How ballet dancers move

The 7 Movements of Dancing – Everyday Ballet

The 7 Movements of Dancing

February 5, 2015

[et_pb_section admin_label=”Section” fullwidth=”off” specialty=”off”][et_pb_row admin_label=”Row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”post copy” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” text_font_size=”16″]

Ballet is often regarded as the most precise and difficult dance form in western culture. Though ballet includes hundreds of specific steps, the technique is based upon seven fundamental movements of the body. Ballet terms are French (a few are Italian) because the French were the first to codify ballet technique. The Académie Royale de L’Danse was formed in Paris in 1661 by Louis XIV to teach courtiers to dance and prepare ballets for the court. Below are the seven movements that provide the basis of ballet pedagogy.

- Plier [plee-AY] means “to bend” and describes the bending of the knees. Pliés are typically the first exercise performed at the barre. The plié is the single most pliè in first position

important step in ballet because it allows the knees and ankles to absorb the force of the movements in a fluid, spring-like way that makes dancing look elegant and effortless.

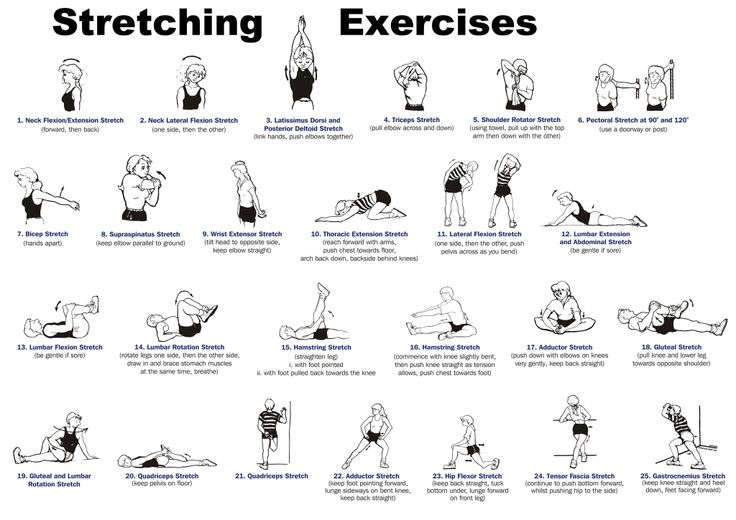

- Étendre [ay-TAHN-druh] means “to stretch” and describes the stretching of the toe, ankle, and knee, resulting in the ballet aesthetic of a straight leg with a pointed toe. Tendu [tahn-DEW] or “stretched” exercises typically follow pliés and are critical for developing foot and leg strength.

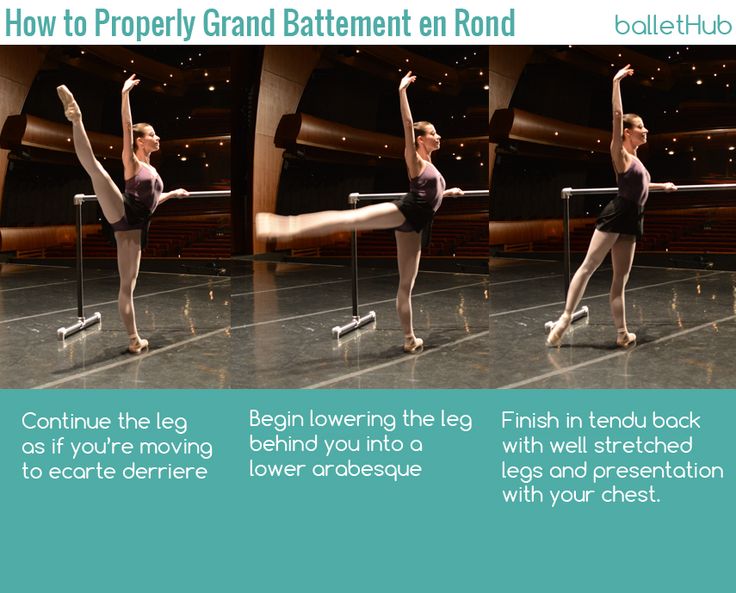

- Glisser [glee-SAY] means “to glide” and describes the sliding movement of the feet against the floor. Just like ice-skating, a smooth brushing of the foot propels the leg smoothly into extension and off of the ground.

- Relever [ruhl-VAY] means “to rise” and describes the lifting of the heels off the ground to balance on the ball of the foot. Women may also rise to the tips of their toes if they are wearing pointe shoes. Relevés build strength in the entire body but especially the foot, ankle, and calf muscles. A beautifully executed relevé can produce the effect of floating.

- Sauter [soh-TAY] means “to jump” and is the natural progression from the relevé. The dancer pushes off from plié into the air, leaving the floor with pointed toes and extended legs. But the truly difficult part of a sauté is landing softly and quietly, which takes tremendous strength and control (and years!) to master.

- Tourner [toor-NAY] means “to turn around” and describes any turning of the body.

Turns can be done in place, across the floor, or in the air. A pirouette (whirl or spin) is done on one leg. pirouette sur les pointes

Turns can be done in place, across the floor, or in the air. A pirouette (whirl or spin) is done on one leg. pirouette sur les pointes

- Élancer [ay-lahn-SAY] means “to dart.” Movements done élancé are done in a darting manner along or just above the surface of the floor with strongly stretched legs and pointed toes. This term most often relates to jumping along rather than up.

This short list leaves out one of the most iconic qualities of ballet movement—the beautifully slow and sustained grace of the adagio. Ad agio is an Italian term that means “at ease.” In ballet, an adagio is the opening of a classical pas de deux. It also describes a set of slow and fluid movements, usually balancing for periods of time on one leg. In reality, slow moving grace is anything but easy! Yet practicing the seven movements described above build the necessary strength, coordination, and control to move fluidly at any tempo. So the next time you think that learning ballet is like drinking from a fire hose, it may help to remember that you’re really working towards perfecting the seven movements.

So the next time you think that learning ballet is like drinking from a fire hose, it may help to remember that you’re really working towards perfecting the seven movements.

Happy Dancing!

Tiekka

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_divider admin_label=”Divider” color=”#cccccc” show_divider=”on” divider_style=”solid” divider_position=”top” hide_on_mobile=”on”] [/et_pb_divider][et_pb_signup admin_label=”Email Optin” provider=”mailchimp” mailchimp_list=”118c17a147″ aweber_list=”none” title=”Everyday Ballet In Your Inbox!” button_text=”Subscribe Today!” use_background_color=”on” background_color=”#f986a5″ background_layout=”dark” text_orientation=”left” use_focus_border_color=”off” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” custom_button=”off” button_letter_spacing=”0″ button_use_icon=”default” button_icon_placement=”right” button_on_hover=”on” button_letter_spacing_hover=”0″ body_font_size=”17″ saved_tabs=”all”]

Subscribe to the Everyday Ballet newsletter and get weekly free EDB workouts, tips, nutritional advice and style-counsel from Everyday Ballet.

[/et_pb_signup][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

The Most Difficult Moves in Ballet

By Move Dance on 13th Jun 2019

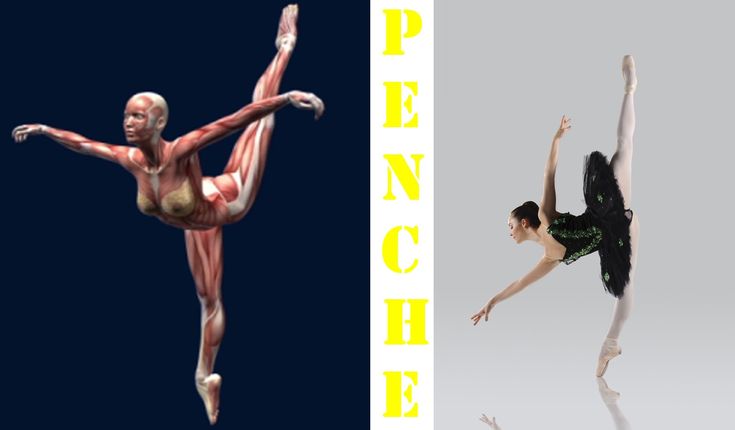

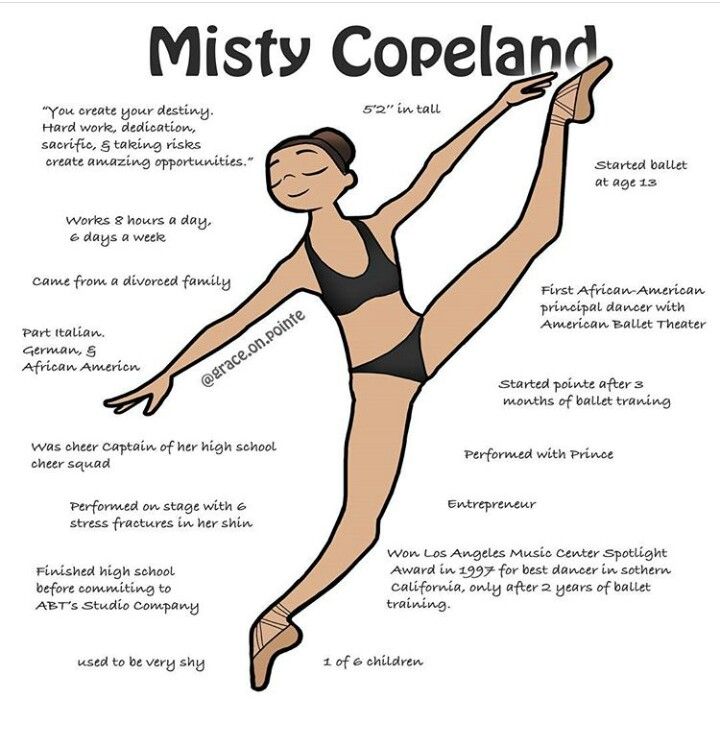

Ballet is one of the hardest art forms to accomplish, it takes dancers many years to be satisfied with certain moves, steps and jumps. The dance as a whole is incredibly difficult, however, there are certain moves that take a lot of extra time and practice to perfect. The end result makes ballet may look graceful and effortless, but thanks only thanks to the long hours of practice put in beforehand. We’ve put together this list of some of the most difficult moves in ballet.

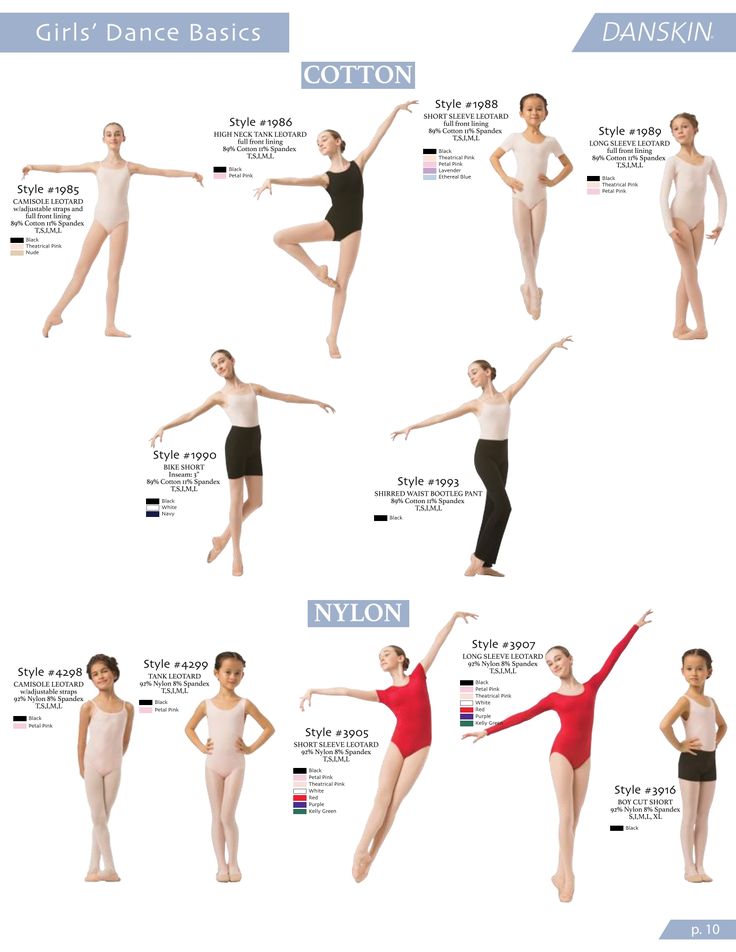

En Pointe

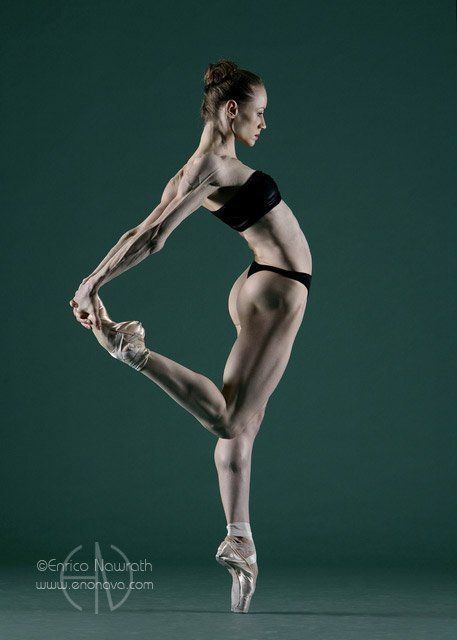

Every ballerina’s dream is to have the best “En Pointe” technique, a lot of training and dedication is necessary to succeed, it takes years for dancers to achieve a technique that they’re happy with. The dancer must support their whole body weight on extended feet. Pointe shoes are worn as the structural reinforcement helps to distribute the weight onto the entire foot instead of only the toes. Pointe shoes also elongate the foot giving a more graceful look, they also give you a better structure with a straighter back. Without pointe shoes it would simply be too painful.

Pointe shoes also elongate the foot giving a more graceful look, they also give you a better structure with a straighter back. Without pointe shoes it would simply be too painful.

Pirouettes

Pirouettes are one of the most commonly known ballet moves, yet, they are extremely hard to execute perfectly. They require balance, technique and like all ballet moves, a large amount of practice. Hours upon hours are spent perfecting this move by dancers, the key is to improve your spotting technique, this gives you balance and control.

Fouette

A fouette is described as a “whipped throw”. The dancer throws their working leg in front or behind their body whilst spinning. It’s one of the most difficult turns in ballet and takes a lot of practice. Swan Lake has 32 fouettes in, imagine how much practice that requires, it is one of the most difficult sequences in any ballet dance.

Swan Lake has 32 fouettes in, imagine how much practice that requires, it is one of the most difficult sequences in any ballet dance.

Colorado Ballet Principal Dancer Sharon Wehner performs “32 Fouettes” from Swan Lake.

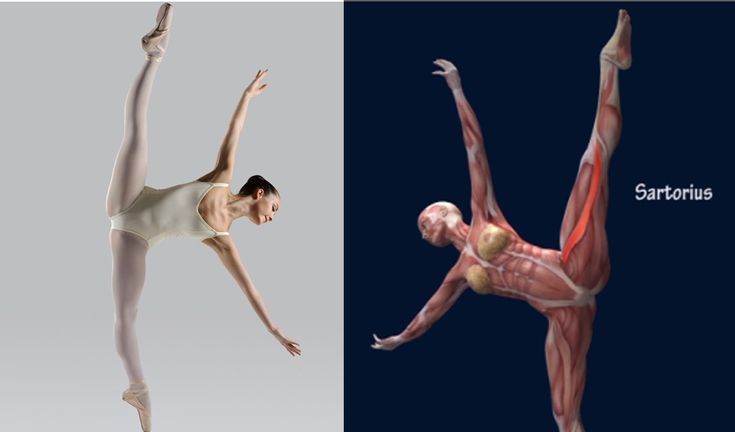

Grand Jete

The Grand Jete is a real crowd pleaser but incredibly difficult to pull off. Composure, balance and technique is essential for this move, the dancer jumps into the air and will do the splits before landing gracefully. It’s vital the dancer lands softly and quietly, a great deal of flexibility is required for this jump.

Watch this video of Mikhailovsky Ballet Company Principal Dancer, Ivan Zayzev, performing a Grand Jete.

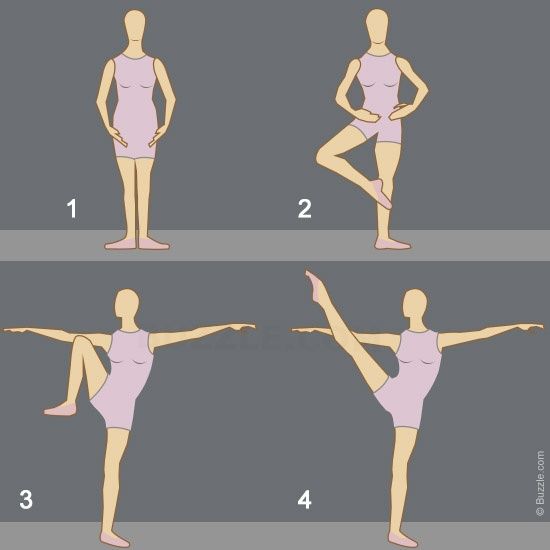

Grand Adage

The Grand Adage may not look as challenging as some of the other moves on this list, but don’t be tricked. This move requires tremendous amounts of strength and control. The dancer swiftly moves their legs forwards, backwards and to the sides without losing their balance. The movements must be strong, slow and steady.

This move requires tremendous amounts of strength and control. The dancer swiftly moves their legs forwards, backwards and to the sides without losing their balance. The movements must be strong, slow and steady.

It’s important for you to remember just how difficult these moves are, making mistakes is a way of learning and getting better. Don’t give up! Even the best dancers take years to succeed these moves, patience and practice makes perfect.

Theatrical dance: ballet

Theatrical dance: ballet

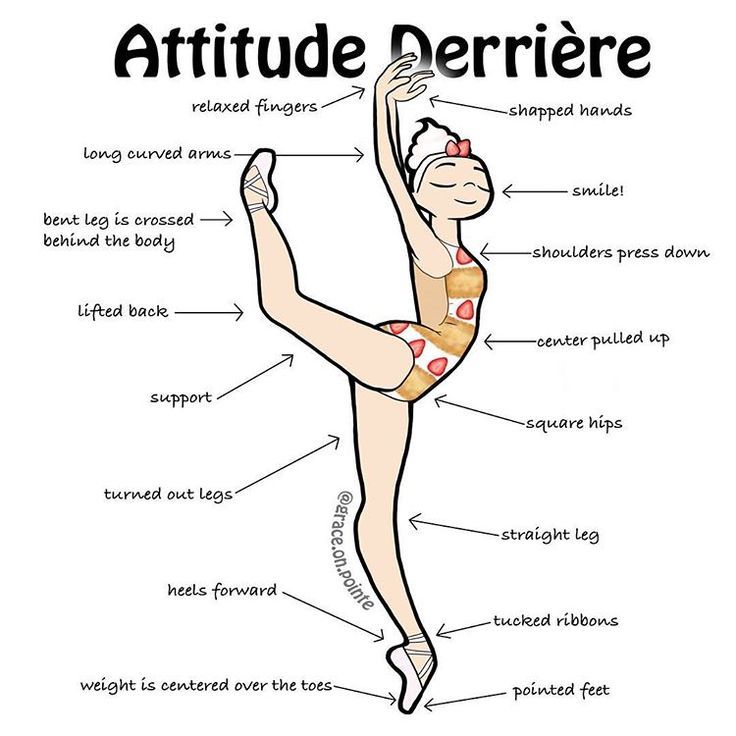

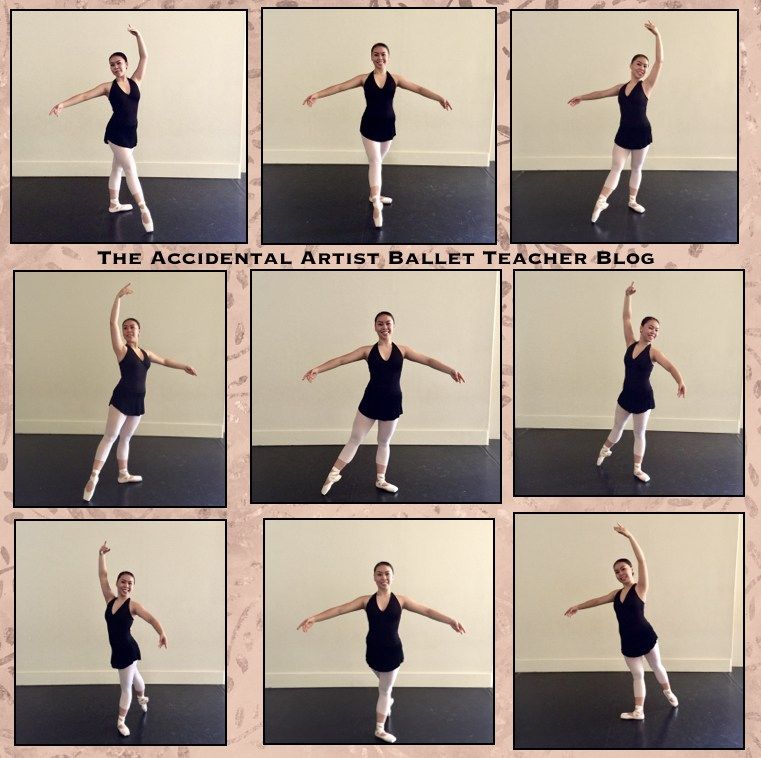

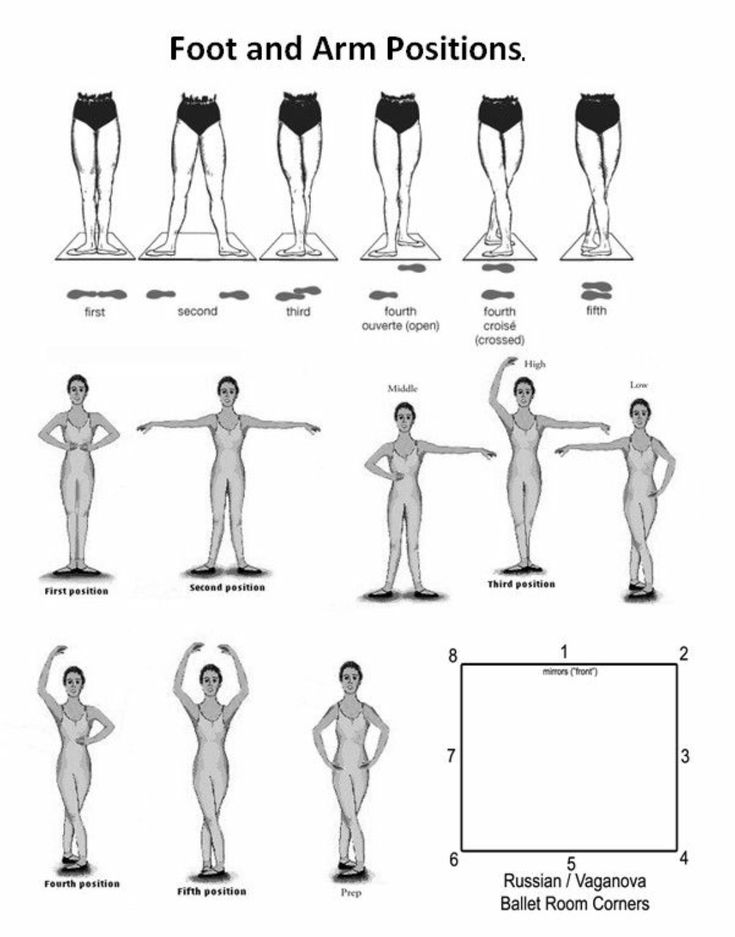

Ballet has been the dominant genre in Western theatrical dance since its inception as an independent form in the 17th century, and its characteristic style of movement is still based on postures and steps developed in court dances of the 16th and 17th centuries. Perhaps the most basic feature of the ballet style is the position of the legs, in which they "turn out" at the hip joints at an angle of 90 degrees, as well as quick turns.

Ballet

If we try to characterize the basic pose of a ballerina in one word, it will be “open”. The reason is that the ballerina's head is almost always raised and her arms outstretched. Even when the dancer takes quick or vigorous steps, her arms rarely move in such a way that these movements are not smooth, calm and graceful, and they are often held in a position that either "frames" the face or forms a harmonious symmetry with the position of the legs. The torso is almost always held straight, with the exception of controlled arching of the back or a slight turn of the shoulders away from the working leg. This positioning of the shoulders, called épaulement, lends "bulkness" and three-dimensionality to the dancer's positions.

Ballet

A ballerina's feet do not always rest on the floor with the whole sole, ballet has such a feature as dancing on the tips of her toes with the help of special shoes - pointe shoes. This gives the dance a special "airiness" and grace. Ballet dancers rarely move near the floor, and often seem to defy gravity with their high jumps and seemingly impossible leg movements and turns in the air. At the same time, it seems that such a dance takes place effortlessly, almost without touching the floor, and one virtuoso movement flows into another. It also gives the dance its characteristic qualities of "performing movements with dignity and with perfect technique", which it inherited from the early court balls, where all movements were intended to show the aristocratic brilliance of the dancers.

Ballet dancers rarely move near the floor, and often seem to defy gravity with their high jumps and seemingly impossible leg movements and turns in the air. At the same time, it seems that such a dance takes place effortlessly, almost without touching the floor, and one virtuoso movement flows into another. It also gives the dance its characteristic qualities of "performing movements with dignity and with perfect technique", which it inherited from the early court balls, where all movements were intended to show the aristocratic brilliance of the dancers.

Ballet

Of course, ballet has undergone many stylistic changes. The Romantic style, popular from the early to mid-19th century, was much softer and featured far fewer virtuosic leaps and turns than the classical style of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Often considered the paradigm of the classical school, Russian ballet is itself a mixture of the soft and decorative French school, the more fragile and virtuosic style of the Italians, and the energetic athleticism of Russian folk dances.

Ballet

Classical ballet design is traditionally symmetrical in the forms created by the dancers' bodies, their position on the stage, and even in the structure of the entire dance. For example, if the two main dancers perform a pas de deux (dance for two), the other dancers on the stage remain still, stand symmetrically away from them, and do not interfere with the main line of the dance. Even when large groups of dancers move, they are usually arranged in a line or in a circle. Jean-Georges Nover in the 18th century and Mikhail Fokine in the first decades of the 20th century argued that such formal symmetry was detrimental to the dramatic naturalism of the ballet. Fokine's own choreography encouraged the use of less rigidly regimented "buildings" of dancers, and in Kenneth Macmillan's later dramatic work, groups of dancers in crowd scenes appear completely asymmetrical.

Dance Encyclopedia: From Origins to Postmodernism

19th Century Ballet

Ballet has been the dominant genre in Western dance theater ever since its development as an independent form in the 17th century. His characteristic style of movement was still based on the positions and steps developed in the court dances of the 16th and 17th centuries.

His characteristic style of movement was still based on the positions and steps developed in the court dances of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Perhaps the most basic feature of the ballet style of that time was the position of the legs and feet, in which the legs were turned at an angle of 90 degrees in relation to the body (i.e. feet pointing to the sides). This position gives the body a symmetrical appearance and promotes the high lift of the legs that was typical of ballet. Even when the dancer has taken quick or vigorous steps, his arms rarely move in a non-smooth, calm and graceful manner, and often the dancer will place his arms in positions that either frame the face or simply so that they look in harmony with the position of the legs.

Another feature of the ballet was the vertical position of the body. Ballerinas rarely moved close to the ground. On the contrary, they often seemed to defy gravity with the height of their jumps and energetic "Batterie" (kicking the leg while jumping). Also, the ballerinas amazed the audience with the speed of the turns and the speed of the steps, which seemed to occur without much effort, almost without touching the floor. In ballet, the eternal stress and enormous efforts of the dancers have always been hidden behind the smooth, graceful movements of the dance.

Also, the ballerinas amazed the audience with the speed of the turns and the speed of the steps, which seemed to occur without much effort, almost without touching the floor. In ballet, the eternal stress and enormous efforts of the dancers have always been hidden behind the smooth, graceful movements of the dance.

The ballet, of course, has undergone many stylistic changes. The Romantic style of the early to mid-19th century was much softer, less replete with virtuosic leaps and turns, than the classical style of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Russian ballet is often seen as a paradigm of the classical school, as it is a mixture of the soft and decorative French school, the fragile and virtuosic style of the Italians, and the energetic athleticism of Russian folk dances.

Ballet innovation in the 20th century

The design of classical ballet has traditionally been symmetrical, both in relation to the dancers and their position on the stage and even the structure of the entire dance. For example, if two main dancers were performing a pas de deux (dance for two), the other dancers on stage were positioned symmetrically to them or moved in harmony with the main dance without distracting from it. Even when large groups of dancers performed at the same time, they tended to line up or circle.

For example, if two main dancers were performing a pas de deux (dance for two), the other dancers on stage were positioned symmetrically to them or moved in harmony with the main dance without distracting from it. Even when large groups of dancers performed at the same time, they tended to line up or circle.

Noverre in the 18th century and Mikhail Fokine in the first decades of the 20th century argued that such formal symmetry was detrimental to the dramatic naturalism of ballet. Fokine's own choreography encouraged the use of less rigidly constrained formations in ballet, such as did Kenneth Macmillan, whose crowd scenes often consisted of asymmetrical groups of dancers that rarely seemed "artificial and lifeless."

Fokine's reforms had a great influence on the development of ballet in the 20th century. In particular, in the works he created for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, he showed a range of different dance styles that classical ballet could assimilate, helping to pave the way for more radical innovations. For example, in Chopiniana (1908, later called La Sylphide), which was a virtually plotless ballet reminiscent of early romantic traditions, Fokine created a soft and laconic style that did not contain bravura jumps and turns. The movements of the hands were simple and unchanging, and the formations of the dancers were constantly changing on the stage, giving the production plasticity and "fluidity".

For example, in Chopiniana (1908, later called La Sylphide), which was a virtually plotless ballet reminiscent of early romantic traditions, Fokine created a soft and laconic style that did not contain bravura jumps and turns. The movements of the hands were simple and unchanging, and the formations of the dancers were constantly changing on the stage, giving the production plasticity and "fluidity".

In the ballets "Prince Igor" (1909) and "The Firebird" (1910) Fokine included the energetic style and movements of Russian folk dances. These works showed his talent for organizing large numbers of dancers on stage and turning their previously decorative function into a powerful dramatic force. None of Fokine's ballets lasted more than one act, since he believed that a full-length ballet was essentially useless in terms of choreography, and a production should last only as long as it reveals its theme.

In all his stylistic variations, Fokine's choreography was sustained mainly in classical idioms. Two other choreographers working with the Russian Ballet of Monte Carlo, Vaslav Nijinsky and his sister Bronislava Nijinsky, staged works of a more radical nature. In The Games (1913), Nijinsky was one of the first choreographers to introduce modern themes and contemporary design into ballet. For example, sports movements and modern clothes were included in the ballet. In The Rite of Spring, perhaps Nijinsky's most innovative work, the dancers were organized into large groups and performed abrupt, primitive movements in unison. Unlike Fokine, Nijinsky was ready to arouse even antipathy with his productions, they were so experimental. The audience was as deeply moved by his choreography as they were by the discordant sounds and jagged rhythms of Stravinsky's music.

Two other choreographers working with the Russian Ballet of Monte Carlo, Vaslav Nijinsky and his sister Bronislava Nijinsky, staged works of a more radical nature. In The Games (1913), Nijinsky was one of the first choreographers to introduce modern themes and contemporary design into ballet. For example, sports movements and modern clothes were included in the ballet. In The Rite of Spring, perhaps Nijinsky's most innovative work, the dancers were organized into large groups and performed abrupt, primitive movements in unison. Unlike Fokine, Nijinsky was ready to arouse even antipathy with his productions, they were so experimental. The audience was as deeply moved by his choreography as they were by the discordant sounds and jagged rhythms of Stravinsky's music.

The development of choreography in the first half of the 20th century

In her ballet Les Noces (1923, The Wedding), the main theme of which was taken from the wedding ceremonies of Russian peasants, Bronislava Nijinska created a rather "severe" and highly calculated style of movement. Several raised platforms were set up on the stage, and the dancers often crouched or bent over so that their heads were very low to the floor. Also, the dancers in this ballet were organized into large groups, so that the overall impression was created that there were fewer individual performers on the stage, but rather something whole was moving.

Several raised platforms were set up on the stage, and the dancers often crouched or bent over so that their heads were very low to the floor. Also, the dancers in this ballet were organized into large groups, so that the overall impression was created that there were fewer individual performers on the stage, but rather something whole was moving.

Although there are undeniable similarities between the work of these choreographers and contemporary dance forms that emerged in the 1920s and 1930s, there is little evidence that they had a direct impact on the development of modern dance. The main significance of the works of Mikhail Fokin, Vaslav Nijinsky and Bronislava Nijinsky was that they "brought ballet to the people", abandoning its remoteness from "everything mundane" and its courtly past, starting to use modern themes and plots, and also starting to introduce modern intellectual and artistic influences into the classical art form.

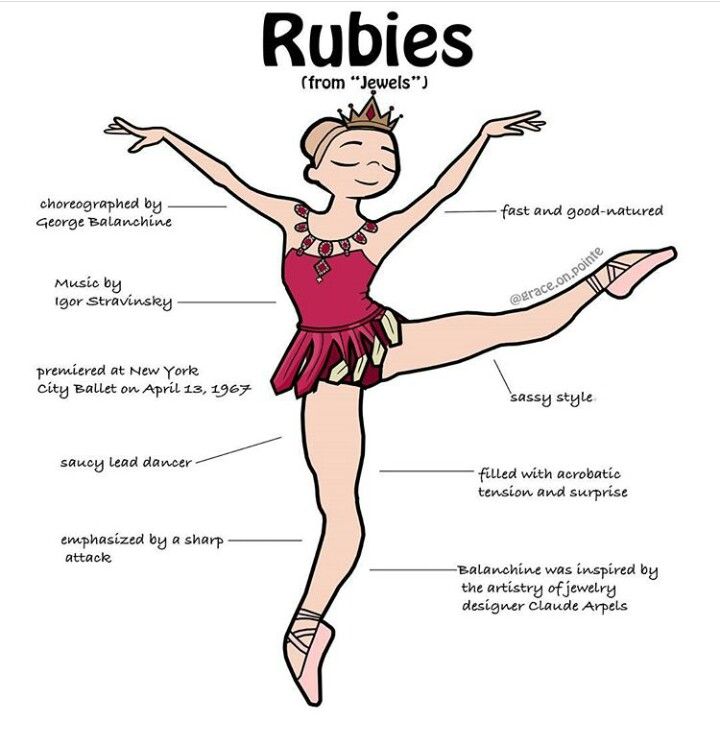

The late ballet style of the 20th century was influenced not only by the Ballets Russes but also by modern dance. It has become common practice for choreographers to expand on the traditional ballet vocabulary with modern dance techniques such as twisting and bending the body or performing the dance close to the floor with bent legs. George Balanchine, influenced by jazz, used syncopated rhythms in his phrasing, and also incorporated steps from popular dances such as ragtime and rock and roll into his ballets. His movements were, as a rule, wide and sweeping, but at the same time they were executed very quickly and clearly.

It has become common practice for choreographers to expand on the traditional ballet vocabulary with modern dance techniques such as twisting and bending the body or performing the dance close to the floor with bent legs. George Balanchine, influenced by jazz, used syncopated rhythms in his phrasing, and also incorporated steps from popular dances such as ragtime and rock and roll into his ballets. His movements were, as a rule, wide and sweeping, but at the same time they were executed very quickly and clearly.

Despite these changes, the ballet retained significant traces of its courtly and classical past. Although there were exceptions, such as those described above, ballerinas still tended to dance in a calm and prim manner, much like their aristocratic predecessors. Illusion and spectacle continued to be important elements of ballet. Almost all productions were performed on the stages of large theaters, where the performers were distant from the audience, and the productions were often very complex and expensive. Therefore, as a rule, ballet troupes were large organizations that received some kind of patronage or government subsidies.

Therefore, as a rule, ballet troupes were large organizations that received some kind of patronage or government subsidies.

Mikhail Fokin

Modern dance - expressionism

One of the main genres of Western dance theater developed at the beginning of the 20th century was modern dance. It arose essentially as a series of reactions to a series of criticisms that had long been subjected to ballet by detractors. They felt that the limited artificial movement style of ballet was far from real dance, and also that its themes were too frivolous.

Expressionism in contemporary dance of the early 20th century

Perhaps the greatest pioneer in modern dance was Isadora Duncan. She believed that ballet technique distorts the natural movements of the body and that "the gymnastic movements of the body have nothing to do with thoughts and feelings", and "the dancers just move like dolls on hinges". Duncan worked with simple movements and natural rhythms, finding her inspiration in the movements of nature, especially wind and waves, as well as in dance forms that she drew from ancient sculptures. The elements that were most characteristic of her dances included the "remote" hand positions, the head raised in ecstasy, the lack of restraint in the expression of emotions, frequent jumps and strong, flowing rhythms in which one movement "flowed" into the next. Her costumes, too, were casual and far from pretentious: Isadora danced barefoot and in a simple loose tunic, with minimal props and lighting effects so that they did not distract the audience from her movements.

The elements that were most characteristic of her dances included the "remote" hand positions, the head raised in ecstasy, the lack of restraint in the expression of emotions, frequent jumps and strong, flowing rhythms in which one movement "flowed" into the next. Her costumes, too, were casual and far from pretentious: Isadora danced barefoot and in a simple loose tunic, with minimal props and lighting effects so that they did not distract the audience from her movements.

Duncan believed that dance should be a "divine expression" of the human spirit, and this problem with the intrinsic motivation of dance was common to all early contemporary choreographers. In their productions, they presented characters and situations that broke the romantic, fabulous atmosphere of modern ballet and flaunted the primitive instincts, conflicts and passions of the inner essence of man. To this end, they sought to develop a style of movement that was more natural and more expressive than ballet.

Martha Graham, for example, believed that the center of all movements should be the back, and especially the pelvis. Therefore, many of her most characteristic movements were "spiral" and performed with a strongly arched back. Doris Humphrey saw all human movement as a transition between falling (when the body is out of balance) and recovery (when it returns to a balanced, balanced state), and many of her movements included imitation of falls.

Instead of defying gravity, as in ballet, contemporary dancers emphasized their own weight. Even all their jumps and "flying movements" looked as if the dancers had just momentarily escaped the Earth's downward pull, and many of their movements were performed close to the floor or even lying down. For example, Martha Graham developed a wide repertoire of "falls," and Mary Wigman's style was characterized by bent knees, often thrown back heads, and arms that were rarely high in the air.

The ballet tried to hide the "earthiness" or "defy gravity", so it tried to hide any hint of tension in the dances. Contemporary dance, by contrast, especially in Graham's work, emphasized these qualities. Angled movements, clenched fists and bent legs, as well as seemingly violent movements of the back and a clearly defined line of tension that runs through all movements - this was Martha Graham's choreography, which expressed not only the dancer's struggle against physical limitations, but also the power of her passion and frustration. The movements were always expressive gestures and never wore a decorative uniform. Often the body and limbs of the dancers looked broken, and their faces distorted by emotions, but choreographers like Nijinsky were not afraid to appear ugly (as, indeed, most of their contemporaries did).

Contemporary dance, by contrast, especially in Graham's work, emphasized these qualities. Angled movements, clenched fists and bent legs, as well as seemingly violent movements of the back and a clearly defined line of tension that runs through all movements - this was Martha Graham's choreography, which expressed not only the dancer's struggle against physical limitations, but also the power of her passion and frustration. The movements were always expressive gestures and never wore a decorative uniform. Often the body and limbs of the dancers looked broken, and their faces distorted by emotions, but choreographers like Nijinsky were not afraid to appear ugly (as, indeed, most of their contemporaries did).

The structure of early modern dance pieces contributed in part to the fragmented narrative and symbolic characteristics of modernist art and literature. Graham often used flashbacks and "time-shifting" techniques, as in Clytemnestra (1958) or different dancers who performed different facets of the same character, as in Seraphic Dialogue (1955). Groups of dancers formed a cohesive whole and often represented social or psychological moments. At that point, there was very little hierarchical separation between the lead dancers and the corps de ballet.

Groups of dancers formed a cohesive whole and often represented social or psychological moments. At that point, there was very little hierarchical separation between the lead dancers and the corps de ballet.

Merce Cunningham

The Expressionist school dominated contemporary dance for several decades. From the 1940s, however, there began to be a growing backlash against Expressionism, led by Merce Cunningham. Cunningham wanted to create a dance that was "an expression of itself" - about the types of movement that the human body is capable of, as well as about rhythm, phrasing and structure. First of all, he wanted to create a dance that would not be subject to any requirements or descriptions that were accepted before. This does not mean that Cunningham wanted to make dance "subordinate" to music or design. On the contrary, many of his works combined all these aspects: music and design formed an essential part of the overall effect, these elements were often performed independently of the actual dance. Cunningham believed that a movement should define its own space and establish its own rhythms, rather than be influenced by music. In addition, he felt that it would be more interesting and challenging for the viewer to observe these independently functioning elements, and then choose for themselves how to connect them to each other.

Cunningham believed that a movement should define its own space and establish its own rhythms, rather than be influenced by music. In addition, he felt that it would be more interesting and challenging for the viewer to observe these independently functioning elements, and then choose for themselves how to connect them to each other.

Believing all movement to be potential material for dance, Cunningham developed a style that spanned an extremely wide spectrum, from natural, everyday activities (such as sitting and walking) to virtuoso dance moves. Elements of his style even had a close affinity to ballet: the jumps tended to be light and airy, while the footwork was intricate and intricate. He placed more emphasis on upright body position and less emphasis on balance and "opposing" gravity. Like Martha Graham, many of Cunningham's movements came from the back, but his style tended toward less dramatic twists and turns, with Cunningham's dancers' arms often in graceful curves.

Cunningham's performances often consisted of complex, coordinated movements of the head, legs, body and limbs in a series of rapidly changing positions. The positioning of the performers on the stage was just as complex: at any given moment, there were several dancers on the stage, who seemed to form random formations, but they all performed the movements at the same time. In the absence of the main dominant action on the stage, the spectator was free to focus on any part of the dance according to his taste.

The positioning of the performers on the stage was just as complex: at any given moment, there were several dancers on the stage, who seemed to form random formations, but they all performed the movements at the same time. In the absence of the main dominant action on the stage, the spectator was free to focus on any part of the dance according to his taste.

Whereas Martha Graham's work tended to be narrated around events, Cunningham's work usually emphasized one or more choreographic ideas, the development of which was randomly determined. This does not mean that Cunningham's work lacked expressive power. One of his productions (Winterbranch, 1964) began as an exploration based on movement through space and falling, but it had a profound effect on the audience, who interpreted the production in different ways: some considered it a dance piece about war and concentration camps, while others saw in it a description of sea storms. Cunningham believed that the expressive qualities in the dance should not be determined by the storyline, but this line should itself become apparent from the movements themselves. “Emotions will appear with the movements of the dances,” he argued. Because that's what life is about.

“Emotions will appear with the movements of the dances,” he argued. Because that's what life is about.

Postmodern dance

During the 1960s and 1970s, a new generation of American choreographers, commonly referred to as postmodern choreographers, developed some of Merce Cunningham's ideas even further. They also believed that ordinary movements could be used in dances, but they completely rejected the strong element of virtuosity in Cunningham's technique and the complexity of his phrasing and dance structure, insisting that such a style would interfere with the process of seeing and feeling movements. Consequently, postmodernists have replaced ordinary dance steps with simple movements such as walking. Their work focused on the basic principles of dance: space and time, as well as the weight and energy of the dancer's body.

Postmodernists completely discarded the concept of spectacle, considering it another distraction from the real perception of movements. Common work or street clothes were often used as costumes. They also made little use of scenery or lighting, and many performances took place in lofts, galleries, or even outdoors.

Common work or street clothes were often used as costumes. They also made little use of scenery or lighting, and many performances took place in lofts, galleries, or even outdoors.

Descriptive and expressive elements have been dropped. The dance structures were usually very simple and involved either the repetition and "accumulation" of simple movements, or the practice of simple dance sequences. For example, in Tom Johnson's production of Ending Breath (1976), the dancer simply ran around the stage reciting the lyrics until he ran out of breath.

Most of the avant-garde modern dance groups were quite small and essentially took a position "on the sidelines" of the dance world, attracting only a small and specialized audience. Although modern dance is now in the "mainstream" and currently attracts huge audiences in Europe and North America, for many decades this art form was underdeveloped and often performances were performed for just a few spectators. Interestingly, modern dance groups today, as before, are relatively small.