How to dance egyptian style

The Different Dances of Egypt

By Sahra K. | 3 Comments | Posted on January 16th, 2014 | Dance Style

The Different Dances of Egypt

In our last post The Different Regions of Egypt we discussed the regions of Egypt as I’ve defined them for our dance ethnology purposes. These regions are defined based on the views of the people themselves. Each of these regions also have their own very distinctive dances. Below I have listed a very short summary of the dances of each of these regions.

Nubian

The Regional Governorate Troupe of Nubia performing at Abu Simbel. Photo by Hagy Mahmoud.

There are actually a wide variety of Nubian dances; previously the Nubian peoples were of different groups in many different villages scattered along the length of the Nile in both southern Egypt and the Sudan. Some of the dances are from the Kensi people, some from Fadiki and some from groups who identify with Arab (Khaliji) immigrants.

The basic step most groups have in common is the right foot in front stepping down on the beat, the ball of the left foot in back stepping on the “and. ” The arms move symmetrically together either forward and back or side and towards center. Men lean forward from the hips, women stand straight. Neither men nor women use hip-work, both can tilt their shoulders, women can also do upper torso lifts or drops. In this region you can also find Arageed, Soki, and Nagrashod dance styles.

Sa’idi

For dancers throughout the world, the dance of the Sa’idi region is probably the most well known “folklore” dance of Egypt.The most popular public dance of the Sa’id is Raqs Assaya (stick dance), whether the Assaya was twirled or held.

The basic footwork is a step to the side (count 1), then (on count 2) the other foot kicks across in front of the standing leg. This movement can just be done out of happiness, or it can be “performed” by non-professionals in celebration of an event. It is the main step for the representation of Sa’idi dance throughout Egypt and the world.

Also popular in the Sa’id is the Tahtib, a martial arts style contest that tests the cleverness and skill of two men fighting with Asaya. In stage performance the Tahtib can be referred to with dance. In this region you can also find the Kafafa and a variety in-home dance styles.

In stage performance the Tahtib can be referred to with dance. In this region you can also find the Kafafa and a variety in-home dance styles.

Cairo

Home-style female dance is the movement base for Raqs Baladi and Egyptian Orientale. When millions of dancers worldwide refer to Egyptian style Orientale dance, they are referring to Cairo. Even within Egypt, other regions are aware of the steps and posture of the Cairo Orientale dancer, and probably can replicate it if not too shy.

Cairo is also home to both National Companies, Firqat Reda (started by Reda and Fahmy families with Mahmoud Reda director/choreographer) and Al Firqah Al Kowmeyya Al Fannon Al Shaabeya (the National Troupe of Artists of Folklore) where dances from Egypt’s regions are brought to the theater stage. Cairo is also the main recording center of the Middle East, and their Orientale Film Stars and Night Club dancers are legendary. On these stages you can also find the Baladi Awad and Tet Baladi and a variety of neighborhood, Shaabi, dance styles.

Delta

Fellaha Women 1860’s-1920’s.Photo referenced from the New York Public Library.

Egypt’s Delta is home to a wide diversity of populations and their dance styles.

Even though the word “Fellahin” denotes a specific type of farmer no matter where in Egypt he is farming, in a dance program “Fellahin” would refer to the Delta farmers. Inside these countryside homes, and within urban homes as well, there is a wide variety of movement, some of which is not represented on stage by the touring government troupes, including a twisting hip shimmy and a front pelvic drop.

Alexandria had it’s own signature Orientale dance style – with more bounce and often sticking the thumbs out as a reference to dancing with knives.

The Delta also has at least two famous Ghawazee groups; Sumbati Ghawazee (famous for their “athletic style” including shamadan with splits and floorwork, and balancing a chair in their teeth) and the Ghawazee of Tanta (Tanta is more famous for their musicians and the fine nye that are made there. )

)

Suez Canal

Originally this area was desert terrain with bedouin inhabitants. With an international presence in the building and maintenance of the Suez Canal an interesting dance form developed; an international fusion of tunes played on a Bedouin instrument (Simsimeya), European style of hand-played spoons, and a variety of objects played as drums. The dance form is singular in Egypt; the bouncy dance, often danced in “turn-out” is unlike any other dance form in the country.

Sinai

A Bedouin Woman from the Sinai.

Dances take place during celebrations, such as marriages. This includes the dance called “Daheya” – the men singing and clapping in a line can be done at any time, but the dancing can only be done during cultural ritual. The Daheya is done by the extended family itself, not by local professionals.

The Sinai dances are represented by the Regional governorate troupe for Folk Art in Ismailiya on the Suez Canal. Both National Dance Companies have a “Daheya” on their repertoire, but they look different.

Siwa

Siwa people are of Amazigh (Berber) heritage and culture. It is not easy to view the music and dance here due to Siwa’s very private traditional ways.

As was observed and documented by Tamalyn Dallal: The men’s arms are held straight out to the sides, a hip sash is tied very low on the backside. The basic step is made to be viewed from the back, the backside makes vertical circles (side, up, side, down). A additional hip movement is a strong down accent on one hip, standing with flat feet and slightly bent knee.

Mahmoud Reda, in 1965 observed the men in a different dance, outdoors and without the hip-sash they bent forward in single file, their arms relaxed at their sides except when clapping, their steps were bouncy and fast paced. The women did not allow themselves to be viewed dancing.

Siwa dance on stage, by both National Companies, hold the arms bent in front of the body, hands relaxed, leaning forward from the hips, with no hip-sash the hips make vertical circles with a little jump sideways. I have never seen Siwa dance represented in Cairo Orientale dance show.

I have never seen Siwa dance represented in Cairo Orientale dance show.

Western Desert

Predominantly Awlad Ali tribe, of Arab origin, the bedouin of the Western Desert were once nomadic, and although now predominantly settled, still prefer to live in their tents. This is the group that are famous, to people outside of themselves, for the Haggalah dance.

According to ethnographies on the Awlad Ali and the Haggalah dance; during the time of plenty of water in the spring, the extended family/tribe comes together and is therefore the time of marriages.

A Bedouin woman (from one to three women, plus a male chaperone) comes out of the desert and first dances in the tents with the women (of which we have no observation since these anthropologists were men), then the Haggalah woman/women goes outside and dances the Haggalah dance with the men. The people of the tribe could not answer the anthropologist’s questions as to who she was or how she knows when to come.

Eastern Desert

A girl from the Beja Tribe of the Eastern Desert. Photo from Geeska Afrika

I have been trying to study these people for 20 years. In all the Beja dances I have seen, the men carry a sword, the women do not. One of the Beja dances includes men and women bending their heads backwards so that the face is parallel to the sky, then the torso undulates similarly to what western Belly dancers call a “camel”. The men do this while holding a sword outright, but can also balance the sword flat on his upturned forehead.

Local professional female singers also do the “pigeon dance” with the face tilted up.

There are also men’s martial arts type contests with the sword, music on the Tambour (like the Suez Simsimiyya) is played. The sword is swung to make your opponent flinch.

Read MoreThe Different Regions of Egypt

Pan-Egyptian Movement

Egyptian Baladi and Shaabi dance styles.

Traditional dance in Egypt.

Traditional dance in Egypt.Last Updated on January 24, 2022

What Does Baladi Mean?

Baladi (also spelt beledi or balady), means my country in Arabic. This is a term used by villagers who emigrated from rural communities into Egyptian cities.

They referred to their culture and music as the music from their home, the villages in the countryside. Raqs Baladi is usually danced socially, during celebrations and gatherings. Nowadays it is also performed on stage.

Baladi Music

Traditionally, Baladi music has a framework divided into sections, during which musicians and dancers improvise. Generally speaking, these are the main sections:

- Taqsim –melody without percussions, played originally on oud, more recently on accordion, sax or keyboard. The dancer dances on the spot with small and contained movements. Usually the dancer sways to long notes (this type of music is called awwady) and shimmies to tremolando sound.

- Me-Attaa – the rhythm, played on tabla, is introduced gradually with a question and answer between the instrumentalist and the drummer.

The dancer dances a bit faster but still conservatively. The rhythm gets faster gradually.

The dancer dances a bit faster but still conservatively. The rhythm gets faster gradually. - Maqsoum – uptempo rhythm.

- Tet – nostalgic rhythm played on mizmar.

- Another Me-Attaa, this time with fallahi rhythm.

- The music slows down gradually back to the initial awwady taqasim, until it stops.

Shaabi and Baladi Dance movements

In Baladi style, the dance movements are earthy and grounded, with simple step patterns (mostly on flat feet).

The arms are generally held by the side with elbows slightly bent, rather than flowing around.

Shaabi and Baladi Costumes

Dancers performing Baladi style wear a Galabeya or Baladi dress (a full dress not baring the midriff). The most traditional type, preferred for folkloric performances, is loose and simple, and the dancer wears a hip scarf around her hips.

The Galabeya used for cabaret performances is fitted, made with stretchy and shiny material, heavily decorated with fringes and beads.

Introduction and Origins of Shaabi

Shaabi, also spelt sha’abi, is a style of music and dance that has ancient roots in the folkloric traditions of rural Egypt, but which developed in the urban working-class neighborhoods of Egypt.

Shaabi (meaning of the people) is the music of the working class in Egypt and the lyrics of shaabi songs are usually about politics, personal life or love (often quite explicit).

Sometimes lyrics can even be total nonsense, such as the colour of grapes or loosing glasses; in one instance a Viagra type company used it for an advert and nowadays the emphasis is on DJ mixes.

Shaabi is often danced in Egyptian nightclubs like our western pop music is danced socially in the west.

Music and Famous Shaabi and Baladi Artists

Shaabi is played using traditional instruments well as modern electronic synthesizers and its tone is quite playful. The urban variety of Shaabi became largely popular in the 70s with Ahmed Adawiya (also transliterated as Adawiyah, Adeweia, or Adeweya).

The urban variety of Shaabi became largely popular in the 70s with Ahmed Adawiya (also transliterated as Adawiyah, Adeweia, or Adeweya).

Ahmed Adawiya started his career as a cafe waiter but soon became a popular Shaabi singer. In his songs he uses the language of the streets of Cairo and, like may Shaabi singers, he specializes in vocal improvisation.

Other popular shaabi singers include Hakim, Shaban Abdul Raheem, Sami Ali, Sahar Hamdy, Magdy Talaat and Magdy Shabin.

Shaabi and Baladi Dance styles

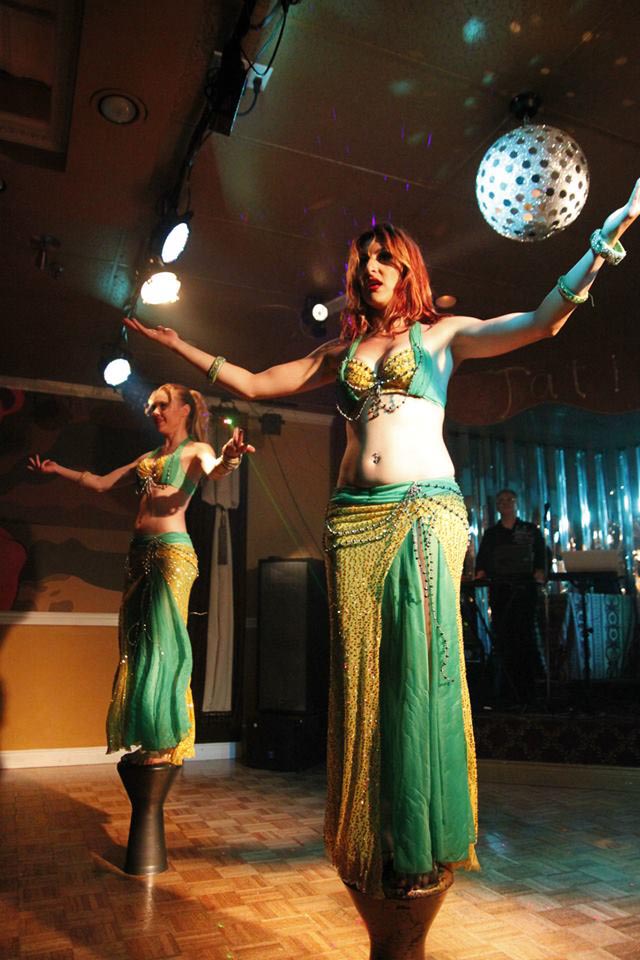

Dance-wise, the Egyptian Shaabi style is playful and flirtatious, a bit ‘cheeky’, with a strong folkloric influence.

The movements are earthier than in raqs sharki, without so many spins nor big traveling steps; steps are mostly on flat feet rather than on tiptoes. Shaabi style is not elegant but funky.

The movements are relatively simple but full of feeling. A dancer who can be used as an example of shaaby style is Fifi Abdo.

Her style was mainly baladi and oriental but the ‘fun/acting’ aspects of Fifi’s performance had elements of Shaabi.

The following two tabs change content below.

- Bio

- Latest Posts

Dr Valeria Lo Iacono is a belly dancer and a dance researcher with a PhD in dance and heritage. Valeria also teaches and performs as a belly dance but also enjoys learning ballet, jazz dance and other dance genres.

Sharing is caring!

187 shares

- Facebook176

- egypt

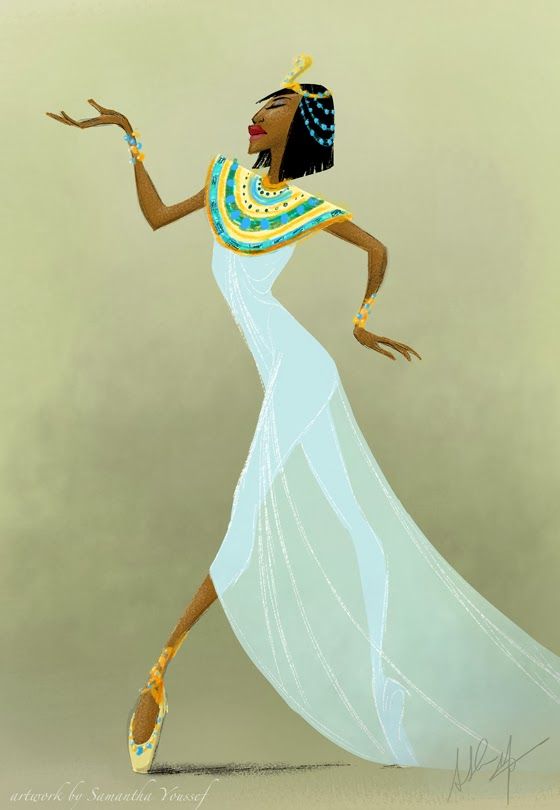

Arena. Ballet Egyptian Nights (Cleopatra)

Ballet to music by Anton Arensky in one act. Screenwriter and choreographer M. Fokin, artist O. Allegri (sets), O. Zandin (costumes), conductor M. Keller.

The premiere took place on March 8, 1908 at the Mariinsky Theatre.

Characters:

- Cleopatra, Egyptian Queen

- Mark Antony, Roman general

- Verenice, Egyptian, temple servant

- Amun, young Egyptian

- Priest

- Slave of Cleopatra

- Arsinoe, slave of Cleopatra

- Egyptian dancers, temple attendants, Jewish dancers, slaves, Roman soldiers, Ethiopian captives

The action takes place in Egypt in the 1st century BC.

History of creation

Arensky wrote his only ballet in 1900 by order of the Directorate of Imperial Theaters. By this time he was already quite an authoritative composer, the author of two operas, many symphonic and chamber works. The ballet was to be staged in Peterhof in connection with the visit of the Persian Shah to Russia. The novella of the French poet and romantic writer Theophile Gauthier (1811-1872) "The Night of Cleopatra" served as a literary source for the script. Apparently, the composer worked on the script together with the choreographer Lev Ivanov (1834-1901). In the unpublished memoirs of a contemporary, it is mentioned that the premiere of the ballet entitled "Nights in Egypt" with the participation of Petipa's daughter Maria and the famous Matilda Kshesinskaya took place on March 3, 1901. However, there is no documentary evidence of this. Many studies on ballet theater indicate that the ballet was being prepared for production by L. Ivanov, but never saw the light of day.

In the 1907/08 season, M. Fokin (1880-1942), a talented young choreographer who had already gained a reputation as a bold innovator, decided to stage Arensky's ballet using the old script. The premiere took place on 8 (21) March 1908 years. It is curious that literally all the critics who wrote about the premiere of "Egyptian Nights" referred to Pushkin, not suspecting that Gauthier's short story was taken as the basis for the plot (Pushkin used the same motif, but developed it in a completely different way).

The performance, shown for charity, was performed in prefabricated scenery and costumes, and only later, in 1909, did scenery and costumes made especially for him appear.

At the same time, Diaghilev took Egyptian Nights to Paris under the name Cleopatra. The ballet was staged in an expanded form: the performance included fragments from the music of other composers. The peculiarity of Fokine's choreography was that he stylized the poses depicted on Egyptian frescoes. All this was completely unusual for the ballet scene. The role of Cleopatra was entrusted to Ida Rubinstein, Verenik, who in the Parisian version bore the name Taor, danced Anna Pavlova, Amuna - Fokine himself.

All this was completely unusual for the ballet scene. The role of Cleopatra was entrusted to Ida Rubinstein, Verenik, who in the Parisian version bore the name Taor, danced Anna Pavlova, Amuna - Fokine himself.

“Egyptian nights,” the critic wrote, “is a violation of all the traditions of the good old days, it is a “revaluation of values”, a denial of eversion of the legs, classical technique, a violation of the “canon”. This is evolution, a new word, an excursion into the field of archeological iconography and ethnographic dance, which is most interesting on assignment.”

Alexandre Benois in his article "Russian Performances in Paris" wrote about the resounding success of "Cleopatra", about how the talents of Diaghilev's troupe fascinated the audience, despite the complete implausibility of the script: "There could be nothing like what was played out. The Egyptian "landlords" never cared for the maids of the temple and did not shoot arrows with love notes at the queens, the spouses of the pharaoh never indulged in love caresses on the porch of the temple, they never poisoned their momentary favorites in front of any rabble who came to honor them . .. "

.. "

Nevertheless, the audience was delighted, the performance was interrupted by applause, additional performances were announced. In subsequent years, the ballet was repeatedly resumed on Soviet stages.

Music

Ballet music is distinguished by the clarity of melody, emotionality, brightness and variety of orchestral colors. The composer used authentic oriental melodies, creating a score in a parlor-styled oriental style.

L. Mikheeva

Story

Bank of the Nile. Berenice, a servant of the temple, along with other girls, carries vessels with sacred water to the temple. Berenice is waiting for her beloved Amun. They rush towards each other. The priest, seeing their happiness, joins their hands, blessing the marriage union.

A procession is moving towards the temple. This is Queen Cleopatra, surrounded by slaves and dancers. Lazily parting the silk curtains of a closed palanquin, she slowly leaves and heads for the temple. Amun is struck by the beauty of the queen and tries to keep up with her. Guards block his way.

Amun is struck by the beauty of the queen and tries to keep up with her. Guards block his way.

Cleopatra sits down on the bed prepared for her. Slaves and slaves entertain her with dances. To draw the attention of the queen, Amun takes a bow and strikes a tree next to Cleopatra with an arrow. The guard grabs Amun, but Cleopatra orders the young man to pass. Slave Arsinoe reads to the queen a papyrus attached to an arrow. Amun passionately tells Cleopatra about his love. The queen warns that he will pay for love with his life. A moment - Amun agrees.

Berenice runs in, she rushes to Amun and begs to go with her. He belongs to her - after all, their union was consecrated by a priest. Cleopatra looks menacingly at the pathetic servant, and, unable to withstand the wrath of the queen, Berenice falls to the ground. Pity for Berenice and passion for Cleopatra struggle in Amun's soul. Passion wins, and, depressed, the girl leaves.

Amun at the queen's feet. Slaves decorate their bed with flowers and raise a silk curtain. While the love date lasts, the slaves dance, ringing bells and striking tambourines. Berenice in desperation dances the sacred dance with the snake. There comes a moment of reckoning, the priest brings a bowl of poisoned wine. Amun, blinded by the recent bliss, drinks the wine in one gulp and, in the last hope, stretches out his hands to Cleopatra. But all in vain: Amun falls lifeless, and Cleopatra orders to remove his corpse.

While the love date lasts, the slaves dance, ringing bells and striking tambourines. Berenice in desperation dances the sacred dance with the snake. There comes a moment of reckoning, the priest brings a bowl of poisoned wine. Amun, blinded by the recent bliss, drinks the wine in one gulp and, in the last hope, stretches out his hands to Cleopatra. But all in vain: Amun falls lifeless, and Cleopatra orders to remove his corpse.

Another meeting awaits the queen. The Roman commander Mark Antony, the winner of the Ethiopian king, appears on a luxurious chariot. Seeing the Egyptian queen, he gives her the Ethiopian crown and many captured captive slaves. Cleopatra crowns Antony with a laurel wreath. Embracing the queen, the warrior leads her to the Nile, where a galley is already waiting for them.

Unfortunate Berenice comes to the deserted square. Not far from the temple, she finds the body of Amun and, sobbing, falls on him. A priest comes out of the temple and consoles the girl: he changed the poison in the bowl, and Amun remained alive. The young man wakes up from a long "sleep" and embraces Berenice.

The young man wakes up from a long "sleep" and embraces Berenice.

* * *

Anton Arensky (1861-1906) wrote the music for the ballet "Nights in Egypt" in 1900. It was assumed that the ballet would be choreographed by choreographer Lev Ivanov for an outdoor performance (according to other sources, in the Hermitage Theatre). Even the costumes were made, but for unknown reasons the production did not take place. Ballet music does not belong to the best pages of the composer's work, known for his symphonic works, composed under the clear influence of his teacher Tchaikovsky. However, in ballet this influence is felt to a minimal extent. The melodic and dance music abounds with marches, grand entrances, exotic dances and even waltzes. After the premiere, critics noted: "Arensky's music is a conscientious work, but in no way outstanding."

The author of the original ballet script is unknown. The plot is borrowed from the short story by Theophile Gauthier "Night of Cleopatra". This melodramatic narrative only mentions a girl who is in love with a hero who does not reciprocate her feelings. Young Myamun has long been blinded by passion for the queen. Cleopatra in the novel languishes from the monotony of court life. The ardent love of the young man almost conquers the queen, and only the sound of the approaching Mark Antony's trumpets makes the queen carry out the promised poisoning. From the eyes of Cleopatra rolls a hot tear, the only one in her life. In accordance with unwritten ballet traditions, the end of the performance could not be sad, and the hero remained alive. Fokine changed a number of details of the script, giving the ballet a new name Egyptian Nights (perhaps not without the influence of Pushkin's unfinished work of the same name).

This melodramatic narrative only mentions a girl who is in love with a hero who does not reciprocate her feelings. Young Myamun has long been blinded by passion for the queen. Cleopatra in the novel languishes from the monotony of court life. The ardent love of the young man almost conquers the queen, and only the sound of the approaching Mark Antony's trumpets makes the queen carry out the promised poisoning. From the eyes of Cleopatra rolls a hot tear, the only one in her life. In accordance with unwritten ballet traditions, the end of the performance could not be sad, and the hero remained alive. Fokine changed a number of details of the script, giving the ballet a new name Egyptian Nights (perhaps not without the influence of Pushkin's unfinished work of the same name).

Fokine's ballet was originally intended for a charity performance, so the above scenery and costumes appeared only for the official premiere on February 19, 1909. The choreographer was carried away by ancient Egypt. “In my free time, I ran into the Hermitage, to the wonderful Egyptian department, which I had thoroughly studied a long time ago. I surrounded myself with books on Egypt. In a word, I was in love with this special ancient world.” A natural, albeit controversial, solution was to compose dances, and even pantomime, in the "Egyptian style". Profile poses, angular lines, flat hands were copied from museum bas-reliefs. Some critics were enthusiastic about this innovation. "Egyptian nights" is a violation of all the traditions of the good old days. “This is a “revaluation of values”, a denial of eversion of the legs, classical technique, a violation of the “canon”. This is evolution, a new word, an excursion into the field of archeological iconography and ethnographic dance, which is most interesting on assignment” (V. Svetlov). Others were ironic: “Fokine passes off this nightmare of two-dimensional plasticity based on bas-relief samples as a semblance of Egyptian dance, while mixing the systems of painting and sculptural technique with the art of dance, as it should have been in historical reality” (A.

“In my free time, I ran into the Hermitage, to the wonderful Egyptian department, which I had thoroughly studied a long time ago. I surrounded myself with books on Egypt. In a word, I was in love with this special ancient world.” A natural, albeit controversial, solution was to compose dances, and even pantomime, in the "Egyptian style". Profile poses, angular lines, flat hands were copied from museum bas-reliefs. Some critics were enthusiastic about this innovation. "Egyptian nights" is a violation of all the traditions of the good old days. “This is a “revaluation of values”, a denial of eversion of the legs, classical technique, a violation of the “canon”. This is evolution, a new word, an excursion into the field of archeological iconography and ethnographic dance, which is most interesting on assignment” (V. Svetlov). Others were ironic: “Fokine passes off this nightmare of two-dimensional plasticity based on bas-relief samples as a semblance of Egyptian dance, while mixing the systems of painting and sculptural technique with the art of dance, as it should have been in historical reality” (A. Volynsky). One would think that this fierce defender of the old "classical" ballet knew how to dance in the era of the pharaohs! Not without reason, they also complained that Fokine's vocabulary of dance was not without the influence of Isadora Duncan's "free dance". However, for the ballet retrogrades in the ballet, there remained the entry of Anthony on a chariot, quite in the tradition of old performances, and the inevitable pantomime monologues. On the whole, the value of the St. Petersburg performance was not in archaeological “authenticity”, but in the modern worldview, paradoxically expressed, like other forms of art, through the perception of distant eras.

Volynsky). One would think that this fierce defender of the old "classical" ballet knew how to dance in the era of the pharaohs! Not without reason, they also complained that Fokine's vocabulary of dance was not without the influence of Isadora Duncan's "free dance". However, for the ballet retrogrades in the ballet, there remained the entry of Anthony on a chariot, quite in the tradition of old performances, and the inevitable pantomime monologues. On the whole, the value of the St. Petersburg performance was not in archaeological “authenticity”, but in the modern worldview, paradoxically expressed, like other forms of art, through the perception of distant eras.

The main parts were performed by Anna Pavlova (Berenice) and Mikhail Fokin (Amun). For the role of non-dancing Cleopatra, the choreographer chose a student of drama courses, Elizaveta Time, wanting to distinguish her non-ballet plastique from other characters. In front of the bored queen with a veil, her favorite slaves danced - Arsinoe (Olga Preobrazhenskaya) and the Brown Slave (Vaclav Nijinsky). Tamara Karsavina was the soloist in the Jewish dance against the background of the bed of love. This superb cast changed little when Sergei Diaghilev decided to include Fokine's new ballet in the Russian Season 19 in Paris.09 years.

Tamara Karsavina was the soloist in the Jewish dance against the background of the bed of love. This superb cast changed little when Sergei Diaghilev decided to include Fokine's new ballet in the Russian Season 19 in Paris.09 years.

However, much had to be changed. The ballet began to be called Cleopatra, Berenice began to bear the name Taor, Anthony disappeared along with the chariot, but the finale was returned to the original Gauthier - Amun must pay with death for love. The main thing that confused Diaghilev was Arensky's dim music. Numerous replacements have turned the performance's score into a musical patchwork of Russian authors. Sergei Taneyev's overture to "Oresteia" replaced the previous overture, the dance of the slaves at the exit of Cleopatra was performed to the music from "Mlada" by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, the dance with the veil went to the music of Mikhail Glinka. The orgy before the bed of love included an orgy from Alexander Glazunov's The Four Seasons, which enjoyed particular success in the performances of Vera Fokina, Olga Fedorova and the corps de ballet. The finale of the orgy was a dance to the music of Modest Mussorgsky's Persian dances, and the new finale was hastily composed by the conductor of the performance, Nikolai Cherepnin.

The finale of the orgy was a dance to the music of Modest Mussorgsky's Persian dances, and the new finale was hastily composed by the conductor of the performance, Nikolai Cherepnin.

The opening of the tour was the performance of the role of Cleopatra by Ida Rubinstein. The appearance of this amazing woman is now familiar to every cultured person from the famous portrait of Valentin Serov. Tall, thin, angular and unusually beautiful, the artist did not have a special choreographic education. Fokine's private lessons allowed this outstanding artist not only to create unforgettable images of Cleopatra and Zobeida in Diaghilev's Scheherazade, but later to lead her own troupe. Alexandre Benois testified: “To the marvelous, but also terrible, seductive, but also formidable music from Mlada, the notorious undressing of the queen took place. Slowly, with a complex court ritual, numerous covers were unwound one after another, and the body of the omnipotent beauty was exposed, the flexible thin figure who remained only in that wonderful translucent outfit that Bakst invented for her. But that was not a "pretty actress in frank dezability", but a real enchantress, carrying death with her. "Cleopatra" gave the best fees in Paris. They began to give her as a bait after the opera The Maid of Pskov with Chaliapin himself. A constellation of talented artists, unusual choreography in the "Egyptian style" and the very theme of destructive beauty, so in tune with fashionable trends in literature and painting, ensured "Cleopatra" a well-deserved success with Parisian audiences and a special place in the history of ballet art.

But that was not a "pretty actress in frank dezability", but a real enchantress, carrying death with her. "Cleopatra" gave the best fees in Paris. They began to give her as a bait after the opera The Maid of Pskov with Chaliapin himself. A constellation of talented artists, unusual choreography in the "Egyptian style" and the very theme of destructive beauty, so in tune with fashionable trends in literature and painting, ensured "Cleopatra" a well-deserved success with Parisian audiences and a special place in the history of ballet art.

In St. Petersburg "Egyptian Nights" were performed in their original form. In Soviet times, the ballet was resumed at the former Mariinsky Theater three times: in 1920, 1923 and 1962. In the latest restoration, carried out by Fyodor Lopukhov, the role of Cleopatra was played by Alla Shelest. The biographer of this outstanding artist B. Lvov-Anokhin noted: “In this essentially pantomime part, she authoritatively draws a torn plastic line, uniting all separate, sharply marked strokes with a single breath, connecting all the details of the role into a single sculptural whole. Her amazing gait, unhurried movements, like frozen poses of either angry or frozen stupor, formidable turns of her head - all these are the relief features of the image of a bright theatrical fresco. At 19In 1988, Lentelefilm released the film-ballet Egyptian Nights (directed by Evgenia Popova, choreographer K. Sergeev based on M. Fokin) with Altynai Asylmuratova (Cleopatra) and Farukh Ruzimatov (Amun).

Her amazing gait, unhurried movements, like frozen poses of either angry or frozen stupor, formidable turns of her head - all these are the relief features of the image of a bright theatrical fresco. At 19In 1988, Lentelefilm released the film-ballet Egyptian Nights (directed by Evgenia Popova, choreographer K. Sergeev based on M. Fokin) with Altynai Asylmuratova (Cleopatra) and Farukh Ruzimatov (Amun).

A. Degen, I. Stupnikov

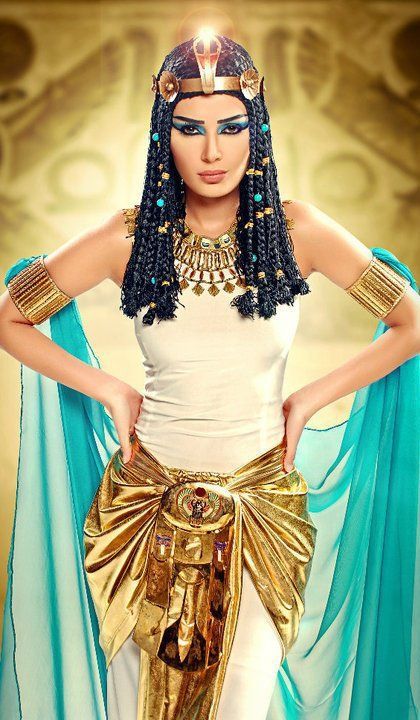

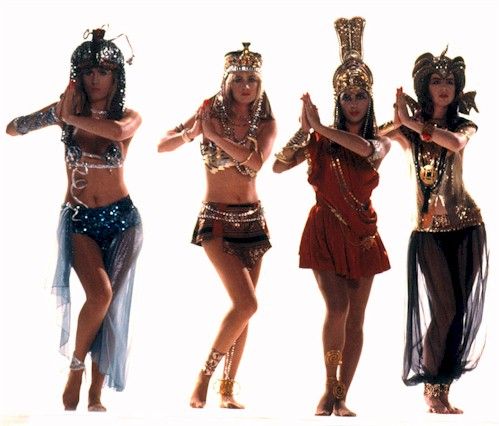

Women dancing in Egyptian style. Stock Photo ©gsdonlin 78827134

Women dancing in Egyptian style. stock photo ©gsdonlin 78827134Sign in to view November specials

Images of

VideoEditorialMusic and Sounds

Tools

Business

Our Prices

All Images

LoginRegister

Sign in

I accept the terms of the User Agreement Receive news and special offers

Women dancing with artistic makeup and Egyptian style hair

— Photo by gsdonlin

Similar royalty-free images:

View MoreView More

Same Model:

View More

Usage Information

Standard or Extended license. The standard license covers a variety of uses, including advertising, UI design, product packaging, and prints up to 500,000 copies. The Extended License includes all uses as the Standard License, with unlimited printing rights, and the use of downloaded stock images for merchandise, resale, and free distribution.

The standard license covers a variety of uses, including advertising, UI design, product packaging, and prints up to 500,000 copies. The Extended License includes all uses as the Standard License, with unlimited printing rights, and the use of downloaded stock images for merchandise, resale, and free distribution.

You can buy this stock photo and download it in high resolution up to 2400x3164. Uploaded: 24 Jul 2015

Depositphotos

- On Photo Stock

- Our plans and prices

- Solutions for business

- Blog Depositphotos

- Reference program 900 9000 9000 9000 9000 Free supplier

- Sell stock photos

- ไทย

- Norsk

- DANSK

- SUOMI

Information

- Frequently asked questions

- all documents

- +49-800-000-42-21

- Contact us

- Reviews on Depositphotos

© 2009-2022.