How to river dance

Learn to Riverdance in two weeks? No sweat – The Irish Times

Sweating and cursing, I slump to the floor and stare longingly at my handbag, which I know contains a bottle of ice-cold water and a bar of chocolate. The blisters on my feet are aching, but I know I have to dig deep and summon the energy to pick myself up and start again. As I struggle to my feet, Bill Whelan’s familiar music blares through the speakers. I lift my head, stand tall, and for what feels like the 100th time, begin dancing.

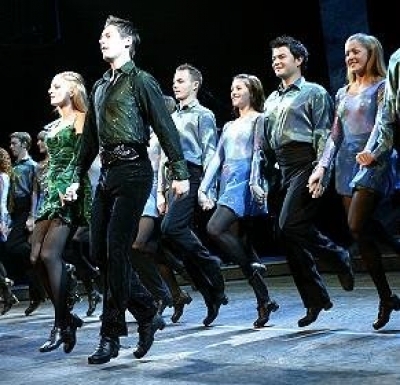

When asked if I'd be interested in learning the steps for Riverdance, I agreed without question. I'm not a dancer. As a child I used to traipse to the school hall once a week to learn my h-aon, dó, trís with the rest of my runner-wearing classmates. None of us was destined for dancing fame, but from the enthusiastic girls in the front of the class to the grumpy boys shuffling at the back, we all jumped around and stretched our limbs.

Years of primary-school dancing lessons may not have sent me straight to the stage, but it did instil rhythm. During my teen years I developed these skills by dancing the familiar Ballaí Luimní in school halls in the west, desperate to impress those strapping young Irish College lads.

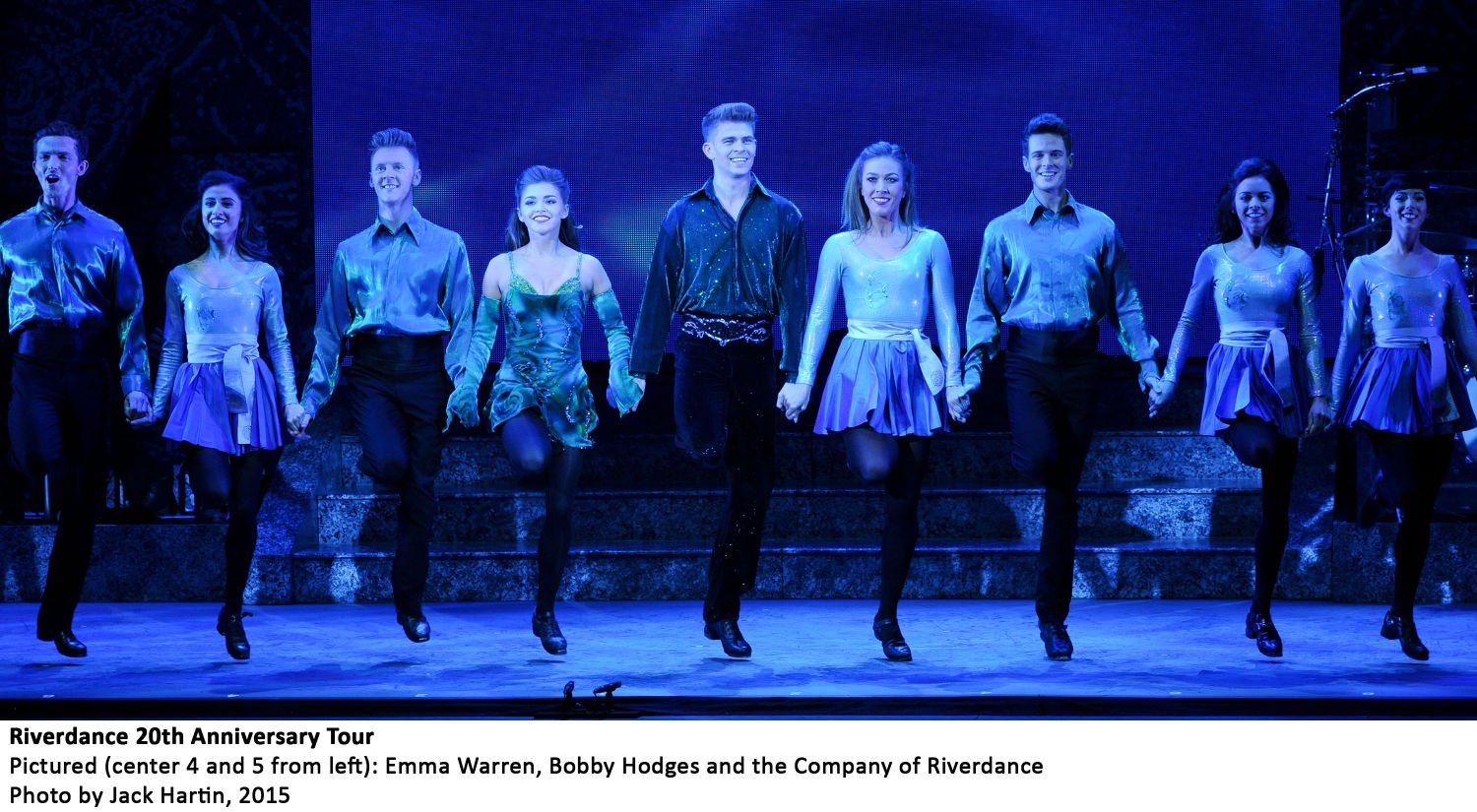

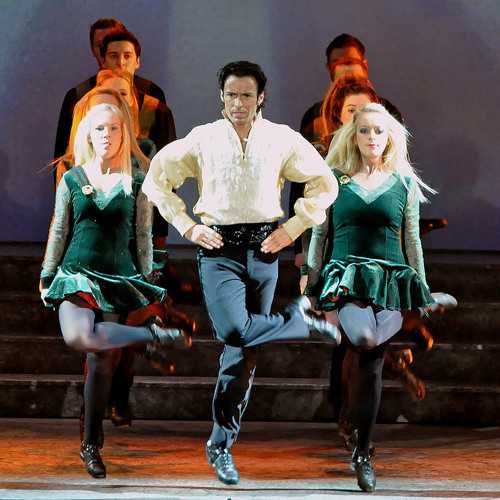

Sorcha Pollak and Pádraic Moyles. Photograph: Alan Betson

That I'm not a dancer becomes quite apparent from the moment I meet Pádraic Moyles, associate director and principle dancer of Riverdance and my trainer for this experiment. He is exactly how I imagine a professional dancer to be: he's fit, lean and moves in a way my body refuses to imitate.

READ MORE

As a small boy, Moyles would watch and take part in the set-dancing sessions his parents held in the family home every Friday. When he was nine his family moved from Dublin to New York, where he began dancing with the teacher Donny Golden.

Sorcha Pollak has 2 weeks to transform herself into a Riverdance dancer ...can she do it? Video: Darragh Bambrick / Daniel O'Connor

“I didn’t like dancing at all,” he says. “It was getting in the way of football and basketball and all those American sports that I was starting to get into.”

“It was getting in the way of football and basketball and all those American sports that I was starting to get into.”

However, at 17 he skipped school to travel to Boston for an audition with a new Irish dancing show. Within a few months he was finished high school, and in November 1997 he began dancing with Riverdance.

“In one sense it’s an addiction for me now,” he says. “I absolutely love it and there is nothing like feeling the applause and the appreciation of a crowd at the end of the night.”

Twenty years later

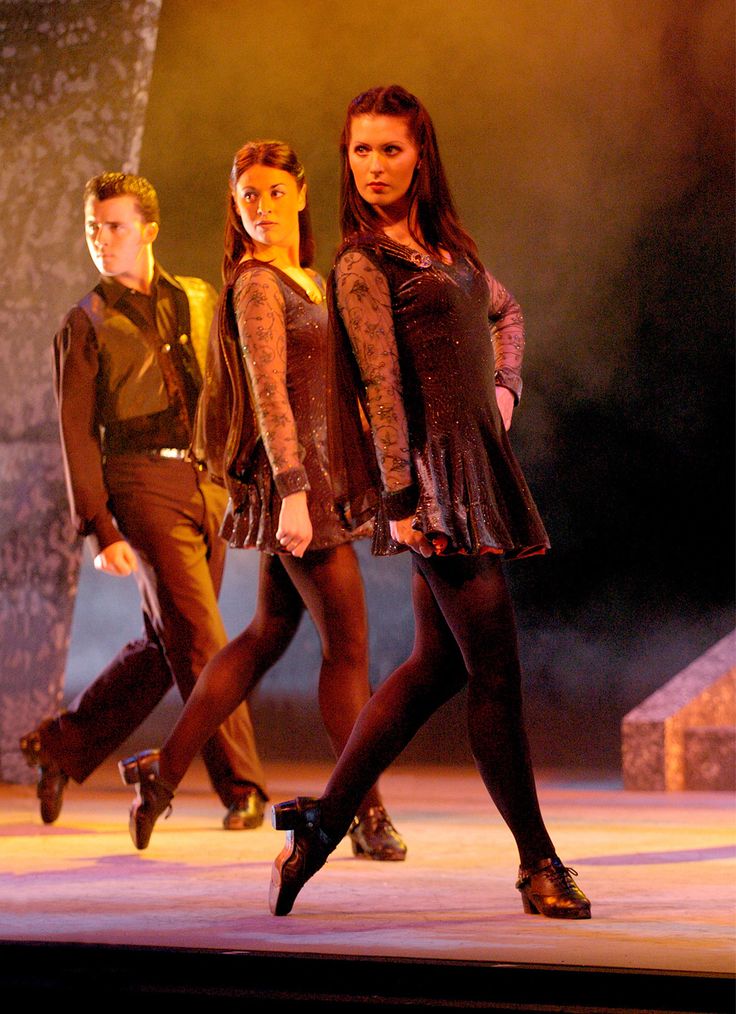

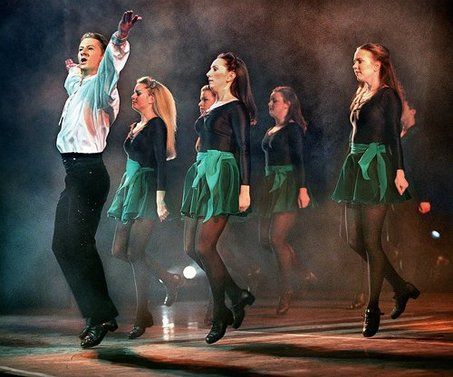

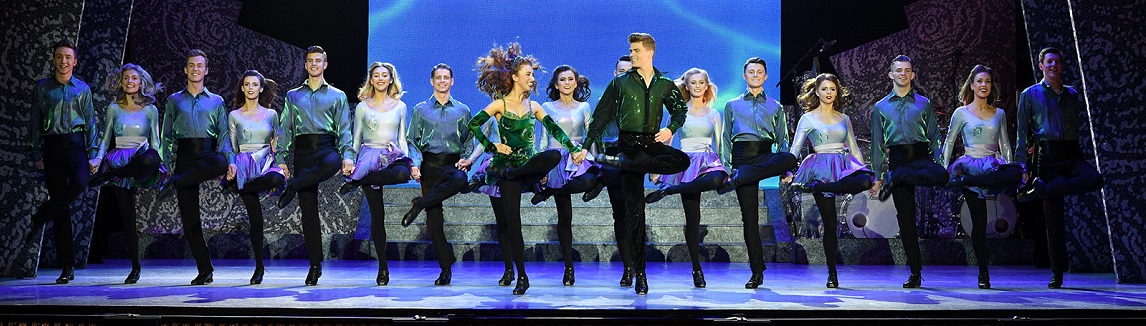

Riverdance is celebrating its 20th anniversary since it was first performed as the interval act at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1994. Two decades later the show has been seen by more than 25 million people in 46 countries across the globe.

I have often wondered what dancing in front of an international audience would feel like. As I turn up for my first class, my enthusiasm to learn masks my panic.

I imagine my new teacher is expecting a dancer more like the attractive colleagues who accompany him on stage, dancing the steps with make-up and hair perfectly intact. Sadly that’s not how I look as I grapple with the ridiculously high-speed choreography. Each step is demonstrated with mesmerising speed and dexterity. I, on the other hand, trip and sweat my way through each afternoon.

Sadly that’s not how I look as I grapple with the ridiculously high-speed choreography. Each step is demonstrated with mesmerising speed and dexterity. I, on the other hand, trip and sweat my way through each afternoon.

However, despite the countless falls and inability to pick up seemingly simple steps, I emerge from each rehearsal invigorated. Dancing has the ability to clear your mind of all worries and fears. It requires that you focus 100 per cent on the movement of your body, leaving no time to stress over picking up the shopping or meeting a deadline.

One hour rehearsing also leaves you with an indescribable hunger. As I imagine the giant plate of pasta I will prepare post-rehearsal, Moyles tells me he tends to eat high levels of protein to maintain his strength.

“Most mornings when I wake up it’s oatmeal and egg whites with some honey. For lunch I try and eat bigger because I like to feel light going on stage and have two chicken breasts with some broccoli.”

Suddenly I can no longer justify that metre-long baguette I hoped to buy on the way home. “Don’t worry”, he adds, “I love a chocolate bar every now and then.” I breathe a sigh of relief.

“Don’t worry”, he adds, “I love a chocolate bar every now and then.” I breathe a sigh of relief.

Dancers lose an average of 5lb of water weight during every performance of Riverdance. "In China we lost about 15lb," says my lean but not mean trainer. "We couldn't find the right foods and none of us were properly prepared for the culture shock."

I empathise with those dancers, not the pounds but the water weight. I don’t think my skin has ever excreted as much fluid as during the intense rehearsals.

After 17 years dancing, Moyles says that eight shows a week, often for 52 weeks a year, is exhausting. He tells me about the challenges of being on the road for months, living out of a suitcase and searching for a launderette in China.

"There are certain territories that are easy to tour, like the United States and Europe, but then there are other places that are extremely difficult, like Asia, and China in particular."

However, it’s not all sweat and blood on tour. When 18-year-olds begin dancing with the show straight out of school, they soon learn that their pay cheques won’t fly straight out the window.

When 18-year-olds begin dancing with the show straight out of school, they soon learn that their pay cheques won’t fly straight out the window.

“We have no rent and no bills. Nowadays the most people have is a mobile phone bill,” says Moyles.

Retirement age

As my bones begin to ache after an hour of rehearsing, I ask him what the retirement age is for dancers. Michael Flatley (55) is still dancing, he tells me, as is Donny Golden (61).

“You’re never too old to dance,” he says, as I strap on my black, hard-soled dance shoes for the first time. “You grow old because you don’t dance. The day I don’t dance is probably the day I’m going to become old.”

Relearning to dance reawakens the 10-year-old inside me. Somehow, in the space of two weeks I am transformed from a very self conscious novice into a toe-tapping Riverdancer.

Sadly, the sweaty hours I have spent in the studio on the banks of the Liffey may not, as I secretly dream, lead to a career in performance. However, they remind me of the importance of embracing my creative inner child.

However, they remind me of the importance of embracing my creative inner child.

Bring on those west of Ireland céilís: the boys will be only dazzled by my dance skills in the halla.

Riverdance returns to Dublin for a summer season at the Gaiety Theatre from June 23 to August 31

Once-Banned Irish Dance Style Is Back

They danced without music; instead the percussion of their shoes marked the rhythm.

Jimmy Hickey’s slender feet lightly tapped the cold stone of the cottage floor, his knees bent with spritely steps that belied his 80 years. Jonathan Kelliher danced in unison at his side, twisting his ankles, clacking his heels and memorizing sequences to a dance that was once banned from Ireland’s dance halls and competitions.

This is Munnix, a percussive style from County Kerry, and is down-to-the-ground and spacious in rhythm — a contrast from the flying batters, rapid-fire steps and ramrod-straight postures that are usually associated with modern Irish dance.

“You’re telling a story with your dancing, you are,” says Hickey, knocking off some quick raps of his toes. “Parts of the dance are slowing down, but the music follows you. The modern dancing today, you don’t know whether they’re playing a jig, a reel or a hornpipe because they stunt the music so much,” he says.

“Nothing against modern dancing,” says Kelliher, 50, a dance master and the artistic director at Siamsa Tíre, the National Folk Theatre of Ireland. “But the older style has space and movement within the beat and rhythm. Just listen to the difference between the two — they’re completely different.”

Munnix dance once thrived in the wild countryside of southwest Ireland, despite a ban by the formal world of Irish dancing. Its snaking ankles and loose arms were considered a threat to modern Irish dance but the defiant dance masters in farming communities kept it alive by traveling from parish to parish and teaching it during long winter nights.

Hickey had inherited intricate moves from the dance masters as a boy in the 1950s and soon began teaching them in local schools. Kelliher learned it from Hickey when he was 6 and joined Siamsa Tíre as an adult to become the next generation’s champion of Munnix.

Kelliher learned it from Hickey when he was 6 and joined Siamsa Tíre as an adult to become the next generation’s champion of Munnix.

Despite decades in the classroom, Hickey’s more-difficult Munnix repertoire could easily have been lost. While he had devoted himself to teaching the Irish dances of all forms, he had never passed on his most complicated Munnix steps. However, the pandemic has given this unusual Irish dance an unlikely boost. When schools shut their doors in 2020, Hickey was forced to cancel dance classes for the first time in 68 years as a teacher. Not one to sit idle, once government restrictions relaxed, Hickey started meeting Kelliher at a small, white cottage in the village of Finuge every Thursday to pass on his most complicated, and coveted, steps of this almost-forgotten Irish dance. However, through weekly meetings at the cottage with Kelliher, Hickey remembered elaborate sequences, which turned out to be a silver lining in a difficult time.

Irish dancing was once as varied as Ireland’s accents. Each region had its own interpretation of step dance. Munnix dates back to at least the late 1700s and is named after Jeremiah Molyneaux, a man locally known as Jerry Munnix. Molyneaux lived in the early 20th century but was so inventive in choreography and prolific in teaching that the style got named after him and became popularized during an age when local dances in Ireland were disappearing across the country.

Each region had its own interpretation of step dance. Munnix dates back to at least the late 1700s and is named after Jeremiah Molyneaux, a man locally known as Jerry Munnix. Molyneaux lived in the early 20th century but was so inventive in choreography and prolific in teaching that the style got named after him and became popularized during an age when local dances in Ireland were disappearing across the country.

When Molyneaux was a boy, traveling dance masters taught everywhere from kitchens to crossroads, and on anything, including table tops, half doors, barrel tops, even anvils. Many also offered lessons in deportment, fencing, and the martial art of stick fighting. They had regular circuits and stayed with a family for weeks before moving on to the next parish.

But this system was threatened from the very people who wanted to safeguard Irish dance and identity. During the late 1800s, a national movement known as the Gaelic revival swept across Ireland in a push against British occupation. The British had stripped Catholics of their rights, land and culture through laws forbidding land ownership and self-rule. British policy also portrayed Gaelic culture as backward and linked to poverty.

During the late 1800s, a national movement known as the Gaelic revival swept across Ireland in a push against British occupation. The British had stripped Catholics of their rights, land and culture through laws forbidding land ownership and self-rule. British policy also portrayed Gaelic culture as backward and linked to poverty.

Hence, when the idea of the nation-state, defined by a shared ethnicity, language and culture was spreading across Europe, Irish leaders recognized that pride in Gaelic culture could help lay a foundation for independence. Douglas Hyde, who went on to become the first president of the Republic of Ireland, had warned in 1892, “I wish to show you that in Anglicising ourselves wholesale we have thrown away with a light heart the best claim which we have upon the world’s recognition of us as a separate nationality.”

Cultural leaders sought to define and promote a distinct Irish identity by fostering the Irish language, sports like hurling and Gaelic football, literature and the arts. Hence, dance became an integral part of the Irish identity.

Hence, dance became an integral part of the Irish identity.

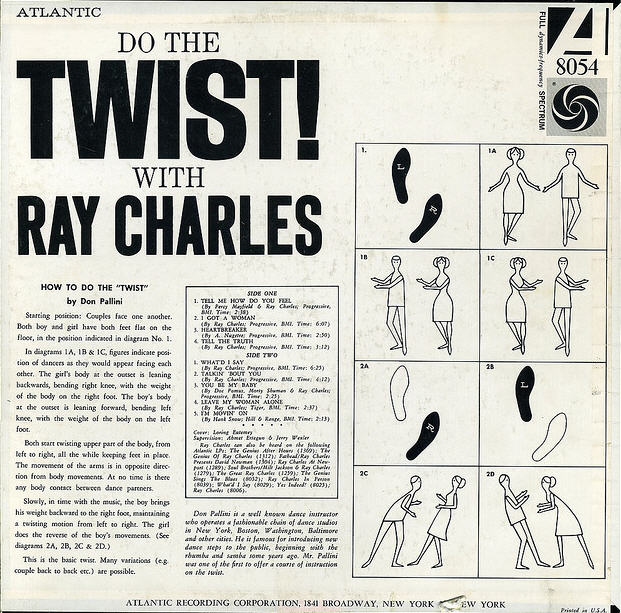

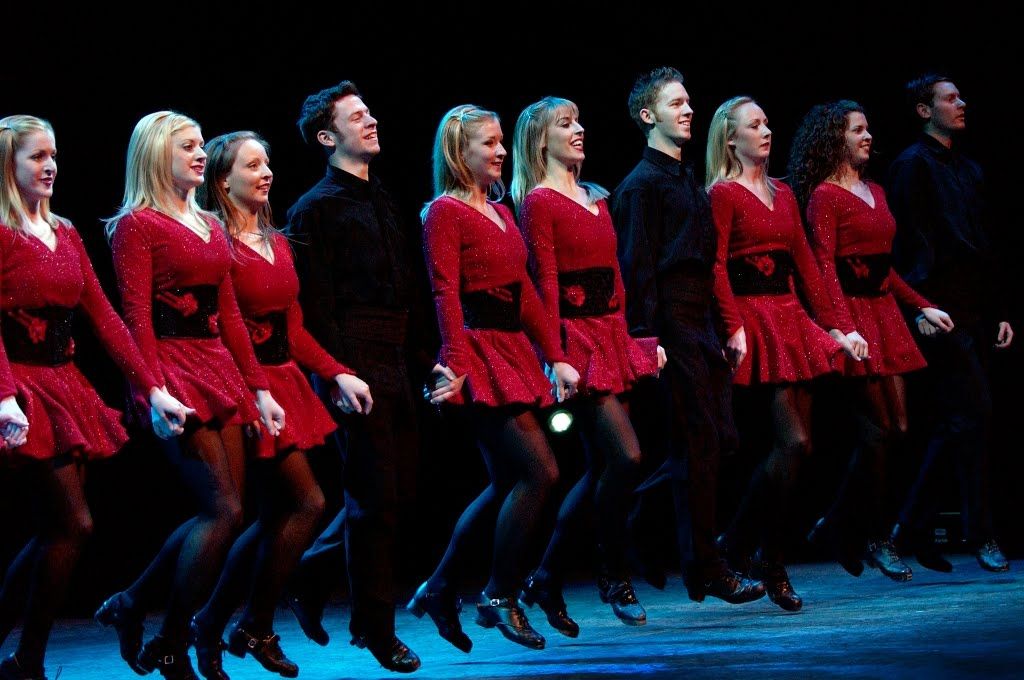

Following the partition of Ireland in 1921, when the northernmost six counties became Northern Ireland and the remaining 26 the Irish Free State, the Gaelic League formed the Irish Dancing Commission to preserve Irish dance by standardizing its instruction and grading. This eventually molded Irish dance into the form globally loved today, with swift footwork and athletic leaps popularized by Riverdance, a touring theatrical show.

However, the well-intended commission also pruned its repertoire from anything considered foreign and regulated dance to such a degree that it extinguished distinctive local dances. The commission considered rural dance masters to be inferior and anyone who taught outside its repertoire was barred from the organization, its competitions and dance halls. This created two systems: the long-established rural approach and a formal urban one.

Not everyone agreed with this method. Long before the foundation of the Irish Dancing Commission, the Irish writer and nationalist Padraig Pearse, a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising, had warned that Irish dances belonged to “cottage fires” and “to transplant them was to kill them. ”

”

In the countryside, dance cemented social connections. At weddings, country dances, and fairs, many a match was made on the dance floor but, as Pearse recognized, dancing at home by the heat of the hearth was equally important to country life.

Traveling dance masters would stay with a host for several weeks. On long winter nights, people of all ages from the surrounding patchwork of tiny fields gathered weekly at the host’s house. The dance master, accompanied by local musicians, taught children the jib, the treble reel and the hornpipe in the sitting room. As the fiddle or melodeon played, adults gathered in the kitchen, engaged in storytelling, performing dance sets and catching up on news about the neighbors, the harvest and the price of livestock. They often danced until dawn, when it was time to go home and milk the cows. Many rural dance styles survived into the 1960s and at fairs, and the region of each dancer could be identified by their movements.

However, slowly and steadily, the variety vanished. But Munnix continued to flourish in the southwest, thanks to determined dance teachers and a countryside culture where few felt obligated to adhere to the top-down regulations from the cities. County Kerry was remote and poor, with a rural population dependent on farming. Well-intended ideals and dance regulations from a distant Dublin felt irrelevant.

But Munnix continued to flourish in the southwest, thanks to determined dance teachers and a countryside culture where few felt obligated to adhere to the top-down regulations from the cities. County Kerry was remote and poor, with a rural population dependent on farming. Well-intended ideals and dance regulations from a distant Dublin felt irrelevant.

Molyneaux, who was at his peak during the standardization of competitive Irish dance, had had little interest in joining the commission. Neither his livelihood nor social standing depended on it, and he enjoyed great respect and status. It was an honor in the community to claim him as a teacher. Additionally, north Kerry dancers practiced an inventive style that required spontaneity and creativity rather than following rigid choreography.

Molyneaux is celebrated as the last of the traveling dance masters. Born in 1883, the youngest of seven, he in 1903 began a teaching career that spanned half a century. He was 4 feet, 11 inches tall and is remembered as dapper, clean-shaven and a lean person “with small, neat feet. ” He was known to be better dressed than the gentry, and it was considered an honor to play host to his circuit in north Kerry villages.

” He was known to be better dressed than the gentry, and it was considered an honor to play host to his circuit in north Kerry villages.

After spending six weeks in a village, Molyneaux held a benefit to showcase his students’ skills and then walked or rode to the next parish. Many students were farm workers, so rainy winter nights were good for business. During the summer harvest season, Lent, Advent or periods when the parish priest denied permission to teach dance, Molyneaux turned to other trades, including carpentry and cobbling. He also bred canaries as a hobby. After Munnix died in 1965 at age 83, he was buried with his best pair of dancing shoes.

Jack Lyons, a student of Jeremiah Molyneaux Date uncertain / Siamsa Tire / New LinesToday, the Irish Dancing Commission allows competitions to include set dances with regional choreography, like the Priest in His Boots (West Limerick and County Clare) and Molyneaux’s own choreography for The Blackbird. But with national standardization, the local vernacular is easily lost.

“In the Irish dance world what matters is getting the step but not the style,” says Catherine Foley, who taught ethnochoreology and Irish traditional performance at the University of Limerick for more than 20 years. “In one way it is marvelous that Munnix is recognized and that people from the organization are dancing the steps, but it would be lovely if they knew the aesthetic and style as well and that doesn’t happen overnight.”

Foley grew up in County Cork, immersed in traditional Irish music, classical music and step dancing. In the early 1980s, she spent three summers documenting traditional Irish music, song and dance in County Kerry for the archives of Muckross House in Killarney. She found Munnix to be popular in north Kerry among older dancers, who welcomed Foley and her colleague into their homes to teach jigs, hornpipes, treble reels and the stories behind these dances.

“Dance was gradually becoming institutionalized and popularized through competition, whereas in this little enclave in north Kerry, I still had older people who had stories about their dancing and dance was very much part of them,” Foley says. “They wouldn’t have traveled internationally like a lot of people do today, most of their lives would have been in Kerry, and a lot of them would have been tied up with farming or helping farmers. So to me it was a snapshot into a particular way of life,” said Foley, who later wrote her Ph.D. dissertation on traditional step dancing in north Kerry and the creativity of Munnix dancers, which became the inspiration for her book “Step Dancing in Ireland.”

“They wouldn’t have traveled internationally like a lot of people do today, most of their lives would have been in Kerry, and a lot of them would have been tied up with farming or helping farmers. So to me it was a snapshot into a particular way of life,” said Foley, who later wrote her Ph.D. dissertation on traditional step dancing in north Kerry and the creativity of Munnix dancers, which became the inspiration for her book “Step Dancing in Ireland.”

“Everything was about rhythm, about the relationship between the dancer and the ground, and the sound being created. ’Twas almost like a relationship with the land,”she said. It was as though each dancer was creating their name on that ground on which they danced and it was almost trapping the notes of the tune under their feet. Each step and movement is a statement about who they are. They were from north Kerry, and it was a style of dance that emerged from an agrarian, rural community.

For Hickey, variety and improvisation are the heart of Munnix — nobody danced like the dancers in County Kerry.

“I’d say we were the only part of the country that was able to dance like we could,” Hickey says. “Dancers were all trying to outdo each other and that’s what makes north Kerry step dancing so intricate you see, no two steps are alike. It’s complicated but you get so used to it, ’tis easy to make steps up.”

“But ’tis not so easy to make good ones,” Kelliher says.

As is often the way in north Kerry, genealogy is important in the Munnix dance tradition. Dancers can recite the name of their teacher’s teacher, and the teachers who came before them, like a family tree. Each master left their own inheritance of steps by which they are remembered.

Hickey began learning from Liam Dineen at age 7. Dineen had collected his repertoire from Molyneaux during the latter’s frequent visits to the Dineen family pub. “They were possessive with their steps, long ago, they were,” Hickey said. “But Liam had the pub and that’s where he would get most of the dance steps, you see. Liam was like Jerry — he was a master himself and his brain was always working to improve, all the time. ”

”

By age 12, Hickey was teaching, and by age 15, he won the cup at the cliffside village of Ballyheigue against grown men who had come from as far as Dublin to compete for handcrafted silver medals. “I was always a jigger,” Hickey says. “I’ll never forget: There was a lady down from Limerick city, she was judging. She was a heavy lady and when I got up on the stage to dance, she put down the books, she sat back like that and folded her arms with a big smile on her face, and I danced.”

Hickey’s reputation spread, and parents began to drop into his father’s cobbler’s shop in the town of Listowel to inquire if he’d teach. Teachers were equally keen to have Hickey teach at their schools but it was the early 1960s, and parish priests did not permit dance classes during school hours.

“You’d knock at the door and the priest would come out and say, ‘What do you want?’” Hickey remembers. “I’d say, ‘Well, look, would you mind if I taught dancing in the school?’ The door was banged in your face. ” This changed with a letter of invitation from a teacher in Ballyloughran. “ ’Twas an honor, so I went,” Hickey says. “The thing is, when you went into one school, the other schools in the parish wanted you as well.”

” This changed with a letter of invitation from a teacher in Ballyloughran. “ ’Twas an honor, so I went,” Hickey says. “The thing is, when you went into one school, the other schools in the parish wanted you as well.”

However, when the coronavirus started, the dancing stopped, Hickey says.

“There’s a huge void of two years for young children who haven’t learned to dance at all,” Kelliher agrees. “We’re seeing that knock-on effect now. We’re not getting the numbers we’d normally get for auditioning.”

Adult classes for Munnix dancing resumed at Siamsa Tíre in the town of Tralee last November. Kelliher opened with a crash course on its history and a piece of etiquette: Dance with respect for the musicians; you are not the star of the show.

Kelliher ended the winter lessons with a sequence from 1918, recorded decades later by a dancer who recalled how he learned the step at a time when friends and relatives were sick with the Spanish flu. In Kelliher’s own class that night, one student was absent with the coronavirus, another cocooning before a wedding.

But even now, the dance goes on.

Shooting plans A girl in a national costume is dancing on the banks of the Ural River, Salavatsky district, a girl...

Uralgirldanceriverwatershorestonesforestgrasstreesnature

Similar shooting plans

HD 00:34

A girl in a national costume dances on the banks of the Ural River, Salavatsky district, a girl...

HD 00:56

A girl in a national costume dances on the banks of the Ural River, Salavatsky district, a girl...

HD 00:42

Girls in national costumes rehearse on the banks of the Ural River, Salavat district, girls...

HD 00:08

Girls in national costumes rehearse on the banks of the Ural River, Salavat district, girls...

HD 00:18

Girls in national costumes rehearse on the banks of the Ural River, Salavat district, girls. ..

..

HD 00:36

A girl in a national costume is dancing on the river bank, in the background someone is throwing stones into the water...

HD 00:16

Girls in national costumes rehearse on the banks of the Ural River, Salavat district, girls...

HD 00:27

Girls in national costumes rehearse on the banks of the Ural River, Salavat district, girls...

HD 00:59

Girls in national costumes are rehearsing on the banks of the river, a Ural rider, Salavatsky, is passing by ...

HD 00:51

A girl in a national costume dances on the banks of the Ural River, Salavatsky district, girl, face,...

Similar Newsreel

folk rites 1975

Village on bank river . Boat on shore . Someone is swimming near the bridges. Overgrown with grass river bank . The male

According to the USSR No. 110 1973

Foreigners go down the ladder. Japanese in national costumes . Types of Moscow. The building of the Moscow City Council. Chairman

Soviet Ural No. 24 1986

ensemble in folk costumes . Emblem "Festival folk art ". Women of ensemble in folk costumes

Emblem "Festival folk art ". Women of ensemble in folk costumes

Russians No. 5 1991

Butyrev. Pier in Syktyvkar. Motor ship on river . People under an umbrella go down. Passengers in bus. Aerodrome

Hadris 1979

dance group at national suits . The artists of the ensemble perform dances of warriors. The faces of the artists

Dubovskaya matryoshka 1978

painting, participant folk festivities in national Mari costumes on glade in forest . Ready nesting dolls

Panorama No. 7 1987

Crowd. Girl in Russian folk costume dress and headscarf. On stage Russian folk orchestra instruments:

The most beautiful Ural 1994

Beautiful nature Ural with rich flora and fauna. Recently on Urals appear more and more districts with the status of national park .

Recently on Urals appear more and more districts with the status of national park .

Eclair No. 28761 1930

holiday in south. Local band plays folk dance on drums and flute. Young men in white costumes dance

Russians No. 20 "Tuvans". 1992

Buddhist monks. People are praying. An eagle soars in the sky. Man in national costume plays and sings, children hold

Similar photos of

Participants of the Tatar national holiday Sabantuy in national costumes in the village of Arsk. Sabantuy

Sabantuy

Meeting of guests of the Tatar national holiday Sabantuy at the Tasma stadium in the Moskovsky district...

Batyr of the Tatar national holiday Sabantuy of the village of Charlerama, Sarmanovsky district

Representatives of the collective farm "Chulpan" of the Almetyevsk region during the opening of the Tatar...

President of the Russian Federation Yeltsin Boris Nikolayevich (in the center), Head of the Administration of the Arsky...

Girls of the village of Turaevo near the spring "Tau asty" (Podgorny spring) of the Mendeleevsky district of the Republic ...

Head of the administration of the Rybno-Sloboda district Khairullin Ravil Garifullovich (2nd from left) with. ..

..

Young participants in the competitions in the Tatar national wrestling on the belts "kuresh" during the Tatar...

Batyr in Tatar national belt wrestling "kuresh" Fashhetdinov Yahya Nailovich with a prize...

Opening of Tatar national holiday Sabantuy in Yutazy village.

Opening of Tatar national holiday Sabantuy in the city of Almetyevsk.

Horse races during the Tatar national holiday Sabantuy in the village of Muslyumovo.

Procession of participants during the opening of the Tatar national holiday Sabantuy in the city of...

Participants of the contest "Running in bags" during the Tatar national holiday Sabantuy in the village. ..

..

Participants of the contest "Running with a yoke" during the Tatar national holiday Sabantuy in the village...

Our site uses cookies to personalize services and user experience. By continuing to work with the site and / or its services, you accept the User Agreement, Privacy Policy and Cookie Policy.

OPEN LOOK 2014: wild river of dance

- Theater

-

From June 28 to July 11, a large-scale event in the world of plastic theater takes place in St. Petersburg - the modern dance festival OPEN LOOK 2014, at which dancers from all over the world wanted to perform. The most famous choreographers will present their programs to the public for several days and hold many master classes for everyone.

One of the foreign guests of the festival was Liz Aggis, a dancer and choreographer from the UK, a member of the team of creators of the British Film Dance, shown on the New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theater on June 30th. Movie Dance is a selection of five short films designed to educate viewers about plastic cinema: Beach Party Man, Diva, Beethoven in Love, Motion Control, Bassini.

Frankly, "British Film Dance" is a bold and rather original project. Most likely, people who are not directly immersed in the world of modern dance will find it rather difficult to be imbued with its aesthetic ideology and understand the meaning inherent in all film fragments. The reason for this is that there was no dance in the traditional sense - Liz Aggis, along with Billy Cowie and Joe Murray, demonstrated a spectacular, but rather specific choreography, the idea of which may not be perceived by everyone in the right way. It is no secret that movements can sometimes reflect an idea and feelings much more fully than they could be said in words. However, in order to achieve understanding, this expressive plasticity must be understood by everyone, and not by a limited number of initiates. For those viewers who are not well versed in the field of modern dance trends, "Kinotanets" may seem strange and even a little frightening. But one cannot fail to note the humor and love with which the group of choreographers approached the production of the film, for which they really deserve audience recognition.

However, in order to achieve understanding, this expressive plasticity must be understood by everyone, and not by a limited number of initiates. For those viewers who are not well versed in the field of modern dance trends, "Kinotanets" may seem strange and even a little frightening. But one cannot fail to note the humor and love with which the group of choreographers approached the production of the film, for which they really deserve audience recognition.

On the same day, another event took place, perhaps the most important in the entire educational program of the festival. Eminent and talented teachers from different countries gathered on the same stage to perform in "TEACHER'S GALA" - a kind of self-presentation designed to show the public all their dancing talents and invite them to further interaction at master classes. One by one, the dancers - Ivan Perez, Juri Dubbe, Pascalina Noel, Anna Ozerskaya and others - captivated the audience with their bright individuality and freedom of movement. However, some of them were not limited to only movements, using speech as well - for example, Seke Chimutengwende from the UK, who literally captivated the guests of the festival with the energy and some madness of his words.

However, some of them were not limited to only movements, using speech as well - for example, Seke Chimutengwende from the UK, who literally captivated the guests of the festival with the energy and some madness of his words.

So unusual, so unlike each other choreographers who speak different languages, but are carried away by the same body language. They came to St. Petersburg to teach us this special dance philosophy. If you are already passionate about the world of dance, if you strive to express feelings with your whole body, and not just with words, you simply do not have the right to miss at least one master class. But if you are a beginner, if you just want to learn how to move beautifully, then you better think ten times before throwing yourself headlong into the bright stream of the OPENLOOK Dance Festival - after all, as befits stormy water, it will absorb all the inexperienced, and if it doesn’t, it will forever discourage you from repeating this experiment.