How can a deaf person dance to music

how the brain helps a person dance to music they can't hear

This year’s series final of Strictly Come Dancing will feature actor Rose Ayling-Ellis. Ayling-Ellis is the show’s first ever contestant who is deaf. She has wowed Strictly viewers throughout the series and achieved excellent scores from the judges. But how is it possible that a person who is deaf can dance to music they can’t actually hear?

Deafness or hearing loss usually involves a problem with the ear. In the ear, tiny hair cells convert soundwaves into electrical signals that travel to the brain. If these electrical signals are missing or reduced, the hearing parts of the brain will not be able to fully understand sound.

But the brain is an excellent problem solver. If sound is missing, it will use other sources of information to understand what’s happening around us. What a person sees, and vibrations felt through the body, can be particularly helpful sources of information for those who are deaf or hearing-impaired.

Read more: Are some brains wired for dance?

To learn how to dance, the brain views the actions of others moving to music and combines this with careful counting. Many people without hearing loss also do this when learning a dance – the steps are taught to beats or counts, which are then practised before being put to music. For someone with hearing loss, while the appreciation of the music differs, the learning through observation and counting is similar.

In addition, the tactile information provided through music is very helpful for people with hearing loss. Instead of listening to music, a person who is deaf may feel the music, literally sensing the vibrations through their body.

A process called cross-modal neuroplasticity also helps a person who is deaf to be able to dance to music. The brain is remarkably adaptable and will “repurpose” any brain areas that are not being used. So, if the hearing areas of the brain are not being used for responding to sound because a person is deaf, these parts of the brain may instead respond to other things, such as visual or tactile information.

Technologies like sensory substitution devices can further assist people with sensory loss. Sensory substitution is a technique where missing sensory information is converted into an alternative sense, to help people who are deaf or blind better understand the world around them.

One example is a vibrating vest that allows people who are deaf or have hearing loss to feel sound through their skin. The vest contains a microphone which picks up sound. The technology in the vest converts the sounds into vibrating patterns that the wearer can feel on their torso.

Read more: Strictly Come Dancing: research shows that the luck of the draw matters in talent shows

As the brain is so adaptable and “plastic”, after some training to understand which vibrating patterns match with which sounds, people with hearing loss can experience the auditory world in a new way. Although we haven’t seen Ayling-Ellis use this kind of technology on the show, similar devices have been used by dancers with hearing problems.

Ayling-Ellis is not the only well-known figure to highlight the remarkable capability of a brain struggling to hear. Composer Ludwig van Beethoven developed severe hearing loss in mid-life, and seemingly used vibrational information in music to help him continue to compose.

As his hearing deteriorated, he is reported to have favoured a piano constructed in such a way that the sounding board was connected to the outer frame, which conveyed powerful vibrations to Beethoven’s fingers and through the floor to his feet. These vibrations were further amplified through a metal resonator that Beethoven placed on his pianos.

These examples highlight the remarkable problem-solving capability of the human brain, and the flexibility with which the brain can approach and overcome sensory challenges. Ayling-Ellis is certainly inspiring the nation and showcasing brain plasticity before our very eyes.

What It's Like to Move to Music You Can't Hear

Paul Taylor rather famously never allowed mirrors in his studio, believing they fostered bad habits. But spend a few hours in the studio with Deaf and hard of hearing dancers, and you’ll never look at your reflection in the same way again.

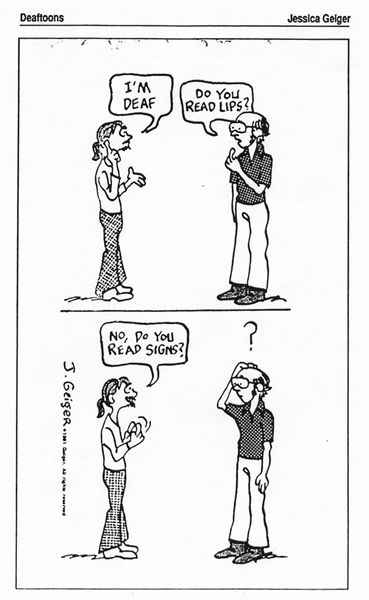

“Some dancers use mirrors just for vanity,” says Lexine Brooks, a Deaf dancer who began training at age 2. For nearly two decades, she’s learned choreography in all sorts of ways, including an FM system that amplified her teachers’ instructions in her ears. Today, she prefers to learn dance through American Sign Language and counting—as well as keeping an eye on the mirror.

Brooks is a member of Gallaudet Dance Company, a 65-year-old performance troupe at Gallaudet University for the Deaf and hard of hearing in Washington, DC. At one fall rehearsal, members spent an hour watching intently in the mirror while choreographer Teresa Dominick, a Gallaudet alum, held her hand high and beat out an eight-count with her fingers. Dominick, fluent in ASL, is able to sign and count at the same time—a top priority for the dancers.

Dominick, fluent in ASL, is able to sign and count at the same time—a top priority for the dancers.

Also possible thanks to studio mirrors: Moving in sync with partners on the opposite side of their V-shape formation once Dominick started up music that not all of the dancers could hear to the same extent.

“Gallaudet Dance Company is no different than other dance groups,” Dominick says. “We just use a different language to communicate and utilize different cues.”

Dance may be a visual art form, but it’s tightly intertwined with sound. Even as the field strives to be more inclusive, learning to dance without two fully functioning ears remains a challenge. But today, dancers with full and partial hearing loss are becoming more visible, thanks to growing opportunities, high-profile role models and even Instagram.

The Drive to Dance

Brooks began dancing for the same reason as many hearing kids: She saw a live performance—in her case Swan Lake—and knew dance was something she wanted to do. But other Deaf children are drawn to dance after feeling left out of team sports. Deaf-from-birth dancer Zahna Simon, who today serves as the assistant director at the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival and the Urban Jazz Dance Company, remembers being in fourth grade, loving movement and struggling to play softball. Then she visited a friend’s ballet class.

But other Deaf children are drawn to dance after feeling left out of team sports. Deaf-from-birth dancer Zahna Simon, who today serves as the assistant director at the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival and the Urban Jazz Dance Company, remembers being in fourth grade, loving movement and struggling to play softball. Then she visited a friend’s ballet class.

“I instantly connected with ballet as I watched the teacher physically demonstrating it, making direct corrections on the students,” says Simon. “I knew I could learn to dance by watching and wouldn’t have to struggle with following conversations.”

She no longer struggled to communicate with teammates, but Simon, like other Deaf dancers, still faced challenges.

Zahna SimonRJ Muna, Courtesy Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival

“My teachers told me early on, ‘You are going to have to work three times harder,’ ” says Annemarie Timling, a Gallaudet dancer who is hard of hearing and trained at North Star Ballet in Fairbanks, Alaska. “I would go home and count through music in my head. And I was always watching, making sure I was in sync with my peers.”

“I would go home and count through music in my head. And I was always watching, making sure I was in sync with my peers.”

From childhood through high school, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s Samantha Figgins trained alongside her twin sister, Jenelle. And when Figgins says “alongside,” she’s referring to years of strategically positioning herself at the barre so that if her deaf right ear was facing the instructor, she could follow her twin sister. At home and after class, Jenelle (now with Aspen Sante Fe Ballet) would review combinations with her.

“Jenelle was my angel,” Figgins says. “I wouldn’t be the dancer that I am today without her.”

Still, Figgins worried about appearing antisocial to her fellow dancers, when in reality, she never snickered in class because she couldn’t hear other dancers’ jokes. She also knew that if she lost her place, it would be nearly impossible to catch up.

“I have to stay laser-focused and make sure I’m not distracted,” she says. Figgins believes that sense of hyper-focus has ended up being the key to her professional career.

Figgins believes that sense of hyper-focus has ended up being the key to her professional career.

Making Space for Deafness

San Francisco dancer Antoine Hunter used to encounter people who would claim that he was the only Deaf dancer. “I would tell them there are others, but we are not given opportunities to show our artistry,” Hunter writes in an email. So in 2013, he founded what’s now known as the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival. “I wanted Deaf artists from all over the world to have a safe place to learn and perform.”

Each year, guests hail from as far away as Colombia, India, Russia and Taiwan for three days of workshops, panels and performances.

“We know firsthand what it’s like to be rejected from the world,” says Simon. “With the festival, our goal is that no one feels that way.”

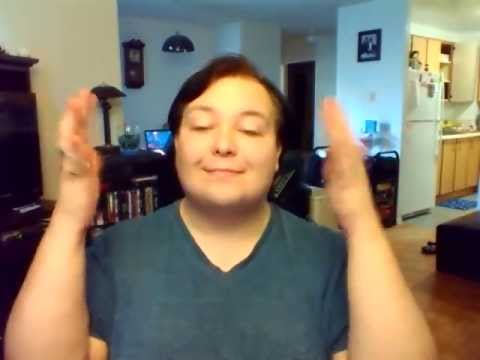

Although the festival highlights performers working in many genres, hip hop has become especially in-demand, in part because it’s in vogue to fuse footwork with ASL. One popular 2019 workshop was taught by Deaf ASL interpreter Matt Maxey, a viral YouTuber who has gone on tour with Chance the Rapper. Maxey not only signs with his hands, but gestures with his full body, shoulders curving forward whenever he wants to especially emphasize a phrase rapped by the likes of Kendrick Lamar.

One popular 2019 workshop was taught by Deaf ASL interpreter Matt Maxey, a viral YouTuber who has gone on tour with Chance the Rapper. Maxey not only signs with his hands, but gestures with his full body, shoulders curving forward whenever he wants to especially emphasize a phrase rapped by the likes of Kendrick Lamar.

Deaf hip-hop performer Shaheem Sanchez has also amassed more than 400,000 Instagram followers by smoothly integrating signing with full-body movement. He lost his hearing at age 4 and relies on the music’s vibrations to phrase his dancing. He has also experimented with a high-tech backpack called a SubPac, a tactile audio system which transfers the energy of music directly to the body.

“The beat makes it flow,” Sanchez writes in an email. “I love feeling the music and integrating sign language into my dancing.”

Big-name artists like Jidenna and T-Wayne pop up in his DMs, making special requests for him to use their songs in his videos. He’s also in demand as a commercial dancer, and appears in Sound of Metal, a new film about a drummer losing his hearing.

Perhaps most importantly, Sanchez is inspiring others in the Deaf community to take up dance—including students at Gallaudet—and has shown that high-profile dancers can make a difference when they go public with their hearing loss.

After years of quiet struggles, two years ago Figgins started opening up about her partial deafness, as well as the residual auditory processing disorder and balance issues—all of her injuries have been on her right side—that complicate her dancing every day.

“I’m trying to acknowledge what I’m living with, and really take ownership of my hearing loss, because it’s opened up opportunities to connect with people,” Figgins says.

Before joining Ailey, she always attempted to “pass” as a hearing dancer in auditions, including when she was hired by Complexions Contemporary Ballet. Three years later, she joined Ailey, but still never shared her struggles publicly during talks and interviews. The turning point came one night on tour with Ailey in Texas, when a fellow dancer mentioned that a girl with hearing loss had attended the performance. Figgins was still backstage taking her makeup off, but she reluctantly agreed to go meet the aspiring dancer and her mother.

Figgins was still backstage taking her makeup off, but she reluctantly agreed to go meet the aspiring dancer and her mother.

“We shared our stories, and that was the first time I realized it was important for me to be vocal about my struggle,” Figgins says. “We were crying, just talking about everything she was going through. I wanted to hug her, and also hug myself.”

During last year’s national Ailey tour, Figgins volunteered to perform for children in special education programs, but she wants to do more for aspiring Deaf dancers. “Maybe a mental health program, maybe a summer intensive. Something to give them tools to succeed.” Figgins says. “I’m working on a lot of things, and I’m still working on myself.”

Samantha Figgins performing in Pas De Duke

Paul Kolnik, Courtesy Ailey

Deciding to Amplify—Or Not

Choosing to augment sound through hearing aids or cochlear implants can be a complex decision, since many in the Deaf community view Deafness as a culture, not a disability. Deaf dancer Heather Whitestone, who performed on pointe when she was named Miss America 1995, faced considerable backlash when she later chose to get implants.

Deaf dancer Heather Whitestone, who performed on pointe when she was named Miss America 1995, faced considerable backlash when she later chose to get implants.

However, many dancers embrace the advances in hearing aid technology. Most members of Gallaudet Dance Company wear hearing aids. “I couldn’t function in a hearing world without them,” says Brooks.

Figgins will never forget the first time she danced Revelations wearing the small devices held in place by a wire loop over each ear.

“I thought they changed the music,” Figgins recalls, laughing. All of a sudden, she could make out individual voices in the opening choral number “I Been ‘Buked.” When she found herself on the left side of the first formation, she could hear her fellow dancers breathe, and during “Wade in the Water,” she discovered a bass line that she never knew was there.

“There’s a different texture and sensitivity to my dancing now,” Figgins says. “It was a real revelation. ”

”

But with the newfound sensitivity has also come a need for more self-care. Figgins continues to reflect on how single-sided deafness has affected her social life and self-esteem, and reserves time for “quiet” moments, when she takes out her hearing aids.

Dancing in silence. Children with Hearing Impairment Learn to Feel Music with Counting - DISLIFE

Archive The sound of the heart, the sound of rain, the voice of the mother - these sounds accompany us from birth. Everything in the world "sounds", has its own voice, music. But imagine that overnight all sounds will disappear, you will stop hearing, you will find yourself in a sound vacuum. Probably, only at this moment you can understand how hearing-impaired and deaf people feel... It is all the more difficult to imagine how they manage to dance. Specialized boarding school No. 4 for deaf and hard of hearing children in the village of Maksakovka is known far beyond Komi. The institution is famous for its strong mathematical base, as well as the children's creative group "Joy", whose members have repeatedly become laureates of all-Russian competitions.

The institution is famous for its strong mathematical base, as well as the children's creative group "Joy", whose members have repeatedly become laureates of all-Russian competitions.

Metronome to help

Children with hearing impairments end up in boarding school: some of them can partially restore their hearing thanks to a hearing aid or cochlear implant, which is implanted under the skin behind the ear. Other pupils of the boarding school are absolutely deaf. Often hearing problems in children are accompanied by concomitant diseases (mental retardation, cerebral palsy).

“Children come to us at the age of six,” says Lydia Yakimova, teacher of music and rhythm classes and head of the Joy group. - We teach them to literally feel the music.

In the rhythm class, in addition to many musical instruments: tambourines, rattles, xylophones, wooden spoons, bells, I see a metronome. "What is he here for?" - I'm interested in Lydia Vitalievna. According to her, with the help of this device, deaf children are taught to feel the rhythm. This is a clear tempo guide that helps memorize lyrics. The teacher sets the pace of the metronome individually, gradually increasing it.

This is a clear tempo guide that helps memorize lyrics. The teacher sets the pace of the metronome individually, gradually increasing it.

We go to the choreography hall. Teacher Natalya Andreeva conducts a lesson with the smallest. The group consists of children 6-7 years old. Much that for ordinary children will not be difficult, students of the Maksakov boarding school are given with difficulty. At the lessons of phonetic rhythm, children are taught to clap musical passages with their hands, stomp, march in sync.

Demonstrate songs with hands

Loud music plays in the hall. But its function is not actually sound, but mostly rhythmic. Children are taught to feel the rhythm with their bodies! In the first lessons, the children put their palm on the music column, and then sit down on it. Thanks to the bass, the guys feel the music inside themselves. During the dance in the hall, an acoustic system (subwoofer) is turned on, the vibration from which is transmitted along the floor. At the same time, the musical equipment is carefully tuned so that, surrounded by many sound waves, the ear apparatus does not cause discomfort to children.

At the same time, the musical equipment is carefully tuned so that, surrounded by many sound waves, the ear apparatus does not cause discomfort to children.

- It is important to teach children the musical meter, the knowledge of which will not allow them to go astray in music. With it, you can learn dance, - says Natalya Andreeva, teacher of phonetic rhythm, choreographer.

Phonetic rhythm classes help children develop the muscles of the body, face, which positively affects the fluency and pace of speech, helps to correctly stress the words, straightens the gait and posture of children.

Such complex work gives good results: the guys dance in sync and sing with gestures. Gesture singing - combines choreography and singing. With their hands, children can draw the words to almost any song! For children who have minimal vocabulary and good visual memory, this is a great opportunity for creative expression.

Nine-year-old Roma was diagnosed with deafness, cerebral palsy. When the boy entered the boarding school four years ago, he did not know how to hold the ball in his hands. Now, along with physically healthy peers, he rhythmically claps his hands, jumps, dances, takes part in the holidays.

When the boy entered the boarding school four years ago, he did not know how to hold the ball in his hands. Now, along with physically healthy peers, he rhythmically claps his hands, jumps, dances, takes part in the holidays.

Variety star

This is the name of a 10th grade student Xenia Dzyuban in a boarding school for hearing-impaired and deaf children. “Ksyusha came to us when she was three years old. It was immediately noticeable that the girl is very plastic and feels the rhythm perfectly. This is a gift from God,” says teacher Lidia Yakimova.

Xenia has a good intellect, good visual memory, artistry. The girl easily remembers the movements and conveys them emotionally in the dance.

In 2010, at the festival of sign singing "Singing Hands", Ksenia Dzyuban took 1st place in the nomination "Solo Performance" for the performance of the composition "Victory Waltz" and 1st place in the nomination "Musical Duet" for the composition "Lady", performed jointly with Evgenia Shelyuzhak.

According to Ksyusha, most of all she likes modern pop music: “Dance lifts the mood, you can pour out your soul in it,” explains the graduate. - I like to dance at home, at school in a disco.

The girl performs at all holidays and concerts of the boarding school, performs at events at the Gymnasium of Arts under the Head of Komi. Mom and dad do not miss a single performance of their daughter.

This year Ksyusha is finishing her studies at the boarding school and is preparing to enter. She dreams of becoming a laboratory assistant: “The main thing is that chemistry does not fail,” our heroine smiles.

By the way

Exclusive inclusive dances

In the early 2000s in Ukhta, members of the city organization of the disabled and students of the local technical school organized a dance group "Duet". The uniqueness of this ballroom dance ensemble was that three participants - two girls and a young man, moved in wheelchairs. Each couple had a non-disabled partner.

Galina Zaborshchikova, one of the best trainers of the Republic of Komi, worked with the guys for several years. She put on numbers for the children, which were successfully received by guests of many city holidays, including a student ball. Subsequently, two of the members of the "Duet" created a family.

At the end of March this year in Syktyvkar a seminar "Inclusive Dances: Dance Rehabilitation" was held. Based on its results, it was decided to organize inclusive dance studios in the Komi capital.

Anastasia Pozdeeva

Deaf people found the ability to perceive music

September 21, 2017, 15:44

The fact that hearing impaired and deaf people perceive sound poorly or not at all does not mean that they do not show interest in music - this is evidenced by the increasingly popular musicals and rap battles in sign language. However, people are still limited in their ability to attend mass music events, writes BuzzFeed.

According to the US National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disabilities, approximately 90% of deaf children have hearing parents, but only a few learn ASL (ASL, the main language in deaf English-speaking communities) and often do not think that the absence the opportunity to attend a musical event further isolates them from society.

Concerts and music festivals are a popular way for millennials to socialize and spend their leisure time. This is an opportunity to see bands on stage and share experiences with a community of like-minded people from which young people with hearing impairments do not want to be excluded.

"For me, music is not a sound, it's a physical sensation," says Lisa Cryer, a fully deaf BuzzFeed interviewer. "I hear through my eyes and my body." At the American festival Lollapalooza, she stands at the speakers and leans on the metal railing of the stage; for a hearing person, the volume is unbearable, but Lisa does not perceive it, feeling only the vibration from the bass.

A deaf music lover can feel music with an ordinary empty water bottle or any container that also transmits vibration. Hearing-impaired concert goers tend to get in the front rows to stand or sit next to the speakers: that's the only way they can hear the vocals.

As BuzzFeed points out, historically the community of deaf and hard of hearing music fans who wanted to gain independence "in the hearing-centric music world" have tried various ways to gain access to it. They began to hold their own specialized festivals - BrickFest, Louisville's DeaFestival Kentucky and San Antonio's Good Vibrations. At dance parties where music is played with strong bass, DJs familiar with the characteristics of the hearing-impaired people try to turn the speakers to the floor, and not put them on top, as usual. Deaf musicians and entrepreneurs are developing Bluetooth-enabled devices in the form of vests, backpacks and wristbands that can be synchronized to the beat of the music.

Despite these innovations, Cryer notes that most concert halls and festivals do not have access points for the deaf. Cryer insists that sign language interpreters and designated seats should be available at every music festival, as was done for wheelchair users: this is required by law, regardless of whether the organizers know in advance about possible hearing-impaired visitors or not.

Cryer insists that sign language interpreters and designated seats should be available at every music festival, as was done for wheelchair users: this is required by law, regardless of whether the organizers know in advance about possible hearing-impaired visitors or not.

For many fans of certain artists, it is important to hear the lyrics, but having a sign language interpreter at the festival is the exception rather than the rule.

"If I want to go to a concert, I have to plan ahead: ask for access, hope they find people to help me, hope they're qualified," complained Lisa. "I can never just buy last-minute tickets or just to join friends: it takes a long time and is not easy to do, which is annoying because US disability law requires concerts to be accessible to everyone."

In the meantime, thanks to the concerted efforts of deaf and hard of hearing community advocates, after 2014, major festivals began to create accessibility programs for guests with hearing disabilities and provide special places for them. Since 2015, priority access has been introduced for deaf and hard of hearing fans. In 2017, a sign language interpreter was present for a fifth of the 170 performances at the Lollapalooza festival. In June of that year, American hip-hop artist Chance the Rapper announced that he had hired a team of sign language interpreters for the remainder of his tour, which would include stops at major festivals.

Since 2015, priority access has been introduced for deaf and hard of hearing fans. In 2017, a sign language interpreter was present for a fifth of the 170 performances at the Lollapalooza festival. In June of that year, American hip-hop artist Chance the Rapper announced that he had hired a team of sign language interpreters for the remainder of his tour, which would include stops at major festivals.

In Russia, 13 million people have hearing impairments, 250 thousand of them are partially or completely deaf, and the same problems are relevant for them as in the USA: despite the fact that the world's first Theater of Mimicry and Gesture for deaf people appeared it is in Moscow that musical events adapted for the deaf are a rarity in Russia; sign language interpreters accompany the performances of artists, mainly at specialized festivals.

"Among the cultural practices that are unique to the "culture of the deaf", the most popular is attending performances in sign language at the Theater of Mimicry and Gesture, the Specialized Academy of Arts, and so on. About 35% of respondents noted that they had been to these performances more than twice over the past year, and more than 40% attended performances 1-2 times over the past year.In addition, people with hearing impairments attend concerts with the participation of deaf and hard of hearing artists and performers, as well as specialized events on average 1-2 times a year (festivals, concerts, competitions) for the deaf and hard of hearing in Moscow parks,” the authors of the study “Patterns of Cultural Consumption of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing: Inclusion or Isolation?” Nadezhda Astakhova and Nikita Bolshakov in the Journal of Social Policy Research.

About 35% of respondents noted that they had been to these performances more than twice over the past year, and more than 40% attended performances 1-2 times over the past year.In addition, people with hearing impairments attend concerts with the participation of deaf and hard of hearing artists and performers, as well as specialized events on average 1-2 times a year (festivals, concerts, competitions) for the deaf and hard of hearing in Moscow parks,” the authors of the study “Patterns of Cultural Consumption of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing: Inclusion or Isolation?” Nadezhda Astakhova and Nikita Bolshakov in the Journal of Social Policy Research.

At the same time, 30% of the deaf and hard of hearing are active visitors to performances and concerts, and more than 60% of people with hearing impairments would like to visit them more often.

Since 2009, the World of the Deaf festival has been held in Moscow. The event is timed to coincide with the World Day of the Deaf and is organized by the Peace and Love Charitable Foundation. One of the permanent partners of the inclusive festival is the Russian mobile operator VimpelCom (provides services under the Beeline trademark). Since 2006, the company has been developing mobile technologies and special applications that can be useful for people with hearing and vision impairments.

One of the permanent partners of the inclusive festival is the Russian mobile operator VimpelCom (provides services under the Beeline trademark). Since 2006, the company has been developing mobile technologies and special applications that can be useful for people with hearing and vision impairments.

"In our work to introduce assistive mobility solutions into everyday life, we pay special attention to the need to break stereotypes. For example, every year we tell and show at our festival how musical and receptive to music deaf people can be. Our festival of the deaf is absolutely musical "It consists of songs (accompanied by translation into sign language), dances in which deaf dancers take part. The festival is equipped with a special dance floor that can transmit vibrations," Evgenia Chistova, head of Beeline social projects, told "+1". how many stars of the first magnitude agree to take part in the festival. This is all propaganda of a healthy attitude of society towards this topic.