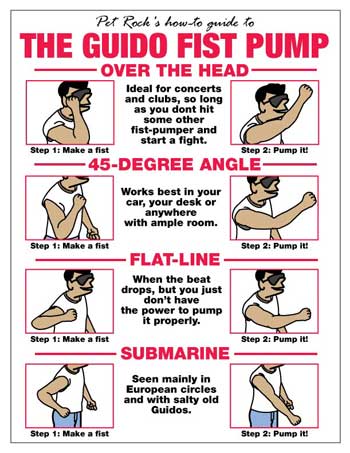

How to dance like a guido

Guido Music: A Brief History

Posted inArtby Avery

Three years ago, I went to a friend’s record release party at a club in New York City. In an adjacent room, there was a DJ playing Noel’s “Silent Morning“. I walked in, listened to this Classic record at full club volume, and it was like hearing it for the first time. I being not old enough to hear this record in a club when it first came out understood immediately why this music became huge in the first place. It is tailor made for a dance club. Massive bass and infectious rhythms assault you at every moment. Do you know what freestyle music is? I’m not talking about it in the hip hop “freestyling” sense. I’m talking about an extremely important and often overlooked branch of electronic music that emerged in the early eighties in New York City. It began with a record called “Planet Rock” by the legendary Godfather of hip hop Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force.

BAM revolutionized hip hop by incorporating drum machines over samples, a practice which remained the dominant approach to hip hop production until the early 2000’s. No one was doing the drum machine thing at the time, and the drum machine is now so essential to hip hop it would be unthinkable without it. When “Planet Rock” came out in 1983, it became one of the most influential records of all time. On the one hand it was the only hip hop record at the time to use a drum machine, and on the other hand it birthed a new genre of music. That music was Freestyle.

The beat that BAM created, was quickly recycled with one major change. Instead of rapping on the beat there was singing, and that change was enough to warrant a new genre. The amazing thing about genres is that they are sometimes created by musicians who did not have any intention to create one. Obviously James Brown is as important to hip hop as Bam is to Freestyle. Neither knew that aspects of their sound would create these huge musical movements. Planet Rock was so infectious that when it came out almost all the hip hop records emerging from NYC sounded like it. It is what the clubs and roller rinks sounded like in the early eighties.

Neither knew that aspects of their sound would create these huge musical movements. Planet Rock was so infectious that when it came out almost all the hip hop records emerging from NYC sounded like it. It is what the clubs and roller rinks sounded like in the early eighties.

Some would cite Shannon’s “Let the music play” as the first freestyle record. A case might be also made for “Play at your own risk” by Planet Patrol, though the Shannon record went on to be a massive hit and an all-time classic. At the time, these records would have been more likely classified as “electro”, another spawn of BAM’s genius. These records were played heavily by Latino DJ’s. Though the music had it start with mostly African American performers, Latino’s, mostly of Puerto Rican descent took this sound and incorporated their own musical influences, rhythms, and approach to the music and the rest is history.

v

It was at this point that the music began being termed “Freestyle”. In the mid-eighties New York, Miami, and LA, were the only markets that heavily catered to this music on the radio airwaves. It was not until the late eighties that more mainstream acts like Expose and Sweet Sensation brought the sound to a larger audience. However some would consider Expose and Sweet Sensation “Club” music. But “Club Music” was less of a genre and more of a word that described this sound. This word described a more watered down mainstream version of the music that came shortly before it. Oddly enough

It was not until the late eighties that more mainstream acts like Expose and Sweet Sensation brought the sound to a larger audience. However some would consider Expose and Sweet Sensation “Club” music. But “Club Music” was less of a genre and more of a word that described this sound. This word described a more watered down mainstream version of the music that came shortly before it. Oddly enough

Freestyle music, created mostly by Puerto Ricans, was heavily identified with Italian Americans in New York City, to the point where I have heard people calling it “Guido music”. Anyone who was born in New York in the late seventies or early eighties that had left their window open knows what this music sounds like.

Why is this important? In the mid to late eighties Freestyle was the dominant dance music in New York. In the nineties mainstream “dance” music borrowed heavily from freestyle and WKTU in New York became the most listened to radio station in the city. Listen to Le Bouche’s “Be My Lover“, a song heavily influenced by freestyle though categorized as “Eurodance”. This record is the link between freestyle and the modern mainstream dance music world. Any Ibiza DJ spinning trashy Eurodance/Pop/Dance is spinning music heavily influenced by freestyle whether they know it or not.

This record is the link between freestyle and the modern mainstream dance music world. Any Ibiza DJ spinning trashy Eurodance/Pop/Dance is spinning music heavily influenced by freestyle whether they know it or not.

And now I leave you with my favorite freestyle record of all time. Lil Suzy, a Brooklyn native of Puerto Rican and Italian descent (duh), put out “Take Me in Your Arms” at the ripe age of twelve.

Tagged: 80s, 90s, Brooklyn, club, dance, DJ, freestyle, hip-hop, music. history, new yorkMichael Cera's 'guido makeover' made Jersey Shore history and fans want him back

WESTWOOD, CA - AUGUST 09: Actor Michael Cera arrives at the premiere of Sony's "Sausage Party" at Regency Village Theatre on August 9, 2016 in Westwood, California. (Photo by Gregg DeGuire/WireImage)

Fans of the infamous MTV show, Jersey Shore, have been reminiscing over the time when Youth in Revolt and Superbad star, Michael Cera, spent his day at the Shore with Snooki, Pauly D and the crew, getting turned into a proper “guido. ”

”

Michael seriously wanted to spend some time with the Jersey Shore cast and his dream came true back in 2010 – and the pictures speak for themselves. Cera’s time on the shore was loved so much by fans that they want the actor to be a part of the Jersey Shore Reunion.

- RELATED: Jersey Shore’s Angelina Pivarnick ‘dating’ Vinny, 19, who lives in her garage

Wild Croc Territory | Official Trailer | Netflix

BridTV

11292

Wild Croc Territory | Official Trailer | Netflix

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/0UFcnWpBHxU/hqdefault.jpg

1098773

1098773

center

22403

Photo by Larry Busacca/Getty ImagesMicheal Cera’s “guido” transformation

After they had all introduced themselves, Pauly D gave Cera his signature blowout, an impenetrable style that takes him nearly half an hour to sculpt. The reality star told PEOPLE: “Greatness takes time, and this hair right here is greatness.”

He then got given an Ed Hardy T-shirt in traditional Jersey Shore style and it was unusual compared to Cera’s traditional checkered shirts. Vinny then initiated Cera (and his new look!) into the fold with a proper Jersey Shore welcome.

Vinny then initiated Cera (and his new look!) into the fold with a proper Jersey Shore welcome.

During the episode, Cera put his new look to good use as he hung out with Snooki and Sammi in true Jersey boy style, putting his charm and flirting skills to good use.

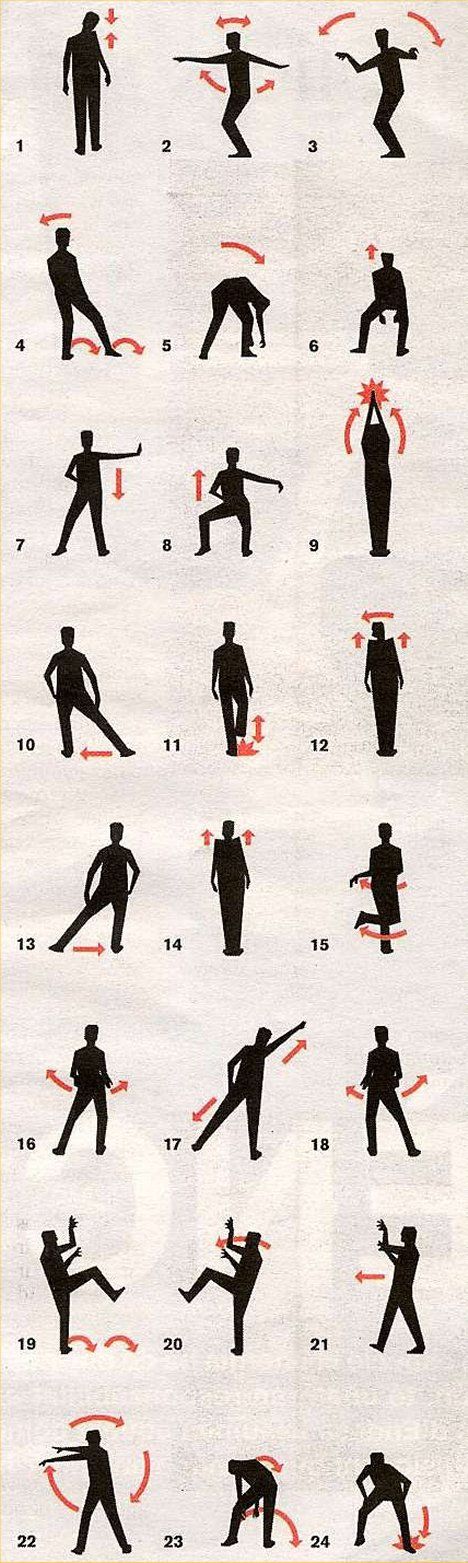

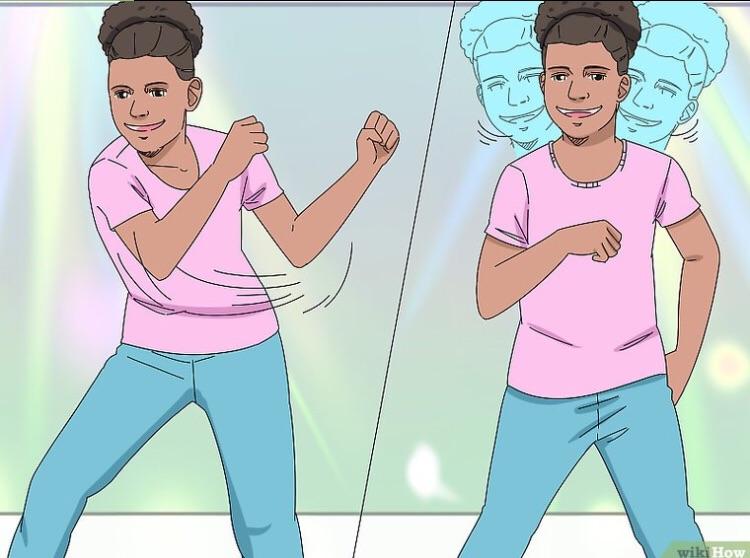

Cera was taught how to dance like a guido in the promotion of his film

It wasn’t just a makeover that Cera was treated to during his trip to the shore, he also got to learn how to be a true guido.

Cera enjoyed a few intoxicating beverages with the cast and was treated to a masterclass in dancing led by Pauly D, Vinny and The Situation before concluding his time with the reality show with a quintessentially Jersey Shore soak in a hot tub.

Just rewatched the videos of when the jersey shore cast turned Michael Cera into a guido and It’s still hilarious 🤣

— Gabriel Rubio©️ (@SiirNapsAlot) September 11, 2022

View Tweet

As comfortable as Michael was with the Jersey Shore gang, he didn’t have plans on joining the cast or ditching his acting career for reality TV stardom during his appearance. His cameo was actually part of an MTV special created to promote Cera’s then-upcoming movie Youth In Revolt.

His cameo was actually part of an MTV special created to promote Cera’s then-upcoming movie Youth In Revolt.

As strange as Michael Cera’s cameo was, it looked like he had a great time mixing with the cast.

does anyone else ever find themselves thinking about the time michael cera hung out with the cast of jersey shore pic.twitter.com/Xxu3LWalSV

— official trustbusters stan account (@trillmoregirls) August 12, 2021

View Tweet

- RELATED: Jersey Shore fans think Angelina Pivarnick looks like Kim K’s twin after nose job

Fans think Micheal should be on the reunion

Fans of the show loved Michael’s cameo so much that they were demanding for him to be featured on the Jersey Shore reunion. One person on Twitter recently said:

“I demand a season of Jersey Shore Family Reunion with Michael Cera, but instead of being himself, he’s in character as George Michael the entire show and Jenny winds up having affair with him.

”

Another fan keenly said: “honestly Michael Cera should’ve been a part of the jersey shore family reunion.”

With Michael being such an avid Jersey Shore fan he probably would have loved an invite to the reunion. Maybe next time, Micheal.

honestly michael cera shouldve been a part of the jersey shore family reunion

— who, me? (@farfallinaaa_) June 29, 2018

View Tweet

WATCH JERSEY SHORE FAMILY VACATION ON MTV EVERY THURSDAY AT 8/7C

AND GET FREAKY WITH US ON INSTAGRAM, FACEBOOK, TWITTER AND TIKTOK

Jersey Shore fans love ‘OG’ Uncle Nino even more after heart to heart with Angelina Meet the Challenge Ride Or Dies 2022 contestants“Guido's Exercises and Dances” - Articles - Music

With all the formal signs of opera - music in its vocal and instrumental embodiment and stage action, this work cannot be called an opera with a clear conscience. Rather, it is a musical and dramatic declaration by the author (and Vladimir Martynov also owns the libretto) on the theme of “opera at the end of the opera”. Perhaps “Guido” is a more conceptual work than a musical one.

Rather, it is a musical and dramatic declaration by the author (and Vladimir Martynov also owns the libretto) on the theme of “opera at the end of the opera”. Perhaps “Guido” is a more conceptual work than a musical one.

If we try to formulate it even more precisely, then the whole idea of this work boils down to the fact that musical notation, invented at the beginning of the 11th century by Guido Aretinsky, became the beginning of the path to the desacralization of music. This thought - a message to the listener before the start of the performance was aphoristically expressed by the stage director Georgy Isahakyan, speaking about the dramatic paradox of Guido, "when what you create destroys what you are doing it for." True, it seems that this formula was more related to the performance itself than expressed its personal position.

Photo: Theatre. N. Sats

Actually, the opera “Guido’s Exercises and Dances” is an artistic realization, a kind of expression of Vladimir Martynov’s own views – not only a composer, but also a philosopher and specialist in the field of liturgical music – on the place and historical path of European musical art generally.

And the stylistically recognizable music of V. Martynov, “constructed” from the minimalist patterns natural to him, is valuable not in itself, as the author’s music in the European classical system of values of the last five centuries, but as a brilliant illustration of the idea declared by the author. Moreover, the dramatic development of the opera takes place not at the level of the libretto, but on the subtlest stylistic changes, inclusions and details of the score with rhythmic and harmonic anachronisms masterfully inscribed inside the stylistically impeccable musical fabric, inside the musical material that draws the world of Gregorian chant through the eyes of a person of the late 20th century. (the opera was written at 1997). And closer to the end of the performance, these stylistic changes, picked up in the stage implementation by G. Isahakyan, become brighter and more noticeable, demonstrating the author’s idea of the spiritual degradation of musical art, starting from just that very historical fork in the first half of the 11th century.

Photo: Theatre. N. Sats

Georgy Isahakyan, as usual, did the impossible - he gave a stage form to a speculative work, in essence, of an oratorio type with no dramatic collision in the relationship between the characters, and written, moreover, in Latin, since, according to According to the author, "the words in the opera are still incomprehensible to anyone."

The opera was staged not on the main stage of the theatre, but deep behind the scenes, in the space of the painting workshop, which in the course of the performance acquires the features of a temple volume, and the technical niches in the wall with the help of projection become stained-glass windows in the narrow windows of the Gothic building (artist Valentina Ostankovich , lighting designer Evgeny Ganzburg). And for the public, the action begins already when, after the first bell, they are led along the long winding corridors of the theater to this technical room, which became a stage platform for the duration of the opera.

Photo: Theatre. N. Sats

The entire performance as a whole is constructed from several interconnected musical elements and actors. First of all, which is natural for a work based on the musical and civilizational principles of the 11th century, this is a male choir. The choir (choirmaster Vera Davydova) works wonders. The tasks set before him are extremely complex - this is musical material that is inconvenient for learning by heart, this is the use of the entire volume of several adjacent technical rooms, as a result of which the parts of the choir are at a great distance from each other, these are a capella fragments of considerable size that require special attention to intonation, this is the performance of four-voice chorales in a technique stylized as archaic and the principles of vocalization of a different type arising from this, and much more.

The chamber composition of the orchestra (those are strings and two synthesizers) has no less difficult tasks, because the performance of V. Martynov's music requires not only quite high purely physical loads for the performer (and it is very difficult to perform one and the same rather primitive chants), but also an increased concentration of attention with an extremely transparent score and serious requirements for intonation.

Martynov's music requires not only quite high purely physical loads for the performer (and it is very difficult to perform one and the same rather primitive chants), but also an increased concentration of attention with an extremely transparent score and serious requirements for intonation.

Photo: Theatre. N. Sats

Musical director and conductor Alevtina Ioffe led the performance in her characteristic somewhat hypertrophied energetic manner, and here it was absolutely justified, due to the absence of semitones in the material itself, despite the fact that the rhythm in Martynov’s musical style in general and, in particular, in “Guido” , is one of the most essential elements. In addition, she was faced with the task (however, impeccably executed) to link into a single rhythmic whole an orchestra, a choir spaced tens of meters apart, and soloists who, on anniversaries, due to the very texture of the material, sometimes failed to stay within the rhythmic grid.

Photo: Theatre. N. Sats

The theatre’s production featured an acting hero without words, absent in the opera’s libretto – Guido himself (Mikhail Bogdanov), a type of monk-encyclopedist who cognizes the world, reminiscent of Faust in the first place. G. Isahakyan managed to introduce an element of irony into this extremely serious opera - the sequence of Guido's laboratory research in the field of acoustics, physics, chemistry and anatomy, which functionally performed the role of a “mental” intermezzo in the middle of the production, gave the viewer the opportunity to take a breath. Given that in a laboratory of any type, the choir sings already familiar to everyone ut, re, mi, fa ...

On stage, this episode looks like a cascade of gags - tables with another thematic set of props roll out onto the stage one after another.

Chemistry Lab are flasks of various shapes with extremely decorative reagents in Asiatic acid color tones which, when mixed in any combination, give off a picturesque smoke.

Photo: Theatre. N. Sats

An electrical cabinet with instruments in the style of the 50s from a school laboratory or museum demonstrates an electric discharge between balls and lightning to the delight of the public.

An autopsy in an anatomical theater demonstrates the indisputable fact that a person is ninety percent cut paper, and so on.

At the same time, in a laboratory of any type, the choir continues to sing the already familiar ut, re, mi, fa ... Everything else performed in Latin, as the author rightly noted, is meaningless, despite the fact that these are fragments of texts by Guido himself, St. Bonaventure, etc. This is the concentration of postmodernism.

Photo: Theatre. N. Sats

Actually, there are only three vocal parts in the opera. These are two Muses and "assistants" - Mezzo-soprano (Julia Makaryants) and Soprano (Albina Fairuzova). In a dramatic sense, they are, in fact, two incarnations of one character. Their duet, which went through the entire performance, was a virtuoso both on stage and vocally, not to mention the acting charm and almost demonstrative pleasure from the parts they performed.

In a dramatic sense, they are, in fact, two incarnations of one character. Their duet, which went through the entire performance, was a virtuoso both on stage and vocally, not to mention the acting charm and almost demonstrative pleasure from the parts they performed.

And, perhaps, the maximum vocal load fell on Sergei Petrishchev (Tenor) - his part is not only extremely large in volume, it is technically and simply physically difficult due to the large number of melismas sung. In addition, the very style of the performance of the Tenor part is gradually changing from Gregorianism to a kind of parody of Freddie Mercury, while maintaining the basic principles of the musical material itself (the context and elements of texture and harmony in the orchestral score change), thereby confirming the concept of the entire work. And S. Petrishchev smoothly "drifts" from the image of a chorister in the church to the vocalist of the era of pop culture.

Photo: Theatre. N. Sats

But at the very end of the opera, after a series of musical numbers, each of which is perceived as the final one (this, apparently, is the result of some miscalculations in the field of musical form), there comes an inner enlightenment, a kind of scene-demonstration of that how it could have been if the musical history had taken a different path - the monks with childish amazement looked at the model of the monastery brought on a cart with luminous windows to the sounds of the celesta, the heavenly timbre of which appeared in the opera for the first time, as if illustrating the gospel verse “... if you don’t like children you will not enter the kingdom of heaven.”

Exercises and dances Guido

Exercises and dances Guido

If we look at the work of Vladimir Martynov from a position where the composer seems to test the strength of traditional genres, interpreting them polemically and breaking down the barriers between academic and non-academic forms of art, then in the symbiosis of stage and plein air, temple and concert hall, writing table " a theologian-researcher in sounds” and a music stand with scores for future actions, it seems that there was not only an opera theater, alone or, again, in symbiosis with something.

And then comes the opera Exercises and Dances of Guido (1997). Commissioned by the Sacro-Art-97 festival held in Lokkum (near Hannover, Germany), it is an original embodiment of the idea of a “new sacred space”. Originality, in fact, in the conceptualist strategy. The name is paradoxical, even provocative. Latin text. The genre is controversial. Journalists guessed: opera, para-opera, meta-opera, someone even suggested “anti-opera”. The composer specifies: "an opera about an opera".

Conceptually, first of all, the libretto written by the composer himself. The multi-layered text structure is built from fragments of two medieval Latin treatises - St. Bonaventure's "The Soul's Guide to God" of the 13th century and the Milanese verse treatise on the organum of the anonym of the 11th-12th centuries. Another fundamentally important source, after whose author the opera is named, is Guido d'Arezzo's Letter to Monk Michael about Unfamiliar Singing. The term "unfamiliar singing" (ignotus cantus) refers to sight-singing invented by Guido Aretinsky. In a special place is another source - the first stanza from the famous Latin hymn to St. John the Baptist. This text can be considered the key, it can be likened to the main character of the opera.

In a special place is another source - the first stanza from the famous Latin hymn to St. John the Baptist. This text can be considered the key, it can be likened to the main character of the opera.

Martynov found conceptual links between all these texts. The structural basis is taken from the "Guide of the Soul to God" by St. Bonaventure. This is a theological study-meditation, the fruit of the refined intellectual and spiritual asceticism of the medieval Franciscan scholar. The path of the soul is described by St. Bonaventure as six steps of ascent to God. Treatise of St. Bonaventure, like its structure, serves as the semantic and formative foundation of the opera. Its six chapters (six steps) determined the six-part structure of the central section of the opera, called "Exercises". From the Milan treatise on the organum, Martynov took only one, but conceptually important, fragment in which a medieval anonymous author describes the counterpoint of two voices: in the opera, this fragment symbolizes the beginning of the composition. Here is the snippet:

Here is the snippet:

“In anticipation of a conversation, two friends meet with such sympathy, which occurs only in the closest friendship. The first leads the other and, as a sign of friendliness, gives her a quart, and she, in turn, a fifth, and both together give an octave.

Finally, the "Epistole" of Guido Aretinsky presents a famous treatise in which the scientist sets out his theory and his system of singing by hand. The invention of musical notation by Guido Aretinsky was a direct consequence of the theory of the hand, the theory of solmization, according to which each sound is comprehended as a point, punctus, and, consequently, as a step (vox, locus), functionally different from neighboring steps. The stepped theory of medieval modality formed the basis of musical notation. This is a step forward in comparison with the non-intellectual writing, which reflects the singing - formulaic, combinatorial - thinking. Guido's notation captures not solid neumes-idioms, in which sounds are merged into chants, but rows of point-sounds that can be systematized into an abstract non-singing, non-intonation step musical alphabet - Guido's ladder, that is, a hexachord. Thinking, formatted by a new technological - point principle, turned out to be free from the theological primary source of singing in favor of physical objects - sounds and their combinations, in order to construct new physical objects. In other words, engage in composition. Guido used an acrostic from St. John the Baptist, deciphering the live chant into syllable-points, which make up the abstract scale of the six-step scale - the Gvidon hexachord.

Thinking, formatted by a new technological - point principle, turned out to be free from the theological primary source of singing in favor of physical objects - sounds and their combinations, in order to construct new physical objects. In other words, engage in composition. Guido used an acrostic from St. John the Baptist, deciphering the live chant into syllable-points, which make up the abstract scale of the six-step scale - the Gvidon hexachord.

Ut queant laxis

Re-sonare fibris

Mi-ra gestorum

Fa-muli tuorum,

Sol-ve polluti

La-bii reatum,

Sancte Johannes.

Guido's dotted linear notation, invented for sounds, became the basis of European composition as it is understood today. As Martynov commented, "as a result, we got the opportunity to compose music, but we lost the integrity of religious consciousness." All the music that follows is presented as "Guido's exercises and dances". When I asked why “Guido’s dances” appear in the title, Martynov explained: “Guido returned corporality to music in the ancient understanding of sound instead of angelic dances - mental. ” The answer to the fragment from Guido's letter is the passage cited above about the harmony of fifths and fourths from the poetic treatise of Milan.

” The answer to the fragment from Guido's letter is the passage cited above about the harmony of fifths and fourths from the poetic treatise of Milan.

The opera is plotless, or rather plot-driven, but not in the narrative, event-driven sense. However, there is a narrative moment in it. But what! From the "Letter" Guido Martynov gives a description of an event that predetermined the fate of European musical thinking, namely, an audience for which Pope John invited Guido of Aretinsky and during which a new invention was discussed - a method of "unfamiliar singing".

“The Equal-to-the-Apostles John, who now governs the Roman Church, having heard about the glory of our school and how the boys, by our antiphonaries, recognize hymns they had not heard before, being very surprised, after three nuncios called me to him.” As Martynov explains, this event is so significant that the fragment describing it is given six times (as we see, according to the number of steps in the hexachord). From Guido's letter it is reliably known that the pontiff gave the order to Guido's system of education to spread everywhere. Thus, the text of Guido (the tenor aria) and the text of the Milanese treatise (the soprano duet) are connected like cause and effect. According to Martynov, Pope John “warmed the snake on his chest”: instead of protecting religious foundations, he unwittingly contributed to the de-churchization of consciousness.

From Guido's letter it is reliably known that the pontiff gave the order to Guido's system of education to spread everywhere. Thus, the text of Guido (the tenor aria) and the text of the Milanese treatise (the soprano duet) are connected like cause and effect. According to Martynov, Pope John “warmed the snake on his chest”: instead of protecting religious foundations, he unwittingly contributed to the de-churchization of consciousness.

So, the literary sources are placed by Martynov in relation to conceptual intersections. The main object of intertextual connections between them is the concept of the number 6. The structural game in the libretto is tied to an analogy: the stairs of St. Bonaventure found an equivalent - this is the number of lines in the stanza of the hymn of St. John and the number of chants-segments of the hymn of St. John, as well as the scale staircase itself - "Guidon's hexachord" ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la. The concept of the number 6 permeates the entire structure of the opera from its large constructions to small chants. Thus, the central part of the opera "Exercises" is built, like the steps of a hexachord, in the form of a gigantic progression of six cycles, which, like patterns, have the same structure and textual content:

Thus, the central part of the opera "Exercises" is built, like the steps of a hexachord, in the form of a gigantic progression of six cycles, which, like patterns, have the same structure and textual content:

At each step this sequence of parts is repeated, but with different music, marking (with a certain degree of convention) the stages of musical evolution. The segments of the anthem of St. John:

The segments of the anthem of St. John:

Scheme of macro patterns

Initiation

Guido's aria

ambitus

melodies,

tenor solo

Duet Muses

Segments of hymn

St. John

Choral monody

Choral refrain,

soloists, instrumental tutti

UT Prima c (hcd) Ut queant laxis Ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la

RE Second cd Resonare fibris Ut-re-mi-fa-sol -la

MI Third cde Mira gestorum Ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la

FA Fourth cdef Famuli tuorum Ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la

SOL Quint cdefg Solve polluti Ut-re-mi-fa- sol-la

LA Sexta cdefga Labii reatum Ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la

The melodic material of the opera goes back to two sources, two canthus firmus - this is a hymn to St. John, taken as a whole or in the form of six segments, and Guidon's hexachord, which acts as a series and as a canthus subjected to segmentation. So the Exercises and Dances of Guido is not just a monothematic, but a cantus opera, just as there was a cantus mass or a cantus motet.

Each of the three texts has its own musical material. Text of St. Bonaventure is voiced in the forms of psalmody, Gregorian chant (like the hymn to St. John), organum and early polyphony (Introduction), in the genres of hymn, responsories and antiphons. Opera singing corresponds to the texts of Guido and the Milanese treatise: 6 Guido arias and 6 soprano duets, two Muses, they personify the composition (“Exercises”). But opera melos is nothing more than variations on cantuses: the hexachord is completely dissolved in the coloratura of Gregorian chants turned into decorative vignettes.

The instrumental finale (“Dances”) does not contain texts, but its musical material is entirely based on the hymn of St. John. It is noteworthy that the final 7th line (which Guido discarded) - "Saint John" - is present in the Finale, as if restored in its original place.

Guido's Exercises and Dances is an opera about the six stages of the history of music. The ascent of the soul up the stairs of St. Bonaventures correspond to six stages of the removal of music from the sacred source of singing. And also about the beginning and end of the opera - its brilliant, but brief history. It is sustained in the postmodern aesthetics, which loves double, triple coding so much. It has a minimalist basis, the bricolage method, work with style complexes. It has a triple subtext. “I attract Mozart and do something else with his own means,” Martynov said about his Requiem, but this has a direct bearing on Guido’s Exercises and Dances. As a result, the opera appears as a conceptual art object, multi-layered in its design. There are at least three layers: actual music, magic, conceptuality. As a result: opera, mystery, action.

Bonaventures correspond to six stages of the removal of music from the sacred source of singing. And also about the beginning and end of the opera - its brilliant, but brief history. It is sustained in the postmodern aesthetics, which loves double, triple coding so much. It has a minimalist basis, the bricolage method, work with style complexes. It has a triple subtext. “I attract Mozart and do something else with his own means,” Martynov said about his Requiem, but this has a direct bearing on Guido’s Exercises and Dances. As a result, the opera appears as a conceptual art object, multi-layered in its design. There are at least three layers: actual music, magic, conceptuality. As a result: opera, mystery, action.

Opera

The musical component, despite being conceptual, dominates. Music is self-sufficient. It corresponds to a layer, as we would say, of real opera music in its traditional sense. Moreover, this is not a stylization, not a simulacrum, but rather a sign, a hieroglyph of the opera. It presents the full paraphernalia of the opera genre: the obligatory leading tenor - the title character, arias, duets, choirs, the multi-layered texture of the orchestral-choral mass, the virtuoso style of bel canto. The harmonic language changes according to the era, but the tonal basis of harmony is preserved. Classical-romantic language, bel canto, virtuoso fiorious vocals - the components of the "new simplicity" - correspond to the ideas of the average operatic music lover about what opera should be like.

It presents the full paraphernalia of the opera genre: the obligatory leading tenor - the title character, arias, duets, choirs, the multi-layered texture of the orchestral-choral mass, the virtuoso style of bel canto. The harmonic language changes according to the era, but the tonal basis of harmony is preserved. Classical-romantic language, bel canto, virtuoso fiorious vocals - the components of the "new simplicity" - correspond to the ideas of the average operatic music lover about what opera should be like.

A sign of Martynov's style is the unhurried unfolding in the Introduction, where the listener is kept for a long time in the strict minimalist asceticism of Gregorianism in order to transfer our today's vain time into another - non-linear, medieval, metaphysical. Then the listener will perceive the subsequent opera beauties as the composer needs, because only in the stream of metaphysical time will they be heard in accordance with his concept. And only then does the “opera within the opera” begin - the long-awaited royal feast, which plunges (not without an element of absurdity) the opera listener into a state of blissful shock from the intoxicating bel cantos, from the enchanting fountains of operatic beauty. And what! Almost more exalted than Handel, almost more magical than Mozart himself, more captivating than Rossini, Bellini and all Italian opera. Bravo maestro! — the boxes, the stalls and the gallery should have shouted out in response to the generous gestures of the composer, when he lavishes high-class cantilenas arguing with operatic “hits”, leading us from style to style, from era to era. But only then, at every step, to turn them into precious fragments, into the ruins of an almost half-thousand-year-old myth that we call opera - a word that means the most ridiculous and sweetest thing that European culture has ever created. All this sinks into the sand, washed away by time as untrue, as just a beautiful mistake made by the hand of Guido d'Arezzo. And from the depths emerges the eternal prototype of Gregorianism, which returns everything to its full circle — into the bosom of liturgical singing.

And what! Almost more exalted than Handel, almost more magical than Mozart himself, more captivating than Rossini, Bellini and all Italian opera. Bravo maestro! — the boxes, the stalls and the gallery should have shouted out in response to the generous gestures of the composer, when he lavishes high-class cantilenas arguing with operatic “hits”, leading us from style to style, from era to era. But only then, at every step, to turn them into precious fragments, into the ruins of an almost half-thousand-year-old myth that we call opera - a word that means the most ridiculous and sweetest thing that European culture has ever created. All this sinks into the sand, washed away by time as untrue, as just a beautiful mistake made by the hand of Guido d'Arezzo. And from the depths emerges the eternal prototype of Gregorianism, which returns everything to its full circle — into the bosom of liturgical singing.

Conceptuality.

Simplicity, however, is apparent. This is an absolutely elitist piece. Everything in it is subordinated to an extra-plot, but consistently drawn line of conceptual dramaturgy. Here, the “intrigue” is the history of singing in the Western European tradition, which is increasingly moving away from the sacred source, that is, from the Gregorian monody, and has gone through Romanesque polyphony to secular art - opera (baroque, classicism, romanticism). The style, by design, evolves, but the opera is still minimalist, and this is the unifying core, so there is no eclecticism. The repetitive components of the thematic also seem to be akin to the operatic leitmotif system. However, they are categorically not it: the repetition of structural components is due to the concept of number, minimalist repetitiveness and the rituality associated with them.

Everything in it is subordinated to an extra-plot, but consistently drawn line of conceptual dramaturgy. Here, the “intrigue” is the history of singing in the Western European tradition, which is increasingly moving away from the sacred source, that is, from the Gregorian monody, and has gone through Romanesque polyphony to secular art - opera (baroque, classicism, romanticism). The style, by design, evolves, but the opera is still minimalist, and this is the unifying core, so there is no eclecticism. The repetitive components of the thematic also seem to be akin to the operatic leitmotif system. However, they are categorically not it: the repetition of structural components is due to the concept of number, minimalist repetitiveness and the rituality associated with them.

Mystery

Mystery is the result of combining the symbolism of number and ritual. A strict order of repetitions controlled by numbers, Latin in the role of a "transrational language", incomprehensible, but acting magically (according to Khlebnikov) - all these are components of mystery. The tension of the dizzying game at the same time at the level of the text, the musical structure, the linguistic closeness of Latin give rise to the atmosphere of a magical performance, powerful in terms of impact. The earliest of the two versions of the finale (1997). The ascent achieves the longed-for goal, and at the top the singing "straightens" in unison, into psalmody. The opera turns into a liturgy. This is an early version of the finale. According to her, the historical synopsis of a one-act opus: liturgy - opera - liturgy. Here, the parallels with "Parsifal" or "Kitezh" are not accidental. Perhaps Guido's Exercises and Dances is a modern attempt to correct Guido's "mistake" and return music from the opera house to the temple. This initial concept for the ending was misunderstood by the public and remained at the sketch stage.

The tension of the dizzying game at the same time at the level of the text, the musical structure, the linguistic closeness of Latin give rise to the atmosphere of a magical performance, powerful in terms of impact. The earliest of the two versions of the finale (1997). The ascent achieves the longed-for goal, and at the top the singing "straightens" in unison, into psalmody. The opera turns into a liturgy. This is an early version of the finale. According to her, the historical synopsis of a one-act opus: liturgy - opera - liturgy. Here, the parallels with "Parsifal" or "Kitezh" are not accidental. Perhaps Guido's Exercises and Dances is a modern attempt to correct Guido's "mistake" and return music from the opera house to the temple. This initial concept for the ending was misunderstood by the public and remained at the sketch stage.

Action

But the second version (2006) presents a different concept of the finale. Ascent-descent reaches the last stage, and then there is a sudden scrapping of the whole "game": the invasion of an alien beginning - music in the style of hard rock ("Dances"). Rock - in the meaning of the 60s-70s of the twentieth century, with its breakthroughs, protests, zeal and passion, with the "desire to shout" to a blurred ear and a blurred consciousness. The contrast with opera is existential. Sharpness and rigidity, again, is not a traditional method of operatic dramaturgy. Rock is a direct, real challenge to the establishment, academic music, opera gloss, the philharmonic, the concert situation in general. Challenge to the culture of modern times. But he has his own mission: the fatal part revives the anthem of St. John, but in a characteristic rock - brutal - articulation. The effect is comparable to the feeling that a group of terrorists burst into the hall. In any case, the Opus posth ensemble, headed by Tatyana Grindenko, proved to be musical terrorists here. Except Grindenko (who in the 70s participated in Martynov's rock group) with her ensemble "Opus posth", no one will play like that! Rock with its street vernacular, perhaps alone is able to truly express reality in its ontological tangibility.

Rock - in the meaning of the 60s-70s of the twentieth century, with its breakthroughs, protests, zeal and passion, with the "desire to shout" to a blurred ear and a blurred consciousness. The contrast with opera is existential. Sharpness and rigidity, again, is not a traditional method of operatic dramaturgy. Rock is a direct, real challenge to the establishment, academic music, opera gloss, the philharmonic, the concert situation in general. Challenge to the culture of modern times. But he has his own mission: the fatal part revives the anthem of St. John, but in a characteristic rock - brutal - articulation. The effect is comparable to the feeling that a group of terrorists burst into the hall. In any case, the Opus posth ensemble, headed by Tatyana Grindenko, proved to be musical terrorists here. Except Grindenko (who in the 70s participated in Martynov's rock group) with her ensemble "Opus posth", no one will play like that! Rock with its street vernacular, perhaps alone is able to truly express reality in its ontological tangibility. It is a paradox, but the high turns out to be achievable just thanks to the decrease. The reduction clears the meaning of the words back to their original meaning. And if the vocal graces of the operatic bel canto turned the Gregorian jubilee into beautiful vignettes, then in the earnest energy of rock articulation, the Gregorian chants acquire a burning true meaning. The opera-mystery turned into an action. There was a violation of the boundaries of art and falling into reality. A truly existential gesture! Here it is appropriate to quote the words of V. Martynov about the difference between artistic expression and a real act:

It is a paradox, but the high turns out to be achievable just thanks to the decrease. The reduction clears the meaning of the words back to their original meaning. And if the vocal graces of the operatic bel canto turned the Gregorian jubilee into beautiful vignettes, then in the earnest energy of rock articulation, the Gregorian chants acquire a burning true meaning. The opera-mystery turned into an action. There was a violation of the boundaries of art and falling into reality. A truly existential gesture! Here it is appropriate to quote the words of V. Martynov about the difference between artistic expression and a real act:

“If we compare bel canto with any natural folklore voice or voice in Eastern cultures, we will see that bel canto certainly sounds very beautiful, but it does not have that energy. Beauty and roundness is achieved due to the loss of primary energy. People who are engaged in any form of authenticity - early baroque or renaissance, old Russian singing, from different angles come to the energy, which is almost lost in classical performance. Her beauty is a substitute, an image of this energy. What is my complaint about the composing art of the 19th century - that this is an artistic art that depicts, and I strive for an art that does not represent, but is what it is. Let's say Scriabin wrote "The Poem of Ecstasy", where... a person experiences a feeling of depicted ecstasy, and the shaman simply strikes a tambourine and falls into this ecstasy. And the beat of the tambourine leads to a real state of ecstasy. The composer deals with unreal things, and the shaman deals with real things. And this is the essence of authenticity. Any person involved in authenticity is already closer to the primary energy impulse than any of the best-equipped and most sophisticated composers... The same is true in performance. When Montserrat Caballe sang along with such an absolutely grandiose energy generator as Fredi Mercury is, no synthesis happened. He beat her energetically. The results are false. It's the same with Pavarotti when he tried to sing with rock singers.

Her beauty is a substitute, an image of this energy. What is my complaint about the composing art of the 19th century - that this is an artistic art that depicts, and I strive for an art that does not represent, but is what it is. Let's say Scriabin wrote "The Poem of Ecstasy", where... a person experiences a feeling of depicted ecstasy, and the shaman simply strikes a tambourine and falls into this ecstasy. And the beat of the tambourine leads to a real state of ecstasy. The composer deals with unreal things, and the shaman deals with real things. And this is the essence of authenticity. Any person involved in authenticity is already closer to the primary energy impulse than any of the best-equipped and most sophisticated composers... The same is true in performance. When Montserrat Caballe sang along with such an absolutely grandiose energy generator as Fredi Mercury is, no synthesis happened. He beat her energetically. The results are false. It's the same with Pavarotti when he tried to sing with rock singers. There he got lost, if not vocally, then energetically. Any normal rocker will beat an academic musician."

There he got lost, if not vocally, then energetically. Any normal rocker will beat an academic musician."

At the end, the anthem of St. John sounds in its original form on the solo celesta. The timbre of the instrument (“heavenly”) is symbolic: quiet music, quiet simplicity. The opera ends not as a meeting of the soul with God, but rather as a questioning about it. And waiting for an answer in a long silence. The second version of the final was accepted with a bang. Mankind understands the prayer of a simple sinner more than the enlightenment of an ascetic. The result is a standing ovation (2006).

Opera is difficult to perform. And to adequately embody on stage is a tough nut to crack for a future director, whose intellectual aristocracy would be a match for what Martynov possesses in order to maintain a high style and not step into the limits of irony or kitsch. It is clear that this should be non-traditional opera and theatrical dramaturgy, because the characters are not characters, but cultural flows, historical styles. There must be a very special space built. The first version was written for performance in the ancient Romanesque basilica of the Lokkum Monastery, where the Sacro Art 19 festival was held.97". The opera was performed in concert and did not need to be staged. The situation is better than ever. The vaults, which are 800 years old and which remember and keep a lot to this day, fell to be the real space of what is said in the opera. What kind of stage decision awaits the second version - a question for the future!

There must be a very special space built. The first version was written for performance in the ancient Romanesque basilica of the Lokkum Monastery, where the Sacro Art 19 festival was held.97". The opera was performed in concert and did not need to be staged. The situation is better than ever. The vaults, which are 800 years old and which remember and keep a lot to this day, fell to be the real space of what is said in the opera. What kind of stage decision awaits the second version - a question for the future!

When Martynov spoke about the impossibility of writing an opera today, and they objected to him: “But you wrote it,” the composer replied: “This is an opera about the end of an opera.” There are many statements about the end of something from modern culture in the twentieth century. For the same Martynov - "the end of the time of composers" and "the end of Russian literature", Peter Greenway - "the end of cinema", there is also the "end of the theater", the end of philosophy, the end of the meta-narrative, the death of the Author. In Valentin Silvestrov’s statement “the post-lude state of culture” one can read the end of culture… But at the same time, Greenway is making a new movie, Jerzy Grotowski and Anatoly Vasiliev created a mystery theater, Silvestrov writes “post-ludes”, and Martynov writes “post-opus music”. Including post-opera.

In Valentin Silvestrov’s statement “the post-lude state of culture” one can read the end of culture… But at the same time, Greenway is making a new movie, Jerzy Grotowski and Anatoly Vasiliev created a mystery theater, Silvestrov writes “post-ludes”, and Martynov writes “post-opus music”. Including post-opera.

Let me quote Martynov's words about the performance Mozart and Salieri / Requiem by Anatoly Vasiliev. They can be attributed to the opera Exercises and Dances of Guido: “The whole performance is a farewell to Western European culture. <...> The point is that a certain paradigm of the existence of music is coming to an end. We see that the light does not converge like a wedge on composer's music. Many of the most brilliant results have been achieved outside of composers, not to mention all the great cultures of antiquity and the traditional cultures of modern times. All systems of liturgical singing, folklore do not know the figure of the composer, just like jazz and rock.