How to choreograph a group dance

10 Tips From the Pros

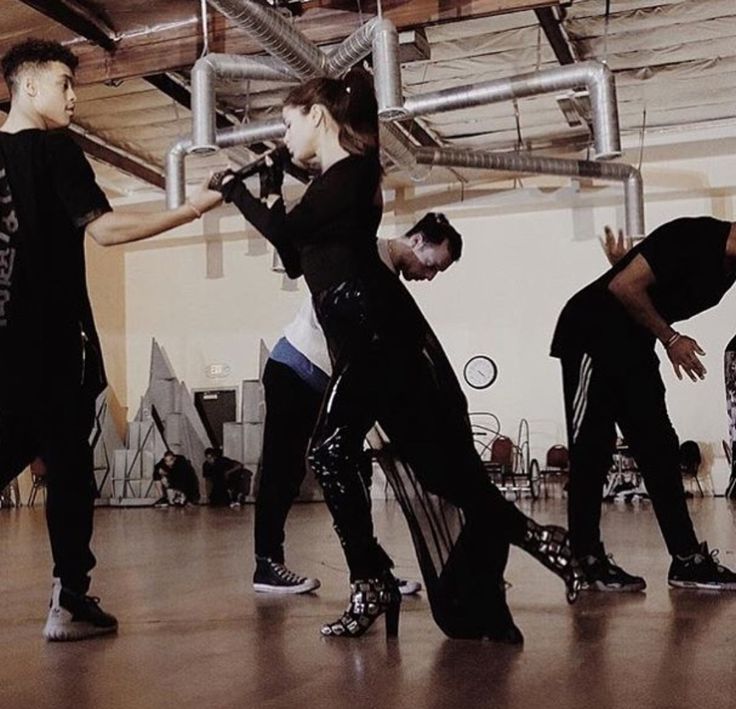

Creating movement from scratch to encompass the feeling, rhythm, and theme of a song takes a little imagination and some work, whether you're a beginner or getting ready for a big performance. When you're including the movements and dance phrases for multiple performers, too, choreographing a dance can get quite complicated. That's why we're giving you some top pro tips on how to choreograph a dance when you're feeling stuck, including methods you can use to step outside the box and spice up your routine.

1. Study the Music

If you know what music you want to choreograph your dance to, start studying. Go beyond creating movements based on the rhythm and beat of the song, and study the lyrics, the emotion, and the meaning behind the song. You can find inspiration from the feelings you get when you read the words, and embrace the emotion the artist puts into the song.

Poppin' C, a Swiss popping dancer, says, "The music is everything for me, because the way my body adapts and moves, is because of the way I feel the music. " By knowing every part of your music inside and out, you can design dance moves that really work with the beat and lyrics.

B-boy Junior holds a breaking workshop at Red Bull BC One Camp in Mumbai

© Ali Bharmal / Red Bull Content Pool

2. Watch the Pros

Take some time to watch dance-heavy musicals, like "Chicago" and "Anything Goes," competitive series like "World of Dance," and even street performers, like Logistx, to grab some inspiration for your moves. Observe the styles, transitions, and combinations of movements and note how pro dancers create a physical connection to the music. This can help motivate you to create dances that get the audience to connect with your physical interpretations of the music.

3. Plan for Audience and Venue

Think about who your performance or event is for. Consider the venue you're performing at, too, because your dance environment can help you find ways to creatively express emotion. Lighting, sound, and the overall ambiance of your venue can help you design dances that incorporate mood and emotion to connect with the audience during your performance.

4. Think About Dance Style

Choreograph with steps and dance moves that reflect a specific style. You might try incorporating hip hop steps into a classical dance to mix it up and create your own unique dance style, for example. If you're just starting out with dance choreography, try focusing on learning how to balance a specific style of dance with your unique interpretation of the music you're dancing to.

Kid David poses for a portrait at Red Bull Dance Your Style USA Finals

© Carlo Cruz/Red Bull Content Pool

5. Focus on the Basic Elements

Focus on one (or several) of the most basic elements of dance: shape, form, space, time, and energy. For form, you can focus on designing phrases and steps based on a specific form from nature, like an animal or landform. Use your stage space to showcase explosive energy and give certain aspects of your performance a punch of emotion that keeps your audience engaged.

6. Don't Start at the Beginning

If you're stuck trying to figure out how to start your dance, plan it out from the middle or from the end. Tell a story through your dance choreography and plan out the climatic elements before the small steps to help you flesh out where you want to go with your ideas. Once you've outlined the basic structure of your choreography, piece it together into an entire work.

Tell a story through your dance choreography and plan out the climatic elements before the small steps to help you flesh out where you want to go with your ideas. Once you've outlined the basic structure of your choreography, piece it together into an entire work.

7. Try Choreographing Without Music

Dance in silence. It might seem like a crazy idea since you're choreographing the dance to a specific song. However, just letting your body move and flow with different tunes you imagine can help you step outside your comfort zone and incorporate challenging moves and dance steps that you might not have thought to pair with a song or score. When you discover something you like, pair it with other steps you've already developed and start fitting your moves to the music.

Poppin C shows off his moves during a photoshoot in Lausanne

© Torvioll Jashari / Red Bull Content Pool

8. Embrace Post-Modernism

Study early modern dance forms and styles that can get your imagination flowing. Dancers from the mid-century modern era through the 1950s and '60s (such as Anna Halprin, one of post-modern dance's pioneers) would incorporate a whole world of nontraditional moves in their choreography. Slow walking, vocals, and even common gestures can make imaginative additions to your overall work.

Dancers from the mid-century modern era through the 1950s and '60s (such as Anna Halprin, one of post-modern dance's pioneers) would incorporate a whole world of nontraditional moves in their choreography. Slow walking, vocals, and even common gestures can make imaginative additions to your overall work.

9. Incorporate the Classics

Use classical ballet, traditional ballroom steps, or other classic dance moves to mix up your style. It can be a startling transition for an audience to see a classical ballet step snapped in between freestyle phrases. Combining classical techniques with your dance design can add interest and suspense to your performances.

10. Use Other Art Forms as Inspiration

Don't just focus on music and dance. Look at all kinds of art forms, from two-dimensional paintings to live art performances. Take note of the different emotions and use of space, shapes, and forms that different artworks incorporate, and think about your interpretations and how you can convey that in movement. Use this as fuel for your inspiration when choreographing short phrases. Keep up to date on new forms of art to get inspired and avoid the dreaded writer's block (for dancers).

Use this as fuel for your inspiration when choreographing short phrases. Keep up to date on new forms of art to get inspired and avoid the dreaded writer's block (for dancers).

More Pro Tips to Choreograph a Dance

Arlene Phillips CBE, a British choreographer and theater director, got her start pro dancing and choreographing in the 1970s. She's been the choreographer for a variety of performances over the years, including live theater. Her advice for aspiring dancers includes some helpful choreographing tips:

Tell the music's story through your movements

Keep practicing with imaginative steps

Be determined to learn from your mistakes

Challenge yourself with unique rhythms, styles, and techniques

Plan out your most impactful elements then work in additional steps around those

Keep practicing your choreographing techniques

Don't be afraid to learn something new

One of the most important things to keep in mind when choreographing a dance, though, is to embrace diversity. Don't be afraid to do something different or outside the norm. Try incorporating new styles or steps to make your dance fresh, and study all types of art to get excited about your work. The more you challenge yourself to think outside the box, the more creative and unique you can be with your choreography.

Don't be afraid to do something different or outside the norm. Try incorporating new styles or steps to make your dance fresh, and study all types of art to get excited about your work. The more you challenge yourself to think outside the box, the more creative and unique you can be with your choreography.

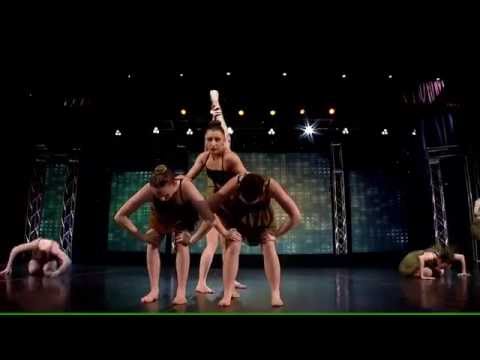

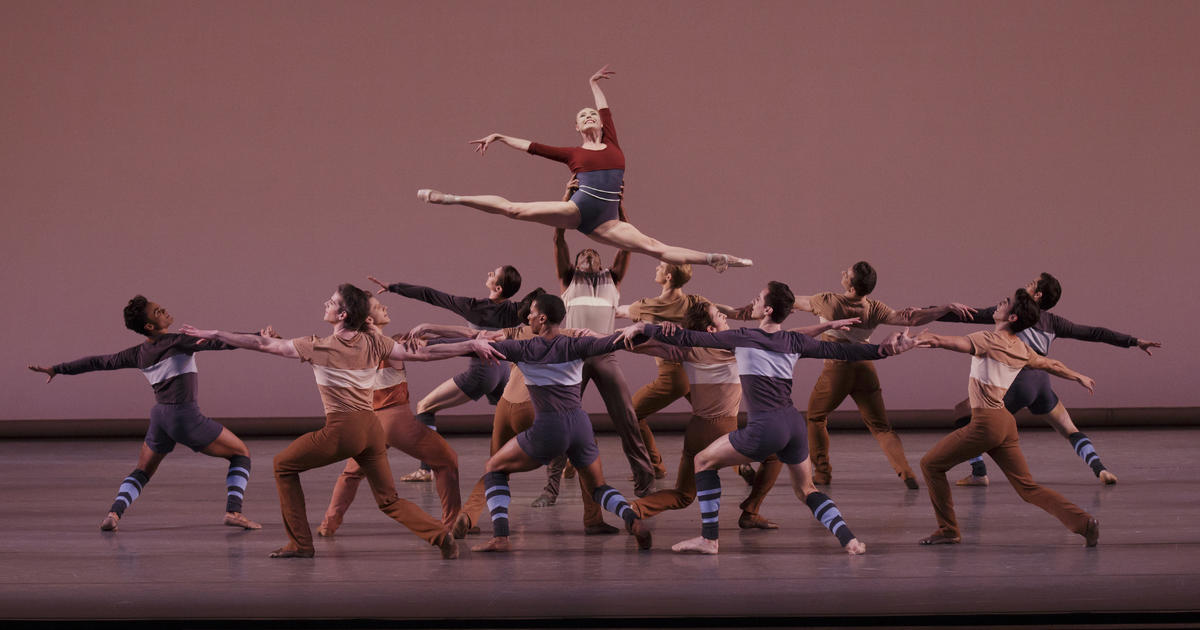

Here's How To Choreograph for Large Groups

Choreographer Matthew Neenan, who danced in Pennsylvania Ballet’s corps, was eager to include plenty of dancers in his first work for the company back in 1998. “As a corps member, I’d always been around large groups, and it excited me to get everyone in there!” says Neenan, who ended up using 20 dancers in his ballet. But with a large cast come a lot of complications—complications that can sometimes overshadow the fun of having all those dancers to play with. What are the keys to clutter-free, universally flattering large-group choreo? Here are a few creative and practical ways to devise choreography that will help you highlight your cast’s strengths.

Define Your Concept

Joanne Chapman, director of Joanne Chapman School of Dance in Brampton, ON, mounts production numbers every year for 55 to 115 dancers aged 5 to 18. Her cardinal rule is to find a clear theme—and stick with it. “From the beginning, you have to have a well-defined concept,” she says. “Make a decision about what you’re going to say, and stay true to that. If you’re trying to tell a story, you have to be very explicit—otherwise, it can end up looking like a highway at rush hour.” Her piece Drove All Night, for example, had a 35-

member cast, for which she constructed pure-jazz choreography, avoiding aerials and acrobatics because they would have confused the overall look. “With a large group, you can’t afford to get sidetracked,” she says.

One of Suzi Taylor’s numbers for this year’s New York City Dance Alliance Nationals featured a cast of 145 (!) (Photo by Eduardo Patino, courtesy New York City Dance Alliance)

Emphasize Cleanliness

Even with a clearly defined concept, it’s easy for choreography to get muddy with a lot of dancers onstage. When teaching the steps, it’s important to be very specific about body alignment, arms, focus and direction changes. Chapman holds pre-planning sessions with her assistants to make sure everyone’s on the same page about the details. Then she rehearses her dancers in small groups, looking for inconsistencies and tightening up unison work.

When teaching the steps, it’s important to be very specific about body alignment, arms, focus and direction changes. Chapman holds pre-planning sessions with her assistants to make sure everyone’s on the same page about the details. Then she rehearses her dancers in small groups, looking for inconsistencies and tightening up unison work.

Even if that kind of intense organization isn’t your style, it’s still smart to go into the studio with a battle plan. Though Neenan likes “to allow for some messes to happen, some bump-ins and such,” he still brainstorms big ideas and traffic patterns before beginning rehearsals. Mistakes, he says, are part of the journey. Just make sure that you take an active role in correcting and reshaping them.

Be Sensitive to Technical Levels

Inevitably, the range of abilities within a big cast will vary. Subdividing the piece into sections based on technical level can help you show each group’s strengths. But when the whole ensemble comes together, it can be helpful to keep the level of difficulty relatively low.

That doesn’t mean choreography for the whole group can’t be interesting. Chapman makes even simple phrases exciting by inserting featured moments for her strongest dancers. “One dancer doing turns or acrobatic tricks while everyone else is on the floor, for example, can really spice things up,” she says. “We also do a lot of canons, with each line starting the same phrase on a different count. That creates a very cool wave effect.”

Anticipate Logistical Hurdles

Getting groups of dancers on and off the stage is one of the toughest challenges of large pieces. Chapman makes transitions between sections seamless by using a consistent movement (like a jazz walk) for all entrances and exits, and slightly overlaps their timing to ensure a smooth flow. Neenan sometimes likes to have dancers in his larger pieces exit with structured improv, so they still hold visual interest even while others are entering—a pleasingly layered effect.

The most glaring logistical issue when working with a large cast is how to fit everyone onstage. Standard tricks like staggered lines are useful, but sometimes you’ll need to think more creatively. For this year’s New York City Dance Alliance Nationals Senior Outstanding Dancer number, Suzi Taylor literally couldn’t get all 145 of her dancers to move onstage at once without colliding—but she ended up turning that to her advantage. “I used the space on the floor in front of the stage, working level changes with unison and creating ripples of movement,” she says. “It turned out to be pretty stunning!”

Standard tricks like staggered lines are useful, but sometimes you’ll need to think more creatively. For this year’s New York City Dance Alliance Nationals Senior Outstanding Dancer number, Suzi Taylor literally couldn’t get all 145 of her dancers to move onstage at once without colliding—but she ended up turning that to her advantage. “I used the space on the floor in front of the stage, working level changes with unison and creating ripples of movement,” she says. “It turned out to be pretty stunning!”

Sometimes asymmetry can be the most arresting way to arrange a large group of dancers. Neenan encourages thinking about the possibilities beyond traditional lines. “I like to put dancers in ‘communities’, sharing the stage in more of a normal, ‘street’ fashion, rather than symmetrical patterns,” he says. Those kinds of groupings have the extra benefit of allowing more dancers to share a small space. “And using space creatively can be part of how you develop your original voice as a choreographer,” he says. “There’s only so much vocabulary—this is another way put your stamp on something.”

“There’s only so much vocabulary—this is another way put your stamp on something.”

| Main page CATEGORIES: Archeology TOP 10 on the site Preparation of disinfectant solutions of various concentrations Technique of the lower direct ball delivery. Franco-Prussian war (causes and consequences) Organization of the work of the treatment room Semantic and mechanical memorization, their place and role in the assimilation of knowledge Communication barriers and ways to overcome them Processing of reusable medical devices Samples of journalistic style text Four types of rebalancing Problems with answers for the All-Russian Olympiad in Law We will help you write your papers! DID YOU KNOW? The influence of society on a person Preparation of disinfectant solutions of various concentrations Practical work in geography for the 6th grade Organization of the work of the treatment room Changes in inanimate nature in autumn Treatment room cleaning Solfeggio. Beam systems. Determination of support reactions and pinching moments | ⇐ PreviousPage 21 of 29Next ⇒ The group is given the task of compiling and dancing a group dance that would symbolize the development of the group from the first lesson to the last. At the same time, the leader leaves the group, leaving the group to come up with and stage a group dance completely independently. In the instructions he gives to the group, he remarks that he may also have a role to play in this dance. In this case, before the final dance is performed, the group must give him the task of what to do. When the dance is thought up and rehearsed, the group calls the leader - and they all dance together in a group dance. There is a discussion at the end of each exercise. The discussion takes place first in pairs (if the exercise was performed in pairs), and then in the group. Possible questions for general discussion. How did you feel doing this or that exercise? In which exercise did you feel most (least) comfortable? Which movement principles did you use more (less)? How did the participants - the observers and the dancers themselves - feel? What images, associations arose in connection with the dance of the central participant? How can you describe the dance of this or that member of the group in a few words? What are the characteristics of the participants' dance expression? How do you feel now, after a series of exercises? Is your current state different from what it was before it began? If yes, then what? How did the participants feel as facilitators? And the followers? Which interpersonal position - "leader" or "follower" - is more often used by participants in communication? What did they experience when they danced like another person, trying on his expression? When did the participants feel more comfortable: when they imitated the movements of others or when they themselves were leading? How different is the dance "I am real" from the dance "I am ideal"? Was the dance aimed at self-expression or interaction with others? How did the participants feel when their personal space was invaded by other people? Did they feel the same when interacting with different people? What associations, metaphors come to your mind about the dance of your mirror image? What is your attitude towards the person seen in the mirror? Was it difficult to take the initiative in making and breaking contact? Your feelings as the "initiator" of positive (negative) relationships. Your reaction to the partner who “initiated” the relationship during the exercise. What relationships (positive or negative) do you most often initiate in real relationships with people? What kind of relationships do other people initiate towards you? Which relationships were easier to express, which ones were more difficult? What means of expression (gestures, facial expressions, postures, gaze, etc.) were used by participants to express dominance, submission, hatred and love? How would you rate the experience gained in the group? How have intra-group interpersonal relationships changed? Has your attitude towards the group and each member changed? How do you see your place in the group now? What about at the start of class?

CONTACT IMPROVISATION

Contact improvisation was proposed by American dancer and teacher Steve Paxton in 1972. In his work, Paxton used "release techniques" (meaning the release of new motor abilities and release from muscle clamps), aikido and some other methods. Contact improvisation and composition exercises are a simple and visual teaching of interaction metastructures: attachment, opposition and complementarity (additionality). One of the main tasks of contact improvisation is also the release of clients from negative experiences and complexes associated with underestimation or fear of their body, through a return to their own body, through its acquisition. In addition to this main task, the joints and muscles are also freed from pain and tension, and the work of the body is improved in all possible situations. Most often, contact improvisation is a sequence of improvised movements, usually from the arsenal of avant-garde dance. This sequence is the result of the intuitive interaction of two or more participants who explore the change in movement. Contact improvisation is a form of movement in dance, in a duet. Two people move together in contact, maintaining a spontaneous bodily, physical dialogue through kinesthetic sensory cues. Some principles of contact improvisation (Novack, 1990): 1. The movement follows the displacement of the point of contact between the partners' bodies. The movements associated with the touch of two bodies predominate, with the search for spatial trajectories when interacting with the weight of the partner's body. The dance is guided by the feelings of the partners, their intention to maintain physical contact and continue to seek mutual support. 2. Feel with skin. Almost constant physical contact between partners is aimed at using the entire surface of the body to support their own weight and the weight of a partner. 3. Overflow. Attention is directed to body segments and to movement in several directions at the same time. Sequential inclusion of body parts combined with sending them in several different directions. The constant shift of weight to neighboring segments expands the possibilities of improvisation and softens falls and rolls. The segmentation of the body and the multiplicity of directions create the effect of "jointness" of movement. Unlike traditional modern dance techniques, where similar techniques are also used, but the emphasis is on one direction or simple antiphase, contact improvisation often uses a free flow of inertia without strict control. 4. Feeling of movement from within. Attention is focused on the inner space of the body. Secondary attention is on the shape of the body in space. Contact improvisers spend most of their time focusing their attention internally in order to perceive the subtlest changes in weight and ensure the safety of themselves and their partner. 5. Use of spherical space (360 degrees). Climbing in an arc requires less muscle effort, while falling in an arc softens the impact. 6. Follow inertia, weight and flow. A free, growing flow of movement combined with alternating active and passive use of weight. Contact improvisers often emphasize the importance of the continuity of movement when it is not known in advance where it may lead. They can actively pull, push, or lift a partner following a rush of energy, or let inertia drag them passively. 7. The implied presence of spectators. Proximity to the audience, usually sitting in a circle, without a formally designated stage. 8. The participant is an ordinary person. 9. Let the dance happen. Choreographic structures organized into a sequence of duets, sometimes trios or large groups, and an almost continuous physical interaction of the participants. Such choreographic elements as the organization of space, the choice of the theme of the movement, the use of dramatic gestures, are very rarely used intentionally. But choreographic forms are nevertheless born from the dynamics of the change of participants and spontaneously arising moods and states in the process of improvisation. 10. Everyone is equally important. Absence of external insignia between the participants - such as the order of entry, duration of the dance, costume. While the facilitators organize the sessions according to their own ideas, some useful suggestions are given below (Morgenrot, http://www.dancetrio.ipd.ru/Articles). Dance improvisation does not require ready-made skills and mastery. However, if there are both experienced members and newcomers in the group, this can be frustrating for both. In this case, participants can be divided into subgroups according to their level for a while. Or the exercises can be adapted so that beginners can work with simpler versions. Then more experienced participants will be able to work separately. In some circumstances, a mixed group serves as a stimulus for growth - and thus the situation is beneficial for both parties. Many of the improvisation exercises can be adapted for groups of three to thirty people, with ten to twelve participants considered optimal. Twelve participants can easily be divided into subgroups; several participants can be observers while others are moving. One or two main topics of the session help the group to develop and improve the acquired skills. Each topic includes some simple and some difficult exercises. A simple exercise can mean solo or pair work, or a limited choice of activities for a group. More complex tasks connect composition with fantasy and offer greater freedom of choice. Working on simple exercises prepares the group for more complex tasks in the same area. Since both physical involvement and awareness are central to improvisation, topics that involve a good balance of movement and thought can be devoted to separate sessions. When choosing a sequence of exercises for a session, the facilitator should keep in mind the work done earlier. If participants are doing an exercise that increases spatial awareness, then this awareness should help them throughout the session, even if the subsequent exercises are not about working with space. Music can create an atmosphere and keep the energy and concentration of the group; she can also determine the length of the improvisation; it can unite the efforts of the participants, influencing the style, speed and energy of their movement. Each meeting starts with a warm-up. The warm-up should be familiar to the facilitator and not be overly technical. The technical warm-up improves participants' motor skills, but it can also interfere with the exploration process as it provides a standard set of movements. The facilitator helps start and end the session. One of the most undesirable errors of group improvisation is the chaotic beginning. In general, improvisation should begin with the movement of one person, to which the rest join. Improvisation can be started by someone with the right momentum, or the facilitator can ask someone to start. Sometimes it is useful to choose a participant who is able to give the necessary material; sometimes the facilitator may choose someone who does not take the initiative. There are various ways to end an improvisation, but in all cases the participants must end it in a state of clarity. Before the start of the improvisation, the facilitator can inform the participants about its duration (for example, one minute, half an hour). A discussion at the end of an exercise or series of exercises helps participants review and evaluate the decisions they have made, find other opportunities they could try, and recognize what they were doing instinctively. The discussions are not intended to decide what was done right and what was wrong, but to understand the consequences of the choice made. If the group repeats the exercise after the discussion, the participants can see how the new understanding affects the outcome.

Techniques

Improvisation classes teach skills, but they also require skill and skill. Participants must get used to, get used to the process of improvisation, to concentration and focus. ⇐ Previous16171819202122232425Next ⇒ See also: How to listen correctly to an interlocutor Typical mistakes when shooting basketball The adoption of Christianity in Rus' and its significance US media |

| This page was last modified: 2017-02-06; views: 137; Page copyright infringement; We will help you write your paper! infopedia. |

I want to dance. 10 misconceptions about dancing

The desire to learn to dance is natural and natural in the modern world. You can list the reasons, starting with obvious and popular pragmatic desires, for example, to start moving or losing weight, ending with unconscious and even existential ones.

This is due to the fact that dancing is at the subtle intersection of the inner and outer worlds, physical and spiritual. Above this, music becomes a driver that cannot leave anyone indifferent.

In dancing, magic happens inside a person, which is not always noticeable when viewed from the side. At the initial stage, it is the external picture that attracts to dances, and sometimes repels, as it seems too frivolous and superficial.

But there are even stronger obstacles that stop many people from starting dancing. These illusions and delusions roam the minds of the majority, and are often afraid to ask about them directly, or they ask the question about it so often that they are no longer ready to hear an honest direct answer. I will try to do it in this article.

There are many examples of contemporary dance instructors sharing their thoughts about not expecting to be in the dance industry. Once upon a time there was a man and was engaged in adult, serious business. Sometimes even very serious. A person could have children and even grandchildren. I saw dances only on stage or on TV. For reasons unknown to himself, he ended up in dances. At first, everything seemed like entertainment and a useful pastime. But time has passed, and a person catches himself thinking that he thinks about dancing not just every day, but really all the time. A couple of years pass, and he already becomes a teacher or organizer of some event.

A similar path can start at 15 or 55 years old. The only difference will be in the self-perception of the starting stage, that it’s too late to dance. In fact, for each age there is its own dance direction, which can reveal it to the greatest extent at this stage. Hip-hop or breaking is closer to children and teenagers, and Argentine tango is closer to adults. It's never too late to start dancing. You need to make the right choice of dance style based on several parameters: age, gender, music, goal. There is a dance direction for any arrangement.

Misconception 2: men don't dance

Our culture has a number of restrictions related to dancing. Most of these causes are psychological and lie outside the realm of rational reasoning.

First, in our culture, in principle, dancing for pleasure or self-expression appeared relatively recently. 20-30 years ago dance clubs were only for children. To start dancing even in adolescence was considered exotic.

Secondly, the aesthetics of the body in our country for men is not in the focus of attention. In general, this can be attributed to the fact that Russian men try hard not to draw attention to their appearance and clothing. Men in our country use other tools for this.

Third, dancing is associated with entertainment and alcohol. If a man feels serious and respectable, then he either does not have time or desire for this.

Nowadays the general cultural background has changed and the result is that men are learning to dance. It becomes as much a sign of masculinity as clothing, hair or beard.

Unfortunately, many misconceptions remain even among those who have already started dancing. Dance teachers do not always pay attention to this, as it seems to them that this is a matter of course.

Fallacy 3: special training is needed

For the outside observer, there is always a cognitive dissonance about what dance is. What he sees on the big stage in the form of a show with sweeping movements and splits is obviously dancing. Breakers doing unimaginable elements in the air and on their hands, competing with each other, also seem to be dancing. Pensioners in the park waltz. Dancing again, but for some reason everyone is so different. How to understand that this is a dance, and what physical criteria should be in the body.

What he sees on the big stage in the form of a show with sweeping movements and splits is obviously dancing. Breakers doing unimaginable elements in the air and on their hands, competing with each other, also seem to be dancing. Pensioners in the park waltz. Dancing again, but for some reason everyone is so different. How to understand that this is a dance, and what physical criteria should be in the body.

In fact, any self-expression through the body to music can be attributed to dance. There are a number of reservations, but they are not essential. For self-expression, a person uses the set of plastics that he has. Subtlety and technique do not depend on extreme ways of self-expression, and it often happens that splits and somersaults interfere with a meaningful dance. The development of plasticity and the expansion of the body's capabilities are part of the preparation of the dancer, but not an end in itself.

Misconception 4: You must learn to dance in pairs

In couple dancing, the final learning outcome is that the couple dances at a party. It would seem that you should always train together to get the desired result. This is not true. Let's take an example from boxing. An indicator of a boxer's skill is a fight with an opponent, but this does not mean that he constantly has to fight. Also, the ability to dance is built on the possession of one's own body and the ability to interact.

It would seem that you should always train together to get the desired result. This is not true. Let's take an example from boxing. An indicator of a boxer's skill is a fight with an opponent, but this does not mean that he constantly has to fight. Also, the ability to dance is built on the possession of one's own body and the ability to interact.

The skill of the teacher is the correct selection of methods so that the student masters the skill. Based on the skill, you can engage in creativity and self-expression in dance. Not everyone knows, but it is no coincidence that almost all social dance dancers have a serious dance background, which is based on the development of individual techniques.

The same can be attributed to the interaction in pairs. The ability to separate in oneself the one who leads and the one who follows the lead is impossible within the framework of studying the sequence of movements in pairs. For this, there are special exercises that make the skill more versatile. For this, the presence of a permanent couple is not necessary, as well as the regular presence of a partner in general.

For this, the presence of a permanent couple is not necessary, as well as the regular presence of a partner in general.

IMPORTANT! You can’t experiment at a party, and everything should be in its place there: men dance with women.

Getting rid of illusions is a complex internal process. If you leave them to yourself, you can even get the opposite result.

Misconception 5: plasticity and stretching are mandatory attributes of dance

Much depends on the genre of dance that you want to master. In previous articles, I have already mentioned that different dance styles are suitable for different ages. It is appropriate to dance hip-hop in adolescence or youth, Argentine tango is a more adult dance, it is important to enter classical choreography at a young age.

The degree of necessary plasticity and sensitivity to the dance direction also correlates. For example, breaking requires great physical effort and dexterity. Elements are built on acrobatics and high speed of execution. Who are they more suitable for? Obviously young people.

Who are they more suitable for? Obviously young people.

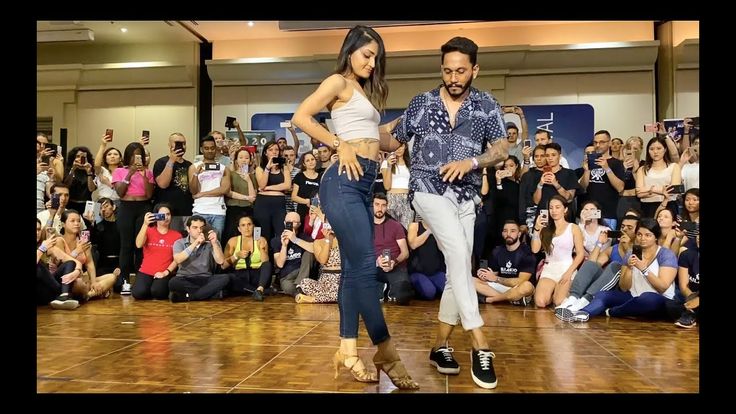

There is a lot of interaction in salsa. It is necessary to feel the partner subtly, to be able to show a variety of figures and elements. Twine or acrobatics are completely inappropriate here. However, a variety of ways to show oneself are required. Accordingly, the dance is youthful, but not at all childish.

The older the dance, the less stretching or acrobatics is required. The main emphasis is on the quality of technology, the variety of ideas and the ability to show plasticity.

Misconception 6: Mirrors are necessary for learning

There is a set of tools that dancers use to learn how to dance. The fact is that the dancer needs to receive feedback on how his movements look from the side. It is impossible to dance and see yourself from the side at the same time. The most common tool is a mirror. But not the only one.

Like any auxiliary tool, mirrors have a positive and a negative effect. The positive is that they can receive feedback in real time and technically it is not very difficult. The downside can be dependence on mirrors. A situation where a dancer cannot capture the feeling of dancing, such as on stage or at a party. For these purposes, you can use, among other things, video filming or proper preparation.

The positive is that they can receive feedback in real time and technically it is not very difficult. The downside can be dependence on mirrors. A situation where a dancer cannot capture the feeling of dancing, such as on stage or at a party. For these purposes, you can use, among other things, video filming or proper preparation.

In many countries in Latin America, dance classrooms are not equipped with mirrors. Classes are held in bars or large halls. The dancers initially form the skill of focusing on the inner sensation, and not the habit of looking for their reflection in the mirror with their eyes.

Misconception 7: there is a lot of obsceneness in dancing

A common question from novice dancers who are taking their first steps in more contact couple dances is “in order to dance cool, there must be passion inside the couple?”. I immediately answer that no, not necessarily. Kizomba, bachata and Argentine tango attract many with their close contact. Like any other contact in our everyday life, in dances, contact can be different. We hug friends, parents, children. These hugs can wear many different shades. Sexual overtones are one of many.

Like any other contact in our everyday life, in dances, contact can be different. We hug friends, parents, children. These hugs can wear many different shades. Sexual overtones are one of many.

The culture of dance also includes the boundaries of what is acceptable. A compliment from a well-mannered person is different from a statement about female sexuality by a gopnik. Usually, those who study at a dance school already have an idea of what boundaries should not be crossed. A good dance from a technical point of view will never look vulgar or vulgar.

Dancers always have a choice about the boundaries of contact. Most prefer to leave a good impression of themselves, as word spreads just as fast in the dance world.

Misconception 8: the best dancers are the bearers of culture

Even the very question of the origin of this or that dance can be paradoxical and ambiguous, especially when it comes to its development and performance.

For example, the Viennese Waltz did not originate in Vienna, but in Germany. Salsa has its main roots in the USA, not in Cuba. The famous Greek folk dance sirtaki was invented for the film "Zorba the Greek" and appeared only in 1964.

The same can be attributed to the development of modern dance styles. Korea is known for its world-leading break dancers. People go to Turkey for Argentine tango, Spain is strong with excellent salsa and bachata dancers, in Egypt, Russians are considered the best belly-dance performers.

A good dance is based on quality training and diligence. Skin color, place of birth and age are secondary. Exotic appearance, unfortunately, is often a reason to be more superficial about one's own professional development. This becomes the reason for the low level of teaching among the bearers of culture. I am sure that few readers of this post will be ready to conduct a master class in Russian folk dance outside of Russia.

The mastery of mastering and teaching a particular style does not depend on the dancer's homeland. And "they absorbed the dance with their mother's milk" is nothing more than a common misconception.

And "they absorbed the dance with their mother's milk" is nothing more than a common misconception.

Misconception 9: You have to know a lot of moves to learn to dance

Focusing on learning a lot of moves often detracts from the essence of dance. Of course, the sequence of figures is important. Especially at the start. Over time, the dancer should have an understanding of how movements can be generated independently. Accordingly, instead of memorizing millions of figures, you can understand how to create them.

From every system of improvisation that a dancer can use as an instrument, dozens, hundreds or thousands of variations are derived. This frees the head from trying to reproduce the exact sequence and definitely adds freedom in the performance of the dance.

The huge theme of musicality can be attributed to the same question. Not every pre-conceived or learned sequence will fit specific music. The dance should give freedom, and not drive the dancer into the shell of the ropes.

Misconception 10: dancing is homosexual

The unusually high attention to the body and flair from stories about professional ballet led to the spread of this myth, among other things. Unfortunately, such an idea still exists in the minds of our fellow citizens.

The dance industry is now very broad and is represented by many dance styles. Some of them can even be called homophobic. Dances reflect the general attitude to the world and it is different depending on the life position and worldview of a person.

In many dances there is contact between the dancers. In Russia, dance contact between men has always been perceived very intensely. In most other countries it is different. An example of the fact that this tension is associated only with the dance theme and does not apply to other areas is, for example, wrestling. When practicing techniques, men are in much closer contact with each other. Sometimes lying on the floor and holding each other tightly.

All rules for solfeggio

All rules for solfeggio

The method was based on the idea that two people are needed to dance. This work is a study of the ability of consciousness to merge with the body in the present moment and remain in it when conditions have changed. Paxton's ideas gave rise to a new technical approach that allows you to work both directly with the body and with certain kinesthetic images that correspond to movement. Contact improvisation is used today as a means of teaching dance, as therapy, and as a way to discover new things. From the point of view of dance therapy, contact improvisation can be considered as a system of collective physical interactions, the purpose of which is to develop the communicative and sensitive capabilities of the human body. Participants go through the following stages of contact interactions: recognition, study, dialogue, construction and improvisation.

The method was based on the idea that two people are needed to dance. This work is a study of the ability of consciousness to merge with the body in the present moment and remain in it when conditions have changed. Paxton's ideas gave rise to a new technical approach that allows you to work both directly with the body and with certain kinesthetic images that correspond to movement. Contact improvisation is used today as a means of teaching dance, as therapy, and as a way to discover new things. From the point of view of dance therapy, contact improvisation can be considered as a system of collective physical interactions, the purpose of which is to develop the communicative and sensitive capabilities of the human body. Participants go through the following stages of contact interactions: recognition, study, dialogue, construction and improvisation.  Group improvisation exercises develop a holistic vision of the situation and one's place in it. Many exercises are aimed at maintaining a certain state in changing conditions, and this skill of preservation is quite easily transferred to life situations (Girshon, 2000b).

Group improvisation exercises develop a holistic vision of the situation and one's place in it. Many exercises are aimed at maintaining a certain state in changing conditions, and this skill of preservation is quite easily transferred to life situations (Girshon, 2000b).  The body, as it becomes aware of the sensations of inertia, weight and balance, learns to relax, get rid of excess muscle tension and refuses some intentions and attitudes in order not to contradict the natural course of things, to be in the “flow”, to use what is at hand. Simple and clear exercises allow couples to explore the specific relationships that have to be dealt with in free improvisation.

The body, as it becomes aware of the sensations of inertia, weight and balance, learns to relax, get rid of excess muscle tension and refuses some intentions and attitudes in order not to contradict the natural course of things, to be in the “flow”, to use what is at hand. Simple and clear exercises allow couples to explore the specific relationships that have to be dealt with in free improvisation.

Masters, for whom the perception of gravity has become part of their nature, can more often than beginners consciously project their body into space. At the same time, even in solo improvisation, the "contactee" often retains the inner center of attention and preoccupation with movement.

Masters, for whom the perception of gravity has become part of their nature, can more often than beginners consciously project their body into space. At the same time, even in solo improvisation, the "contactee" often retains the inner center of attention and preoccupation with movement.  Acceptance of a behavioral or natural state of affairs; participants tend to avoid movements reminiscent of traditional dance techniques and make no distinction between everyday and dance moves. They straighten their clothes, laugh, cough, comb their hair, if necessary, right on stage, they usually do not look at the audience.

Acceptance of a behavioral or natural state of affairs; participants tend to avoid movements reminiscent of traditional dance techniques and make no distinction between everyday and dance moves. They straighten their clothes, laugh, cough, comb their hair, if necessary, right on stage, they usually do not look at the audience.

In simple exercises, the group can work as a whole. The group can meet from twice a week for one or two hours, up to five times a week for four hours. One meeting a week is the minimum for group cohesion to develop. More regular sessions are, of course, better for the progress of each of the participants. The facilitator is responsible for determining the purpose of the sessions as a whole and for each individual meeting. The facilitator can determine how best to present the task to the group, how to acquire movement, composition and performance skills, how to organize group improvisation.

In simple exercises, the group can work as a whole. The group can meet from twice a week for one or two hours, up to five times a week for four hours. One meeting a week is the minimum for group cohesion to develop. More regular sessions are, of course, better for the progress of each of the participants. The facilitator is responsible for determining the purpose of the sessions as a whole and for each individual meeting. The facilitator can determine how best to present the task to the group, how to acquire movement, composition and performance skills, how to organize group improvisation.

Once the overall direction of the exercise for the session is chosen, it is important to be flexible in following this plan. The facilitator needs to be responsive to each participant, and the participants to each other. The facilitator decides when to interrupt the exercise and when to repeat.

Once the overall direction of the exercise for the session is chosen, it is important to be flexible in following this plan. The facilitator needs to be responsive to each participant, and the participants to each other. The facilitator decides when to interrupt the exercise and when to repeat.  In addition, the host may also announce the end; hint that it is time for the participants to finish, or allow them to finish at the moment they see fit. Participants can imagine that the light is dimming and continue moving towards the outer edges of the space. Or they may leave the stage space.

In addition, the host may also announce the end; hint that it is time for the participants to finish, or allow them to finish at the moment they see fit. Participants can imagine that the light is dimming and continue moving towards the outer edges of the space. Or they may leave the stage space.  They must be able to react to what they see. Having mastered this, participants can acquire new skills and combine them in their dance. When working with a group, the findings themselves are less important than the ability to use them with other people. It starts with an interest in working together and a sense of trust in the other members of the group.

They must be able to react to what they see. Having mastered this, participants can acquire new skills and combine them in their dance. When working with a group, the findings themselves are less important than the ability to use them with other people. It starts with an interest in working together and a sense of trust in the other members of the group.  su All materials presented on the site are for informational purposes only and do not pursue commercial purposes or copyright infringement. Feedback - 176.57.188.101 (0.004 s.)

su All materials presented on the site are for informational purposes only and do not pursue commercial purposes or copyright infringement. Feedback - 176.57.188.101 (0.004 s.)