How to choreograph a musical theatre dance

Approaching Choreography for Musical Theatre

Dancers, dance teachers, or students, you may at one time or another find yourself choreographing for amateur (or even high school) theatre.

Having participated in community productions as a child and in my adulthood, I consider it a wonderful opportunity for people from all sectors of the public and workforce to come together and work toward a common goal, as well as an occasion to bring a variety of plays and musicals to local residents that may not otherwise attend live theatre.

If you are a dance teacher or choreographer, it can also be an opportunity to showcase your skills to a wider audience than which you encounter within your local studio or dance company.

Approaching Choreography for Musical Theatre

When approaching choreography for musical theatre, it is important that the strategy differs from that of a recital dance production.

This may seem obvious but it happens sometimes that teachers or students new to choreographing musicals tackle the job in this familiar way. I’d like to offer an approach to this particular creative process by looking at the various components of choreography for the stage and suggesting tips for effective preparation and collaboration. I hope that it will smooth the process for those new to creating movement for a musical production.

The Script

Read the script. A few times if possible, so that you really get a feel for plot, its characters, and how and why the musical numbers fit within the text. (If you’ve seen the musical, don’t rely on that particular interpretation. There may be drastic differences.)

Know the show inside and out. It will make your job easier in the long run! Imagine how things might look on the stage. Take notes on what you visualize, particularly as it relates to the musical numbers.

The Score

Photo: Paul KeleherStudy the score (not just the libretto). A copy of the piano, or rehearsal, score typically includes the vocal line and the essentials of underlying music – this is very helpful to choreographers.

Concepts and terms you’ll need to understand:

- Multiple Staves– A staff is 5 lines in a group, usually with a clef symbol on the left. In a theatrical score each ‘voice’ or instrument is likely to have its own staff. These staves are connected by brackets to show what is being played/sung at the same moment.

- Basic Notation and Time Signature – Note/rest values and how they are counted within the context of the measure/time signature. Understanding rhythm as it’s shown on the page.

- Common “Mood” Indicators – Symbols and words used in notation that indicate volume, tempo, and dynamics of what you will hear.

Get a copy of the Broadway soundtrack. If you can, try to follow along in your copy of the score. Keep in mind that these will probably NOT be identical. Make note of these changes, if you can.

Discuss with the Musical Director any cuts he/she is making within the score. Long dance breaks can be excruciatingly long with amateur dancers – it’s okay to suggest not taking that second repeat!

Long dance breaks can be excruciatingly long with amateur dancers – it’s okay to suggest not taking that second repeat!

The Staff

Hopefully in the first production meeting, the Stage Director, Musical Director, Choreographer, and Set/Lighting Designer(s) will be present to discuss the overall vision/direction for the show which is ultimately decided by the Stage Director.

Stage Director

Discuss each musical number individually with the director. You may not be responsible for every number in the production as not all may require your choreographic skills – this will need to be determined.

What to discuss:

- Where the actors will be at the top (or beginning) of the musical introduction.

- Where the actors should end up physically at the conclusion. (The director may not yet have answers for this but this information is important for creating seamless transitions in your choreography. Knowing it sooner rather than later is always helpful as you create choreography)

- How the characters have been affected or changed by the conclusion of the song.

Does it move the plot forward?

Does it move the plot forward? - Your interpretations of the musical style and how this affects movement quality. (Do you see it as athletic? A soft shoe? A Fred & Ginger-style number?) And, your feelings about what types of experience or abilities the actor should have. (Be prepared to adapt these once the chosen actor is in place).

Musical Director

Work closely with the Musical Director on song tempos (what works best for the song, dance, and singers). Remember, when creating choreography that the movement should not inhibit the vocalists ability to sing what’s required (particularly in solo work). Use dance interludes and/or a dance ensemble to show off big, “dance-y” choreography.

If you don’t read music, you will be relying on the director or pianist to make a recording (with appropriate cuts) of the music for the purposes of creating choreography. Unless you have a rehearsal accompanist, this may also prove useful during choreography practice.

Discuss and stay informed regarding the set design and be persistent about your spatial needs. I’ve often found myself with a smaller-than-originally-planned space in which to squeeze a 40-member cast for a full-company production number. Sometimes even the best-laid plans must be adjusted. Politely ask designers to keep you informed of these changes.

The Movement

Photo: Matt P.Research social dances of the time period in which the musical is set and find ways of incorporating these into your choreography.

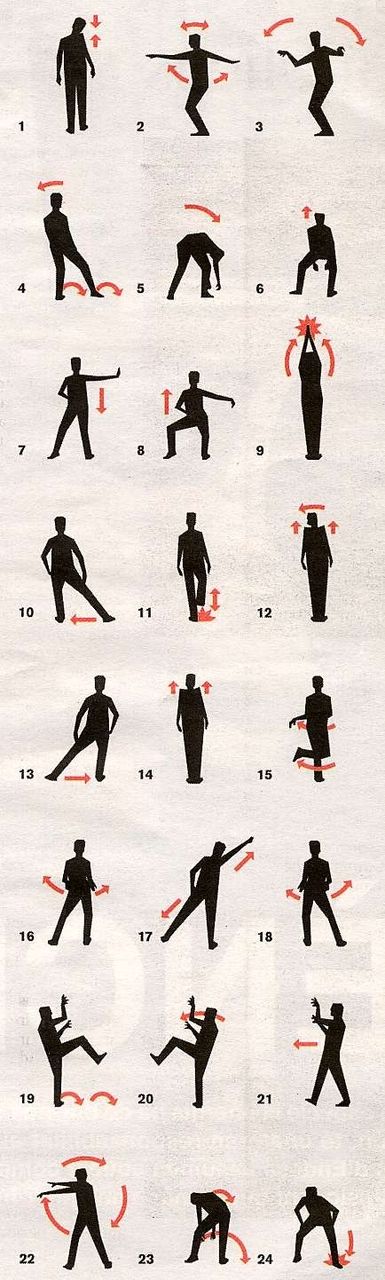

Try improvising to explore and find movement. At this stage the music you use for inspiration does not need to be music from the production, just something that gets ideas flowing. Once you have a vocabulary of movements for the character(s) or event, try drawing from that vocabulary to create the dance.

Familiarity with the Broadway or movie choreography of the musical can prove very helpful. For more than just ethical reasons, it is not a good idea to copy or recreate it movement for movement. One, your actors probably do not have the same skill set as the actors in a professional production and, two, the choreography will lack integration with the rest of the show. Look and then leave it! The overall impression of the professional version will likely stay with you, helping you to create something that is reminiscent of the original yet uniquely your own.

For more than just ethical reasons, it is not a good idea to copy or recreate it movement for movement. One, your actors probably do not have the same skill set as the actors in a professional production and, two, the choreography will lack integration with the rest of the show. Look and then leave it! The overall impression of the professional version will likely stay with you, helping you to create something that is reminiscent of the original yet uniquely your own.

Create variations on a theme and don’t be afraid to re-use movement. Many novice choreographers make the mistake of creating one long string of new movements. Just like in music, the audience enjoys recurring motifs and patterns.

Keep things simple, particularly in large group numbers. Use a core group of capable dancers, if you have them, for more intricate or spectacular choreography and use a lot of every day movements and gestures for others.

Consider how you use the stage space — create floor patterns, have actors interact and move around/with each other, and use the set. You wouldn’t believe how many amateur or high school productions I’ve seen that feature dancers lined up and facing forward during each musical number.

You wouldn’t believe how many amateur or high school productions I’ve seen that feature dancers lined up and facing forward during each musical number.

The Talent

Great musical theatre choreography does not necessarily require complex movement or staging. Much of the time, great theatrical choreographers are marked by their ingenuity. In many cases, a community theatre is made up of individuals without any formal dance training. If this reflects your situation, you must be able to work with what you’ve got.

Get your actors’ input. Whether it is relying on them to come up with a few gestures, allowing them to try different things and make choices, or drawing from their thoughts on the show or their characters, they will appreciate the collaboration if you are clear with instructions. Just like in classes for young children or beginners, be wary of giving directions that are too “open-ended.” Actors may also benefit from improvisational exercises to develop movement for their characters.

Communicate with the director about your actors’ needs throughout the rehearsal process. Community theatre participants will generally require more rehearsal than you might anticipate. Also, I’ve found that some actors really appreciate rehearsal notes that they can take for home practice. Be generous and be patient, providing extra help if you are approached.

What are your experiences with Community Theatre or choreography for musicals?

Have you choreographed productions with professional actors? How is this different from an amateur setting?

How does choreographing a show for high school students differ from community productions?

What did I leave out? You are welcome to add tips or your thoughts on the process below.

Kindly follow, like or share:

Nichelle Suzanne (owner/editor)

Nichelle Suzanne is a writer specializing in dance and online content. She is also a dance instructor with over 20 years experience teaching in dance studios, community programs, and colleges. She began Dance Advantage in 2008, equipped with a passion for movement education and an intuitive sense that a blog could bring dancers together. As a Houston-based dance writer, Nichelle covers dance performance for Dance Source Houston, Arts+Culture Texas, and other publications. She is a leader in social media within the dance community and has presented on blogging for dance organizations, including Dance/USA. Nichelle provides web consulting and writing services for dancers, dance schools and studios, and those beyond the dance world. Read Nichelle’s posts.

She began Dance Advantage in 2008, equipped with a passion for movement education and an intuitive sense that a blog could bring dancers together. As a Houston-based dance writer, Nichelle covers dance performance for Dance Source Houston, Arts+Culture Texas, and other publications. She is a leader in social media within the dance community and has presented on blogging for dance organizations, including Dance/USA. Nichelle provides web consulting and writing services for dancers, dance schools and studios, and those beyond the dance world. Read Nichelle’s posts.

danceadvantage.net

Things you should know before your first Musical Choreography

In the late 1920’s it was decided that the importance of choreography in musical productions needed to change. The choreography needed to aid the plot and character development and enhance the spirit of the show. It was something that needed to be remembered and preserved. Choreography needed to get the critics’ attention. It was at this time that choreographers started taking the spotlight. They allowed the passion and emotion of the characters shine through in each dance they created. Here are some things to know before your first Musical Choreography.

It was at this time that choreographers started taking the spotlight. They allowed the passion and emotion of the characters shine through in each dance they created. Here are some things to know before your first Musical Choreography.

A choreographer needs to work with dancers to interpret and develop ideas and transform them into a performance. Listed below are things that you should know about choreography and choreographing before you are involved in a musical performance.

Know the Music and the Show Inside-out

Get a copy of the Broadway soundtrack and DVD. Watch and listen several times so that you feel very comfortable with the music and the scenes. Study the music score, because it is important to know where the breaks, rests, and vocal lines are headed. Don’t just know the plot of the show, but know the entire script. Your dance numbers should help to enhance the story, so it is important that you understand the story.

It also helps to research the social dances of the time period of the show and use them as much as you can. Take anything you can get to make your job a little easier!

Take anything you can get to make your job a little easier!

Communicate with the director and staff

As the choreographer, you must understand the director’s vision of the show. You must be on board with his style and pacing and be supportive of his/her ideas.

You will also be working closely with the music director, costume designer, set designer, and lighting designer to be sure that all movement is compatible with the musical cues, costuming, sets, and lighting.

Keep things simple

Keeping the choreography simple, especially when there is a large group on stage is very important. A lot of fancy and complex choreography will look messy with a bunch of people on stage. Rely on arm and head movements and very simple steps. Remember that sometimes less is more. A dance should tell a story, which can be done with a simple head turn, hair flip, or hand movement. Keep in mind the ability of your dancers and what their movements need to convey to the audience.

Be aware of the space

Think about the best way to use the stage space you have. Creating floor plans will help with this. Remember that it is boring to watch dancers lined up facing the front for every choreographed number. Change it up and have the actors interact with each other, move around, and use the set.

If you are stuck for ideas, don’t panic

Think outside the box. Use improvisation. Have the dancers improve for you and use their ideas. Or simply have them improve for the show, which will give it a different feel each performance.

If you are having trouble coming up with choreography ideas, break your typical movement mold. If you always move a certain way and create dances that are all similar, challenge yourself to go in the opposite direction from your normal habits.

For something different, mesh different dance genres together. For example: a hip-hop Nutcracker Ballet. You could try modern dance or ballet moves in musical theater for something different.

Be able to imagine the end result

What will the end result look like with the costumes, sets, and lighting? It is possible that your movements could be inspired in some way by these elements. Be a visionary!!

If you are interested in learning more about musical theater, check out our class at OSMD on 144th and Dodge in West Omaha! Go to our website for more information about registration! https://www.omahaschoolofmusicanddance.com/musical-theater-omaha-ne/

Nacho Duato: "The dance is more like poetry than prose or romance"

07/30/2009 at 13:59 4139

Tags: interview, ballet, Nacho Duato

His choreographic works are known all over the world. Over the past decade, almost everyone who is connected with ballet and moves around the world, one way or another, speaks about it, and speaks with words of recognition, even if the interview or article has nothing to do with Duato. Critics endow him with epithets: "brilliant", "best among the best", they call him "the leader of the modern theater", they believe that his choreography determines the life of the ballet world space. For Russia, the work of Nacho Duato is a closed book, we did not see his performances, although the main theaters of the country invited him to performances, but were refused. Only the Moscow Musical Theater named after K.S. Stanislavsky and Vl.I.

Critics endow him with epithets: "brilliant", "best among the best", they call him "the leader of the modern theater", they believe that his choreography determines the life of the ballet world space. For Russia, the work of Nacho Duato is a closed book, we did not see his performances, although the main theaters of the country invited him to performances, but were refused. Only the Moscow Musical Theater named after K.S. Stanislavsky and Vl.I.

He received his ballet education in London (the Rambert School), Brussels (the School of Wise by Maurice Béjart) and New York (the Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre), he began studying classical ballet late. Nacho Duato staged his first one-act play three decades ago and immediately became famous in Europe. In 1990, he headed the "Compania National de danza" - the state theater in Madrid, replacing Maya Plisetskaya, who wrote about the troupe as a team full of intrigues and "secrets of the Madrid court". Duato established his own order in the theater and quickly made it famous.

He is in demand everywhere - his performances adorn the repertoire of the Netherlands Dance Theatre, the Royal Ballet of Great Britain, the American Ballet Theatre, the Stuttgart Ballet, the Australian Ballet, the Bolshoi Ballet of Canada, the Deutsche Oper, the Finnish Opera and many other companies. A fifty-year-old tall handsome man does not at all look like a master - he is younger, fit, impetuous. Arriving in Moscow for three days, he found time to meet with a correspondent.

— This is the first time you agreed to work with a Russian troupe, although you received invitations to performances from both the Bolshoi and the Mariinsky Theatres. Why did you choose the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Musical Theater?

— It didn't work out with the Mariinsky and the Bolshoi, not because I didn't want to. Our schedules simply did not match: they offered the time that I was busy. Last year, when I was in Moscow, at the Chekhov Festival, I got a call from the Musical Theatre. I had free time, we met and discussed the possibility of cooperation. Everything worked out well.

I had free time, we met and discussed the possibility of cooperation. Everything worked out well.

Frankly speaking, there was one more reason: next summer, in July, I will bring my theater to Moscow. I thought that before this responsible voyage it was worth working with a Russian troupe. This is what I wanted for a long time. I have always admired Russian theatres, performances, teachers and, of course, dancers. So, to a certain extent, my dream came true - I'm in Russia and for the first time working with a Russian troupe.

— Did the theater ask for the ballet “Na floresta”?

— This is my choice, the theater management believed me. He proposed to move the small, 23-minute ballet "Na floresta" to the music of Heitor Vila-Lobos. True, the artistic director of the ballet Sergei Filin asked for a longer performance. But I answered: “When you start rehearsing, it won’t seem enough.”

— This is your early ballet, it is staged in many theaters around the world, but Russia has not seen it in any interpretation.

- "Na floresta" in Portuguese - "In the forest". But this is not just a forest, but the Amazonian selva. The music of Vila Lobos consists of three songs about nature and is performed on the instruments of the tribes living in the forests of Brazil. These songs are not about nature in general, but about its details, if I may say so: the fabulous moon that wanders among the crowns of trees, about birds that fly from branch to branch. For me, as a choreographer, it is not so much the beauty of the surrounding world that is important, but the states that marvelous melodies evoke.

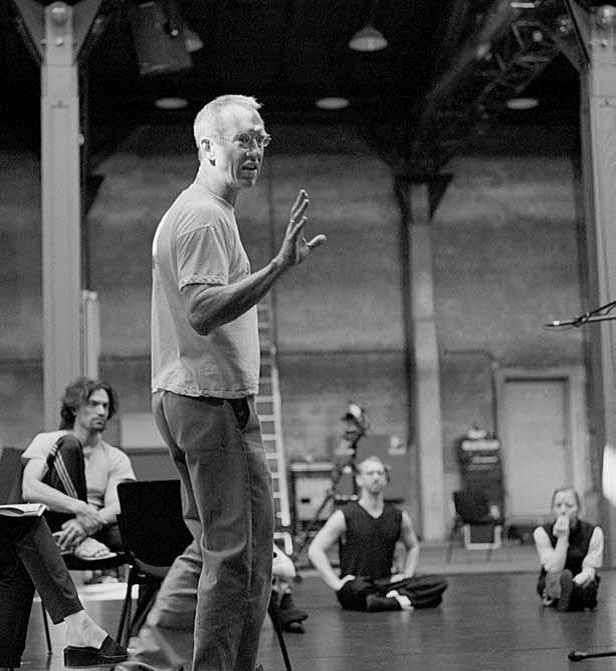

— Two days ago you met the dancers for the first time. What are your impressions?

- I am absolutely happy. I saw in them what I value most of all - the desire to work. My assistants told me with surprise that the artists are ready to rehearse for five or even seven hours in a row. I think the result will be great, because everyone wants to dance. It often happens that ballet dancers with excellent training and excellent technique strive to quickly learn the movements and free themselves. But without the desire to comprehend the meaning, nothing will work. This ballet is very passionate, emotional and romantic. We are currently working on these feelings. I try to liberate them, to cause unusual states for them.

But without the desire to comprehend the meaning, nothing will work. This ballet is very passionate, emotional and romantic. We are currently working on these feelings. I try to liberate them, to cause unusual states for them.

- So, the performers seemed to you constrained, squeezed?

- No, no. Not in this case. It's just hard for them to adjust. The classical dance style requires you to keep yourself straight and firm, and I need them to let go of themselves, to understand that they have more possibilities than they think.

— How do you achieve this?

— I show myself and explain in words. I try to suggest, for example, that the body is a branch that the wind drives on, or I ask you to feel someone as a small butterfly on a thin leaf floating on the water. I am looking for images with which artists can free their movements. They succeed. The situation is typical. All classical dancers, faced with modern choreography, are frightened and pinched. The task of the choreographer and tutors is to help them cope with this.

The task of the choreographer and tutors is to help them cope with this.

— That is, classical ballet education is a hindrance in this work?

- No way. Only classical ballet gives a rare elegance, forms a beautiful body and a special gait. Only the classical school is able to teach to control all movements, and the feet to “speak” expressively. All this is necessary for the performance of "Na floresta". In addition, the ballet has many difficult pirouettes and jettes.

— What do you need to make a ballet?

— For my ballets, especially early ones, and “Na floresta” is an old work, it is already 20 years old, we need classical dancers with a good school, high jump, expressive feet, strong rotation. They must be musical. Necessarily. Music is the main thing in my work. And, of course, the desire to work and learn something new. It turns out that I have already talked about all this. Dancers of the Musical Theater meet all these requirements in full.

— Your performances adorn the posters of the best theaters and travel all over the world. Do you accompany them?

- Unfortunately not. Not enough time. In Spain, I have my own troupe, even two: a large one, in which there are 32 dancers, and a youth troupe with 16 young artists, the youngest is only 14 years old. I just need to work with them as much as possible. In addition, we tour a lot in different countries, and on trips I am always with my artists. Therefore, ballets that have already been staged are transferred to other stages by assistants. All of them were once my dancers and now they perform my own ballets better than I could do. They treat them with great respect, I even get the impression that they love them more than I do. For this I am extremely grateful to all my assistants. I come before the premiere, just for a few days, for a maximum of a week, and finalize the performance. In this case, I picked up the work of Kevin Irving and Eva Lopez Crevillen.

- It is known that you were at the last Chekhov festival not out of idle curiosity. Then you accepted the offer to stage a ballet based on Chekhov's works. Haven't abandoned this idea?

— Now I am in the process of working on this ballet, I am thinking over the inner plot, at the moment I am talking with costume designers, lighting designers. The first rehearsal with the artists is scheduled for September 7th.

— Among them are artists only from your troupe? Do you know the premiere date?

- This performance, created by order of the Chekhov Festival, will replenish our repertoire and all performers - artists of the "Compania National de danza". The premiere will take place in Madrid in February, and then in the middle of next July we will bring this ballet to Moscow. The performance will be held as part of the Chekhov Festival. Then, next summer, on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater for a week we will show a performance about Bach, about his life and death. In it, I go on stage and dance a little.

In it, I go on stage and dance a little.

- Chekhov's performance - a plot or also about life? Or is it based on the works of the writer?

- This will be an abstract ballet dedicated to Chekhov, not based on any particular work. Nothing concrete, you will simply breathe in the "spirit" of Chekhov, immerse yourself in his atmosphere. I think that all viewers, especially you Russians, will immediately understand that the ballet is about Chekhov, feel his world. Chekhov's literary images swarm in my head, and I will show them. Now I am reading and re-reading Russian classics: plays, stories, and letters.

— John Neumeier, when staging the ballet The Seagull at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Museum Theater, used the Stanislavsky system in his work with dancers... Will you follow his example?

- No, I will not follow the Stanislavsky method. We are dancers, not dramatic actors. The nature of a ballet dancer is different. Although we talk among ourselves, we understand that dancing is not at all the same as talking or playing. I believe more in abstract ballets than ballets with stories and specific characters. In general, it is difficult for me to follow any plot, to tell stories by means of dance. I prefer to capture the spirit of the author and then create something of my own in free flight. It seems to me that dance is more like music and poetry than prose or a novel. In the drama theater where you talk, it's completely different. In classical ballet, we see pantomime in those fragments where the action is explained. And it's not close to me.

Although we talk among ourselves, we understand that dancing is not at all the same as talking or playing. I believe more in abstract ballets than ballets with stories and specific characters. In general, it is difficult for me to follow any plot, to tell stories by means of dance. I prefer to capture the spirit of the author and then create something of my own in free flight. It seems to me that dance is more like music and poetry than prose or a novel. In the drama theater where you talk, it's completely different. In classical ballet, we see pantomime in those fragments where the action is explained. And it's not close to me.

— Have you chosen musical material for Chekhov's ballet?

— Two Spanish composers work with me — Sergio Caballero and Pedro Alcalde. They create electronic music using recordings. We recorded a Russian voice that read the titles of all Chekhov's plays, separate phrases from the writer's diary. The score will also include recordings of various sounds: forests, steppes, bear footsteps, melting snow, Kremlin bells, flying birds. As well as ax blows on tree trunks, referring us to the Cherry Orchard. The score will include hymns by Alfred Schnittke performed by cello, harp and percussion. It turns out very beautiful music - spacious, open, slow. And quite unmusical, if I may say so. But I don't know how to put it more precisely.

As well as ax blows on tree trunks, referring us to the Cherry Orchard. The score will include hymns by Alfred Schnittke performed by cello, harp and percussion. It turns out very beautiful music - spacious, open, slow. And quite unmusical, if I may say so. But I don't know how to put it more precisely.

— Was it important for you to visit Melikhovo?

- Yes, and I got rich impressions. I liked Chekhov's house and was struck by his garden, garden, flowers under the windows. All this confirmed my impression that Chekhov was a bit of a hermit and a hard man, but with a kind and vulnerable heart.

— Will Chekhov's ballet be in one act?

- Yes, but big enough for me - 1 hour 20 minutes.

— Are you more interested in working in the format of a one-act ballet?

- I have multi-act performances, but there are not many of them, only four. Usually we put on a program of three half-hour ballets. But if I understand that the idea can be developed for two hours, then I can work on a full-fledged ballet. But if there are enough ideas for half an hour or an hour, then it is better to make it shorter. I often see ballets in which there is a lot of superfluous and unnecessary. So I want to cut a lot, remove whole pieces. So holding the ballet up to two hours is pointless. And keeping the audience in suspense for a long time is too difficult.

But if I understand that the idea can be developed for two hours, then I can work on a full-fledged ballet. But if there are enough ideas for half an hour or an hour, then it is better to make it shorter. I often see ballets in which there is a lot of superfluous and unnecessary. So I want to cut a lot, remove whole pieces. So holding the ballet up to two hours is pointless. And keeping the audience in suspense for a long time is too difficult.

— In the late 1990s, you staged the ballet Romeo and Juliet, which, judging by the reviews of the critics, was enthusiastically received. There is also no history, but only the spirit of Shakespeare, the atmosphere of the Renaissance, the scent of love?

- This is just a dance story. Romeo and Juliet I could not make plotless, because my choreography comes from music, and not from cold reflection. I follow Prokofiev and obediently carry out what he wrote. And he tells the story in every detail, as if creating small pictures, sketches: "Juliet's Solo", "Balcony Scene", "Death of Mercutio", "Tybalt's Jealousy". This is such precise music, under which

This is such precise music, under which

it was easy for me to create movements. I heard Mercutio being stabbed, I heard the poison running down Romeo's throat. I love this ballet very much, despite the fact that it is unusual for me. Precisely because I act as a narrator of a detailed detailed narrative. True, I take into account that Shakespeare's play is well known to everyone. If the audience did not know her, then they could get confused in the ballet "Romeo and Juliet". I also staged this neoclassical ballet for the sake of my own experiment - can I make a big plot performance? I'm glad I made it.

— You have worked with Russian teachers and Russian artists abroad and have been to Russia many times. What, in your opinion, is the difference between the type of Spanish character and Russian?

- You are probably waiting for a list of differences, but I think that the Spaniards and Russians are very similar. For example, in our countries there are rich and in many ways similar folklore dances. We, like our ancestors, love to sing, dance and play music. We have the same passionate approach to life to some extent. We, having just met, can sit down at the table, talk frankly, drink, eat and sing. Maybe we, the Spaniards, are more ardent, and you are a little more closed, but we are united by strong feelings and a love for extreme sports or something. We have much more similarities than with Americans, Germans or Japanese.

We, like our ancestors, love to sing, dance and play music. We have the same passionate approach to life to some extent. We, having just met, can sit down at the table, talk frankly, drink, eat and sing. Maybe we, the Spaniards, are more ardent, and you are a little more closed, but we are united by strong feelings and a love for extreme sports or something. We have much more similarities than with Americans, Germans or Japanese.

— Since your youth, you have been cut off from your native country for many years, living in different cities of the world. Have you always felt like a Spaniard or have you become a citizen of the world?

— When I lived in New York, Brussels, Stockholm, Amsterdam, I felt more like a Mediterranean. Now, having settled in Madrid, every year I feel more and more like a Spaniard, a resident of Madrid. When you direct the national troupe of Spain, then, while touring in different countries, you feel like an ambassador of peace, conveying pride for your country through dance. I love it. Although in my performances I do not go for the conscious expression of the national, Spanish. If this is manifested, then subconsciously. I generally like that the Spanish associations are now expanding. Previously, they were limited to bullfighting, Lorca, flamenco.

I love it. Although in my performances I do not go for the conscious expression of the national, Spanish. If this is manifested, then subconsciously. I generally like that the Spanish associations are now expanding. Previously, they were limited to bullfighting, Lorca, flamenco.

— Do you dance flamenco yourself?

- I can dance after drinking a couple of glasses.

— With what dancing experience did you come to Marie Rambert's school? After all, you were already 17 years old, too late to start your studies. In order to start mastering classical dance at this age, you need to really want it.

- Dreamed of becoming an actor, participated in musical performances, sang, danced, but not classical dances. I would love to go to the audition for the Royal Ballet, but I understood that I had no classical training. That's why I signed up for a viewing at Marie Rambert's school. The boys who showed up with me were younger and good looking, but Madame Rambert and her daughter only took me. They said, "You don't have a technique, but you have something that we like, so we accept you." But they set a condition: “If in three months you show the results that students achieve after a year of work, you can stay.” I was very lucky with my body, for which ballet came naturally. During that London period I worked from morning to evening. Three months later they left me. I told my parents that I was going to London to study as a dramatic actor. They believed that ballet was not a man's business.

They said, "You don't have a technique, but you have something that we like, so we accept you." But they set a condition: “If in three months you show the results that students achieve after a year of work, you can stay.” I was very lucky with my body, for which ballet came naturally. During that London period I worked from morning to evening. Three months later they left me. I told my parents that I was going to London to study as a dramatic actor. They believed that ballet was not a man's business.

— Did you replace Maya Plisetskaya as the head of the Company National de danza, and at the same time the artistic program of the theatre?

Maya is one of my favorite ballerinas. She is a great dancer, an amazing personality. What amazing hands! By the way, at one time I studied with Azari Plisetsky, and he was a very good teacher. I met Maya when I was working with Maurice Béjart, and I even talked to her several times after rehearsals. Now, when she comes to Spain, we meet with her.

Of course, I completely changed the aesthetics of the troupe. To the opposite. Maya Plisetskaya wanted to stage classical ballets in Spain, but I think it takes a lot of time, not years, but decades, and you have to start from school. Having headed the theater, I completely changed the repertoire, replacing classical ballets with modern ones. We dance performances by Mats Ek, Jiri Kilian, Ohad Naharin, William Forsyth. Some of them came in the early years to work with my dancers, and I myself immediately began to stage performances. So we built a completely new repertoire.

— Pina Bausch did much the same when she reoriented the theater in Wuppertal from the classics to the present.

— But Pina staged only her own works in her theater. Rather, my action is more like the step of William Forsythe.

— You have worked in various companies and performed ballets by the most famous contemporary choreographers. Which one has had the biggest impact on your personality?

— Of course, Jiri Kilian, for whom I worked at the Netherlands Dance Theatre. He staged many ballets for me, and it was in his troupe that I first acted as a choreographer. I was then 23 years old. I consider Kilian one of the best choreographers not only in modern ballet, but in its entire history. And I get inspiration from every good choreographer. Even bad performances help me: when I see them, I so want to stage this work well. Everything inspires me.

He staged many ballets for me, and it was in his troupe that I first acted as a choreographer. I was then 23 years old. I consider Kilian one of the best choreographers not only in modern ballet, but in its entire history. And I get inspiration from every good choreographer. Even bad performances help me: when I see them, I so want to stage this work well. Everything inspires me.

— How would you define your own choreographic style?

— I divide any performance into good and bad. Those who prefer the classics call me modern, and those who are engaged in modern choreography consider me neoclassical. So I don't know where I would put myself. My latest ballets are more synthetic, more and more often I add voice to them, I use some elements from the field of dramatic theater. But despite the fact that my choreography is based on classical technique, I would not call my style classical.

In general, in my opinion, even troupes with rich traditions cannot limit themselves to classical performances. The most productive way is when Swan Lake is danced today, and Kilian or Forsyth's ballet tomorrow.

The most productive way is when Swan Lake is danced today, and Kilian or Forsyth's ballet tomorrow.

— What do you see as the goal of a contemporary creator?

— Artists do not exist to reflect life, it can be seen on every corner. They exist to ask questions.

— Does the morning of your artists start with a classic exercise?

- Every day from 10.00 to 11.30 - classical barre, because I need dancers with a strong classical background. Classic every day.

— The artists of the Music Theater were captivated by your soft and even manner of rehearsals. Do you never raise your voice?

— I don't know how to work differently. We have a show on television in which some kind of ballet is being rehearsed. There everyone shouts at each other, sort things out, swear. Never encountered anything like this in my life. When I was a dancer, no one ever yelled at me, no one tortured or humiliated me. Why am I here? Because I want to work with artists. Why are they here? Because they want to work with me. We strive for a common goal, and quiet work is the norm for me.

Why are they here? Because they want to work with me. We strive for a common goal, and quiet work is the norm for me.

— In the play "Na floresta" you are also the costume designer. Is it a hobby?

Yes. I like designing costumes, although I never learned how to do it. My costumes are very simple, usually I try not to exaggerate their role and not to be smart. When I need more complex costumes, I turn to professionals.

— Are there any other hobbies?

- Riding. I started doing it as a child, even took part in competitions. During the dance career, he did not take risks and left this hobby. Three years ago, when he began to dance much less, only a few performances a year, he decided to return to his hobby, bought himself a magnificent white stallion named Santa. Horses are the most graceful, elegant, beautiful animals for me. Real ballet dancers.

— Now theaters, and not only Russian ones, are changing their plans due to the financial and economic crisis. How did it affect your troupe?

How did it affect your troupe?

— We have to figure out how to put on a performance for less money. The budget has decreased, and we are adjusting the approach to creativity. And so everything remained the same. Spectators continue to go to the theater, and our hall is always full.

Interviewed by Elena Fedorenko

“JUMP UP”, OR “EXPANDING” POWER OF ART

Mikhail Baryshnikov premiered at the American Arts Festival at Bard College

(Annndale-on-Hudson)

Baryshnikov has danced in various ballet houses around the world - from emblematic for classical ballet to underground, where they are looking for a modern language of dance, but he decided to create and its own space for experiments - the Center for the Arts in New York, in Manhattan. Showing it to American choreographer Donna Uchizono, he spontaneously returned to the old idea of working together, which months later was called "Leap Up".

This is a chamber score for three artists - a man and two women, limited by light in a closed space so that every detail and every curve of the hands, arms, torso and legs is noticeable. Listening to the music, which is the fourth character, the dancers and the choreographer created its spatial continuation, finding, as it seemed, the only possible movement to expand the meaning.

Listening to the music, which is the fourth character, the dancers and the choreographer created its spatial continuation, finding, as it seemed, the only possible movement to expand the meaning.

Leap Up is a love story with its attractions and repulsions, it is a story of life as a series of meetings and partings — from feeling to feeling, from symbol to aestheticization of the simplest, sometimes mundane gestures elevated to metaphors.

Both dancers, slowly and voluptuously swaying their hips, move in space in order to come out to a more illuminated point of the stage-room and approach the man. They walk, raking in the air with their hands and clapping their palms - these soundless applause measures the rhythm, giving the sensual movement the significance of a ritual. As in any ritual, there is also a funny thing here: when the desires of women intersect, the man grotesquely pushes one of the contenders off the stage - "until this story is finished, be patient, wait. "

"

The performance is paradoxically titled Leap Up, although the score of this contemporary pas de trois does not involve jumps. Moreover, his choreography does not develop the line of legs, only relatively monotonous movements remain - continuous small trampling, “stepping over” of legs, but extremely expressive postures of the body, bends of arms, shoulders, when each element is perceived as something independent. This close-up "brings" the artist and transforms his "choreographic signs" into sensual messages, so that the dance begins to be perceived not as born "here" and "now", but as an eternal story about the meaning of human life. This is probably why the choreographer needed the vocals of the Czech Iva Bitova woven into the music of Michael Floyd. Her unique vocal abilities and Floyd's diverse musical styles are synchronized with the rhythmic pulsations and meditative movements of the dance, establishing a connection between what emerges as the artists' inner impulse and what is outside.

M. Baryshnikov at a performance rehearsal at the Art Center in Manhattan. Photo by A. Leibovitz

Baryshnikov is the center of this constantly changing picture. Taking in multidirectional rays, he focuses them and at the same time generates new ones, causing a wide range of shades of feelings, deeply subjective, but that is why everyone understands.

The premiere took place at Bard College, the Sosnof Theater building built by Frank Gehry. The story about this architect is an independent story that was included in the film by Sidney Polak, nevertheless, it introduced it into the territory of the performance in the most natural way. Futuristic, shiny with mirror surfaces that change shape depending on the reflection of light, the facade of the theater became a natural prelude to the avant-garde searches of Baryshnikov and Uchizono.

Choreographer Donna Uchizono told how this search went.

Scene from the play. Photo by S. Berger

D. Uchizono. From the archive of Donna Uchizono Company

From the archive of Donna Uchizono Company

Maya Pramatarova. Your work is connected with avant-garde searches in the field of dance. In this sense, how do you define collaboration with Baryshnikov - as work for a narrow audience or as a desire to win a mass audience, "standing on the shoulders of a giant", as Albert Einstein said about Newton?

Donna Uchizono. Indeed, my works belong to the experimental sphere of activity of the choreographic community. Baryshnikov observed this process for many years. He contacted me when he was still with the White Oak Company and asked me to choreograph one thing for White Oak - he often invited experimental choreographers to his place, but his invitation came in the last years of White Oak, and therefore I was unable to use this opportunity. The idea to put on a dance with Misha did not disappear, and when he showed me his new Arts Center, it resurfaced again. We decided to work together, not knowing exactly when we would be able to show this work of ours.

“Leap Up” for me is a dance about Baryshnikov, who made great leaps all his life: remember his jump from the former Soviet Union to the West, his big jump from classical to modern ballet, his jump from ballet to modern dance and his search in more avant-garde directions. In this sense, I see the construction of the Center as one of his new leaps. I don't think that the 30-minute choreography of "Jump High" is a form of approach to the mainstream, that is, to a wider audience, but even if it is, I may have approached the traditional audience for a brief moment.

MP Masters become great when, among other things, they find ways to limit themselves. In another miniature shown as part of the festival performance - "Approaching the Leaf" - the dancers are limited by two-dimensional space, and in "Leap Up" this restriction is imposed on some degrees of freedom of the dancer's body. This increases the expressiveness of other movements. To what extent does this approach express the essence of your work?

DW I experiment in the field of movement, in each new work I create a new "movement vocabulary" specific to this dance, thus establishing a dialogue with the dance itself and growing a symbiotic relationship between form and content.