby.

-Step-17.jpg/aid1640374-v4-728px-Shuffle-(Dance-Move)-Step-17.jpg)