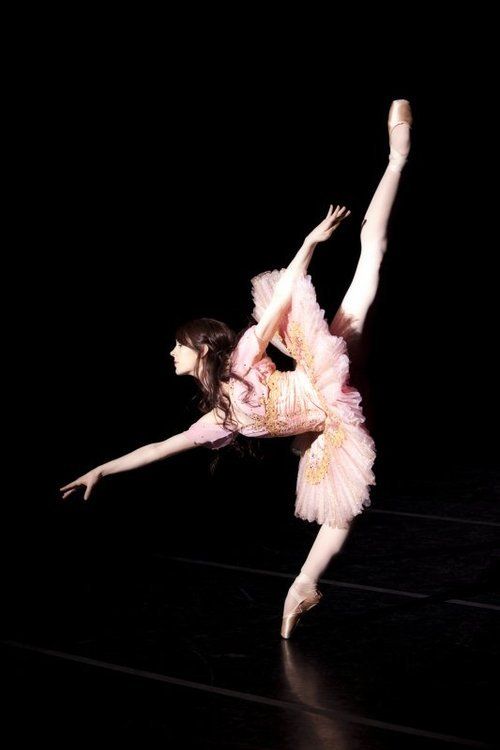

How to choreograph a ballet dance

10 Tips From the Pros

Creating movement from scratch to encompass the feeling, rhythm, and theme of a song takes a little imagination and some work, whether you're a beginner or getting ready for a big performance. When you're including the movements and dance phrases for multiple performers, too, choreographing a dance can get quite complicated. That's why we're giving you some top pro tips on how to choreograph a dance when you're feeling stuck, including methods you can use to step outside the box and spice up your routine.

1. Study the Music

If you know what music you want to choreograph your dance to, start studying. Go beyond creating movements based on the rhythm and beat of the song, and study the lyrics, the emotion, and the meaning behind the song. You can find inspiration from the feelings you get when you read the words, and embrace the emotion the artist puts into the song.

Poppin' C, a Swiss popping dancer, says, "The music is everything for me, because the way my body adapts and moves, is because of the way I feel the music. " By knowing every part of your music inside and out, you can design dance moves that really work with the beat and lyrics.

B-boy Junior holds a breaking workshop at Red Bull BC One Camp in Mumbai

© Ali Bharmal / Red Bull Content Pool

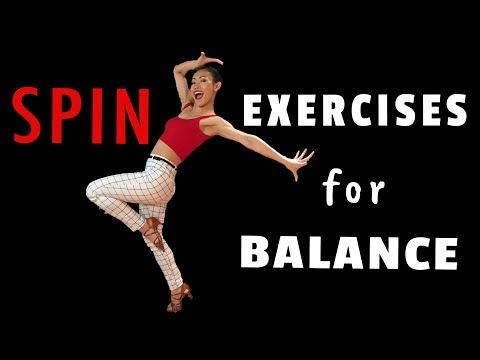

2. Watch the Pros

Take some time to watch dance-heavy musicals, like "Chicago" and "Anything Goes," competitive series like "World of Dance," and even street performers, like Logistx, to grab some inspiration for your moves. Observe the styles, transitions, and combinations of movements and note how pro dancers create a physical connection to the music. This can help motivate you to create dances that get the audience to connect with your physical interpretations of the music.

3. Plan for Audience and Venue

Think about who your performance or event is for. Consider the venue you're performing at, too, because your dance environment can help you find ways to creatively express emotion. Lighting, sound, and the overall ambiance of your venue can help you design dances that incorporate mood and emotion to connect with the audience during your performance.

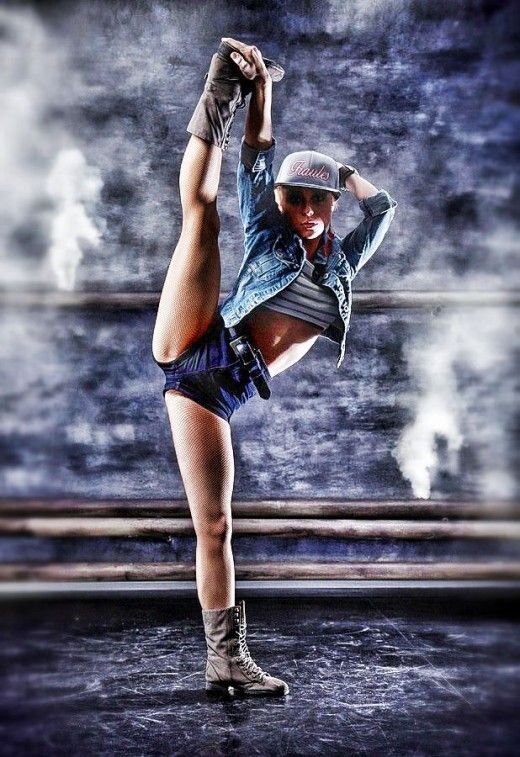

4. Think About Dance Style

Choreograph with steps and dance moves that reflect a specific style. You might try incorporating hip hop steps into a classical dance to mix it up and create your own unique dance style, for example. If you're just starting out with dance choreography, try focusing on learning how to balance a specific style of dance with your unique interpretation of the music you're dancing to.

Kid David poses for a portrait at Red Bull Dance Your Style USA Finals

© Carlo Cruz/Red Bull Content Pool

5. Focus on the Basic Elements

Focus on one (or several) of the most basic elements of dance: shape, form, space, time, and energy. For form, you can focus on designing phrases and steps based on a specific form from nature, like an animal or landform. Use your stage space to showcase explosive energy and give certain aspects of your performance a punch of emotion that keeps your audience engaged.

6. Don't Start at the Beginning

If you're stuck trying to figure out how to start your dance, plan it out from the middle or from the end. Tell a story through your dance choreography and plan out the climatic elements before the small steps to help you flesh out where you want to go with your ideas. Once you've outlined the basic structure of your choreography, piece it together into an entire work.

Tell a story through your dance choreography and plan out the climatic elements before the small steps to help you flesh out where you want to go with your ideas. Once you've outlined the basic structure of your choreography, piece it together into an entire work.

7. Try Choreographing Without Music

Dance in silence. It might seem like a crazy idea since you're choreographing the dance to a specific song. However, just letting your body move and flow with different tunes you imagine can help you step outside your comfort zone and incorporate challenging moves and dance steps that you might not have thought to pair with a song or score. When you discover something you like, pair it with other steps you've already developed and start fitting your moves to the music.

Poppin C shows off his moves during a photoshoot in Lausanne

© Torvioll Jashari / Red Bull Content Pool

8. Embrace Post-Modernism

Study early modern dance forms and styles that can get your imagination flowing. Dancers from the mid-century modern era through the 1950s and '60s (such as Anna Halprin, one of post-modern dance's pioneers) would incorporate a whole world of nontraditional moves in their choreography. Slow walking, vocals, and even common gestures can make imaginative additions to your overall work.

Dancers from the mid-century modern era through the 1950s and '60s (such as Anna Halprin, one of post-modern dance's pioneers) would incorporate a whole world of nontraditional moves in their choreography. Slow walking, vocals, and even common gestures can make imaginative additions to your overall work.

9. Incorporate the Classics

Use classical ballet, traditional ballroom steps, or other classic dance moves to mix up your style. It can be a startling transition for an audience to see a classical ballet step snapped in between freestyle phrases. Combining classical techniques with your dance design can add interest and suspense to your performances.

10. Use Other Art Forms as Inspiration

Don't just focus on music and dance. Look at all kinds of art forms, from two-dimensional paintings to live art performances. Take note of the different emotions and use of space, shapes, and forms that different artworks incorporate, and think about your interpretations and how you can convey that in movement. Use this as fuel for your inspiration when choreographing short phrases. Keep up to date on new forms of art to get inspired and avoid the dreaded writer's block (for dancers).

Use this as fuel for your inspiration when choreographing short phrases. Keep up to date on new forms of art to get inspired and avoid the dreaded writer's block (for dancers).

More Pro Tips to Choreograph a Dance

Arlene Phillips CBE, a British choreographer and theater director, got her start pro dancing and choreographing in the 1970s. She's been the choreographer for a variety of performances over the years, including live theater. Her advice for aspiring dancers includes some helpful choreographing tips:

Tell the music's story through your movements

Keep practicing with imaginative steps

Be determined to learn from your mistakes

Challenge yourself with unique rhythms, styles, and techniques

Plan out your most impactful elements then work in additional steps around those

Keep practicing your choreographing techniques

Don't be afraid to learn something new

One of the most important things to keep in mind when choreographing a dance, though, is to embrace diversity. Don't be afraid to do something different or outside the norm. Try incorporating new styles or steps to make your dance fresh, and study all types of art to get excited about your work. The more you challenge yourself to think outside the box, the more creative and unique you can be with your choreography.

Don't be afraid to do something different or outside the norm. Try incorporating new styles or steps to make your dance fresh, and study all types of art to get excited about your work. The more you challenge yourself to think outside the box, the more creative and unique you can be with your choreography.

Basic Guidelines of Choreography for Ballet

When you decide to choreograph your own ballet dances, you have complete freedom of expression for your choreography. And that's as it should be. But artists of all kinds have found that they flourish best when they voluntarily submit to certain limitations. The series of ballet gestures, for example, is a "limitation" that somehow sets the imaginations of the great ballet choreographers free.

The ideas in the following sections, culled from centuries of great choreography, give you a framework for your freedom, a vehicle for your own artistic vision. All forms of expression are valid — but these ideas can help you get started successfully.

Finding your inspiration — music or theme

What makes a choreographer want to create a particular dance in the first place? Most choreographers say that they are usually inspired by one of two things: the music or the theme.

When you hear a certain piece of music, are you swept away in an ecstatic whirlwind? Do colors and shapes and movements immediately suggest themselves to you? Are you lost in time and space? If so, we know a good doctor who can help. But failing that, the piece sounds like a good candidate for choreography.

If there's one basic rule of choreography, it's this: The gestures should somehow reflect the music. What sets the successful choreographers apart is that their gestures embody the music beautifully, as if each musical phrase had been written just for them.

An example most people can visualize is the dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy from The Nutcracker. As the celesta begins to play its tinkly tones, the ballerina dances nimble, delicate little steps, seeming to flit across the stage. Although different choreographers may have set different steps to this music over the years, nearly all of them have tried to create something appropriately delicate.

Although different choreographers may have set different steps to this music over the years, nearly all of them have tried to create something appropriately delicate.

You might like to know that in the professional world, every single minute of dance onstage is the result of approximately two hours of choreography and rehearsal. But hey, don't let that stop you.

Another form of inspiration is the need to tell a story. Storytelling is one of our oldest pastimes, and dance has always come in handy for that purpose. Does a certain story call out to you, just needing to be expressed somehow? Then why not make that the basis for a dance?

When telling a story in dance, first decide whether you want to create a simple narrative from beginning to end, or something more complex.

Say, for example, that your theme is the story of Hansel and Gretel. Just think of all the ways you could tell that story. You could opt for the linear approach, showing Hansel and Gretel wandering through the forest, dropping breadcrumbs, getting lost, happening upon a candy house, and getting fattened up. Or you could start at the end of the story, with the kids leaping breathlessly onstage to tell you what they just experienced.

Or you could start at the end of the story, with the kids leaping breathlessly onstage to tell you what they just experienced.

Or, your dance could simply focus on character at one point in a story. How does the wicked witch feel when the kids bake her alive? Maybe she could do an interpretive dance to let us know. This expression of one instant in time, telescoped out to show the emotional weight it contains, is the basis for 99 percent of all poems, operatic arias, and popular songs — and it works for dance as well.

Knowing how you want the choreography to look

Great choreographers almost always talk about their "vision" of their work. Choreographers are proud of their visions and will tell you about them until you ask them to stop.

Quite literally, choreographers create an image of the dance in their minds before attacking the nitty-gritty of the choreography. Whether or not they envision the actual steps at first, they can imagine the overall "look" of the piece. From there, they can begin to choose the steps that best fit that vision.

From there, they can begin to choose the steps that best fit that vision.

The vision can include costumes, set, and lighting designs — although in the professional world, special designers are hired to flesh out the details of this portion of the vision.

Working from this internal vision, choreographers then write down their ideas using dance notation — or simply dance it themselves on videotape.

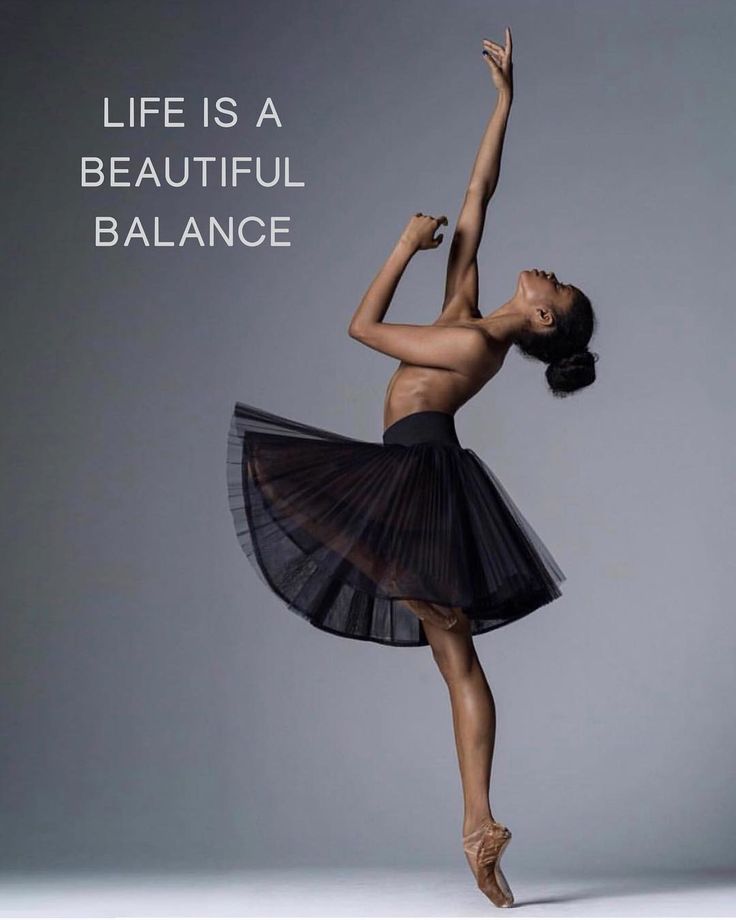

Developing a vocabulary for the dance

The same basic step can be danced in many different ways. So when you choreograph a piece, you have a nearly infinite number of steps to choose from. The vocabulary of the dance refers to the particular gestures and movements that you choose to use — the ones that seem to reflect your own character and make up your personal style.

The order in which you put the steps is important, too. The steps should seem to flow from one to the next. For example, an arabesque looks good when followed by a failli. But it looks bad followed by a backflip. You just feel these things.

But it looks bad followed by a backflip. You just feel these things.

After you begin to experiment with various sequences, you're likely to find some that feel just right for you. When that happens, you can repeat those sequences again and again — thereby creating a vocabulary that you can call your own. George Balanchine, for example, was famous for following a sauté in arabesque with a jeté. That was his trademark — just as Bob Fosse made a name for himself with bowler hats and turned-in legs (also known as pigeon toes — think Cabaret).

Using your full dance space

Here's another useful rule for choreographing your own work: Use the full amount of space that's available. By the end of the dance, every area of the stage should have been stepped on at least once.

You should even consider using non-traditional areas — where you'd never think of dancing. Staircases, hallways, railings, and other levels of flooring come to mind. (Or puddles — as Gene Kelly discovered in Singin' in the Rain.) The unexpected is often where the most inspiration lies.

(Or puddles — as Gene Kelly discovered in Singin' in the Rain.) The unexpected is often where the most inspiration lies.

When covering your space, we suggest varying the shape of your dance. If you begin with a move on a diagonal; then try adding a circular pattern later. Or vice versa. Stretch your imagination — and keep your audience on their toes.

Ending the dance as you began

One way to make a dance feel artistically whole is to "come full circle." And one way to accomplish this is by starting and ending the dance with the very same pose.

An even more advanced version of this technique is to end in a slightly "evolved" version of the starting position. For example, if the dance is a duet, consider switching the parts at the end, so that the woman ends up as the man began, and vice versa.

This technique gives the dance a feeling of completion, and it can sometimes be quite poignant and moving. Who knows — you may have your audience in tears. In a good way.

In a good way.

How a ballet performance is created

Creative tasks:

1. What great Russian ballerinas and dancers do you know?

2. Try to imagine yourself as a choreographer and compose a small ballet scenario based on the plot of your favorite fairy tale. You don’t need to invent special signs, just write in words where and what kind of dance these or those characters dance and everything that you can say about the action of your ballet.

Write, draw, compose!

Questions may seem difficult, so we suggest that they be the subject of a family discussion. If you turn to a gentleman named Internet for help, remember: the information received from it often needs additional verification or clarification.

Sign your drawings, give your age and phone number, and don't forget to bring your work with you to the next meeting. Prizes await the participants of the quiz at the last meeting of the Academy of Young Theatergoers.

Answers and drawings can be sent by e-mail to: [email protected] or [email protected]

Special prizes await active users.

Script writer and presenter - Natalia Entelis

Director - Alexander Maskalin

Production Designer – Sergei Grachev

Lighting designer – Roman Peskov

Choreographer – Dmitry Korneev

There is a special world in the theater where they don't speak or sing. This is the mysterious and alluring world of dance.

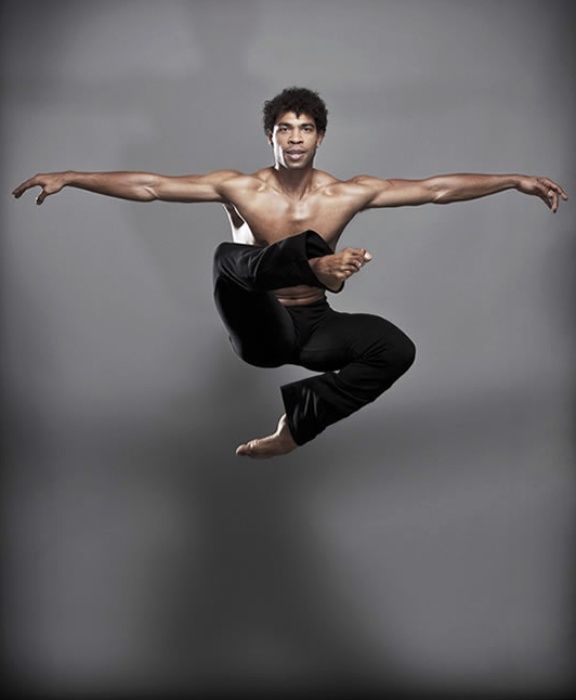

Becoming a dancer is very difficult, because grace and ease of movement is achieved through hard work. Future dancers start training very early - at 7-8 years old, and then they practice for many years, for many hours a day.

But not only professional artists can dance, but also any person. Remove dancing from our lives, and how much less fun and joy will become - everyone loves to dance! And whoever says he doesn't love, he probably just hasn't learned yet. In ancient times, everyone had to be able to dance. Noble families invited a home dance teacher to their children before going to the ball. The teacher was especially worried - after all, not everyone is talented!

In ancient times, everyone had to be able to dance. Noble families invited a home dance teacher to their children before going to the ball. The teacher was especially worried - after all, not everyone is talented!

Everyone knew how to dance, but some did it especially competently and gracefully - and were proud of it. King Louis XIV of France did not consider it below his dignity to dance in front of the courtiers, demonstrating his skills. Is that how ballet came about? No not like this! Ballet only then became a real art when it learned to tell different stories. Without words, but with music. In order to tell fairy tales and stories to the music, a special language was invented in ballet, the language of dance, the language of gesture.

Once the famous dancer Maris Liepa danced the role of Prince Lemon in the ballet "Cipollino" based on the fairy tale by Gianni Rodari. One of the little spectators who was present at the performance explained to his mother: “Prince Lemon said that Cipollino must be caught. ” He understood the language of ballet without words, and yet the ballet dancer does not say anything, he only dances and uses gestures!

” He understood the language of ballet without words, and yet the ballet dancer does not say anything, he only dances and uses gestures!

how to stage a ballet according to the precepts of Susan Sontag

...At one point in the performance, a huge shiny CD descends from above, covered with round growths (the sun?). At the same time, the dancer gets into the cage, which rises almost under the grate. A long fabric hangs from the cage, in which the dancer was wrapped and painted with spray paints earlier in the scene. Sound-extracting mechanisms are attached to her arms, which amplify and change the sound whenever the heroine hits her hands on the edges of the cage. Loose hair covers her face, in the manner of a girl from the movie "The Ring". At the same time, on the right side of the stage, a dancer wriggles, entangled like a puppet in countless multi-colored thread-ribbons (they are attached at one end to the cage above). On the proscenium, another dancer synchronously repeats his movements . ..

..

Susan Sontag, a cult American thinker and intellectual, has an article - Notes on Camp.

In it, Sontag, in 58 short statements, considers the phenomenon of camp - an exaggeratedly theatrical, absolutely apolitical and extravagantly non-gender, purely aesthetic perception of art, without moralizing and tragedy, but with an excess of beauty and with a serious attitude to this excess.

With some limitations, Back to life is a variation on the camp theme.

“REINcarnation, Distortion, Theatricality”*

(*hereinafter the headings are quotations from Notes on Camp)

A fragment of the new play that I have described above is the most characteristic example of theatricality, but besides this:

Boy with violin and sewing machine. Glowing frames of cubes and houses. Pointe dancers in the foyer demonstrate the clothes of young Volga designers. The orchestra is divided into parts, scattered around the corners of the stage and dressed in theatrical costumes; the conductor directs the characters. A dancer in tiger pointe shoes turns pirouettes and shows a rock goat. And defile, defile, defile.

A dancer in tiger pointe shoes turns pirouettes and shows a rock goat. And defile, defile, defile.

Rust-eaten curtain opens up the stage area without backstage with a high screen on the back. There is a cruciform podium on the stage. To the right of the proscenium is a harp, to the left is a piano. Throughout the performance, the musicians go to the harp or piano, perform the desired episode and disappear, only to come out again.

Also: several mannequins and their parts, cuttings and tears of fabrics, sewing accessories. In the first act, huge bullets hang from the poles, in the second act they are replaced by huge multi-colored spools of thread. Duets and solos on the stage alternate with mass dance runs, which in turn turn into ensemble dances in all possible musical dance genres.

“NEGLECTS CONTENT”

Zarenkov’s short story “Return to Life” (a woman who becomes an inveterate drunkard after losing her husband and son in a car accident, gets a chance to return to normal life and embodies the dream of her youth - becomes a fashion designer), is only an impetus for the librettist’s fantasy and a choreographer, and intersects with the narrative of the play in a tangent way: there remains only a hint of the main theme - fashion, sewing, haute couture, and the main character - a woman going to recognition through suffering. Both without realistic details, but with a lot of scenographic and dance details.

Both without realistic details, but with a lot of scenographic and dance details.

The main character remains at the center of the story, but the characters of the husband and son (they are only mentioned) appear in the play, and the main rescuer present in the story, on the contrary, disappears.

In addition to the storyline of the Mother (as the main character is designated in the libretto), there is a side storyline of love between the Couturier and the Model (either the alter ego of the main character, or her memories), this is not in the story at all. Already at the level of the list of characters, the narrative changes beyond recognition. Psychologization, on the other hand, in Zarenkov's short story, and previously reduced to a minimum, completely disappears in the performance, transforming, exactly according to Sontag's precepts, into an exaggerated theatricalization of a gesture, emotion, object. "Vital" is replaced by "beautiful".

If choreographers choose a plot basis for their productions, then, as a rule, it is "great literature" ("Anna Karenina", "Romeo and Juliet", "The Lady of the Camellias", etc.). In the process of creation, they are forced to abandon side lines, secondary characters, important details, etc., that is, they follow the path of shortening the narrative, concentrating on choreography. Smekalov, on the other hand, does not want to give up either the narrative, or the choreography, or anything else.

Taking a short story devoid of details, he expanded it to the maximum and, in fact, based on a small literary form, composed a ballet-novel (and it does not matter that it is choreographically and scenographically eloquent exactly as much as the story is the basis).

“CLOTHES, TEXTURE, STYLE –

TO COVER THE COSTS OF MAINTENANCE”

Smekalov interprets the word couture, which is part of the genre definition of the performance — ballet couture — as nothing more than just “sewing”.

And although the concept of couture implies both a trend and high fashion, the choreographer stops only to show the viewer a dance interpretation of the movement of the needle and sewing stitches.

Nevertheless, the corps de ballet, practically not included in the narrative, nevertheless received its dose of fame in the form of numerous dressing up in the author's individual costumes (costume designer Sergey Illarionov).

"CAMP SEES EVERYTHING IN QUOTATION MARKS"

The choreography in this performance is both excessive and secondary, as it is not sad to admit. But the most important thing is that it all consists of quotes and stylization. The choreographer, desperate to look modern and relevant, included in solo and duet pieces quotes from Kilian, Ek, Forsythe, in a word, everyone he saw and could reach.

The image of the main character refers to Ek's writings on Guillem: the heroine in a pale blue floor-length dress is absurdly braided in elongated arms and legs. Anastasia Tetchenko opened up brilliantly in this game. She really looked like a real diva of her theater: beautiful, who did not wait for the applause of the main theaters of the world, but she does not need it, she is the star here.

Anastasia Tetchenko opened up brilliantly in this game. She really looked like a real diva of her theater: beautiful, who did not wait for the applause of the main theaters of the world, but she does not need it, she is the star here.

The choreographer uses the citation technique for obvious reasons: he can hardly compose any lengthy choreographic text (or considers it unnecessary) and is limited to constantly repeated leitmotifs. Thus, the movement of the main character, which by the end becomes the iconic refrain of the entire performance - the hand to the right shoulder, to the left and up - apparently symbolizes the faith of the heroine, which helped her climb to success in life. The sign of the cross in a savvy way.

SERIOUS UP TO FAILURE

Easily and confidently, Smekalov complicates the concept of the production as much as possible. A very simple everyday story is overgrown with truly apocalyptic details. Four heralds of the apocalypse (four dancers dressed in black and red) surround the heroine at the darkest moment of her fate. And seven other fellow travelers are master artisans, with each of whom she performs a small dance duet (Jewish folk motifs, waltz, tango, foxtrot, etc.) despite the lively and quite bright mood of this episode - the seven sins of the heroine. Horsemen of the Apocalypse, deadly sins, the sign of the cross - the author is very serious.

And seven other fellow travelers are master artisans, with each of whom she performs a small dance duet (Jewish folk motifs, waltz, tango, foxtrot, etc.) despite the lively and quite bright mood of this episode - the seven sins of the heroine. Horsemen of the Apocalypse, deadly sins, the sign of the cross - the author is very serious.

"PURE CAMP IS ALWAYS NAIVE"

The naive seriousness with which the creators treat their work cannot but bribe. And the audience of the Samara Opera and Ballet Theater gladly responded to the invitation to attend the theatrical defile. The premiere performances were held, albeit with a limited occupancy of the hall, but with a huge audience response. Dozens of stories on Instagram from a fashion show in the main theater of the region, fashionable, smart and happy spectators and artists - Smekalov's performance has become a real cultural event, and there is no doubt that it will be very popular. Which proves once again: in the postmodern world, we see everything through the prism of camp and fly like butterflies into the light of lush, pretentious excess, to the celebration of life and beauty.