How to spin like a ballet dancer

Super spinning tips and how to turn better in dance -

Lots of teachers (and other advanced dancers) get annoyed by non-teachers trying to teach people how to dance. I’m not going to do this, because if you want to dance well and improve it’s about getting good basic dance lessons, and practice.

But so many people struggle to spin and haven’t ever been taught. Here are the tips I was given via different teachers through the years. Tips from 13 years of ballet classes and 2.5 years of salsa where we were taught turning and spinning drills from a Guinness world record holder for spinning.

Hopefully some of these spinning tips will help you in both turning and spinning better as you dance.

1. Know the difference between a spin and a turn

A turn is stepping as you rotate, in modern jive that’s usually via a ‘return’ or travelling return. A spin should be on one foot and can be a free spin or aided by the leader.

2. Learn to spot

If you get dizzy when spinning, learning to spot is essential. It’s all about practice so that you’ll do it automatically. Essentially you’re leaving your eyes looking at one spot in front of you as your body turns, then when you can’t leave your head behind anymore, you whip your head around so your eyes are looking back at your spot again as the rest of your body follows. You can start slowly and build it up. This video is a simple beginner technique for starting out.

There’re plenty of YouTube tutorials and guidance on how to spot while spinning, and it does help reduce dizziness especially during multiple splns. I find spinning is easier than continuous turning in one direction because spotting is easier when you’re preparing to spin in one place.

3. Spin and turn on one foot

To spin you need as small an area as possible on the floor. Using two feet will act as a brake and make you unable to turn.

4. Turn on the ball of your foot

I’m naughty at this because I do get lazy and tend to relax into my heel when I turn, but you should be turning on the ball of your foot. Your heel needs to only be slightly off the floor. But having your weight over the front of your foot will keep your body in the right place for turning without wobbling off in a different direction.

5. Don’t lift your spare foot up

When spinning, sometimes you see people lift their spare foot in the air (usually, bending at the knee, I presume it’s a natural reflex or they want to keep the spare foot out of the way). This will make you wobble and can also catch your partner or anyone else dancing closely. When doing a basic spin, you want to keep your spare foot next to your anchored foot, just above the floor. This keeps your body centred over your legs and should help keep you upright. It’s much hard spinning with one leg raised.

It’s much hard spinning with one leg raised.

6. Think down into the ground, not up in the air

Lots of dancers lift up when trying to spin. This could be because they’ve done ballet in the past which is about pirouetting on your toes in a releve position. But it’s more likely that we often turn under the leader’s and our raised hand, so the body tends to follow upwards as well.

Yes, you need to straighten out your body and think open rather than tight and leaning over, but if you keep your knees slightly bent and think about drilling into the floor, you’ll be more balanced and grounded. It will certainly suit a more grounded dance than one like ballet which is much lighter and in the air. You’ll also move less when you’re spinning.

It’s hard to explain. But if you’ve done any latin dancing or salsa, where you need to feel the floor through your feet to get the right hip action, the grounding and turning into the floor rather than upwards, is the same sensation.

7. Have good posture

To spin well, you need to engage your core. You need to stay relaxed and not tense up your shoulders, pull your tummy in and tuck your bottom under.

Then keep your arms in a suitable position. The easiest position for a free spin is to bring your arms towards each other in front of you, at chest level, in an oval shape. Bringing one arm to join the first helps with impetous in a spin, but also keeps posture and position right. Oh and flailing arms isn’t a good look.

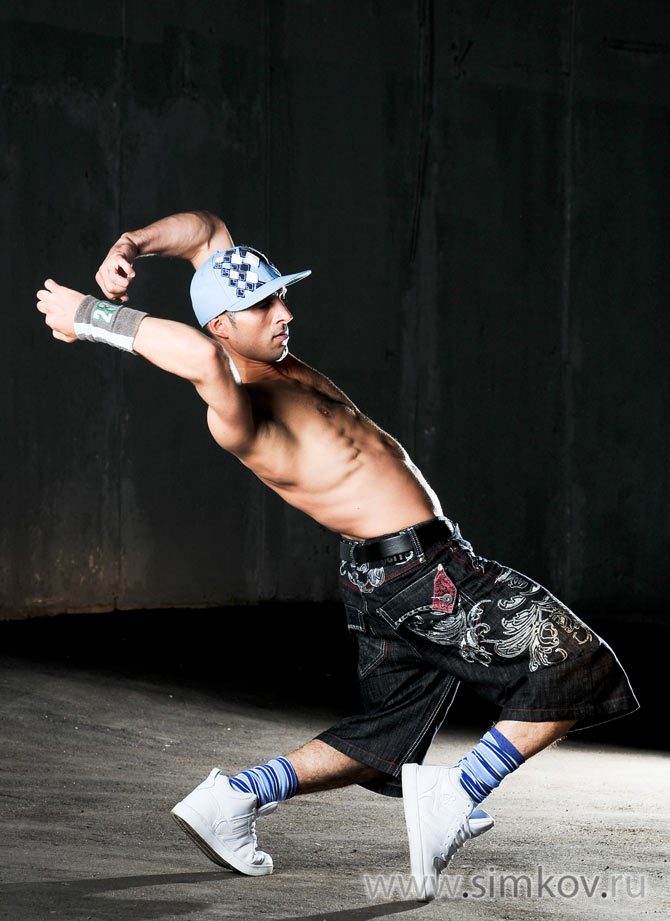

This clip shows a comfortable arm position and the posture needed (salsa – they do a lot more spin technique than modern jive! but you can still get tips on arm, body and foot position)

8.

Don’t look down

Don’t look downIf you look down your weight balance will move and you’ll be more likely to fall. Look straight ahead for a steadier turn (or spot if you use that technique).

9. Don’t rush

So many people panic when they have to spin and try and go whooshing off really fast. But if you’re spinning or turning to music, you want to fill the beats you’re spinning on. If it’s a slow track, you’ll have longer to do one rotation. There’s no point whizzing round to find there’s still half the beat left to go.

10. Practice

It’s all about practice. Start with a single spin, and work up to multiple spins if you want. If you can do free spins yourself, it’s easier to then be led into aided multiple spins or turns. This clip shows the use of a clock method (admittedly for salsa spins with the prep, but the idea is the same for modern jive).

Tips for leaders

Most spinning is done by the follower, but these all apply to leaders as well. Plus if you’re prepping your partner for a spin, there’s things to be aware of.

Plus if you’re prepping your partner for a spin, there’s things to be aware of.

Don’t ever force the follower into a spin. You can prep for one (either raising the arm or prepping the follow for a free spin), but only they can do the spin.

Ensure your prep is accurate. If it’s a free spin, don’t prep the spin too far out from the follower’s centre, otherwise they will be off balance and the spin won’t work. If it’s an aided spin, raising your hand and the follower’s, to just above and in front of the follower’s head. Not really high above their head otherwise they’ll struggle to keep connection. And not below the top of their head otherwise they’ll have to duck which is a totally different move.

Own your spin

[bctt tweet=”The person spinning should always be the one in control of the spin ” username=”whatabout_dance”]

A final point to remember is that you don’t have to do multiple spins. Yes sometimes it’s nice to throw some in if the situation is right and the music calls for it. For example, I can do a double or triple (when I’ve been practising for a while), but I rarely do more than a single in freestyle. Because I’d rather have an immaculate single spin than try a multiple spin when the lead or prep doesn’t feel right, or the floor isn’t smooth enough. I’ve never had a leader moan that I’ve refused to do a double when he’s led that. I’ve usually had people compliment me on my spins.

For example, I can do a double or triple (when I’ve been practising for a while), but I rarely do more than a single in freestyle. Because I’d rather have an immaculate single spin than try a multiple spin when the lead or prep doesn’t feel right, or the floor isn’t smooth enough. I’ve never had a leader moan that I’ve refused to do a double when he’s led that. I’ve usually had people compliment me on my spins.

How do you get on with spinning? How were you taught?

Like this:

Like Loading...

Practice Spinning, Tiny Dancer - Scientific American Blog Network

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Reddit

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Print

In another life and probably like many little girls (or at least, all the ones in my dance classes), I took 14 years of ballet lessons. They gave me grace and a pretty good sense of balance.

One of the things I also ended up able to do was the fouettee en tourne:

(I was not NEARLY as impressive as this dancer)

And it looks great, right? Nothing elicits cheers from an audience quite like a truly huge series of fouettees, they're kind of the cheat to make people cheer. And they SHOULD cheer, what that dancer is doing took hours and hours of practice.

But now, try it. Try spinning around (not on your toes, on two flat feet, no injuries people!). After about three turns...the world starts to spin. You get dizzy. Because most people do. I remember getting dizzy as a child, and looking at the older dancers, and wishing and wishing I could be like them. But after a while, I was spinning like a pro. And even now, when I dance (salsa or something, say), my partners tend to be very impressed with my ability to spin. You can put me on my toes, start spinning me around, and GO. Two turns? Nothing. 3,4,5,6? Not a problem!

(Sadly, not me. Source)

There are a few tricks that ballet dancers use to help them spin. The biggest one is "spotting", fixing your eyes at a spot on the wall (or wherever you're headed), and keeping them there, whipping your head around at the last possible second to make sure your eyes stay put as long as possible. If you look in the video above, you'll see her head is turning just a bit faster than the rest of her. She's spotting.

The biggest one is "spotting", fixing your eyes at a spot on the wall (or wherever you're headed), and keeping them there, whipping your head around at the last possible second to make sure your eyes stay put as long as possible. If you look in the video above, you'll see her head is turning just a bit faster than the rest of her. She's spotting.

But spotting alone doesn't make her, or me, good spinners. As we danced, our brains changed.

Nigmatullina et al. "The Neuroanatomical Correlates of Training-Related Perceptuo-Reflex Uncoupling in Dancers" Cerebral Cortex, 2013.

Long training of basically any kind is going to change the brain. Because let's be honest, pretty much everything changes the brain. Long term training in music changes the brain, for example. So does eating breakfast (at least temporarily). While we could just snark off and say "well everything changes the brain", what's fascinating are the different ways the brain is changed.

And in ballet dancers, the brain is changed in a very specific way. Dancers get very good at spinning because certain aspects of their brains desensitize to the turns. Specifically, the vestibular system, the system that controls your sense of balance and vertigo (dizziness), is desensitized in dancers, allowing them to turn more without getting dizzy.

Dancers get very good at spinning because certain aspects of their brains desensitize to the turns. Specifically, the vestibular system, the system that controls your sense of balance and vertigo (dizziness), is desensitized in dancers, allowing them to turn more without getting dizzy.

But how exactly is it desensitized? To figure this out, the authors got 29 dancers with 16 years of experience (average age 21, all female), and matched them to 20 controls (also female, average age 21). I was very pleased to see they matched them for physical activity, dancing is very athletic, and the dancers worked out up to 20 hours a week, they managed to get controls that were matched to the average of 7 hours a week.

The first thing they did was test their vestibular-ocular reflex. This is a function of the vestibulocochlear nerve, and is the reflex responsible for making your eyes fix on a point during head rotation. So, for example, fix your eyes on this:

SCIENCE.

Now, fixing your eyes on "SCIENCE", turn your head to the right. Keep your eyes on the science. :) Your eyes will move left. That's the vestibular-ocular reflex.

Keep your eyes on the science. :) Your eyes will move left. That's the vestibular-ocular reflex.

To test this out, the authors used a swiveling chair, that spins people around in various ways. They can measure your vetibular-ocular reflex by measuring how much your eyes move. During it you turn a wheel with your hand, and you are supposed to turn it with the amount of rotation you feel you are experiencing, which allows them to measure the perception of the vestibular-ocular reflex, as well as the reflex itself.

(Figure 1: the sciencey version of the worst carnival ride you've ever been on)

From this test, they get two measures, which you can see in the graph on the bottom. The first is a measure of how dizzy you feel (perceptual, the grey trace), the second is the eye movement (the bottom trace). They were able to show that dancers had a decrease in the vestibular-ocular reflex. They moved their eyes less as they whipped around (remember my description of spotting?). And they also felt the turning less than controls. More importantly, the dancers sense of turning, and the vestibular-ocular reflex, were UNCOUPLED. They were not related to each other. So even though their eyes were moving in the reflex, they didn't feel it!

And they also felt the turning less than controls. More importantly, the dancers sense of turning, and the vestibular-ocular reflex, were UNCOUPLED. They were not related to each other. So even though their eyes were moving in the reflex, they didn't feel it!

But what does this mean for the brain? The authors put the dancers and the controls into an MRI to measure the the grey matter volume (representing neuronal cell bodies), in the cerebellum, an area highly associated with balance and the vestibular-ocular reflex. They were able to show that the grey matter in the vestibular area of the cerebellum was lower in dancers than it was in controls, which might help explain the uncoupling between the feeling of spinning and the vestibular-ocular reflex in the dancers.

Of course, this is a correlation. It's possible that training can reduce the cerebellar grey matter and produce this effect...but it's also possible that the people who go on to be successful dancers have smaller cerebellar volume in that area to begin with. To really find this out, you'd have to take a bunch of people who never danced, run the tests, give them intensive dance training (a few years maybe), and run them again. Of course, many professional ballerinas began dancing when they were VERY young (I began when I was 4), and so some of these changes could have occurred during development. You'd need to take two sets of kids, run the tests on the kids, put half in dance and the other half in maybe another sport that involves no spinning, like soccer, and follow them over time. A more difficult experiment, but potentially extremely interesting.

To really find this out, you'd have to take a bunch of people who never danced, run the tests, give them intensive dance training (a few years maybe), and run them again. Of course, many professional ballerinas began dancing when they were VERY young (I began when I was 4), and so some of these changes could have occurred during development. You'd need to take two sets of kids, run the tests on the kids, put half in dance and the other half in maybe another sport that involves no spinning, like soccer, and follow them over time. A more difficult experiment, but potentially extremely interesting.

But this study is important for more than dancers! It could also be very helpful to those who experience a lot of dizziness due to vesitublar-ocular problems. It could be that accustoming the patients to spinning (maybe through dance class?), might help uncouple the reflex from their perception, and help them feel less vertigo. A leap from dance to sickness that could be...dizzying. :)

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Scicurious has a PhD in Physiology from a Southern institution. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy and a Bachelor of Science in Biology from another respected Southern institution. She is currently a post-doctoral researcher at a celebrated institution that is very fancy and somewhere else. Her professional interests are in neurophysiology and psychiatric disorders. She recently obtained her PhD and is pursuing her love of science and writing at the same time. She often blogs in the third person. For more information about Scicurious and to view her recent award and activities, please see her CV ( http://scientopia.org/blogs/scicurious/a-scicurious-cv/)

Climate Change

5 Things to Know about Climate Reparations

Evolution

Vertebrates May Have Used Vocal Communication More Than 100 Million Years Earlier Than We Thought

Public Health

Which COVID Studies Pose a Biohazard?

Astronomy

Dazzling New JWST Image Shows Dusty Stellar Spirals

Quantum Physics

Researchers Use Quantum 'Telepathy' to Win an 'Impossible' Game

Vaccines

New Halloween 'Scariant' Variants and Boosting Your Immunity: COVID, Quickly, Episode 41

Physics in ballet - Informio

Dancers - athletes of God

Albert Einstein

Ballet is the art of plasticity, inspired, filled with feelings, expressed movements, life, embodied in choreographic vocabulary; this is one of the most famous theatrical performances, the basis of which is dance. Not everyone thinks about how much effort a dancer puts in to master his body, learn the subtleties of ballet mastery, and achieve ease of performance.

Not everyone thinks about how much effort a dancer puts in to master his body, learn the subtleties of ballet mastery, and achieve ease of performance.

The weightless, floating, striving movements of the dancers seem to be arguing with the laws of physics itself. As much as we would not like to believe in the magical mystery of choreographic art, it is worth noting that it is this natural science that creates the entire dance, embodies the ideas of the directors and helps us understand body language.

If classical dance could be expressed by a formula, it would look like this:

Physics + prepared body of the performer + emotions and acting = BALLET

A hypothesis arises: knowledge of the laws of physics and their application in the work of dancers will help them perform elements and reduce the likelihood of injury to artists.

In order to confirm your hypothesis, you need to analyze the following points:

- Equilibrium. Balance is an important part of the barre and exercise.

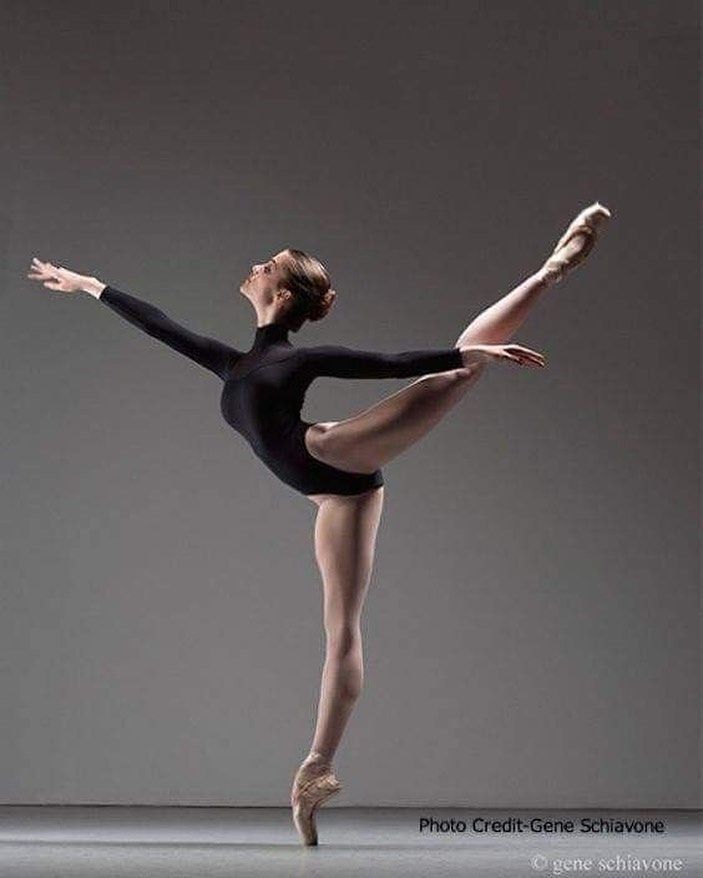

Quite often, it is difficult for beginner dancers to maintain balance, even with support. For example: rond de jamb en l'air (rond de jamb en leer), battement fondu Fig. 1 (batman fondue), Arabesgue (arabesque).

Quite often, it is difficult for beginner dancers to maintain balance, even with support. For example: rond de jamb en l'air (rond de jamb en leer), battement fondu Fig. 1 (batman fondue), Arabesgue (arabesque).

Standing confidently, and often even on one foot, will help to follow a simple rule: the vertical projection of the center of gravity must be inside the support area. A clear example of this law is the Leaning Tower of Pisa, it does not fall, because the pattern is observed (a slight violation is permissible, since it is dug into the ground). If the center of gravity of the performer shifts, then the person has to step over and take a new position. The dependence also works: the higher the center of gravity, the more difficult it is to maintain a stable position. So, for example, in tumbler-type toys, it is located very low, so they are stable.

- Rotations. The rotation technique is also not unimportant in classical dance, oddly enough, they directly depend on balance, but in these cases slightly different laws apply.

Examples of rotations: pirouette (pirouette), fouetté (fouette), etc.

Examples of rotations: pirouette (pirouette), fouetté (fouette), etc.

We will be able to understand how a ballerina performs rotational movements with great speed if we analyze the position of her body. The performer stretches out, like a string, and puts her leg or arm perpendicular to the movement being performed. It seems as if she is repelled each time from an invisible wall. In fact, the dancer's main assistant is the law of conservation of angular momentum - in order to increase the speed of rotation, you need to reduce the mass or bring it closer to the axis of rotation. This is done by pressing the arms or legs to the body.

- Pirouette (pirouette)

Starting the pirouette, the dancer puts her supporting foot on her toe, pushes off the floor with her working foot, giving herself a rotational impulse. In a fraction of a second, she takes the necessary position, which corresponds to the moment of inertia, so the initial speed of rotation of the performer is quite low. The ballerina presses her hands and lowers her leg. The moment of inertia is reduced by 7 times, the angular velocity increases by the same amount - due to which the ballerina makes several quick turns on the toe, and in order to stop spinning, she again raises her leg and arms, the speed decreases, and the dancer stops.

The ballerina presses her hands and lowers her leg. The moment of inertia is reduced by 7 times, the angular velocity increases by the same amount - due to which the ballerina makes several quick turns on the toe, and in order to stop spinning, she again raises her leg and arms, the speed decreases, and the dancer stops.

- Fouetté

When performing fouetté, there are two principles - manifestations of the law of conservation of angular momentum. It is known that the angular momentum is a vector directed perpendicularly (in our case, vertically upwards) and proportional to the speed of angular rotation.

There is a trick that is used when making a fouette: the dancer raises her hands to the 3rd position, thanks to which she starts to spin faster. This is also carried out because of the same law.

So, we can conclude: all shocking rotations are the correct application of the law of conservation of angular momentum and rotational momentum.

- Jumping.

Jumping is the most time-consuming part of a classical dance lesson. Preparing for jumps takes a huge amount of time in order to strengthen the muscles and build leg strength.

Jumping is the most time-consuming part of a classical dance lesson. Preparing for jumps takes a huge amount of time in order to strengthen the muscles and build leg strength.

The acceleration of the dancers during the jump is comparable to the results of the best athletes (high jumpers). The dancer's body during the jump develops a speed of up to 4.5 m/s in about 0.25 s. Divide 4.5 m by 0.25 s, and we get an acceleration equal to 18 m/s (2g). For example: an elevator, starting to move, has an overload from 1.3 to 1.6 g.

Find the power of the ballet dancer's jump. Let's assume that the mass of the dancer is 65 kg, which means that the work is equal to 650 joules (0.16 kilocalories). Therefore, the power of a jump lasting 0.2 seconds is 650 J/0.2 s. we get 3250 watts (3.3 kW), which is approximately = 5 horsepower. In order to shoot up, the performer needs to make as much effort as possible in order to change the horizontal component of the gained speed into a vertical one. The horizontal speed of the dancer is approximately 8 m/s, and the vertical speed is 4.6 m/s.

The horizontal speed of the dancer is approximately 8 m/s, and the vertical speed is 4.6 m/s.

- Grand jet

How do dancers achieve the "flying illusion"?

Performing grand jet, the dancer seems to be flying over the stage, but in fact her center of gravity describes a parabola, like any object during the fall is guided solely by the gravitational force. But the human body changes configuration during flight. When jumping, the ballerina expands her legs and arms. Such a maneuver makes the landing (fall) almost imperceptible and creates a feeling of weightlessness of the performer.

- Pas de Chat

Another jump that creates a similar illusion is Pas de Chat (cat's step). The dancer makes a plié, and while increasing her step, she sharply raises her knees in turn, it turns out that at the moment of the highest position, the legs are in the air at the same time. The dancer seems to freeze in the air for a split second. Landing, she lowers her legs also in turn, which makes the fall soft and smooth.

The ability of a ballerina to hold a position in the air is called a balloon.

Landing is an important part of the jump, as the laws of physics dictate that momentum must be dissipated. A heavy landing would destroy the whole illusion of lightness, and, perhaps, injure the dancer. The secret to solving the problem is a floor designed to absorb impact. Also, the ballerina bends her knees (plié) and stretches her leg from toes to heel. This is necessary not only for the artistic intent, but also for the safety of the performer. This technique should be taught by competent teachers.

To cope with her part, the ballerina seems to defy the earth's gravity, working to the maximum. The fundamentals of physics and the science of human perception provide an understanding of how this is achieved.

- Support. Support is one of the most beautiful elements of ballet numbers. (Appendix Fig. 3-5)

In a circus, for example, one performer can hold the whole group, balancing a little, so that the center of gravity of the whole “construction” passes inside the support area. A ballet dancer hardly has to keep more than one partner. Therefore, he easily maintains stability when performing various supports, making sure that the general center of gravity of the performers is always exactly above his feet.

A ballet dancer hardly has to keep more than one partner. Therefore, he easily maintains stability when performing various supports, making sure that the general center of gravity of the performers is always exactly above his feet.

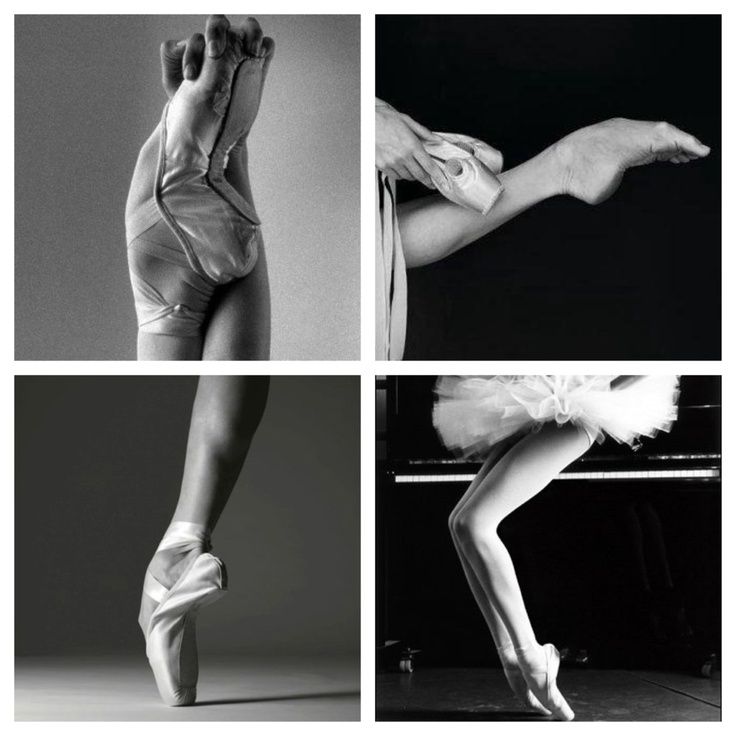

- Pointe dance. Pointe dance is one of the enchanting art forms, it seems as if the performer is levitating, smoothly crossing the stage space. (Appendix, Fig. 8) The elements made by the ballerina are light and intangible. Working on tiptoes is a titanic work that is not visible to the viewer. The muscles of an ordinary person are soft, while those of a ballerina are more like iron rods, strong and hardy. After all, in a different scenario, the dancer would not be able to keep her weight on the heel of her toe shoes (Appendix, Fig. 6) with an area of 2 cm2.

As they say, "the dancer's feet are fed", but this is actually not a joke. If a dancer injures his legs, which happens very often in the field of choreography, but he cannot recover for a long time and goes out of shape.

The ballerina's feet are doomed to injury and torture. (Appendix, Fig. 7) This is the other side of the coin, which the viewer does not see. The most common professional injuries of ballerinas are sprains, dislocations, fractures and injuries of the ligamentous apparatus of the joints. All this will lead to inflammation of the pelvic organs.

Suppose the ballerina's mass is 50 kg, let's calculate the pressure with which she presses on an area of 2 cm2.

Given: SI Solution:

S=2cm2 2*10-4m2 P=F/S

m=50 kg F=m*g

F=m*g

Р=m*g/S

P=10 m/s2*50 kg/2*10-4m2=2500000 Pa=2.5M Pa – pressure produced by one foot.

For comparison, this is 100 times the pressure exerted by a tracked tractor on the ground.

Such enormous strength hides under the guise of a fragile, almost transparent ballerina.

Comparison of the laws of physics and elements of classical dance

|

An element of classical dance. |

The law of physics. |

| Arabesgue (arabesque) - a position when the dancer balances on one leg | Stable balance, center of gravity |

| Pirouette | Law of conservation of angular momentum of a body |

| Fouette | Law of conservation of angular momentum of a body |

| Grand jet | Gravitational force, center of gravity |

| Support, ballerina upper support on one arm | Stable balance, center of gravity |

| Pointe Dance | Solid body pressure, stable equilibrium |

Everything that happens on the stage of the theater is a gigantic, collective, hours-long work. Sitting in the auditorium, it is impossible to imagine that every dancer devotes his whole life to the art of ballet, exhausting training. It is worth remembering that dance is not only physical exercise, but also acting.

It is worth remembering that dance is not only physical exercise, but also acting.

Based on all of the above, we can conclude that an artist is not only a physically prepared person, but also, to some extent, a physicist. After all, each number must be perfectly worked out, and without knowledge of physics it is quite difficult. Accordingly, the preparation is carried out with the help of this exact science.

As a result of the study, it was proved that the ability to use the laws of physics is directly related to the career and dancing abilities of a ballerina.

References:

- Myakishev, G.Ya. "Physics. Textbook grade 10 "[Text] / G.Ya. Myakishev, B.B. Bukhovtsev. - M.: Enlightenment, 2010 - 356 p.

- Krasovskaya, V.K. "History of Russian ballet" [Text] / V.K. Krasovskaya. - M .: Education, 2012 - 215 p.

- Rymkevich, A.P. "Physics. Task book for grades 10-11 "[Text] / M .: Education, 2012 - 192 p.

Original work:

Physics in ballet

Appendix to work

Unwind: Ballet technique

The thesis “In the field of ballet we are ahead of the rest” the country has been repeating like a mantra since the 60s of the last century. Much has changed since then, but even now, from a distance of four decades, the Soviet ballet of that time looks like the undisputed world leader.

Much has changed since then, but even now, from a distance of four decades, the Soviet ballet of that time looks like the undisputed world leader.

TechInsider

Fuetes and Fueters

A technical boom in women's classical dance occurred at the end of the 19th century and the Italians, who often toured in St. Petersburg, were to blame for it. For one such visiting star, Pierina Legnani, who performed at the Mariinsky Theater for several seasons in a row, in 189In 5, the main Russian ballet, Swan Lake, was staged. The strong Italian, who shone with excellent pointe technique, just at that time was fighting St. Petersburg with her fouette - an as yet unseen type of spin. The very number of revolutions on one leg was unusual - it never occurred to anyone that this was possible. Old Petipa immediately added a novelty to the coda - the very end of the pas de deux of Odile and the Prince, choosing suitable music for this (fortunately, Tchaikovsky wrote in abundance). So once and for all, the maximum number of fouettes was legalized - 32 pieces, according to the number of musical measures.

So once and for all, the maximum number of fouettes was legalized - 32 pieces, according to the number of musical measures.

Of course, Pierina Legnani carefully kept the secret of her know-how. The Russian ballerinas, who tried to repeat the trick, could not understand how exactly the Italian makes her turns and how she manages to stay in one place on the stage - a "patch" with a diameter of half a meter. Independent attempts to master the ingenious pas were not crowned with success: after eight revolutions, inquisitive enthusiasts began to feel dizzy - they lost their “point” (during rotation, it is necessary to fix your gaze on your reflection in the mirror of the rehearsal room or on an imaginary “point” in the darkness of the visual, for which you should do not turn the head along with the body, but, holding it as far as possible, then quickly turn it ahead of the rotation of the body). Ambitious Russian soloists were drawn to Enrico Cecchetti for training: this Milanese virtuoso settled in Russia after a successful tour, became the first dancer, choreographer and tutor of the Mariinsky Theater. The joint efforts of the teacher and students bore fruit: the secrets of the Italian were revealed, and the fouette became an indispensable part of the classic pas de deux. The first Russian ballerina to show her 32 fouettes to the most respectable audience was the main star of the Mariinsky Theater, Matilda Kshesinskaya: the favorite of the heir to the throne was distinguished not only by her alcove and secular successes, but also by her colossal capacity for work.

The joint efforts of the teacher and students bore fruit: the secrets of the Italian were revealed, and the fouette became an indispensable part of the classic pas de deux. The first Russian ballerina to show her 32 fouettes to the most respectable audience was the main star of the Mariinsky Theater, Matilda Kshesinskaya: the favorite of the heir to the throne was distinguished not only by her alcove and secular successes, but also by her colossal capacity for work.

The aesthetic and socialist revolution prevented the improvement of the fouettes in hot pursuit. Only in the 1930s did some virtuosos (primarily Olga Lepeshinskaya) begin to complicate this step. Fouettes were taken seriously only in the 60s. Not being able to go beyond the number 32 due to the strict limit of music, instead of 360 degrees, the ballerinas turned twice as much - by 720. Thus, two turns instead of one were obtained for the same piece of music. Usually, after three "single" followed by a "double" fouette (and so eight times in a row). For the sake of originality, especially advanced soloists changed the “point”: three fouettes were performed facing the audience, on the fourth one one and a half turns followed, and the ballerinas performed the next three fouettes with their backs to the audience. Changing the “point” required special self-control and a developed vestibular apparatus.

For the sake of originality, especially advanced soloists changed the “point”: three fouettes were performed facing the audience, on the fourth one one and a half turns followed, and the ballerinas performed the next three fouettes with their backs to the audience. Changing the “point” required special self-control and a developed vestibular apparatus.

The performance of the fouette “without hands” is considered a special chic - resting them on the sides. In this case, "force" - an impulse to movement - is given only by the "supporting" leg. Ekaterina Maksimova once demonstrated this kind of fouette with amazing ease and grace. In modern times, the ballerina of the Bolshoi Galina Stepanenko is considered the uncrowned queen of the fouette. The pinnacle of her triumph was the triple encore of the fouette: at the Bolshoi Theater, to the stadium roar of the audience, she (with short pauses for the inevitable bows) scrolled 96 turns!

No one counted the varieties of thirty-two fouettes - their number is limited only by the imagination of the artists. And the quality requirements remained the same - not to leave the "patch". Moving forward is still acceptable, but if the ballerina is tossed from side to side or carried diagonally to the ramp, this is an obvious marriage. The effect of a high-quality fouette is enhanced by a fast pace and a high (80 degrees) raised “working” leg, snapping turn after turn with a whip.

And the quality requirements remained the same - not to leave the "patch". Moving forward is still acceptable, but if the ballerina is tossed from side to side or carried diagonally to the ramp, this is an obvious marriage. The effect of a high-quality fouette is enhanced by a fast pace and a high (80 degrees) raised “working” leg, snapping turn after turn with a whip.

Revolters and revolters

In the second half of the 19th century, the prima ballerina firmly reigned in the classical ballet of all countries of the world (with the exception of little Denmark), so that female technique was constantly evolving and improving. Their partners were destined for the modest role of respectful gentlemen. The men did not object to this arrangement: the main parts could be danced at least up to sixty. Technical tricks were revered as something base-circus and were the lot of minor soloists (the main pre-revolutionary virtuoso was by no means the great Nizhinsky, but the dancer Georgy Kyaksht).

After the revolution, fresh players appeared on the ballet field, bare by wholesale emigration - young dancers, thirsting for transformations. Having inherited a very limited set of movements from their pre-revolutionary predecessors, they received boundless scope for experiments. There were only two main inventors, but it was their activities that determined the face of Soviet ballet for the entire 20th century. They were Asaf Messerer (Maya Plisetskaya's uncle) and Alexei Yermolaev.

Fragile, small, weightless, foldable Asaf added to an already existing movement some harmonious appendage, or a turn, or a skid, which made it look much more masterly. A successful athlete who started ballet unacceptably late - at the age of 16, Asaf easily inserted acrobatic elements into classical dance: he hung in the air, bending into a ring; folded in half in a jump; came up with a whole dance imitating football movements. Almost all the steps invented by Asaf Messerer entered ballet use so smoothly that they lost their authorship long ago and now look as if they have existed for centuries.

Another legendary inventor is Alexey Ermolaev. Muscular, violent and powerful, he was the opposite of the graceful Messerer. Yermolaev invented new movements with cheerful fury, and tortured his own flesh with the fervor of a religious fanatic. He preferred to work at night so that no one would see his "kitchen". There are legends about Ermolaev's trainings. He practiced pirouettes in the dark, holding a "dot" on the flame of a candle - to improve the vestibular apparatus. He was hung with bags of shot to develop the strength and height of the jump. During the performance, having got rid of the load, he simply hovered under the grate.

Even without altering classical movements, Yermolaev managed to change them beyond recognition. What this miracle dancer did, so far no one has been able to repeat (at least on stage) - neither the world idols Nureyev and Baryshnikov, nor the Soviet star Vladimir Vasiliev.

One of the most controversial pas was the double revoltade invented by Yermolaev. "Single" is also not a gift: you need to jump up, throwing the body back and throwing the leg forward parallel to the floor, then throw the "jogging" leg over this natural bar, simultaneously turning the body and hips 180 degrees, and land on this very "point" leg, leaving the other in the air at the same height. So Ermolaev managed to roll around his own leg twice!

"Single" is also not a gift: you need to jump up, throwing the body back and throwing the leg forward parallel to the floor, then throw the "jogging" leg over this natural bar, simultaneously turning the body and hips 180 degrees, and land on this very "point" leg, leaving the other in the air at the same height. So Ermolaev managed to roll around his own leg twice!

The frenzied stress that Yermolaev subjected himself to could not but leave consequences - at the age of 27 he received such a serious injury that doctors barely saved his leg. I had to forget about invention - since 1937, the artist danced mainly mimic roles. And time was not conducive to experiments - on the Soviet stage, the type of performance-drama was firmly established, in which there was no place for virtuoso dance. The next rise in male writing came in the very 60s that brought worldwide fame to Soviet ballet.

Triumph of the trick

Ermolaev's class became a laboratory for the generation of sixties artists: Maris Liepa, Vladimir Vasiliev, Mikhail Lavrovsky, Yuri Vladimirov.