How dance is influenced by technology

Technology and Dance: Blending the Digital and Physical Worlds | by Shruti Satish | Digital Literacy for Decision Makers @ Columbia B-School

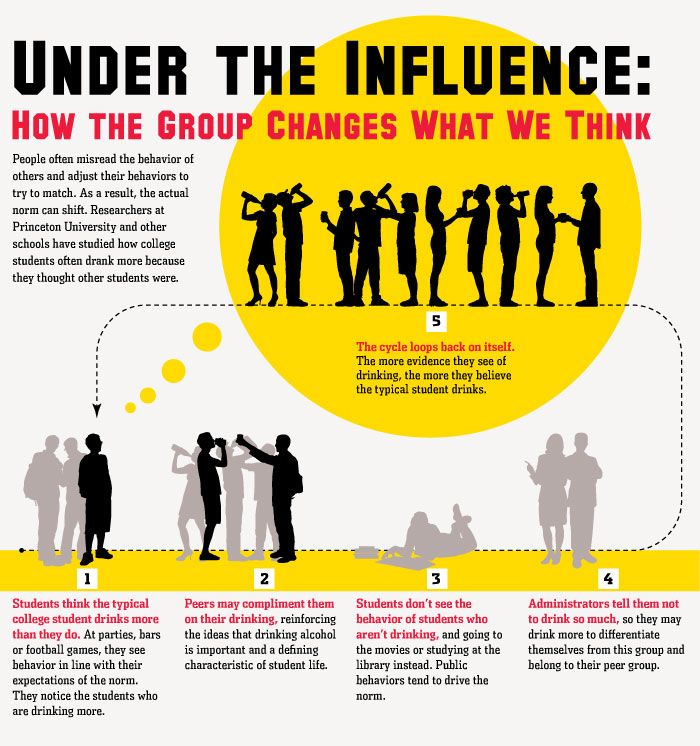

Image from the Adrien M / Claire B Company performance “Hakanaï” © Romain Etienne / ItemAsk any dancer what he or she finds to be the most basic underpinning of dancing and the answers will usually converge to one central idea: the human body. From bringing music to life to silently expressing ideas and emotions, dancers have long relied solely on the strength, endurance and power of the human body to create art through movement. As technology has permeated nearly every segment of our modern world, including art, it’s interesting to consider how it may redefine the role of the human body in dance and impact the artform more generally. For example, social media has increased exposure to dance, bringing previously underground dance styles, like hip-hop, into mainstream culture and giving dancers the ability to monetize their talents. Here, I’ll explore other ways in which technology has recently entered the sphere of dance, and ultimately enhanced the way we create, perform and consume dance.

Technology-enabled creation

A range of tools have emerged to help dancers and choreographers become better at their craft. For example, Electronic Traces is a technology product that uses tiny sensors placed on dancers’ shoes to capture their contact with the ground. This data can be displayed visually using an accompanying mobile application and dancers can review their movements immediately and with more precision than if they used a conventional video recording.

For the benefit of choreographers, projects like Motion Bank are working to create online libraries of dance moves, using Microsoft Kinect to annotate movements, and then transforming them into compilations of digital scores for choreographers to contribute to and access. I personally use a handy app called ChoreoRoom that lets me easily visualize, track and share formations when I choreograph for my business school dance team.

These kinds of technological tools are great, because they leave the creative process entirely intact, yet remove some of the administrative burden of choreographing and streamline the iterative improvement process for rehearsing dancers.

Digitally-enhanced movement

Gone are the days of simple 2-D backdrops that serve as neutral accompaniments to the dancers performing — backdrops now often use light projections to create objects and scenes around which the entire performance is constructed. As the dancers interact with their surroundings, their movements are both informed and contextualized by the projections. In 2015, French performing group, Adrien M/Claire B Company, delivered an iconic performance using such projection mapping tools to create mesmerizing 3-D illusions and enhance their storytelling. Perhaps a more easily accessible example of this technology is Beyonce’s “Run the World (Girls)” performance at the 2011 Billboard Music Awards — the backdrop of her performance displayed hundreds of virtual clones, with which she synchronized her choreography and put on a show-stopping performance (albeit one that sparked some immediate controversy).

Immersive and interactive consumption

Again, social media platforms such as Youtube and Instagram have done a decent amount of legwork when it comes to augmenting the reach of dance performances — but videos posted on these platforms still maintain the traditional relationship between dancers and the audience. Enter technology that disrupts this relationship by creating performances that transcend the “fourth wall” of the stage (or the screen). DUST is a prime example of such a performance, using Virtual Reality (VR) headsets to transport the audience alongside the dancers and allow them to interactively explore the space.

While not extremely widespread and likely not appropriate for every setting, this type of participatory performance presents an opportunity to creatively engage audiences and construct sensory, immersive experiences that reinvigorate the live performance landscape.

Conclusion

Ultimately, as is the case with other kinds of art, the extent of technology use in the creation and performance of dance is an artistic decision at its core and will inevitably vary from artist to artist. However, the introduction of technology into this space deserves praise for its ability to lower barriers to participating in this form of artistic expression. Similar to how the iPhone 8 Plus camera turned the world into amateur photographers, tools like those described above provide accessibility to dance by increasing the ease of choreographing, augmenting the reach of otherwise exclusive performances, and enhancing the entertainment value and novelty of performances.

However, the introduction of technology into this space deserves praise for its ability to lower barriers to participating in this form of artistic expression. Similar to how the iPhone 8 Plus camera turned the world into amateur photographers, tools like those described above provide accessibility to dance by increasing the ease of choreographing, augmenting the reach of otherwise exclusive performances, and enhancing the entertainment value and novelty of performances.

And while it may not seem intuitive that digital tools can enhance, or even preserve, the physical properties of dance, in moderation, technology can be infused with dance in a way that still centers on and celebrates the human body. In that way, technology is beginning to do for dance what it has done for countless other artforms, industries, and processes — an enabler that complements our given capabilities and elevates the ceiling of our potential.

Dance and Technology - Dance Informa Magazine

A look at how contemporary dance is using technology to support its vision.

By Elizabeth Ashley.

For many dancers and their audience the only technology of interest is the technology of the dancer’s body. Anything else is of secondary importance – sound, light and other media forms are used only to assist the dancer who is the prime carrier of the artistic message.

Technological development challenges this view and contemporary companies are increasingly performing works which incorporate sophisticated media/technology. Interestingly this technological frontier is a two-way street with dance companies incorporating technology while technological research incorporates dance in their exploration of motion-sensing, body memory and the process of visual empathy.

Asphalte by Compagnie Dernière Minute

The technology used in Asphalte is notable for its effective simplicity. The set is dominated by a central block of light which frames each piece, creating panels of a comic book. Like the computer screens most of us are familiar with, it is capable of providing a solid background, becoming translucent for the bodies behind it and providing a kaleidoscope of strobe-lighting shadows.

Primary colours and strong geometric lines give the stage sets a strong Pop-Art feel with small glowing cubes that provide the dancers with a multiplicity of energy forms. These simple props convey the prized quality of urban mobility as well as portraying diverse charges of energy from physical movement, static illumination, electrical charge, and microscopic cellular energy to a space-age lunar scape or post-nuclear fall-out.

Sydney Dance Company

6 breaths by Sydney Dance Company

The technology used in SDC’s 6 Breaths incorporates an opening and closing video-art projection by Tim Richardson to the music of Ezio Bosso. This monochrome projection consists of fragments that move like a flock of birds or leaves blown by the wind to magically form a giant 3-dimensional sculptured torso. This not only entrances the audience but also creates the dance theme of unfolding not as an act of fragmentation but of humanistic creation.

As in Asphalte, the technology sets the dance’s aesthetics and tone, in this case elemental classicism. The size and visual power of the projection could easily overpower the dance, hence it is strategically used to set the stage before the dance itself fully unfolds. The creator’s breath returns to close the performance as an embracing couple reforms from the blown fragments.

The size and visual power of the projection could easily overpower the dance, hence it is strategically used to set the stage before the dance itself fully unfolds. The creator’s breath returns to close the performance as an embracing couple reforms from the blown fragments.

Glow by Chunky Move

Gideon Obarzanek’s Glow uses sophisticated interactive video technology to create an intensely moving duet of sole dancer and technological ‘other’. With the use of a motion-sensing system and live-generated algorithms the technology fulfills its role of supportive partner as the dancer performs in a living responsive environment, with no two performances being exactly the same.

While this technologically intense work could be perceived as anti-humanistic, the choreographer, Obarzanek, chooses to highlight the analytical capabilities. When used sensitively, he argues that technology, like many diagnostic tools in our life, is capable of illuminating and embodying our abstract and internal relationships that would otherwise be invisible.

Dancing to the challenge

Each of these works highlights the significant challenge of technology for dance performance. Dancers are now challenged to dance with dynamic objects, against powerful live projections and/or within complex sensing spaces. And while the technological incorporation varies with each work, the success of each comes from the choreographer knowing how to integrate this technology into his or her particular aesthetic vision. This success is neither from ignoring technology nor necessarily seeking out the newest and most sophisticated developments. Rather, machines can only dance when they are sensitively incorporated into the dancing body, submitted to an artistic vision.

Photo from Asphalte. Credit Ian Bird.

Related Items:Contemporary dance, http://www.danceinforma.com, technology

How dancing affects thinking, and thinking affects dancing - Monoclair

Headings : Latest articles, Psychology

Did you find something useful here? Help us stay free, independent and free with any donation:

Donate

We are accustomed to think of dance as either an aesthetic act, or a purely emotional activity, consisting of chaotic movements, or a kind of physical exercise that challenges the abilities of our body.

However, Glory M. Liu, a researcher in the Department of Political Theory at Brown University, believes that dance is something more, it is a way to improve our ability to combine physical and mental intelligence and independent thinking, and our body is the most important tool with which we highlight the essence of things and we bring to life elusive and ephemeral ideas. We understand together with her why our experiments with our body can be much more useful than routine work and give us access to "achieving a sense of our being and satisfaction of the spirit."

However, Glory M. Liu, a researcher in the Department of Political Theory at Brown University, believes that dance is something more, it is a way to improve our ability to combine physical and mental intelligence and independent thinking, and our body is the most important tool with which we highlight the essence of things and we bring to life elusive and ephemeral ideas. We understand together with her why our experiments with our body can be much more useful than routine work and give us access to "achieving a sense of our being and satisfaction of the spirit." I am an eternal dancer and political theorist. “Working” and “thinking” for me, on the one hand, is a completely physical process, and on the other, a completely intellectual one.

For most of my career, dancing and research have been two distant but equally important areas. However, over the years I have become more and more aware that dancing for most people is seen as a not very significant way of mental activity and work. Dance, in their understanding, is a purely emotional activity, consisting of mindless, voluntary movements or purely athletic exercises, the sole purpose of which is to challenge the abilities of our body.

Dance, in their understanding, is a purely emotional activity, consisting of mindless, voluntary movements or purely athletic exercises, the sole purpose of which is to challenge the abilities of our body.

The main reasons why there is such an attitude towards dancing, in my opinion, are deeply rooted in our minds prejudices against the inner vocation. In his treatise "Politics" Aristotle depicts an ideal state in which mechanics, farmers, shopkeepers and others live banauson bion - a life of manual and "black" labor and do not have the full range of civil rights. Their daily routine leaves no time for leisure, but their work is necessary for those who take care of the deliberative processes in the city. In our time, we continue to distinguish similar groups, only at the lowest level of the hierarchy is "low-skilled" labor, and at the highest - "highly skilled". We are deeply mistaken when we argue that those who work with their hands are out of competition compared to those who work with their heads. And vice versa.

And vice versa.

Dancers stand on the threshold of this kind of belief. Our bodies are the most important tool with which we collect, isolate essence and bring to life elusive and ephemeral ideas. However, while doing all this, we also look like talented artists. And this definitely pumps up our ability to combine physical and mental intelligence, all this not only gives us the opportunity to stage and perform a dance, but also make it bright and filled with energy.

We dancers teach and learn, support everything related to physical expression . I, like many others, started dancing as a child, and quickly delved into the world of rules, clichés and habits. The left hand is on the barre before starting the movement and always turns towards the barre before changing sides. Stand in the fifth position, but first take the natural first. Forward-face-forward-backward. Elbows, wrists, fingers; heel, arch of the foot, toes. During training, you learn to distance your essence from your body, the physical shell. Focus your energy on the structure and aesthetics of the movements, whether you're staging classical ballet, modern dance, or whatever. However, to treat dance as a physical manifestation to which we subordinate our individuality means to be deeply mistaken. According to Teresa Ruth Howard, American choreographer and stage director, dance "romanticizes the dehumanization (dehumanization) of the body, treating it as a tool, clay from which you can mold anything" . This turns our physical bodies into mere tools for ideas, beliefs, manifestations from some external source - whether the technique comes from a teacher, choreographer, or your own idea. Where, then, does the dancer find space for freedom, for the manifestation of his individuality while engaging in this kind of physical practice?

Focus your energy on the structure and aesthetics of the movements, whether you're staging classical ballet, modern dance, or whatever. However, to treat dance as a physical manifestation to which we subordinate our individuality means to be deeply mistaken. According to Teresa Ruth Howard, American choreographer and stage director, dance "romanticizes the dehumanization (dehumanization) of the body, treating it as a tool, clay from which you can mold anything" . This turns our physical bodies into mere tools for ideas, beliefs, manifestations from some external source - whether the technique comes from a teacher, choreographer, or your own idea. Where, then, does the dancer find space for freedom, for the manifestation of his individuality while engaging in this kind of physical practice?

The practice of cultivating individuality and independence is incredibly important to our physical and moral sense of self. In terms of my dancing career, I learned to respect and appreciate these factors quite late, but relatively early in my work as a political theorist. In 2013, I entered graduate school, but continued to dance and even participate in modern dance performances, despite the fact that previously I had been doing classical ballet for most of my practice. I received multiple injuries and underwent surgery. I began to worry that my body was past its peak, no longer capable of handling the demands of the arts, and that it was time to leave dancing and find something better. Luckily, one moment while training in ballet class changed my mind.

In 2013, I entered graduate school, but continued to dance and even participate in modern dance performances, despite the fact that previously I had been doing classical ballet for most of my practice. I received multiple injuries and underwent surgery. I began to worry that my body was past its peak, no longer capable of handling the demands of the arts, and that it was time to leave dancing and find something better. Luckily, one moment while training in ballet class changed my mind.

Muriel Maffre, former premier (leading soloist) of the San Francisco ballet, and at the time my teacher at Stanford University, drew our attention to combinations. “Dancers,” he said, “have a habit of breaking their habits. Show that your spirit is stronger than your body." There was only a short pause before the accompanist gave us four counts, and we started the combination batman-tandu again, but the words of the teacher sounded in my head and echoed in my body until the end of the lesson. Until that day, I was convinced that dancing was about memorizing certain movements and forming certain habits, thanks to which I could perform all the previously learned movements on autopilot as soon as I crossed the threshold of a dance studio. But Maffre's guidance helped me to listen to common sense and begin to doubt, and even give up some habits, both physical and emotional, despite the fact that it once took me decades to develop them. I do not mean that immediately the ballet itself - in its organizations and combinations, dictionaries and grammar - turned upside down for me. On the contrary, it meant that even formal, purely technical elements should be filled with my energy, reflect my individuality.

Until that day, I was convinced that dancing was about memorizing certain movements and forming certain habits, thanks to which I could perform all the previously learned movements on autopilot as soon as I crossed the threshold of a dance studio. But Maffre's guidance helped me to listen to common sense and begin to doubt, and even give up some habits, both physical and emotional, despite the fact that it once took me decades to develop them. I do not mean that immediately the ballet itself - in its organizations and combinations, dictionaries and grammar - turned upside down for me. On the contrary, it meant that even formal, purely technical elements should be filled with my energy, reflect my individuality.

I carefully studied my movements - from high jumps to subtle gestures - and tried to understand their origin.

overstretched porte de bras in arabesque - the iconic ballerina pose - stupefied me: it upset my balance, but I was convinced that it looked beautiful. Where did the integrity of the element come from: from my chest, my standing leg, or my fingertips? Previously, things that manifested as muscle contractions, trembling, or involuntary movements were actually under my control, but they have a long history of origin, which I decided to study. I used to tense my toes unnecessarily, even when I didn't need to balance. I intentionally “dropped out” of the additional turn, although I would have had enough strength for one more rotation. I thought that the way I looked down was a stylistic device, in fact, at that moment I was following the movement of my legs. I began to look at the dance and relate to it differently, both to my own and to the performances of other artists. The most elementary movements, gestures and steps can convey an immensely wide range of textures, emotions, feelings. Tandyu (a kind of batman, in which the leg is alternately retracted back, to the side or forward, while the toes of the working leg are pointed to the floor), as I noted, it did not reflect the arch of my foot, but the resistance of the floor.

Where did the integrity of the element come from: from my chest, my standing leg, or my fingertips? Previously, things that manifested as muscle contractions, trembling, or involuntary movements were actually under my control, but they have a long history of origin, which I decided to study. I used to tense my toes unnecessarily, even when I didn't need to balance. I intentionally “dropped out” of the additional turn, although I would have had enough strength for one more rotation. I thought that the way I looked down was a stylistic device, in fact, at that moment I was following the movement of my legs. I began to look at the dance and relate to it differently, both to my own and to the performances of other artists. The most elementary movements, gestures and steps can convey an immensely wide range of textures, emotions, feelings. Tandyu (a kind of batman, in which the leg is alternately retracted back, to the side or forward, while the toes of the working leg are pointed to the floor), as I noted, it did not reflect the arch of my foot, but the resistance of the floor. Ranversé (strong, sharp twist of the body in a large pose) - my favorite step - was not just a figure that I could perform with my arms and legs, but an expression of my back moving forward in space. Instead of striving for external weightlessness and airiness, I began to practice surrendering to the force of gravity and using the force of my weight.

Ranversé (strong, sharp twist of the body in a large pose) - my favorite step - was not just a figure that I could perform with my arms and legs, but an expression of my back moving forward in space. Instead of striving for external weightlessness and airiness, I began to practice surrendering to the force of gravity and using the force of my weight.

These qualities, which formed the artistry of a dancer, became the source of my inspiration. Thus, dance was my practice of independent and critical reflection on the goals achieved, the habits formed, on the core values and beliefs that I adhered to not only in dance, but also in those areas where I wanted to develop. It was that moment of realization that my education as a dancer and as a scientist had found common ground and had become an integral way to explore ideas about personality and well-being. The knowledge that I received as a dancer was the physical embodiment of the ideas of freedom and independence that I comprehended as a political theorist. My dance experience was a daily, real, and most importantly, physical experience of what it means to be able to control someone's life, change it, and view those possibilities "as evidence of the strength, not the fragility" of our fundamental identity, as Rob Rye says of this in his book "Overcoming liberalism and multiculturalism in education" ( 2002).

My dance experience was a daily, real, and most importantly, physical experience of what it means to be able to control someone's life, change it, and view those possibilities "as evidence of the strength, not the fragility" of our fundamental identity, as Rob Rye says of this in his book "Overcoming liberalism and multiculturalism in education" ( 2002).

We learn when we try , as American dancer and choreographer Martha Graham once said. Our experiments with our abilities - whether physical or intellectual - can be much more useful than routine work and habit formation. By choosing to perform "specific sets of precise actions", we can access "achieving a sense of our being and satisfaction of the spirit" . We embody our independence and humanity.

This article was first published on April 3, 2020 in Aeon magazine under the title "How dancing helps me think, and thinking helps me dance" .

Cover prepared by Veronika Morozova | Behance

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter .

translationspsychology

Related articles

What scientists know about dance

On April 29, people around the world celebrate International Dance Day. About what type of dance is best for retirees, why flamenco will not help much with weight loss, and whether dancers need painkillers, says the science department of Gazeta.Ru.

Many people see dancing as more than just a hobby or a professional sport. Often we start dancing to get in good physical shape, without resorting to visiting a sports club and exhausting walking on a treadmill. Numerous scientific studies show that dancing really has a positive effect on the physical and psychological state of a person.

First of all, dancing has an extremely positive impact on health, regardless of gender and age. Physiologists from the University of Illinois at Chicago conducted experiment , during which 54 elderly participants practiced Latin American dances twice a week for four months.

How to achieve results in the gym

Whether athletes should drink milk, why men rarely attend group training, is it possible to go to ...

Mar 08 11:51

Prior to testing, scientists measured the time it took subjects to walk a 400-meter distance. Before the experiment, the participants were not very physically active, and as part of the dance program, they had to attend classes in salsa, cha-cha-cha, bachata and merengue.

The study found that the participants took 10% less time to walk the 400-meter walk than before the experiment, and their overall physical activity increased, which reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and type 2 diabetes.

In the future, the researchers want to check, using MRI, how positively dancing has an effect on human brain activity.

A similar study, published in the European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, was carried out by scientists from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. It turned out that Greek dance (for example, sirtaki) helps older people with heart failure become more physically resilient. Zacharia Vordos, one of the authors of the paper, suggested that such "dance therapy" could attract more patients than traditional treatment programs.

It turned out that Greek dance (for example, sirtaki) helps older people with heart failure become more physically resilient. Zacharia Vordos, one of the authors of the paper, suggested that such "dance therapy" could attract more patients than traditional treatment programs.

Scientists also claim that partner dancing can have an effect on a person similar to that of an anesthetic. In the journal Biology Letters , a study was published in which biologists measured the amount of endorphins formed in the blood of people after dancing. They found out,

the more difficult the dance movements were and the more synchronization of actions the dance required, the more “hormones of joy” were in the blood of the participants.

How the body resists sport

The nervous system leads the body's resistance to active sports and weight loss, scientists have found out...

September 14 09:06

Researchers attribute this to the fact that in addition to the pleasure of a correctly performed dance element, people feel a social connection, which, in turn, also affects the concentration of endorphins.

It is obvious that dance is different and many people who are eager to practice this sport are faced with the choice of their style. American scientists agreed on that hip-hop is the healthiest dance. The fact is that dance classes do not always involve active physical activity. Using accelerometers (portable electronic counters of the number of movements), scientists measured the physical activity of 264 girls aged 5 to 11 years old, involved in 66 different dance classes. A study published in the journal Pediatrics found that children spend an average of 17 minutes of active exercise and spend the rest of the activity, which usually lasts about an hour, listening to music and doing quiet exercises or stretching.

Flamenco turned out to be the most “inactive” of the seven types of dances studied: the children involved in it moved only 14% of the time. In hip-hop classes, the children devoted about 57% of the time to increased physical activity.

Today there are a huge variety of dance styles, some of which are known to relatively small groups of people. For example, in South Korea there is a musical genre called K-pop, which has absorbed elements of Western electropop, hip-hop, dance music and modern rhythm and blues. Thanks to the Internet, Korean pop culture has spread to parts of Southeast Asia, and an entire dance genre, K-pop, has been born. Korean engineers from Pohang University of Science and Technology developed the virtual K-pop dance teacher, which allows you to track the movements of the 15 joints of the human body and thus make it easier to learn dance at home.

For example, in South Korea there is a musical genre called K-pop, which has absorbed elements of Western electropop, hip-hop, dance music and modern rhythm and blues. Thanks to the Internet, Korean pop culture has spread to parts of Southeast Asia, and an entire dance genre, K-pop, has been born. Korean engineers from Pohang University of Science and Technology developed the virtual K-pop dance teacher, which allows you to track the movements of the 15 joints of the human body and thus make it easier to learn dance at home.

“Sport is a human “space”

The coming year 2016 is rich in sporting events: the Olympics, the European Football Championship... Why is sport...

January 11 12:52

Deijin Kim and colleagues presented the development at the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP) in 2015. To create the "trainer", the team took 100 K-pop moves performed by a professional dancer and recorded the changes in the position of his joints. Then, using 3D tracking technology, they checked how similar the movements of an aspiring dancer and a professional choreographer are.

Then, using 3D tracking technology, they checked how similar the movements of an aspiring dancer and a professional choreographer are.

Another type of dance, previously unknown to almost anyone, but which has made a lot of noise over the past few years, is twerk. By the way, the word itself is not something new - linguists found in the 1820 edition of the Oxford Dictionary the word twirk , denoting twitching movements. The verbal form of the word was found in the dictionary of 1848, and in the current form ( twerk ) the word appeared in 1901.

The dance itself is an active movement of the hips, buttocks, abdomen and arms, and the word "twerking", denoting a dance direction, appeared in the dictionary in 2013.

Fiona MacPherson, senior editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, commented: “We were convinced that the word twerk was rooted in twist and jerk (“twitch”). However, the presence of earlier origins in the name of the dance surprised us.