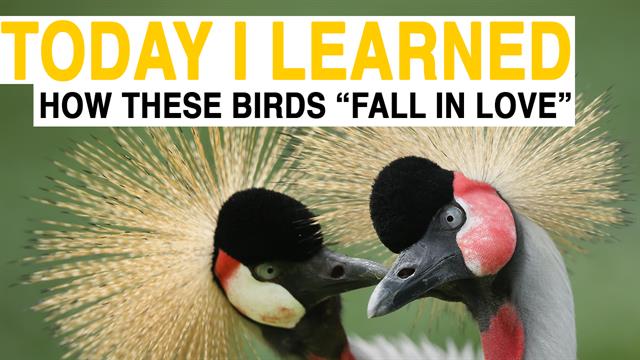

How to dance birds

10 Outrageous Ways Birds Dance to Impress Their Mates

Some people are simply born to dance—and the same goes for birds. Many species, once grown, find themselves overcome with a primal urge to bust a move.

Some male birds gather in leks, not unlike nightclubs, to dance in a group and invite curiosity from nearby females. Others perform feats of strength and endurance to prove their value. And in some species, males and females dance together to form a pair bond while putting on a show.

Without further ado, here we present a sampling of the best bird mating dances out there. Watch, learn, and maybe even take a few notes.

Laysan Albatross

At around three years old, young Laysan Albatross return to their birthplace to start learning the ways of courtship. Deep in their bones they know the dance moves needed to woo a mate, but they haven’t yet developed their talent. At first, young birds gather in small groups to practice. As the years go on, those groups grow smaller, until finally the confident birds are ready for their big finale: a partnered dance. A new Laysan Albatross pair works hard to perfect their dance, combining stock moves like the “sky snap,” “rapid bill clapper,” and “bob strut” into a sequence unique to that couple. Only then will the birds lay their first egg, typically at age eight or nine.

Red-capped Manakin

In Central American forests, male Red-capped Manakins keep their wings tucked and heads down to draw a female’s gaze to their brilliant yellow thighs—and fancy footwork. The birds slide and glide along a branch as if living in a frictionless world, hopping and pivoting to change direction, all to catch the eye of a female with exceptionally high standards. Their pièce de résistance? A moonwalk that rivals Michael Jackson's.

Their pièce de résistance? A moonwalk that rivals Michael Jackson's.

Magnificent Riflebird

The Magnificent Riflebird, one of about 40 bird-of-paradise species, isn’t afraid to let loose on the . . . tree branch. He stretches his elegant black wings and then dramatically whips his head from side to side to display his blue iridescent throat. But don’t think that he wants to dance with the object of his affection; no, if a female approaches, he will continue dancing on his own, flicking his wings more strenuously while hopping toward her. Then, the choice is hers: to copulate with him and then raise the brood by herself, or wait for a better show.

The Magnificent Riflebird isn't the only bird-of-paradise with exceptional dance skills. Take a gander at the Vogelkop Superb Bird-of-Paradise sliding around with a bright blue frown.

Costa’s Hummingbird

A male Costa’s Hummingbird is better named Squidface. He begins flirting by swooping and diving over his perched crush, and twists his body acrobatically in the air. That takes a lot of energy and strength—but it’s not enough to impress her. Then, he flexes muscles in his face, and his gleaming magenta feathers flare out. When the sun’s rays hit them at just the right angle (from the female’s perspective), he hardly looks like a bird, and more like a Cthulhu with wings.

Blue-footed Booby

At first, you might mistake the male Blue-footed Booby for a demure romantic. He begins his dance by shyly drawing attention to his feet. He might also give the object of his affection a bow, or tickle her with his beak. But then, once both are warmed up, he brings out the big guns: He rotates his shoulders so his stretched long, dark wings frame his face, all while stepping delicately to remind her about those sexy blue feet. If he’s lucky, she’ll slow step right along.

He might also give the object of his affection a bow, or tickle her with his beak. But then, once both are warmed up, he brings out the big guns: He rotates his shoulders so his stretched long, dark wings frame his face, all while stepping delicately to remind her about those sexy blue feet. If he’s lucky, she’ll slow step right along.

Western and Clark's Grebes

If you’re looking for elegance in the bird world, you can’t do much better than Western or Clark's Grebes. In both closely related species, courtship begins with one bird mirroring the other’s movements, twisting and bowing their long necks behind them. And then, when the moment is right, they take the leap: Like ballerinas wearing pointe shoes, they rise fully out of the water, running side by side on the water’s surface with their wings stretched behind them. Their dance is both a feat of strength and a transcendent spectacle. (You can see examples of both species in the video shown here.)

Their dance is both a feat of strength and a transcendent spectacle. (You can see examples of both species in the video shown here.)

If you prefer tango to ballet (or even if you don't like either), definitely also check out the bonkers mating display of the Hooded Grebe.

Sandhill Crane

The dance of the Sandhill Crane is iconic, and also extremely awkward. The male begins by doing all he can to attract attention—stretching his wings behind him, bending his neck backward toward his body, and even throwing grass or clumps of dirt into the air. Once he’s caught a female’s eye, the pair begin their gangly dance. They exchange bows and then leap into the air and flap their wings, sometimes completing a 180-degree mid-air turn. It might not seem very romantic, but then again, we aren’t cranes. Who are we to judge?

Who are we to judge?

Jackson’s Widowbird

Jackson’s Widowbirds, which live in Kenya and Tanzania, keep it simple when proving their worth with a good old-fashioned jumping competition. The males, sleek in shiny black feathers and brandishing a long, luxurious tail, gather in a field. Then, they jump as high as they can and for as long as they can. The winner of this endurance test can expect attention from mottled brown females watching nearby.

Sharp-tailed Grouse

Sharp-tailed Grouse are the tap dancers of the bird world. At dawn, males gather in a group and begin their show: They rise up—with wings outstretched, heads bowed down, and tails up—expand their purple air sacs, and rapidly stamp their feet. They almost look like wind-up toys as they move forward, backward, and in circles, accompanied by the mechanical patter of their feet pounding the earth.

They almost look like wind-up toys as they move forward, backward, and in circles, accompanied by the mechanical patter of their feet pounding the earth.

Love these moves? Learn more about the behaviors of the Sharp-tailed Grouse by

Greater Sage-Grouse

What is there to say about the dance of the male Greater Sage-Grouse? It must be seen to be believed. The enormous chicken-relatives sport a regal look, with a spiked tail fan, frilly cravat of bright white feathers, and abundant chest displayed proudly. Then, just when sunrise hits the lek, they perform what’s known as a “strutting display:” The birds heave their chests forward to expand a pair of bright yellow esophageal air sacs (sometimes crudely called “chesticles”), generating a bizarre sound known as a “plop” that resounds for miles. That way, females know just where to find them.

That way, females know just where to find them.

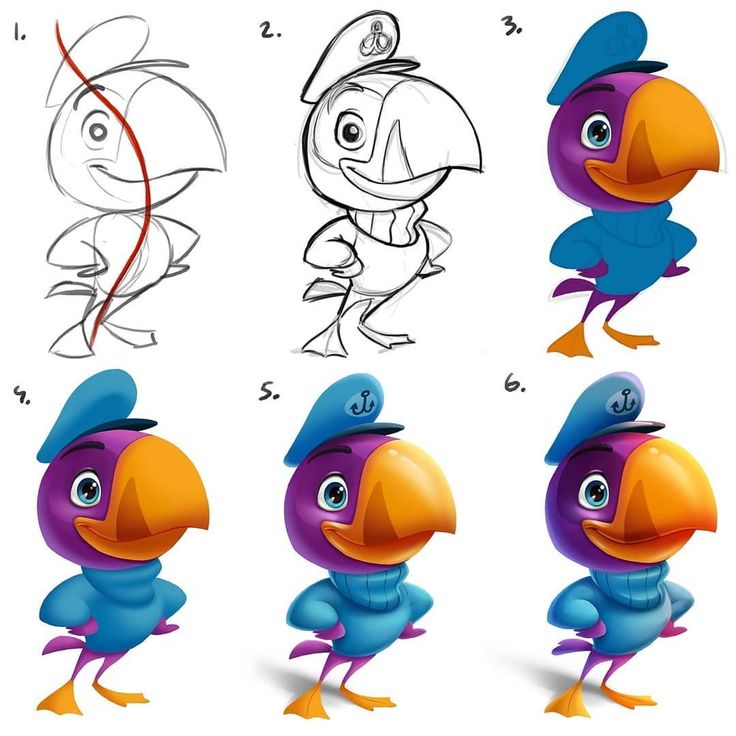

How to Train Your Bird to Dance

Dancing is one of the funniest and easiest tricks to teach your bird. This behavior comes naturally to many of our feathered friends, with highly intelligent birds such as cockatiels and parrots among the easiest to train.

Not only will teaching your bird to dance be entertaining, but it will also offer your pet some extra exercise and mental stimulation, both of which can improve its overall health.

-

01 of 06

Choose an Appropriate Training Space

Juana Mari Moya / Getty Images

Before you begin to teach your bird any sort of trick, it's important to take the time to choose the best area of your home to use as a training space.

Birds can respond differently to training depending on their level of comfort with their surroundings, so it pays to select an area that your bird will view as non-threatening and safe.

Birds can respond differently to training depending on their level of comfort with their surroundings, so it pays to select an area that your bird will view as non-threatening and safe. Quiet, non-cluttered rooms generally make the best choices, preferably away from the majority of household foot traffic. Eliminating as many distractions as possible will help keep your bird on track during your training sessions.

-

02 of 06

Select Upbeat Music

PeopleImages / Getty Images

By nature, birds are geared to respond to sound, so it's no wonder that so many seem to enjoy hearing various types of music. When teaching your bird how to dance, try to choose a fun, upbeat tune to train your bird with. Rhythmic songs with medium to fast tempos tend to encourage most parrots to get moving quickly.

Don't be discouraged if your bird doesn't seem to appreciate your musical choices, just keep trying different types of music until you find something that your bird seems to respond to.

-

03 of 06

Set an Example for Your Bird

Hero Images / Getty Images

It sounds like a silly idea, but sometimes birds learn best when they are given an example. If your bird doesn't seem to be getting the hang of dancing on his or her own, it may be necessary for you to step in and give your pet a demonstration. Turn the music up and dance around to show your bird how fun it can be. Many times this will excite parrots to the point that they will start dancing along with you before they even realize what they're doing.

-

04 of 06

Use Visual Props

Sean Murphy / Getty Images

If your bird still doesn't dance despite your best demonstrations and other efforts, then you may consider showing your pet some videos of other birds "cutting a rug." Make a playlist of your favorite dancing bird videos to share with your pet. Birds generally love watching other birds, and usually, they will emulate what they see.

This can be one of the quickest ways of encouraging your bird to dance or perform an array of other tricks and behaviors.

This can be one of the quickest ways of encouraging your bird to dance or perform an array of other tricks and behaviors. -

05 of 06

Reward Progress

Elena Kovalevich / Getty Images

As with all training exercises, it's important to reward your pet for any progress it makes toward learning the behavior that you're trying to teach. Even if your bird isn't a full-blown dancing machine after the first few training sessions, rewarding progress in increments is key to helping your pet understand the behavior that you want them to learn.

Keep some tasty bird treats on hand while training to make sure that your bird stays engaged and interested in what you are doing. Using treats to keep training sessions fun will help your bird learn more quickly and easily over time.

-

06 of 06

Problems and Proofing Behavior

Bill Killillay / Getty Images

Since dancing is a behavior that comes naturally to most pet birds, it's a little different than teaching a behavior like singing or talking.

If you're having difficulty getting your bird to dance on cue, keep trying different kinds of music. Try leaving the music on when you're not around (at a reasonable volume, of course) so the bird doesn't feel any performance anxiety. Most birds will figure out how to get their groove on with some patient encouragement from you.

If you're having difficulty getting your bird to dance on cue, keep trying different kinds of music. Try leaving the music on when you're not around (at a reasonable volume, of course) so the bird doesn't feel any performance anxiety. Most birds will figure out how to get their groove on with some patient encouragement from you.

How they get married. From morning to evening

How to get married

Peculiar expressive means - special movements and postures of animals: threatening, fighting, attracting or transmitting a certain kind of information, which are usually called dances - apparently, they are quite often used in nature, but have not yet been studied by everyone. Folk legends and hunters tell, for example, about some mysterious dances of wild elephants, which pachyderms gather in the depths of the jungle and about which zoologists, in fact, know nothing.

Rat dances were sometimes observed.

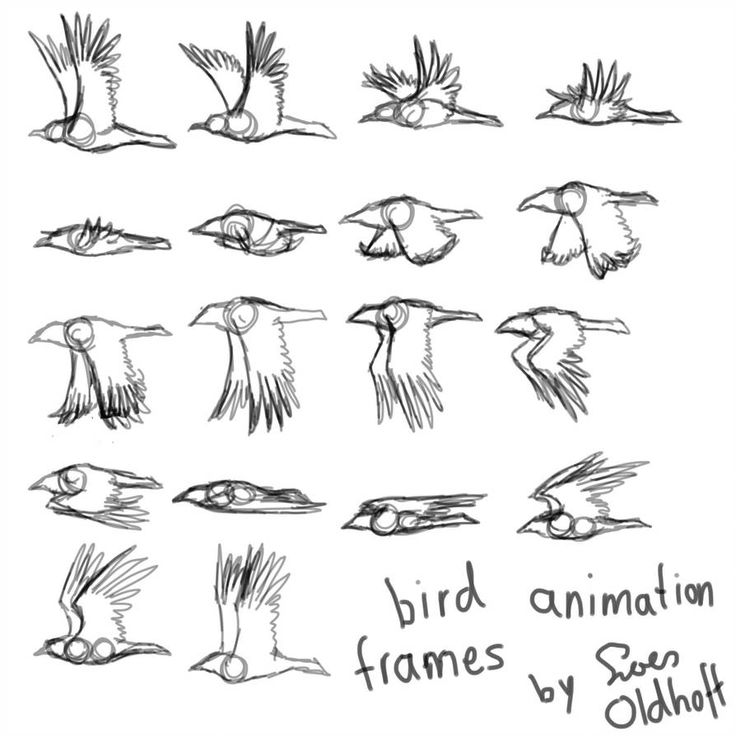

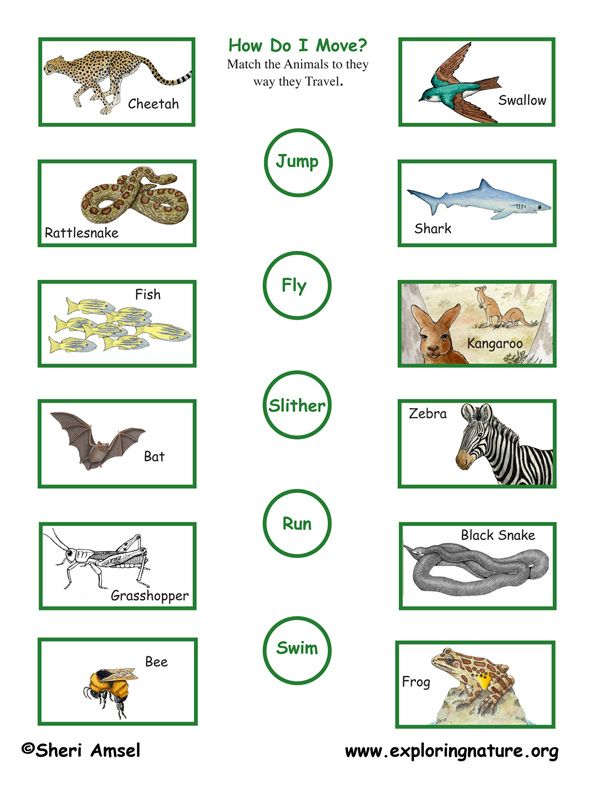

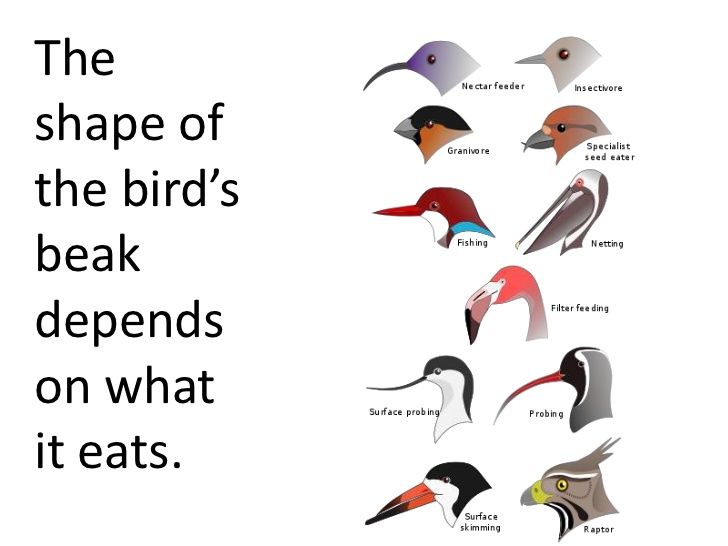

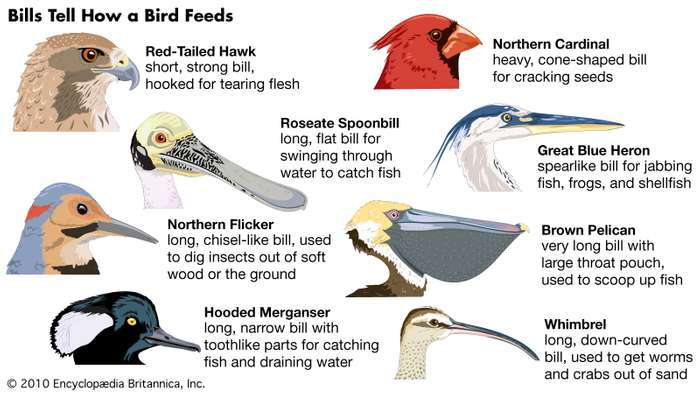

But the most popular are the "dancing dawns" in the feathered kingdom. Dances, or current, love games of birds, are well known to everyone. Usually the males dance. They live alone or gather annually at the time of reproduction in certain places: in forest clearings and glades, in swamps and in the steppes near selected bushes, on trees. They also swim in the air, for example, snipes, woodcocks, forest pipits and white partridges.

Dances, or current, love games of birds, are well known to everyone. Usually the males dance. They live alone or gather annually at the time of reproduction in certain places: in forest clearings and glades, in swamps and in the steppes near selected bushes, on trees. They also swim in the air, for example, snipes, woodcocks, forest pipits and white partridges.

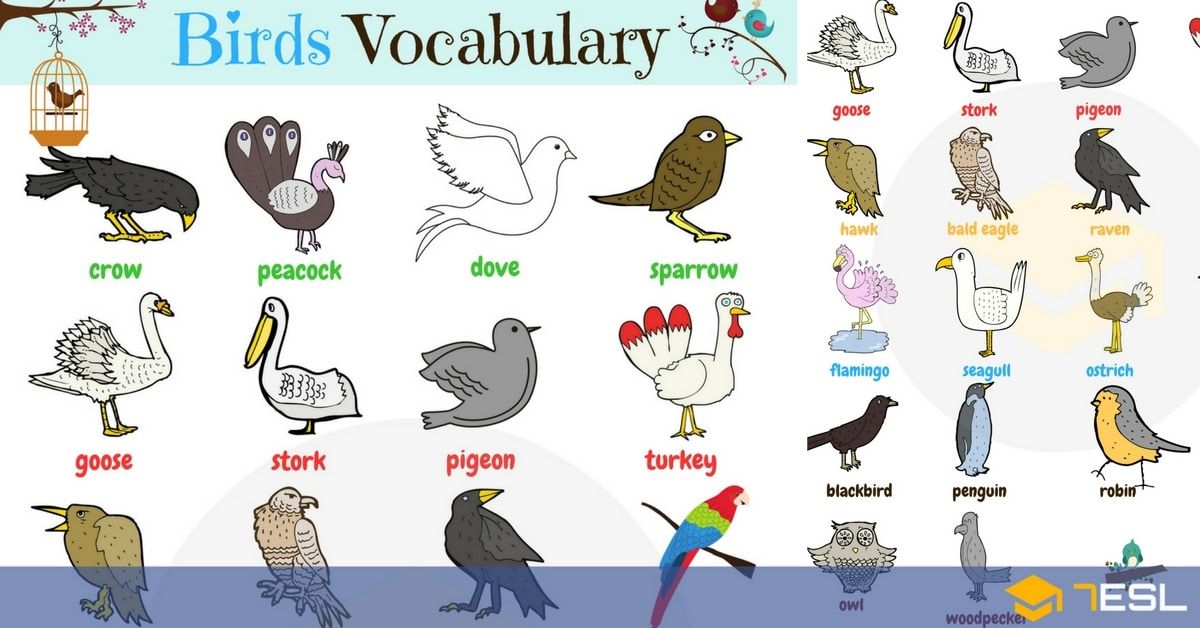

Think about black grouse, turukhtans, little bustards, and finally about pigeons.

Current birds try to show the brightest parts of their plumage with peculiar, often very unusual movements and usually accompany the dance with special calls, muttering or clicking. Sometimes the males fight and chase each other, but this, as I said, is more of a ritual duel than a serious fight. The females, for which these games are intended to attract, are usually present in the form of inconspicuous, often indifferent, but very welcome spectators here. Sometimes they express their attitude towards cavaliers with special, outwardly insignificant movements, for example, by pecking real or imaginary grains and berries from the ground. And these encouraging pecks, like applause from the public, warm up the excitement of the dancers.

And these encouraging pecks, like applause from the public, warm up the excitement of the dancers.

Sometimes females take a more active part in displaying. The girlfriend of the North American red-shouldered troupial, sitting, for example, on a branch next to him, repeats all the movements of the current male.

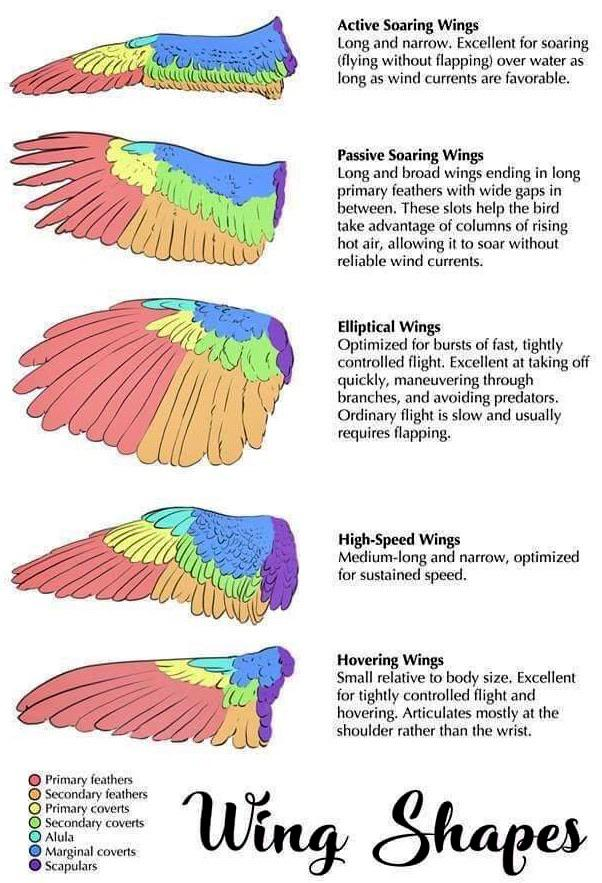

The dances of the albatrosses crown a whole series of preliminary ceremonies: the birds carry various building materials to the nest with cries. This is a game, not real construction. They “applaud” themselves, tapping their beaks, and then they stretch out on their paws and, spreading giant wings, lifting their heads up into the sky, shift from foot to foot in a slow dance near the nest.

Sparrows also dance around the females, fanning their tails and wings. And wagtails, and tits, and snow bunting. These inhabitants of the tundra, who are visiting us in late autumn, are talking in a very strange way: with their backs to the lady! Buntings have the most beautiful plumage on the back. Here the males strive to flaunt it, turning their backs to the female. At the same time, they spread their wings and stretch upward.

Here the males strive to flaunt it, turning their backs to the female. At the same time, they spread their wings and stretch upward.

The female approaches her chosen one, and he jumps from her and around her, but with his back to her. What unkindness!

Even owls dance! In spring, at dusk and all night until dawn, the male eagle owl walks in small steps around the female. All birds, when tokaya, usually ruffle their feathers, and the eagle owl, on the contrary, presses them tightly to the body. That is why his figure looks unusually thin and high-legged. Walking around, he screams, swelling his throat, hoots fearfully, in the manner of a goblin.

A flowing golden pheasant, also striding importantly around the female, looks at her over the lush collar like a coquette from behind a fan, and even winks with its amber eye for greater effect.

The Himalayan monal flows first sideways to the female, then quickly spins in place, scattering multicolored flashes of its “metallic” plumage around.

Pheasant argus is courting his girlfriend in a very picturesque way: first, in a ceremonial march, he approaches her in a spiral. Then, suddenly, like a painted umbrella, huge wings spread out, on which they shine, shimmer, like stars in the sky, bright eye spots. For them, the bird was nicknamed the argus in honor of the hundred-eyed hero of ancient Greek myths.

These colorful scenes play out in the mornings in the virgin forests of Sumatra and Indochina, in fern-covered glades, which, when the old argus dies, pass into the sole possession of one of his sons.

Perhaps the most unusual current postures and movements are those of the magnificent relatives of our crows - birds of paradise that live in the forests of New Guinea and nearby islands.

A large bird of paradise, sitting on a branch of a tall tree, opens the show with a loud and hoarse cry. Then, lowering his head, he crouches lower and lower, sways left and right. It shakes more and more energetically, spreads its wings, trembles finely. Iridescent, fiery cascades of thin hair-like feathers flow, decorating her sides. Suddenly, the bird bends down, completely lowers its wings and raises its orange feather-hairs on its sides, like a banner. Freezes in this position for one or two minutes, then slowly folds the disheveled "banner".

Iridescent, fiery cascades of thin hair-like feathers flow, decorating her sides. Suddenly, the bird bends down, completely lowers its wings and raises its orange feather-hairs on its sides, like a banner. Freezes in this position for one or two minutes, then slowly folds the disheveled "banner".

Other birds of paradise declare their love even more extravagantly: after shaking on a bough, they suddenly hang upside down, scattering iridescent waves of fabulously beautiful plumage above them, and hang stoically in this unnatural pose, making their beloved swoon with delight.

Her feelings are easy to understand, because the display of birds of paradise, especially when about a dozen of these tightrope walkers gather in one place, is indeed a very beautiful sight.

Of all the bird dances that take place in our forests in spring and sometimes in autumn, cranes have the most scenic program. Apparently, all cranes dance, but the best of them dancers are belladonnas. They live in Ukraine, in the Caspian steppes and in southern Siberia.

As soon as they arrive in our area, the cranes choose a flat and dry place. At morning dawns and in the evenings, all the cranes nesting in the area gather on it: both males and females. Stand in a circle sometimes in two, sometimes in three rows. In the center of the circle is a free dance floor. One or the other birds run out on it and dance, hilariously crouching and bouncing. They bow, spread and fold their wings, stretch out their long necks, inflate their goiters and accompany themselves with trumpet calls.

Having danced enough, they return to the circle, and new dancers run out into the arena.

It is not known, however, whether female cranes dance. Or is it the privilege of males, and females only stand in a circle, in a crowd of spectators?

Manchurian crane dances are better studied.

This snow-white crane with a black neck, black wingtips and a red cap is very beautiful in itself, and when it dances, it is said that the audience simply takes their breath away. Recently, his dances were described in detail, providing a description with excellent photographs, by the American naturalist Stuart Keith.

Recently, his dances were described in detail, providing a description with excellent photographs, by the American naturalist Stuart Keith.

The Manchurian crane nests in the swampy plains of Manchuria and Hokkaido, and here in the Ussuri region and, possibly, in some places along the Amur. It is rare everywhere (in Japan, for example, only about two hundred tanchos are now preserved - this is how the Japanese call these birds).

Like other cranes, tancho is always ready to dance, but in January, February and March he dances especially a lot and well.

Cranes dance both in pairs and in the whole flock.

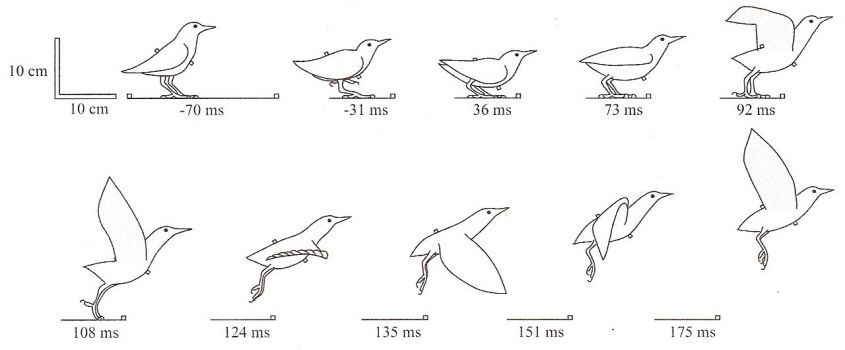

This is a pair dance. Both birds (at the tancho, the male and the female cannot be distinguished by appearance) suddenly interrupt the hunt for frogs for a while and turn their beaks towards each other. One of them begins to bow: stretches her neck to the partner, slightly arching it downwards. In this pose, the crane's head and neck gently sway up and down, up and down. Then the bird flaps its wings and dances around. With each new turn, the pace increases. Here are both birds, facing each other, jumping up, flapping their wings. In the jump, the left leg - it is held slightly higher than the right - vigorously kicks the air. At the apogee of the jump - it is about two meters high - the birds scatter their wings, and it seems that for a moment they are floating in the air. Sometimes, jumping especially high, the cranes make a “dance flight”: side by side, they slowly and gracefully glide down and land about forty meters from the place where they took off. Usually after that they stop dancing, dust themselves off and again busily look for frogs.

Then the bird flaps its wings and dances around. With each new turn, the pace increases. Here are both birds, facing each other, jumping up, flapping their wings. In the jump, the left leg - it is held slightly higher than the right - vigorously kicks the air. At the apogee of the jump - it is about two meters high - the birds scatter their wings, and it seems that for a moment they are floating in the air. Sometimes, jumping especially high, the cranes make a “dance flight”: side by side, they slowly and gracefully glide down and land about forty meters from the place where they took off. Usually after that they stop dancing, dust themselves off and again busily look for frogs.

There are three more interesting steps in the Manchurian crane dances. When dancing, they often grab various small objects from the ground with their beaks - twigs, dry blades of grass, grains or even scraps of paper - and throw them into the air. The second "pa": the dancer jumps with his back to the partner, spreading his wings as wide as possible. Then their black trim is clearly visible - a contrast to the white plumage of the crane.

Then their black trim is clearly visible - a contrast to the white plumage of the crane.

Sometimes the birds freeze one in front of the other, stretching their necks up and pressing their beaks to their chest, as if showing red caps on the crown. The wings are slightly raised. Then they raise their heads, so that the beaks now look at the sky, and scream piercingly.

Usually choreographic duets are performed in complete silence. But when the whole flock is dancing, the cranes cheer themselves up with cries.

If a bird invites its partner to a ball by nodding, other tanchos grazing peacefully in the swamp often surround them and also begin to jump. Sometimes a whole dozen cranes dance at once. Some perform the entire dance, others make only a few lazy jumps, still others stand and watch, fourth ones, those who are far from the dancers, collect grain in the field or clean themselves without any attention to them. But those who are closer cannot help but dance. “Apparently,” writes one zoologist, “dance has the same contagious effect on cranes as laughter has on us.”

“Apparently,” writes one zoologist, “dance has the same contagious effect on cranes as laughter has on us.”

Young cranes do not have to learn the art of dancing from old people, they are born "trained", with full knowledge of all figures and pirouettes. The little crane, who lived in captivity, writes Kate, already knew how to make crane batmans five days old - he jumped high, kicking with his foot. He also bowed and threw various objects to the sky. He had never seen the other cranes dancing.

Current birds in their strange body movements and in pauses between jumps, freezing for a moment, take different poses, often hilarious, but always unusual and well noticeable.

They pursue this goal - to attract the attention of the female.

Sometimes the female also shows with a special movement that the male's proposal has been accepted and he can count on reciprocity.

The female Avocet seals the “marriage contract” with the male with a special symbolic gesture: she nervously cleans her perfectly cleaned plumage with her beak. This is her kind of "signature" under the marriage proposal, which the male presents to her in the form of current courtship.

This is her kind of "signature" under the marriage proposal, which the male presents to her in the form of current courtship.

In some birds, males and females are colored exactly the same. And it's hard to tell them apart by voice. Then it happens that males certify their gender by various offerings, and females by accepting a gift.

Having caught a fish, a male tern holds it in its beak and walks along the shallows. A tern who takes a fish from him, thereby, as it were, signs a marriage contract. Sometimes the male does not immediately give up his offering: he does not let go of the fish, and the female pulls it towards her. That's how they play.

Adélie penguins give the prospective ladies all sorts of pebbles, which are piled at their feet. If the gift is accepted, then the donor was not mistaken: in front of him is the one he was looking for. And heaps of pebbles now serve as an application for a nest.

The other pair will not take their marked place.

Gulls and Galapagos cormorants, when they go to change partners on the nest, bring him a bunch of grass or algae in his beak. A strange instinct, the origin of which is not very easy to unravel.

But it is even more difficult to understand the meaning of the mysterious manipulations with various kinds of objects brought from afar by other birds - bowerbirds, or gazebos, about which I have already spoken.

Year of the crane. Issue #1 They Arrived Home

On Bird Day, WWF Russia announces the premiere of the Year of the Crane-2020 video series.

Videos about the life of cranes in the Amur basin, starting from today, will be released almost in real time about once a week. This is taken care of by videographer Igor Ishchenko, who is now "in the fields" and is filming cranes on the migration and nesting.

All series of the competition

Hurrah! Finally back! Everyone flew, everyone is alive and well.

Familiar places, dear to the heart. Here are my favorite reeds, and there is a backwater where my betrothed and I met. Nearby is my Fedyushka, already dancing for joy. True, repairs are to be done, but nothing, we are used to it: every year we start the season with it.

They say that every sandpiper praises his swamp, but, excuse me, we don’t have such a swamp, and my husband and I are not teasers. By the way, you can't see them. Still too early.

But the lapwings are already right there. Just look at her defiant hairstyle: what kind of fashion has gone strange now? Yes, even strides importantly, also to me, the beauty queen.

Yeah, and the gopher Senya is in place. She told him not to lean on sweets, otherwise the figure would blur. He obeyed - he chews grass. Slim. Maybe he just got emaciated over the winter?

The heron Tsatsa, who lives in a tussock opposite, did not convince her husband to fill in the path. He slides out, barely moving his legs. Late for the meeting, how to give a drink. The rest were already crowded together, the agenda was read out, and they began to vote.

The rest were already crowded together, the agenda was read out, and they began to vote.

Anton the stork walks in splendid isolation. How is he going to get kids? He has a line for babies, by the way, since last year. He promised the people heirs, and he walks with a red beak. He probably chewed fermented viburnum, bast does not knit.

Oh, I'm glad to see everyone, although misunderstandings sometimes happen with neighbors. But in general, we have a good area, friendly.

Amur basin

Creep. Man is still both a friend and an enemy to us. Look! In the last century, a serious decline in the population of Far Eastern storks has been recorded. They are constantly being watched! When only 100 non-empty nests were found in the Amur Region, environmentalists stood up to protect them - an invaluable heritage of the Russian land.

How they dance! This couple is not the first time here. Today they are more cheerful than ever, because there is something to satisfy their hunger.