How did modern dance begin

modern dance | Britannica

Catherine Wheel

See all media

- Key People:

- Martha Graham Isadora Duncan Doris Humphrey Michio Ito Anna Sokolow

- Related Topics:

- eurythmics synchoric orchestra music visualization Ausdruckstanz Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival

See all related content →

Summary

Read a brief summary of this topic

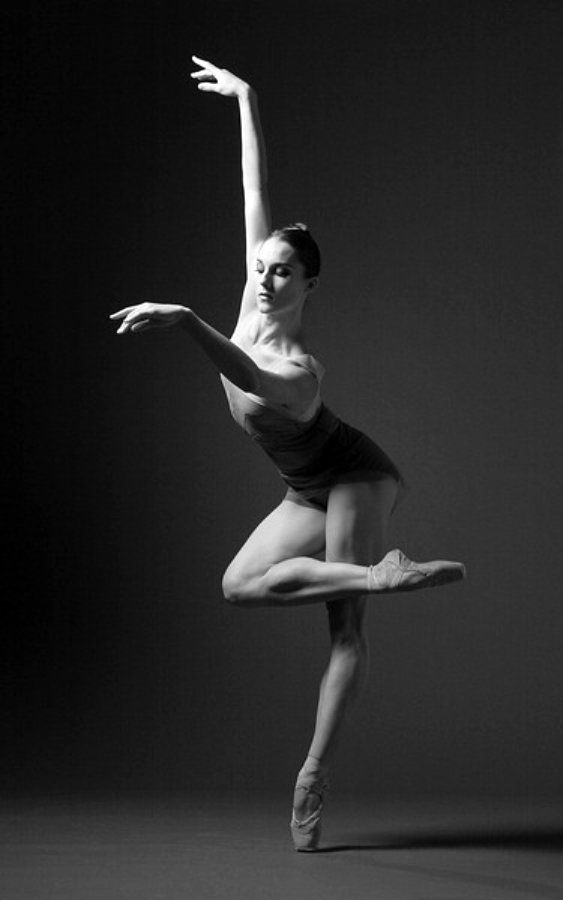

modern dance, theatrical dance that began to develop in the United States and Europe late in the 19th century, receiving its nomenclature and a widespread success in the 20th. It evolved as a protest against both the balletic and the interpretive dance traditions of the time.

The forerunners of modern dance in Europe include Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, proponent of the eurythmics system of musical instruction, and Rudolf Laban, who analyzed and systematized forms of human motion into a system he called Labanotation (for further information, see dance notation). A number of the modern dance movement’s precursors appeared in the work of American women. Loie Fuller, an American actress turned dancer, first gave the free dance artistic status in the United States. Her use of theatrical lighting and transparent lengths of China-silk fabrics at once won her the acclaim of artists as well as general audiences. She preceded other modern dancers in rebelling against any formal technique, in establishing a company, and in making films.

Britannica Quiz

All About Dance Quiz

You might be able to dance well, but can you answer well a few questions about dance? Figure out what you know with this quiz.

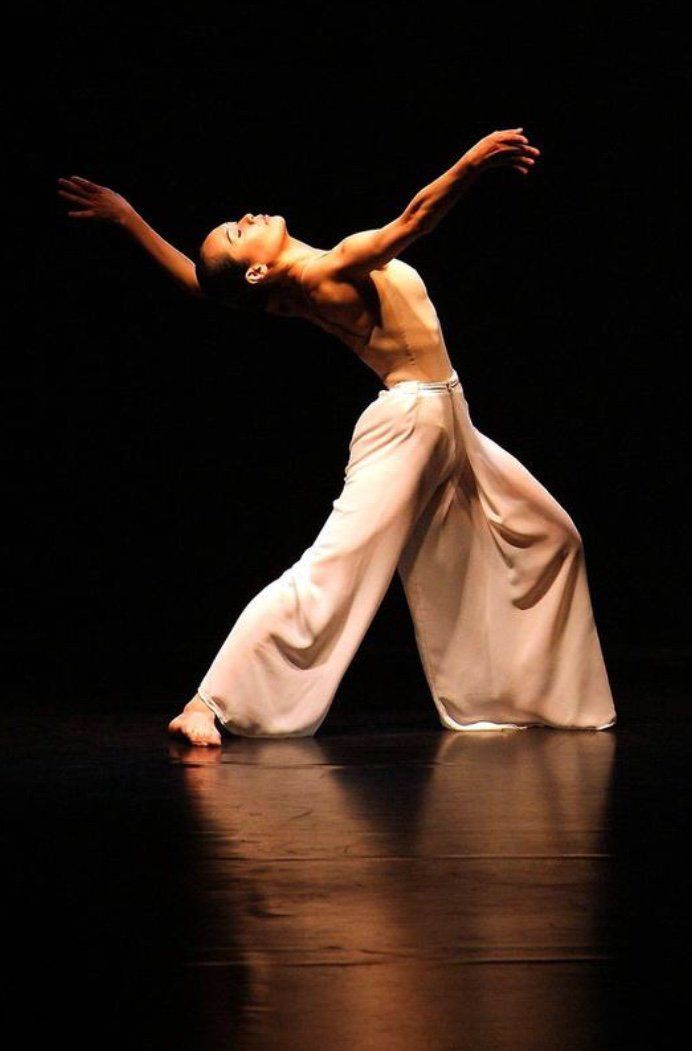

Dance was only part of Fuller’s theatrical effect; for another American dancer, Isadora Duncan, it was the prime resource. Duncan brought a vocabulary of basic movements to heroic and expressive standards. She performed in thin, flowing dresses that left arms and legs bare, bringing a scale to her dancing that had immense theatrical projection. Her revelation of the power of simple movement made an impression on dance that lasted far beyond her death.

Her revelation of the power of simple movement made an impression on dance that lasted far beyond her death.

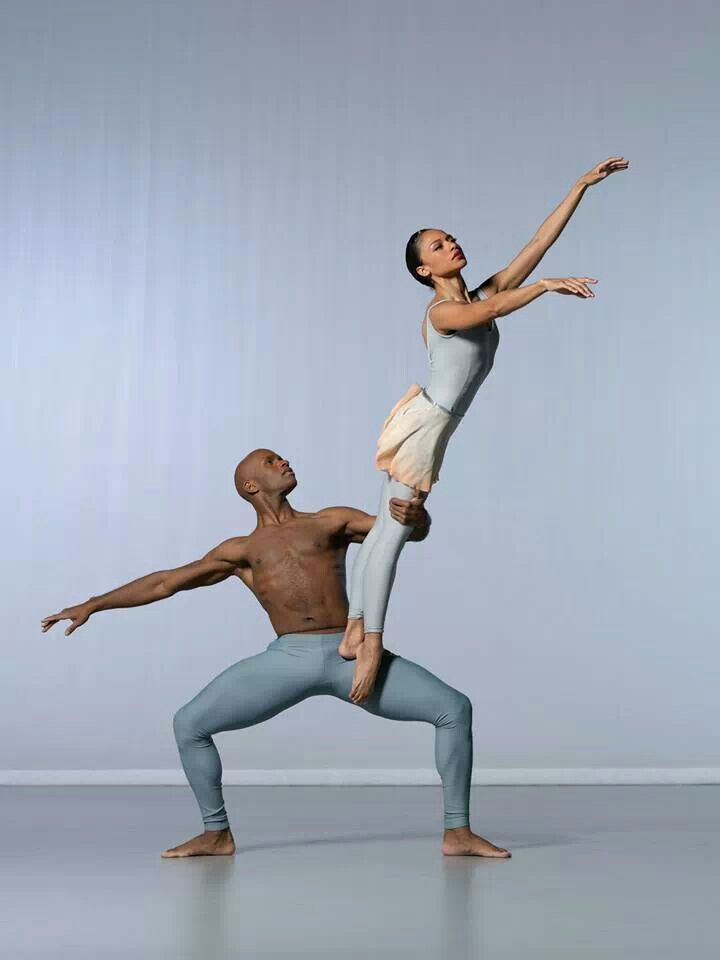

Formal teaching of modern dance was more successfully achieved by Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. St. Denis based much of her work on Eastern dance styles and brought an exotic glamour to her company. Shawn was the first man to join the group, becoming her partner and soon her husband. Nonballetic dance was formally established in 1915, when they founded the Denishawn school.

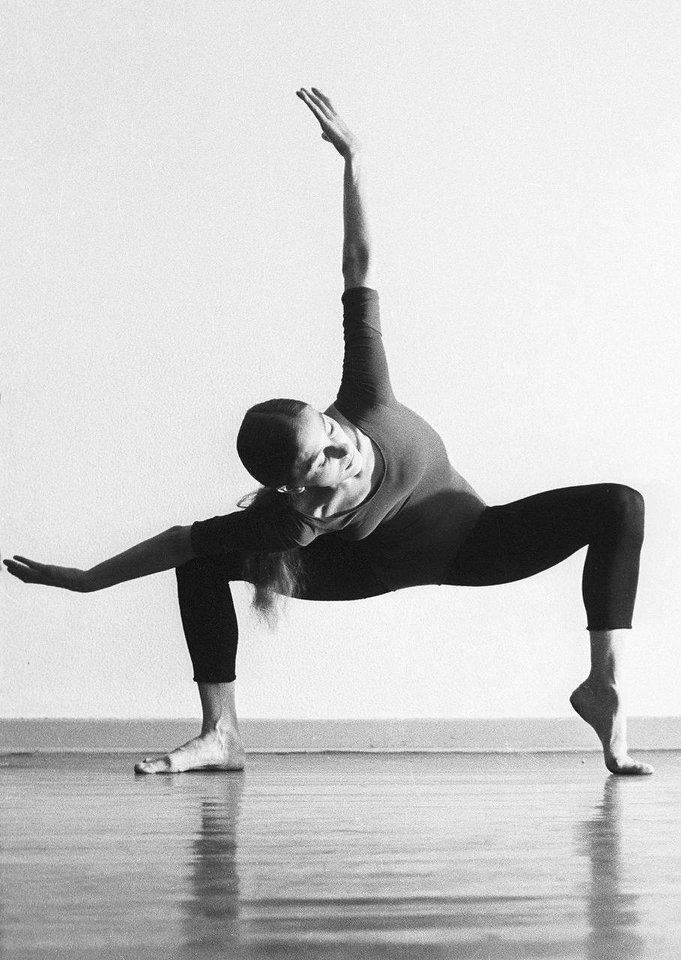

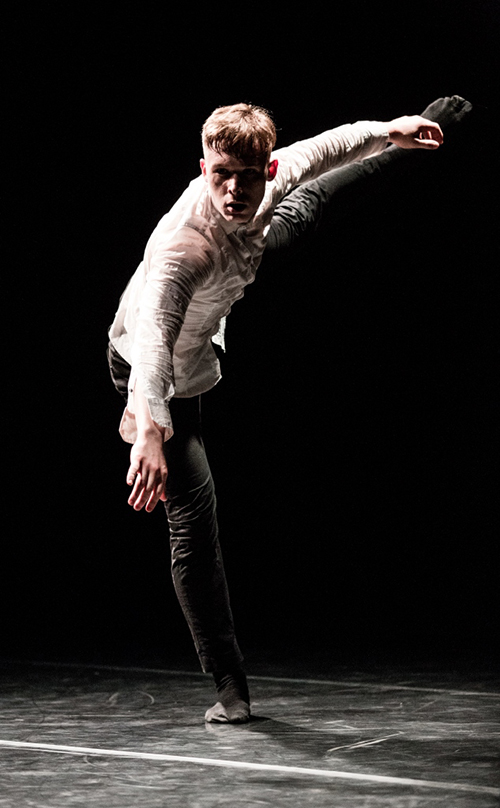

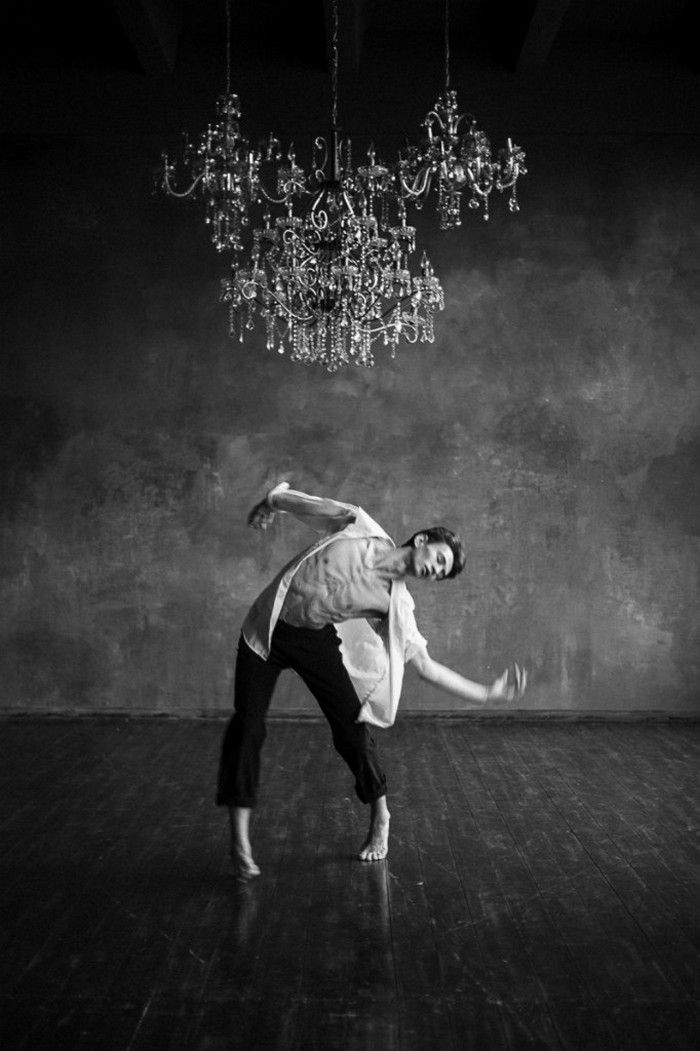

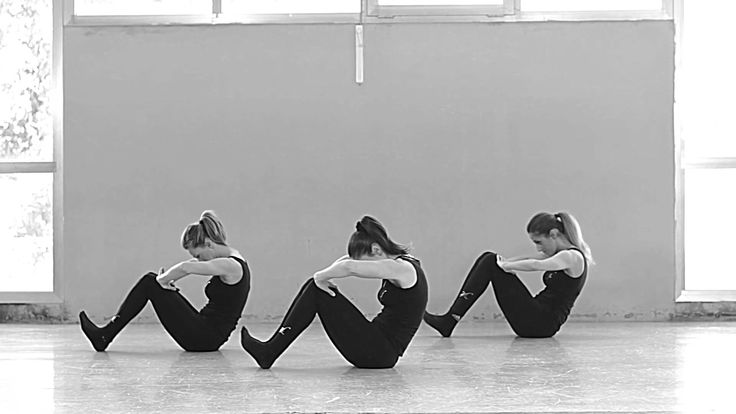

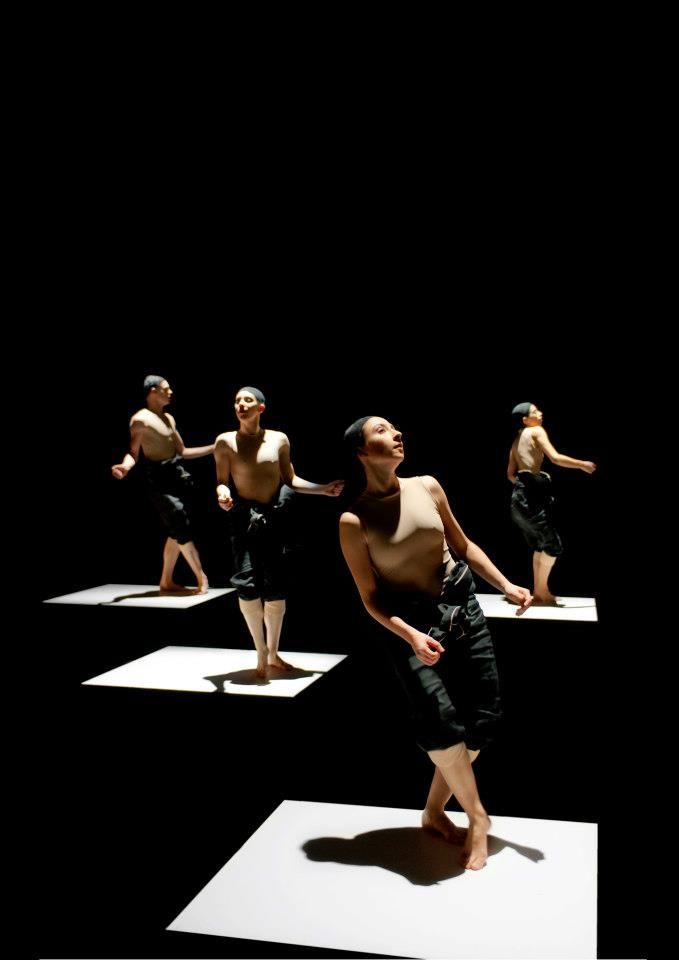

From the ranks of Denishawn members, two women emerged who brought a new seriousness of style and initiated modern dance proper. Doris Humphrey emphasized craftsmanship and structure in choreography, also developing the use of groupings and complexity in ensembles. Martha Graham began to open up fresh elements of emotional expression in dance. Humphrey’s dance technique was based on the principle of fall and recovery, Graham’s on that of contraction and release. At the same time in Germany, Mary Wigman, Hanya Holm, and others were also establishing comparably formal and expressionist styles. As in Duncan’s dancing, the torso and pelvis were employed as the centres of dance movement. Horizontal movement close to the floor became as integral to modern dance as the upright stance is to ballet. In the tense, often intentionally ugly, bent limbs and flat feet of the dancers, modern dance conveyed certain emotions that ballet at that time eschewed. Furthermore, modern dance dealt with immediate and contemporary concerns in contrast to the formal, classical, and often narrative aspects of ballet. It achieved a new expressive intensity and directness.

As in Duncan’s dancing, the torso and pelvis were employed as the centres of dance movement. Horizontal movement close to the floor became as integral to modern dance as the upright stance is to ballet. In the tense, often intentionally ugly, bent limbs and flat feet of the dancers, modern dance conveyed certain emotions that ballet at that time eschewed. Furthermore, modern dance dealt with immediate and contemporary concerns in contrast to the formal, classical, and often narrative aspects of ballet. It achieved a new expressive intensity and directness.

Another influential pioneer of modern dance was dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist Katherine Dunham, who examined and interpreted the dances, rituals, and folklore of the black diaspora in the tropical Americas and the Caribbean. By incorporating authentic regional dance movements and developing a technical system that educated her students mentally as well as physically, she expanded the boundaries of modern dance. Her influence continues to the present day.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

Like Dunham, Trinidadian-born dancer and choreographer Pearl Primus studied anthropology. Her studies led her to Africa (she ultimately took a Ph.D. in African and Caribbean studies), and her choreography explored African, West Indian, and African American themes.

Lester Horton, a male dancer and choreographer who worked during the same period as Dunham and Primus, was inspired by the Native American dance tradition. He was involved in all aspects of the dance, lighting, sets, and so on and also was a noted teacher, whose students included Alvin Ailey, Jr., and Merce Cunningham,

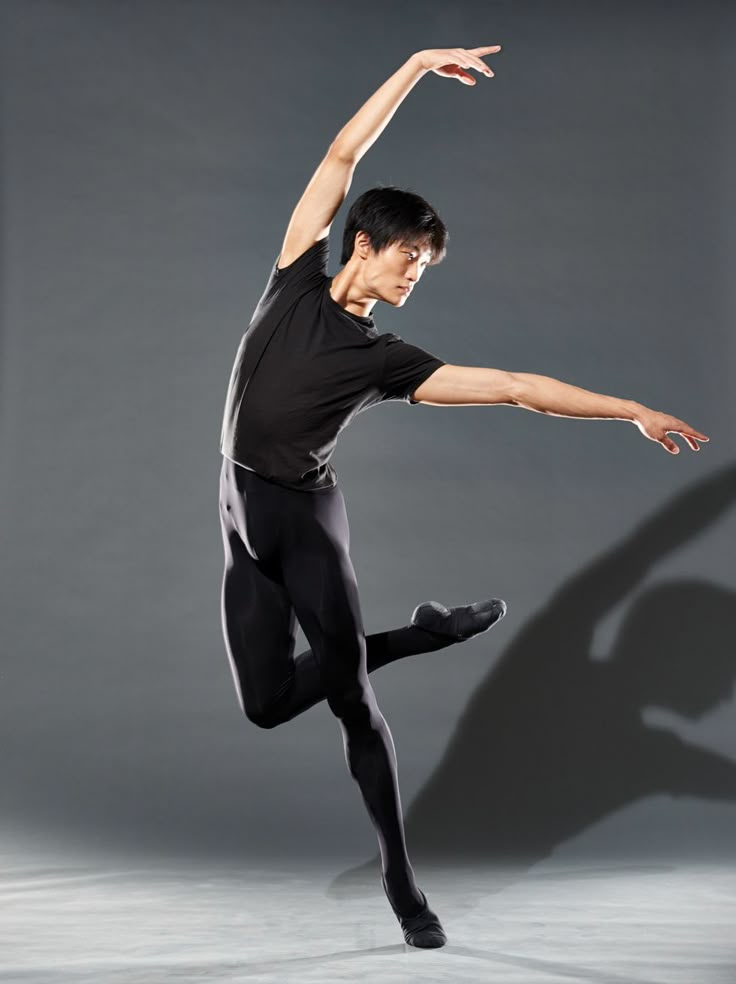

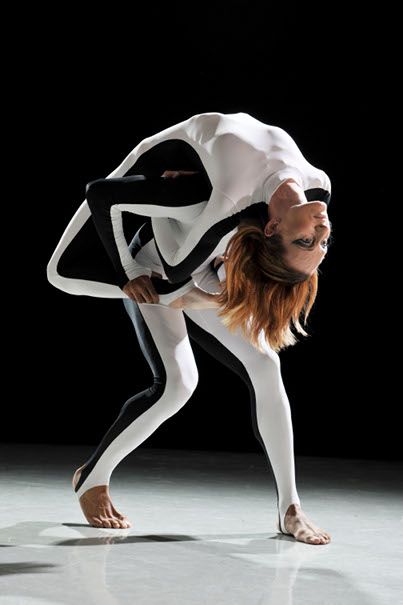

Eventually rejecting psychological and emotional elements present in the choreography of Graham and others, Cunningham developed his own dance technique, which began to incorporate as much ballet as it did modern dance, while his choreographic methods admitted chance as an element of composition and organization. Also in the 1950s Alwin Nikolais began to develop productions in which dance was immersed in effects of lighting, design, and sound, while Paul Taylor achieved a generally vigorous and rhythmic style with great precision and theatrical projection in several works responding to classical scores.

Also in the 1950s Alwin Nikolais began to develop productions in which dance was immersed in effects of lighting, design, and sound, while Paul Taylor achieved a generally vigorous and rhythmic style with great precision and theatrical projection in several works responding to classical scores.

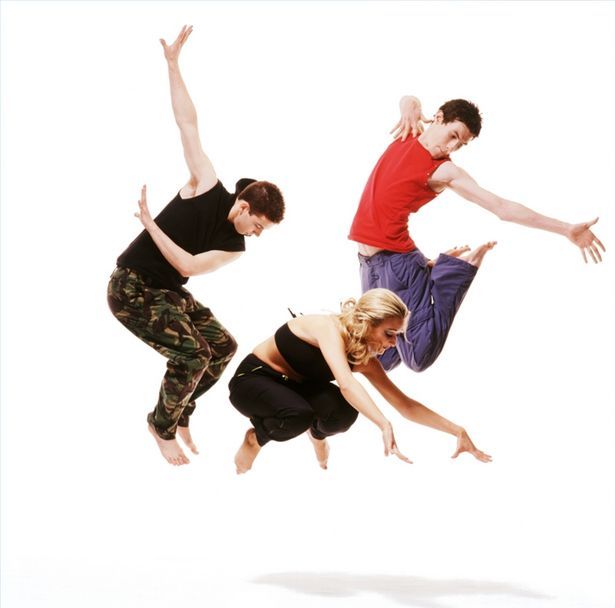

Cunningham was a prime influence on the development of postmodern dance in the 1960s and later. Based especially in New York City, a large number of new dancers and choreographers—Trisha Brown, Yvonne Rainer, Pina Bausch, and many others—began to abandon virtuoso technique, to perform in nontheatre spaces, and to incorporate repetition, improvisation, minimalism, speech or singing, and mixed-media effects, including film. Out of this context emerged artists such as Twyla Tharp, who gradually reintroduced academic virtuosity, rhythm, musicality, and dramatic narrative to her dance style, which was based in ballet and yet related to the improvisatory forms of popular social dance. (See also Tharp’s Sidebar: On Technology and Dance. )

)

Since its founding, modern dance has been redefined many times. Though it clearly is not ballet by any traditional definition, it often incorporates balletic movement; and though it may also refer to any number of additional dance elements (those of folk dancing or ethnic, religious, or social dancing, for example), it may also examine one simple aspect of movement. As modern dance changes in the concepts and practices of new generations of choreographers, the meaning of the term modern dance grows more ambiguous.

This article was most recently revised and updated by Kathleen Kuiper.

|

The Beginnings of Modern Dance

|

|

|

Modern dance was born, of

all places, in San Francisco, the birthplace of the American dancer

Isadora Duncan, a pioneer in the new "free" dance style. |

|

|

Isadora's aim was to

strip ballet of all superfluousness and to express in movement the

essence of life rather than to tell a story through character or

situation. |

|

|

But Isadora Duncan

managed to revolutionize dance in other ways also. Inspired by Greek

art, Isadora shed her toe shoes and tutu in favor of bare feet and

diaphanous, flowing tunics. This subversive act made her the more

notorious, for propriety was of the utmost importance. For more than a

century, ballet dancers' feet had been bound in wooden blocked ballet

slippers that were supposed to be worn two sizes too small to facilitate

the mechanical movement of classical ballet. Furthermore, the ballet

dancer's body was further constricted by a heavily boned corseted

costume that made the human form and its movement appear artificial and

were designed to portray a story-line character. |

|

|

Isadora Duncan also

radically transformed the use of music and choreography in modern dance.

Traditionally, ballet scores were tuneful, piecemeal compositions that

featured waltzes, polkas, pizzicati and polkas. In search of the purest

expression of the soul, Duncan concentrated on the mood piece, from

which movement could grow organically. |

|

|

In December of 1904,

Isadora Duncan first performed in St. |

|

|

To stage his first ballet

in Paris, Diaghilev brought with him the young brilliant choreographer,

Michel Fokine, whose emergence coincided with the Russian Revolution of

1905 and the artistic turmoil that was taking place in the Imperial

Ballet school and theater. As with the state of art all over the western

world, Russian ballet had also become stultified, going through the

motions rather than exploring new artistic territories. |

|

|

Fokine revolutionized

ballet in yet another manner: he abolished the ballerina as being apart

from the corps de ballet. Instead, he was drawn to the crowd and

replicated revolutionary fervor in the fury of the masses, the ecstasy of

race, the triumph of passion, and the liberation of the self through mass

participation. |

|

|

As the principal dancer

of the Ballets Russes, Vaslav Nijinsky was the embodiment of this new

kind of dancer, and he was to become even more controversial when he was

appointed principal choreographer of the Ballets Russes after Fokine

resigned in disgust over Diaghilev's manipulative intrigues. |

|

|

Nijinsky's first ballet

was L'Apres Midi d'un Faune, choreographed in 1912 to the languorous

music of Claude Debussy. |

|

|

But Faune is not

only memorable because of this scandalous incident. This eight minute

ballet broke new ground in that it entirely abandoned classical ballet

technique through Nijinsky's liberation of the foot. The dancers walked

and pivoted, inclined, knelt and, in a single instance, jumped. In other

words, Nijinsky brought ballet back to basic, primitive steps.

Furthermore, Nijinsky patterns movement in this ballet to reflect the

cubists' geometric experimentation. For instance, Nijinsky focused on

the body and its movement as an interplay of triangles, arcs, and lines.

Furthermore, in this ballet Nijinsky presents different views of the

human body simultaneously, just as the cubists compressed in one single

synthetic moment as many different aspects of an object as possible.

This technique was borrowed from both Egyptian hieroglyphs and Greek

friezes which presented frontal and lateral views of the human body in

one frozen moment of time. |

|

|

Nijinsky's choreography

for The Rite of

Spring (1913) generated even more shock waves than Faune. This time,

however, the controversy involved was not sexual explicitness but the

ballet's portrayal of primitiveness and barbarity. The fashionable Belle

poque audience just wasn't ready for this kind of dancing, or rather,

it did not want to be subjected to the human savagery that was about to

be unleashed by World War I. What this audience demanded from a ballet

about spring was a vision of

grace, harmony, and beauty rather than the turbulence just witnessed.

What Nijinsky had submitted to the audience was a ballet that questioned the very notion

of civilization. Instinctively, Nijinsky had anticipated not only what

was to occur in the real world politically but also artistically. He had

captured in this ballet all of the features of revolt: the rejection of

traditional forms, the embrace of primitivism, the emphasis on vitality

rather than rationalism, and the perception of existence as continuous flux. |

|

| The Rite of Spring takes place in ancient Russia, at a time when pre-social tribes would sacrifice a young maiden to the gods in spring to ensure the fertility of the soil and hunting grounds. In other words, Rite focuses on pre-civilized man in a state of nature who is driven by the brutal energy of the continuity of life. This ballet offers no moral judgments; rather, the maiden is seen not as a victim but as someone who chooses to sacrifice herself for the benefit of her community. These were the facts of life as Nijinsky saw them. | |

|

Rite also provoked its

audience in terms of its music and its choreography. Igor Stravinsky

wrote a score that violated every sacred musical tradition: it

lacked melody, harmony and regular rhythm. |

|

History of modern dance. Origins. Fuller, Duncan, Saint-Denis and Allan

The history of modern dance begins with a search for freedom. This seemingly simple desire drives modern choreographers today. Their activity is not just a new form of expression. This is an attempt to rethink dance as an art, to find an alternative approach to movement, ideology and aesthetics. Everything that has been created and is being created in the world of dance is continuously interconnected. Historical context, personal circumstances, location and, sometimes, chance determine the fate of this art form.

The pioneers of the new dance form are 3 American dancers: Loie Fuller (1862-1928), Isadora Duncan (1877-1927) and Ruth Saint-Denis (1879-1968). And also Canadian Maud Allan (1873-1956). At the beginning of the 20th century, it was they who came to the rejection of classical canons and the search for new forms of dance. Their art was dedicated to the emancipation of dance and themselves, as well as true creative exploration. What were the principles of their creativity based on, which are still fundamental in modern dance?

Their art was dedicated to the emancipation of dance and themselves, as well as true creative exploration. What were the principles of their creativity based on, which are still fundamental in modern dance?

Passion for nature

All four choreographers: Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis and Maud Allan had some brief experience with classical dance. For various reasons, they did not find the possibility of artistic expression in it and went in search of their art, drawing inspiration from a variety of sources.

The ballet school taught that the source of movement is in the middle of the back, at the base of the spine. “From this axis,” says the choreographer, “arms, legs and torso should move freely, like a puppet. As a result of this method, we have mechanical movements unworthy of the soul. My ideals made it impossible for me to participate in the ballet, every movement of which shocked me and went against my sense of beauty, its means of expression seemed to me mechanical and vulgar.

A. Duncan

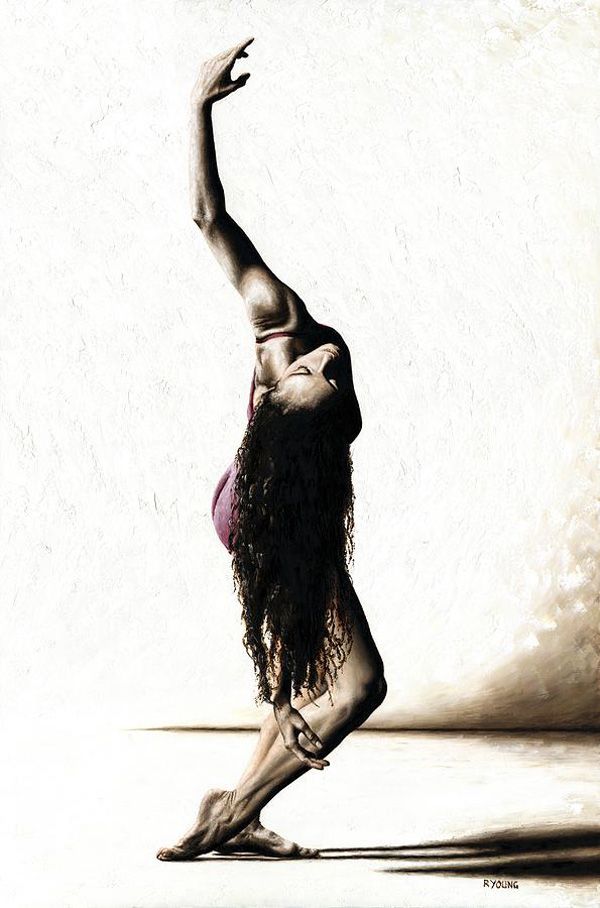

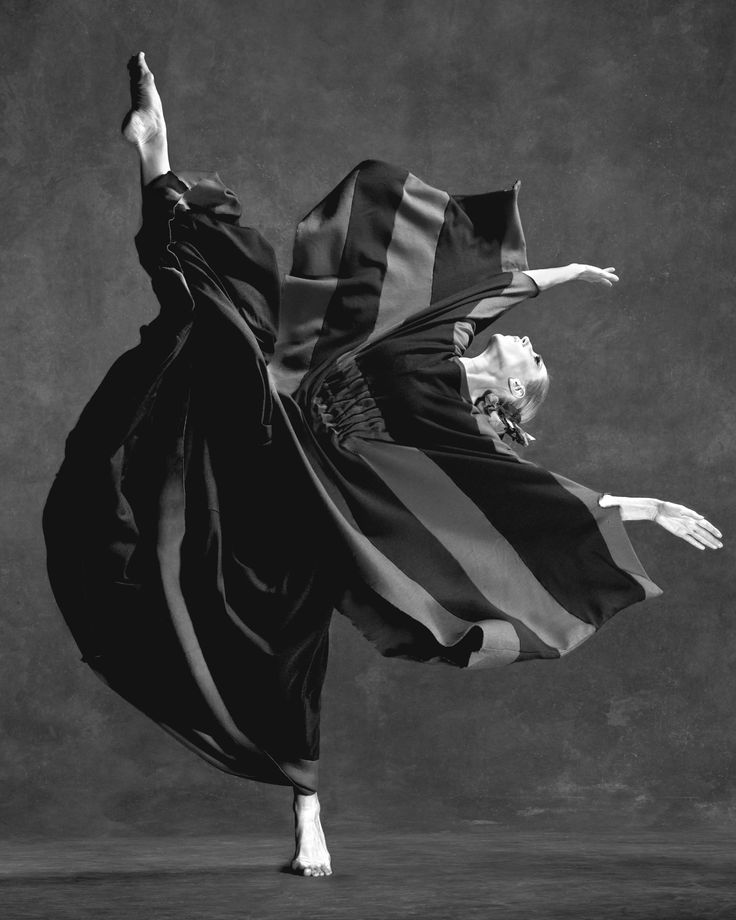

First of all, Fuller, Duncan and Saint-Denis were inspired by nature and were looking for a new form of movement, referring to the harmony of the world order. Unlike ballet, their goal was not to imitate nature, but to reunite with it. Their dance did not imitate a wave, it expressed the strength, power and energy of the sea. They put on costumes that did not interfere with the range of motion, danced barefoot and listened to their intuition. They used a "repertoire of human movements", such as running or walking, as part of the stage choreography.

Isadora Duncan, perhaps the most famous in the post-Soviet space, symbolizes the freedom of a woman and a dancer. She lived a busy and impulsive life, and so did her dancing. Her movements are the result of feelings, emotions and impulses coming from the solar plexus. On the video - the dance of her follower.

Synthesis with other art forms

Choreographers looked for new solutions in areas unfamiliar to them. Duncan turned to the culture of Ancient Greece, and Saint-Denis and Allan - to the East. They believed in the authenticity of these cultures and looked for a natural and unbiased dance. Interestingly, authenticity was not their goal, they did not reconstruct ancient dances, but used images and ideas to form their plastic language.

Duncan turned to the culture of Ancient Greece, and Saint-Denis and Allan - to the East. They believed in the authenticity of these cultures and looked for a natural and unbiased dance. Interestingly, authenticity was not their goal, they did not reconstruct ancient dances, but used images and ideas to form their plastic language.

I worked studying ancient sculpture, vase painting and individual moments of ancient dance recorded in painting and sculpture, but I saw in them only unsurpassed examples of natural and beautiful human movements. My dance is not the dance of the past, it is the dance of the future. And what was the dance of the ancient Greeks in general - we do not know. Their music, apparently, was primitive.

A. Duncan

One of Fuller's inventions and innovations was the play with light. She invented and patented special placement of mirrors, chemical dyes for textiles and special lighting. Fuller may have been the first choreographer to embrace dance as a visual art. The progressive creativity of these women aroused interest and admiration among contemporaries. Many artists, musicians and stage designers collaborated with choreographers. Here, for example, is the dance of Loi Fuller, captured by the Lumiere brothers in 1896 d.

The progressive creativity of these women aroused interest and admiration among contemporaries. Many artists, musicians and stage designers collaborated with choreographers. Here, for example, is the dance of Loi Fuller, captured by the Lumiere brothers in 1896 d.

Rejection of plot

Another revolutionary innovation is plotlessness. This idea, which was clearly reflected in painting (cubism, abstract art, etc.), was also adapted into dance. The choreographers considered the expression quite interesting and self-sufficient motive. Fuller and Duncan turned to human emotions and natural processes as the composition of a choreographic plot, and Saint-Denis developed a method of visualizing music through dance - where the structure of the musical work was the basis for the choreography. This method helped to avoid emotional interpretation and additional plot, proving that dance can exist as an independent form of expression, as opposed to ballet, where each movement is tied to the actions and emotions of the character. The video captures excerpts from the dances of Saint-Denis, inspired by India and China.

Basis for development - schools and the festival

As a separate discipline, modern dance has established itself because Fuller, Duncan and Saint-Denis have developed educational systems. Just as in ballet Louis XIV founded the Royal Academy of Dance, these women founded the first schools of free dance in France, Russia and the United States - with their own system of education, ideology and tasks. In these schools, teachers helped children find their form of expression in dance. If in ballet the system is aimed at improving technique and the body to match the accepted canons, here the focus was on the individuality and ability of the dancer for artistic interpretation. At the same time, all three schools were trying to structure their method, develop the basic techniques of Fuller, Duncan, Saint-Denis and teach it to the next generation.

It was easy for schools to find pupils, because the whole world was on the threshold of change, and young people liked the idea of democracy, including in dance. They wanted to find themselves, a new form of self-expression and freedom. Soon the students began to participate in productions and tour under the brand of their mentors. So, for example, the Isadorables troupe appeared, consisting of Duncan's students and performing in Europe and the USA after the death of the choreographer.

Famous School Denishawn , founded by Saint-Denis and her partner Ted Schon in Los Angeles, nurtured Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman, the main figures of modern dance in the US, whose work is still on the world's main stages. Interestingly, in this school, ballet was not excluded as a discipline, but adjusted to their philosophy, practicing it barefoot or in nature. The school also taught yoga, free flow (today we would call this class improvisation), folk dancing, Dalcroze rhythmic gymnastics, meditation, and arts and crafts. Here is an excerpt from the Denishawn School's choreographic education manual that describes the school's philosophy exactly:

The art of dance is too broad to be limited to just one system. On the contrary, the dance itself includes all systems or schools. Any way in which a person of any race or nationality, in any period of human history, has expressed his feelings with a rhythmic movement belongs to the dance. We are trying to understand and use all the knowledge from the past about dance and will continue to use new discoveries in the future.

In 1940 this pair together with Mary Washington Ball , the dance teacher who owned the premises at the time, hosted a festival at Jacob's Pillow . From the first days, the program consisted of a variety of types of dance: from ballroom to folk. And thus showed that this art has no boundaries. Today Jacob's Pillow is a dance center, school and theater. The organization honorably holds the title of the very first international dance festival in the United States and puts on more than 200 performances every summer. In 2010, Jacob's Pillow was awarded the National Gold Medal for the Arts.

Unfortunately, the difficult years of the First and Second World Wars did not allow schools to exist for a long time. But the foundation for the development of modern dance was laid. A new generation of dancers and choreographers appeared who continued the ideas of mentors in their work.

From the very first days, modern dance has established itself as free - where each artist has his own truth and his own dance. Fuller, Duncan and Saint-Denis not only made an ideological breakthrough that inspired thousands of choreographers around the world, but also left an institutional legacy in the form of the first schools and festivals of modern dance. Not all of their activities have been documented and preserved, but most importantly, they have been transferred into the bodies and practices of other dancers. And this is the main archive of the dance.

Not all of their activities have been documented and preserved, but most importantly, they have been transferred into the bodies and practices of other dancers. And this is the main archive of the dance.

| Home / Articles / Dance History / The history of the development of modern dance |

| Maria Pavlik, Dmitry Grebenshchikov, Georgy Meshcheryakov Ruth Saint Denis: I see the Dance as a way of communication between soul and soul, through the expression of everything that is very deep, very subtle to convey in words.Modern dance is one of the directions of modern foreign choreography, which originated in the late XIX - early XX centuries in the USA and Germany. The term "Modern dance" originated in the US to describe stage choreography that rejects traditional ballet forms. Having come into use, it supplanted other terms (“free dance”, “Duncanism”, “sandal dance”, “rhythmoplastic dance”, “expressive”, “expressionistic”, “absolute”, “new artistic”) that arose in the process of development this direction. For each representative of modern dance, the main form was not, it was important to convey to the viewer a certain meaning, experience, emotions. Unlike jazz or classical dance, this direction, like no other, is associated with the names of its performers and choreographers, since it was created on the basis of the creativity of a particular person. The ideas of modern dance were anticipated back in 1830 by the famous French teacher and stage movement theorist Francois Delsarte, who studied the connection between voice, gesture and emotion. He argued that only a gesture freed from conventionality and stylization (including musical) is capable of truthfully conveying all the nuances of human experiences. By the way, one of Delsarte's students was Geneviève Steban, who later taught at Isadora Duncan's courses. Isadora Duncan (1878-1927), contrary to popular belief, did not create a complete school, although she opened the way for something new in choreographic art. Duncan considered nature as a source of inspiration. "When I dance barefoot on the ground, I do Greek postures, because Greek postures are exactly the natural positions on our planet." Improvisation, the rejection of the traditional ballet costume, the appeal to symphonic and chamber music, simple stage scenery - all these fundamental innovations by Duncan predetermined the path of modern dance. Unlike Duncan, Frenchwoman Loie Fuller, in search of new forms of dance, was carried away by the expressiveness of the movement of her arms and body. Using bright fabrics, light, she created images of butterflies and flames. Perhaps it was Fuller who became the ancestor of a new direction - the "dance show". In the 20th century, Europeans Rudolf Steiner (Switzerland), Emile Jacques Dalcroze (Switzerland) and Rudolf von Laban (Austria) made a significant contribution to the development of modernity, who developed the foundations of “eurythmy”, “eurythmics” and “expressive dance”, respectively. With the advent of the first works of modern theorists, their ideas were picked up by practitioners. Kurt Joss tried to combine expressiveness, classical dance and pantomime. Mary Wigman explored emotions - she tried to convey fear, despair, pain, etc. in dance. Wigman's ideas were widely disseminated in the United States thanks to the further search for her students. So, for example, Gret Palucca introduced the technique of high jumps into modernity, Martha Graham developed the technique of “effort” and “relaxation” (“contraction” and “release”), which is now accepted all over the world. The pillars of foreign modernity are: Honey Holm, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman. It was these people who laid the foundation for modern modernity, created the basic concepts and provisions. Two American dancers and choreographers Ruth St. Denis (1878-1968) and Tad Shawn (1891-1972) also played a huge role in the development of modern dance. Thanks to them, in 1915 the first school of modern dance "Danyshawn" (Danyshawn Company) was opened, the name of which for many years became a symbol of professional modern dance. In the 1950s, the first echoes of postmodernity appeared, whose representatives, having abandoned the experience of previous generations, plunged headlong into experimentation (Paul Taylor, Alvin Nikolais, Trisha Brown, Meredith Monk, William Forsyth). Many of them denied the usual stage space and transferred their performances to the streets, rooftops and parks, denying the form of the performance, involving the viewer in the theatrical performance (“happening”). The attitude towards costumes, music and other components of theatrical action has changed. Many choreographers have completely abandoned musical accompaniment and used only percussion instruments or noises. At the same time, contact improvisation appeared, initiated by Steve Paxton. The spiritual "father" of the choreographic avant-garde was undoubtedly the American dancer Merce Cunningham. He believed that contemporary dance relies too much on individuals and borrows too much from literature. Working closely throughout his creative life with the composer John Cage, he transferred many of the ideas of this composer to his performances, built on the "theory of chance", deciding which structure of the dance to choose, using lots, for example, dice. Buto, which originated in Japan in the 1950s, also belongs to the avant-garde form of dance. She was inspired by Ono Kazuo, Kasai Akira, and Hijikata Tatsumi. At that time, young Japanese choreographers were strongly influenced by European surrealism and American avant-garde, returning again and again to artistic "happenings". One of those who continued the tradition of the previous generation was José Limón (1908-1972). From 1928 he studied modern dance with Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman. In 1945 he formed the Limon Dance Company and directed it with Doris Humphrey until 1958. Many of his productions are epic and monumental. There are also modern dance troupes in other countries of the world: Dance Ensemble of I.Kramer (Sweden), Netherlands Dance Theatre, Pécs Ballet (Hungary), Batsheva and Inbal (Israel), Dance Troupe of the Cultural Arts Center (Philippines) ) and others. Modern also became widely known in Argentina, Brazil, Guatemala, Colombia. Cuba has developed its own modernist school. Interest in modern dance is also growing in countries with a long tradition of classical dance. In 1967, the largest center in the region for the study of modern dance was organized in London, at which a school and a troupe were created - the London Modern Dance Theater (under the direction of R. Cohen). In 1972, Joseph Roussillo creates the troupe Ballet Theater in France. The French dance theater uses American and German modern dance techniques, movement as a language of emotions, a mirror of the dancer's inner world. With an increase in the audience, the directors use the means of dance scenography (accessories, crowded space). In Russia, modern dance appeared relatively recently, but quickly won its fans. Among them: Smirnov (Yekaterinburg), Sviridova (St. Petersburg), dance studio "Diana" (Kurgan), modern dance studio "Free Movement" (St. Petersburg), etc. Each of the teachers tries to convey to students and spectators not only their thoughts, but also to create a new direction of modernity - “Russian modernity”. |

Perhaps this is

a fitting place for modern dance to have originated since the life-style

of the California frontier at that time was primitive, simple, free and

natural, the hallmarks of the new style. It was life in the midst of

this self-invented, ever-evolving society that shaped Isadora into a

redeemer who saw herself as a liberating force from all sorts of

conventions and constrictions, whether moral, social, sexual or

artistic, that obstructed free expression of one's feelings. And so,

Isadora decided that she was going to revitalize what she thought was a

moribund art, dulled by mechanical frippery. An intuitive rebel against formal

ballet training, Isadora was artistically weaned on the fluidity of

nature, especially the ebb and flow of the waves by the seashore. It was

from nature's rhythmic impulses and decorative, sinewy forms that she

shaped her undulating movement.

Perhaps this is

a fitting place for modern dance to have originated since the life-style

of the California frontier at that time was primitive, simple, free and

natural, the hallmarks of the new style. It was life in the midst of

this self-invented, ever-evolving society that shaped Isadora into a

redeemer who saw herself as a liberating force from all sorts of

conventions and constrictions, whether moral, social, sexual or

artistic, that obstructed free expression of one's feelings. And so,

Isadora decided that she was going to revitalize what she thought was a

moribund art, dulled by mechanical frippery. An intuitive rebel against formal

ballet training, Isadora was artistically weaned on the fluidity of

nature, especially the ebb and flow of the waves by the seashore. It was

from nature's rhythmic impulses and decorative, sinewy forms that she

shaped her undulating movement. In order to accomplish this, she rebelled against the

prevalent artistic conventions of her day which she thought rendered

dancing contorted, inexpressive and artificial. At the time, classical

ballet was based on the principles that all movement emanated from the

spine and that dance needed to defy gravity. For Isadora, however, all

movement originated from the solar plexus region of the body, the center

of feeling which could be activated by an idea or an emotion: "Working

much like a motor does--in progressive development--a single movement

from an initial impetus gradually follows a rising curve of inspiration,

up to those gestures that exteriorize the fullness of feeling, spreading

ever under the impulse that has swayed the dancer." Furthermore, Isadora

felt that the body had to move naturally rather than resist the law of

gravity, for movements not corresponding to the basic function and

design of the human form were unnatural.

In order to accomplish this, she rebelled against the

prevalent artistic conventions of her day which she thought rendered

dancing contorted, inexpressive and artificial. At the time, classical

ballet was based on the principles that all movement emanated from the

spine and that dance needed to defy gravity. For Isadora, however, all

movement originated from the solar plexus region of the body, the center

of feeling which could be activated by an idea or an emotion: "Working

much like a motor does--in progressive development--a single movement

from an initial impetus gradually follows a rising curve of inspiration,

up to those gestures that exteriorize the fullness of feeling, spreading

ever under the impulse that has swayed the dancer." Furthermore, Isadora

felt that the body had to move naturally rather than resist the law of

gravity, for movements not corresponding to the basic function and

design of the human form were unnatural. For her, true dance sprang from

the undulations of the body's rhythms sympathetic to the organic rhythms

of the universal energies of the world. In other words, Isadora Duncan

wanted to express the rhythm of the spirit that permeates all life.

For her, true dance sprang from

the undulations of the body's rhythms sympathetic to the organic rhythms

of the universal energies of the world. In other words, Isadora Duncan

wanted to express the rhythm of the spirit that permeates all life. In trying to heighten

the expressiveness of the human body, Isadora adopted the chiton, the

Greek one-piece tunic favored by the sculptors of the classical age. As

worn by Isadora, the chiton could be softly bloused by belt or cord

around the waist and crisscrossed between the breast. Several slits

extending from below the hip allowed for free pelvic and leg movements.

Needless to say, Isadora Duncan was slammed with several lawsuits

assailing her for her indecent exposure, but managed, at the same time,

to inspire the Parisian world of haute couture, and fashion would never

be the same.

In trying to heighten

the expressiveness of the human body, Isadora adopted the chiton, the

Greek one-piece tunic favored by the sculptors of the classical age. As

worn by Isadora, the chiton could be softly bloused by belt or cord

around the waist and crisscrossed between the breast. Several slits

extending from below the hip allowed for free pelvic and leg movements.

Needless to say, Isadora Duncan was slammed with several lawsuits

assailing her for her indecent exposure, but managed, at the same time,

to inspire the Parisian world of haute couture, and fashion would never

be the same. For Isadora, the perfect dance

was unaccompanied dance, a self-sufficient expression independent from

all musical support. Such a dance would have the dancer moving in accord

with her own bodily rhythms, in dialogue only with an inner voice--no

music, no text. It would be pure dancing for oneself to the "rhythms of

some invisible music," not interpreting but creating expression and

taking place in privacy. And so, the function of music is the

inspirational element that brings high excitement and full realization

to a dancer's artistic powers. In other words, music provides the dancer

with emotional and physical energies. At no time did Isadora see music

as the means of creating dances but as a nourishment

of the soul. And thus she turned to the finest music of the master

composers-- Chopin, Bach, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Gluck and

Beethoven--performed as simple piano accompaniment.

For Isadora, the perfect dance

was unaccompanied dance, a self-sufficient expression independent from

all musical support. Such a dance would have the dancer moving in accord

with her own bodily rhythms, in dialogue only with an inner voice--no

music, no text. It would be pure dancing for oneself to the "rhythms of

some invisible music," not interpreting but creating expression and

taking place in privacy. And so, the function of music is the

inspirational element that brings high excitement and full realization

to a dancer's artistic powers. In other words, music provides the dancer

with emotional and physical energies. At no time did Isadora see music

as the means of creating dances but as a nourishment

of the soul. And thus she turned to the finest music of the master

composers-- Chopin, Bach, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Gluck and

Beethoven--performed as simple piano accompaniment. Petersburg, and then returned in

1905, 1907 and 1909. These visits were to inspire two of the most

important players who would transform modern ballet: Sergei Diaghilev

and Michel Fokine. Sergei Diaghilev was a young Russian aristocrat who

at the time was a profound influence of Russian cultural life by

publishing an art periodical and mounting a massive exhibition of

historical portraits in St. Petersburg. As a reward for Diaghilev having

revealed Russia to herself, the Czar made it possible for Diaghilev to

obtain further support for several exhibits in Paris that would export

Russian art to the West--first, with an exhibition of Russian painting

(1906), concerts of Russian music (1907) and the first production

outside of Russia of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov. This production was a

soaring success due to its authenticity and extravagant costumes and

settings. For the following Paris season, Diaghilev decided to take a

dance program also since ballet had almost died in the west and would

therefore be a novelty.

Petersburg, and then returned in

1905, 1907 and 1909. These visits were to inspire two of the most

important players who would transform modern ballet: Sergei Diaghilev

and Michel Fokine. Sergei Diaghilev was a young Russian aristocrat who

at the time was a profound influence of Russian cultural life by

publishing an art periodical and mounting a massive exhibition of

historical portraits in St. Petersburg. As a reward for Diaghilev having

revealed Russia to herself, the Czar made it possible for Diaghilev to

obtain further support for several exhibits in Paris that would export

Russian art to the West--first, with an exhibition of Russian painting

(1906), concerts of Russian music (1907) and the first production

outside of Russia of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov. This production was a

soaring success due to its authenticity and extravagant costumes and

settings. For the following Paris season, Diaghilev decided to take a

dance program also since ballet had almost died in the west and would

therefore be a novelty. To his surprise, Diaghilev discovered that it

was ballet that gave him the opportunity to combine many of his loved

artistic disciplines--choreography, drama, painting and music--with his

taste, fondness for experiment, and patronage of artists. And so,

Diaghilev founded the Ballets Russes, a company of Russian

dancers and choreographers residing in Paris which transformed the

worlds of dance, music, art, theater, and fashion.

To his surprise, Diaghilev discovered that it

was ballet that gave him the opportunity to combine many of his loved

artistic disciplines--choreography, drama, painting and music--with his

taste, fondness for experiment, and patronage of artists. And so,

Diaghilev founded the Ballets Russes, a company of Russian

dancers and choreographers residing in Paris which transformed the

worlds of dance, music, art, theater, and fashion. Everyone

connected with ballet felt that Fokine was part of the birth of a new

form of ballet. He became well-known for his call for authenticity and

realism: that art must represent its race, historical moment and its

cultural environment and that it belonged to the masses. Fokine was

credited with revitalizing ballet by incorporating into it national and

ethnic styles of movement by drawing on living sources and the remains

of lost civilizations. Basically, Fokine worked as an ethnographer and

in his task he was helped by the designer Leon Bakst, who helped him

with the particulars of the historical reconstruction of time and place.

Everyone

connected with ballet felt that Fokine was part of the birth of a new

form of ballet. He became well-known for his call for authenticity and

realism: that art must represent its race, historical moment and its

cultural environment and that it belonged to the masses. Fokine was

credited with revitalizing ballet by incorporating into it national and

ethnic styles of movement by drawing on living sources and the remains

of lost civilizations. Basically, Fokine worked as an ethnographer and

in his task he was helped by the designer Leon Bakst, who helped him

with the particulars of the historical reconstruction of time and place. Above all, Fokine wanted to create the illusion that his

ballets were not choreographed at all but that they surged spontaneously

from a swelling of emotion and gaiety. In essence, he gave ballet the

look of improvisation. Before Fokine, ballet was too "staged" and

artificially mannered. But with the entrance of Fokine into the Russian Imperial

Ballet, dancers became humanized, individualized conveyors of emotional

and psychological truths. Fokine personified the need for dancing and

gesture to be dramatically motivated. Above all, Fokine asserted that

man can and should be expressive from head to foot.

Above all, Fokine wanted to create the illusion that his

ballets were not choreographed at all but that they surged spontaneously

from a swelling of emotion and gaiety. In essence, he gave ballet the

look of improvisation. Before Fokine, ballet was too "staged" and

artificially mannered. But with the entrance of Fokine into the Russian Imperial

Ballet, dancers became humanized, individualized conveyors of emotional

and psychological truths. Fokine personified the need for dancing and

gesture to be dramatically motivated. Above all, Fokine asserted that

man can and should be expressive from head to foot. This

resignation and ascension took place not only because Diaghilev and

Nijinsky were lovers but because Diaghilev instinctively knew that if

his ballet company was to remain on the cutting edge, it needed new

leadership to make the transition. Whereas Fokine's artistic creativity

had explored the outward forces that shape man, Nijinsky's art focused

on the inward forces that drive him. In other words, Nijinsky's

choreography gave expression to the forbidden unconscious and primitive

energies within the individual whose portrayal had been heretofore

taboo. By taking this enormous artistic risk, Nijinsky's legacy is as

seminal as Picasso's, Stravinsky's, and Freud's.

This

resignation and ascension took place not only because Diaghilev and

Nijinsky were lovers but because Diaghilev instinctively knew that if

his ballet company was to remain on the cutting edge, it needed new

leadership to make the transition. Whereas Fokine's artistic creativity

had explored the outward forces that shape man, Nijinsky's art focused

on the inward forces that drive him. In other words, Nijinsky's

choreography gave expression to the forbidden unconscious and primitive

energies within the individual whose portrayal had been heretofore

taboo. By taking this enormous artistic risk, Nijinsky's legacy is as

seminal as Picasso's, Stravinsky's, and Freud's. In this ballet, a faun, half-human/half-beast,

sees seven nymphs, and he is attracted to one of them in particular.

When she undresses to bathe, he tries to catch her and fails. Running

away from the faun, the nymph drops her scarf and he picks it up. The

faun then returns to his rock on which he was lying at the beginning of

the ballet, lies down on the scarf and then makes love to it to the point of

orgasm. When Nijinsky literally masturbated during the first

performance, all of Paris was aghast at his publicly committing such an offensive

act. But Nijinsky had been merely swept away by the unconscious

forces that would soon be released in real life, for the dancer was a

latent heterosexual who would eventually marry Romala de Pulzsky. Dance,

for Nijinsky, became the means through which his inner self, no matter

how ambiguous and unrestrained, could find expression. The audience,

however, was

not yet ready to accept such exhibitionism and self indulgence presented

so openly on the stage.

In this ballet, a faun, half-human/half-beast,

sees seven nymphs, and he is attracted to one of them in particular.

When she undresses to bathe, he tries to catch her and fails. Running

away from the faun, the nymph drops her scarf and he picks it up. The

faun then returns to his rock on which he was lying at the beginning of

the ballet, lies down on the scarf and then makes love to it to the point of

orgasm. When Nijinsky literally masturbated during the first

performance, all of Paris was aghast at his publicly committing such an offensive

act. But Nijinsky had been merely swept away by the unconscious

forces that would soon be released in real life, for the dancer was a

latent heterosexual who would eventually marry Romala de Pulzsky. Dance,

for Nijinsky, became the means through which his inner self, no matter

how ambiguous and unrestrained, could find expression. The audience,

however, was

not yet ready to accept such exhibitionism and self indulgence presented

so openly on the stage. For Nijinsky, however, it was a matter of

catharsis.

For Nijinsky, however, it was a matter of

catharsis.

Furthermore, the musical

score was very loud. The orchestra called for was immense, with a high

percentage of it being percussion. The sounds produced by the woodwinds

were distorted through the use of mutes, and the violins played down-bow

in order to create a louder, more dissonant sound. Nijinsky's

choreography was as jarring as the music. Every classical traditional

movement was eliminated: no jets, pirouettes, or arabesques. Movement

was reduced to jumping with both feet and walking in a stomping fashion.

The basic position of the dancers consisted of hunching towards the

ground, feet turned inward with great exaggeration, knees bent, arms

tucked in, and head turned in profile as the body faced forward. In

other words, the dancers appeared knock-kneed so as to stress the

primitive jaggedness of existence. Neither the audience nor the critics

were amused. During the first performance of Rite, a riot erupted in the

theater, but even it was unable to stop the artistic revolution that

Nijinsky had just unleashed.

Furthermore, the musical

score was very loud. The orchestra called for was immense, with a high

percentage of it being percussion. The sounds produced by the woodwinds

were distorted through the use of mutes, and the violins played down-bow

in order to create a louder, more dissonant sound. Nijinsky's

choreography was as jarring as the music. Every classical traditional

movement was eliminated: no jets, pirouettes, or arabesques. Movement

was reduced to jumping with both feet and walking in a stomping fashion.

The basic position of the dancers consisted of hunching towards the

ground, feet turned inward with great exaggeration, knees bent, arms

tucked in, and head turned in profile as the body faced forward. In

other words, the dancers appeared knock-kneed so as to stress the

primitive jaggedness of existence. Neither the audience nor the critics

were amused. During the first performance of Rite, a riot erupted in the

theater, but even it was unable to stop the artistic revolution that

Nijinsky had just unleashed.

In the future, this term became its own name for the direction in choreography.

In the future, this term became its own name for the direction in choreography.  Her "dance of the future", returned to natural forms, had a great influence on many artists who sought to free themselves from academic dogmas.

Her "dance of the future", returned to natural forms, had a great influence on many artists who sought to free themselves from academic dogmas.