How to armenian dance

“One, Two, Three; Step, Swing” Armenian Dance Across Generations

I am toddling in the dance line, holding tightly to the hands of my grandmother and grandfather. It’s after a Sunday dinner, and we are dancing to Armenian tunes played on the phonograph in my living room. My grandparents were from the provinces of Kharpert, Cesaria, and Sepastia in the historic Armenian lands of Anatolia, and they brought with them the dance styles of their towns in the “old country.”

To me, Armenian dancing evokes memories of good food and a loving family.

As a cultural educator and a dancer trained in various forms, I am curious about this history and evolution of Armenian dance traditions. Over the centuries of invasion, the destruction of much of our material culture has made it difficult to study Armenian dance historically. Dance traditions are often ephemeral, particularly ethnic dance forms of refugees and ethnic minorities. So exploring, discovering, and recovering my ancestral dance tradition is especially rewarding for me.

From the “Old Country”

Program from the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City

Archives of the Armenian Folk Dance Society of New York

There are two distinct styles of dance, “Western Armenian” or Anatolian, and “Eastern Armenian” or Caucasian. (For more on Armenian dance history, read “Dancing Armenian in Anatolia, the Caucasus, and Beyond” on the Festival Blog.) Most Armenian immigrants in the United States in the early twentieth century came from Anatolia, so Armenian American folk dance styles were Anatolian.

One of the first Armenian American dance ensembles was the Armenian Folk Dance Society of New York, formed in 1937 initially to represent Armenia at international festivals in the New York region. Recently, a descendent of one of the members of this group gave me part of their archives as a gift—what a treasure!

Six boxes arrived in the mail filled with yellowing envelopes and albums, smelling of must and old paper. Inside I found their rehearsal and staging notes, photographs, performance flyers, and printed programs. The society collected and performed over twenty-five different regional dances, particularly from Sepastia, Van, and Garin. As a performance-oriented group, they only collected dances that could be presented on stage. Unfortunately, those deemed too boring or simple were ignored and subsequently lost.

Inside I found their rehearsal and staging notes, photographs, performance flyers, and printed programs. The society collected and performed over twenty-five different regional dances, particularly from Sepastia, Van, and Garin. As a performance-oriented group, they only collected dances that could be presented on stage. Unfortunately, those deemed too boring or simple were ignored and subsequently lost.

Across the Ocean

Armenian picnic in Springfield, Massachusetts, c. 2000s.

Photo courtesy of C. Rapkievian

Armenian dancing was always part of my childhood. Every summer, on the weekends, we went to the Armenian picnics held in Maynard, Massachusetts. The Armenians from Kharpert and the Armenians from Caeseria were always trying to outdo each other—who could host the best picnic? There was always the smoky smell of shish kebab cooking, with pilaf, salad, other Armenian treats, and bottles of Fanta. A live band would play on the wooden “band shell” with a paved dance “floor” in front. Families, friends, and acquaintances all danced together.

Families, friends, and acquaintances all danced together.

My parents met at one of the Armenian formal dances they attended as young adults in the 1940s and 1950s in Boston, Hartford, and New York. Some of the dances were held jointly with the Greek American community. “We learned their dances,” my mother noted. At intergenerational dance parties today, older Armenian bands will still play the Greek tunes (Miserloo, Tsamiko, and sometimes a Kalamatiano), and many of the older generations still dance them or the Armenian adaptations. In other cities, both in the United States and the old country, Armenians shared dances with neighboring cultures, such as Laz Bar (a Black Sea dance), Sheikhani (similar to an Assyrian dance), and the Michigan Hop (similar to a Bulgarian dance).

Growing up, I attended Armenian dances in the Boston area with my younger cousins and learned the current repertoire of Armenian American party dances. Some were the old village styles, but most of them were adapted by Armenian American youth.

An Armenian divinity student teaches a folkdance to local children at the Tatev Monastery in Armenia, 2016.

Photo courtesy of C. Rapkievian

Years later, on a trip to Armenia with Smithsonian colleagues, we happened upon a children’s dance lesson in the courtyard of an ancient monastery. I recognized the dance and, at the urging of my colleagues, joined the circle. The children were surprised! And I was too—it turns out that their teacher learned Papuri from dance leader Gagik Ganosyan in Armenia, who had learned the dance from Susan Lind-Sinanian from Massachusetts. It was an amazing example of a dance traveling over and back across an ocean.

Across Generations

On my trips to Armenia, I visited and took classes with noted dance leaders, including the legendary Artoush Karapetyan, as well as Gagik Karapetyan, Gagik Ganosyan, and Edik Khachatryan. I also learned their philosophies about teaching Armenian folk dances to youth and young adults. One focused on artistic expression, another on preserving old dances while making them exciting to new generations, and another on providing positive activities for underprivileged children. Every town and village seemed to have a folk dance troupe of some kind. In fact, in 2005, Minister of Culture Hovik Hoveyan complained, “There are too many Armenians dancing”!

One focused on artistic expression, another on preserving old dances while making them exciting to new generations, and another on providing positive activities for underprivileged children. Every town and village seemed to have a folk dance troupe of some kind. In fact, in 2005, Minister of Culture Hovik Hoveyan complained, “There are too many Armenians dancing”!

Artoush Karapetyan teaching at the Pedagogical College in Yerevan Armenia, 2012.

Photo by C. Rapkievian

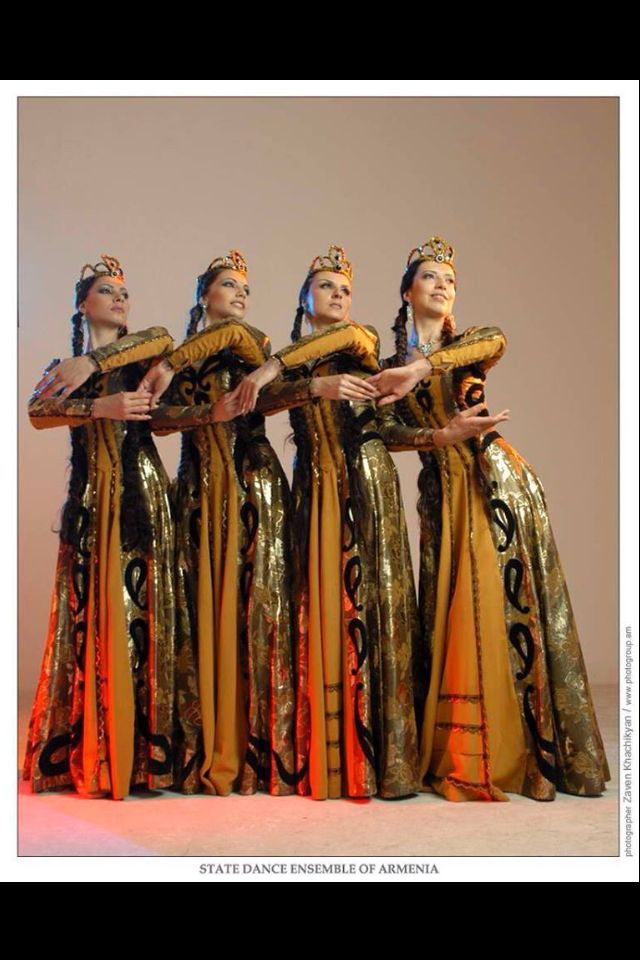

When my son was a baby, I joined the Antranig Armenian Dance Ensemble of New York and New Jersey. For a few months each year, we had the privilege of studying with Gagik Karapetyan, the director of the State Dance Ensemble in Armenia. We performed many of the Caucasian Armenian dances as well as “Gago’s” original choreographies.

My son grew up at the rehearsals, first on my back, later playing and watching the dances, and finally performing in Lincoln Center with other children of ensemble members. By the time he was three years old, he had been to Armenian picnics at Camp Hayastan, eaten Grandma’s good Armenian food, and looked forward to games and dancing with his friends in Antranig, so when I took him to see the ocean for the first time, he exclaimed, “Mommy, this is really Armenian!”

By the time he was three years old, he had been to Armenian picnics at Camp Hayastan, eaten Grandma’s good Armenian food, and looked forward to games and dancing with his friends in Antranig, so when I took him to see the ocean for the first time, he exclaimed, “Mommy, this is really Armenian!”

I was puzzled for a moment, and then I laughed. He thought “Armenian” was an adjective meaning “a good time.”

Across Borders

When I discovered YouTube in 2006 shortly after its inception, I searched for Armenian dance and was astonished to find a group in Dagestan, a Russian republic separated from Armenia by Georgia and Azerbaijan. Shortly after, I found a video of a wonderful Armenian French group doing dances similar to those I had learned in Antranig. I was amazed! Before the era of social media, most Armenian Americans had little knowledge of the existence of diaspora communities worldwide. Now, people around the world can share and adapt regional dance styles.

Maral Armenian Dance Ensemble in Istanbul, Turkey, 2015.

Photo by C. Rapkievian

Most Armenian Americans were told growing up that there were no Armenians living in Turkey. But when I traveled to Istanbul in 2015, I was thrilled to join a dance rehearsal in the inconspicuous Armenian community center. I hoped I would see the dances of my grandparents in their true form, but they too are now doing the dances from the Republic of Armenia.

Here in Washington, D.C., a group of adult dancers called the Arax Armenian Dance Ensemble, named for a river that winds through the old country, performed from 2004 to 2014. As the director, I was always amazed at the composition of the group: some dancers were born in the United States and their grandparents came from Anatolia in 1915, one from Armenia, and the rest from Armenian communities in Canada, France, Russia, Turkey, Cypress, Iran, Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria. It was truly the diaspora reunited! Since their grandparents came from several regions in historic Armenia, we strove to present dances from each members’ place of origin.

In more recent years, as the director of the Arev Armenian Dance Ensemble (arev means “sun”), I have realized that because we seem to be unique in our presentation of Anatolian Armenian dances, we are focusing on preserving and performing these dances. While not as flashy as staged Caucasus dances, we hope to play a vital role in maintaining the diversity of our intangible heritage. And we are excited to do so this summer at Smithsonian Folklife Festival—hope to see you there!

Arev Armenian Dance Ensemble, 2017.

Photo by J. Urban

Carolyn Rapkievian is serving as an Armenian dance advisor for the 2018 Folklife Festival and is assistant director for interpretation and education at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

History of the Armenian Dance

|

Folk Dance Federation of California, South, Inc.

History |

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

ARMENIAN DANCE BEFORE 1915

The Armenian dance heritage has been one of the oldest, richest, and most varied in the Near East. The ancestors of the Armenians established themselves in Hayastan (Armenia) about 650 Before Christ (B.C.) soon after the collapse of the Urartian Empire. The geographic position proved both a curse and a blessing. Located at a major crossroads between powerful empires, Armenia became a buffer state continually ravaged by invading armies, but distant enough to retain its own culture and identity.

The geographic location encouraged commerce and exposed the Armenians to many other peoples: Phrygians, Syrians, Persians, Hellenic Greeks, Romans, Laz, Jews, Byzantines, Arabs, Kurds, Seljuks Mongols, Osmanli, Georgians, Asiatic Albanians, Russians, and countless others. Armenian culture reflects many of these influences.

Armenian culture reflects many of these influences.

Ancient Armenia was a feudal society, with each district ruled by nakharar (feudal lord). these noble houses jealously protected their prerogatives and limited the possibility of national unity. The unruly autonomy of these princely houses also hindered the rule of would-be conquerors. As a result, this ruling class was gradually destroyed by invading armies, to facilitate their own rule. The destruction of the nakharar class also destroyed the "high" culture of the native elite. The only surviving institution was the Armenian Church, which became the dominent political, religious, and social focus of Armenian life. The ecclesiastic orientation of Armenian culture today reflects this phenomena.

Although centuries of Ottoman subjugation changed or destroyed much of Armenia's "Great Tradition" (elite culture), the "little tradition" of the peasantry remained relatively unchanged for millennia. The rich dance heritage remained a living tradition into the 20th century. The Turkish massacres and deportations of 1,500,000 Armenians during world War I, and the subsequent dispersion of the survivors, irrevocably destroyed much of the dance heritage of Western Armenia, leaving scattered fragments of some dances. Many of these surviving fragments have since been lost due to modern cultural assimilation and urbanization.

The rich dance heritage remained a living tradition into the 20th century. The Turkish massacres and deportations of 1,500,000 Armenians during world War I, and the subsequent dispersion of the survivors, irrevocably destroyed much of the dance heritage of Western Armenia, leaving scattered fragments of some dances. Many of these surviving fragments have since been lost due to modern cultural assimilation and urbanization.

The destruction of most of the material culture has made it difficult to study the dance historically. Similarities in the poses found in Armenian dance with poses found in ancient Sumerian and Urartian artifacts have been cited as evidence of a direct relationship. These similarities do suggest the continuity of certain motifs but these motifs are also shared by neighboring ethnic groups. Most of the written records that have survived are ecclesiastically oriented (that is, illuminated manuscripts), and make little mention of the dance. These writers were clerics who viewed the dance as pagan in origin and generally ignored or suppressed it. The references that do exist indicate that many Armenian dances were originally totemic, imitating animals or nature.

The references that do exist indicate that many Armenian dances were originally totemic, imitating animals or nature.

Ancient Armenia

DANCE TYPES

The traditions of many centuries contributed to the development of the rich diversity in Armenian dance. The dance itself is divided into two categories: dances (barer), which were executed to the accompaniment of musical instruments, and song-dances (bari-yerker), which were performed to vocal accompaniment.

Dances were usually accompanied by musical instruments. In the village, the most common instruments were davul / tahul (a large drum), and zourna (primitive oboe). Other popular village instruments used were dudek sheeve and mey (shepherd's flutes), and daf (tambourine). The sax was a stringed instrument commonly played in Western Armenia, with the tar being its Eastern Armenian counterpart. The kemenche (fiddle) was used as a folk instrument on the Black Sea, but elsewhere was used to accompany the songs and poetry of the wandering ashoog (troubadour). A village ensemble often consisted of no more than two or three instruments.

The kemenche (fiddle) was used as a folk instrument on the Black Sea, but elsewhere was used to accompany the songs and poetry of the wandering ashoog (troubadour). A village ensemble often consisted of no more than two or three instruments.

In the cities, a more elaborate tradition of musical performance existed, with groups of musicians playing in orchestras. These musicians often played tar, oud, kanoon, snatur, nagar, kemenche, daf, dumbeg, and mandolin, or (starting in the 19th century) clarinet, piano, violin, and other European instruments. The music of urban ensembles was heavily influenced by urban "oriental" (Arabic, Persian, and Turkish) music.

These urban musicians considered Armenian village music to be "peasant' and "unsophisticated," and preferred playing Ottoman urban music (that is, longa, simai) and European music. The urban dances reflected this preference (that is, chifte-telli, waltz, quadrille). It was essential for a rural or urban band to have a good singer or skilled joke-teller, who could create impromptu lyrics. Improvisation was an intrinsic part of Armenian culture.

It was essential for a rural or urban band to have a good singer or skilled joke-teller, who could create impromptu lyrics. Improvisation was an intrinsic part of Armenian culture.

Song-dances were performed as the dances provided their own music by singing as they danced. Each village had its own special songs, and its dances that corresponded to the songs. The barbashi (dance leader) would often have his back to the direction that the line was traveling because he would be facing and singing to the other dancers in the line. The barbashi would sing a line or stanza and the rest of the line would respond by either repeating the same lyrics or replying with a different set of lyrics (the type of response varied regionally). The steps of the dance were kept very simple so that one could easily sing and dance simultaneously. Because of this interrelationship of steps and lyrics the dances were never boring, no matter how repetitious the steps, and the dance's tempo and mood were easily varied by the leader.

Some of these songs were ancient but many were improvised ditties reflecting the issues of the day (that is, the local gossip), and changed frequently. The lyrics themselves were not only in Armenian but also in Kurdish, Turkish, Azerbaijani, Greek, etcetera. In many areas of Armenia, these other languages were commonly used by Armenians, often in addition to their own Armenian language. Armenians often composed songs in these other languages or adopted songs created by these neighboring ethnic groups.

While the dancers danced to instrumental music of dance-songs, the spectators would always clap for the accompaniment. This clapping was considered an intrinsic part of any dance. Women were expected to keep their eyes modestly downcast while dancing. This custom prompted the men to cajole them, crying "zhabid" ("smile"), to tease them into ignoring the proprieties.

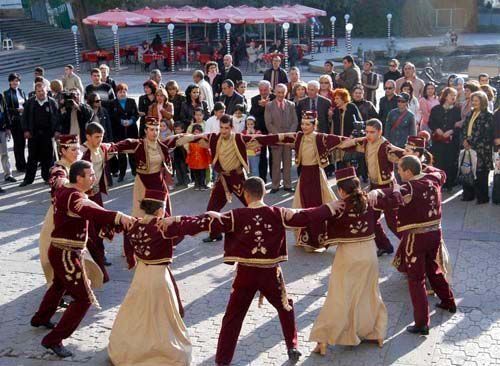

Armenian dance has a wide variety of formations. The dances are often performed in an open circle, with the little fingers interlocked. In general, the dances moved to the right (counter-clockwise), although there are a few areas that moved clockwise to the left (that is, Yerzinga). The basic structure of the dance could be either men only, women only, or mixed lines. The number of dancers also varied: group/line/circle dances, solo dances, or couple dances. In rural Western Armenia, the couple dances were commonly done by members of the same sex (that is, Women's duet from Chamokhlu, men's combat dances). A man and woman dancing together as a couple was more typical of the urban areas, or Eastern Armenia.

In general, the dances moved to the right (counter-clockwise), although there are a few areas that moved clockwise to the left (that is, Yerzinga). The basic structure of the dance could be either men only, women only, or mixed lines. The number of dancers also varied: group/line/circle dances, solo dances, or couple dances. In rural Western Armenia, the couple dances were commonly done by members of the same sex (that is, Women's duet from Chamokhlu, men's combat dances). A man and woman dancing together as a couple was more typical of the urban areas, or Eastern Armenia.

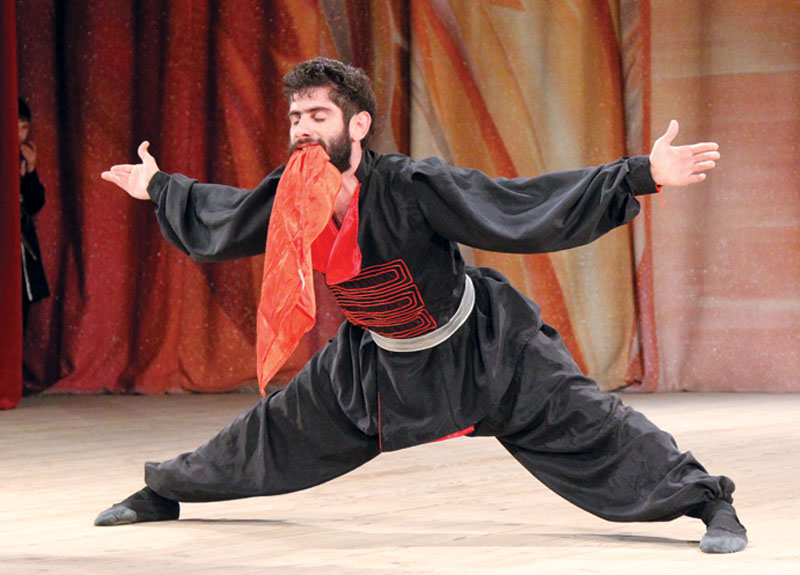

Armenian dance could also be broken down into two distinct styles of dance, "Western Armenian" (Anatolian), and "Eastern Armenian" (Caucasian). These two major styles are also subdivided into regional styles (that is, Van, Lori). Eastern Armenian, the style of the Transcaucasus Mountains, displays ballet-like movements and acrobatics in its oirginal folk form, particularly the men's dances. This is the style usually performed by most Armenian dance groups today, who are influenced by the repertoire of the State Dance Ensemble of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (S.S.R.).

This is the style usually performed by most Armenian dance groups today, who are influenced by the repertoire of the State Dance Ensemble of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (S.S.R.).

Western Armenian is the native style of most of the original Armenian immigrants in America, who settled here after the destruction of Western Armenia. The Western style is far less flamboyant, with little of the leaps or bold gestures that characterize the Eastern style. Western Armenian dance is noted for its heavy earthy movements, and stamping in the men's dances. However, the Western Armenian style is far less dramatic than the Eastern Armenian, and consequently is rarely performed by stage groups, or seen by the public.

THE ROLE OF DANCE

The modern concept of a dance/party (hantess/kef), as a distinct social function with a band playing, etcetera, is an Armenian-American innovation, and did not exist traditionally. A party was not a separate function in itself, but merely one aspect of some major event or festivity which included the entire community (that is, a wedding). There were European balls in the cities for the urban Armenian merchant classes, but these had little in common with the village festivals. A poor villager did not have a band conveniently playing when he wanted to dance, nor did he need one, for he could provide his own music by singing a dance-song. The traditional village dances varied widely and encompassed all aspects of village life. The dance was not simply and idle amusement, but and organic part of the culture. Any event, such as an engagement, would include special music, songs, and dance.

A party was not a separate function in itself, but merely one aspect of some major event or festivity which included the entire community (that is, a wedding). There were European balls in the cities for the urban Armenian merchant classes, but these had little in common with the village festivals. A poor villager did not have a band conveniently playing when he wanted to dance, nor did he need one, for he could provide his own music by singing a dance-song. The traditional village dances varied widely and encompassed all aspects of village life. The dance was not simply and idle amusement, but and organic part of the culture. Any event, such as an engagement, would include special music, songs, and dance.

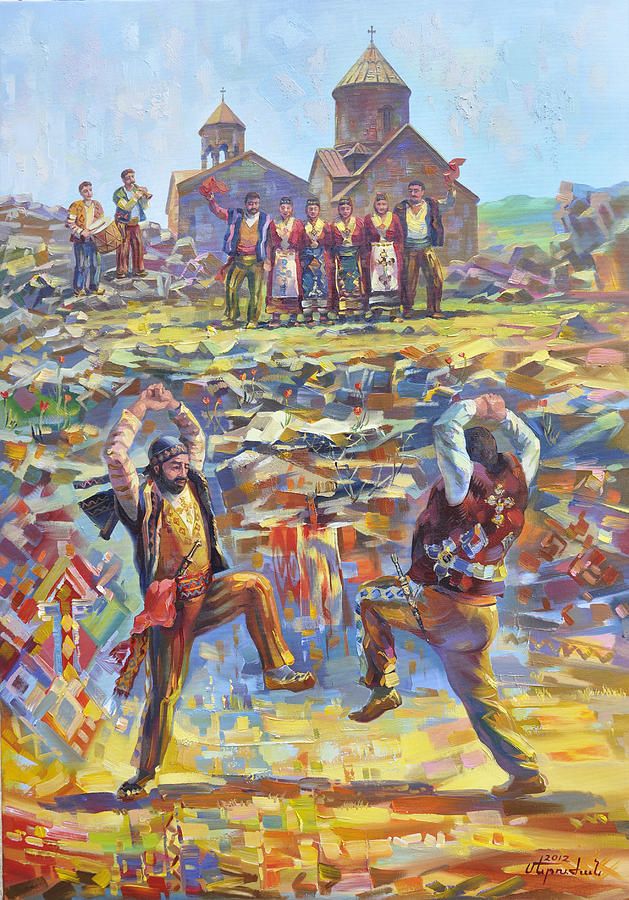

A dance often combined several functions simultaneously. The following description illustrates the multiple roles. It describes Armenian pilgrims dancing at an Ascension Day festival in the Armenian monastery on the outskirts of Treibizond. International folk dancers familiar with Pontic Greek dancing or Turkish Black Sea dancing will recognize this as the Armenian cognate form.

"Soon the villagers came, and the musicians with their bagpipes and drums davous zourna and their kemenchas, native fiddles played upside down. The men wore Lax garb: tight black jackets with long sleeves and two decorative cartridge pockets across the breast; black breeches very roomy in the seat and glove tight at the legs; a black cloth hood knotted smartly around the head with its two ends flapping on the shoulders; cowhide moccasins or heelless shoes with toes ending in a leather thong turned backward.

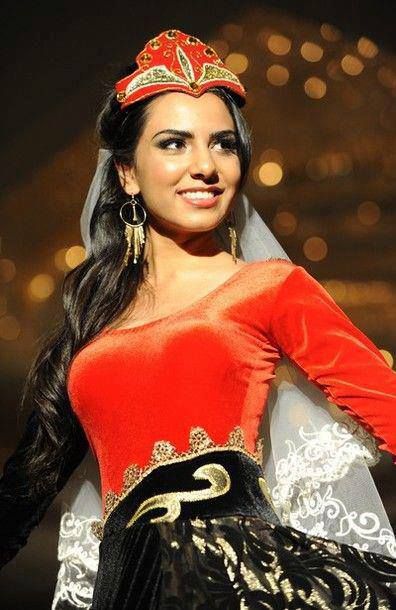

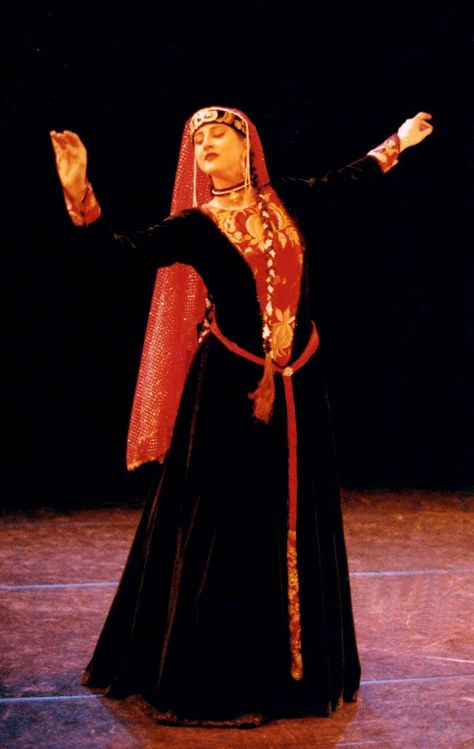

The village women sported gorgeous costumes. Their skirts rustled as they moved, and their red or blue velvet jackets, embroidered with gold or silver thread, fitted tightly around their sumptuous breasts. Gold coins were strung around their disk-like red velvet caps (part of their dowery), and silver buckles shone on their red velvet shoes.

As our peasants danced, the village virgins stood coyly on display and the young men picked and wooed their future wives..jpg) Men and women danced in a circle, hand in hand round and round, forward and backward, the basic circular dance of the Near East and the Balkans. The village men had martial dances of their own. They formed a closed circle, interlocking little fingers and raising their hands above their heads. With a warlike cry "Alashagah they dropped or crouched together on one knee; then jumped up and came down again on the other knee, every muscle in their lithe strong bodies quivering with tension."

Men and women danced in a circle, hand in hand round and round, forward and backward, the basic circular dance of the Near East and the Balkans. The village men had martial dances of their own. They formed a closed circle, interlocking little fingers and raising their hands above their heads. With a warlike cry "Alashagah they dropped or crouched together on one knee; then jumped up and came down again on the other knee, every muscle in their lithe strong bodies quivering with tension."

Leon Surmelian, Apples of Immortality. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1968, page 29.

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE

Armenia had a multiplicity of distinctive regional subcultures, many of which had their own characteristic dialects and customs, including dances. The extensive mountain ranges isolated villages and encouraged variety. The Armenian peasantry was noted for its improvisational skill in songs and dances, often creating new songs and dances to commemorate particular occasions and noteworthy local events (that is, Papertzi Gossip Dance). As time passed these topical songs would be forgotten, as new events inspired new songs and dances.

As time passed these topical songs would be forgotten, as new events inspired new songs and dances.

The same geographic isolation that encouraged diversity also maintained continuity in the music and dance tradition within each area because a creative villager would draw upon his traditional elements as his artistic source. Thus, a new village dance would closely resemble the old dances, maintaining the artistic continuity, because they both used common traditional elements of that particular community. Although the regional style would change, as do all living traditions, it would do so very slowly over many generations.

Armenian villagers did travel, particularly as pilgrims to the large religious festivals, There they would be exposed to the music, songs, and dances of other villages and regions. When they returned home, they would describe and demonstrate these for their own village, often adding a local flourish to the song or dance. Some of these might be incorporated into the local repertoire, and modified to suit local tastes.

Another major factor in the diffusion of dance was the large scale transfer of populations to other areas. Life in Armenia was precarious due to its geographic and political position. Foreign invaders forced large segments of the population to move, at several points in history. Seljuk invasions in the 11th century led to the Armenian settlements in Sepastia and Cilicia. In the 16th century Shah Abbas deported a large number of the Armenian population to Persia. Nomadic Kurds then migrated into depopulated Western Armenia, which they presently dominate.

These population shifts are reflected in the dances. In 1828, 100,000 Armenians fled Turkey into the Caucasus during the Russo-Turkish War, repopulating areas Shah Abbas had devastated earlier. These Armenians from Erzerum brought their dances with them (that is, Keurogli, Uzundara, Akhalzikha Vart), where they still flourished a century later. Similarly, the intense Black Sea dances (that is, Laz Bar), were introduced into Erzerum, Yerzinga, and Sepastia by Pontic Greeks and Armenians of Treibizond. These Christians were fleeing the brigandage of Moslem Circassians that Russian had deported in 1864.

These Christians were fleeing the brigandage of Moslem Circassians that Russian had deported in 1864.

As a result, Armenian song and dance did not exist in discrete isolated units. Instead, it resembled an Oriental tapestry, combining different elements. Although the regional style of music and dance remained intact, some of the songs and dances may have originated elsewhere in a different form, and have been assimilated locally. Many songs were widespread, with different dances accompanying them in different areas (that is, Hoy Nar, Lepo Le Le). Conversely, the dance could be widespread, and done to different songs in different areas (that is, Bar, Sword Dance).

The same dance melody could also be known by different names in different areas. Thus, the dances known in Erzerum as Shavalee and Yerek Vodkh were known in Yerzinga as Hooshig Mooshig and Bilbil. This same process can be seen today in the diffusion of new American-Armenian party dances throughout the United States, adapting to local conditions.

The variety of Armenian dances as so extensive, and documentation so poor, that few individuals are familiar with even a fraction of the dances. A brief list of regional dances could include:

Sepastia Chekeen Halay, Bijo, Jan Perdeh, Divrigtsi Bar, Govduntsi Bar, Uch Ayak/Sepastia Bar, Preperttsi Bar.

Erzerum Khosh Bilezig, Kher Pan, Berzanig, Shavallee, Akhaltzikha Vart, Dasnachoors, Maro Yerek Vodkh.

Van Lepo Le Le, Govand, Daldalar, Papuri, Lorge, Sinjani, Sulimani, Sherokee, Haire Mamougeh.

Daron Yarkhoshda, Tooran Bar, Shoror, Gorani, Lorge, Kotchari Latchi, Bingeol.

Urmia Janiman, Sinjani, Bandi Shalakho, Tachayal Kitchari, Sheikhani, Roostam Bahzee.

Armenian Alphabet

Invented in 406 B.C. by Mesrob Mashtots

ARMENIAN DANCE AFTER 1915

The destruction of Western Armenia in 1915, and the subsequent dispersion of the survivors, irrevocably destroyed the traditional structure of Armenian dance. The conditions that had sustained it for millennia had ended. Uprooted from their ancestral homeland, the Armenians scattered throughout the world. The dances of the village had fulfilled important functional needs of the people in that particular context, but were not functional in the new conditions of the emigrants. Despite the loss of the old dance forms, dance still remains an integral part of Armenian life.

The conditions that had sustained it for millennia had ended. Uprooted from their ancestral homeland, the Armenians scattered throughout the world. The dances of the village had fulfilled important functional needs of the people in that particular context, but were not functional in the new conditions of the emigrants. Despite the loss of the old dance forms, dance still remains an integral part of Armenian life.

Today, the various Armenian communities have created or adopted new dance forms to fulfill the new needs which have developed under alien conditions, particularly in the urban communities of the Armenian S.S.R., the United States, and the Middle East. In each of these areas the development varied significantly, to adapt to the needs of that specific community. Unfortunately, no research had addressed itself to this area of cultural comparison.

In the United States, the traditional Western Armenian music and dance remained an important cultural factor in the American-Armenian communities, and integral part of society. As the Armenian language fell into disuse among many American-born Armenians, the music and dance gained even more importance, as one of the remaining avenues of cultural identity maintenance. Today, this music and dance have developed into a characteristic form unique to the United States, and one of the principal means that today's American-American youth assert their Armenian identity.

As the Armenian language fell into disuse among many American-born Armenians, the music and dance gained even more importance, as one of the remaining avenues of cultural identity maintenance. Today, this music and dance have developed into a characteristic form unique to the United States, and one of the principal means that today's American-American youth assert their Armenian identity.

This popular American-Armenian tradition is a synthesis of two dissimilar Western Armenian styles: the urban "Oriental" style and the rural "folk" style. These styles were preserved and fostered in the United States for decades through the picnics of the "compatriotic unions." These unions were comprised of groups of people who had come from and were often the sole survivors of villages or towns in Turkey.

The unions' primary purposes were to provide mutual support for members and to collect funds, and found new villages in Soviet Armenia, bearing the same name as their old homes. They also acted as important perservers of Armenian customs and traditions, retaining regional styles of dialect, songs, food, music, and dance for decades. The dances of each specific region were retained in isolation at the picnics and gatherings of that specific regional union, and were not known to other unions. (One would not find the songs and dances of Van at the Sepastatsi picnics, and vice versa.)

They also acted as important perservers of Armenian customs and traditions, retaining regional styles of dialect, songs, food, music, and dance for decades. The dances of each specific region were retained in isolation at the picnics and gatherings of that specific regional union, and were not known to other unions. (One would not find the songs and dances of Van at the Sepastatsi picnics, and vice versa.)

Although some unions are still active today, these compatriotic societies began to lose influence after World War II, when a younger Armenian-born generation came of age. This new generation did not share the nostalgic memories of their parents (after all, these youth had never seen these regions of Armenia), and preferred to focus their interest in institutions with a broader community base (that is, the church). Up until this time, Armenian music and dance were often considered somewhat old-fashioned and esoteric. It had remained confined in Popularity because each compatriotic union restricted itself to its own music, ignoring other regional traditions. As the stress on provincial regionalism diminished, a new interest in a wider "Pan-Armenian" identity replaced it. A new form of music was needed that would be acceptable to most people. The traditional music, in its original form, had too many associations with narrow interest groups.

As the stress on provincial regionalism diminished, a new interest in a wider "Pan-Armenian" identity replaced it. A new form of music was needed that would be acceptable to most people. The traditional music, in its original form, had too many associations with narrow interest groups.

In the late 1940s, the rise of the Vosbikian Band (followed by Artie Barsamian, the Gomitas, the Nor-Ikes, etcetera) heralded the American-Armenian "big band" era. These bands utilized western instruments (that is, guitar, saxophone, conga drums, bongos), and created a new Armenian "sound" that won wide acceptance. A homogeneous style of "American-Armenian" music developed which incorporated elements of both the urban and rural traditional music, and contemporary American music (that is, jazz and Latin rhythms). The music (and the dance) lost much of the subtle characteristics that distinguished the distinctive regional styles, but the resulting popular idiom brought new vigor to Armenian music and dance. This new style of music enabled the community to integrate itself on a much wider scale as a common interest of all groups.

This new style of music enabled the community to integrate itself on a much wider scale as a common interest of all groups.

Old songs were altered to fit this new, brash sound, and new songs and dances were created. These quickly established themselves as part of a new American-Armenian folk tradition. Closer contact with other Middle Eastern immigrant communities in the United States (that is, Greek, Arabic, Assyrian) led to the adoption of numerous songs and dances from these cultures. Modern American-Armenian music is "Pan-Middle Eastern," and incorporates many elements.

A new American-Armenian dance form also developed. These dances derive from three distinct sources. Some of the dances are traditional village dances that have been modified to fit the new music (that is, Halay, Tamzara, Papuri Sepastia Bar, Laz Bar). Other dances have been adopted and modified from ethnic groups (that is, Misirlou, Syrtos, Tsamiko, Dabke). Most of the dances, however, have been created by Armenian teen-agers and later adopted by adults (that is, Shuffle, California Hop, Michigan Hop). Although certain American-Armenian regional differences in repertoire and style exist (that is, Boston style, Detroit style, Fresno style), the popular dances are fairly uniform throughout the United States. The numerous youth conventions play a major role in the diffusion and maintenance of these contemporary party dances.

Although certain American-Armenian regional differences in repertoire and style exist (that is, Boston style, Detroit style, Fresno style), the popular dances are fairly uniform throughout the United States. The numerous youth conventions play a major role in the diffusion and maintenance of these contemporary party dances.

International folk dancers who attend an Armenian dance are sometimes disconcerted to find that the Armenian dances they know are quite different from the dances that the Armenians perform. Frequently, the Armenians have never heard of the dances popular among international folk dancers. The international folk dance (IFD) dancers are drawn from several traditions (stage, popular, traditional) that most Armenians are unfamiliar with, and the "turnover" rate in IFD is higher. ("This year's" dance is passe by next year.)

Armenian dances do change, of course, as any living tradition, but at a fairly slow rate. The Armenian "Shuffle" (known in IFD as Cari Me Na / Kadeh Yes Em) was created in 1951 in Lawrence, Massachusetts. By 1957, it had spread to the California Armenians. Today it is still the most important American-Armenian dance, aside from the basic bar. (Unlike most youth-created dances, it is not very strenuous, which probably accounts for its longevity.)

By 1957, it had spread to the California Armenians. Today it is still the most important American-Armenian dance, aside from the basic bar. (Unlike most youth-created dances, it is not very strenuous, which probably accounts for its longevity.)

Armenian teen-agers are the primary dance innovators and their dances are the most ephemeral. These dances can wax and wane with amazing rapidity, similar to the dance fads of mainstream America. The "California Hop" (Tom Bozigian's Hink ou Meg) was introduced to New England Armenians in the mid 1970s, reached a peak of popularity, and is currently waning. Sulemani, a Vanetsi dance we introduced from Detroit, and Guhnega, a choreography of Tom Bozigian, are becoming local favorites, although both were unknown here in 1979.

Some new dances are actually old village dances in a new form ("old wine in new skins"). The old Venetsi Wedding Dance Haire Mamougeh regained popularity in New York City around 1978, as the "Armenian Cha-Cha. " The old dance Laz Bar (double Tik in Pontos) died out in much of New England in 1960. In 1974, it was learned at a Chicago convention and reintroduced as a new dance. Internal Armenian politics also create significant differences, because the political parties rarely associate. The dances performed at an Armenian Church Youth Organization of America (ACYOA) dance can differ somewhat from the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF) dance a mile away.

" The old dance Laz Bar (double Tik in Pontos) died out in much of New England in 1960. In 1974, it was learned at a Chicago convention and reintroduced as a new dance. Internal Armenian politics also create significant differences, because the political parties rarely associate. The dances performed at an Armenian Church Youth Organization of America (ACYOA) dance can differ somewhat from the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF) dance a mile away.

Armenian folk dance, like all living traditions, is a continually evolving form. The rapid changes since 1917 reflect the adaptation to new environments and needs. The contemporary American-American dances provide a basis for ethnic integration and identity. The massive influx of immigrants from Lebanon, Iran, and Soviet Armenia in the late 1970s, will further change the dance, particularly on the West Coast. The elaborate choreographies of today's stage groups satisfies vital Armenian social, idealogical, and political needs by presenting Armenian dance in "the best possible light," as defined by tastes of Western theater audiences.

ARMENIAN DANCE PERFORMERS AND INSTRUCTORS IN AMERICA

The versatility of Armenian musicians in the United States has had a profound impact on other forms of Middle Eastern music in America. The dance has, until recently however, remained exclusively an Armenian property, insulated from the outside community. The major media exposing Armenian dance outside of the community have been various dance groups or teachers.

A culture's dance generally reflects other values held by that culture. The Armenian traditional, contemporary, and stage dances have developed and changed in response to important social, political, and ideological changes within the community. It is impossible to understand American-Armenian dance outside of this context.

After the genocide, the most important local cultural organizations were the various compatriotic unions. The dance and culture of each distinctive region were preserved at these gatherings. The first "Armenian dance groups" in the United States were informal presentations at these meetings, where several people form the same village would perform their particular village dance. Occasionally, "ad hoc" dance groups were organized to perform at the annual picnic or banquet, but these informal dance groups remained ephemeral, and only performed within the context of the union's functions.

The first "Armenian dance groups" in the United States were informal presentations at these meetings, where several people form the same village would perform their particular village dance. Occasionally, "ad hoc" dance groups were organized to perform at the annual picnic or banquet, but these informal dance groups remained ephemeral, and only performed within the context of the union's functions.

The first formal Armenian dance groups were a direct response to the nascent international folk dance movement. The Armenian Folk Dance Group of Boston was the first formal performing group in the United States (1926 to 1928). The director, Arevalois Deranian Kasparian, had become interested in folk dance as a young girl and learned many international folk dances in classes at the İstanbul Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA). While later residing at an Armenian orphanage, she collected several different regional dances. Unlike the compatriotic unions, her group performed a variety of dance from several regions, concentrating on the song-dances.

The next major group developed ten years later. The Armenian Folk Dance Society of New York was founded in 1937 by Catherine Mirijanian, a secretary at the McBurney YMCA in New York City. The founders wanted to create a dance group to represent Armenia at international festivals, comparable to the dance groups of the Lithuanians, Italians, etcetera. The society was the first Armenian group in the United States to attempt to systematically collect the dances from the various provinces.

The society collected and performed over twenty-five different regional dances, particularly from Sepastia, Van, and Garin. The society was performance oriented and only collected dances that could be presented on stage. Unfortunately, several dances deemed too boring or too simple for stage were ignored and subsequently lost.

The American-Armenian community became exposed to Kavkaz style in the late 1940s, because of several factors. A considerable number of Soviet Armenian soldiers had been captured by the Germans during World War II. A number of these emigrated west after the war rather than return to the Soviet Union. This group included several dancer-choreographers such as Arshod Azruni and Haigaz Mgrditchian, who founded Kavkaz style dance groups in the United States.

A number of these emigrated west after the war rather than return to the Soviet Union. This group included several dancer-choreographers such as Arshod Azruni and Haigaz Mgrditchian, who founded Kavkaz style dance groups in the United States.

Another major factor in the introduction of the Kavkaz style was the change of political climate. In the late 1940s, the Soviet Union opened its borders to immigration for the first time since the October Revolution. Many leftist-oriented Armenian political groups initiated extensive publicity campaigns within the Armenian community. Some groups organized style dance groups to promote Soviet Armenian culture. In response to these political campaigns, tens of thousands of Armenians around the world immigrated to "the Motherland" in the late 1940s.

This political campaign (and its dance groups) became discredited and collapsed shortly afterward, as word of Stalinist purges in Armenia reached Armenians living outside their homeland (the diaspora). The Cold War ended this establishment of harmonious relations (rapprochement) with Soviet Armenia for several years.

The Cold War ended this establishment of harmonious relations (rapprochement) with Soviet Armenia for several years.

In the late 1950s, the American international folk dance community had its first major exposure to Armenian dance, because of the workshops of Vilma Matchette and Frances Ajoian, both of California. Mrs. Matchette collected and taught several of the popular dances done by Armenians, the initial "contemporary party dances." At the time no Armenian attempted to record these dances, and her classes are an important documentation of the dance at this period in time.

Mrs. Ajoian directed the Cilicia Armenian Dance Group in Fresno, California. This group paralleled the Folk Dance Society of New York in some respects, presenting traditional Western Armenian dances to the public. Mrs. Ajoian collected dances among the elderly and taught these dances at workshops. Several "standard" Armenian dances still performed in international folk dance circles date back to this era (that is, Laz Bar, Shuffle / Dari Me Na, Tamzara, etcetera).

In 1960, the team of "Hourig and Sossy" (Hourig Paplazian Sahagian and Sossy Krikorian Kadian) began performing on the East Coast. These women revived the old Kanto tradition of İstanbul and combined it with American vaudeville. Still performing in 1982, their act combined dance, song, acting, and mime into a coherent whole, telling stories (usually satirical) in several mediums.

Until the early 1960s, the repertoire of Armenian performing groups in the United States remained primarily Western Armenian, reflecting the origins of the immigrants. Aside from a few solo or couple dances (that is, Tamzara, Lezginka, Shalakhoi), the Kavkaz style was almost unknown. One exception was Haigaz Mgrditchian's group in Boston, Massachusetts. Dance groups were generally small and poorly funded, often being held together by one or two dedicated individuals.

It was difficult to locate actual folk garments for the dance groups to copy, because few authentic costumes had survived the 1915 genocide. Most groups' costumes were either an approximation, because of lack of funds, or elaborate highly romanticized reconstructions. Historic accuracy was not a major priority for most groups, aside from the New York Society.

Most groups' costumes were either an approximation, because of lack of funds, or elaborate highly romanticized reconstructions. Historic accuracy was not a major priority for most groups, aside from the New York Society.

The folk dance's theatricalization remained somewhat rudimentary, because no formal institution teaching Armenian choreography existed in the diaspora. The most successful Armenian-American choreographers were dancers who had extensive ballet background, and applied principles learned in ballet to the folk dance (that is, Seta Suni, Nevarte Hamparian, Seta Gelenian). The 1960s, however, witnessed a rapid transformation of Armenian dance groups into their present form.

The first American tour of the Armenian State Dance Ensemble in the 1960s electrified American-Armenian audiences. Many third generation American-Armenians were unfamiliar with Armenian dance (either Eastern or Western), associating dance with the quaint steps of their grandparents, or with the popular American-Armenian party dances. The Moiseyev-like acrobatics of the State Dance Ensemble transfixed the audiences, who readily accepted that this exciting ballet-derived folk dance was a "purer" form of Armenian dance. The existing performing groups began to pattern their repertoires after the State Dance Ensemble.

The Moiseyev-like acrobatics of the State Dance Ensemble transfixed the audiences, who readily accepted that this exciting ballet-derived folk dance was a "purer" form of Armenian dance. The existing performing groups began to pattern their repertoires after the State Dance Ensemble.

Soon after this aesthetic re-evaluation, a social/ideological re-evaluation began. Until the mid 1960s, the American-Armenian communities were supported on a local level. The funds raised for the large international Armenian institutions (that is, the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), Armenian Relief Society (ARS), Tekeyan, Hmizkaine), were used to support the extensive Armenian communities in the Middle East, building schools, orphanages, cultural centers, etcetera. In the mid 1960s, these organizations realized that they had ignored the American communities completely, and that extensive cultural assimilation was endangering the American-Armenian community.

Somewhat belatedly, these groups refocused their efforts to develop an infrastructure comparable to that in the Middle East. Funds and leadership were provided to set up Armenian Day Schools, cultural centers, choral societies, theater groups, athletic teams, and dance groups. The rapid deterioration of conditions in Lebanon and Iran in the late 1970s has proven the wisdom in this policy.

Funds and leadership were provided to set up Armenian Day Schools, cultural centers, choral societies, theater groups, athletic teams, and dance groups. The rapid deterioration of conditions in Lebanon and Iran in the late 1970s has proven the wisdom in this policy.

Given the sponsorship and resources available through these organizations, many dance groups changed. Small, locally autonomous groups were incorporated into national networks, affiliated with a particular political or cultural organization. Dance instructors trained in the State Ensemble style were imported to organize these dance groups or found new ones. New dance groups, such as AGBU's Arat (New York) and Sardarabad (Los Angeles), now have over a hundred members and require extensive financing.

The importation of trained "professionals" to teach the dance has further accelereated the "sovietization" of dance groups in the United States. The Western Armenian dance had never been formalized into a teaching curriculum, as the Eastern had, and could not compete successfully. Today, virtually every Armenian dance group is a derivative of the State Dance Ensemble. The only Western Armenian dance groups left in North America are the Armenian Folk Dance Society of New York and two offshoots, Nayiri (New York) and Navasard (Boston).

Today, virtually every Armenian dance group is a derivative of the State Dance Ensemble. The only Western Armenian dance groups left in North America are the Armenian Folk Dance Society of New York and two offshoots, Nayiri (New York) and Navasard (Boston).

Aside from the dances introduced by Vilma Matchette and Frances Ajoian, very little Armenian dance was known in the IFD circles until the late 1960s. Haigaz Mgrditchian choreographed an Armenian suite for the Duquesne University Tamburitzans in 1965, but this had little impact on the larger IFD community. Ron Wixman and Steve Glaser taught several dances that they had learned as members of the Armenian Folk Dance Society of New York, but their exposure was limited.

About 1970, Tom Bozigian began teaching Armenian dance, and permanently changed the repertoire of international folk dancing. His familiarity with traditional, contemporary, and stage dances allowed him to teach a wide variety of Armenian dance forms that appealed to most segments of the IFD community. A combination of shrewd marketing, dance training (performer/teacher/choreographer), and iron constitution enabled him to present Armenian dance virtually everywhere. To many non-Armenians, his name is synonymous with Armenian dance.

A combination of shrewd marketing, dance training (performer/teacher/choreographer), and iron constitution enabled him to present Armenian dance virtually everywhere. To many non-Armenians, his name is synonymous with Armenian dance.

In the late 1970s, several other important Armenian dance figures appeared on the scene. On the West Coast, a number of other professional dancers trained at the Sayat Nova Choreographic School immigrated to the United States. However, none of these individuals had any significant impact on the IFD community because they preferred to concentrate within the Armenian community. (The attitudes and expectations of international folk dancers can appear quite bizarre to an outsider.)

On the East Coast, Arsen Anoushian and Gary and Susan-Lind Sinanian were the most significant figures. Arsen was the director of the Armenian Folk Dance Society of New York and one of the foremost Western Armenian stylists in the Unites States. Although his primary interest was working within the Armenian community, he taught several workshops for the Balkan Arts Center in New York City. His main focus, however, was teaching the dances in local colleges for the Armenian student clubs and perpetuating these dances through his dance group.

His main focus, however, was teaching the dances in local colleges for the Armenian student clubs and perpetuating these dances through his dance group.

Used with permission of the author.

Reprinted from "Hungarian Folk Dance Types and Dialects" by Gary and Susan Lind-Sinanian

in Viltis Magazine, January-February 1982, Volume 40, Number 5, V. F. Beliajus, Editor.

Armenian dance lessons

Armenian dance lessons in Moscow: Kavkaz Land is beyond competition!

Gym, fitness, running, swimming are all effective ways to keep fit. But everyone has one drawback: at times, such “same-type” activities bring boredom, and in some cases they get bored at all. Yes, and to demonstrate them to others "for an encore" will not work - except perhaps within the limits of sports competitions.

Quite different - Armenian dances ! Teaching them is by no means boring, and there will always be more than enough people who want to see the results of such lessons “live”! If you want to learn charismatic and spectacular dances - welcome to the Caucasian Dance School "Kavkaz Land"!

We recruit EVERYBODY, regardless of gender and age, to groups where Armenian dances are taught . Our choreographers know how to find an approach to everyone and will gladly share with you the secrets of dance skills. Professional Armenian dance lessons will help:

Our choreographers know how to find an approach to everyone and will gladly share with you the secrets of dance skills. Professional Armenian dance lessons will help:

- Bring the body into excellent physical shape.

- Significantly improve motor coordination.

- Develop flexibility, plasticity and develop a beautiful posture (especially important for girls and women).

- Increase the endurance of the body, improve health.

- Get rid of psychological problems, depression and insecurity (and at 100%!).

- Feel interest in life.

- Learn to achieve your goals.

- Find new friends who are passionate about a common cause.

And, of course, you will learn how to dance beautifully. And with due diligence - also at a professional level!

Experienced teachers from the School of Caucasian Dance Studio "Kavkaz Land" give dance lessons in Armenia in all directions . Group and individual training is provided. Group classes are conducted with a limited number of students, so they are held as efficiently as possible. In the case of an individual approach, you can discuss with the choreographer the time of the lesson that is convenient for you.

Group and individual training is provided. Group classes are conducted with a limited number of students, so they are held as efficiently as possible. In the case of an individual approach, you can discuss with the choreographer the time of the lesson that is convenient for you.

We also provide professional services for staging Armenian wedding dance for newlyweds. With our help, in just a few lessons you will learn one of the most beautiful folk dances of the Caucasus and Transcaucasia, which will be a real surprise for your guests!

Detailed information about Armenian dance lessons in "Kavkaz Land" and the cost of classes can be found on the website http://kavkaz-land.ru/.

Armenian dances - what are they?

There are a lot of them and they are all extremely beautiful. By choosing Armenian dance lessons in all directions , you will be able to learn:

- "Berd". Means "fortress" in Armenian.

This name is associated with one of the obligatory elements of the dance - a two-tiered "fortress" that the dancers "build" by climbing on each other's shoulders.

This name is associated with one of the obligatory elements of the dance - a two-tiered "fortress" that the dancers "build" by climbing on each other's shoulders. - Kochari. A very dynamic and expressive collective dance, in which the leading part belongs to men, and women seem to “weave out” their beautiful pattern shading it with their dance.

- "Thrahag". Another male dance that is performed alone, in a duet or in a dance group. This is a kind of “dance of a warrior”, during which the ability of a man to wield a saber or two at once is demonstrated.

- Uzundara. In former times, it was considered a ritual dance of the bride, but even now it is often performed at weddings. Sometimes a woman dances it in tandem with a man. The dance is characterized by very smooth, light, unhurried movements, alternating with more active elements of the dance.

- "Yarkhushta". In ancient times, men performed it in pairs before battles and after the end of the battle.

Now this rhythmic, energetic and incendiary dance is considered festive and cheerful.

Now this rhythmic, energetic and incendiary dance is considered festive and cheerful. - "Lorke". An Armenian dance in which men and women form a line, semicircle or circle, holding each other by the little fingers, shoulders or hands. The lead dancer holds a handkerchief in one hand. A rather measured dance with a characteristic, repetitive dance pattern.

- "Artsakh". A very beautiful, dynamic dance with alternating female and male parts.

And keep in mind that only a part of the repertoire is listed here, which teachers from our Studio School will gladly teach you.

Be sure to contact us! Armenian dance training is a sea of positive, sincere atmosphere, friendly staff and quite affordable prices!

beauty and refinement – Armenian Museum of Moscow and culture of nations

Articles, ExpositionEdition culture, dancing0081 March 04, 2020 culture, dance

Dancing occupies an important place in the rich and multifaceted Armenian folk art. They were formed at a distant time of the primitive communal system and, changing to one degree or another, have come down to us, retaining the beauty and refinement of forms.

They were formed at a distant time of the primitive communal system and, changing to one degree or another, have come down to us, retaining the beauty and refinement of forms.

Gevorg Grigoryan (Giotto). "Dance", 1961. National Gallery of Armenia

Historians and writers of Armenia mention the popularity of folk-professional art. According to Movses Khorenatsi, the province of Goghtn (Nakhichevan) was famous for storytellers, singers, dancers and musicians. The dancers accompanied their performances by playing musical instruments, most often on bambire (type of string instrument). Since the 5th century, many church leaders began to officially oppose the art of gusans, so that the people would not attend "impious spectacles." Although the clergy fought against the games, the rulers understood that during the mass processions and collective dances the unity of the people was strengthened.

On holidays, collective and solo dances were performed, the technical difficulties of which could be overcome through constant exercises. As a rule, the best dancers and elderly people led the classes. Dances and song dances were performed in various rooms of a residential building - in a cleared barn, in a churchyard, on a flat roof, courtyard, street, square, current, cemetery, lawn, field, on a mountain slope, on a summer pasture, in places of pilgrimage.

According to the number of participants, Armenian dances and song dances are divided into solo, duet, group and collective, often nationwide. Adult dances are divided into male, female and joint. In the old days, children did not participate in adult dances: there were special children's dances - secular and ritual.

Group dances are led by paraglux (paraglux) - leader. Next to him is his assistant. The dancer standing at the end of the formation is called počʻ (poch) - "tail". In collective, solo and duet dances, they often dance with scarves, flowers, branches, candles, torches, bowls of ash, less often with weapons, sticks, and spoons. They dance in festive attire or put on special clothes. Only during field work in the old days they danced in everyday clothes.

Next to him is his assistant. The dancer standing at the end of the formation is called počʻ (poch) - "tail". In collective, solo and duet dances, they often dance with scarves, flowers, branches, candles, torches, bowls of ash, less often with weapons, sticks, and spoons. They dance in festive attire or put on special clothes. Only during field work in the old days they danced in everyday clothes.

In ritual dances, the number, sex, age of participants, marital status, widowhood are strictly observed.

In collective dances, they usually form in a circle, in a semicircle, less often in two rows.

In the old days it was customary to first perform mournful memorial dances in memory of ancestors. By the beginning of the 20th century, they had already acquired a secular content. It has long been believed that building in a circle protects from evil spirits. Wishing to "catch" them, the movements of the legs outlined the network, weaves, knots. At the same time, knots and a network once depicted the plight of man.

At the same time, knots and a network once depicted the plight of man.

There are many Armenian dances with epic, lyrical or everyday secular content. There are thousands of dance songs, and new lyrics are usually combined with old refrains.

Veik Ter-Grigoryan. "Armenian Dance", 1944. National Gallery of Armenia

The Armenian dance art has certain regularities and a number of characteristic features. This is the main (prevailing) direction of movement of the participants. In Armenian dances, there are steps both to the right and to the left: but one of the directions, as a rule, prevails. The direction of movement is one of the fundamental characteristics: it is related to the magical function of dance. The largest number of dances in the Armenian folk art has the predominant movement of the participants to the right: this is how the idea of correctness, well-being, good luck is embodied. The reverse direction - to the left - symbolizes failure. Armenians were afraid to pronounce ĵakh (dzakh) - “left”, preferring to indicate the direction with their hand and add “there” or use the word t'ars (tarsus) - "on the contrary." Folk thinking is reflected in the name of the type of dances with a predominant movement to the left: t’ars par (tars par) - “reverse dance”. It was also important with which foot to start the movement.

The reverse direction - to the left - symbolizes failure. Armenians were afraid to pronounce ĵakh (dzakh) - “left”, preferring to indicate the direction with their hand and add “there” or use the word t'ars (tarsus) - "on the contrary." Folk thinking is reflected in the name of the type of dances with a predominant movement to the left: t’ars par (tars par) - “reverse dance”. It was also important with which foot to start the movement.

Character of dance figures. The figures forming the dance can be simple, reducible to one dance phrase, or complex. The latter combine a number of dance phrases, each consisting of several movements.

The number of performers and the semantics of numerical symbols. Most of the dances were open to everyone present, without any restrictions. These are 90,093 collective dances, 90,094 performed at weddings, annual holidays, and public gatherings.

If part of those present danced, then such dances were called group dances. Depending on the gender of the participants, they could be male, female, or mixed. In mixed dances, the men stood up first, followed by the women, but the last man and first woman had to be related.

Duet dances (men's, women's, mixed) were mainly formed as ritual dances and often represented a competition. They used objects - sticks, scarves, cups, sabers, branches, flowers. Courage, endurance, the ability to wield weapons were demonstrated. Solo dances were performed by a man or a woman and, apparently, were a vestige of the former parties of the main characters in a ritual round dance epic action.

In the system of ritual dances, is the symbolism of the numbers - most often it is 3, 4, 7, , which is typical for the traditional beliefs of Armenians. The number 3 corresponds to the dance figure erek votk’ (erek votk), i.e. consisting of three steps. It means to take two steps-prefixes, one step - to return. Varieties of this figure: in three steps with jumps, in three steps with blows, in three legs with a variable transfer of body weight.

It means to take two steps-prefixes, one step - to return. Varieties of this figure: in three steps with jumps, in three steps with blows, in three legs with a variable transfer of body weight.

In public dances, this type of movement was performed at the beginning of the ceremony as a memory of the ancestors. Progress to the right prevailed. In wedding dances, it was obligatory to go around the circle three times. The performers carried lighted candles with three branches. The repetition of the number 3 had, apparently, a connection with the tripartite structure of the tree of life.

Another common dance figure is č’ors votk’ (chors votk), i.e. consisting of four steps, which means: two steps to the right and the same number to the left. In the Armenian dance tradition, as in many nations, the concept of the right is associated with a man, the left with a woman. The balance of right and left was mandatory for wedding ritual dances: only married couples participated in them, and the number of dancers was certainly even.

Grigor Khanjyan. Illustration for Gevorg Emin's poem "Dance of the Sasunts", 1975. National Gallery of Armenia

In a number of ritual dances, the number 7 is significant. So, in wedding dances, the minimum composition of performers is seven married couples, each has a candle (seven candles in total). Such dances are magical actions to ensure the fertility of the family. There are also ritual dances performed on the first day of Lent. In fact, this is the first of the seven days of the weeks repeated seven times.

Gender and age of the dancers. Singles and married men, young people, middle and older generations can participate in men's dances among Armenians. In women's dances, middle-aged performers predominate. Sometimes in ritual dances, especially wedding dances, the participation of older people with a high social status was obligatory. This determined the magical direction of the dance.

Dances, mixed in composition, usually include simple figures, so children willingly participate in them. Some ritual dances, especially play dances, eventually passed into the children's repertoire. They often imitate labor processes, sometimes acquiring a comic connotation. Such is the dance "Let's crush onions and garlic!".

In the Armenian folk choreographic culture since ancient times, peculiar kinetic turns have developed, which have received certain names. The well-known ethnochoreologist, folk dance theorist Srbui Lisitsian proposed the following classification:

- a straight (even) dance, consisting of prefix steps only to the right or only to the left. The pace is moderate. The movements of the arms and legs are restrained.

- slow dance. Two steps to go, one (step-prefix) to return in the opposite direction. Moreover, in the direction that is the main one for this dance, the steps are made a little wider than in the opposite direction. This figure is found in slow round dances with a slight bend in the knees, in Šoror (shoror) - dances with swaying, and Ververi (ververi) - dances with jumps and kicks. A number of figures are distinguished by a different number of steps to the right and left sides.

A number of figures are distinguished by a different number of steps to the right and left sides.

Ethnochoreology, ethnochoreography is a branch of folklore that studies folk dances.

Dances with kicks, heels or toes stand out. This combination of steps and jumps with strikes with both the right and left foot does not depend on the general direction of movement. The dancers strike mainly with the foot in which direction the next step or jump will be taken. Characteristic are turns of the body towards the leg with which the dancer hits the floor, as well as a change in the direction of movement by 90°.

Only men participate in dances where there is clapping and squatting. Clapping is considered to be an expression of joy. But in ancient dances, they can have a mournful or magical content, or imitate the blows of a weapon.

Šoror (shoror) - wiggle. Stepping from foot to foot or transferring the emphasis from one foot to another. If you hold on with your little fingers, bending your elbows, your arms will also sway. This figure is associated with movements that imitated natural phenomena, the gait of birds and animals. In ancient times, dances of this type were dedicated to generic and tribal totems.

This figure is associated with movements that imitated natural phenomena, the gait of birds and animals. In ancient times, dances of this type were dedicated to generic and tribal totems.

K’očʻari (Kochari). This view is based on the figure of two steps - to go, two to return - and is associated with pastoralism cults. Kochari - imitative dances in which images of goats and sheep are transmitted. People dressed up and put on masks. Perhaps, in ancient times, fights of male animals were transmitted by such dances. Kochari-type dances are a remnant of past actions during the Armenian Dionysius - festivities in honor of the god Spandaramet.

Ververi (ververi). Here the dance figures are the same as in the slow ones, but are performed at a fast pace, so the steps turn into jumps and foot strikes. In their origins, these dances are associated with the cult of the tree - a symbol of offspring. They believed that jumping up contributed to the growth of plants, animals, and people.

Ed [u] araĵ (ed u arach) - back and forth. Simple forward and backward steps alternate with right and left steps. The people also consider this as a reflection of the vicissitudes of life, the alternation of good and evil. Steps back and forth are a deviation from the “correct” move around the circle of life, a violation of normativity.

Ojajev (odzadzev) - imitation of snake movements. The dance figure with creeping foot movements is associated with the cult of good and evil snakes and dragons. Dances with creeping movements had the goal of propitiating good snakes - peculiar brownies.

In the old days people danced most often to singing. Then the unity of the song text, music and dance action began to disintegrate. The instrumental accompaniment pushed the vocal accompaniment, the verbal texts began to be forgotten.

Song dances were mostly named after one of the lines of the refrain. Text losses over time affected the safety of the name of the dance: it was reduced, or even completely forgotten. The names of the types of dance figures and individual and turned out to be more stable. For some time now they began to give names to dances.

The names of the types of dance figures and individual and turned out to be more stable. For some time now they began to give names to dances.

At present, almost all the dances that were once performed in different situations are included in the wedding ceremony. Therefore, they are now the main genre. Wedding ritual dances date back to deep pagan antiquity and had magical significance. They tried to ensure material well-being, numerous offspring and happiness for a married couple. Dances accompanied the entire wedding cycle, from the moment of matchmaking until entering the marriage bed.

After the musical "cry" - kančʻ (kanch), announcing the beginning of the wedding at dawn, dancing began. First, solemn and majestic slow collective ritual dances were performed, associated with the veneration of ancestors. Wedding ritual dances can be divided into three main groups:

- dances, through which they tried to call the location of the ancestors;

- amulets dances performed to protect young spouses from evil spirits and ensure their numerous offspring and well-being;

- dances once associated with initiatory rites, as well as with a remnant of the "kidnapping of the bride. "

"

The first group includes the collective dance “Mother of the crowned (king), come out!” and solo "Dance of the mistress of the house". They preceded the introduction of the bride into the groom's house, and in a number of areas they were called the "Dance of the bride's entry." Boys and girls took part in the dance. Before the introduction of the young into the house, they lined up in a semicircle in the yard of the groom. The song began:

Mother of the Crown Bearer, Come Out! / They brought you a sweeper, / They brought you a laundress...

Then they listed all the duties of a daughter-in-law and spoke about the relationship that she might have with her mother-in-law.

Crowned mother, come out! / They brought you a beater on the head, / They brought you a whipper by the scythes, / Look who they brought you!

The content of the song dance was not of a strictly ritual character. But she symbolized the transition of the newlyweds to the state of the married.

The mother-in-law, dancing, came out to the song-call of the groom's friends. She carried 3–7 lavash with her, danced incessantly, threw them crosswise on her daughter-in-law's shoulders, showered the newlyweds with sweets, and kissed them.

The ritual solo dance of the mother-in-law was performed only at the wedding at the threshold of the house at the moment the newlyweds were brought into it. Sometimes the "Dance of the Mistress of the House" was performed by two - the mother of the groom and the manager of the wedding meal. It was believed that the magical magical power of the dance was associated not only with the gender and age of the performer, but also with her position and functions in the groom's house. The mistress of the house, the mother of the groom, personified the representative of the ancestors at the time of the introduction of a new member into the clan - the daughter-in-law.

In many regions, in a dance form at the doorstep, a playful “fight” between father-in-law and mother-in-law was widespread, in which, as usual, the mother-in-law won.

The same group of dances, through which they tried to arouse the favor of the ancestors of the clan and members of the community, includes the solo male “Dance of the Matchmaker”. It was performed in the groom's house by one of the married representatives of the bride's family in the evening after the wedding.

The second group includes dances of different genres. In Armenia, solemn processions, meetings and farewells of rope dancers and wrestlers, weddings began with dancing.

If the path lay outside the village, then they danced until the procession approached the outskirts, and again continued dancing at the outskirts of another village. These dances were called "Road". They were solo, duet, collective, sometimes called "with a tail." In the latter, there were necessarily paraglux - “head of the dancers” and roč‘ - “tail”, the last of the dancers. The leader, often changing direction, led the string along a winding road, turning his face or back to the participants. One of the dances is called "Threads, threads", as there is an association between a string of dancers and a thread.

One of the dances is called "Threads, threads", as there is an association between a string of dancers and a thread.

The leader of the dance and the last of the dancers each held a large colored scarf in their hands. If the procession moved in the evening, then the scarves were replaced with torches, which not only illuminated the path, but also, as it were, “cleansed” it with fire from all “evil spirits”. The Armenians still have a custom during a wedding or a funeral procession to certainly return along a different road. Zigzag advances, rotations "covered" the tracks, protecting from the persecution of "evil spirits". The purpose of the string and in wedding dances is to keep evil spirits away from the newlyweds. Nowadays, road dances are performed only at weddings.

Wedding ceremonial dances, which ensure the fertility of the couple, include the dance of the bride and groom, which is widespread in all regions of Armenia. It was called "Dance with candles", "Dance of the bride and groom", "Sparkling". The names are not associated with the types of dance, but with their content and design. All dances of this type are characterized by a slow pace, solemnity. "Dance with candles" was a ritual action: in many areas it has been preserved in the memory of the older generation up to the present day.

The names are not associated with the types of dance, but with their content and design. All dances of this type are characterized by a slow pace, solemnity. "Dance with candles" was a ritual action: in many areas it has been preserved in the memory of the older generation up to the present day.