How to do the peter pan dance

Dance Academy students, grads and dads in ‘Peter Pan’

ArtsMore than 100 Vashon Dance Academy (VDA) performers fill the cast of ‘Peter Pan.’

By Elizabeth Shepherd • June 15, 2022 1:30 am

(Yui Holbrook Photo) Isa Sanson Frey will dance the role of Peter Pan for Dance! VashonThis weekend, Dance! Vashon will present “Peter Pan,” featuring Vashon Dance Academy dancers from pre-schoolers to “dance dads,” to almost-graduates and even Academy alums who will take guest-starring turns on the stage.

More than 100 Vashon Dance Academy (VDA) performers fill the cast, with seniors Lisee Crayton, Lila Perez, Isa Sanson-Frey, and Amelia Spence anchoring the show. Sanson-Frey will dance the lead roles of both Peter Pan and Tink, which she will share with Lorien Buffington and Isabella Peani. Spence will dance the lead of Hook, along with Gerritt van Roekel. Crayton will share the role of Wendy with Marina Gill, and Perez will dance Tiger Lily, along with Kate Spranger.

Other Academy dancers will fill roles as varied as baby crocodiles, young teddy bears, and a tropical forest that has come to life. Artistic Director Cheryl Krown said that this group of dancers is particularly suited to such a “giant adventure, as it covers so many styles of dance and music along the way.”

She also said that she and assistant artistic director Julie Gibson have filled the production with “sword fights, pirates, battles and near-escapes, sure to enthrall all those supportive brothers and cousins and neighbors sitting in the audience.”

As audiences have come to expect from VDA performances, a group of dancing dads is currently hard at work learning choreography that never fails to elicit big laughs, Krown said. Many more parent volunteers have contributed to the production’s set design, costumes and lighting.

The show will have its opening bow at 7:30 p.m. Friday, June 17, at Vashon High School. Additional shows take place at 1:30 p.m. and 7:30 p. m. on Saturday, June 18, and 1:30 p.m. on Sunday, June 19.

m. on Saturday, June 18, and 1:30 p.m. on Sunday, June 19.

Advance tickets are available in the Vashon Dance Academy lobby as well as at the Burton Coffee Stand. They will also be sold at the door, if available.

More Stories From This Author

Arts

Powerhouse performer brings suffragist Alice Paul to life

In the show, Dimitre shape-shifts to embody Alice Paul — one of the most influential leaders of the 20th-century women’s rights movement, who fought not only for women’s equality in the United States but also, throughout the world.

By Elizabeth Shepherd • October 20, 2022 12:46 pm

‘Bon Appétit, The Julia Child Operetta’ comes to Vashon

The one-act operetta stars Seattle actor Anne Allgood and is based on one of Julia Child’s television episodes demonstrating how to bake a chocolate cake.

By Juli Goetz Morser For Vashon Center for the Arts • October 20, 2022 1:30 am

With storytelling and music, a show dives into deep waters

Audience members have called “Nights of Grief and Mystery” a “heart-wrenching, funny, brilliant show,” and a “beautiful and unraveling intimate night.”

By Beachcomber Staff • October 20, 2022 1:58 pm

SUBSCRIBE

TODAY

LEARN MORE

‘Peter Pan,’ ‘Romeo & Juliet,’ and a Beach Boys-inspired ‘Good Vibrations’ will be making appearances this year.

Whether African, classical or hip-hop rhythms, the new dance season provides plenty of toe-tapping entertainment from world-renowned names and local stalwarts alike.

SEPTEMBER

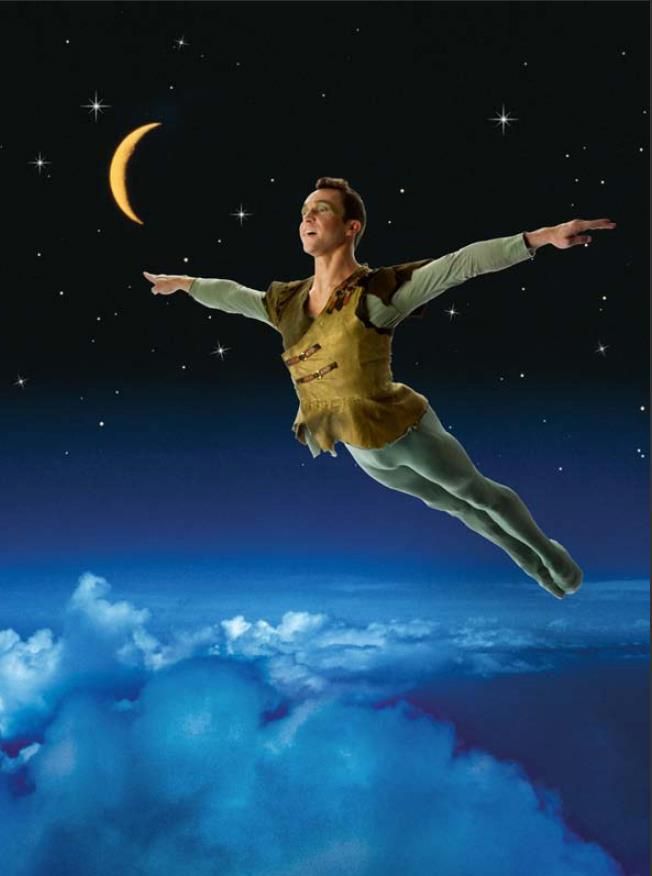

Through Sept. 18 — “Peter Pan”: Houston Ballet’s trip to Neverland, as envisioned by Sir Edward Elgar and choreographer Trey McIntyre. Wortham Theater Center

Houston Ballet presents “Peter Pan” through Sept. 18.

Houston Ballet13 — “Mind the Gap XXI”: Twenty-first local-talent showcase by nonprofit Dance Source Houston. Midtown Arts & Theater Center Houston

17-25 — “Mapping & Glaciers”: Aided by films and Samuel Lipman’s score, Karen Stokes Dance reflects on nature and human interaction. Midtown Arts & Theater Center Houston

21 — “Pan-African Passport”: From Kucheza Ngoma Dance Company and Griot Manning Mpinduzi-Mott, panoramic look at the diaspora of African dance. Miller Outdoor Theatre

Sept. 22-Oct 2 — “Good Vibrations”: Arthur Pita’s Beach Boys-inspired dance anchors Houston Ballet program. Wortham Center

Wortham Center

23-24 — “Take Off”: Uptown Dance Company opens 2022-23 season. Midtown Arts & Theater Center Houston

Sept. 30-Oct. 1 — “Movements: New & Revised”: Social Movement Contemporary Dance artistic director Elijah Alhadji Gibson’s three-part hip-hop manifesto. Midtown Arts & Theater Center Houston

OCTOBER

1-13 — “Tongues”: Cloud Gate Dance Theater of Taiwan conjures legendary ’60s storyteller. Wortham Theater Center

1 — “Salsa y Salud”: Foundation for Modern Music marks 10 years of sizzling salsa performances. Miller Outdoor Theatre

1 — “Season Kickoff Fundraiser”: Houston Contemporary Dance hosts coffer-filling gala. 1302 Houston

14 — “Diavolo”: As seen on “America’s Got Talent,” artistic director Jacques Heim’s LA-based troupe combines dance, acrobatics and gymnastics to heart-stopping effect. Jones Hall

As seen on “America’s Got Talent,” artistic director Jacques Heim’s LA-based troupe combines dance, acrobatics and gymnastics to heart-stopping effect in “Diavolo” at Jones Hall.

20-22 — “Score”: Houston’s 6 Degrees dance company marks artistic director Toni Leago Valle’s 20th year with retrospective and peek at new “Pop Demo.” Midtown Arts & Theater Center Houston

22 — “Asia to the World”: Dance of Asian America presents vibrant choreography and equally compelling costumes from across the continent. Miller Outdoor Theatre

NOVEMBER

4 — Forever Tango: How the distinctive Argentinian dance was born. Miller Outdoor Theatre

11 — “The Four Journeys”: Denver-based Cleo Robinson Dance Company dives into Mexican folklore. Miller Outdoor Theatre

Nov. 25-Dec. 24 — “The Nutcracker”: It wouldn’t be the holidays without Houston Ballet’s fanciful spin on Tchaikovsky’s mouse-king opus. Wortham Theater Center

DECEMBER

1-11 — “The Nutcracker Suite”: Uptown Dance Company’s rendition of seasonal staple. Uptown Dance Centre Outdoor Theatre

2 — “Margaret Alkek Williams Jubilee of Dance”: World premiere by emerging choreographer Silas Farley highlights Houston Ballet’s one-night repertory hodgepodge. Wortham Theater Center

Wortham Theater Center

FEBRUARY

3 — “Dance Theatre of Harlem”: Resident choreographer Robert Garland’s New York City company bridges classical and modern dance to celebrate African American culture. Jones Hall

Feb. 23-March 5 — “Romeo & Juliet”: Houston Ballet artistic director Stanton Welch’s setting of the Shakespeare/Prokofiev classic transports the audience to Renaissance-era Italy. Wortham Theater Center

24, 26 — “Spring Is in the Air”: Uptown Dance Company shakes off winter cobwebs. Uptown Dance Centre Outdoor Theatre

MARCH

9-19 — “Summer & Smoke”: Houston Ballet premieres choreographer Cathy Marston’s dance based on the Tennessee Williams play. Wortham Theater Center

10 — “Ragamala Dance Company”: Led by mother-daughter choreographers, Minneapolis-based dancers delve into Hindu lore in “Fires of Varanasi.” Wortham Theatre Center

24 — “The StepCrew”: Energetic Canadian quintet combines tap with both Irish and Ottawa Valley stepdancing. The Grand 1894 Opera House

The Grand 1894 Opera House

APRIL

22 — “Rockin’ in the Park”: Uptown Dance Company frolics in the great outdoors. Spring Valley Village City Park

28-29 — “Academy Spring Showcase”: Houston Ballet’s stars of tomorrow take center stage. Wortham Theater Center

29 — “Wine & Dance”: Uptown Dance Company ends the season with a toast. Uptown Dance Centre Outdoor Theatre

MAY

May 25-June 3 — “Divergence”: In its first performance in a decade, Welch’s titular ballet shares the stage with Aszure Barton’s Houston-inspired “Angular Momentum” and a world premiere by Oscar-nominated choreographer Justin Peck. Wortham Theater Center

JUNE

8-18 — “Swan Lake”: Welch’s staging of Tchaikovsky’s other iconic ballet draws inspiration from pre-Raphaelite painting “The Lady of Shalott.” Wortham Theater Center

The story of "Peter Pan" • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

Please change your browser settings.

- History

- Art

- Literature

- Anthropology

I'm lucky!

Literature

Every famous fairy tale has its own myth. Carroll's boat trip with the Liddell sisters; a map of an imaginary island drawn by Stevenson's stepson, and so on. This myth certainly refers to the child, the first addressee of the tale. We tell you what is behind the texts about Peter Pan and to whom they were addressed

Author Alexandra Borisenko

Author

James Matthew Barry. Photograph by Herbert Rose Barro. 1892 National Portrait Gallery James Matthew Barry (1860–1937) was not a children's writer. His plays and novels written for adults were admired by Thomas Hardy, John Galsworthy John Galsworthy (1867-1933) - English playwright and prose writer, author of the famous Forsyte Saga cycle, Henry James, Mark Twain, Arthur Conan Doyle and other contemporaries. Barry is a controversial figure: melancholy and silent (sometimes to the point of obscenity), he had many friends and easily found a common language with children.

Barry is a controversial figure: melancholy and silent (sometimes to the point of obscenity), he had many friends and easily found a common language with children.

Barry was born into a simple family - his father was a weaver - in the small Scottish town of Kirrimure and achieved everything that his parents could only dream of. Thanks to the help of his older brother, James graduated from the University of Edinburgh. His writing career was extraordinarily successful, he received the title of baronet Baronet - a title of nobility in England, which constitutes a transitional step between the lower and higher nobility. He was elected rector of the University of St. Andrews and received many other honors. However, he experienced many losses and tragedies, and this fracture permeates almost all of Barry's texts, including the fairy tale about Peter Pan.

Chronology

The Russian reader knows "Peter Pan" first of all from the story "Peter Pan and Wendy". But in fact, this is a cycle of texts in various genres, written from 1901 to 1928.

1901 photo album with captions The Boy Castaways of Black Lake Island

1902 novel The Little White Bird didn't want to grow up" (The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up)

1906 - short story "Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens"

1911 - story "Peter Pan and Wendy" (Peter Pan and Wendy) and was not used in the film adaptation.

1925 - story "Jas Hook at Eton" (Jas Hook at Eton) In 1927, Barry read this text at Eton.

1926 essay "The Blot on Peter Pan"

1928 published text of The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up

Fairy tale recipients

Arthur Llewelyn Davis with his sons. 1905 Arthur Llewelyn Davis holds Nicholas in his arms, Jack, Michael, Peter and George stand in front.Wikimedia Commons / jmbarrie.co.uk

“…I created Peter by rubbing the five of you together like savages rub wands to strike a spark. He is the spark ignited by you,” Barry wrote in Dedication to the play. These five are the Llewelyn Davis brothers: George, Jack, Peter, Michael and Nicholas. All the adventures of Peter Pan are dedicated to them - and for the most part they were their own adventures. Barry considered the Davis brothers to be his co-authors and gave the name of one of them to the main character. Peter Davis suffered all his life from being considered "that very Peter Pan", and called the fairy tale "this terrible masterpiece".

All the adventures of Peter Pan are dedicated to them - and for the most part they were their own adventures. Barry considered the Davis brothers to be his co-authors and gave the name of one of them to the main character. Peter Davis suffered all his life from being considered "that very Peter Pan", and called the fairy tale "this terrible masterpiece".

In 1897, Barry was thirty-seven years old: he was already a famous writer, his plays were staged on both sides of the Atlantic. After moving from Edinburgh to London, he easily entered the metropolitan literary circle, bought a house in South Kensington and a summer cottage in Surrey, married the beautiful actress Mary Ansell and adopted a St. Bernard.

George, Jack and Peter Llewelyn Davies. Photograph by James Barry. 1901 Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University Walking his dog in Kensington Gardens, he met the Davis brothers. There were three of them then: five-year-old George, three-year-old Jack and baby Peter. Soon the writer met with their parents - lawyer Arthur Llewelyn Davies and his wife Sylvia, née du Maurier. The famous writer Daphne Du Maurier was Sylvia's niece, the daughter of her brother Gerald. to theaters and dinner parties, took him on trips and invited him to Surrey, taking an active part in the fate of the boys. They called him "Uncle Jim". This caused a lot of gossip, but Barry did not attach any importance to them. At 1900 and 1903 Michael and Nicholas were born.

Soon the writer met with their parents - lawyer Arthur Llewelyn Davies and his wife Sylvia, née du Maurier. The famous writer Daphne Du Maurier was Sylvia's niece, the daughter of her brother Gerald. to theaters and dinner parties, took him on trips and invited him to Surrey, taking an active part in the fate of the boys. They called him "Uncle Jim". This caused a lot of gossip, but Barry did not attach any importance to them. At 1900 and 1903 Michael and Nicholas were born.

The White Bird novel

Arthur Rackham's illustration for James Barrie's Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. London, 1906 Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge Peter Pan first appears in the insert chapters of the grown-up and not-too-jolly novel The White Bird, which Barry published in 1902 with a dedication to "Arthur and Sylvia and their boys - mine boys!" The plot revolves around a lonely bachelor who tries to "appropriate" a boy named David, making him his child. He takes care of the young family, trying to keep his participation secret, but he fails: David's mother guesses everything.

He takes care of the young family, trying to keep his participation secret, but he fails: David's mother guesses everything.

The novel also contains a few inserted chapters about Peter Pan, the baby who flew from the nursery to Kensington Gardens. Barry told the boys about his adventures, Davis, and it was these stories that became the basis of the texts about Peter. Even at the beginning of their acquaintance, Barry assured George that his brother Peter still knew how to fly, because his mother did not weigh him at birth, and George tried for a long time and unsuccessfully to track down the baby at the time of night flights. On another occasion, George asked what the letters WSM and PP stood for on the white stones in Kensington Gardens. The stones served as the boundary of the church parishes of Westminster St. Mary's and Parish of Paddington, but Barry came up with the idea that these were the graves of children - Walter Stephen Matthews (Walter Stephen Matthews) and Phoebe Phelps (Phoebe Phelps). The story of the hero of The White Bird about Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens ends like this: “But how strange it is for parents who hastened to the Gardens to open the gates to find their lost children to find cute little gravestones instead. I really hope Peter isn't in too much of a hurry with his spatula. It's all rather sad.” Translated by Alexandra Borisenko. This episode flashed in the second edition of the Russian translation by A. Slobozhan (first edition - 1986, the second - 1991) and disappeared in subsequent editions. In the translations of G. Grineva (2001) and I. Tokmakova (2006), it is completely absent.

Mary's and Parish of Paddington, but Barry came up with the idea that these were the graves of children - Walter Stephen Matthews (Walter Stephen Matthews) and Phoebe Phelps (Phoebe Phelps). The story of the hero of The White Bird about Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens ends like this: “But how strange it is for parents who hastened to the Gardens to open the gates to find their lost children to find cute little gravestones instead. I really hope Peter isn't in too much of a hurry with his spatula. It's all rather sad.” Translated by Alexandra Borisenko. This episode flashed in the second edition of the Russian translation by A. Slobozhan (first edition - 1986, the second - 1991) and disappeared in subsequent editions. In the translations of G. Grineva (2001) and I. Tokmakova (2006), it is completely absent.

In 1906, insert chapters from The White Bird were issued as a separate edition with illustrations by the then-famous artist Arthur Rackham. These illustrations have become classics: for all their fabulousness, they accurately reproduce the topography and views of Kensington Gardens (there is even a map in the book). Rackham here follows Barry, who created a kind of guidebook that mythologises the paths, ponds and trees of his beloved park and turns them into attractions. However, Kensington Gardens is forever associated with Peter Pan not only for this reason. On the night of April 30 to May 1, 1912 years later, a statue of Peter Pan with fairies, hares and squirrels by the sculptor Sir George Frampton suddenly appeared on the shore of the lake. An ad in The Times explained that it was a gift to children from James Barry. And although he installed the sculpture without permission and without any permission, it still stands there. Barry had his own key to one of the gates of Kensington Gardens - he received it as a reward for his book..

These illustrations have become classics: for all their fabulousness, they accurately reproduce the topography and views of Kensington Gardens (there is even a map in the book). Rackham here follows Barry, who created a kind of guidebook that mythologises the paths, ponds and trees of his beloved park and turns them into attractions. However, Kensington Gardens is forever associated with Peter Pan not only for this reason. On the night of April 30 to May 1, 1912 years later, a statue of Peter Pan with fairies, hares and squirrels by the sculptor Sir George Frampton suddenly appeared on the shore of the lake. An ad in The Times explained that it was a gift to children from James Barry. And although he installed the sculpture without permission and without any permission, it still stands there. Barry had his own key to one of the gates of Kensington Gardens - he received it as a reward for his book..

The play

Academy after the show. Dumfries, early 20th century Peter Pan Moat Brae Trust Two years after the publication of the novel, in 1904, Barry decided to bring Peter Pan to the stage with a play full of wonder and adventure. It soon became clear that such a production would require huge investments. Barry's friend, American Charles Froman, became the producer: he fell in love with the text so much that he agreed to the most incredible and expensive ideas. Barry wanted the characters to fly, and John Kirby, an expert on creating the illusion of flight on stage, was brought in to implement this idea. But his equipment seemed to Barry too primitive, too conspicuous. He asked Kirby to build a new apparatus that would actually give the impression of flying, and he agreed. The actors needed serious training - it was especially difficult to take off and land. At first, everyone was delighted with notes like “Rehearsal at 12.30. Flight", but when the artists were asked to insure their lives, the excitement subsided noticeably. However, not all of Barry's ideas were implemented. For example, he wanted the audience to see the Tinker Bell fairy through a reducing lens, but this turned out to be technically impossible, and then it was decided that a light would represent the fairy on the stage, and the audience would hear her voice.

It soon became clear that such a production would require huge investments. Barry's friend, American Charles Froman, became the producer: he fell in love with the text so much that he agreed to the most incredible and expensive ideas. Barry wanted the characters to fly, and John Kirby, an expert on creating the illusion of flight on stage, was brought in to implement this idea. But his equipment seemed to Barry too primitive, too conspicuous. He asked Kirby to build a new apparatus that would actually give the impression of flying, and he agreed. The actors needed serious training - it was especially difficult to take off and land. At first, everyone was delighted with notes like “Rehearsal at 12.30. Flight", but when the artists were asked to insure their lives, the excitement subsided noticeably. However, not all of Barry's ideas were implemented. For example, he wanted the audience to see the Tinker Bell fairy through a reducing lens, but this turned out to be technically impossible, and then it was decided that a light would represent the fairy on the stage, and the audience would hear her voice.

According to the author's intention, Peter Pan was to be played by a boy, but Froman hoped that the famous actress Maud Adams would play this role in America, and persuaded Barry that Peter Pan would also be played on the English stage Pan should be played by a woman Actress Nina Busikolt.. Since then, it has become a tradition. According to another tradition, Captain Hook and Mr. Darling are played by the same actor. In the first production, it was Gerald du Maurier, Sylvia's brother, who made the stilted villain Hook one of the most complex characters, both terrifying and pathetic.

1 / 2

Maud Adams as Peter Pan. 1905 Museum of the City of New York

2 / 2

Nina Busicoult as Peter Pan. 1900s The Peter Pan Chronicles

Premiered at the Duke of York's Theater in London on 27 December 1904. There were much more adults in the hall than children, but from the first minute it became clear that everything was a success. In a telegram to Froman, who was in America at that moment, the English manager wrote: “Peter Pan, ok. Seems like a big success."

There were much more adults in the hall than children, but from the first minute it became clear that everything was a success. In a telegram to Froman, who was in America at that moment, the English manager wrote: “Peter Pan, ok. Seems like a big success."

During rehearsals, Barry constantly made changes, something changed as a result of improvisation. Several endings have survived. In one of them, Wendy agreed to stay with Peter in Kensington Gardens, they found a forgotten baby there, and Wendy was glad that he would take care of Peter when she grew up. In another, a dozen mothers took to the stage to adopt lost boys. But the well-known ending with an adult Wendy and her little daughter, to whom Peter Pan flies, was written separately, rehearsed in secret from the director and completely unexpectedly performed at 1908 at the last performance of the fourth season - and Barry even appeared on stage - Barry did the same with his other plays. For example, during the performance of the play “Darling Brutus” in 1919, the “Author’s Letter” was suddenly read from the stage. This was the only time such an ending was performed during the author’s lifetime, and it was she who subsequently became canonical.

This was the only time such an ending was performed during the author’s lifetime, and it was she who subsequently became canonical.

Where did it come from

Peter Pan

Illustration by Francis Donkin Bedford for James Barrie's Peter Pan and Wendy. New York 1911 Harold B. Lee Library / Brigham Young UniversityBarry has thought about childhood all his life and constantly returned to this theme in his work: the eternal childhood of those who died before they had time to grow up; the eternal childhood of those who cannot grow up; eternal childhood as a refuge and as a trap.

When James was six years old, his brother David died: while skating, he fell and hit his head. To console his mother, James began to wear his brother's clothes, imitate his whistle and habits. Later, in Margaret Ogilvy, a novel about his mother, he described a heartbreaking scene: he enters the room, and his mother asks hopefully: "Is that you?", and he answers: "No, mother, it's me. " Some researchers believe that David was bred in the image of Peter Pan, who never grew up because he died. However, to a greater extent, it is Barry himself. He did not grow up in the literal, physical sense - his height was 161 centimeters - and always recalled his childhood with extraordinary nostalgia. He was constantly fascinated by the game: he arranged performances with his brothers and sisters, studied in the school theater, played novels about travel and adventures with friends. “When I was a boy, I knew with horror that the day would come when I would have to leave games, and I didn’t know how to do it,” he wrote in Margaret Ogilvy. “I felt that I would continue to play, but in secret.”

" Some researchers believe that David was bred in the image of Peter Pan, who never grew up because he died. However, to a greater extent, it is Barry himself. He did not grow up in the literal, physical sense - his height was 161 centimeters - and always recalled his childhood with extraordinary nostalgia. He was constantly fascinated by the game: he arranged performances with his brothers and sisters, studied in the school theater, played novels about travel and adventures with friends. “When I was a boy, I knew with horror that the day would come when I would have to leave games, and I didn’t know how to do it,” he wrote in Margaret Ogilvy. “I felt that I would continue to play, but in secret.”

The Island

Page of James Barry's album with photographs of the Llewelyn Davies family © Sotheby's The Llewelyn Davis family spent the summer of 1901 at Barrie's in Surrey. Barry played Indians and pirates with the boys on an island in the middle of the Black Lake, near which his cottage stood. He also used this island for games with his adult friends: the cricket team he created, which included Arthur Conan Doyle, H. G. Wells, Jerome K. Jerome, Rudyard Kipling, Allan Milne, G. K. Chesterton and many others, gathered here. Allahakbarries ("Allahakbarriz") - someone told Barry that "Allah Akbar" means "God help us."

He also used this island for games with his adult friends: the cricket team he created, which included Arthur Conan Doyle, H. G. Wells, Jerome K. Jerome, Rudyard Kipling, Allan Milne, G. K. Chesterton and many others, gathered here. Allahakbarries ("Allahakbarriz") - someone told Barry that "Allah Akbar" means "God help us."

That summer, Barry took a lot of photographs and then printed a kind of photo book about the adventures of the boys on the island. This album existed in two copies. The first Arthur Llewelyn Davis forgot on the train (his son Niko thought it was no coincidence), the second is kept in the Yale University Library. there, No-and-won't-be.

Captain Hook

Michael dressed as Peter Pan with James Barry as Captain Hook. August 1906 JMBarrie.co.uk The theme of Captain Hook's relationship with education appears already in the first Peter Pan texts. In the play, Hook dies with the words: "Floreat Etona" (translated from Latin as "Long live Eton!"), And in one of the options, he pursues Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, pretending to be a school teacher. In the story, Hook's obsession with his high school past reaches epic proportions. The fact is that four of the five Davis brothers studied at Eton, and Barry delved into the boys' school life with great enthusiasm. He was fascinated by the world of the old famous school, he went to all sports games, asked about the rules and traditions, memorized the jargon. This language also penetrated the text of the story: Hook mentions the “wall game” (“playing the wall”), which is played only at Eton, the elite club Pops and typical Eton phraseological units like “send up for good” - for special achievements, students were called to director for praise.

In the play, Hook dies with the words: "Floreat Etona" (translated from Latin as "Long live Eton!"), And in one of the options, he pursues Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, pretending to be a school teacher. In the story, Hook's obsession with his high school past reaches epic proportions. The fact is that four of the five Davis brothers studied at Eton, and Barry delved into the boys' school life with great enthusiasm. He was fascinated by the world of the old famous school, he went to all sports games, asked about the rules and traditions, memorized the jargon. This language also penetrated the text of the story: Hook mentions the “wall game” (“playing the wall”), which is played only at Eton, the elite club Pops and typical Eton phraseological units like “send up for good” - for special achievements, students were called to director for praise.

In addition, Barry drew on a literary tradition begun in 1857 by Thomas Hughes' Tom Browne's Schooldays. In the middle of the 19th century, public schools were reformed in England, and numerous magazines for boys began to publish stories about school life, in which the characters learn not only Latin and mathematics, but also master the "gentleman's moral code" - the same "good form", about which Captain Hook is so worried. Talbot Reed's stories about St. Dominic's were especially popular. Later, friends Barry Wodehouse and Kipling paid tribute to this genre, for example: Rudyard Kipling. Stalky & Co, 1899; P. G. Wodehouse. Tales of St. Austin's, 1903.

In the middle of the 19th century, public schools were reformed in England, and numerous magazines for boys began to publish stories about school life, in which the characters learn not only Latin and mathematics, but also master the "gentleman's moral code" - the same "good form", about which Captain Hook is so worried. Talbot Reed's stories about St. Dominic's were especially popular. Later, friends Barry Wodehouse and Kipling paid tribute to this genre, for example: Rudyard Kipling. Stalky & Co, 1899; P. G. Wodehouse. Tales of St. Austin's, 1903.

In 1927 at Eton, Barry gave a speech that was entirely dedicated to Captain Hook. The headmaster gave him the topic: "Captain Hook was a great Etonian, but he was not a good Etonian." Barry altered it somewhat - in his version, Hook was not a great Etonian, but he was a good Etonian. The plot is as follows: Hook sneaks into Eton under cover of night to destroy all traces of his stay there - all the most precious memories of his life - so as not to compromise his beloved school.

Wendy, Pirates and Indians

Wendy's prototype is Margaret Henley. Circa 1893 Wikimedia CommonsAnother genre popular in 19th century English literature was adventure literature. As a child, Barry read Robert Ballantine's Coral Island (1857), Fenimore Cooper and Walter Scott - in episodes about Indians and pirates there are clearly parodic fragments. Direct references in Peter Pan can be found to Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island (1883): Captain Hook claims that the Ship's Chef himself was afraid of him, "and even Flint was afraid of the Ship's Chef."

1 / 2

Illustration by Francis Donkin Bedford for James Barry's Peter Pan and Wendy. New York, 1912 Harold B. Lee Library / Brigham Young University

2 / 2

Francis Donkin Bedford illustration for James Barry's Peter Pan and Wendy. New York, 1912 Harold B. Lee Library / Brigham Young University

Barry knew Ballantyne, but they never met Stevenson, although they corresponded and admired each other. Stevenson wrote to Barry: “I am proud that you are also a Scot”, and in a letter to Henry James called him a genius “I am a capable writer, and he is a genius.” Stevenson spent his last years on the island of Upolu Upolu is an island in the South Pacific Ocean, part of Samoa. and invited Barry there: "You take the ship to San Francisco, my house will be second from the left." When Wendy asks Peter where he lives, he replies, "Second turn right, then straight on until morning." And even the name Wendy is indirectly connected with Treasure Island. So called Barry Margaret Henley - the daughter of one-legged poet, critic and publisher William Henley, a friend of Stevenson, who became the prototype of John Silver. Instead of the word "friendy", "friend", she pronounced "fwendy-wendy". Margaret died at the age of five, in 1894 years old, and Barry named Wendy in memory of her.

Stevenson wrote to Barry: “I am proud that you are also a Scot”, and in a letter to Henry James called him a genius “I am a capable writer, and he is a genius.” Stevenson spent his last years on the island of Upolu Upolu is an island in the South Pacific Ocean, part of Samoa. and invited Barry there: "You take the ship to San Francisco, my house will be second from the left." When Wendy asks Peter where he lives, he replies, "Second turn right, then straight on until morning." And even the name Wendy is indirectly connected with Treasure Island. So called Barry Margaret Henley - the daughter of one-legged poet, critic and publisher William Henley, a friend of Stevenson, who became the prototype of John Silver. Instead of the word "friendy", "friend", she pronounced "fwendy-wendy". Margaret died at the age of five, in 1894 years old, and Barry named Wendy in memory of her.

Dead children and living fairies

Arthur Rackham's illustration for James Barrie's Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. London, 1906 Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge

London, 1906 Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge Although technically all of the Peter Pan stories were created in the 20th century, Barry himself and his work belong to the Victorian era. His attitude towards children and childhood is also typically Victorian. Following the romantics, the Victorians believed that childhood is not only a time of innocence, but also a time when a person is especially close to nature and "other worlds". Themes such as the death of children were familiar and commonplace for the then literature and life. Barry himself was one of ten children: before the birth of James, two of his sisters died (the death of his brother was not the first loss of parents).

1 / 2

Illustration by William Heath Robertson for Charles Kingsley's novel Water Children. Boston, 1915 New York Public Library

2 / 2

Arthur Rackham's illustration for James Barrie's Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. London, 1906 Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge

London, 1906 Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge

In the middle of the 19th century, the genre that today is called "fantasy" emerges. Almost simultaneously, several writers create magical worlds, thanks to which Barry's Nowhere Island, and later Narnia and Middle-earth, appeared. Barry's obvious literary predecessor is Charles Kingsley with his famous novel Water Babies, 1863. In this tale, the chimney sweep Tom drowns and finds himself in an underwater kingdom where fairies and tragically dead children live. Another writer to whom Barry owes a lot is George MacDonald. We will also meet a dying child being carried away by the North Wind At the Back of the North Wind, 1871., and a flying baby The Light Princess, 1864., and, of course, fairies. Another lover of fairies was Lewis Carroll, whose tales of Alice forever changed children's literature. Undoubtedly, and he significantly influenced Barry, Carroll was a close friend of George du Maurier, Sylvia's father, and photographed her when she was little. The last play Carroll saw in his life was Barry's The Little Minister. November 20, 189For 7 years he wrote in his diary: "I would like to watch this play again and again." Photograph by James Barry. Late 19th - early 20th century Sotheby's

The last play Carroll saw in his life was Barry's The Little Minister. November 20, 189For 7 years he wrote in his diary: "I would like to watch this play again and again." Photograph by James Barry. Late 19th - early 20th century Sotheby's

Many people close to Barry died tragically, which led some of the writer's biographers to talk about the so-called Barry curse. His sister's fiancé fell off the horse that Barry gave him and fell to his death. In 1912, Barry helped finance the expedition of polar explorer Captain Scott, during which Scott himself died. One of the seven farewell letters written by Captain Scott, freezing in a tent, was addressed to BarryIn 15, producer Charles Froman died on the Lusitania liner, and, according to survivors, refusing a seat in the boat, he quoted Peter Pan's phrase that death is the greatest adventure.

But the fate of the Llewellyn Davis family was especially unfortunate. In 1907 Arthur died of sarcoma, in 1910 Sylvia died of cancer. Barry became the boys' guardian and paid for their education. He survived some of them: in 1915, George died in the war, in 1921, Barry's favorite Michael drowned in Oxford. Peter Davis committed suicide 23 years after Barry's own death.

Barry became the boys' guardian and paid for their education. He survived some of them: in 1915, George died in the war, in 1921, Barry's favorite Michael drowned in Oxford. Peter Davis committed suicide 23 years after Barry's own death.

Translations of Peter Pan

Cover of James Barry's novel "Peter Pan and Wendy" translated by Nina Demurova. Moscow, 1968 © Detskaya Literature Publishing HousePeter Pan came to Soviet children's literature relatively late, in the late 1960s. There was a translation of "Peter Pan and Wendy" made in 1918 by L. Bubnova, but he reprinted: for quite a long time the fairy tale in the Soviet Union remained under suspicion - it was believed that unbridled fantasies were harmful to children.

Peter Pan was discovered to the Soviet reader almost simultaneously (and independently) by two of the best translators of English children's classics, Boris Zakhoder and Nina Demurova. Boris Zakhoder translated the play - at first several Youth Theaters staged his translation, then, in 1971, he came out as a book.

As always, Zakhoder translated quite freely, with great passion and sensitivity to the text Zakhoder translated the play - lighter, more dynamic and cheerful - and in his translation it is devoid of the tragic and sinister notes that Barry has .. In the preface he explains the freedom of handling the text in the interests of the addressee-child: “The translator tried to be as close to the original as possible, more precisely: to be as faithful to it as possible. And where he allowed himself small "liberties", these were liberties caused by the desire to be faithful to the author and be understandable to today's - young! - to the viewer "It is interesting that, despite the general tendency towards simplification, he did not miss the last exclamation of Hook, although he replaced it with another, better known and understandable Latin phrase - Hook dies with the words "Gaudeamus igitur", thereby making it clear to the reader that Hook received a university education..

The first translation of Peter Pan and Wendy had to lie on the table for ten years. Nina Demurova saw the English "Peter Pan" in the early sixties in India, where she worked as a translator. She liked Mabel Lucy Atwell's illustrations, bought the book and sat down to translate it. This was her first translation experience, and naively she sent it to the Detgiz publishing house. Of course, to no avail. But ten years later, when Demurova became a famous translator thanks to the translation of Alice, she received a call and was offered to publish Peter.

Nina Demurova saw the English "Peter Pan" in the early sixties in India, where she worked as a translator. She liked Mabel Lucy Atwell's illustrations, bought the book and sat down to translate it. This was her first translation experience, and naively she sent it to the Detgiz publishing house. Of course, to no avail. But ten years later, when Demurova became a famous translator thanks to the translation of Alice, she received a call and was offered to publish Peter.

Detgiz was about to seriously censor the text. Actually, this was to be expected: it is difficult to imagine a work that is more distant from the Soviet concept of childhood (joyful, cheerful, creative and devoid of "tearful sentimentality").

Children's literature was censored no less than adult literature, and for the most part the rules of the game were known to everyone in advance. The translator himself removed and smoothed out in advance what they would probably “not let through” For example, Demurova immediately removed the phrase that the boys want to remain loyal subjects of the king .. But there were also surprises: for example, Detgiz demanded to completely remove the maid Lisa from the story , which is only ten years old, because the goodies, to which the editors ranked the Darlings, should not exploit child labor. Demurova joined the fight and even turned to Korney Chukovsky.

The translator himself removed and smoothed out in advance what they would probably “not let through” For example, Demurova immediately removed the phrase that the boys want to remain loyal subjects of the king .. But there were also surprises: for example, Detgiz demanded to completely remove the maid Lisa from the story , which is only ten years old, because the goodies, to which the editors ranked the Darlings, should not exploit child labor. Demurova joined the fight and even turned to Korney Chukovsky.

Detgiz made concessions, and in 1968 the story "Peter Pan and Wendy" was published in Nina Demurova's translation. But in 1981, the same publishing house released a new translation by Irina Tokmakova: it does not mention the age of the ill-fated Lisa, there are no scenes of "excessive cruelty", everything too sad (like mentions of death), too incomprehensible (all the torments of Captain Hook and all his school background), too adult (a kiss on the corner of Mrs. Darling's mouth is replaced by a smile, the spouses do not discuss whether to leave them a child), the ambiguity of the characters is smoothed out.

Darling's mouth is replaced by a smile, the spouses do not discuss whether to leave them a child), the ambiguity of the characters is smoothed out.

It can be said that the Russian-speaking reader has some understanding of Victorian children's literature thanks to Nina Demurova, who completely ignored the adaptation strategies common to Soviet practice and left the English literature of the 19th and early 20th centuries with all its inherent complexity, sadness, sentimentality and eccentricity.

Sources

- Barry JM Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. / per. A. Slobozhan.

Tales of English writers. L., 1986.

- Barry J.M. Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. / per. G. Grineva.

Kaliningrad, 2001.

- Barry J. M. Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Didn't Want to Grow Up / transl. B. Zakhoder.

M., 1971.

- Barry J. M. Peter Pan and Wendy / trans. N. Demurova.

M., 1968.

- Barry J.M. Peter Pan / trans. I. Tokmakova.

M., 1981.

- Barrie J. M. Peter Pan [English edition].

Moscow, 1986.

- Barrie J. M. Peter Pan and Other Plays.

Oxford, New York, 1995.

- Barrie J. M. Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Peter and Wendy.

UK, 2008.

- Barrie J. M., Tatar M. The Annotated Peter Pan.

N.Y., London, 2011.

- Birkin A. J. M. Barrie and the Lost Boys: The Real Story Behind Peter Pan.

2003.

- Carpenter H. Secret Gardens: A Study of the Golden Age of Children's Literature.

US, 1985.

- Demourova N. Peter Pan in Russia.

Bouth C., Demourova N. In the Neverland: Two Flights over the Territory. 1995.

- Green R. L. Tellers of Tales.

London, 1965.

- Barrie website: jmbarrie.co.uk

Tags

What Read

Children

England

Microstroughs

Daily short materials that we produced for the past three years

Borrowing the day

Voice of the day

The only record of the voice of Freud

9000 9000Archive

History, Literature, Anthropology

11 words to help understand the culture of Ancient Greece

Getera, acme, idiot, proxenia and other important concepts

"Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens". R. Ilyin, I am Pulinovich.

Yekaterinburg Youth Theater.

Director - Roman Feodori, set design and costumes - Daniil Akhmedov, choreographer - Tatyana Baganova.

Beloved quit. Seduced and abandoned. When the participants of the performance came out to bow and they carried flowers, everything inside fell: “How ?!” And she left the hall already with a feeling of a deceived fool - if you are left in love, you are always a fool, even if you are a doctor of science.

A scene from a performance.

Photo — Tatyana Shabunina.

A performance by Roman Feodori makes you fall in love with yourself from the first picture, from the first play of light (light designer Taras Mikhalevsky), sounds (composer Evgenia Teryokhina), breathtaking movements in which people, birds, fairies, trees, grasses, waves exist here In the lake. Kensington Garden - yes, there is a place for the well-known magician of stage images, stage designer Daniil Akhmedov to roam. But he also walks around the garden hand in hand with Tatyana Baganova, who endowed all the creatures inhabiting it with fantastic plasticity. Here, young slender women in elegant light dresses and high hairstyles of the beginning of the last century (the beautiful dancers of the Provincial Dances Anastasia Enyutina, Daria Komlyakova, Anastasia Milanich, Lyubov Savchuk, Alexandra Stolyarova) appear from somewhere in the tall grass, their smooth and at the same time brittle movements immediately fascinate with some strange "new" beauty. They write letters of request for future children, who wants a boy with great talent, who wants a girl who will marry a prince ... Then these letters turn into paper boats that float through the air to marvelous songs (poems by Daria Veryasova), gradually turning into white birds.

They write letters of request for future children, who wants a boy with great talent, who wants a girl who will marry a prince ... Then these letters turn into paper boats that float through the air to marvelous songs (poems by Daria Veryasova), gradually turning into white birds.

A scene from a play.

Photo — Tatyana Shabunina.

Children, as is known from the fairy tale of James Barry, were all birds before birth, and Peter Pan, who appeared in his cozy bright cradle by a large open window, also with angel wings behind his back. Or he just thinks so... A big, disheveled, white baby doll in the hands of four actors breaks into life with furious energy, runs, flies, plays, rages, not forgetting to kiss his mother at the same time. But when his mother (Olga Medvedeva) leaves for a minute, as she herself warns him, he flies out the window. And here the first interesting topic arises: he flies to the island of birds only because he remembers that he believes that he is sure that he has wings! To believe means to fly, you fly because you believe. In a word, when he finds out that he, like anyone who is born, in fact no longer has wings and he cannot return to his mother from the island, the doll-boy turns into a young man, who also immediately appears in some incredible plasticity of existence. (Bravo to the artist of the Youth Theater Sergey Molochkov).

In a word, when he finds out that he, like anyone who is born, in fact no longer has wings and he cannot return to his mother from the island, the doll-boy turns into a young man, who also immediately appears in some incredible plasticity of existence. (Bravo to the artist of the Youth Theater Sergey Molochkov).

A scene from a play.

Photo — Tatyana Shabunina.

Almost immediately, another wonderful theme emerges. The old raven Solomon, a large black puppet on a bare branched tree (their outlines against a gray background, with gloomy clouds of the sky - one of the aesthetic masterpieces of the play), will tell our hero that he is no longer a bird. But, since now he is doomed to live on the island of birds, then not a person. That he is "middle and half", a stranger everywhere. (We note apropos that the word, an infrequent guest in the play, also exists in a special register. Often it is not spoken by the characters themselves, but by someone from the quartet - Daria Bolshakova, Elena Strazhnikova, Danila Kondratenko, Sergei Timorin: the actors are sitting with microphones in the auditorium in front of the stage itself, and a special chilly, detached aesthetics of sound is born. )

)

But the motives of both the flight of faith, and loneliness, and talent, which in fact saves from both unbelief and loneliness, which could powerfully sound in the performance, turn out to be muffled, suppressed, buried in visual bewitching beauty. Here you are admiring the dances, but no - not even dances, some bizarre forms of communication that exist on the island between birds with heads and bodies dressed in strict suits, men (the dancers of the "Provincial Dances" - Kirill Zaitsev, Anton Lavrov, Vladislav Miroshnichenko, Anton Shmakov) and female birds. Or the incredibly textured waves of the lake that Peter swims across in a bird's nest, made of... smoke! What can we say about the fairies, about the unthinkable, sprawling and chic queen (Maria Vikulina) in Kensington Gardens, where even the image of a balloon saleswoman soaring high in the air (a flying dress shimmering with wondrous colors waving in the wind) makes it impossible to perceive anything but.

A scene from a play.