How to write a dance song

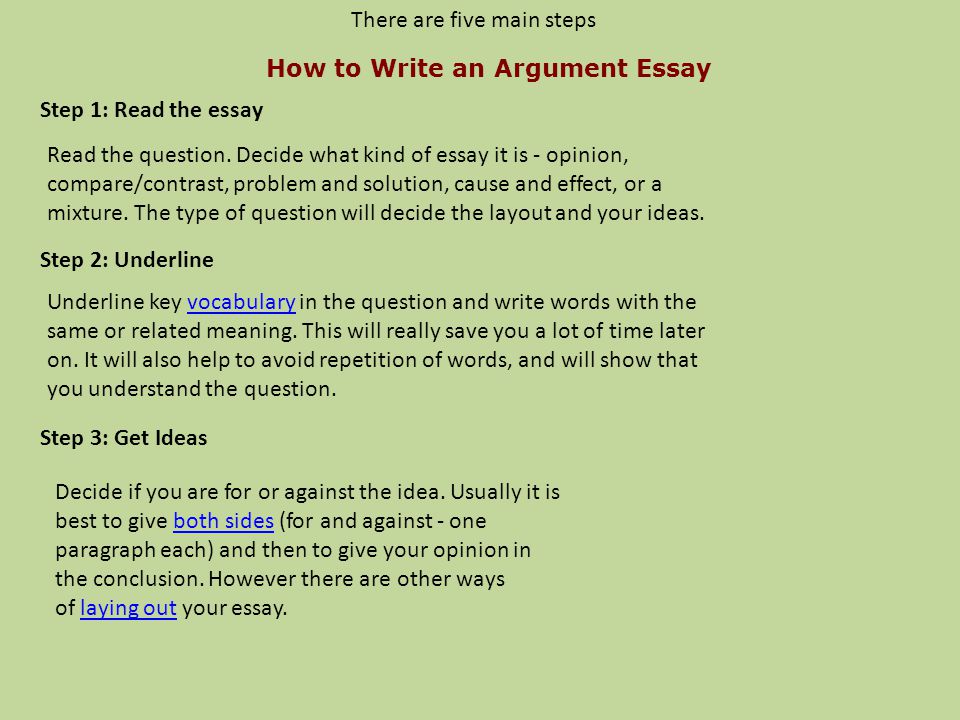

How to write a killer dance tune | Music

It's that famous DJ ... Roger something, er, ohwhatshisname ... oh, yeah Sanchez. Photograph: PR

Last week, I had an email from a German dance act. They'd heard some of the dance records I'd written and were wondering if I'd be interested in writing a top-line (melody and lyrics) to one of their tracks. I must admit, writing to track over the net is not my favourite way of working - I prefer sitting in the room with other writers and being able to change the chords if I feel the urge. Still, as a writer for hire you have to be flexible. It's fun to mix it up, and at least I'd be the only person writing for this particular track (as far as I know), which isn't always the case.

Recently, a label sent out a backing track to all the top-line writers they knew, asking them to write melody and lyrics for their girl group (I'm not allowed to say which one). This is quite a common practice in pop and dance music and works well for the labels. For the top-liners, on the other hand, it can be frustrating. It doesn't involve much collaboration or feedback and, if their top-line doesn't get chosen, chances are they end up with an unusable melody that sounds too much like the chosen one.

This label was honest enough to say that there was only 10% available of the song's copyright, since the track had a sample that would claim the main part of it. Some A&R people love suggesting tracks that the artist should sample (1980s electronica like Depeche Mode seems to be the flavour of the moment), and the girl group in question used a famous sample on their last single too.

I wonder if Matthew Dear got 50% of the songwriting credits when Fedde le Grand used his vocal sample for Put Your Hands Up 4 Detroit? When it comes to song splits, it's not about how many words you write - it's all about negotiating from a strong position. If the producer didn't ask before using the sample, they may have to give away most of the publishing. Roger Sanchez had to give Steve Lukather much more than 50% for using one line from the verse of Toto's I Won't Hold You Back in Sanchez's hit Another Chance. Of course, that line gets repeated over and over again, but still.

Roger Sanchez had to give Steve Lukather much more than 50% for using one line from the verse of Toto's I Won't Hold You Back in Sanchez's hit Another Chance. Of course, that line gets repeated over and over again, but still.

Like most people, I used to think that writing dance music must be ridiculously easy. After all, how difficult could it be to write one chorus (and possibly a verse too) about getting down on the dancefloor that gets repeated ad infinitum over a beat?

The first time I worked with a DJ/producer, he told me that he wasn't into writing the old "Take me higher" and "Put your hands in the air" dance cliches. "I like to write stories," he said. "Fantastic," I thought, as I strove to come up with original ways of describing a universal experience. "It'll be like country music with a beat underneath it." Of course, by stories he meant: "I see you across the dance floor. You look really hot. I want to take you home."

It's difficult to write something original with such a narrow choice of subject matter. Then again, the most important characteristic of a good dance top-line is not the profundity of the lyrics, but that they flow well. Don't clutter it up with too many words and stay away from long unusual ones. Use nice open vowels, not too many consonants and come up with a killer hook. If you manage to get an original lyrical idea that fits into these parameters, it's the icing on the cake - what makes a good dance track great.

Then again, the most important characteristic of a good dance top-line is not the profundity of the lyrics, but that they flow well. Don't clutter it up with too many words and stay away from long unusual ones. Use nice open vowels, not too many consonants and come up with a killer hook. If you manage to get an original lyrical idea that fits into these parameters, it's the icing on the cake - what makes a good dance track great.

Then again, my most successful dance track to date is called Turn on the Music, so forget that last bit. Maybe I'll go for the "Let's all come together and spread the love" theme for this one.

Composing Dance Music

Some painters say that they always slap some paint on a new canvas straight away, rather than looking at a blank canvas and panicking because they have no idea where to start. It's just as bad writing a short story, or an article — or a tune. Where do you start?

If you just have a vague feeling of “I'd like to write a tune” (or paint a picture, or build a house, or whatever) it probably won't happen. You need to get specific. I want to write a bouncy Irish-type jig. I want to write a stately Playford-type reel. I want to write a tune for this dance.

You need to get specific. I want to write a bouncy Irish-type jig. I want to write a stately Playford-type reel. I want to write a tune for this dance.

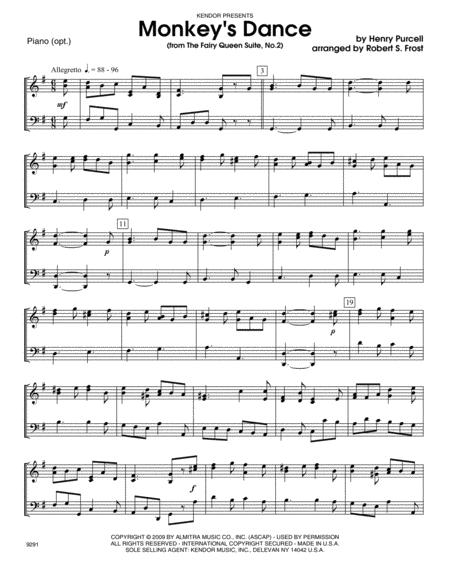

But there's an exception to this: when you're sitting at the piano, your fingers wandering idly over the noisy keys… and you think “That sounds good”! Always have pencil and manuscript paper handy, and write it down — it doesn't matter how much of a scribble it is, so long as you can read it. It's very difficult to strike a balance between writing down what you've just played and composing the next bit; many's the time I've composed the next bit and then found I had forgotten the first bit. Try not to be too critical: this is brainstorming, where first you get down all the ideas that might be floating around in your head. Later you can fit them together, improve some, discard others. Incidentally, I use manuscript paper which already has a treble clef and eight bars on each line — it saves time and makes it easier to jump from line to line when I have several possibilities at some points. You can print it out here — just click Print (PDF) and print it from your PDF viewer.

You can print it out here — just click Print (PDF) and print it from your PDF viewer.

Whichever of these two approaches you adopt, you will know what style you're working with. It might help to start with an existing tune in a similar style. You can copy elements of it — that's how you make sure it's within a particular style — but don't follow it too closely — that's called plagiarism! Don't suddenly switch styles in the middle of the tune — if it's a traditional-sounding tune and you suddenly throw in a couple of weird chords it will make people (including the musicians playing it) uncomfortable. Try lots of ideas. I will often play over a short phrase of music twenty times, making slight changes, until (maybe) I'm satisfied with it.

Most of my early compositions were songs, composed at the guitar. At one time I composed using an electronic organ, and there was a distinct danger that they would turn out as hymn tunes! Now I compose at the piano. Occasionally an idea comes into my mind while I don't have an instrument available, in which case I write it down as best I can.

There are two sides to any sort of creation: the creative and the mechanical. If you're a painter you probably need to know how to mix your paints, how perspective works, how shadows look, and so on. If you're writing music you probably need to know about keys, chords, musical phrases, sequences and so on. The trick is to get this to be part of your vocabulary so that it all happens subconsciously, leaving you free to do the creative part. If you have the discipline but aren't creative, you'll probably come up with something that's technically correct but rather boring. And if you're merely creative, without any discipline behind it, I don't think you'll come up with a good dance tune either. Often I have an initial idea — not necessarily the first few bars; it might be part-way through the tune. If I'm lucky I have some more inspiration later on. The rest of it is often sheer slog, but because I have a background in this sort of music it has more chance of working. Don't try to write in a style that you don't like; you probably won't be successful.

Enough of the generalities! Let me give you some specific rules, and then we'll see what you can come up with.

Tunes

Start with a straightforward format. Choose your rhythm, and write a 32-bar tune consisting of an 8-bar A-music repeated and an 8-bar B-music repeated. Stick to one key, or possibly modulate to the dominant (or the relative major or minor) towards the end of the A-music and get back to the tonic by the end of the B-music.

Play through some tunes you like, and try to analyse what makes them satisfying: phrase patterns, rhythm patterns, harmony patterns, chord sequences, bass line or whatever.

Give the tune variety but not too much variety — a good tune has coherence. I once wrote a tune consisting of two-bar phrases from eight Playford dances. It may have been clever, but it wasn't a good tune! A good tune sounds as if it knows where it's going, without being too predictable. It should be reasonably obvious that the A and B parts belong together. Maybe there's a musical phrase or rhythm at the start of the A-music and you can use this at the end of the B-music to tie things together.

It should be reasonably obvious that the A and B parts belong together. Maybe there's a musical phrase or rhythm at the start of the A-music and you can use this at the end of the B-music to tie things together.

It's a good idea if the tune sounds as if it's finishing at the end of the B-music, and doesn't sound as if it's finishing at the end of the A-music, though there are plenty of exceptions to the second idea — some tunes finish the A and B parts with the same two-bar phrase.

Decide if there is any stepping to be done to their tune. This should help with phrasing and rhythm. A good tune announces clearly that it requires a march around or skip or whatever.

Use a gimmick if you think you have a good reason, but don't overuse it.

If you've written a good phrase of music, one obvious trick is to repeat the phrase one note (or more) lower (or higher). This is called a sequence, and it's perilously easy to get hooked on one. Suppose you'd just written the first two bars of “Jenny, come tie my cravat” (Playford's original three-time tune, not the one Sharp used for the dance). It's in D, and it starts and ends on F♯. It would be very natural to repeat the same phrase starting on E, and that's exactly what the composer did. It's then far too easy to repeat it again on D, but that's a bad idea. I think it was Bach who said that you could use a musical phrase twice, but the third time you had to do something different with it. In this case the composer went back to starting the phrase on the F♯, but this time it ended by going up rather than down, and he rounded out the eight bars with something much higher and quite different. You might think the composer did get away with a third occurrence in the B-music of the Christmas carol “Angels from the Realms of Glory”, but don't take this as an example to follow. An even more dubious example is the B-music of another carol: “Ding Dong Merrily on High”.

Suppose you'd just written the first two bars of “Jenny, come tie my cravat” (Playford's original three-time tune, not the one Sharp used for the dance). It's in D, and it starts and ends on F♯. It would be very natural to repeat the same phrase starting on E, and that's exactly what the composer did. It's then far too easy to repeat it again on D, but that's a bad idea. I think it was Bach who said that you could use a musical phrase twice, but the third time you had to do something different with it. In this case the composer went back to starting the phrase on the F♯, but this time it ended by going up rather than down, and he rounded out the eight bars with something much higher and quite different. You might think the composer did get away with a third occurrence in the B-music of the Christmas carol “Angels from the Realms of Glory”, but don't take this as an example to follow. An even more dubious example is the B-music of another carol: “Ding Dong Merrily on High”.

Don't expect to get the tune right first time, and in the early stages be more concerned with getting the notes down than getting them perfect. I can use up a whole page of manuscript paper for just one tune, with several possibilities for each line, and I keep trying them all and changing them until I'm satisfied or I give up completely. And on many occasions I have hit a wrong note and thought “Oh, what did I do then!” — and it's become part of the tune.

If you're writing a tune for a specific dance, think about the dance moves which go to the tune. A musician looked at my tune “Helena” and said “Is there a set in bars 5 and 6 of the A-music?” — and indeed there is. Look at my tune for “Dutch Crossing”. It starts with a 16-bar A-music — because the movement is 16 bars long. The dance starts with two changes of a circular hey, so I put in a gap between bars 2 and 3, but then four changes of a straight hey, so there's no gap between bars 6 and 7. When it comes to the “Dutch Crossing” part (the hardest part of the dance) I didn't want the music getting in the way of the flow of the dance, so the C-music is absolutely regular four beats to the bar. And the D-music needs to fit two 4-bar moves each time, so there's a gap at the end of bars 4 and 8. I'm not saying that all tunes fit the dances as closely as this, but I certainly thought hard about what I wanted the tune to do as I was writing it. In fact I originally learnt a wrong version of the dance, and had to modify my tune to fit the correct version!

And the D-music needs to fit two 4-bar moves each time, so there's a gap at the end of bars 4 and 8. I'm not saying that all tunes fit the dances as closely as this, but I certainly thought hard about what I wanted the tune to do as I was writing it. In fact I originally learnt a wrong version of the dance, and had to modify my tune to fit the correct version!

Don't forget that you're writing dance music, and the dancers need to be comfortable with the phrases of music they are dancing to. There are tunes where bars 7 and 8 of the A-music sound as if they are the start of the next line rather than the ending of this line, and people get confused. “The Designing Woman” in Gary Roodman's book “Sum Further Calculated Figures” has a circle left in the last four bars of the B-music — but the tune doesn't come to a close there. The first time I called it I stopped the band, convinced that I'd got the timing wrong. Notice that on the recording by MGM and Reunion, they've changed the music so that it does come to a close at this point! There are tunes in waltz time where some or all of the four-bar phrases start on the bar before the one you would expect. A classic example is the Country and Western “Annie's Song” by John Denver — don't write a tune like this, and make sure bands don't use it!

A classic example is the Country and Western “Annie's Song” by John Denver — don't write a tune like this, and make sure bands don't use it!

Think about what key to write it in, and whereabouts on the stave the notes should fall. I never go below the G below the treble stave, because that's the bottom note on a fiddle (though flute and recorder players complain when I go below middle C), and I don't normally use more than one ledger line above the stave. I have no urge to write tunes in E flat since I wouldn't be able to play them, but do try to avoid writing everything in G. Just by starting in a different key you'll find that new ideas come into your head. If you discover that the B-music goes up into the stratosphere you can always change the key later, but while the creative processes are working don't interfere with them by doing a mundane job such as transposition.

Some people talk about graphing the emotional intensity of a tune, but I'm afraid I don't think that way. If you want a rule, try putting the highest note of the tune in bar 4 of the B-music, giving you four bars to get back on a level again!

If you want a rule, try putting the highest note of the tune in bar 4 of the B-music, giving you four bars to get back on a level again!

Chords

This is a whole different area. Let me start by assuming you know nothing…

I gave out unchorded versions of the three tunes and asked people to suggest chords.

Major chords

Suppose you're writing a tune in C (major) — that's the white notes on a piano. The scale of C runs C D E F G A B C, and these will be the notes of your tune, though you will probably use the occasional accidental (black note). The three standard chords (often known as the “Three chord trick”) are:

- The Tonic (C) which uses the notes C E G

- The Dominant (G) which uses the notes G B D (and often it's the Dominant Seventh which adds F)

- The Subdominant (F) which uses the notes F A C

You can harmonise each note of the scale with a chord containing that note: there's always one and there may be two.

| Note | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chord | C | G7 | C | F | G7 | F | G7 | C |

| Chord | F | G7 | C | F |

But you don't want to harmonise every note of the tune, and people playing the chords (on guitar, piano, accordion or whatever) don't want you to either! It will sound frantic and a complete mess, unless it's very slow and then it will sound like a hymn tune. If it's a reel or jig there are two beats (two walking steps) per bar, and most of the time you will want one or two chords per bar, falling on those beats. The other notes are often called “Passing notes”, and they pass without interrupting the chord sequence. For instance, here's a traditional tune:

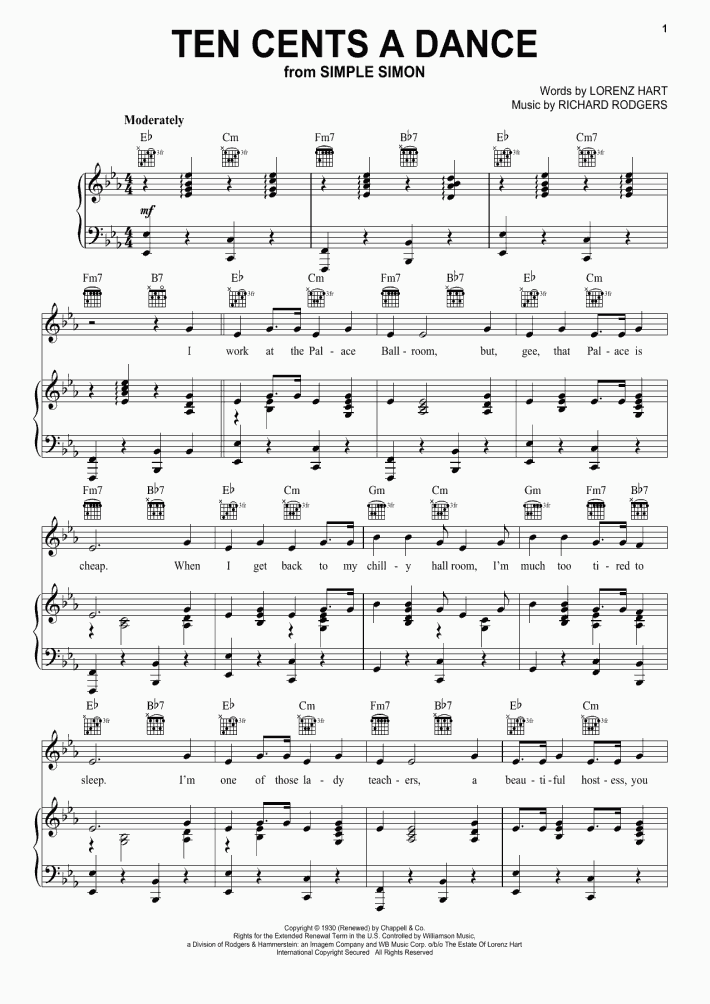

In America they normally put the chords above the line of music; in England we normally put them below.

I've chorded it using just tonic, dominant seventh and subdominant. In bar 1 the A note doesn't fit the chord of G — but that's a passing note so it doesn't matter. The same in bar 2, and in bar 3 it's the B that doesn't fit the D7. The same in bar 4, and even though the B is actually on the beat rather than a passing note it still works — to my ear it would sound wrong to switch to a G chord in the middle of the bar, even though in theory that would fit the notes better. I can't explain why, except to say that I don't like changing a chord half-way through a bar and then starting the next bar with the same chord. I've never read this anywhere or heard anybody else give it as a rule, so other people may tell you differently.

Some people only write a chord where it changes, so you might have G at the start of bar 1 and then no indication until there's a D7 in the middle of bar 4. As a guitarist (not playing or even trying to read the melody) I find this confusing, so I often put a chord at the start of each bar or each pair of bars, and if there's a change of chord part-way through a bar I would definitely put a chord at the start of the bar as well.

Going from the D7 in bar 7 to the G in bar 8 is called a Perfect Cadence, and it's the standard way of ending a tune; it's also quite common at the end of the A-music. To my ear it would sound wrong to finish the A-music with a C chord (and even more wrong to finish the B-music with one), though some bands might do this at the end of B1 as a gimmick (they would call it a musical effect) to indicate that they haven't reached the end of the tune yet. It's a weak ending, and this is a strong tune.

Of course there are lots of other chord possibilities. To my ear a dominant seventh wants to go to the tonic. In bar 4 the C note is the seventh of the chord, so it's there whether you put it into the chord or not, and I would not consider going to a C chord at the start of bar 5. Some people would prefer bar 7 to have G and then D7, but I don't hear it that way. I suppose my rationale is that the tune seems to split naturally into two-bar sections, and I want a chord change at the start of each section to accentuate this. If I did start bar 7 with a G chord and I were playing piano I would give it a D bass note to indicate that it was somehow a “different” G from the one in the preceding bar. Bars 7 and 8 would then constitute a Cadential 6/4 which is much used in classical music and (particularly) hymn tunes.

If I did start bar 7 with a G chord and I were playing piano I would give it a D bass note to indicate that it was somehow a “different” G from the one in the preceding bar. Bars 7 and 8 would then constitute a Cadential 6/4 which is much used in classical music and (particularly) hymn tunes.

The chords in the B-music are identical to those in the A-music, which you sometimes find with traditional tunes. What about bar 2 of the B-music? The notes on the two beats are E and C, so why have I used a G chord which doesn't contain these (though it does contain the passing notes D and B)? Because it sounds right to me — and you may disagree! It's all part of the descending scale of G which started in bar 1. If I did use a C chord in bar 2, I would then feel the need to use different chords between bars 3 and 4, for symmetry. Again let me emphasise that this is just my opinion. So if I wanted two chords, what would I use? Here's a suggestion, and it involves a hint of a modulation — going into a different key. I visualise the tonic as being the “present”, the dominant as the “past” and the subdominant as the “future”. You may well think this is weird — I've never mentioned it to anyone before and I don't know anyone who thinks of it in this way. If you modulate to the dominant (in this case change key from G to D) you have gone into the past. But that time also has its own past and future. The future is G, where we just came from. The past is the dominant of D, which is A or A7. So following the G and C chords of bars 1 and 2 I just might use A7 and D for bars 3 and 4. We go from the present to the future, then to the distant past, then to the past. (If the analogy doesn't help you, please forget it.) Perhaps another advantage is that the relationship between G and C is the same as the relationship between A and D. If I were playing piano I would emphasise the A7 chord by playing a C♯ bass note rather than an A — this gives a nice run up of C, C♯, D.

I visualise the tonic as being the “present”, the dominant as the “past” and the subdominant as the “future”. You may well think this is weird — I've never mentioned it to anyone before and I don't know anyone who thinks of it in this way. If you modulate to the dominant (in this case change key from G to D) you have gone into the past. But that time also has its own past and future. The future is G, where we just came from. The past is the dominant of D, which is A or A7. So following the G and C chords of bars 1 and 2 I just might use A7 and D for bars 3 and 4. We go from the present to the future, then to the distant past, then to the past. (If the analogy doesn't help you, please forget it.) Perhaps another advantage is that the relationship between G and C is the same as the relationship between A and D. If I were playing piano I would emphasise the A7 chord by playing a C♯ bass note rather than an A — this gives a nice run up of C, C♯, D. You can indicate bass notes against your chords if you wish (though there's no guarantee that anyone will play them): in America it's usually written A/C♯ and in England it's usually a capital A with a lower-case c♯ directly below it. If you go to my 3-couple Dance Instructions page for instance, you will see lots of dances which have music — click the treble clef sign beside the titles. You can then display the musical notation in either English or American format. “The Grandparents' Waltz” has several chords with bass notes.

You can indicate bass notes against your chords if you wish (though there's no guarantee that anyone will play them): in America it's usually written A/C♯ and in England it's usually a capital A with a lower-case c♯ directly below it. If you go to my 3-couple Dance Instructions page for instance, you will see lots of dances which have music — click the treble clef sign beside the titles. You can then display the musical notation in either English or American format. “The Grandparents' Waltz” has several chords with bass notes.

And then I might use just a C chord in bar 5. I know I rejected that in the A-music, but that was because the previous chord was automatically a D7 because the seventh was there in the tune. This time it isn't, so the possibility exists. Of course, if I was the only chord instrument in the band I could vary things between turns of the tune anyway.

Minor chords

As a generalisation, minor chords are sadder than major chords, but that's not to say you shouldn't use them to accompany a happy tune — just don't overdo it! The Relative Minor of G is E minor, usually written Em but sometimes Emin or even Emi. I've also known a few people write minor chords in lower-case, em, but I don't see the point of that. The relative minor of C is A minor and the relative minor of D is B minor, so you can certainly throw those in where required. Notice that the G chord is G B D, the C chord is C E G, and the Em chord is E G B — in other word it's a half-way house between the two major chords, having two notes in common with each of them. Similarly Am is half-way between C and F.

I've also known a few people write minor chords in lower-case, em, but I don't see the point of that. The relative minor of C is A minor and the relative minor of D is B minor, so you can certainly throw those in where required. Notice that the G chord is G B D, the C chord is C E G, and the Em chord is E G B — in other word it's a half-way house between the two major chords, having two notes in common with each of them. Similarly Am is half-way between C and F.

Probably the only minor chord I would put into Jimmy Allen is Am in bar 3 of both the A- and B-music. I would keep the D7 in bar 4: it's much stronger to lead into the G of bar 5 with a D7 than with a second bar of Am. Play the three possibilities through a few times and see whether you agree with me. Having added the Am you might decide to change bar 2 from the repeat of the G to an Em. What do you think? The sequence G, Em, Am, D7 is certainly very well-known.

When I started this I had no idea I would find so much to say about chording a simple tune! Don't let that put you off the idea altogether. The first set of chords I gave are perfectly good — no-one is going to say they are “wrong”. But there are other possibilities, and I wanted to show them to you and try to give some reason for using or not using them. When it comes down to it, the only real question is: Does it sound right? If you're writing a traditional-sounding tune (or chording an existing traditional tune) it's best to stick mainly with tonic, dominant and subdominant. As I've said, relative minors are pretty safe, though watch out that you don't make the tune too gloomy (unless you want a gloomy tune). On the other hand I've written some odd tunes which need odd chords — have a look at my tune for Lucy and you'll see an extreme example which I would not ask most bands to play. It even includes the trick I disparaged earlier, where the listener expects a perfect cadence but instead gets an interrupted cadence (E7 to F at the end of the fourth line), signalling that the tune doesn't stop after 32 bars as they were expecting, but has an extra four bars. But then it's not pretending to be a traditional-style tune.

But then it's not pretending to be a traditional-style tune.

I'm keen on diminished chords (a musical theorist would say “diminished seventh chords”) but most dance composers don't use them and plenty of bands simply won't play them. On occasions I've used major seventh, augmented, half-diminished though I would describe it as an A minor with an F♯ bass, and it's also known as F♯m7♭5 (F♯ minor seventh with a flattened fifth), suspensions and maybe others. Don't use them just because they're there, but because they bring out the sound you want. And be aware that someone will have to play this stuff! If you really want to know more, here's a video on the 7 Levels of Jazz Harmony — but don't expect me to play it!

Minor key

I've given examples of major chords and then minor chords, but both of these were for a tune in a major key. Suppose the tune is in a minor key. There are one or two additional problems!

The relative minor of C major is A minor — they have the same key signature which is no sharps or flats. Music theorists will tell you that there are two minor scales — the harmonic minor scale (used for harmonies, i.e. chords) and the melodic minor scale (used for melodies, i.e. tunes). The melodic minor scale is different going up and going down, and I've never found either of these much use in writing tunes or chords. There is actually a third minor scale, the natural minor scale, which is simply the white notes A B C D E F G A — no accidentals at all. Music theorists don't know about this so they will tell you you're wrong and that the leading note must be sharpened — in other words you must use G♯ rather than G natural. This is not true, and it's particularly not true in folk music. Then they'll say “Ah well, it's modal”. In other words it doesn't fit into their definition of Minor. That's OK — it's just terminology and ultimately (as always) the question is “Does it sound right?”. If you really want to know about modal tunes, try http://www.

Music theorists will tell you that there are two minor scales — the harmonic minor scale (used for harmonies, i.e. chords) and the melodic minor scale (used for melodies, i.e. tunes). The melodic minor scale is different going up and going down, and I've never found either of these much use in writing tunes or chords. There is actually a third minor scale, the natural minor scale, which is simply the white notes A B C D E F G A — no accidentals at all. Music theorists don't know about this so they will tell you you're wrong and that the leading note must be sharpened — in other words you must use G♯ rather than G natural. This is not true, and it's particularly not true in folk music. Then they'll say “Ah well, it's modal”. In other words it doesn't fit into their definition of Minor. That's OK — it's just terminology and ultimately (as always) the question is “Does it sound right?”. If you really want to know about modal tunes, try http://www. campin.me.uk/ Music/Modes/

campin.me.uk/ Music/Modes/

I could draw up a table with one or two minor chords against each note, as I did for the major scale, but that's not really how it works unless you desperately want it to sound miserable. You normally have some major chords to accompany a minor tune, and that means there are a lot more possibilities. I've also added G♯ to the list of notes because you will certainly find a sharpened leading note in some minor tunes.

| Note | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | G♯ | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chord | Am | G | Am | G | Am | Dm | Em | E7 | Am |

| Chord | F | Em | C | E7 | C | F | G | F | |

| Chord | Dm | E7 | F | Dm | Em | C | Dm | ||

| Chord | E7 |

Of course you may not use most of these. There are many Irish tunes which (in the key of A minor) just use the chords of Am and G. “What shall we do with a drunken sailor?” is an English example of the same thing. But let's get more interesting.

There are many Irish tunes which (in the key of A minor) just use the chords of Am and G. “What shall we do with a drunken sailor?” is an English example of the same thing. But let's get more interesting.

This is a song, a morris dance tune and a country dance tune (Green Sleeves and Yellow Lace) and I've given Vaughan Williams' version of the melody and chords, though I've taken it down a semitone from F minor to E minor.

The first two bars use the tonic (minor) and then the major chord a tone below, just like “What shall we do with a drunken sailor?”. Some versions of the tune would have a C natural rather than a C♯ in bar 1, but it doesn't affect the harmony. Some versions would have a D♯ rather than a D natural in bar 4, which would change the chord from Bm to B7. In bar 7 all the versions that I know have a D♯. Conventional music theory says that the dominant chord of a minor key is a major chord (and probably a seventh chord) but it depends on the tune — here we have Bm in bar 4 but B7 in bar 7. Vaughan Williams has drifted into E major in bar 8, which they certainly did in the old days too.

Vaughan Williams has drifted into E major in bar 8, which they certainly did in the old days too.

What about the B-music? Every C is a C♯, so it appears to have modulated to D major, which is quite a good thing to do — it gives a change of feeling and stops the tune becoming too mournful. Yes, we could have thought of it as modulating to Bm and used Bm for bar 1 and F♯m Bm for bar 2, but it needs a bit of a lift at this point. We could also have used D for both bars, which are almost running down the scale of D, but that's not nearly as interesting as going from G to D — try it and I hope you'll agree. Bar 4 really has to be Bm unless you use two chords, and Vaughan Williams is clearly making a point of only one chord per bar except for the perfect cadence at the end of each line. Bar 3 could be C rather than Em, which gives the descending bass line D | C | B, but I prefer Em, which means two bars of major followed by two bars of minor. I might be tempted by D followed by Bm in bar 6.

This is a song and a morris dance tune — you'll find lots of different versions and I'm certainly not claiming that this is the “right” one, but it's the one I've chosen.

In the A-music I've used minor chords except for the D. I've already shown Em — D — Em in Greensleeves (and Drunken Sailor) and you'll come across this a lot. A music theorist might tell you that the leading note should be sharpened, so he would change the D to a D♯ and the chord to B7 (the dominant of Em) giving a perfect cadence. I would certainly start with Em to establish the key. I could have used G and D rather than Em and Am in bar 2. I wouldn't use Em and D there though, because we get this in bar 3. I don't mind using the same pair of chords in bars 1 and 2, or bars 3 and 4, but not in bars 2 and 3, and if you can't hear that I don't think I'll convince you! On the same principle I wouldn't use G as the chord for bar 2 of the B-music because we have a G in bar 3, though I would be happy using the same chord for bars 1 and 2 or bars 3 and 4 of a tune.

The second half of the B-music is the same as the A-music, and I see no reason to change the chords (though Cecil Sharp often did in repeats).

Two other points

One approach to tune writing (which I've never tried) is to start with a chord sequence and then write the tune to fit this — it just might help you if you've been staring at that blank sheet of manuscript paper for far too long.

And one final bit of advice: put it away and play it through tomorrow. What you thought was a masterpiece may well be rubbish, but it's difficult to be critical when you're in the throes of composition. Maybe most of it is fine, but there are a couple of points where it just doesn't work. Maybe you can improve these. Maybe you'll just have to lose that really nice phrase because it doesn't fit in with the rest of the tune. This is a vital part of the job. It may take more time that the original composition, but it can make all the difference between a tune that is OK and a really good tune that people will want to play and dance to.

Example

For those who really want an in-depth view of the creative process as it relates to dance music, here's an account of how I wrote the tune to Unrequited Love. (By the way, the reason I'm talking mainly about my own tunes is not that I think they're better than anyone else's, but that I know them well and sometimes remember my creative processes.)

On this occasion I started with the first two bars of the tune. Repeated notes on the bar-line can be banal — think of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” — but across the bar-line they can have an emotional impact. As I played the phrase, thirds below seemed an obvious thing to add to the melody. It was natural to repeat this phrase as a sequence a third below. It was then very tempting to repeat it a third below that, but bearing in mind Bach's advice I expanded it into a four bar phrase which did something different — though again the repeated note across the bar-line.

Here I would demonstrate it without the expansion, and then with it.

That gave me my first eight bars A1, ending with a suspension on the dominant chord. The next eight bars immediately sprang to mind — A2, repeating the first six bars less one note and ending on the tonic note and chord.

Now I had to do something different, but related, as I came to the so-called “middle eight”, so I started with the dominant chord. This time it's a four-bar phrase, but notice that the second half is the original two-bar phrase again. The natural follow-up to this is of course a sequence, but this time a third above rather than a third below, so the middle eight has a rising feeling to it.

My first thought at this point was to repeat A2, giving a 32-bar tune. But that didn't really have enough to it. So again I went for something different, this time starting on the subdominant chord. Although it's different, it starts with a near-variant of the original two-bar phrase, and again in bars 5 and 7. Having added this eight bar phrase (C) I felt justified in copying B as D (with the addition of an augmented chord on the last note) and copying A2 as E.

It didn't all happen quite as logically as this — there were several other attempts. The coda came from a different version of the tune which I'd started, put away and forgotten. It's more dramatic — we meet the only accidental in the entire tune, and this is over a diminished chord. The sound is restless, confused, as if the tune doesn't know where it's going for a moment. I rediscovered this and thought “I've got to use that somewhere”. I once danced “Unrequited Love” to Barbara Kinsman's calling, and she said of the coda, “This is the point where I always think the tune has gone wrong”. Fortunately the band was Wild Thyme, who had recorded it on their “Hunter's Moon” album, and they assured Barbara that it didn't sound as if it had gone wrong to them! Notice that the last two bars are the original motif yet again — consistent to the end.

How I learned to write dance music and started releasing on labels — Music on DTF

A big story about finding yourself in creativity. With pictures and music.

With pictures and music.

14012 views

Hi, I'm Muchkin. I write music. I make money with soundtracks for indie games, and for my soul and career, I also make tracks in the genre of melodic house and techno. About how I came to composing, I wrote in a recent text. Now let me tell you about my path in dance music.

Screenshot of my latest project so far

Beginning

Somewhere in the ninth grade, I first heard Prodigy - Voodoo People (Pendulum Remix) as part of a mix from DJ Stroitel. I got crazy and started to get interested in drum and bass. I listened to Pendulum, Noisia, Spor, danced drum and bass dance, which we called drumstep.

Then I thought that I also want to write the same energetic cool music with rich drum parts. I had no idea how it was done, and the search led me first to some kind of MIDI editor, in which I made a couple of songs. And then I found FL Studio, a sequencer that I've been using for over a decade.

The first tracks were terrible.

I shared them under a shameful pseudonym on PromoDJ, in an active community of fellow beginners. We intelligently criticized each other's tracks, not knowing anything at all about how music is created. But it's always like that when you start.

I once read the idea that you need to make the first 100 songs as quickly as possible, because after them normal music will follow. In my experience, yes, something like this is

Toward the end of school, a dream began to form in me: I will learn how to make cool music for the university, and by the end of the fourth year I will become, if not a world star, then certainly a professional and respected music producer (a person who earns money by creating and performing electronic music ).

University

In fact, for four years at university, I basically did only three things: studied (albeit well), played video games and suffered from fears and anxieties. Despite the fact that the dream still lived somewhere on the border of consciousness, and I considered myself a music producer, writing tracks faded into the background.

Despite the fact that the dream still lived somewhere on the border of consciousness, and I considered myself a music producer, writing tracks faded into the background.

It wasn't because I was lazy or because I didn't want to make music. Just because I thought of a great success in advance, creativity turned into a hard and painful task. High anxiety, disorders, traumas, and just the peculiarities of the psyche (which I realized only ten years later thanks to psychotherapy) exacerbated the situation.

For example, I wrote this track for a whole year and spent more than hundred hours on it . That was the pace at which I produced finished works at that time.

Funny story. Born in Space found some cunning guy on PromoDJ and wrote me, they say, let's release it on my label. I went nuts from the word "label" and agreed. We even signed some kind of contract through the Proton system. After that, the man disappeared. Until now, the composition can be found on streaming services - he released it ten times, probably, and all under different "labels".

I didn't make a dime from it, of course. I suspect that he is also

Among my other works during this time, one can single out this psychedelic “neurofunk”, in which everything that is possible is not in tonality. When I wrote it, I did not yet know what tonality was.

This was supposed to be an intro for my friend's YouTube show, but it never launched.

At the university, I wrote little music, but this does not mean that I did not develop creatively. I listened and analyzed bass genres a lot and sometimes through suffering I made tracks. Many did not finish. So there was progress, but very slow.

This composition also took about a year and 60-80 hours of work.

My music from this period seems to meet some minimal requirements of the genres (the structure is readable, the sounds are more or less intelligible, the kick and snare give some kind of energy, sometimes there is even a sub-bass), but they are crooked, poorly thought out and uninteresting .

I just used samples, notes and instruments that seemed appropriate and didn't think about the big picture, melody or atmosphere. And, I suspect, for the better. If I had been worried about this as well, then anxiety would have completely crushed me.

By the way, my suffering also had some advantages. From the very beginning of working in FL Studio, I decided that I needed to create all the presets for the synths myself, and so I did. By the time I received my diploma, I had a good knowledge of the standard synths of the program and even a small library of presets.

By the way, about the diploma: I wrote this experimental composition dedicated to a headache closer to the defense, which is symbolic.

Work

After my bachelor's degree, I went to the master's program and at the same time started looking for a job. For a year and a half, I was doing all sorts of small jobs (once I even made the whole foley for a short film). I didn’t do much music, although I was able to complete a couple of projects.

For example, this future beats track inspired by Ivy Lab and Noisia Radio selections.

And an old school drum and bass remix for Dorn (there was a PromoDJ contest).

I was looking for ways to make money on music: I applied to local game and recording studios, I tried my luck in creating beats and stock tracks. In vain. As I studied the market and read the stories of more successful producers, an unbearable, terrible thought formed in my head.

To achieve something, you have to work very hard

That explained a lot.

At the beginning of 2017, I was accepted to DTF. Since childhood, I loved games, I read LKI, the Land of Games and Igromania, so I was very happy with this opportunity.

I was part of the editorial staff for almost two years. At this time it was difficult to find the strength and time for music. I watched tutorials, analyzed other people's tracks, replenished my database of samples and presets, but completed projects during this time can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Weird downtempo project - time.

Dubstep with the voice of YouTuber Jacksepticeye - two.

Gloomy base house - three.

Drum and bass, started back in 2016, four.

I tried to send each of these tracks to labels, but they were not taken anywhere. I was surprised: how is it that they have everything. And powerful basses, and cool drums, even some interesting effects. Isn't that enough?

Oh, how little I understood.

Composing

In the spring of 2019, I started building a career as an indie game composer. A few months later, this occupation even began to bring in some money and soon became the main one for me. (You can read about this path here.)

I found a way to make money with music and immersed myself in creativity. A little bit not the direction that I dreamed of, but still it was progress. Working on the soundtracks, I learned to feel the music better, learned new techniques and added to my own libraries even more.

As for dance tracks, at the end of 2019, aggressive and fast base house was popular, and I tried to sit on this hype train.

But no labels took the track, so I released it myself through distributor DistroKid. It was my first "adult" release - the one that appeared on streaming services. So far, I have earned exactly $0.03 on it. That's 17 auditions.

Back in the beginning of 2020, I made time for the LEAVEMEALONE halftime track.

The flops over the past couple of years made me wonder: what is wrong with my music? Why doesn't anyone want to take it? Reflection and reflection led me to an important conclusion: in the first place, I do not make the music that I really want.

I became interested in making music thanks to drum and bass, then I started listening to dubstep and electro house, and for some reason I always felt that these genres were what I needed to work on. But as soon as I listened to myself a little (which I had never done before), it turned out that I had nothing to express through bass music.

Therefore, I spent the following months looking for genres that would most accurately reflect my inner state. They were melodic house and techno.

Brute force

Since April 2020, I have decided to get into dance music properly. Since I used to be able to create compositions only through force, I came up with a challenge for myself: to finish one track every month.

The logic was like this. By forcing myself to work on dance compositions month after month, sooner or later I had to develop all the necessary skills needed to create cool music.

I was going to basically brute force my creative powers

The first track turned out to be clumsy. The mixing is murky, there is not much development, both drops are arranged as if it were a summer banger, although a soulful melodic techno was conceived. But for starters, it will.

This track (and several others) I released again via DistroKid. Even tried to buy ads for him through Facebook. There were still few auditions (39 to date), but I was resentful of the label system after so many rejections and was determined to make a name for myself.

The next composition in May, Pasturage, was much softer. Birds, forest, nice sound design and summer rain atmosphere.

For this track, I also purchased advertising. This time I set up the ad better and invested more money, so the output was more tangible. Now he has 138 plays.

The June track Arcane turned out to be mysterious and attractive, like a Celtic forest. Hence the name.

I did not commission advertising for him, because the determination to promote myself in the music industry began to fade. I didn’t pour so much money into advertising tracks, but there was no more extra money.

The conclusion was that you can break through on your own only in two cases: if you have a lot of money for advertising (I didn’t), or if you know how to do cool PR in social networks (I didn’t know how).

labels again.So I started looking towards

Arcane was not taken to the labels (I did not even hope), but they took Autarca - the July track. Here's a snippet of it, and you can listen to it in full here.

It was released as a compilation on the sub-label of a small St. Petersburg publishing house Polyptych. I knew perfectly well that this would not bring me any money or popularity, but I signed the contract anyway. You have to start somewhere.

The next track was a bit hooligan Help a Robot. I didn't send it anywhere, because big labels wouldn't take it, and it was long and tedious to look for small labels with such music. How do you even google them? "Labels with frivolous electro-house"?

In autumn I decided to make a three-track mini-album. For some reason it seemed to me that labels were more willing to take EPs than singles.

Even by this moment I had heard a lot of music in the selected genres and realized that in melodic house and techno, few people make tracks shorter than six minutes. So from now on, all my new compositions slowly fade in and out.

In general, the music has become less hasty and more conducive to immersion and thoughtful listening

As you might expect, my plan to boost my chances with labels with the EP didn't work out very well. The release was eventually taken to the same Polyptych Limited (it will be released on July 5), but I was hoping for something bigger.

In December I finished the new track Rewired and decided to take a break. Working non-stop for nine months (and I also did soundtracks) without tangible results led to the fact that I just burned out.

Rest helped me rethink my priorities and figure out which way to go. I stopped caring too much about labels and started focusing more on creativity and self-expression. Plus, psychotherapy helped (and still helps) to listen to yourself better.

Rewired was included in the compilation for the Moscow label ONESUN (will be released sort of like in the summer).

Opening

I wrote the next composition at a more relaxed pace: burnout forced me to abandon the "one track per month" mode. Simultaneously with the work on the track, I was doing research. He carefully studied music in the chosen genres, pestered successful producers with questions, whom he could reach.

The result was the biggest takeaway of all time: major labels need unique music first and foremost. One that has not yet been

Within the genre, of course, although the boundaries between melodic house and techno are blurred.

How to achieve uniqueness? For me, the answer is simple: it comes from the uniqueness of the psyche. If you learn to listen well and express yourself adequately, then creativity will be unique. Therefore, when creating Bird Law in January 2020, I tried to listen as often as possible to what melodies, sounds, effects and just decisions resonate with me.

This track doesn't just meet some technical requirements, it's undeniably my . For example, the title is taken from a comic book that I really like.

It's the law

And the theme of birds in it is not only because of the name, but also because these animals (but not all) touch me and my wife very much. And also partly a track about the love that I feel for my wife, and this has something in common with the comic book. In general, a warm work about good things. The ones in me.

I don't know how noticeable this is to the outside listener, but I see a massive improvement over the previous compositions. He was even taken to a more serious label - the Italian Natura Viva. They promised to release it as part of a compilation. I don't know when exactly: for some reason, labels rarely notify me about such things, and I myself don't really care. I'm more focused on future works.

The last track so far is called You're Not What Your Mind Tells You. It's about my many battles with my own brain. It is a little sad, but with a light undertone, because no matter how scary the battles are, there is always a possibility to win. At least I can.

The other day I signed him to the Belgian label Sound Avenue. It will first be released exclusively on Spotify to try and push it into the platform's playlists, and will be released as part of a sub-label compilation in August.

After You're Not What Your Mind Tells You, I again rethought my creative process. Now I try to treat music less as a series of separate projects and more just as a field for experiments, from which cool completed projects will grow. Let's see where this takes me.

Such things. Thanks for reading. By the way, I will soon launch a course on creating electronic music from scratch. If interested, you can read the details here.

If you like my music, you can subscribe to Soundcloud, YouTube or Spotify. All my future tracks will appear there as well. Also here are my social networks: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Twitch.

9 ingredients of a hit

Songwriting for many is a magical process. When famous hitmakers are asked about how they write songs, they most often talk about muse, inspiration and other unconscious things.

But tell me – as a songwriter, you want to know specifically – what, how, why, where, etc.? There are many questions, but no answers.

Creation of songs, like any other creativity, is a process that can be considered from two sides - from the side of spirituality and from the side of craftsmanship. As you know, the components of any brilliant work of art are 50% inspiration and 50% work. (Although for the modern world the formula of 5% inspiration and 95% work is closer). Therefore, knowledge and skills are simply necessary for those who want to write songs (and even more so sell them).

How conscientious are you when creating a song? Do you think about how to improve it, make it hit, etc.

Let's look at the components that make up any hit song.

- Successful name

- Harmony

- Expressive melody (or rhythmic for dance hit)

- Khuk

- Text

- ARENDICT END EASTS 0003

- Song title

Very often the title of a song comes up before a concert, after recording an album, before releasing a CD, etc.

This is a very big mistake. The title of the song is the same as your name. Imagine parents who give their child a name only when it's time to send him to school 🙂

The name should be remembered and attract attention. It is simply vital for a hit song to have a unique title that can become a household name.

This is what marketing calls mastering the word.

For example, there is no way out, blood type, forever young are phrases associated with songs. As is clear from the examples, the name should be repeated in the song and be the basis of the chorus.

2. 90% of modern songs are written in pre-composed harmony.

What does this mean?

This means that most of the sequences are already so worn out that it is enough to play three or four chords and the listener will feel that your song is already familiar to him. On the other hand, this approach eliminates the uniqueness of the melody and leads to self-repetition. How many songs are written for the sequence C-Dm-F-G?

There are tens of thousands of them and it is very difficult to stand out from this mass. How many songs use the Am-F#m sequence?

The only one I know of is the Doors Light My Fire song.

As you can see, unusual combinations allow you to instantly stand out. However, you need to use non-standard speeds in combination with those familiar to the listener, so you maintain the right balance. It is very important to accumulate the baggage of chord progressions and constantly look for new combinations.

So you will always have in your asset material to create hits.

3. Melody

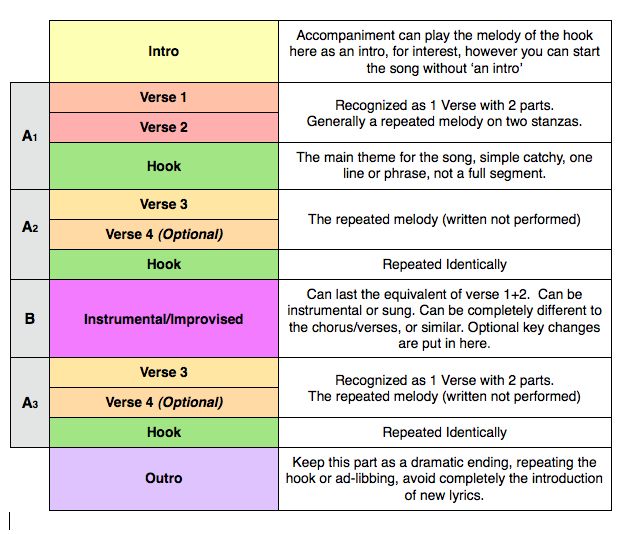

Melody is the basis of any song. Hit melodies are characterized by a reliance on repetition, a gradual expansion of the range, a contrast between the verse and the chorus, an emphasis on the tonic in the chorus, and the active use of a hook (which may not be in other genres of music).

The choice of reference notes plays a very important role.

Many authors fall into the trap of the same stages, because they do not analyze their melodies and do not write them out in notes.

Even well-known authors sin with this.

Analyze your melodies - if you use a lot of stable steps (1, 3, 5), then you may need to look for new intonations in the area of unstable ones. It is also possible to penetrate into the realm of chromaticity, where limitless possibilities are hidden (chromatic hit of all time Flight of the Bumblebee).

Also an interesting example of chromatic moves can be found in Rihanna's song Breakin' Dishes

Analyze other people's melodies and use the knowledge gained in your work.

4. Hook

This is a short melodic, rhythmic phrase, lyrical phrase that is the core of a song and that the listener can sing along after listening to the song. This is what is spinning in the head (hook - trap)

The main condition for a hook is its length - the shorter the better. The short hook can be a whoop (as in Blur song 2). The longer hook can be a 4 bar melody replacing the chorus. Various kinds of chanting on syllables sound spectacular (na-na-na, pa-pa-pa, etc.)

Example of a polyrhythmic hook (Till The World Ends):

Hooks can be combined. Ideal when instrumental, vocal and text hooks are combined.

5. Rhythm

Rhythm is the most important element of a hit. Find a good beat and your song is doomed to success. In terms of rhythm, most of the hits are based on ostinato, repetition and the use of short syncopated figures. Use the contrast of even rhythm and syncopated to enhance the contrast. An important role is played not only by the rhythm of the melody, but also by its comparison with the rhythm of the text.

A typical example of a song built around the rhythm organization Smooth Criminal. The whole verse is built on three notes, an upward movement of the minor scale

6. Lyrics

Good lyrics contain memorable phrases. However, the main difficulty of song lyrics is the presentation of original ideas in simple words. Try to avoid banal and hackneyed phrases and words such as:

my girl, blue jeans, forever, body, fantasy, reality, heart beats like grief, cuts to the heart, wound in the heart, wound in the heart, wind of change, all all night long, angel, baby, fire, desire, let them talk, let me go, from the very beginning, on the street, standing in the rain, stop time, shining like the sun, walk along the edge (edge), can't get out of my head, I almost lost my mind, it's all inside of me, the sky above my head, deep inside

and others of the same plan.

In general, most hits contain simple text that is easy to remember. Moreover, rhyme, as such, is not a mandatory element of the song

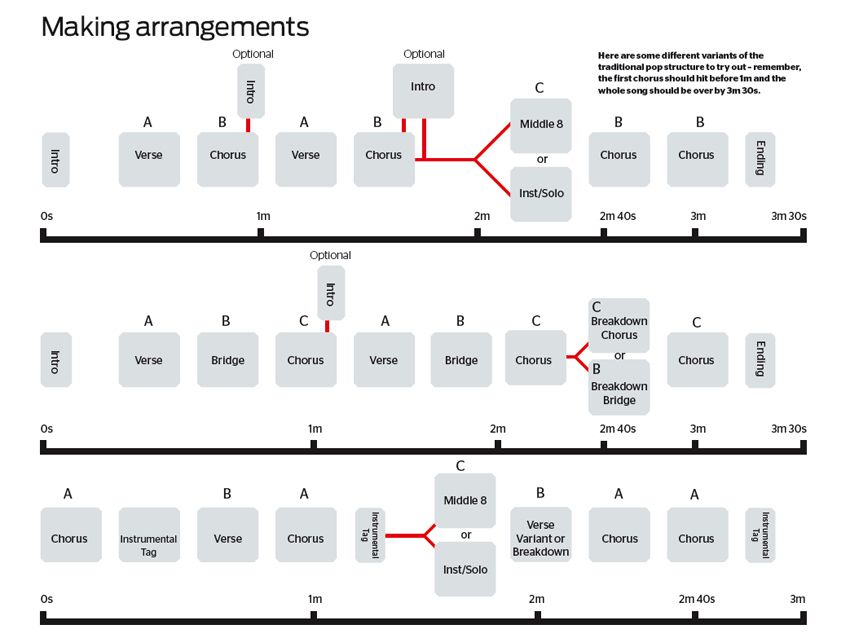

7. Arrangement

Even if you do not take part in the creation of the finished product, the ability to show the finished song is a great advantage. Properly done arrangement will emphasize the uniqueness of the song and may also contain hooks. It is important that the arrangement does not "kill" the idea of the song and does not prevent the listener from enjoying the melody and lyrics.

8. Mixing

This is an area of work for sound engineers and I do not recommend that you do it yourself, even if you are a professional sound engineer. At this point, it's important to step back and let the song live its own life.

9. Marketing and production

This is out of the scope of the songwriter (mostly). Creating a song is just the first step. The main work begins after you have a finished product.