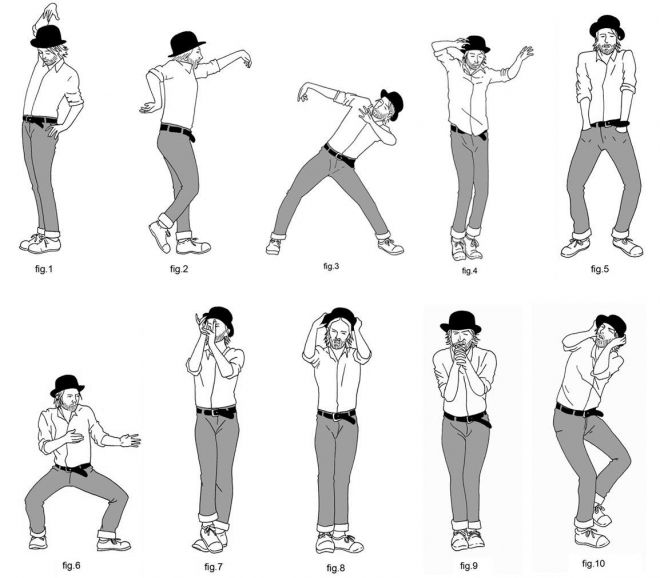

How to polynesian dance

‘It’s a revenge’: the global success of the Tahitian dance that Europeans tried to outlaw | Tahiti

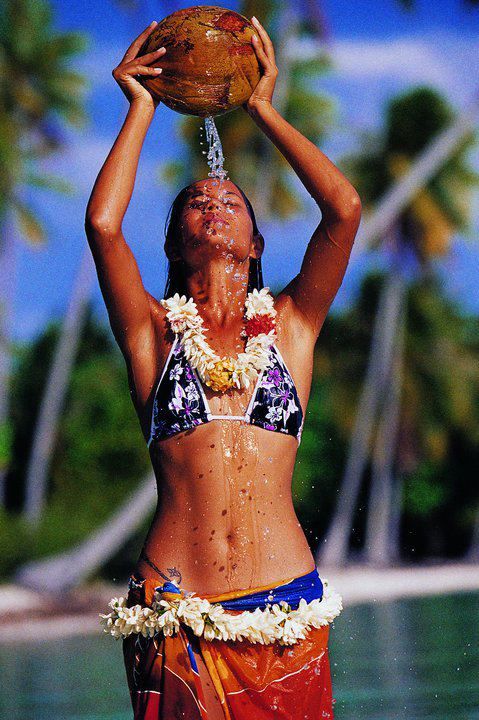

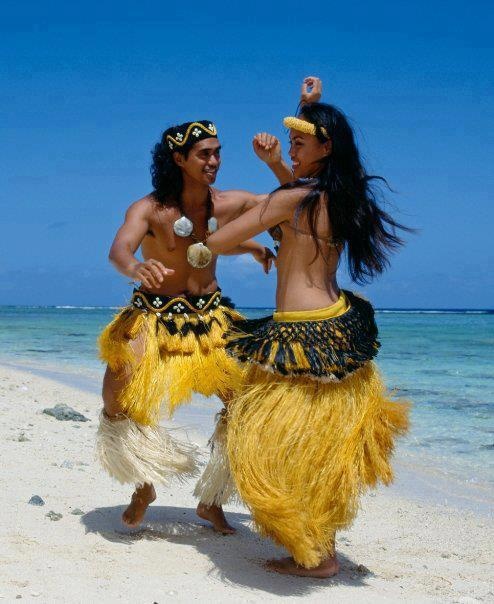

Wearing intricate costumes made of plants and adorned with tropical flowers, the women look spectacular. While their torsos remain completely still, somehow, impossibly, their hips are moving in circles so fast it’s almost a blur.

These women are performing traditional Tahitian dance, or Ori Tahiti, in Tahiti’s annual cultural festival, the Heiva. And they’re not alone. Thousands of women across the globe, from Mexico to Japan, are doing it too.

According to a report published by the French ministry of culture in 2017, there were more than 12,000 Ori Tahiti dancers in the United States and more than 10,000 in Latin America. In Japan, the movement has attracted 25,000 dancers and is projected to grow to 500,000 by 2027.

Ori Tahiti is a broad term that encompasses the many traditional dances native to the island of Tahiti, performed by both men and women. The most well-known is the ote’a, a very fast, hip-shaking dance performed by women. Another is the aparima, which features slower, more graceful body movements. Both dances are difficult to master, but absolutely captivating to watch.

“The dance itself, in my eyes it is the most beautiful, powerful, sensuous and expressive,” says Tumata Robinson, a renowned Tahitian choreographer, costume designer and founder of acclaimed dance group Tahiti Ora.

“I think Ori Tahiti is very complete, you know. It’s fierce, but also elegant and powerful, graceful, feminine when we dance. I feel beautiful [when I dance],” says Moena Maiotui, one of Tahiti’s most beloved professional dancers, who has travelled around the world performing, teaching Ori workshops, and sharing Tahitian culture. YouTube videos of her dancing, both solo and with the dance group Tahiti Ora, have racked up millions of views.

“It’s always good to be on stage and to share the culture and what we love and the passion and also tell the story … with our hands and share this moment with the people who are watching. ”

”

Self-expression and connecting to nature are what Ori Tahiti is about for Rina Hanzawa. Born and raised in Tokyo, Hanzawa discovered Ori Tahiti in her early twenties.

“I went to dance school and I found Ori Tahiti there,” says Hanzawa. “At the time I had no clue about Tahitian culture. But I fell in love with Ori Tahiti when I tried it. The Ori movement was so natural for me – it was just very comfortable to do so I felt a strong connection with it.”

What started as a casual hobby soon became an enduring passion, which led to her competing at a national level.

Hanzawa now lives in Australia, where she has set up her own Tahitian dance school, Tai Pererau, in Sydney’s northern beaches.

“My fire of love towards Tahitian culture will never blow out,” she said.

The dance that sparked that fire, however, was almost extinguished. The arrival of Europeans in French Polynesia, along with their religion and laws, saw Ori Tahiti banned or repressed for close to 100 years.

At the end of the 18th century, dance was banned by European missionaries, who labelled it immoral. Then, in 1819, the Pomare Code, a set of laws laid down by the Tahitian monarchy, forbade traditional dancing outright. In 1842 the French protectorate allowed dancing – but with so many conditions that the practice was still repressed.

It was only in the 1960s that the church began to lose influence and traditional dancing really began to be revived. During this time the first modern dance group appeared on the scene, led by Madeleine Mou’a.

Damaris Caire, author of a book titled Ori Tahiti: Between Tradition, Culture and Modernity, says: “Little by little, by doing dance shows at hotels for tourists, Ori Tahiti became popular – even if the local population initially struggled to accept it.”

By the 1970s, the Tahitian cultural revival was in full swing and from the 1980s onwards Ori Tahiti was rediscovered, reinvented and fully embraced by the local population.

Despite a rocky past, Ori Tahiti has today become a way for Tahitians to connect with their ancestors, their land and their language. It is a celebration of a cultural identity and pride that was almost lost to colonisation. Now, it has become one of Tahiti’s best exports.

Hinatea Colombani, a Tahitian cultural expert and director of the Arioi culture and arts centre, says it is particularly satisfying to see Ori Tahiti become popular in the very countries that tried to stamp the practice out two centuries ago.

“For me it’s a revenge, because they celebrate our culture,” she says.

“Ori Tahiti is for me a freedom. A freedom to move, a freedom for the soul … and a really important way to escape from the everyday and connect to my ancestors and to the tradition.”

This year, the Heiva Ori Tahiti Nui international 2021 – Ori Tahiti’s biggest competition – had to be held online due to the pandemic. However, it still managed to attract competitors from 12 countries and territories, including two new participants: New Caledonia and Switzerland.

Ginie Naea, from France, is a dance teacher at the Te Ori Tahiti school in Geneva. The school has more than 70 dancers, aged between eight and 68. After competing for the first time online in the international competition, they came away with fourth place in a group category and a first place for the solo ote’a – which was danced by Naea.

“It was really a superb experience,” says Naea of the competition. “We danced in front of Lake Geneva and the mountains; it was just magic. The best part of the competition was actually the preparation and team cohesion that it necessitated – a connection that’s created when performing. There is a real bond between Ori Tahiti dancers, a real family that is created around the same passion.

“Ori Tahiti is more than a discipline, it’s a way of life. It’s something that really completes me … an art in which I flourish – as a woman, as a friend, as a mother – it’s really part of my everyday life. ”

”

Polynesian Dances And Chants Explained

What would you do if you had no way to write or record anything in your life? How would you remember anything?

From day to day life to ancestry, we rely solely on the written record to safeguard history. Before the written word existed, cultures found their own ways to preserve their stories so they may survive for future generations.

In the Pacific Ocean, the Polynesian cultures used verbal means to memorialize the events of their lives. Through chants, songs, and dances they created a way to maintain their civilizations and carry their memories through centuries.

Spanning thousands of years, songs, dances, and chants were united in performances using symbolism, intricate metaphors, hidden meanings, and imagery capturing the essence of their world.

There were a variety of verbal and physical combinations used for different occasions and each held a special meaning.

With so many elements that needed to be recorded the recitations and performances were used to track everything from political and social to economic and ecological components.

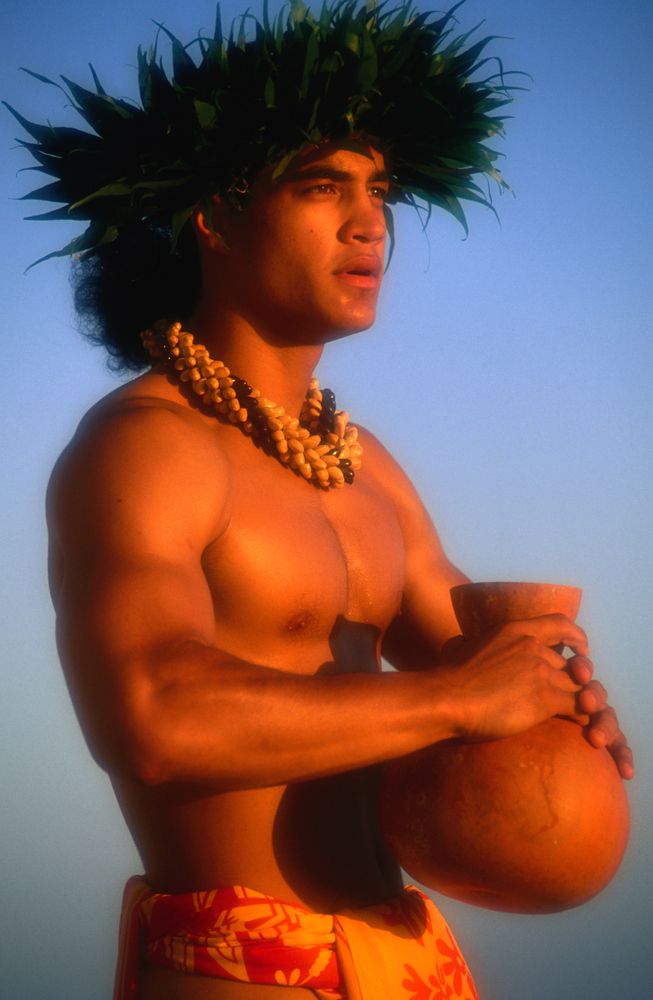

Each island had its own style and vernacular all of which contained reverence to the chiefs, gods, and the birth of the island and its inhabitants.

Family Mana and What Chants Mean

Among families there were genealogical chants which named every ancestor and life event commemorating the family line.

The language of Polynesian culture is very powerful and every word, every name has its own amount of power (mana).

There is careful consideration used to determine the name or word chosen to add to the chant that charted the family lineage. Every new addition would build upon its power.

The longer the chant grew, the more power it possessed which raised the status of the lineage. Every time it was recited, the chant was meant to please the gods.

The actual act of saying the holy chant and naming all of the ancestors gave it more power. It was believed if an ancestry held enough power the family could become god-like.

Chanting was a part of the lifeblood.

Chants were also used as a proof of identity. Those that descended from royalty had to be able to prove it by being able to recite intricate and highly developed genealogical chants.

In aristocratic families, only certain members in positions of power were allowed to learn the chants for the family lineage. Whereas, in families of lower class the first born child had to memorize the family chant.

This meant the eldest spent most of their time studying in order to carry on their family’s ancestry. The family’s fate was upon the first child’s shoulders as they carefully learned the complicated and lengthy chant that captured the history of an entire bloodline.

While each chant and performance was meant to depict and symbolize events within the community or family, it was truly up to the listener to decipher the meaning.

Words and phrases held double meanings. In the Hawaiian Islands commoners were not taught the dual meanings.

Only those of higher class chosen by the chiefs or those of power to receive the simultaneous meanings would understand the metaphors hidden behind the chants and songs.

There was a strong desire to keep their language pure which meant only giving permission to select people worthy of the sacred knowledge to protect its strength and power.

With so many ways to comprehend and translate, it was crucial that those tasked with learning chants did so with the utmost perfection.

Hawaii – Hula

Throughout the Polynesian Islands, the physical act of record keeping varied from one place to the next each with its own unique interpretations and cultural details.

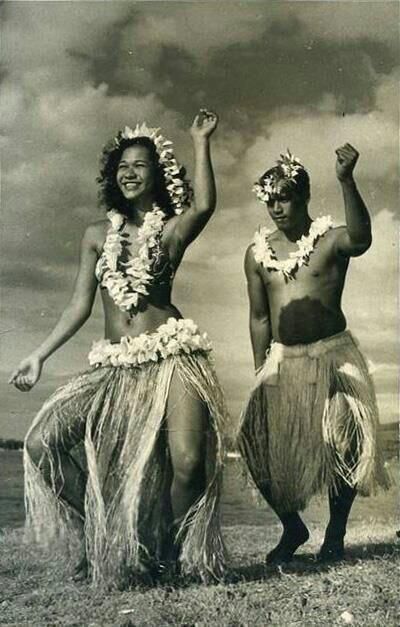

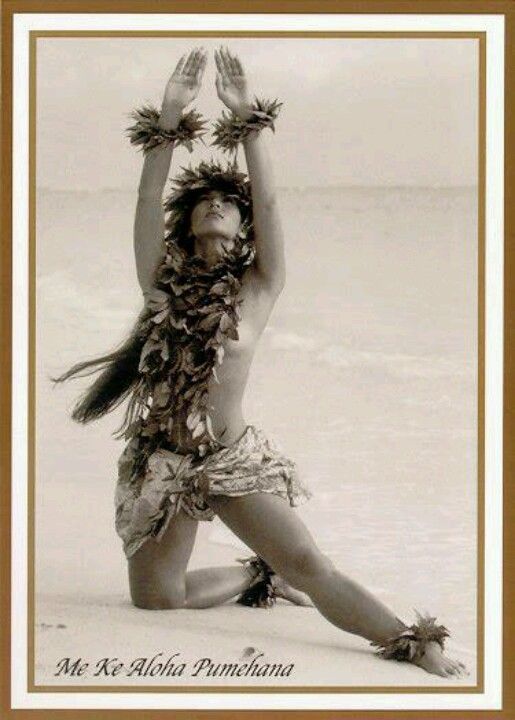

In Hawaii the Hula is one of the most famous forms of Polynesian dance depicting mythological subjects relating to ancestral history and performed in honor of the Volcano goddess.

The slow, smooth, and graceful movements of the dancers were accompanied by solemn rhythmic song and sounds of sharkskin drums and rattles.

The chant known as the mele was also spoken during the performance adding to the overall power and symbolism. Much of this ritual was lost after it was banned in the 19th century when missionaries took over.

Tahiti – Ote

Tahiti had a similar performance known as the Ote which was only performed by men. The swaying hip movements and music all came together to share important stories of the civilization.

Tonga – Lakalaka

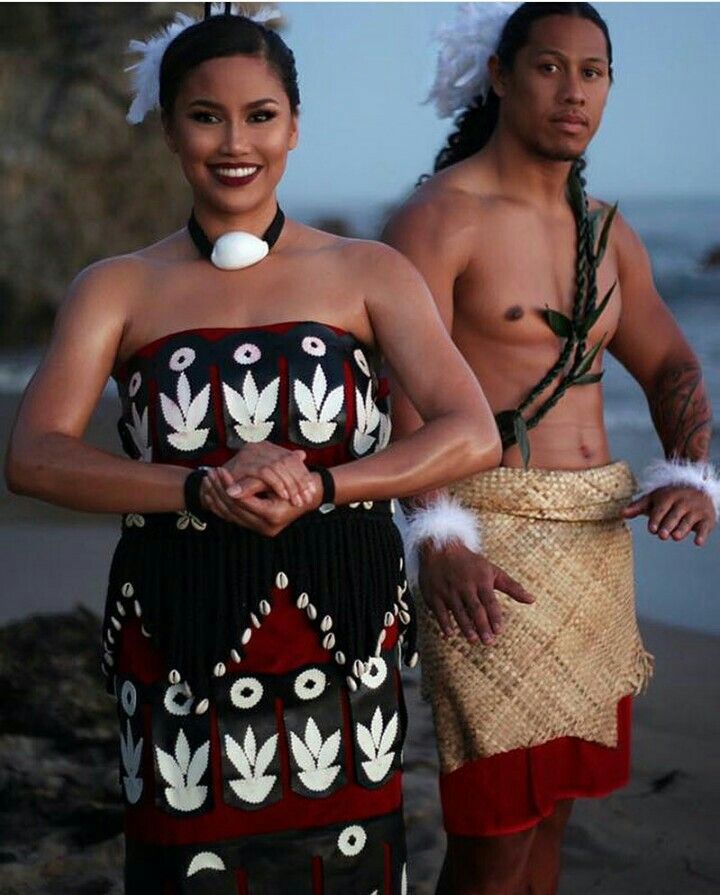

In Tonga and Somoa, the movements in common song and dance were slower but still very deliberate in each motion. The Lakalaka is the most common performance in Tonga with the participants dressed in costume.

Women were graceful and feminine while the men represented the warrior essence. They stood in rows carefully swinging and swaying telling stories with hand movements.

Samoa – Siva

In Samoa, drums fill the background of the interpretive dancing. Sweeping fluid motions were slow but precise as they expressed events through the centuries of their civilization.

There are various types of traditional Samoan dances. The mak Sa’moa is one type, along with taualuga, siva afi, and sasa. There’s also the popular Laumei or Luemei for short as well as Tautasi which have their own unique style to them too!

Fiji – Meke

In Fiji and New Zealand, more lively performances take place. Fiji’s song of celebration known as the Meke is filled with vibrant clapping, dancing, and chanting.

Fiji’s song of celebration known as the Meke is filled with vibrant clapping, dancing, and chanting.

There is also a village communicator that will fall into a trancelike state during the performance, and he will conjure new chanting and dancing that will be added to the next Meke celebration extending its story.

New Zealand – Haka

As for New Zealand, the Haka is an ancient Maori dance which was used on the battlefield as well as when coming together in a peaceful state.

It was a moving display of pride, strength, and unity. The men would violently stamp their feet, stick out their tongues, and slap their bodies in accompaniment of an aggressive chant.

It all came together in a dramatic display that still managed to be a melodious representation of the events that defined the tribe’s history.

These careful considerations and tireless actions meant to preserve these cultures have survived through centuries and land invasions.

While some of the information has been lost, much of what we know about the Polynesian cultures comes from the physical forms of record keeping passed down.

The songs and dancing captures the spirit and energy of the people and the chanting is a collective voice of all the ancestors. They are sacred traditions that have stood up to the test of time proving they are just as powerful as their creators had intended.

Thank you to the Polynesian Cultural Center and Turtle Bay Resort for hosting my visit to Oahu.

Learn about the Polynesian Islands in an interactive and immersive experience the whole family will love at the Polynesian Cultural Center where you can also see, hear, smell and taste a Hawaiian Luau.

Hawaiian hula dances: Studio "Aloha" - training, performances in St. Petersburg. Hawaii. The land where they know how to love: Legendary HAWAIKIA

Can there be a paradise on the "Land of people"? They say yes. They say it exists. I have long heard the legend of the "last paradise" of our planet. That is how this corner is called by those who want to sing it. Ethnographers call it Polynesia, geographers - the islands of the South Seas.

They say it exists. I have long heard the legend of the "last paradise" of our planet. That is how this corner is called by those who want to sing it. Ethnographers call it Polynesia, geographers - the islands of the South Seas.

And the very heart of these places is it, the legendary Hawaii - a semi-mythical country, in which almost all Hawaiian ancient legends originate, and on which all its Gods - Maui, Pele, etc. were born. And from which, according to legends, the first settlers once came to the Hawaiian Islands.

An ethnographer sees Polynesia as gigantic triangle. In its corners there are three islands: on top - Hawaii, on the left (that is, on west) - New Zealand, on the right (in the east) - Rapanui, or Easter Island:

The legend of the "last paradise" took possession of thoughts, fantasy, feelings of millions of people and enveloped Polynesia in many myths, covered it face with countless romantic veils. Yes, Polynesia is beautiful. The sea is there - azure, the sun is bright, the melodies are gentle, and the dances are more temperamental...

The sea is there - azure, the sun is bright, the melodies are gentle, and the dances are more temperamental...

Most researchers in Oceania agree that Hawaii, more precisely, the last Hawaiian, this is Raiatea - amazing in beauty, but a little-known island lying north of Tahiti. Someone, however, says that the heavenly country of Kahiki from Hawaiian legends is Tahiti (this is how the Hawaiians pronounce the name of this island). But be that as it may, these are all islands of one archipelago, which is called the "Society Islands" in French Polynesia, and is located almost in the center of the "Polynesian triangle":

It was from here, with Raiatea, that the “Vikings of the solar sunrise", the greatest navigators of our planet. They didn't populate the continents and, furrowing the seas, like a great poem, they created history.

So, leaning on heavy oars, they sailed for many months to the sound of their songs. From time to time, patches of land came across - uninhabited islands. They are stepped on them timidly, as if touching a dearly beloved woman, and looked for for these islands in the treasury of their language the most euphonious names. And inhabited them until the entire Pacific Triangle became habitable.

They are stepped on them timidly, as if touching a dearly beloved woman, and looked for for these islands in the treasury of their language the most euphonious names. And inhabited them until the entire Pacific Triangle became habitable.

In Polynesia, more than anywhere else, it is myths and legends hide numerous historical information. Each the explorer of the South Sea islands knows how carefully genealogy was conducted here aristocratic families - in other legends, it can reach up to 600 generations, and all of them will be described by each storyteller of any of the islands of Polynesia exactly and without a single hesitation!

The Hawaiian skyland of Kahiki and the authentic flavor of ancient Polynesia: here are amazingly clear waters of azure lagoons, slightly rippled, wild mountains, gorges and valleys. Here and there huts, and around - palm groves and breadfruit trees:

| View from Raiatea (front) of the mountains of the island of Bora Bora |

It was here that the great god Oro, revered in Polynesia, lived.

| Raiatea Island |

God Oro and a belt of red feathers

He descended to earth on a rainbow. And before settling on Raiatea, he headed to the island of Bora Bora. God settled on the top of Taimonu - "Mountain of Birds" - and began to admire the incredible, fantastic beauty of the Pacific island.

One day the god Oro saw a mortal, albeit noble, woman - Princess Vairumati. And since, according to Polynesian legends, the gods can love mortal women, Oro fell in love with her. Wairumati had the same feeling.

Then they together - a god and a mortal woman - crossed over to Raiatea, in Opoa, where Oro founded the kahuna clan of Ariohi. The first member was his wife Vairumati.

Another founder of Arioi was the god's brother Urutetefu, who is honored along with Oro himself. Oro gave him his most valuable, "sacred" gift - red feathers, a symbol of power, a sign of dignity, and later a symbol of the cult of Oro (whose statue in the sanctuary of Raiatea - Marure is decorated with a belt of red feathers).

Polynesian pilgrims who came to Raiatea to worship the statue of the great god removed some feathers from the divine belt and replaced them with others. These feathers from the sacred Gawaiki were then kept by pilgrims as the rarest relic.

Many Polynesians searched for red feathers on the most remote islands of the South Seas. One such navigator, Hiro, who was born about three hundred years after Oro crossed from Borabora to Raiatea, collected feathers of unprecedented beauty during his travels. He made a belt out of them and in front of the priests, leaders and leaders of the Arioi solemnly put it on the statue of the god.

He wanted to pay honor only to God, but the high honor was given to himself. Everyone was so amazed by the beauty of unprecedented feathers that Hiro was proclaimed the supreme leader - the king of Raiatea. Later, according to the Polynesians, the Red Belt King Hiro became a deity. But before that, he ruled Raiatea for a long time from his residence in Opoa.

| Modern residents of Raiatea dressed as Oro cultists |

War of the "red" and "white" belts

When the great king felt the breath of death, he gave the Red Belt to his firstborn, Prince Howeti. But he also had a second son, Ohatatama. The ambitious Ohatatama, who dreamed of his father's inheritance, left for Borabora, rallied the locals under his dominion, girded himself in the sanctuary with a "belt of White feathers" and declared a war to the death on his brother on Raiatea.

Borabora of the White Belt fought against Raiatea of the Red Belt for 250 years, from the end of the 14th to the beginning of the 17th century. The war between the Marorua and the Marotea, with its endless, unceasing battles, incredibly exhausted both islands, but neither famine nor terrible drought softened this enmity.

And only when the expeditionary armada of Borabora, led by Teri Marotea, the tenth descendant of the founder of the White Belt dynasty, was destroyed almost to the last man in the fields of Raiatea and the king himself died in this battle, the war ended with the defeat of Borabora.

Both islands united under the rule of the Red Belt! And the White Belt, which was once a sign of Borabor independence, was handed over to the priests as a symbol of spiritual power, not subject to the king.

Such is the fate of the White Belt. What happened to those who wore it? The implacable opponent of Raiatea, King Teri Marotea, died. And his only daughter, Te Tuani, married the son of the Raiatean king Mata.

And, as happens in sentimental films, the hands of the enemies finally joined, once again linking the two Polynesian lands of the Leeward Islands.

Raiatea is the birthplace of Ariori, the masters of Hula

On Raiatea, in Opoa, a secret society of Ariori has appeared. Ariori recognized Raiatea as their center, and the last Gawaiki of the Polynesians, their "sacred" island, began to play another important role. According to legend, the Ariori society in the "capital" of the island of Opoa was "founded" by the great god Oro.

In their boats they visited the Polynesian islands, arranging there performances telling about the life and deeds of the legendary the founder of the clan - the god Oro, and other deities, as well as famous leaders and sailors.

Scientific books refer to Ariori as a "Polynesian society wandering dance lovers.

Hawaiian shaman Serge Kahili King talks about them as one of the most respected shamanic clans, peacekeeping shamans:

In Tahiti, the shamanic clan of Ariori specialized in peacemaking.

Using singing, dancing and poetry as a means of influence, they traveled from island to island, on each of them arranging their performances.

The respect for the Ariori shamans was so great that all wars ceased while they were present.

Retelling myths and legends, they reminded the belligerents of their common roots and destiny on this earth, and sometimes obscene and irreverent jokes used by them made opponents realize the perniciousness of enmity.

However, you can read more about them here: Kahuna Ariori. shamans-peacemakers and the first masters of Hula

A short video about Raiatea as a modern resort:

/author of the article Elena Shandrikova, based on materials

of the book of the researcher M. Stingle "The Last Paradise"//

Other articles on the History of Hawaii and the Society Islands

All articles about the Hawaiian hula dance

Tamura - frwiki.

Tamure (pronounced and sometimes spelled Tamouré in French and Tamure in the form written in Tahiti) is the name of a modern variation of the Tahitian dance, known locally as Ori Tahiti.

Short story:

Shortly after World War II Pacific Battalion veteran Louis Martin enjoyed the Queen's disco, wrote a very popular song based on traditional rhythms and used the word "Tamure" as the chorus. Thus, he received the nickname "Tamur Martin" and passed on the name of the Tahitian dance, which "Popaa" would describe "Ori Tahiti".

Thus, he received the nickname "Tamur Martin" and passed on the name of the Tahitian dance, which "Popaa" would describe "Ori Tahiti".

The Tahitian dance known as "Ori Tahiti" is one of the most famous dances in French Polynesia. This is a traditional dance from Tahiti listed on the Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage in France in 2017.

Summary

- 1 Tahitian dance Ori Tahiti

- 2 History

- 3 Cultivated

- 4 Notes and references

- 5 Bibliography

- 6 See also

- 6.1 Related articles

- 6.2 External links

This is a duet in which the man hits his thighs with scissors and the woman rotates her hips. The movement of the dancer's feet is called paoti , which in Tahitian means " chisel" , and includes the connection of the heels and the bending of open and tight knees in a continuous reciprocating motion. The rotation of the dancer's hips is due to the movement of her knees, and her feet and shoulders must remain horizontal. Each movement of the arms and hands has a symbolic meaning, which is accompanied by a description of the gestures of the legend. The dancer moves relatively little, and the dancer usually moves around her partner, who is the central pivot of the dance. Dancers sometimes move sideways or up and down while crouching while keeping their hips and knees moving. Dance steps have been codified such as tue (kick) or paoti .

Each movement of the arms and hands has a symbolic meaning, which is accompanied by a description of the gestures of the legend. The dancer moves relatively little, and the dancer usually moves around her partner, who is the central pivot of the dance. Dancers sometimes move sideways or up and down while crouching while keeping their hips and knees moving. Dance steps have been codified such as tue (kick) or paoti .

Tamure dance to the accompaniment of drums, consisting of toere , hollow wooden cylinders struck with sticks, and drum pahu . The rhythm of the beats and the swaying of the dancer's hips are interconnected, with slow phases and fast acceleration replacing each other.

Tamure usually dance in plant costumes, ahu, more than often referred to as " more" , vegetable fiber skirts and crowns. Men ( tane ) are shirtless and often tattooed, while wahina wear coconut bras. Other costumes are also used, made from sacred auti leaves, pareo cloth or tapa , more commonly reserved for " aparima .

Tamure is basically a duet, when danced in a group it forms " ote'a . Other styles that share the dance movements of tamure have a special name, such as aparima. The first European navigators describe about 17 different traditional Tahitian dances. Today there are four main forms practiced: ' ote'a , ' aparima , pao'a and hivinau . The survival of Marquesas and Māori culture led to the reintegration of the Haka, exclusively men and warriors.

History

ʻUpaʻupa circa 1909, in pareo .

The old version of Ori Tahiti is the upaupa, which is now gone. "Otea" already existed, but then it was considered a male dance and was described as a dance of war.

The missionaries of the London Missionary Society viewed traditional Polynesian dances as satanic and obscene, so they were banned for a long time during the colonization, as was much of Tahitian culture. Thus King Pomare II in 1819and Queen Pomare in 1842 introduced two bans on "lustful songs, games and amusements".

Marquess Princess circa 1909, tapa costume.

These dances have been preserved in popular culture in private settings. The celebration in 1880 of the French National Day of July 14 permitted the return of traditional holidays and their content under the name Tiurai festivals.

At the beginning of XX - th centuries, they are publicly manifested mainly during the celebration of July 14 or the arrival and departure of ships. At the same time, costumes made from traditional materials using tapas are making a comeback. Between 1920 and 1930, then over in plant fibers appeared and developed rapidly.

Tamure is the name of the Tuamotu fish, the exact name of the dance being 'Ori Tahiti (Tahitian dance). Shortly after World War II, Pacific Battalion veteran Luis Martin wrote a very popular song using traditional rhythms and using the word Tāmūrē as the refrain. Thus, he received the nickname Tamura Martin and passed this name on to the dance.

Thus, he received the nickname Tamura Martin and passed this name on to the dance.

In 1956, Madeleine Moy, visiting folk dances from various French regions of mainland France, felt the need to update the traditional Tahitian dance. Therefore, when she was the principal of the school, she created the first dance group called Heiva . In the second half of the XX - th centuries, Polynesian dances evolved, looked at the "traditional" standard and organized into dance troupes. The popular practice fell in favor of dance groups and schools organized performances in the tiurai dance competition (becomes Heiva at the end of XX - th ), holidays, as well as in the tourist professional environment, which is developing due to the opening of Faa International Airport in 1961.

Since the 1980s and 1990s, there has been a resurgence in popularity of traditional dances and the number of dance schools has increased dramatically. Groups participate in international events and organize tours. The dances and costumes also develop under the influence of the competitions generated by the competitions organized for the khiva. This evolution ends up going beyond the limits imposed by "tradition", leading to the creation of groups such as Les Grands Ballets de Tahiti, who freed themselves from these restrictions to continue the search for new movements in dance, choreography, music and music, costumes. . A division between groups is then created according to these traditional criteria, leading to the exclusion of "modern" groups from competition such as the heiva.

Groups participate in international events and organize tours. The dances and costumes also develop under the influence of the competitions generated by the competitions organized for the khiva. This evolution ends up going beyond the limits imposed by "tradition", leading to the creation of groups such as Les Grands Ballets de Tahiti, who freed themselves from these restrictions to continue the search for new movements in dance, choreography, music and music, costumes. . A division between groups is then created according to these traditional criteria, leading to the exclusion of "modern" groups from competition such as the heiva.

Advertisements sometimes sell the Tahitian dream with tamure while the dance they promote is hula, a distinctly Hawaiian dance that has its own costumes, history, musical instruments, and style that emphasizes hand movement.

Cultivated

- Alessandro Alessandroni founded the eight-part choir I Cantori Moderni in 1961. It is this vocal group that we hear in the song Samoa Tamure ( Samoa Tamure ) written by Armando Trovacholi for the soundtrack of the 1963 film I Mostri directed by Dino Risi.

This Polynesian-sounding song illustrates New Year's Eve's ball scene from film 9 MÕIS Ferme , directed in 2013 by Dupontelle.

This Polynesian-sounding song illustrates New Year's Eve's ball scene from film 9 MÕIS Ferme , directed in 2013 by Dupontelle.

Notes and links

- ↑ Apple tree 2017, p. 3.

- ↑ " Patrimoine environmentalnement ", at http://www.patrimoine-environnement.fr (Retrieved July 25, 2019)

- ↑ tahitienfrance.free.fr

- ↑ Tahitian dance, " Madeleine Moua: Grande Dame de la Danse Tahitienne / Ori Tahiti ", on danse-tahitienne.com (accessed June 19, 2018) .

- ↑ Alain Ricard, Hawaii , ed. Kartala, 2003, p. 121

Bibliography

- Dance in Tahiti , Patrick O'Reilly, Nouvelles Éditions latines, Paris.

- Marion Fine, Ori tahiti: dancing in Tahiti , Papeete, Au vent des îles, , 79 p.

(ISBN 978-2-909790-11-4 and 2-909790-11-8, online presentation)

(ISBN 978-2-909790-11-4 and 2-909790-11-8, online presentation) - Tamatoa Pomare Pommier, Le 'Ori, Artistic, Social and Cultural Practice of Tahiti and Society Islands (Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage), Papeete, Ministry of Culture, , 23 pp. (read online)

- Te 'Ori Tahiti: Repertoire of Tahitian Dance Steps , Papeete, French Polynesian Conservatory of Arts, , 128 p.

See Also

Related Articles

- Paoa

- Aparima

- Otea

- Hivinau

- Hawaiian hula

- Polynesian music

External Links

- Duet of Heifara Maurien and John Outzekowski, best dance couple at Heiva 2005, video on Youtube

- Taut Paofay, male solo, Heiva and Tahiti, 1995

- Dance group Tamarii Tiipoto at Heiva 2000 in Bora Bora

- Tore & Groin Percussion Training

- Interview with Lorenzo Schmidt at RFO.

fr, available online at the Internet Archive

fr, available online at the Internet Archive - (ru) Tamure

- (c) 'upa'upa

| Indigenous cultures of Oceania | |

|---|---|

| Mythology | Aboriginal mythology · Hawaiian mythology · Mangareva Mythology (c) · Tahitian mythology · Maori mythology · Melanesian mythology (c) · Menehune · Micronesian mythology (c) · Category: Fantastic creature Oceania · Polynesian Mythology · Category: Rapa Nui mythology Rapa Nui mythology ( ru ) |

| Peoples | Aboriginal Australian Austronesian Chamorro Moriori Fiji Hawaiian Kanak Maori Marshallese Melanesian Negritos Papua Polynesian Maohi Rapa Nui Rotuma (c) Samoan (c) Tahitian Tongan Glory Torres Strait |

| Culture by geographic region | Australian Aboriginal Culture Australian Aboriginal Astronomy (in) Lapita Culture Micronesian Culture Moriori Culture Revival (in) Cook Islands Culture Easter Island Culture Fiji Lau Islands #Culture and Economy (en) ceremonies (en) Guam #Culture Hawaiian culture Lomilomi Kiribati culture Marquesas culture (en) Marshall Islands culture Stick Culture of the Federated States of Micronesia Nauru Culture of New Caledonia Culture of New Zealand Culture of Niue Norfolk Island # Culture Culture of Paluan Culture of Papua New Guinea (en) Pitcairn Islands # Culture and Religion (in) Culture of Samoa (in) Culture of the Solomon Islands Culture of Tonga (c) Torres Strait Islanders #Culture (c) Culture of Tuvalu Vanuatu Culture in Wallis and Futuna (c) Yap Islands #Culture Yap Island # Navigation Weriyeng (en) |

| Canoe | Aboriginal canoe Dugout (en) Alingano Maisu (en) Arawa Drua Dugout (boat) #Pacific Islands (en) Gawailoa (en) Hokulea Malia (canoe) (en) Maori migration Canoe in balance Pirogue Dugout · Canoe Polynesian sailing # sailing_canoes (in) · Prao · Va'a · Vaka · Wa · Waka · ( list ) · Walap |

| Dance | Aparima Cibi Farah (party) (EN) Fire resistance (EN) March fire Haka Hivinau Hula Kailao Kapa Haka Kiribati dance (en) Meke (en) Otea Pao 'a Pilou poi Dance in Rotuma (c) Culture_of_Samoa dance # (c) Category: Dance in Tahiti Tamure Tautoga Dances of Tonga (c) upa 'UPA' |

| Music | Kaneka Music from the Austral Islands (en) Aboriginal Music Austronesian_peoples # Music (en) Music from the Cook Islands (en) Music from Easter Island (en) Music from Fiji (en) Music from Guam (on) Hawaiian music Music of Kiribati (in) Lali (drum) (en) Maori music Music of Melanesia (in) Music of Micronesia (in) Music of the Federated States of Micronesia (in) Music of Nauru (in) Music of Caledonia Music Music of New Zealand (in) Music of Niue (in) Music of the Northern Mariana Islands (en) Paluane Music Music of Papua New Guinea (in) Polynesian Music Music of Samoa (en) ) Slit Drum Music of the Solomon Islands ( en) Music from Tahiti (en) Music from Tokelau (en) Music from Tonga (en) Music from Tuvalu (en) Music from Vanuatu (en) |

| Festivals | Australia Garma Traditional Culture Festival (in) Hawaii Heiva Aloha Festivals (in) Merrie Monarch Festival (in) Hula World Invitational Festival (in) List of Fiji Holidays (in) Melanesia 2000 New Zealand Festival Pacifica (in) Pacific Community Pacific Arts Festival (in) Festivals in Papua New Guinea (in) Marquesas Arts Festival Pacific International Book Fair |

| Architecture, sculpture | Kanaksky case · Tjibau cultural center · Fare · Haus tambaran · Langi · Marae · moai · Nguzu nguzu · Nakamal · Pa · Paepae · Stone latte |

| Gastronomy | Bugna Cook Islands Cuisine Hawaiian Cuisine Marshallese Cuisine New Caledonian Cuisine Paluane Cuisine Tahiti Cuisine Tuvalu Cuisine Fafaru Four Kanakas Kalua Kava Po'e Seboseb Bat Meat Kangaroo Meat |

| Research and distribution | Asian American and Pacific Islander Policy Research Consortium (en) Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (en) Kanak Language Academy Kanak Cultural Development Agency Tahiti Academy University Press of New Caledonia |

Learn more

- How to do the breakdown dance

- How to dress for a dance

- How to become a better dancer at home

- How to dance like carlton banks

- How to make lights dance with music

- How to do the car wash dance

- How to dance like a mexican

- How many dances does fortnite have

- How to clean suede dance shoes

- How to make a dancers bun

- How to do the dancing handkerchief trick