How to do a pirouette in dance

How to do a Pirouette - Ultimate Guide

Home / Dancers' Blog

Previous / Next

How to do a pirouette perfectly is the question on every dancer’s lips at least once in their dancing journey. We all know the pirouette. That dance move that everybody knows, and everybody tries to do once you say you’re a ballet dancer. Some try and succeed. Others try and don’t quite grasp how to pirouette properly. But, it’s no surprise, pirouettes are kind of a big thing – they take skill, technique, precision. Today, we’re going to share with you how to do a pirouette step by step. Move by move. It’s going to be a ride of twists and turns, figuratively and literally, so hold on whilst we share with you the tips and trick to perfect the pirouette.

I dare you to try to attend an audition and not have to do a pirouette. You’ll stand on the stage and if you’ve not perfected your good turning technique, it’s more or less over. You stand and look around and see everybody else with these gliding turns, double pirouette even triple pirouette and if you’ve not yet perfected your pirouette turns – it can feel hopeless.

The ballet pirouette is notoriously a difficult ballet step. In order to successfully complete a pirouette, you must make a full 360 degree turn around yourself, sounds easy? Now, you’ve got to do that on one leg. Whilst maintaining full balance, grace and precision. Not so easy now?

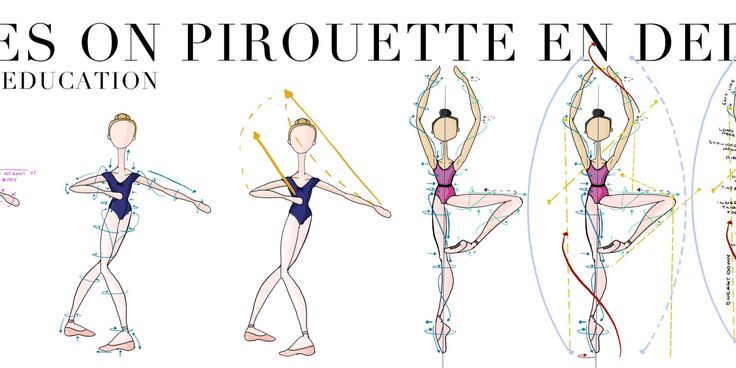

Pirouette turns can be performed “en dehors” which means turning away from the supporting leg or “en dedans” which is when you turn towards the supporting leg. Pirouettes usually start in fourth, fifth or second position.

Don’t get it mixed up – although “pirouette” means “turning” the skill and effort of achieving effortless pirouette turns has nothing to do with the rotation. Actually, the art of a pirouette comes from “spotting”, preparation, placement and balance. It’s those four components that will work together to create the magic and really master your ballet pirouette.

It’s those four components that will work together to create the magic and really master your ballet pirouette.

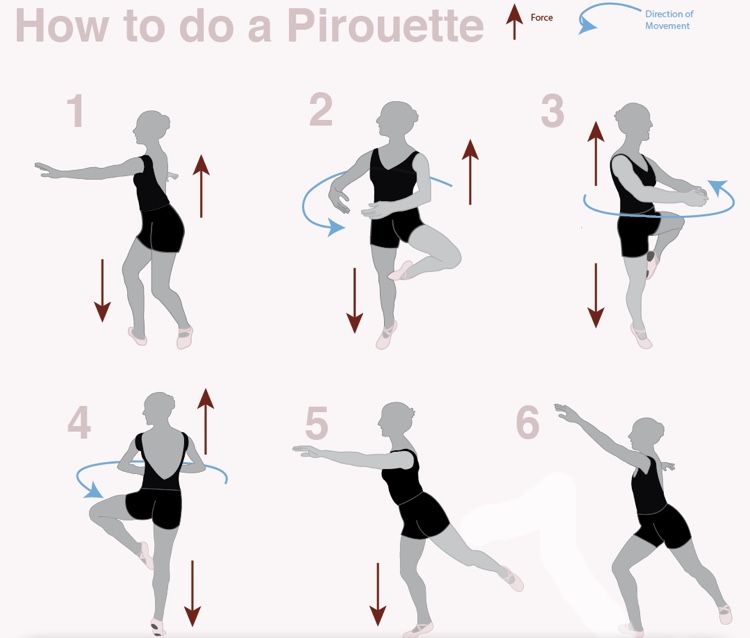

If you’re still confused as to how to pirouette and still think it’s just about the turning, let me share with you what your body should be doing during a pirouette:

- A quick yet precise relevé

- Sharp spotting with the head – focus on something on the wall and aim to get back to that spot as quickly as possible, whipping your head.

- A lengthened neck

- Eyeline raised

- Shoulders down and chest open

- An engaged core

- Arms lifted from below

- The working hip pressed down, parallel to the floor

- Pelvis tucked

- The working foot engaged and connected firmly with the supporting knee

- Stretched and straight supporting knee with the leg muscles pulled and working

- Body line directly over the line of the supporting leg

- A high demi-point in therelevé

- No rolling of the foot

If you think that’s all, unfortunately, it’s not! We’ve not even scratched the surface of how to do a pirouette yet!

Before we go through the process, let’s ensure you have all of the equipment needed to enhance your turns and complete a pirouette successfully:

-

Proper footwear – Ballet shoes, jazz shoes or turning shoes are best for practising pirouettes and it’s all about finding the best ones that are comfortable for you. You need to find a shoe that gives a good range of movement but supports well. Some dancers practise their pirouettes barefoot – this is not recommended. Over the course of time, they will cause painful calluses!

-

Proper clothing – Leotards were made for a reason, utilise them! If you’re looking for a fashionable yet sleek leotard that will make enhance your performance but still look on trend, you can check out the Zarely leotards here.

Now that we’re ready to go, it’s time to go through how to do a pirouette step by step. We’ve got the core knowledge, we’ve got the equipment – now let’s go through what you do with that information and how you can transfer it into an improved ballet pirouette technique.

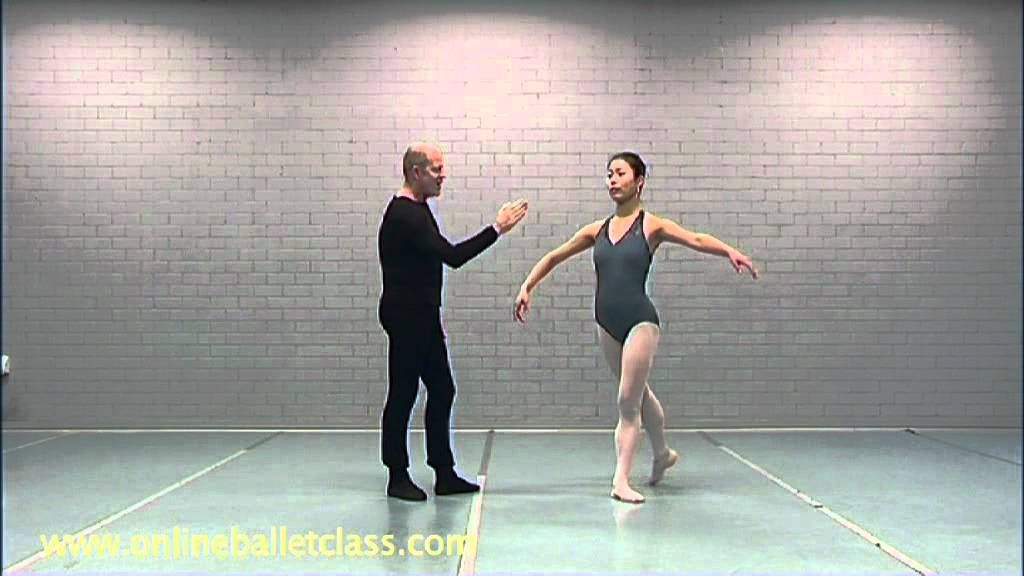

Step One – The Starting PositionThe starting position is so incredibly important. You don’t start a race before getting into the right position. You can’t start a car without getting it into the right position. It’s the same with the pirouette.

Place your feet into fourth position with both legs straight. If your right foot is in front, then the left arm should be facing the front and vice versa. Fix your eyes on a spot at eye level, or just above.

As you prepare yourself, do a quick check of the following:

- Is my head steady and focused on a immovable object?

- Are my legs shoulder-width apart with both feet parallel to one another?

- Are my shoulders pushed back?

- Is my back straight?

The correct starting position and alignment allows you to maintain your balance and stay onrelevé throughout the turn. You need to ensure that you have perfected the balance and stability. Are you able to stay put in demi-pointe and receive a gentle nudge whilst staying in place or do you collapse on the floor? If it’s the latter, it’s time to work on that balance and keep in tune with your body’s signals and make micro-adjustments to keep yourself put.

You need to ensure that you have perfected the balance and stability. Are you able to stay put in demi-pointe and receive a gentle nudge whilst staying in place or do you collapse on the floor? If it’s the latter, it’s time to work on that balance and keep in tune with your body’s signals and make micro-adjustments to keep yourself put.

Step Two – The Bending

Maintain grace and bend both legs into a deep plié. Focus on sinking both heels deep into the floor so that you can push off into your pirouette. Invision the sensation of sinking deeper below the ground, further than is possible – then give the feeling of sinking some more! But, don’t lose your positioning. Keep your eyes locked on your spotting point and concentrate on holding your body tight.

Step Three – The Spring and TurnIt’s time for the spring! You need to spring and pull yourself into retiré position as you start your turn. You relevé to demi-pointe (or full-pointe if you’re wearing pointe shoes!) bringing your back foot up to the front of your leg. Hold and maintain arms in first position. Focus on finding your centre of balance and hold that tightly. You must ensure to turn your body and legs together as one cohesive unit whilst keeping your shoulders level. Keep your eyes fixed on your spot for as long as remotely possible and then whip your head around to focus on it once more. The key to a perfect pirouette is not losing your spot. You don’t want to spend too long not looking at it. Ideally, it should be less than 0.5-1 second looking away from your spot!

Hold and maintain arms in first position. Focus on finding your centre of balance and hold that tightly. You must ensure to turn your body and legs together as one cohesive unit whilst keeping your shoulders level. Keep your eyes fixed on your spot for as long as remotely possible and then whip your head around to focus on it once more. The key to a perfect pirouette is not losing your spot. You don’t want to spend too long not looking at it. Ideally, it should be less than 0.5-1 second looking away from your spot!

Muscle power is essential for getting you doing a pirouette, but if you’re throwing your weight around in any old direction, you’ll be off balance before you’ve even begun. Focus on an upwards force of energy. Think elevation. Think of yourself pushing towards the ceiling and beyond. The lengthening will keep your aligned as you turn, whilst still keeping your grounded from the toes.

Pirouettes are about focus not force.

Step Four – Completing the TurnThere’s no doubt that you want to complete the turn just as well as you started it. After all, the audience always remembers the finish. The start might be important to us, in not only confidence but execution, but to the audience, the final part is what they remember. Give them something to talk about. Give them something positive to remember. It’s all about body posture and maintaining that position.

After all, the audience always remembers the finish. The start might be important to us, in not only confidence but execution, but to the audience, the final part is what they remember. Give them something to talk about. Give them something positive to remember. It’s all about body posture and maintaining that position.

Your body must be held straight whilst you complete the turn. Keep your core engaged and stay tight, holding in your abs. Ensure your feet are exactly in place as you turn and keep them there. Keep your legs turned out throughout the pirouette. Ensure, as you are spotting that your head completes the rotation before your body. This creates momentum and prevents dizziness.

Step Five – The Finishing PositionGive them a finale that they will remember

It’s no good having a beautiful starting position, a perfect pirouette and then finishing less so. The finish position is just as important as the start. Finish gracefully in fourth position.

- Spotting is essential!

- Keep your core engaged

- Don’t pre-empt the turn in a preparation. In preparation think about preparation to ensure you don’t unconsciously shift yourself off balance.

- The turns come from the torso, not the arms. Your arms shouldn’t be pulling you round.

- Don’t 'double plié', the transition should be smooth and a seamless motion. Don’t stop to ‘re-prepare’ or adjust the feet as it breaks the flow of motion.

- Practise. Every dancer has fallen or failed a pirouette at least once! It’s okay to get back up and try and try again.

A Turn board, or Pirouette Board, is a slim board that works on the principle of reducing friction between the foot and the floor. The feedback from dancers is mixed, so if you’re thinking about giving them a try it’s all about preference. Try it out and see if you like it.

Some dancers say they are fantastic for helping them improve their spotting and familiarise their body with the sensation of multiple turns which is great for professing to double pirouette and even triple pirouettes whereas others have said it makes the learning process more complicated and encourages bad habits. It’s also worth noting that most dancers say that Pirouette Boards have helped them feel more confidence with pirouettes and encouraged the body to get into placement for the momentum of a turn.

Related Posts

How to choose a summer intensive program

Compression and Ice – a Dancers’ best friends

Ballerina’s Choice of The Week: Katherine Barkman

How to Help Your Adult Ballet Brain Understand Rotation — Ballet Misfits

The Advantage of Learning as an Adult

One of my core drivers for this blog is the fact that adults simply learn differently than children. And while we all have great and dedicated teachers, most of them are so good because they learned ballet as a child and had a career as a professional dancer. And that’s great. I wouldn’t want it any other way. I am grateful for teachers who have been dancing for a long time and have a solid amount of stage experience.

And while we all have great and dedicated teachers, most of them are so good because they learned ballet as a child and had a career as a professional dancer. And that’s great. I wouldn’t want it any other way. I am grateful for teachers who have been dancing for a long time and have a solid amount of stage experience.

The other side of that experience is that these teachers haven’t lived through the feeling and challenges of starting ballet later in life.

Which is why, as adult ballet dancers, we have to not only be a good student, but we also need to become our own best teacher. I strongly believe that if we step into the responsibility of exploring our body, what works for us, and how we learn best - we will see much better and more sustainble progress in learning ballet.

And that, dear late party guests, is also the beauty and advantage of learning ballet at a more mature age! You have the ability to direct your learning. You are capable of what is called “meta-learning” - which basically means “learning how to learn”. Or to put it differently: You don’t have to rely on repetitions alone if you want to learn a certain skill - you can “hack” your learning to get more per every repetition. If you find that you are struggling and feeling stuck in certain areas, then that’s probably a sign that you need to approach that area from a different angle.

Or to put it differently: You don’t have to rely on repetitions alone if you want to learn a certain skill - you can “hack” your learning to get more per every repetition. If you find that you are struggling and feeling stuck in certain areas, then that’s probably a sign that you need to approach that area from a different angle.

Sometimes, literally. (Hint: This short sentence foreshadows a bit what’s coming.)

In this article, I would like to lead you through a specific example for this “learning how to learn”. And help you become a better teacher to yourself. Let’s get cozy with a common problem, a typical sticky point for adult ballet beginners and intermediate dancers: THE PIROUETTE!

So grab your coffee, relax, and turn off your phone (unless you are reading on it - then there is flight mode). I can assure you that what you are about to read will be a completely different frame of reference (again LITERALLY - the foreshadows keep dropping) for pirouettes that you will not read and hear anywhere else. It will involve some physics/mathematics. Yes I will keep it simple. But ballet is all physics so why not get comfortable with it? (I got your back, honey.)

It will involve some physics/mathematics. Yes I will keep it simple. But ballet is all physics so why not get comfortable with it? (I got your back, honey.)

The Bitchiness of Pirouettes

When I started learning ballet, I was obsessed with pirouettes. I wanted to learn them so badly, not just a single, but double and triple, please. It was probably what I practiced the most after/between classes. (Can you relate?)

But they were a struggle. While I progressed nicely with most other things, pirouettes kept coming slow. And it was very much a one-step-forward-two-steps-back kind of thing. Very inconsistent.

Pirouettes have a bit of a special status in ballet. I have heard teachers say that you can control anything, except for pirouettes. You may have heard the term “natural turner” or “non-turner” to refer to someone who just gets pirouettes and someone who never will. Or the beloved “turning days”. Pirouettes are one of the most obvious things that let you distinguish a professional dancer trained from childhood from someone who started as an adult.

But why? And are pirouettes really the exception to all things neuroplasticity?

Then two things happened.

Why all humans are made for turning

First: In a rare moment of ballet maturity I gave up my obsession around pirouettes. Maybe I was far enough into the process to realize that pirouettes are not necessarily a skill in themselves, but the result of many things coming together. Strength, muscle speed, coordination, posture, plié, passé, spot, back control etc. So I decided to give myself as much time as my tall body needed, keep working on all the other things and aim for a clean, controlled single. And I would say I am still in that process.

Second: I went through a phase of reading all the books written by Moshe Feldenkrais. (Seriously, that guy. What a genius. If you are fascinated by the human body, learning, movement etc - absorb him. Not easy reads, but worth the time and sweat.). One thing I stumbled upon in his framework was his detailing of how much the human body was made to rotate, and how that was one of the main differences and advantages compared to other animals. It’s basic physics: The specific erect posture of humans has a very small moment of inertia around the vertical axis through the body’s center of mass. It means that the body can initiate and maintain a turn around that axis more easily than most other mammals. Which is EXACTLY the axis we are turning around when we pirouette!

It’s basic physics: The specific erect posture of humans has a very small moment of inertia around the vertical axis through the body’s center of mass. It means that the body can initiate and maintain a turn around that axis more easily than most other mammals. Which is EXACTLY the axis we are turning around when we pirouette!

In other words: The human body was made for pirouettes. Turning should actually come easy to all of us!

So why doesn’t it? Or why does it come easy to some and not to others?

Here is my theory. (It’s getting juicy now, so take another sip, use the bathroom and come back.)

Turning vs. Kind of Turning, in Simple Physics

There was a simple observation I had when I was doing and practicing pirouettes: Although it was supposed to be a turn, i.e. a rotation, it usually didn’t feel like it in my body. It felt more like my body was somehow moving around on a circular path to make that turn - but it wasn’t rotating cleanly around an axis. Kind of like this:

The perfect Cat Cute SpiningAround Animated GIF for your conversation. Discover and Share the best GIFs on Tenor.

Discover and Share the best GIFs on Tenor.

So that got me thinking about rotation vs. “kind of rotation”.

In physics, in classical mechanics, you distinguish between two types of motion: Translation and rotation. Translation means that you change the position of an object - like when you move your body from one corner of the studio to the opposite corner. Rotation means that the position remains the same, but you rotate the body around an axis, like in a pirouette.

So my turn essentially felt like little translations pieced together and forced on a round path!

Now let’s add some mathematics. When you describe the motion of an object, you are typically using coordinates. Let’s say you chassé through a diagonal, then you could map every point in your body relative to a coordinate system that is given by the walls of your studio. If we are looking at you from above, here is where you would be:

So you start with the top of your head at coordinates x1, y1, and you end up with your head at x2, y2. Makes sense? This type of coordinates is refered to as Cartesian coordinates, usually denotey by x and y. They are very square, as you can see, so perfect for mapping translational motion.

Makes sense? This type of coordinates is refered to as Cartesian coordinates, usually denotey by x and y. They are very square, as you can see, so perfect for mapping translational motion.

But physics also uses another types of coordinates - they are called polar coordinates. They are perfect for mapping - you guessed it - rotation, because each point is mapped by the distance from a reference point (called radius (R)) and and angle, let’s call it alpha, relative to a reference direction. So imagine you are looking at yourself from the top again and imagine you are a good way into your pirouette:

Let’s use a schematic view of this, now imagine not being in a kitchen, but in an actual studio:

Your nose was pointing exactly in the direction of the mirror when you started the turn (let’s make this our reference direction R) and the reference point is the top of your head again, or where your axis of rotation meets the top of your head. So at the start, your nose tip’s polar coordinates were (rn, 0) and after a good part of the turn they are (rn, alpha).

So at the start, your nose tip’s polar coordinates were (rn, 0) and after a good part of the turn they are (rn, alpha).

Now here is the thing. Mathematics gives us full freedom to use whatever coordinate system we want to describe a motion. There is no rule that you have to use cartesian coordinates for describing translation and polar coordinates for rotation. BUT - it’s a no-brainer. Physics is complex enough, so you want to keep the math as simple as possible. So naturally, you would use a cartesian coordinate system to describe a translational motion, and polar coordinates for a rotation around a fixed axis.

Why? Because the nature of polar coordinates has the rotation already built into it. When you use polar coordinates to look at the motion of a specific point (like the tip of your nose) during a rotation around a specific axis - one of your coordinates, the distance from the axis, DOESN’T CHANGE!

And, as a general rule, the more that does NOT change in physics and maths, the easier your life. (So in a sense, it’s like real life: There is enough change anyway, so you try to hold on to your constants.)

(So in a sense, it’s like real life: There is enough change anyway, so you try to hold on to your constants.)

I mean, just imagine how ugly it would be to use cartesian coordinates for the same pirouette you were just doing:

See how NOT elegant this is? BOTH your x and y coordinates would keep changing during the rotation.

You’re like - ok, yes, whatever, how is this connected to nailing pirouettes??

How to Make Your Brain Spin

So here is the next step that I need you to make in understanding pirouettes right now. Let’s bring your brain to the party, very literally again.

Essentially, your brain is doing what my beautiful (haha, thank you) drawings above were trying to accomplish: It’s mapping your body’s coordinates, like All. The. Time. when you move. It keeps track of where you are in space, and where differents parts of your body are when you rotate. It’s like constant GPS firing, mapping, adjusting, remapping.

And here is the final pirouette wisdom bomb drop, the core of this framework:

You can get stuck in learning pirouettes because your brain is doing the equivalent of using the WRONG coordinate system to map your turn.

Or, a little different: You can think of the “non-turner”s brain as using cartesian coordinates to keep track of everything during a pirouette - while the “turner”s brain is mapping the turn in polar coordinates. So the non-turner’s brain is working twice as hard and still ends up with a pirouette that feels and looks more like a linear motion forced on a circular path (like that white cat above) - whereas the turner’s brain has a lighter load and comes out with a true rotation.

So the more educated question to ask now: But why do not all brains choose the more elegant coordinates?

Although I don’t know for sure, my guess is that it depends on how well someone can establish that fixed axis that is so required for a turn. Creating that axis depends on experience, posture, and proper muscle activation - you basically need to keep a good inner part of your body very still = your axis, and you want to keep the rest of your body as close as possible to that axis. Even a hyperextended back can mess with that.

Even a hyperextended back can mess with that.

And then it probably also depends on how much the body was exposed to rotating from an early age. My (admittedly very speculative) guess is that in Feldenkrais’ times, rotation was more part of your general life. Kids would naturally do turns during outdoor play and physical education, and dance was more part of the general culture etc. Not so much nowadays - or do you casually and frequently rotate around your vertical body axis except in ballet class?

I am glad you are still with me. This is profound, and I will explain how that has practical applications for improving your pirouette in a moment. But before, let me add that of course your brain is not literally mapping lists of x,y or r,alpha coordinates. The coordinates that I introduced are simply a model of how clumsy or effortless the brain determines where everything of you is when you are in motion. What this implies is that some brains are more efficient at doing it - while others have to make a more conscious effort of getting there, too!

So that brings us to: How can I use this knowledge for a free, practical pirouette upgrade?

Practical steps to help your brain figure out pirouettes

So the practical implication here for all of us turn-learners: You basically have to train your brain to switch from Cartesian to polar coordinates when you are making any kind of turn!

Here are the steps that I have started taking recently and that have made a difference for me:

Start with THINKING about this concept.

Very conscious Thinking is a powerful trigger for neuroplasticity. If you are a physicist and this was just kindergarten for you - great. Indulge in what you know about rotational mechanics and polar coordinates. If you are not, and had trouble following, reread until you get it. Or email me with your questions. In your mind, see yourself from above (or below) and think about how your top of the head rotates (or your passé knee, if you look from below), and how the distance to the center of the rotation stays the same, not matter what you are looking at (=mentally imagining). Think about the switch from clumsy Cartesian to pretty Polar that is about to happen in your brain.

Very conscious Thinking is a powerful trigger for neuroplasticity. If you are a physicist and this was just kindergarten for you - great. Indulge in what you know about rotational mechanics and polar coordinates. If you are not, and had trouble following, reread until you get it. Or email me with your questions. In your mind, see yourself from above (or below) and think about how your top of the head rotates (or your passé knee, if you look from below), and how the distance to the center of the rotation stays the same, not matter what you are looking at (=mentally imagining). Think about the switch from clumsy Cartesian to pretty Polar that is about to happen in your brain.The key in switching from translations-on-a-circular-path to a true rotation is building and becoming aware of a strong axis. You need to understand that there is this long part of your body, from head to toe, that is actually NOT MOVING AT ALL during a pirouette. And it cannot move before, in the preparation.

It cannot suddenly bend in your plié. Your axis needs to stay the same, no matter what. You need a very still center.

It cannot suddenly bend in your plié. Your axis needs to stay the same, no matter what. You need a very still center.Having this idea of an indestructible axis will help you integrate your teachers corrections into a coherent picture. And that’s always helpful for the brain - to think big pictures, in muscles chains, rather than spots here and there. So “don’t bend at the waist as you plié”, “don’t hike up your hip in passé”, “keep your hips turned out in plié”, “keep the shoulders on the same level”, “extend your standing leg”, “maximum demi-point”, “push into the floor”, arm position etc: All these cues feed a strong axis!

Observe good turners in class. See if you can “see” their axis. I find that good turners keep their axis even if they fall, i.e. their axis may tilt (=it may angle towards the floor) - but it never disintegrates (=bends somewhere in between). Observing and feeling the observation in your body can also be a strong trigger for new firing patterns in the brain.

The last, and also the hardest step, is to start feeling your own axis. You start by just standing, becoming aware of it, and just mentally imagine that axis. You can then proceed to very slowly rotating on two legs flat, allthewhile trying to sense that axis part of the body that just remains still. The final move is to start looking/feeling the axis as you do your pirouette. It’s hard. You will forget, because as you turn, your brain feels like a black hole. It doesn’t matter. Just keep reminding yourself, even if it’s not during, but just before the exercise.

Generally: Mental practice is HUGE. We have enough evidence to know that your brain does not care much whether you actually do something or just imagine it. I mean, this is just such a cheap way of getting more repetitions, it’s almost like stealing. But then again it’s not, because your brain has an endless supply of repetitions to imagine. As long as you are alive, that is. For some of us even after.

So…..let’s wrap this up.

Be patient and enjoy!

First, a fair warning/reality-check: This is not a quick process. It may take months until neuroplastic changes occur and you feel consistent changes. And there is a chance that this way of looking at pirouettes simply doesn’t work for your brain. All you can do is give it a shot for some time, and see if it helped you. Especially if all else has failed you so far. And maybe you find out that you need an even different angle on this - which would also be a successful result of this process.

(I also want to add that building an axis is not the only thing that makes a pirouette. I would say it is a basic requirement. But of course you also have other things that will determine the quality of the turn: Mainly, how you accelerate different body segments into the turn and how you spot. But we’ll leave that for other posts.)

And last: Great job! This was maybe not the easiest food for thought, but you made it through. Thinking about stuff like this is a big part of becoming your own teacher. And not just any teacher, but your most supportive one as well. You can now turn your phone back on. Enjoy your time on the dancefloor!

Thinking about stuff like this is a big part of becoming your own teacher. And not just any teacher, but your most supportive one as well. You can now turn your phone back on. Enjoy your time on the dancefloor!

Playing with this concept is already having an effect on my pirouettes. I can’t say if they are getting consistently better, but to me it feels like I understand better how to activate my torso in order to create a solid axis. I am so curious to hear whether this view on pirouettes was helpful at all to you? And if you start playing with it - please share your observations! What changes when you think “axis” and rotating around it? Please comment here, or on IG at @balletmisfits or email me at [email protected]!

Adult-Tailored Technique, Learning/NeuroplasticityPatricia Pyrkaadult ballet, pirouettes, spotting2 Comments

0 LikesRotations and turns in dancing (practice)

- Posture

Rotations are performed with a taut and even body, "coccyx retract", "long neck", chin looks up. This will help you balance and tighten the axle needed for long term spins.

This will help you balance and tighten the axle needed for long term spins.

- Dot

All dancers know to "hold the dot" to spin, but I wonder if you can change dot fast enough? In order to rotate long and hard, you need to train a sharp and lightning-fast change of point. The point should be kept at the level of your eyes and a little higher. Don't look at the floor or you'll end up there.

- Alignment (cross)

Concentrate on aligning the line of the shoulders with the line of the pelvis, they should be parallel. If you do not align the lines of the shoulders and pelvis during the beginning of the rotations, you will not be able to catch the balance and your rotation will not be long, a maximum of 3 pirouettes. To do this, you should train in front of a mirror, stand in a relevé and make sure that the lines of the shoulders and pelvis (hips) are parallel. Also, in front of the mirror, you should control the position of the body, become sideways and make sure that you are not leaning forward or leaning too back.

Also, in front of the mirror, you should control the position of the body, become sideways and make sure that you are not leaning forward or leaning too back.

- Balance

When pirouettes, you balance on a half-finger (relev), practice balance without rotation. If you can’t stand on a half-finger without spinning, then you won’t be able to stand in a turn either. Practice balance on half toes without rotation, train both the left and right foot, you should stand eight counts at a very slow pace, this will strengthen your axis. What type of spin do you train, classic turnout or jazz closed? Practice every type of balance until you can, it will come in handy in your career as a dancer, modern show groups use all kinds of techniques.

- Your thumb

Where does your thumb point when you rotate it? If your finger is not pointing in the same direction as your knee, this rotation is not considered correct and you will not be able to achieve a multi-spin. Stand on your half-finger and make sure you don't "clubfoot" that your thumb is pointing in the same direction as your knee. There is nothing worse than a clubfoot dancer! If the foot is placed correctly, the weight is also distributed correctly and you will be able to build the best axis for rotation. Make sure that during the rotation you do not jump on the half-toe, do not "play" up and down and your instep is stretched as much as possible. Throughout the rotation, you should stand on the maximum possible half-finger.

Stand on your half-finger and make sure you don't "clubfoot" that your thumb is pointing in the same direction as your knee. There is nothing worse than a clubfoot dancer! If the foot is placed correctly, the weight is also distributed correctly and you will be able to build the best axis for rotation. Make sure that during the rotation you do not jump on the half-toe, do not "play" up and down and your instep is stretched as much as possible. Throughout the rotation, you should stand on the maximum possible half-finger.

- Use the dance floor (parquet)

Push off the deep plié floor with all your strength to set the maximum possible rotational energy. Imagine a Devil in a Box spring toy, you push it down into the box and when you open it, it kind of shoots up with maximum force, while you direct this energy into rotation with your hands. Push off from the plié with enough force to get on your half toe and extend your knee, and of course not more than necessary, otherwise you can not resist. Also, there is a technique in which, during the performance of the plie, the dancer exhales and then briefly inhales during the first turn, which allows you to increase the moment of rotation using an additional force.

Also, there is a technique in which, during the performance of the plie, the dancer exhales and then briefly inhales during the first turn, which allows you to increase the moment of rotation using an additional force.

- Matching shoes

Depending on the choreography, wear specialized dance shoes. It is not recommended to do rotation without shoes, you can comb the skin on the balls of the feet.

- Arms

Have you noticed that when doing a series of pirouettes, the arms are closer to the body in subsequent turns than in the first turn? Quite right! During a series of pirouettes, it is very important not to lose the energy of rotation, for this the dancer must skillfully collect his hands to the body, distribute energy for each turn, so that in each subsequent turn the hands are a little closer than in the previous ones. Try it in practice, if you do not bring your hands together, then the rotation will not be fast and not long, but if you sharply take your hands to the body, then you will sharply spin at a higher speed. Now that you know what to do, you should train the most important condition - while bringing your hands together, hold the "cross" (the line of the shoulders and the line of the pelvis should be parallel).

Now that you know what to do, you should train the most important condition - while bringing your hands together, hold the "cross" (the line of the shoulders and the line of the pelvis should be parallel).

- Pulling

Imagine that while you are spinning, someone is pulling you up by the top of your head. This will allow you to keep a straight axis and rise as high as possible on the half-finger with the involvement of the main muscles of the body.

- Practice

Pirouette, like a circus trick, performing a series of pirouettes requires long hours of regular practice.

"When I was preparing to break the world record, I worked out at least three days a week for several hours. And it took about a year for me to start rotating from 19up to 55 turns without stopping" - says Lucia Sofia.

What is a pirouette in dance?

Classical dance has a number of fundamentals, which include clear, set positions of arms and legs, practiced jumps and synchronized rotations that connect movements. By combining the listed movements

By combining the listed movements

What is a pirouette? In the theater, a pirouette is a turn during a jump in the air. Among experts in hippology, a pirouette is usually understood as a turn of a horse on its hind legs. It should be noted that this expression is often used in a figurative sense, when a pirouette is someone performed a cunning trick The term itself is taken from French.

Pirouette direction of rotation

Most rotations are performed in both en dehors (outward) and en dedans (inward) directions. Rotations en dedans are made in the direction of the supporting leg (i.e. on the right leg to the right, or on the left leg to the left), rotations en dehors are done in the direction opposite to the supporting leg (i.e. on the right leg to the left, or on the left leg to the right) . In some movements, the direction is not set: for example, tour soutenu with a change of legs in V position can only be performed towards the leg standing behind, while tours chaînés are performed sequentially along half a turn (i. e. 180 °) first en dedans, then en dehors.

e. 180 °) first en dedans, then en dehors.

Coordination in the turn

Movement is assisted by the active movement of the hands that force the rotation - the so-called "pick up". The work of the head is also important: thanks to its lagging behind, and then advancing the movement of the body, the gaze is fixed for as long as possible on an arbitrarily chosen point in front of it.

The pirouette is very different from other single leg rotations. Before its execution, the so-called force [French. Force - strength] - due to acceleration, preliminary twisted in the opposite direction, torso, arms and free leg. During the rotation itself, the head moves in a special way. The performer's gaze is fixed on the auditorium in such a way that the head lags behind the general rotation of the body, and during the maximum lapel of the body, a quick, anticipatory turn of the head follows, and the gaze is again directed to the center of the auditorium.

Pirouette in ballet - when a ballerina rotates around an axis on half-toes or toes of one foot. They are divided into small and large. The first includes such rotations when one leg is pressed tightly against the other, no matter in front or behind. The second - when the movement is performed in various basic poses.

Pirouette Technique

A perfect pirouette is achieved by:

- A well aligned chin. The line of the chin during the turn should be kept perfectly level and parallel to the floor.

- The back of the head, neck and spine, which must be in line. In the general state, the obligatory presence of a sense of confidence and stability.

- An ideal turn, during which you need to keep your hands, like the whole body, tense, like a spring.

- Accurate and timely bringing the leg to the desired position and a sharp push.

- A graceful turn, during which a feeling of strength and victory comes.